Submitted:

19 December 2025

Posted:

22 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Content and Learning Objectives

Educational Scope and Learning Objectives

Instructional Design

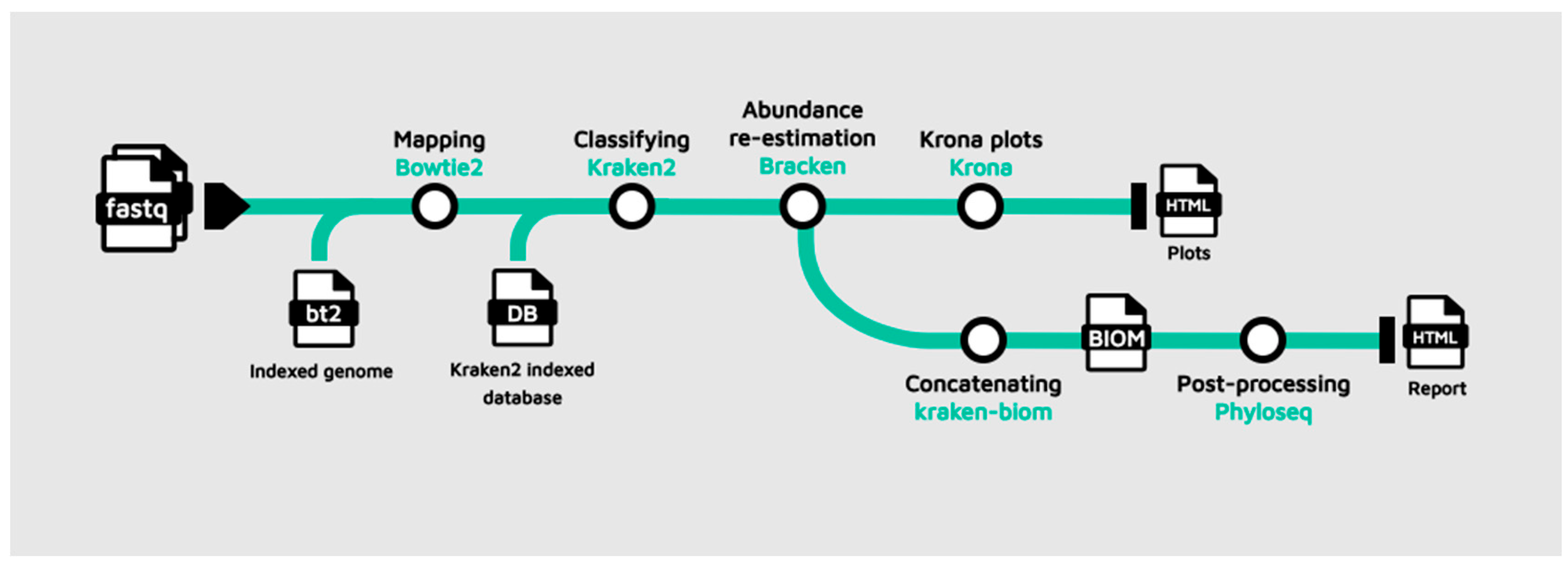

Part 1: Pipeline

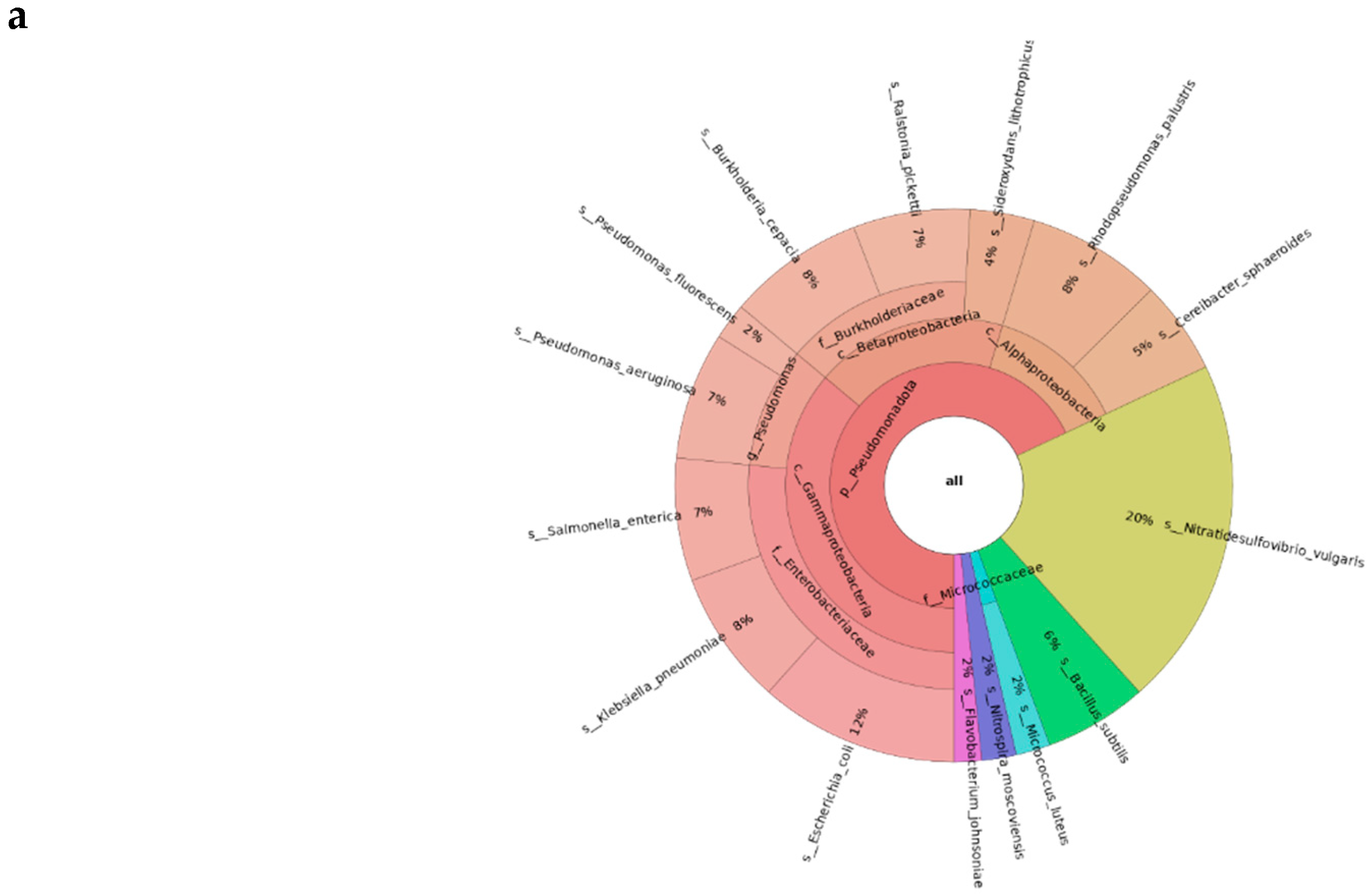

Part 2: Single Sample

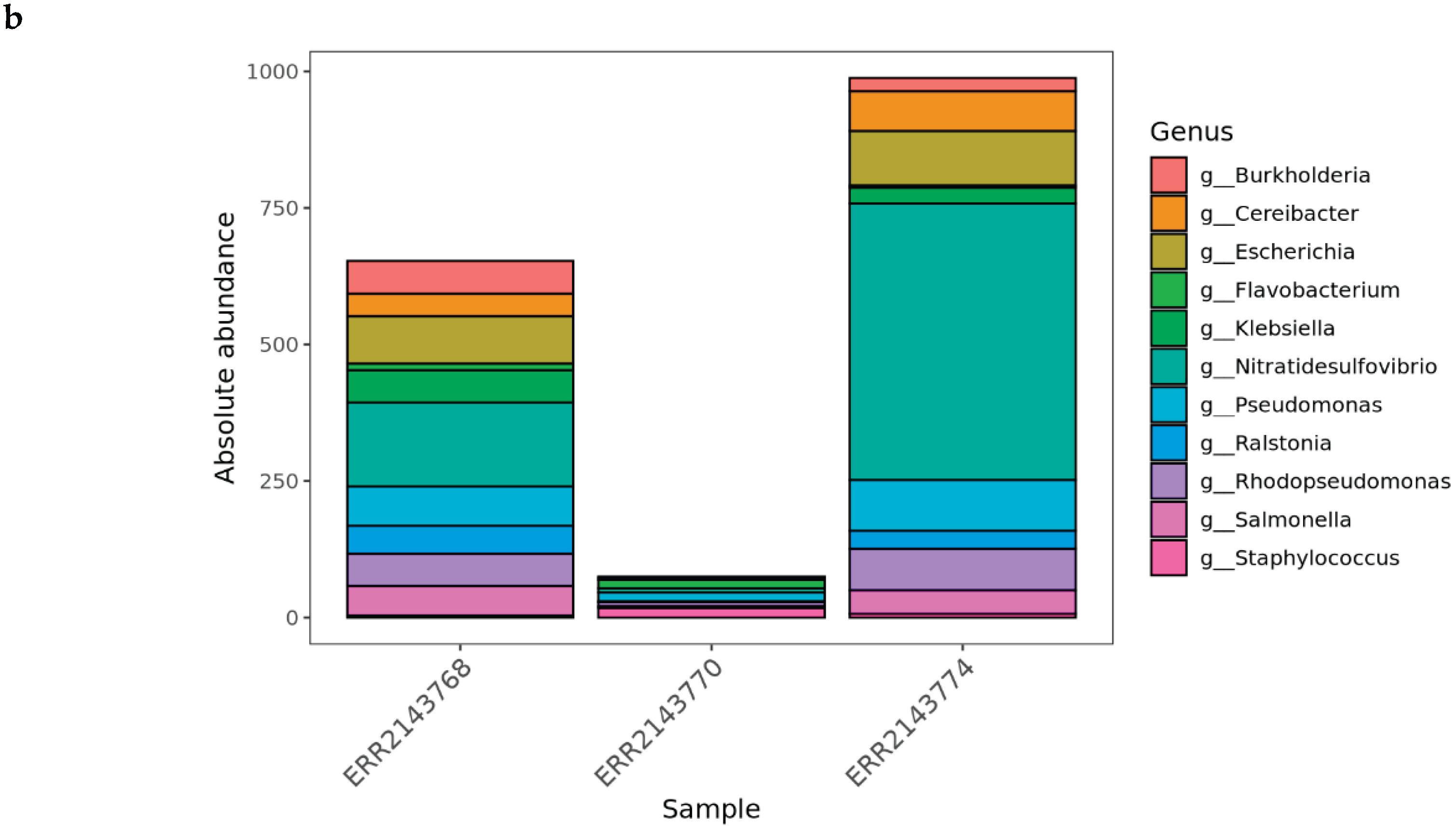

Part 3: Multi-Sample

Conclusion

Availability of data and materials

Acknowledgments

References

- Kim, N.; et al. Genome-resolved metagenomics: a game changer for microbiome medicine. Exp. Mol. Med. 2024, 56, 1501–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, M. 1,500 scientists lift the lid on reproducibility. Nature 2016, 533, 452–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; et al. A review of computational tools for generating metagenome-assembled genomes from metagenomic sequencing data. Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal 2021, vol. 19, 6301–6314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tommaso, P. D.; et al. Nextflow enables reproducible computational workflows. Nat. Biotechnol. 2017, 35, 316–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mölder, F.; et al. Sustainable data analysis with Snakemake. Research 2021, 10, 33. [Google Scholar]

- Roach, M. J.; et al. Ten simple rules and a template for creating workflows-as-applications. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2022, 18, e1010705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wratten, L.; Wilm, A.; Göke, J. Reproducible, scalable, and shareable analysis pipelines with bioinformatics workflow managers. Nat. Methods 2021, 18, 1161–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, A. E.; et al. Design considerations for workflow management systems use in production genomics research and the clinic. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navgire, G. S.; et al. Analysis and Interpretation of metagenomics data: an approach. Biol. Proced. Online 2022, 24, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwin, N. R.; Fitzpatrick, A. H.; Brennan, F.; Abram, F.; O’Sullivan, O. An in-depth evaluation of metagenomic classifiers for soil microbiomes. Environ. Microbiome 2024, 19, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wajid, B.; et al. Music of metagenomics—a review of its applications, analysis pipeline, and associated tools. Funct. Integr. Genomics 2022, 22, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-X.; et al. A practical guide to amplicon and metagenomic analysis of microbiome data. Protein Cell 2021, 12, 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, D. E.; Lu, J.; Langmead, B. Improved metagenomic analysis with Kraken 2. Genome Biol. 2019, 20, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, D. E.; Salzberg, S. L. Kraken: ultrafast metagenomic sequence classification using exact alignments. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, R46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, J.; Breitwieser, F. P.; Thielen, P.; Salzberg, S. L. Bracken: Estimating species abundance in metagenomics data. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2017, e104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Míguez, A.; et al. Extending and improving metagenomic taxonomic profiling with uncharacterized species using MetaPhlAn 4. Nat. Biotechnol. 2023, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menzel, P.; Ng, K. L.; Krogh, A. Fast and sensitive taxonomic classification for metagenomics with Kaiju. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ounit, R.; Wanamaker, S.; Close, T. J.; Lonardi, S. CLARK: fast and accurate classification of metagenomic and genomic sequences using discriminative k-mers. BMC Genomics 2015, 16, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Song, L.; Breitwieser, F. P.; Salzberg, S. L. Centrifuge: rapid and sensitive classification of metagenomic sequences. Genome Res. 2016, 26, 1721–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milanese, A.; et al. Microbial abundance, activity and population genomic profiling with mOTUs2. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timilsina, M.; Chundru, D.; Pradhan, A. K.; Blaustein, R. A.; Ghanem, M. Benchmarking Metagenomic Pipelines for the Detection of Foodborne Pathogens in Simulated Microbial Communities. J. Food Prot. 2025, 88, 100583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pusadkar, V.; Azad, R. K. Benchmarking Metagenomic Classifiers on Simulated Ancient and Modern Metagenomic Data. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stamouli, S.; et al. nf-core/taxprofiler: highly parallelised and flexible pipeline for metagenomic taxonomic classification and profiling. Preprint 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borry, M. Source code for: kraken-nf - Simple Kraken2 Nextflow pipeline. 2024. Available online: https://github.com/maxibor/kraken-nf.

- EPI2ME. Source code for: wf-metagenomics - Metagenomic classification of long-read sequencing data. 2025. Available online: https://github.com/epi2me-labs/wf-metagenomics.

- Angelov, A. Source code for: nxf-kraken2 - A simple nextflow pipeline for running Kraken2 and bracken in a docker container. 2025. Available online: https://github.com/angelovangel/nxf-kraken2.

- Terrón-Camero, L. C.; Gordillo-González, F.; Salas-Espejo, E.; Andrés-León, E. Comparison of Metagenomics and Metatranscriptomics Tools: A Guide to Making the Right Choice. Genes 2022, 13, 2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petit, R. A.; Read, T. D. Bactopia: a Flexible Pipeline for Complete Analysis of Bacterial Genomes. mSystems 2020, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langer, B. E.; et al. Empowering bioinformatics communities with Nextflow and nf-core. Genome Biol. 2025, 26, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zirión-Martínez, C.; et al. A Data Carpentry- Style Metagenomics Workshop. J. Open Source Educ. 2024, 7, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruchten, A. E. A Curricular Bioinformatics Approach to Teaching Undergraduates to Analyze Metagenomic Datasets Using R. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Telatin, A. Source code for: nextflow-example - A simple DSL2 workflow: tutorial. 2022. Available online: https://github.com/telatin/nextflow-example.

- Lu, J.; et al. Metagenome analysis using the Kraken software suite. Nat. Protoc. 2022, 17, 2815–2839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S. L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 357–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ondov, B. D.; Bergman, N. H.; Phillippy, A. M. Interactive metagenomic visualization in a Web browser. BMC Bioinformatics 2011, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadri, S.; Sboner, A.; Sigaras, A.; Roy, S. Containers in Bioinformatics: Applications, Practical Considerations, and Best Practices in Molecular Pathology. J. Mol. Diagn 2022, 24, 442–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barker, M.; et al. Introducing the FAIR Principles for research software. Sci. Data 2022, 9, 622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, W. S. A Quick Guide to Organizing Computational Biology Projects. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2009, 5, e1000424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okie, J. G.; et al. Genomic adaptations in information processing underpin trophic strategy in a whole-ecosystem nutrient enrichment experiment. eLife 2020, 9, e49816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, D.; et al. The Biological Observation Matrix (BIOM) format or: how I learned to stop worrying and love the ome-ome. GigaScience 2012, 1, 2047-217X-1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMurdie, P. J.; Holmes, S. phyloseq: An R Package for Reproducible Interactive Analysis and Graphics of Microbiome Census Data. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e61217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.