1. Introduction

Driven by the growing demand for functional and diverse daily products [

1,

2,

3], smart textiles represent the integration of textile engineering with electronics [

4,

5] information technology [

6], biology [

7], medicine [

8], and renewable energy [

9]. These advanced materials can detect and respond to changes in the human body and environment while maintaining the inherent aesthetic and technical features of traditional textiles [

10]. Among the main categories of smart textiles, including shape-memory textiles and waterproof-breathable fabrics, reversible thermochromic materials have attracted increasing attention [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17].

Reversible thermochromic materials, also termed temperature-sensitive materials, undergo color changes within a specific temperature range due to variations in their visible light absorption spectrum [

18,

19,

20]. This property provides fabrics with intuitive temperature indication and dynamic decorative effects, meeting the multifunctional demands of smart textiles [

21,

22,

23,

24].

A significant challenge is ensuring thermal sensitivity, reversibility, and stability in textile applications [

25,

26,

27]. Recent studies have emphasized embedding thermochromic microcapsules containing leuco dyes into polymer coatings, fibers, or fabric inks [

28,

29]. Concurrently, research on inorganic thermochromic pigments, such as vanadium dioxide (VO

2), has shown excellent thermal and chemical stability [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35]. Advances in fields like anti-counterfeiting [

36], decoration [

37], and thermal management [

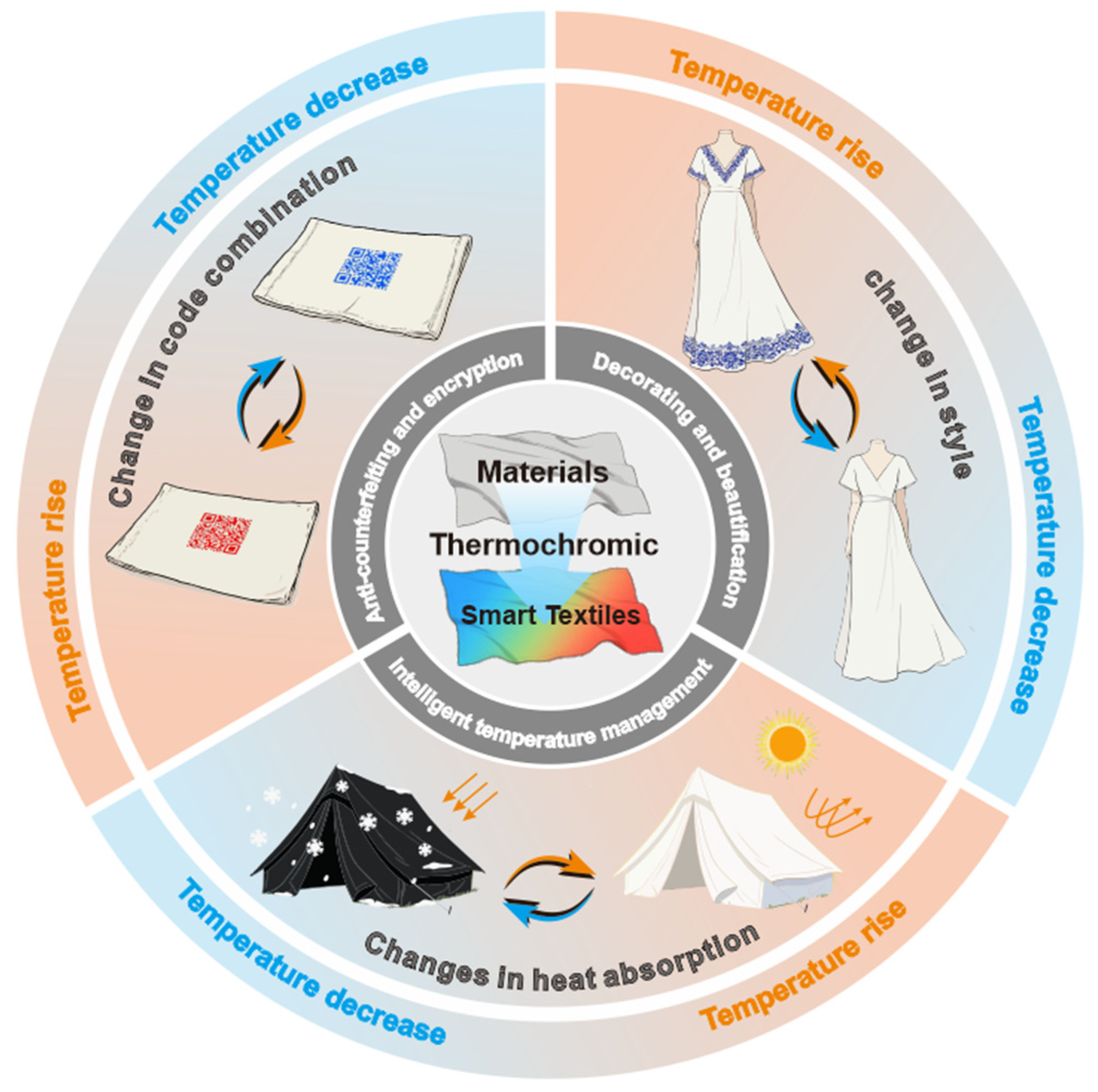

38] (

Figure 1) have further increased interest in reversible thermochromic smart textiles. Although research and development in this area have expanded in recent years, systematic reviews remain limited. Notably, the incorporation of reversible thermochromic materials into traditional textile techniques such as kesi is still at an early stage.

This review systematically examines reversible thermochromic materials and their integration into smart textiles, focusing on current developments and challenges. It discusses applications in anti-counterfeiting, decoration, and thermal management, highlighting their value and potential. Furthermore, the review aims to promote the deep integration of traditional craftsmanship and modern technology. By addressing a research gap and providing foundational knowledge for combining thermochromic materials with traditional methods, this work offers new perspectives for designing the next generation of smart textiles.

2. Reversible Thermochromic Materials

Reversible thermochromic materials are substances that undergo physical transformations or structural rearrangements in response to changes in ambient temperature. These transformations alter their spectral properties, resulting in observable color changes [

23].

2.1. Organic Reversible Thermochromic Materials

Compared to inorganic and liquid crystal (LC) reversible thermochromic materials, organic reversible thermochromic materials offer advantages such as vivid colors, distinct color changes, and high temperature sensitivity. The color transition range can be precisely adjusted by modifying the dye structure, enabling a wide variety of colors including red, green, yellow, blue, and black [

24,

25,

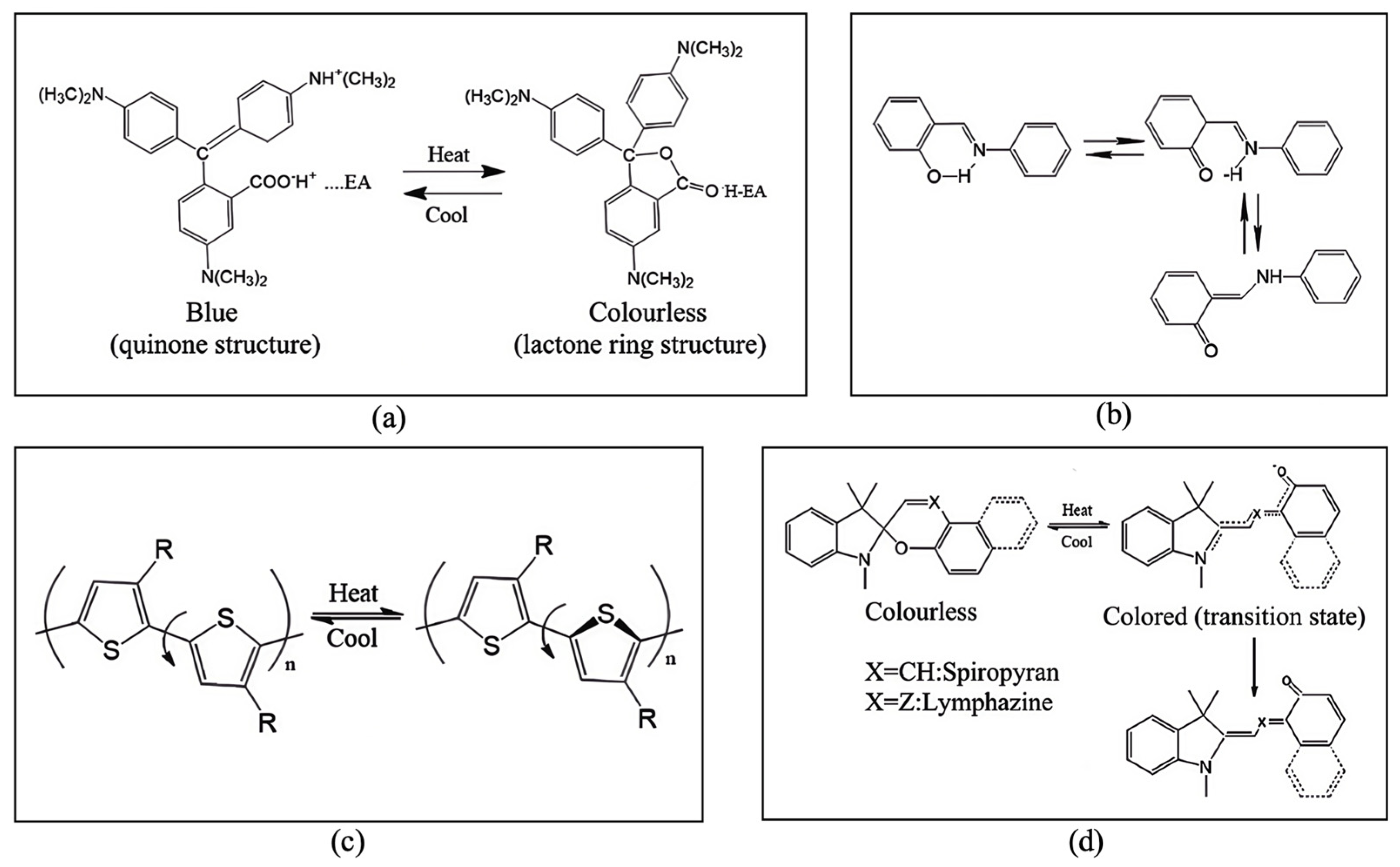

26]. The color change mechanisms in these materials involve intermolecular electron transfer, molecular conformational changes, crystal phase transitions, and molecular ring-opening, as illustrated in

Figure 2 [

21].

Thermochromism driven by intermolecular electron transfer is predominantly found in organic thermochromic systems. This process typically involves a leuco dye, a developer, and a solvent [

44,

45]. The leuco dye, acting as an electron donor, determines the initial color and undergoes structural changes after electron transfer, resulting in a color variation. Common leuco dyes include triarylmethanes, fluorans, bisanthrones, Schiff bases, spiro compounds, and other organic complexes [

21]. The developer serves as an electron acceptor and consists of both inorganic and organic types. Common organic developers mainly include phenolic hydroxyl compounds and their derivatives, carboxylic acids and their derivatives, sulfonic acids, acid phosphates and their metal salts, triazines, halogenated alcohols and their derivatives. The solvent (temperature modifier) is an organic compound that regulates the temperature sensitivity. Its melting point largely determines the color-changing temperature of reversible thermochromic materials. Common solvents include higher fatty alcohols, thiols, ketones, phosphates, sulfonates, carboxylates, and sulfites.

The preparation of organic reversible thermochromic composites involves three components: leuco dye, developer, and solvent, which require materials with good compatibility. The choice and combination of these components influence factors such as the tunability of the color-changing temperature, flexibility in color matching, visibility of the color shift, and cost. Among the common selections, crystal violet lactone and bisphenol A (BPA) serve as the leuco dye and developer, respectively, due to their wide color range and stability [

41,

46,

47]. Crystal violet lactone (

Figure 3a), one of the earliest triarylmethane thermochromic dyes, changes color primarily through the reversible opening and closing of its internal lactone ring structure [

48]. Mao Dongyu et al. combined crystal violet lactone, BPA, and 1-tetradecanol to form a thermochromic composite, determining an optimal component ratio of 1:40:70 through experiments. The resulting material exhibited a color-changing time of 42 seconds as well as excellent thermal and acid-base resistance [

49]. Beyond this common system, researchers [

36] have developed a reversible thermochromic material based on sulfones, using bromocresol purple (BCP) as the developer. The color-changing temperature of this material can be adjusted within 13-46 °C. In a heating-cooling cycle test, it maintained stable reversibility with no significant degradation of color parameters after 50 cycles. Experimental data show that targeted adjustment of the thermochromic points is achievable. This requires precise control over the thermochromic transition temperature, which is by varying the ratio of long-chain alcohols to stearic acid. The alcohols used in this study are dodecanol, tetradecanol, hexadecanol, and octadecanol.

Lötzsch and colleagues [

49,

50,

51,

52,

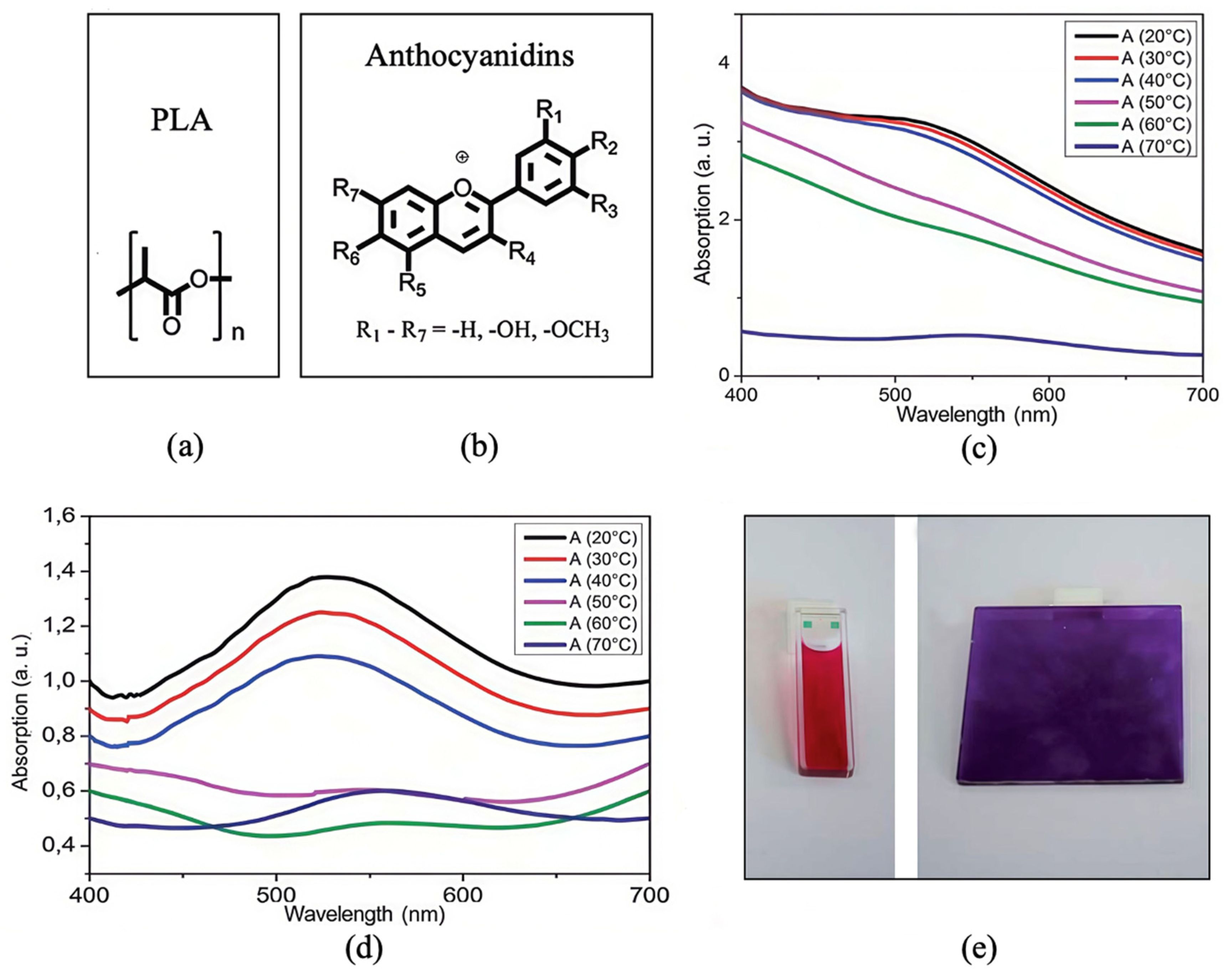

53] have focused on natural materials as substitutes for conventional thermochromic systems and identified anthocyanin as a naturally occurring organic compound. By systematically analyzing the interaction between poly(lactic acid) (PLA) and cyanidin chloride, a reversible and non-toxic thermochromic composite was successfully prepared, as shown in

Figure 3 (a-b). This anthocyanin-based thermochromic PLA composite comprises PLA, cyanidin chloride, dodecyl gallate, and hexadecanoic acid. Upon heating from 20 °C to 70 °C, the first transition is the glass transition of the polymer matrix occurring between 40 and 50 °C, followed by the melting of hexadecanoic acid-rich domains at 60–70 °C (

Figure 3 (c)). Both transitions cause significant changes in light scattering.

Figure 3 (d) reveals that the thermochromic transition coincides the glass transition temperature. In the glassy state, the absorption maximum is near 530 nm, shifting to about 560 nm above the glass transition. As demonstrated in

Figure 3 (e), the color changes from red to purple.

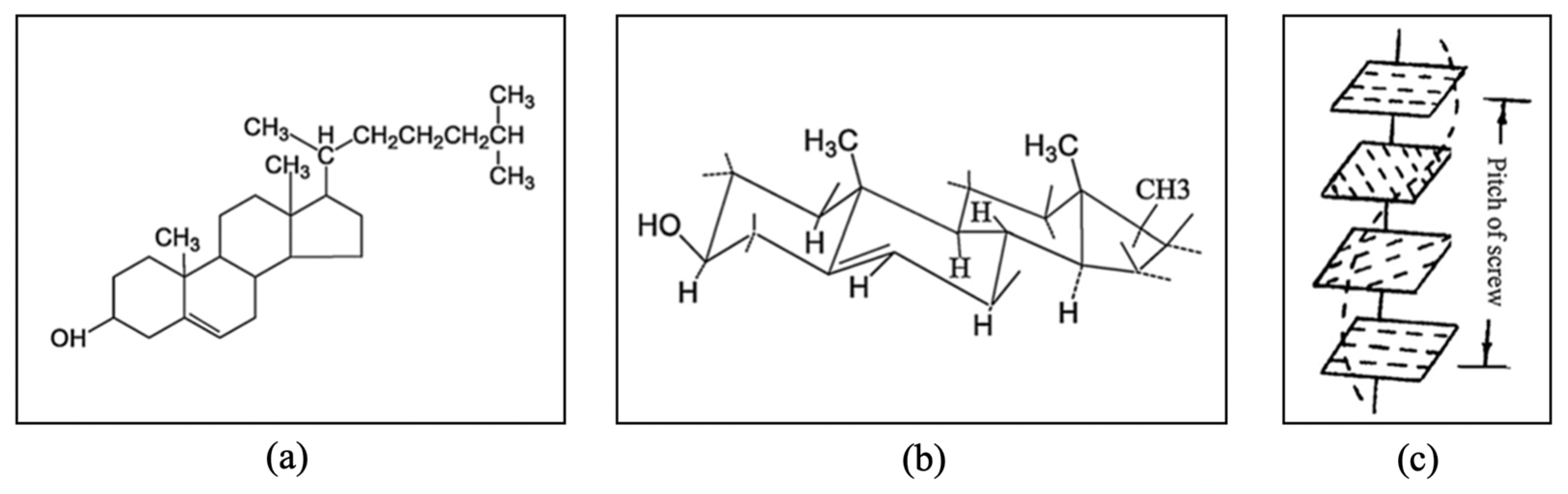

2.2. Reversible Thermochromic Materials Based on LCs

LCs exhibit excellent stability and high sensitivity to temperature changes. However, their application is limited due to chemical sensitivity and relatively high costs. Based on molecular arrangement, LCs are classified as smectic, nematic, and cholesteric types, with cholesteric LCs being the most used [

21,

53,

54,

55]. Cholesteric LCs (

Figure 4), also known as chiral nematic LCs, possess a periodic helical superstructure, classifying them as a type of “soft” PC. Reversible thermochromic LCs have been developed for textile printing and dyeing [

56,

57]. Advantages of LC-based reversible thermochromic materials include low color-changing temperature, adjustable temperature range, and high color sensitivity. However, drawbacks include high cost and weak color-changing intensity [

58]. Furthermore, since LCs lack affinity for fibers, they must be encapsulated into microcapsules and combined with polymeric binders in textile applications [

59,

60,

61]. This process reduces the brightness and tactile quality of LC-based thermochromic products.

Cholesteric liquid crystalline elastomers (CLCEs) are typically synthesized via copolymerization of chiral and achiral monomers with functional end groups [

62,

63,

64]. To achieve different thermochromic responses upon heating, Schlafmann et al. [

65] demonstrated that tunable and switchable thermochromic effects can be obtained by adjusting cross-linking density and LC composition of CLCEs. Their study focused on CLCEs composed of two achiral liquid crystalline diacrylates (C6M and C6BAPE) and one chiral liquid crystalline diacrylate (C6-r-M or C6-r-BAPE), shown in

Figure 5 (a-b). Modulated differential scanning calorimetry (MDSC) data in

Figure 5 (c) indicate that C6M and C6-r-M have the highest phase transition temperatures, attributed to their 1, 4-bis(4-[n-acryloyloxybutoxy]benzoyloxy)-2-methylbenzene mesogenic cores. The presence of two methyl groups on the aliphatic chain of C6-r-M creates chiral centers that influence mesogen packing and arrangement, lowering the nematic-isotropic transition temperature (T

NI) and the crystallization temperature (T

C) during cooling. C6BAPE contains a biaryl core structure, which weakens intermesogenic interactions, resulting in a reduced T

NI. C6-r-BAPE exists as an isotropic liquid at room temperature, exhibiting a T

NI below room temperature (−31.7 °C) during cooling. Due to the weakened intermesogenic interactions caused by these monomers, the T

NI decreases, and the low birefringence in some CLCE formulations enables tuning of thermochromic reflection. By varying CLCE compositions, different thermochromic effects can be achieved, as shown in

Figure 5(d). Experiments confirmed that this thermochromic material exhibits excellent thermal stability below 200 °C, with rapid and synchronized color changes, making it suitable for real-time temperature monitoring. Regarding cyclic durability, the color-changing material-maintained integrity after 200 heating and cooling cycles without performance loss.

2.3. Inorganic Reversible Thermochromic Materials

The primary factors contributing to thermochromism in inorganic compounds include lattice structure changes, alterations in ligand geometry, and variations in crystalline water content [

66]. These materials comprise metal ion compounds, metal complexes, hydrated inorganic salts, chromates, and their mixtures. With the expansion of temperature-indicating materials, an increasing number of reversible thermochromic substances, such as vanadates, chromates, and tungstates, have been selected for practical applications. Metal ions can be chosen from Group I and II elements, as well as transition metals from Groups IVB, VB, and VIB.

Due to the presence of toxic components inherently found in inorganic reversible thermochromic materials, their applications are more common in electrical equipment than in textiles. These materials have several key applications: indicating temperature thresholds of heated components; detecting overheating; providing early warnings for heat generation in rotating shafts and related friction parts; and enabling precise surface temperature distribution measurements on heating elements [

23,

66,

67,

68,

69,

70]. However, VO

2 (

Figure 6) represents an exception, demonstrating significant potential for thermochromic smart textiles because of its rapid and reversible phase transition properties [

71,

74,

75]. VO

2 undergoes a notable transformation from a monoclinic semiconductor phase to a rutile metallic phase upon reaching a specific temperature. Typically, this phase transition occurs around 68 °C, though the exact transition temperature depends on the preparation method [

72,

73].

For example, doping VO

2 thin films with tungsten lowers the phase transition temperature to approximately 25–30 °C, near room temperature [

75]. To improve VO

2 material performance further, Kabir’s group [

76,

77,

78] developed a room-temperature solution process to fabricate VO

2-based thermochromic thin films, as illustrated in

Figure 7(a). This approach uses a smart ink composed of crystalline VO

2 nanoparticles, with polymers acting as both capping agents and surface modifiers to enhance chemical stability and deposition uniformity. During printing, the VO

2/polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) solution exhibited higher viscosity and easier patterning compared to VO

2/polyvinyl pyrrolidone (PVP) solution. Hence, VO

2/PVA was selected as the printing ink on glass, with results shown in

Figure 7(b).

Figure 7(c) demonstrates that the VO

2/PVA composite films achieved improvements in visible light transmittance, infrared modulation (ΔT2000nm), and solar modulation efficiency, reaching 86%, 42%, and 17.61%, respectively. These results indicate that the screen-printed VO

2/PVA films possess excellent visible transmittance and infrared modulation performance. The modified films not only significantly enhance thermochromic properties but also offer potential for more efficient and widespread use in textile applications.

2.4. Reversible Thermochromic PC Materials

Photonic crystals (PCs) exhibit photonic band gaps, also referred to as “photonic forbidden bands,” situated between the energy bands of different materials. When the photonic band gap lies within the visible light frequency range, visible light of specific wavelengths cannot penetrate the PC. Instead, these light forms coherent diffraction on the crystal surface, resulting in structural color (

Figure 8) [

79,

80]. Temperature variations induce slight structural changes in PCs, such as expansion or contraction of lattice spacing. These modifications alter the band gap width and, consequently, the color of reflected light. Applying this mechanism enables the fabrication of reversible thermochromic structural color textiles. These textiles exhibit high chroma, excellent lightfastness, and are environmentally friendly.

To enhance the functionality of thermochromic PC materials, Xue et al.[

81,

82,

83,

84,

85,

86] developed a simple and rapid in-situ polymerization approach. This method enabled the fabrication of dual-responsive PCs with ultra-precise micro-nano hierarchical structures using natural PC templates. The process involved activating reaction sites through deacetylation, followed by in-situ polymerization of poly(N-isopropylacrylamide-co-acrylic acid) (P(NIPAAM-co-AAc)) on Morpho butterfly wing surfaces. The resulting P(NIPAAM-co-AAc) PCs demonstrated reversible responses to both pH and temperature (

Figure 9).

This section has reviewed several types of reversible thermochromic materials suitable for smart textiles, with related data summarized in

Table 1. It also highlights recent research advances in reversible thermochromic materials, aiming to inform their integration with traditional textile techniques such as silk tapestry production. Specifically, organic reversible thermochromic materials show relatively low stability and are vulnerable to degradation from light and heat. However, they offer the widest color change range, flexible combination potential, fast color switching speed, and the shortest cycle life. These properties make them well-suited for smart textiles requiring rapid response and rich color variations. LC-based materials need microcapsule or film encapsulation and provide moderate stability, the narrowest color shift range, intermediate switching speed, and relatively high reuse cycles. Inorganic reversible thermochromic materials offer the highest stability but exhibit a narrow and fixed color shift range, the slowest switching speed, and relatively high cycle durability. Thus, they are appropriate for smart textiles that prioritize long-term stability and durability over color diversity. PC-based reversible thermochromic materials span a wide size range, demonstrate relatively high stability, a broad color shift range, the fastest switching speed, and substantial recyclability, making them suitable for rapid-response, color-rich smart textiles.

For clearer comparison of key performance parameters between organic, inorganic, and LC reversible thermochromic materials.

Table 2 provides a systematic summary of these materials across core dimensions, including color range, stability, and cost. Additionally, the table analyzes their advantages and limitations within practical application contexts, offering guidance for material selection.

3. Preparation of Reversible Thermochromic Smart Textile

Transforming reversible thermochromic materials into smart textiles necessitates ensuring their secure adhesion to the fabric. To achieve this, a series of intricate printing, dyeing, and finishing techniques are required. A widely adopted method involves the microencapsulation of reversible thermochromic materials, followed by their application as core components of printing inks onto the fabric surface via printing and dyeing processes [

74,

87,

88,

89,

90,

91]. Furthermore, various advanced approaches, including fiber preparation techniques, printing and dyeing technologies, and material microencapsulation, have been developed for the fabrication of reversible thermochromic smart textiles [

93]. The specific implementation methods and research advancements pertaining to these techniques are elaborated upon in the subsequent sections.

3.1. Fiber preparation technology

Reversible thermochromic textiles are prepared by incorporating reversible thermochromic materials into polymers prior to feeding them into the spinning pump, producing fibers with thermochromic properties. This process primary relies on molecular structure changes. Advantages include good color fastness, stability, comfort, a relatively straightforward production process, and excellent oxidation and heat resistance. However, it requires complex equipment and incurs higher production costs.

Preparation methods for reversible thermochromic fibers include melt spinning, solution spinning, electrospinning, and microfluidic spinning. Melt spinning, a molding technique using polymer melt as raw material, employs a melt spinning machine to produce fibers (

Figure 10a). Polymers are heated until molten, extruded through spinneret holes, and cooled in air to form fibers. This method includes blend spinning and sheath-core composite spinning. Blend spinning involves melting and mixing high-molecular-weight polymers, such as polyester, with thermochromic polymers for spinning. Alternatively, thermochromic compounds can be compounded with resin carriers to create thermochromic masterbatches, then mixed with polymers for melt spinning. Compared to original fibers, those produced by this method have altered physical properties, such as increased diameter and rougher surfaces. However, it also presents challenges, including uneven distribution of thermochromic properties within the fibers and increased viscosity during spinning, which complicates processing. Sheath-core composite spinning prepares temperature-sensitive reversible thermochromic materials compounded with high-molecular-weight polymers as the core layer, while another polymer forms the sheath layer. After melt spinning, temperature-sensitive thermochromic composite fibers are obtained. This technique offers advantages such as smaller fiber diameters, smooth surfaces, uniform distribution of thermochromic materials, and lower melt or solution viscosity, improving processing during spinning.

Solution spinning methods are primarily divided into wet spinning and dry spinning. Wet spinning (

Figure 10b), the earlier developed technique, involves extruding a spinning solution into a coagulation bath containing a specific coagulant, which precipitates the solution into solid fibers. Various coagulants have been explored, including organic solvents, acidic or alkaline solutions, inorganic salt solutions, and polymer solutions. However, methanol is toxic, and the rapid coagulation of silk in methanol or ethanol, coupled with swift structural transformation of the silk protein, can result in insufficient molecular chain orientation, making the fibers brittle [

94]. Therefore, selecting a coagulant should depend on the material, properties, and intended application of the fibers. For instance, Chen et al.

95 used polymer solutions as coagulants. They applied dual-core coaxial wet spinning to fabricate composite fibers. These fibers consisted of a multifunctional conductive hydrogel and a thermochromic elastomer, featuring a core-shell segmented structures. These composite fibers have various applications, including human motion monitoring, body or ambient temperature detection, and color decoration. The diameter of thermochromic fibers produced by wet spinning can be controlled by adjusting the spinneret hole size and the viscosity of the spinning solution. Typically, these fibers exhibit a relatively smooth surface. Dry spinning resembles wet spinning; however, fiber solidification occurs through solvent evaporation or air cooling rather than coagulation in a liquid bath (

Figure 10c). Compared to wet spinning, dry spinning offers continuous production and higher spinning speeds, but the equipment is more complex and costly. Furthermore, wet spinning provides superior control over polymer stability and thermochromic properties, making it more suitable for polymers prone to color changes upon heating. Consequently, dry spinning is less commonly used for preparing thermochromic fibers.

Electrospinning primarily utilizes an electric field to generate fibers (

Figure 10d). Among its variants, coaxial electrospinning, a specialized form, has been applied for fabricating thermochromic fibers. This method employs a coaxial setup, typically comprising inner and outer electrodes and a nozzle for injecting solution or molten polymer into the electric field. Under a high-voltage electric field, the polymer droplets elongate and solidify into fibers. Coaxial electrospinning enables the production of ultrafine, functional fibers for thermochromic applications; however, challenges remain, including poor fiber uniformity and complex surface morphology. Although this technique offers greater efficiency and flexibility than traditional spinning methods, it demands precise adjustment of the two distinct flow rates and solution properties, complicating process control.

Microfluidic spinning combines the laminar flow characteristics of microfluidics with the rapid prototyping advantages of conventional spinning methods to produce fibers (

Figure 10e). In fabricating thermochromic fibers, this approach allows accurate control over fiber diameter, surface morphology, uniformity, viscosity, and draw ratio. It yields fibers with high uniformity and fine structure, potentially enhancing their performance and application prospects. Microfluidic technology involves manipulating microscale fluids within designed microchannels. Its precise and systematic control of individual fluids and interfaces has made it a powerful technique for synthesizing functional materials.

94 For instance, Zhang’s group [

94,

95] produced editable, multicolored polylactic acid fibers with thermochromic properties via microfluidic spinning, demonstrating potential uses in anti-counterfeiting, military camouflage, and wearable displays.

3.2. Printing and Dyeing Technology

Thermochromic inks are primarily applied to textiles via printing and dyeing techniques to produce smart textiles that change color in response to temperature variations. Screen printing is commonly employed, using a specially designed mesh to evenly deposit the thermochromic ink on fabric surfaces, which is suitable for creating intricate patterns. Inkjet printing is also frequently utilized due to its high flexibility in fabricating thermochromic smart textiles [

96]. Nonetheless, these methods have limitations: many printing and dyeing processes involving stimulus-responsive materials are sensitive to environmental factors such as temperature, humidity, and light. This sensitivity can cause variations in color or performance under adverse conditions, affecting product quality and durability.

Zhang et al. [

74] fabricated smart textiles exhibiting both reversible thermochromic and fluorescent properties via screen printing. The resulting hybrid polymer composites demonstrated rapid color change, high contrast, and reversibility. These composites were prepared by encapsulating indanthrone dyes dissolved in fatty alcohols. The materials maintained excellent thermoreactivity and responsiveness after at least 100 heating and cooling cycles. Nie’s research team [

97] successfully developed a photothermal chromic self-disinfecting textile through in-situ growth of PCN-224 metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), electrospraying Ti

3C

2 MXene colloids, and screen printing thermochromic dyes, as shown in

Figure 11(a-b). This textile shifts color from dark green to dark red when temperature exceeds 45 °C and rapidly exhibits a thermochromic response within one second under 780 nm laser irradiation. However, the use of materials such as PCN-224 MOFs and electrosprayed Ti

3C

2 MXene colloids increases production costs due to their high expense. Moreover, temperature changes under intense or prolonged light exposure may reduce wearer comfort. Wang et al. [

96,

97,

98,

99] developed a thermally activated fluorescent ink composed of multicolor carbon dots (CDs) for computer inkjet printing, as illustrated in

Figure 11(c-d). The printed patterns exhibit reversible color changes when stimulated by heat or light. However, the complex formation mechanism of CDs hinders precise control over their emission wavelengths and thermal activation, limiting their broad application in printing and dyeing technologies. Future research should focus on improving the stability of thermochromic inks against environmental influences, developing cost-effective materials, optimizing temperature response ranges to enhance comfort, and elucidating the formation mechanisms of CDs. These efforts will improve product quality, reduce cost, and advance the application of smart textiles.

The thiol-ene reaction is an efficient click chemistry approach that forms new compounds through the addition of thiol groups to allyl groups. To address issues such as the loss of natural hand feel in silk caused by traditional printing and dyeing methods, Wang’s et al. [

99] applied the thiol-ene reaction to covalently bond thermochromic pigments (VTPs) onto silk fibers. This process created strong thiol-ene covalent bonds that ensured stable and durable pigment adherence on the fiber surface (

Figure 12d). The team further employed UV-visible spectroscopy (UV-vis) and thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) to assess the thermochromic behavior and thermal stability of the VTPs. Results indicated that the material exhibited a bright red color at 25 °C, which gradually faded to nearly colorless as the temperature increased to 55 °C. Additionally, the possibility of blending thermochromic pigments with different colors and temperature response ranges in precise ratios was investigated for application to silk. This enabled the development of a thermochromic silk exhibiting multicolor changes. Experimental results demonstrated that the modified silk possessed excellent wash fastness and crock fastness, suggesting its broad potential for applications such as temperature sensors, environmental monitoring, wearable devices, and medical bandages. Future efforts should focus on simplifying equipment, reducing production costs, and optimizing spinning processes. To enhance thermochromic fiber properties, challenges in fabrication must be addressed. These include uneven pigment distribution during melt spinning and poor fiber uniformity in electrospinning. Successfully overcoming these hurdles will expand the fibers’ applications into areas such as anti-counterfeiting, wearable technology, and military camouflage.

Most thermochromic inks are hydrophilic, as is silk, which complicates achieving strong interfacial adhesion between the two. Conventional industrial silk dyeing involves multiple complex steps, including heating (40-90 °C), soaking (10-50 minutes), repeated washing and dehydration, and the use of chemical auxiliaries. This process results in substantial wastewater pollution and high energy consumption. Furthermore, reversible thermochromic materials show low reactivity, making them difficult to apply onto silk textiles [

94,

95,

99]. To overcome these challenges, Wang’s research group [

100,

101,

102,

103,

104,

105] proposed a novel, cost-effective approach combining continuous high-speed winding with dip-coating to enable low-cost, efficient, and scalable silk coloring (

Figure 12a-b). In this method, freshly drawn high-tenacity silk fibers from the spinning machine remain partially wet, with water-soluble sericin on the surface acting as a natural high-viscosity adhesive. This significantly improves adhesion between the silk fibers and thermochromic ink. Textiles produced via this technique withstand standard washing tests, exhibiting good color fastness without fading. However, long-term stability and large-scale production still require further verification.

Additionally, Wang’s team [

106] developed a corona-enhanced electrostatic printing method. This technique uses precise corona discharge control to generate a strong electrostatic field on the substrate, guiding the suspension for precise material deposition. The team also modified thermochromic materials and optimized their surface charge distribution, enabling rapid transfer of these materials within milliseconds (

Figure 12c). This advancement not only speeds up printing but also reduces costs and improves operational safety. Crucially, the method eliminates the need for binders common in traditional approaches, thereby avoiding related losses in material sensitivity during encapsulation.

3.3. Material Microencapsulation

Microencapsulation has become a widely adopted technique to improve the performance and broaden the application range of reversible thermochromic materials [

90,

92,

93]. For example, Matsui Pigment Chemical Industry Co., Ltd. utilizes this method to encapsulate reversible thermochromic dyes within microcapsules of 3-5 μm diameter, which are then firmly attached to fiber products via immersion dyeing. The microencapsulation approach allows textiles to exhibit vibrant colors and highly sensitive color-changing behavior, enabling diverse applications. However, this technique presents certain drawbacks: the presence of microcapsules can increase the fabric’s roughness; additionally, fabric breathability is reduced, resulting in lower wearer comfort; moreover, repeated washing and prolonged use gradually degrade the microcapsule structure, limiting color durability and overall lifespan. Among the various microcapsule fabrication methods, interfacial polymerization and in-situ polymerization are commonly employed [

88,

107,

108,

109].

In interfacial polymerization, the core material is usually distributed as the dispersed phase within a continuous phase containing shell material monomers. Additional shell monomer is then added to continue the polymerization, forming a polymer film on the core surface, and ultimately producing microcapsules. Common shell materials include urea-formaldehyde resin, polyamide, and polyurethane, which form dense microcapsules. However, scaling up interfacial polymerization poses challenges because the process is sensitive to interfacial conditions heavily influenced by mixing parameters. This method offers advantages such as low temperature operation, rapid polymerization, simple procedures, and good permeability of the shell material. Wang et al. [

110] prepared bistable thermochromic microcapsules (BTC-Ms) using interfacial polymerization. They mixed a green thermochromic compound with a MUF prepolymer and carried out interfacial polymerization at controlled pH and temperature, followed by cooling, washing, and drying to obtain microcapsules approximately 1 µm in size. These microcapsules can rapidly and reversibly switch between two color states, maintain stability without continuous energy input, and absorb and store heat through phase changes. The bistable color change results from donor-acceptor electron transfer, dynamic hydrogen bonding, and supercooling properties, enabling rapid color response under sunlight at room temperature, with excellent color stability and significant contrast remaining after 100 lighting cycles. Geng et al. [

98,

112] successfully prepared formaldehyde-free microcapsules via interfacial polymerization, as shown in

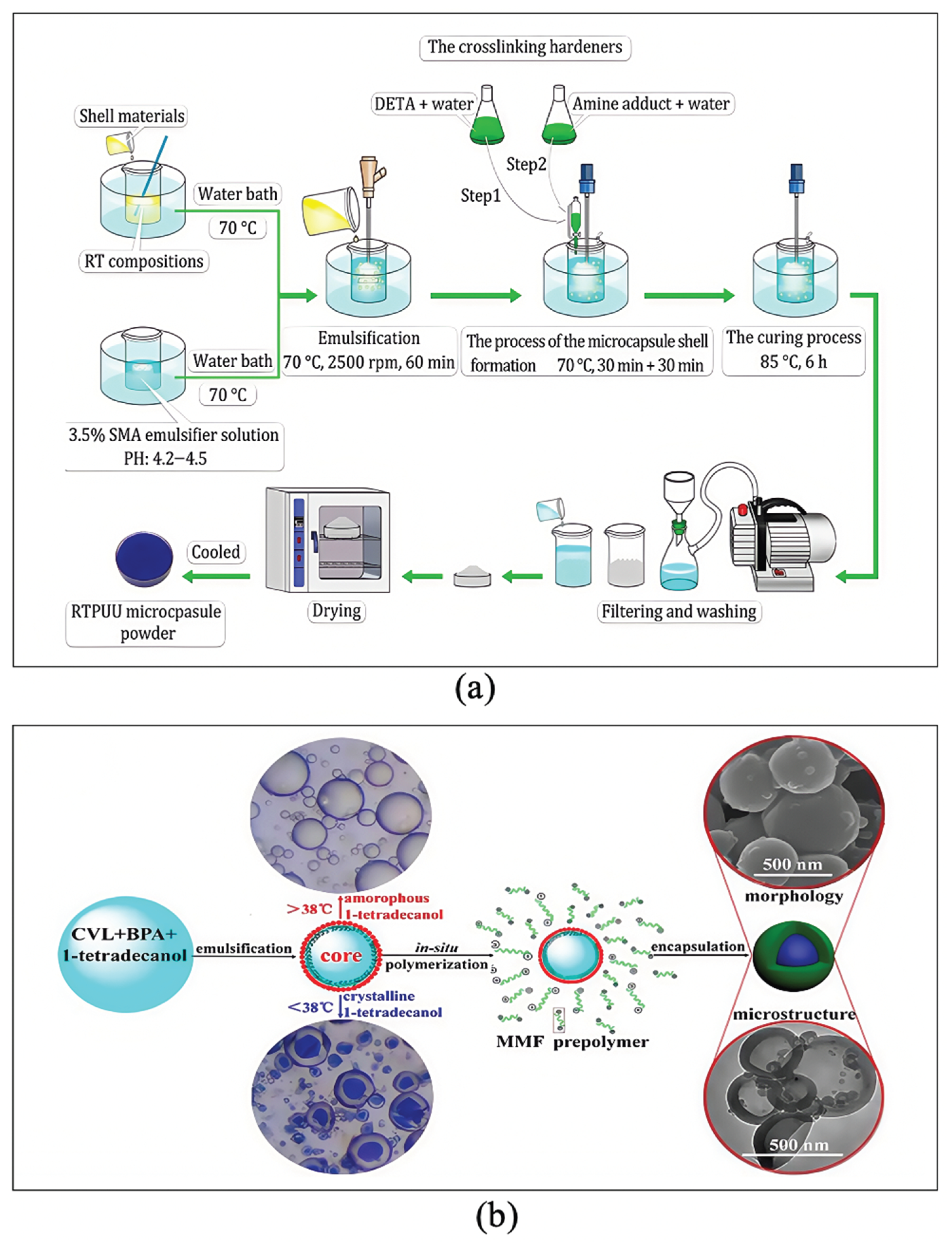

Figure 13(a). Over recent decades, thermochromic microcapsules with melamine-formaldehyde resin shells have been widely commercialized due to low material cost, ease of production, good sealing, and chemical resistance. Nevertheless, melamine-formaldehyde resin releases formaldehyde upon degradation, posing health risks. To address this issue, Liu et al. prepared formaldehyde-free microcapsules using thermochromic compounds as the core and polyurethane-urea (PUU) as the shell. The key to this approach is synthesizing the PUU shell using an HDI trimer, diethylenetriamine (DETA), and Epicure 8537-WY-60 (an epoxy resin amine adducts by HEXION, Springfield, OR, USA) as crosslinking agents, with CUCAT-U2 (a waterborne polyurethane catalyst from Guangzhou Yourun Corporation, Guangzhou, China) facilitating the reaction. During synthesis, parameters such as emulsification shear rate, core-to-shell mass ratio, and emulsifier concentration were controlled to optimize microcapsule performance. The resulting microcapsule powder exhibited good dispersibility in screen-printing inks and moderate particle size. The microcapsules showed stable thermochromic behavior, excellent thermal stability, UV aging resistance, solvent resistance, and acid-base durability, demonstrating potential for applications such as anti-counterfeiting.

As illustrated in

Figure 13(b), in-situ polymerization differs from interfacial polymerization in that the monomers and catalysts for the shell material are present either inside or outside the core droplets during capsule formation. The monomers can dissolve in the continuous phase of the capsule system, whereas the polymers cannot. Consequently, polymerization occurs at the core surface, where monomers continuously deposit and cross-link, forming a dense polymer shell around the core. Compared to interfacial polymerization, in-situ polymerization generally offers easier scalability due to a simpler reaction process and less stringent mixing control requirements. However, achieving uniform monomer distribution within the textile substrate during large-scale production can be challenging, potentially resulting in inconsistent thermochromic performance. Therefore, optimizing monomer impregnation and polymerization processes is essential to ensure consistent product quality. The advantages of in-situ polymerization include a broad selection of shell materials, facile control over microcapsule particle size and shell thickness, simple operation, and low cost [

111]. Li et al. [

113] prepared reversible thermosensitive color-changing microcapsules by in-situ polymerization using a composite core of crystal violet lactone, BPA, and tetradecyl alcohol, with urea-formaldehyde resin as the shell. This microencapsulation technique improves the thermal stability and durability of reversible thermochromic materials during use. The microcapsules were formulated into thermochromic inks for printing. Experimental results showed that when microcapsules composed 25% of the ink by mass, the printed samples exhibited optimum adhesion and color difference (ΔE) performance. This technology is applicable in printing and packaging fields such as warning labels, anti-counterfeiting, decoration, and aesthetic enhancement. Wang’s team [

114] developed bistable temperature-sensitive color-changing microcapsules (SDBTC-Ms) via in-situ polymerization, based on supercooling and spatially restricted electron transfer. This material stably exists in two distinct color states under the same environmental conditions: a colored state (ST I) and a colorless state (ST II). Transition between these states depends on the duration of temperature and light exposure. For instance, after stimulation at 60 °C for 3 minutes, the material maintains the ST II state for at least 150 hours; meanwhile, a 1-second stimulus rapidly restores the ST I state. Although the capsules display advantages including bistability, durability, and controllable switching, their complex synthesis and limited color range partially restrict widespread application. Li’s team [

115,

116,

117] synthesized thermochromic microcapsules (TC@MF) by in-situ polymerization. The microcapsules feature a thermochromic phase change material (TC-PCM) core and a methylcellulose (MF) shell. This design was aimed at enhancing color variety and photothermal conversion efficiency. These microcapsules were embedded in silicone rubber (SR) to form composites that exhibited high energy storage density, excellent cycling durability, and reversible thermochromic performance. Nevertheless, further investigation is needed to explore the potential application of these capsules in textiles and coatings.

Beyond interfacial and in-situ polymerization, several emerging microencapsulation techniques show potential for integrating thermochromic materials into textiles. Ultrasonic impregnation utilizes ultrasonic waves to improve the penetration and uniform distribution of thermochromic compounds within textile fibers. This technique effectively achieves deep and consistent coloration, reduces surface deposition, and enhances wash durability. Pickering emulsions [

118], which use solid particles as stabilizers, provide a stable and eco-friendly alternative to traditional surfactant-based emulsions. These emulsions enable the encapsulation of thermochromic dyes, improving their stability and controlled release. Additionally, extrusion and blown film processing have been adapted to produce thermochromic films or coatings that can be directly applied to textiles, offering continuous and scalable manufacturing [

119]. Miniemulsion polymerization [

120], a type of emulsion polymerization that forms very small droplets, facilitates the synthesis of highly stable and uniformly sized microcapsules with precise control over shell composition and morphology. These microcapsules can be incorporated into textile coatings or fibers, serving as a versatile platform for fabricating thermochromic smart textiles.

In summary, the fabrication of reversible thermochromic smart textiles involves several critical technologies, including fiber preparation, printing and dyeing techniques, and material microencapsulation. Fiber preparation focuses on embedding thermochromic materials within fibers, enhancing fabric durability and comfort. Printing and dyeing transfer thermochromic coatings onto fabric surfaces to achieve patterned color changes. Microencapsulation protects thermochromic materials, improving their stability and resistance to washing. Selecting an appropriate preparation method requires comprehensive evaluation of material properties, application requirements, and cost considerations to ensure optimal performance and economic efficiency. Future research should prioritize the development of more efficient and environmentally friendly fabrication methods to expand the applications of reversible thermochromic smart textiles.

4. Applications of Reversible Thermochromic Smart Textiles

Smart textiles fabricated from reversible thermochromic materials find applications in diverse areas including anti-counterfeiting, decoration and aesthetic enhancement, as well as intelligent management.

4.1. Anti-Counterfeiting

An ideal anti-counterfeiting smart fabric integrates unique, dynamic, difficult-to-replicate, stable, and durable reversible thermochromic properties. It requires robust anti-counterfeiting performance and durability suitable for practical applications, while providing intuitive and convenient authentication methods [

121,

122,

123,

124,

125,

126]. In this context, reversible thermochromic materials are highly valued in anti-counterfeiting technologies and are widely employed by many apparel brands in concealed embroidered labels and other applications [

21,

91,

92]. Li’s team [

115] developed an innovative temperature-sensitive ink mainly intended for anti-counterfeiting. By incorporating reversible thermochromic polyurethane (RTPUU) microcapsules into screen-printing ink, they created anti-counterfeiting labels featuring unique reversible thermal memory properties. These labels demonstrate strong color contrast during cooling and heating processes, significantly improving product identification and security, thus offering a novel solution for product anti-counterfeiting. Wang’s team [

99] synthesized multicolor CDs with thermally activated fluorescence for multidimensional information encryption. This ink, prepared via a precursor-directed approach, enables full-color emission from 460nm to 654nm by precisely adjusting the molecular structure of precursors and synthesis conditions. Furthermore, the fluorescence intensity of the CDs increases with temperature, exhibiting excellent thermochromic behavior. These findings are expected to advance the application of thermochromic CDs in advanced information encryption. They also provide new avenues for developing innovative anti-counterfeiting technologies.

4.2. Decoration and Beautification

The application of smart textiles in decoration and beautification demands the integration of multiple functional properties. Aesthetic aspects are critical, including strong visual appeal, trendy design, and personalized customization. In addition, factors such as color fastness, ease of maintenance, cost efficiency, and user comfort must be addressed. Considering these requirements, reversible thermochromic materials present an ideal solution for enhancing the decoration and beautification of smart textiles [

127]. For instance, the research team led by Yang [

128] combined thermosensitive microcapsules with humidity-sensitive color-changing technology and applied these microcapsules onto fabrics via screen printing. These microcapsules exhibit vivid color, high heat resistance, and solvent durability, enabling the fabric to respond to simultaneous temperature and humidity variations with notable color-changing performance.

Using reversible thermochromic materials to enhance textile decoration is highly feasible and offers unique creative opportunities. Firstly, these materials can be tailored to designers’ specifications, such as adjusting the color transition temperature and color spectrum, to satisfy the decorative requirements of varied occasions and styles. Moreover, they can be integrated with other textile techniques, including printing and embroidery, thereby further expanding design possibilities. As consumer demand for fashion and individuality grows, reversible thermochromic materials show broad application prospects across sectors including apparel and home textiles. These fabrics not only attract consumer attention but also increase product added value. Some reversible thermochromic materials, especially certain bio-based or biodegradable types, meet environmental standards while revitalizing textiles, thereby contributing to the sustainable transformation of the textile industry [

66].

4.3. Intelligent Management

The development of smart textiles requires a thorough evaluation of various properties and functional demands [

129]. Fundamental features such as environmental sensing, automatic regulation, data processing, communication, and material stability are essential for achieving functions like temperature regulation, humidity control, and health monitoring. To ensure satisfactory user experience, these fabrics must also meet criteria related to comfort, breathability, and biocompatibility. Additionally, wearability, lightweight design, and material compatibility are critical to accommodate diverse applications. Given these requirements, the use of reversible thermochromic materials is highly appropriate for thermal management, as they provide real-time feedback on body or ambient temperature, enabling effective monitoring. Applications include patient caps, protective clothing, firefighter uniforms, product packaging, and healthcare materials [

48,

130,

131,

132,

133,

134,

135,

136]. For instance, Zhang’s team [

137] developed a novel thermochromic phase change microcapsule with a sandwich-structured shell, serving as an indicator for thermal energy storage and real-time management. This material retains strong thermochromic performance after 500 thermal cycles. Although laboratory results are promising, its durability and reliability in long-term practical use require further validation. Moreover, the completeness of color change remains an aspect needing improvement. To extend the temperature indication range, Ge’s team [

138] created organic high-temperature reversible thermochromic materials that operate above 100 °C and exhibit rapid color transitions from blue to red. For example, when placed on a 100 °C hot plate, color change begins within one second, and the entire pattern turns red after five seconds. This material also demonstrates good thermal stability and reusability, maintaining color restoration after multiple heating and cooling cycles. It is suitable for thermal indicators in high-temperature environments. However, practical applications demand complex monomer structural designs to regulate the thermochromic temperature threshold, increasing production costs. Furthermore, the specific operating temperature range limits its use in certain scenarios. To improve environmental adaptability and thermal management efficiency, Zheng’s team [

139] developed a smart fabric exhibiting temperature-dependent color changes. Through dynamic spectral modulation, the fabric absorbs more solar energy at low temperatures for heating, while reducing solar absorption under high temperatures to achieve cooling. Additionally, reversible thermochromic materials have found widespread use as temperature indicators in commercial packaging [

64].

4.4. Challenges

Despite progress and potential demonstrated by reversible thermochromic materials in smart textiles, several challenges limit their widespread application and commercial viability. A primary issue concerns their durability under real-world use conditions. These materials are sensitive to repeated washing, mechanical abrasion, and prolonged ultraviolet exposure, all of which can impair their color-changing performance and shorten functional lifespan. Although microencapsulation provides some protection, the capsules remain susceptible to damage during laundering or abrasion, potentially releasing the thermochromic dye and negatively affecting the textile’s appearance and functionality [

123,

125].

Moreover, the restricted color range and possible hysteresis impose further constraints. Organic thermochromic materials offer a broader color spectrum than inorganic ones; however, the available options may still fall short of requirements for precise color matching or intricate designs. Hysteresis, defined as the difference between color transition temperatures during heating and cooling, can reduce temperature indication accuracy and reliability.

Toxicity also represents a significant concern, particularly regarding certain organic dyes and solvents used in thermochromic formulations. Compliance with regulations and consumer safety demands the development of environmentally friendly and biocompatible alternatives. The use of natural dyes such as anthocyanins combined with water-based microencapsulation methods can mitigate some risks; nevertheless, further studies are necessary to confirm the long-term safety of these materials.

Sustainability constitutes a critical factor as well. The production of some thermochromic materials consumes high energy and depends on nonrenewable resources. Developing sustainable synthesis methods utilizing bio-based or recycled materials and improving the recyclability of thermochromic textiles are essential steps to reduce environmental impact. Life cycle assessments can offer valuable insights into the overall sustainability of different thermochromic materials and integration approaches, guiding more responsible design and manufacturing decisions.

Beyond current applications, reversible thermochromic fabrics, as temperature-responsive smart materials, exhibit significant potential for innovative uses. For instance, they can serve as skincare monitoring devices by visualizing skin temperature to assist in selecting appropriate products. Moreover, smart curtains and adaptive shading systems can automatically adjust light transmittance and shading according to temperature variations, improving building energy efficiency. In the fashion and art sectors, this fabric can be incorporated into interactive installations to increase audience engagement and enable personalized customization, producing unique color patterns based on individual body temperature.

Concerning emerging integration technologies, reversible thermochromic fabrics can be combined with smart sensors to achieve precise temperature monitoring and feedback. Nanotechnology can further enhance their sensitivity and durability. Integration with 5G-IoT allows real-time transmission of temperature data and remote monitoring. Additionally, artificial intelligence can analyze temperature data to provide decision support, broadening potential applications. The convergence of these innovative approaches and integration techniques will enable the extensive application of reversible thermochromic fabrics across various fields. This advancement underscores their broad market prospects and substantial potential value.

5. Conclusion and Outlook

This review systematically summarizes the research progress and potential applications of reversible thermochromic materials in smart textiles. The integration of these materials with textile substrates effectively mitigates inherent limitations and enhances color-changing performance, durability, and application scope. Future research should prioritize biosafety and environmental sustainability. It also needs to develop efficient and cost-effective integration strategies to improve color change sensitivity, chromatic expression, and environmental stability.

Although several challenges remain for large-scale commercialization, the field offers substantial opportunities through targeted innovation. Several green and biocompatible synthesis routes exist, including solvent-free microencapsulation, water-based thermochromic inks, and automated production. These methods can solve the current cost and scalability issues, leading to improved market acceptance. Performance optimization requires efforts in three areas. First is the molecular design of thermochromic materials. Second is the development of novel composite microcapsule shells. Third is the refinement of post-finishing processes. Together, these improvements will enhance substrate compatibility, response speed, color vividness, and long-term stability.

Injecting technological elements into traditional crafts expands the application scenarios of thermochromic materials in the cultural and creative industries. Embedding reversible thermochromic materials into intangible cultural heritage crafts such as Kesi silk tapestry weaving is expected to bring new application opportunities. For instance, ancient kesi often used precious materials like gold threads and peacock feathers to enhance its artistic value. Similarly, embedding thermochromic fibers in kesi silk tapestry weaving can produce smart home textiles with dynamic light and shadow effects.

Future technological exploration may focus on the following areas: employing aerosol jet printing to prepare uniform VO2 thin films at low temperatures to improve compatibility with various textiles; incorporating nanocarbon materials such as graphene or MXenes to enhance mechanical properties and wear resistance of coatings; or integrating self-healing polymers into microcapsule structures to provide autonomous repair capabilities, thereby extending service life. Coordinated progress in these strategies will effectively promote the development and application of a new generation of high-performance, multifunctional smart textiles.

To facilitate the transition from laboratory research to industrial production, it is crucial to optimize scalable synthesis pathways, establish standardized quality control systems, and develop energy-efficient manufacturing technologies. These initiatives align with global sustainable development trends. With ongoing advances in materials science and integration technologies, reversible thermochromic smart textiles show considerable commercial potential. Continuous innovation addressing key challenges will enable their widespread application and propel the textile industry into a new phase of intelligence, multifunctionality, and sustainability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Qiucheng Lu, Xiaohui Zhao; Data Curation, Wang Xu, Ziqiang Bi, Hailin Li; project administration, Yuqing Liu; Funding Acquisition, Qiucheng Lu, Xiaohui Zhao, Yuqing Liu. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by China National Textile and Apparel Council Science and Technology Guidance Project, grant number 2020116. QINGLAN Project of Jiangsu Province of China, Pre-research project of Suzhou City University (2022SGY007) and Devices and Suzhou Basic Research Project (SJC2023003). General Education Elective Course Project of Suzhou City University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT to improve the language and readability. After careful review and editing of the AI-generated content, the authors take full responsibility for the final publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Behera, S.A.; Panda, S.; Hajra, S.; et al. Current trends on advancement in smart textile device engineering. Advanced Sustainable Systems 2024, 8(12), 2400344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Luan, S.; Tian, M.; et al. Smart wearable fibers and textiles: status and prospects. Nanoscale 2025, 39, 22733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadesse, M.G.; Abate, M.T.; Lübben, J.F.; et al. Recycling and sustainable design for smart textiles − a review. Advanced Sustainable Systems 2025, 9(8), 2401072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.R.; Afroj, S.; Novoselov, K.S.; et al. Inkjet-printed 2D heterostructures for smart textile micro-supercapacitors. Advanced Functional Materials 2024, 34(52), 2410666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khuje, S.; Islam, A.; Soles, J.; et al. Smart metallized textiles with emissivity tuning. ACS Applied Engineering Materials 2024, 2(11), 2698–2704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liu, Z.; Xu, S.; et al. Electrostatic smart textiles for braille-to-speech translation. Advanced Materials 2024, 36(24), 2313518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Mouthuy, P.-A. Advancing smart biomedical textiles with humanoid robots. Advanced Fiber Materials 2024, 6, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Zhang, C.; Wang, F.; et al. Smart textiles for personalized sports and healthcare. Nano-Micro Letters 2025, 17, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, M.; Li, Z.; Bian, L.; et al. Two-dimensional materials van der Waals assembly enabling scalable smart textiles. Materials Science and Engineering: R: Reports 2025, 163, 100915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Yan, B.; Zhou, M.; et al. MXene nanosheets assembled onto cationic-modified cotton for smart multiprotection textiles. ACS Applied Nano Materials 2024, 7(11), 13568–13578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X.; Xiao, D.; Wei, J.; et al. Microstructure-tailored shape-memory polyurethane nanofiber yarns for smart textiles. Materials Today Communications 2025, 42, 111464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toprak-Cavdur, T.; Duzyer Gebizli, S.; Tezel, S.; et al. Developing thermochromic cotton fabric production for smart textile applications. Cellulose 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, H.K.; Reddy, T.S.; Choi, M.S. Synthesis and Reversible Thermochromic Behavior of Diketopyrrolopyrrole Dyes. Dyes and Pigments 2025, 8(239), 112753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Wang, Y.; Cai, W.; et al. Color-changing smart textiles for zero-carbon radiative thermal management: a review. Applied Materials Today 2025, 44, 102768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Ma, X.; Xue, X.; et al. In-situ growth of photochromic microcapsules for the preparation of fast-response, high color-fastness smart textiles. Composites Communications 2025, 57, 102467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Cheng, W.; Liu, F.; et al. Hollow cholesteric liquid crystal elastomer fiber with synergistically enhanced resilience and mechanochromic sensitivity. Advanced Science 2025, 12(34), e04487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, F.; Shen, L.; et al. Robust and long-lived photochromic textiles with spiropyran derivatives. ACS Applied Optical Materials 2025, 3(2), 346–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Kim, J.; Lee, J.; et al. Recent progress on 2D-material-based smart textiles: materials, methods, and multifunctionality. Advanced Engineering Materials 2025, 27(12), 2500188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.; Manivannan, R.; Jayasudha, P.; et al. Thermal responsive fluoran based microcapsule composite material with SiO2: a stable and reversible thermochromic indicator for smart fabric application and its phase change behavior study. Dyes and Pigments 2025, 245, 113205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Ren, G.; Hu, S.; et al. Bifunctional electrospun nanofiber membranes with thermoregulatory and thermochromic properties. ACS Applied Polymer Materials 2025, 7(16), 10942–10952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Zhang, X.; Fang, C.; et al. Discoloration mechanism, structures and recent applications of thermochromic materials via different methods: a review. Journal of Materials Science and Technology 2018, 34, 2225–2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Wang, J.; Xie, J.; et al. Reversible thermochromic organosilicon fibers based on TiO2@AgI composites: preparation, properties, and potential applications. Advanced Materials 2025, 37(39), 2505638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Wang, Y.; Fan, W.; et al. Adaptive dynamic smart textiles for personal thermal-moisture management. European Polymer Journal 2024, 206, 112777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Hu, X.; Ye, C.; et al. Bilayer smart and multifunctional camouflage textiles integrating adaptive visible stealth, infrared concealment, and electromagnetic interference shielding. ACS Applied Polymer Materials 2025, 7(11), 7350–7359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Qi, T.; Wang, J.; et al. A thermochromic hydrated ionic polymer with an adjustable transition temperature for smart windows and temperature monitoring. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2025, 17(26), 38427–38437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Zheng, C. Physically cross-linked hydrogel designed for thermochromic smart windows: balance between thermal stability and processability. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 2025, 13(6), 2574–2585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Lin, X.; Peng, Y.; et al. Super-flexible and thermochromic core-sheath fiber sensors for body temperature visualization and strain sensing. Chemical Engineering Journal 2025, 522, 167987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Peng, Y.; Wei, X.; et al. Robust multistage thermochromic superhydrophobic coating prepared by a facile one-step spray coating method. Progress in Organic Coatings 2025, 210, 109625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Zhang, Y.; Zong, H.; et al. Photochromic and thermochromic inks based on supramolecular complexes of viologens and cyclodextrin for printable anticounterfeiting applications. Chemical Engineering Journal 2025, 507, 160650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miguel, M.P.; Penelas, M.J.; Arenas, G.F.; et al. Effect of silica nanoshell on the stability and thermochromic properties of monoclinic VO2 particles dispersed in Poly(vinylbutyral) films. Materials Today Communications 2025, 44, 111858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo-Araujo, A.C.; Salomão, R.; Berardi, U.; et al. Design and characterization of a SiO2-TiO2 coating containing organic and inorganic thermochromic pigments and optimized with TiO2-P25 for improved long-term performance in energy-efficient roofing. Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells 2025, 289, 113655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savorianakis, G.; Martin, N.; Santos, A.J.; et al. Optical and electrical properties of thermochromic VO2 thin film combined with Au or Zr-containing compounds nanoparticles. Optics & Laser Technology 2025, 192 (Pt D), 113847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Xin, C.; Ma, M.; et al. Thermochromic reversible luminescence in Bi3+-doped Cs2ZrCl6 perovskites for multi-level optical anti-counterfeiting. Ceramics International 2025, 51 26 (Pt B), 50103–50111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, W.; Zhao, X.-G.; Klarbring, J.; et al. Thermochromic lead-free halide double perovskites. Advanced Functional Materials 2019, 29(10), 1807375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Wu, W.; Fei, W.; et al. Multistimulus-responsive chromic textile for smart wearable display, sensor, and camouflage. Chemistry of Materials 2025, 37(14), 5118–5128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Qin, Z.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Engineered thermochromic inks from reversible to irreversible color transitions for dynamic anticounterfeiting and logic-enabled sensing. Langmuir 2025, 41(30), 20116–20126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaszczak-Kuligowska, M.; Sąsiadek-Andrzejczak, E.; Safandowska, M.; et al. Thermochromic textile sensors for temperature measurements. Measurement 2025, 257 (Pt C), 118698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, A.; Ming, C.; Pei, Y.; et al. Controllable thermochromic luminescence in SrMoO4: Eu/Tb by nonradiative relaxation and local symmetry for anti-counterfeiting and high-temperature sensing applications. Optical Materials 2025, 169, 117534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordova, D.L.M.; Zhou, Y.; Milligan, G.M.; et al. Sensitive thermochromic behavior of InSeI, a highly anisotropic and tubular 1D van der Waals crystal. Advanced Materials 2024, 36, e2312597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Lei, L.; Zhao, B.; et al. High performance reversible thermochromic composite films with wide thermochromic range and multiple colors based on micro/nanoencapsulated phase change materials for temperature indicators. Composites Science and Technology 2023, 240, 110091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, L.; Yu, W.; Wu, Z.; et al. Optically controlled thermochromic switching for multi-input molecular logic. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2022, 61, e202212483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tingting, X.; Han, Y.; Ni, Y.; et al. Oxindolyl-based radicals with tunable mechanochromic and thermochromic behavior. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2024, 63, e202414533. [Google Scholar]

- Baron, M.G.; Elie, M. Temperature sensing using reversible thermochromic polymeric films. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2003, 90, 271–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Tan, J.; Liu, H.; et al. Shape-stabilized flexible thermochromic films with one-sided adhesion via gradient crosslinking strategy for temperature indicating. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science 2024, 677, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, C.F.; Wu, A.B. Studies on the synthesis and thermochromic properties of crystal violet lactone and its reversible thermochromic complexes. Thermochimica Acta 2005, 425, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Ji, X.; Zeng, C.; et al. A sultone-based reversible dark red–yellow conversion thermochromic colorant with adjustable switching temperature. Color Technology 2018, 135, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Zhang, S.; Jin, X.; et al. Thermal-responsive photonic crystal with function of color switch based on thermochromic system. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2019, 11, 39125–39131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Li, W.; Han, N.; et al. Facile flexible reversible thermochromic membranes based on micro/nanoencapsulated phase change materials for wearable temperature sensor. Applied Energy 2019, 247, 615–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, D.; Liu, H.; Wang, X. Preparation and performance study of thermochromic microcapsules with three components. New Chemical Materials 2020, 48(7), 76–80. [Google Scholar]

- Seeboth, A.; Lötzsch, D.; Ruhmann, R. First example of a non-toxic thermochromic polymer material -- based on a novel mechanism. Journal of Materials Chemistry C 2013, 1, 2811–2816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoo, H.E.; Azlan, A.; Tang, S.T.; et al. Anthocyanidins and anthocyanins: colored pigments as food, pharmaceutical ingredients, and the potential health benefits. Food Nutrition Research 2017, 61, 1361779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lötzsch, D.; Ruhmann, R.; Seeboth, A. Thermochromic biopolymer based on natural anthocyanidin dyes. Open Journal of Polymer Chemistry 2013, 3, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, V.A.; de Arruda, I.N.Q.; Stefani, R. Active chitosan/PVA films with anthocyanins from Brassica oleraceae (red cabbage) as time–temperature indicators for application in intelligent food packaging. Food Hydrocolloids 2015, 43, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; de Haan, L.T.; Debije, M.G.; et al. Liquid crystal-based structural color actuators. Light: Science & Applications 2022, 11, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brannum, M.T.; Steele, A.M.; Venetos, M.C.; et al. Light control with liquid crystalline elastomers. Advanced Optical Materials 2019, 7(6), 1801683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.Q.; Tang, Y.; Huang, Z.Y.; et al. A dual-responsive liquid crystal elastomer for multi-level encryption and transient information display. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2023, 62, e202313728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, J.; Stwodah, R.M.; Vasey, C.L.; et al. Thermochromic fibers via electrospinning. Polymers 2020, 12(4), 842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Zhao, J.; Wu, L.; et al. Polymer network film with double reflection bands prepared using a thermochromic cholesteric liquid crystal mixture. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2024, 16, 18001–18007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Rasines Mazo, A.; Gurr, P.A.; et al. Reversible nontoxic thermochromic microcapsules. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2020, 12, 9782–9789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seeboth, A.; Ruhmann, R.; Muhling, O. Thermotropic and thermochromic polymer based materials for adaptive solar control. Materials 2010, 3, 5143–5168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitov, M. Cholesteric liquid crystals with a broad light reflection band. Advanced Materials 2012, 24, 6260–6276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Gao, H.; Ren, X.; et al. Regulatable thermochromic hydrogels via hydrogen bonds driven by potassium tartrate hemihydrate. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 2019, 7, 15036–15043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Yang, Y.; Valenzuela, C.; et al. Mechanochromic, shape-programmable and self-healable cholesteric liquid crystal elastomers enabled by dynamic covalent boronic ester bonds. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2022, 61, e202116219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, T.; Yuan, D.; Liu, W.; et al. Thermochromic cholesteric liquid crystal microcapsules with cellulose nanocrystals and a melamine resin hybrid shell. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2022, 14, 4588–4597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlafmann, K.R.; Alahmed, M.S.; Pearl, H.M.; et al. Tunable and switchable thermochromism in cholesteric liquid crystalline elastomers. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2024, 16(18), 23780–23787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosby, P.H.N.; Netravali, A.N. Green thermochromic materials: a brief review. Advanced Sustainable Systems 2022, 6(9), 2200208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Zhou, L.; Li, B.; et al. Enhanced thermochromic performance of VO2 nanoparticles by quenching process. Nanomaterials 2023, 13(15), 2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Q.; Liu, C.; Wang, N.; et al. Periodic micro-patterned VO2 thermochromic films by mesh printing. Journal of Materials Chemistry C 2016, 4, 8385–8391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, S.; Tang, Z.; Li, D.; et al. A notable reversible thermochromic (3,3-difluoropyrrolidinium)2CuCl4 with ferroelectricity and ferroelasticity. Chemical Engineering Journal 2023, 466, 143188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, P.; Huang, W.-X.; Yan, J.-Z.; et al. Preparation and thermochromic property of VO2/mica pigments. Materials Research Bulletin 2011, 46, 966–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Lv, W.; Feng, J.; et al. Emerging thermochromic perovskite materials: insights into fundamentals, recent advances and applications. Advanced Functional Materials 2024, 34(37), 2402234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Xie, D.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Flexible VO2 films for in-sensor computing with ultraviolet light. Advanced Functional Materials 2022, 32(29), 2203074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Fan, W.; Li, D.; et al. Smart thermal management textiles with anisotropic and thermoresponsive electrical conductivity. Advanced Materials Technologies 2019, 5(1), 1900599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Marco, M.L.; Smith, O.; Thorimbert, F.; et al. Self-regulating VO2 photonic pigments. Chemistry of Materials 2023, 35, 7164–7174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Civan, L.; Kurama, S. A review: preparation of functionalised materials/smart fabrics that exhibit thermochromic behaviour. Materials Science and Technology 2021, 37, 1405–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Liu, M.; Kong, L.; et al. Recent progress in VO2 smart coatings: strategies to improve the thermochromic properties. Progress in Materials Science 2016, 81, 1–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, S.; Yang, D.; Ahmad Kayani, A.B.; et al. Solution-processed VO2 nanoparticle/polymer composite films for thermochromic applications. ACS Applied Nano Materials 2022, 5, 10280–10291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhu, M.; Tian, F.; et al. Polychrome photonic crystal stickers with thermochromic switchable colors for anti-counterfeiting and information encryption. Chemical Engineering Journal 2021, 426, 130683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; et al. Bionic structural coloration of textiles using the synthetically prepared liquid photonic crystals. Small 2024, 20, e2302550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, F.; Klarbring, J.; Zhang, B.; et al. Remarkable thermochromism in the double perovskite Cs2NaFeCl6. Advanced Optical Materials 2023, 12(8), 2301102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauvreau, B.; Guo, N.; Schicker, K.; et al. Color-changing and color-tunable photonic bandgap fiber textiles. Optics Express 2008, 16(20), 15677–15693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, G.; et al. Fabrication of patterned photonic crystals with brilliant structural colors on fabric substrates using ink-jet printing technology. Materials & Design 2017, 114, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Q.; Ding, C.; Li, Q.; et al. Rapid fabrication of robust, washable, self-healing superhydrophobic fabrics with non-iridescent structural color by facile spray coating. RSC Advances 2017, 7, 8443–8452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Liu, J.; Sun, J.; et al. Biomimetic thermally responsive photonic crystals film with high robustness by introducing thermochromic dyes. Progress in Organic Coatings 2023, 183, 107681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yin, T.; Ge, J. Thermochromic photonic crystal paper with integrated multilayer structure and fast thermal response: a waterproof and mechanically stable material for structural-colored thermal printing. Advanced Materials 2024, 36, e2309344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, H.; Liu, F.; Wang, Z.; et al. Bio-inspired dual-responsive photonic crystal with smart responsive hydrogel for pH and temperature detection. Materials & Design 2023, 233, 112242. [Google Scholar]

- Mun, S.; Lee, S.; Bae, K.J.; et al. Bio-imitative synergistic color-changing and shape-morphing elastic fibers with a liquid metal core. Advanced Fiber Materials 2024, 6, 900–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Gao, Y.; Cai, Q.; et al. Cholesterol-substituted spiropyran: photochromism, thermochromism, mechanochromism and its application in time-resolved information encryption. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science 2024, 665, 545–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, X.; Wu, Z.; Peng, H. Minireview on application of microencapsulated phase change materials with reversible chromic function: advances and perspectives. Energy & Fuels 2022, 36(15), 8054–8065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.H.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, X.X.; et al. Reversible thermochromic microencapsulated phase change materials with silane-terminated polyurethane shell. Journal of Energy Storage 2025, 119, 116329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Yan, W.; Cui, C.; et al. Bioinspired thermochromic textile based on robust cellulose aerogel fiber for self-adaptive thermal management and dynamic labels. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2023, 15(40), 47577–47590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Wang, J.X.; Li, Y.; et al. Multilevel information encryption based on thermochromic perovskite microcapsules via orthogonal photic and thermal stimuli responses. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 10874–10884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinquino, M.; Prontera, C.T.; Giuri, A.; et al. Thermochromic printable and multicolor polymeric composite based on hybrid organic–inorganic perovskite. Advanced Materials 2024, 36(2), 2307564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.L.; Lou, Q.; Lv, C.F.; et al. Bright and multicolor chemiluminescent carbon nanodots for advanced information encryption. Advanced Science 2019, 6, 1802331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wen, H.; Zhang, G.; et al. Multifunctional conductive hydrogel/thermochromic elastomer hybrid fibers with a core–shell segmental configuration for wearable strain and temperature sensors. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2020, 12(6), 7565–7574. [Google Scholar]

- Strižić Jakovljević, M.; Lozo, B.; Gunde, M.K. Identifying a unique communication mechanism of thermochromic liquid crystal printing ink. Crystals 2021, 11(8), 876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, X.; Wu, S.; Huang, F.; et al. Smart textiles with self-disinfection and photothermochromic effects. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2021, 13, 2245–2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, X.; Li, W.; Wang, Y.; et al. Reversible thermochromic microencapsulated phase change materials for thermal energy storage application in thermal protective clothing. Applied Energy 2018, 217, 281–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Huang, J.; He, Y.; et al. Preparation of multicolor carbon dots with thermally turn-on fluorescence for multidimensional information encryption. Chinese Chemical Letters 2024, 35(1), 108420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Hou, C.; Li, Y.; et al. Microfluidic spinning of editable polychromatic fibers. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science 2020, 558, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, T.; He, A.; Huang, Z.; et al. Silk-based flexible electronics and smart wearable textiles: progress and beyond. Chemical Engineering Journal 2023, 474, 145534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Yu, Z.; Li, K.; et al. Facile and effective fabrication of highly UV-resistant silk fabrics with excellent laundering durability and thermal and chemical stabilities. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2019, 11, 27426–27434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Ren, J.; Ye, C.; et al. Thermochromic silks for temperature management and dynamic textile displays. Nano-Micro Letters 2021, 13(5), 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]