1. Introduction

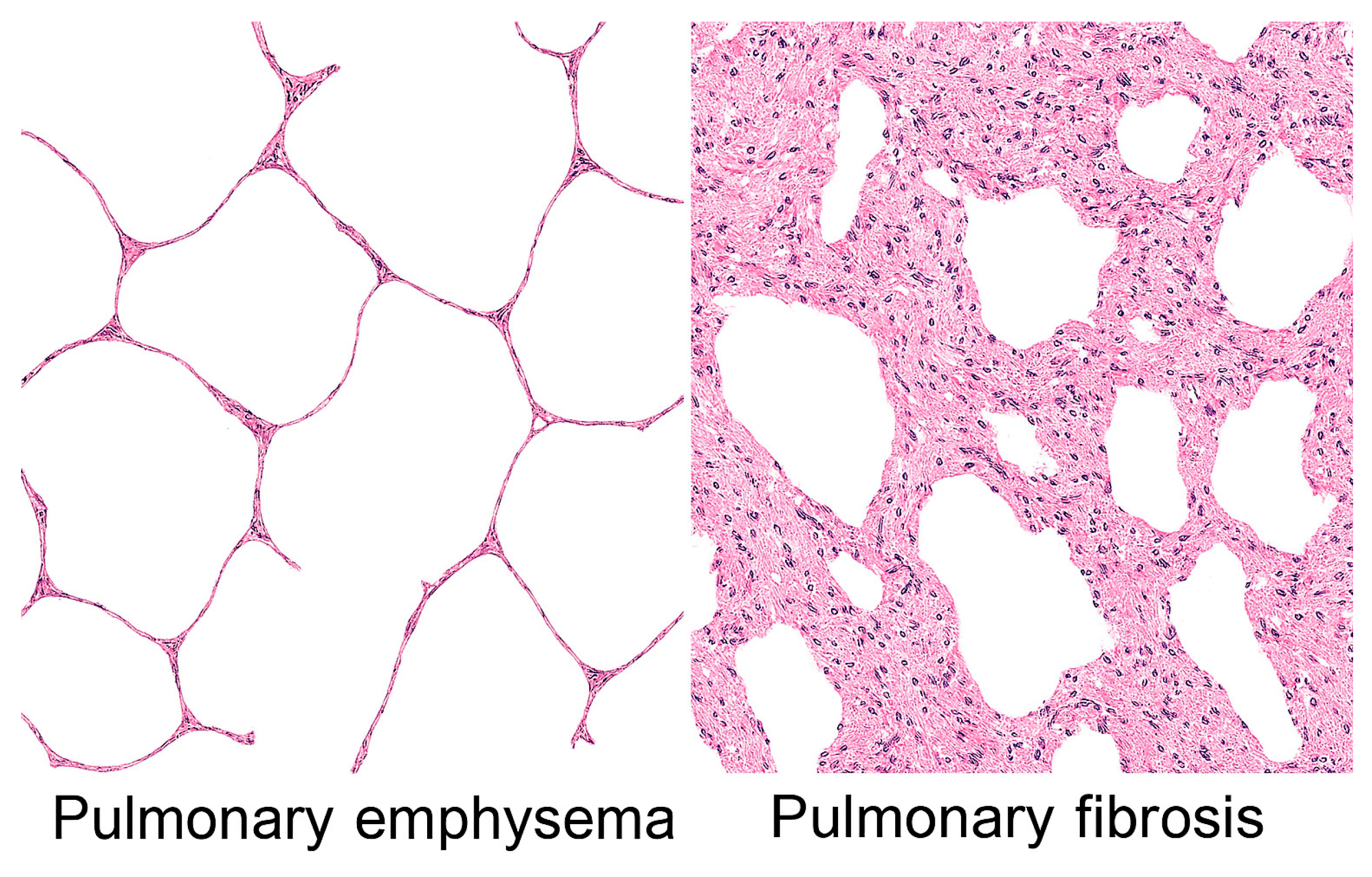

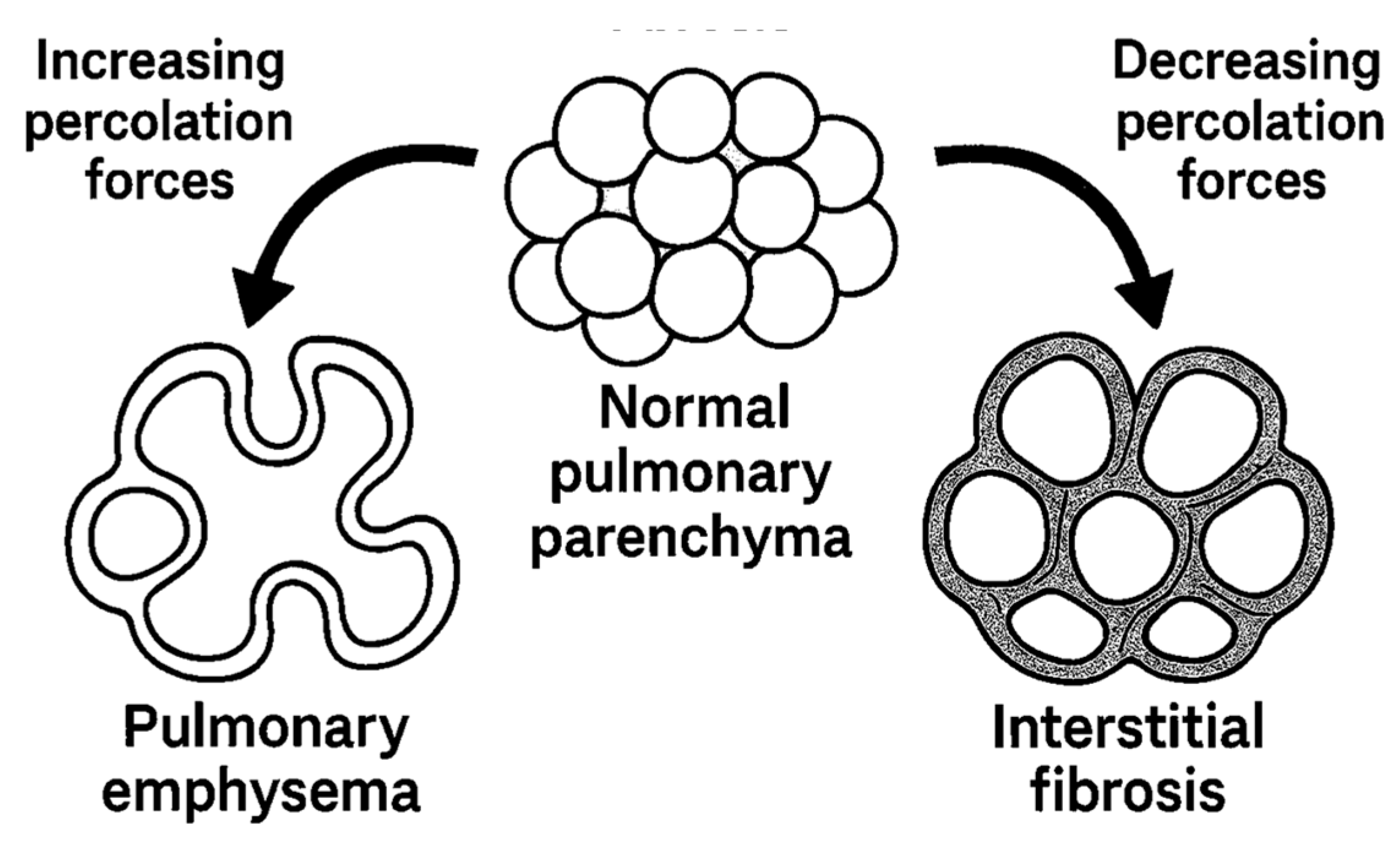

The human lung is a complex biological network involving a delicate balance between extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins, cellular populations, and mechanical forces that maintains both structural integrity and functional compliance. When this equilibrium is disrupted by chronic inflammation, the lung can follow one of two dramatically different pathological paths: emphysema, characterized by progressive destruction of alveolar walls and airspace enlargement, or interstitial fibrosis, marked by excessive collagen deposition and tissue stiffening (

Figure 1).

The apparent paradox involving similar inflammatory stimuli, such as cigarette smoke, environmental pollutants, or autoimmune processes that result in either tissue destruction or excessive tissue formation, has remained poorly understood [

1]. Traditional explanations have focused on differences in inflammatory cell populations, cytokine profiles, or genetic susceptibility [

2,

3]. However, these factors alone cannot fully explain why inflammation sometimes leads to a self-propagating wave of tissue destruction, while at other times it culminates in progressive fibrotic consolidation.

Percolation theory, involving critical threshold behaviors, provides a useful framework for understanding these divergent outcomes [

4]. Below a critical point, damage remains localized and contained, but above this threshold, damage or connectivity can propagate throughout the entire system. It is proposed that percolation phenomena govern whether inflammatory damage cascades into either emphysema or interstitial fibrosis.

Central to these percolation transitions is the process of extracellular matrix crosslinking, which alters tissue mechanical properties and resistance to degradation [

5]. This concept is supported by a study using beta-aminopropionitrile, an elastin and collagen crosslink inhibitor, to modify cadmium chloride-induced lung injury [

6]. Treatment with this agent produced pulmonary emphysema instead of interstitial fibrosis, emphasizing the multiscale evolution of lung disease, involving molecular changes that are reflected by remodeling of lung structure.

The current paper further explores this phenomenon by integrating crosslink formation with percolation forces, highlighting the development of mechanical and biochemical feedback loops that can steer tissue toward either degenerative or fibrotic outcomes. Based on this analysis, we hypothesize that pulmonary emphysema and interstitial fibrosis may be two sides of the same coin, involving probabilistic outcomes related to percolation thresholds.

2. Percolation Theory and Biological Networks

Percolation theory describes how local connections in a network determine global connectivity and system-wide properties [

7]. It provides a framework for analyzing how randomly occupied sites or bonds in a lattice affect the emergence of interconnected spanning clusters that extend across the entire system. Below a critical occupation probability (the percolation threshold), only small, isolated clusters exist. Above this threshold, spanning clusters suddenly emerge that fundamentally change the network's properties.

In biological tissues, percolation concepts apply to multiple scales and contexts. At the molecular level, crosslinks between matrix proteins form a network whose connectivity determines mechanical properties [

8]. At the cellular level, the presence or absence of cells maintaining tissue architecture affects structural integrity [

9]. At the tissue level, the continuity of alveolar walls determines whether the gas exchange surface area is preserved or lost.

The lung extracellular matrix forms a three-dimensional percolation network where collagen fibers, elastin filaments, proteoglycans, and other matrix components create a mechanically integrated structure [

10]. In healthy lung tissue, this network operates above the percolation threshold where the matrix is fully connected, creating a continuous mechanical scaffold that distributes stress uniformly and resists local damage. Crosslinks between matrix proteins are crucial for maintaining this connected state, providing the covalent bonds that link individual proteins into a functional network [

11].

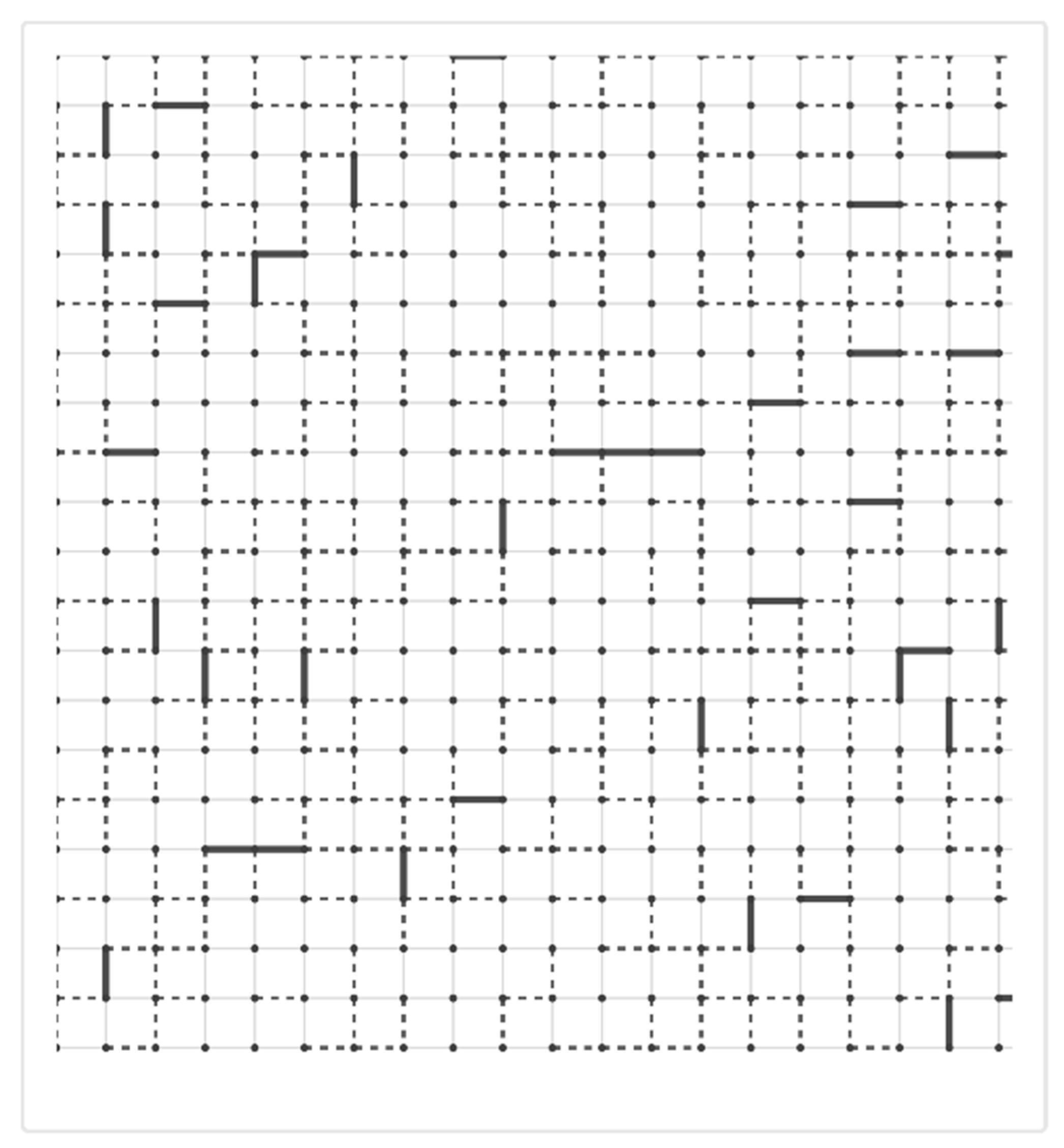

When inflammation introduces proteolytic enzymes, oxidative stress, and mechanical forces that damage matrix components, the tissue approaches a critical percolation threshold from above. If crosslink density falls below a critical value, or if too many structural connections are severed, the network fragments [

12]. This fragmentation represents a percolation transition involving a loss of global connectivity and the emergence of mechanical instability. In emphysema, this downward percolation transition leads to progressive tissue destruction (

Figure 2).

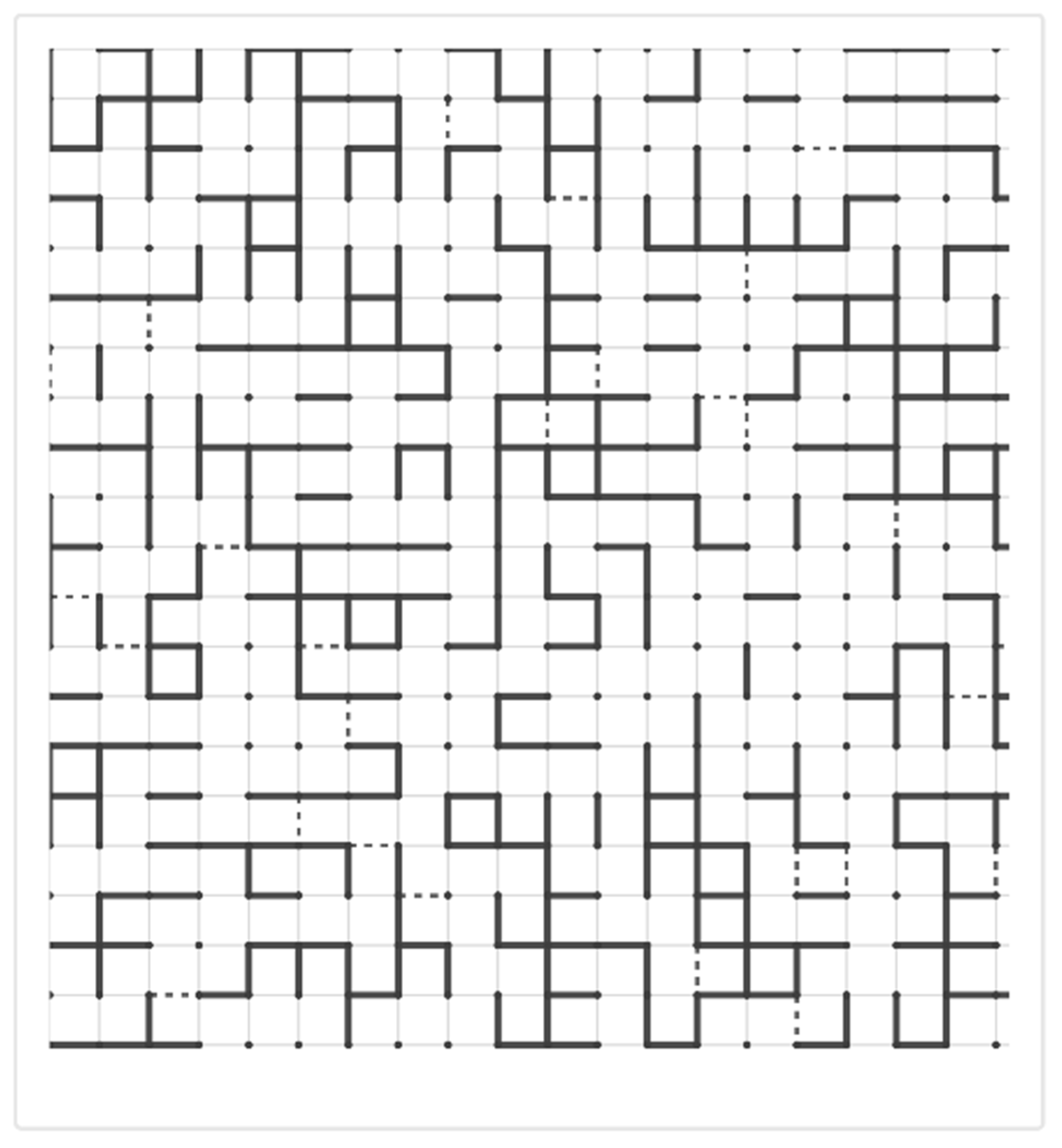

Conversely, excessive crosslinking during repair processes can drive tissue toward a different outcome. When crosslink density significantly increases above normal levels, the matrix becomes rigid and resistant to normal remodeling [

13]. This upward transition through a rigidity percolation threshold creates a mechanically stiff network that resists degradation and continues to accumulate additional matrix. In fibrosis, this transition manifests as progressive tissue stiffening and loss of functional compliance (

Figure 3).

The concept of percolation thresholds helps explain why the progression of lung disease often appears non-linear. Patients may maintain relatively stable lung function despite ongoing inflammation until a critical threshold is crossed, after which rapid deterioration occurs. This threshold behavior reflects the fundamental physics of percolation transitions in which small changes near critical points can have disproportionate effects on system-wide properties.

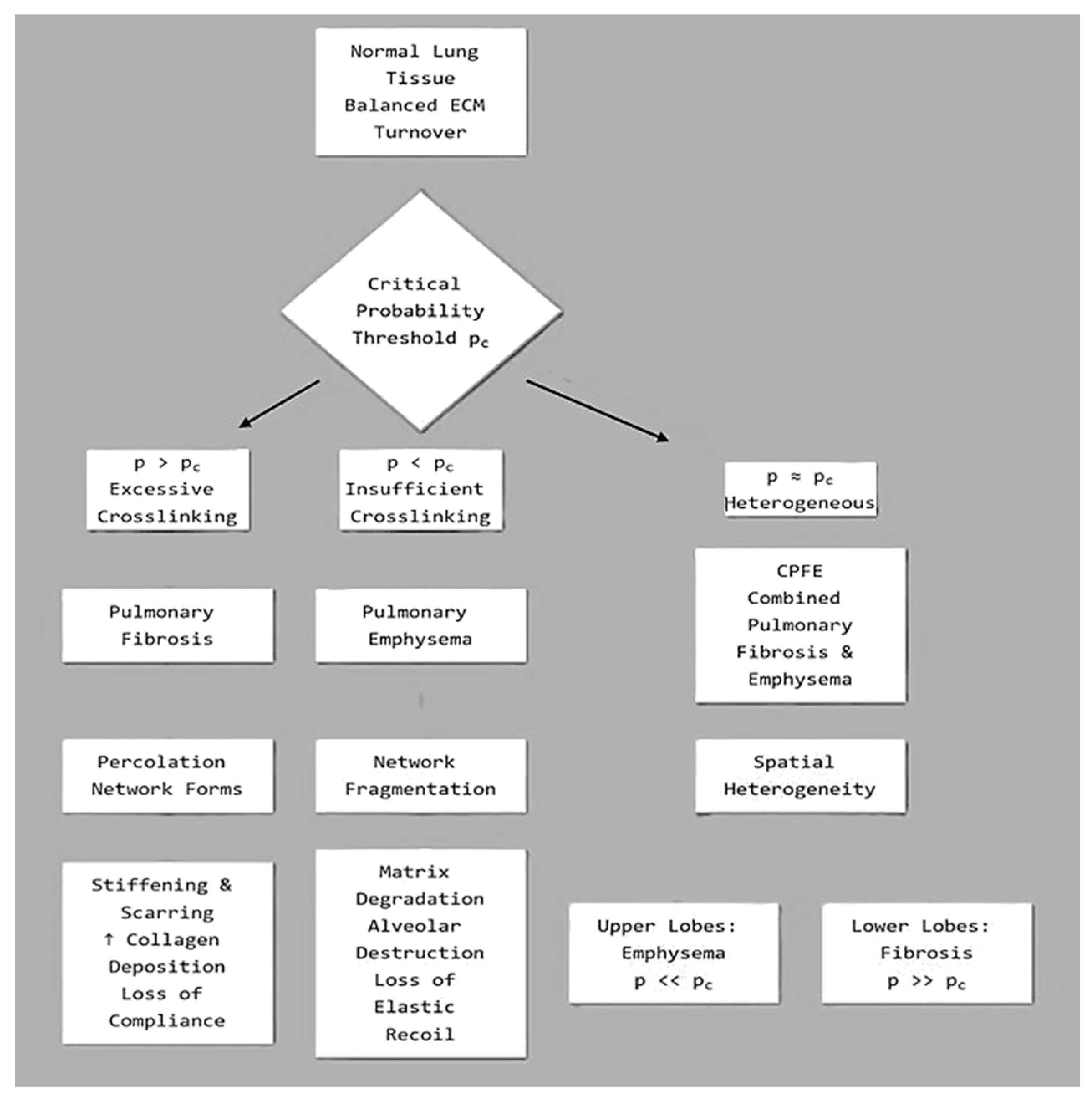

The relationship between crosslinking connectivity and disease state may be expressed as follows:

Let C(t) represent the time-dependent crosslinking connectivity of the ECM. The trajectory of lung injury can be modeled as:

Emphysema, if C(t) < Ccrit

Fibrosis, if C(t) > Ccrit

Mixed/Transitional, if C(t) ≈ Ccrit

Where Ccrit is the percolation threshold for mechanical coherence. This threshold is influenced by:

Crosslinking enzyme activity: lysyl oxidase (LOX)

Matrix composition: collagen vs elastin ratios

Mechanical loading: cyclic stretch, shear stress

Inflammatory milieu: cytokines and oxidative stress

Elastic fiber integrity: fracture susceptibility under hypercrosslinking

Feedback and Bifurcation

Once the system crosses Ccrit, feedback loops reinforce the trajectory:

Below the threshold: Protease activity dominates, further degrading matrix and suppressing crosslinking, thereby driving emphysema.

Above the threshold: Fibroblast proliferation and LOX expression enhances crosslinking and induces fibrosis.

This connectivity-driven bifurcation offers a mechanistic explanation for how similar initial injuries (e.g., smoke exposure, viral insult) can diverge into distinct pathological outcomes based on emergent ECM topology (

Figure 4).

3. Extracellular Matrix Crosslinking: Molecular Mechanisms and Types

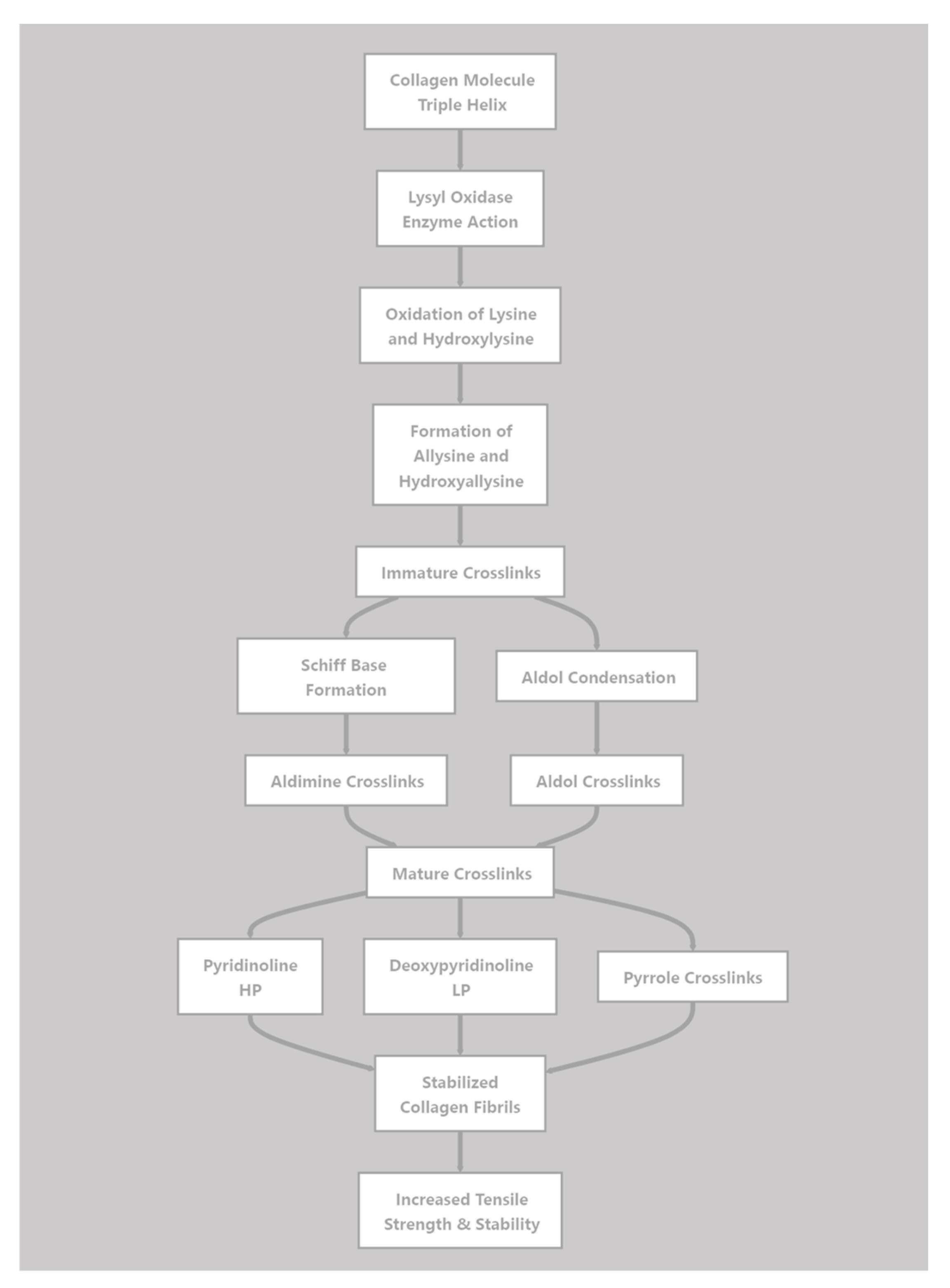

3.1. Enzymatic Crosslinking

The most important physiological crosslinking enzymes are those comprising the LOX family, which includes LOX and four LOX-like proteins (LOXL1-4). These copper-dependent amine oxidases catalyze the oxidative deamination of lysine and hydroxylysine residues in collagen and elastin [

14]. This process generates reactive aldehyde groups, which spontaneously condense with other aldehydes or with unmodified lysine residues to form Schiff bases and aldol condensation products. These initial labile crosslinks subsequently undergo further reactions to form stable, mature crosslinks.

In collagen, LOX-mediated crosslinking produces several types of mature crosslinks. Divalent crosslinks such as dehydrohydroxylysinonorleucine (deH-HLNL) and hydroxylysinonorleucine (HLNL) form from the condensation of one allysine with one hydroxylysine or lysine. These can further mature into trivalent crosslinks, such as hydroxylysyl-pyridinoline (HP) and lysyl-pyridinoline (LP), which link three collagen chains. The nature and density of these crosslinks profoundly affect the mechanical properties and resistance to proteolytic degradation of collagen fibrils (

Figure 5).

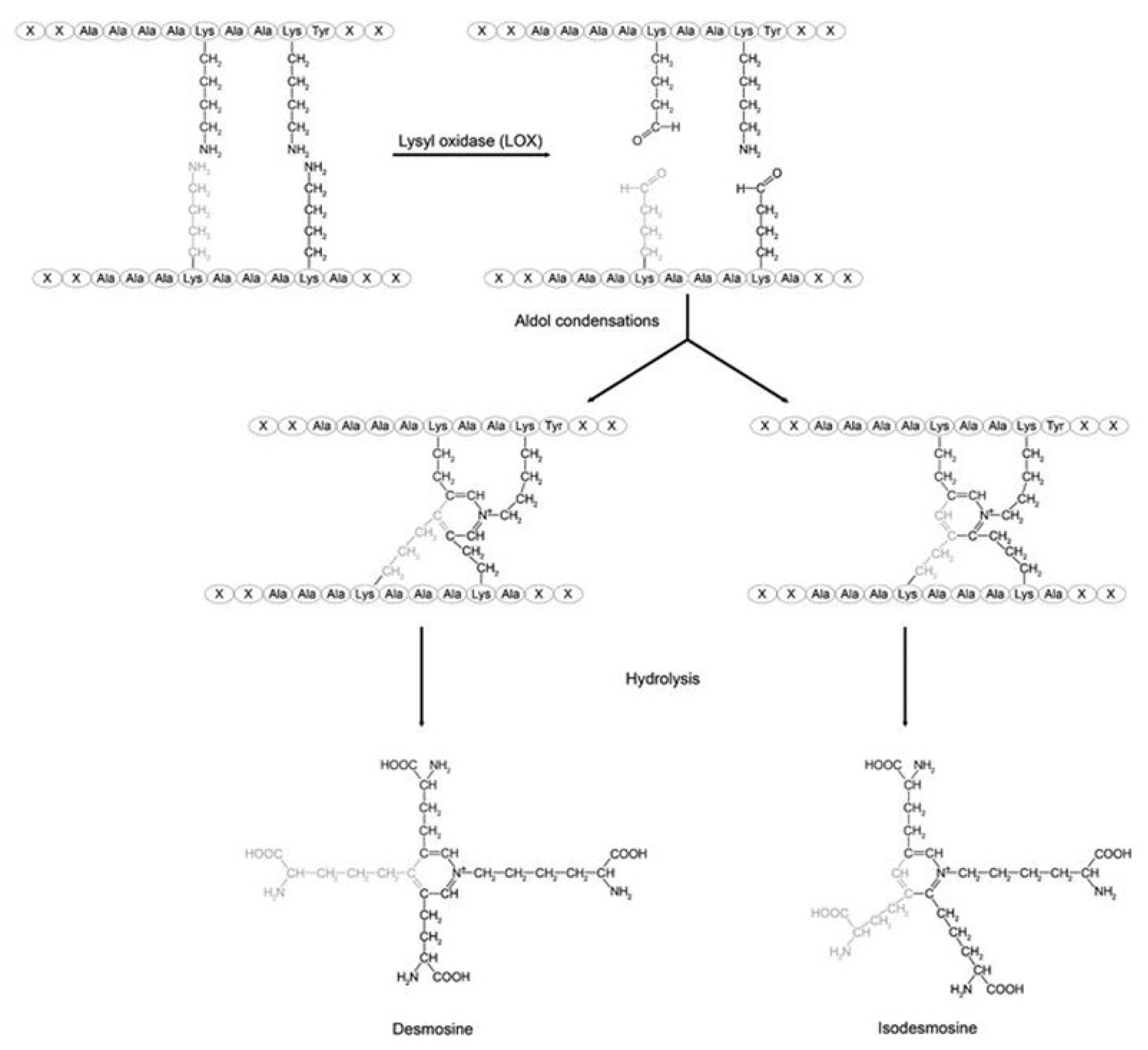

Elastin crosslinking by LOX produces the unique desmosine and isodesmosine crosslinks which link four polypeptide chains (

Figure 5) [

15]. These tetrafunctional crosslinks are essential for elastin's rubber-like mechanical properties, allowing reversible deformation during breathing [

16]. The density and pattern of elastin crosslinking directly determine tissue elastic recoil and compliance (

Figure 6).

Tissue transglutaminases (TG) represent another family of crosslinking enzymes [

17]. These calcium-dependent enzymes catalyze the formation of ε(γ-glutamyl)lysine isopeptide bonds between glutamine and lysine residues. Transglutaminase-2 (TG2), the most studied family member, crosslinks various matrix proteins, including fibronectin, collagen, and other ECM components. During inflammation, TG2 expression increases markedly, and aberrant transglutaminase activity contributes to excessive crosslinking in fibrotic tissue [

18].

3.2. Non-Enzymatic Crosslinking

Non-enzymatic glycation produces advanced glycation end-products (AGEs), which form spontaneous crosslinks between proteins [

19]. The initial Schiff base formed between polysaccharides and amino groups undergoes rearrangement, followed by complex oxidative and non-oxidative reactions, to produce stable AGE crosslinks. Common AGE crosslinks include N-ε-(carboxymethyl)lysine (CML), pentosidine, and glucosepane.

These crosslinks accumulate with age and are accelerated by diabetes, oxidative stress, and inflammation [

20]. Unlike enzymatic crosslinks, AGEs form randomly rather than at specific sites, potentially creating crosslinking patterns that disrupt normal matrix organization [

21]. AGE-modified proteins also interact with receptors for AGEs (RAGE), triggering inflammatory signaling that can amplify tissue damage [

22].

Oxidative crosslinking occurs when reactive oxygen and nitrogen species generate free radicals on matrix proteins, leading to radical-mediated crosslink formation. Tyrosine residues can form dityrosine crosslinks through radical coupling reactions [

23]. Lipid peroxidation products such as malondialdehyde and 4-hydroxynonenal can also form crosslinks between proteins. These oxidative crosslinks are particularly relevant in emphysema, where oxidative stress from cigarette smoke and inflammatory cells is pronounced [

24].

3.3. Crosslink Dynamics and Tissue Mechanics

Higher crosslink density generally increases the elastic modulus and reduces compliance. However, the relationship is complex because the type of crosslink matters. LOX-mediated enzymatic crosslinks occur at specific sites that optimize mechanical function, while non-enzymatic crosslinks form randomly and may create mechanical stress concentrations [

13].

As collagen crosslinking increases, it becomes more resistant to matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and other proteolytic enzymes. This process creates a positive feedback loop in fibrosis: excessive crosslinking makes the matrix resistant to regular turnover, leading to progressive matrix accumulation [

11]. Conversely, in emphysema, the loss of normal crosslinks makes the remaining matrix more susceptible to proteolytic attack, accelerating tissue destruction [

25].

The spatial distribution of crosslinks creates mechanical heterogeneity within tissues. Regions with high crosslink density become mechanical stress concentrators, while regions with low crosslink density become vulnerable failure points [

8]. This heterogeneity is critical for percolation behavior, where the spatial variation in crosslink density determines whether the network has sufficient connectivity to maintain structural integrity or whether vulnerable regions can serve as focal points for catastrophic failure.

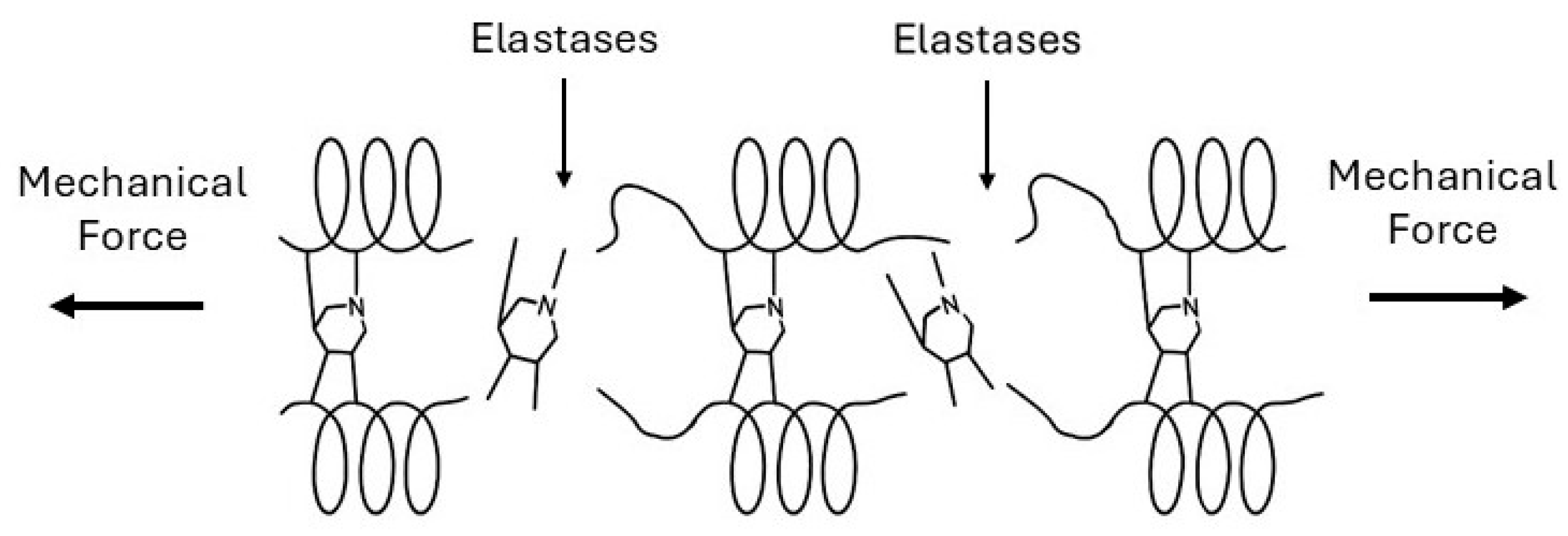

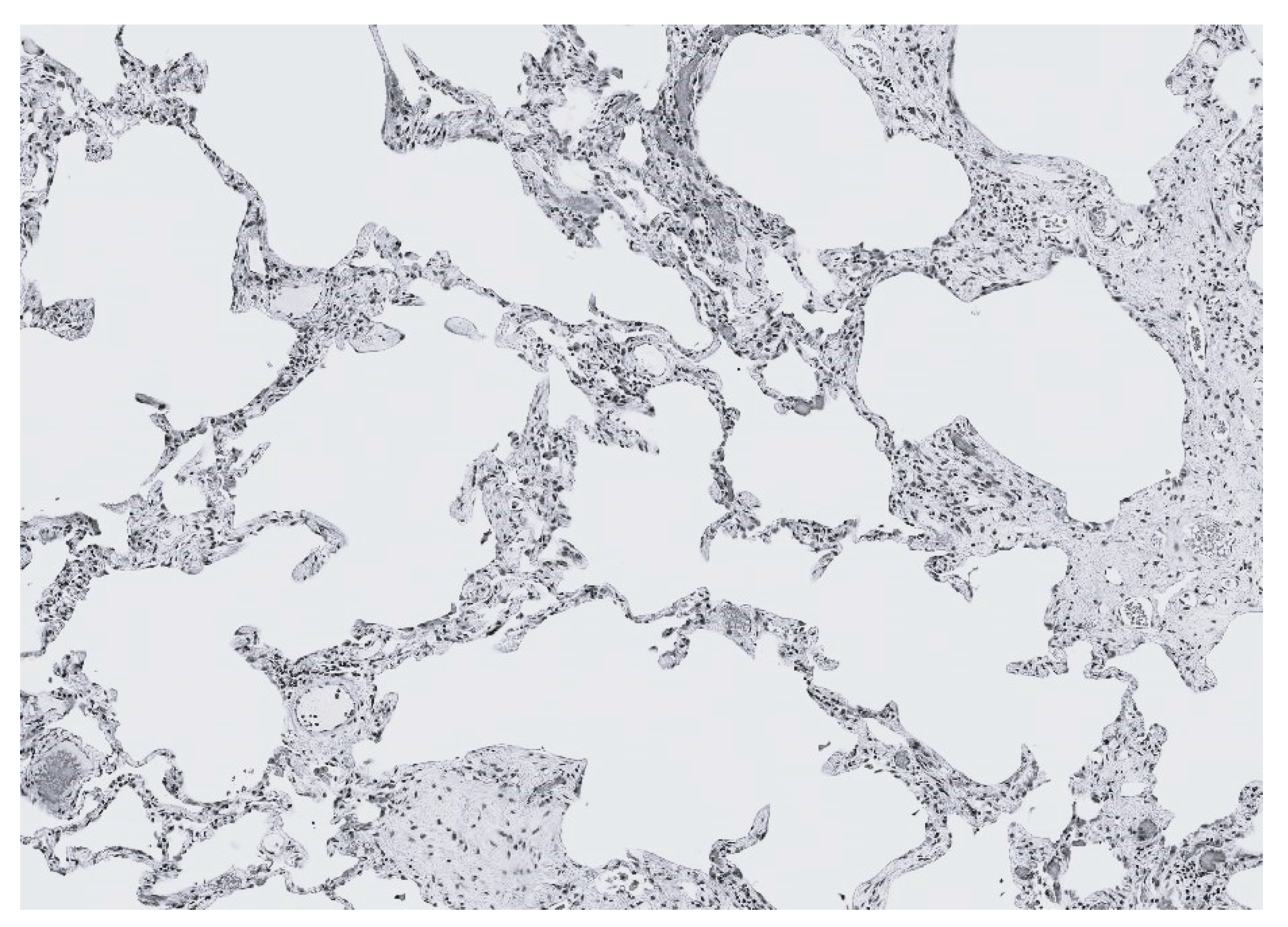

4. Emphysema: Degradative Percolation and Crosslink Loss

Emphysema represents a downward percolation transition involving progressive loss of structural connectivity, leading to collapse of the percolation network. The hallmark of emphysema is the permanent enlargement of airspaces due to the destruction of alveolar walls without obvious fibrosis. While inflammation and protease-antiprotease imbalance are recognized contributors, percolation concepts reveal why this damage propagates catastrophically once initiated.

4.1. Initiation: Local Crosslink Disruption

Emphysema development begins with local damage to the extracellular matrix network. Cigarette smoke, the primary risk factor, delivers both direct oxidative stress and stimulates inflammatory cell recruitment [

26]. Neutrophils and macrophages release elastases, matrix metalloproteinases, and reactive oxygen species that attack matrix proteins and their crosslinks. Oxidative modification of elastin crosslinks disrupts their structure and weakens the elastin network [

27]. When desmosine and isodesmosine undergo breakdown, the mechanical load redistributes to neighboring crosslinks, increasing their stress (

Figure 7).

While collagen fibers are more resistant to proteolytic degradation than elastin, oxidative modification of lysine-derived crosslinks can also reduce their stability. The combination of proteolytic and oxidative damage progressively reduces crosslink density in localized regions.

4.2. Percolation Transition: Loss of Network Connectivity

As the fraction of intact bonds falls below a critical value, no connected pathways span the system, and mechanical load cannot be distributed uniformly throughout the system. In emphysematous lung tissue, this transition manifests as mechanical failure of alveolar walls. Individual alveolar walls, weakened by the loss of crosslinks and matrix degradation, rupture under normal breathing stresses. This process creates larger airspaces and redistributes mechanical stress to adjacent walls. The concentration of stress on remaining intact walls increases their susceptibility to failure, creating a positive feedback loop.

Computational models of alveolar mechanics demonstrate this behavior [

28,

29]. When the decrease in crosslink density reaches a certain threshold (based on network geometry), stress concentrations become so severe that breathing mechanics alone can propagate the rupture. The heterogeneous nature of crosslink loss is a critical feature of this process [

8]. If crosslinks were uniformly reduced throughout the lung, the percolation threshold would require more extensive damage. However, inflammatory damage is spatially heterogeneous: regions exposed to higher smoke concentration, greater inflammatory cell infiltration, or pre-existing structural weakness experience more severe crosslink loss. These vulnerable regions act as nucleation sites where percolation transitions first occur.

4.3. Propagation: Mechanical Amplification

Once local regions have crossed the percolation threshold and mechanical connectivity is lost, mechanical forces amplify the damage. Breathing mechanics create cyclic stresses that preferentially concentrate at the edges of damaged regions. The boundary between intact tissue and emphysematous regions experiences stress concentrations that can be significantly higher than the baseline [

30].

These stress concentrations accelerate crosslink breakage and matrix protein fatigue at the damage boundary. Collagen fibers experience increased mechanical load, and fatigue failure of crosslinks occurs even without additional proteolytic activity. This mechanical propagation explains why emphysema progresses even after smoking cessation [

10].

The loss of elastic recoil in emphysematous regions also affects the global mechanics of the lungs. Normal expiration depends on elastic energy stored during inspiration. As emphysema destroys elastic tissue, the driving force for expiration diminishes, leading to air trapping and hyperinflation. Hyperinflation further increases stress on the remaining alveolar walls, creating a positive feedback loop that drives disease progression.

4.4. Crosslink Repair Failure

In healthy tissue, matrix damage triggers repair responses, including the synthesis of new matrix and crosslink formation. However, in emphysema, these repair mechanisms are insufficient. Several factors contribute to this condition, including oxidative stress that impair LOX activity and the presence of inflammatory mediators that disrupt the balance between matrix synthesis and degradation. Additionally, the mechanical environment in emphysematous regions may not provide appropriate signals for organized matrix deposition [

31].

The failure to restore crosslink density above the percolation threshold allows the degradative process to continue. Unlike acute injuries that heal, emphysema represents a state in which the tissue remains below the critical connectivity threshold, unable to restore its mechanical integrity [

32]. This irreversibility is a hallmark of percolation transitions: once the system has fragmented, restoring connectivity requires extensive reorganization that exceeds the tissue's regenerative capacity.

5. Fibrosis: Rigidity Percolation and Excessive Crosslinking

5.1. Initiation: Aberrant Repair and Crosslinking

Pulmonary fibrosis typically begins with repetitive alveolar epithelial injury and abnormal wound healing [

33]. Factors responsible for this process include occupational exposures, drugs, radiation, and autoimmune conditions. Following injury, type II alveolar epithelial cells undergo apoptosis or senescence, and myofibroblast proliferation and activation occur in the underlying interstitium [

34].

Myofibroblasts are the primary cells involved in lung fibrogenesis, characterized by expression of α-smooth muscle actin and production of excessive extracellular matrix [

35]. These cells synthesize collagen types I and III at rates significantly exceeding those of normal fibroblasts. Activated myofibroblasts also dramatically upregulate LOX and LOXL2 expression, increasing enzymatic crosslinking of newly deposited collagen [

36].

Transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), the primary regulator of fibrosis, drives this process. TGF-β induces myofibroblast differentiation, stimulates collagen synthesis, and upregulates LOX expression [

37]. It also inhibits matrix degradation by reducing MMP expression and increasing tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases [

38]. These mechanisms shift the balance in favor of matrix accumulation and crosslinking.

5.2. Percolation Transition: Rigidity Threshold

As the crosslink density increases, the increasing rigid percolation network significantly alters the mechanical properties of the lung. [

13]. Computational models and experimental measurements show that lung tissue stiffness rapidly increases when crosslink density exceeds a critical threshold [

39,

40]. This process creates mechanical stress on cells, particularly alveolar epithelial cells, which can promote further epithelial injury and apoptosis. Matrix rigidity also activates mechanotransduction pathways in fibroblasts and myofibroblasts, promoting continued collagen production and crosslinking [

41,

42].

The mechanotransduction pathway linking matrix stiffness to continued fibrosis creates a positive feedback loop. Various transcription factors, which accumulate in the nucleus in response to stiff substrate, drive expression of pro-fibrotic genes responsible for synthesis of TGF-β, LOX, and collagen [

37,

43,

44]. Thus, crosslinking-induced stiffness induces a self-propagating process that further drives the tissue further beyond the rigidity percolation threshold.

5.3. Crosslink Types in Fibrosis

The types of crosslinks in fibrotic tissue differ from those in normal lung. LOXL2, which is dramatically upregulated in fibrosis, generates crosslinks that may differ in structure and mechanical properties from LOX-mediated crosslinks [

8,

37]. Studies suggest that LOXL2 preferentially crosslinks newly synthesized collagen before proper fibril formation, potentially creating mechanically abnormal networks [

45].

Transglutaminase-mediated crosslinks also accumulate in fibrotic tissue. TG2 expression increases in response to TGF-β, and TG2 crosslinks various matrix proteins into abnormally stable complexes [

17]. These crosslinks are highly resistant to proteolytic degradation, contributing to the irreversibility of established fibrosis.

AGE crosslinks accumulate in fibrotic tissue, accelerated by inflammation and oxidative stress. These non-enzymatic crosslinks create additional mechanical rigidity and further resistance to degradation [

21]. The random placement of AGE crosslinks may also disrupt normal matrix architecture, creating regions of extreme stiffness interspersed with more compliant areas [

21].

The combination of enzymatic and non-enzymatic crosslinks creates a matrix that is both highly crosslinked and mechanically heterogeneous. This heterogeneity is important for percolation behavior because regions of extreme crosslink density act as rigid nuclei that provide a template for the expansion of fibrotic tissue into adjacent areas [

28].

5.4. Propagation: Mechanical and Biochemical Feedback

Once fibrotic tissue has crossed the rigidity percolation threshold, multiple feedback mechanisms drive progression. Mechanically, the stiff fibrotic tissue concentrates stress on adjacent normal tissue during breathing. These stress concentrations can damage alveolar epithelium, triggering the injury-repair cycle that initiates fibrosis in new regions [

44]. The tissue at the leading edge of this process represent active sites of myofibroblast proliferation and matrix deposition. These foci exhibit extremely high LOX and LOXL2 expression, resulting in locally increased crosslinking [

45]. As these foci deposit and crosslink the matrix, they extend the rigid percolation network into previously normal tissue.

MMPs have significantly reduced activity against heavily crosslinked collagen, and their increased expression may be counteracted by the ability of crosslinks to mask the enzymatic sites they recognize [

13]. This resistance to degradation means fibrosis is essentially irreversible once established. Unlike inflammatory damage that can heal, crossing the rigidity percolation threshold creates a mechanically and biochemically stable pathological state. The tissue has reached a new equilibrium where extensive crosslinking prevents it from returning to the compliant, remodeling-competent state of normal lung tissue.

6. Determinants of Pathway Selection: Why Emphysema or Fibrosis?

6.1. Balance of Proteolysis and Crosslinking

The fundamental determinant is the relative rates of matrix degradation versus crosslinking. When protease activity exceeds the capacity for crosslink formation and repair, crosslink density decreases, moving tissue toward the degradative percolation threshold characteristic of emphysema. When crosslink formation exceeds degradation, particularly in the context of excessive matrix synthesis, tissue moves toward rigidity percolation and fibrosis.

In cigarette smoke-induced disease, the high burden of proteases and oxidative crosslink damage usually tips the balance toward degradation. However, some smokers develop combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema (CPFE), suggesting that in certain individuals or lung regions, both processes are not mutually exclusive and may instead be opposite ends of a spectrum determined by local protease-crosslink balance (

Figure 8) [

46,

47].

6.2. Matrix Composition and Pre-Existing Crosslink Density

The baseline state of the extracellular matrix may influence susceptibility to either type of transition. Tissue with lower crosslink density is closer to the degradative percolation threshold and may more readily develop emphysema. Genetic variations in LOX or collagen genes that affect baseline crosslink density may predispose toward one pathway or the other. The dominance of either percolation process may also be dependent on age-related changes in matrix composition and crosslinking. Older individuals have accumulated more crosslinks, which might provide some protection against degradative percolation but could also promote fibrosis by creating an initially stiff mechanical environment [

48].

6.3. Cell Populations and Inflammatory Milieu

The specific inflammatory cell populations and cytokine profiles differ between emphysema and fibrosis. Emphysema is characterized by neutrophil and M1 macrophage predominance whereas interstitial fibrosis involves M2 macrophage polarization, TGF-β dominance, and myofibroblast activation [

37,

38,

49,

50]. These distinct inflammatory environments create different perturbations to the balance between crosslinking and degradation. Understanding how the immune response is polarized in individual patients might help predict trajectory and guide intervention.

7. Therapeutic Implications: Targeting Crosslinking and Percolation

7.1. Emphysema: Preventing Degradative Percolation

In emphysema, therapeutic goals include preventing crosslink loss, blocking catastrophic percolation transitions, and potentially restoring connectivity above the critical threshold. Although several different approaches have been proposed, none have been adequately tested in either preclinical or human studies.

Antioxidant strategies are designed to prevent injury by free radicals in cigarette smoke and other air pollutants. While clinical trials of simple antioxidants have been disappointing, more targeted approaches that specifically protect crosslink structures might be more effective [

51]. Compounds that stabilize elastin crosslinks or prevent desmosine oxidation could maintain the elastic network above the percolation threshold. Furthermore, LOX upregulation in remaining intact tissue might enhance repair responses. Strategies to increase enzymatic crosslink formation in regions near emphysematous damage could stabilize the boundary and prevent propagation. However, this approach must be carefully controlled to prevent excessive crosslinking, which could lead to fibrosis.

MMP inhibitors have been explored but with limited success, partly because these enzymes have important homeostatic functions [

52,

53]. Targeted inhibition specifically at the boundaries of emphysematous regions, where mechanical stress concentrations accelerate damage, might be more effective than systemic inhibition. Localization of the process may be facilitated by attaching specific matrix binding agents to the inhibitors.

Regenerative approaches utilizing stem cells or progenitor cells aim to repair and rebuild damaged tissue [

54,

55]. From a percolation perspective, these approaches should not only replace cells but also restore matrix connectivity. Scaffolds that provide appropriate crosslink density and mechanical properties may be necessary to guide tissue regeneration above the percolation threshold.

7.2. Fibrosis: Preventing Rigidity Percolation

LOX inhibitors, particularly those targeting LOXL2, have shown promise in preclinical models and early clinical trials [

56,

57]. Simtuzumab, a monoclonal antibody targeting LOXL2, has been shown to reduce fibrosis in animal models, but a clinical trial in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis was disappointing [

58]. This result may reflect limitations in antibody penetration into established fibrotic tissue or treatment initiation too late in the disease course. Next-generation LOX inhibitors with better tissue penetration or administered earlier might be more effective.

Transglutaminase inhibitors represent another crosslinking intervention. Small-molecule TG2 inhibitors have demonstrated efficacy in preventing the development of fibrosis in animal models [

59]. However, transglutaminases have important physiological functions, requiring novel drug delivery strategies that may involve the coupling of these inhibitors to extracellular matrix attachment molecules [

60].

Another approach involves the use of compounds that cleave established crosslinks. AGE crosslink breakers have been developed for diabetes complications, and adapting these for pulmonary fibrosis could reduce matrix stiffness in established disease [

61]. This strategy could be combined with anti-TGF-β therapies that reduce LOX expression and myofibroblast activation. Pirfenidone, one of the approved treatments for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, may work in part by downregulating TGF-β signaling and LOX expression [

62].

At higher levels of scale, the use of agents that target the effects of mechanical stress could slow the progression of interstitial fibrosis. In particular the use of YAP/TAZ inhibitors to limit cell proliferation and matrix deposition resulting from mechanotransduction feedback loops could mitigate percolation forces associated with fibrogenesis [

63]. In emphysema, strategies to reduce stress concentrations utilizing mechanical devices might slow progression even without directly addressing matrix damage [

64].

Understanding that emphysema and fibrosis represent opposite percolation transitions suggests that therapeutic strategies should be individualized based on assessment of which transition threatens individual patients. Biomarkers of crosslink turnover, such as urinary desmosine in emphysema or serum markers of LOX activity in fibrosis, might guide therapy selection (

Figure 9) [

65,

66]. Furthermore, imaging techniques that assess tissue mechanical properties, such as magnetic resonance elastography, could identify regions approaching critical percolation thresholds before irreversible changes occur [

67]. Early intervention targeted to these vulnerable regions might prevent catastrophic transitions.

7.3. Therapeutic Limitations

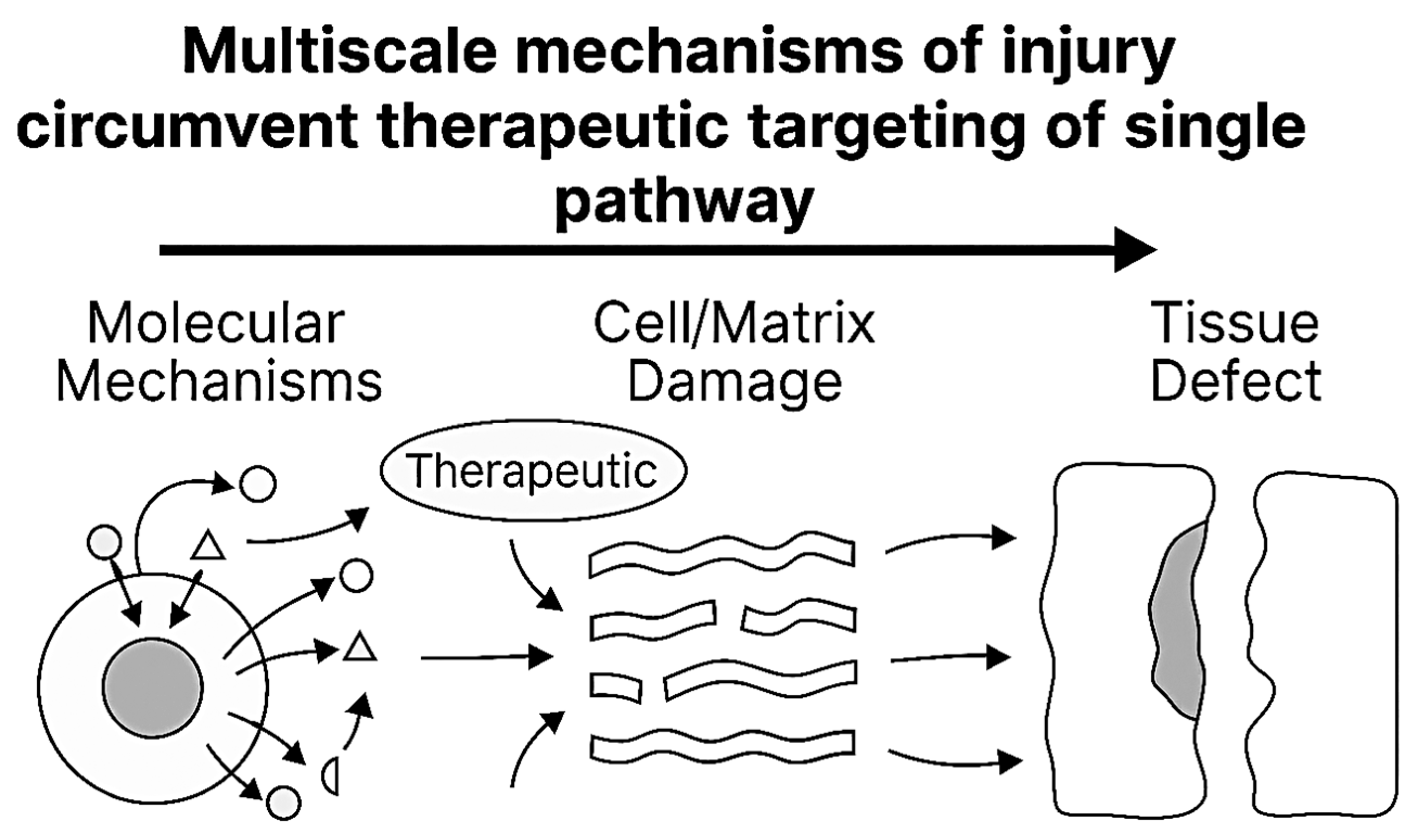

The multiscale emergent properties of pulmonary emphysema and interstitial fibrosis have profound implications for developing effective therapies for these diseases [

68,

69]. First, they suggest that single-target molecular therapies, while conceptually elegant and successful in simpler diseases, may be fundamentally insufficient for complex chronic lung diseases. Combination approaches that simultaneously target multiple scales, including molecular pathways, cellular behaviors, tissue mechanics, and systemic factors, may be necessary to achieve meaningful clinical benefit (

Table 1) [

70,

71].

Therapies might be most effective in disease when the pathological state is less entrenched and reversibility remains possible, but this requires improved early diagnosis and risk stratification. Alternatively, more aggressive interventions capable of disrupting established attractor states might be needed in advanced disease, but such approaches must be carefully designed to avoid catastrophic destabilization of remaining lung function.

These considerations highlight the importance of combination therapies that address disease at multiple scales simultaneously. For fibrosis, this might mean combining anti-crosslinking therapy with interventions targeting inflammation, epithelial dysfunction, mechanical stress, and systemic complications. For emphysema, combination of protease inhibition, anti-inflammatory therapy, and strategies to promote appropriate matrix repair might prove necessary (

Figure 10).

Despite molecular blockade by a targeted therapeutic agent, injury propagates through alternative signaling routes and escalates across biological scales. Arrows illustrate bypass routes and upward propagation, emphasizing that single-pathway interventions may be insufficient to halt multiscale injury progression.

Personalized or adaptive treatment strategies that account for inter-patient heterogeneity and temporal dynamics may be required. Rather than fixed regimens, dynamic treatment protocols that intensify or modify therapy based on biomarkers reflecting disease activity at multiple scales might prove more effective [

72]. The limited success of current therapeutic interventions for emphysema and interstitial fibrosis indicates the need for a better understanding of the complex mechanisms that determine the molecular, cellular, and structural features of these diseases.

8. Conclusions

The percolation framework provides a unifying perspective on the divergent pathological outcomes of chronic lung inflammation. Emphysema and interstitial fibrosis, rather than being entirely distinct diseases, represent opposite transitions through critical percolation thresholds: one involving the loss of structural connectivity through crosslink degradation, and the other involving excessive connectivity through pathological cross-linking.

Crosslinking emerges as the central molecular mechanism governing these transitions. The balance between crosslink formation and degradation determines whether tissue maintains homeostatic connectivity, fragments into emphysematous destruction, or rigidifies into fibrotic consolidation. The types of crosslinks, enzymatic versus non-enzymatic and properly positioned versus random, further influence mechanical properties and susceptibility to percolation transitions.

Understanding these transitions as percolation phenomena explains several puzzling clinical observations, including the non-linear progression of disease, the heterogeneous spatial distribution of pathology within the lungs, and the coexistence of emphysema and fibrosis in some patients. This framework also highlights why current therapies have had limited success. Interventions that do not address the fundamental percolation dynamics cannot reverse disease once critical thresholds have been crossed. Future therapeutic strategies must target the crosslinking mechanisms and mechanical feedback loops that determine percolation transitions.

The percolation perspective ultimately reframes our understanding of chronic lung disease from a purely biochemical problem to one involving critical transitions in physical network properties. Crosslinking serves as the molecular mechanism controlling these transitions, making it both a marker of disease state and a therapeutic target. By recognizing that emphysema and fibrosis represent opposite sides of percolation thresholds, we can develop more rational, mechanism-based approaches to preventing and treating these devastating diseases. The challenge ahead is to translate these insights into clinical tools that can detect approaching transitions and interventions that can stabilize lung tissue within the homeostatic range between degradative and rigidity percolation thresholds.

References

- Medzhitov, R. The spectrum of inflammatory responses. Science 2021, 374, 1070–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusev, E.; Zhuravleva, Y. Inflammation: A new look at an old problem. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 4596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margraf, A.; Perretti, M. Immune cell plasticity in inflammation: Insights into description and regulation of immune cell phenotypes. Cells 2022, 11, 1824. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4409/11/11/1824. [CrossRef]

- D’Souza, R.M.; Nagler, J. Anomalous critical and supercritical phenomena in explosive percolation. Nature Physics 2015, 11, 531–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, T.; He, C.; Venado, A.; Zhou, Y. Extracellular matrix stiffness in lung health and disease. Comprehensive Physiology 2022, 12, 3523–3558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niewoehner, D.E.; Hoidal, J.R. Lung fibrosis and emphysema: Divergent responses to a common injury? Science 1982, 217, 359–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahimi, M. Percolation in Biological Systems. In Applications of Percolation Theory; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-031-20386-2_18.

- Mak, M. Impact of crosslink heterogeneity on extracellular matrix mechanics and remodeling. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2020, 18, 3969–3976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vila Ellis, L.; Chen, J. A cell-centric view of lung alveologenesis. Developmental Dynamics 2021, 250, 482–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, J.K.; Harmsen, M.C. Chronic lung diseases: Entangled in extracellular matrix. European Respiratory Review 2022, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, S.M.; He, Y. Exploring Extracellular Matrix Crosslinking as a Therapeutic Approach to Fibrosis. Cells 2024, 13, 438. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4409/13/5/438. [CrossRef]

- Levy, A.; Goldstein, H.; Brenman, D.; Diesendruck, C.E. Effect of intramolecular crosslinker properties on the mechanochemical fragmentation of covalently folded polymers. Journal of Polymer Science 2020, 58, 692–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, W.; Lyu, C.; Liao, H.; Du, Y. Collagen crosslinking: Effect on structure, mechanics and fibrosis progression. Biomedical Materials 2021, 16, 062005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaffryar-Eilot, S.; Hasson, P. Lysyl oxidases: Orchestrators of cellular behavior and ECM remodeling and homeostasis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 11378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmelzer, C.E.; Hedtke, T.; Heinz, A. Unique molecular networks: Formation and role of elastin cross-links. Iubmb Life 2020, 72, 842–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trębacz, H.; Barzycka, A. Mechanical properties and functions of elastin: An overview. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani, F.; Kaartinen, M.T. Transglutaminases in fibrosis—Overview and recent advances. American Journal of Physiology-Cell Physiology 2023, 325, C1601–C1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitomi, K. Role of Transglutaminase 2 in Cell Death, Survival, and Fibrosis. Cells 2021, 10, 1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaar, J.; Naffa, R.; Brimble, M. Enzymatic and non-enzymatic crosslinks found in collagen and elastin and their chemical synthesis. Organic Chemistry Frontiers 2020, 7, 2789–2814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passarelli, M.; Machado, U.F. AGEs-induced and endoplasmic reticulum stress/inflammation-mediated regulation of GLUT4 expression and atherogenesis in diabetes mellitus. Cells 2021, 11, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamml, J.; Ke, C.Y.; Acevedo, C.; Kammer, D.S. The influence of AGEs and enzymatic cross-links on the mechanical properties of collagen fibrils. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2023, 143, 105870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, K.; Vetter, S.W.; Alam, Y.; Hasan, M.Z.; Nath, A.D.; Leclerc, E. Role of the receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) and its ligands in inflammatory responses. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gatin, A.; Billault, I.; Duchambon, P.; Van der Rest, G.; Tabet, J.C. Oxidative radicals (HO• or N3•) induce several di-tyrosine bridge isomers at the protein scale. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 2021, 162, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Liu, H.; Song, L. Novel drug delivery systems targeting oxidative stress in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A review. Journal of nanobiotechnology 2020, 18, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagiola, M.; Reznik, S.; Riaz, M.; Qyang, Y.; Lee, S.; Avella, J.; Turino, G.; Cantor, J. The relationship between elastin cross linking and alveolar wall rupture in human pulmonary emphysema. Am. J. Physiol.-Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2023, 324, L747–L755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obernolte, H.; Niehof, M.; Braubach, P.; Fieguth, H.G.; Jonigk, D.; Pfennig, O.; Tschernig, T.; Warnecke, G.; Braun, A.; Sewald, K. Cigarette smoke alters inflammatory genes and the extracellular matrix—Investigations on viable sections of peripheral human lungs. Cell and tissue research 2022, 387, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umeda, H.; Nakamura, F.; Suyama, K. Oxodesmosine and isooxodesmosine, candidates of oxidative metabolic intermediates of pyridinium cross-links in elastin. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2001, 385, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casey, D.T.; Bou Jawde, S.; Herrmann, J.; Mori, V.; Mahoney, J.M.; Suki, B.; Bates, J.H. Percolation of collagen stress in a random network model of the alveolar wall. Scientific reports 2021, 11, 16654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depalle, B.; Qin, Z.; Shefelbine, S.J.; Buehler, M.J. Influence of cross-link structure, density and mechanical properties in the mesoscale deformation mechanisms of collagen fibrils. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2015, 52, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, T.M.; Quiros, K.A.M.; Dominguez, E.C.; Ulu, A.; Nordgren, T.M.; Nair, M.G.; Eskandari, M. Healthy and diseased tensile mechanics of mouse lung parenchyma. Results in Engineering 2024, 22, 102169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgstaller, G.; Oehrle, B.; Gerckens, M.; White, E.S.; Schiller, H.B.; Eickelberg, O. The instructive extracellular matrix of the lung: Basic composition and alterations in chronic lung disease. European Respiratory Journal 2017, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, S.P.; Bodduluri, S.; Reinhardt, J.M.; Nakhmani, A.; COPDGene Investigators. Mechanically Affected Lung and Progression of Emphysema. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2025, 211, 1409–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chambers, R.C.; Mercer, P.F. Mechanisms of alveolar epithelial injury, repair, and fibrosis. Annals of the American Thoracic Society 2015, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tu, M.; Wei, T.; Jia, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wu, J. Molecular mechanisms of alveolar epithelial cell senescence and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: A narrative review. Journal of Thoracic Disease 2022, 15, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.; Dey, T.; Liu, G. Recent developments in the pathobiology of lung myofibroblasts. Expert review of respiratory medicine 2021, 15, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuo, A.; Yanagi, S.; Tsubouchi, H.; Miura, A.; Shigekusa, T.; Matsumoto, N.; Nakazato, M. Significance of nuclear upregulation of LOXL2 in fibroblasts and myofibroblasts in the fibrotic process of acute respiratory distress syndrome. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andugulapati, S.B.; Gourishetti, K.; Tirunavalli, S.K.; Nayak, P.G. Biochanin-A ameliorates pulmonary fibrosis by suppressing the TGF-β mediated EMT, myofibroblasts differentiation and collagen deposition in in vitro and in vivo models. Phytomedicine 2020, 77, 153270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inui, N.; Sakai, S.; Kitagawa, M. Molecular pathogenesis of pulmonary fibrosis, with focus on pathways related to TGF-β and the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. International journal of molecular sciences 2021, 22, 6107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nizamoglu, M.; de Hilster, R.H.; Zhao, F.; Sharma, P.K.; Borghuis, T.; Harmsen, M.C.; Burgess, J.K. An in vitro model of fibrosis using crosslinked native extracellular matrix-derived hydrogels to modulate biomechanics without changing composition. Acta biomaterialia 2022, 147, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suki, B.; Bates, J.H. Pulmonary Fibrosis. In Mathematical Modeling of the Healthy and Diseased Lung: Linking Structure, Biomechanics, and Mechanobiology; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 193–224. [Google Scholar]

- Tiskratok, W.; Chuinsiri, N.; Limraksasin, P.; Kyawsoewin, M.; Jitprasertwong, P. Extracellular Matrix Stiffness: Mechanotransduction and Mechanobiological Response-Driven Strategies for Biomedical Applications Targeting Fibroblast Inflammation. Polymers 2025, 17, 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Yu, H.; Zhao, H.; Wu, Z.; Long, Y.; Zhang, J.; Du, Y. Matrix-transmitted paratensile signaling enables myofibroblast–fibroblast cross talk in fibrosis expansion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 10832–10838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, L. Single-cell transcriptome analysis revealing mechanotransduction via the Hippo/YAP pathway in promoting fibroblast-to-myofibroblast transition and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis development. Gene 2025, 943, 149271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Plotnikov, S.V. Mechanosensitive regulation of fibrosis. Cells 2021, 10, 994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aumiller, V.; Strobel, B.; Romeike, M.; Schuler, M.; Stierstorfer, B.E.; Kreuz, S. Comparative analysis of lysyl oxidase (like) family members in pulmonary fibrosis. Scientific reports 2017, 7, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Jiang, S. Combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema (CPFE): An entity different from emphysema or pulmonary fibrosis alone. J Thorac Dis. 2015, 7, 767–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cottin, V.; Nunes, H.; Brillet, P.; Delaval, P.; Devouassoux, G.; Tillie-Leblond, I.; Cordier, J.F. Combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema: A distinct underrecognised entity. European Respiratory Journal 2005, 26, 586–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sicard, D.; Haak, A.J.; Choi, K.M.; Craig, A.R.; Fredenburgh, L.E.; Tschumperlin, D.J. Aging and anatomical variations in lung tissue stiffness. Am. J. Physiol.-Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2018, 314, L946–L955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mu, Q.; Wang, Q.; Yang, Y.; Wei, G.; Wang, H.; Li, Y. HMGB1 promotes M1 polarization of macrophages and induces COPD inflammation. Cell Biology International 2025, 49, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishore, A.; Petrek, M. Roles of macrophage polarization and macrophage-derived miRNAs in pulmonary fibrosis. Frontiers in immunology 2021, 12, 678457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Astori, E.; Garavaglia, M.L.; Colombo, G.; Landoni, L.; Portinaro, N.M.; Milzani, A.; Dalle-Donne, I. Antioxidants in smokers. Nutrition Research Reviews 2022, 35, 70–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopoulou, M.E.; Papakonstantinou, E.; Stolz, D. Matrix metalloproteinases in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabral-Pacheco, G.A.; Garza-Veloz, I.; Castruita-De la Rosa, C.; Ramirez-Acuña, J.M.; Perez-Romero, B.A.; Guerrero-Rodriguez, J.F.; Martinez-Avila, N.; Martinez-Fierro, M.L. The roles of matrix metalloproteinases and their inhibitors in human diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khedoe, P.P.P.; Wu, X.; Gosens, R.; Hiemstra, P.S. Repairing damaged lungs using regenerative therapy. Current Opinion in Pharmacology 2021, 59, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Feng, M.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, B.; Zhao, Y.; Dai, J. Biomimetic scaffold-based stem cell transplantation promotes lung regeneration. Bioengineering & Translational Medicine 2023, 8, e10535. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Li, S.; Li, W. LOX/LOXL in pulmonary fibrosis: Potential therapeutic targets. Journal of drug targeting 2019, 27, 790–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Findlay, A.; Turner, C.; Schilter, H.; Deodhar, M.; Zhou, W.; Perryman, L.; Foot, J.; Zahoor, A.; Yao, Y.; Hamilton, R.; et al. An activity-based bioprobe differentiates a novel small molecule inhibitor from a LOXL2 antibody and provides renewed promise for anti-fibrotic therapeutic strategies. Clin Transl Med 2021, 11, e572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Raghu, G.; Brown, K.K.; Collard, H.R.; Cottin, V.; Gibson, K.F.; Kaner, R.J.; Lederer, D.J.; Martinez, F.J.; Noble, P.W.; Song, J.W.; et al. Efficacy of simtuzumab versus placebo in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: A randomised, double-blind, controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Respir Med 2017, 5, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fell, S.; Wang, Z.; Blanchard, A.; Nanthakumar, C.; Griffin, M. Transglutaminase 2: A novel therapeutic target for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis using selective small molecule inhibitors. Amino Acids 2021, 53, 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, C. Targeting the extracellular matrix for delivery of bioactive molecules to sites of arthritis. British journal of pharmacology 2019, 176, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sourris, K.C.; Watson, A.; Jandeleit-Dahm, K. Inhibitors of advanced glycation end product (AGE) formation and accumulation. In Reactive Oxygen Species: Network Pharmacology and Therapeutic Applications; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2020; pp. 395–423. [Google Scholar]

- Ruwanpura, S.M.; Thomas, B.J.; Bardin, P.G. Pirfenidone: Molecular mechanisms and potential clinical applications in lung disease. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2020, 62, 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papavassiliou, K.A.; Sofianidi, A.A.; Spiliopoulos, F.G.; Gogou, V.A.; Gargalionis, A.N.; Papavassiliou, A.G. YAP/TAZ signaling in the pathobiology of pulmonary fibrosis. Cells 2024, 13, 1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leslie, M.N.; Chou, J.; Young, P.M.; Traini, D.; Bradbury, P.; Ong, H.X. How do mechanics guide fibroblast activity? complex disruptions during emphysema shape cellular responses and limit research. Bioengineering 2021, 8, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantor, J. Desmosine: The Rationale for Its Use as a Biomarker of Therapeutic Efficacy in the Treatment of Pulmonary Emphysema. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stankovic, S.; Stjepanovic, M.; Asanin, M. Biomarkers in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. In Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sack, I. Magnetic resonance elastography from fundamental soft-tissue mechanics to diagnostic imaging. Nature Reviews Physics 2023, 5, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suki, B.; Majumdar, A.; Nugent, M.A.; Bates, J.H.T. In silico modeling of interstitial lung mechanics: Implications for disease development and repair. Drug Discov. Today Dis. Mech. 2007, 4, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neelakantan, S.; Xin, Y.; Gaver, D.P.; Cereda, M.; Rizi, R.; Smith, B.J.; Avazmohammadi, R. Computational lung modelling in respiratory medicine. Journal of The Royal Society Interface 2022, 19, 20220062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentaher, A.; Glehen, O.; Degobert, G. Pulmonary Emphysema: Current Understanding of Disease Pathogenesis and Therapeutic Approaches. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doroudian, M.; O’Neill, A.; Mac Loughlin, R.; Prina-Mello, A.; Volkov, Y.; Donnelly, S.C. Nanotechnology in pulmonary medicine. Current opinion in pharmacology 2021, 56, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, X.P.; Qin, B.D.; Jiao, X.D.; Liu, K.; Wang, Z.; Zang, Y.S. New clinical trial design in precision medicine: Discovery, development and direction. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2024, 9, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).