Submitted:

15 June 2024

Posted:

17 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

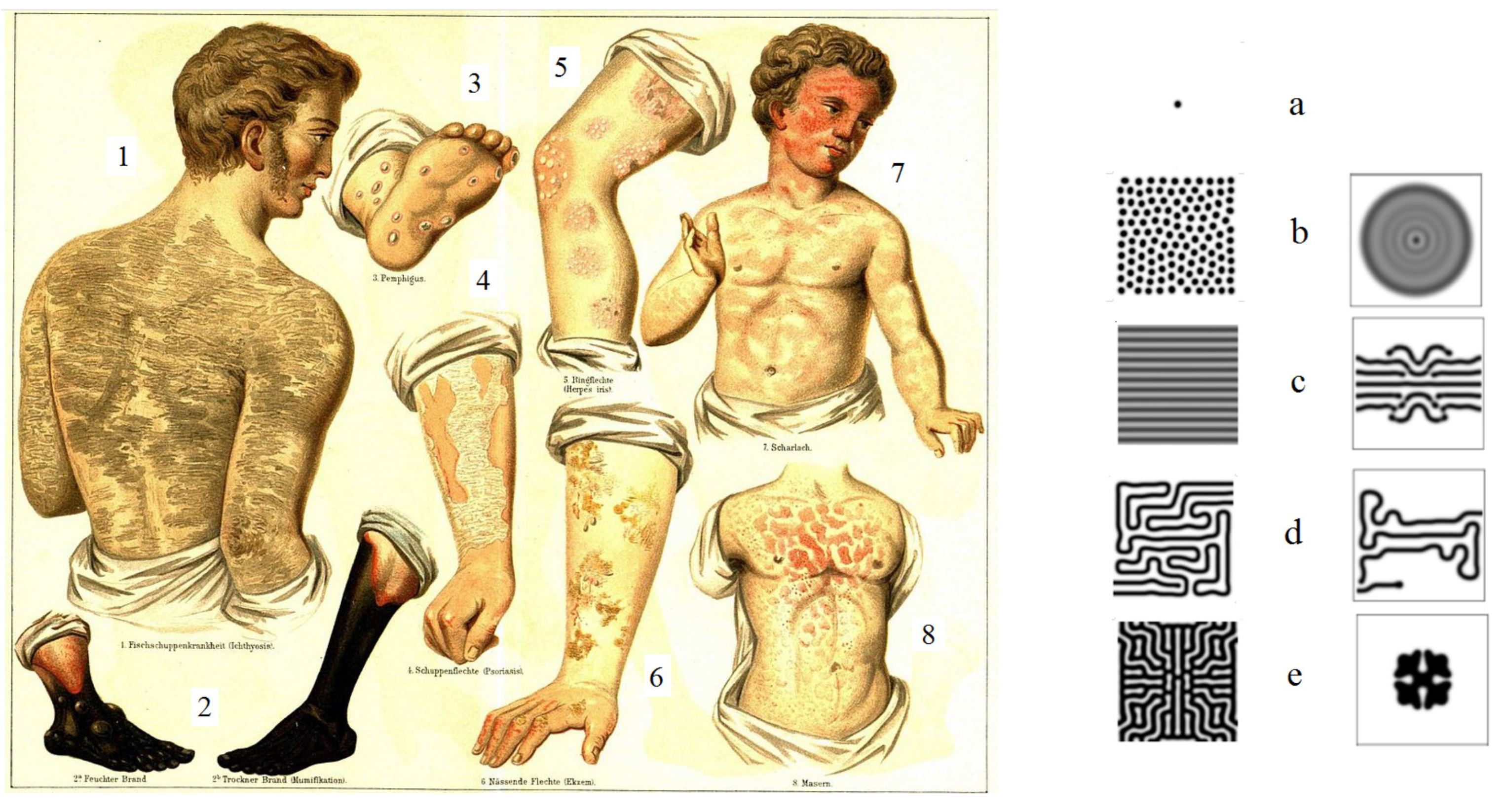

1.1. Biological Background

1.2. Modelling of Inflammation

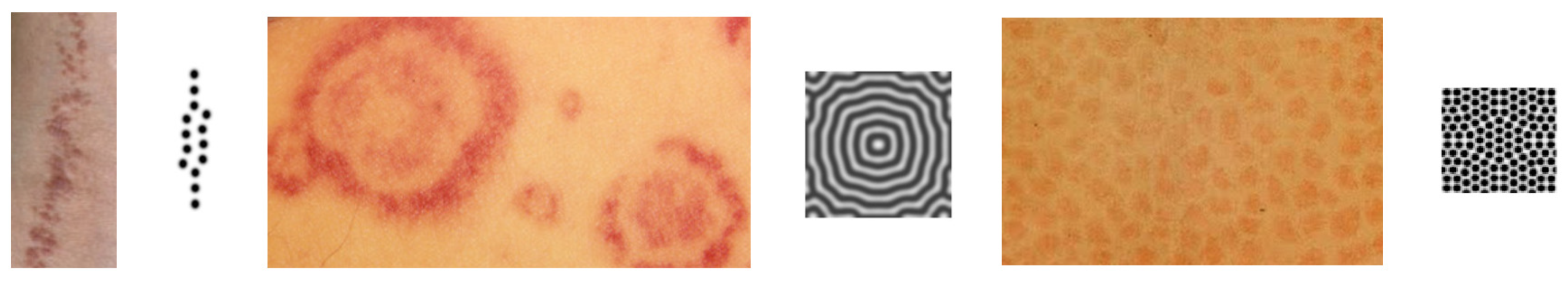

1.3. Pattern Formation

2. Model of Immune Response and Inflammation

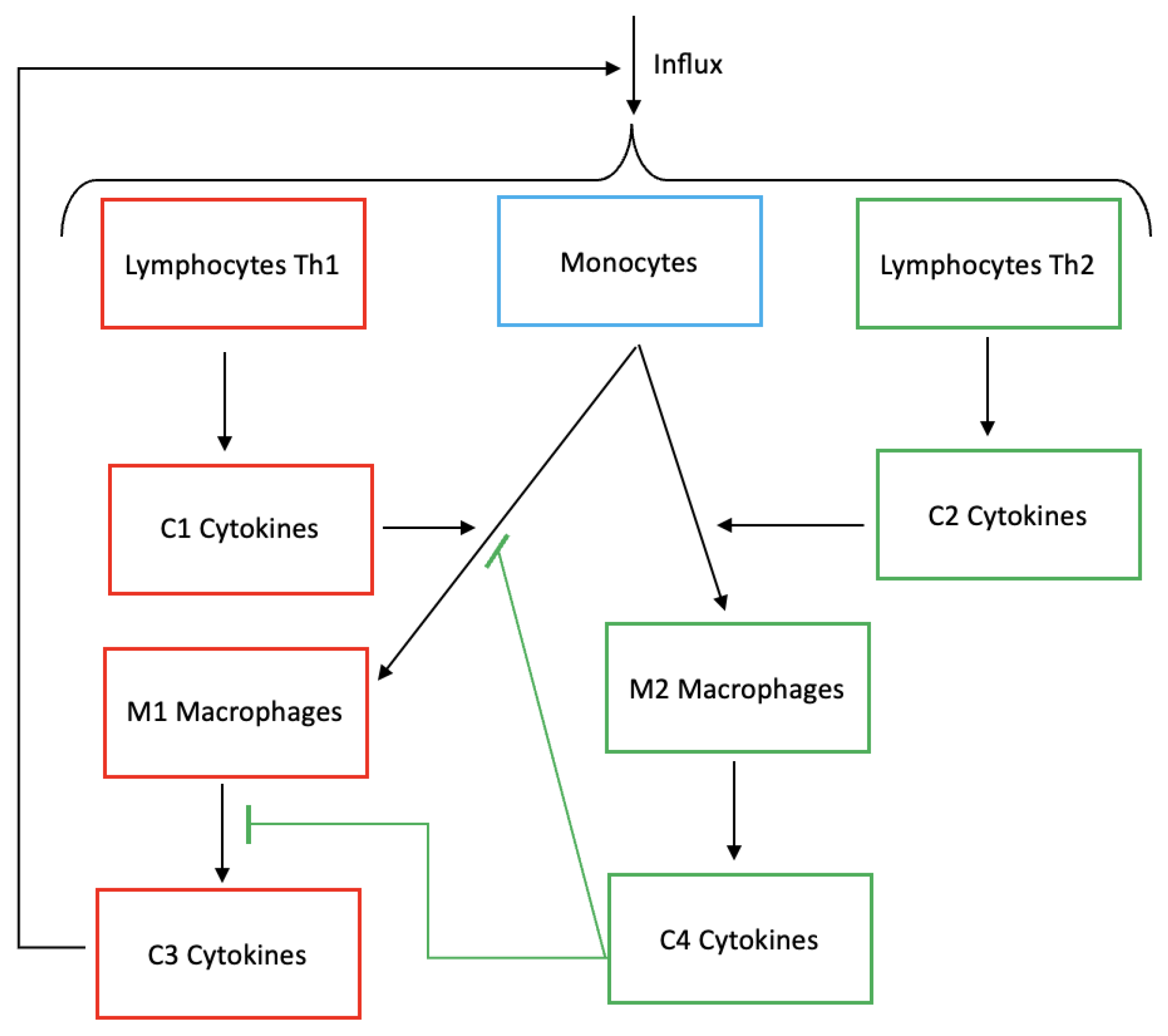

2.1. Generic Model of Inflammation

2.2. Reduced inflammation model

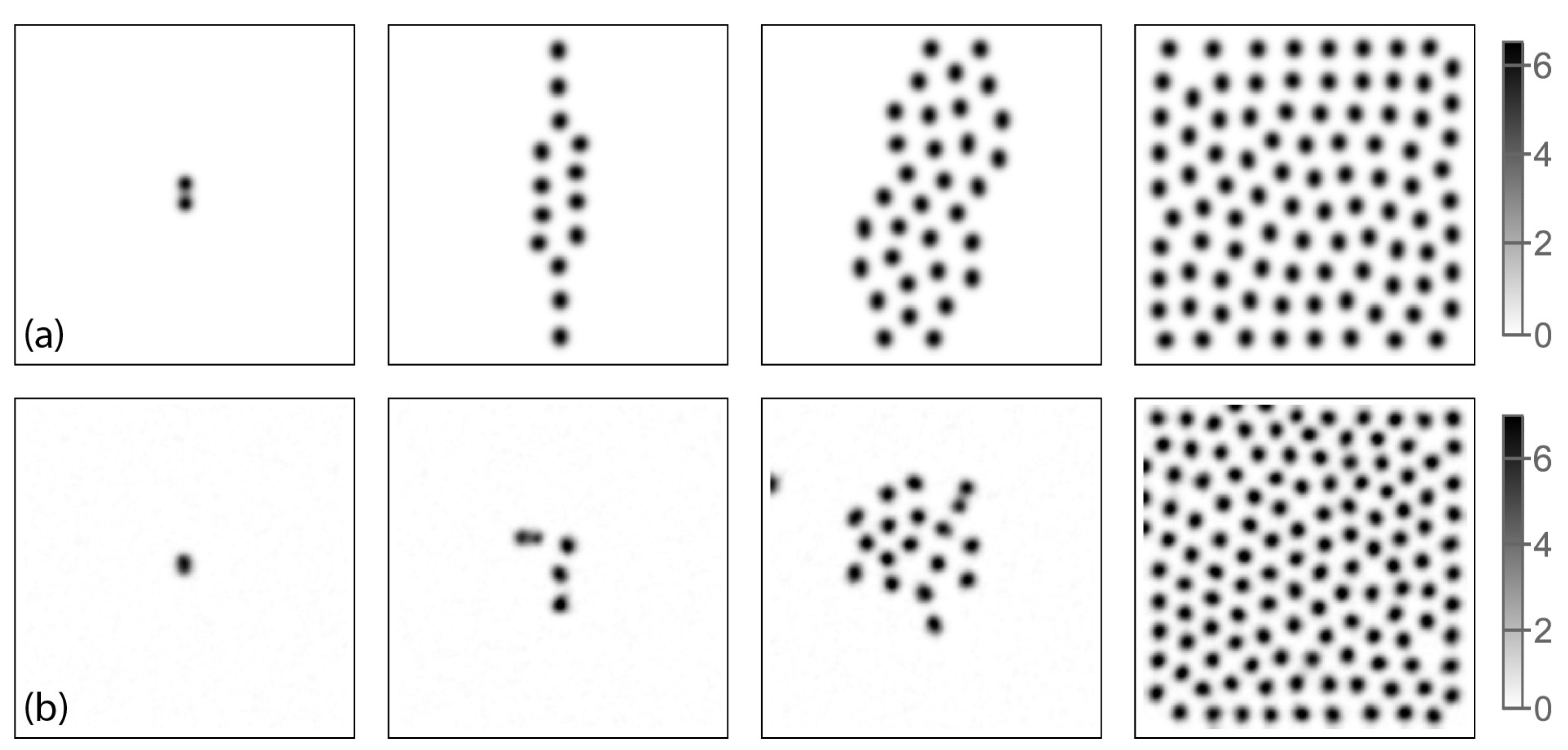

3. Pattern Formation

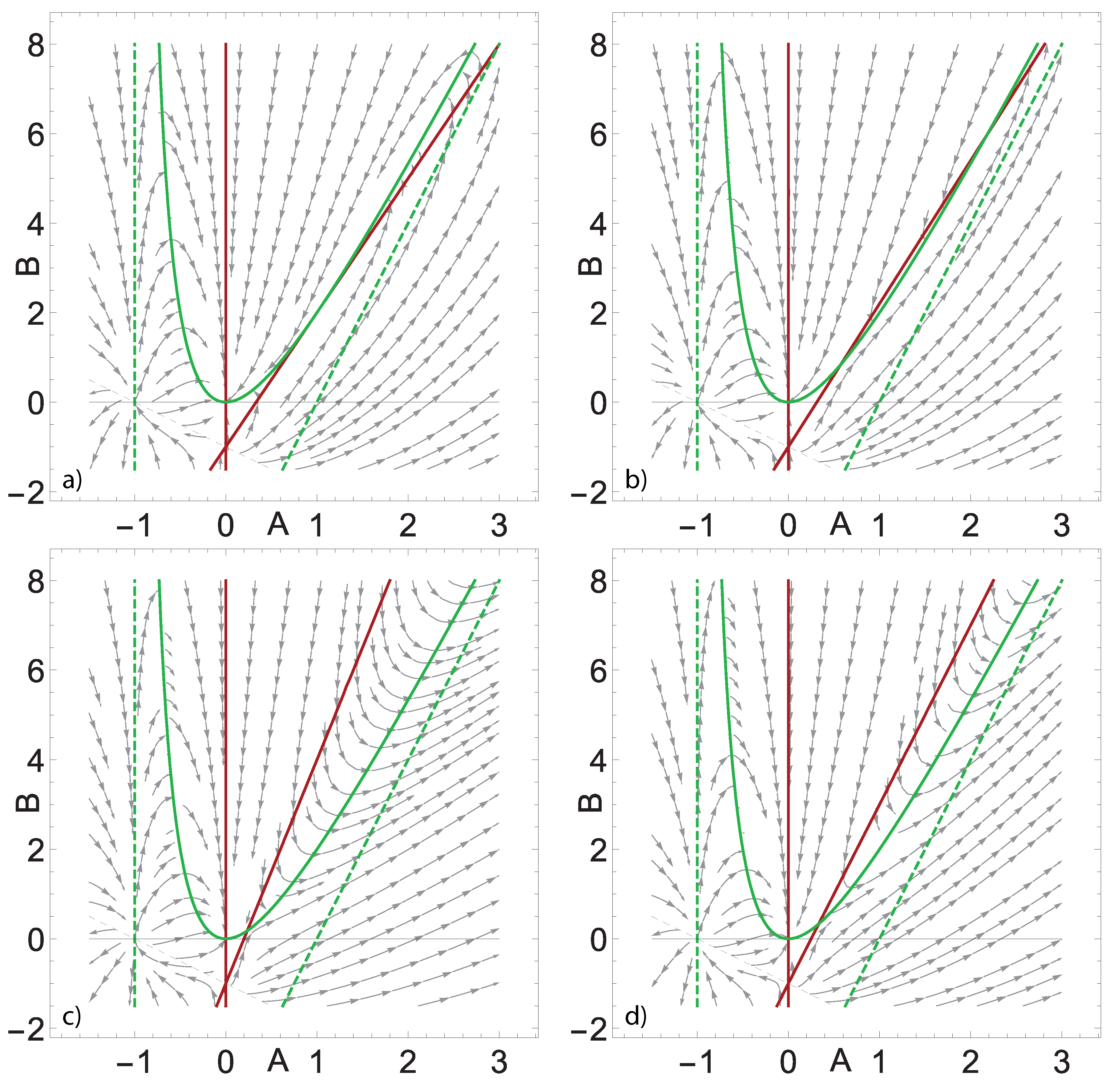

3.1. Analysis of Non-Spatially-Distributed System

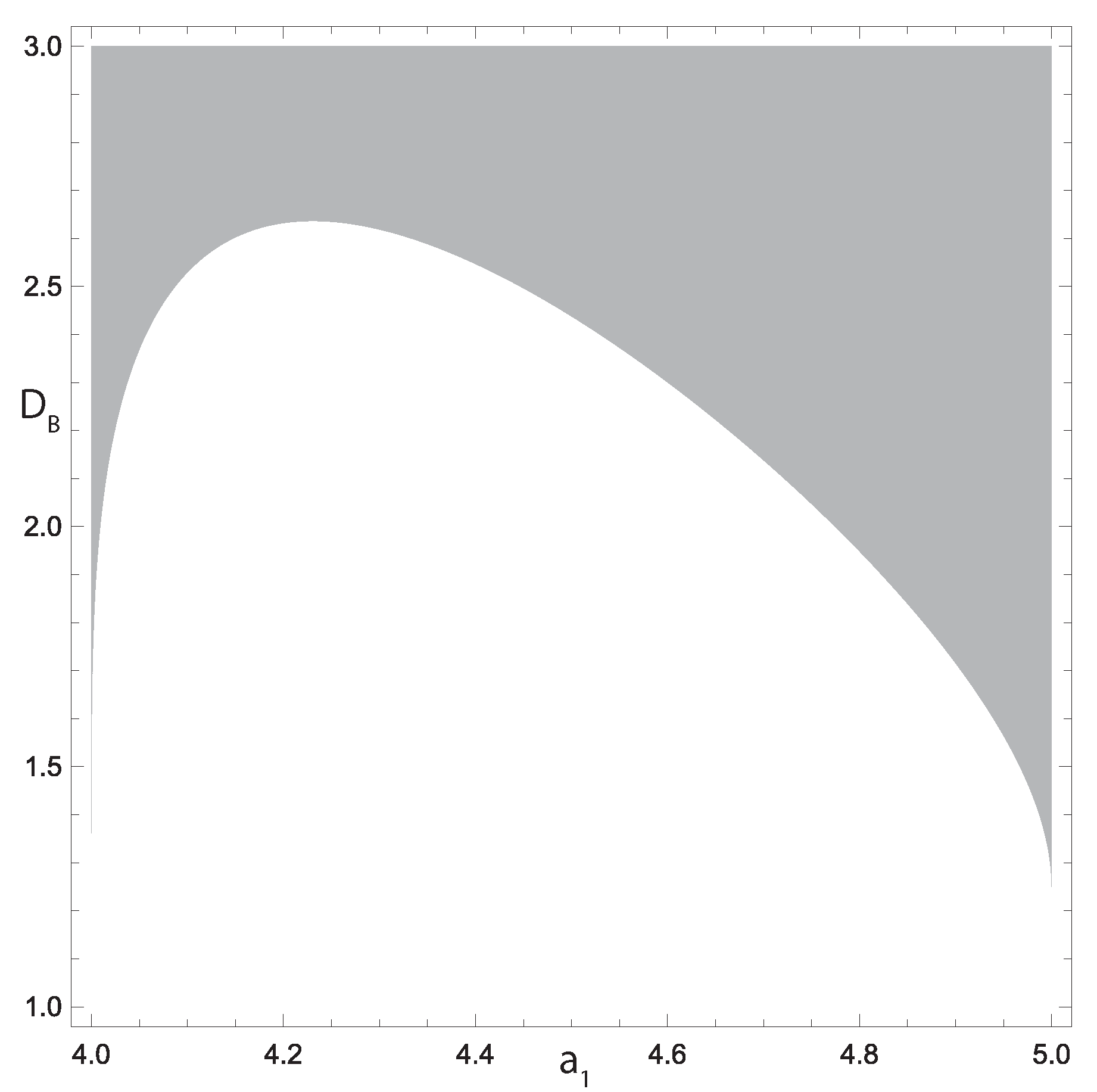

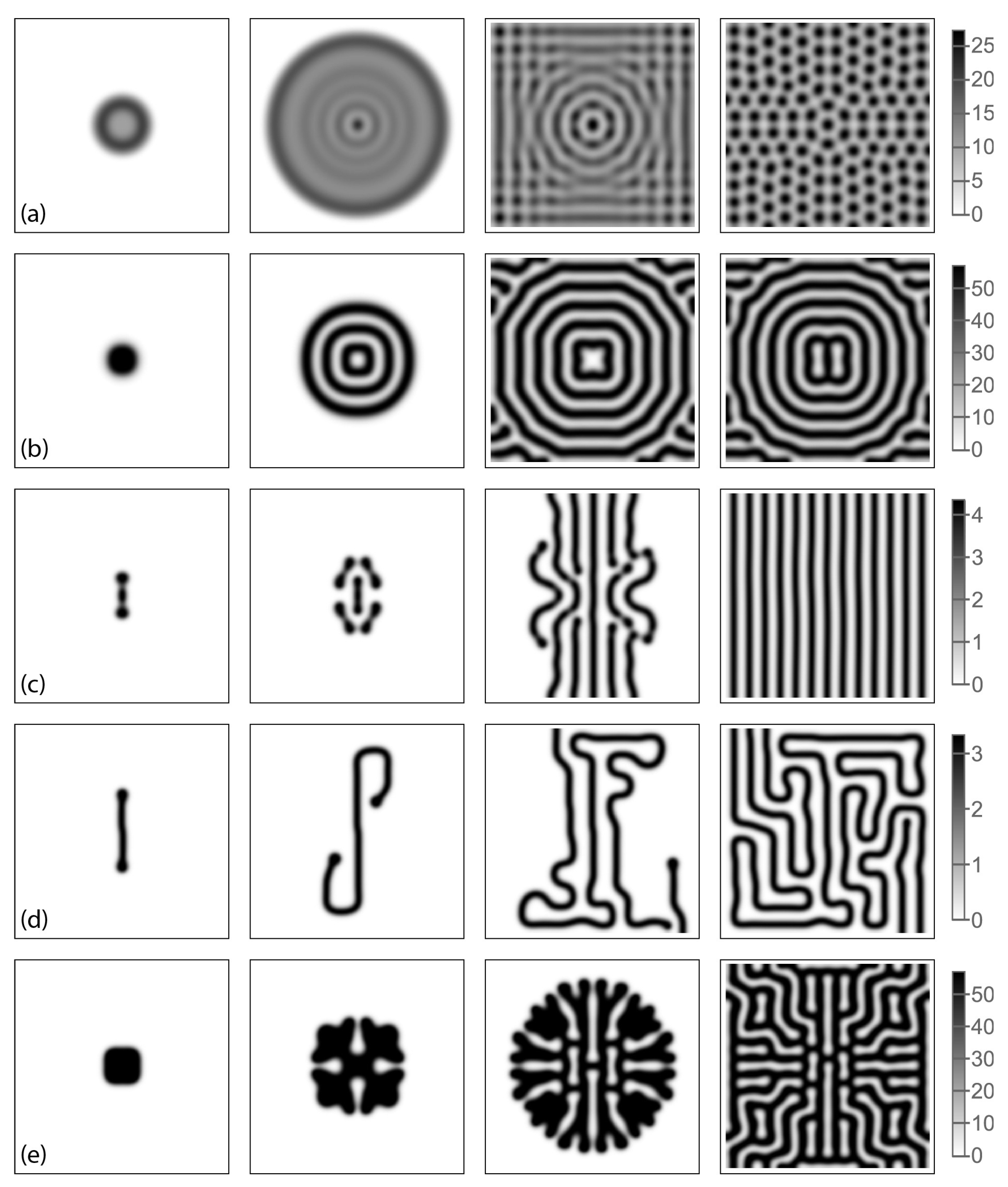

3.2. Turing Structures in a Spatially-Distributed System

4. Discussion

Acknowledgements

References

- Chovatiya, R.; Medzhitov, R. Stress, inflammation, and defense of homeostasis. Mol. Cell 2014, 54, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Deng, H.; Cui, H.; Fang, J.; Zuo, Z.; Deng, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhao, L. Inflammatory responses and inflammation-associated diseases in organs. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 7204–7218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchi, S.; Guilbaud, E.; Tait, S.W.G.; Yamazaki, T.; Galluzzi, L. Mitochondrial control of inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2023, 23, 159–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, C.; Pamer, E.G. Monocyte recruitment during infection and inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011, 11, 762–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Du, B.; Li, J.; Yang, Y.; Zhu, F. An insight into anti-inflammatory activities and inflammation related diseases of anthocyanins: A review of both in vivo and in vitro investigations. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, N.; Baby, D.; Rajguru, J.; Patil, P.; Thakkannavar, S.; Pujari, V. Inflammation and cancer. Ann. Afr. Med. 2019, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henein, M.Y.; Vancheri, S.; Longo, G.; Vancheri, F. The role of inflammation in cardiovascular disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tampa, M.; Neagu, M.; Caruntu, C.; Constantin, C.; Georgescu, S.R. Skin inflammation—A cornerstone in dermatological conditions. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayik, D.; Tross, D.; Haile, L.A.; Verthelyi, D.; Klinman, D.M. Regulation of the maturation of human monocytes into immunosuppressive macrophages. Blood Adv. 2017, 1, 2510–2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, B.; Ludewick, H.P.; Misra, A.; Lee, S.; Dwivedi, G. Macrophages and T cells in atherosclerosis: a translational perspective. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2019, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabas, I.; Lichtman, A.H. Monocyte-macrophages and T cells in atherosclerosis. Immunity 2017, 47, 621–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mills, C.D. M1 and M2 macrophages: Oracles of health and disease. Crit. Rev. Immunol. 2012, 32, 463–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arango Duque, G.; Descoteaux, A. Macrophage cytokines: involvement in immunity and infectious diseases. Front. Immunol. 2014, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wojdasiewicz, P.; Poniatowski, ŁA.; Szukiewicz, D. The role of inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines in the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis. Mediators Inflamm. 2014, 2014, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuerwegh, A.J.; Dombrecht, E.J.; Stevens, W.J.; Van Offel, J.F.; Bridts, C.H.; De Clerck, L.S. Influence of pro-inflammatory (IL-1α, IL-6, TNF-α, IFN-γ) and anti-inflammatory (IL-4) cytokines on chondrocyte function. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2003, 11, 681–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanghetti, E.A. The role of inflammation in the pathology of acne. J. Clin. Aesthet. Dermatol. 2013, 6, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Brown, S.J. Atopic eczema. Clin. Med. 2016, 16, 66–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diotallevi, F.; Offidani, A. Skin, autoimmunity and inflammation: A comprehensive exploration through scientific research. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turvey, S.E.; Broide, D.H. Innate immunity. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2010, 125, S24–S32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sroka-Tomaszewska, J.; Trzeciak, M. Molecular mechanisms of atopic dermatitis pathogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawada, Y.; Saito-Sasaki, N.; Mashima, E.; Nakamura, M. Daily lifestyle and inflammatory skin diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dainichi, T.; Hanakawa, S.; Kabashima, K. Classification of inflammatory skin diseases: A proposal based on the disorders of the three-layered defense systems, barrier, innate immunity and acquired immunity. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2014, 76, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshimura, A.; Aki, D.; Ito, M. SOCS, SPRED, and NR4a: Negative regulators of cytokine signaling and transcription in immune tolerance. Proc. Jpn. Acad. Ser. B Phys. Biol. Sci. 2021, 97, 277–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cianciulli, A.; Calvello, R.; Porro, C.; Lofrumento, D.D.; Panaro, M.A. Inflammatory skin diseases: Focus on the role of suppressors of cytokine signaling (SOCS) proteins. Cells 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, L.A.; Cork, M.J.; Amagai, M.; De Benedetto, A.; Kabashima, K.; Hamilton, J.D.; Rossi, A.B. Type 2 inflammation contributes to skin barrier dysfunction in atopic dermatitis. JID Innov. 2022, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herald, M.C. General model of inflammation. Bull. Math. Biol. 2010, 72, 765–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikaein, N.; Tuerxun, K.; Cedersund, G.; Eklund, D.; Kruse, R.; Särndahl, E.; Nånberg, E.; Thonig, A.; Repsilber, D.; Persson, A.; Nyman, E. Mathematical models disentangle the role of IL-10 feedbacks in human monocytes upon proinflammatory activation. J. Biol. Chem. 2023, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Khatib, N.; Genieys, S.; Volpert, V. Atherosclerosis initiation modeled as an inflammatory process. Mathematical Modelling of Natural Phenomena 2007, 2, 126–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hajj, W.; El Khatib, N.; Volpert, V. Inflammation propagation modeled as a reaction-diffusion wave. Math. Biosci. 2023, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, M.C.; Hohenberg, P.C. Pattern formation outside of equilibrium. Reviews of modern physics 1993, 65, 851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turing, A.M. The chemical basis of morphogenesis. Bulletin of mathematical biology 1990, 52, 153–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, M.P.; Williamson, S.; Fallon, J.F.; Meinhardt, H.; Prum, R.O. Molecular evidence for an activator–inhibitor mechanism in development of embryonic feather branching. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2005, 102, 11734–11739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H.; Sun, M.; Zhao, X. Turing mechanism underlying a branching model for lung morphogenesis. PloS one 2017, 12, e0174946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raspopovic, J.; Marcon, L.; Russo, L.; Sharpe, J. Digit patterning is controlled by a Bmp-Sox9-Wnt Turing network modulated by morphogen gradients. Science 2014, 345, 566–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, J.H.; Freeman, D.C.; Emlen, J.M. Antisymmetry, directional asymmetry, and dynamic morphogenesis. In Developmental instability: Its origins and evolutionary implications; Springer, 1994; pp. 123–139. [Google Scholar]

- De Kepper, P.; Castets, V.; Dulos, E.; Boissonade, J. Turing-type chemical patterns in the chlorite-iodide-malonic acid reaction. Physica D: Nonlinear Phenomena 1991, 49, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astrov, Y.; Ammelt, E.; Teperick, S.; Purwins, H.G. Hexagon and stripe Turing structures in a gas discharge system. Physics Letters A 1996, 211, 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinelli, L.; Tissoni, G.; Brambilla, M.; Prati, F.; Lugiato, L. Spatial solitons in semiconductor microcavities. Physical Review A 1998, 58, 2542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Short, M.B.; Brantingham, P.J.; Bertozzi, A.L.; Tita, G.E. Dissipation and displacement of hotspots in reaction-diffusion models of crime. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2010, 107, 3961–3965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tóth, Á.; Horváth, D. Diffusion-driven instabilities by immobilizing the autocatalyst in ionic systems. Chaos: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Nonlinear Science 2015, 25, 064304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nesterenko, A.M.; Kuznetsov, M.B.; Korotkova, D.D.; Zaraisky, A.G. Morphogene adsorption as a Turing instability regulator: Theoretical analysis and possible applications in multicellular embryonic systems. PloS one 2017, 12, e0171212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuznetsov, M.; Polezhaev, A. Widening the criteria for emergence of Turing patterns. Chaos: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Nonlinear Science 2020, 30, 033106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Younes, G.A.; Kuznetsov, M.; Khatib, N.E.; Volpert, V. Mathematical modeling of the interaction of atherosclerotic inflammation and chemotaxis: formation of fatty streaks. Submitted.

- Nadin, G.; Ogier-Denis, E.; Toledo, A.I.; Zaag, H. A Turing mechanism in order to explain the patchy nature of Crohn’s disease. Journal of Mathematical Biology 2021, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grudzinska, M.K.; Kurzejamska, E.; Bojakowski, K.; Soin, J.; Lehmann, M.H.; Reinecke, H.; Murry, C.E.; Soderberg-Naucler, C.; Religa, P. Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein 1–Mediated Migration of Mesenchymal Stem Cells Is a Source of Intimal Hyperplasia. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology 2013, 33, 1271–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- N, O.A. Atherosclerosis; Palmarium Academic Publishing, 2013.

- Gui, T.; Shimokado, A.; Sun, Y.; Akasaka, T.; Muragaki, Y. Diverse roles of macrophages in atherosclerosis: from inflammatory biology to biomarker discovery. Mediators of inflammation 2012, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramji, D.P.; Davies, T.S. Cytokines in atherosclerosis: Key players in all stages of disease and promising therapeutic targets. Cytokine & growth factor reviews 2015, 26, 673–685. [Google Scholar]

- Almer, G.; Frascione, D.; Pali-Scholl, I.; Vonach, C.; Lukschal, A.; Stremnitzer, C.; Diesner, S.C.; Jensen-Jarolim, E.; Prassl, R.; Mangge, H. Interleukin-10: an anti-inflammatory marker to target atherosclerotic lesions via PEGylated liposomes. Molecular pharmaceutics 2013, 10, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman, A.; Hao, W. A mathematical model of atherosclerosis with reverse cholesterol transport and associated risk factors. Bulletin of mathematical biology 2015, 77, 758–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, X.; Boisvert, W.A.; Parthasarathy, S. The role of IL-10 in atherosclerosis. Atherogenesis: InTech, 2012; 361–84. [Google Scholar]

- Bautin, N.; Leontovich, E. Methods and ways of the qualitative analysis of dynamical systems in a plane. Nauka. Moscow.(Russian). Botelho, F. and Gaiko, VA (2006). Global analysis of planar neural networks. Nonlinear Anal 1990, 64, 117. [Google Scholar]

- Anderton, H.; Alqudah, S. Cell death in skin function, inflammation, and disease. Biochemical Journal 2022, 479, 1621–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, A.V.; Soulika, A.M. The Dynamics of the Skin’s Immune System. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuznetsov, M.; Kolobov, A.; Polezhaev, A. Pattern formation in a reaction-diffusion system of Fitzhugh-Nagumo type before the onset of subcritical Turing bifurcation. Physical Review E 2017, 95, 052208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaminaga, A.; Vanag, V.K.; Epstein, I.R. A reaction–diffusion memory device. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2006, 45, 3087–3089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muratov, C.; Osipov, V. Scenarios of domain pattern formation in a reaction-diffusion system. Physical Review E 1996, 54, 4860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newby, A.C.; Zaltsman, A.B. Fibrous cap formation or destruction—the critical importance of vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation, migration and matrix formation. Cardiovascular research 1999, 41, 345–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerthoffer, W.T. Mechanisms of vascular smooth muscle cell migration. Circulation research 2007, 100, 607–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).