Submitted:

07 October 2023

Posted:

10 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Linear model

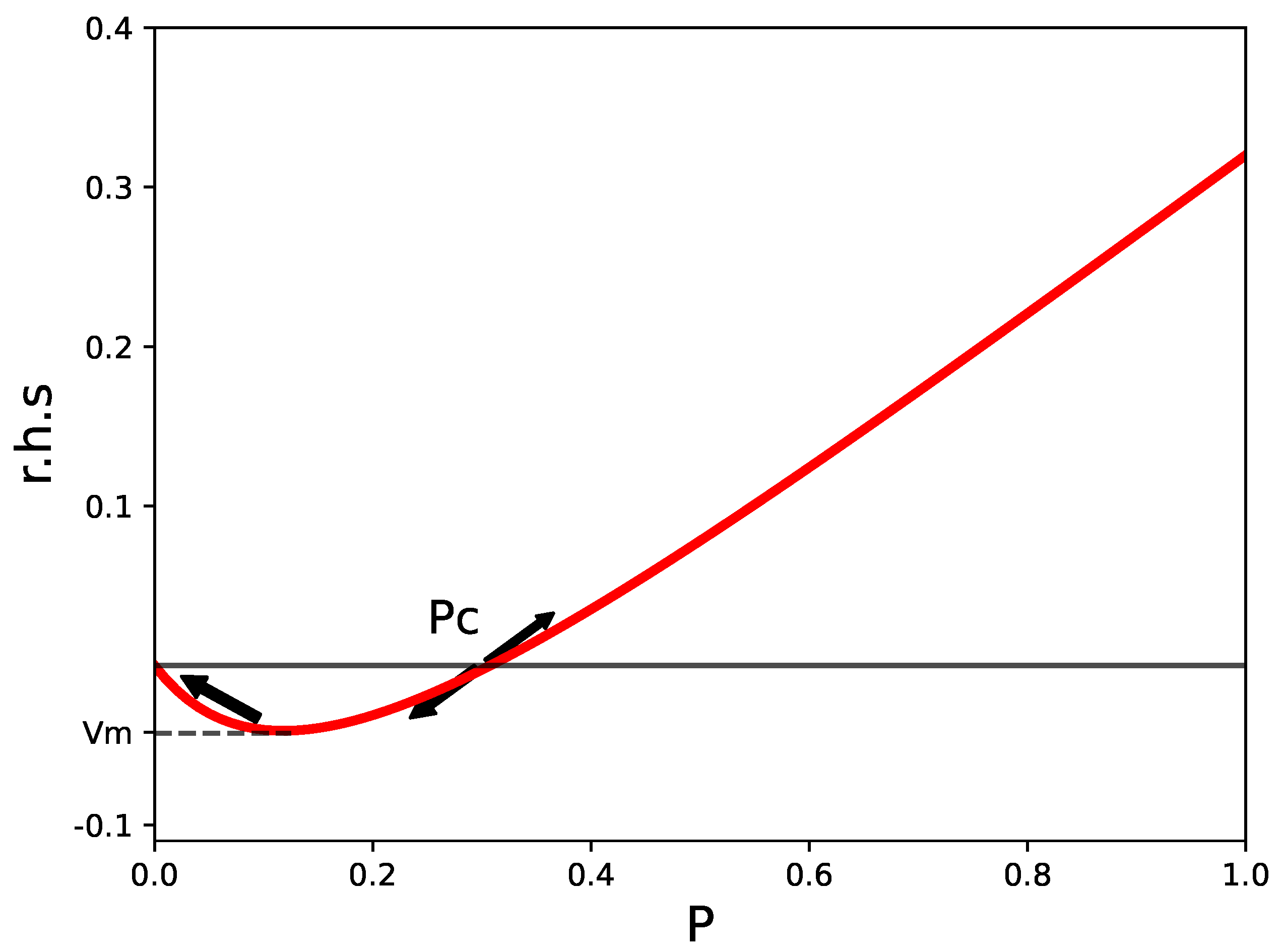

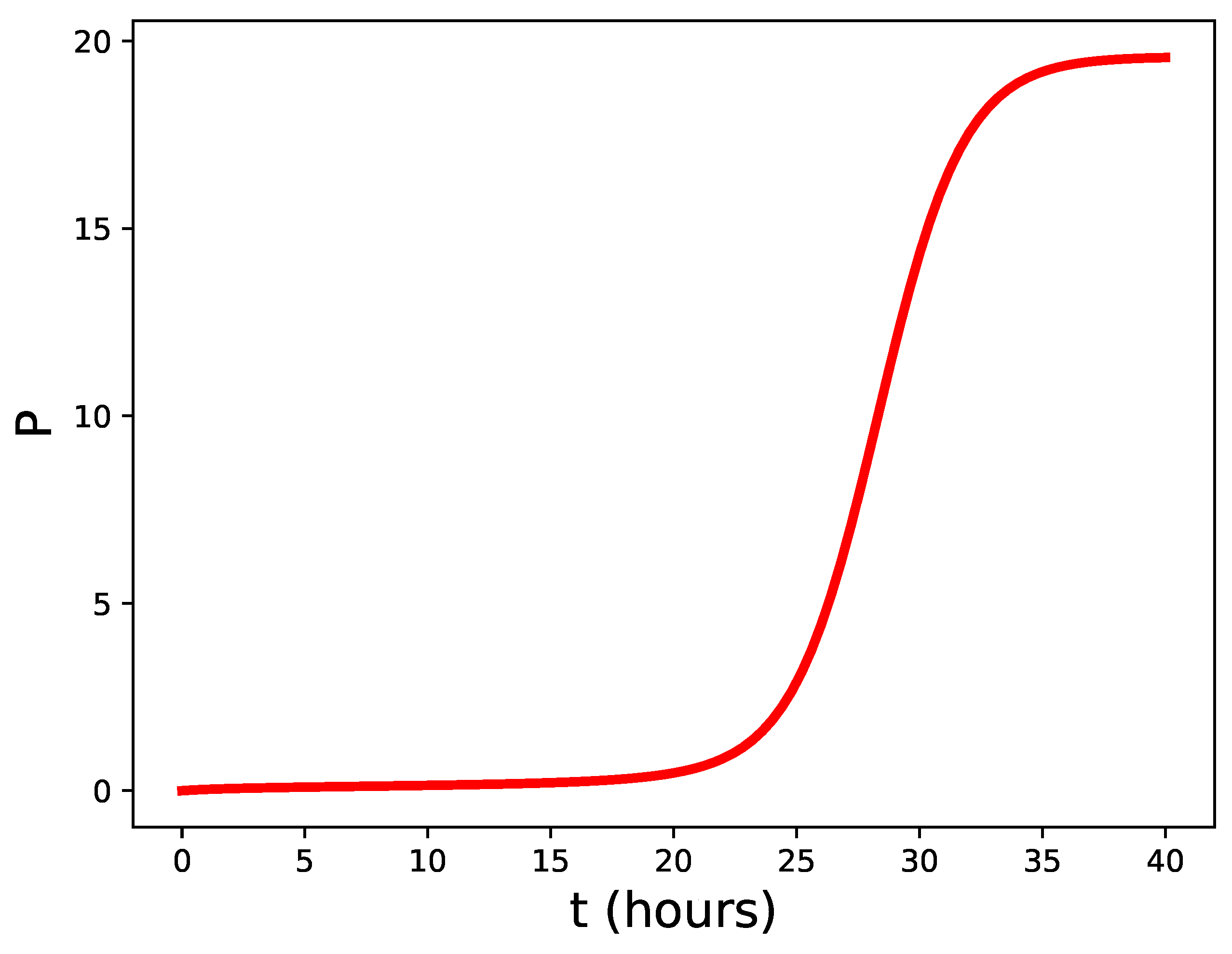

2.2. Nonlinear model.

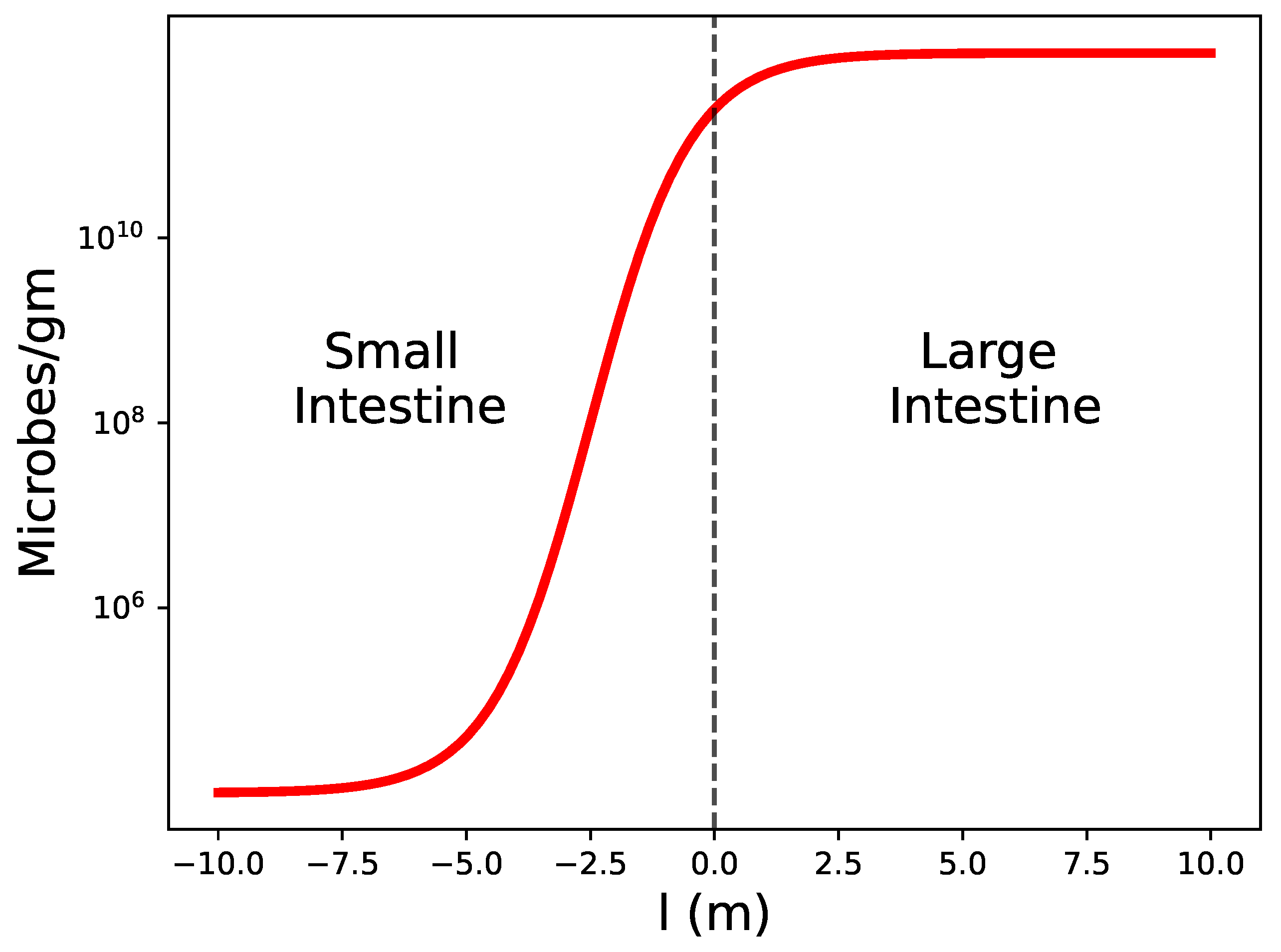

2.3. Reference value for the number of pathogens.

2.4. Stability condition in tissues.

2.5. A second consequence of the unstable fixed point.

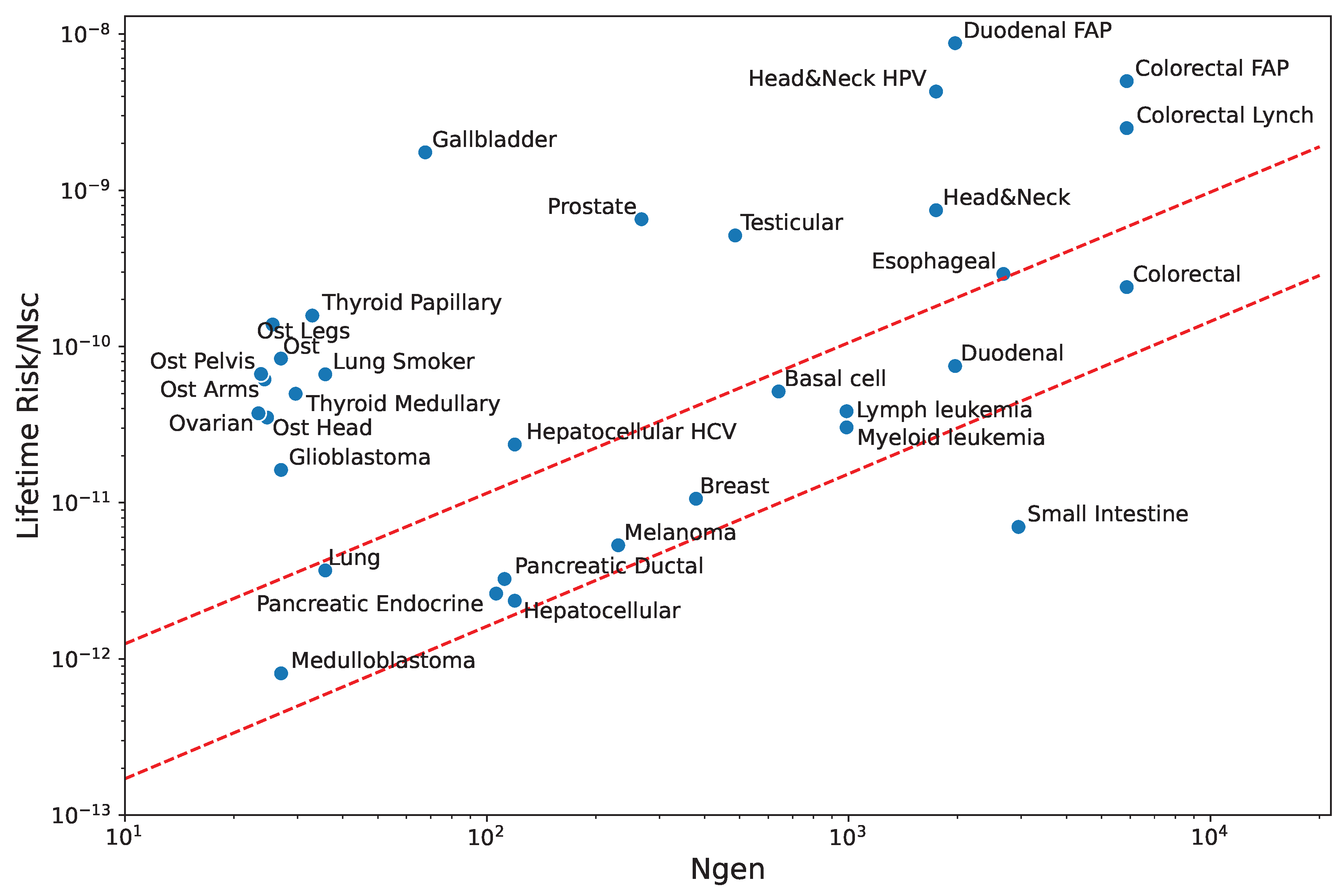

2.6. A qualitative comparison.

2.7. Other tissues.

2.8. Immunity to cancer.

3. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Murphy, K.; Weaver, C. Janeway’s immunobiology; Garland science, 2016.

- Akira, S.; Uematsu, S.; Takeuchi, O. Pathogen recognition and innate immunity. Cell 2006, 124, 783–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demaria, O.; Cornen, S.; Daëron, M.; Morel, Y.; Medzhitov, R.; Vivier, E. Harnessing innate immunity in cancer therapy. Nature 2019, 574, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohler, R.R.; Lee, K.S.; Asachenkov, A.L.; Marchuk, G.I. A systems approach to immunology and cancer. IEEE transactions on systems, man, and cybernetics 1994, 24, 632–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.M.; Tato, C.M.; Furman, D. Systems immunology: just getting started. Nature immunology 2017, 18, 725–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, L.C.; Jenkins, S.J.; Allen, J.E.; Taylor, P.R. Tissue-resident macrophages. Nature immunology 2013, 14, 986–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beckers, H.; Van der Hoeven, J. Growth rates of Actinomyces viscosus and Streptococcus mutans during early colonization of tooth surfaces in gnotobiotic rats. Infection and Immunity 1982, 35, 583–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mai, M.; Wang, K.; Huber, G.; Kirby, M.; Shattuck, M.D.; O’Hern, C.S. Outcome prediction in mathematical models of immune response to infection. PloS one 2015, 10, e0135861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nemytskii, V.V. Qualitative theory of differential equations; Vol. 2083, Princeton University Press, 2015.

- O’Hara, A.M.; Shanahan, F. The gut flora as a forgotten organ. EMBO reports 2006, 7, 688–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clevers, H.C.; Bevins, C.L. Paneth cells: maestros of the small intestinal crypts. Annual review of physiology 2013, 75, 289–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, C.; Hugot, J.P.; Barreau, F.; others. Peyer’s patches: the immune sensors of the intestine. International journal of inflammation 2010, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Sorge, N.M.; Doran, K.S. Defense at the border: the blood–brain barrier versus bacterial foreigners. Future microbiology 2012, 7, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- França, L.R.; Auharek, S.A.; Hess, R.A.; Dufour, J.M.; Hinton, B.T. Blood-tissue barriers: morphofunctional and immunological aspects of the blood-testis and blood-epididymal barriers. Biology and Regulation of Blood-Tissue Barriers 2013, pp. 237–259.

- Merritt, M.E.; Donaldson, J.R. Effect of bile salts on the DNA and membrane integrity of enteric bacteria. Journal of medical microbiology 2009, 58, 1533–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frank, S.A. Dynamics of cancer: incidence, inheritance, and evolution; Princeton University Press, 2007.

- Herrero, R.; Leon, D.A.; Gonzalez, A. A one-dimensional parameter-free model for carcinogenesis in gene expression space. Scientific Reports 2022, 12, 4748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reya, T.; Morrison, S.J.; Clarke, M.F.; Weissman, I.L. Stem cells, cancer, and cancer stem cells. nature 2001, 414, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomasetti, C.; Vogelstein, B. Variation in cancer risk among tissues can be explained by the number of stem cell divisions. Science 2015, 347, 78–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.; Powers, S.; Zhu, W.; Hannun, Y.A. Substantial contribution of extrinsic risk factors to cancer development. Nature 2016, 529, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hooper, D.C.; Phares, T.W.; Kean, R.B.; Mikheeva, T. Regional Differences in Blood-Brain Barrier. J Immunol 2006, 176, 7666–7675. [Google Scholar]

- Varoga, D.; Wruck, C.; Tohidnezhad, M.; Brandenburg, L.; Paulsen, F.; Mentlein, R.; Seekamp, A.; Besch, L.; Pufe, T. Osteoblasts participate in the innate immunity of the bone by producing human beta defensin-3. Histochemistry and cell biology 2009, 131, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perrotta, C.; De Palma, C.; Clementi, E.; Cervia, D. Hormones and immunity in cancer: are thyroid hormones endocrine players in the microglia/glioma cross-talk? Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience 2015, 9, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Tissue | Pathogen | Barrier height | Annihilation | Cancer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| flow () | () | rate () | risk | |

| Small bowel | Very High | High | High | Low |

| Colon | Very High | Very High | Normal | Normal |

| Lung | Very High | Very High | Normal | Normal |

| Skin | Very High | Very High | Normal | Normal |

| Duodenum | High | High | Normal | Normal |

| Blood | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal |

| Pancreas | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal |

| Liver | High | High | Normal | Normal |

| Cerebellum | Normal | High | Normal | Normal |

| Esophagus | High | High | Normal | Normal |

| Head & Neck | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal |

| Germ cells | Normal | High | Low | High |

| Brain | Normal | High | Low | High |

| Gallbladder | Normal | High | Low | High |

| Bone | Normal | High | Low | High |

| Thyroid | Normal | High | Low | High |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).