1. Introduction

Viral infections remain a major global health concern due to their rapid transmissibility and potential to cause significant morbidity and mortality. Epidemics such as seasonal influenza and pandemics like COVID-19 have underscored the urgency of understanding the biological mechanisms underlying virus-host interactions, particularly during the early stages of infection [

26,

30]. Once inside host tissue, viruses infect susceptible cells, hijack their replication machinery, and produce progeny virions. These viral particles propagate through local diffusion and direct intercellular transmission, forming spatial infection waves [

2,

30].

The immune system responds with a layered defense strategy involving both innate and adaptive responses. The innate immune system acts rapidly, within hours, and provides a generalized defense before the adaptive immune system becomes fully engaged. Central to this early response are inflammatory cytokines and immune cells such as macrophages, which shape the tissue environment and limit viral replication [

13,

17].

Inflammatory cytokines and programmed cell death.

Upon detecting viral components, infected cells initiate signaling cascades leading to the production of cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and interferons. These molecules orchestrate immune responses and trigger programmed cell death (PCD) in infected cells, thereby halting viral replication [

18]. Several forms of PCD have been implicated in viral infections, including apoptosis, pyroptosis, necroptosis, and PANoptosis—a combined form integrating features of all three. Although essential, dysregulated or excessive cell death may result in tissue damage and systemic inflammation [

10,

17].

In our model, inflammatory cytokines are secreted by both infected cells and activated macrophages. These cytokines enhance immune-mediated destruction of infected cells, establishing a feedback loop that can contain infection, depending on parameter values.

Macrophage recruitment and activation.

Macrophages are key innate immune effectors involved in pathogen detection, phagocytosis, cytokine production, and immune regulation. During infection, blood monocytes are recruited to the tissue and differentiate into macrophages. These cells exhibit phenotypic plasticity, polarizing into M1 (pro-inflammatory, microbicidal) or M2 (anti-inflammatory, tissue-repairing) states based on environmental signals [

13,

22].

Here, we model circulating macrophages that become activated through interactions with virus particles and pro-inflammatory cytokines. Once activated, they amplify the cytokine pool and facilitate the clearance of infected cells. Their population dynamics are shaped by production, activation, and degradation processes.

Modeling infection propagation in tissue.

The spatial spread of infection arises from the interaction between viral replication, diffusion, and immune activity. Reaction-diffusion models provide a powerful framework to study such phenomena, enabling the analysis of wavefront propagation and spatiotemporal dynamics [

2,

7,

23]. The wave speed reflects the efficiency of viral expansion, while the total viral load (integrated spatial virus concentration) quantifies infection burden [

23].

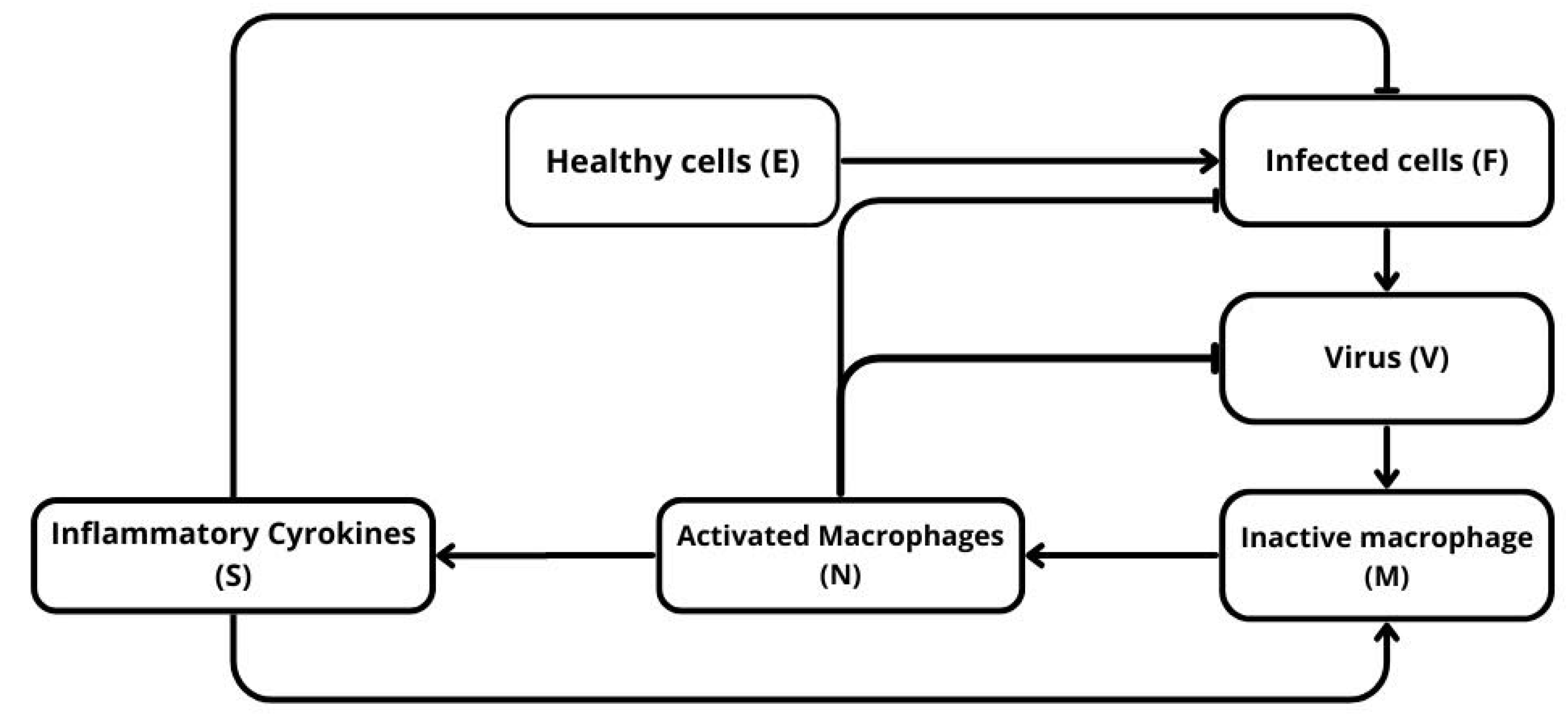

We extend classical models by integrating immune regulation through cytokine signaling and macrophage activation. Our system consists of five key components: uninfected cells (

E), infected cells (

F), virus particles (

V), inflammatory cytokines (

S), and activated macrophages (

N). Virus and infected cells are modeled as spatially distributed quantities, while

S and

N are treated as spatially homogeneous due their redistribution by blood circulation [

7,

19].

This study presents a novel spatial model of early viral infection incorporating immune regulatory feedback. We incorporate time delay representing intracellular viral replication and couple nonlinear dynamics of cytokine production and immune-mediated cell death. Next, we consider activation of macrophages by virus and cytokines, contributing to immune feedback. Analyzing the model, we determine the conditions of infection spreading and find the wave speed and viral load.

Numerical simulations complement the theoretical analysis and demonstrate how macrophage degradation rates and cytokine feedback strength can critically affect infection dynamics. Our results provide insights into the thresholds that separate controlled from uncontrolled viral propagation.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 presents the mathematical formulation of the model.

Section 3 analyzes the traveling wave solutions and conditions for their existence.

Section 4 provides numerical simulations and investigates the impact of immune parameters.

Section 5 discusses biological implications and outlines future research directions.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the model. Healthy cells E are infected by the virus V and become infected cells F, which produce more virus and stimulate the immune response. The virus activates circulating macrophages M into activated macrophages N, which in turn release inflammatory cytokines S. These cytokines amplify macrophage activation and promote the elimination of infected cells.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the model. Healthy cells E are infected by the virus V and become infected cells F, which produce more virus and stimulate the immune response. The virus activates circulating macrophages M into activated macrophages N, which in turn release inflammatory cytokines S. These cytokines amplify macrophage activation and promote the elimination of infected cells.

3. System Without Degradation of Activated Macrophages

We begin the study of system (2.6)-(2.10) with the case

. This assumption simplifies the analysis and will allow us to determine

from a single algebraic equation. Under this assumption, we have

. Therefore, we consider the following system:

Integrating (3.1), we obtain:

Integration of the sum of equations (3.1) and (3.2) gives

From equation (3.3), we express

as follows:

Thus, we obtain the following system of equations with respect to the variables

(

),

and

:

From (3.6) and (3.8), we obtain:

Substituting this expression into (3.7), we derive the equation with respect to

:

where

3.1. Existence of Solution

We will now study the existence of solutions of equation (3.9) for .

then equation (3.9) has a solution .

Proof. Set

. Then

for

, and

as

. Therefore, if

then equation (3.9) has a solution

. The last inequality is equivalent to (3.10). The proposition is proved.

□

In order to determine the number of solutions of equation (3.9), we find the second derivative

. We have

where

. Next,

where

then there is such that

Proof. The sign of the second derivative of

for

coincides with the sign of the difference

for

, or with the sign of the polynomial

Note that

. Therefore,

If condition (3.11) is satisfied, then and for all . If condition (3.11) is satisfied, then . Since is a monotonically increasing function for , then there is some such that for and for . This property of the function provides (3.14). The proposition is proved.

□

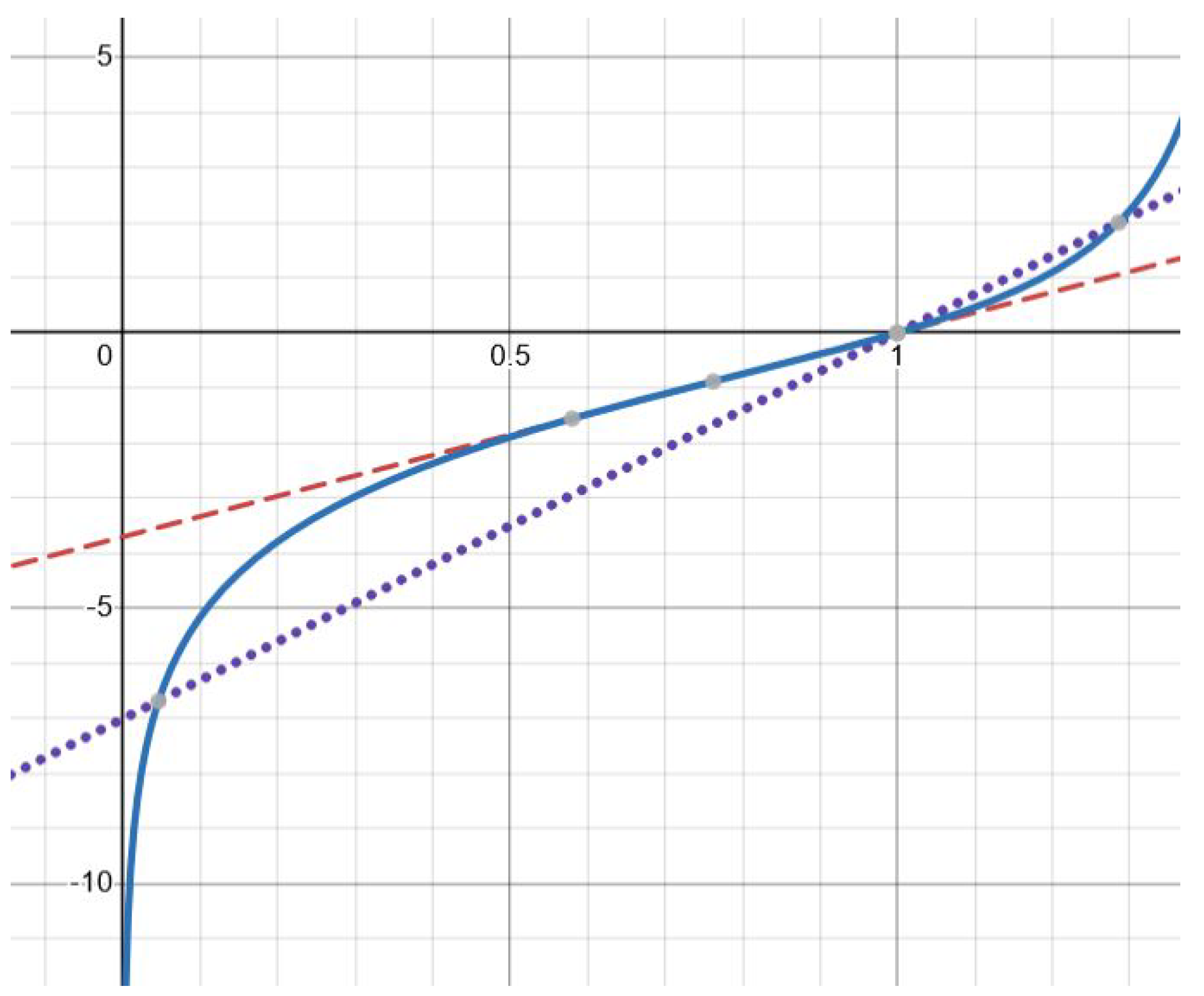

Theorem 3.3.

If condition (3.11) is satisfied, then equation (3.9) has a solution if and only if inequality (3.10) holds. Moreover, this solution is unique. If condition (3.13) is satisfied, then there exists such that equation (3.9) has a solution in and only if . This solution is unique for , and there are two solutions for .

Proof. Let (3.11) be satisfied. According to Proposition 3.2, the function

is concave for

. Since equation (3.9), that is,

has solution

, then it has a unique solution

if

, and no such solution otherwise.

Let now (3.13) be satisfied. Then existence of solution for follows from Proposition 3.1. Suppose that the solution is not unique and, for certainty, there are two solutions , . The derivatives of the left-hand side and of the right-hand side of equation (3.9) are equal to each other between solutions and , and between solutions and . Therefore, at least for two values of . According to Proposition 3.2, the is a positive function in the interval with a single minimum. Since , then equation can have at most one solution. This contradiction proves uniqueness of solution of equation (3.9) in .

Similar arguments show that equation (3.9) does not have solution in for R sufficiently small, in particular, if . Hence, there is such that equation (3.9) does not have solutions for .

Finally, there are exactly two solutions for

(

Figure 2). This follows from a similar analysis of the derivatives

and

. The details are left to the reader. The theorem is proved.

□

Approximate solution.

Analysis of equation (3.9) shows that its solution converges to 0 as

R increases. Therefore, for

R sufficiently large,

, and

can be neglected in the left-hand side of this equation. On the other hand,

. Hence, we obtain approximate equality

. Thus, we can find

Note that and depend on the wave speed c. We will determine it in the next section.

3.2. Wave Speed

In order to determine the wave speed, we use the linearization method. We replace

u by

at

Therefore, we obtain the following linearized system of equations for

f and

The integral

is considered here as a given constant. Let us look for the solution of this system in the form

Substituting these functions into equations (3.15), (3.16), we obtain:

In order to find the minimal wave speed, we should determine the minimal value of

c for which this system of equations has a positive solution

since the solution is decreasing at infinity. Introducing an independent parameter

and excluding

from the previous two equations, we obtain the following equation:

where

Here

and

is the value for which the denominator vanish. Such value exists if

If condition (3.20) is not satisfied, then the function is defined for all , and . The minimal wave speed in this case equals zero.

Note that this condition is not explicit. Indeed, the integral

depend on the unknown wave speed. Therefore,

P and the function

also depend on it, and (3.19) is an equation with respect to

c. However,

P can be estimated by the respective values for

and

:

If

then

. If inequality (3.21) is opposite, then

is larger than

. We will use these values below to determine different regimes of infection progression.

3.3. Regimes of Infection Progression

We derived above two critical conditions that determine infection progression. Condition (3.10) provides the existence of solution of equation (3.9) in the interval . Condition (3.20) implies that the wave speed is positive. Both of them are necessary conditions of the existence of infection wave, but their sufficiency is not proved.

Note that

such that condition (3.10) coincides with condition (3.20) if

. Hence, if

then neither of conditions (3.10) and (3.20) are satisfied, and infection wave does not exist.

However, infection can spread in a transient regime with gradual extinction. In order to illustrate this regime, let us consider system (2.1)-(2.5) under the assumption that

. This means that the concentrations of inflammatory cytokines and macrophages remain zero (as for the initial condition). Hence, this model is the same as in the case of infection spreading in cell culture [

4]. It propagates if

. Note that

is obtained from the virus replication number

R if

.

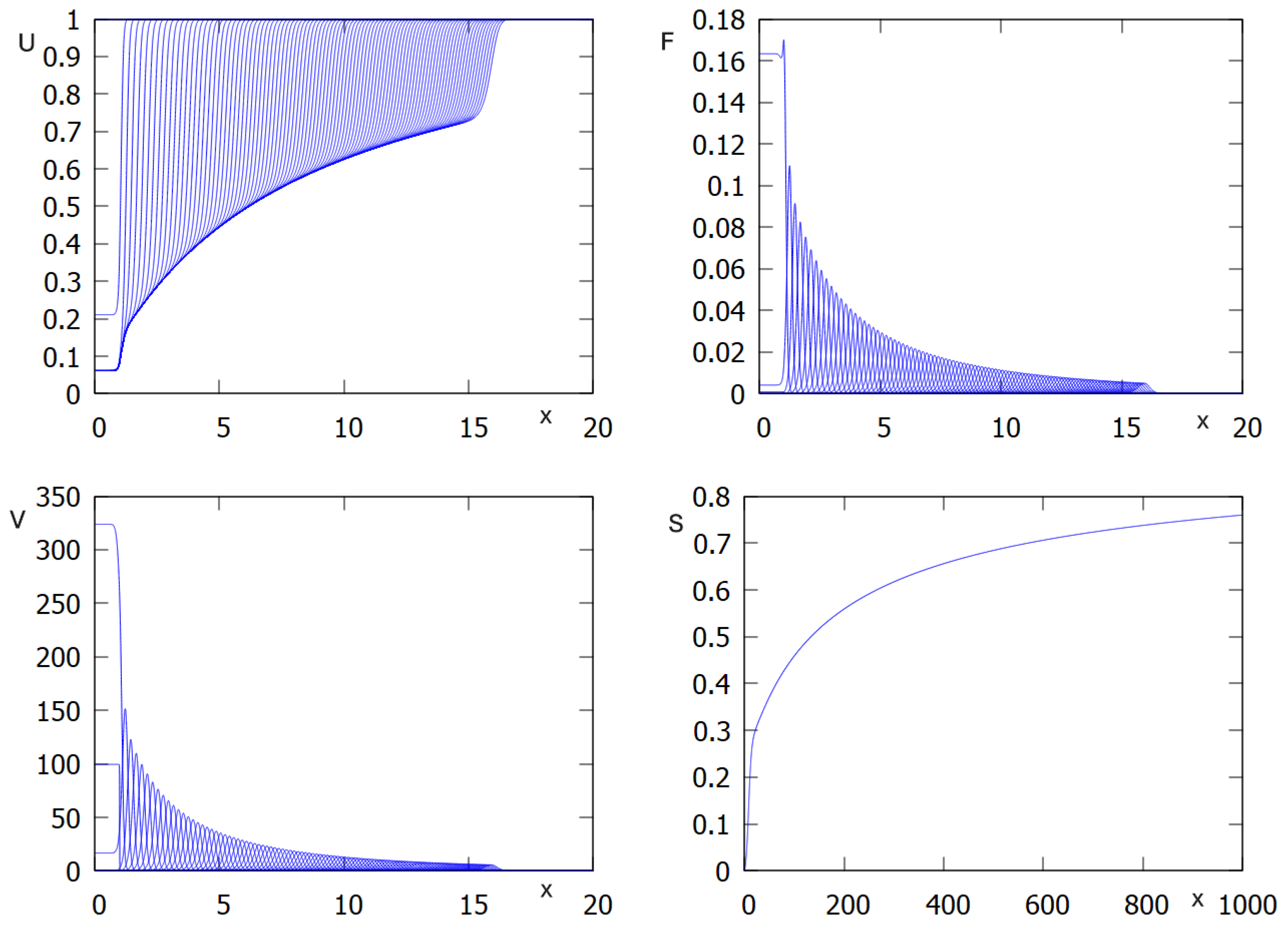

We now return to the full system with

assuming that

. In the beginning of the simulations, when the concentration of macrophages is low, infection propagates as for the case without macrophages (

Figure 3). However, since their concentration grows with time, viral load decreases and converges to zero. Thus, in this example, infection is progressively eliminated by the innate immune response.

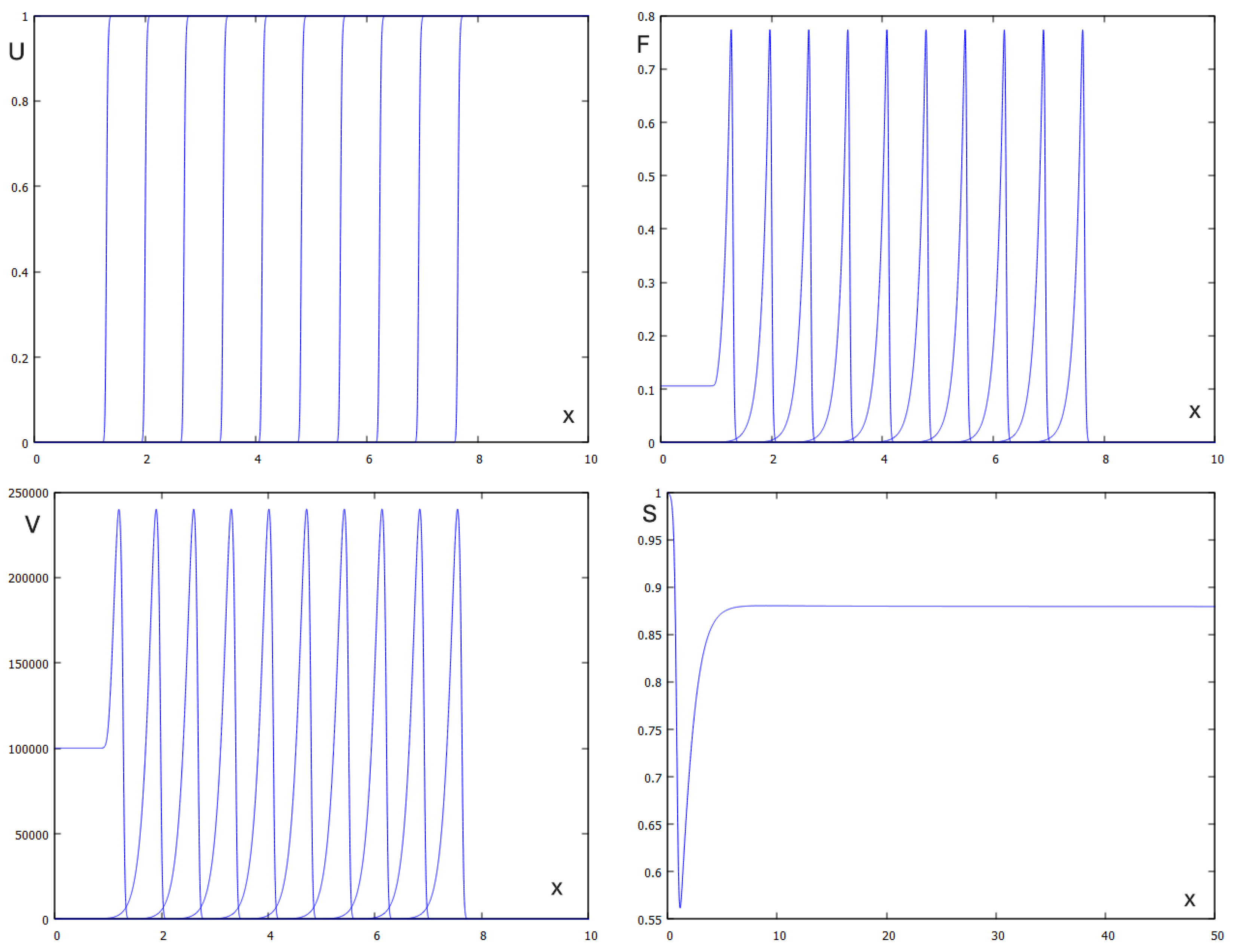

On the other hand, if

then both conditions (3.10) and (3.20) are satisfied, and we observe propagation of infection wave. Note that the analytical results obtained above do not prove the existence and stability of such wave but numerical simulations confirm infection propagation as a reaction-diffusion wave (

Figure 4). The analytical and numerical values of the viral load and wave speed are in good agreement. The analytic value of viral load is

and its numerical value is

The analytic value of the wave speed ic

and the numerical value is

Figure 5 shows the dependence of the wave speed and the viral load on time delay in virus replication. Both of them decay with increasing

In order to continue the analysis of the regimes of infection progression, suppose that condition (3.21) is satisfied. Then

. We will consider now the case where condition (3.10) is satisfied and condition (3.20) is not satisfied. This means that

and

For any

,

, so that these two conditions are compatible. The first condition provides infection progression, while the second condition means that the wave speed equals zero, that is, infection wave extincts. We have previously observed such behavior in [

9] for the model with resident macrophages.

4. System with Degradation of Activated Macrophages

We consider the system (2.6)-(2.10). As in

Section 3, we derive the equation for

:

where

Note that for , we have , and we reduce this equation to the previous one.

Let us behavior of this function as

assuming that

. Note that

and

, since

. Therefore,

, since

. Dividing numerator and denominator of

N by this expression, we conclude that

. Hence,

. We conclude that

Thus, the right-hand side of equation (4.1) converges to

as

. Therefore, this equation has a solution

if

By virtue of approximation

in the vicinity of

, we conclude that

is bounded. Hence, condition (3.5) is equivalent to the condition

In order to determine

, we note that

and

, since

. Therefore,

We reduce this system to the single equation with respect to

S:

It has a positive solution

if

This solution can be found as a solution of the corresponding quadratic equation.

We proved the following proposition.

Proposition 4.1.

Suppose that and condition (4.5) is satisfied. If

then equation (4.1) has a solution . Here is a positive solution of equation (4.4), and . In the limit of small condition (4.6) coincides with condition (3.10).

Since is a decreasing function of as solution of equation (4.4), then this is also true for and for . Hence, the critical value of R decreases with increase of the macrophage death rate.

If equation (4.1) has a solution

, then we can determine viral load and wave speed (cf.

Section 3). However, the calculations becomes excessively complex and do not lead to explicit analytical formula. Hence, we restrict their investigation to numerical simulations (

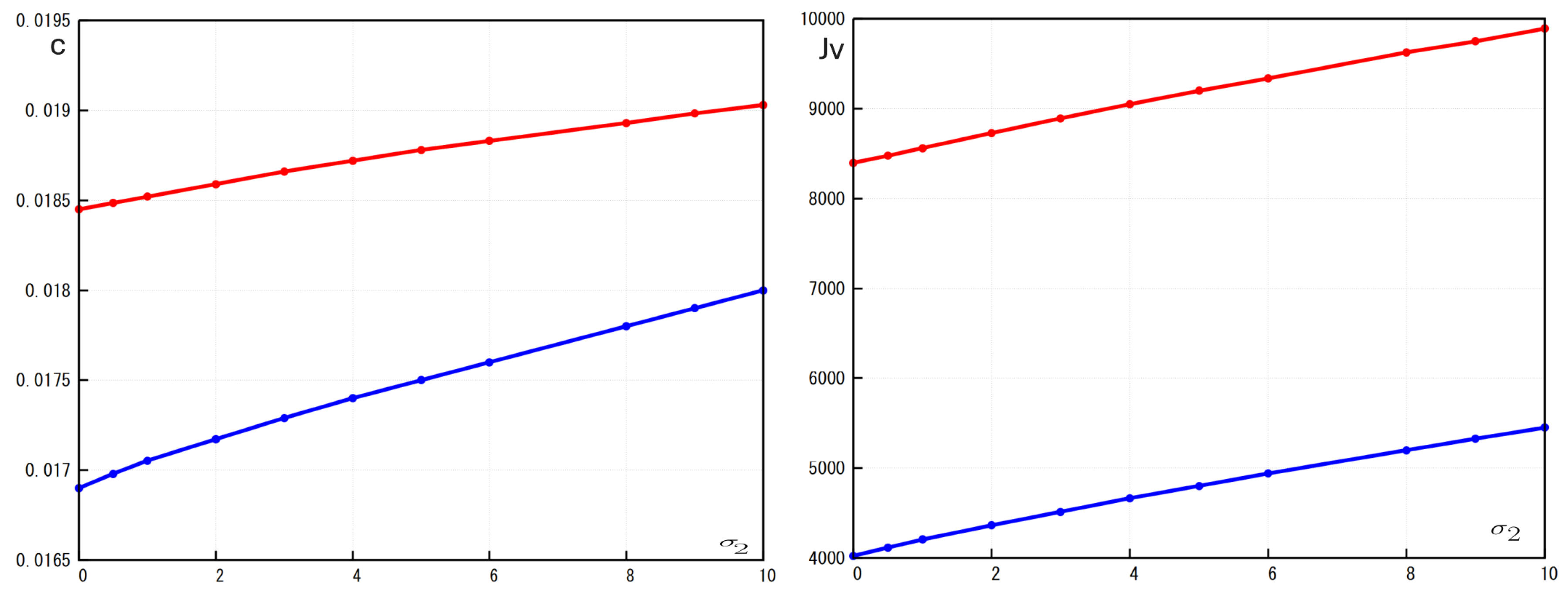

Figure 6). Both viral load and wave speed increase with the increase of

and decrease with increase of

. Hence, increasing the macrophage death rate promotes infection propagation while elimination of infected cells by macrophages down-regulates it.

5. Discussion

In this study, we developed and analyzed a spatial mathematical model that captures the early dynamics of viral infection in tissue, explicitly incorporating key elements of the innate immune response — namely, inflammatory cytokines and circulating macrophages.

The model consists of a hybrid system coupling three reaction-diffusion partial differential equations (for healthy cells, infected cells, and free virus particles) with two spatially homogeneous ordinary differential equations (for cytokines and activated macrophages). This structure allows us to explore both local and systemic effects, particularly travelling infection fronts.

The model integrates the most essential features of viral infections and immune response. In particuler, infection of healthy cells by viral particles and virus production by infected cells, clearance of infected cells via cytokines and macrophages, Cytokine production by infected cells and activated macrophages, activation of macrophages by both cytokines and virus, and optional degradation of activated macrophages (modeled via ).

Together, these interactions form a nonlinear feedback system, where immune activation is dynamically modulated by infection burden. This feedback is biologically supported by experimental studies on cytokine signaling and macrophage polarization [

6,

13,

14,

16,

28].

An important property of the model is its ability to represent the feedback loop formed by cytokines and activated macrophages. Infected cells trigger cytokine release, which promotes macrophage activation. In turn, these macrophages enhance cytokine production and contribute to the elimination of infected cells [

16,

28]. This forms a positive feedback loop that may facilitate rapid viral clearance.

However, if the degradation of activated macrophages is included (

), the feedback becomes self-limiting. This addition reflects biologically realistic processes such as macrophage exhaustion, apoptosis, or immune regulation [

14,

17]. The loss of effector cells dampens cytokine production, weakening immune control and allowing broader viral spread.

Characterization of infection progression.

In the idealized scenario , activated macrophages persist indefinitely, and the system simplifies. Considering travelling wave of infection spreading, we derived an explicit nonlinear equation for the fraction of surviving uninfected cells . This equation links to the total viral load and wave speed c. It provides a necessary condition for the infection spreading in the tissue in the form of travelling wave.

Solvability of this equation provides an important characterization of the progression of viral infection. It is determined by the virus replication number

R expressed through the parameters of the model. In the case without macrophages (

) or if they do not eliminate infected cells and free virions (

), the virus replication number introduced in this work coincides with the virus replication number

considered in [

4] for infection spreading in cell cultures without immune response. As it was shown in this previous work, viral infection spreads in cell culture if

and extincts otherwise. Solvability condition of this equation in the case of immune response provided by circulating macrophages is given by the inequality

, where

is a positive parameter determined by the coefficients of the model. Hence, the region in the parameter space corresponding to infection progression shrinks due to the immune response while the region of infection elimination increases.

It should be noted, however, that condition is a necessary condition for the solvability of this equation but not sufficient. It appears that in some parameter range, it can be solvable in a narrow interval . Moreover, there are two solutions of this equation satisfying . We can expect that there are two waves exist in this case, one of them stable and another one unstable, and that initial conditions should be sufficiently large to provide convergence to the stable wave versus extinction of the infection and convergence to zero. This conjecture is not yet confirmed by direct numerical simulations since the parameter range of possible bistability is narrow, and the choice of initial conditions should be very precise.

Besides solvability of equation for , we determine the wave speed by the linearization method. The minimal wave speed is positive if , where P is the strength of the immune response. This parameter is expressed through the coefficients of the model and through the viral load. The latter satisfies a transcendental system of equation (together with the wave speed), and it does not admit a simple analytical expression, but it can be approximated by the method of successive approximation. Note that, depending on parameters, we can have or .

These three parameters, and P determine regimes of infection progression. If and , then infection spreads as a travelling wave, while if both inequalities are opposite, it extincts. Though analytical results give only necessary conditions of infection spreading, these conclusions are confirmed by direct numerical simulations.

An interesting question is whether it is possible to have only one of these conditions satisfied. In this case, we can expect that infection starts its progression but gradually extincts, as it was previously observed in the model with resident macrophages [

22]. In numerical simulations of the actual model, we could not yet find this regime of infection spreading.

One more regime corresponds to transient infection spreading and its gradual extinction. Since initially there are no activated macrophages (

), then infection propagates if

. However, since the concentration of macrophages grows with time, then the viral load decreases. In the case

, which is possible since

, infection is gradually eliminated by the innate immune response (

Figure 3).

If , the model becomes more difficult to analyze. We determine the virus replication number and sufficient conditions of solvability of equation for . We conclude that higher values of facilitate infection progression. This conclusion is confirmed by direct numerical simulations which show that the infection front propagates more rapidly and reaches higher viral burdens.

Biological impliciations and model limitations.

The results of the work corroborate biological data about the role of macrophages in the development of viral infections. During respiratory viral infections, circulating monocytes are rapidly recruited into the lungs, where they differentiate into macrophages that participate in viral clearance. These macrophages lower viral load through multiple mechanisms: direct phagocytosis of viral particles and infected epithelial cells, production of antiviral mediators such as nitric oxide and type I interferons, and enhancement of adaptive immunity by presenting viral antigens to T lymphocytes. Experimental studies in influenza virus infection demonstrate that depletion of circulating or alveolar macrophages results in higher viral titers and worsened pathology, while their activation promotes faster viral clearance and improved survival [

15,

29].

These findings emphasize the dual role of macrophage regulation: while necessary to avoid overactivation and tissue damage, excessive degradation may impair viral containment, especially in early infection [

17,

18]. Our results underscore a fundamental trade-off in immune dynamics: persistent activation of macrophages is beneficial for rapid viral control, but requires tight regulation to avoid immunopathology. Conversely, premature degradation of effector cells facilitates viral spread. This suggests that therapeutic strategies enhancing macrophage stability—or delaying their exhaustion—could improve immune effectiveness in early infection phases. Excessive immune suppression might unintentionally promote viral persistence.

Immune response to viral infection is a very complex biological processes, and the models of immune response encounter necessarily essential simplifications. In this work we consider only circulating macrophages, as one of the most important actor of the innate immune response. Resident macrophages were considered on [

22], and adaptive immune response was considered in [

27]. Bringing together these different parts of the immune response will require further investigations.

Conclusions.

By integrating spatial dynamics and immune feedback, our model highlights the central role of macrophage-mediated responses in shaping infection spread. The analytical and numerical results illustrate how spatially distributed infections can be contained or amplified depending on macrophage turnover and cytokine signaling strength. Future extensions may include adaptive immunity, tissue heterogeneity, and stochastic effects to further refine the understanding of immune-virus interplay.

Figure 2.

Graphical solution of equation (3.9) with function (solid line) and , where (dotted line) and (dashed line). There is one solution for the former and two solutions for the latter. The values of parameters: , (dashed line), (dotted line).

Figure 2.

Graphical solution of equation (3.9) with function (solid line) and , where (dotted line) and (dashed line). There is one solution for the former and two solutions for the latter. The values of parameters: , (dashed line), (dotted line).

Figure 3.

Numerical simulations of system (2.1)-(2.5): concentration of uninfected cells , infected cells , virus as function of x in consecutive moments of time , and inflammatory cytokines as function of t. Values of parameters: , , , , , , , ,, , , , cm, (copy/mL), (cell/ml), , , , , , ,

Figure 3.

Numerical simulations of system (2.1)-(2.5): concentration of uninfected cells , infected cells , virus as function of x in consecutive moments of time , and inflammatory cytokines as function of t. Values of parameters: , , , , , , , ,, , , , cm, (copy/mL), (cell/ml), , , , , , ,

Figure 4.

Numerical simulations of system (2.1)-(2.5): concentration of uninfected cells , infected cells , virus as function of x in consecutive moments of time and inflammatory cytokines as function of t. Values of parameters: , , , , , , , ,, , , , cm, (copy/mL), (cell/ml), , , , , , ,

Figure 4.

Numerical simulations of system (2.1)-(2.5): concentration of uninfected cells , infected cells , virus as function of x in consecutive moments of time and inflammatory cytokines as function of t. Values of parameters: , , , , , , , ,, , , , cm, (copy/mL), (cell/ml), , , , , , ,

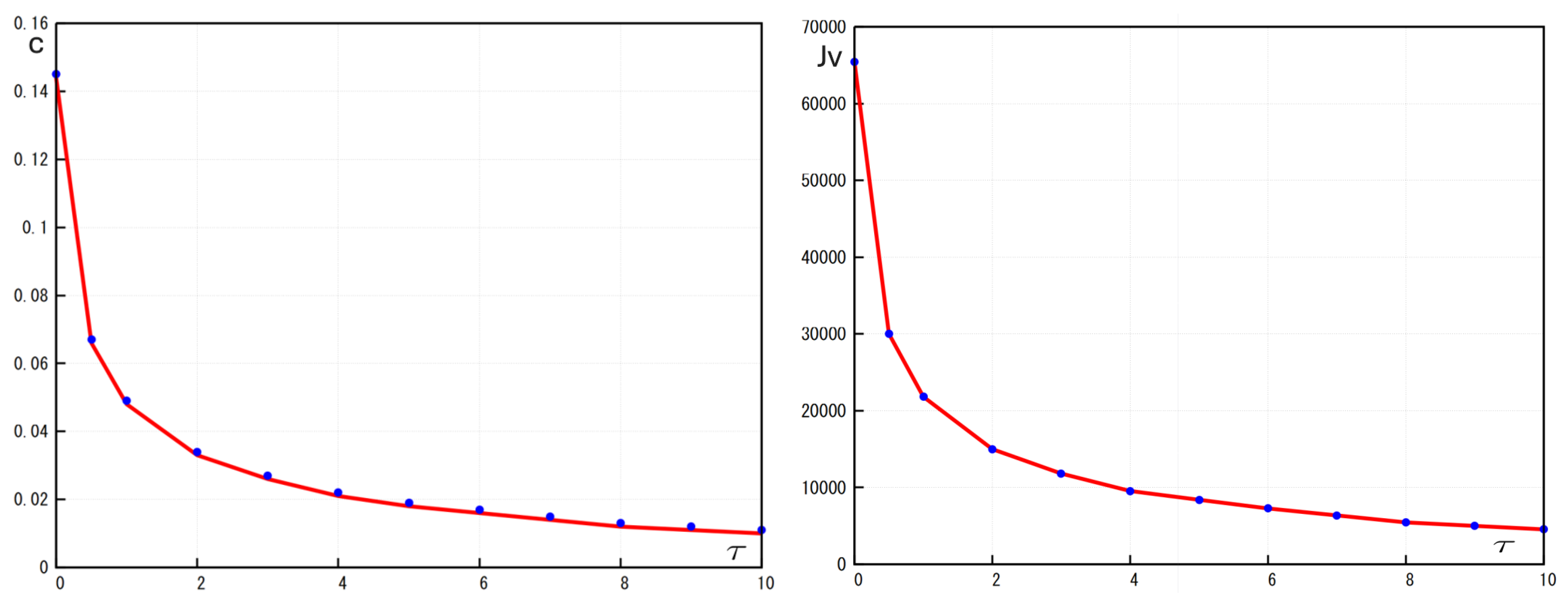

Figure 5.

Left: Comparison of the numerical values (blue dots) and analytic values (red lines) of the wave speed c in function of the times delay . Right: Comparison of the numerical values (blue dots) and analytic values (red lines) of the viral load in function of the times delay Values of parameters: , , , , , , , ,, , , , cm, (copy/mL), (cell/ml), , , , , ,

Figure 5.

Left: Comparison of the numerical values (blue dots) and analytic values (red lines) of the wave speed c in function of the times delay . Right: Comparison of the numerical values (blue dots) and analytic values (red lines) of the viral load in function of the times delay Values of parameters: , , , , , , , ,, , , , cm, (copy/mL), (cell/ml), , , , , ,

Figure 6.

Left: the wave speed c as a function of where the red curve represents the case and blue curve represents the case . Right: the viral load as a function of where the red curve represents the case and blue curve represents the case Values of parameters: , ,, , , ,, , , , cm, (copy/mL), (cell/ml), , , , , , ,

Figure 6.

Left: the wave speed c as a function of where the red curve represents the case and blue curve represents the case . Right: the viral load as a function of where the red curve represents the case and blue curve represents the case Values of parameters: , ,, , , ,, , , , cm, (copy/mL), (cell/ml), , , , , , ,