Submitted:

20 June 2025

Posted:

23 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

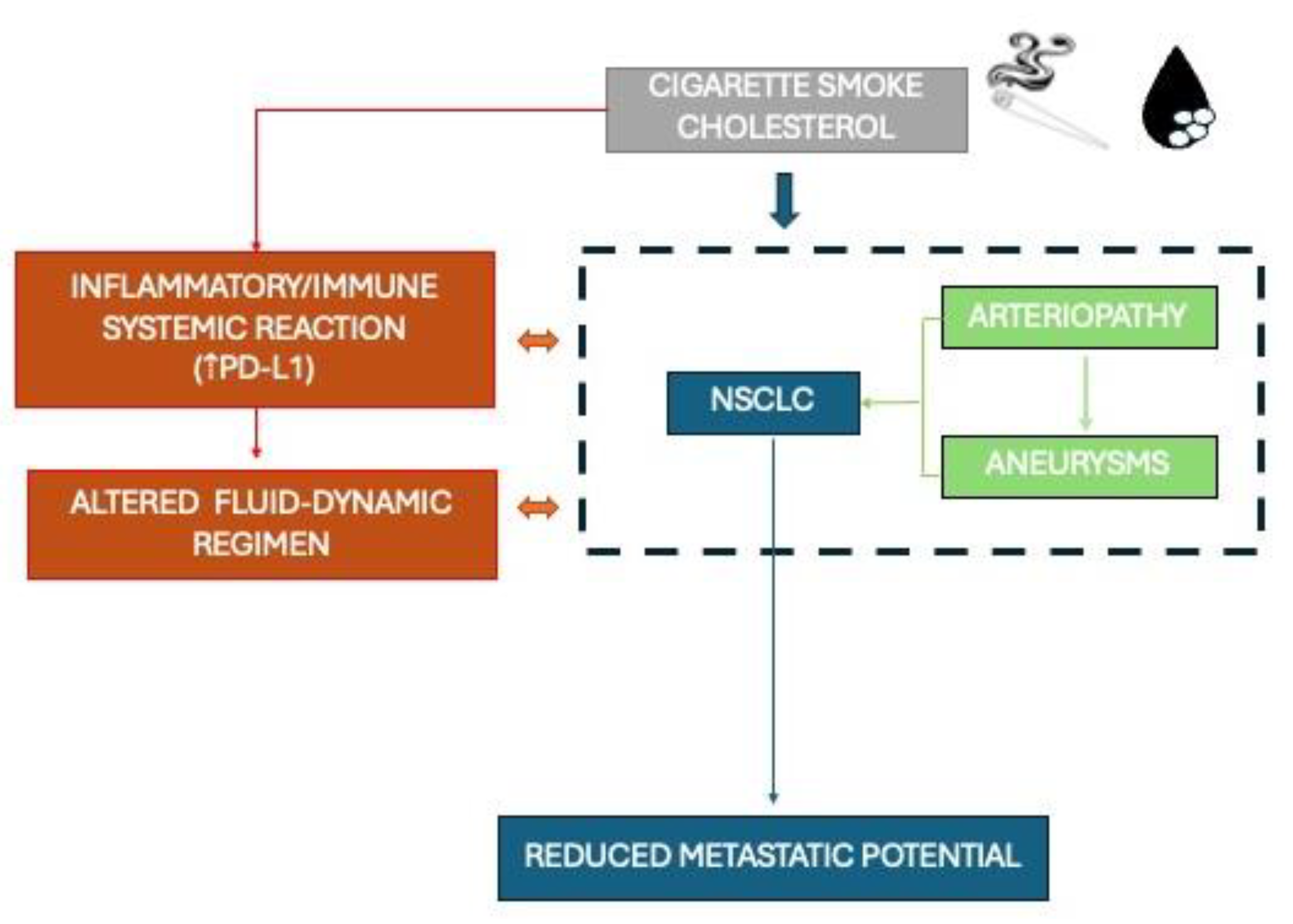

1.1. Biologic Hints in Lung Cancer Distant Spreading

1.2. Vascular Pathophysiology

1.3. The Interplay Between Smoke, Cholesterol, Cancer and Vessels

2. Methods

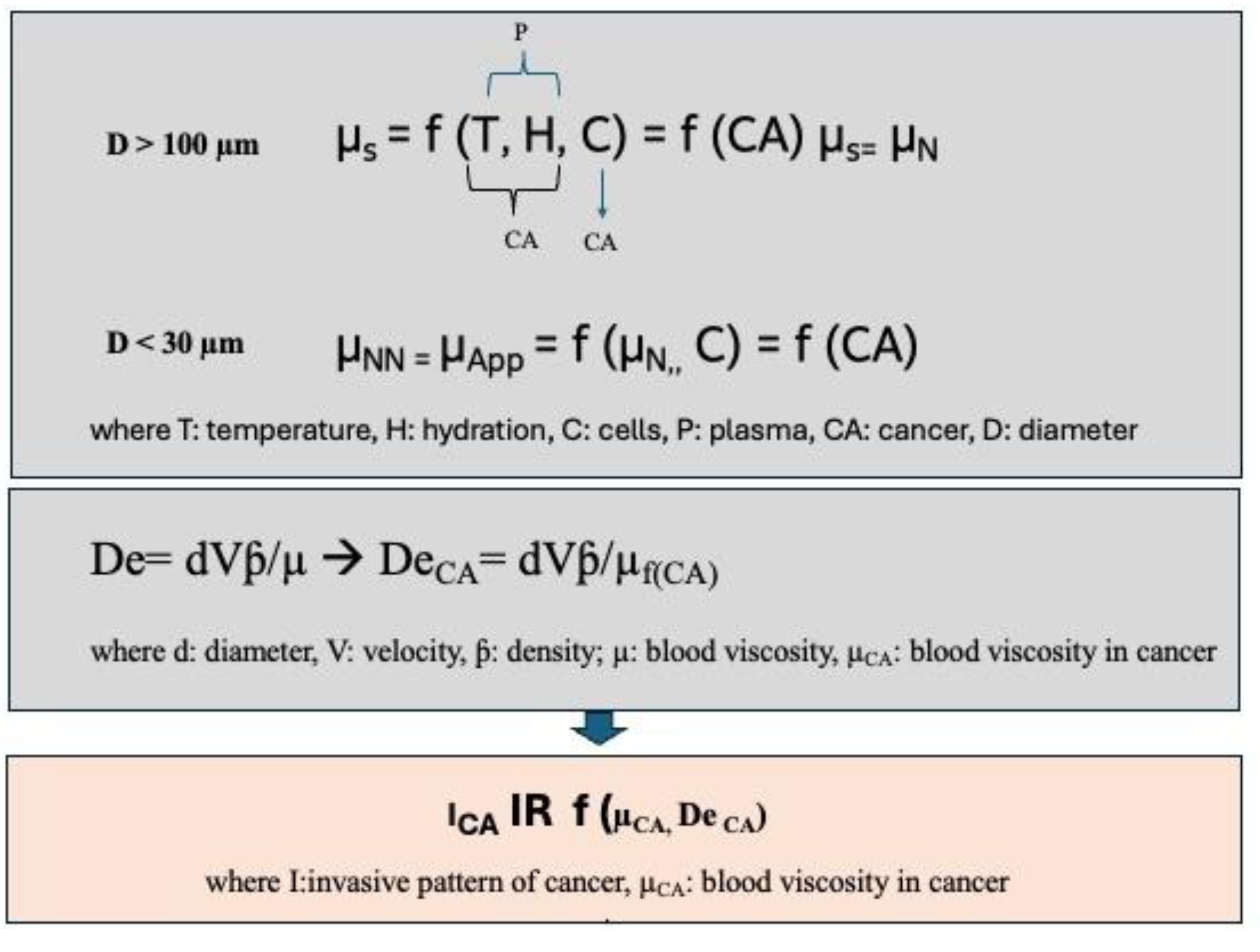

2.1. Modelling

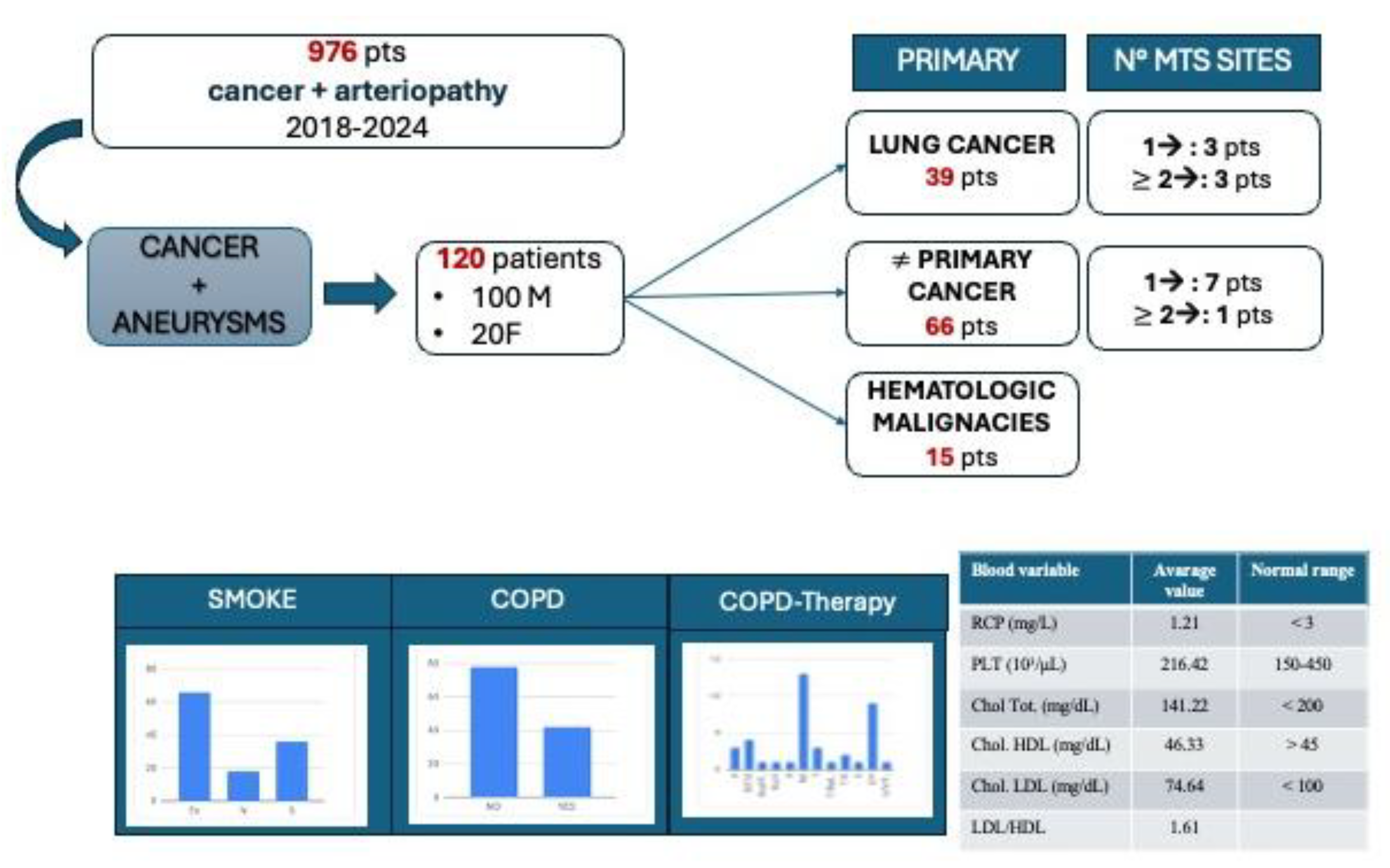

2.2. Patients Identification and Selection

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Definition of a Mathematical Model

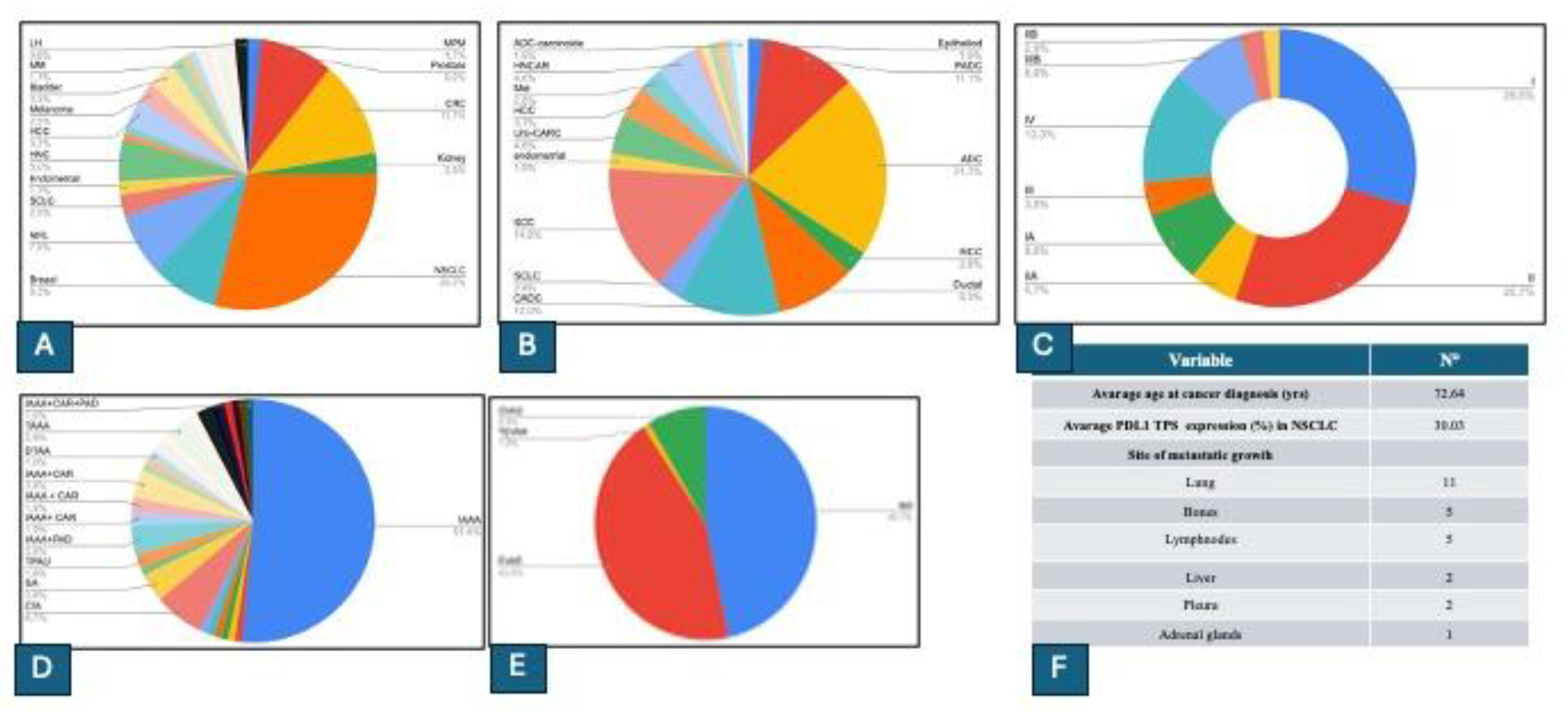

3.2. Population Characteristics and Clinical Analysis

3.3. Results from Partition Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Support Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xie S, Wu Z, Qi Y, Wu B, Zhu X. The metastasizing mechanisms of lung cancer: Recent advances and therapeutic challenges. Biomed Pharmacother. 2021, 138, 111450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel RL, Giaquinto AN, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J Clin 2024, 74, 12–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thai AA, Solomon BJ, Sequist LV, Gainor JF, Heist RS. Lung cancer. Lancet. 2021, 398, 535–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie T, Qiu BM, Luo J, Diao YF, Hu LW, Liu XL, Shen Y. Distant metastasis patterns among lung cancer subtypes and impact of primary tumor resection on survival in metastatic lung cancer using SEER database. Sci Rep. 2024, 14, 22445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu F, Chen Z, Chen H. Treating lung cancer: defining surgical curative time window. Cell Res. 2023, 33, 649–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La’ah AS, Chiou SH. Cutting-Edge Therapies for Lung Cancer. Cells. 2024, 13, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin SD, Tong CY, Huang DD, Rossi A, Adachi H, Miao M, Zheng WX, Guo J. The time-to-surgery interval and its effect on pathological response after neoadjuvant chemoimmunotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer: a retrospective cohort study. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2024, 13, 2761–2772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stella GM, Kolling S, Benvenuti S, Bortolotto C. Lung-Seeking Metastases. Cancers (Basel). 2019, 11, 1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundin A, Driscoll B. Lung cancer stem cells: progress and prospects. Cancer Lett. 2013, 338, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu X, Tian W, Ning J, Xiao G, Zhou Y, Wang Z, Zhai Z, Tanzhu G, Yang J, Zhou R. Cancer stem cells: advances in knowledge and implications for cancer therapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024, 9, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou Q, Zu L, Li L, Chen X, Chen X, Li Y, Liu H, Sun Z. [Screening and establishment of human lung cancer cell lines with organ-specific metastasis potential]. Zhongguo Fei Ai Za Zhi. 2014, 17, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen DX, Massagué J. Genetic determinants of cancer metastasis. Nat Rev Genet. 2007, 8, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel SA, Rodrigues P, Wesolowski L, Vanharanta S. Genomic control of metastasis. Br J Cancer. 2021, 124, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fares J, Fares MY, Khachfe HH, Salhab HA, Fares Y. Molecular principles of metastasis: a hallmark of cancer revisited. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2020, 5, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lusby R, Demirdizen E, Inayatullah M, Kundu P, Maiques O, Zhang Z, Terp MG, Sanz-Moreno V, Tiwari VK. Pan-cancer drivers of metastasis. Mol Cancer. 2025, 24, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo B, Li D, Du L, Zhu X. piRNAs: biogenesis and their potential roles in cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2020, 39, 567–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie S, Wu Z, Qi Y, Wu B, Zhu X. The metastasizing mechanisms of lung cancer: Recent advances and therapeutic challenges. Biomed Pharmacother. 2021, 138, 111450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minervini G, Pennuto M, Tosatto SCE. The pVHL neglected functions, a tale of hypoxia-dependent and -independent regulations in cancer. Open Biol. 2020, 10, 200109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godet I, Shin YJ, Ju JA, Ye IC, Wang G, Gilkes DM. Fate-mapping post-hypoxic tumor cells reveals a ROS-resistant phenotype that promotes metastasis. Nat Commun. 2019, 10, 4862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang C, Zhang N, Hu X, Wang H. Tumor-associated exosomes promote lung cancer metastasis through multiple mechanisms. Mol Cancer. 2021, 20, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieu M, Martin-Jaular L, Lavieu G, Théry C. Specificities of secretion and uptake of exosomes and other extracellular vesicles for cell-to-cell communication. Nat Cell Biol. 2019, 21, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang L, Cao L, Wang H, Liu B, Zhang Q, Meng Z, Wu X, Zhou Q, Xu K. Cancer-associated fibroblasts enhance metastatic potential of lung cancer cells through IL-6/STAT3 signaling pathway. Oncotarget. 2017, 8, 76116–76128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li R, Ong SL, Tran LM, Jing Z, Liu B, Park SJ, Huang ZL, Walser TC, Heinrich EL, Lee G, Salehi-Rad R, Crosson WP, Pagano PC, Paul MK, Xu S, Herschman H, Krysan K, Dubinett S. Chronic IL-1β-induced inflammation regulates epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition memory phenotypes via epigenetic modifications in non-small cell lung cancer. Sci Rep. 2020, 10, 377, Erratum in: Sci Rep. 2020 Mar 4;10(1):4386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan J, Xu G, Chang Z, Zhu L, Yao J. miR-210 transferred by lung cancer cell-derived exosomes may act as proangiogenic factor in cancer-associated fibroblasts by modulating JAK2/STAT3 pathway. Clin Sci (Lond). 2020, 134, 807–825, . Erratum in: Clin Sci (Lond). 2020, 134, 1801-1804. 10.1042/CS-20200039_COR. [CrossRef]

- Guo X, Zhu X, Zhao L, Li X, Cheng D, Feng K. Tumor-associated calcium signal transducer 2 regulates neovascularization of non-small-cell lung cancer via activating ERK1/2 signaling pathway. Tumour Biol. 2017, 39, 1010428317694324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaxton C, Kano M, Mendes-Pinto D, Navarro TP, Nishibe T, Dardik A. Implications of preoperative arterial stiffness for patients treated with endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms. JVS Vasc Sci. 2024, 5, 100209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa D, Andreucci M, Ielapi N, Serraino GF, Mastroroberto P, Bracale UM, Serra R. Vascular Biology of Arterial Aneurysms. Ann Vasc Surg. 2023, 94, 378–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vermeulen JJM, Meijer M, de Vries FBG, Reijnen MMPJ, Holewijn S, Thijssen DHJ. A systematic review summarizing local vascular characteristics of aneurysm wall to predict for progression and rupture risk of abdominal aortic aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2023, 77, 288–298.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2023, 8, 55. 8. [CrossRef]

- Thaxton C, Kano M, Mendes-Pinto D, Navarro TP, Nishibe T, Dardik A. Implications of preoperative arterial stiffness for patients treated with endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms. JVS Vasc Sci. 2024, 5, 100209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danaei G, Vander Hoorn S, Lopez AD, Murray CJ, Ezzati M. Causes of cancer in the world: comparative risk assessment of nine behavioural and environmental risk factors. Lancet 2005, 366, 1784–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crispo A, Brennan P, Jöckel KH, Schaffrath-Rosario A, Wichmann HE, Nyberg F, Simonato L, Merletti F, Forastiere F, Boffetta P, Darby S. The cumulative risk of lung cancer among current, ex- and never-smokers in European men. Br J Cancer. 2004, 91, 1280–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asomaning K, Miller DP, Liu G, Wain JC, Lynch TJ, Su L, Christiani DC. Second hand smoke, age of exposure and lung cancer risk. Lung Cancer. 2008, 61, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorthy B, Chu C, Carlin DJ. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: from metabolism to lung cancer. Toxicol Sci. 2015, 145, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- oldman R, Enewold L, Pellizzari E, Beach JB, Bowman ED, Krishnan SS, Shields PG. Smoking increases carcinogenic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in human lung tissue. Cancer Res. 2001, 61, 6367–6371. [Google Scholar]

- Martey CA, Baglole CJ, Gasiewicz TA, Sime PJ, Phipps RP. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor is a regulator of cigarette smoke induction of the cyclooxygenase and prostaglandin pathways in human lung fibroblasts. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005, 289, L391–L399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dasgupta P, Rizwani W, Pillai S, Kinkade R, Kovacs M, Rastogi S, Banerjee S, Carless M, Kim E, Coppola D, Haura E, Chellappan S. Nicotine induces cell proliferation, invasion and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in a variety of human cancer cell lines. Int J Cancer. 2009, 124, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindholt J, Jorgensen B, Shi G-P, Henneberg EW. Relationships between activators and inhibitors of plasminogen, and the progression of small abdominal aortic aneurysms. Eur J Vasc Endovas Surg. 2003, 25, 546–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna SM, Dear AE, Norman PE, Golledge J. Genetic and epigenetic mechanisms and their possible role in abdominal aortic aneurysm. Atherosclerosis. 2010, 212, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee AJ, Fowkes FG, Carson MN, Leng GC, Allan PL. Smoking, atherosclerosis and risk of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Eur Heart J. 1997, 18, 671–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng Z, Qiu P, Guo H, Zhu C, Zheng J, Pu H, Liu Y, Wei W, Li C, Yang X, Ye K, Wang R, Lu X, Zhou Z. Association between high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and risk of abdominal aortic aneurysm among males and females aged 60 years and over. J Vasc Surg. 2025, 81, 894–904.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbs SD, Claridge MW, Quick CR, Day NE, Bradbury AW, Wilmink AB. LDL cholesterol is associated with small abdominal aortic aneurysms. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2003, 26, 618–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng LC, Roetker NS, Lutsey PL, Alonso A, Guan W, Pankow JS, Folsom AR, Steffen LM, Pankratz N, Tang W. Evaluation of the relationship between plasma lipids and abdominal aortic aneurysm: A Mendelian randomization study. PLoS One. 2018, 13, e0195719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun P, Zhang L, Gu Y, Wei S, Wang Z, Li M, Wang W, Wang Z, Bai H. Immune checkpoint programmed death-1 mediates abdominal aortic aneurysm and pseudoaneurysm progression. Biomed Pharmacother. 2021, 142, 111955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai H, Wang Z, Li M, Sun P, Wei S, Wang W, Wang Z, Xing Y, Li J, Dardik A. Inhibition of programmed death-1 decreases neointimal hyperplasia after patch angioplasty. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2021, 109, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun P, Zhang L, Gu Y, Wei S, Wang Z, Li M, Wang W, Wang Z, Bai H. Immune checkpoint programmed death-1 mediates abdominal aortic aneurysm and pseudoaneurysm progression. Biomed Pharmacother. 2021, 142, 111955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Márquez-Sánchez AC, Koltsova EK. Immune and inflammatory mechanisms of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Front Immunol. 2022, 13, 989933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Arienzo MP, Rarità L. Dynamics of Blood Flows in the Cardiocirculatory System. Computation. 2024, 12, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Numata S, Itatani K, Kanda K, Doi K, Yamazaki S, Morimoto K, Manabe K, Ikemoto K, Yaku H. Blood flow analysis of the aortic arch using computational fluid dynamics. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2016, 49, 1578–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch S, Nama N, Figueroa CA. Effects of non-Newtonian viscosity on arterial and venous flow and transport. Sci Rep. 2022, 12, 20568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han JW, Sung PS, Jang JW, Choi JY, Yoon SK. Whole blood viscosity is associated with extrahepatic metastases and survival in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. PLoS One. 2021, 16, e0260311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M. M. , Puniyani, R. R., Huilgol, N. G., Hussain, M. A., & Ranade, G. G. Hemorheological profiles in cancer patients. Clinical Hemorheology and Microcirculation 1995, 15, 37–44. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, De-en, Jing-chao Ruan, and Pei-qing Wang. “Hemorheological changes in cancer.” Clinical Hemorheology and Microcirculation 8.6 (1988): 945-956.

- Dintenfass, L. Haemorheology of cancer metastases: An example of malignant melanoma. Survival times and abnormality of blood viscosity factors 1. Clin Hemorheol Micro. 1982, 2, 259–271. [Google Scholar]

- Wirtz D, Konstantopoulos K, Searson PC. The physics of cancer: the role of physical interactions and mechanical forces in metastasis. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2011, 11, 512–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Follain G, Herrmann D, Harlepp S, Hyenne V, Osmani N, Warren SC, et al. Fluids and their mechanics in tumour transit: shaping metastasis. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2020, 20, 107–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Tempelhoff GF, Heilmann L, Hommel G, Pollow K. Impact of rheological variables in cancer. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2003, 29, 499–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helwa R, Heller A, Knappskog S, Bauer AS. Tumor cells interact with red blood cells via galectin-4 - a short report. Cell Oncol (Dordr). 2017, 40, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiewiora M, Jopek J, Świętochowska E, Sławomir G, Piecuch J, Gąska M, Piecuch J. Blood-based protein biomarkers and red blood cell aggregation in pancreatic cancer. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2023, 85, 371–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Tempelhoff GF, Nieman F, Heilmann L, Hommel G. Association between blood rheology, thrombosis and cancer survival in patients with gynecologic malignancy. Clin Hemorheol Micro. 2000, 22, 107–130. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Font-Clos F, Zapperi S, La Porta CAM. Blood Flow Contributions to Cancer Metastasis. iScience. 2020, 23, 101073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancer cells move and spread faster in thicker extracellular fluids. Nature. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Bera K, Kiepas A, Godet I, Li Y, Mehta P, Ifemembi B, Paul CD, Sen A, Serra SA, Stoletov K, Tao J, Shatkin G, Lee SJ, Zhang Y, Boen A, Mistriotis P, Gilkes DM, Lewis JD, Fan CM, Feinberg AP, Valverde MA, Sun SX, Konstantopoulos K. Extracellular fluid viscosity enhances cell migration and cancer dissemination. Nature. 2022, 611, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccaccio C, Comoglio PM. Genetic link between cancer and thrombosis. J Clin Oncol. 2009, 27, 4827–4833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccaccio C, Sabatino G, Medico E, Girolami F, Follenzi A, Reato G, Sottile A, Naldini L, Comoglio PM. The MET oncogene drives a genetic programme linking cancer to haemostasis. Nature. 2005, 434, 396–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li R, Ren M, Chen N, Luo M, Deng X, Xia J, Yu G, Liu J, He B, Zhang X, Zhang Z, Zhang X, Ran B, Wu J. Presence of intratumoral platelets is associated with tumor vessel structure and metastasis. BMC Cancer. 2014, 14, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stella GM, Benvenuti S, Gentile A, Comoglio PM. MET Activation and Physical Dynamics of the Metastatic Process: The Paradigm of Cancers of Unknown Primary Origin. EBioMedicine. 2017, 24, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldana M, Gallegos S, Gálvez E, Castillo J, Salinas-Rodríguez E, Cerecedo-Sáenz E, Hernández-Ávila J, Navarra A, Toro N. The Reynolds Number: A Journey from Its Origin to Modern Applications. Fluids. 2024, 9, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coclite A, Coclite GM, De Tommasi D. Capsules Rheology in Carreau-Yasuda Fluids. Nanomaterials (Basel). 2020, 10, 2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen J, Lu XY. Numerical investigation of the non-Newtonian pulsatile blood flow in a bifurcation model with a non-planar branch. J Biomech. 2006, 39, 818–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang QQ, Ping BH, Xu QB, Wang W. Rheological effects of blood in a nonplanar distal end-to-side anastomosis. J Biomech Eng. 2008, 130, 051009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bera K, Kiepas A, Godet I, Li Y, Mehta P, Ifemembi B, Paul CD, Sen A, Serra SA, Stoletov K, Tao J, Shatkin G, Lee SJ, Zhang Y, Boen A, Mistriotis P, Gilkes DM, Lewis JD, Fan CM, Feinberg AP, Valverde MA, Sun SX, Konstantopoulos K. Extracellular fluid viscosity enhances cell migration and cancer dissemination. Nature. 2022, 611, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomaa A, Gamal Y, Abdelmagied MM. Enhancement of thermofluid characteristics via a triple-helical tube heat exchanger. Sci Rep. 2025, 15, 6978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajah G, Narayanan S, Rangel-Castilla L. Update on flow diverters for the endovascular management of cerebral aneurysms. Neurosurg Focus. 2017, E2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao DL, Tassi Yunga S, Williams CD, McCarty OJT. Aspirin and antiplatelet treatments in cancer. Blood. 2021, 137, 3201–3211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang X, Zhao S, Wang Z, Gao T. Platelets involved tumor cell EMT during circulation: communications and interventions. Cell Commun Signal. 2022, 20, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares V, Savva-Bordalo J, Rei M, Liz-Pimenta J, Assis J, Pereira D, Medeiros R. Haemostatic Gene Expression in Cancer-Related Immunothrombosis: Contribution for Venous Thromboembolism and Ovarian Tumour Behaviour. Cancers (Basel). 2024, 16, 2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Leon MJ, Liboni C, Mittelheisser V, Bochler L, Follain G, Mouriaux C, Busnelli I, Larnicol A, Colin F, Peralta M, Osmani N, Gensbittel V, Bourdon C, Samaniego R, Pichot A, Paul N, Molitor A, Carapito R, Jandrot-Perrus M, Lefebvre O, Mangin PH, Goetz JG. Platelets favor the outgrowth of established metastases. Nat Commun. 2024, 15, 3297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potempa LA, Rajab IM, Olson ME, Hart PC. C-Reactive Protein and Cancer: Interpreting the Differential Bioactivities of Its Pentameric and Monomeric, Modified Isoforms. Front Immunol. 2021, 12, 744129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart PC, Rajab IM, Alebraheem M, Potempa LA. C-Reactive Protein and Cancer-Diagnostic and Therapeutic Insights. Front Immunol. 2020, 11, 595835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun T, Chen M, Shen H, PingYin, Fan L, Chen X, Wu J, Xu Z, Zhang J. Predictive value of LDL/HDL ratio in coronary atherosclerotic heart disease. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2022, 22, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).