Submitted:

24 September 2025

Posted:

25 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Population of the Study

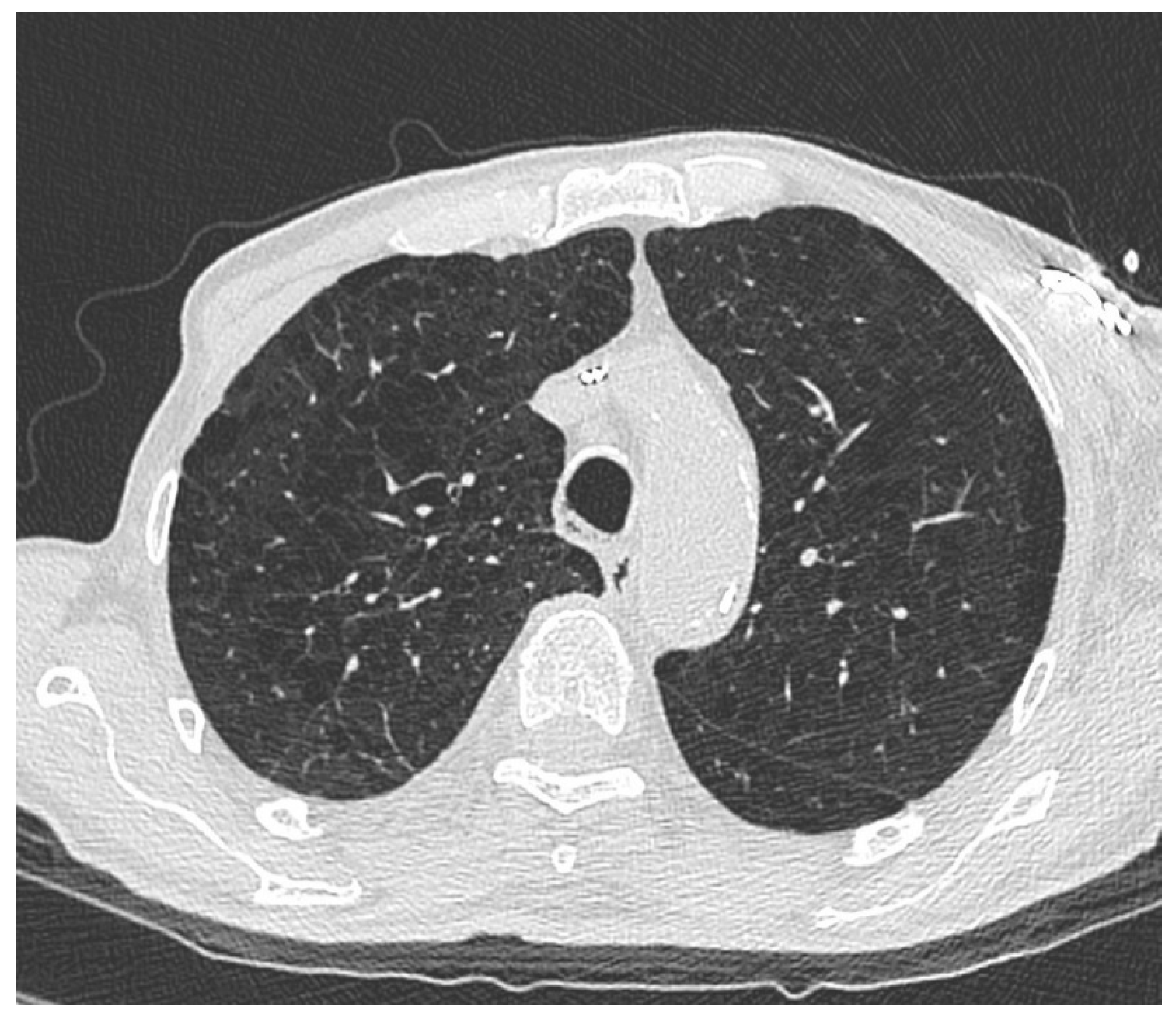

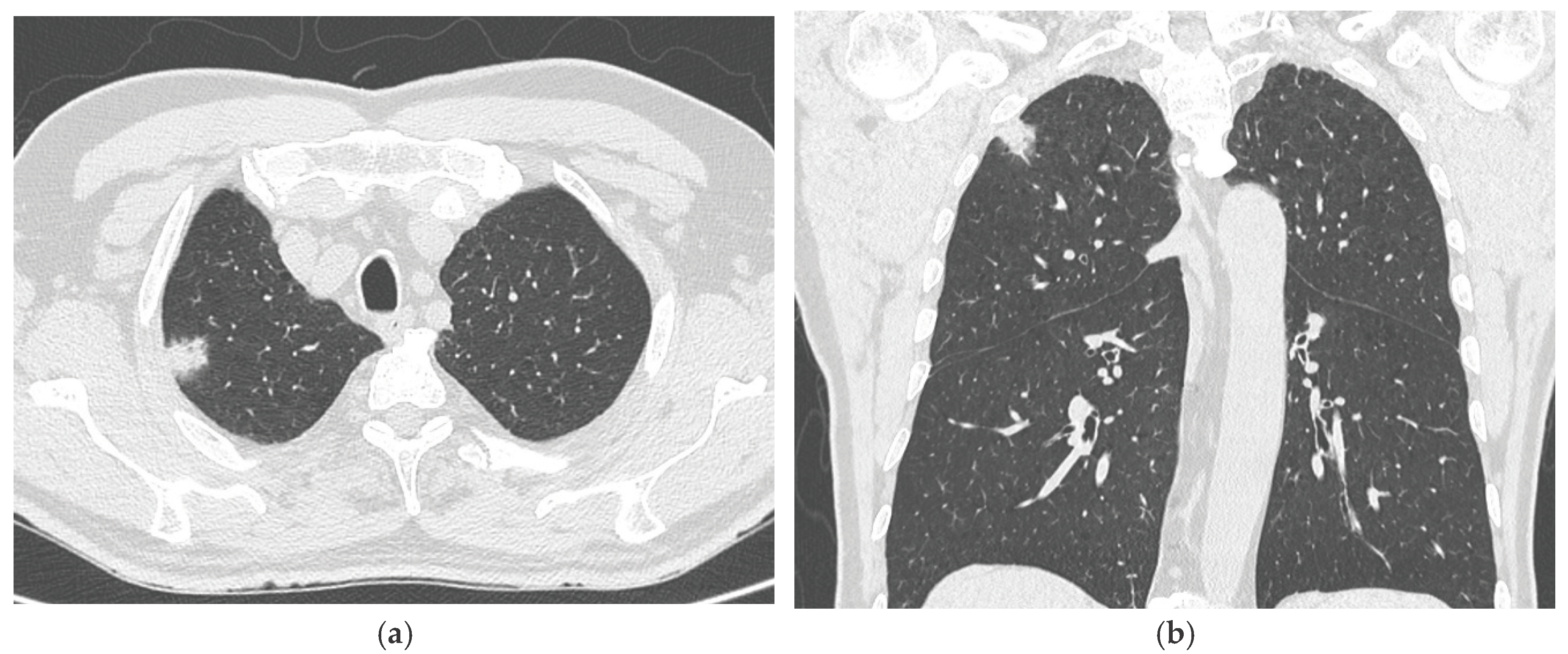

2.2. Imaging Analysis

2.3. Statistical Analysis

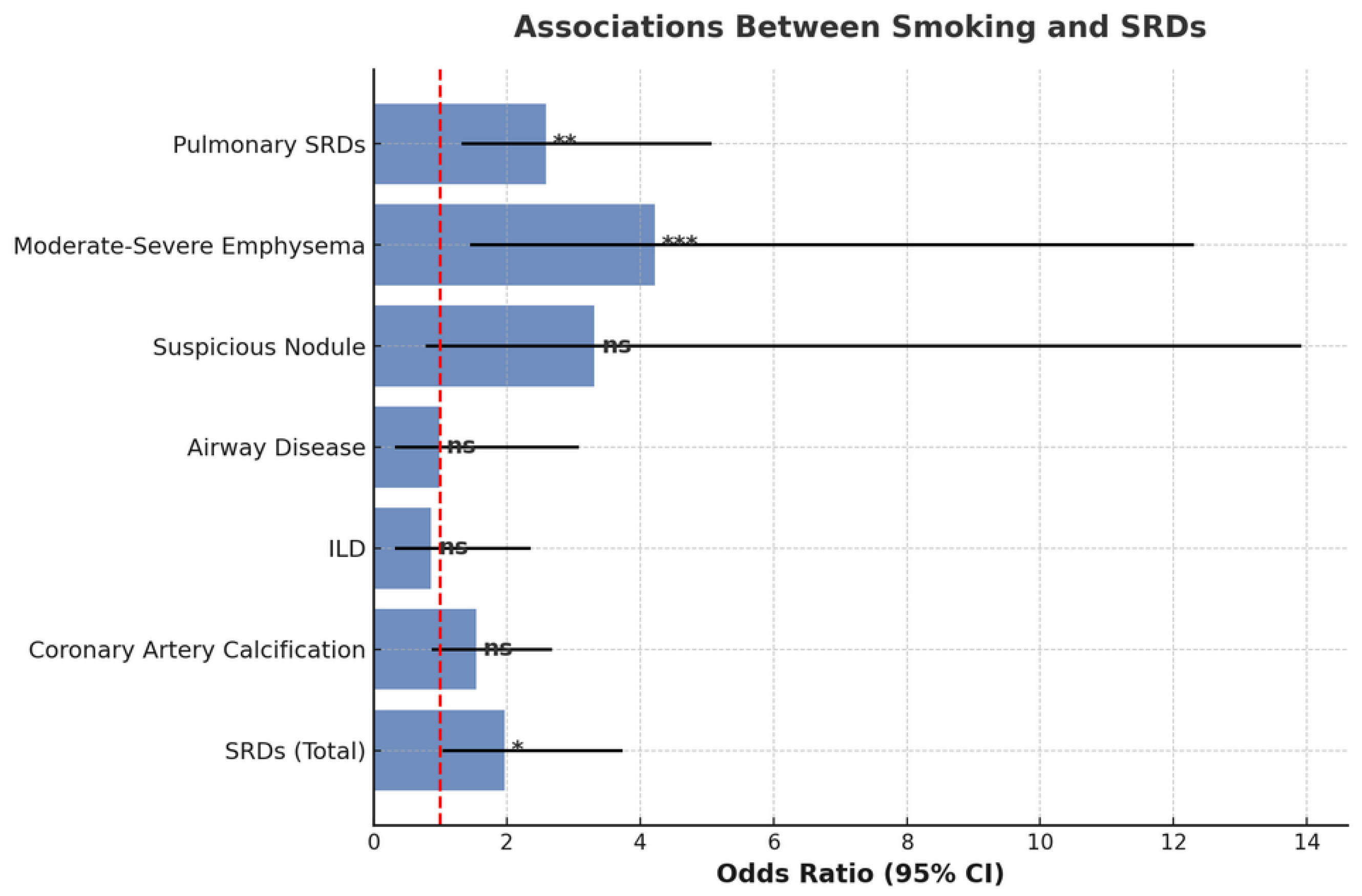

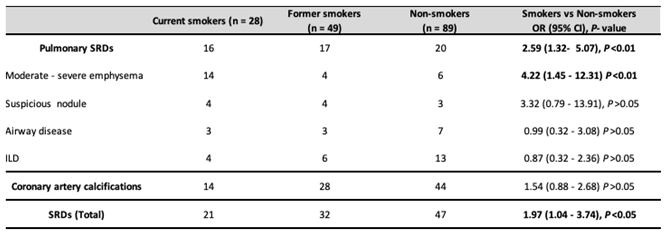

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BC | Bladder Carcinoma |

| CAC | Coronary Artery Calcifications |

| CIS | Carcinoma In Situ |

| EAU | European Association of Urology |

| HGBC | High-Grade Bladder Carcinoma |

| HRCT | High-Resolution Computed Tomography |

| ILD | Interstitial Lung Disease |

| LC | Lung Cancer |

| LGBC | Low-Grade Bladder Carcinoma |

| MIBC | Muscle-Invasive Bladder Carcinoma |

| NMIBC | Non-Muscle-Invasive Bladder Carcinoma |

| p-SRD | Smoking-Related pulmonary Disease |

| SRD | Smoking Related Disease |

| TURB | Transurethral Resection of the Bladder |

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA A Cancer J Clinicians 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larkins, M.C.; Pasli, M.; Bhatt, A.; Burke, A. Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the bladder: Demographics and Outcomes associated with Surgery and Radiotherapy. Journal of Surgical Oncology 2024, 129, 649–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, K.; Abufaraj, M.; Mostafaei, H.; Quhal, F.; Karakiewicz, P.I.; Briganti, A.; Kimura, S.; Egawa, S.; Shariat, S.F. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Variant Histology in Urothelial Carcinoma of the Bladder Treated with Radical Cystectomy. Journal of Urology 2020, 204, 1129–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, A.C.; Gu, J.Z.; Koo, B.H.; Fruh, V.; Sax, A.J. Urothelial Carcinoma: Epidemiology and Imaging-Based Review. R I Med J (2013) 2024, 107, 26–32. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, W.S.; Sarpong, R.; Khetrapal, P.; Rodney, S.; Mostafid, H.; Cresswell, J.; Hicks, J.; Rane, A.; Henderson, A.; Watson, D.; et al. Can Renal and Bladder Ultrasound Replace Computerized Tomography Urogram in Patients Investigated for Microscopic Hematuria? Journal of Urology 2018, 200, 973–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yafi, F.A.; Brimo, F.; Steinberg, J.; Aprikian, A.G.; Tanguay, S.; Kassouf, W. Prospective Analysis of Sensitivity and Specificity of Urinary Cytology and Other Urinary Biomarkers for Bladder Cancer. Urologic Oncology: Seminars and Original Investigations 2015, 33, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Compérat, E.; Amin, M.B.; Berney, D.M.; Cree, I.; Menon, S.; Moch, H.; Netto, G.J.; Rao, V.; Raspollini, M.R.; Rubin, M.A.; et al. What’s New in WHO Fifth Edition – Urinary Tract. Histopathology 2022, 81, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong, J.J.; Lotan, Y.; Boormans, J.L. Re: EAU Guidelines on Muscle-Invasive and Metastatic Bladder Cancer. European Urology 2024, 86, 480–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babjuk, M.; Burger, M.; Capoun, O.; Cohen, D.; Compérat, E.M.; Dominguez Escrig, J.L.; Gontero, P.; Liedberg, F.; Masson-Lecomte, A.; Mostafid, A.H.; et al. European Association of Urology Guidelines on Non–Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer (Ta, T1, and Carcinoma in Situ). European Urology 2022, 81, 75–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minami, T.; Fujita, K.; Hashimoto, M.; Nishimoto, M.; Adomi, S.; Banno, E.; Nozawa, M.; Nose, K.; Yoshimura, K.; Inada, M.; et al. External Beam Radiotherapy Combination Is a Risk Factor for Bladder Cancer in Patients with Prostate Cancer Treated with Brachytherapy. World J Urol 2023, 41, 1317–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayne, C.E.; Farah, D.; Herbst, K.W.; Hsieh, M.H. Role of Urinary Tract Infection in Bladder Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. World J Urol 2018, 36, 1181–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedman, N.D. Association Between Smoking and Risk of Bladder Cancer Among Men and Women. JAMA 2011, 306, 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christenson, S.A.; Smith, B.M.; Bafadhel, M.; Putcha, N. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet 2022, 399, 2227–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasim, F.; Sabath, B.F.; Eapen, G.A. Lung Cancer. Med Clin North Am 2019, 103, 463–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano Gotarredona, M.P.; Navarro Herrero, S.; Gómez Izquierdo, L.; Rodríguez Portal, J.A. Smoking-Related Interstitial Lung Disease. Radiologia (Engl Ed) 2022, 64 Suppl 3, 277–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, J.K.; Duffy, S.W.; Baldwin, D.R.; Brain, K.E.; Devaraj, A.; Eisen, T.; Green, B.A.; Holemans, J.A.; Kavanagh, T.; Kerr, K.M.; et al. The UK Lung Cancer Screening Trial: A Pilot Randomised Controlled Trial of Low-Dose Computed Tomography Screening for the Early Detection of Lung Cancer. Health Technol Assess 2016, 20, 1–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kramer, B.S.; Berg, C.D.; Aberle, D.R.; Prorok, P.C. Lung Cancer Screening with Low-Dose Helical CT: Results from the National Lung Screening Trial (NLST). J Med Screen 2011, 18, 109–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darrason, M.; Grolleau, E.; De Bermont, J.; Couraud, S. UKLS Trial: Looking beyond Negative Results. The Lancet Regional Health - Europe 2021, 10, 100184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American College of Radiology Committee on Lung-RADS. Lung-RADS 2022. Available online: https://www.acr.org/-/media/ACR/Files/RADS/Lung-RADS/Lung-RADS-2022 (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- Lynch, D.A.; Austin, J.H.M.; Hogg, J.C.; Grenier, P.A.; Kauczor, H.-U.; Bankier, A.A.; Barr, R.G.; Colby, T.V.; Galvin, J.R.; Gevenois, P.A.; et al. CT-Definable Subtypes of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A Statement of the Fleischner Society. Radiology 2015, 277, 192–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecht, H.S.; Cronin, P.; Blaha, M.J.; Budoff, M.J.; Kazerooni, E.A.; Narula, J.; Yankelevitz, D.; Abbara, S. 2016 SCCT/STR Guidelines for Coronary Artery Calcium Scoring of Noncontrast Noncardiac Chest CT Scans: A Report of the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography and Society of Thoracic Radiology. Journal of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography 2017, 11, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Qiu, Y.; Ji, X.; Dong, L. Effects of Smoking Cessation on Individuals with COPD: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1433269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, H.; Liu, Q.; Ye, Q.; Liang, Z.; Long, Z.; Hu, Y.; Wu, Q.; Jiang, M. Impact of Smoking Cessation Duration on Lung Cancer Mortality: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology 2024, 196, 104323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pezzuto, A.; Ricci, A.; D’Ascanio, M.; Moretta, A.; Tonini, G.; Calabrò, N.; Minoia, V.; Pacini, A.; De Paolis, G.; Chichi, E.; et al. Short-Term Benefits of Smoking Cessation Improve Respiratory Function and Metabolism in Smokers. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2023, 18, 2861–2865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, W.; Aarsand, R.; Schotte, K.; Han, J.; Lebedeva, E.; Tsoy, E.; Maglakelidze, N.; Soriano, J.B.; Bill, W.; Halpin, D.M.G.; et al. Tobacco and COPD: Presenting the World Health Organization (WHO) Tobacco Knowledge Summary. Respir Res 2024, 25, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brassington, K.; Selemidis, S.; Bozinovski, S.; Vlahos, R. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease and Atherosclerosis: Common Mechanisms and Novel Therapeutics. Clinical Science 2022, 136, 405–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotlyarov, S. The Role of Smoking in the Mechanisms of Development of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease and Atherosclerosis. IJMS 2023, 24, 8725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libby, P. The Changing Landscape of Atherosclerosis. Nature 2021, 592, 524–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Dwyer, E.; Halpenny, D.F.; Ginsberg, M.S. Lung Cancer Screening in Patients with Previous Malignancy: Is This Cohort at Increased Risk for Malignancy? Eur Radiol 2021, 31, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tammemägi, M.C.; Ruparel, M.; Tremblay, A.; Myers, R.; Mayo, J.; Yee, J.; Atkar-Khattra, S.; Yuan, R.; Cressman, S.; English, J.; et al. USPSTF2013 versus PLCOm2012 Lung Cancer Screening Eligibility Criteria (International Lung Screening Trial): Interim Analysis of a Prospective Cohort Study. The Lancet Oncology 2022, 23, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tammemägi, M.C.; Katki, H.A.; Hocking, W.G.; Church, T.R.; Caporaso, N.; Kvale, P.A.; Chaturvedi, A.K.; Silvestri, G.A.; Riley, T.L.; Commins, J.; et al. Selection Criteria for Lung-Cancer Screening. N Engl J Med 2013, 368, 728–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).