1. Introduction

Malignant neoplasms are among the leading causes of death from non-communicable diseases in industrialized countries, with lung cancer (LC) accounting for approximately 23.5 deaths per 100,000 individuals in 2021[

1]. While only a small proportion of malignant tumors are hereditary[

2], the majority are associated with modifiable lifestyle factors such as smoking, excessive alcohol consumption, and exposure to environmental and occupational carcinogens[

3,

4].

Occupational exposure to carcinogens contributes to a significant proportion of malignant tumors, with approximately 17% of all lung cancer deaths attributed to work-related exposures[

5]. However, occupational cancers remain significantly underreported worldwide[

6,

7,

8,

9], including in Italy[

10].

Lung cancer typically develops through a multistep carcinogenic process spanning decades, characterized by the accumulation of genetic mutations and epigenetic alterations affecting various cellular pathways[

11]. LC is histologically classified into small cell lung cancer (SCLC) and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). SCLC is a hypermutated subtype strongly associated with tobacco smoking, whereas NSCLC - particularly adenocarcinomas - can occur in non-smokers and individuals with unclear environmental exposures.

Since the early 2000s, advances in molecular biology have enabled the identification of driver mutations in NSCLC. These mutations, positively selected during tumor progression, confer growth advantages to cancer cells and are collectively described under the concept of "oncogene addiction." Currently, up to 60% of pulmonary adenocarcinomas in Western countries are considered “oncogene-addicted” tumors[

12], characterized by mutations in genes such as EGFR, ALK, ROS1, and BRAF.

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has become a standard diagnostic tool for lung adenocarcinoma, enabling the detection of actionable mutations[

13,

14,

15,

16,

17].

To date, to our best knowledge, no significant differences have been reported in clinical presentation, diagnostic approach, or treatment strategies between lung cancers related or unrelated to occupational carcinogen exposure.

This study investigates the hypothesis that previous occupational exposure to lung car-cinogens may influence the phenotypic and molecular profiles of lung cancer. Specifically, we assessed whether such exposure is associated with distinct histologic subtypes and oncogenic pathways, including the presence of "oncogene addiction”. Confirming this association would underscore the importance of detailed occupational history in lung cancer management and prognosis. Additionally, identifying patients whose lung cancer is potentially attributable to occupational exposures could aid in their eligibility for compensation and contribute to epidemiological surveillance.

2. Materials and Methods

We conducted a real-life observational study involving patients diagnosed with lung cancer at two secondary care institutions in Northern Italy: the Oncology Department of ICS Maugeri in Pavia and the Cancer Center at Humanitas Research Hospital in Milan (CC-HRH). All patients underwent comprehensive clinical assessment and molecular profiling using NGS as part of standard care. Occupational exposure to recognized lung carcinogens was documented. Tumor histology and mutational status were then correlated with exposure history to evaluate potential relationships between external exposome and lung cancer phenotype. Smoking history and its interaction with occupational exposure were also analyzed.

2.1. Study Population

This study included all consecutive patients diagnosed with lung cancer (LC) and monitored or treated at ICS Maugeri and CC-HRH between October 2021 and November 2023. All patients presenting to the two centers during this period were considered eligible for enrollment, except for those who explicitly declined to participate.

No exclusion criteria were applied based on histological subtype; thus, the cohort includes cases of adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, small cell lung cancer (SCLC), and other less common histologic variants.

Comprehensive clinical, diagnostic, epidemiological, and therapeutic data were collected from medical records for each participant.

The study was approved by the respective Local Ethics Committees (ICS Maugeri approval no. 2598/CE; CC-HRH approval no. 1459653/CE) and was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2. Clinical and Anatomopathological Data: Classification of Non-Oncogene Addicted (nOA) Cases

Clinical and anatomopathological data were obtained from each personal medical records. Disease staging was classified using the TNM system, UJCC 8th edition. Morphological and immuno-histochemical characteristics—including adenocarcinomas, squamous cell carcinoma, and SCLC—were assessed using standard clinical procedures. In cases of adenocarcinoma, specific gene mutations were identified using Easy PGX ready Kits (Diatech) and real-time PCR for mutations in ALK, ROS1, RET, MET exon 14 skipping, KRAS and BRAF. EGFR mutations were analyzed on exons 18–21 using either Easy PGX ready Kits (Diatech) or IDYLLA Biocartis. Once available, clinically relevant mutations were tested with characterized with generation sequencing (NGS, hot spot Oncomine Precision Assay GX, Genexus, Thermo Fisher). Both EGFR and BRAF mutations were examined in tissue biopsies or liquid biopsies obtained from blood samples. The oncogene addiction status (OA) was defined as the presence of a single mutation, regardless of the affected gene, except for KRAS since this mutation is generally considered as a marker of relevant environmental exposure.[

18] The KRAS mutation was not regularly assessed in the group of patients of ICS-Maugeri. All the other tumors were classified as non-oncogene addicted (nOA). For each case of LC the date of diagnosis was identified corresponding to that of the first histological report. The date of LC onset was estimated by considering a latency time of 13.6 years, in keeping with Nadler and Zurbenko.[

19,

20]

2.3. Occupational Exposure Evaluation

Data on occupational exposure and lifestyle habits were collected in two sequential steps. Initially, a standardized questionnaire—recommended by the Occupational Cancer Study Group of the Lombardy Region (Italy)—was administered to provide a preliminary overview. Interviews were conducted by occupational physicians who were informed about patients’ clinical status, but unaware of histologic and mutational features of each case. All interviews took place during hospitalization or day-hospital visits for therapy.

This first-level assessment aimed to preliminarily distinguish patients with potential occupational exposure to carcinogens from those likely unexposed, based on the industrial sector and job tasks described. Each patient's occupational roles were coded using the International Standard Industrial Classification of All Economic Activities (ISIC, Revision 4, 2008)[

21].

In a second step, patients identified as potentially exposed were further evaluated using a sector-specific questionnaire developed by INAIL within the ReNalOcCaM system[

22]. This phase enabled more detailed identification of individual exposure to occupational lung carcinogens.

Following both assessments, patients were categorized into three subgroups: a) higher exposed (HE): patients whose longest-held job was in sectors with known exposure to lung carcinogens; b) lower exposed (LE): patients with at least one job involving possible exposure, although this was not the predominant occupation; c) not exposed (NE): patients with no reasonable occupational exposure to lung carcinogens.

Classification was based on the list of lung carcinogens as defined by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC)[

23].

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Differences in demographic, clinical, histological characteristics of lung cancer (LC), and occupational exposure profiles between patients enrolled at the two participating centers were assessed using the χ² test. Differences in age were analyzed using the independent samples T-test or the Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test, depending on the distribution of the data.

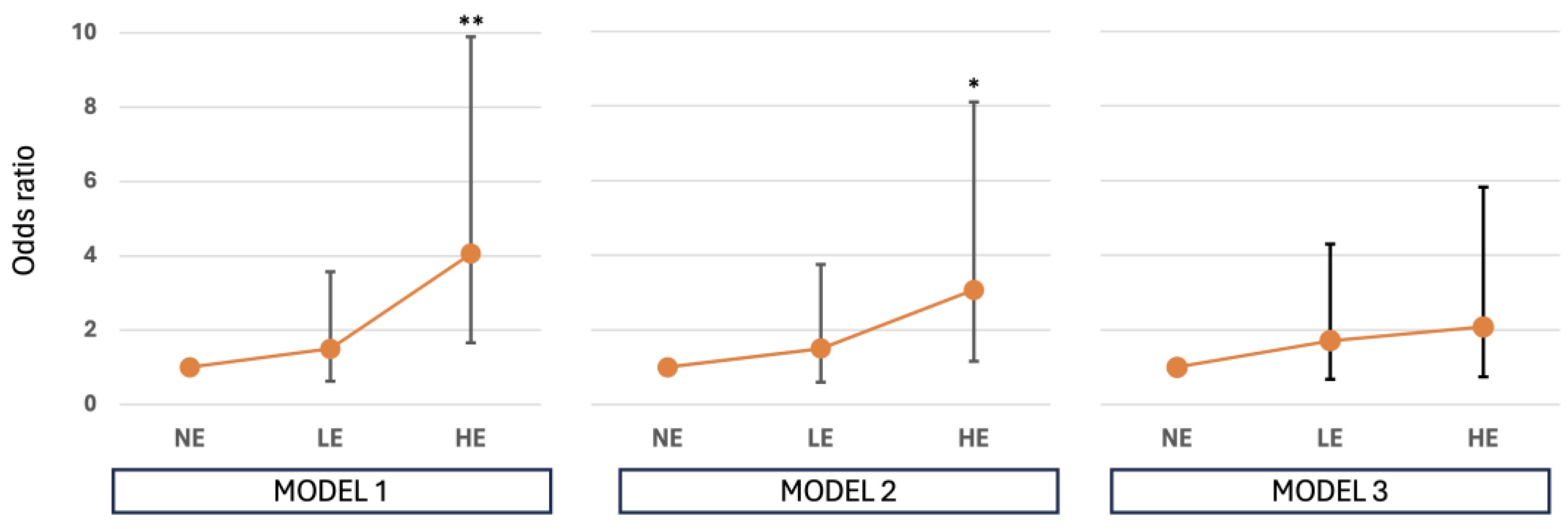

Logistic regression models were employed to assess the association between occupational exposure to lung carcinogens and the presence of oncogene-addicted (nOA) status, as previously defined. Three models were developed: a) model 1: unadjusted analysis evaluating the association between exposure classification (HE, LE, NE) and nOA status; b) model 2: adjusted for potential confounders including smoking status (never smoker, former smoker, current smoker at diagnosis), age at diagnosis (as a continuous variable), and sex; and c) model 3: adjusted using the same covariates as model 2, with smoking history represented as pack-years (calculated as the number of cigarettes smoked per day divided by 20 and multiplied by the number of years of active smoking).

Statistical significance was defined at an alpha level of 0.05 (p < 0.05), and all tests were two-sided. Data analyses were performed using STATA software, version 18 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA, 2015).

3. Results

A total of 199 patients were enrolled in the study, with 100 patients from ICS Maugeri and 99 from CC-HRH. Demographic characteristics and age at enrollment for the two groups are summarized in

Table 1. The majority of lung cancer cases occurred in individuals over 60 years of age (n=158, 79.4%), with no statistically significant differences observed between the two centers.

At the time of lung cancer diagnosis, approximately 40% of patients were current smokers, while fewer than 10% had never smoked. The median pack-year value was slightly higher among patients enrolled at CC-HRH compared to ICS Maugeri; however, differences in smoking habits between the two centers were not statistically significant, regardless of the metric used (

Table 1).

In contrast, the prevalence of patients classified as HE to occupational lung carcinogens was significantly higher in the ICS Maugeri cohort. This difference was statistically significant both when considering all histological subtypes (p=0.010,

Table 1) and when the analysis was restricted to patients with adenocarcinoma (p=0.013).

3.1. Age at Diagnosis and Age at First Hiring

The majority of patients (74.9%) were aged 60 years or older at the time of diagnosis (

Table 2). The median age at which individuals began their first occupation was significantly lower among those classified as highly exposed (HE) compared to those with lower or no exposure. This was observed both in the overall cohort (16 vs. 19.5 years, p<0.001) and within the adenocarcinoma subgroup (16 vs. 20 years, p<0.001).

A significant difference was also found regarding the decade in which individuals entered the workforce: 51.1% of HE workers started employment before 1970, compared to 36.8% among LE and NE patients (p<0.001). This trend remained significant when considering only patients with adenocarcinoma (51.4% vs. 33.1%, p<0.001).

Patients recruited at CC-HRH were significantly younger than those enrolled at ICS Maugeri (median age 66 vs. 69 years, p=0.03), a difference that persisted when the analysis was restricted to adenocarcinoma cases (65.5 vs. 69 years, p=0.02).

Notably, a larger proportion of ICS Maugeri patients started working before 1970 compared to those from CC-HRH (48.0% vs. 32.3%, respectively). Similar distributions were observed among adenocarcinoma patients (46.2% at ICS Maugeri vs. 27.8% at CC-HRH).

3.2. Tumor Histological Types and Gene Mutations

Adenocarcinoma was the most prevalent histological subtype among enrolled patients (

Table 2). Squamous cell carcinoma was the second most frequent, with 26 cases (13.1%). No statistically significant association was observed between occupational exposure to lung carcinogens and lung cancer histological subtypes (

Table S1).

The prevalence of gene mutations was similar between the two study sites (

Table 2). As expected, KRAS mutations were the most frequently detected. However, this mutation was not systematically assessed in patients from ICS Maugeri, which may explain the observed differences in KRAS mutation frequency between the two cohorts (

Table 2).

The second most common mutation was in the EGFR gene, found in 14 cases overall (7.0%), with 5 cases identified in the ICS Maugeri cohort and 9 in the CC-HRH cohort.

3.3. Occupational Exposures

Most patients were classified as not exposed (NE, 117 cases 58.8% of the total cohort—49 from ICS Maugeri and 68 from CC-HRH). A relevant proportion of cases (n=34, 17.1%) were categorized as lower exposed (LE). Notably, the number of patients classified as highly exposed (HE) was higher in the ICS Maugeri group (31 cases) compared to the CC-HRH group (16 cases).

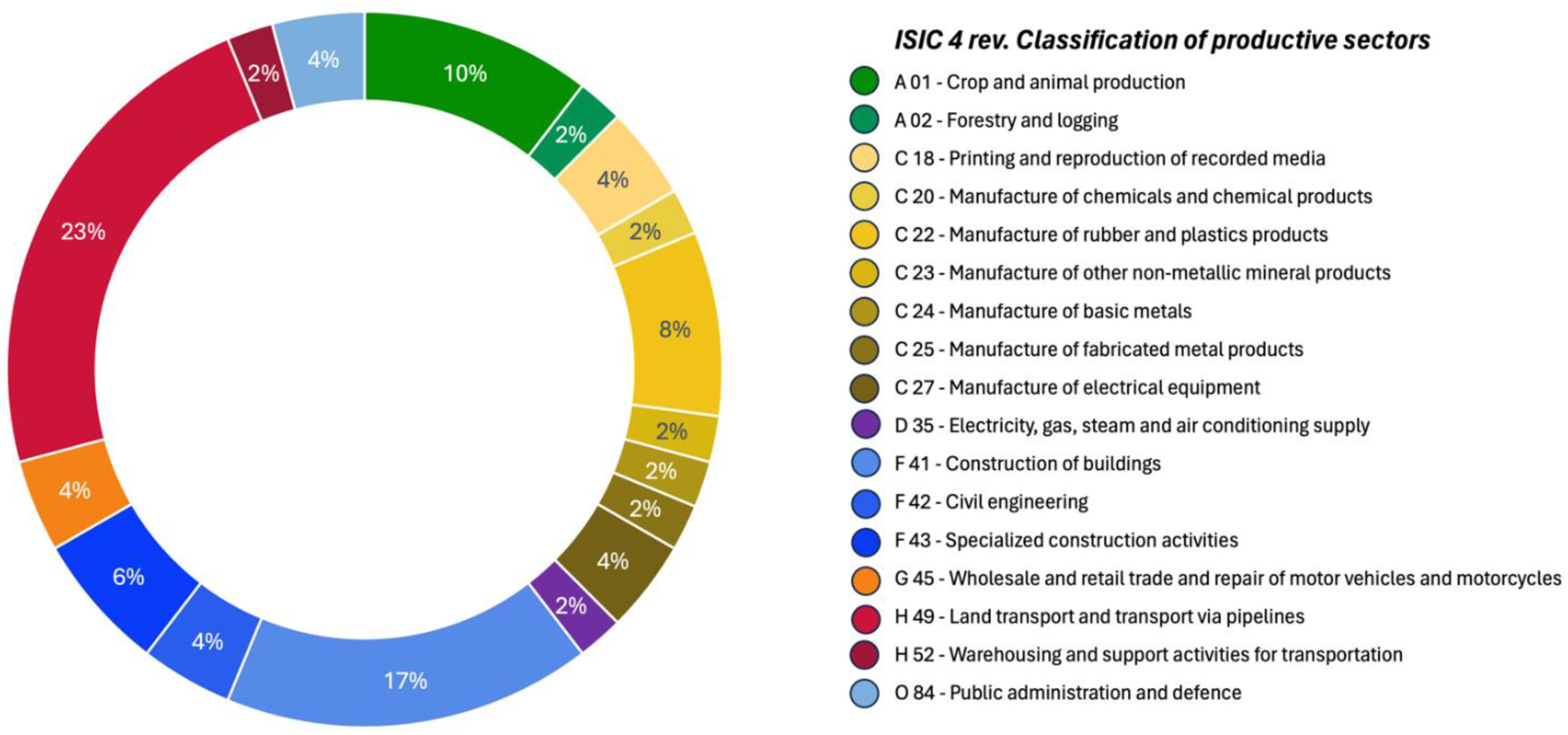

The occupational sectors in which HE patients were employed are summarized in

Figure 1. The most represented sectors included land transportation, construction, and agriculture, alongside various manufacturing industries, which collectively accounted for 24% of HE cases.

The most frequently identified occupational carcinogens among HE patients were diesel engine exhaust, ambient air pollution, rubber production by-products, welding fumes, asbestos, and bis(chloromethyl)ether.

3.4. Occupational Exposure and Oncogene-Addiction State

The Occupational Exposure at putative LC onset and 5 and 10 years before this point, as well as exposure at diagnosis and 5 and 10 years before diagnosis, were considered. The two populations were similar across all categories, and no statistically significant differences were observed (

Table S2).

We found a significant increase in the likelihood of developing a nOA phenotype in patients with HE to occupational carcinogens compared to NE. These results remain statistically significant even when adjusted for age at diagnosis and smoking habits. Specifically, by applying model 2 we found an OR of 3.07 (95% CI 1.16-8.11, p=0.023), while results adjusted according to model 3 still account for an OR of 2.08 (95% CI 0.74-5.82, p=0.162), although not reaching the conventional statistical significance (

Table 3,

Figure 2).

A significant association was identified between patients HE to occupational lung carcinogens and the likelihood of developing an oncogene-addicted (nOA) lung cancer phenotype, compared to NE individuals. This association remained statistically significant after adjustment for age at diagnosis and smoking status.

Specifically, logistic regression model 2 (adjusted for smoking status, age, and sex) yielded an odds ratio (OR) of 3.07 (95% CI: 1.16–8.11; p=0.023). model 3, which incorporated smoking intensity as pack-years, produced a lower but still elevated OR of 2.08 (95% CI: 0.74–5.82), although this result did not reach statistical significance (p=0.162) (

Table 3,

Figure 2).

Occupational exposure was assessed at the estimated time of lung cancer onset, as well as at 5 and 10 years prior to that point. Exposure status at diagnosis, and 5 and 10 years before diagnosis, was also considered. No statistically significant differences were observed between the two study populations across these time points (

Table S2). Although not reaching the conventional threshold for statistical significance, the results suggest a possible correlation between the timing of exposure and oncogenic effects. Workers exposed to lung carcinogens at least 5 to 10 years prior to diagnosis demonstrated a 1.5- to 2.0-fold increased risk of developing oncogene-addicted (nOA) adenocarcinoma, compared to those not exposed at the same timepoint (

Table S3). Similarly, individuals occupationally exposed to carcinogens 5 or 10 years before lung cancer onset showed a 1.4- to 1.8-fold increased risk of developing nOA adenocarcinoma. However, this association was no longer evident after adjusting for smoking habits using pack-years (Model 3,

Table S3).

4. Discussion

4.1. Actionable Gene Mutations, Histotypes and Occupational Exposure

Our study showed that the distribution of actionable gene mutations differed between lung cancers in patients with occupational exposure to carcinogens compared to patients not occupationally exposed. The formers seem to be more often characterized by the nOA mutational pathway.

The recent insights on the role of environmental exposure, including the occupational one, in promoting cancer even interacting with one another[

24] increase the interest in searching for a potential relationship between exposure and mutation load in LC. To our knowledge, no data are available about the potential role of different environmental and occupational exposure in influencing the LC mutational load. In this context, generating evidence on the development of LC in people with occupational exposure to carcinogens and describing their LC mutational characteristics may help the understanding of etiopathogenesis, mechanisms of cancer genesis and guide evidence-based prevention efforts. When looking at the overall prognosis of metastatic LC, we must recognize that we deal with a disease whose prognosis ultimately is dismal under every biological condition. Despite this consideration, targeted agents (e.g. EGFR inhibitors in EGFR altered LC) have robustly proved to offer prolonged clinical benefits to patients affected by oncogene addicted disease[

25]. On the other hands, tumors without recognizable conditions of oncogene addiction, as seem to be more frequent in patients exposed to occupational carcinogens, require different therapeutic approaches based on chemotherapy and/or immunotherapy, that are associated with an increased toxicity, and less predictable benefit[

26]. We do not have an explanation about the higher risk of having a nOA LC among people occupationally exposed to carcinogens as observed in the present study. However, this should stimulate new experimental studies to clarify this unexpected finding. In addition, the higher severity of prognosis in nOA LC patients, further increase the importance of occupational exposure reduction.

As reported in method and result sessions, ICS Maugeri did not search for the KRAS mutation in all patients, and this may explain this unique difference observed in mutation profile between the two groups. The groups recruited in the two centers differ significantly from each other in the KRAS mutation frequency (

Table 1). This difference may be explained by a different approach in testing gene mutations between the two centers. The clinical protocol adopted by ICS Maugeri did not include the systematic screening for the KRAS mutation, whereas this procedure was applied to all adenocarcinoma cases enrolled at CC-HRH. The role of KRAS mutations, particularly the G12C variant, has been primarily recognized for its prognostic significance. Only recently, the targeted therapies, such as sotorasib and adagrasib, have become available, and these are typically prescribed as second-line treatment options[

18]. For this reason, the KRAS-driven LC were grouped together with other nOA LC and analyzed accordingly.

Moreover, it is worth noting that within the same groups, no significant differences were found in lung cancer histological characteristics between subjects with and without occupational exposure to carcinogens. In keeping with previous observations arising from the same Italian region[

27], the present study confirms that the histotype of LC was similar in patients exposed and not exposed to occupational carcinogens (

Table S1).

4.2. Occupational Exposures

The prevalence of HE in our population is about 23.6%. This observation is substantially consistent with the results observed in previous studies conducted in the Lombardy region. In particular, in 2012 the EAGLE study showed that among the analyzed cases of LC, the prevalence of exposure to asbestos, silica, nickel-chromium, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, and diesel motor exhausts ranged between 41.1% and 24.1%[

27]. A recent Italian study involving 453 lung cancer cases identified occupational exposures in approximately 24.5% of patients[

28].

Although demographics, LC clinical, histological and mutational features were similar in the two groups, occupational exposures were more frequent in ICS Maugeri subgroup. This result could be explained considering that the ICS Maugeri population is slightly older at the time of diagnosis and younger at the time of first employment, with the majority having started their occupational careers before 1970 both in the entire population and in adenocarcinoma subgroup. This difference may also account for a variation in exposure, with a higher likelihood or greater intensity of exposure in earlier periods. In fact, about 50% of HE cases were observed to be first hired before 1970 and almost all before 1980. Moreover, the difference in HE prevalence between the two centers is likely reflected with the socioeconomic disparities between the two catchment areas.

Finally, it cannot be ruled out that, among workers exposed to lung carcinogens, there are individuals in this study who experienced multiple exposures to more than one carcinogenic agent—either simultaneously during the same employment period or sequentially across different periods. Such multiple exposures may have led to a greater increase in risk[

24], although the extent of this increase cannot be precisely determined based on the available data.

4.3. Smoke Habits

The role of smoke habit in causing lung cancer has been widely described[

29] and recently confirmed by several epidemiological studies[

30]. For this reason, to disentangle the role of occupational exposure in the observed high probability of developing nOA LC, some additional models adjusting data by the smoke habitude were used. Of interest, if the data were adjusted by sex, age at diagnosis and smoke habits considered as never smokers, formers and current smokers at diagnosis, the increased OR of people classified as HE to carcinogens in workplace in developing nOA LC was confirmed. In the last model used in this study the data was adjusted by considering the smoke habits as pack-years. In this case a slight increase OR of nOA LC in occupational exposed remains although not significant. It must be considered that the confidence intervals of ORs of nOA phenotype by exposure to occupational lung carcinogens (

Table 2 and

Figure 1) were very high in HE people. This may partially explain our results.

4.4. Timing of Exposure

Our results suggest that the starting time of occupational exposure in HE patients seems to influence the lung cancer genetic mutation load and confirm that the timing of exposure plays a role in LC development.

As expected, all the models used in this study indicate that the current exposure at the time of diagnosis does not appear to be associated with an increased risk for LC. In contrast, the occupational exposure to carcinogens occurring 5–10 years before diagnosis or 5–10 years before the disease onset, as defined in the method session, seems to be associated with a slight increase in risk, although this association is not statistically significant. This effect is small and likely difficult to detect accurately given the available data and the limited number of cases studied, but it is consistent with findings reported in the literature: a study on diesel exhaust reported a particularly elevated risk when exposure occurred between 10 and 19 years prior to death[

31], whereas some literature data suggest that, for similar cigarette smoking habits, an occupational exposure occurring 20 years prior to the case interview is more relevant than exposure during other time windows[

32].

It is impossible to precisely determine the true latency period of each individual lung cancer case. The definition of 'true latency' refers to the time interval between the initial malignant transformation of the first neoplastic cell that will eventually develop into the tumor, and the date of clinical diagnosis. Several linear models of lung cancer development have been proposed in the literature[

33], but these do not appear to be sufficiently accurate, partly due to biological evidence suggesting that neoplastic progression more likely follows a Gompertzian growth pattern[

33,

34]. For this reason, in the present study we adopted the estimation of ‘true latency’ using a Weibull model proposed by Nadler and Zurbenko[

19,

20], even if we are aware that it represents a theoretical approximation, and a high variability among individual clinical cases is present.

4.5. Limitations of the Study and Further Developments

Even if the sample size calculated was widely overcoming in the present study, the great variability of the prevalence of the most relevant exposures to occupational carcinogens limited some results. We do believe that a larger population could have allowed more conclusive results. Nevertheless, the results of the study are promising when the entire population and the most prolonged and intense exposures are considered. Furthermore, the small number did not allow separate analyses for different productive sectors, or to study the exposures to specific carcinogens. This latter has been estimated and described only qualitatively.

The risks of possible bias in the reconstruction of the exposure are known[

35,

36] and have been taken into account. The identification of a single carcinogenic agent is uncertain, due to the lack of awareness of many patients, and the difficulties in recalling the circumstances of the exposure as well as the chemicals or physical agents involved, even several years after the exposure itself. Moreover, it is well known that in some productive sectors and during specific job tasks the exposure to several carcinogens is common and it is not possible to enucleate the single carcinogen exposures. Thus, the retrospective assessment of occupational exposures of each LC case and the relative duration was carried out based on the patients' recall, with the support of specific validated questionnaires.[

22] This method of evaluating exposure is often the only possible, given the long latency of occupational neoplasms (often decades) and the variation in exposure intensity or work environments. The approach used in the present study was qualitative, with the inclusion of each worker in one of the 3 categories of NE, LE and HE, because the quantitative exposure data were not available or not inferable for almost all cases. For these reasons, it is not possible to exclude the presence of residual misclassification in exposure assessment.

5. Conclusions

This real-world study suggests that the mutational landscape of lung adenocarcinoma may differ between patients with and without occupational exposure to lung carcinogens. Occupational exposure—representing a distinct subset of carcinogenic risk—may be associated with more complex tumor phenotypes, often lacking a single actionable driver mutation (non-oncogene addicted, nOA), thereby posing additional clinical and prognostic challenges.

These findings underscore the critical importance of robust occupational exposure prevention strategies and highlight the need to further explore the molecular and genetic characteristics of occupationally induced tumors. Such investigations could facilitate the identification of early biomarkers of carcinogenic effects, with potential applications not only in the general population but particularly in subgroups with known occupational exposures.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1. Lung cancer histotypes by lung carcinogen exposure, Pavia-Milan (Italy), 2022-2023; Table S2. Possible occupational exposure to lung carcinogens at specific time points, by center, Pavia-Milano, Italy, 2022-2023; Table S3. Risk of non-oncogene addicted phenotype of LC by exposure to occupational lung carcinogens at different time-points in patients with adenocarcinoma diagnosis, Pavia-Milan (Italy), 2022-2023.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.O., F.S. and F.B.; methodology, E.O. and F.S.; formal analysis, E.O.; investigation, E.O, L.D’A., R.P., D.M., L.T., S.F., G.R., L.S., L.F., C.C., F.S. F.B; writing—original draft preparation, E.O.; writing—review and editing, L.D’A., R.P., L.T., L.L., F.S, F.B.; visualization, R.P.; supervision, E.O., L.T., L.L. and F.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Local Ethics Committees: ICS Maugeri approval no. 2598/CE; CC-HRH approval no. 1459653/CE.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LC |

Lung Cancer |

| SCLC |

Small Cell Lung Cancer |

| NSCLC |

Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer |

| NGS |

Next-generation sequencing |

| ISIC |

International Standard Industrial Classification of All Economic Activities |

| INAIL |

Istituto Nazionale per l’Assicurazione per gli Infortuni sul Lavoro |

| IARC |

International Agency for Research on Cancer |

| EGFR |

Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor |

| ALK |

Anaplastic Lymphoma Kinase |

| ROS1 |

ROS proto-oncogene 1, receptor tyrosine kinase |

| BRAF |

B-Raf proto-oncogene, serine/threonine kinase |

| KRAS |

Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene |

| OA |

Oncogene Addicted |

| nOA |

Non-Oncogene Addicted |

References

- Naghavi, M.; Ong, K.L.; Aali, A.; Ababneh, H.S.; Abate, Y.H.; Abbafati, C.; Abbasgholizadeh, R.; Abbasian, M.; Abbasi-Kangevari, M.; Abbastabar, H.; et al. Global Burden of 288 Causes of Death and Life Expectancy Decomposition in 204 Countries and Territories and 811 Subnational Locations, 1990–2021: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. The Lancet 2024, 403, 2100–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenstein, P.; Holm, N.V.; Verkasalo, P.K.; Iliadou, A.; Kaprio, J.; Koskenvuo, M.; Pukkala, E.; Skytthe, A.; Hemminki, K. Environmental and Heritable Factors in the Causation of Cancer--Analyses of Cohorts of Twins from Sweden, Denmark, and Finland. N Engl J Med 2000, 343, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veglia, F.; Vineis, P.; Overvad, K.; Boeing, H.; Bergmann, M.M.; Trichopoulou, A.; Trichopoulos, D.; Palli, D.; Krogh, V.; Tumino, R.; et al. Occupational Exposures, Environmental Tobacco Smoke, and Lung Cancer. Epidemiology 2007, 18, 769–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harvard Report on Cancer Prevention: Volume 1: Causes of Human Cancer Harvard Center for Cancer Prevention Harvard School of Public Health. Cancer Causes Control 1996, 7, S3–S4. [CrossRef]

- GBD 2016 Occupational Carcinogens Collaborators Global and Regional Burden of Cancer in 2016 Arising from Occupational Exposure to Selected Carcinogens: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Occup Environ Med 2020, 77, 151–159. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curti, S.; Sauni, R.; Spreeuwers, D.; De Schryver, A.; Valenty, M.; Rivière, S.; Mattioli, S. Interventions to Increase the Reporting of Occupational Diseases by Physicians. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2015, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morelle, I.; Berghmans, T.; CsToth, I.; Sculier, J.-P.; Meert, A.-P. Apport du repérage des expositions professionnelles en oncologie thoracique : une expérience belge. Revue des Maladies Respiratoires 2014, 31, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orriols, R.; Isidro, I.; Abu-Shams, K.; Costa, R.; Boldu, J.; Rego, G.; Zock, J. ; other Members of the Enfermedades Respiratorias Ocupacionales y Medioambientales (EROM) Group Reported Occupational Respiratory Diseases in Three Spanish Regions. American J Industrial Med 2010, 53, 922–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérol, O.; Lepage, N.; Noelle, H.; Lebailly, P.; De Labrusse, B.; Clin, B.; Boulanger, M.; Praud, D.; Fournié, F.; Galvaing, G.; et al. A Multicenter Study to Assess a Systematic Screening of Occupational Exposures in Lung Cancer Patients. IJERPH 2023, 20, 5068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assennato, G.; De Giampaulis, C. When Occupational Cancer Recognition Falters. La Medicina del Lavoro 2025, 116, 16997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogelstein, B.; Papadopoulos, N.; Velculescu, V.E.; Zhou, S.; Diaz, L.A.; Kinzler, K.W. Cancer Genome Landscapes. Science 2013, 339, 1546–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedlaender, A.; Perol, M.; Banna, G.L.; Parikh, K.; Addeo, A. Oncogenic Alterations in Advanced NSCLC: A Molecular Super-Highway. Biomark Res 2024, 12, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, C.; Gasper, H.; Sahin, K.B.; Tang, M.; Kulasinghe, A.; Adams, M.N.; Richard, D.J.; O’Byrne, K.J. Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR)-Mutated Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC). Pharmaceuticals 2020, 13, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soda, M.; Choi, Y.L.; Enomoto, M.; Takada, S.; Yamashita, Y.; Ishikawa, S.; Fujiwara, S.; Watanabe, H.; Kurashina, K.; Hatanaka, H.; et al. Identification of the Transforming EML4–ALK Fusion Gene in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Nature 2007, 448, 561–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, H.; Bignell, G.R.; Cox, C.; Stephens, P.; Edkins, S.; Clegg, S.; Teague, J.; Woffendin, H.; Garnett, M.J.; Bottomley, W.; et al. Mutations of the BRAF Gene in Human Cancer. Nature 2002, 417, 949–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawara, A. Trk Receptor Tyrosine Kinases: A Bridge between Cancer and Neural Development. Cancer Letters 2001, 169, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, M.G.; Di Noia, V.; D’Argento, E.; Vita, E.; Damiano, P.; Cannella, A.; Ribelli, M.; Pilotto, S.; Milella, M.; Tortora, G.; et al. Oncogene-Addicted Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: Treatment Opportunities and Future Perspectives. Cancers 2020, 12, 1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Ostrem, J.; Pellini, B.; Imbody, D.; Stern, Y.; Solanki, H.S.; Haura, E.B.; Villaruz, L.C. Overcoming KRAS -Mutant Lung Cancer. American Society of Clinical Oncology Educational Book 2022, 700–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadler, D.L.; Zurbenko, I.G. Developing a Weibull Model Extension to Estimate Cancer Latency. ISRN Epidemiology 2013, 2013, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadler, D.L.; Zurbenko, I.G. Estimating Cancer Latency Times Using a Weibull Model. Advances in Epidemiology 2014, 2014, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN International Standard Industrial Classification of All Economic Activities (ISIC), Rev.4; Statistical Papers (Ser. M); United Nations: s.l, 2008; ISBN 978-92-1-161518-0.

- Massari, S. Renaloccam: il sistema di monitoraggio delle neoplasie a bassa frazione eziologica : manuale operativo; Inail: Roma, 2021; ISBN 978-88-7484-700-6.

- Samet, J.M.; Chiu, W.A.; Cogliano, V.; Jinot, J.; Kriebel, D.; Lunn, R.M.; Beland, F.A.; Bero, L.; Browne, P.; Fritschi, L.; et al. The IARC Monographs: Updated Procedures for Modern and Transparent Evidence Synthesis in Cancer Hazard Identification. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute 2020, 112, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, A.; Bouaoun, L.; Schüz, J.; Vermeulen, R.; Behrens, T.; Ge, C.; Kromhout, H.; Siemiatycki, J.; Gustavsson, P.; Boffetta, P.; et al. Lung Cancer Risks Associated with Occupational Exposure to Pairs of Five Lung Carcinogens: Results from a Pooled Analysis of Case-Control Studies (SYNERGY). Environ Health Perspect 2024, 132, 017005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saw, S.P.L.; Le, X.; Hendriks, L.E.L.; Remon, J. New Treatment Options for Patients With Oncogene-Addicted Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer Focusing on EGFR -Mutant Tumors. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book 2024, 44, e432516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reck, M.; Remon, J.; Hellmann, M.D. First-Line Immunotherapy for Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. JCO 2022, 40, 586–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Matteis, S.; Consonni, D.; Lubin, J.H.; Tucker, M.; Peters, S.; Vermeulen, R.C.; Kromhout, H.; Bertazzi, P.A.; Caporaso, N.E.; Pesatori, A.C.; et al. Impact of Occupational Carcinogens on Lung Cancer Risk in a General Population. International Journal of Epidemiology 2012, 41, 711–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogni, M.; Cervino, D.; Rossi, M.R.; Galli, P. A 7-Year Active Surveillance Experience for Occupational Lung Cancer in Bologna, Italy (2017-2023). La Medicina del Lavoro 2025, 116, 16173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vineis, P.; Airoldi, L.; Veglia, F.; Olgiati, L.; Pastorelli, R.; Autrup, H.; Dunning, A.; Garte, S.; Gormally, E.; Hainaut, P.; et al. Environmental Tobacco Smoke and Risk of Respiratory Cancer and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease in Former Smokers and Never Smokers in the EPIC Prospective Study. BMJ 2005, 330, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secretan, B.; Straif, K.; Baan, R.; Grosse, Y.; El Ghissassi, F.; Bouvard, V.; Benbrahim-Tallaa, L.; Guha, N.; Freeman, C.; Galichet, L.; et al. A Review of Human Carcinogens—Part E: Tobacco, Areca Nut, Alcohol, Coal Smoke, and Salted Fish. The Lancet Oncology 2009, 10, 1033–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, D.T.; Bassig, B.A.; Lubin, J.; Graubard, B.; Blair, A.; Vermeulen, R.; Attfield, M.; Appel, N.; Rothman, N.; Stewart, P.; et al. The Diesel Exhaust in Miners Study (DEMS) II: Temporal Factors Related to Diesel Exhaust Exposure and Lung Cancer Mortality in the Nested Case–Control Study. Environ Health Perspect 2023, 131, 087002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauptmann, M.; Lubin, J.H.; Rosenberg, P.; Wellmann, J.; Kreienbrock, L. The Use of Sliding Time Windows for the Exploratory Analysis of Temporal Effects of Smoking Histories on Lung Cancer Risk. Stat Med 2000, 19, 2185–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detterbeck, F.C.; Gibson, C.J. Turning Gray: The Natural History of Lung Cancer Over Time. Journal of Thoracic Oncology 2008, 3, 781–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schabel, F.M. Concepts for Systemic Treatment of Micrometastases. Cancer 1975, 35, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grandjean, P.; Budtz-Jørgensen, E.; Keiding, N.; Weihe, P. Underestimation of Risk Due to Exposure Misclassification. Int J Occup Med Environ Health 2004, 17, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blair, A.; Stewart, P.; Lubin, J.H.; Forastiere, F. Methodological Issues Regarding Confounding and Exposure Misclassification in Epidemiological Studies of Occupational Exposures. American J Industrial Med 2007, 50, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).