Submitted:

24 March 2025

Posted:

26 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

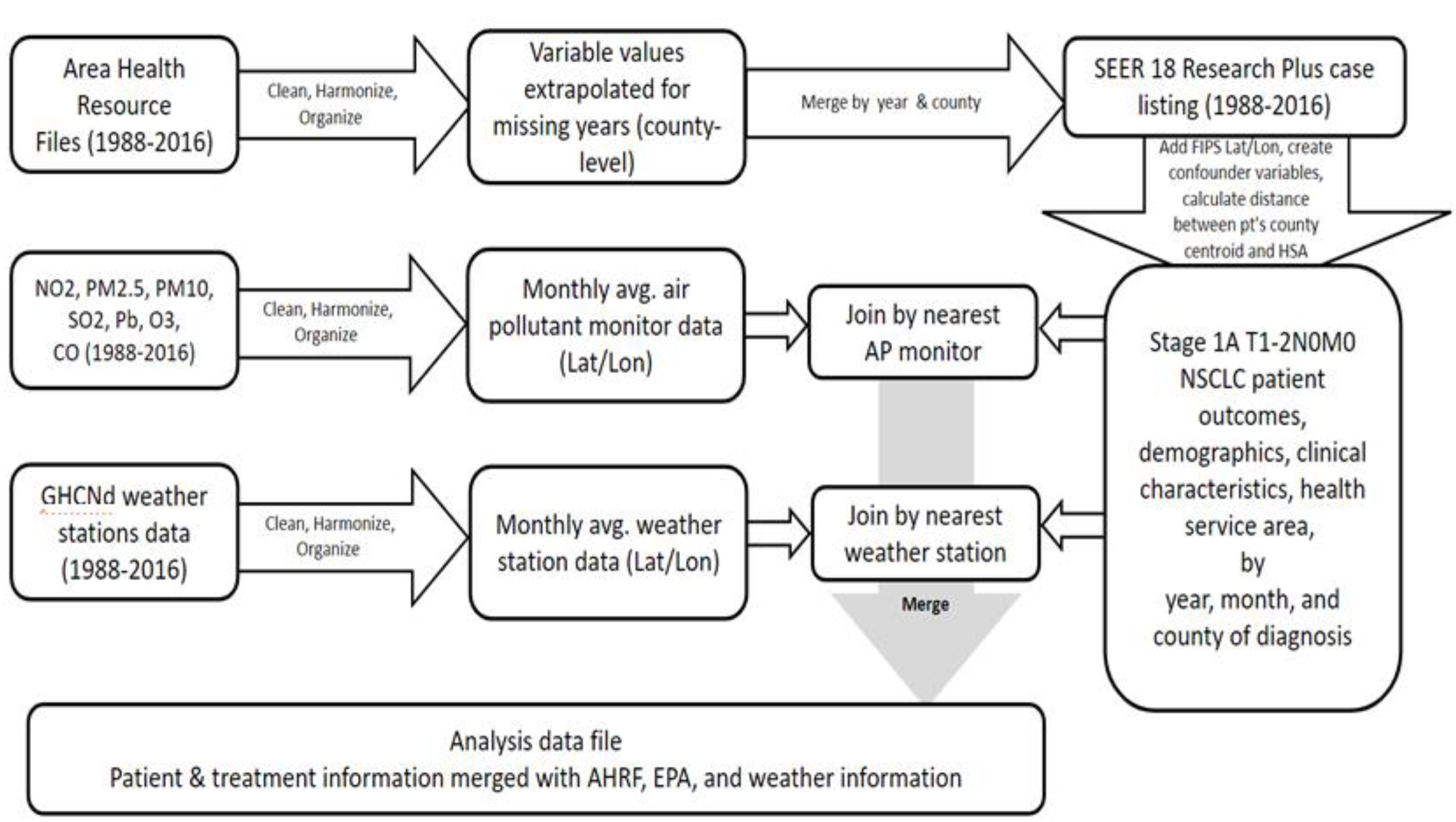

2.2. Data Sources and Construction of Analysis Data File

2.3. Statistical Analysis and Empirical Model

2.4. Sensitivity Analyses

2.5. Ethical considerations

2.6. Sampling Strategy, Exposure Assignment, and Study Variables

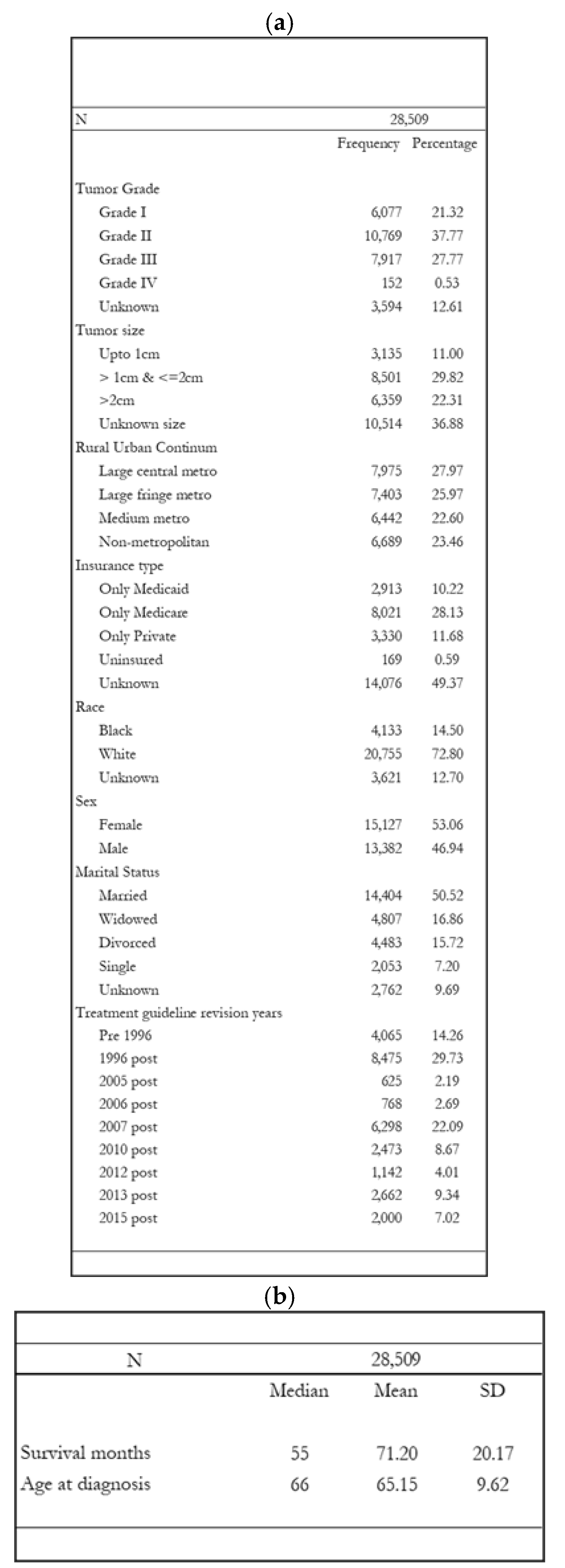

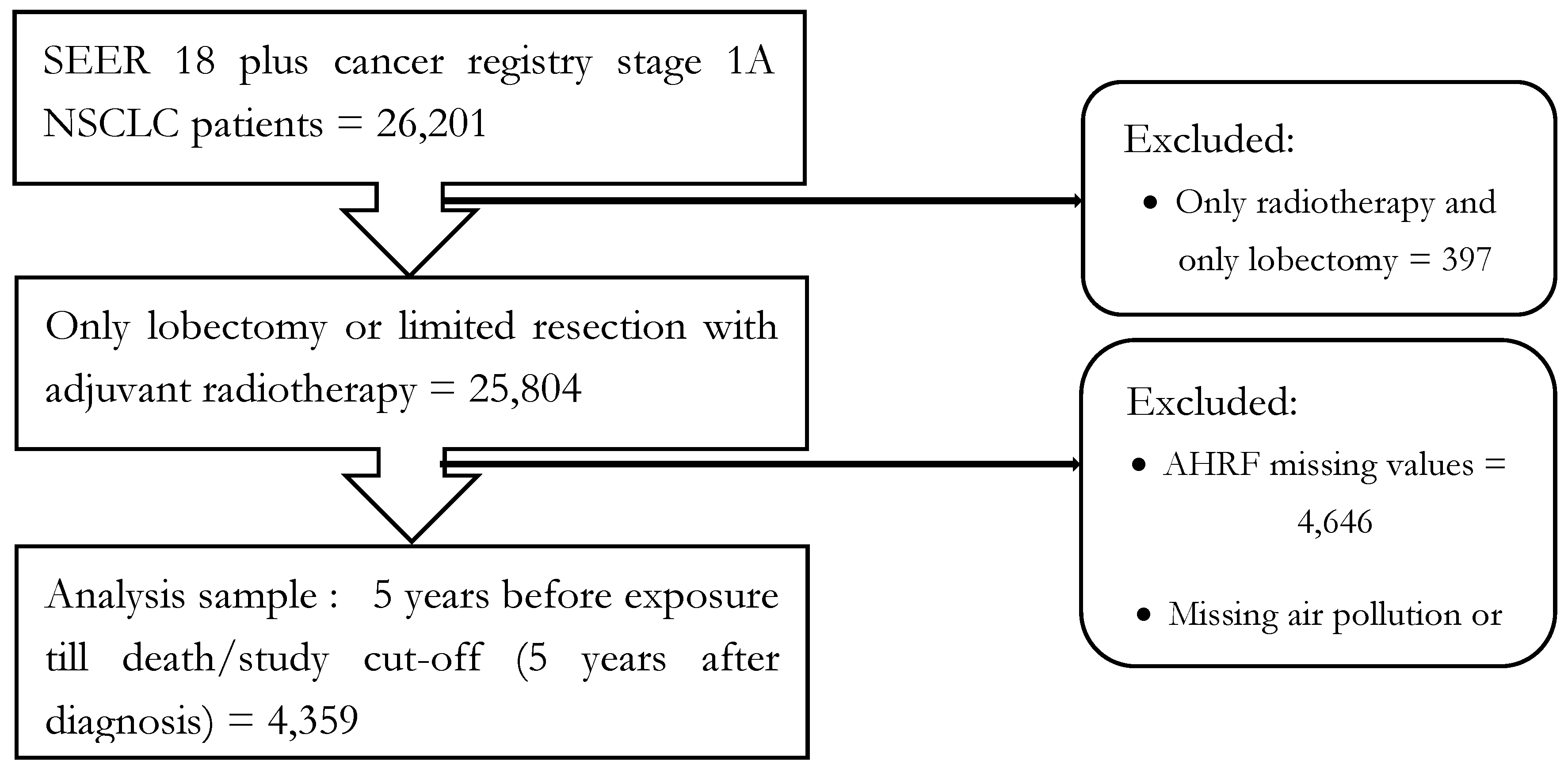

2.6.1. Population and sample

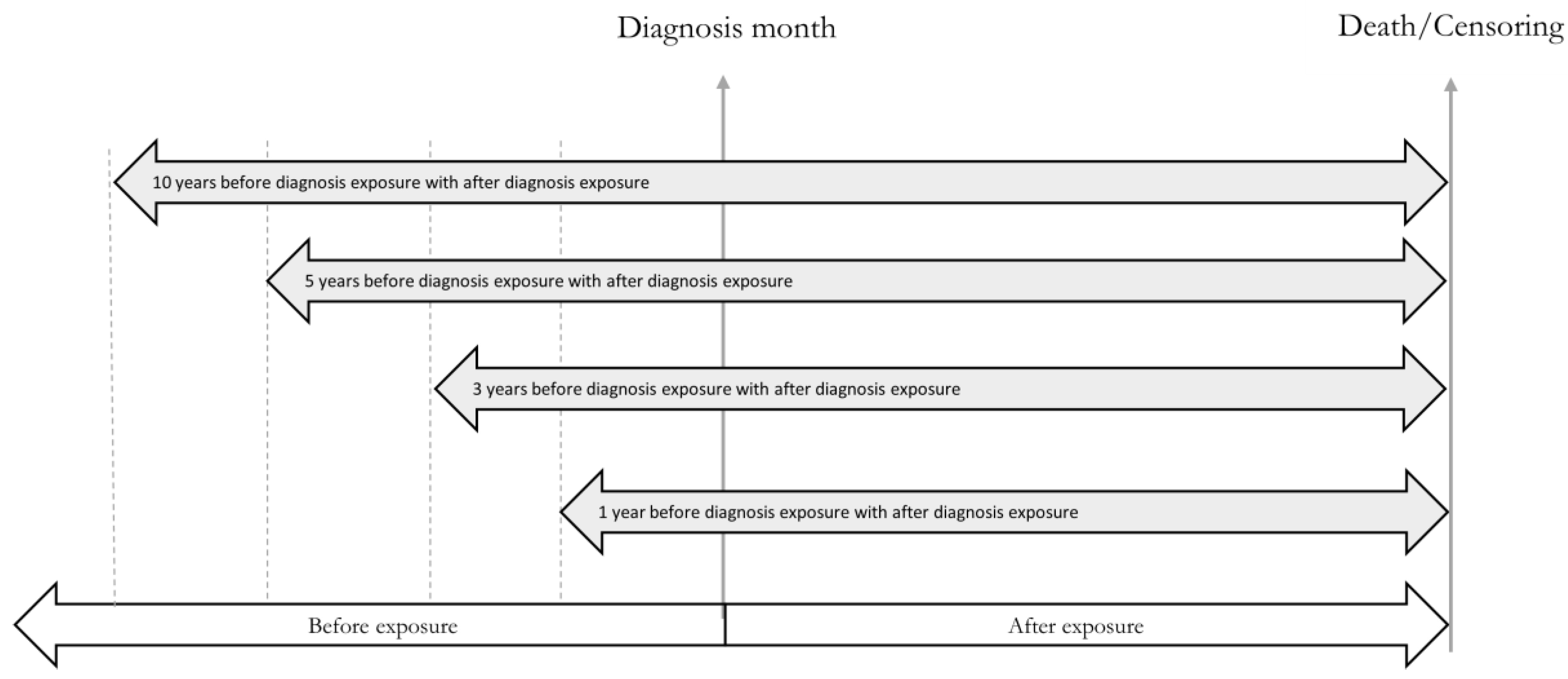

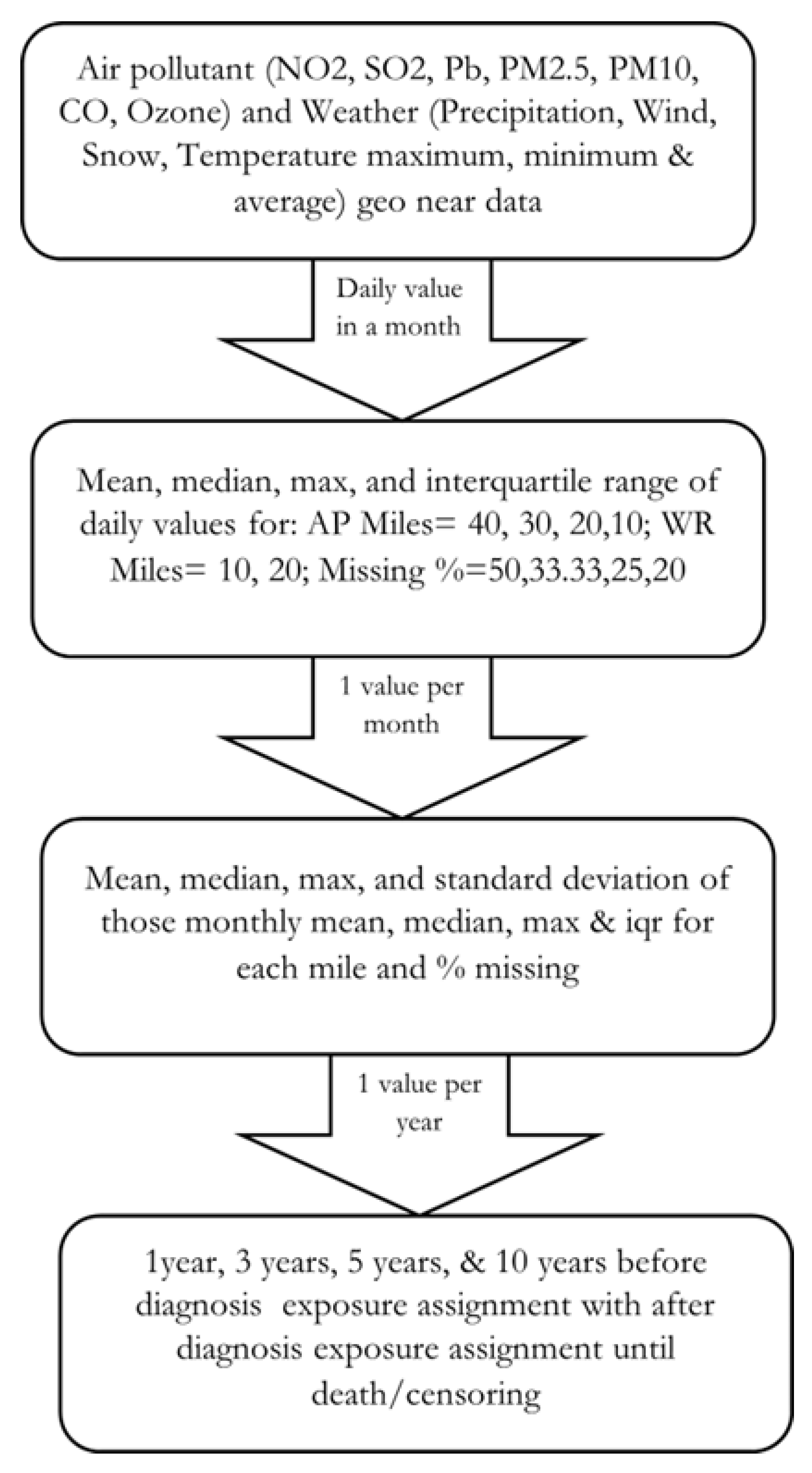

2.6.2. Exposure Assignment

2.6.3. Independent Variables

2.6.4. Outcome Variable

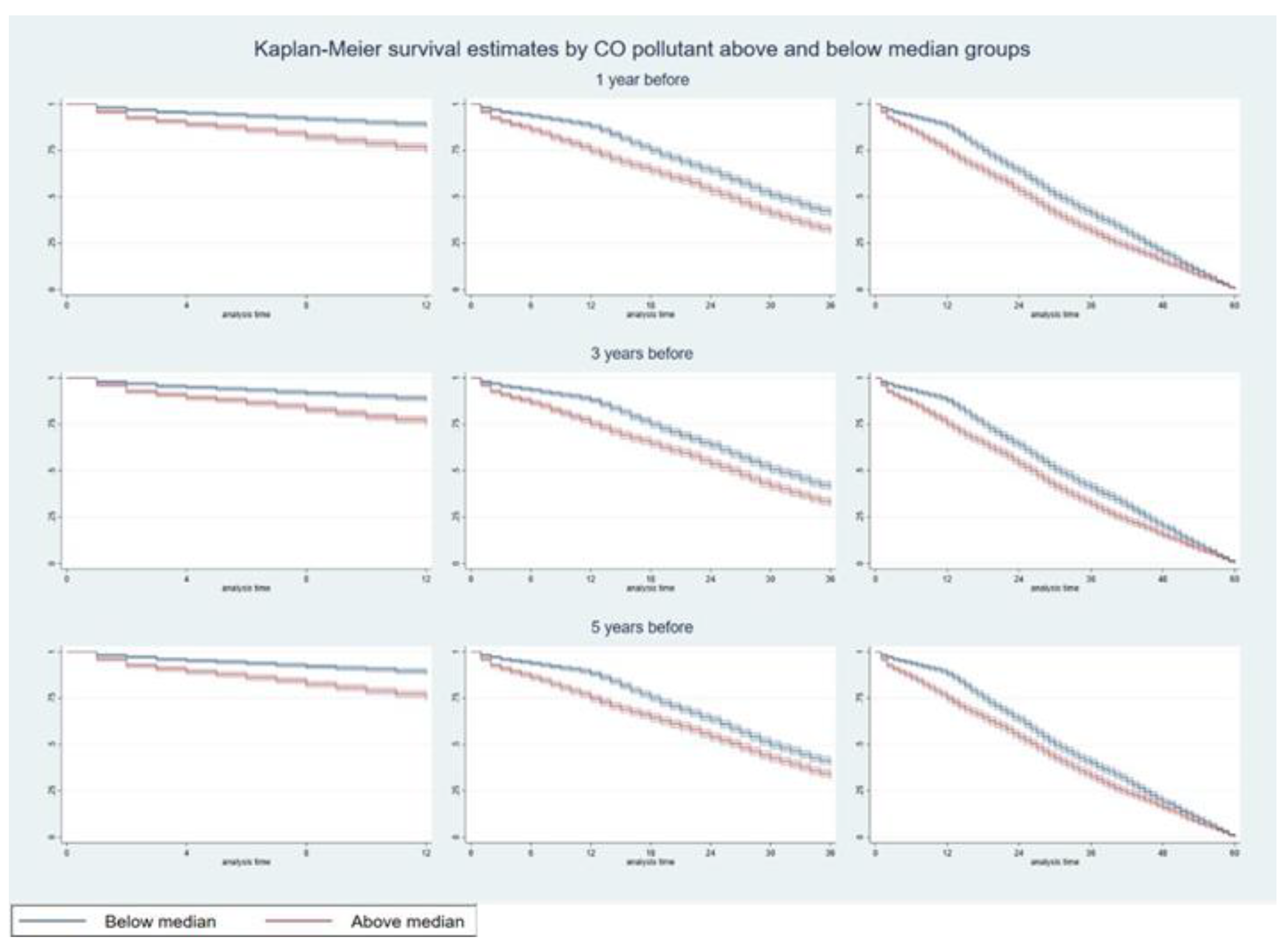

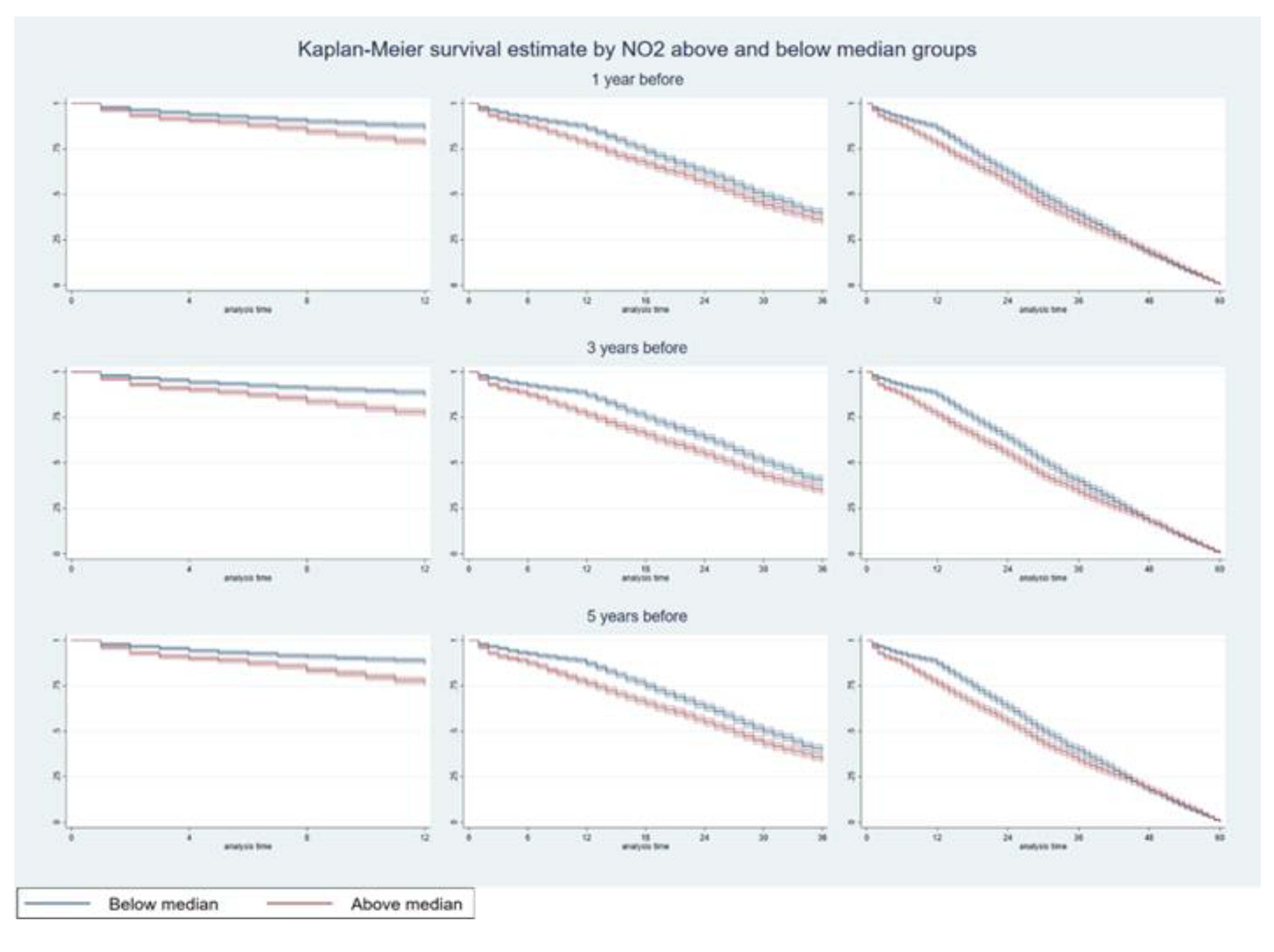

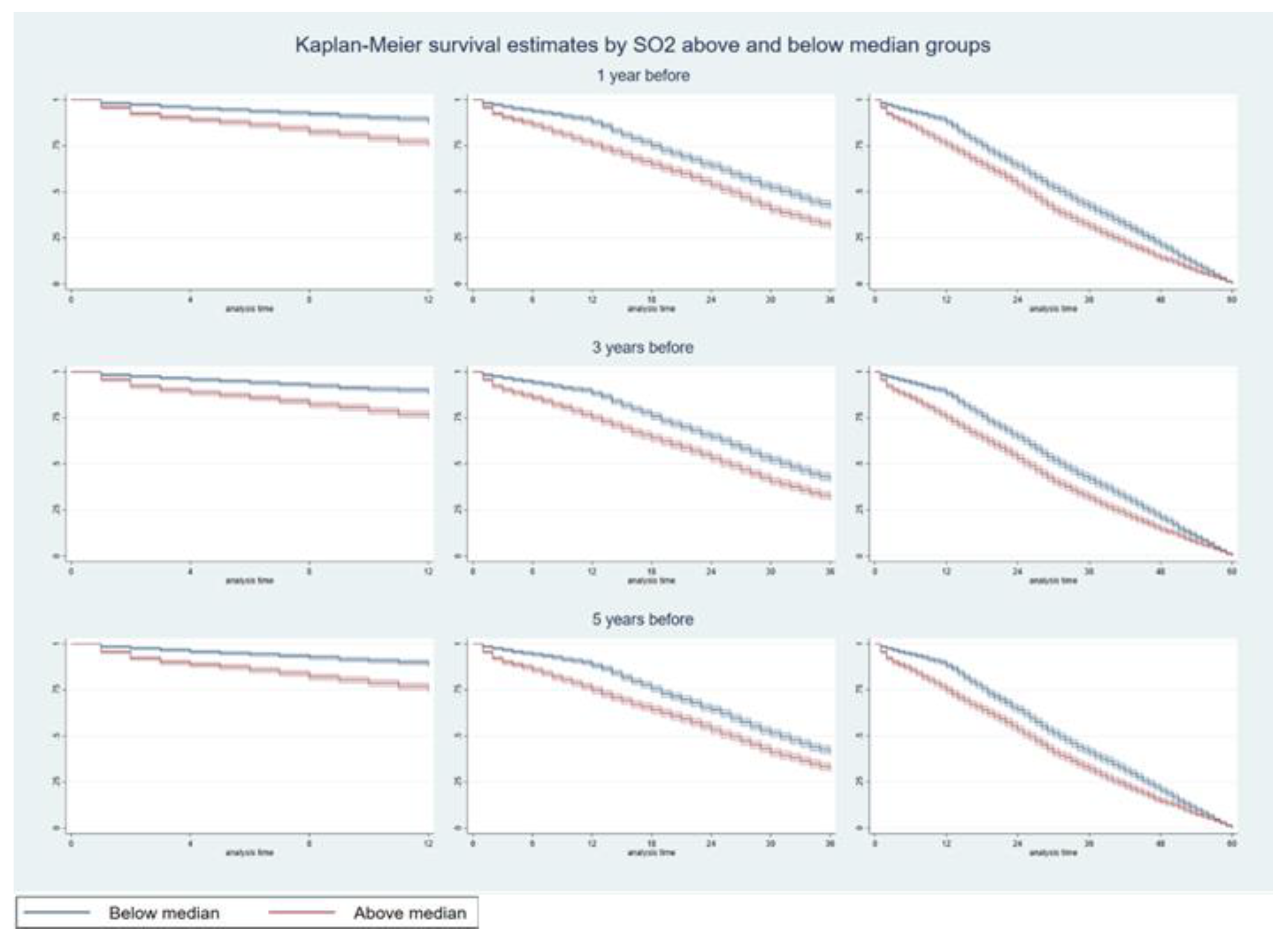

3. Results

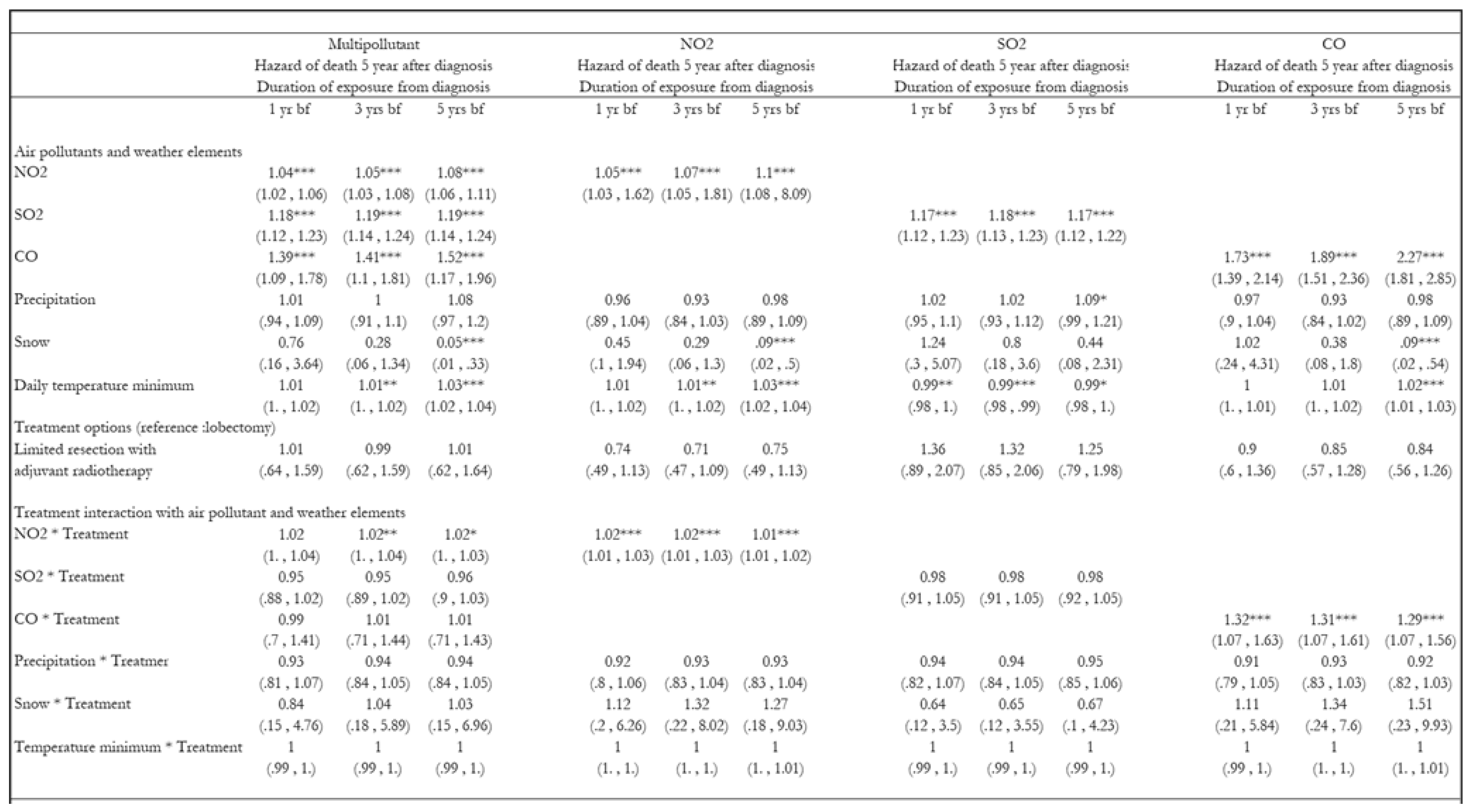

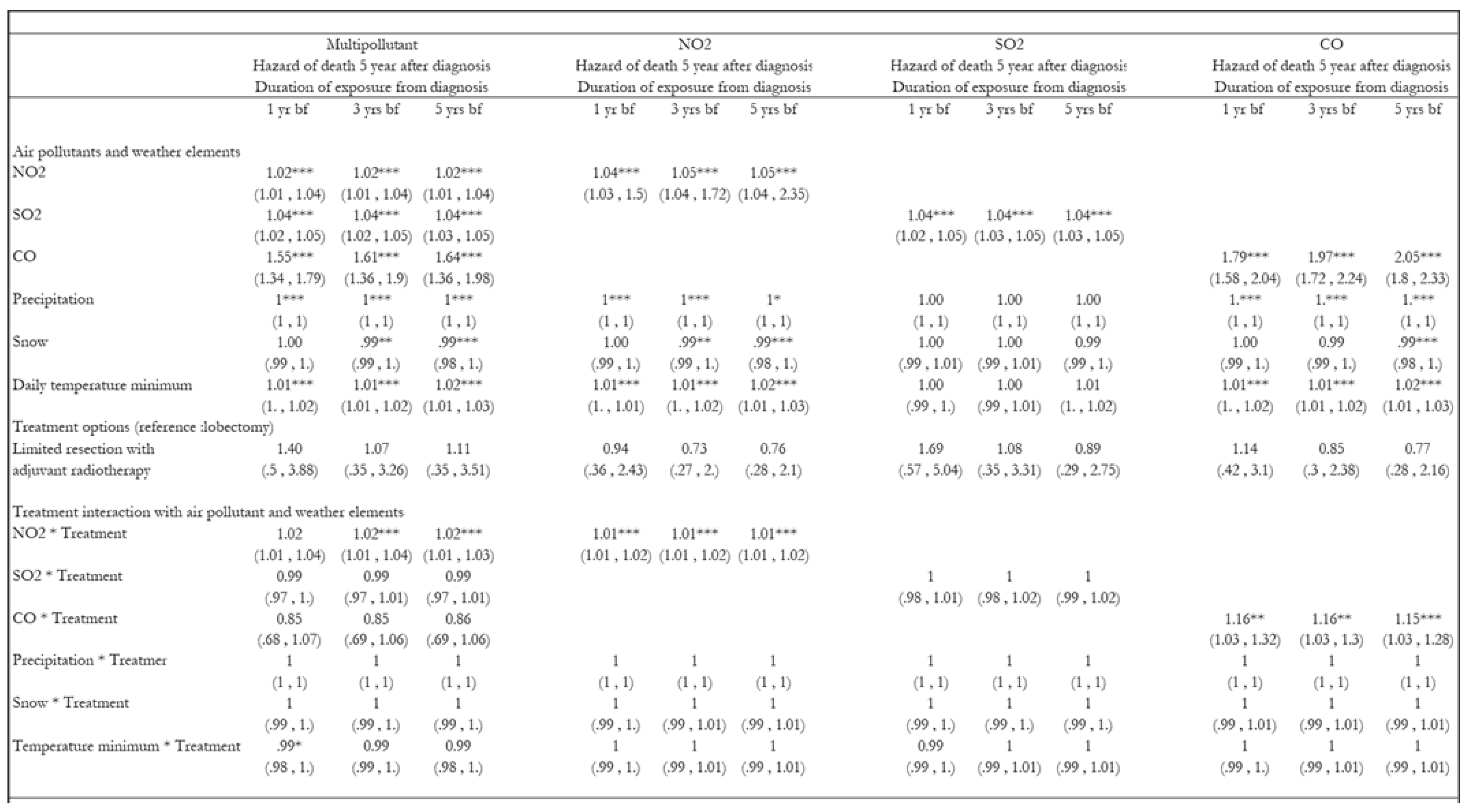

3.1. Hazards of Death Five Years After Diagnosis

4. Discussion

5. Implications for Practice and Policy

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

|

|

|

References

- Aksoy, M. 1980. “Different Types of Malignancies Due to Occupational Exposure to Benzene: A Review of Recent Observations in Turkey.” Environmental Research 23 1: 181–90. [CrossRef]

- Altorki, Nasser K, Xiaofei Wang, Dennis Wigle, Lin Gu, Gail Darling, Ahmad S Ashrafi, Rodney Landrenau, et al. 2019. “Perioperative Mortality and Morbidity after Lobar versus Sublobar Resection for Early Stage Lung Cancer: A Post-Hoc Analysis of an International Randomized Phase III Trial (CALGB/ Alliance 140503)” 6 (12): 915–24. [CrossRef]

- American Cancer Society. n.d. “Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Staging | Stages of Lung Cancer.” American Cancer Society. Accessed April 28, 2023. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/lung-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/staging-nsclc.html.

- “Area Health Resources Files.” n.d. Accessed July 13, 2024. https://data.hrsa.gov/topics/health-workforce/ahrf.

- Baig, Mirza Zain, Syed S. Razi, Joanna F. Weber, Cliff P. Connery, and Faiz Y. Bhora. 2020. “Lobectomy Is Superior to Segmentectomy for Peripheral High Grade Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer ≤2 Cm.” Journal of Thoracic Disease 12 (10): 5925–33. [CrossRef]

- Baxter, Lisa K, Kathie L Dionisio, Janet Burke, Stefanie Ebelt Sarnat, Jeremy A Sarnat, Natasha Hodas, David Q Rich, et al. 2013. “Exposure Prediction Approaches Used in Air Pollution Epidemiology Studies: Key Findings and Future Recommendations.” Journal of Exposure Science & Environmental Epidemiology 23 (6): 654–59. [CrossRef]

- Cao, Jinlin, Ping Yuan, Yiqing Wang, Jinming Xu, Xiaoshuai Yuan, Zhitian Wang, Wang Lv, and Jian Hu. 2018. “Survival Rates After Lobectomy, Segmentectomy, and Wedge Resection for Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer.” Annals of Thoracic Surgery 105 (5): 1483–91. [CrossRef]

- Eckel, Sandrah P., Myles Cockburn, Yu Hsiang Shu, Huiyu Deng, Frederick W. Lurmann, Lihua Liu, and Frank D. Gilliland. 2016a. “Air Pollution Affects Lung Cancer Survival.” Thorax 71 (10): 891–98. [CrossRef]

- Kates, Max, Scott Swanson, and Juan P Wisnivesky. 2011. “Survival Following Lobectomy and Limited Resection for the Treatment of Stage I Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer ≤ 1 Cm in Size: A Review of SEER Data.” CHEST 139 (3): 491–96. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Sun Young, Lianne Sheppard, and Ho Kim. 2009. “Health Effects of Long-Term Air Pollution: Influence of Exposure Prediction Methods.” Epidemiology 20 (3): 442–50. [CrossRef]

- Lamichhane, Dirga Kumar, Hwan-cheol Kim, Chang-min Choi, Myung-hee Shin, Young Mog Shim, Jong-han Leem, Jeong-seon Ryu, Hae-seong Nam, and Sung-min Park. 2017. “Lung Cancer Risk and Residential Exposure to Air Pollution : A Korean Population-Based Case-Control Study” 58 (6): 1111–18.

- Lee, Hung Chi, Yueh Hsun Lu, Yen Lin Huang, Shih Li Huang, and Hsiao Chi Chuang. 2022. “Air Pollution Effects to the Subtype and Severity of Lung Cancers.” Frontiers in Medicine 9 (March): 835026. [CrossRef]

- Lee, Kuan Ken, Rong Bing, Joanne Kiang, Sophia Bashir, Nicholas Spath, Dominik Stelzle, Kevin Mortimer, et al. 2020. “Articles Adverse Health Effects Associated with Household Air Pollution : A Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis, and Burden Estimation Study.” The Lancet Global Health 8 (11): e1427–34. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Changpeng, Dongjian Yang, Yuxi Liu, Heng Piao, Tao Zhang, Xi Li, Erjiang Zhao, Di Zhang, Yan Zheng, and Xiance Tang. 2023. “The Effect of Ambient PM2.5 Exposure on Survival of Lung Cancer Patients after Lobectomy.” Environmental Health: A Global Access Science Source 22 (1): 1–10.

- Liu, Cristina Su, Yaguang Wei, Mahdieh Danesh Yazdi, Xinye Qiu, Edgar Castro, Qiao Zhu, Longxiang Li, et al. 2023. “Long-Term Association of Air Pollution and Incidence of Lung Cancer among Older Americans: A National Study in the Medicare Cohort.” Environment International 181 (November): 108266. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Yansui, Yang Zhou, and Jiaxin Lu. 2020. “Exploring the Relationship between Air Pollution and Meteorological Conditions in China under Environmental Governance.” Scientific Reports 2020 10:1 10 (1): 1–11. [CrossRef]

- McKeon, Thomas P., Anil Vachani, Trevor M. Penning, and Wei Ting Hwang. 2022a. “Air Pollution and Lung Cancer Survival in Pennsylvania.” Lung Cancer 170 (June): 65–73. [CrossRef]

- Mery, Carlos M, Anastasia N Pappas, Raphael Bueno, Yolonda L Colson, Philip Linden, David J Sugarbaker, and Michael T Jaklitsch. 2005. “Similar Long-Term Survival of Elderly Patients with Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Treated with Lobectomy or Wedge Resection within the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Database.” Chest 128 (1): 237–45. [CrossRef]

- Moon, Da Hye, Sung Ok Kwon, Sun Young Kim, and Woo Jin Kim. 2020. “Air Pollution and Incidence of Lung Cancer by Histological Type in Korean Adults: A Korean National Health Insurance Service Health Examinee Cohort Study.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17 (3). [CrossRef]

- Ngarambe, Jack, Soo Jeong Joen, Choong Hee Han, and Geun Young Yun. 2021. “Exploring the Relationship between Particulate Matter, CO, SO2, NO2, O3 and Urban Heat Island in Seoul, Korea.” Journal of Hazardous Materials 403 (2): 123615. [CrossRef]

- Oji, Sunday, and Haruna Adamu. 2020. “Correlation between Air Pollutants Concentration and Meteorological Factors on Seasonal Air Quality Variation.” Journal of Air Pollution and Health 5 (1): 11–32. [CrossRef]

- “Overview of the SEER Program.” n.d. Accessed July 13, 2024. https://seer.cancer.gov/about/overview.html.

- Patel, Naiya, Seyed Karimi, Michael E. Egger, Bertis Little, and Demetra Antimisiaris. 2024. “Disparity in Treatment Receipt by Race and Treatment Guideline Revision Years for Stage 1A Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Patients in the US.” Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, June, 1–13.

- Pyo, Jung Soo, Nae Yu Kim, and Dong Wook Kang. 2022. “Impacts of Outdoor Particulate Matter Exposure on the Incidence of Lung Cancer and Mortality.” Medicina (Lithuania) 58 (9): 1–9.

- Raman, Vignesh, Oliver K. Jawitz, Marcelo Cerullo, Soraya L. Voigt, Kristen E. Rhodin, Chi-Fu Jeffrey Yang, Thomas A. D’Amico, David H. Harpole, Christopher R. Kelsey, and Betty C. Tong. 2022. “Tumor Size, Histology, and Survival After Stereotactic Ablative Radiotherapy and Sublobar Resection in Node-Negative Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer.” Annals of Surgery 276 (6): e1000–1007. [CrossRef]

- Razi, Syed S., Mohan M. John, Sandeep Sainathan, and Christos Stavropoulos. 2016. “Sublobar Resection Is Equivalent to Lobectomy for T1a Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer in the Elderly: A Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Database Analysis.” Journal of Surgical Research 200 (2): 683–89. [CrossRef]

- Rivera-González, Luis O., Zhenzhen Zhang, Brisa N. Sánchez, Kai Zhang, Daniel G. Brown, Leonora Rojas-Bracho, Alvaro Osornio-Vargas, Felipe Vadillo-Ortega, and Marie S. O’Neill. 2015. “An Assessment of Air Pollutant Exposure Methods in Mexico City, Mexico.” Journal of the Air & Waste Management Association (1995) 65 (5): 581. [CrossRef]

- Rueth, Natasha M, Helen M Parsons, Elizabeth B Habermann, Shawn S Groth, Beth A Virnig, Todd M Tuttle, Rafael S Andrade, Michael A Maddaus, and Jonathan D’Cunha. 2012. “Surgical Treatment of Lung Cancer: Predicting Postoperative Morbidity in the Elderly Population.” The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery 143 (6): 1314–23. [CrossRef]

- Sario, M. De, K. Katsouyanni, and P. Michelozzi. 2013. “Climate Change, Extreme Weather Events, Air Pollution and Respiratory Health in Europe.” European Respiratory Journal 42 (3): 826–43. [CrossRef]

- Shen, Jianfei, Weitao Zhuang, Congcong Xu, Ke Jin, Baofu Chen, Dan Tian, Crispin Hiley, Hiroshi Onishi, Chengchu Zhu, and Guibin Qiao. 2021. “Surgery or Non-Surgical Treatment of ≤8 Mm Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Population-Based Study.” Frontiers in Surgery 8 (May). [CrossRef]

- Shi, Leiyu. 2008. Health Services Research Methods. Thomson/Delmar Learning.

- Strickland, Matthew J, Katherine M Gass, Gretchen T Goldman, and James A Mulholland. 2015. “Effects of Ambient Air Pollution Measurement Error on Health Effect Estimates in Time-Series Studies: A Simulation-Based Analysis.” Journal of Exposure Science & Environmental Epidemiology 25 (2): 160–66. [CrossRef]

- Tian, Xueying, Kangping Cui, Hwey Lin Sheu, Yen Kung Hsieh, and Fanxuan Yu. 2021. “Effects of Rain and Snow on the Air Quality Index, PM2.5 Levels, and Dry Deposition Flux of PCDD/Fs.” Aerosol and Air Quality Research 21 (8): 210158. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Linlin, Lihui Ge, Sibo You, Yongyu Liu, and Yi Ren. 2022. “Lobectomy versus Segmentectomy in Patients with Stage T (> 2 Cm and ≤ 3 Cm) N0M0 Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Propensity Score Matching Study.” Journal of Cardiothoracic Surgery 17 (1): 110. [CrossRef]

- Wei, Yaguang, Xinye Qiu, Mahdieh Danesh Yazdi, Alexandra Shtein, Liuhua Shi, Jiabei Yang, Adjani A. Peralta, Brent A. Coull, and Joel D. Schwartz. 2022. “The Impact of Exposure Measurement Error on the Estimated Concentration-Response Relationship between Long-Term Exposure to PM2.5 and Mortality.” Environmental Health Perspectives 130 (7): 77006. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Xiaohui, Sandie Ha, Haidong Kan, Hui Hu, Barbara A. Curbow, and Claudia Tk Lissaker. 2013a. “Health Effects of Air Pollution on Length of Respiratory Cancer Survival.” BMC Public Health 13 (1): 1–9.

- Zanobetti, Antonella, and Annette Peters. 2015. “Disentangling Interactions between Atmospheric Pollution and Weather.” Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 69 (7): 613. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Zuofang, Guirong Xu, Qingchun Li, Conglan Chen, and Jiangbo Li. 2019. “Effect of Precipitation on Reducing Atmospheric Pollutant over Beijing.” Atmospheric Pollution Research 10 (5): 1443–53. [CrossRef]

| (a) | ||||||||||

| Above median | Below median | |||||||||

| Frequency | Percentage | Frequency | Percentage | |||||||

| Tumor Grade | ||||||||||

| Grade I | 262 | 12.02 | 484 | 22.20 | ||||||

| Grade II | 877 | 40.25 | 929 | 42.61 | ||||||

| Grade III | 835 | 38.32 | 564 | 25.87 | ||||||

| Grade IV | 30 | 1.38 | 16 | 0.73 | ||||||

| Unknown | 175 | 8.03 | 187 | 8.58 | ||||||

| Tumor size | ||||||||||

| Upto 1cm | 42 | 1.93 | 198 | 9.08 | ||||||

| > 1cm & < = 2cm | 208 | 9.55 | 820 | 37.61 | ||||||

| > 2cm | 189 | 8.67 | 643 | 29.50 | ||||||

| Unknown size | 1,740 | 79.85 | 519 | 23.81 | ||||||

| Treatment type | ||||||||||

| Only lobectomy | 1,951 | 89.54 | 1,815 | 83.26 | ||||||

| Limited resection with adjuvant | 228 | 10.46 | 365 | 16.74 | ||||||

| Rural-Urban Continuum | ||||||||||

| Large central metro | 1,333 | 61.17 | 1,138 | 52.20 | ||||||

| Large fringe metro | 536 | 24.60 | 801 | 36.74 | ||||||

| Medium metro | 285 | 13.08 | 195 | 8.94 | ||||||

| Non - metropolitan | 25 | 1.15 | 46 | 2.11 | ||||||

| Insurance type | ||||||||||

| Only Medicaid | 35 | 1.61 | 125 | 5.73 | ||||||

| Only Medicare | 166 | 7.62 | 823 | 37.75 | ||||||

| Only Private | 69 | 3.17 | 468 | 21.47 | ||||||

| Uninsured | 6 | 0.28 | 16 | 0.73 | ||||||

| Unknown | 1,903 | 87.33 | 748 | 34.31 | ||||||

| Race | ||||||||||

| Black | 288 | 13.22 | 228 | 10.46 | ||||||

| White | 1,773 | 81.37 | 1,759 | 80.69 | ||||||

| Unknown | 118 | 5.42 | 193 | 8.85 | ||||||

| Sex | ||||||||||

| Female | 969 | 44.47 | 1,226 | 56.24 | ||||||

| Male | 1,210 | 55.53 | 954 | 43.76 | ||||||

| Marital Status | ||||||||||

| Married | 1,280 | 58.74 | 1,239 | 56.83 | ||||||

| Widowed | 380 | 17.44 | 277 | 12.71 | ||||||

| Divorced | 247 | 11.34 | 284 | 13.03 | ||||||

| Single | 224 | 10.28 | 278 | 12.75 | ||||||

| Unknown | 48 | 2.20 | 102 | 4.68 | ||||||

| N | 2,179 | 2,180 | ||||||||

| (b) | ||||||||||

| Above median | Below median | |||||||||

| Median | Mean | SD | Median | Mean | SD | |||||

| Survival months | 27 | 28.11 | 17.61 | 30 | 31.09 | 15.93 | ||||

| Panel A: Exposure to air pollutants before and after diagnosis | ||||||||||

| N02 exposure (ppb) | 22.25 | 25.66 | 3.61 | 12.71 | 12.97 | 3.61 | ||||

| S02 exposure (ppb) | 4.10 | 3.98 | 1.20 | 1.56 | 1.81 | 1.20 | ||||

| CO exposure (ppb) | 816.75 | 1010.84 | 214.13 | 371.03 | 447.91 | 214.13 | ||||

| Panel B: Weather conditions before and after diagnosis | ||||||||||

| Precipitation | 24.06 | 26.07 | 8.76 | 22.41 | 23.34 | 10.93 | ||||

| Snow | 0.98 | 1.14 | 1.15 | 0.10 | 1.28 | 1.54 | ||||

| Daily minimum temperature | 76.04 | 75.90 | 17.66 | 82.80 | 81.92 | 18.01 | ||||

| Panel C: Individual-level characteristics | ||||||||||

| Age at diagnosis | 69 | 67.76 | 8.52 | 68 | 66.38 | 9.13 | ||||

| Panel D: County-level characteristics | ||||||||||

| Population estimates | 881,490 | 3,154,905 | 3,762,147 | 933,141 | 1,281,174 | 920,018 | ||||

| Unemployment rate | 59 | 63.70 | 24.39 | 45 | 48.85 | 34.63 | ||||

| Percapita income | 30496 | 32920.76 | 10118.93 | 47146 | 47803.63 | 15097.07 | ||||

| Total # hospitals | 16 | 45.68 | 54.17 | 13 | 14.09 | 9.35 | ||||

| Total # hospital beds | 3797 | 10169.78 | 11463.38 | 3130 | 3184.55 | 1979.29 | ||||

| N | 2,179 | 2,180 | ||||||||

| (a) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Multipollutant | NO2 | SO2 | CO | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hazard of death 5 years after diagnosis | Hazard of death 5 years after diagnosis | Hazard of death 5 years after diagnosis | Hazard of death 5 years after diagnosis | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Duration of exposure from diagnosis | Duration of exposure from diagnosis | Duration of exposure from diagnosis | Duration of exposure from diagnosis | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 yr bf | 3 yrs. bf | 5 yrs. bf | 1 yr bf | 3 yrs. bf | 5 yrs. bf | 1 yr bf | 3 yrs. bf | 5 yrs. bf | 1 yr bf | 3 yrs. bf | 5 yrs. bf | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Air pollutants and weather components | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| NO2 | 1.04*** | 1.06*** | 1.09*** | 1.06*** | 1.08*** | 1.11*** | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (1.02, 1.06) | (1.04, 1.08) | (1.06, 1.12) | (1.04 , 1.29) | (1.06 , 1.68) | (1.08 , 5.82) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| SO2 | 1.16*** | 1.17*** | 1.17*** | 1.15*** | 1.16*** | 1.15*** | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (1.12 , 1.21) | (1.13 , 1.22) | (1.12 , 1.21) | (1.11 , 1.2) | (1.12 , 1.21) | (1.1 , 1.19) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CO | 1.53*** | 1.51*** | 1.42** | 1.90*** | 2.07*** | 2.32*** | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (1.19 , 1.97) | (1.16 , 1.96) | (1.08 , 1.86) | (1.52 , 2.38) | (1.65 , 2.6) | (1.86 , 2.9) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Precipitation | 0.98** | 0.97*** | 0.97** | .98** | .98*** | 0.98 | 1 | 1 | 1 | .99* | .98** | 0.99 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| (0.97 , 1) | (0.95 , 0.99) | (0.95 , 1) | (.97 , 1.) | (.96 , .99) | (.96 , 1.01) | (.98 , 1.01) | (.98 , 1.01) | (.98 , 1.02) | (.97 , 1.) | (.96 , 1.) | (.97 , 1.01) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Snow | 0.99 | 0.96 | 0.90** | 0.94 | .88*** | .82*** | 1 | 1.01 | 0.99 | 1 | 0.94 | .88*** | ||||||||||||||||||||

| (0.92 , 1.07) | (0.88 , 1.05) | (0.82 , 0.99) | (.87 , 1.01) | (.81 , .96) | (.75 , .89) | (.93 , 1.08) | (.93 , 1.1) | (.9 , 1.08) | (.93 , 1.07) | (.87 , 1.03) | (.8 , .96) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Daily temperature minimum | 1.01 | 1.01** | 1.03*** | 1.01 | 1.01** | 1.03*** | .99** | .99** | 1 | 1.01 | 1.01 | 1.02*** | ||||||||||||||||||||

| (1 , 1.02) | (1 , 1.02) | (1.02 , 1.04) | (1. , 1.01) | (1. , 1.02) | (1.02 , 1.05) | (.99 , 1.) | (.98 , 1.) | (.99 , 1.01) | (1. , 1.01) | (1. , 1.02) | (1.01 , 1.03) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Treatment options (reference :lobectomy) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Limited resection with adjuvant radiotherapy | 0.95 | 0.89 | 0.97 | 0.70 | 0.63 | 0.67 | 1.34 | 1.24 | 1.14 | 0.93 | 0.79 | 0.75 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| (0.39 , 2.32) | (0.35 , 2.22) | (0.37 , 2.52) | (.31 , 1.57) | (.28 , 1.43) | (.29 , 1.54) | (.55 , 3.22) | (.5 , 3.08) | (.45 , 2.88) | (.4 , 2.16) | (.34 , 1.83) | (.32 , 1.72) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Treatment interaction with air pollutant and weather components | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| NO2 * Treatment | 1.01 | 1.02* | 1.02* | 1.01* | 1.01* | 1.01*** | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (1 , 1.03) | (1 , 1.03) | (1 , 1.03) | (1 , 1.02) | (1 , 1.02) | (1 , 1.02) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| SO2 * Treatment | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.99 | 1.02 | 1.02 | 1.02 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (0.93 , 1.04) | (0.93 , 1.04) | (0.93 , 1.05) | (0.97 , 1.07) | (0.98 , 1.07) | (0.97 , 1.06) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CO * Treatment | 0.94 | 0.85 | 0.86 | 1.16 | 1.24** | 1.36*** | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (0.68 , 1.29) | (0.60 , 1.21) | (0.60 , 1.22) | (0.95 , 1.43) | (1.04 , 1.48) | (1.16 , 1.60) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Precipitation * Treatment | 1 | 1.01 | 1.01* | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1 | 1.01* | 1.01** | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| (0.99 , 1.01) | (1 , 1.02) | (1 , 1.02) | (0.99 , 1) | (0.99 , 1.01) | (0.99 , 1.01) | (1 , 1.01) | (1 , 1.02) | (1 , 1.02) | (0.99 , 1.01) | (0.99 , 1.01) | (0.99 , 1) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Snow * Treatment | 1.10** | 1.14*** | 1.11** | 1.03 | 1.04 | 1.00 | 1.09** | 1.10** | 1.06 | 1.03 | 1.06 | 1.05 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| (1 , 1.2) | (1.03 , 1.25) | (1.01 , 1.23) | (0.96 , 1.10) | (0.97 , 1.12) | (0.93 , 1.07) | (1 , 1.18) | (1 , 1.2) | (0.97 , 1.17) | (0.95 , 1.12) | (0.98 , 1.14) | (0.97 , 1.13) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Temperature minimum * Treatment | 1.00 | 1.01* | 1.01* | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1.01** | 1.01** | 1.01* | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| (1 , 1.01) | (1 , 1.02) | (1 , 1.02) | (1 , 1.01) | (1 , 1.01) | (1 , 1.01) | (1 , 1.01) | (1 , 1.01) | (1 , 1.01) | (1 , 1.01) | (1 , 1.01) | (1 , 1.01) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| pvalue: * <0.1, ** <0.05, *** <0.01. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (b) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Multipollutant | NO2 | SO2 | CO | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hazard of death 5 year after diagnosis | Hazard of death 5 year after diagnosis | Hazard of death 5 year after diagnosis | Hazard of death 5 year after diagnosis | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Duration of exposure from diagnosis | Duration of exposure from diagnosis | Duration of exposure from diagnosis | Duration of exposure from diagnosis | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 yr bf | 3 yrs. bf | 5 yrs. bf | 1 yr bf | 3 yrs. bf | 5 yrs. bf | 1 yr bf | 3 yrs. bf | 5 yrs. bf | 1 yr bf | 3 yrs. bf | 5 yrs. bf | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Race (reference: Black) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other | 1 | 1 | 1.01 | 1.02 | 1.02 | 1.03 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 1.02 | 1.01 | 1.02 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| (.87 , 1.16) | (.86 , 1.15) | (.87 , 1.16) | (.88 , 1.18) | (.88 , 1.18) | (.89 , 1.19) | (.86 , 1.14) | (.85 , 1.13) | (.85 , 1.13) | (.88 , 1.17) | (.88 , 1.17) | (.88 , 1.18) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| White | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.99 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.97 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| (.88 , 1.07) | (.88 , 1.06) | (.88 , 1.07) | (.89 , 1.08) | (.89 , 1.08) | (.9 , 1.09) | (.87 , 1.06) | (.87 , 1.05) | (.86 , 1.05) | (.88 , 1.07) | (.88 , 1.07) | (.88 , 1.07) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Sex (reference: Female) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Male | 1.12*** | 1.12*** | 1.13*** | 1.12*** | 1.12*** | 1.13*** | 1.11*** | 1.11*** | 1.11*** | 1.12*** | 1.12*** | 1.12*** | ||||||||||||||||||||

| (1.05 , 1.19) | (1.05 , 1.19) | (1.06 , 1.2) | (1.05 , 1.19) | (1.06 , 1.19) | (1.06 , 1.2) | (1.04 , 1.17) | (1.04 , 1.18) | (1.04 , 1.18) | (1.05 , 1.19) | (1.05 , 1.19) | (1.05 , 1.19) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Tumor Grade (reference: II) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Grade III | 1.1*** | 1.1*** | 1.1*** | 1.09** | 1.09** | 1.09** | 1.12*** | 1.12*** | 1.12*** | 1.09** | 1.09** | 1.1** | ||||||||||||||||||||

| (1.02 , 1.19) | (1.02 , 1.19) | (1.02 , 1.19) | (1.01 , 1.18) | (1.01 , 1.17) | (1.01 , 1.18) | (1.04 , 1.2) | (1.04 , 1.2) | (1.04 , 1.2) | (1.01 , 1.18) | (1.02 , 1.18) | (1.02 , 1.18) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Grade IV | 1 | 0.99 | 1 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 1.01 | 1.01 | 1.02 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.95 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| (.72 , 1.39) | (.71 , 1.37) | (.72 , 1.39) | (.7 , 1.38) | (.69 , 1.36) | (.68 , 1.37) | (.72 , 1.41) | (.72 , 1.42) | (.72 , 1.42) | (.68 , 1.37) | (.67 , 1.35) | (.67 , 1.34) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Unknown | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.94 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| (.85 , 1.06) | (.85 , 1.05) | (.85 , 1.06) | (.85 , 1.06) | (.85 , 1.06) | (.85 , 1.06) | (.84 , 1.05) | (.84 , 1.05) | (.84 , 1.04) | (.85 , 1.05) | (.84 , 1.05) | (.84 , 1.04) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Grade I | 0.92** | 0.92** | 0.93** | 0.93* | 0.93* | 0.93* | 0.92** | 0.93** | 0.93* | 0.93* | 0.93* | 0.93* | ||||||||||||||||||||

| (.85 , 1.) | (.86 , 1.) | (.86 , 1.) | (.86 , 1.) | (.86 , 1.) | (.86 , 1.) | (.86 , 1.) | (.86 , 1.) | (.86 , 1.) | (.86 , 1.) | (.86 , 1.) | (.86 , 1.) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Marital status (reference: Divorced) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Married | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.97 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| (.88 , 1.05) | (.88 , 1.06) | (.88 , 1.06) | (.88 , 1.05) | (.88 , 1.06) | (.88 , 1.06) | (.86 , 1.04) | (.86 , 1.04) | (.86 , 1.04) | (.88 , 1.05) | (.88 , 1.06) | (.88 , 1.06) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Single | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.99 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.97 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| (.87 , 1.1) | (.87 , 1.1) | (.87 , 1.1) | (.87 , 1.1) | (.87 , 1.11) | (.88 , 1.11) | (.85 , 1.08) | (.85 , 1.07) | (.84 , 1.07) | (.85 , 1.08) | (.86 , 1.09) | (.86 , 1.09) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Unknown | 0.98 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 1 | 1 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.98 | 0.98 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| (.84 , 1.15) | (.85 , 1.16) | (.85 , 1.16) | (.84 , 1.16) | (.85 , 1.16) | (.85 , 1.16) | (.84 , 1.15) | (.83 , 1.15) | (.83 , 1.14) | (.83 , 1.14) | (.84 , 1.14) | (.84 , 1.14) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Widowed | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.98 | 0.98 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| (.87 , 1.1) | (.88 , 1.11) | (.88 , 1.12) | (.88 , 1.11) | (.88 , 1.11) | (.88 , 1.11) | (.85 , 1.08) | (.85 , 1.08) | (.86 , 1.08) | (.87 , 1.09) | (.87 , 1.1) | (.87 , 1.1) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Tumor size (reference: up to 1cm) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| >1cm & <=2cm | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 1 | 1 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 1.01 | 1.01 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| (.89 , 1.1) | (.89 , 1.1) | (.89 , 1.1) | (.9 , 1.11) | (.9 , 1.11) | (.89 , 1.1) | (.9 , 1.1) | (.89 , 1.09) | (.89 , 1.1) | (.91 , 1.12) | (.91 , 1.12) | (.9 , 1.11) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| >2cm | 1.02 | 1.02 | 1.02 | 1.02 | 1.02 | 1.02 | 1.02 | 1.01 | 1.02 | 1.03 | 1.02 | 1.03 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| (.91 , 1.14) | (.91 , 1.14) | (.91 , 1.15) | (.91 , 1.14) | (.91 , 1.14) | (.91 , 1.14) | (.91 , 1.14) | (.91 , 1.13) | (.91 , 1.13) | (.92 , 1.15) | (.92 , 1.15) | (.92 , 1.15) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Unknown | 0.87 | 0.85 | 0.81 | 0.88 | 0.86 | 0.8 | 0.84 | 0.82 | 0.81 | 0.76 | 0.75 | 0.75 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| (.49 , 1.55) | (.47 , 1.57) | (.45 , 1.47) | (.49 , 1.56) | (.47 , 1.57) | (.45 , 1.45) | (.48 , 1.47) | (.47 , 1.44) | (.46 , 1.42) | (.42 , 1.38) | (.41 , 1.39) | (.41 , 1.36) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Tumor histology (reference: squamous cell) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adenomas | 0.94 | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.94* | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.94* | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.93* | 0.93* | 0.93* | ||||||||||||||||||||

| (.87 , 1.01) | (.88 , 1.02) | (.88 , 1.02) | (.87 , 1.01) | (.87 , 1.01) | (.87 , 1.01) | (.87 , 1.01) | (.87 , 1.01) | (.87 , 1.01) | (.87 , 1.01) | (.87 , 1.01) | (.87 , 1.01) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Age at diagnosis | 1.01*** | 1.01*** | 1.01*** | 1.01*** | 1.01*** | 1.01*** | 1.01*** | 1.01*** | 1.01*** | 1.01*** | 1.01*** | 1.01*** | ||||||||||||||||||||

| (1 , 1.01) | (1 , 1.01) | (1 , 1.01) | (1 , 1.01) | (1 , 1.01) | (1 , 1.01) | (1 , 1.01) | (1 , 1.01) | (1 , 1.01) | (1 , 1.01) | (1 , 1.01) | (1 , 1.01) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Insurance type (reference: Only Medicaid) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Only Medicare | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.95 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.92 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| (.81 , 1.07) | (.81 , 1.08) | (.82 , 1.1) | (.82 , 1.08) | (.82 , 1.08) | (.82 , 1.09) | (.82 , 1.09) | (.82 , 1.09) | (.83 , 1.1) | (.8 , 1.06) | (.79 , 1.06) | (.8 , 1.06) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Only private | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.99 | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 1 | 0.99 | 1 | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.95 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| (.84 , 1.12) | (.84 , 1.12) | (.85 , 1.14) | (.84 , 1.11) | (.84 , 1.11) | (.84 , 1.12) | (.87 , 1.15) | (.86 , 1.14) | (.87 , 1.15) | (.82 , 1.09) | (.82 , 1.09) | (.82 , 1.1) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Uninsured | 1.27 | 1.31* | 1.35* | 1.17 | 1.19 | 1.22 | 1.22 | 1.23 | 1.22 | 1.15 | 1.17 | 1.2 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| (.92 , 1.76) | (.95 , 1.81) | (.98 , 1.86) | (.85 , 1.61) | (.87 , 1.64) | (.89 , 1.67) | (.89 , 1.68) | (.9 , 1.69) | (.89 , 1.68) | (.83 , 1.58) | (.86 , 1.61) | (.87 , 1.64) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Unknown | 1.05 | 1.07 | 1.11 | 0.93 | 0.96 | 0.99 | 1.07 | 1.09 | 1.11 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 1.02 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| (.8 , 1.37) | (.82 , 1.4) | (.84 , 1.45) | (.71 , 1.21) | (.73 , 1.25) | (.76 , 1.29) | (.83 , 1.39) | (.84 , 1.41) | (.86 , 1.44) | (.74 , 1.28) | (.75 , 1.29) | (.77 , 1.34) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Rural-Urban continuum (reference: Large central metro) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Large fringe metro | 0.84 | 0.93 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 1.16 | 1.24 | 0.57 | 0.55 | 0.62 | 0.86 | 0.91 | 0.95 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| (.26 , 2.67) | (.28 , 3.12) | (.28 , 3.56) | (.34 , 2.84) | (.4 , 3.38) | (.41 , 3.78) | (.19 , 1.72) | (.18 , 1.66) | (.2 , 1.89) | (.29 , 2.58) | (.3 , 2.8) | (.29 , 3.12) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Medium metro | 0.10*** | 0.07*** | 0.09*** | 0.11*** | 0.10*** | 0.14*** | 0.16*** | 0.15*** | 0.20*** | 0.12*** | 0.12*** | 0.20*** | ||||||||||||||||||||

| (.04 , .27) | (.03 , .2) | (.03 , .27) | (.04 , .3) | (.03 , .28) | (.05 , .42) | (.06 , .4) | (.06 , .4) | (.07 , .56) | (.05 , .31) | (.05 , .34) | (.07 , .58) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Non-metropolitan | 0.45* | 0.46 | 1.14 | 0.53 | 0.64 | 1.92 | 0.23*** | 0.24*** | 0.32** | 0.37** | 0.36** | 0.70 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| (.18 , 1.1) | (.17 , 1.21) | (.37 , 3.53) | (.21 , 1.29) | (.24 , 1.68) | (.64 , 5.82) | (.1 , .56) | (.09 , .61) | (.11 , .95) | (.15 , .87) | (.14 , .91) | (.24 , 2.02) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| pvalue: * <0.1, ** <0.05, *** <0.01 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).