1. Introduction

Natural compounds play a crucial role in disease treatment due to their diverse bioactive properties, including anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and anticancer effects [Newman DJ, Cragg GM., 2020; Spagnuolo L., 2021]. Their ability to modulate key biological pathways makes them valuable candidates for both conventional and adjunctive treatments [Dias, 2012]. In the cancer context, natural compounds are increasingly recognized for their role in promoting apoptosis, inhibiting proliferation, suppressing angiogenesis, altering cancer cell morphology, and modulating immune function [Nan Y, 2023]. Carotenoids, the most abundant natural pigments, are produced by photosynthetic organisms and some archaea, fungi, algae and animals [Maoka, 2020] and are classified as oxygen-free carotenes or oxygen-containing xanthophylls [Britton et al., 2004]. The reactive oxygen species (ROS)-scavenging ability of dietary carotenoids may help lower the risk of cancer and other diseases [Eggersdorfer and Wyss, 2018]. Specifically, xanthophylls have demonstrated diverse bioactive properties, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anti-angiogenic effects [Pereira AG, 2021]. Among xanthophylls, fucoxanthin, which is present in the macroalgae and microalgae, has been widely studied for its chemopreventive potential also in our lab [Méresse S, 2020; Calabrone, 2023] and has paved the way for investigating similar molecules. In the scenario of marine compounds, diatoms are emerging as promising bio-platforms for producing bioactive molecules for biomedical applications [Sansone et al., 2020; Sansone et al., 2021]. Diatoms produce the xanthophyll diatoxanthin (Dt), a pigment that plays an antioxidant role, protecting against high light damage [Smerilli et al., 2017, 2019; Serôdio et al., 2020], nutrient depletion [Beer et al., 2011], and viral attacks [Llewellyn et al., 2007]. Additionally, Dt regulates iron metabolism [Beer et al., 2011], particularly through ferroptosis, a type of regulated cell death triggered by oxidative stress, nutrient deprivation, and other cellular stresses [Beer et al., 2011; Pistelli, 2023]. To strengthen the knowledge about Dt chemopreventive action and its possible role in enhancing the effects of chemotherapy, we used cellular models of triple negative breast cancer (BC).

BC is the most prevalent cancer among women [Łukasiewicz S, 2021] and is a leading cause of cancer mortality worldwide [Wu Q, Siddharth S, 2021]. Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), which displays the poorest prognosis and the highest mortality rate, represents 15% of BC cases. TNBCs are characterized by the lack of expression of estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), making them unresponsive to hormone-based and HER2-targeted preventive therapies [Aysola K, 2013; Katsura et al., 2022; Hubalek M, 2017]. Treatment options for TNBC are limited [Mandapati A, 2023] and primarily rely on chemotherapy agents, such as doxorubicin and paclitaxel, which may be used in combination with approved biological therapies [Pareja et al., 2016; Collignon et al., 2016; Schmid et al., 2018; Raedler and Keytruda, 2015]. However, the systemic toxicity of chemotherapy and the development of drug resistance [Xiong N, 2024] underscore the urgent need for alternative or adjunctive therapeutic strategies [Barzaman et al., 2020]. Only recently PARP inhibitors and antibody drug conjugates are surfacing as novel therapeutics, anthracyclins being still a favorite option. A significant proportion of TNBC is associated with inherited mutations, especially BRCA1 mutations [Rejili M, 2025].

These characteristics make TNBC an optimal model for studying the potential chemopreventive and interceptionaction of natural compounds, as well as their ability to enhance responsiveness to chemotherapeutic agents.

This study explores Dt’s anti-tumor effects in TNBC models, focusing on its impact on cell viability, spheroid growth, angiogenesis, and inflammation, both as a standalone agent and combined with doxorubicin. Effects on endothelial cells were also exhamined. Modulation of gene expression by Dt has also been studied by RT PCR and further by RNAseq analysis.

Dt exhibited selective activity against MDA-MB-231 and BT-549 TNBC cells in inhibiting migration, chemotaxis, and suppressing 3D-tumor spheroid growth. Secretome analysis revealed that Dt-induced changes in inflammatory and angiogenic mediators, Dt also downregulated key pro-survival, proangiogenic and pro-tumorigenic genes in both TNBC cell lines and HUVEC, supporting its role in disrupting oncogenic pathways

Natural antioxidant compounds like Dt may offer cancer preventive potential and anti-tumor effects by targeting alternative molecular pathways or synergistic benefits when combined with chemotherapy by targeting alternative molecular pathways, as demonstrated for other similar molecules [Boța M, 2024].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture and Reagents

Human TNBC cell lines, MDA-MB-231 and BT-549, were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), and human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) from Lonza. MDA-MB-231 and BT-549 cells were cultured in DMEM (Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium) and RPMI 1640 medium, respectively, supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific™, Waltham, MA, USA), 2 mM L-glutamine, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Pen/Strep; Sigma-Aldrich®, St. Louis, MO, USA). HUVEC cells were grown in endothelial cell basal medium (EBM™, Lonza) enriched with endothelial cell growth medium (EGM™ SingleQuots™, Lonza), 10% FBS, 2 mM L-glutamine, and 1% Pen/Strep. These cells were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 and regularly screened for mycoplasma contamination.

Freeze-dried pure diatoxanthin was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich® (St. Louis, MO, USA) and subsequently dissolved in ethanol (EtOH). Doxorubicin was obtained from Selleck Chemicals (Houston, TX, USA), dissolved in water, and stored as a 10 mg/ml stock solution.

2.2. Viability Assays

Cell viability was evaluated using the MTT assay to determine dose-dependent effects on cellular proliferation. HUVEC and TNBC cells (5×103 cells/well) were seeded into 96-well plates and treated with diatoxanthin (Dt) at various concentrations (6.25–100 ng/μL) for 24, 48, and 72 h. Cell media containing ethanol (EtOH) served as a vehicle control to confirm that observed effects were attributable to Dt and not the solvent. Untreated cells (UT) were used as negative controls. For TNBC cells, a subsequent experiment, which combined Dt (25 ng/mL) with doxorubicin (Doxo) at concentrations of 0.1, 0.2, and 0.5 μM, was carried out to evaluate synergistic effects. Doxo alone (0.05–1 μM) was also tested, with no vehicle control for Doxo as its solvent is water. After treatment, cells were incubated with MTT (10 μL; 5 mg/mL stock) for 3 h at 37 °C. Formazan crystals were dissolved with 100% DMSO, and absorbance was measured at 570 nm using a SpectraMax® M2 spectrophotometer. All experiments were performed in triplicate, with eight technical replicates per condition.

2.3. Generation of 3D-Tumor Spheroids

3D-tumor spheroids were generated using a hanging drop method to replicate a physiologically relevant tumor microenvironment. MDA-MB-231 and BT-459 cells were cultured as 20 μL hanging drops at 4×103 cells/drop in complete DMEM or RPMI medium, respectively. Spheroids were grown under five conditions: untreated (UT), culture medium supplemented with ethanol (Crt) as ethanol is the solvent of Dt, Doxo (0.5 μM), Dt (25 ng/mL), and Doxo+Dt. The EtOH concentration in Dt treatments matched the solvent control. After spheroid formation (within 24 h), spheroids were transferred to 96-well plates (one spheroid/well) coated with 2% agar in fresh medium, with treatments refreshed every 48 h. Growth was monitored over 12 days, and images were acquired at days 3, 6, and 12. Spheroid area was measured using ImageJ software and normalized to day 3. Diameter was calculated from the area using d= √(4A/π). Only one Doxo concentration (0.5 μM) was used due to challenges in the 3D-culture technique. Necrotic regions, prominent in Doxo and Doxo+Dt treatments, were excluded from diameter calculations.

2.4. Boyden Chamber Assay

The migration ability of MDA-MB-231 and BT-549 TNBC cells was assessed using a modified Boyden chamber assay. Cells were synchronized by overnight incubation in starvation DMEM or RPMI 1640 medium, then seeded (4×104 cells/well) into the upper chamber with starvation medium containing Dt (25 ng/μL) or EtOH (Crt). A fibronectin-coated (2 μg/mL) 10 μm pore-size polycarbonate filter separated the upper and lower chambers. The lower chamber contained DMEM or RPMI 1640 with 10% FBS to establish a chemoattractant gradient. Positive controls used serum-free medium in the upper chamber and complete medium in the lower chamber, while negative controls used serum-free medium in both chambers. After 6 h at 37 °C and 5% CO2, non-migrated cells were removed from the upper filter surface. The filter was washed, fixed in 4% PFA for 10 min at RT, stained with crystal violet, and imaged using a Zeiss™ Axio Observer A1 microscope with a digital camera at 10× magnification. Each experimental condition was repeated four times, with three fields per filter imaged and analyzed. Migration was quantified by averaging cell counts across fields and replicates. Image analysis was performed using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). The experiment was repeated three times.

2.5. Scratch Wound Healing Migration Assay

The anti-migratory effect of Dt (25 ng/mL) on MDA-MB-231 and BT-549 TNBC cells was evaluated using a scratch wound assay. Cells (5×104/well) were seeded in 12-well plates and incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 until confluence. A ~1 mm-wide scratch was made using a micropipette tip, and monolayers were washed twice with PBS to remove debris. Cells were then incubated in 1% FBS medium containing Dt (25 ng/mL). Images of the scratch area were taken at t0 and after 24 h using a Leica™ DM IL LED inverted microscope with a digital camera at 4× magnification. Wound closure was assessed by measuring the uncovered area at both time points. To quantify migration, the uncovered and migrated cell-covered areas were color-coded in Adobe Photoshop® and analyzed with ImageJ software. The percentage of area covered by migrated cells after 24 h was calculated relative to the initial uncovered area at t0. Each experimental condition was repeated four times, with images of three fields acquired per well. The mean covered area for each condition was calculated across replicates in three independent experiments. Doxo or Doxo+Dt treatments were excludede form this assay due to rapid cell death under low-serum conditions (1% FBS).

2.6. RNA Extraction and Gene Expression Profiling by qPCR

Quantitative PCR assessed the expression of genes involved in inflammation, angiogenesis, and tumor progression. MDA-MB-231 and BT-549 TNBC cells (1×106) were seeded onto p100 plates. Upon reaching 80–90% confluence, cells were treated with Dt (25 ng/μL) for 6 h. HUVEC (2.5×105 cells/well) were seeded in 6-well plates, adhered, and treated with Dt (25 ng/μL) in fresh medium for 6 h. Control cells (Ctr) received a complete medium supplemented with the same concentration of ethanol that is present in the solvent of the Dt dose used for treatment. Untreated cells (UT) received complete medium. Total RNA was extracted following standard protocols. RNA was isolated using the TRIzol method and RNA concentration was determined with a Nanodrop™ Spectrophotometer. cDNA was synthesized using 1000 ng of RNA and the SuperScript™ VILO™ cDNA synthesis kit. qPCR was performed with SYBR Green Master Mix on a QuantStudio™ 6 Flex System, with reactions conducted in triplicate and repeated three times. Primers were designed using NCBI Primer BLAST (details in Supplementary Table S1) and purchased from IDT. Data collected over 40 cycles were analyzed with MeV Software.

2.7. Secretome Analysis

The proteomic profile of the secretome from HUVEC, MDA-MB-231 and BT-459 cells was quantitatively analyzed using the RayBio™ Human Cytokine Antibody Array 3 and RayBiotech® Human Angiogenesis Antibody Array (RayBiotech Life, GA, USA). In brief, the antibody array membranes were first incubated with blocking buffer for 1 hour, followed by an overnight incubation at 4 °C with 1 mL of secretome from the different cell lines (2000 µg/mL). After thorough washing, the membranes were treated with a biotinylated antibody cocktail for 2 hours at room temperature under constant shaking. This was followed by a 2-hour incubation with HRP-streptavidin at room temperature. The membranes were then developed using the chemiluminescent detection reagent provided in the kit acquiring images after different periods of exposure.

2.8. RNAseq

Total RNA (totRNA) was isolated from cell lines using the miRNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. DNase treatment was carried out with the Turbo DNA-free Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), and RNasin® Plus RNase Inhibitor (Promega, Madison, WI) was added to HUVEC samples to prevent RNA degradation. RNA quality and quantity were assessed using the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) and a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). A total of 500 ng of totRNA was used to prepare RNA libraries with the Stranded mRNA Prep, Ligation Kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA), following the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, the mRNA fraction was purified via polyA capture, fragmented, and subjected to first-strand cDNA synthesis using reverse transcriptase and random primers. Second-strand synthesis was performed incorporating dUTP instead of dTTP to ensure strand specificity. A- and T-bases were added to the fragment ends, index adapters were ligated, and cDNA was amplified via PCR. Library quality was validated using the Agilent Bioanalyzer (DNA 1000 Kit), and concentrations were measured with the Qubit™ dsDNA BR Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Libraries were normalized, multiplexed, and sequenced on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 system using the NovaSeq 6000 S1 Reagent Kit v1.5 (Illumina, San Diego, CA).

BCL files were converted to FASTQ format and demultiplexed using bcl2fastq v2.20.0.422. Quality control of raw reads was performed with FastQC v0.11.9. Adapters and low-quality reads were trimmed using Cutadapt v2.8, and the processed reads were aligned to the Human Reference Genome GRCh38.99 using STAR v2.7, following index creation from the corresponding FASTA file. Read quantification was performed using FeatureCounts v2.0. Differential expression analysis was conducted using the DESeq2 package (

https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/DESeq2.html), which normalized raw count data, estimated biological variance, and identified differentially expressed genes between experimental conditions. Volcano plots were generated using the

ggplot R package, to display differentially expressed genes (absolute fold change > 1.5 and adjusted p-value<0.05). Functional enrichment analysis was performed with DAVID (

https://david.ncifcrf.gov/), and heatmaps were created using the

heatmap R package.

2.9. Statistical Analysis

Data from experiments with at least three technical replicates per treatment were analyzed using GraphPad Prism™ software and reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Differences between treatments were evaluated using one-way ANOVA, with statistical significance set at p<0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Dt Selectively Reduces Viability in TNBC Cells

Dt was preliminalry tested on HUVEC cells to determine a concentration that did not induce cytotoxicity in this cell type. Concentrations between 6.25 ng/mL and 25 ng/mL did not significantly affect HUVEC viability at 48 or 72 h compared to non-treated cells. However, Dt at 50 ng/mL significantly reduced cell viability at both 48 h (p<0.01) and 72 h (p<0.01), with a more pronounced effect observed at 100 ng/mL. No significant differences in viability were detected between cells treated with medium containing the solvent ethanol (Ctr)at the same dilution and non-treated cells (NT) at either timepoint, confirming that the observed effects were attributable to Dt (

Figure 1). Dt significantly reduced cell viability in MDA-MB-231 and BT-549 cells at concentrations ≥12.5 ng/mL, with maximal effects observed at 25 ng/mL (

Figure 1). These results underscore the potential Dt’s selective antiproliferative activity toward cancer cells.

The combination of Dt (25 ng/mL) with the chemotherapeutic agent Doxo was evaluated for potential additive effects against TNBC cell lines MDA-MB-231 and BT-549. Cell viability was assessed using the MTT assay following treatment with increasing concentrations of Doxo (0.05–1 μM) alone or in combination with Dt. Co-treatment with Dt enhanced the cytotoxic effects of Doxo in both TNBC cell lines. For MDA-MB-231 cells, combined treatment with Dt significantly reduced cell viability compared to Doxo alone at 0.1 μM (*p<0.05), 0.2 μM (***p<0.001), and 0.5 μM (*p<0.05,

Figure 2A). Similarly, for BT-549 cells, an additive effect was observed at 0.1 μM (**p<0.01), 0.2 μM (***p<0.001), and 0.5 μM (**p<0.01,

Figure 2B).

3.2. Analysis of Dt and Doxo Effects on 3D-Tumor Spheroid Growth

The impact of Dt (25 ng/mL) and Doxo (0.5 μM) on the 3D-tumor spheroid growth of TNBC cell lines (MDA-MB-231 and BT-549) was assessed at 3, 6, and 12 days post-treatment. Dt alone did not significantly affect spheroid size, while Doxo reduced spheroid growth at all time points. Combined Dt and Doxo treatment demonstrated an additive effect, further reducing spheroid size and increasing morphological instability compared to Doxo alone (

Figure 3A,B). Crystal violet assays performed at day 12 confirmed these findings, with Dt alone slightly reducing cell viability (p<0.05) and the combined treatment showing a more pronounced reduction in viability (MDA-MB-231, p<0.0001; BT-549, p<0.001), indicating a potential additive effect (

Figure 3C).

3.3. Dt Reduces TNBC Cell Migration

Transwell Migration Assay

The results of the transwell migration assay were comparable for both TNBC cell lines analyzed.

Figure 4A,B illustrate a reduction in cell migration in Dt (25 ng/mL)-treated cells compared to the control (Ctr) and this reduction was confirmed as significant by statistical analyses.

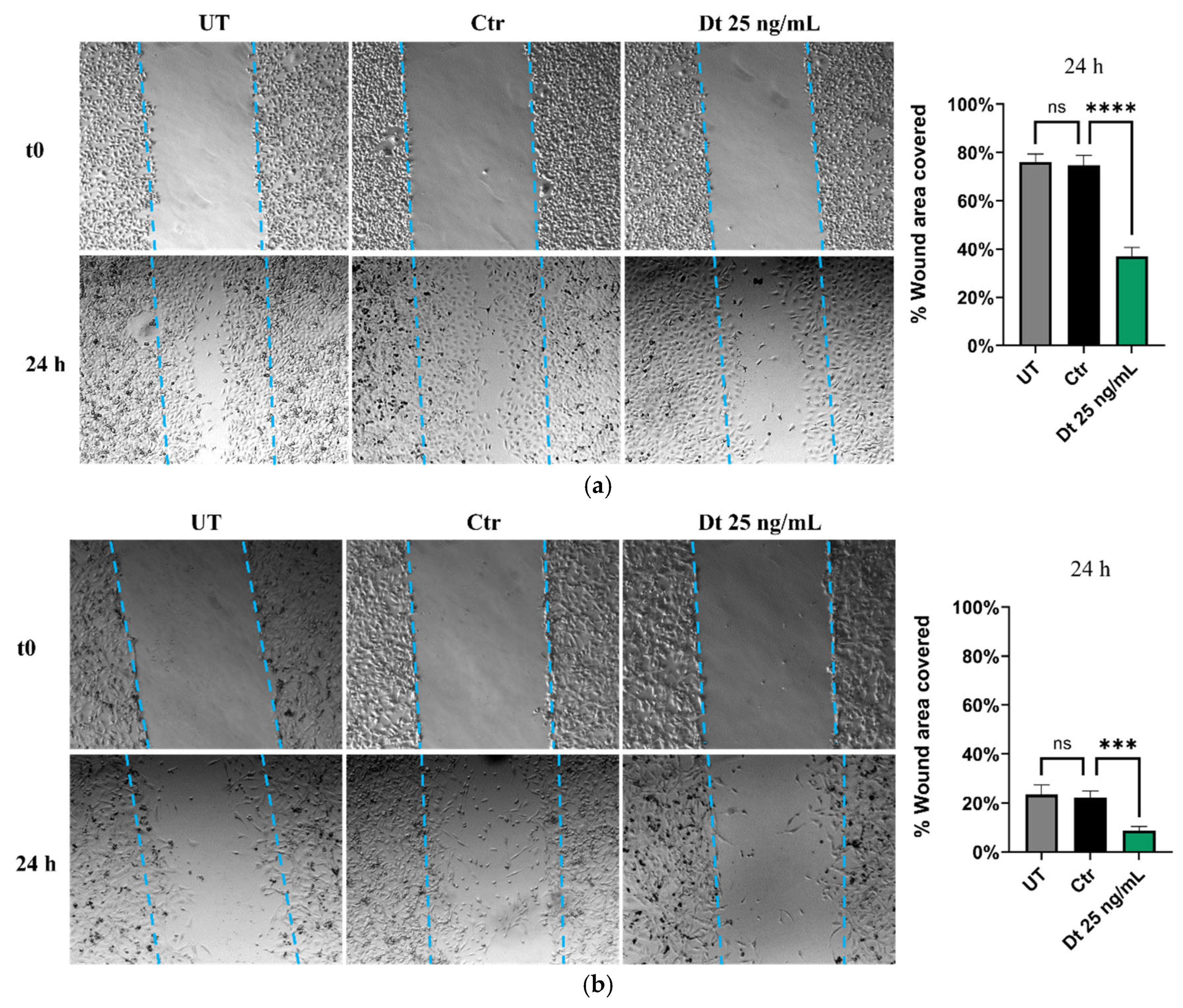

3.4. Scratch Wound Healing Migration Assay

The wound healing assay was performed under three conditions: non-treated (NT) cells, Dt-treated cells, and vehicle control cells. Both TNBC cell lines exhibited a similar trend. After 24 hours of treatment, Dt-treated cells showed a pronounced reduction in the wound-covered area compared to the control. This is depicted in the panels on the right in

Figure 5A,B, which highlight a significant decrease in the percentage of wound area covered by Dt-treated cells relative to solvent control cells. These findings suggest a potential role for Dt in reducing the migratory capacity of these TNBC cell lines.

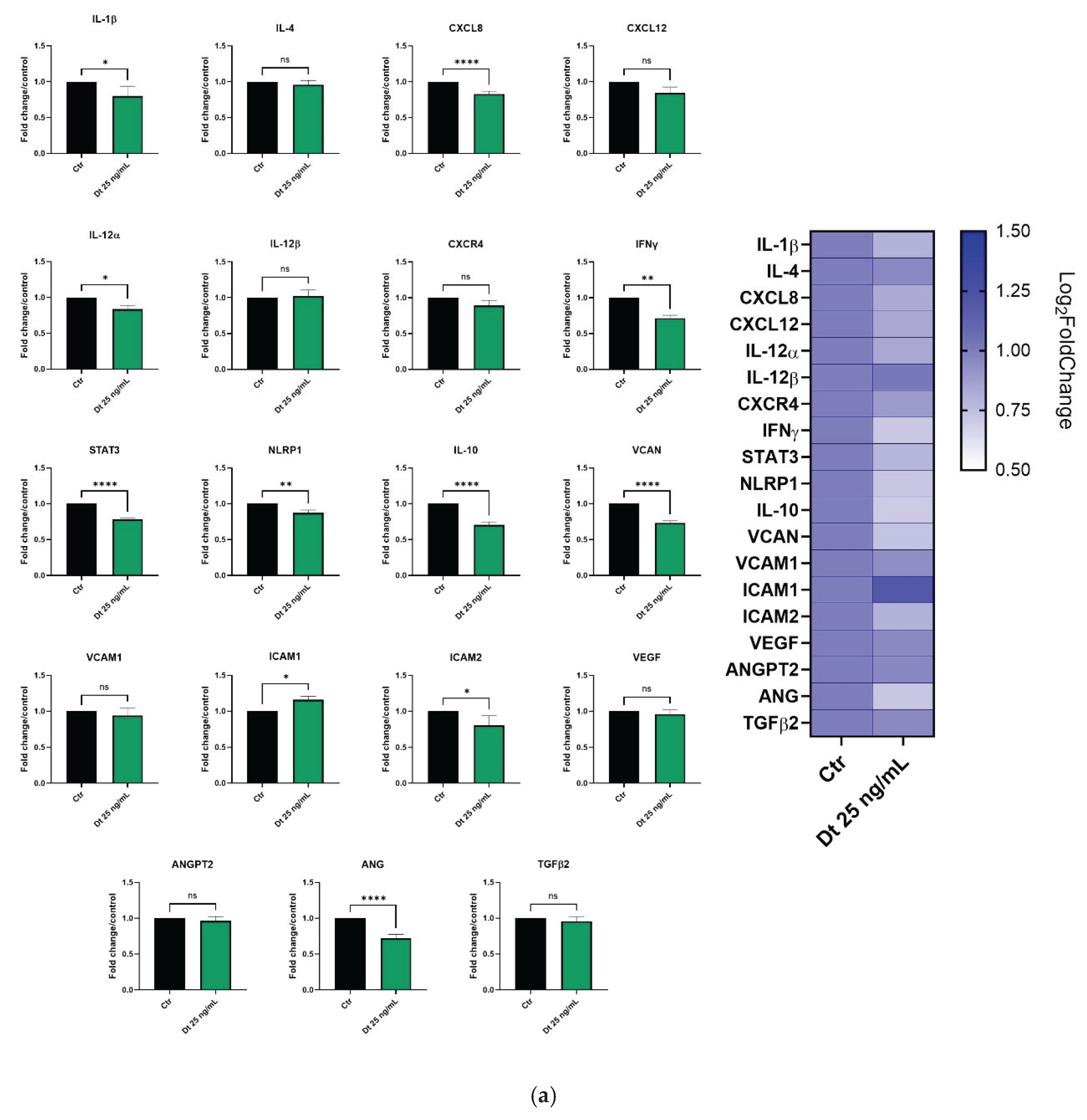

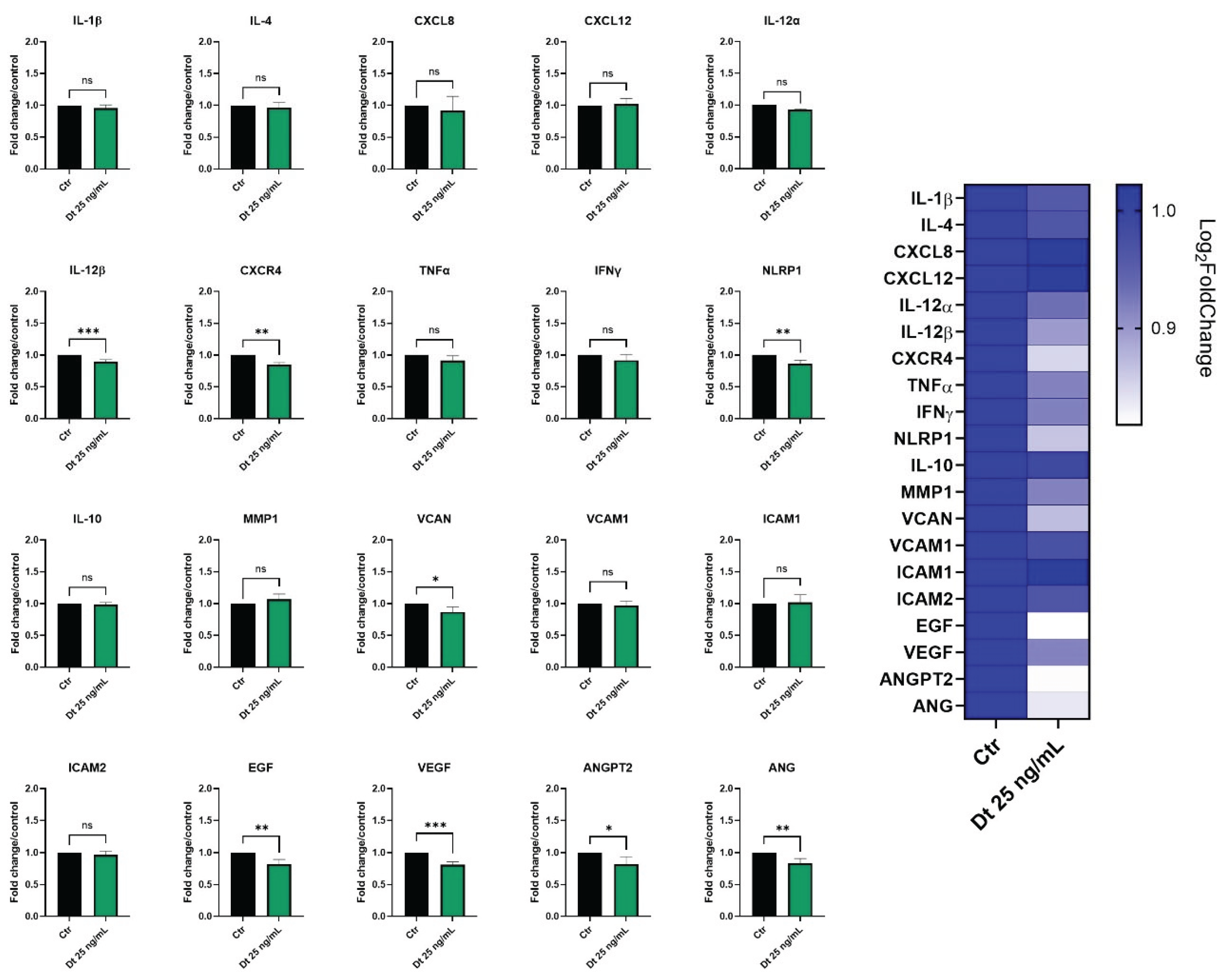

3.5. Effect of Dt on Gene Expression in the MDA-MB-231 and BT-549 TNBC Cell Lines

Gene expression profiling in the MDA-MB-231 and BT-549 TNBC cell lines was evaluated after 6 hours of treatment with Dt (25 ng/mL).

In MDA-MB-231 cells (

Figure 6A), important pro-inflammatory mediators as IL-1β, CXCL8, IL-12α, IFNγ, and STAT3 were significantly downregulated by Dt. Furthermore, although not statistically significant, the treatment with Dt slightly decreased the expression of other important inflammation mediators such as IL-4, CXCL-12, and CXCR4. In addition, Dt treatment showed an effect on angiogenesis-related genes (VCAM, VCAN, VEGF, ANGPT2, ANG) by downregulating their expression. ts effect on ANG and VCAN expression seems to be particularly evident.

In BT-549 cells (

Figure 6B), Dt treatment led to a decrease of IL-12β, IFN-γ, IL-10, VCAN, and TGF-β, while its effect on the other tested genes appears milder compared to the MDA-MB-231 cell line. Nevertheless, despite the slight not significative down modulation in some genes, an anti-inflammatory and anti-angiogenic trend appears clear in gene expression profile (

Figure 6).

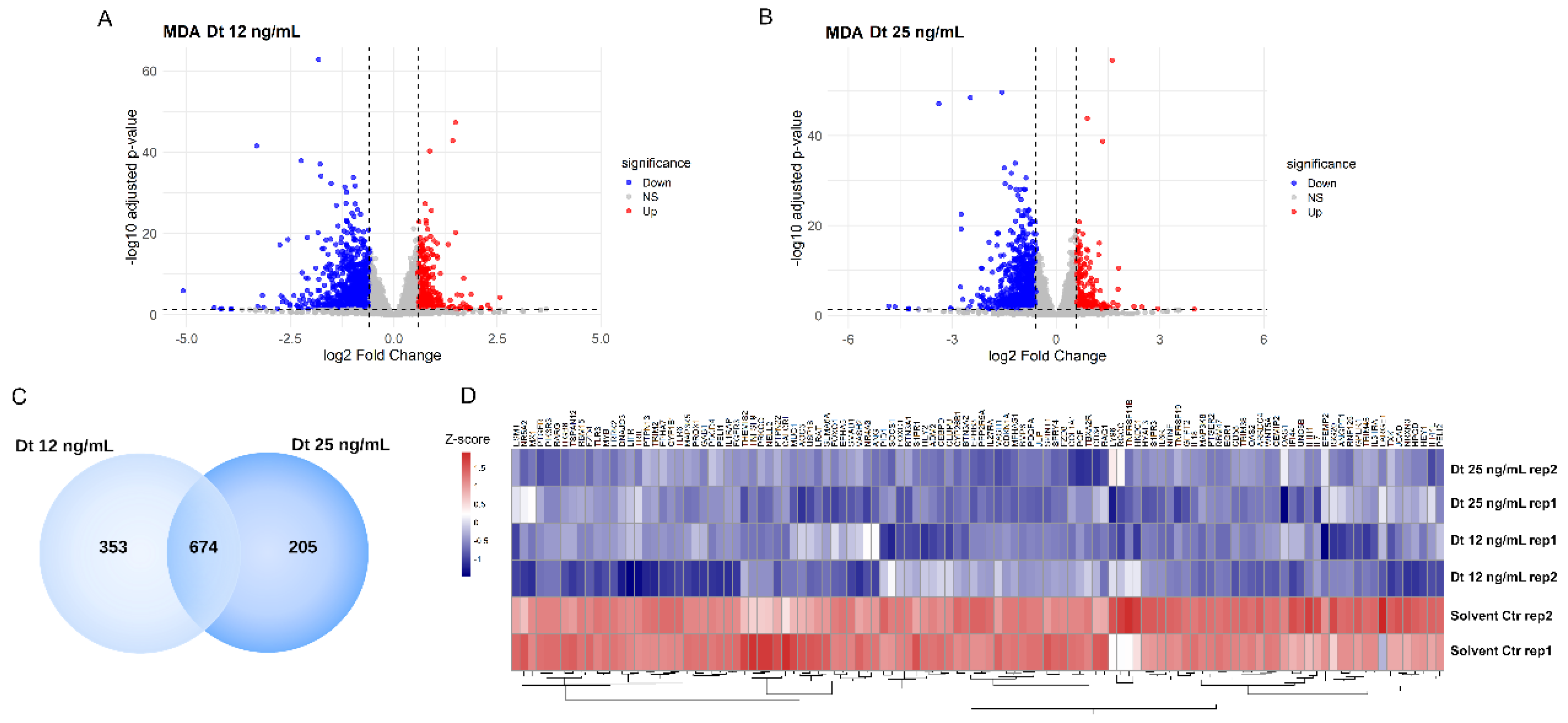

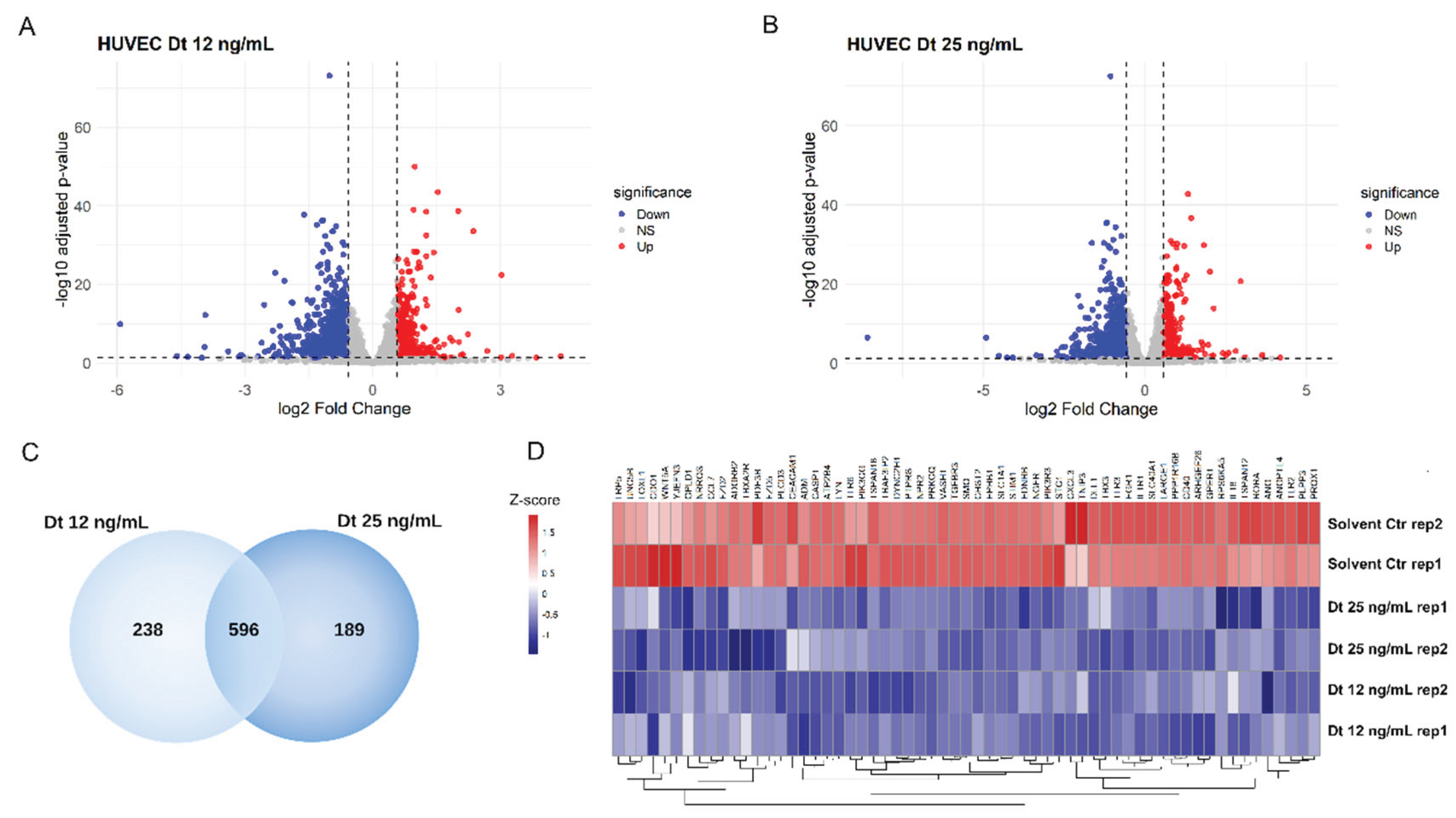

3.6. RNA-Seq Transcriptome Analysis in MDA-MB-231 Cells

The global transcriptomic changes induced by Dt treatment were analyzed by RNA-sequencing. The number of downregulated transcripts compared with medium control containing the solvent at the same dilution than the carotenoid treatment is more abundant than the number of upregulated transcripts, by both Dt 12 mg/mL (

Figure 7A) and Dt 25 mg/mL (

Figure 7B) treatments. Functional enrichment analysis using the 674 commonly downregulated genes (

Figure 7C) revealed modulation of biological processes related with blood vessel development and morphogenesis, regulation of angiogenesis, Cytokine Signaling in Immune system, inflammatory response.. These genes include ANGPT1, GPR37, ANG, QRICH2, and MUC1, as well as IL-6 receptor (IL-6R) and IL-7 (

Figure 7D).

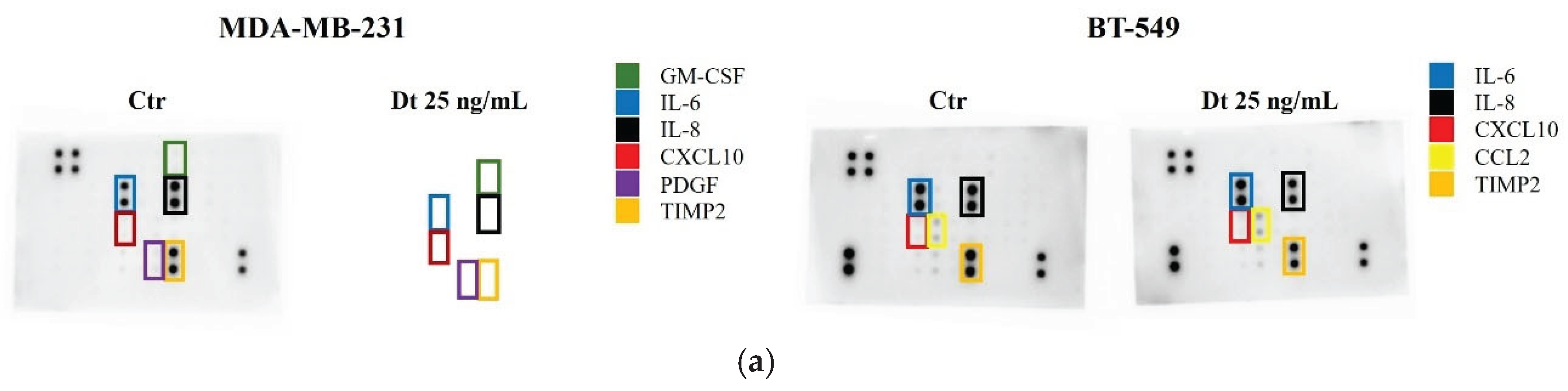

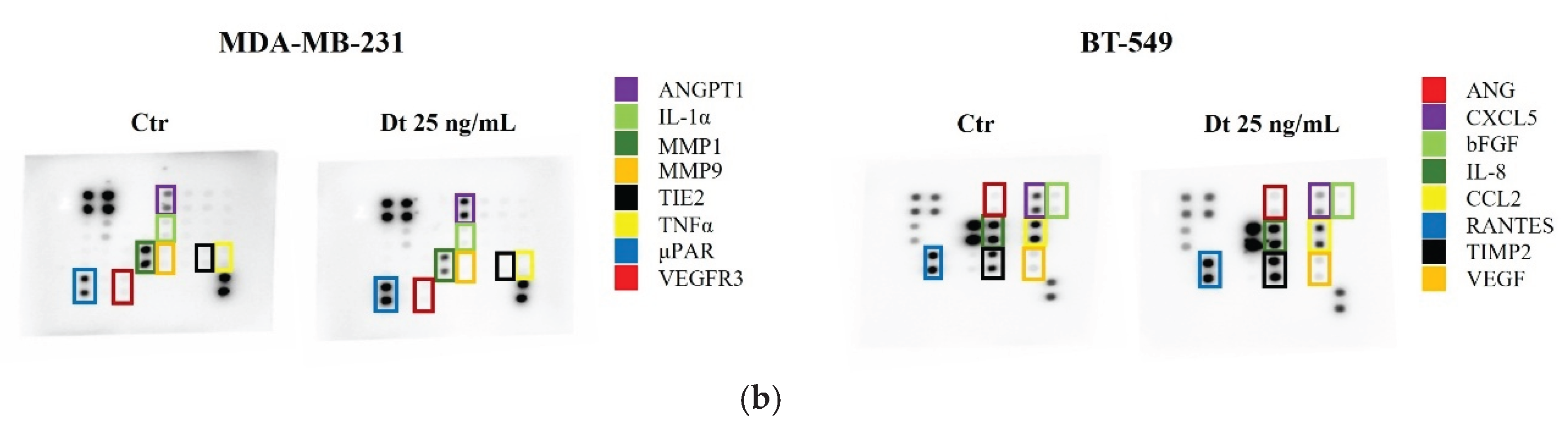

3.7. Secretome Analysis Using RayBiotech® Human Inflammation Antibody Array and Human Angiogenesis Antibody Array

Secretome changes, particularly in inflammatory mediators and angiogenic factors, were evaluated in MDA-MB-231 and BT-549 TNBC cell lines treated with Dt (25 ng/mL). Dt treatment showed a marked decreae in the amount of TIMP-2 protein released in the secretome of the MDA-MB-231, although its effect on other inflammatory mediators was relatively mild (

Figure 8A). Notably, a more evident effect was clear in the analysis of the Angiogenesis Antibody Array,where Dt seemed to decrease the levels of MMP-1, MMP-9 and TNFα (

Figure 8B). In BT-549 cells, Dt did not show effect in modulating inflammatory mediators released in the secretome (

Figure 8A), while it caused a slight reduction of CXCL5, visible in the Angiogenesis Array (

Figure 8B). These findings suggest minor changes in angiogenesis inflammatory mediators also at protein level.

3.8. Effect of Dt on Gene Expression in HUVEC Cells

The effects of Dt (25 ng/mL) on TNF-α-stimulated HUVEC gene expression were assessed by qPCR after 6 hours of treatment. As shown in

Figure 9, Dt caused a significant downregulation of some neo-angiogenesis-related genes, including VEGF, EGF, VCAN, ANGPT2, and ANG. Among inflammation-associated genes, TNFa, IFNg, CXCR4, NLRP1 and IL-12β showed a significant decrease in expression (

Figure 9). MMP1 was also decreased.

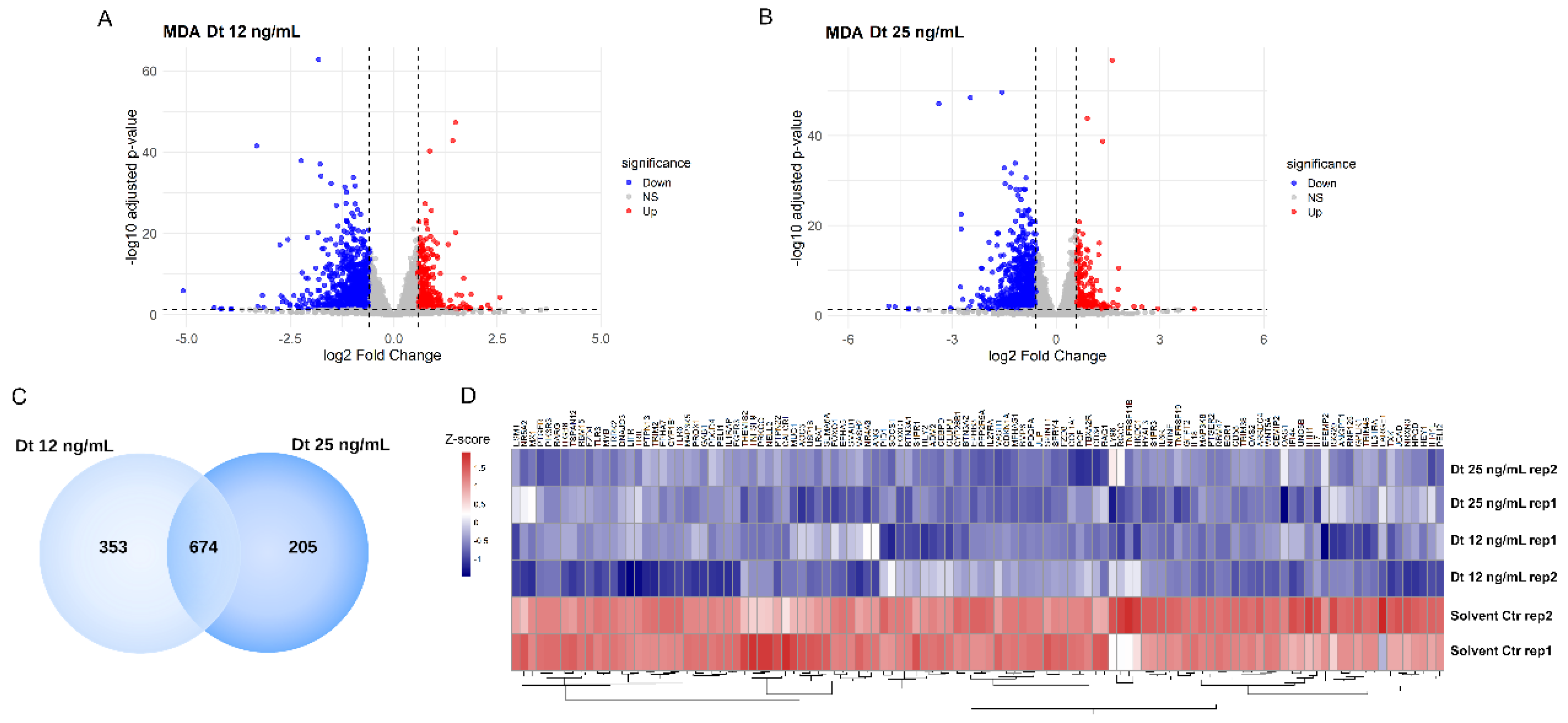

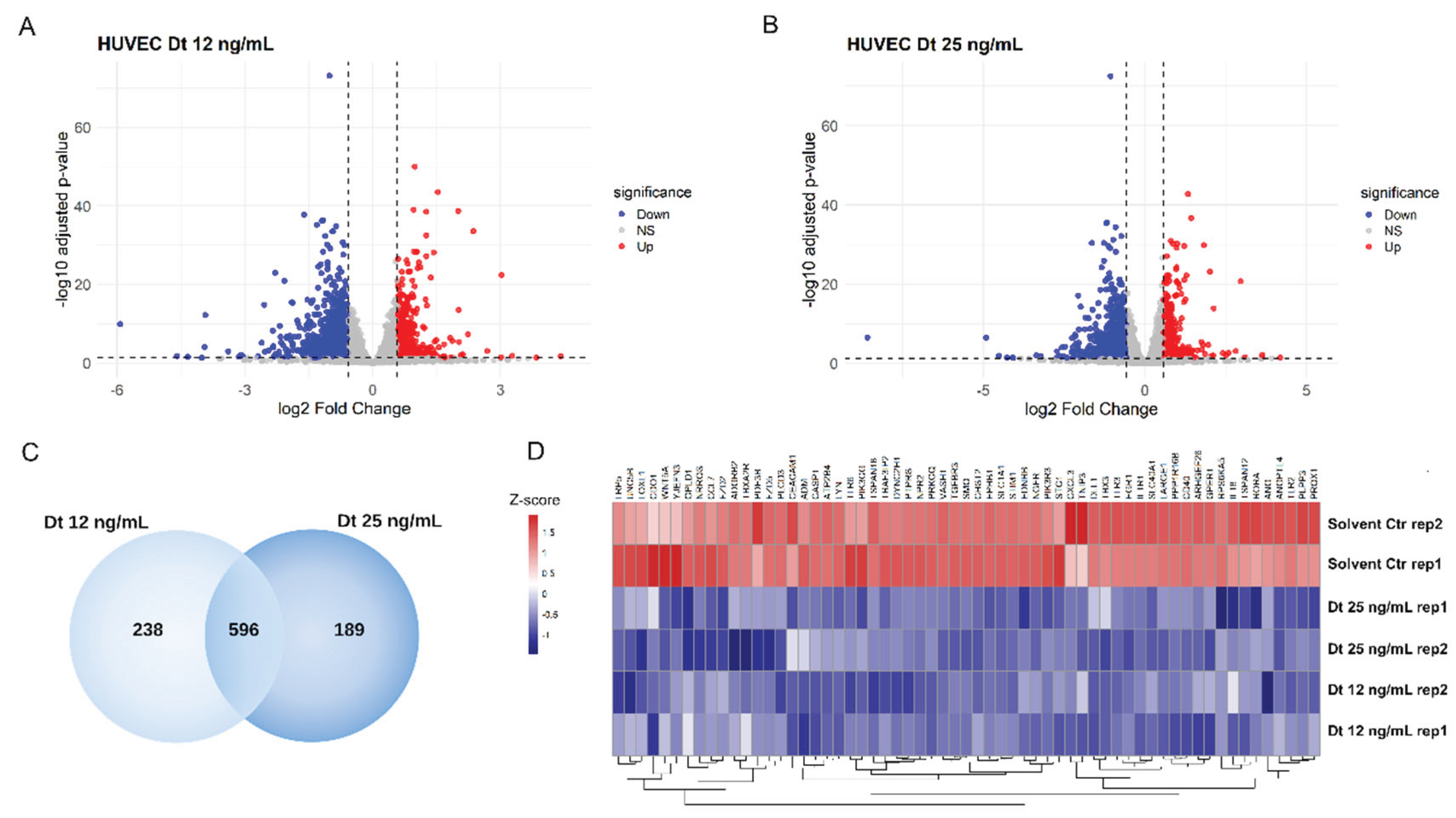

3.9. RNA-Seq Transcriptome Analysis in HUVEC Cells

Functional enrichment analysis identified on the list of genes whose expression was significantly downregulated in HUVEC cells by Dt treatment at both 12 ng/ml and 25 ng/ml concentrations (

Figure 10) compared to TNFα-treated HUVECs evidenced that they participate in key pathways regulating vascular development, endothelial function, and angiogenesis. These findings suggest that Dt’s primary effect was the suppression of TNFα-induced pro-angiogenic transcription.

4. Discussion

The use of natural compounds in cancer therapy has garnered significant attention due to their diverse bioactive properties, lower toxicity profiles, and ability to target multiple hallmarks of cancer [Nan Y, 2023]. Among these, marine-derived compounds have emerged as a particularly promising class, owing to the unique chemical structures and bioactivities of molecules synthesized in marine environments [Karthikeyan A, 2022; Chénais B, 2021; Romano B, 2023]. Carotenoids such as xanthophylls have demonstrated potent antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anti-tumor properties, including activity as ferroptosis inducer, with several showing promise in preclinical cancer models [Sansone, 2020; Sansone, 2021; Sansone, 2025]. Diatoxanthin, a xanthophyll pigment produced by diatoms, represents a novel marine compound with therapeutic potential [Sansone, 2023]. Given the challenges of Triple Negative Breast Cancer, such as limited treatment options, systemic toxicity of chemotherapy, and drug resistance [Mandapati A, 2023; Xiong N, 2024], this cancer type represents an optimal model to study the chemopreventive potential of natural compounds like Dt and their ability to enhance chemotherapy efficacy [Barzaman et al., 2020]. Besides this, since there is a strong rationale that supports the exploring Dt’s anti-cancer properties in other malignancies, the use of TNBC cell lines would deepen the knowledge about Dt’s role in cancer treatment.

Our findings demonstrate that Dt selectively reduces TNBC cell viability (MDA-MB-231 and BT-549 cell lines) while sparing healthy endothelial cells (HUVEC). This selectivity is critical for minimizing off-target effects associated with conventional chemotherapies. The observed cytotoxic effects align with the role of Dt in inducing prostate cancer cell death [Sansone, 2023]. Notably, the combined treatment of Dt and Doxorubicin significantly enhanced anti-proliferative effect of the chemotherapy, in fact cell viability was further reduced in both TNBC cell lines compared to Doxo alone and 3D-tumor spheroid growth was significantly suppressed, with increased morphological instability observed in the combined treatment. Interestingly, both transwell migration and scratch wound healing assays revealed that Dt significantly inhibits TNBC cell motility, suggesting that Dt may target distinct molecular pathways regulating migration, which warrants further investigation.This is a crucial finding, given that TNBC is highly metastatic.

Dt downregulated key inflammatory mediators (CXCL8/IL-8, IL-1β, IL-4, IL-12, STAT3, IFNγ, NLRP1) as well as endothelial–tumor crosstalk genes (e.g., VCAN, VCAM1/ICAM1, VEGF/VEGFA, ANG/ANGPT2). These signatures are highly relevant in TNBC, where IL-6/JAK/STAT and chemokine networks sustain pro-angiogenic VEGF output and metastatic behavior.

Beyond these pathways, Dt also reduced cytokines linked to metastasis. IL-10, associated with TNBC bone metastasis, declined with Dt treatment, supporting an anti-metastatic effect [Chen M, Wu C, 2022]. Likewise, TGF-β, another pro-metastatic cytokine, was significantly decreased in BT-549 cells after Dt exposure, suggesting additional potential to curb metastatic processes [Yousafzai NA, El Khalki L, 2024]. Dt’s modulation of these axes could mitigate pro-tumor inflammation and dissemination [Liubomirski Y, 2019]. Secretome analyses corroborated these findings: pro-tumorigenic and angiogenic proteins (VEGFR3, ANGPT1, EGF) and matrix remodelers, such as matrix metalloproteases, were reduced.

Transcriptomic profiling aligned with these results. In MDA-MB-231 cells, Dt downregulated genes involved in angiogenesis and tumor progression, including ANGPT1, ANG, GPR37, QRICH2, and MUC1, as well as IL-6R and IL-7. In TNF-α–stimulated HUVECs, Dt suppressed angiogenesis-related genes (NOS3, DLL1, PPP1R16B, ADGRA2, NPR1). At the protein level, Dt-treated HUVECs also showed decreased Angiostatin, MMP-9, IL-2, and IL-4. Collectively, these data suggest that Dt exerts anti-angiogenic and anti-inflammatory effects in both tumor cells and the endothelial compartment of the tumor microenvironment, raising the prospect of limiting inflammation-driven angiogenesis and tumor progression.

Dt’s multifaceted anti-tumor activities, ranging from selective cytotoxicity and inflammation modulation to angiogenesis inhibition and migration suppression, pose it as a promising therapeutic candidate in TNBC. The observed synergy with Doxo in reducing TNBC cell proliferation suggests that Dt could serve as an effective adjuvant, enhancing chemotherapy efficacy while minimizing adverse effects. This finding would be crucial, but further investigation is needed to shed light on the potential adjuvant role of Dt.

Moreover, Dt’s natural origin and established antioxidant properties make it a potential candidate for integration into dietary or pharmacological strategies for cancer prevention and management, following the path laid out by its sibling molecule, fucoxanthin, already commercially available as a dietary supplement. [Leonard M, 2023]. This study provides in vitro insights of Dt’s potential against TNBC cells, further investigations are needed for possible clinical applications. Dt’s impact on endothelial cells within the tumor microenvironment represents an interesting feature. Investigating Dt’s effects across other TNBC subtypes and cancer models may reveal its broader therapeutic relevance and potential for combinatorial strategies with other chemotherapeutic agents or immunotherapies.

5. Conclusions

The antioxidant xanthophyll Dt demonstrates significant potential as a natural agent against TNBC and its anti-proliferative activities enhanced the ones of doxorubicin. The ability of this natural antioxidant to selectively target cancer cells, modulate inflammation and angiogenesis and decrese the migration capacity, with gene expression modulation demonstrated by RT PCR and RNAseq analysis offers a novel, multifaceted approach to addressing the challenges associated with aggressive TNBC subtypes. Future research should focus on translating these findings into preclinical and clinical contexts, paving the way for innovative treatment strategies in oncology.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: A.A. Formal analysis: Experimental activity DM, LC, GC, PO, Writing of the orignal draft: all. Methodology: AA, D.M. Writing, review & editing AA LDP and GC: all Funding acquisition: GC and A.A. Revision and approval of the final version of the manuscript: all.

Funding

This research was funded by Drugs and Vaccines from the Sea (ADViSE)” project (PG/2018/0494374) to Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn. Adriana Albini was also supported by a donation from “Fattoria La Vialla di Gianni, Antonio e Bandino Lo Franco—SAS” (Castiglion Fibocchi, Arezzo, Italy) for the project entitled “Studi sulle proprietà degli estratti di acque di vegetazione dell’olio di oliva. Approfondimenti di prevenzione e nutraceutica” granted by the IEO-MONZINO Foundation and IRCCS IEO (A.A.). Additional support was provided by the Italian Ministry of Health Ricerca Corrente–IRCCS IEO and IRCCS MultiMedica.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Lara Vecchi, Aashni Shah and Massimiliano Pianta (Polistudium srl, Milan Italy) for editorial assistance, language editing and graphic support.

Conflicts of Interest

Luana Calabrone is affiliated with ISB Ion Source & Biotechnologies Srl. There are no commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest related to this affiliation.

References

- Aysola, K; Desai, A; Welch, C; Xu, J; Qin, Y; Reddy, V; Matthews, R; Owens, C; Okoli, J; Beech, DJ; Piyathilake, CJ; Reddy, SP; Rao, VN. Triple negative breast cancer - an overview. Hereditary Genet. 2013, 2013 Suppl 2, 001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barzaman, K; Karami, J; Zarei, Z; Hosseinzadeh, A; Kazemi, MH; Moradi-Kalbolandi, S; Safari, E; Farahmand, L. Breast cancer: Biology, biomarkers, and treatments. Int Immunopharmacol. 2020, 84, 106535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beer, A; Juhas, M; Büchel, C. INFLUENCE OF DIFFERENT LIGHT INTENSITIES AND DIFFERENT IRON NUTRITION ON THE PHOTOSYNTHETIC APPARATUS IN THE DIATOM CYCLOTELLA MENEGHINIANA (BACILLARIOPHYCEAE)(1). J Phycol. 2011, 47(6), 1266–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boța, M; Vlaia, L; Jîjie, AR; Marcovici, I; Crişan, F; Oancea, C; Dehelean, CA; Mateescu, T; Moacă, EA. Exploring synergistic interactions between natural compounds and conventional chemotherapeutic drugs in preclinical models of lung cancer. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2024, 17(5), 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Britton, G; Liaaen-Jensen, S; Pfander, H. Main List. In Carotenoids; Britton, G, Liaaen-Jensen, S, Pfander, H, Eds.; Springer, 2004; pp. 35–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrone, L; Carlini, V; Noonan, DM; Festa, M; Ferrario, C; Morelli, D; Macis, D; Fontana, A; Pistelli, L; Brunet, C; Sansone, C; Albini, A. Skeletonema marinoi extracts and associated carotenoid fucoxanthin downregulate pro-angiogenic mediators on prostate cancer and endothelial cells. Cells 2023, 12(7), 1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S; Behnam Azad, B; Nimmagadda, S. The intricate role of CXCR4 in cancer. Adv Cancer Res. 2014, 124, 31–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M; Wu, C; Fu, Z; Liu, S. ICAM1 promotes bone metastasis via integrin-mediated TGF-β/EMT signaling in triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer Sci. 2022, 113(11), 3751–3765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chénais, B. Algae and microalgae and their bioactive molecules for human health. Molecules (Base) 2024, 26(4), 1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collignon, J; Lousberg, L; Schroeder, H; Jerusalem, G. Triple-negative breast cancer: treatment challenges and solutions. Breast Cancer (Dove Med Press) 2016, 8, 93–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, DA; Urban, S; Roessner, U. A historical overview of natural products in drug discovery. Metabolites 2012, 2(2), 303–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggersdorfer, M; Wyss, A. Carotenoids in human nutrition and health. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2018, 652, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubalek, M; Czech, T; Müller, H. Biological Subtypes of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Breast Care (Basel) 2017, 12(1), 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthikeyan, A; Joseph, A; Nair, BG. Promising bioactive compounds from the marine environment and their potential effects on various diseases. J Genet Eng Biotechnol. 2022, 20(1), 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katsura, C; Ogunmwonyi, I; Kankam, HK; Saha, S. Breast cancer: presentation, investigation and management. Br J Hosp Med (Lond) 2022, 83(2), 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonard, M; Maury, J; Dickerson, B; Gonzalez, DE; Kendra, J; Jenkins, V; Nottingham, K; Yoo, C; Xing, D; Ko, J; Pradelles, R; Faries, M; Kephart, W; Sowinski, R; Rasmussen, CJ; Kreider, RB. Effects of Dietary Supplementation of a Microalgae Extract Containing Fucoxanthin Combined with Guarana on Cognitive Function and Gaming Performance. Nutrients 2023, 15(8), 1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liubomirski, Y; Lerrer, S; Meshel, T; Rubinstein-Achiasaf, L; Morein, D; Wiemann, S; Körner, C; Ben-Baruch, A. Tumor-stroma-inflammation networks promote pro-metastatic chemokines and aggressiveness characteristics in triple-negative breast cancer. Front Immunol. 2019, 10, 757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llewellyn, Carole A.; Evans, Claire; Airs, Ruth L.; Cook, Isobel; Bale, Nicole; Wilson, William H. The response of carotenoids and chlorophylls during virus infection of Emiliania huxleyi (Prymnesiophyceae). J Experiment Mar Biol Ecol 2007, 344(1), 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łukasiewicz, S; Czeczelewski, M; Forma, A; Baj, J; Sitarz, R; Stanisławek, A. Breast cancer-epidemiology, risk factors, classification, prognostic markers, and current treatment strategies-an updated review. Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13(17), 4287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandapati, A; Lukong, KE. Triple negative breast cancer: approved treatment options and their mechanisms of action. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2023, 149(7), 3701–3719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maoka, T. Carotenoids as natural functional pigments. J Nat Med. 2020, 74(1), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méresse, S; Fodil, M; Fleury, F; Chénais, B. Fucoxanthin, a Marine-Derived Carotenoid from Brown Seaweeds and Microalgae: A Promising Bioactive Compound for Cancer Therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2020, 21(23), 9273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nan, Y; Su, H; Zhou, B; Liu, S. The function of natural compounds in important anticancer mechanisms. Front Oncol. 2023, 12, 1049888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman, DJ; Cragg, GM. Natural products as sources of new drugs over the nearly four decades from 01/1981 to 09/2019. J Nat Prod. 2020, 83(3), 770–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pareja, F; Geyer, FC; Marchiò, C; Burke, KA; Weigelt, B; Reis-Filho, JS. Triple-negative breast cancer: the importance of molecular and histologic subtyping, and recognition of low-grade variants. NPJ Breast Cancer 2016, 2, 16036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, AG; Otero, P; Echave, J; Carreira-Casais, A; Chamorro, F; Collazo, N; Jaboui, A; Lourenço-Lopes, C; Simal-Gandara, J; Prieto, MA. Xanthophylls from the Sea: Algae as Source of Bioactive Carotenoids. Mar Drugs 2021, 19(4), 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pistelli, L; Del Mondo, A; Smerilli, A; Corato, F; Sansone, C; Brunet, C. Biotechnological response curve of the cyanobacterium Spirulina subsalsa to light energy gradient. Biotechnol Biofuels Bioprod 2023, 16(1), 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raedler, LA. Keytruda (Pembrolizumab): First PD-1 inhibitor approved for previously treated unresectable or metastatic melanoma. Am Health Drug Benefits Spec Feature. 2015, 8, 96–100. [Google Scholar]

- Romano, B; Maresca, DC; Somma, F; Ahmadi, P; Putra, MY; Rahmawati, SI; Chianese, G; Formisano, C; Ianaro, A; Ercolano, G. Ircinia ramosa Sponge Extract (iSP) Induces Apoptosis in Human Melanoma Cells and Inhibits Melanoma Cell Migration and Invasiveness. Marine Drugs 2023, 21(7), 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansone, C; Brunet, C. Marine Algal Antioxidants. Antioxidants (Basel) 2020, 9(3), 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sansone, C; Bruno, A; Piscitelli, C; Baci, D; Fontana, A; Brunet, C; Noonan, DM; Albini, A. Natural compounds of marine origin as inducers of immunogenic cell death (ICD): potential role for cancer interception and therapy. Cells 2021, 10(2), 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansone, C; Pistelli, L; Brunet, C. The marine xanthophyll diatoxanthin as ferroptosis inducer in MDAMB231 breast cancer cells. Sci Rep 2025, 15(1), 8146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansone, C; Pistelli, L; Calabrone, L; Del Mondo, A; Fontana, A; Festa, M; Noonan, DM; Albini, A; Brunet, C. The carotenoid diatoxanthin modulates inflammatory and angiogenesis pathways in vitro in prostate cancer cells. Antioxidants (Basel) 2023, 12(2), 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmid, P; Adams, S; Rugo, HS; Schneeweiss, A; Barrios, CH; Iwata, H; Diéras, V; Hegg, R; Im, SA; Shaw Wright, G; Henschel, V; Molinero, L; Chui, SY; Funke, R; Husain, A; Winer, EP; Loi, S; Emens, LA. IMpassion130 Trial Investigators. Atezolizumab and nab-paclitaxel in advanced triple-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018, 379(22), 2108–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smerilli, A; Orefice, I; Corato, F; Gavalás Olea, A; Ruban, AV; Brunet, C. Photoprotective and antioxidant responses to light spectrum and intensity variations in the coastal diatom Skeletonema marinoi. Environ Microbiol. 2017, 19(2), 611–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spagnuolo, L; Della Posta, S; Fanali, C; Dugo, L; De Gara, L. Antioxidant and antiglycation effects of polyphenol compounds extracted from hazelnut skin on advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) formation. Antioxidants 2021, 10(3), 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q; Siddharth, S; Sharma, D. Triple negative breast cancer: a mountain yet to be scaled despite the triumphs. Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13(15), 3697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, N; Wu, H; Yu, Z. Advancements and challenges in triple-negative breast cancer: a comprehensive review of therapeutic and diagnostic strategies. Front Oncol. 2024, 14, 1405491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousafzai, NA; El Khalki, L; Wang, W; Szpendyk, J; Sossey-Alaoui, K. Kindlin-2 regulates the oncogenic activities of integrins and TGF-β in triple-negative breast cancer progression and metastasis. Oncogene 2024, 43(45), 3291–3305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

The effects of increasing concentrations of Dt on HUVEC and TNBC cell viability assessed using the MTT assay at different timepoints. Dose-curve effect of Dt on HUVEC (A) MDA-MB-231 (B) and on BT-549 (C) cells. Data are presented as mean ± SD and analyzed using one-way ANOVA. Each experiment was performed in triplicate, with MTT OD measurements obtained from eight replicate wells per condition. UT = untreated cells, Crt = control, Dt = diatoxanthin; ns = not significant. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001.

Figure 1.

The effects of increasing concentrations of Dt on HUVEC and TNBC cell viability assessed using the MTT assay at different timepoints. Dose-curve effect of Dt on HUVEC (A) MDA-MB-231 (B) and on BT-549 (C) cells. Data are presented as mean ± SD and analyzed using one-way ANOVA. Each experiment was performed in triplicate, with MTT OD measurements obtained from eight replicate wells per condition. UT = untreated cells, Crt = control, Dt = diatoxanthin; ns = not significant. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001.

Figure 2.

MTT assay using a combination of Doxo and Dt on TNBC cells. Viability of MDA-MB-231 (A) and BT-549 (B) cells after 48 and 72 h of treatment with increasing concentrations of Doxo and its combination with Dt (25 ng/mL). Data are presented as mean ± SD and analyzed using one-way ANOVA. Each experiment was performed in triplicate. UT = untreated cells; Ctr = control; Doxo = doxorubicin; Dt = diatoxanthin; ns = not significant. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001.

Figure 2.

MTT assay using a combination of Doxo and Dt on TNBC cells. Viability of MDA-MB-231 (A) and BT-549 (B) cells after 48 and 72 h of treatment with increasing concentrations of Doxo and its combination with Dt (25 ng/mL). Data are presented as mean ± SD and analyzed using one-way ANOVA. Each experiment was performed in triplicate. UT = untreated cells; Ctr = control; Doxo = doxorubicin; Dt = diatoxanthin; ns = not significant. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001.

Figure 3.

Effects of Dt, Doxo, and their combination on 3D-tumor spheroid growth in MDA-MB-231 and BT-549 cells. (A) Representative spheroid images at three time points (scale bar: 200 μm; four spheroids per condition). (B) Spheroid diameters across treatment conditions at each time point. (C) Crystal violet viability assay showing the percentage of viable cells at the end of the experiment relative to the initial cell count. Data are presented as mean ± SD, analyzed using one-way ANOVA. UT = untreated; Ctr = control; Doxo = doxorubicin; Dt = diatoxanthin; ns = not significant. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001.

Figure 3.

Effects of Dt, Doxo, and their combination on 3D-tumor spheroid growth in MDA-MB-231 and BT-549 cells. (A) Representative spheroid images at three time points (scale bar: 200 μm; four spheroids per condition). (B) Spheroid diameters across treatment conditions at each time point. (C) Crystal violet viability assay showing the percentage of viable cells at the end of the experiment relative to the initial cell count. Data are presented as mean ± SD, analyzed using one-way ANOVA. UT = untreated; Ctr = control; Doxo = doxorubicin; Dt = diatoxanthin; ns = not significant. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001.

Figure 4.

Transwell migration assay on TNBC cell lines. MDA-MB-231 (A) and BT-549 (B) TNBC cell lines treated with Dt. Migrated cells were quantified in three independent fields, and the values in the bar graphs represent the mean of three experimental replicates. Data are presented as mean ± SD, analyzed using one-way ANOVA. The experiment was repeated three times, each with three replicates. FBS = fetal bovine serum; Ctr = control; Dt = diatoxanthin; ns = not significant. **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

Figure 4.

Transwell migration assay on TNBC cell lines. MDA-MB-231 (A) and BT-549 (B) TNBC cell lines treated with Dt. Migrated cells were quantified in three independent fields, and the values in the bar graphs represent the mean of three experimental replicates. Data are presented as mean ± SD, analyzed using one-way ANOVA. The experiment was repeated three times, each with three replicates. FBS = fetal bovine serum; Ctr = control; Dt = diatoxanthin; ns = not significant. **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

Figure 5.

Wound healing scratch assay. Wound covered areas of MDA-MB-231 (A) and BT-549 (B) cell lines treated with Dt or vehicle only. The experiment was repeated three times, with each condition performed in triplicate. The bar graphs in the right-hand panels were generated for each replicate by measuring the area covered by migrated cells in four independent fields, 24 hours post-scratch, for each experimental condition. UT = untreated; Ctr = control; Dt = diatoxanthin.

Figure 5.

Wound healing scratch assay. Wound covered areas of MDA-MB-231 (A) and BT-549 (B) cell lines treated with Dt or vehicle only. The experiment was repeated three times, with each condition performed in triplicate. The bar graphs in the right-hand panels were generated for each replicate by measuring the area covered by migrated cells in four independent fields, 24 hours post-scratch, for each experimental condition. UT = untreated; Ctr = control; Dt = diatoxanthin.

Figure 6.

Gene expression profiling in the MDA-MB-231 (A) and BT-549 (B) TNBC cell line treated with Dt for 6 h, analyzed by qPCR. Results are displayed as bar graphs for individual genes and summarized in a heatmap. Data represent relative mRNA expression normalized to β-actin and are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA. Experiments were conducted in triplicate, with three replicates per condition. Ctr = control; Dt = diatoxanthin; ns = not significant. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001.

Figure 6.

Gene expression profiling in the MDA-MB-231 (A) and BT-549 (B) TNBC cell line treated with Dt for 6 h, analyzed by qPCR. Results are displayed as bar graphs for individual genes and summarized in a heatmap. Data represent relative mRNA expression normalized to β-actin and are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA. Experiments were conducted in triplicate, with three replicates per condition. Ctr = control; Dt = diatoxanthin; ns = not significant. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001.

Figure 7.

Heatmap of differentially expressed genes in MDA-MB-231 cells after treatment with Dt. A) Volcano plot of differentially expressed genes in MDA-MB-231 cells treated with 12 ng/mL diatoxanthin versus solvent control. Upregulated genes are shown in red (logFC >0.58, adj. p<0.05), and downregulated genes are shown in blue (logFC < −0.58, adj. p<0.05). B) Volcano plot of differentially expressed genes in MDA-MB-231 cells treated with 25 ng/mL diatoxanthin versus solvent. Upregulated genes are shown in red (logFC >0.58, adj. p<0.05), and downregulated genes are shown in blue (logFC < −0.58, adj. p<0.05). C) Venn diagram showing the overlap of significantly downregulated genes in MDA-MB-231 cells treated with 12 ng/mL and 25 ng/mL diatoxanthin. d) Heatmap of genes commonly downregulated at both diatoxanthin concentrations, showing significant changes in biological processes including blood vessel development, blood vessel morphogenesis, angiogenesis, regulation of cytokine production, cellular response to cytokine stimulus, cytokine signaling in the immune system, inflammatory response, and regulation of angiogenesis. Gene expression levels are represented as a gradient from red to blue, corresponding to positive and negative Z-scores, respectively.

Figure 7.

Heatmap of differentially expressed genes in MDA-MB-231 cells after treatment with Dt. A) Volcano plot of differentially expressed genes in MDA-MB-231 cells treated with 12 ng/mL diatoxanthin versus solvent control. Upregulated genes are shown in red (logFC >0.58, adj. p<0.05), and downregulated genes are shown in blue (logFC < −0.58, adj. p<0.05). B) Volcano plot of differentially expressed genes in MDA-MB-231 cells treated with 25 ng/mL diatoxanthin versus solvent. Upregulated genes are shown in red (logFC >0.58, adj. p<0.05), and downregulated genes are shown in blue (logFC < −0.58, adj. p<0.05). C) Venn diagram showing the overlap of significantly downregulated genes in MDA-MB-231 cells treated with 12 ng/mL and 25 ng/mL diatoxanthin. d) Heatmap of genes commonly downregulated at both diatoxanthin concentrations, showing significant changes in biological processes including blood vessel development, blood vessel morphogenesis, angiogenesis, regulation of cytokine production, cellular response to cytokine stimulus, cytokine signaling in the immune system, inflammatory response, and regulation of angiogenesis. Gene expression levels are represented as a gradient from red to blue, corresponding to positive and negative Z-scores, respectively.

Figure 8.

Secretome Analysis of TNBC Cell Lines treated with Dt using Inflammation and Angiogenesis-related antibody arrays. (A) Antibody array images obtained using RayBiotech® human Inflammation antibody array C3 after 8 seconds of exposure. (B) Antibody array images obtained using RayBiotech® human Angiogenesis antibody arrays C2 (MDA-MB-231) and C1 (BT-549) after 8 seconds of exposure. Ctr = control; Dt = diatoxanthin.

Figure 8.

Secretome Analysis of TNBC Cell Lines treated with Dt using Inflammation and Angiogenesis-related antibody arrays. (A) Antibody array images obtained using RayBiotech® human Inflammation antibody array C3 after 8 seconds of exposure. (B) Antibody array images obtained using RayBiotech® human Angiogenesis antibody arrays C2 (MDA-MB-231) and C1 (BT-549) after 8 seconds of exposure. Ctr = control; Dt = diatoxanthin.

Figure 9.

Inflammatory and angiogenesis genes expression analyzed by qPCR in TNFα-stimulated HUVEC cells treated with Dt. Cells were treated with Dt (25 ng/ml) for 6 hours and were compared to control cells. Data are shown as mRNA relative expression, normalized to control, mean ± SEM, one-way ANOVA. The experiment was conducted in triplicate, with three replicates per condition. Ctr = control; Dt = diatoxanthin. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001; ****p<0.0001.

Figure 9.

Inflammatory and angiogenesis genes expression analyzed by qPCR in TNFα-stimulated HUVEC cells treated with Dt. Cells were treated with Dt (25 ng/ml) for 6 hours and were compared to control cells. Data are shown as mRNA relative expression, normalized to control, mean ± SEM, one-way ANOVA. The experiment was conducted in triplicate, with three replicates per condition. Ctr = control; Dt = diatoxanthin. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001; ****p<0.0001.

Figure 10.

Differentially expressed genes in HUVEC cells after treatment with Dt. a) Volcano plot of differentially expressed genes in HUVEC cells treated with 12 ng/mL diathoxanthin versus solvent. Up-regulated genes are shown in red (logFC >0.58, adj. P < 0.05), and down-regulated genes are shown in blue (logFC < −0.58, adj. p<0.05). b) Volcano plot of differentially expressed genes in HUVEC cells treated with 25 ng/mL diathoxanthin versus solvent.c) Venn diagram of genes significantly down regulated (adjusted p<0.05 and logFC<–0.58) in HUVEC cells treated with diathoxanthin at 12 ng/mL and 25 ng/mL, showing the overlap between the two dose conditions. d) Heatmap of genes commonly down-regulated at both diathoxanthin doses shows regulation of genes involved in vasculature development, inflammatory response, endothelium development, regulation of angiogenesis. Gene expression levels are represented as a gradient from red to blue, corresponding to positive and negative Z-scores, respectively.

Figure 10.

Differentially expressed genes in HUVEC cells after treatment with Dt. a) Volcano plot of differentially expressed genes in HUVEC cells treated with 12 ng/mL diathoxanthin versus solvent. Up-regulated genes are shown in red (logFC >0.58, adj. P < 0.05), and down-regulated genes are shown in blue (logFC < −0.58, adj. p<0.05). b) Volcano plot of differentially expressed genes in HUVEC cells treated with 25 ng/mL diathoxanthin versus solvent.c) Venn diagram of genes significantly down regulated (adjusted p<0.05 and logFC<–0.58) in HUVEC cells treated with diathoxanthin at 12 ng/mL and 25 ng/mL, showing the overlap between the two dose conditions. d) Heatmap of genes commonly down-regulated at both diathoxanthin doses shows regulation of genes involved in vasculature development, inflammatory response, endothelium development, regulation of angiogenesis. Gene expression levels are represented as a gradient from red to blue, corresponding to positive and negative Z-scores, respectively.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).