Submitted:

19 December 2025

Posted:

22 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

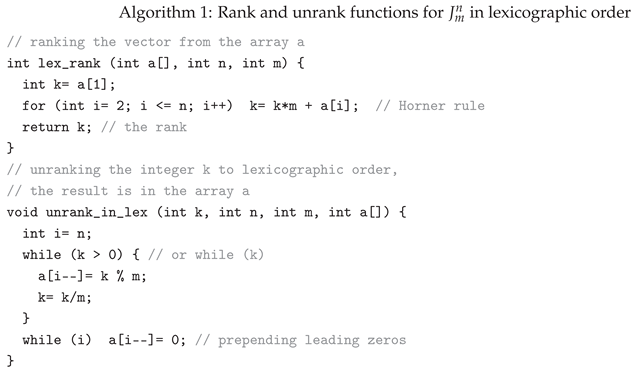

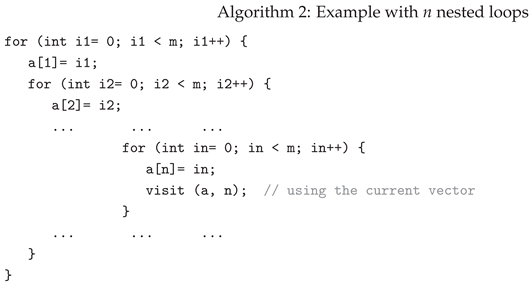

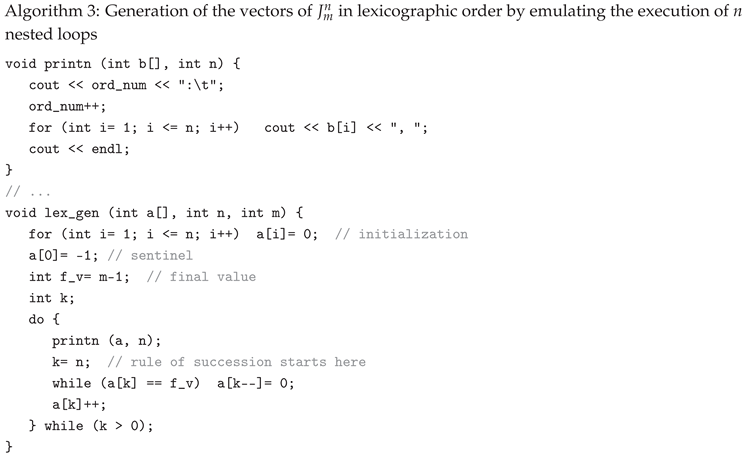

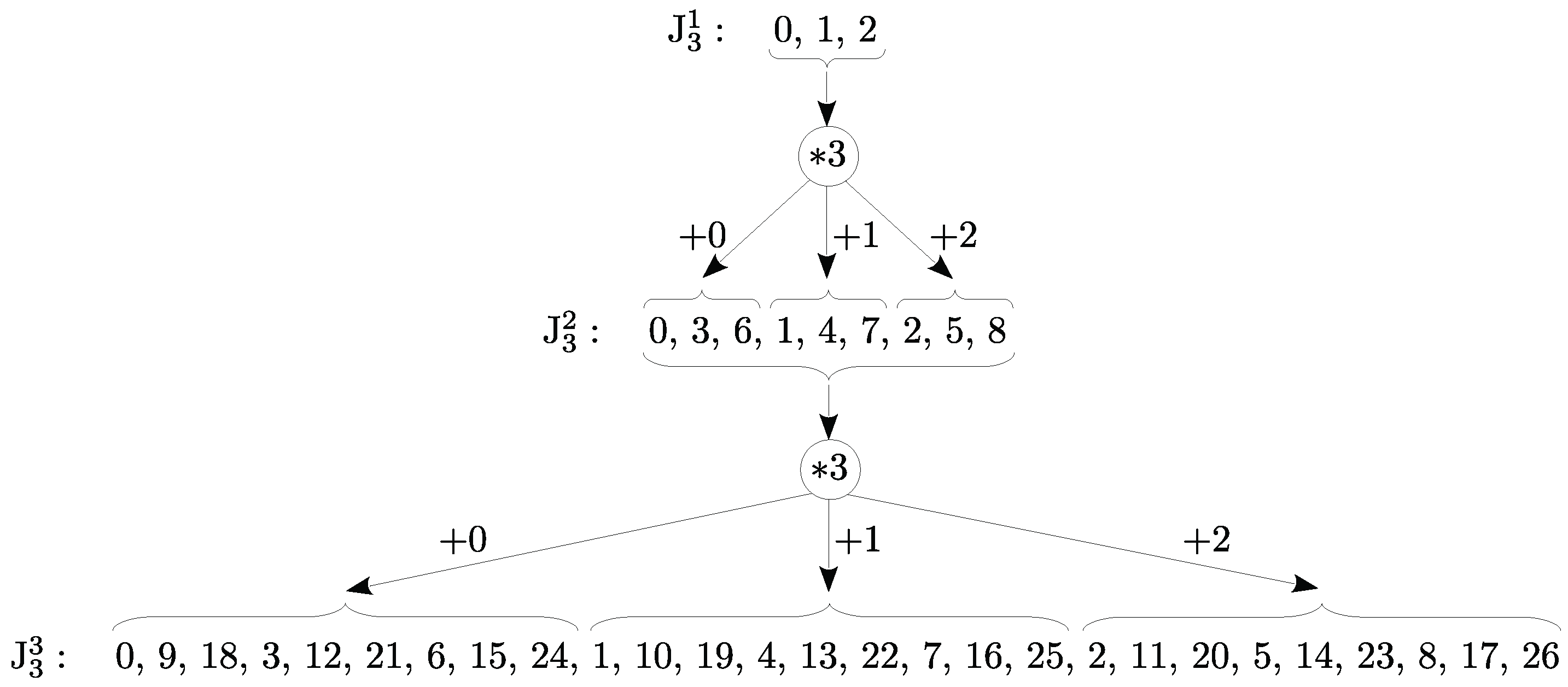

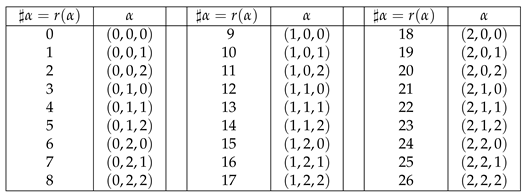

2. Lexicographic Order of the -ary Vectors

2.1. Definitions, Properties and Preliminary Notes

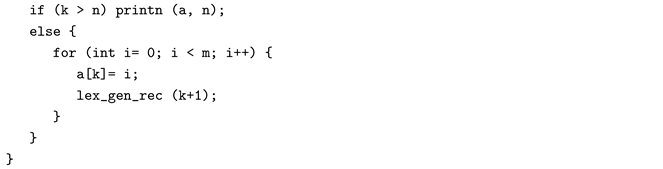

2.2. Generation of the Vectors of in Lexicographic Order

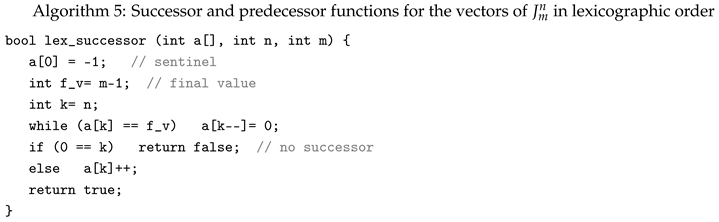

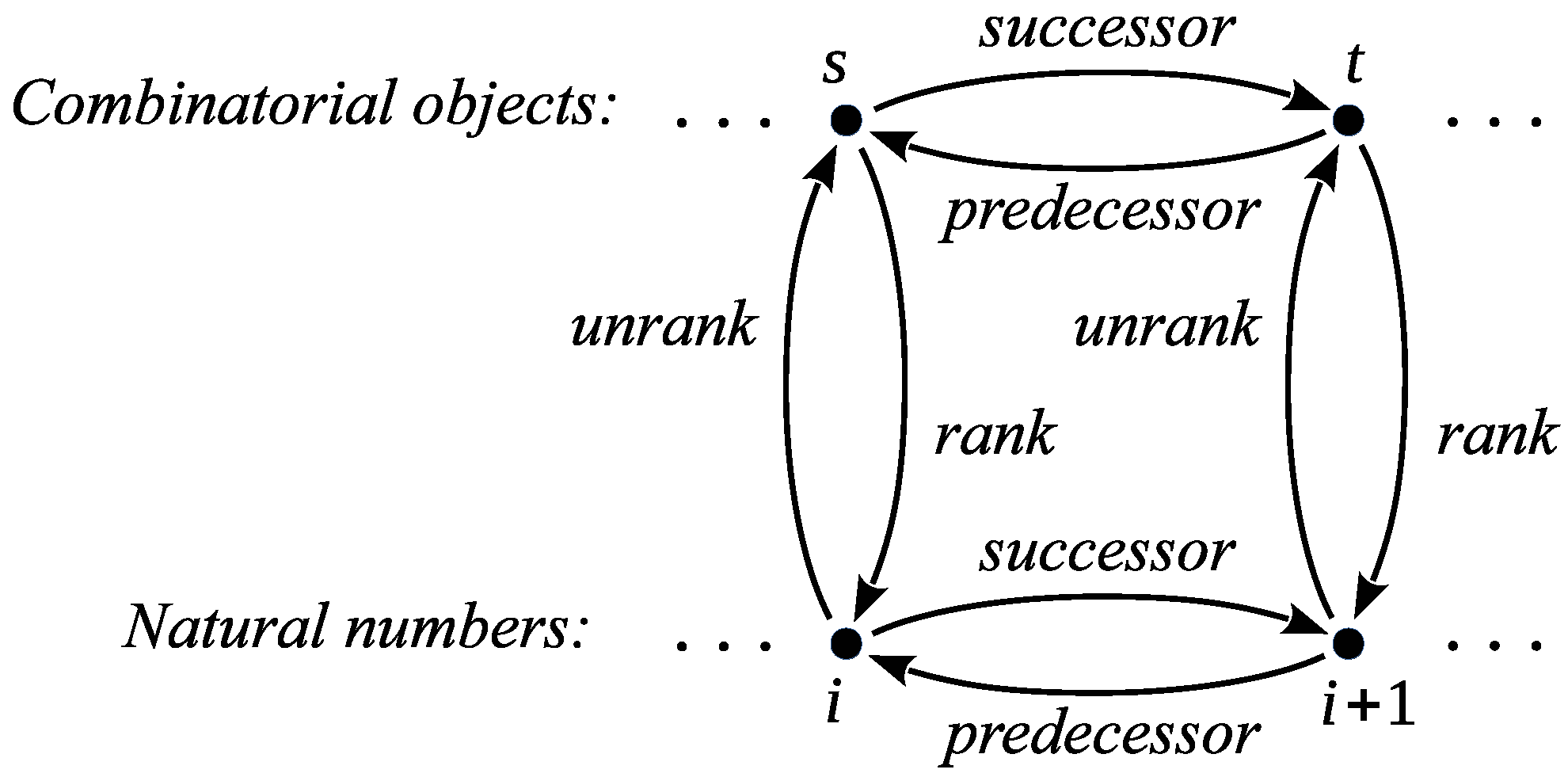

2.3. Successor and Predecessor Functions in the Lexicographic Order

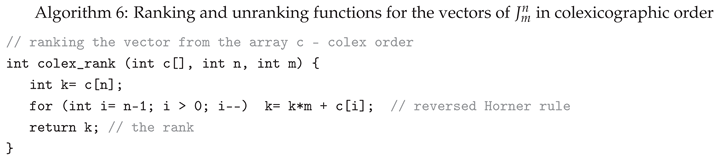

3. Colexicographic Order of the Vectors of

3.1. Definitions, Properties and Preliminary Notes

- 1.

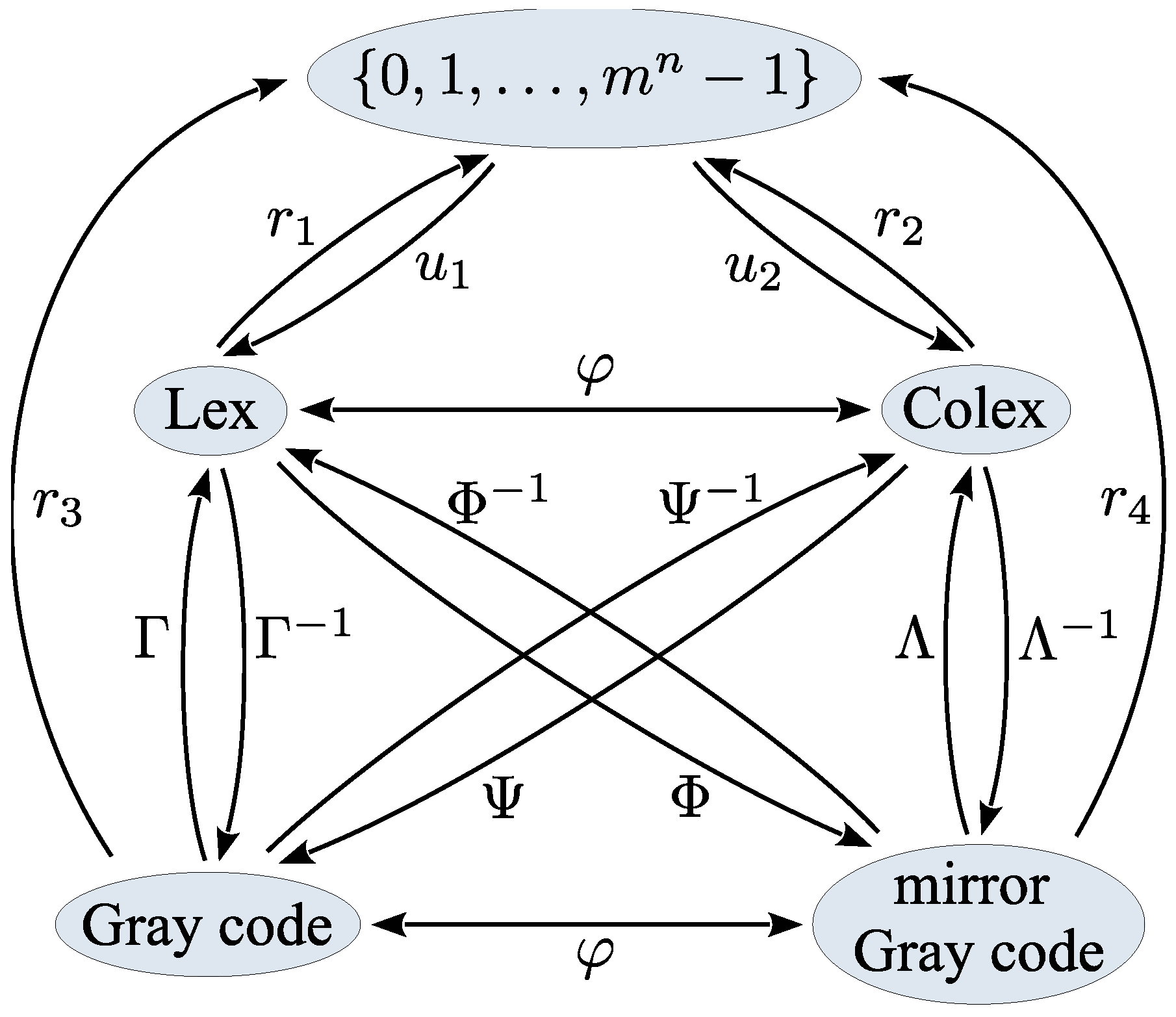

- Relationship between the lexicographic and colexicographic order: The colexicographic order can be obtained from the lexicographic order and vice versa, by reflecting the coordinate order of the vectors in the respective ordering. That is, , iff [6].

- 2.

- We define the coordinate-reversal function φ such that , and for any vector , . Thus, the coordinates of are left-right mirror image of those of α and vice versa [3] [p. 144]. Obviously φ is a bijection and also and therefore φ is an involution.

- 3.

- The fixed points of the function φ are the palindromes, i.e., . Their number is .

- 4.

- Comparing Definition 1 and Definition 2 and in accordance with Theory of Formal Languages, we note that Definition 1 uses right recursion (or substitution—the words are derived from left to the right and therefore the rightmost symbols change the fastest, compared to the leftmost symbols, which change the slowest), while Definition 2 uses left recursion.

- 1.

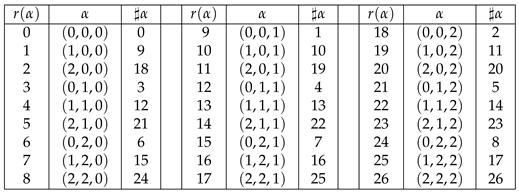

- For every vector α in lexicographic order, , where is the corresponding vector in colexicographic order. Also, if and only if , that is, α is a palindrome.

- 2.

- Let L and C be matrices representing the vectors of , listed in lexicographic and colexicographic order, respectively. Then the i-th column of L coincides with the -st column of C, for .

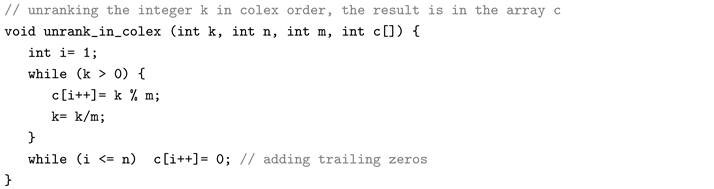

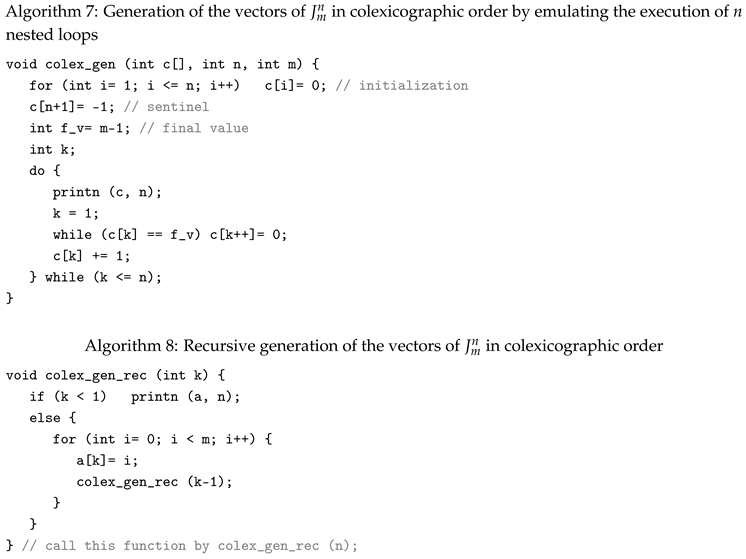

3.2. Generation of the Vectors of in Colexicographic Order

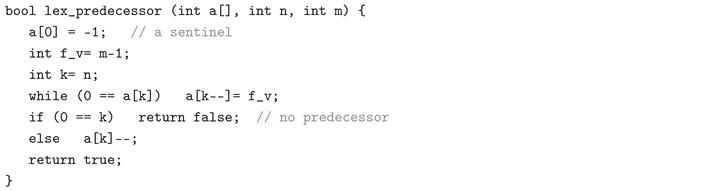

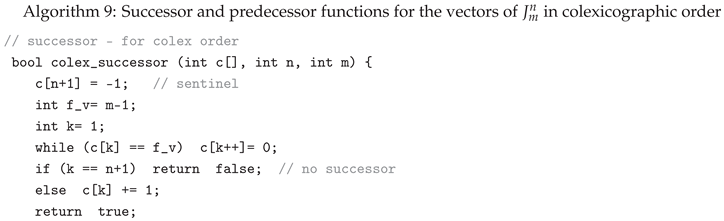

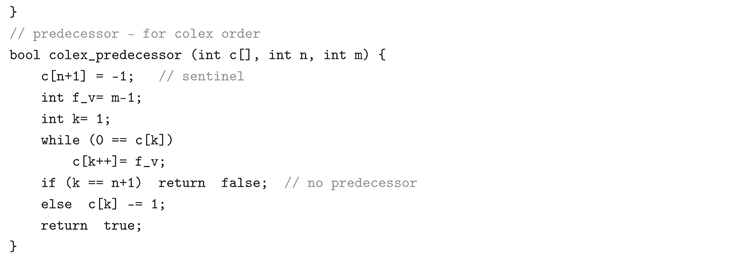

3.3. Successor and Predecessor Functions in the Colexicographic Order

4. Mirror -Ary Reflected Gray Code

4.1. About the Two Versions of the m-ary Reflected Gray Code

- Relationship between the lexicographic and colexicographic order. The connection between the lexicographic and colexicographic order of the m-ary vectors is given by the coordinate-reversal function defined in Remark 1. Although these orders appear closely related, they are distinct and have separate names. The same relationship exists between the m-ary reflected Gray code and its mirror version. This justifies distinguishing them and calling them by different names.

-

Ambiguities in the literature. Many authors, when discussing an m-ary reflected Gray code, actually talk about a mirror m-ary reflected Gray code, or talk about both codes using the same name. When readers are not careful or do not distinguish between these codes, they can confuse them. For example:

- (a)

-

In [5] the authors first give a right-recursive definition of BRGC and show an example of it. They also define the transition sequence, where the coordinates are numbered from right to left, and emphasize the connection between it and the generation of the codewords. They also give a left-recursive definition of BRGC, but treat the two codes as the same code. In [12,13], the authors define and use only the left-recursive (mirror) BRGC and show the generated codewords. They formulate and prove the rule of succession for this code—which coordinate must be changed in the current codeword to obtain the next codeword, in fact the next term of the transition sequence. The same, but more thoroughly and in an optimized way, is done in [3] [Algorithm G].We can summarize: all these algorithms generate BRGC when the coordinates are numbered from right to left, for example . For each , the i-th coordinate of the current vector is stored in element g[i] of array g. Thus, the algorithms output BRGC if the array g is printed from right to left, otherwise they output the vectors of the mirror BRGC.

- (b)

- In [6], Ruskey defines recursively (starting from the empty string) the standard BRGC and relates it to a Hamiltonian cycle on the Boolean cube, the Towers of Hanoi problem, transition sequence and the generation of BRGC from it, as well as the ranking and unranking functions for BRGC. He then presents a left-recursive definition (via formula (5.3), p. 120), which corresponds to the mirror BRGC. Ruskey explicitly notes: Note that we are appending rather than prepending. In developing elegant natural algorithms this has the same advantage that colex order had over lex order in the previous chapter. Thus, the algorithms he proposes (indirect and direct) generate the mirror BRGC.

- (c)

- In [17], the author discusses and illustrates (in Table 1) the usual (right-recursive) k-ary reflected Gray code. He derives a non-recursive algorithm that generates its codewords and outputs them from right to left. In this way, the algorithm reverses the coordinates of the generated codewords and actually generates the left-recursive k-ary reflected Gray code. In [18], the author recursively defines the usual N-ary reflected Gray code and proposes Algorithm 1, which generates its codewords. Instead of printing them, the algorithm outputs the message “codeword available”. If we print them, we observe that they are the codewords of the left-recursive N-ary reflected Gray code. The same can be seen in [19], where the authors use the same definition and algorithm.

- Algorithmic differences. The algorithms for generating the vectors of the two versions of m-ary reflected Gray code are similar, but have subtle differences, as we will see later. The same applies to the four basic functions for these versions.

4.2. Definitions, Properties and Preliminary Notes

- 1.

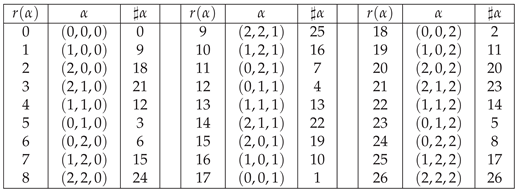

- For every vector , we have , where is the corresponding vector in . Also, if and only if , that is, α is a palindrome.

- 2.

- Let M and be matrices representing the vectors of , and , respectively. Then the i-th column of M coincides with the -st column of , for .

4.3. Generation of All Vectors of

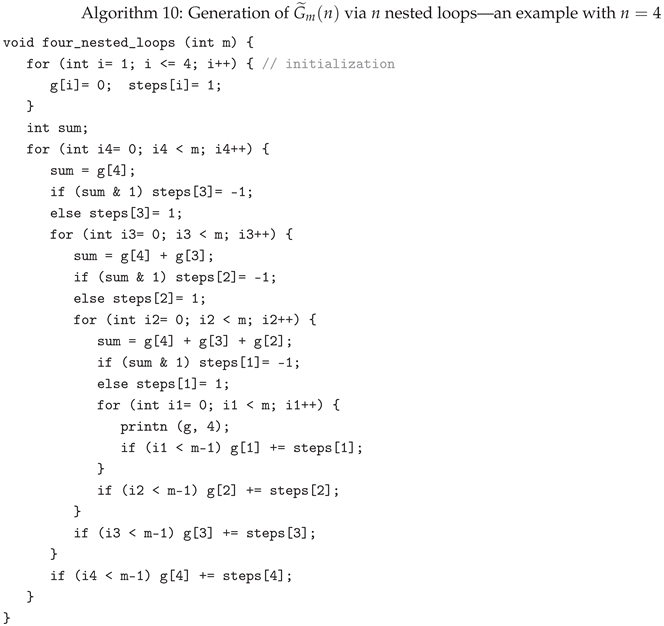

4.3.1. Nested Loops Algorithm.

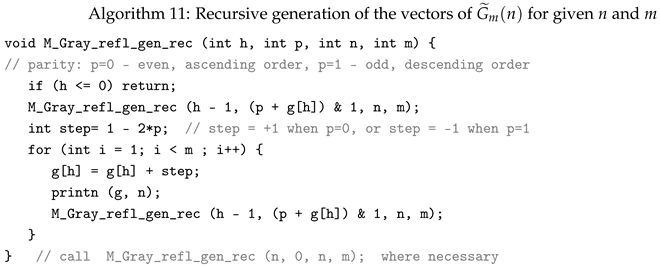

4.3.2. Recursive Algorithms

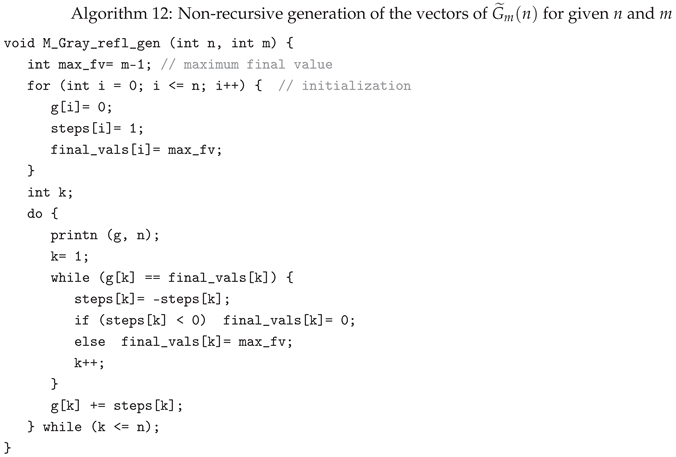

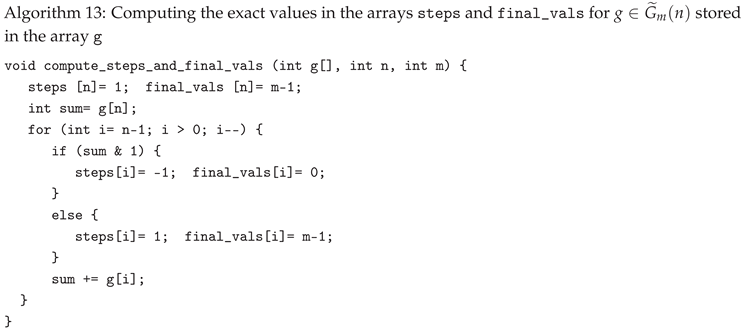

4.3.3. Nested Loops Emulation Algorithm

4.3.4. Generation of via the Transition Sequence

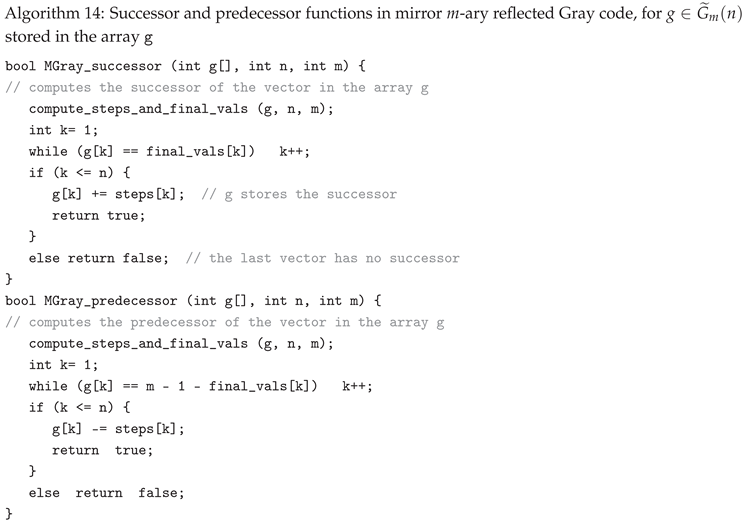

4.4. Successor and Predecessor Functions in the Mirror Gray Code

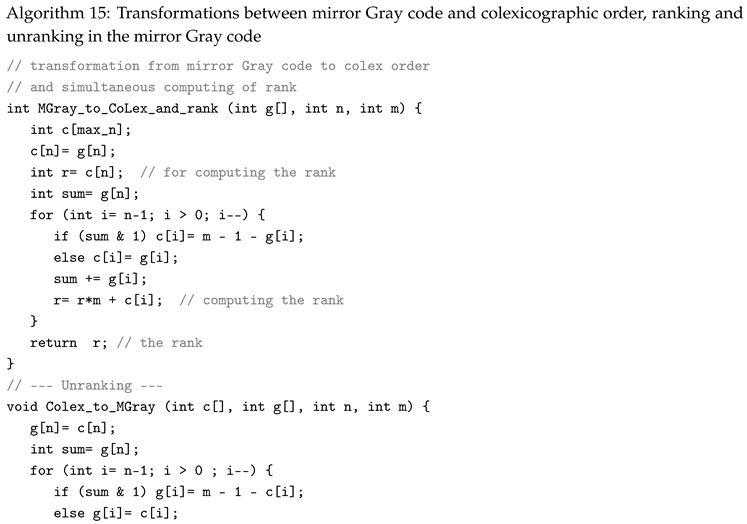

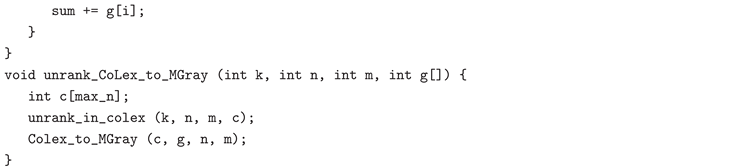

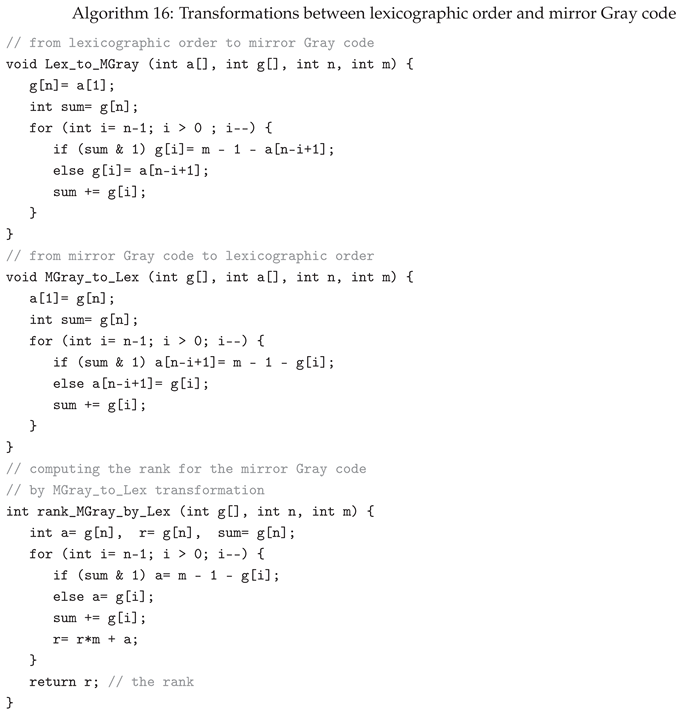

5. Transformations Between the Orderings

6. Conclusions

Funding

References

- Arndt, J. Matters Computational: Ideas, Algorithms, Source Code; Springer, 2011.

- Arndt, J. Subset-lex: did we miss an order? 2014. [Accessed 30.10.2025]. Available at:. [CrossRef]

- Knuth, D. The Art of Computer Programming, Volume 4A: Combinatorial Algorithms, Part 1; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 2014.

- Kreher, D.; Stinson, D. Combinatorial Algorithms: Generation, Enumeration and Search; CRC Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1999.

- Reingold, E.; Nievergelt, J.; Deo, N. Combinatorial algorithms. Theory and practice; Prentice-Hall: New Jersey (NJ), 1977.

- Ruskey, F. Combinatorial Generation. Working Version (1j-CSC 425/ 520). In Preliminary Working Draft; University of Victoria: Victoria, BC, Canada, 2003. [Accessed 23.11.2025]. Available at: http://page.math.tu-berlin.de/~felsner/SemWS17-18/Ruskey-Comb-Gen.pdf.

- Mütze, T. Combinatorial Gray Codes—An Updated Survey. Electron. J. Comb. 2023, 30. [Accessed 30.10.2025]. Available at: https://www.combinatorics.org/ojs/index.php/eljc/article/view/ds26/pdf.

- Savage, C. A Survey of Combinatorial Gray Codes, SIAM Review, 1997, 39, 605–629.

- OEIS Foundation Inc., The On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences. Orderings. [Accessed 30.10.2025]. Available at: https://oeis.org/wiki/Orderings.

- Bakoev, V. Mirror (Left-recursive) Binary Gray Code, Mathematics and Informatics, 2023, 66, No. 6, 559–578. [CrossRef]

- Bouyuklieva, S.; Bouyukliev, I.; Bakoev, V.; Pashinska-Gadzheva, M. Generating m-ary Gray Codes and Related Algorithms, Algorithms 2024, 17(7), 311. [CrossRef]

- Lipski, W. Kombinatoryka dla Programistów (Combinatorics for Programmers); Wydawnictwa Naukowo-Techniczne: Warszawa, Poland, 1982, 1989; ISBN 83-204-1023-1. (In Polish, Russian translation—Mir, Moskva, 1988).

- Nijenhuis, A.; Wilf, H. Combinatorial Algorithms for Computers and Calculators, (1st ed., 1975), 2nd ed., Academic Press, 1978.

- Sawada, J.; Williams, A.; Wong, D. Necklaces and Lyndon words in colexicographic and binary reflected Gray code order, Journal of Discrete Algorithms, 2017, 46-47, 25–35. [CrossRef]

- Cohn, M. Affine m-ary gray codes, Information and Control, 1963, 6, Is. 1, 70–78. [CrossRef]

- Suparta, I.N. Counting sequences, Gray codes and Lexicodes, Dissertation at Delft University of Technology, 2006. Available at https://theses.eurasip.org/theses/113/counting-sequences-gray-codes-and-lexicodes/download/. Last visited: 3.06.2024.

- Guan, D.J. Generalized Gray Codes with Applications, Proc. Natl. Sci. Counc. ROC(A) 1998, 22, 841–848.

- Er, M.C. On Generating the N-ary Reflected Gray Codes. IEEE Trans. Comput. 1984, c-33, 739–741.

- Gulliver, T.A.; Bhargava; V.K.; Stein, J.M. Q-ary Gray codes and weight distributions, Applied Mathematics and Computation 1999, 103, 97–109. [CrossRef]

- Kapralov, S. Bounds, constructions and classification of optimal codes. Doctor Math. Sci. Dissertation, Technical University, Gabrovo, Bulgaria, 2004. (in Bulgarian).

- Sharma, B.D.; Khanna, R.K. On m-ary Gray codes. Inf. Sci. 1978, 15, 31–43.

- Flores, I. Reflected Number Systems, IRE Transactions on Electronic Computers, June 1956, Vol. EC-5, No. 2, 79–82.

- Mambou, E.N.; Swart, T.G. A Construction for Balancing Non-Binary Sequences Based on Gray Code Prefixes, IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory, Aug. 2018, Vol. 64, No. 8, 5961–5969. [CrossRef]

| 1 | This problem is equivalent with generating all: (1) generalized characteristic vectors of the subsets (submultisets) of a given multiset [2]; (2) n-tuples of the Cartesian product of n sets. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).