Submitted:

19 December 2025

Posted:

22 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

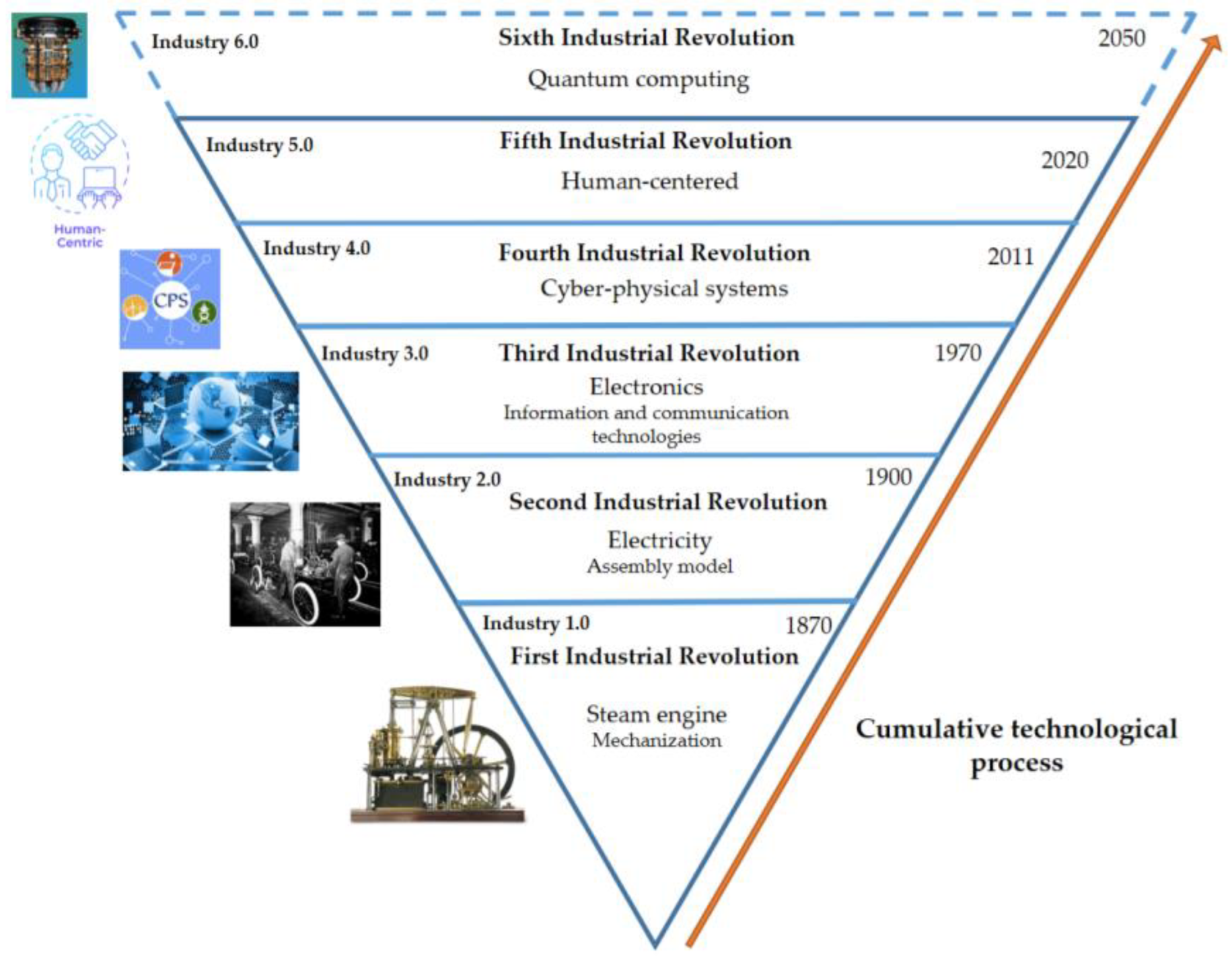

2.1. Industrial Revolutions

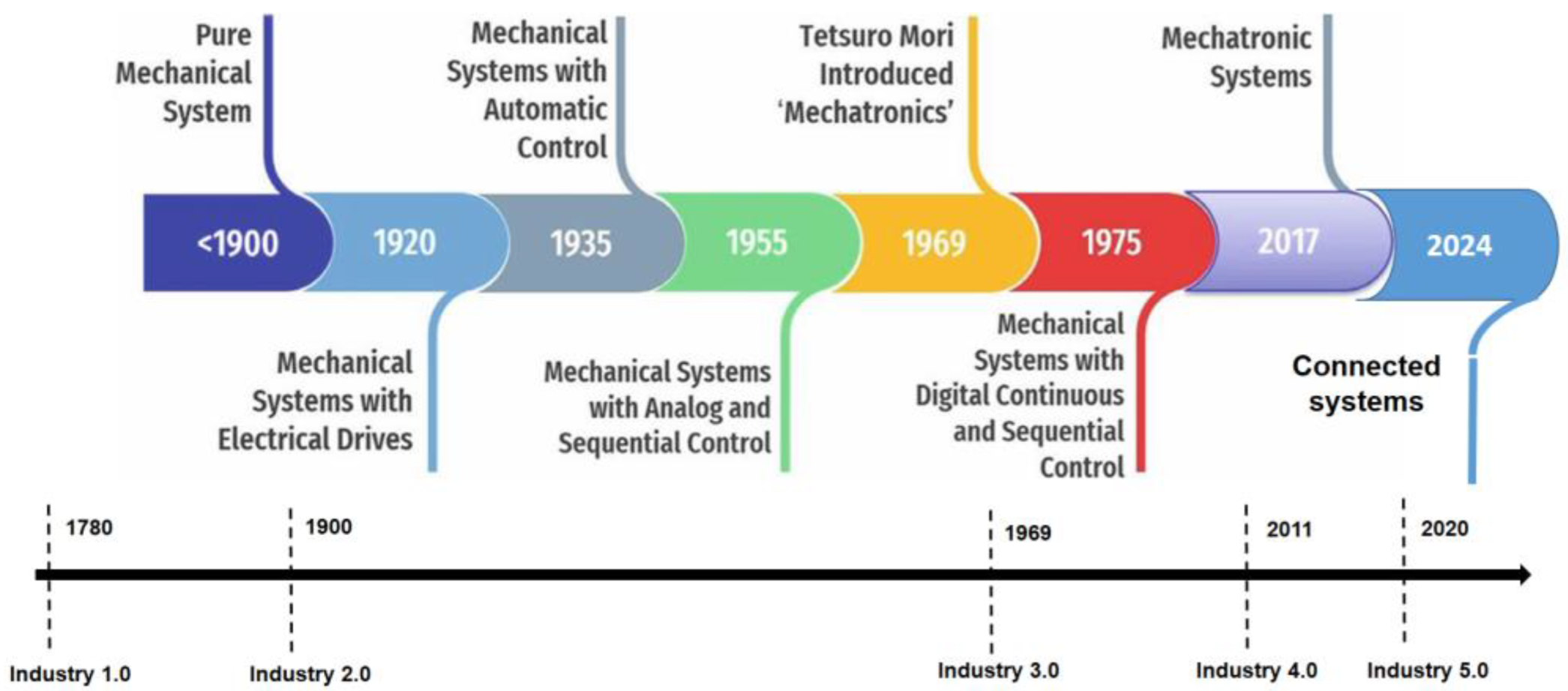

2.1.1. History of Industrial Revolutions.

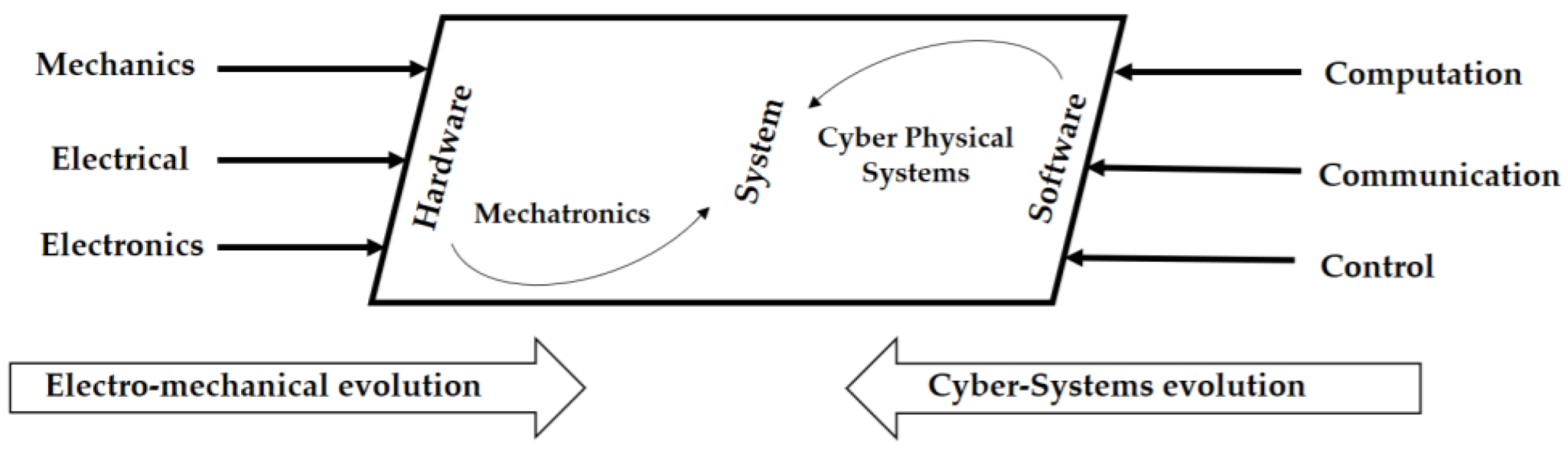

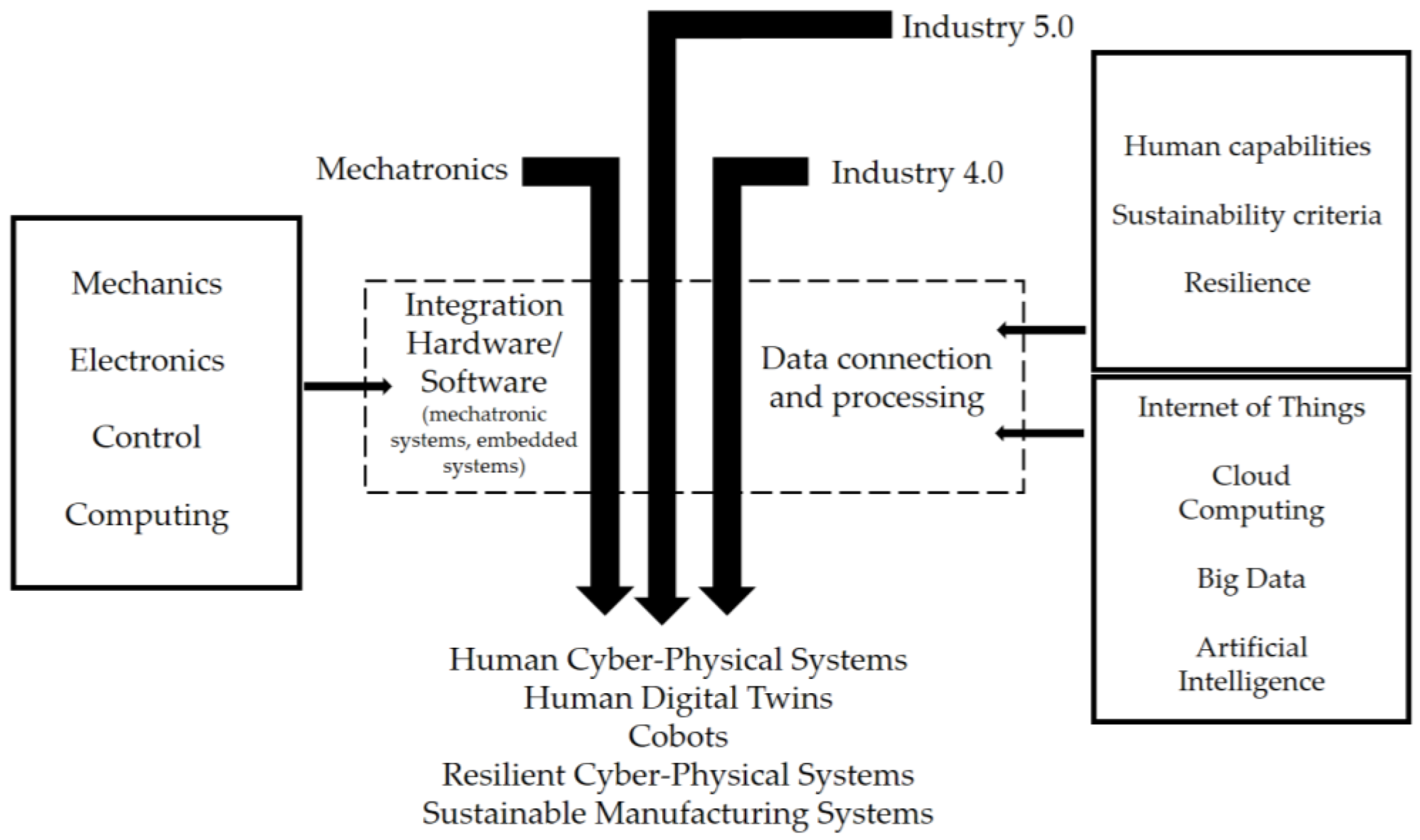

2.2. Industrial Revolutions and Mechatronics.

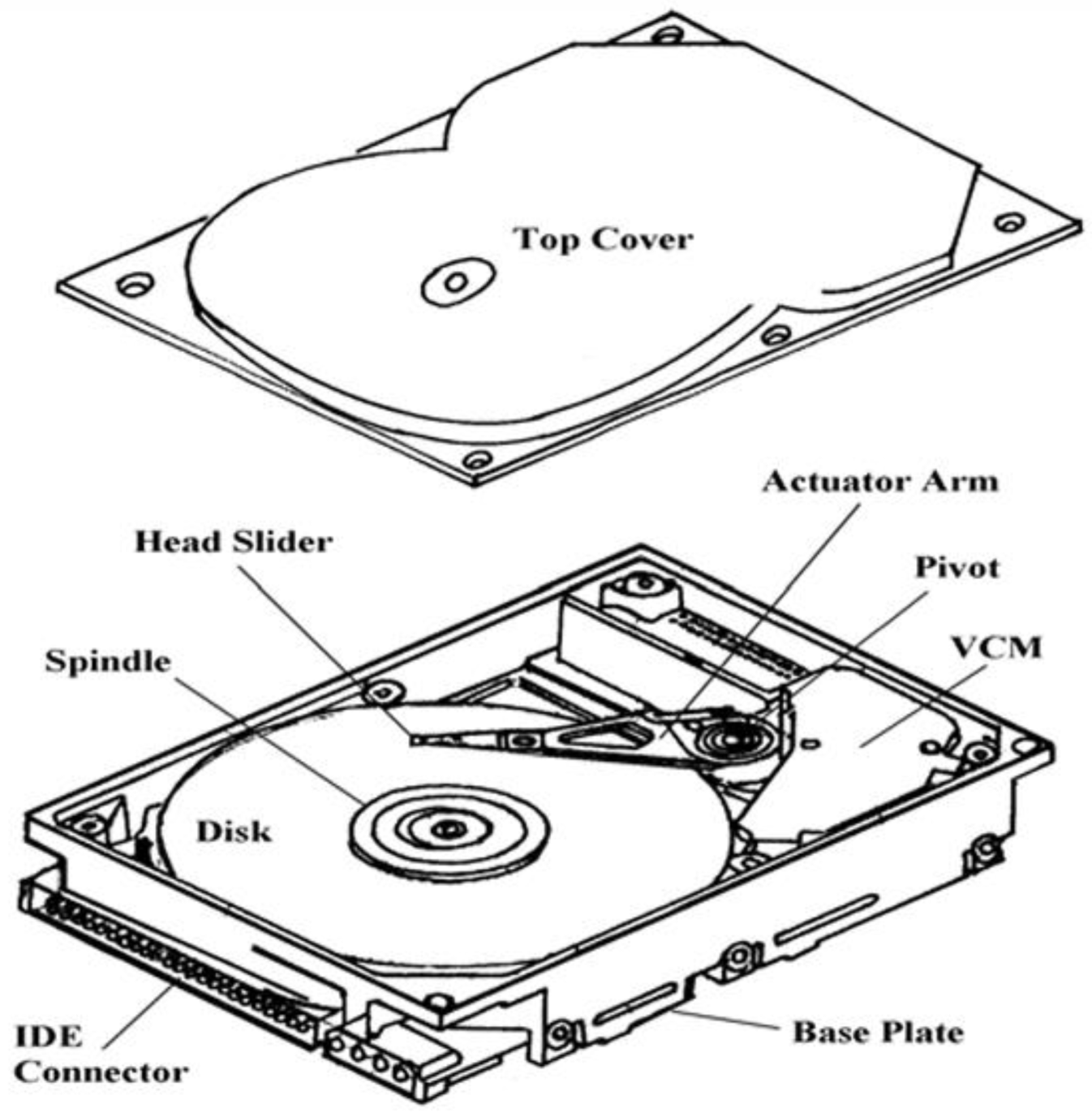

2.2.1. Mechatronics and Industry 3.0

- (1)

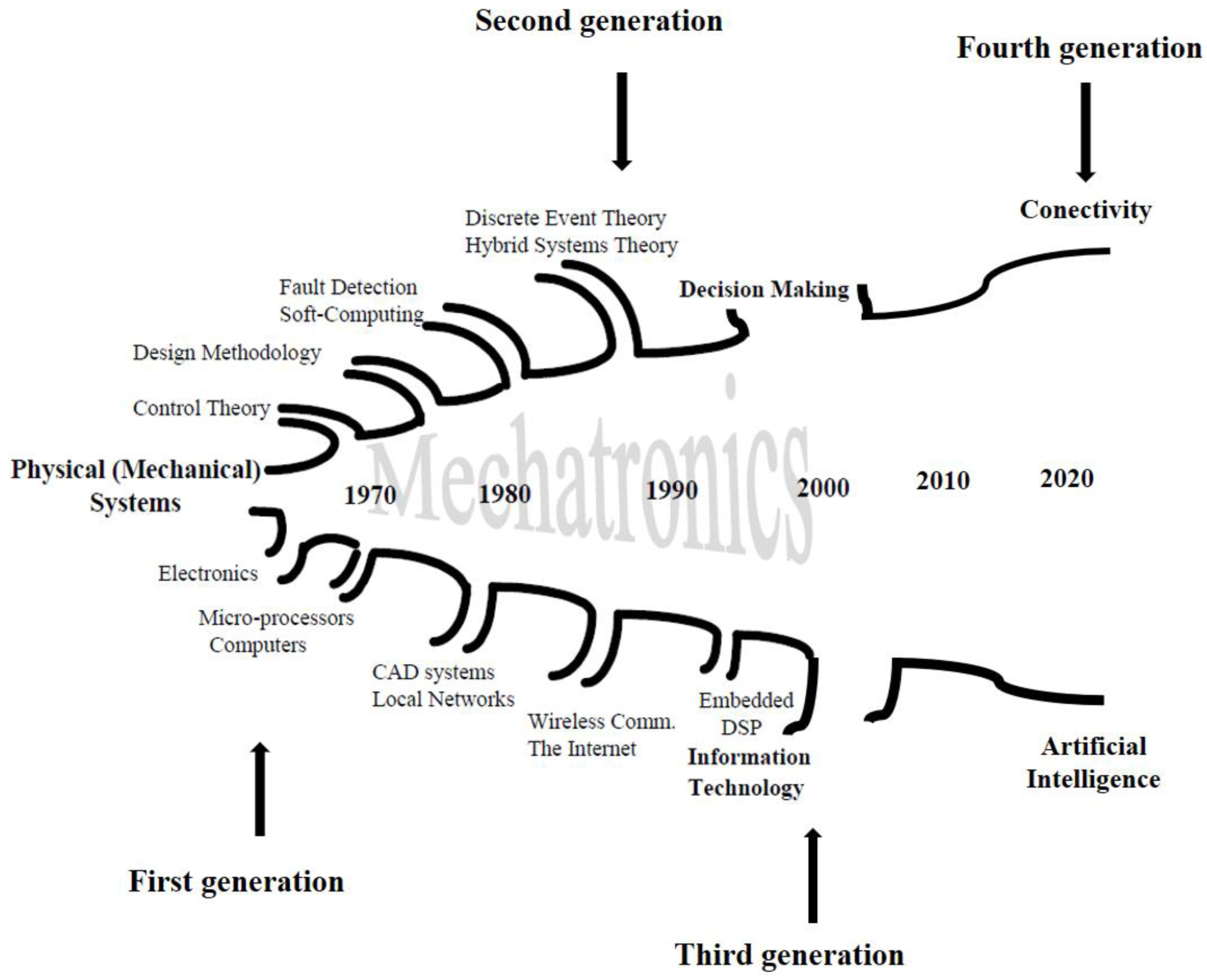

- First generation: The beginning of mechatronics with little integration between mechanics and control (development of electromechanical systems: basic robotic manipulators, automatic doors, washing machines, CNC machine prototypes, etc. [37,38]).

- (2)

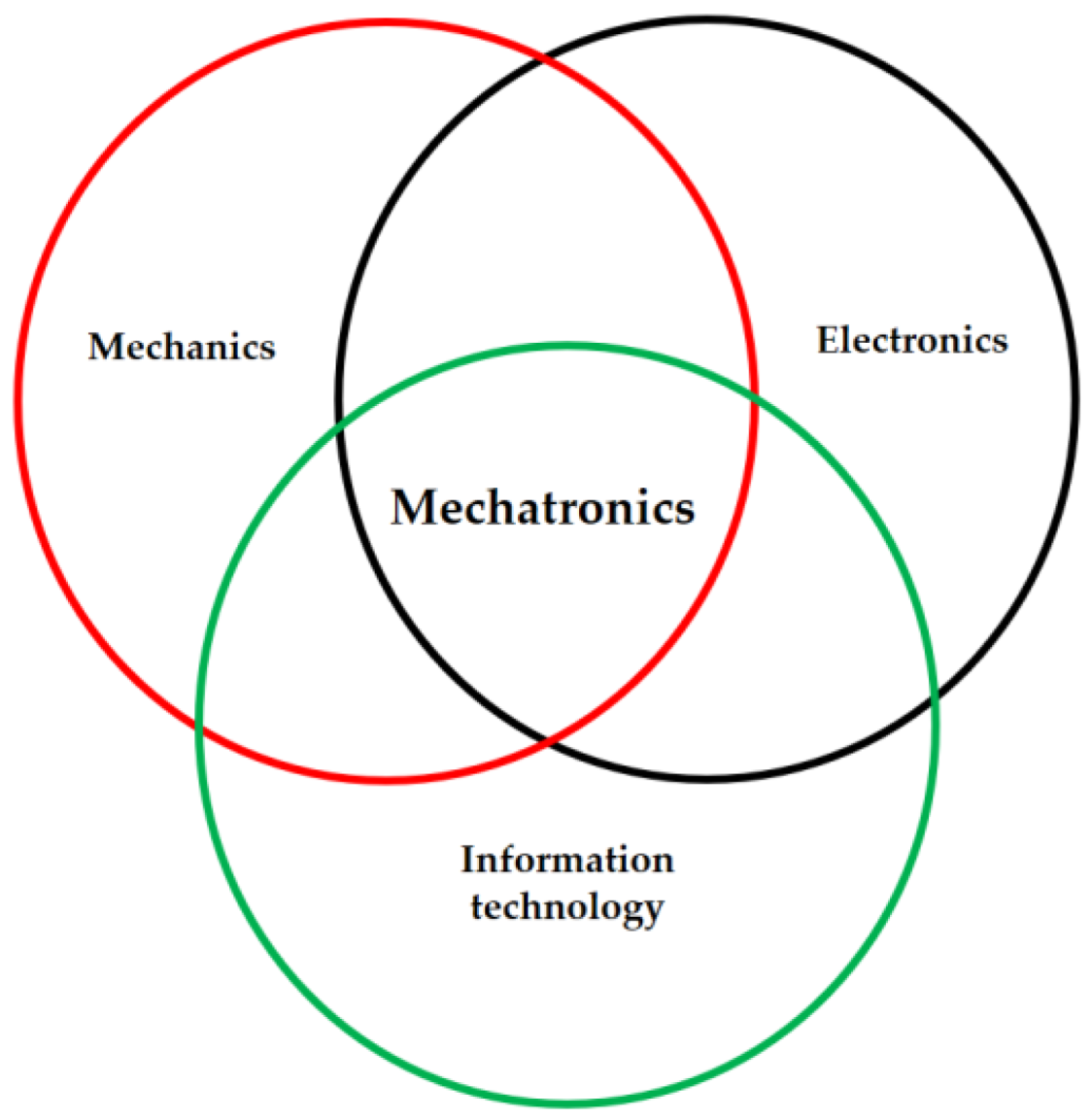

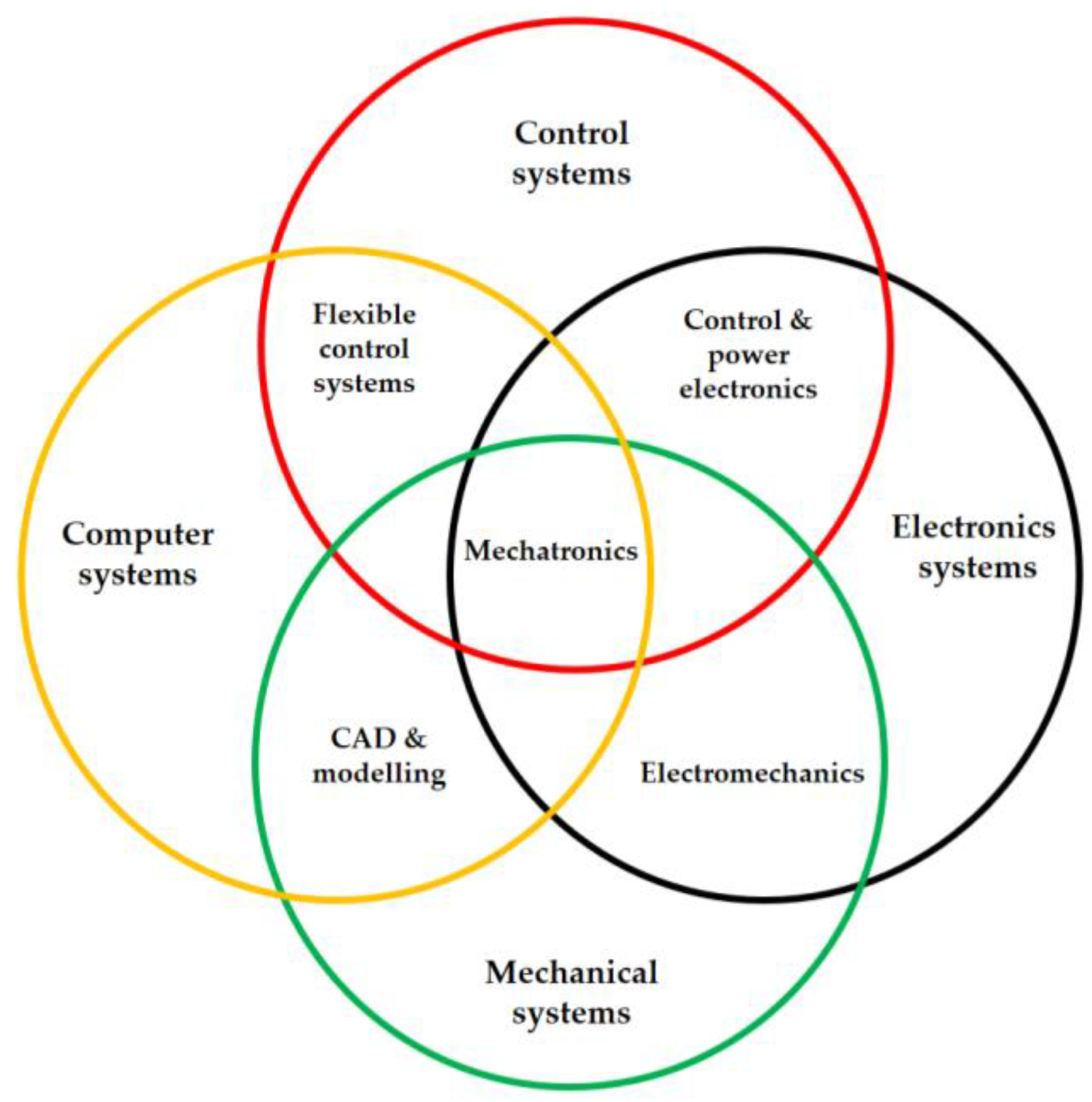

- Second generation: Strengthening of the integration of mechanics, computing, and electronics (microprocessor applications and use of digital information processing units, development of MEMS, rapid prototypes, etc. [39]).

- (3)

- Third generation: Formalization of the concept of mechatronics, integrating mechanics, electronics, control, and digitization (recognition of mechatronics as an engineering discipline, development of nanotechnology and biotechnology, development of intelligent systems, etc. [44]).

- (4)

- Fourth generation: Intelligent, connected, resilient, and eco-mechatronics (development of cyber-physical systems, digital twins, cobots, etc.).

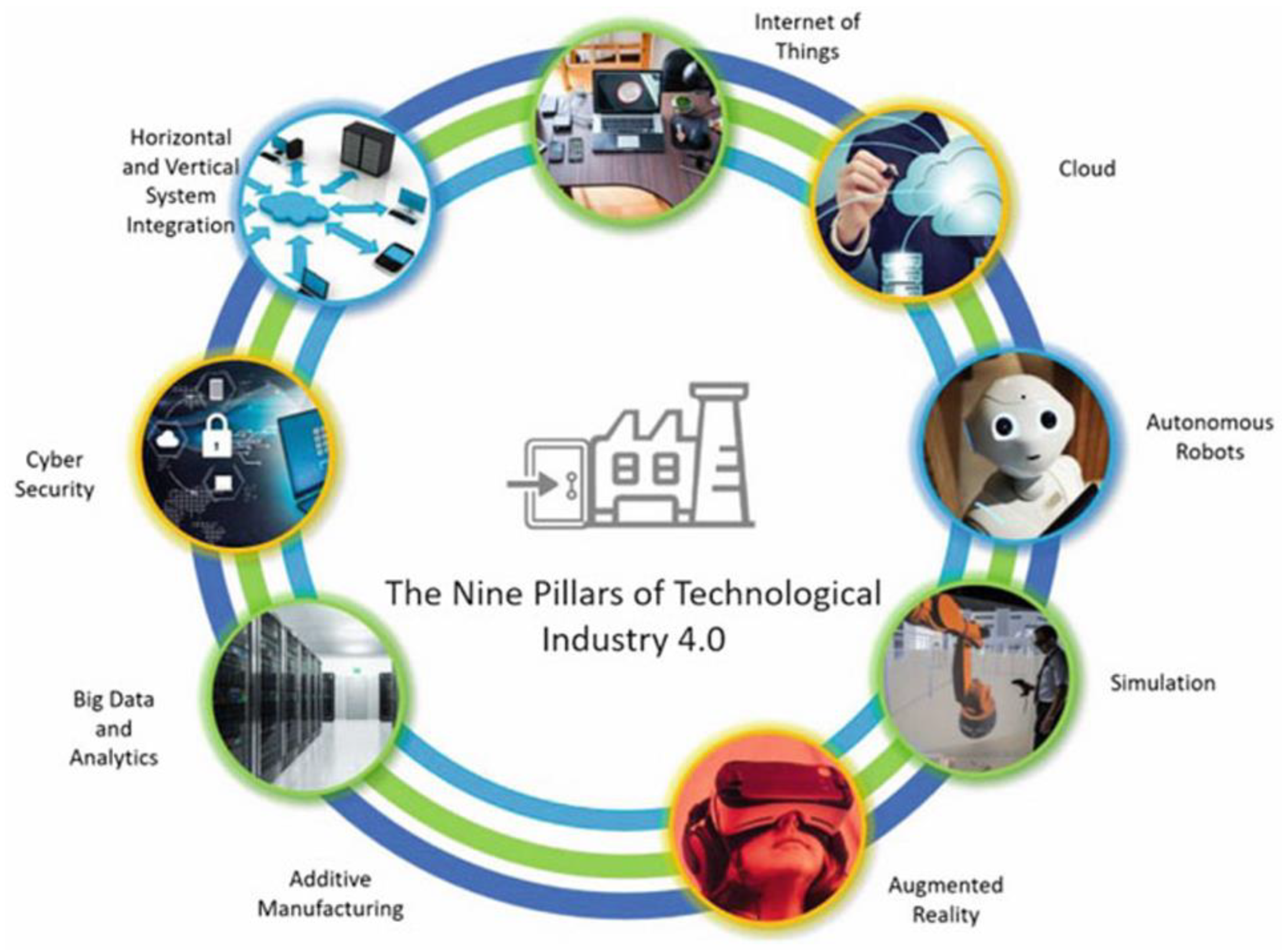

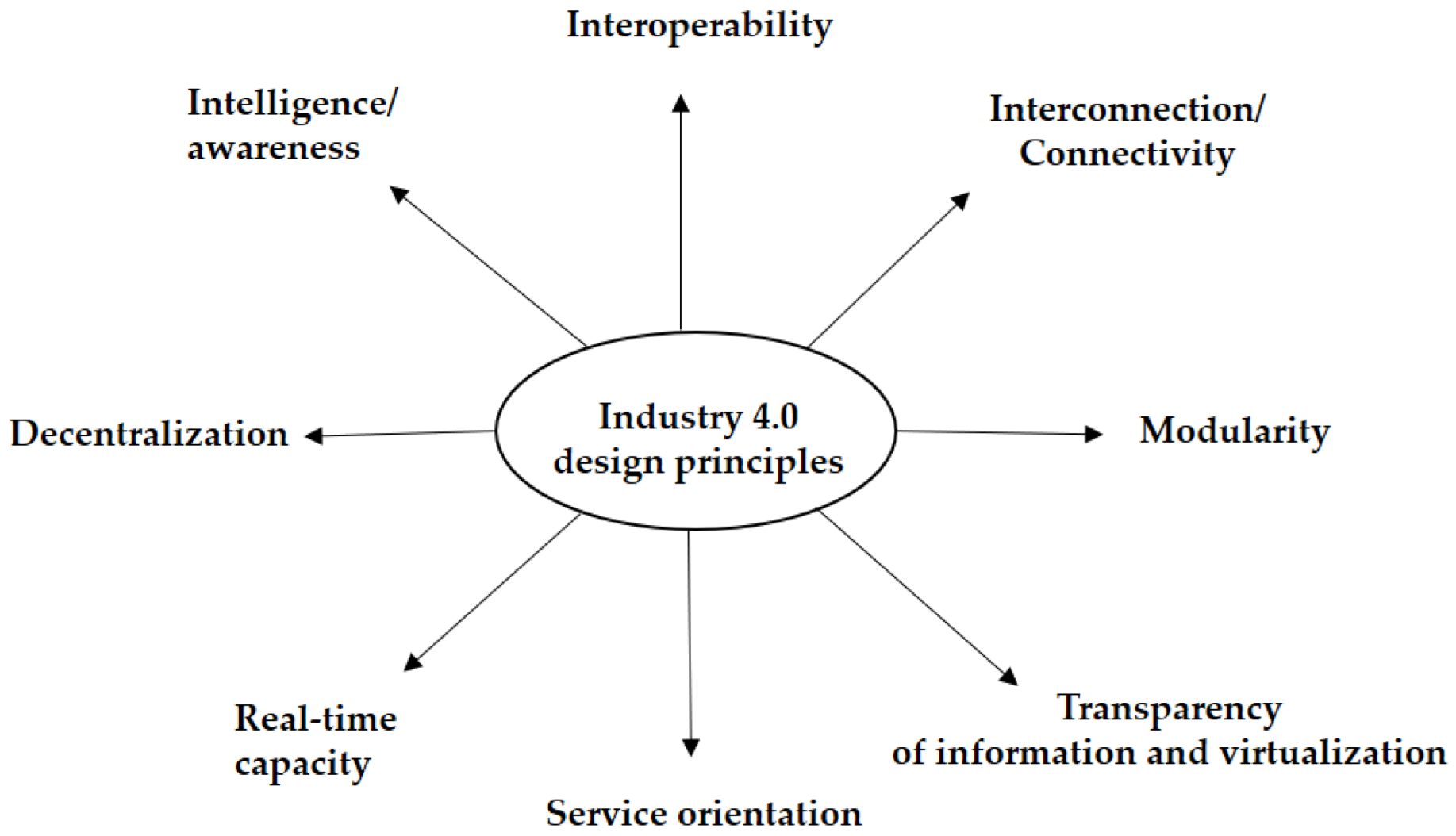

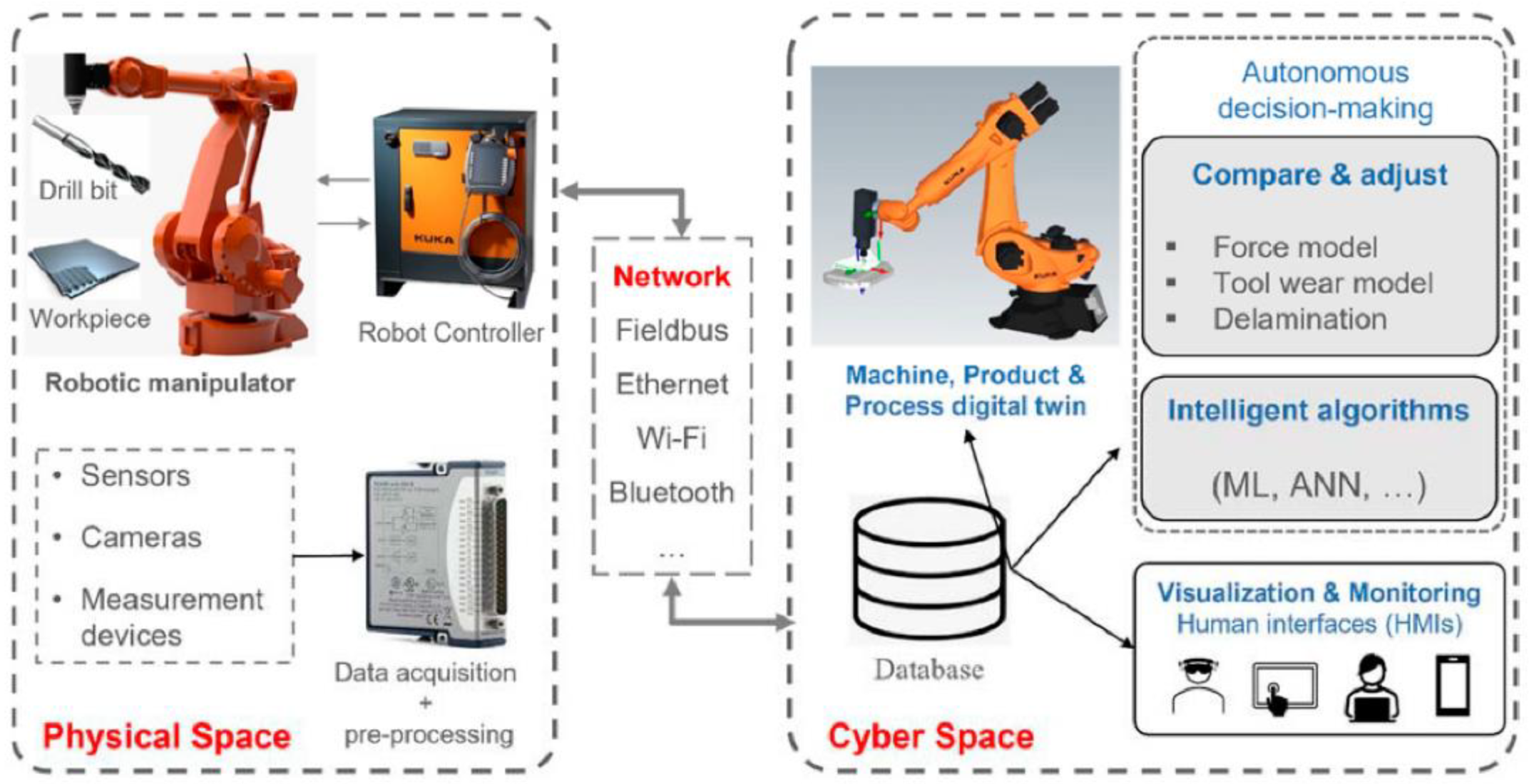

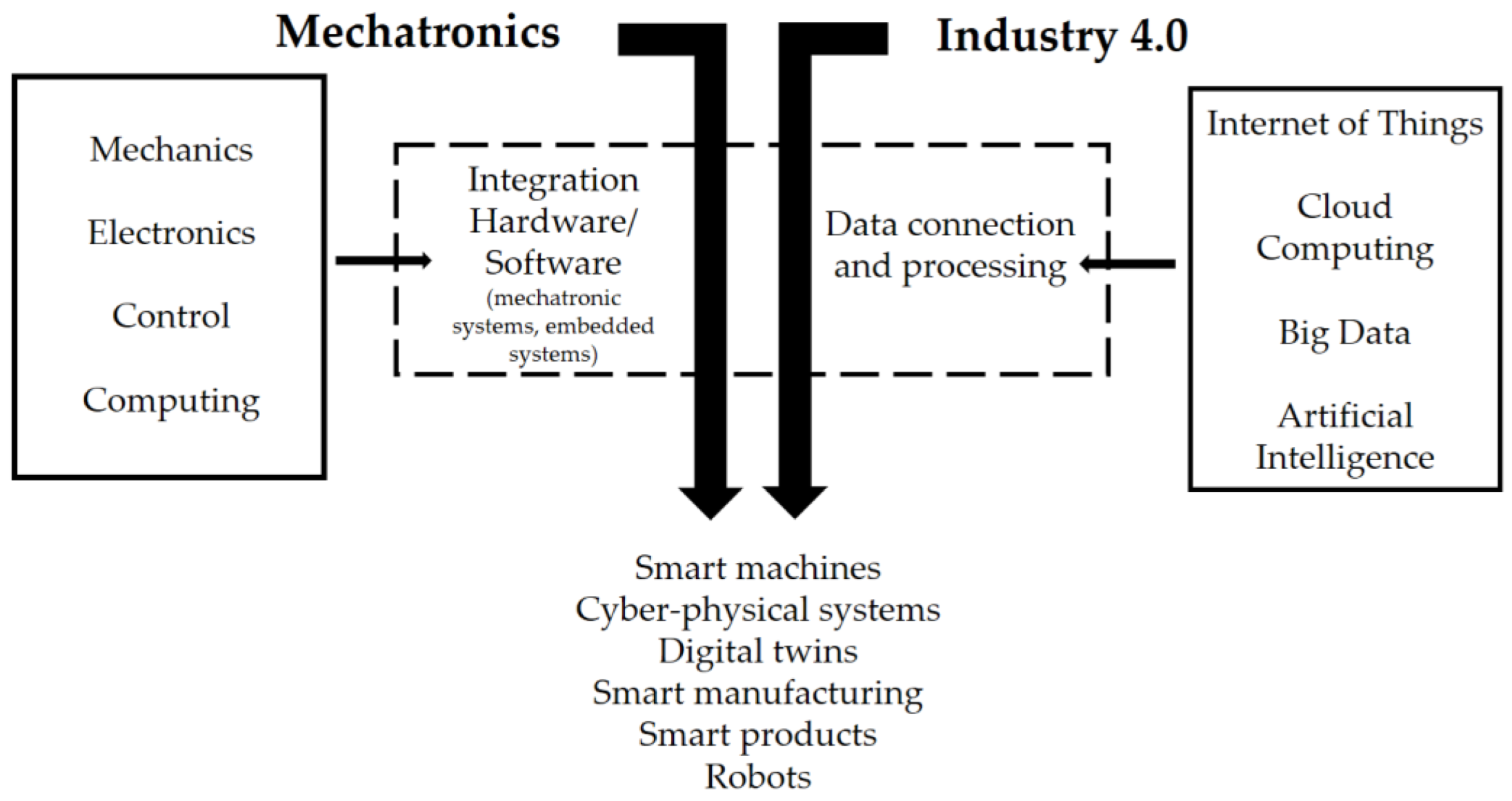

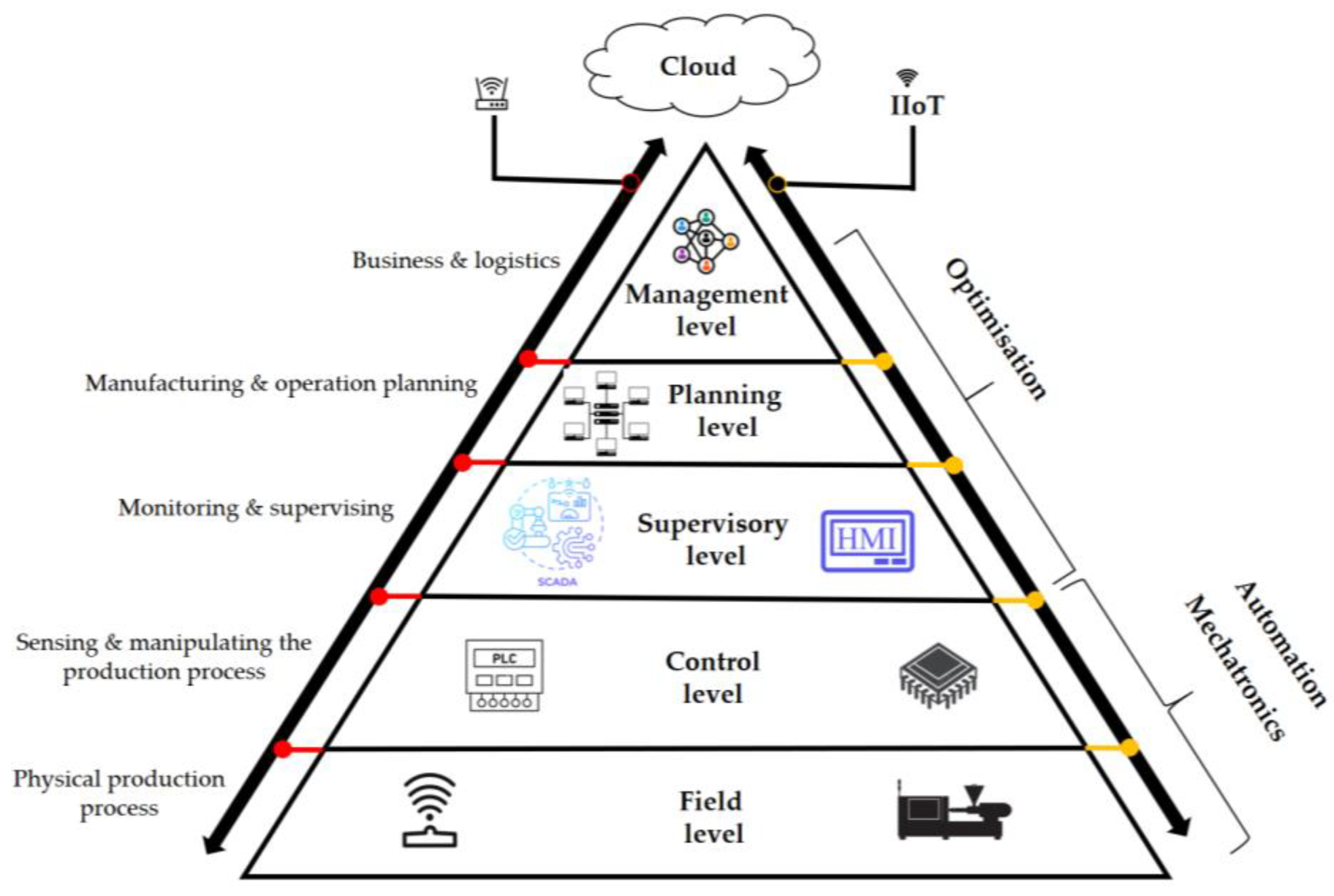

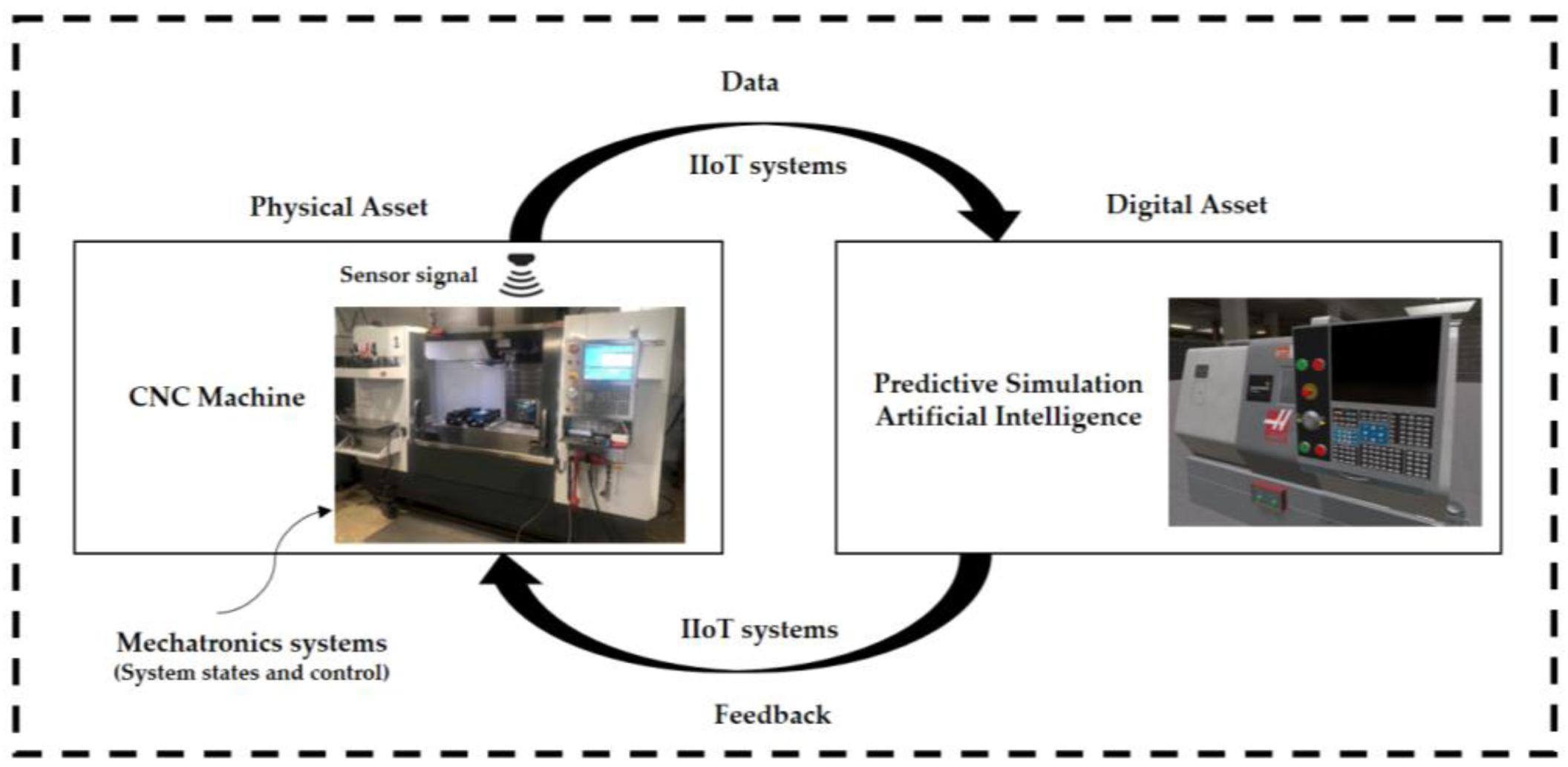

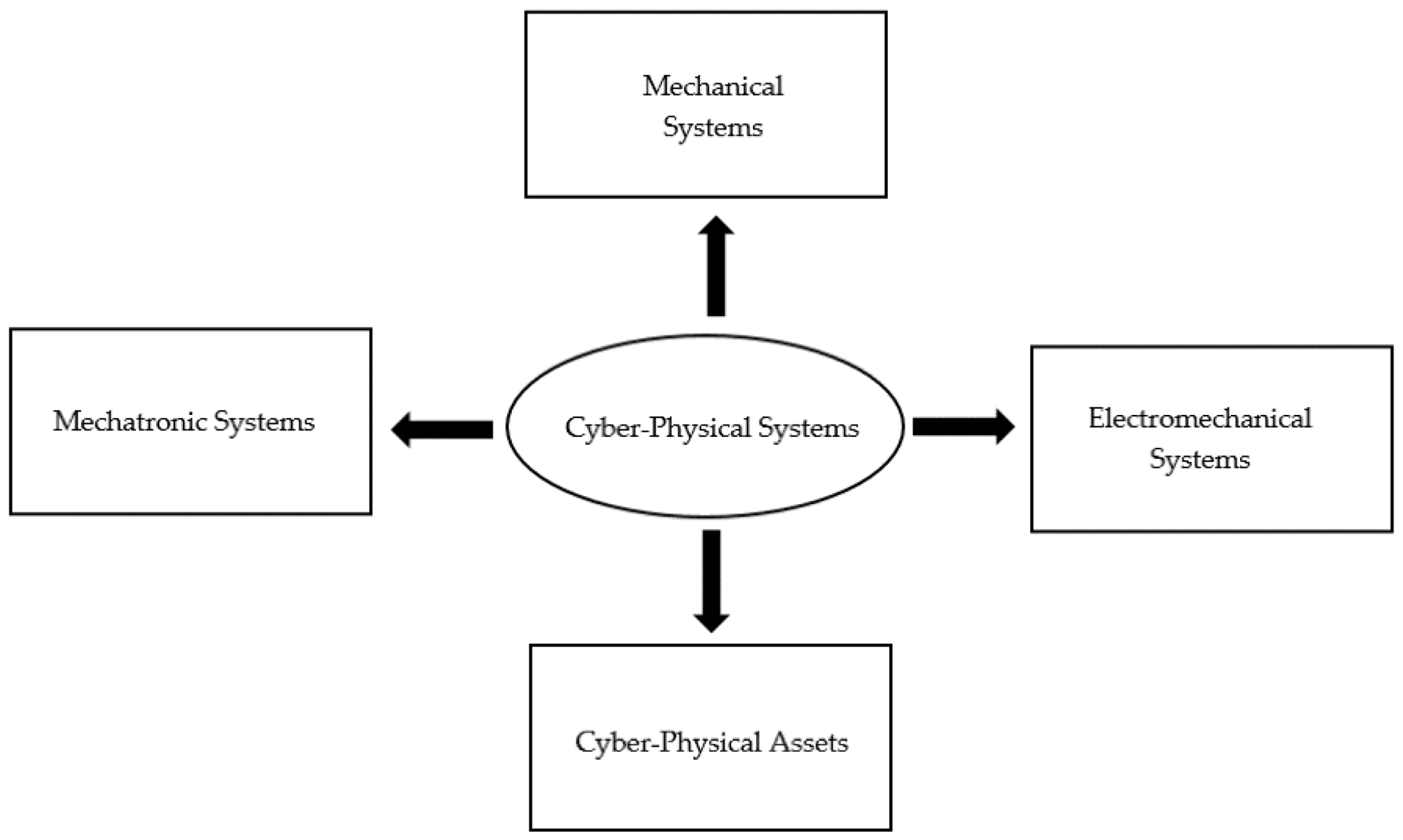

2.1.2. Mechatronics and Industry 4.0

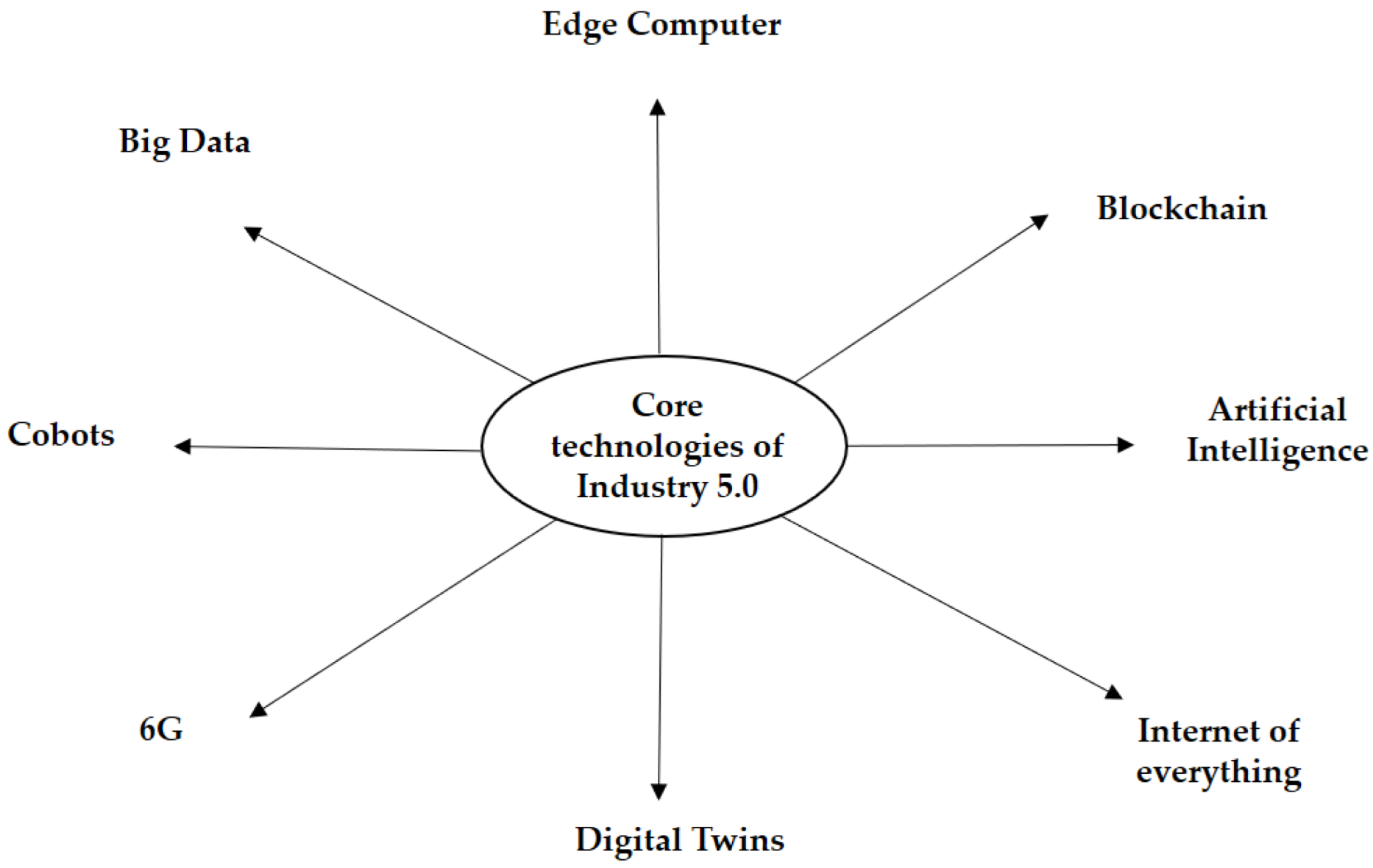

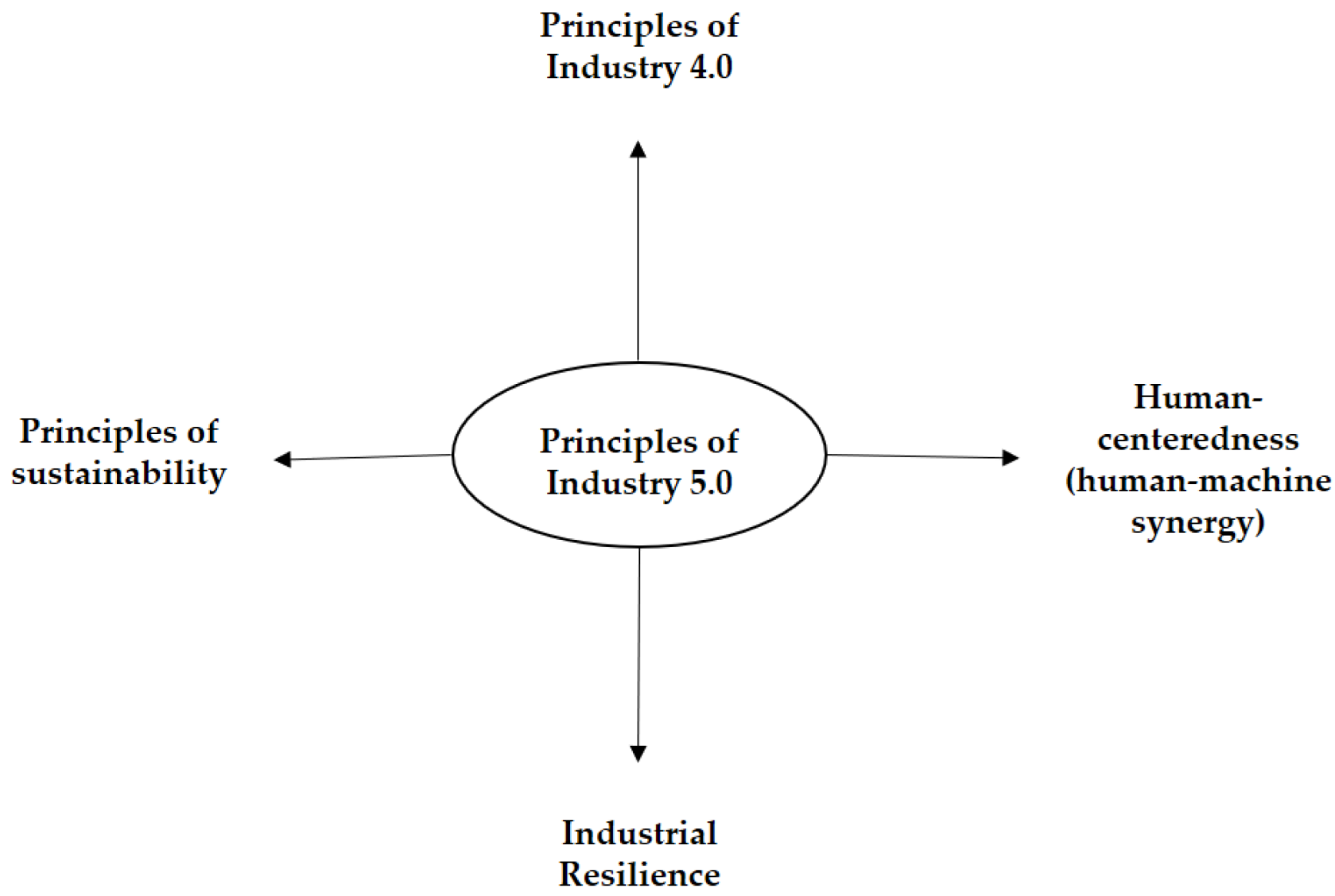

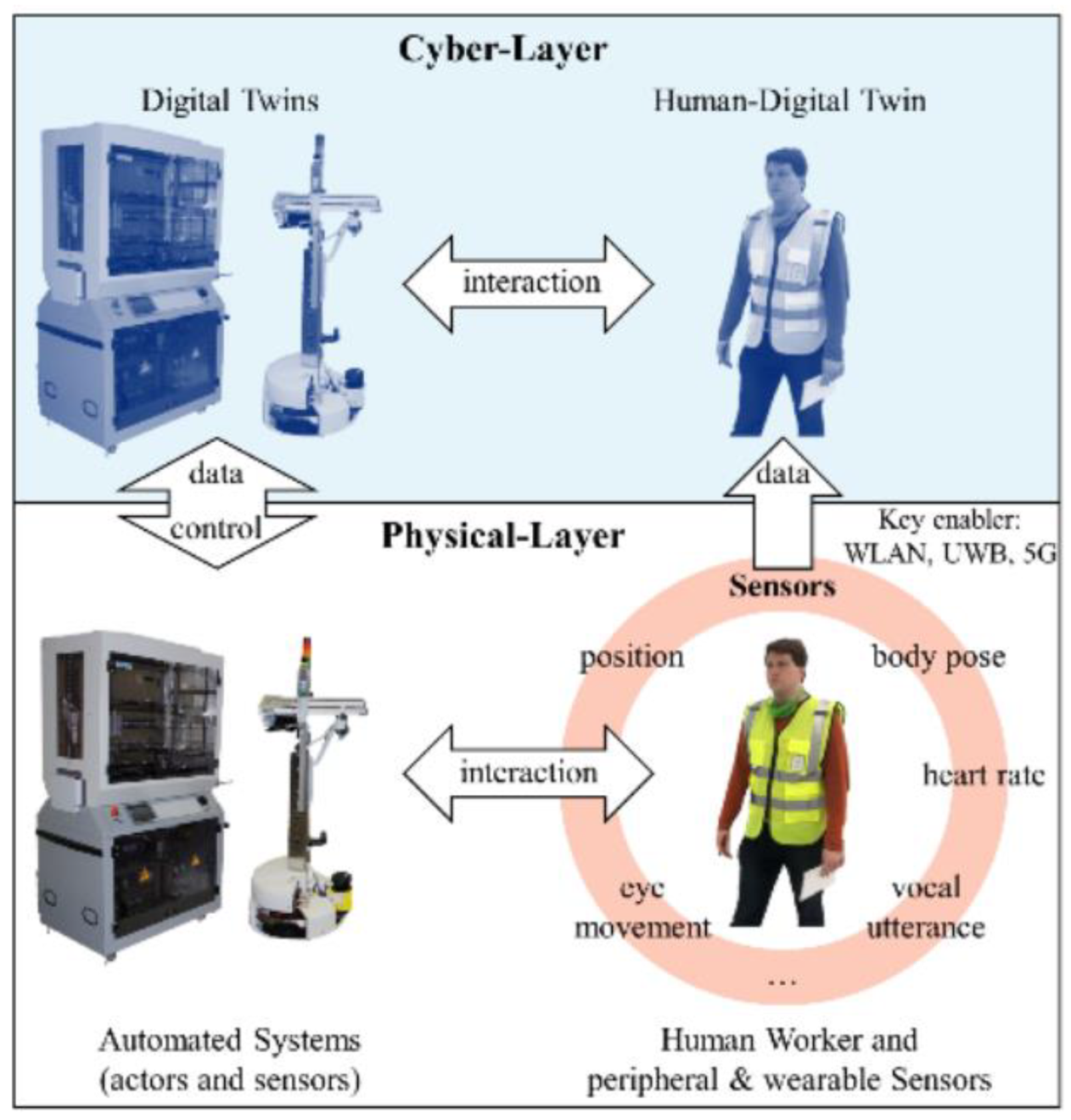

2.1.3. Mechatronics and Industry 5.0

2.1.4. Evolution of Mechatronics

2.2. Mechatronics and Machines 3.0, 4.0, and 5.0

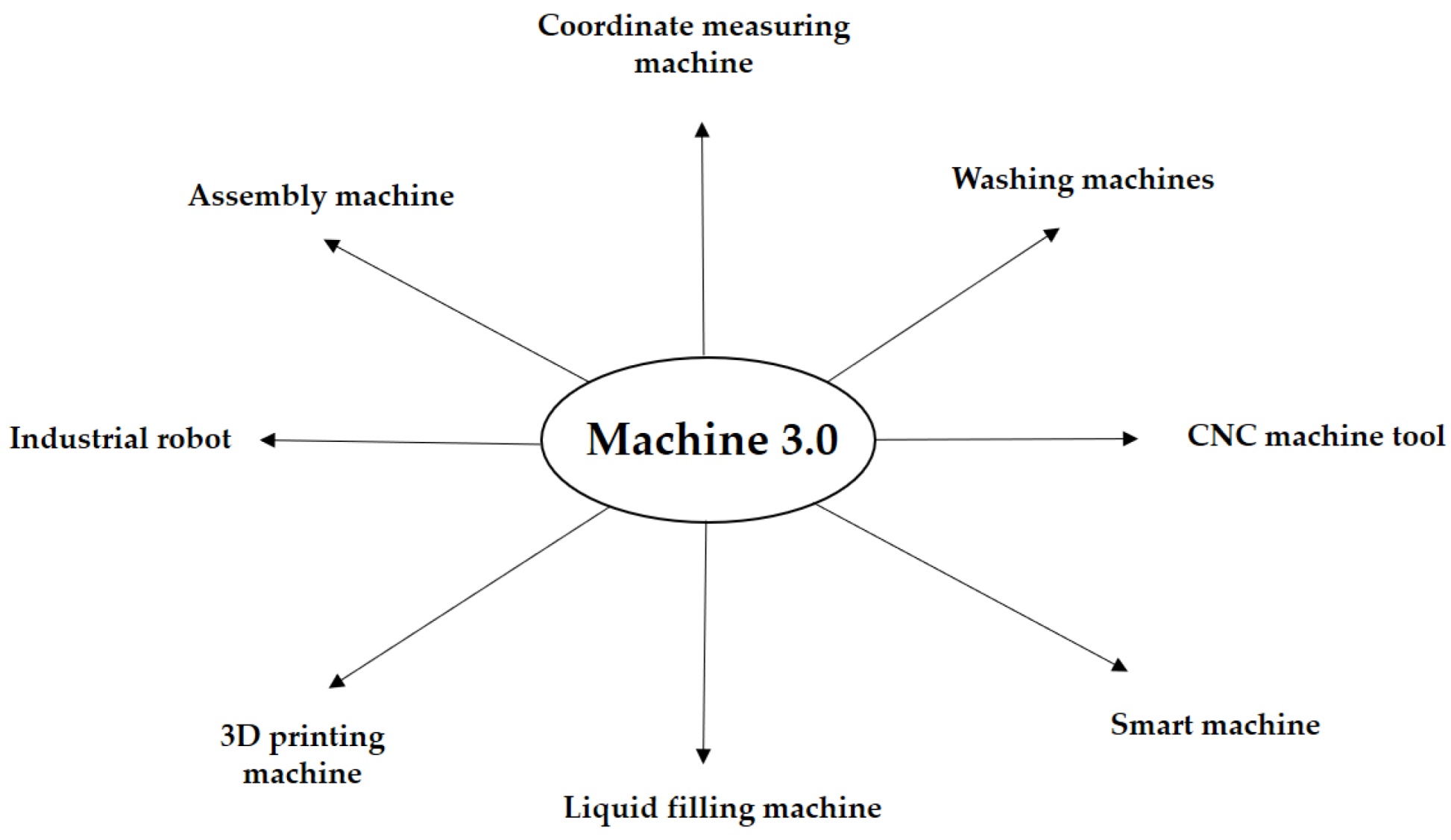

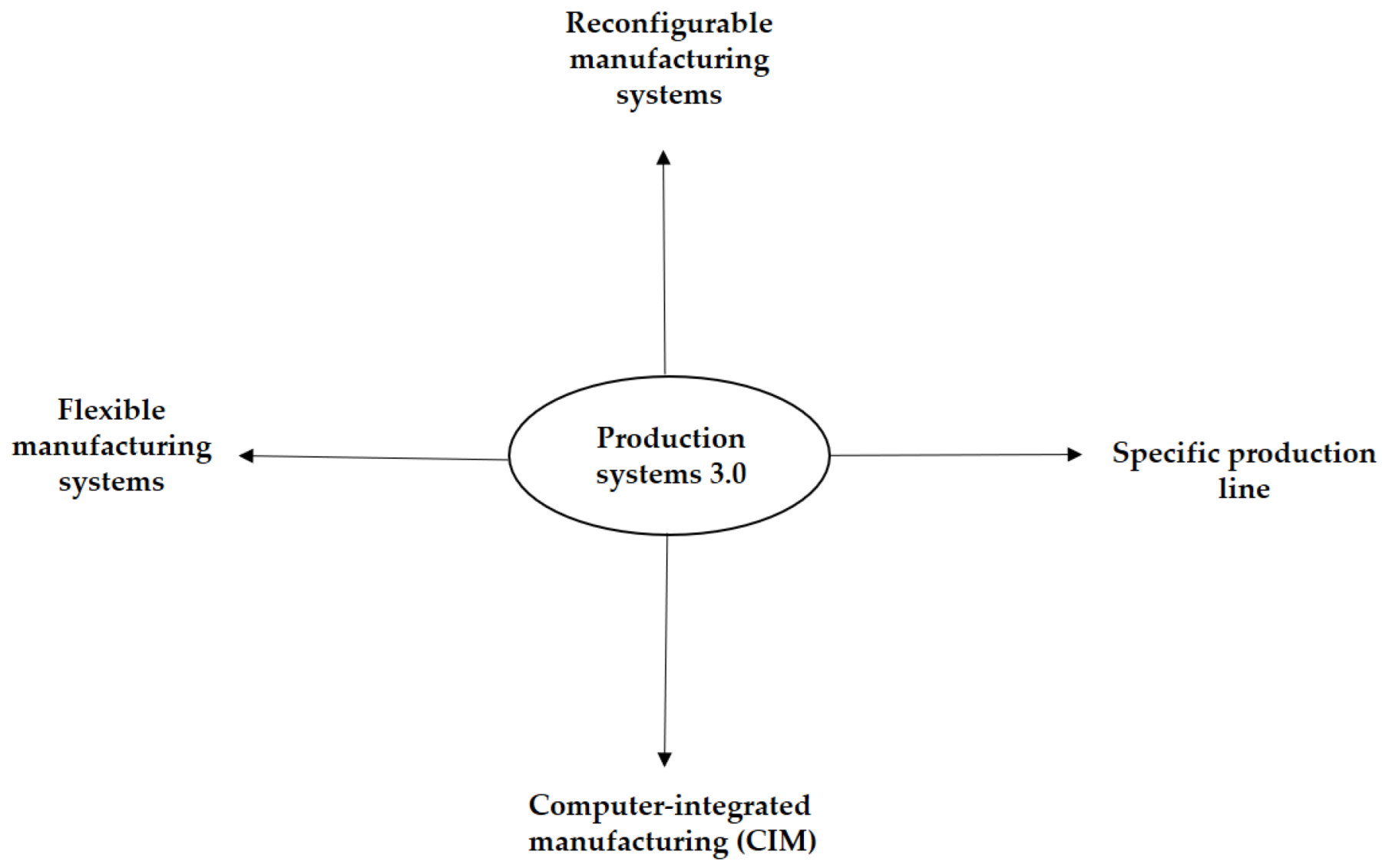

2.2.1. Mechatronics and Machines 3.0.

- (1)

- Mass production gave way to flexible production.

- (2)

- Companies began digitizing their processes with the help of computers (computerization of industry).

- (3)

- Production systems adopted programmable automation.

- (4)

- Mechanical and analog electronic technology gave way to digital electronics.

- (5)

- Companies began to use renewable energies and developed energy efficiency programs.

- (6)

- Industry began a process of decentralization.

- (7)

- Globalization and the development of large corporations began.

2.2.2. Mechatronics and Machines 4.0.

- (1)

- Production processes have moved from moderate digitization to high digitization (total digitization of the value chain).

- (2)

- Factories with advanced conventional automation have been transformed into smart factories.

- (3)

- Manufacturing systems are fully integrated (horizontally and vertically) and operations are carried out in real time.

- (4)

- Artificial Intelligence focuses on improving and increasing the efficiency of machines and production systems.

- (5)

- Production systems went from conventional automation to smart, optimized automation.

- (6)

- Production is customized.

- (7)

- Traditional connectivity gave way to hyperconnectivity (interconnectivity and interoperability in production systems).

- (8)

- Production is optimized and highly energy efficient.

2.2.3. Mechatronics and 5.0 Machines.

- (1)

- Artificial Intelligence is oriented towards humans and human-machine synergy.

- (2)

- Production systems are hyperconnected (they have high connectivity and real-time communication).

- (3)

- Production systems are hyperpersonalized.

- (4)

- Cognitive systems are integrated into production systems.

- (5)

- Automation is intelligent and has the ability to make decisions autonomously.

- (6)

- Manufacturing systems are highly digitized.

- (7)

- They inherit technical characteristics from Industry 4.0 (enabling technologies such as IIoT, cobots, augmented reality, etc.).

- (8)

- Manufacturing becomes resilient.

- (9)

- Sustainable practices in manufacturing processes are mandatory.

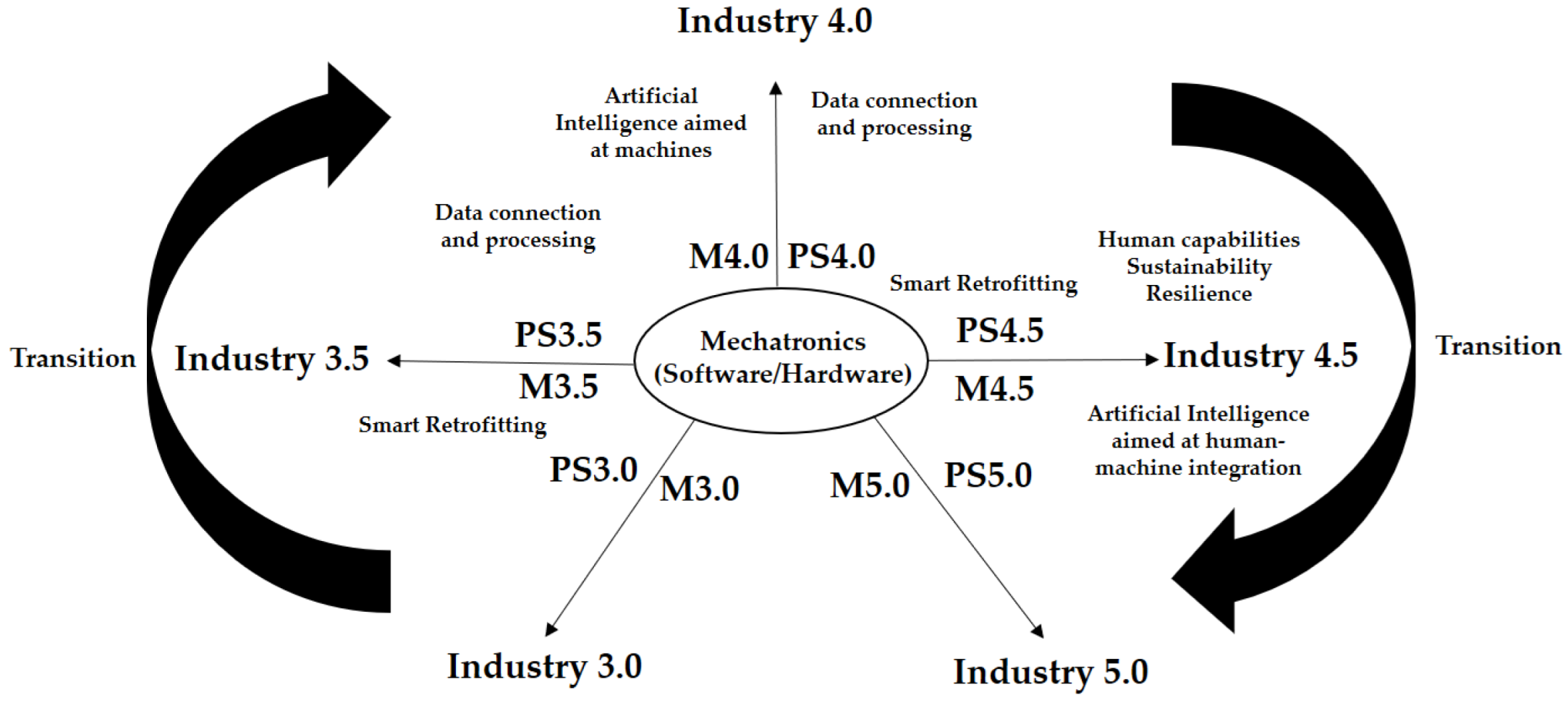

2.3. Mechatronics and Technological Transitions

2.2.1. Mechatronics and Industry 3.5

2.3.2. Mechatronics and Industry 4.5

3. Results

3.1. Industrial Revolutions.

3.2. Industrial Revolutions and Mechatronics.

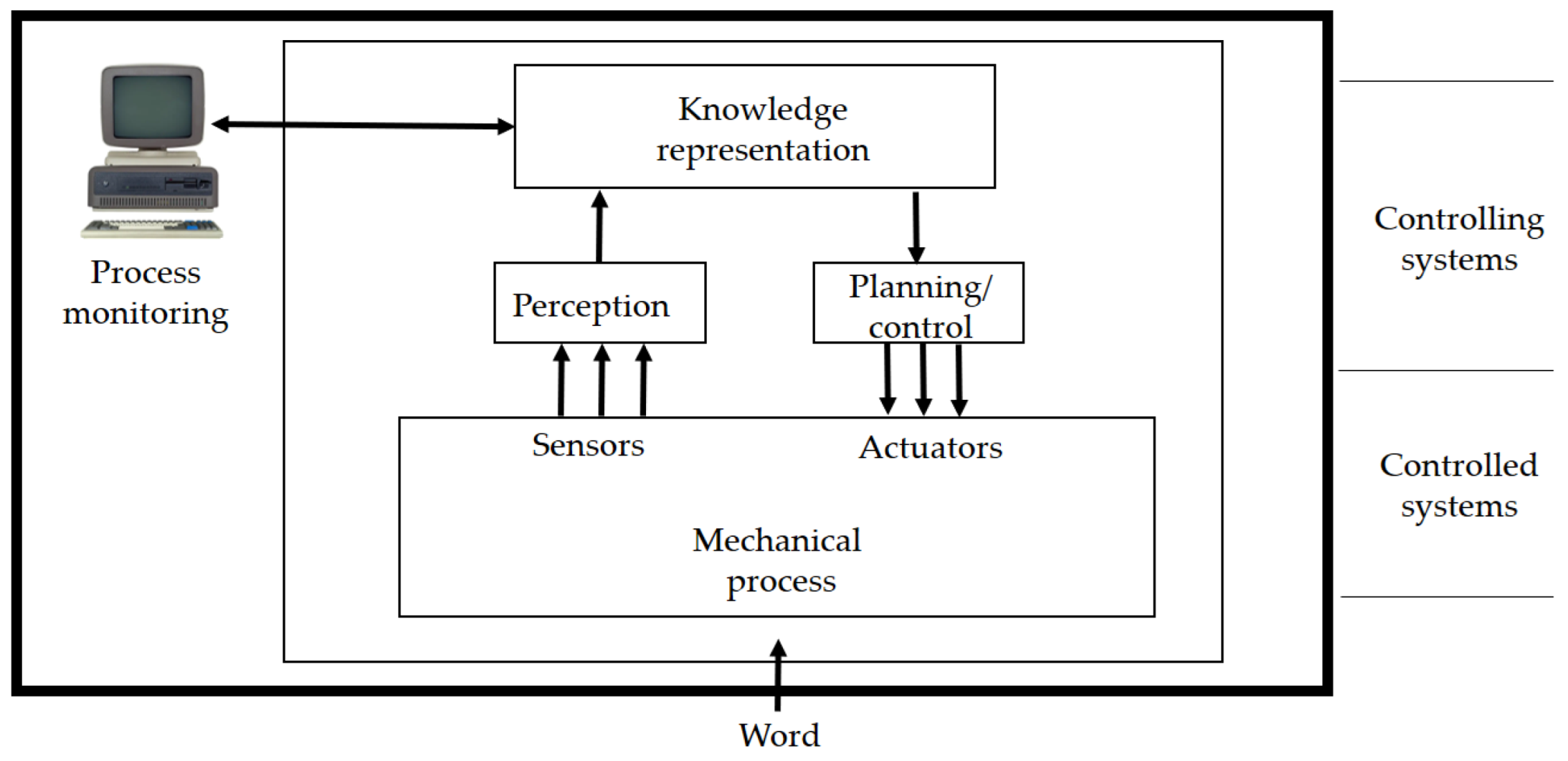

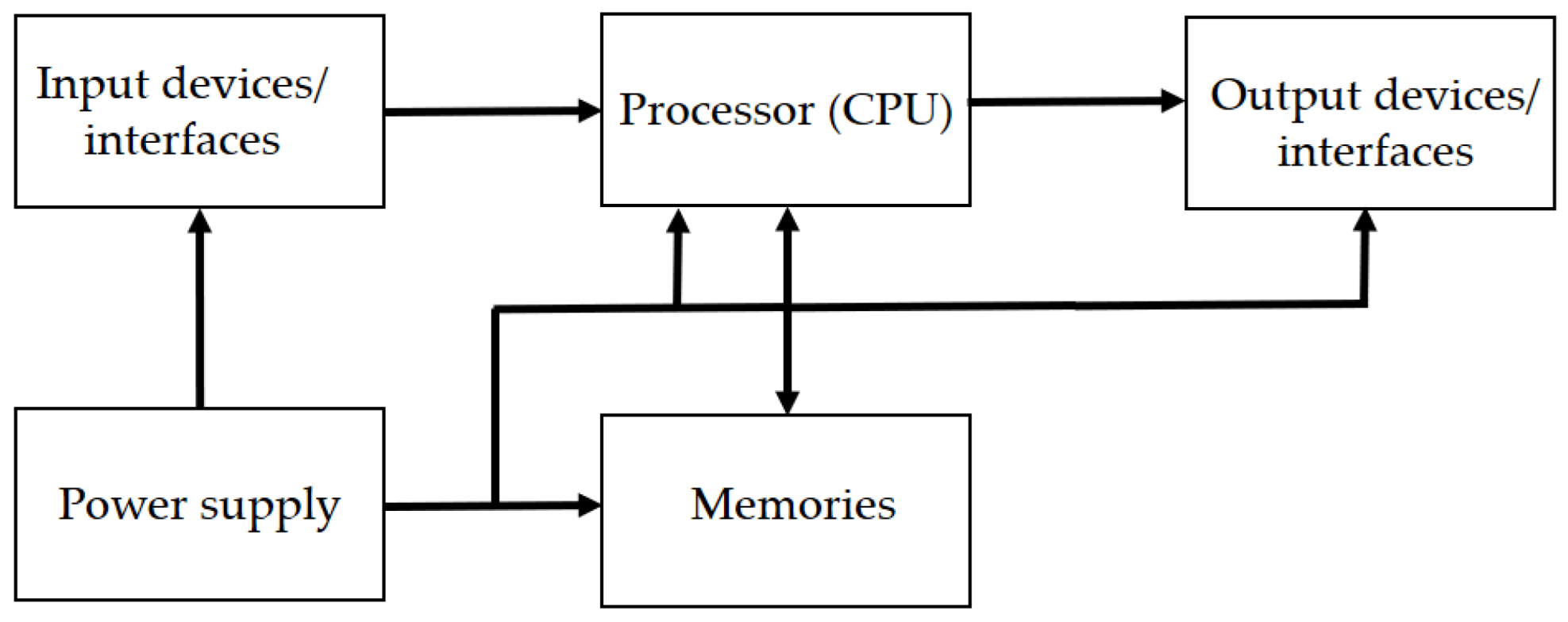

3.2.1. The Third Industrial Revolution and Mechatronics.

3.2.2. The Fourth Industrial Revolution and Mechatronics.

3.2.3. The Fifth Industrial Revolution and Mechatronics.

3.2.4. Roadmap for Mechatronics.

3.3. Classification of Machines.

3.3.1. Machines 3.0.

3.3.2. Machines 4.0.

3.3.3. Machines 5.0.

Machines 3.5 and 4.5.

4. Discussion

4.1. Industrial Paradigms.

4.2. Mechatronics Engineering and Industries 3.0, 4.0, and 5.0.

5. Conclusions

- The journey taken through the evolution of mechatronics was essential to understanding the contributions of this field of engineering to Industries 3.0, 4.0, and 5.0. Mechatronics has been linked to much of the technological development from 1970 to the present, making it an essential field of knowledge for the development of industries.

- Mechatronics provides hardware/software integration and its integrative methodology for the development of Industry 4.0 and 5.0 technologies. Cyber-physical systems, human digital twins, and cobots are examples of modern technologies based on mechatronics.

- Mechatronics accompanied Industry 3.0 for 30 years and, at the same time, evolved from its conception, which integrated mechanics and electronics, to the sophisticated applications that are currently being developed under its current disciplinary approach. Mechatronics has established itself as one of the disciplinary pillars of Industries 4.0 and 5.0.

- Currently, the industry is influenced by three active industrial revolutions and two transitions. This situation made it necessary to propose a classification of machines and production systems based on the premises of each industrial paradigm, in order to understand the technical, operational, and design characteristics of industrial production technology. Machines 3.0, 4.0, and 5.0 were defined to identify the machinery related to each premise of each industrial revolution, and mechatronics is related to each of the classified machines and production systems.

- Various companies around the world are migrating from one industrial revolution to another. Industries 3.5 and 4.5 represent the transitions from Industry 3.0 to Industry 4.0 and from Industry 4.0 to Industry 5.0. One of the techniques used to carry out these transitions is Smart Retrofitting. In this way, a 3.5 machine is a 3.0 machine that has been reconditioned to perform Industry 4.0 tasks.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PS4.0 | Production System 4.0 |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| M3.0 | Machine 3.0 |

| IIoT | Industrial Internet of Things |

References

- Elnadi, M.; Abdallah, Y.O. Industry 4.0: critical investigations and synthesis of key findings. Manag Rev Q, 2024, 74, 711–744.

- Soori, M.; Arezoo, B.; Dastres, R. Virtual manufacturing in industry 4.0: A review. Data Sci and Manag, 2024, 7(1), 47-63.

- Bongomin, O.; Ocen, G.G.; Oyondi, E.; Musinguzi, A.; Omara, T. Exponential Disruptive Technologies and the Required Skills of Industry 4.0. J. Eng. 2020, 2020, 4280156.

- Stankovski, S.; Ostojic, G.; Zhang, X; Baranovski, I.; Tegeltija, S.; Horvat, S. Mechatronics, Identification Technology, Industry 4.0 and Education. In IEEE 2019 18th International Symposium INFOTEH-JAHORINA (INFOTEH), Sarajevo, Bosnia. 20-22 March, 2019; pp. 1-4. [CrossRef]

- Samanta, B. Introduction to mechatronics: an integrated approach. Springer Nature Switzerland AG, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Kuru, K.; Yetgin, H. Transformation to advanced mechatronics systems within new industrial revolution: A novel framework in automation of everything (AoE). IEEE Access, 2019, 7, 41395-41415.

- Rahman, M.; Rahman, M.M.; Sohel, M.R.; Farhan, A.; Huq, E.; Mahbub, F. Conclusion and Future Trends of Mechatronics. In: Rahman, M.M., Mahbub, F., Tasnim, R., Saleheen, R.U. (eds) Mechatronics. Emerging Trends in Mechatronics. Springer, Singapore. 2024. [CrossRef]

- George, A. S.; George, A. H. Industrial revolution 5.0: the transformation of the modern manufacturing process to enable man and machine to work hand in hand., 2020, 15 (9), 1525-68128.

- Dhakal, S.P. Fifth industrial revolution and the future of education and employment. Qual Quant, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Nasir, V.; Hosseini, A.; Binfield, L.; Hasani, N.; Ghotb, S.; Diederichs, V.; O Fox, G.; McCann, A.J.; Riggio, M.; Chandler, K.; Hansen, E. (2025). Human-centric Industry 5.0 manufacturing: a multi-level framework from design to consumption within Society 5.0. Int. J. Sustain. Eng., 2025, 18(1), 2551000. [CrossRef]

- Ryalat, M.; Franco, E.; Elmoaqet, H.; Almtireen, N.; Al-Refai, G. The Integration of Advanced Mechatronic Systems into Industry 4.0 for Smart Manufacturing. Sustainability, 2024, 16, 8504. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Tzu, H.; Hong, G. A Conceptual Framework for “Industry 3.5” to Empower Intelligent Manufacturing and Case Studies. Procedia Manuf. 2017, 11, 2009–2017.

- Xu, X.; Lu, Y.; Vogel-Heuser, B.; Wang, L. Industry 4.0 and Industry 5.0—Inception, conception and perception. J. Manuf. Syst., 2021, 61, 530-535.

- Junlapeeya, P.; Lorga, T.; Santiprasitkul, S.; Tonkuriman, A. A Descriptive Qualitative Study of Older Persons and Family Experiences with Extreme Weather Conditions in Northern Thailand. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health, 2023, 20, 6167. [CrossRef]

- Hamad, M.; and Jawad, K. The Fourth Industrial Revolution: A Historical and Conceptual Review, J. ECONOM. ADM. SCI, 2024, 30(141), 154–172. [CrossRef]

- Malik, A.; Sharma, S.; Batra, I.; Sharma, C.; Kaswan, M. S.; Garza-Reyes, J. A. Industrial revolution and environmental sustainability: an analytical interpretation of research constituents in Industry 4.0. Int. J. Lean Six Sigma, 2024, 15(1), 22-49.

- Musarat, M.A.; Irfan, M.; Alaloul, W.S.; Maqsoom, A.; Ghufran, M. A Review on the Way Forward in Construction through Industrial Revolution 5.0. Sustainability, 2023, 15, 13862. [CrossRef]

- Wimmer, M.A.; Viale Pereira, G.; Ronzhyn, A.; Spitzer, V. Transforming Government by Leveraging Disruptive Technologies. JeDEM—Ejournal Edemocracy Open Gov. 2020, 12, 87–113.

- Jiménez, E.; Limón, P.A.; Ambrosio, A.; Ochoa, F.J.; Delfín, J.J.; Lucero, B..; Martínez, V.M. Mechanics 4.0 and Mechanical Engineering Education. Machines, 2024, 12, 320. [CrossRef]

- Ziatdinov, R.; Atteraya, M.S.; Nabiyev, R. The Fifth Industrial Revolution as a Transformative Step towards Society 5.0. Societies, 2024, 14, 19. [CrossRef]

- Mhlanga, D. Stakeholder Capitalism, the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR), and Sustainable Development: Issues to Be Resolved. Sustainability, 2022, 14, 3902. [CrossRef]

- . Islam, M. M.; Hossain, I.; Martin, M. H. H. The role of iot and artificial intelligence in advancing nanotechnology: a brief review. Control Syst. Optimization Lett., 2024, 2(2), 204-210.

- Mokwana, D. R.; van der Poll, J. A. Towards a Framework for Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) Cyber Physical Systems (CPSs). Strategic Alliance Between, 2022, 189.

- Lee, E.A. The Past, Present and Future of Cyber-Physical Systems: A Focus on Models. Sensors, 2015, 15, 4837-4869. [CrossRef]

- Grabowska, S.; Saniuk, S.; Gajdzik, B. Industry 5.0: improving humanization and sustainability of Industry 4.0. Scientometrics, 2022, 127(6), 3117-3144.

- George, A. S.; George, A. H. Industrial revolution 5.0: the transformation of the modern manufacturing process to enable man and machine to work hand in hand. Journal of Seybold Report, 2020, 15 (9), 214-234.

- Yadav, R.; Arora, S.; Dhull, S. A path way to Industrial Revolution 6.0. Int. J. Mech. Eng. 2022, 7, 1452–1459.

- Chourasia, S.; Tyagi, A.; Pandey, S. M.; Walia, R. S.; Murtaza, Q. Sustainability of Industry 6.0 in global perspective: benefits and challenges. Mapan, 2020, 37(2), 443-452.

- Mohajan, H. The First Industrial Revolution: Creation of a New Global Human Era. Int. J. Soc. Sci. 2019, 5 (4), 377-387.

- Mokyr, J.; Strotz, R. H. The second industrial revolution, 1870-1914. Storia dell’economia Mondiale, 1998, 21945(1), 219-245.

- Nnodim, T. C.; Arowolo, M. O.; Agboola, B. D.; Ogundokun, R. O.; Abiodun, M. K. (2021). Future trends in mechatronics. Int. J. Robot Autom., 2021, 1(10), 24. [CrossRef]

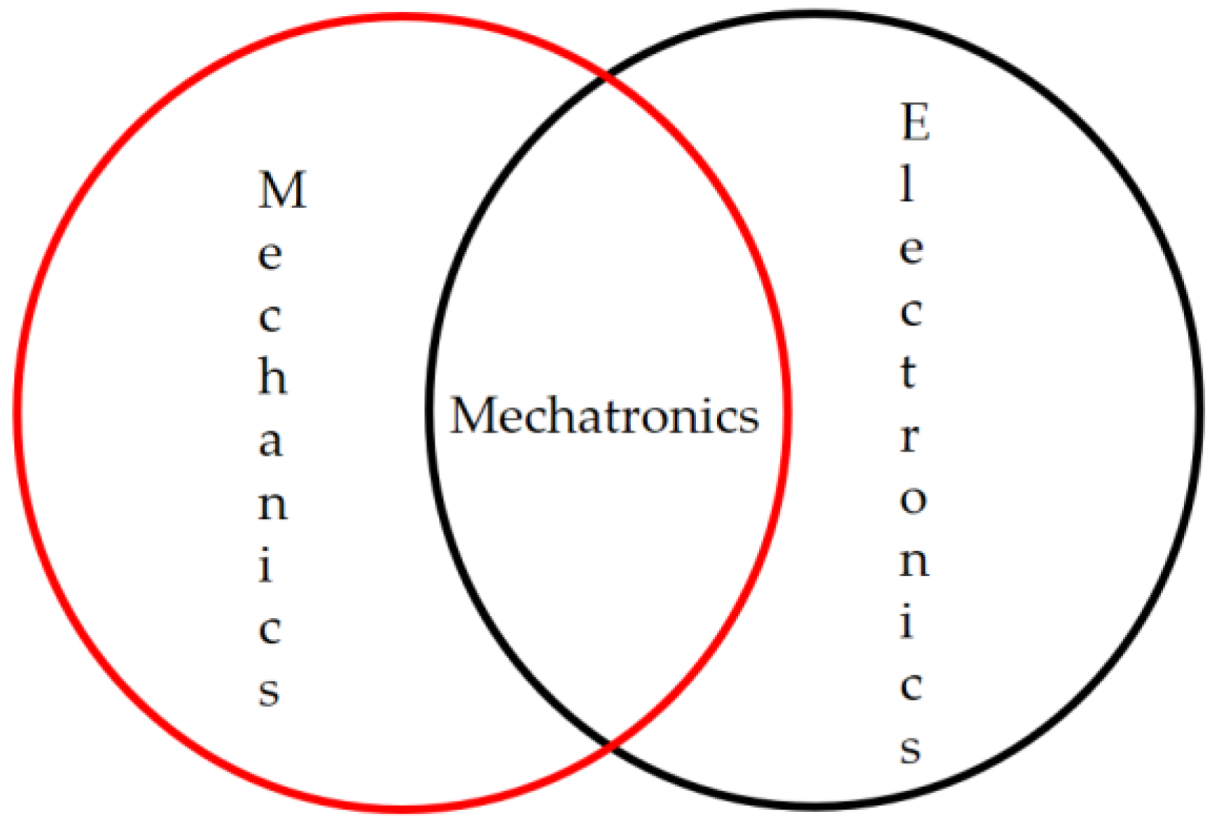

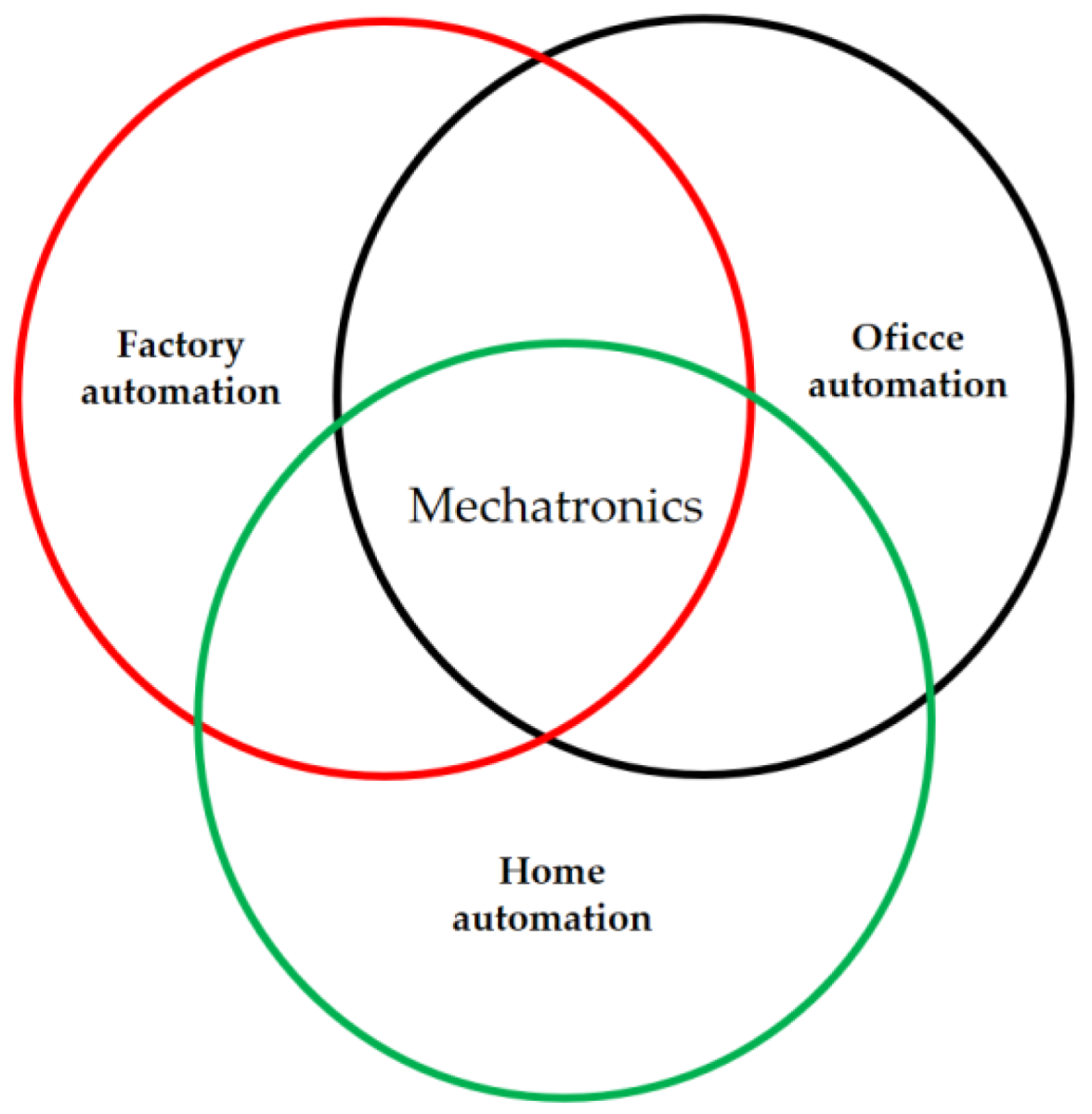

- Pannaga, N., Ganesh, N., & Gupta, R. Mechatronics—an introduction to mechatronics. Int. J. Eng, 2013, 2, 128-134.

- Hunt, V.D. Introduction to Mechatronics. In: Mechatronics: Japan’s Newest Threat. Springer, Boston, MA. 1988. [CrossRef]

- Harashima, F.; Tomizuka, M.; Fukuda, T. Mechatronics – What is ist, why and how? An editorial, IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron, 1996, 1, 1–4.

- Isermann, R. Mechatronic systems: concepts and applications. Transactions of the Institute of Measurement and Control, 2000, 22(1), 29-55.

- Shimoga, G.; Kim, T.-H.; Kim, S.-Y. An Intermetallic NiTi-Based Shape Memory Coil spring for Actuator Technologies. Metals, 2021, 11, 1212. [CrossRef]

- Milecki, A. 45 Years of Mechatronics – History and Future. In: Szewczyk, R., Zieliński, C., Kaliczyńska, M. (eds) Progress in Automation, Robotics and Measuring Techniques. ICA 2015. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing, vol 350. Springer, Cham. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Bradley, D.; Dawson, D.; Burd, D.; Loader, A. Mechatronics electronics in products and processes. Chapman & Hall, London. 1991.

- Hou, Y.; Li, Q.; Zhang, C.; Lu, G.; Ye, Z.; Chen, Y.; Cao, D. (2021). The state-of-the-art review on applications of intrusive sensing, image processing techniques, and machine learning methods in pavement monitoring and analysis. Engineering, 2021, 7(6), 845-856.

- Friedrich, C.R.; Fang, J.; Warrington, R.O. (1997). Micromechatronics and the miniaturization of structures, devices, and systems. IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag. Manuf. Technol. Part C: 1997, 20(1), 31–38. [CrossRef]

- Habib, M.K. Mechatronics Engineering the Evolution, the Needs and the Challenges. In IEEE IECON 2006 - 32nd Annual Conference on IEEE Industrial Electronics - Paris, France, 06-10 November, 2006; pp. 4510–4515. [CrossRef]

- Zaeh, M.; Gao, R. Mechatronics. In: Laperrière, L., Reinhart, G. (eds) CIRP Encyclopedia of Production Engineering. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Ryalat, M.; Franco, E.; Elmoaqet, H.; Almtireen, N.; Al-Refai, G. The Integration of Advanced Mechatronic Systems into Industry 4.0 for Smart Manufacturing. Sustainability, 2024, 16, 8504. [CrossRef]

- Habib, M. K. Mechatronics - A unifying interdisciplinary and intelligent engineering science paradigm," in IEEE Ind. Electron. Mag., 2007, 1(2),12-24. [CrossRef]

- Tomizuka, M. Mechatronics: from the 20th to 21st century. Control Eng. Pract, 2022, 10(8), 877-886.

- Winner, R.I., Pennel, J.P., Bertrand, H.E., and Slusarczuk, M.M.G. The role of concurrent engineering in weapons system acquisition. IDA Report R-388, Institute of Defense Analysis, Alexandra, Virginia, USA. 1988.

- Morales-Cruz, C.; Ceccarelli, M.; Portilla-Flores, E.A. An Innovative Optimization Design Procedure for Mechatronic Systems with a Multi-Criteria Formulation. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 8900. https:// doi.org/10.3390/app11198900.

- De Oliveira, L. P. R.; Da Silva, M. M.; Sas, P.; Van Brussel, H.; Desmet, W. Concurrent mechatronic design approach for active control of cavity noise. J. Sound. Vib., 2008 314(3), 507-525.

- Mamilla, V. R., Rao, C. S., Rao, G. L. N., Venkatesh, V. Integration of mechanical and electronic systems in mechanical engineering. In International Conference on Multi Body Dynamics 2011 Vijayawada, India, 24-26 february, 2011; pp. 493–501.

- Isermann, R. (2009). Mechatronic Systems – A Short Introduction. In: Nof, S. (eds) Springer Handbook of Automation. Springer Handbooks. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. 2009. [CrossRef]

- Shibu K.V. Introduction to Emdedded Systems. Mc Graw Hilll Education. New Delhi. India, 2009.

- Khatri, A. R. Implementation, verification and validation of an OpenRISC-1200 Soft-core Processor on FPGA. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl., 2019, 10(1), 480-487. [CrossRef]

- Liagkou, V.; Stylios, C.; Pappa, L.; Petunin, A. Challenges and Opportunities in Industry 4.0 for Mechatronics, Artificial Intelligence and Cybernetics. Electronics, 2021, 10, 2001. [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, G.M.; Habib, L.; Garcia, F.A.; Montemayor, F. Industry 4.0 and Engineering Education: An Analysis of Nine Technological Pillars Inclusion in Higher Educational Curriculum. In Best Practices in Manufacturing Processes, 1st ed.; García, J., Rivera, L., González, R., Leal, G., Chong, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019, 525–543.

- Farhan, A.; Barua, P.; Saleheen, R.U.; Tasnim, R.; Rahman, M.M.; Rahman, M. Introduction to Mechatronics. In Mechatronics. Emerging Trends in Mechatronics, 1st ed., Rahman, M.M., Mahbub, F., Tasnim, R., Saleheen, R.U. (eds). Springer, Singapore. 2024, 1-19. [CrossRef]

- Ryalat, M.; Franco, E.; Elmoaqet, H.; Almtireen, N.; Al-Refai, G. The Integration of Advanced Mechatronic Systems into Industry 4.0 for Smart Manufacturing. Sustainability, 2024, 16, 8504. [CrossRef]

- Ugarte, B.S.D.; Artiba, A.; Pellerin, R. Manufacturing execution system—a literature review. Prod. Plan Control, 2009, 20(6), 525–539.

- Sadik, A.R.; Urban, B. Combining Adaptive Holonic Control and ISA-95 Architectures to Self-Organize the Interaction in a Worker-Industrial Robot Cooperative Workcell. Future Internet, 2017, 9, 35. [CrossRef]

- Ryalat, M.; Franco, E.; Elmoaqet, H.; Almtireen, N.; Al-Refai, G. The Integration of Advanced Mechatronic Systems into Industry 4.0 for Smart Manufacturing. Sustainability, 2024, 16, 8504. [CrossRef]

- Ryalat, M.; ElMoaqet, H.; AlFaouri, M. Design of a Smart Factory Based on Cyber-Physical Systems and Internet of Things towards Industry 4.0. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 2156. [CrossRef]

- Ragavan, S. K. V.; Shanmugavel, M. Engineering cyber-physical systems—Mechatronics wine in new bottles?. In 2016 IEEE International Conference on Computational Intelligence and Computing Research (ICCIC), Chennai, India,15-17 December, 2016, pp. 1-5.

- Neema, S.; Simko, G.; Levendovszky, T.; Porter, J.; Agrawal, A.; J. Sztipanovits. J. Formalization of software models for cyber-physical systems. In Proceedings of the 2nd FME Workshop on Formal Methods in Software Engineering, Hyderabad India, 3 June, 2014: pp. 45–51.

- Guerineau, B.; Bricogne, M.; Durupt, A.; Rivest, L. Mechatronics vs. cyber physical systems: Towards a conceptual framework for a suitable design methodology. In Mechatronics (MECATRONICS)/17th International Conference on Research and Education in Mechatronics (REM), Compiegne, France, 15-17 June, 2016; pp. 314-320.

- Escobar, L.; Carvajal, N.; Naranjo, J.; Ibarra, A.; Villacís, C.; Zambrano, M.; Galárraga, F. Design and implementation of complex systems using Mechatronics and Cyber-Physical Systems approaches. In 2017 IEEE International Conference on Mechatronics and Automation (ICMA), Takamatsu, Japan, 06-09 August, 2017; pp. 147-154.

- Liu, Y.; Peng, Y.; Wang, B.; Yao, S.; Liu, Z. Review on cyber-physical systems. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin., 2017, 4(1), 27-40.

- Guerineau, B.; Bricogne, M.; Durupt, A.; Rivest, L. Mechatronics vs. cyber physical systems: Towards a conceptual framework for a suitable design methodology. In 2016 11th France-Japan & 9th Europe-Asia Congress on Mechatronics (MECATRONICS)/17th International Conference on Research and Education in Mechatronics (REM), IEEE, Compiegne, France, 15-17 June, 2016; pp. 314-320.

- Saleheen, R.U.S., Farhan, A., Ramesha, N.Z., Tasnim, R., Erin, M.T.U.R., Shahria, S. Emerging Applications of Mechatronics. In Mechatronics, 1st ed., Rahman, M.M., Mahbub, F., Tasnim, R., Saleheen, R.U. (eds). Springer, Singapore. 2024, 143–160. [CrossRef]

- Lou, S.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, Y.; Zhou, M.; Lv, C. Human-cyber-physical system for Industry 5.0: A review from a human-centric perspective. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng., 2024, 22, 494-511.

- Zeb, S.; Mahmood, A.; Khowaja, S. A.; Dev, K.; Hassan, S. A.; Gidlund, M.; Bellavista, P. Towards defining industry 5.0 vision with intelligent and softwarized wireless network architectures and services: A survey. J. Netw. Comput. Appl., 2024, 223, 103796. [CrossRef]

- Olah, ´ J.; Aburumman, N.; Popp, J.; Khan, M.A.; Haddad, H.; Kitukutha, N. Impact of industry 4.0 on environmental sustainability. Sustainability, 2020, 12 (11). https://doi. org/10.3390/su12114674.

- Pizoń, J.; Gola, A. Human–Machine Relationship—Perspective and Future Roadmap for Industry 5.0 Solutions. Machines, 2023, 11, 203. [CrossRef]

- Maddikunta, P. K. R.; Pham, Q. V.; Deepa, N.; Dev, K.; Gadekallu, T. R.; Ruby, R.; Liyanage, M. Industry 5.0: A survey on enabling technologies and potential applications. J. Ind. Inf. Integr., 2022, 26, 100257. [CrossRef]

- Habib, M. K. Mechatronics in industry 4.0 and 5.0: advancing synergy, innovations, sustainability, and challenges. Mechatronics Tech. 2025, 1: 0002. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M. M.; Khatun, F.; Jahan, I.; Devnath, R.; Bhuiyan, M. A. A. Cobotics: The Evolving Roles and Prospects of Next-Generation Collaborative Robots in Industry 5.0. J. Robot, 2024,1: 2918089.

- Parrott, A.; Warshaw, L. Industry 4.0 and the Digital Twin: Manufacturing Meets its Match. Deloitte University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017, 1–17.

- Menon, D.; Anand, B.; Chowdhary, C. L. Digital Twin: Exploring the Intersection of Virtual and Physical Worlds, IEEE Access, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Rosen, R.; Fischer, J.; Boschert, S. Next generation digital twin: An ecosystem for mechatronic systems? IFAC-Pap., 2019, 52(15), 265-270.

- Wang, B., Zhou, H., Yang, G., Li, X., & Yang, H. Human digital twin (HDT) driven human-cyber-physical systems: Key technologies and applications. Chin. J. Mech. Eng., 2022, 35(1): 11. [CrossRef]

- Lou, S., Hu, Z., Zhang, Y., Feng, Y., Zhou, M., & Lv, C. Human-cyber-physical system for Industry 5.0: A review from a human-centric perspective. IEEE Trans Autom. Sci. Eng., 2024, 22, 494-511.

- Salvi, A.; Spagnoletti, P.; Noori, N.S. Cyber-resilience of Critical Cyber Infrastructures: Integrating digital twins in the electric power ecosystem. Comput. Secur., 2022, 1,112:102507. [CrossRef]

- Haque, M.A.; Shetty, S.; Gold, K.; Krishnappa, B. Realizing Cyber-Physical Systems Resilience Frameworks and Security Practices. In Security in Cyber-Physical Systems. Studies in Systems, Decision and Control, 1st ed., Awad, A.I., Furnell, S., Paprzycki, M., Sharma, S.K. (eds), Springer, Cham. 2021, 1-37. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V. T.; Ngo, V. T.; Phan, D. H.; Tan, P. X. Resilient consensus control for networked robotic manipulators under actuator faults and deception attacks. ISA Trans., 2025, 159, 22-31.

- Kaplinsky, R. Technological Revolution’ and the International Division of Labour in Manufacturing: A Place for the Third World?, Eur. J. Dev. Res., 1989, 1(1), 5-37.

- Zhang, C.; Yang, J. Third Technological Revolution. In: A History of Mechanical Engineering. 1st ed., Springer, Singapore. 2020, 299-349. [CrossRef]

- Nitzan, R. Programmable industrial automation. IEEE Trans. Comput., 1976, 100(12), 1259-1270.

- Taalbi, J. Origins and Pathways of Innovation in the Third Industrial Revolution. Ind. Corp. Change, 2019, 28 (5), 1125-1148.

- Altenpohl, D. G. Informatization of industry and society: The third industrial revolution. Int. J. Technol. Manag., 1986, 1(3), 327-340.

- Al M.A.; Guo, G.; Bi, C. Hard disk drive: mechatronics and control. CRC press. 2017.

- Roberts, G. (1998). Intelligent mechatronics. Control Eng. Pract., 1988, 9(6), 257-264.

- Dashchenko, A. I. Reconfigurable manufacturing systems and transformable factories. Berlin, Springer, 2006.

- Hermann, M.; Pentek, T.; Otto, B. Design principles for industrie 4.0 scenarios. In 2016 49th Hawaii international conference on system sciences (HICSS). IEEE. 2016, 3928-3937.

- Cañas, H.; Mula, J.; Díaz-Madroñero, M.; Campuzano-Bolarín, F. Implementing industry 4.0 principles. Comput. Ind. Eng., 2021, 158, 107379.

- Zafar, M. H.; Langås, E. F.; Sanfilippo, F. Exploring the synergies between collaborative robotics, digital twins, augmentation, and industry 5.0 for smart manufacturing: A state-of-the-art review. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf., 2024, 89, 102769.

- Yamaguchi, K.; Inaba, K. Intelligent and Collaborative Robots. In: Nof, S.Y. (eds) Springer Handbook of Automation. Springer Handbooks. Springer, Cham. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Gong, W.; Xiang, H.; Chen, Y.; Li, D.; Wang, Y. Cloud-Based AGV Control System. In: Zhang, X., Liu, G., Qiu, M., Xiang, W., Huang, T. (eds) Cloud Computing, Smart Grid and Innovative Frontiers in Telecommunications. CloudComp SmartGift 2019. Lecture Notes of the Institute for Computer Sciences, Social Informatics and Telecommunications Engineering, vol 322. Springer, Cham. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Sayeed, A.; Verma, C.; Kumar, N.; Koul, N.; Illés, Z. Approaches and Challenges in Internet of Robotic Things. Future Internet, 2022, 14, 265. [CrossRef]

- Iranshahi, K.; Brun, J.; Arnold, T.; Sergi, T.; Müller, U. C. Digital Twins: Recent Advances and Future Directions in Engineering Fields. Intell. Syst. Appl. , 2025, 200516.

- Farhadi, A.; Lee, S.K.H.; Hinchy, E.P.; O’Dowd, N.P.; McCarthy, C.T. The Development of a Digital Twin Framework for an Industrial Robotic Drilling Process. Sensors, 2022, 22, 7232.

- Kuru, K.; Yetgin, H. Transformation to advanced mechatronics systems within new industrial revolution: A novel framework in automation of everything (AoE). IEEE Access, 2019, 7, 41395-41415.

- Bergert, M.; Kiefer, J. Mechatronic data models in production engineering. IFAC Proceedings Volumes, 2010, 43(4), 60-65.

- Alguliyev, R.; Imamverdiyev, Y.; Sukhostat, L. Cyber-physical systems and their security issues. Comput. Ind., 2018, 100, 212-223.

- Zizic, M.C.; Mladineo, M.; Gjeldum, N.; Celent, L. From Industry 4.0 towards Industry 5.0: A Review and Analysis of Paradigm Shift for the People, Organization and Technology. Energies, 2022, 15, 5221. [CrossRef]

- Taesi, C.; Aggogeri, F.; Pellegrini, N. COBOT Applications—Recent Advances and Challenges. Robotics, 2023, 12, 79. [CrossRef]

- Méndez, J. B.; Perez, C.; Heras, J. V. S.; Pérez, J. J. Robotic pick-and-place time optimization: Application to footwear production. IEEE Access, 2020, 8, 209428-209440.

- Okegbile, S. D.; Cai, J.; Niyato, D.; Yi, C. Human digital twin for personalized healthcare: Vision, architecture and future directions. IEEE Netw. , 2022, 37(2), 262-269.

- Löcklin, A.; Jung, T.; Jazdi, N.; Ruppert, T.; Weyrich, M. Architecture of a human-digital twin as common interface for operator 4.0 applications. Procedia CIRP, 2021, 104, 458-463.

- Bousdekis, A.; Apostolou, D.; Mentzas, G. A human cyber physical system framework for operator 4.0–artificial intelligence symbiosis. Manuf. Lett., 2020, 25, 10-15.

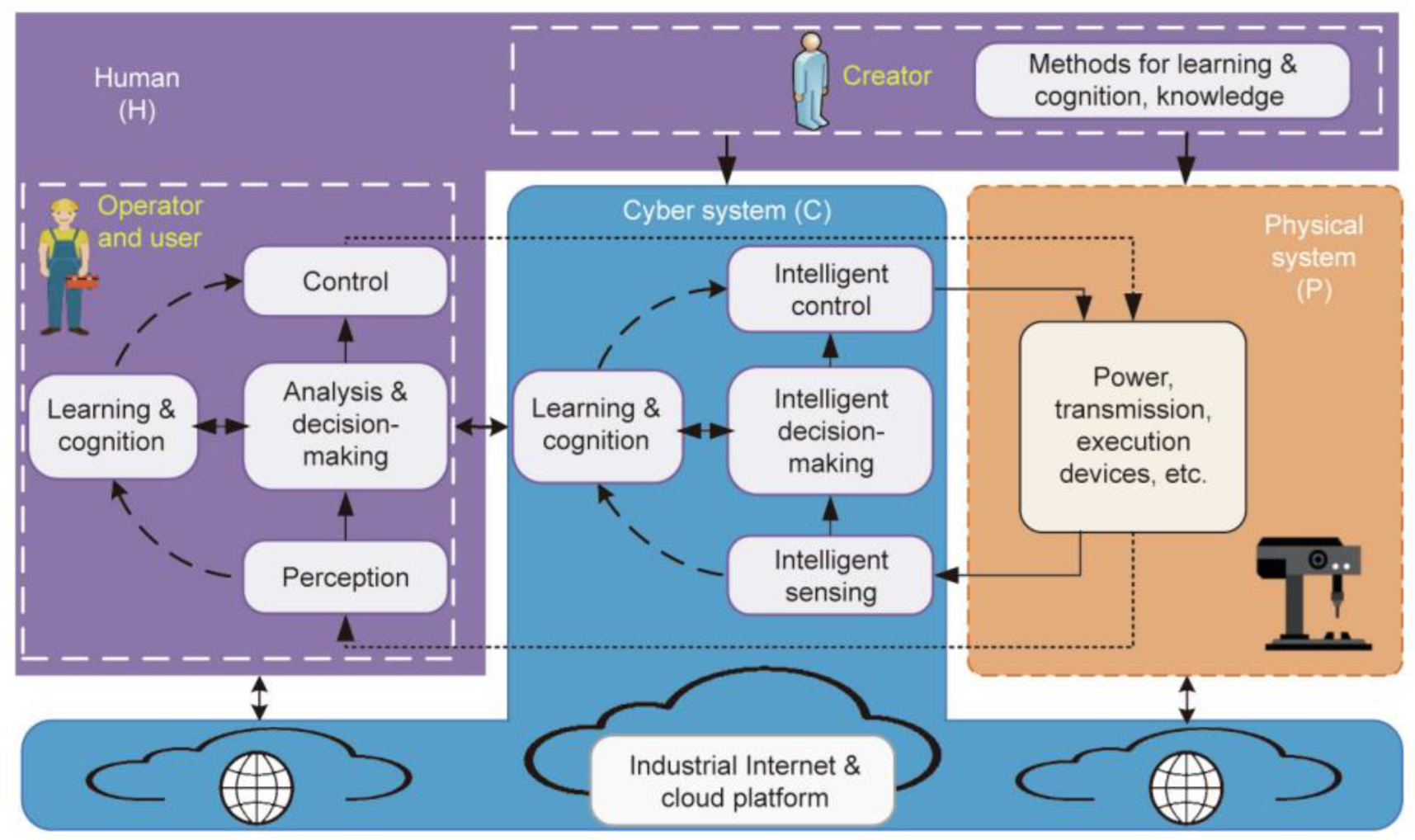

- Zhou, J.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, B.; Zang, J. Human–cyber–physical systems (HCPSs) in the context of new-generation intelligent manufacturing. Engineering, 2019, 5(4), 624-636.

- Ozkan-Ozen, Y. D.; Kazancoglu, Y.; Mangla, S. K. Synchronized barriers for circular supply chains in industry 3.5/industry 4.0 transition for sustainable resource management, Resour. Conserv. Recycl., 2020, 161, 104986.

- Jimenez, E.; Luna, G.; Lucero, B.; Ochoa, F.J.; Muñoz, F.; Delfin, J.J.; Cuenca, F. General guidance for the realization of smart retrofitting in legacy systems for Industry 4.0. In Proceedings of the 3rd IFSA Winter Conference on Automation, Robotics & Communications for Industry 4.0/5.0 (ARCI’ 2023), Chamonix-Mont-Blanc, France, 22–24 February, 2023; pp. 132–137.

- Adamenko, D. Synthesis of the Holistic Smart Retrofit Process of Machines and Plants. In: Ivanov, V., Silva, F.J.G., Trojanowska, J., Pinto, A.M.G. (eds) Advances in Design, Simulation and Manufacturing VIII. DSMIE 2025. Lecture Notes in Mechanical Engineering. Springer, Cham. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Pietrangeli, I.; Mazzuto, G.; Ciarapica, F.E.; Bevilacqua, M. Smart Retrofit: An Innovative and Sustainable Solution. Machines, 2023, 11, 523. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).