1. Introduction

Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (ACDF) is a commonly performed spine procedure that can be performed for traumatic, neoplastic, infectious, and most commonly degenerative spinal pathologies [

1]. A cervical vertebrectomy and interbody fusion (CVIF) is a less commonly performed spine surgery involving resection of an entire vertebrae to facilitate decompression of neurological structures [

2]. Although there are many described methods to achieve stability in an ACDF and CVIF, an anterior plate fixation construct provides immediate stability to the cervical spine while the anterior vertebral column undergoes fusion via the use of bone or synthetic graft [

3]. Use of a plate and screw construct also facilitates preservation of cervical lordosis, which is associated with a positive long-term outcome [

4]. ACDF and CVIP with an anterior plate are relatively successful surgeries when done for a single segment and have a fusion rate of 97.1% and 92.9% respectively [

5].

The risk of complications and need for potential reoperation with ACDF and CVIF increases when surgery is performed on multiple levels. The most common complication is pseudarthrosis secondary to inadequate biomechanical instability which can be up to 24% for surgery at two-levels, 42% at three-levels, and 56% at four-levels for ACDF [

6]. Rates of reoperation for symptomatic non-union are 11.1% for ACDF and 11-28% for CVIF [

6,

7]. The addition of posterior fixation can augment the stability of the construct and decrease rates of hardware failure, but it is also more invasive resulting in higher operative morbidity [

8]. Another way to reduce anterior hardware failure is to decrease the risk of screw pull out through the use of longer screws [

9]. Biomechanical studies have shown that bicortical purchase results in the greatest pull-out strength, but this needs to be balanced with the risk of neural compromise because of penetration of the posterior vertebral cortex [

10].

Despite the theorized biomechanical advantage of increased screw length and added posterior fixation, there are no biomechanical studies that investigate these relationships. This study aims to investigate the impact of increasing screw length and adding posterior fixation on biomechanical stability of anterior cervical fixation constructs modelled for single-level discectomy or corpectomy in worst-case conditions. This study incorporated test methods described in ASTM F1717 using a modified setup with the intent of creating a physiological model to predicate clinical outcomes of the cervical constructs tested [

11].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bone Model

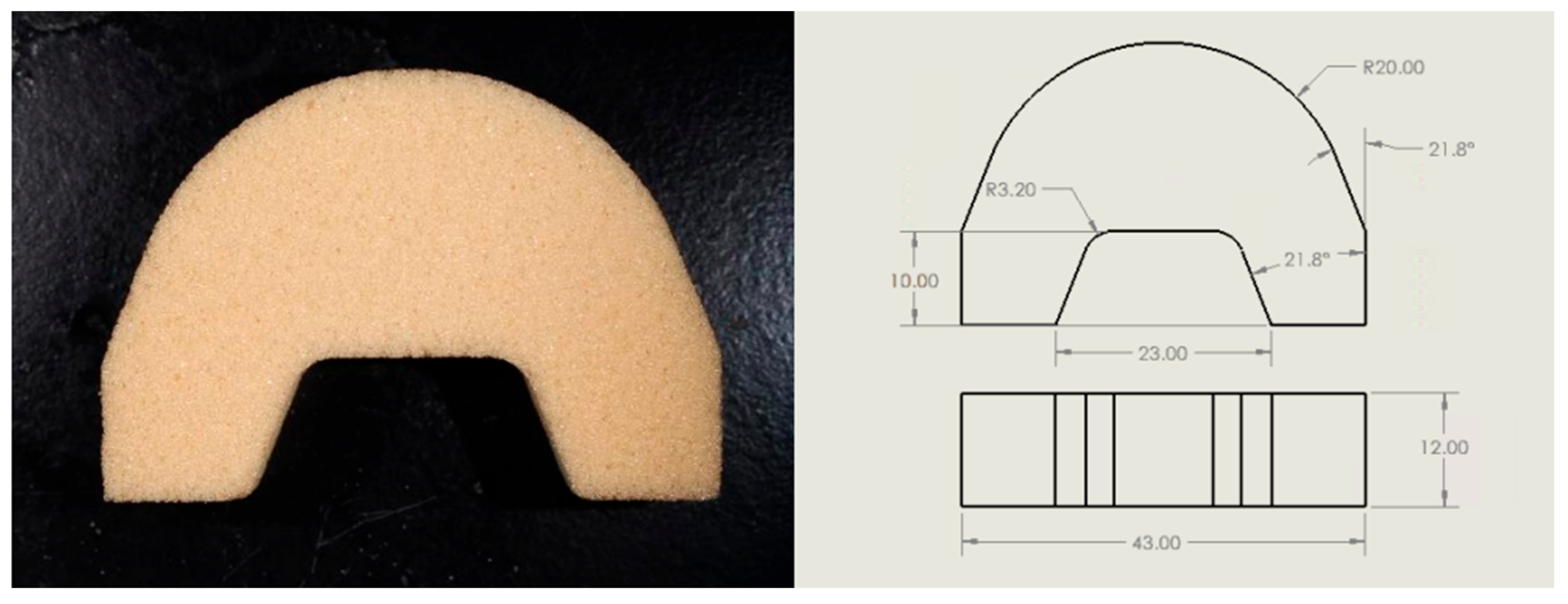

The material selected for the test blocks was Grade 10 polyurethane (PU) foam. PU foams are reproducible analogs for standard test materials in testing orthopedic devices and instruments as outlined in the American Standard of Testing Material (ASTM) F1839 [

12]. The key deviation in our test method from the ASTM F1717 protocol is the use of an osteopenic bone model, rather than the Ultra-High-Molecular-Weight-Polyethylene (UHMWPE) test blocks with a recommended tensile breaking strength of 40 ± 3 MPa that are protocolized. PU solid foam test blocks were selected to represent a more physiological model for testing and comparing construct performance. Grade 10 PU foam is meant to represent mildly osteopenic bone with a density of 0.16 g/cm

3 and a modulus of elasticity of 58 MPa.

Another modification made to the ASTM F1717 protocol is that the test blocks were designed to have a curved anterior face that matched the geometry of the plates and to represent vertebral anatomy more accurately. Specifically, a cervical model with an overall size of 43 x 30 x 12 mm. Exact dimensions are shown in

Figure 1. Each test used a new set of blocks of the same design.

2.2. Test Samples

All hardware used in this study was commercially available. The cervical anterior fixation devices tested were the Cervical Spine Locking Plate (CSLP) Set. We used short (length 22 mm) and long (length 34 mm) anterior plates. We used 14mm and 16mm length locking screws with these plates.

The posterior fixation device tested was the Symphony Occipito-Cervico-Thoracic (OCT) System Set by DePuy Synthes, which included two rods, four pedicle screws, and four set-screws.

2.3. Test Apparatus

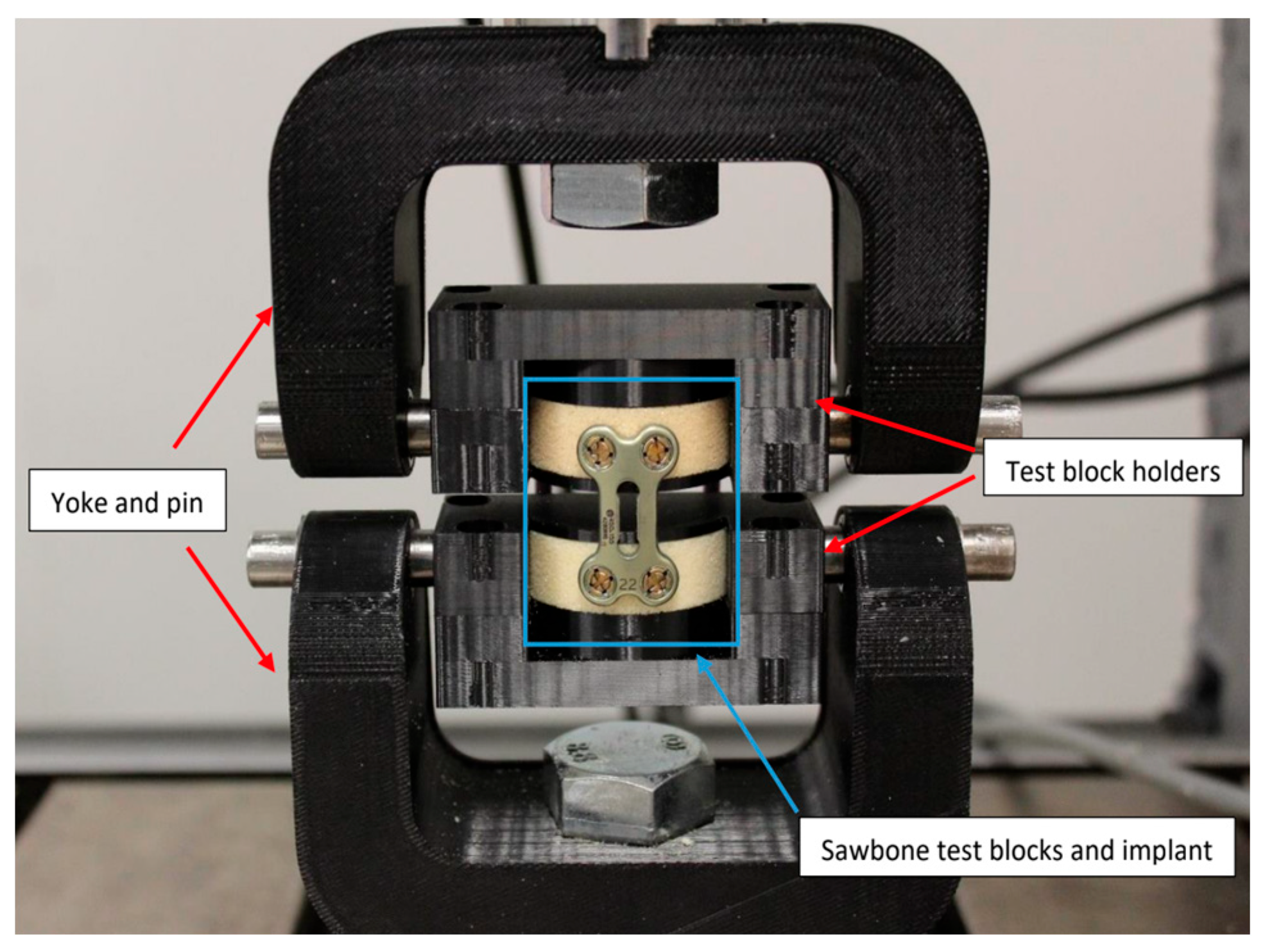

Static and dynamic axial compression tests were conducted on a calibrated load frame, verified to standard ASTM E4 [

13]. The test fixtures were modified from ASTM F1717 to accommodate holding the custom PU test blocks and the anatomical positioning of the cervical constructs tested (

Figure 2). The fixtures were 3D printed from ABS instead of manufactured by stainless steel to accommodate the complexity of the customized setup.

2.4. Construct Assembly

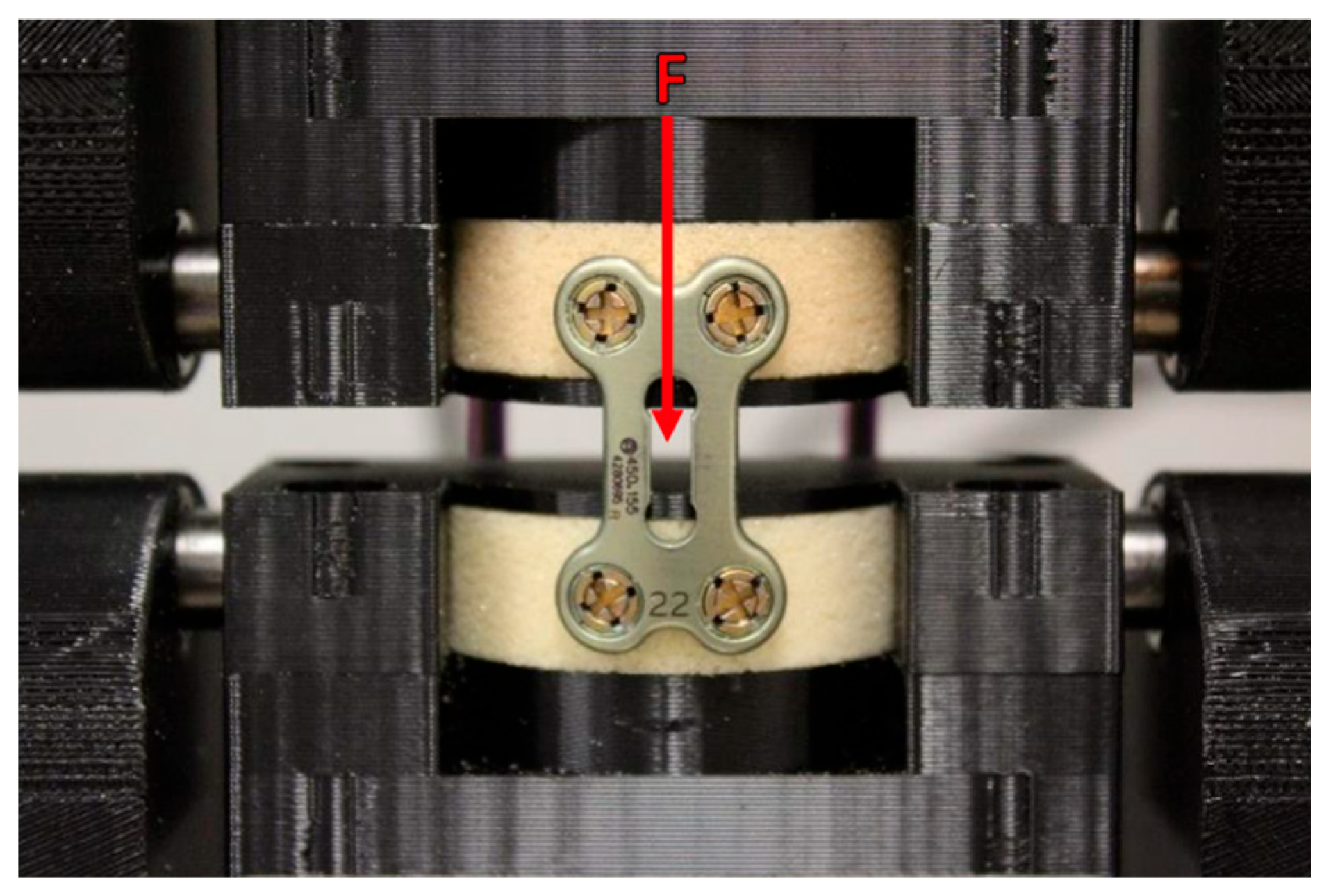

Two of the custom PU test blocks were inserted into the fixtures for each test construct. For all test constructs, an anterior plate was used to attached to the upper and lower test blocks via four uniform length anterior cervical screws (

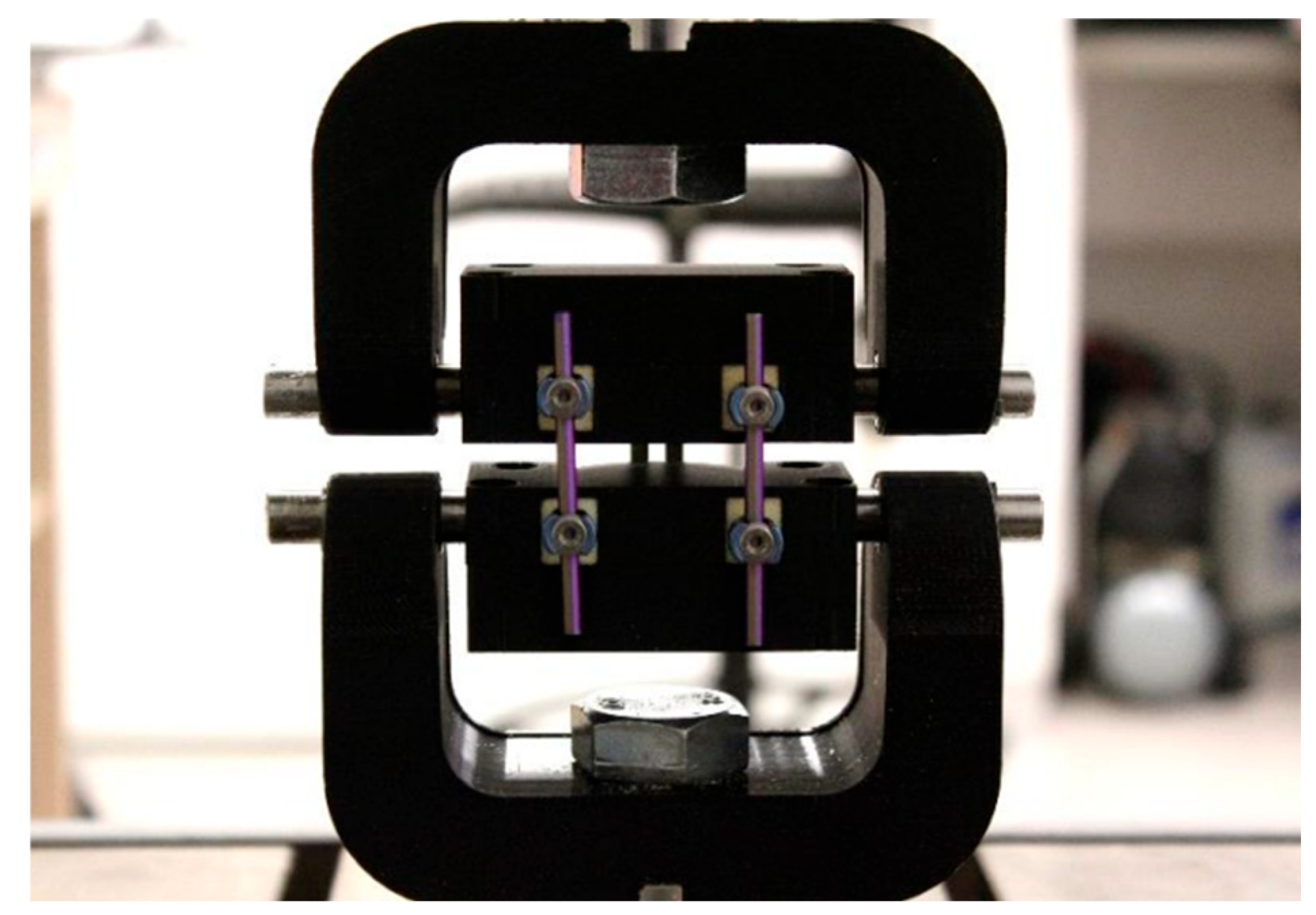

Figure 3). Pilot holes were made in the test blocks prior to insertion to guide accurate screw and plate placement where they were centred in the middle of the test blocks. Constructs with posterior fixation had an additional four tulip screws inserted into the posterior side of the same test blocks where metal spinal rods were installed and secured with four set screws (

Figure 4). Constructs that included a short (22mm) plate were intended to simulate the biomechanics of a discectomy and constructs that included a long (34mm) plate were intended to simulate the biomechanics of a vertebrectomy. Overall, we had the following four types of constructs assembled: 22mm plate + 14mm screws (Construct-1), 22mm plate + 16mm screws (Construct-2), 34mm plate + 14mm screws (Construct-3), and 22mm plate + 14mm screws + posterior rods (Construct-4). The addition of posterior fixation in junction with anterior fixation is not recommended by ASTM F1717, however, for our study we were interested in investigating the effect of combined anterior and posterior fixation to evaluate construct performance. Interbody support was purposely omitted from both discectomy and vertebrectomy models to simulate worst-case scenarios for our modelled constructs.

2.5. Static Testing

Static axial compression tests were conducted at a constant displacement rate of 10 mm/min until a stop condition was reached. Stop conditions included mechanical failure of any test sample component (screw, plate), test block failure (cracking, fracture), screw loosening, and fixture impingement. Only one test sample replicate was performed per test construct.

Load (N), displacement (mm), and time (s) data was collected. Load versus displacement data was plotted to calculate for the 2% yield load and displacement. The yield load was calculated as the load required to produce a permanent deformation equal to 2% of the active length of the longitudinal element (plate and rods). Stiffness was determined by the slope of the initial linear portion of the load-displacement curve.

Test constructs were visually observed for evidence of mechanical failures such as fracture, breakage, cracking, and permanent deformation during testing. Functional failures were observed as inability to maintain applied loading, with or without mechanical failure. Failure location sites were also reported.

2.6. Fatigue Testing

The same four cervical spine fixation constructs tested in static testing were evaluated in fatigue. Fatigue tests were carried out through cyclic tensile loading at 2Hz following a sinusoidal load pattern with a load ratio of R=10. The maximum fatigue loads for each test construct were guided by the yield load results measured in the static testing portion of this study of their respective test construct design. Run-out was reduced from 5 million (as recommended in ASTM F1717), to 1.2 million cycles to help identify potential weaknesses in the early post-operative period (<6 months). One test sample replicate was performed for each construct type.

Stop conditions were either a 1.2 million cycle run-out completion, or failure (< 1.2 million cycles). Failures were defined as functional or mechanical, following the same criteria as defined from static testing. If a test sample completed run-out, the fatigue load was increased by 20 or 30N and re-ran with the cycle counted reset back to zero. This format of fatigue loading was continued until a failure occurred before reaching run-out of 1.2 million cycles. The aim was to evaluate mode of failure and determine the maximum fatigue load for each construct.

Load (N), displacement (mm), time (s), and cycle count data were collected. Tests were monitored daily to check for sample failure.

3. Results

3.1. Static Testing

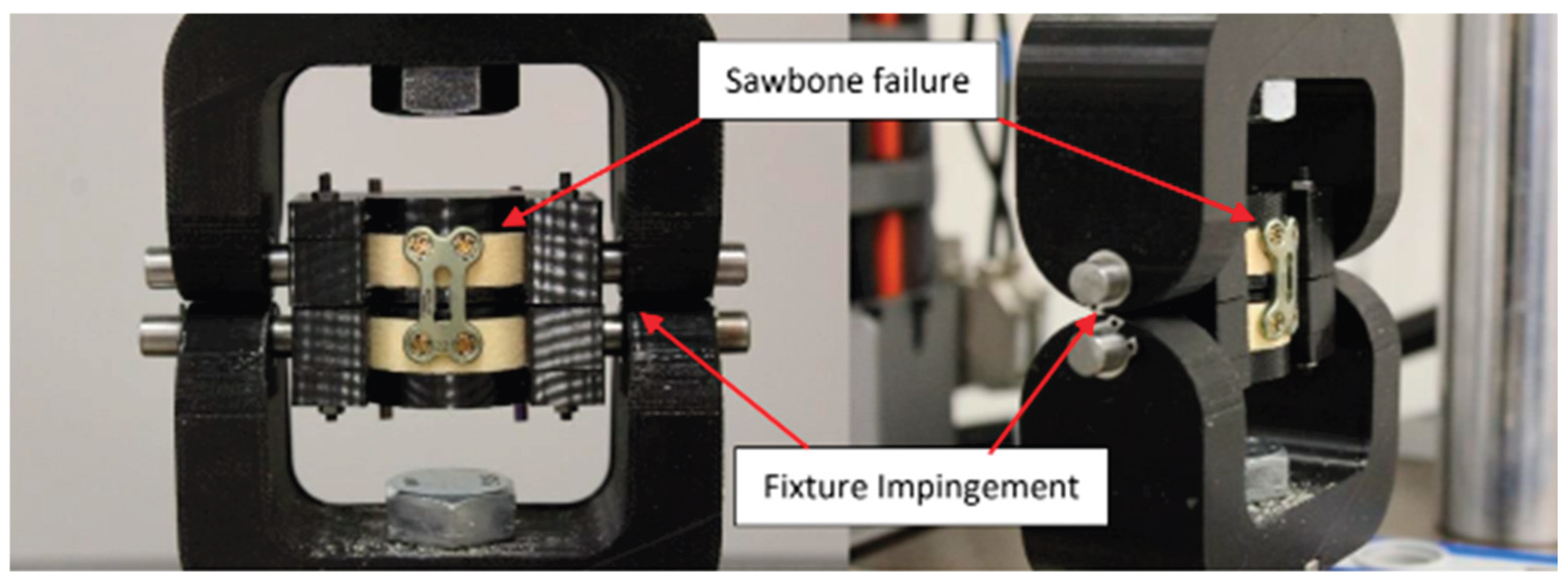

The 2% yield load, yield displacement, maximum displacement at end of test, and construct stiffness of the four different cervical fixation construct types are summarized in

Table 1. All tests were stopped due to test block failure or fixture impingement (

Figure 5).

3.2. Fatigue Testing

The construct that was able to complete 1.2 million cycles at the highest fatigue load was Construct-4, tested at 180N in compression. With loading increased to 200N for Construct-4, it reached failure at 718,011 cycles as a result of permanent deformation. Indicating that the addition of posterior fixation significantly improves the performance and fatigue life of the construct, when tested in a biomechanical model. Fatigue results are outlined in

Table 2. Construct-1 failed due to fixture impingement, while the three other construct types failed due to deformation.

4. Discussion

Fatigue testing revealed that the combination of a 22mm plate and 14mm screws failed with a maximum fatigue load of 50N. Use of longer 16mm screws failed with a maximum fatigue load of 80N. Addition of posterior fixation to anterior 22mm plate and 14mm screws failed with a maximum fatigue load of 180. Therefore, a 2mm increase in screw length resulted in a 1.6 times greater maximum fatigue load leading to construct failure but addition of posterior fixation resulted in 3.6 times greater maximum fatigue load leading to failure. Fatigue testing revealed that the use of a longer plate resulted in slight decrease in maximum fatigue load.

Our data suggests that posterior fixation in addition to anterior fixation is more effective in increasing construct stability than increasing screw length alone. Despite the increased morbidity of a dual (anterior and posterior) approach, this may be the construct of choice for patients undergoing ACDF or CVIF with risk factors that predispose them to hardware failure and resultant deformity such as smoking, metabolic syndrome, diabetes, obesity, younger age, chronic steroid use, or malnutrition [

7]. The increased stability of this construct can allow for the appropriate biomechanical environment to minimize the rate of reoperation. Our data also suggests that increasing screw length may be the simplest way of improving construct stability in both ACDF and VCIF without necessarily exposing patients to an increased morbidity conferred with a dual approach.

These are all general trends that were to be expected based on existing knowledge regarding implant and spine biomechanics, but this is the first time that the magnitudes of the impact of screw length and addition of posterior fixation have been determined in the context of fatigue testing. Two prior retrospective chart reviews have determined that screw length less than 75% of the vertebral body diameter can result in increased interspinous motion and increased risk of hardware failure [

9,

14]. These studies are helpful in identifying how screw length can radiographically impact fusion rates in cervical spine surgery but may not be as useful intraoperatively. Based on patient characteristics, a surgeon can use the information from our study to gauge if the biomechanical advantage of increasing screw length by 2mm is worth the risk intraoperatively. There has been a single finite element modelling (FEM) biomechanical study investigating the effect of screw length in ACDF, but it investigated neck range of motion which is not an outcome of interest [

15]. Two other FEM studies have investigated the effect of anterior-only, posterior-only, and combined fixation on annular/nucleus stress, instrument stress, and facet forces when a pure moment was applied [

16,

17]. These studies investigate how a single static force may lead to implant failure, rather than the fatigue failure that we are interested in.

The ASTM F1717 standard recommends conducting fatigue tests up to 5 million cycles to evaluate the endurance of spinal implant constructs under repeated loading conditions to simulate several years of typical daily activities. However, such a long duration is not required in cases of ACDF or CVIF as we would only require segment stability to allow for a critical period required to achieve fusion. We purposely used a run-out cycle of 1.2 million cycles as this aligns with the estimated number of cycles a construct would experience before achieving fusion. Another deviation from the ASTM F1717 standard included modification of the test fixtures to more securely hold the tested constructs. This was done to increase the reliability of our testing apparatus in applying axial loading forces without introduction of translational or rotational forces.

We purposefully used PU bone models rather than cadaveric bone to ensure reproducibility of our results and to limit the error that is introduced with non-uniform bone density that can be present within and between cadaveric bone. The ASTM F1839 standard specification was designed specifically for rigid polyurethane foam as a reliable and repeatable material for testing orthopaedic devices and instruments mechanically. Testing in ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene (UHMWPE) would not consider the quality of fixation of the implant to the vertebral bone. We modified the protocol by using an osteoporotic bone model which is more clinically relevant as the patients we are often operating on have diminished bone density. In our opinion, the use of osteoporotic bone models has helped us gain more clinically relevant results based on our study objectives.

Ultimately, this study is a biomechanical study using a synthetic bone model rather than a randomized control trial in cadavers or humans. The use of a synthetic bone model allows for consistency in our study, rather than the variability of bone density and anatomy that is present in cadaveric studies. However, our study model does not account for the soft tissue structures present around the neck that inherently interact dynamically with the hardware. Secondarily, our synthetic bone model does not include simulation of cortex. This is a controversial topic in biomechanical studies, but it should be noted that this is the standard of preliminary testing of spinal implants as per the ASTM. Furthermore, it is safer to perform these tests in laboratory conditions rather than in humans.

Even though we are intentionally testing our constructs under worst-case conditions, lack of vertebral interbody graft in our cervical models can be considered another limitation of this study. We are interpreting our study results in the context of ACDF and CVIF, but those surgeries have some type of vertebral interbody graft to obtain fusion. The vertebral interbody graft inherently confers some stability to the construct if it remains in the appropriate position during the fusion process, and it is likely the addition of such a graft to our study would have altered the maximum fatigue load outcomes, but it is difficult to know how much of a difference this would have made to the relative constructs that we used [

18].

We draw reasonable conclusions on general trends within our data to make suggestions for ACDF and VCIF, however we did not specifically obtain data using a combination of 34mm plate and 16mm screws, nor did we augment the vertebrectomy model with posterior fixation. We can expect that increased screw lengths and addition of posterior fixation would increase maximum fatigue loads in the VCIF models. These were not completed due to depletion of funds.

As with any study supported by external funding, there is potential for bias related to financial sponsorship. While one of the grants was provided by an industry source and another by an academic institution, all funding was applied solely to study-related activities. Measures were taken to ensure objectivity in study design, data analysis, and interpretation. No sponsor had any role in the data collection, statistical analysis, or manuscript preparation.

5. Conclusions

Our findings suggest that while increasing screw length improves stability, posterior fixation offers the most significant biomechanical benefit by improving fatigue capacity, thereby could reduce the risk of hardware failure and kyphotic deformity. This is particularly true of the corpectomy model where hardware failure and subsequent kypotic deformity are a significant concern. This study is the first to quantify the impact of screw length and posterior fixation on construct stability through fatigue testing, providing valuable insights for surgical planning in ACDF and CVIF procedures. Furthermore, by modifying standard test methods for spinal fixation systems (ASTM F1717) to incorporate analog bone models and a fusion rate specific run-out, we have tested within a clinically relevant scenario for evaluating anterior cervical fusion constructs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.G. and M.G.; methodology, M.A., S.G. and M.G.; software, S.G.; formal analysis, S.G., T.G. and J.S.; resources, T.G. and M.G.; data curation, S.G.; writing—original draft preparation, J.S.; writing—review and editing, S.G., T.G. and M.G.; supervision, M.G.; project administration, S.G.; funding acquisition, T.G. and M.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

There was no specific singular source of funding for this project. The Orthopaedic Innovation Centre (OIC) has previously received research support (investigator salary, staff, materials) from Smith & Nephew, DePuy Synthes, Zimmer Biomet, Stryker, and Hip Innovation Technology. The OIC has also previously received grants from Arthritis Society Canada, University of Manitoba, Research Manitoba, and the American Association of Hip and Knee Surgeons. Funding from these sources is used to support many ongoing projects at the OIC.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data may be available on request from the Orthopaedic Innovation Centre (OIC), Winnipeg, MB, Canada.

Acknowledgments

The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ACDF |

Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion |

| CVIF |

Cervical vertebrectomy and interbody fusion |

| ASTM |

American Standard of Testing Material |

| PU |

Polyurethane |

| UHMWPE |

Ultra-high-molecular-weight polyethylene |

| CSLP |

Cervical spine locking plate |

| OCT |

Occipito-cervico-thoracic |

| FEM |

Finite element modelling |

References

- Sugawara, T. Anterior cervical spine surgery for degenerative disease: a review. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2015, 55(7), 540–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foreman, M; Foster, D; Gillam, W; Ciesla, C; Lamprecht, C; Lucke-Wold, B. Management considerations for cervical corpectomy: updated indications and future directions. Life (Basel) 2024, 14(6), 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, LH; D’Souza, M; Ho, AL; Pendharkar, AV; Sussman, ES; Rezaii, P; Desai, A. Anterior techniques in managing cervical disc disease. Cureus 2018, 10(8), e3146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, C; Qin, R; Wang, P; Wang, P. Comparison of anterior and posterior approaches for treatment of traumatic cervical dislocation combined with spinal cord injury: minimum 10-year follow-up. Sci Rep. 2020, 10(1), 10346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraser, J.F.; Härtl, R. Anterior approaches to fusion of the cervical spine: a metaanalysis of fusion rates. J Neurosurg Spine, 2007; pp. 298–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, NE. A review of complication rates for anterior cervical diskectomy and fusion (ACDF). Surg Neurol Int. 2019, 10, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leven, D; Cho, SK. Pseudarthrosis of the cervical spine: risk factors, diagnosis and management. Asian Spine J 2016, 10(4), 776–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sethy, SS; Goyal, N; Ahuja, K; Ifthekar, S; Mittal, S; Yadav, G; Venkata Sudhakar, P; Sarkar, B; Kandwal, P. Conundrum in surgical management of three-column injuries in sub-axial cervical spine: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Spine J 2022, 31(2), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, NJ; Vulapalli, M; Park, P; Kim, JS; Boddapati, V; Mathew, J; Amorosa, LF; Sardar, ZM; Lehman, RA; Riew, KD. Does screw length for primary two-level ACDF influence pseudarthrosis risk? Spine J 2020, 20(11), 1752–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, HG; Kang, MS; Kim, KH; Park, JY; Kim, KS; Kuh, SU. A surgical method for determining proper screw length in ACDF. Korean J Spine 2014, 11(3), 117–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

ASTM F1717-15; Standard test methods for spinal implant constructs in a vertebrectomy model. ASTM International, 2015.

-

ASTM F1839:2012; Standard specification for rigid polyurethane foam for use as a standard material for testing orthopaedic devices and instruments. ASTM International, 2012.

-

ASTM E4-24; Standard Practices for Force Calibration and Verification of Testing Machines. ASTM International, 2024.

- Chanbour, H; Bendfeldt, GA; Johnson, GW; Peterson, K; Ahluwalia, R; Younus, I; Longo, M; Abtahi, AM; Stephens, BF; Zuckerman, SL. Longer screws decrease the risk of radiographic pseudarthrosis following elective anterior cervical discectomy and fusion. Global Spine J 2023, 13(11), 21925682231214361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baisden, J; Yoganandan, N. The effect of screw length on single-level anterior cervical fusion using finite element. Spine J 2022, 22(9), S17–S18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishida, N; Tripathi, S; Mumtaz, M; Kelkar, A; Kumaran, Y; Sakai, T; Goel, VK. The effect of anterior-only, posterior-only, and combined anterior posterior fixation for cervical spine injury with soft tissue injury: a finite element analysis. World Neurosurg. 2023, 171, e777–e786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, C; Wang, Z; Liu, P; Liu, Y; Wang, Z; Xie, N. A biomechanical analysis of anterior cervical discectomy and fusion alone or combined cervical fixations in treating compression-extension injury with unilateral facet joint fracture: a finite element study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2021, 22(1), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stein, MI; Nayak, AN; Gaskins, RB, 3rd; Cabezas, AF; Santoni, BG; Castellvi, AE. Biomechanics of an integrated interbody device versus ACDF anterior locking plate in a single-level cervical spine fusion construct. Spine J 2014, 14(1), 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |