1. Introduction

A wide range of cervical spine disorders can be managed with various surgical treatments. These disorders include degenerative and neoplastic pathologies affecting the three columns of the spine, which can lead to micro or macro instability, resulting in compression of the nerve roots or spinal cord. In cases of spinal cord injury accompanied by progressive neurological deficits, early decompression surgery performed within 24 hours of symptom onset has been associated with improved neurological outcomes.[1] However, the optimal timing of surgical intervention for cervical spondylotic myelopathy remains more controversial. While some studies[2] have reported better short-term relieve of neck pain following surgery compared to conservative management, the long-term benefits have not been consistently demonstrated.[3] As a result, surgical intervention is typically recommended only for patients presenting with moderate to severe signs of myelopathy or progressive neurological deficits[4].

Several surgical techniques have been described for the decompression of the cervical spine, including both anterior and posterior approaches, with or without fusion. Among the well-established anterior techniques are the anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (ACDF) and the anterior cervical corpectomy and fusion (ACCF).[5-8] The use of an anterior plate can provide additional stability, aiming to enhance fusion rates and prevent pseudoarthrosis.[9] Alternative posterior approaches include laminoplasty, laminotomy, and laminectomy, which may be combined with fusion of the affected segments. However, surgical procedures involving screw placement carry an inherent risk of misplacement, potentially leading to neurological or vascular injuries and necessitating revision surgery.

Since 2010, our institution has used a hybrid operating room equipped with intraoperative computed tomography (iCT) to confirm the correct placement of screws and minimize the need for revision surgery. In a previous study, we reported the high sensitivity and specificity of iCT in identifying incorrect pedicle screw placement during lumbar spinal instrumentation[10].

While ACCF and ACDF have remained the standard techniques for decompression and fusion of the cervical spine at our institution, the posterior approach has recently gained more frequent use in the management of degenerative and neoplastic pathologies, as well as cervical spine injuries. The current study aims to evaluate the accuracy of iCT in posterior cervical spine fusion and to report the associated clinical and radiological outcomes.

2. Materials and Methods

The study included patients who underwent posterior cervical fusion in our hybrid operating room between March 2012 and April 2016. Lateral mass screws were used for levels C3 to C6, while transpedicular screws were preferred for C7 and the thoracic spine. One patient underwent an isolated C1-C2 fusion using the Harms/Goel technique, and another patient received a fusion from the occiput to C5 combined with an atlantoaxial fusion as described by Magerl.

The following patient characteristics were recorded: Age at time of surgery, patient history, neurological status, previous cervical spine surgeries including the approach, adverse events, and revision surgeries during the follow-up period. Postoperative immobilization of the cervical spine was achieved using either a stiff cervical collar or a halo vest.

Physicians from our department conducted neurological examinations at the initial presentation, discharge, and last follow-up. The clinical assessment included level of neck pain and radicular pain using the Visual Analog Scale (VAS[11]), as well as assessing sensorimotor deficits, gait disturbance, and deep tendon reflexes. For patients who were still alive, an additional long-term follow-up assessment was performed in the outpatient clinic. In these patients, we additionally collected Neck Disability Index (NDI)[12], Nurick Scale[13], modified Macnab Criteria[14] and Odom’s Criteria[15].

Routine imaging, including anterior-posterior, lateral, and flexion-extension x-rays, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), was performed before and after surgery. The first authors and an independent radiologist analyzed these images. The radiological endpoints included fusion rate using the Lenke and Bridwell fusion classification[16], the number of misplaced screws, and any loosening or fractures of the screws. Additionally, changes in alignment and signs of myelopathy were assessed.

All surgeries were conducted in our hybrid operating room equipped with a Philips AlluraXper FD20 angiography suite, which is a cone beam CT with a rotating C-arm. We routinely used this system to perform intraoperative CT scans. If a significant screw misplacement was detected on the CT, immediate replacement was attempted until the correct position was confirmed in the final iCT. As a standard practice at our institution, patients underwent a postoperative CT scan with thin slice reconstructions of 0.5 mm in the axial plane and 3 mm in the sagittal/coronal planes to rule out any relevant screw misplacement. This is done due to safety considerations and quality control, as the postoperative CT scan provides better imaging quality compared to the iCT. The postoperative CT scans were then used to validate the iCT findings and to calculate specificity, sensitivity, and accuracy.

The intraoperative CT scan software does not allow to measure distances in millimeters with precise accuracy. As a result, we defined four categories to classify screw placement. A screw was considered to have correct positioning if it was entirely surrounded by the substance of the pedicle or lateral mass. If a screw extended beyond the cortical bone of the pedicle or lateral mass but did not protrude more than one-third of its diameter, it was recorded as a minor violation. Screws that bulged from the bony borders by more than one-third of their diameter but did not exceed the full diameter were classified as moderate violations. Any screw protrusion exceeding the full diameter was labeled as a severe violation.

Statistical Analysis

We present the results using percentages, means with standard deviations (SD), and medians for various parameters, including patient characteristics, extent of spinal fusion, symptoms at discharge, follow-up and long-term outcomes, radiological findings, complications, and adverse events. Additionally, we evaluated the sensitivity (percentage of detected condition), specificity (percentage of detected absence of condition), and accuracy (percentage of overall correct assignment) of the iCT scan in assessing screw placement, using the postoperative CT scan as the reference.

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

Between March 2012 and April 2016, a total of 19 patients, consisting of 12 males (63%) and 7 females (37%), underwent posterior cervical fusion at our institution. The mean age at the time of surgery was 59 (± 11) years.

Among these patients, 7 (37%) had a neoplastic mass in the vertebral column, while 6 patients (32%) had degenerative changes as the indication for surgery. The remaining 6 patients (32%) had suffered a traumatic cervical spine injury with fracture. Despite the wide variation in the indications for cervical posterior fusion within our series, the different entities demonstrated similar results. In most cases, neck pain was the primary indication for surgery.

Table 1.

3.2. Extent of Surgical Spinal Fusion

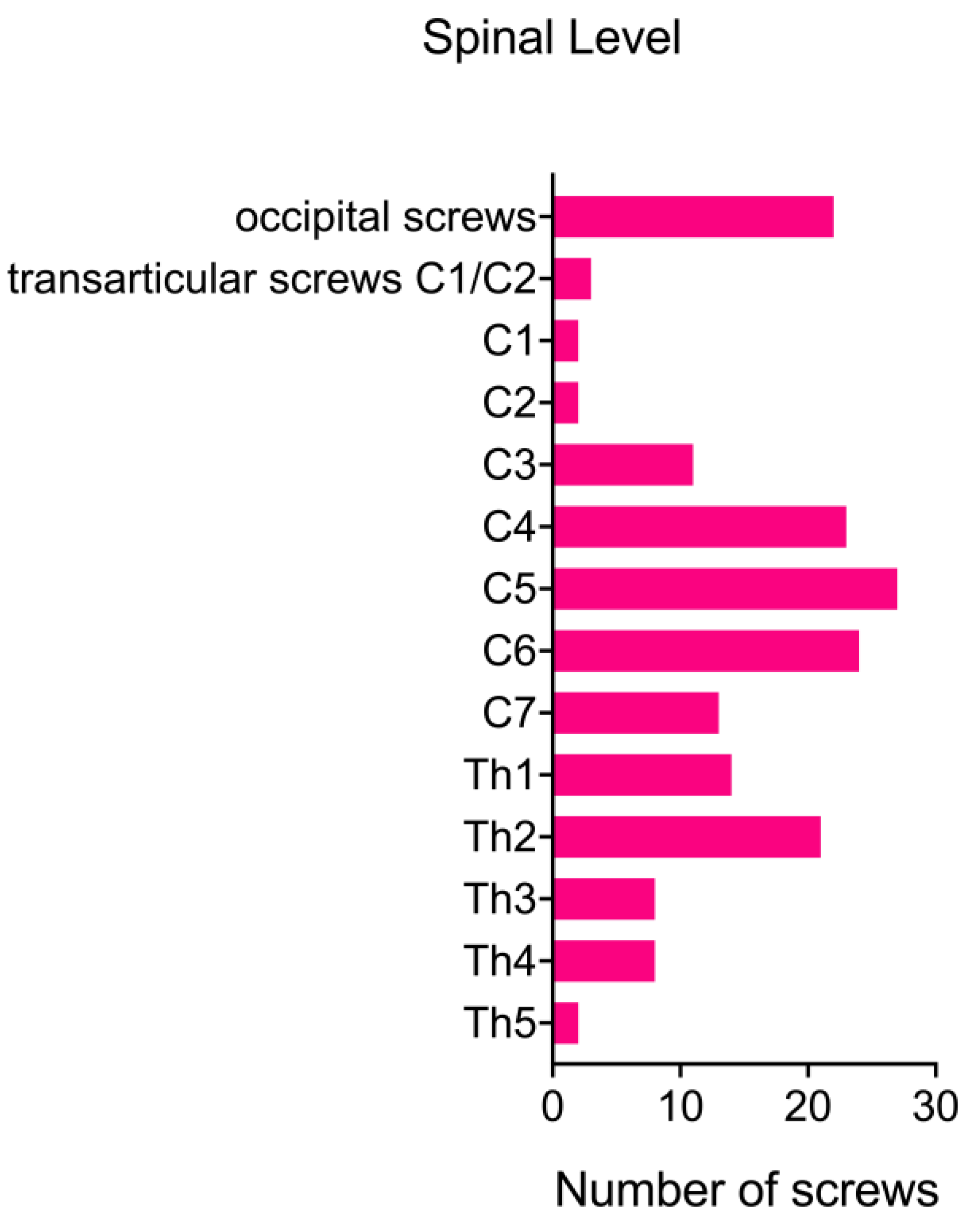

Prior to the posterior cervical fusion, 12 patients (63%) had already undergone an anterior approach for cervical fusion. For 7 patients (37%), posterior spinal fusion was the primary treatment option. The cervical fusion procedures involved a range of 1 to 9 segments, with a mean of 4.74 segments. In 6 cases (32%), the fusion was confined to the cervical spine. However, in 5 additional posterior fusions (26%), it was necessary to include the occipito-cervical junction. Furthermore, in 11 cases (58%), the fusion extended to the upper thoracic spine. One patient (5%) developed kyphosis following a chordoma resection via an anterior approach (ACCF) and required a fusion spanning 9 segments from the occipito-cervical junction to Th2.

Figure 1.

Table 2.

Following the surgery, patients were immobilized with a stiff cervical collar until the first follow-up, which occurred 4 to 6 weeks postoperatively. In three cases involving fusion to the upper thoracic spine, a corset was prescribed. One patient (5%) who underwent fusion from the occipito-cervical junction to C6 required a halo vest for immobilization.

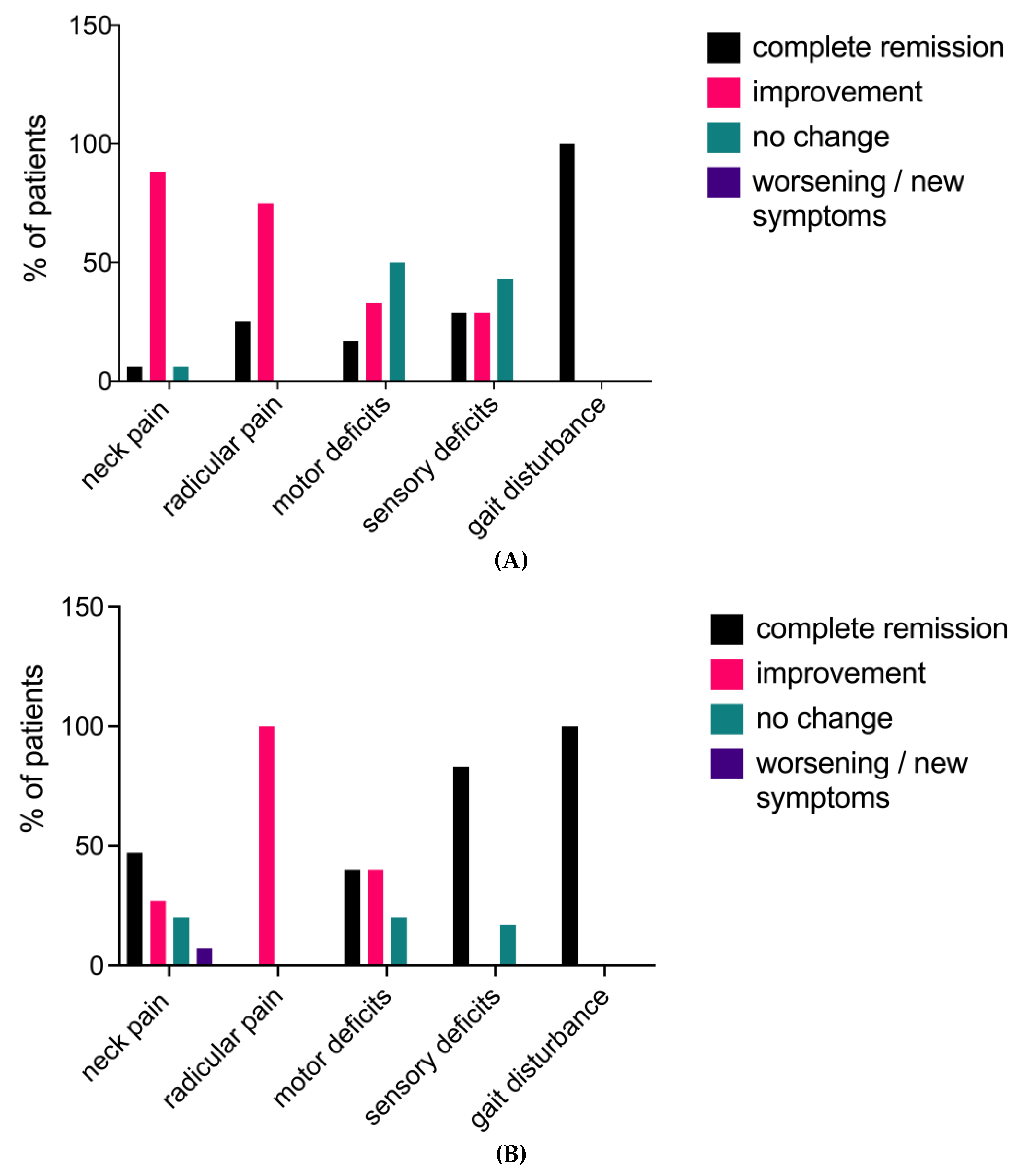

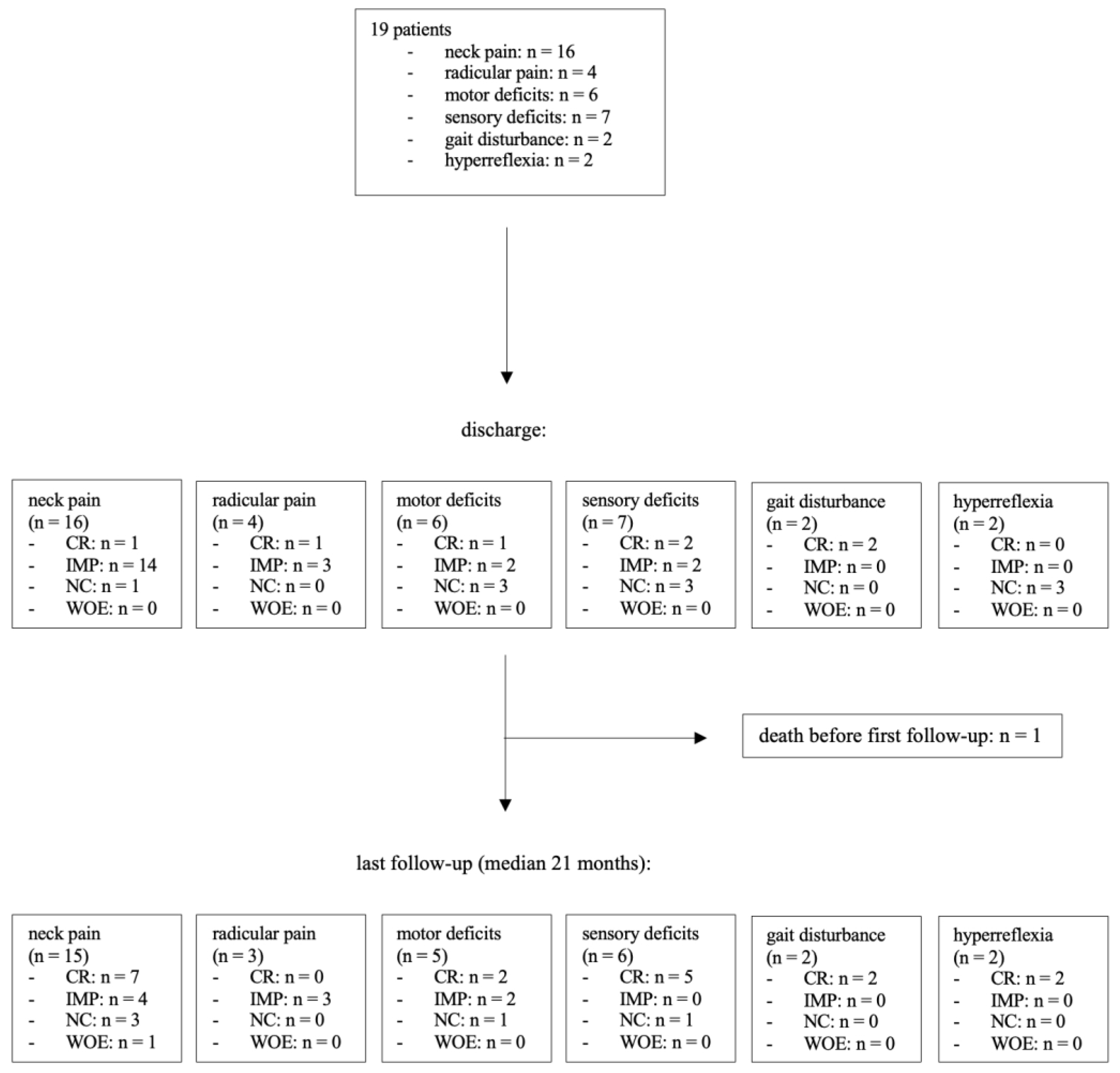

3.3. Symptoms at Discharge

At the time of initial presentation, 16 patients (84%) reported neck pain, while 4 patients (21%) experienced radicular pain. Upon clinical examination, sensory deficits were found in 7 patients (37%), and paresis was present in 6 cases (32%). Gait disturbance and hyperreflexia were each observed in 2 patients (11%). At discharge, 15 patients (94%) in the neck pain group demonstrated improvement in their pain levels, with one patient becoming completely pain-free. One patient (6%) showed no change compared to their preoperative pain level. No new postoperative neck pain was reported at discharge. All patients with radicular pain experienced improvement, with one patient in this group becoming pain-free after surgery. Motor deficits improved in 3 out of 6 patients (50%), with one patient having no residual paresis at discharge. Muscle strength remained stable in the other 3 cases (50%). Sensory disturbances improved in 4 out of 7 patients (57%), with 2 patients (29%) recovering normal sensibility and 3 patients (43%) remaining unchanged. Regarding myelopathy symptoms, both patients (100%) in the gait disturbance group had no residual symptoms at discharge. As anticipated, hyperreflexia did not normalize during the brief period until discharge.

3.4. Follow-Up and Clinical Long-Term Outcome

Among the 19 patients in this study, 15 had a clinical follow-up of at least 12 months, with a median follow-up duration of 21 months after surgery. One patient died 22 days after the surgery, and no follow-up data could be recorded after discharge. At the last follow-up, 11 out of 15 patients (73%) who had complained of pain before surgery reported an improvement in their overall pain level, including both radicular and neck pain. Three patients (20%) reported no changes, and one patient (7%) experienced an increase in neck pain compared to their preoperative state. Neurological examination revealed that 15 patients (83%) had no sensorimotor deficits. An increase in muscular strength was recorded in 4 out of 5 patients (80%), with 2 patients (33%) achieving normal strength. One patient (20%) remained stable. Among the 6 patients in the sensory deficit group, only 1 patient (17%) had a residual sensory deficit with unchanged symptoms. Neither of the 2 patients with preoperative gait impairment showed residual gait disturbance at the last follow-up.

Figure 2A and B.

Figure 3.

Seven patients (37%) were prospectively followed in our outpatient clinic. Their Neck Disability Index Score (NDI) ranged from zero to 24 points. However, 6 patients (86%) showed only mild or no disability (NDI < 15). The corresponding median for NDI was 4. The Nurick Scale was assessed in 2 patients with myelopathy symptoms and gait disturbance. The median Nurick Scale score was 0. According to the modified Macnab criteria, a good or excellent outcome was achieved in 5 patients (71%). In terms of Odom’s criteria, 5 patients (71%) reported a good or excellent outcome. There was no poor outcome in our current series.

3.5. Radiological Findings

Long-term radiological follow-up was not routinely conducted, with a median radiological follow-up of 12 months. Thirteen out of 19 patients (68%) underwent a CT scan of the fused segments at least 12 months after the surgery. In this group, the fusion rate was evaluated using the Lenke and Bridwell classification system. A solid fusion across the entire fused area was observed in 9 patients (69%). Among these, 5 cases (38%) achieved trabeculated bilateral fusion (Lenke and Bridwell Grade A), while 4 cases (31%) had unilateral fusion (Grade B). Small, non-solid fusion masses (Grade C) were observed in 3 patients (23%). One patient (8%) had a non-union in one or more of the fused segments (Grade D).

Table 3.

During the radiological follow-up, screw loosening was observed in 5 patients (38%), involving a total of 17 screws. However, due to the absence of symptoms, no revision surgery for screw replacement was necessary.

3.6. Complications and Adverse Events

Four patients (21%) required revision surgery due to surgical site infection (n=3) or cerebrospinal fluid leak (n=1). One patient underwent additional surgery using an anterior approach after experiencing a screw fracture and impaction of a previously placed intervertebral cage. In two patients with persistent neck pain, the hardware was removed.

Since the PCF surgery, four patients (21%) died. The indication for surgery in these cases was neoplastic lesions in 3 patients and degenerative disease in 1 patient. There was one case (5%) of perioperative mortality within 30 days of surgery. The patient had prostate cancer with osseous metastases and initially underwent an anterior vertebrectomy of C6 and C7 with anterior plate placement, followed by a posterior fusion from C5 to Th4 10 days later. Although the initial postoperative course was uneventful, with the patient being discharged to rehabilitation 7 days after surgery, the patient died in the rehabilitation facility 15 days later. The exact cause of death remains unknown.

3.7. Sensitivity, Specificity and Accuracy of iCT

In our series, iCT was used in all cases. For upper posterior cervical spine approaches, including C6, lateral mass screws were used, while pedicle screws were the preferred technique for fusion below C6. A total of 151 lateral mass and pedicle screws were evaluated using iCT. Based on the iCT findings, 8 screws (5.3%) were repositioned intraoperatively. Correct screw placement was confirmed with a final iCT scan at the end of the surgery. Additionally, all patients underwent a postoperative CT scan, which confirmed the correct placement of 110 screws (72.8%). A minor violation was found in 24 screws (15.9%), a moderate violation in 13 screws (8.6%), and a severe violation in 4 screws (2.6%). No additional surgeries were necessary to reposition the screws.

The sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of the iCT scans were calculated using the postoperative CT scan as a reference. For correct screw placement, the sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy were 92.7%, 82.9%, and 90.0%, respectively. For minor violations, the values were 70.8%, 91.3%, and 88.1%, respectively. For moderate violations, the sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy were 69.2%, 98.6%, and 96.0%, respectively. For severe screw violations, the sensitivity was 75%, specificity was 100%, and accuracy was 99.3%.

Table 4 and table 5.

Radiation exposure was documented in 100% of the cases. The mean cumulative air kerma for the intraoperative CT was 43.51 (± 42.93) mGy, compared to 66.6 mGy for the postoperative CT scans of the cervical spine. The mean corresponding cumulative dose area product (DAP) was 15.51 (± 15.72) Gy cm2 in the iCT and 13.15 Gy cm2 in the regular postoperative scan.

4. Discussion

4.1. Clinical Outcome

Our study demonstrated good short- and long-term outcomes, regardless of previous surgical interventions on the cervical spine or the underlying condition. At the 2-year follow-up, 79% of patients reported overall pain improvement, and functional recovery was achieved in up to 88% of cases. These findings are consistent with a systematic review and meta-analysis by Youssef et al.[17], which included data from 1,238 patients who underwent posterior spinal fusion. They reported similar favorable outcomes, with significant improvements in pain levels and overall function, as assessed by the JOA and mJOA scores. Similarly, Anderson et al.[18] conducted a systematic review of 11 studies and described comparable results, with functional improvement in 70% to 95% of patients and a significant improvement in JAO scores.

In our series, 15 out of 19 patients had a follow-up of at least 12 months. Among all patients, statistically significant improvements were observed in all evaluated categories, including pain, sensorimotor deficits, and gait disturbance. The 15 patients with longer follow-up showed a trend towards progressively better results over time. Although there was no statistical significance between the two groups due to the small sample size, we would expect the 4 patients who were not followed for at least 12 months to continue improving rather than deteriorating.

The use of iCT in this study allowed for the immediate identification and direct replacement of 8 misplaced screws, resulting in improved screw placement accuracy and potentially avoiding the need for subsequent revision surgeries. Based on these findings, it is reasonable to hypothesize that the implementation of iCT technology could lead to better clinical outcomes for patients undergoing spinal instrumentation procedures. However, to thoroughly evaluate the impact of iCT on patient outcomes and to establish its superiority over alternative techniques, such as navigated screw placement, further controlled and prospective studies are necessary.

4.2. Surgical Approach

Various surgical approaches to the cervical spine, with or without fusion of the segment, have been described in the literature. Anterior cervical approaches include anterior cervical discectomy with cage only or with an additional plate, as well as corpectomy with fusion. For posterior approaches, laminotomy, laminoplasty, and laminectomy with or without fusion are the most common techniques. In cases of symptomatic cervical disc herniations, anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (ACDF) is a well-established and routine procedure. However, this approach is associated with typical complications such as injury to the recurrent laryngeal nerve and dysphagia.[19] In spondylotic cervical myelopathy (CSM), spondylotic changes and deformities lead to compression of the spinal cord. The most favorable approach for treating CSM remains controversial.[20]

A retrospective study conducted at our institution found that posterior decompression without fusion was an effective treatment option for CSM, significantly relieving symptoms in patients without signs of cervical spinal instability prior to surgery.[21] In contrast, other authors have recommended avoiding stand-alone laminectomy due to the inherent risk of delayed postoperative kyphosis.[22] For patients with pre-existing neck pain, kyphosis, and signs of instability, posterior fusion should generally be the preferred approach.[23]

Asher, et al.[24] published a multicenter analysis comparing anterior and posterior approaches. They found that patients undergoing posterior fusion were more likely to receive a fusion involving more than three levels compared to the anterior fusion group. While the length of hospital stay was significantly longer in the posterior group, long-term reported outcomes and complication rates were similar between the two approaches.[24]

A prospective study[25] involving a total of 264 patients compared anterior discectomy and fusion with posterior decompression (laminoplasty or laminectomy with fusion). In this series, the anterior approach showed favorable results. However, patients receiving posterior decompression were more likely to suffer from multi-level pathologies and were generally older. After adjusting for these confounding factors, similar results were reported for both anterior and posterior approaches.[25]

In trauma patients, the choice of surgical approach depends on additional factors such as the presence and volume of herniated discs, the presence of bone fragments, concomitant spondylotic changes narrowing the spinal canal, the presence of uni- or bilateral facet dislocation, and the patient's neurological status. Finally, it is important to note that posterior fusion of the cervical spine is a more demanding technique, and the surgeon's training level and experience play a crucial role.

In our current series, 63% of patients were initially treated using an anterior approach. Posterior fusion was the first choice for patients with preoperative instability or malalignment of the cervical spine caused by fractures or tumor growth. Posterior fusion following anterior fusion was performed if symptoms persisted, mainly in cases of malalignment and instability.

4.3. Adverse Events & Revision Rate

Other studies have reported complication rates of 11%26, and 11.6%.[23,26] We attribute the higher perioperative complication rate in our series to the small number of patients included. All patients who underwent revision surgery showed a good outcome with complication-free wound healing. More significant surgical complications, especially those resulting in new persistent neurological deficits or long-term disability, did not occur. Notably, due to the use of iCT, no additional surgery was required at a later stage to correct the alignment of misplaced screws.

4.4. Radiological Outcomes & Fusion Rates

At the final radiological follow-up, 92% of patients showed signs of partial or complete fusion (Lenke and Bridwell grade A to C). This finding is consistent with the fusion rates reported in previous studies, which typically ranged from 89% to 100%.[27,28] Only one patient showed a non-union at their last follow-up, which was 7.33 years after posterior fusion.

4.5. Intraoperative CT Scan

In comparison to the postoperative CT scan, iCT showed a good sensitivity and specificity. All four screws with severe violation were registered on the iCT scan. Of the 13 screws showing a moderate violation, only one misplaced screw was missed on iCT. A previous study by Nevzati E., et al.[10] conducted at our institution, evaluated the accuracy of intraoperative CT scans for pedicle screws in the lumbar and caudal thoracic spine. They reported sensitivity and specificity rates for moderate and severe violations exceeding 86%, which slightly surpasses the sensitivity of our results. We attribute this difference to the smaller diameter of cervical lateral mass and pedicle screws, where differences in resolution between iCT and regular CT scans become more important for detecting screw misplacement.

Some authors argue that lateral mass screw placement does not require intraoperative radiographic control, as they are less likely to be misplaced when using anatomical landmarks.[29] This is consistent with the results in our series, where only one out of the 8 intraoperatively corrected screws was a lateral mass screw at the C4 level, while the other 7 were transpedicular screws. We routinely performed an iCT scan, as it offers the possibility to further reduce the risk of screw misplacement with a reasonably moderate increase in radiation exposure and only a minor extension of the operation time.

Given the high sensitivity (92.7%), specificity (82.9%), and accuracy (90.0%) reported in this study, it can be argued that a routine postoperative CT scan may be unnecessary, as it offers no significant additional benefits compared to iCT.

It is important to note that the use of an iCT scan is just one method to decrease the number of screw misplacements. Several studies have demonstrated the advantages of using intraoperative navigation.[30-33] Navigated screw placement is used in many centers and has recently also been established at our institution. The availability of navigation might mitigate the need for an iCT in the future, as it offers a useful tool to ensure the correct placement of screws with a reduced level of ionizing radiation compared to iCT.

The measured mean values for cumulative air kerma and dose area product are slightly lower than the values measured in the postoperative CT scans. However, it is important to note that these measurements are difficult to compare. The iCT scans are performed in a flat panel angiography suite with a rotating C-arm, while the postoperative CT scans use a multidetector computed tomography system. As a result, the actual radiation doses affecting the patient are not accurately represented by the measured values. A study by Jones and Odisio[34] used a phantom to compare the radiation doses when using the two different systems. They found that the mean central axis dose in the multidetector CT system was 41–69% lower compared to the flat panel CT scan. However, the measured noise was much higher in the multidetector CT systems. When noise magnitudes were matched, similar radiation doses were expected between the two systems.

4.6. Study Limitations

This retrospective study had several limitations. First, the cohort size was relatively small, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. Second, due to the retrospective nature of the study, clinical scores such as VAS, NDI, Nurick Scale, and modified Macnab Criteria were not available for all patients, which could have provided a more comprehensive assessment of patient outcomes. Third, among the 13 patients with long-term radiological follow-up, 3 exhibited fusion masses with apparent cracks, suggesting that these may not represent solid fusions. Finally, CT scans were typically performed on symptomatic patients suspected of non-union, which could have led to a biased detection of lower fusion rates.

5. Conclusions

The findings of this study suggest that posterior cervical fusion performed in a hybrid OR setting is a safe and effective treatment option for various cervical spinal pathologies. Most patients (88%) achieved good or excellent long-term clinical outcomes, with 84% reporting pain improvement and a fusion rate of 94%. The high sensitivity and specificity of iCT for detecting relevant screw malposition prevented the need for any revision surgery for screw replacement in this complex and surgically demanding area of the spine. These results highlight the potential benefits of using advanced intraoperative imaging technologies in the surgical management of cervical spine disorders.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.C.K. and J.F.; methodology, J.C.K. and A.D.; data collection, A.D. and J.C.K; formal analysis, A.D. and J.C.K; writing—original draft preparation, A.D. and J.C.K.; writing—review and editing, A.K., A.D., J.C.K. and J.F.; supervision, J.C.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study was approved by the local ethics committee northwestern and central Switzerland. (EKNZ Nr.2018-00521). All patients or their family provided written voluntary informed consent prior to the study enrollment.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. All patients or their family provided written voluntary informed consent prior to the study enrollment.

Data Availability Statement

The authors will share the data upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Fehlings MG, Vaccaro A, Wilson JR, et al. Early versus delayed decompression for traumatic cervical spinal cord injury: results of the Surgical Timing in Acute Spinal Cord Injury Study (STASCIS). PLoS One. 2012;7(2):e32037. [CrossRef]

- Persson LC, Carlsson CA, Carlsson JY. Long-lasting cervical radicular pain managed with surgery, physiotherapy, or a cervical collar. A prospective, randomized study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). Apr 1 1997;22(7):751-8. [CrossRef]

- Nikolaidis I, Fouyas IP, Sandercock PA, Statham PF. Surgery for cervical radiculopathy or myelopathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. Jan 20 2010;(1):CD001466. [CrossRef]

- Fehlings MG, Tetreault LA, Riew KD, et al. A Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Patients With Degenerative Cervical Myelopathy: Recommendations for Patients With Mild, Moderate, and Severe Disease and Nonmyelopathic Patients With Evidence of Cord Compression. Global Spine J. Sep 2017;7(3 Suppl):70S-83S. [CrossRef]

- Mummaneni PV, Kaiser MG, Matz PG, et al. Cervical surgical techniques for the treatment of cervical spondylotic myelopathy. J Neurosurg Spine. Aug 2009;11(2):130-41. [CrossRef]

- Emery SE, Bohlman HH, Bolesta MJ, Jones PK. Anterior cervical decompression and arthrodesis for the treatment of cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Two to seventeen-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am. Jul 1998;80(7):941-51. [CrossRef]

- Hilibrand AS, Fye MA, Emery SE, Palumbo MA, Bohlman HH. Impact of smoking on the outcome of anterior cervical arthrodesis with interbody or strut-grafting. J Bone Joint Surg Am. May 2001;83-A(5):668-73.

- Koller H, Reynolds J, Zenner J, et al. Mid- to long-term outcome of instrumented anterior cervical fusion for subaxial injuries. Eur Spine J. May 2009;18(5):630-53. [CrossRef]

- Kawakami M, Tamaki T, Iwasaki H, Yoshida M, Ando M, Yamada H. A comparative study of surgical approaches for cervical compressive myelopathy. Clin Orthop Relat Res. Dec 2000;(381):129-36. [CrossRef]

- Nevzati E, Fandino J, Schatlo B, et al. Validation and accuracy of intraoperative CT scan using the Philips AlluraXper FD20 angiography suite for assessment of spinal instrumentation. Br J Neurosurg. Dec 2017;31(6):741-746. [CrossRef]

- McCormack HM, Horne DJ, Sheather S. Clinical applications of visual analogue scales: a critical review. Psychol Med. Nov 1988;18(4):1007-19. [CrossRef]

- Vernon H, Mior S. The Neck Disability Index: a study of reliability and validity. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. Sep 1991;14(7):409-15.

- Nurick, S. Nurick S. The pathogenesis of the spinal cord disorder associated with cervical spondylosis. Brain. 1972;95(1):87-100. [CrossRef]

- Macnab I. Negative disc exploration. An analysis of the causes of nerve-root involvement in sixty-eight patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. Jul 1971;53(5):891-903.

- Odom GL, Finney W, Woodhall B. Cervical disk lesions. J Am Med Assoc. Jan 4 1958;166(1):23-8. [CrossRef]

- Lenke LG, Betz RR, Harms J, et al. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: a new classification to determine extent of spinal arthrodesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. Aug 2001;83-A(8):1169-81.

- Youssef JA, Heiner AD, Montgomery JR, et al. Outcomes of posterior cervical fusion and decompression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Spine J. Oct 2019;19(10):1714-1729. [CrossRef]

- Anderson PA, Matz PG, Groff MW, et al. Laminectomy and fusion for the treatment of cervical degenerative myelopathy. J Neurosurg Spine. Aug 2009;11(2):150-6. [CrossRef]

- Lee MJ, Bazaz R, Furey CG, Yoo J. Risk factors for dysphagia after anterior cervical spine surgery: a two-year prospective cohort study. Spine J. Mar-Apr 2007;7(2):141-7. [CrossRef]

- Witwer BP, Trost GR. Cervical spondylosis: ventral or dorsal surgery. Neurosurgery. Jan 2007;60(1 Supp1 1):S130-6. [CrossRef]

- Woernle K, Marbacher S, Khamis A, Landolt H, Fandino J. Clinical Outcome after Laminectomy without Fusion for Cervical Spondylotic Myelopathy. Open Journal of Modern Neurosurgery. 2015;05(02):41-48. [CrossRef]

- Albert TJ, Vacarro A. Postlaminectomy kyphosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). Dec 15 1998;23(24):2738-45. [CrossRef]

- Lau D, Winkler EA, Than KD, Chou D, Mummaneni PV. Laminoplasty versus laminectomy with posterior spinal fusion for multilevel cervical spondylotic myelopathy: influence of cervical alignment on outcomes. J Neurosurg Spine. Nov 2017;27(5):508-517. [CrossRef]

- Asher AL, Devin CJ, Kerezoudis P, et al. Comparison of Outcomes Following Anterior vs Posterior Fusion Surgery for Patients With Degenerative Cervical Myelopathy: An Analysis From Quality Outcomes Database. Neurosurgery. Apr 1 2019;84(4):919-926. [CrossRef]

- Fehlings MG, Barry S, Kopjar B, et al. Anterior versus posterior surgical approaches to treat cervical spondylotic myelopathy: outcomes of the prospective multicenter AOSpine North America CSM study in 264 patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). Dec 15 2013;38(26):2247-52. [CrossRef]

- Audat ZA, Fawareh MD, Radydeh AM, et al. Anterior versus posterior approach to treat cervical spondylotic myelopathy, clinical and radiological results with long period of follow-up. SAGE Open Med. 2018;6:2050312118766199. [CrossRef]

- Muffoletto AJ, Hadjipavlou AG, Jensen RE, Nauta HJ, Necessary JT, Norcross-Nechay K. Techniques and pitfalls of cervical lateral mass plate fixation. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). Nov 2000;29(11):897-903.

- Kumar VG, Rea GL, Mervis LJ, McGregor JM. Cervical spondylotic myelopathy: functional and radiographic long-term outcome after laminectomy and posterior fusion. Neurosurgery. Apr 1999;44(4):771-7; discussion 777-8. [CrossRef]

- Katonis P, Papadakis SA, Galanakos S, et al. Lateral mass screw complications: analysis of 1662 screws. J Spinal Disord Tech. Oct 2011;24(7):415-20. [CrossRef]

- Scarone P, Vincenzo G, Distefano D, et al. Use of the Airo mobile intraoperative CT system versus the O-arm for transpedicular screw fixation in the thoracic and lumbar spine: a retrospective cohort study of 263 patients. J Neurosurg Spine. Oct 2018;29(4):397-406. [CrossRef]

- Farah K, Coudert P, Graillon T, et al. Prospective Comparative Study in Spine Surgery Between O-Arm and Airo Systems: Efficacy and Radiation Exposure. World Neurosurg. Oct 2018;118:e175-e184. [CrossRef]

- Mandelka E, Gierse J, Zimmermann F, Gruetzner PA, Franke J, Vetter SY. Implications of navigation in thoracolumbar pedicle screw placement on screw accuracy and screw diameter/pedicle width ratio. Brain Spine. 2023;3:101780. [CrossRef]

- Ille S, Baumgart L, Obermueller T, Meyer B, Krieg SM. Clinical efficiency of operating room-based sliding gantry CT as compared to mobile cone-beam CT-based navigated pedicle screw placement in 853 patients and 6733 screws. Eur Spine J. Dec 2021;30(12):3720-3730. [CrossRef]

- Jones AK, Odisio BC. Comparison of radiation dose and image quality between flat panel computed tomography and multidetector computed tomography in a hybrid CT-angiography suite. J Appl Clin Med Phys. Feb 2020;21(2):121-127. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).