1. Introduction

Nuclear power plants must be safe, reliable and ensure the planned supply of electricity. Many nuclear units are operated for a period of several decades. The design period of the NPP vessels is estimated at 30-35 years. According to the IAEA, 29 numbers of reactors have been operating for 40 years, and another 160 numbers - for more than 40 years [

1]. These nuclear units are operating beyond the warranty period. The metal of the equipment operates in conditions of high pressure values and fluid temperatures along the primary and secondary circuits, in radiation and in corrosive working environments. These factors cause degradation of the mechanical properties of the metal and a decrease in the bearing capacity of the vessels. In the “worst-case scenario”, it could lead to metal rupture and a nuclear accident, which – undoubtedly – means the loss of human lives and many resources. This is absolutely unacceptable, forbidden, unthinkable! Here is the role of scientists, educators, energy engineers and government regulators – society relies on their knowledge, competencies, professionalism and morals, but this is a separate and very long topic. Therefore, it is important to periodically investigate the mechanical characteristics of the metal of the equipment of a nuclear unit. The mechanisms of degradation of mechanical properties of WWER plants are neutron and thermal aging, fatigue, corrosion and erosion wear, mechanical wear [

2]. RPV metal is subject to the most aggressive environmental impact due to nuclear chain decay processes [3÷6]. The neutrons in the reactor are of high energy (over 1.5 MeV) and low mass; they penetrate the metal crystal lattice of the metals of the internal housing devices and cause point and volumetric defects in the structure. During the processes of nuclear decay, an amount of heat is released. The radiation working environment causes neutron and thermal brittleness of the metal. The metal from the internal surfaces of the equipment is corroded by contact with fluids (general and local corrosion), thermohydraulic loads (stress corrosion) and by radiation environment (intergranular corrosion). Contacting metal surfaces can cause metal wear defects. So, on the one hand of the aging process of equipment, we have many mechanisms of degradation of the mechanical properties of the metal, and on the other side - testing of the metal of the equipment is carried out through “standard” methods of control (testing), there is a periodicity, technological procedures and regulations, etc. It seems that everything is fine with aging and there will be no “worst-case scenario”. My 33 years of practice in the field of technical diagnostics of nuclear power plants shows, however, that the “standard” test methods “cover” the destruction of the metal only in the first 15-20 years of the operation of the nuclear unit. Later in time, the metal ages under the influence of the synergistic action of degradation mechanisms, defects develop, sometimes very quickly, and the methods remain the same as at the beginning of the unit’s operation. In order for the control (testing, monitoring) of the metal to be effective, it must be clarified: 1) Whether the methods applied are sensitive to the effects of aging; 2) Are these characteristics measured (calculated) that will lead to the destruction of the metal. The subject of research in this article is the metal on the inner surface of the reactor vessel, type WWER,

Figure 1. Defects were found on the metal surface.

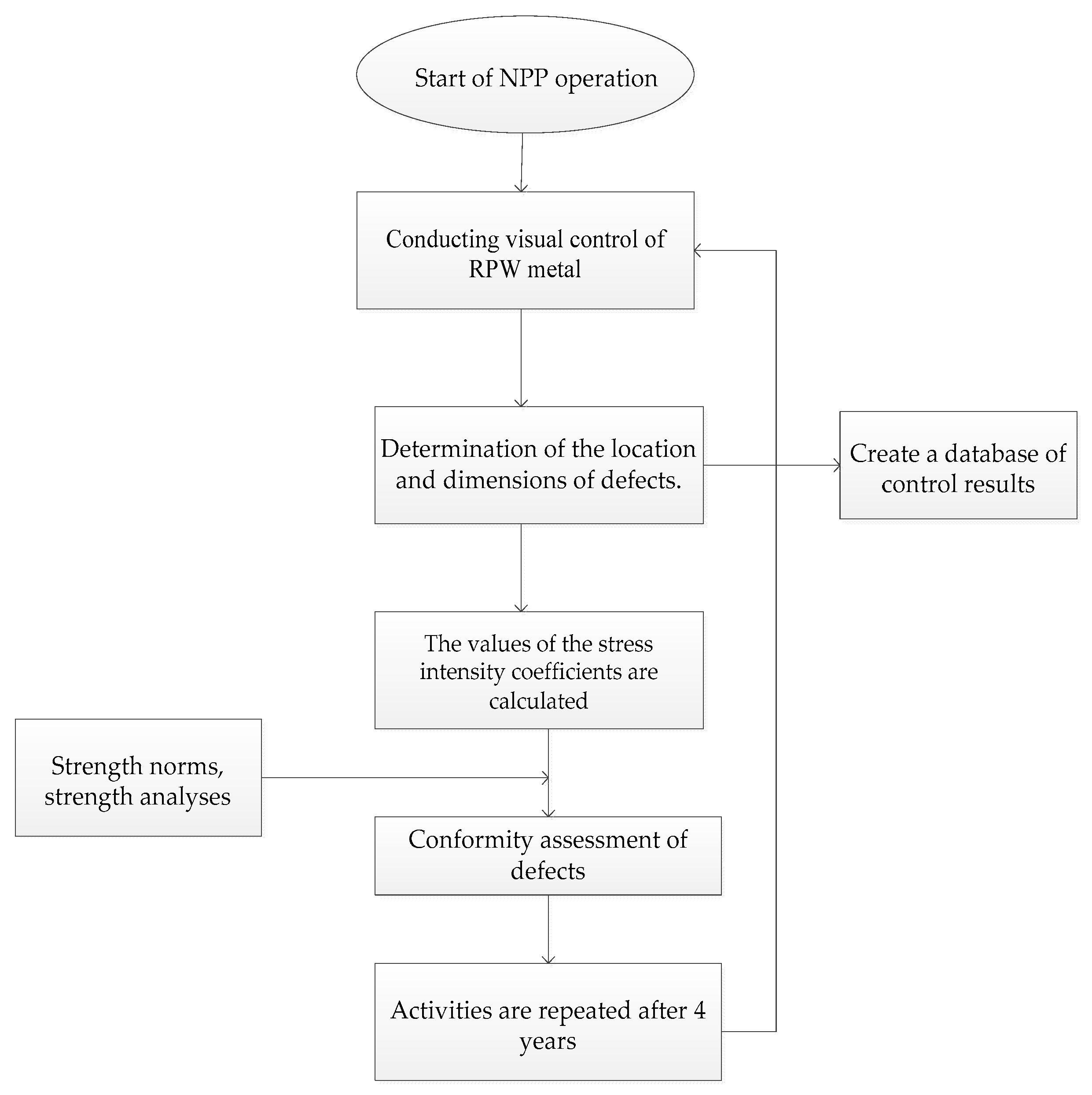

The cause of the defects is mechanical wear, and their growth is under the influence of environmental factors - high pressures and temperatures of fluids, radiation, corrosion and erosion. Violation of the integrity of the RPV surface is an extremely undesirable phenomenon. Safety is a top priority for any nuclear power plant – it is an unconditional requirement. In order for the operation of the nuclear unit to continue, it is required to prepare analyses of the admissibility of defects. The practical study is through a visual inspection method that is regularly applied to the inner surface of the reactor vessel every 4 years. After 15-20 years of operation of the unit, defects in the metal appear and develop, which can be observed, determine their location and measure the parameters of defects. Theoretical research is to calculate the mechanical characteristics of the metal. Since in this case real metals of real nuclear power plants are examined (it is not a laboratory facility), a conservative approach should be applied to the assessments – i.e. to consider the worst case. A priori, it is assumed that there is an embrittlement of metals due to neutron and thermal aging and from the presence of defects. This article discusses the process of evaluating defects in metal by the criterion of brittle fracture resistance; only three mechanisms of base metal degradation are evaluated – neutron and thermal aging and embrittlement due to surface defects.. Тhe main aim of the work is to present an approach (a methodology) for periodically examining defects during the operation of the unit. In principle, nuclear units can operate safely only if the requirements of the strength standards are met. For the specific test case, it is proven that the strength requirements are met and the unit can be operated safely – at least during the next test in 4 years.

2. Materials and Methods

The focus of the current study is based on RPV metal. The reactor materials are austenitic steels and ferrite-pearlite steels with austenitic surfacing coating. Austenitic steels are corrosion-resistant, have appropriate technological properties and operate up to temperatures of 700 °C. Steels of type 08X18H10T are radiation-resistant. Alloyed pearlite chromium-molybdenum-vanadium steel 15X2NMFA has two layers of austenitic overlay. Steels of the type 15X2MFA, 15X2NMFA, A542, A543, A508 have resistance to radiation brittleness, high strength and good ductility, but are not corrosion-resistant [

7]. The reactor vessels have an internal diameter of 3580 mm and a wall thickness of 140 mm. The metal of the reactor vessel is controlled by a visual test method [

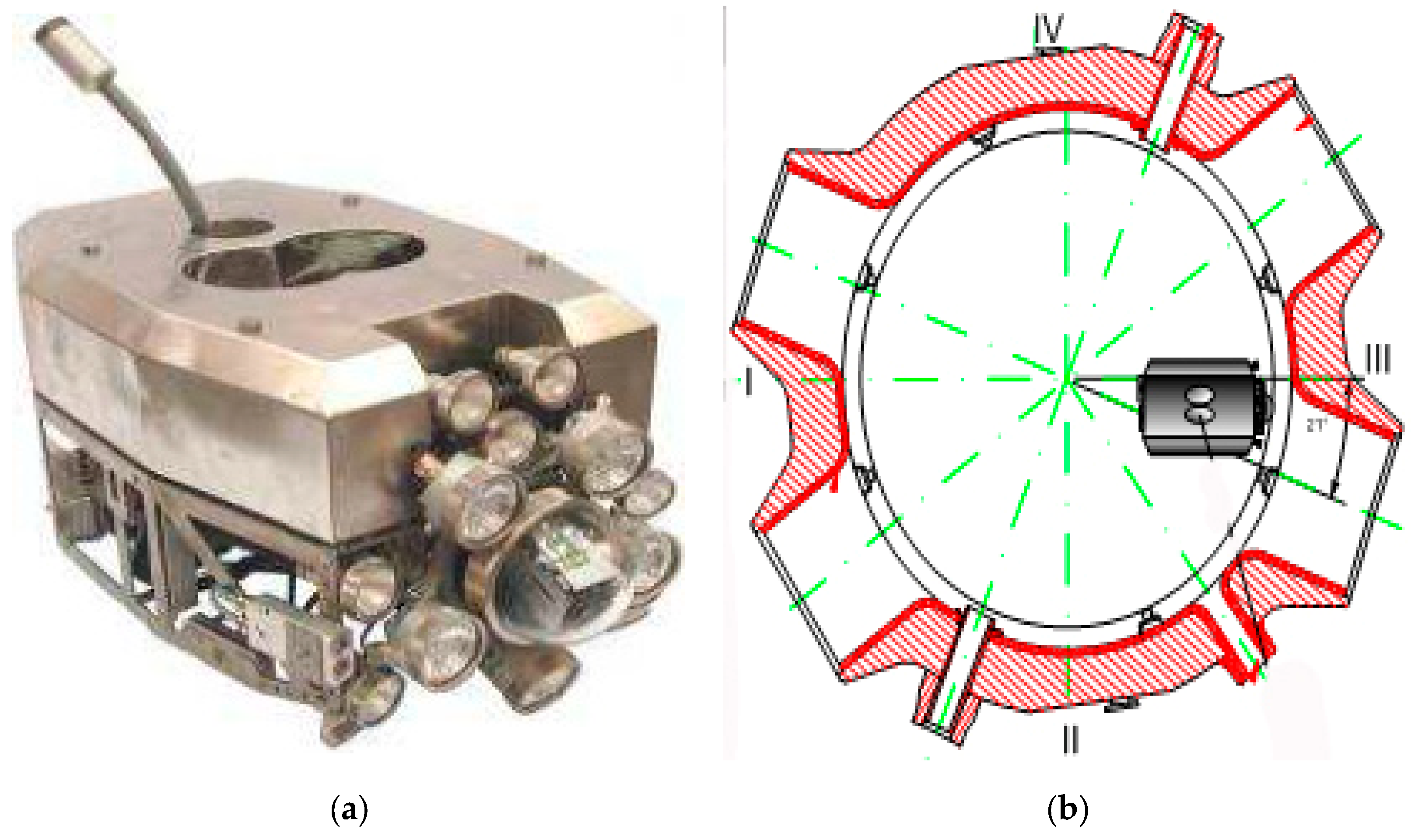

8]; surface defects on the inner surface of the reactor vessel are detected. The monitored parameters are the type, size and location of the defects. In the presence of a group of defects, their mutual location is traced and the distances between the individual single defects are measured. The equipment used is a remote visual control system

Figure 2a, which scans the inner surface of the entire body step by step,

Figure 2b.

The underwater television surveillance system of the hull has specialized software for storing the location of indications, sizing, comparing with previous data, etc. Visual testing of the RPV metal is carried out periodically, according to technological regulations. The period is once every 4 years. The current study covers a period of 26 years. Defects on the inner surface of nuclear reactor casings have been registered. The place of defects is in the area of strengthening the Core barrel,

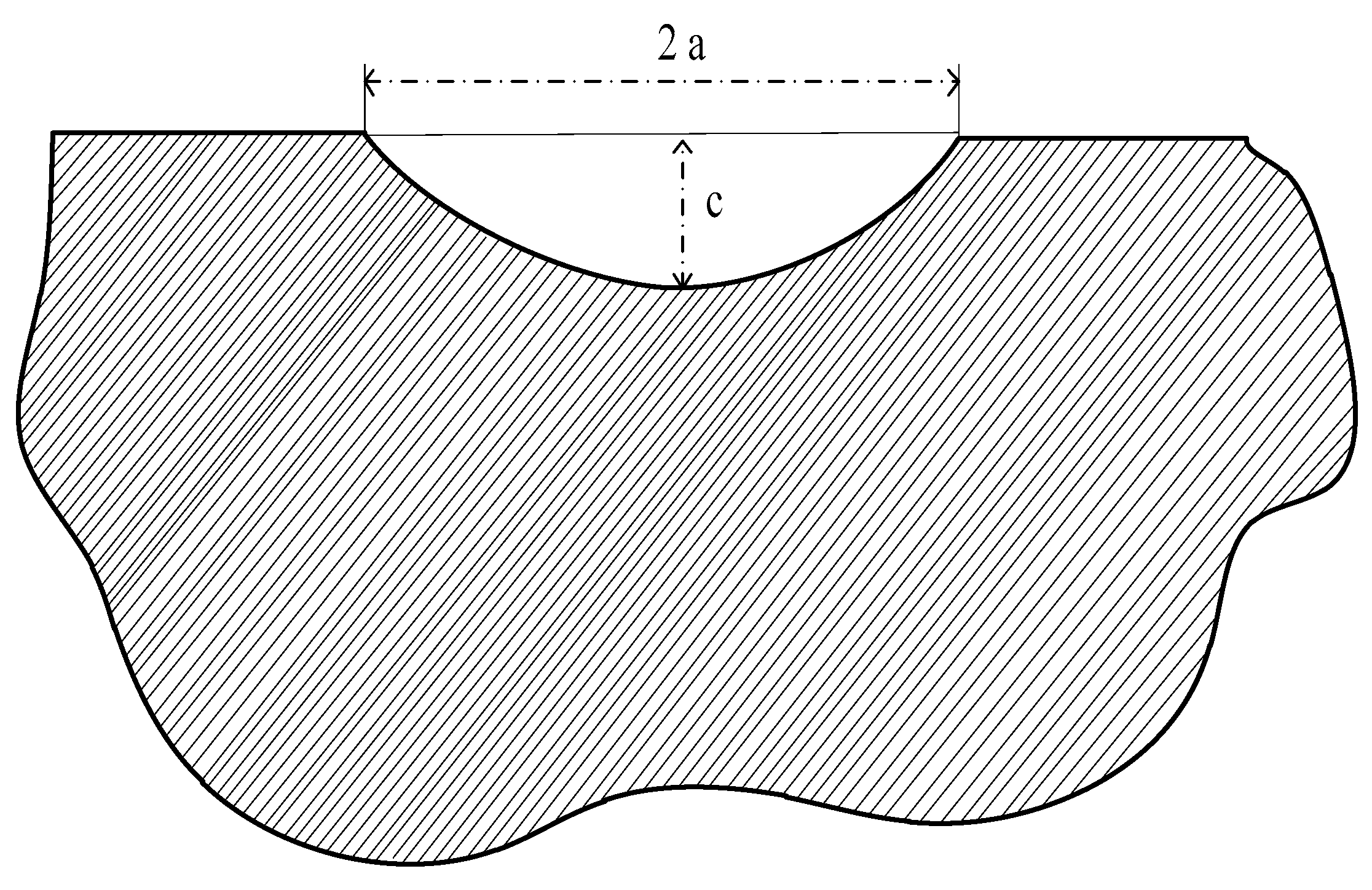

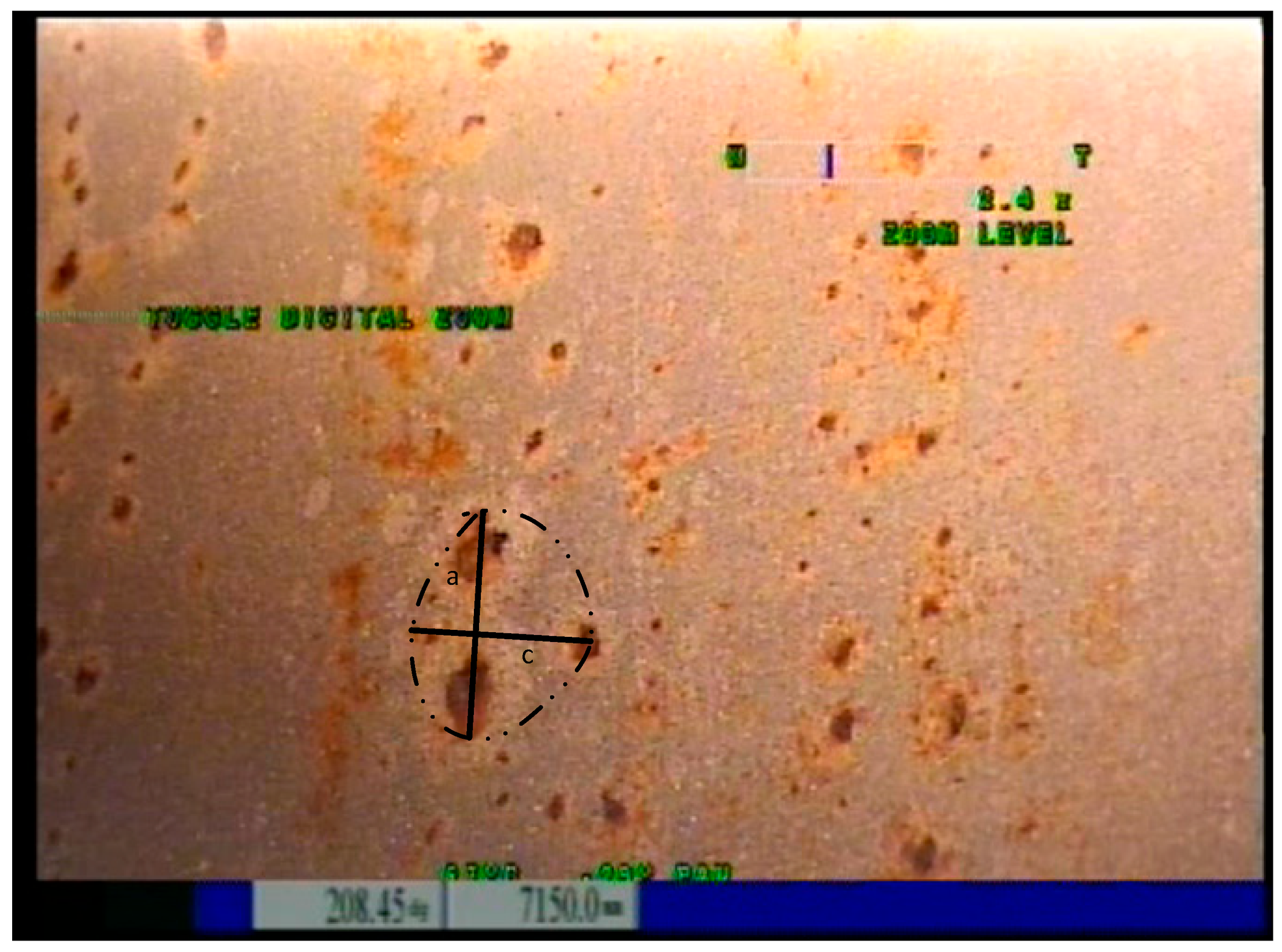

Figure 1. Therefore, it is assumed that the initial cause of the defects is mechanical scuffing from the internal housing devices. The application of a visual method makes it possible to determine characteristics – the type and size of the defects, as well as the coordinates of their location. A study of the defects through a physics-mathematical model of calculations is forthcoming. Surface defects are schematized in the form of semi-ellipses,

Figure 3.

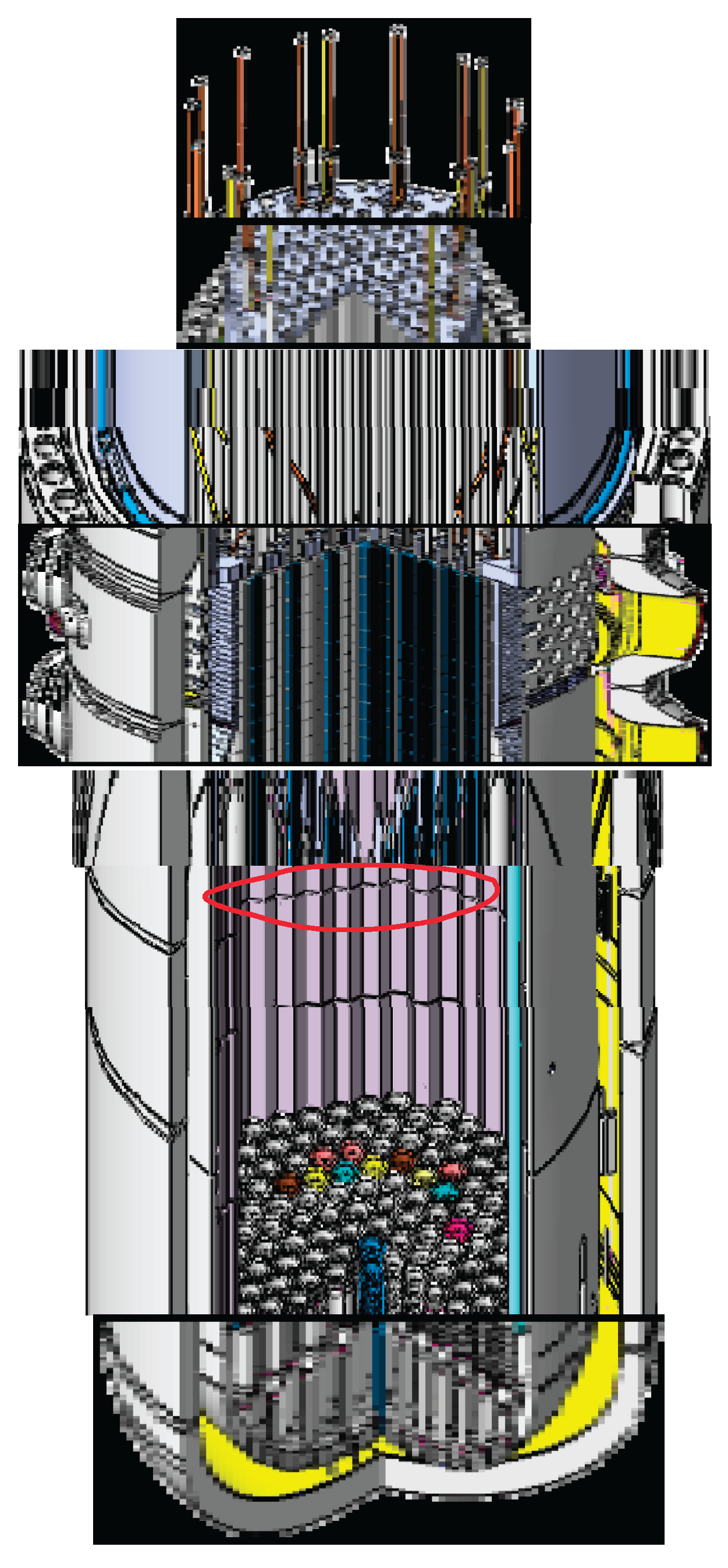

The model for estimating the resistance to brittle fracture of the metal is deterministic. This means that the measured / calculated mechanical characteristics (in the application of the model) are compared with the normative permissible values. Specifically for this study, the calculated values of the stress intensity factor

are compared with the critical factor

(limit values of the coefficients), which are taken from the strength norms, [

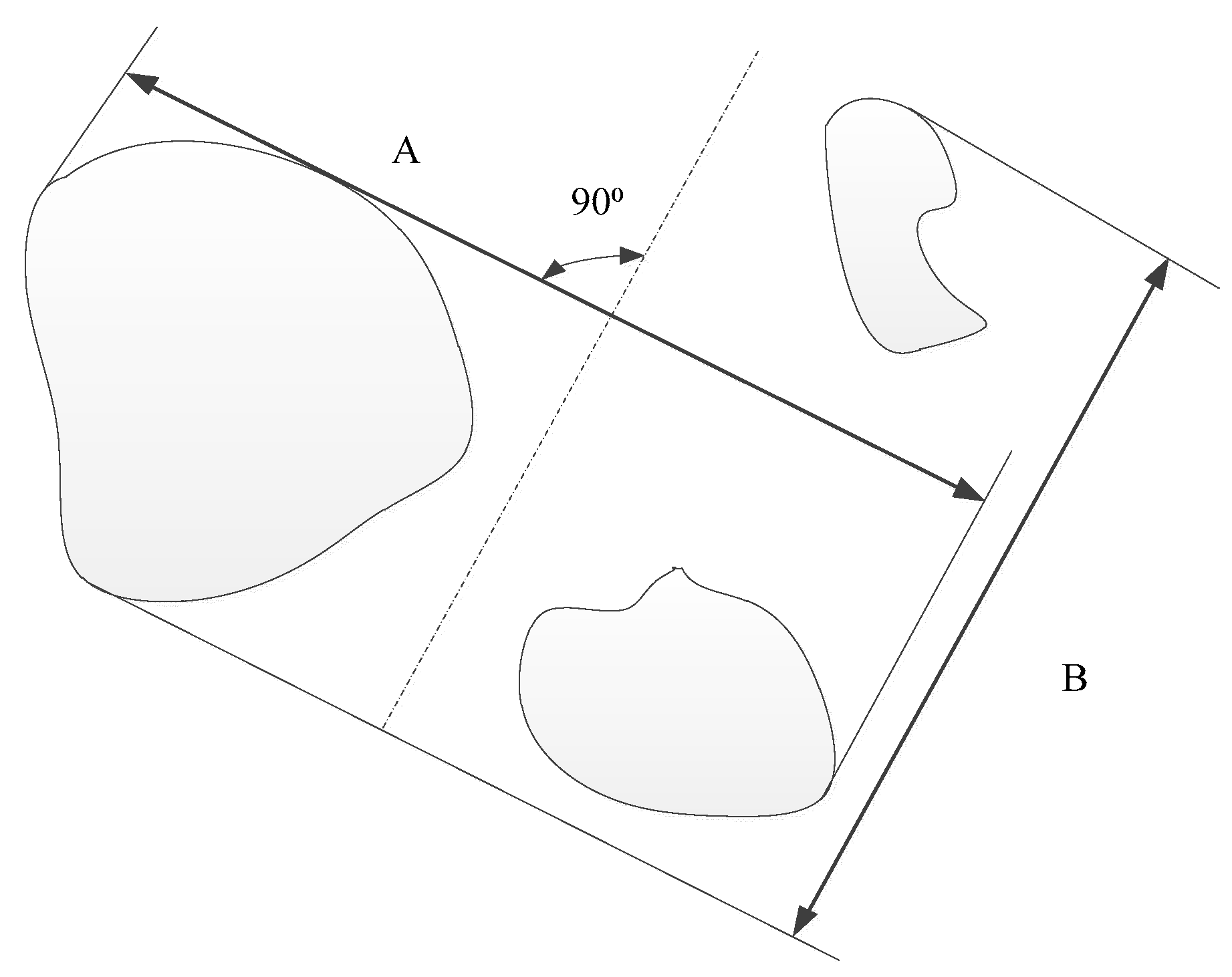

7]. In case several defects are found, closely located, these defects are schematized as one large defect - it is called “cluster” [

9]. A cluster unites two or several inclusions (pores, slag or tungsten inclusions) with the maximum size over 0,2 mm and the minimum distance between their edges less than the distance specified for singular inclusions, but not less than the maximum width of any two adjacent inclusions under consideration. When assessing the distances between the clusters and inclusions the cluster shall be considered as a singular inclusion,

Figure 4.

Stress intensity factor

KI for a surface semi-elliptical crack is determined by the expression, [

7]:

The values of [

KI] are taken in emergency condition mode [

7]:

The dimensions of the defects on the inner surface of the housing are taken from the readings of the visual testing method equipment,

Figure 5.

The values of

at the defect site are determined

, as well the values

are calculated. The calculations are made for selected defects that are of the largest size. For these defects, their location is tracked, considered as the distance from the inner surface of the reactor vessel. The location factor is important because the values of fluence and thermo-hydraulic loads vary at different points on the RPV. Тhe values

are compared with the critical ones

, [

7]. The criterion for evaluating metal with defects in terms of brittle fracture resistance is that the following condition is met:

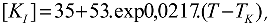

For metals from the inner surface of the reactor vessel, the limit values

constitute a function of

of RPV metal,

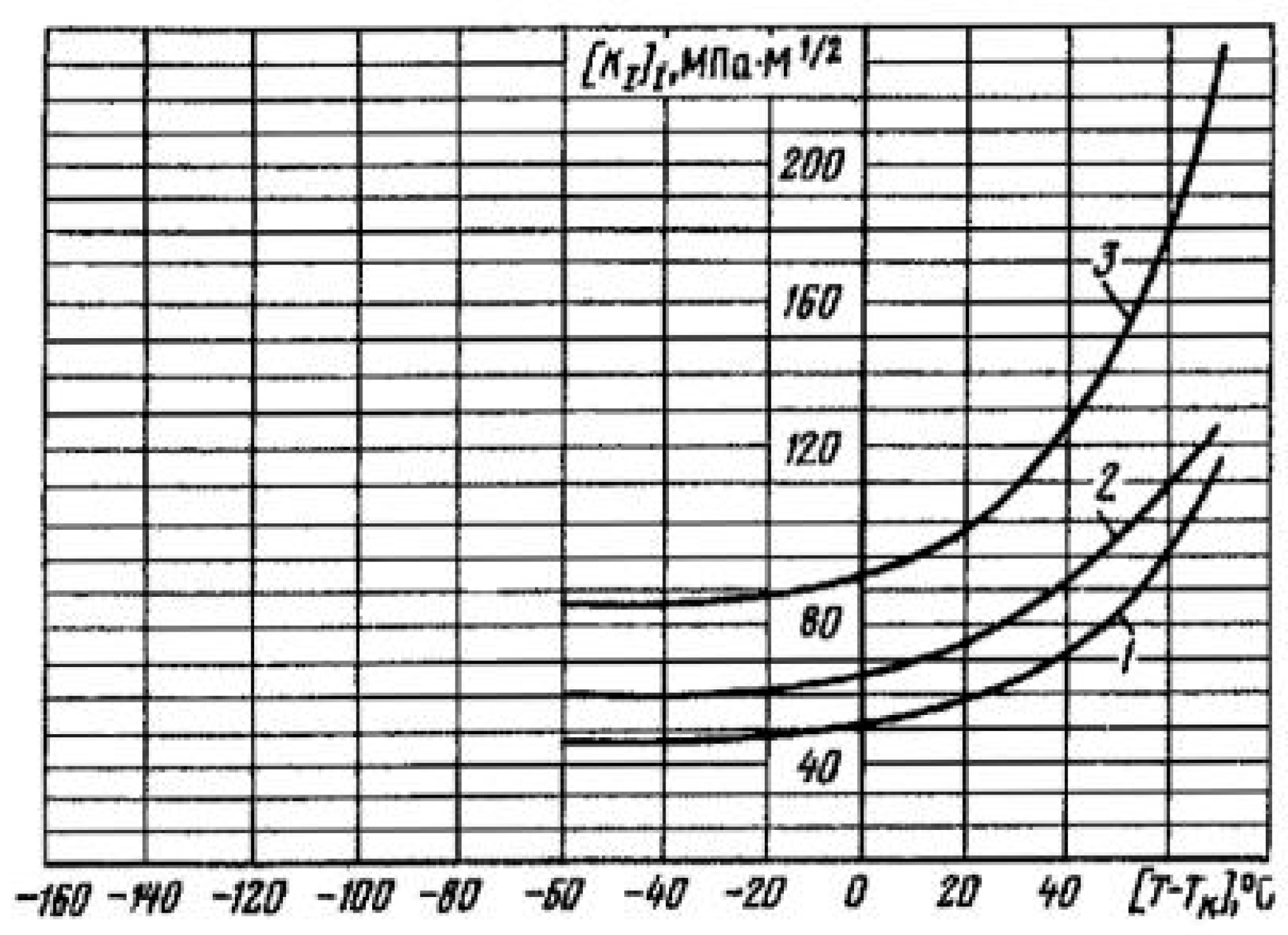

Figure 6.

In order to determine the values of critical stress intensity factors , it is need to find the values of Two methods are known for determining . The first method is a theoretical one - calculations using certain numerical models adopted in normative and methodological documents. The second method is a practical one - through analysis of surveillance specimens’ material. The theoretical method for analysis of is based on calculations. The values of fast neutron fluence with energy greater than 1,5 MeV, reaching the inside of the RPV wall are monitored through the neutron detector readings positioned around the reactor pressure vessel. Data sampling is performed once a year.

The critical temperature of metals during the operation of reactor plants, [

7] is:

In the IAEA documents [

2,

10] for determining the

a numerical models are used:

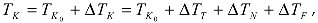

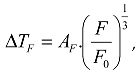

In the last 15 years, it has been assumed that the brittleness of the metal, irradiated for many years with neutron streams with an energy greater than 0,5 MeV is due to neutron and thermal aging. The embrittlement contributions of both components should not be considered separately. The embrittlement process depends on the chemical composition of the alloys, but also on the values of neutron fluence, operating temperature and running hours, which can be expressed as shown below [

4]. The value added to the temperature

shift has two components: one of the components is due to the neutron fluence

, and the other one is due to the thermal embrittlement

.

The practical (experimental) method for analysis of

is based on the results from surveillance specimens impact strength tests. For the purpose of this study, the value of

(F, t) has been calculated, the formulas (6, 9, 10, 11). Calculations were made of the embrittlement critical temperature

on two RPVs with WWER-1000 reactors (referred to as “a” and “b”). The input data for defects from the inner surface of the reactor vessel are: type of inconsistencies, location, relative location, coordinates; sizes; orientations. An explanation of the meaning of the data is given in

Table 1.

It is investigated which are the stressful environmental factors in the location of the identified defects; the influence of the factors is assessed. The operating conditions for the metal from the inner surface of the casing are characterized by intense neutron fluxes with neutron energy above 1,5 МeV; high pressure values (17,5 MPa) and the temperatures of the fluid along the primary circuit (323 ⁰С). Data on the effective stresses in the RPV metal can be obtained in two ways: from passport data and from the manufacturer’s strength analyses, or by strain gauge.

The input data for assessments of the ageing effects are:

Datasheets with the composition of the reactor pressure vessels (passport data).

Data of the fluence on the RPV in the course of each fuel cycle (campaign).

Data from NPP logbooks about the running hours in each fuel cycle.

Data from the surveillance specimens testing.

3. Results

The results of a visual test of the inner surface of the reactor vessel are presented on

Figure 7.

The observed defects of the inner surface is entered into the database and systematized. After 15-17 years of operation of the unit, the first inconsistencies are found, which can be indicated by the test methods. There are corrosion and erosion foci concentrated in the zone of bullying by the reinforcing units of the internal casing devices. Clusters of surface defects in the shell surfacing are observed and their parameters are determined - coordinates and dimensions.

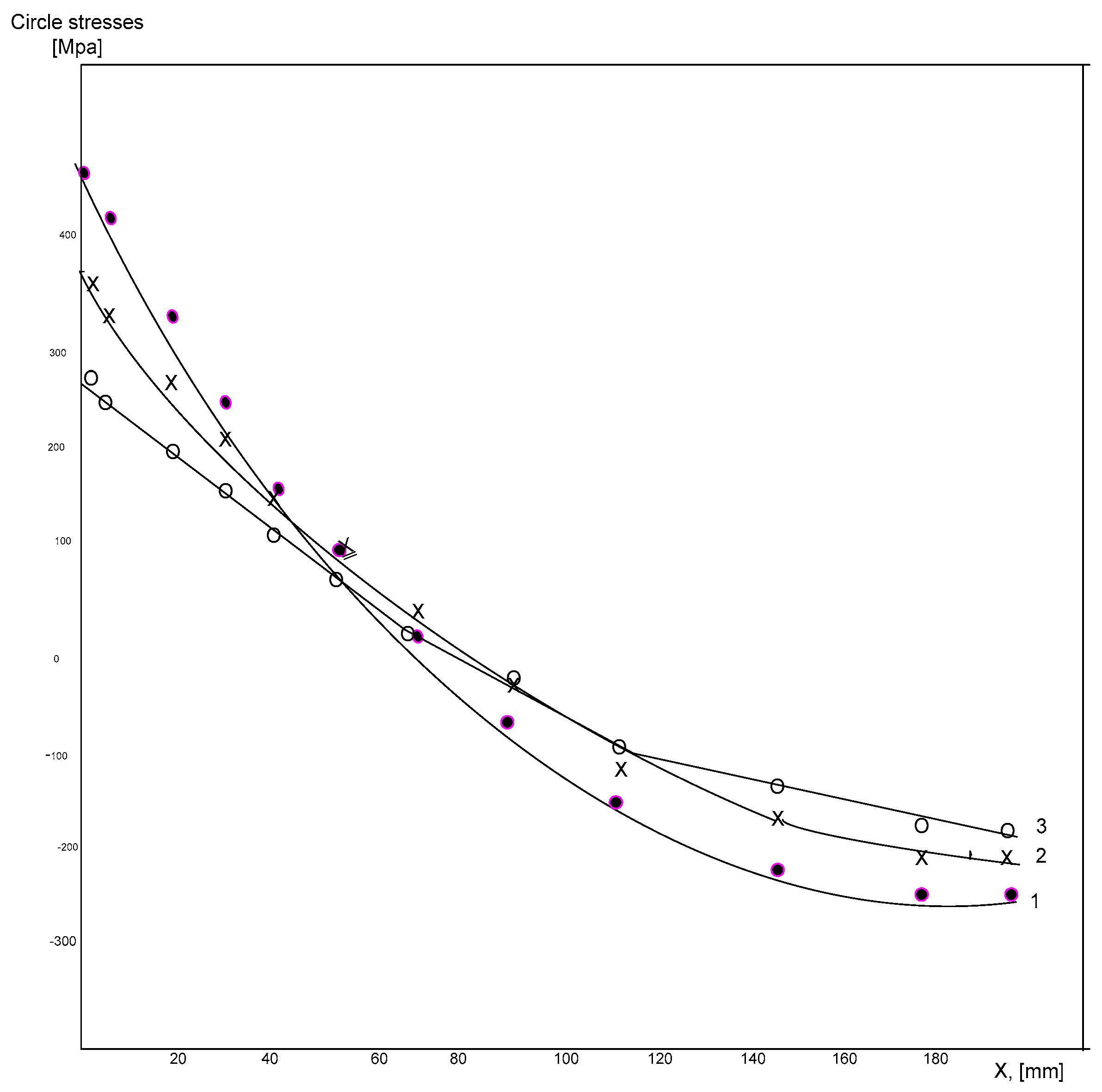

In order to calculate the

, it is necessary to have data on the circular stresses at the location of the defect cluster. Relative stress distribution as a function of the distance X from the boundary of the overlay with the base metal is presented on

Figure 8, for three different points in time since the beginning of the “Big Primary Leak” mode.

Using formula (1) are calculated the values of the stress intensity coefficients

at three different points in time after the start of the “Big Primary Leak” mode,

Table 2.

Further in this study, the values

for the metal, in the location of the defects, are to be calculated. To determine it, we first need to calculate the shift of the critical metal temperature

in the location of the defects. The results of the calculations are given in

Table 3.

The values of the quantities ∆T

inf , b

t, t

ОТ for the pressure vessel metal are summarized in

Table 4.

Function

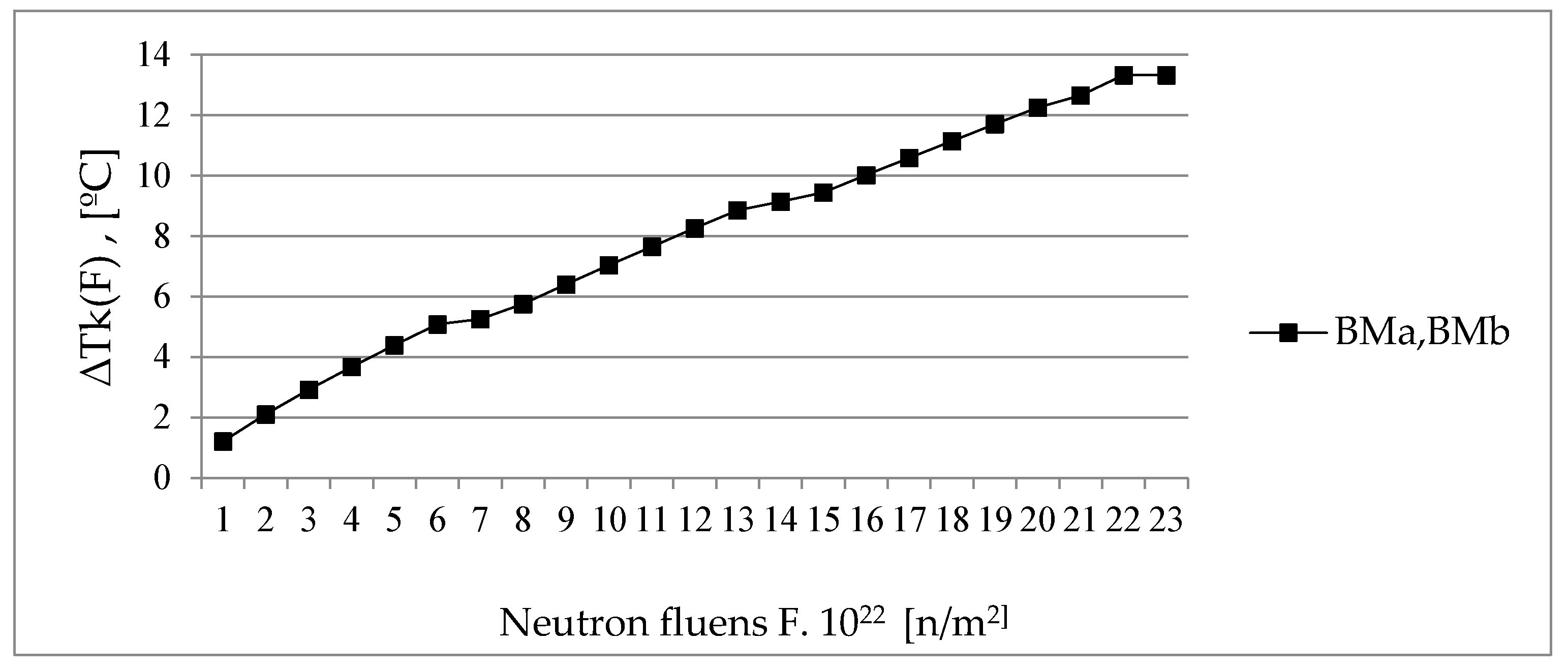

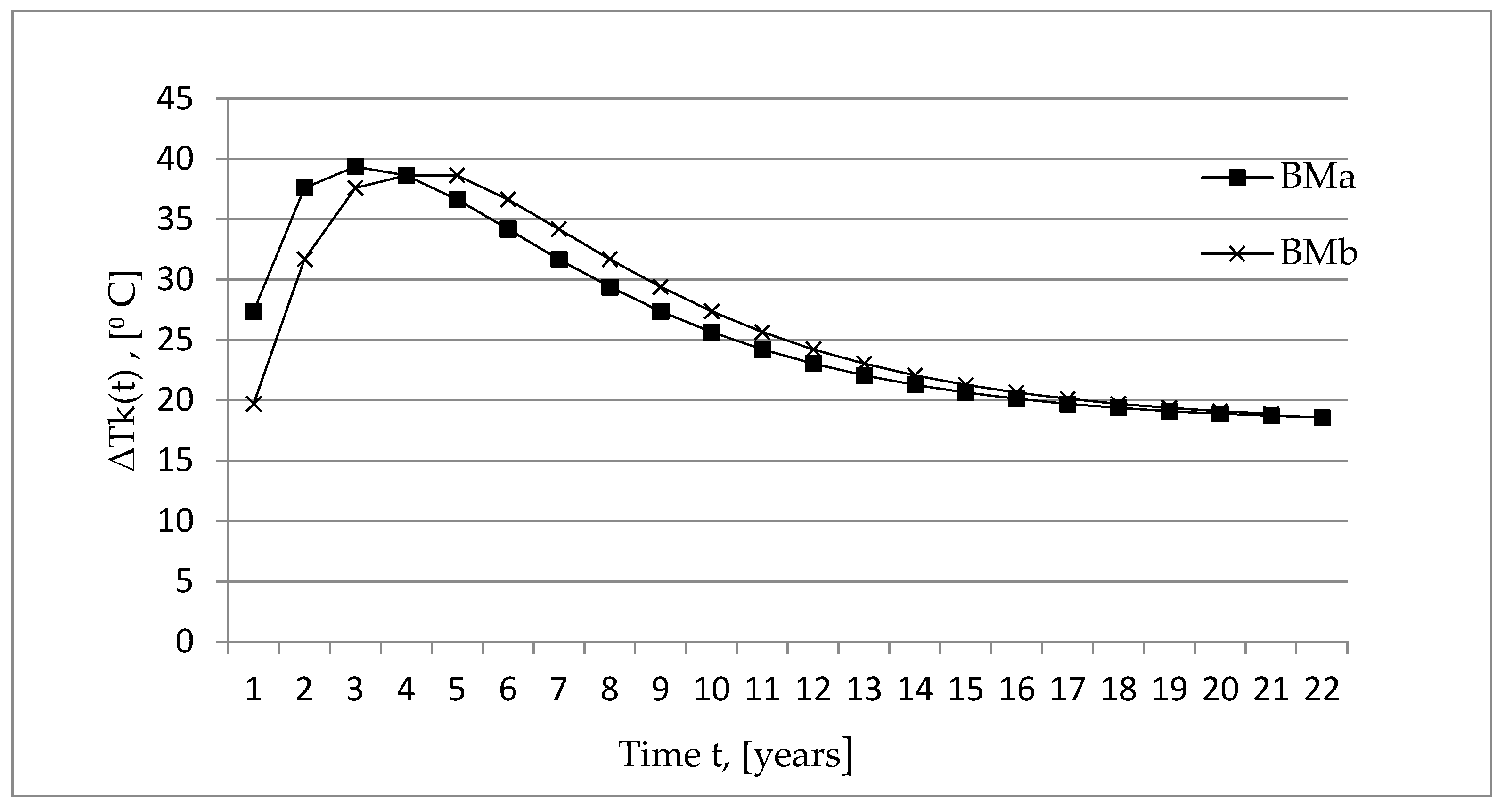

for the base metal of the RPV metals, calculated according to (6) are presented in

Figure 9.

Figure 9 shows a pronounced direct proportional relationship between the shift of critical temperatures and the neutron fluence. The base metal embrittlement of the reactor vessel increases with increasing fluence values. The embrittlement functions of the base metal for the two blocks coincide.

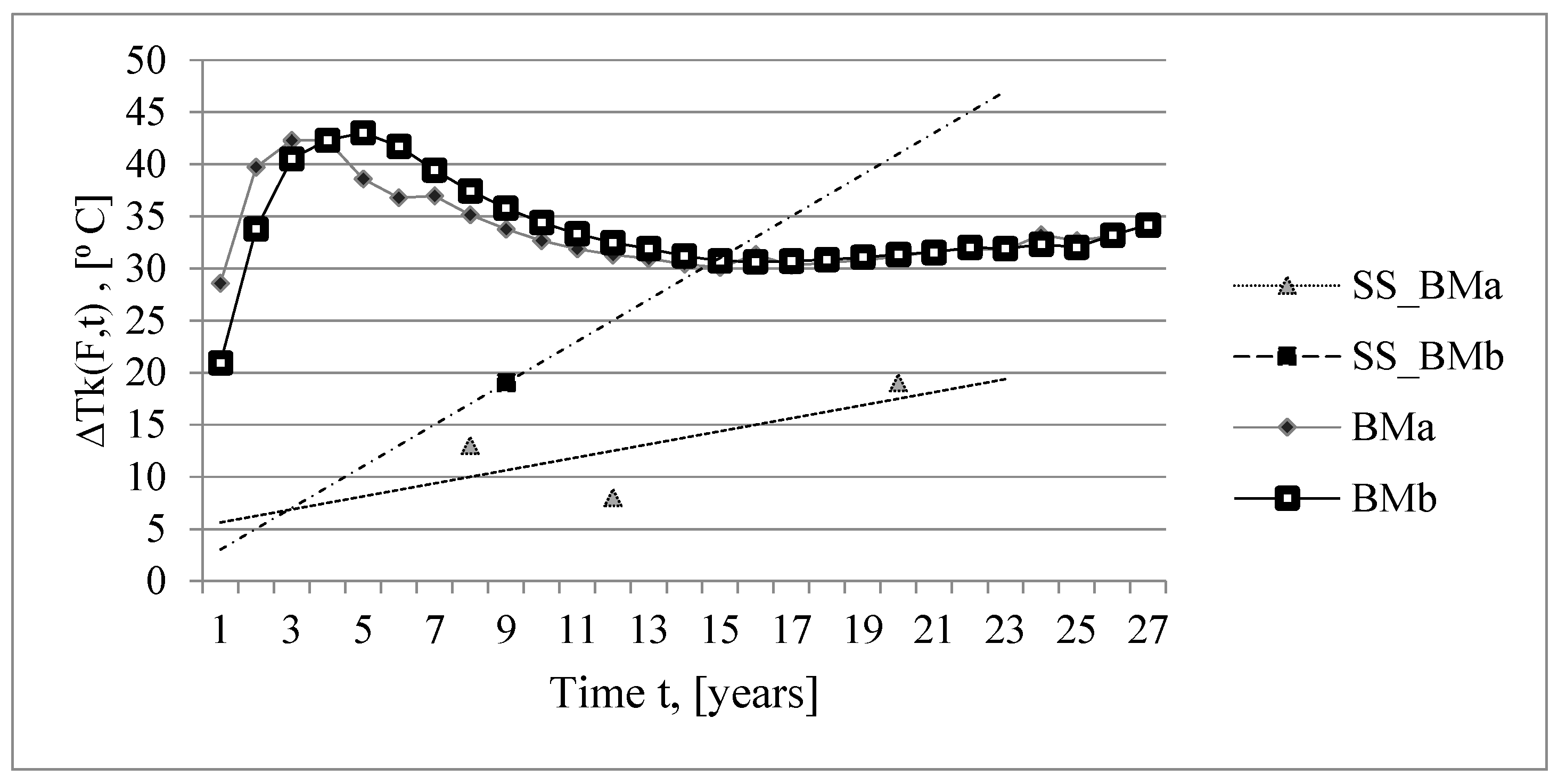

Function

of the RPV base metals, calculated according to (11) are presented in

Figure 10.

Figure 9 shows a nonlinear relationship between the shift of critical temperatures and the time worked. Thermal embrittlement for the base metal of the reactor vessel is maximum for the period of time between the 3-rd and 5-th year from the start of unit operation. After this period, thermal embrittlement decreases exponentially.

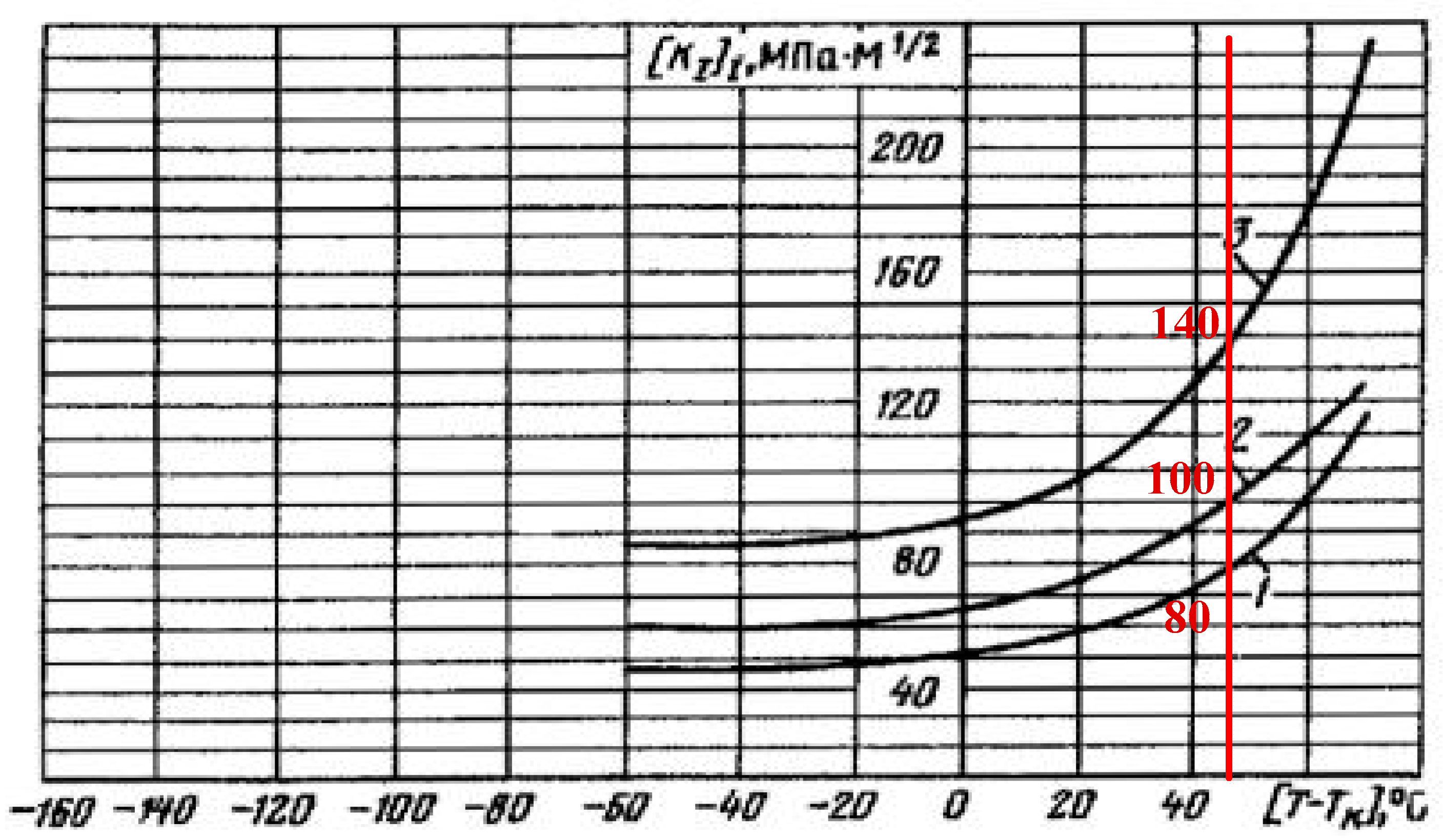

Function

of the RPV base metals, calculated according to (9) are presented in

Figure 11. Data from the experimental base metal tests of the surveillance specimens are also presented in

Figure 11.

The lines in

Figure 11 (BMa and BMb) show the embrittlement of the base metal of nuclear casings “a” and “b”, which is due to the two influencing factors – neutron embrittlement and thermal embrittlement. It is observed that in the first 8-9 years of operation, thermal aging makes the greatest contribution to an increase in the critical temperature of the base metal, and subsequently thermal aging decreases. After 10-11 years, he begins to feel neutron aging.

The resulting values for

the RPV metal are presented in

Table 5.

The values

of the stress intensity coefficients are calculated (3), using the highest value of the shift of the critical temperature of the RPV metal.

The calculated values

are less than the critical values

at

(

Figure 12, red line,

Table 6).

Figure 1.

Reactor Pressure Vessel Internals, area with detected defects is shown in red.

Figure 1.

Reactor Pressure Vessel Internals, area with detected defects is shown in red.

Figure 2.

Visual control equipment and scheme for scanning the RPV inner surface: (a) Underwater system for RPV visual testing; (b) Scheme of visual testing of the RPV metal.

Figure 2.

Visual control equipment and scheme for scanning the RPV inner surface: (a) Underwater system for RPV visual testing; (b) Scheme of visual testing of the RPV metal.

Figure 3.

Surface defect diagram (Semi-ellipse with a semi-major axis “a” and a semi-minor axis “c”.

Figure 3.

Surface defect diagram (Semi-ellipse with a semi-major axis “a” and a semi-minor axis “c”.

Figure 4.

Scheme of a cluster of defects; A, B - cluster dimensions.

Figure 4.

Scheme of a cluster of defects; A, B - cluster dimensions.

Figure 5.

Planning and Conducting Visual control of Reactor Metal.

Figure 5.

Planning and Conducting Visual control of Reactor Metal.

Figure 6.

is a function of

of RPV metal, [

7]. Curve 1 – NOC of the unit; curve 2 – NNOC&HT if the unit; curve 3 – EC of the unit.

Figure 6.

is a function of

of RPV metal, [

7]. Curve 1 – NOC of the unit; curve 2 – NNOC&HT if the unit; curve 3 – EC of the unit.

Figure 7.

Cluster of defects on the inner surface of the reactor vessel.

Figure 7.

Cluster of defects on the inner surface of the reactor vessel.

Figure 8.

Relative Stress Distribution as a Function of the Distance X from the Boundary of the Overlay with the Base Metal. ( e position closest to the inner surface of the Reactor vessel. The current loads have maximum values). Curve 1 – currently 0,2 hours from the time interval of the “Big Primary Leak” mode; Curve 2 – at 0.4 hours; Curve 3 – at 0.6 hours.

Figure 8.

Relative Stress Distribution as a Function of the Distance X from the Boundary of the Overlay with the Base Metal. ( e position closest to the inner surface of the Reactor vessel. The current loads have maximum values). Curve 1 – currently 0,2 hours from the time interval of the “Big Primary Leak” mode; Curve 2 – at 0.4 hours; Curve 3 – at 0.6 hours.

Figure 9.

Function ∆TK(F) for base metal BM of the RPV metals.

Figure 9.

Function ∆TK(F) for base metal BM of the RPV metals.

Figure 10.

Function of the RPV base metals BM.

Figure 10.

Function of the RPV base metals BM.

Figure 11.

Function of the time t for the base metal BM. A mediated line of experimental data from the surveillance specimens SS for the base metal BM.

Figure 11.

Function of the time t for the base metal BM. A mediated line of experimental data from the surveillance specimens SS for the base metal BM.

Figure 12.

Critical values of the stress intensity factors

at

, steels 12Х2МФА, 15Х2МФА, 15Х2МФА-А, [

7].

Figure 12.

Critical values of the stress intensity factors

at

, steels 12Х2МФА, 15Х2МФА, 15Х2МФА-А, [

7].

Table 1.

Input data on defects and their importance for estimates of brittle fracture resistance.

Table 1.

Input data on defects and their importance for estimates of brittle fracture resistance.

| Input data |

Importance for estimates of brittle fracture resistance |

| Type of defects. |

Pores, corrosion ulcers, abrasions on the surface of the metal. The type of defects found is an indicator of degradation mechanisms. |

| Location of defects. |

The location of defects is important for determining the influencing factors and for the assessments. |

| Mutual placement of a group of defects. |

If the defects are closely located, they are evaluated as a group of defects; and if not - as single defects. |

| Defect coordinates. |

Through the coordinates of the defects, they can be detected by subsequent inspection of the site and their development during the operational period is tracked. |

| Defect dimensions. |

The size of the defects is decisive for their admissibility according to normative indicators. |

| Orientation of defects in relation to the direction of the acting stresses. |

Orientation is important and is taken into account in strength analyses. If the acting stresses are perpendicular to the plane of propagation of the defect, then this is a crack of the first kind, the most dangerous for the resource. |

Table 2.

Calculated values of the stress intensity coefficients at three different points in time after the start of the “Big Primary Leak” mode.

Table 2.

Calculated values of the stress intensity coefficients at three different points in time after the start of the “Big Primary Leak” mode.

| A moment in time after the start of the event |

а [m] |

c [m] |

|

|

|

| 0.2 hours |

0,057 |

0,036 |

450 |

|

2,41 |

| 0.4 hours |

370 |

1,98 |

| 0.6 hours |

280 |

1,5 |

Table 3.

Calculated values of the shift of the critical temperature

Table 3.

Calculated values of the shift of the critical temperature

| Position |

F [n / cm2] |

, (7) |

, (2, 10) |

| Base Metal, behind the surfacing, max |

| Block “a” |

Af =23 |

m=0,8; |

| I fuel campaign |

1.060 . 1018

|

23,437 |

1,5191 |

| II fuel campaign |

2.181 . 1018

|

29,74 |

2,7057 |

| III fuel campaign |

3.16 . 1018

|

33,62 |

3,6401 |

| IV fuel campaign |

4.302 . 1018

|

37,22 |

4,6591 |

| V fuel campaign |

5.066 . 1018

|

39,28 |

5,3100 |

| VI fuel campaign |

5.742 . 1018

|

40,94 |

5,8697 |

| VII fuel campaign |

6.912 . 1018

|

43,53 |

6,8084 |

| VIII fuel campaign |

8.033 . 1018

|

45,74 |

7,6783 |

| IX fuel campaign |

9.088 . 1018

|

47,64 |

8,4750 |

| X fuel campaign |

10.325 . 1018

|

49,69 |

9,3859 |

| XI fuel campaign |

10.956 . 1018

|

50,67 |

9,8421 |

| XII fuel campaign |

11,582 . 1018

|

51,61 |

10,2895 |

| Block “b” |

Af =23 |

m=0,8; |

| I fuel campaign |

1.020 . 1018

|

23,1523 |

1,4731 |

| II fuel campaign |

2.080 . 1018

|

29,3588 |

2,6050 |

| III fuel campaign |

3.012 . 1018

|

33,2146 |

3,5030 |

| IV fuel campaign |

4.012 . 1018

|

36,5450 |

4,4061 |

| V fuel campaign |

5.042 . 1018

|

39,4371 |

5,2899 |

| VI fuel campaign |

5.886 . 1018

|

41,5249 |

5,9872 |

| VII fuel campaign |

6.936 . 1018

|

43,8600 |

6,8273 |

| VIII fuel campaign |

7.946 . 1018

|

45,8931 |

7,6117 |

| IX fuel campaign |

8.557 . 1018

|

47,0403 |

8,0765 |

| X fuel campaign |

9.224 . 1018

|

48,2320 |

8,5763 |

| XI fuel campaign |

10.121 . 1018

|

49,7472 |

9,2373 |

Table 4.

Values of the quantities ∆Tinf, bt, tОТ.

Table 4.

Values of the quantities ∆Tinf, bt, tОТ.

|

|

tОТ [hours] |

| 18 |

26.2 |

32 700 |

Table 5.

Values for the RPV metal.

Table 5.

Values for the RPV metal.

| Calculation values |

Test values of SS metal |

| |

According (6) |

According (9) |

Unit “a” |

Unit “b” |

| Unit “a” |

|

|

|

|

| Unit “b” |

|

|

Table 6.

Comparison of the calculated values of with the critical values of .

Table 6.

Comparison of the calculated values of with the critical values of .

|

] |

Comparison of the values |

|

|

| 2,41 |

|

|

80 |

| 1,98 |

| 1,5 |