Introduction

Human adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) have emerged as one of the most clinically relevant cell types in regenerative medicine, particularly within longevity treatment where intravenous MSC injections for atherosclerosis represent a major and growing application worldwide. Over the past decade the conceptual basis for MSC therapy in longevity has shifted away from a simplistic “cell replacement” model towards a multifactorial paradigm in which therapeutic benefit is mediated primarily by immunomodulation, paracrine signalling and the reprogramming of the degenerative joint’s inflammatory microenvironment [

1,

2]. In this context, clinical efficacy depends not only on the number of cells delivered but critically on the condition of the cells at the moment of administration: cells must arrive at the target tissue intact in their biophysical and membrane integrity, metabolically competent and functionally potent [

3]. It follows that the ability to preserve MSC viability and membrane function during the brief but vulnerable interval between final laboratory preparation and patient administration—the “transport viability” problem—is a decisive translational bottleneck.

MSC therapies are exceptional among biologics in that manufacture, final preparation and administration are rarely co-located. Even when a single health system controls both GMP manufacturing and clinical services, the physical separation of clean rooms and outpatient injection suites commonly necessitates temporary storage, transport and on-site re-preparation of MSC suspensions [

4]. On a global scale this challenge is amplified: many clinics depend on centralised GMP facilities and conduct injections in geographically remote satellite clinics that may lie in different cities, countries or regulatory jurisdictions. This model—frequently observed across Asia and other regions—creates repeated logistical constraints in which patients may travel long distances (even internationally) for injection while manufacturing remains localised, placing a premium on short-term transport solutions that preserve cellular quality [

5].

Historically, readily available isotonic saline has been the default carrier for short-term clinical handling of MSCs because of its low cost and presumed biocompatibility. However, an accumulating body of evidence now challenges the assumption that simple electrolyte solutions are innocuous carriers for MSCs. Several independent studies have reported that suspension of MSCs in normal saline can precipitate rapid declines in viability, loss of membrane integrity, up-regulation of apoptotic markers, depolarisation of mitochondrial membrane potential and broader metabolic deterioration within relatively short intervals (hours) after transfer from culture [

6,

7]. From a mechanistic standpoint, the abrupt environmental shift experienced on removal from nutrient-rich, buffered culture media to a simple ionic solution induces osmotic perturbation, loss of metabolic substrates and increased sensitivity to shear and oxidative stresses; these stressors can provoke rapid deterioration of membrane and mitochondrial function that precedes outright cell death. Clinically, such losses are consequential: MSC potency—most notably paracrine immunoregulatory function—is tightly coupled to membrane and mitochondrial integrity, making pre-injection viability a meaningful upstream surrogate for likely in vivo efficacy [14,15,16].

Given these limitations of simple carriers, the translational question is pragmatic: which fluid formulation can preserve MSC viability over the ultra-short intervals typical of clinical workflows without imposing complex cold-chain or cryogenic logistics? The requirement here is intentionally operational rather than theoretical. The desired carrier must perform under ‘infrastructure-minimal’ conditions common to outpatient settings—ideally maintaining cell health for several hours at ambient clinic temperatures (≈20–25°C) and being amenable to bedside handling by nursing or physician staff without specialised equipment. Success in this domain would enable MSC therapies to scale beyond research settings into routine clinical practice.

Polymeric colloids such as dextran represent a leading candidate class for this purpose. Dextran is a branched glucan polysaccharide with a long record of clinical use (for plasma expansion and fluid therapy). Low molecular weight dextran L (≈40 kDa) is an established, marketed, intravenous product whose physicochemical profile suggests plausible membrane-protective effects during short-term handling [

8]. Mechanistically, dextran may confer protection via several complementary actions: osmotic buffering that reduces acute osmotic shock, steric and hydrodynamic effects that limit cell-to-cell aggregation, formation of a hydrated polymer shell that attenuates membrane deformation under shear, and modulation of local microviscosity to dampen mechanical stresses. These hypothesised effects are directly relevant to the biophysical vulnerabilities of MSCs when removed from incubator conditions; even sub-microscopic membrane defects can dramatically impair subsequent in vivo survival and paracrine potency [

9,

10].

Despite the theoretical rationale, rigorous quantitative data examining short-term MSC preservation by dextran L at clinically relevant concentrations and at ambient temperatures remain limited. Much of the literature has focused on cryopreservation, controlled hypothermia (≈4°C) or bespoke preservation formulations that are not approved for direct human injection—factors that reduce translational immediacy [

1]). There is therefore a critical evidence gap concerning whether a clinically approved polymeric IV formulation can meaningfully extend MSC viability in the 1–6 hour window characteristic of outpatient injection workflows, and how such benefit varies with temperature and time.

This study is designed to address that gap. Using human adipose-derived MSCs (a clinically relevant model for orthopaedic applications), we compare viability kinetics in four clinically relevant suspension vehicles—normal saline, dextran L at 5% and 10%, and a commonly used clinical preservation product (CellStore® S)—across temperatures reflecting practical handling scenarios (4°C, ∼25°C, and 37°C). Viability was assessed by trypan blue exclusion using an automated cell counter, and the primary endpoint was percentage viability at 24 hours. The 24-hour endpoint was intentionally chosen as a translational “stress test” to amplify differences between carriers and to identify formulations with robust safety margins for the clinically realistic 1–6 hour window: a formulation that preserves cells at 24 hours would be expected to perform well during shorter, clinically typical intervals. In addition to the primary endpoint, the time course of viability allows estimation of operationally relevant thresholds (for example, the time to significant viability decline) that can inform real-world practice.

Finally, we frame this work within quality-by-design and regulatory perspectives. Cell viability should be considered not as a mere QC checkbox but as an upstream critical quality attribute (CQA) influencing downstream potency-related CQAs—membrane integrity, cytokine secretion and immunomodulatory phenotype [14,15,16]. From an implementation standpoint, the fact that dextran L is an approved intravenous solution in Japan substantially increases its translational appeal: use of an IV-approved medium mitigates the need for a post-storage wash step prior to patient administration, thereby simplifying bedside workflows and reducing handling-associated contamination risk. However, any candidate carrier must be evaluated not only for its biological performance but also in relation to operational constraints (transport time, temperature control, vibration) and regulatory acceptability. This study therefore aims to provide the quantitative, translationally-oriented evidence required to guide operational decisions—such as whether in-house final preparation or outsourced manufacturing with tightly controlled rapid transport is preferable—and to underpin pragmatic recommendations for ensuring patient safety during MSC administration.

Methods

Cell Line, Reagents and Equipment

Cells: Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells from Adipose Tissue (hMSC-AT), PromoCell, Germany. The vendor verified that supplied cells conform to the ISCT minimal criteria (CD73⁺/CD90⁺/CD105⁺, CD14⁻/CD19⁻/CD34⁻/CD45⁻/HLA-DR⁻).

Media and reagents: OHC301T (custom MSC medium), penicillin–streptomycin (Gibco), TrypLE Express (Gibco), PBS(–) (Wako), Trypan Blue 0.4% (Thermo Fisher, etc.).

Carrier media (test vehicles): Normal saline (0.9% NaCl, Otsuka), Lactated Ringer’s solution, and low-molecular-weight dextran L (clinical injectable formulation; Otsuka). Dextran was evaluated primarily at 5% (with 10% assessed where appropriate). All fluids were used sterile and handled aseptically.

Equipment: CO₂ incubator (37°C, 5% CO₂), laminar flow hood, centrifuge (300 × g variable), Countess II FL automated cell counter (Thermo Fisher), electronic temperature logger (per temperature condition), 50 mL sterile conical tubes (Falcon).

MSC Culture and Preparation

Thawing and initial recovery: Vials stored in liquid nitrogen were rapidly thawed in a 37°C water bath, immediately transferred to 20 mL prewarmed OHC301T medium, centrifuged at 300 × g for 5 minutes, and the supernatant removed. Pellets were resuspended in fresh medium and seeded into T25/T75 flasks for recovery at 37°C, 5% CO₂.

Culture conditions: Medium was replaced daily or every 48 hours; cells were passaged at 70–80% confluence. Passaging was performed with TrypLE Express at 37°C for approximately 3–5 minutes, neutralised, centrifuged at 300 × g and reseeded at 3,000–5,000 cells/cm². Passages 3 (P3) were used for experiments.

Quality control: Although vendor certification was supplied, pre-experiment sterility and mycoplasma PCR tests were conducted. Baseline viability before experiments was maintained at ≥95%.

Final Preparation (Re-Suspension) Procedure

Detachment and washing: Cells were detached using TrypLE, washed twice with medium, and centrifuged at 300 × g for 5 minutes. Supernatant was aspirated and cells were re-suspended in the prewarmed carrier solution (normal saline, Lactated Ringer, or dextran L).

Concentration adjustment: Final concentration was adjusted to 5.0 × 10⁶ cells/mL (clinically relevant). Suspensions were gently homogenised by 8–10 slow up-and-down pipetting and dispensed as 10 mL aliquots into sterile 50 mL conical tubes (one tube per replicate per condition). Avoidance of bubbles was emphasised.

Labelling and blinding: Tubes were labelled with random alphanumeric codes to blind the analytical personnel to the carrier identity.

Temperature Conditions and Storage Settings

Each test group was stored under one of three temperature conditions: 4.0 ± 1.0°C (refrigerated), 25.0 ± 1.0°C (room temperature) and 37.0 ± 0.5°C (body temperature equivalent). Storage was performed in temperature-controlled equipment appropriate to each condition (refrigerator, constant temperature chamber or 37°C incubator). An electronic temperature logger (1-minute interval) was placed in each rack to continuously monitor for deviations; log data were archived and appended to each experimental record. Tubes were stored upright and otherwise left static; vigorous shaking or excessive mechanical disturbance was avoided. For separate transport-simulation studies, vibration and temperature fluctuation conditions were designed separately.

Sampling Times and Handling

Sampling schedule: 0 (immediately after re-suspension), 1, 2, 3 and 4 hours.

Pre-sampling handling: Immediately before sampling at each timepoint, tubes were gently inverted three times to restore suspension (avoiding strong shear). A 10 µL aliquot was then drawn from a pre-marked position.

Each timepoint sample volume was fixed at 10 µL and each sample was measured in technical duplicate (yielding biological replicates N = 3 × technical duplicates = 2 per biological replicate).

Viability Measurement (Trypan Blue / Countess II FL)

Staining: A 10 µL aliquot was mixed 1:1 with 0.4% trypan blue in a microtube and incubated for ~1 minute.

Measurement: 10 µL of the stained mixture was loaded onto the Countess slide. Measurements were performed in bright-field mode on the Countess II FL. Suggested instrument settings (adjustable for local instrument calibration): bright-field mode, fields = 4, minimum cell size 7 µm, maximum 50 µm, threshold auto.

Calculation: Viability (%) = (live cell count) / (live + dead cell count) × 100. The mean of the technical duplicates was taken as the value for each biological replicate.

Data storage: Countess output (viability, total cell counts, dead cell counts and images) was archived with timestamps as raw data.

Bias Mitigation and Quality Assurance

Blinding: Analysts performed measurements using sample codes only; carrier identities remained concealed until analysis completion.

Standardised equipment: Identical pipettes, tube types and the same Countess device were used for all measurements; operators followed a standard operating procedure (SOP).

Temperature verification: Temperature loggers were calibrated prior to experiments. Any run with temperature deviations was excluded and repeated.

Pre-processing QC: Batch acceptance criteria required ≥95% viability at baseline (0 hour).

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics: Mean ± standard deviation (SD) were calculated for each condition and timepoint. Time course trends were visualised with survival (%) vs time plots, colour-coded by carrier and temperature.

Exploratory inference: As an exploratory translational study, two-factor repeated measures ANOVA (carrier × time; temperature × time) was used supplementary to assess interactions. Multiple comparisons were corrected using Bonferroni adjustment; p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The primary interpretation remained descriptive.

Sample size: Biological replicates N = 3 (independently prepared cell suspensions) with technical duplicates per replicate. Future confirmatory studies will adjust sample size based on observed effect sizes.

Results

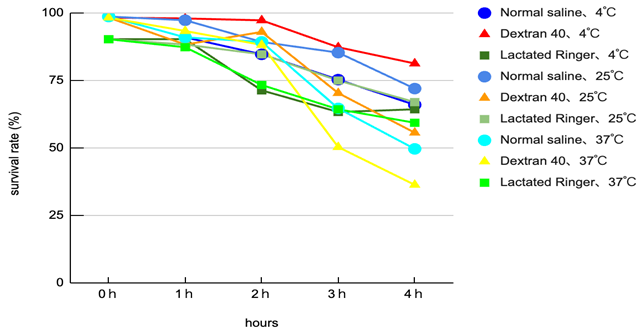

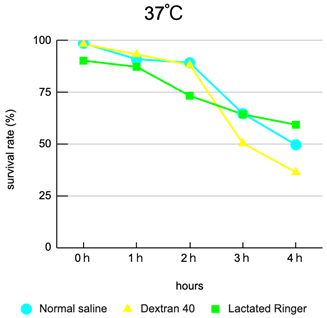

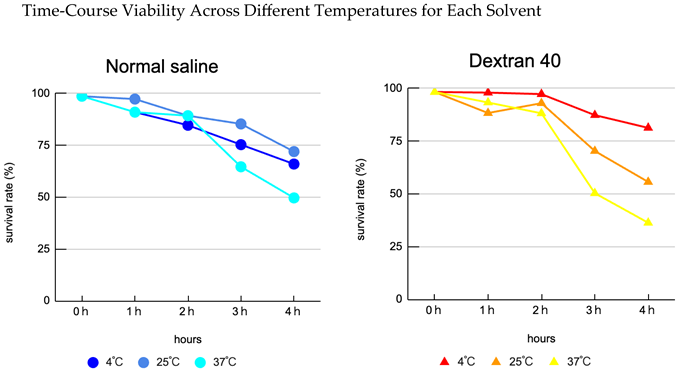

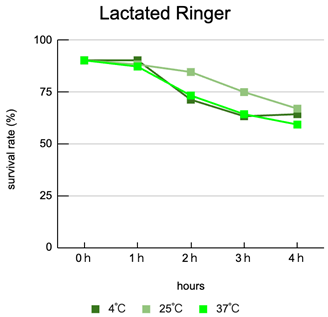

Interaction of carrier and temperature: Viability varied clearly according to the combination of carrier composition and storage temperature. Overall, lower temperature (4°C) tended to mitigate declines in viability, with dextran L conditions showing superior preservation relative to other carriers.

Limit of the best condition: The 4°C × dextran L condition preserved viability best overall; however, even under this condition, approximately 20% cell death was observed at 4 hours (i.e. viability fell to roughly 80%), indicating insufficient protection for prolonged storage (see experimental data).

Thermal acceleration of decline: At 25–37°C, many carriers exhibited rapid declines in viability after 3 hours, with storage at 37°C being particularly deleterious—suggesting that waiting at body-temperature-like conditions during clinical handling represents a substantial risk.

Clinical time window alignment: The observed trends suggest that if injection occurs within 2 hours of the final laboratory preparation in most carrier and temperature combinations, major declines in viability are generally avoided; delays of ≥3 hours are associated with appreciable loss of viability (plot: viability vs time by carrier and temperature). Each condition was performed in triplicate (N = 3) and averages were plotted.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that combinations of clinically realistic storage temperatures and diluent formulations substantially affect pre-administration MSC viability under conditions that plausibly occur in clinical practice. Key implications are as follows.

Carrier selection and temperature management interact: Mild cooling to 4°C combined with a polymeric membrane-protective carrier (dextran L) provided the greatest preservation of viability. However, this protective effect is time-limited; approximately 20% cell death after 4 hours indicates that even an optimal carrier cannot fully mitigate the risk of prolonged transport. Thus, long transport durations remain hazardous even with the best available solution.

Clinical implication — proposal of a 2-hour rule: From a practical standpoint, our data support a working clinical guideline that MSCs finalised in the laboratory should be administered within 2 hours. This is especially important when using outsourced manufacturing, since transport, customs and in-hospital processing can introduce delays; managing these is therefore a primary safety concern.

Outsourcing versus in-house manufacturing: Outsourced manufacturing offers scale and standardisation advantages but introduces the new quality risk of transport time. Ideally, the final re-suspension and administration would be completed in-house immediately prior to injection. If transport is unavoidable, a combined approach—short transit (<2 h), cooling (4°C) and the use of a polymeric protective solution—should be implemented. These measures require investment and trade-offs regarding regulation, operations and cost, but are necessary to secure patient safety.

Limitations

This exploratory study had limitations. It was relatively small in scale and did not assess donor diversity. Functional potency endpoints (cytokine secretion, immunomodulatory assays) and multi-omics measures of biological damage were not included. Additionally, more realistic transport simulations incorporating vibration and temperature fluctuations are required to fully characterise operational risks.

Ethics and Safety

Only commercially available human adipose-derived MSCs were used. No new human subjects, clinical interventions, or animal experiments were performed; institutional ethical approval was therefore not required. The cell supplier complied with donor screening, informed consent and IRB governance. All procedures complied with institutional biosafety requirements and operators adhered to appropriate PPE and biosafety protocols.

Conclusions

When cultured cells are re-suspended in various carrier fluids prior to patient administration, combinations of temperature and solution composition produce substantial differences in time-dependent viability. In this study, 4°C × dextran L preserved viability best, but even so ~20% cell death occurred at 4 hours, indicating that this combination is not clinically ideal for prolonged storage. Considering real-world clinical operations, it is desirable that the laboratory-to-patient interval be within 2 hours; where external cell-processing facilities are used, rigorous management of transport time is pivotal to ensuring safety. Future studies incorporating functional assays and realistic transport conditions are needed to establish operational guidelines.

Data Availability Statement

Reference and supplementary data are available in the experimental notes and the ambient-temperature dextran evaluation materials referenced here.

References

- Galipeau, J; Sensebé, L. Mesenchymal stromal cells: Compliance and standardisation of clinical trial reporting. Cytotherapy. 2018, 20(2), 151–154. [Google Scholar]

- Moll, G; Drzeniek, N; Kamhieh-Milz, J; et al. Mesenchymal stromal cells in regenerative medicine: immunomodulation and therapeutic mechanisms. Nat Rev Immunol. 2022, 22, 706–724. [Google Scholar]

- Loebel, C; Mauck, RL. Mechanobiology of mesenchymal stromal cells: implications for cell preservation. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2020, 16, 303–318. [Google Scholar]

- Bianco, P. Mesenchymal stromal cells: revisiting conventional concepts. Cell Stem Cell. 2014, 14(3), 253–264. [Google Scholar]

- Kilpinen, L; et al. Cryopreservation of human mesenchymal stromal cells: viability, recovery and functional characteristics. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2013, 4(12), 148. [Google Scholar]

- De la Torre, P; et al. Effect of diluent composition on MSC viability and morphological stability. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2021, 27(3), 133–142. [Google Scholar]

- Galipeau, J. The Mesenchymal Stromal Cell dilemma: Is there a cutting-edge standardisation framework? Stem Cell Transl Med. 2021, 10(6), 861–867. [Google Scholar]

- Bahsoun, S; et al. Effects of cryopreservation and post-thaw culture conditions on MSC phenotype. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2020, 8, 148. [Google Scholar]

- Chinnadurai, R; et al. Potency assays after cryopreservation and thawing of MSCs. Mol Ther. 2016, 24(6), 1167–1177. [Google Scholar]

- Shou, Y; et al. Influence of storage temperature and conditions on MSC viability and mitochondrial function. Cryobiology. 2022, 106, 59–66. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, J; et al. Optimisation strategies for short-term storage of MSCs intended for clinical injection. J Transl Med. 2023, 21, 412. [Google Scholar]

- Panés, J; et al. Mesenchymal stromal cell therapy — challenges and future directions in clinical application. J Clin Med. 2022, 11(21), 6638. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).