1. Introduction

The increase in musculoskeletal disorders has raised significant concern in recent decades. The World Health Organization (WHO) confirms that musculoskeletal diseases contribute the most to global disability. These conditions range from acute, short-duration pain to lifelong disorders, such as osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, osteoporosis, and low back pain [

1]. They affect both young and older populations, leading to significant socioeconomic and psychosocial impacts [

2]. Current treatments for these disorders include therapeutic options such as analgesics, anti-inflammatories, and physiotherapy. However, a significant number of patients are refractory to these treatments, for whom surgical intervention is the only option [

3]. Besides that, tissue engineering is viewed as a viable alternative to conventional therapies for muscle, bone, and cartilage lesions in major centers from cell approach techniques based on mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) [

4]. The MSCs possess immunomodulatory, anti-inflammatory, and anti-apoptotic mechanisms that vary according to the environment. In response, they secrete large quantities of various bioactive molecules, and modulating the extracellular microenvironment [

5,

6]. The potential of MSCs to differentiate into multiple cell types represents a promising application for various pathological conditions, where increased local cellularity can enhance healing, regeneration, and repair processes [

7].

At present, cell therapy-based treatments are offered exclusively at specialized reference centers, that often have expertise in specific laboratory techniques and facilities for cell production, processing, and storage from stem cell transplantation. Many private centers participate in clinical trials to test the safety and effectiveness of new innovative therapies and they provide cell therapies to patients, in often specialized areas. Supporting cost estimation and strategic planning for cell-based therapies in academic and small-scale settings, may promoting efficient resource use and product development. In this sense, an alternative is based on the orthobiologics.

Orthobiologics are substances found in the human body that possess potential properties to modify diseases, which may benefit patients with injuries [

2]. This includes therapy with Bone Marrow Aspirate Concentrate (BMAC), which has been noted as a promising tool for regeneration due to its abundant source of mesenchymal stromal cells and growth factors [

8]. According to the regulations regarding human cells, tissues, and tissue-based products established by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the biological properties of bone marrow can be concentrated using various methodologies that produce a cell suspension for reinjection, allowing application to patients on the same day [

9]. Bone marrow (BM) is primarily composed of hematopoietic cells, adipose tissue, and stromal support cells [

10]. It contains a heterogeneous population of stromal cells, also known as mesenchymal stromal cells, which can be isolated

in vitro [

11,

12]. In 2006, the Committee of Mesenchymal and Stem Cells and Tissue of the International Society of Cell Therapy established the minimum identification characteristics for human mesenchymal stem cells (MSC): (a) cells adhering to plastic when maintained under standard culture conditions; (b) expression of CD105, CD73, and CD90, and absence of expression of CD45, CD34, CD14 or CD11b, CD79a or CD19, and HLA-DR surface molecules; and (c) the capacity to differentiate into osteoblasts, adipocytes, and chondroblasts

in vitro [

13].

Due to regulatory aspects regarding the use of MSCs, a crucial concept of “minimal manipulations” has been adopted. When the cells are not expanded but are manipulated in a hospital environment, the application of MSCs is more readily accepted, as the cells can be managed outside the limits of clinical trials approved by local authorities and National Ministries of Health [

14]. BMAC is a viable procedure because it allows for the drawing and application of the biological product without needing to perform manipulations in a laboratory, thereby reducing costs while maintaining regulatory conformity [

2]. Using non-cultured autologous cells reduces the risks of infection, disease transmission, sample incompatibility, and cost compared to autologous cells or those expanded in culture [

15]. As long as the operator works carefully in a facility validated with adequate aseptic techniques, this orthobiological material does not pose a risk of disease transmission or infection, allowing it to be used concurrently with another procedure. This procedure offers the unique advantage of enabling both the drawing and subsequent transplant of MSCs to the affected site in a single session of the procedure [

16].

Therefore, high-level studies are needed to support the use of intraarticular injections of BMAC in patients with various osteomuscular pathologies [

17]. Thus, the objective of our study is to compare two distinct protocols for obtaining a concentrate of MSCs in a sterile closed system. By providing detailed, step-by-step guidance, with low-cost for immediate use during surgery, while also consolidating knowledge about (i) the standardization of the autologous protocol, (ii) the composition of the bone marrow stem cell concentrates, and (iii) the reproducibility of the applied techniques that can be applied in smaller centers with poor laboratory technology and healthcare facilities. This work, finally, aims to bridge current gaps in cell protocol-manufacturing and promote the sustainable integration of cell therapies into clinical practice.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Statement

This study was approved by the Committee of Research Ethics at Caxias do Sul University (UCS) under CAAE: 42668520.0.0000.5431, approval number: 5.259.139. Written consent was obtained from the patients before their enrollment in the study, in accordance with Resolution n° 466/12 of the Brazilian National Health Council.

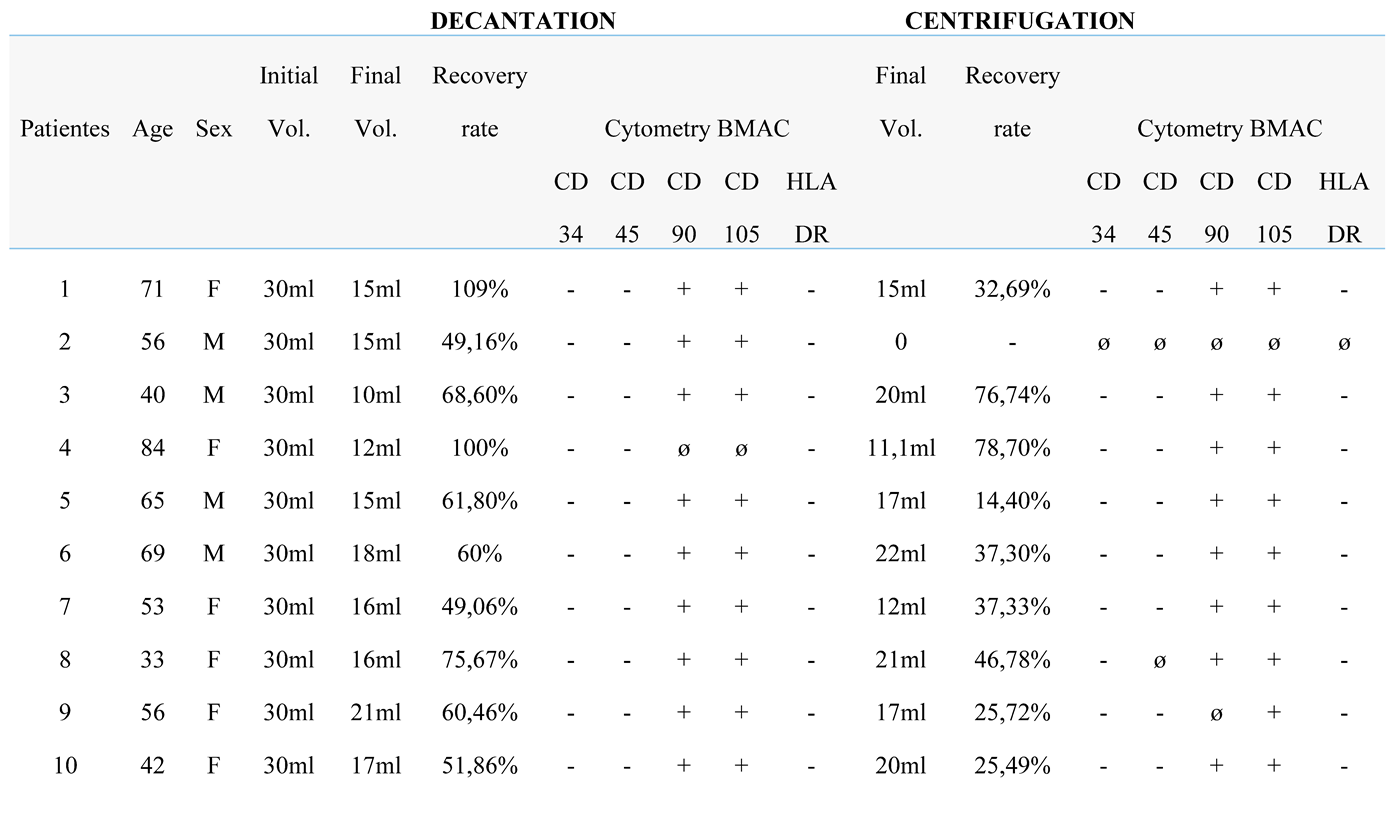

2.2. Blood Bone Marrow Collection

Bone marrow (BM) harvesting was performed through a single puncture of the posterior iliac crest under anesthetic sedation. A myelogram puncture needle and a heparinized 20 mL syringe were used to access the iliac crest, with the needle angulated as needed; no additional skin incisions were required. A total of 60 mL of BM was collected per patient using three 20 mL syringes. The aspirate was immediately transported to the Center for Production and Cellular Therapies at the University of Caxias do Sul. Bone marrow aspiration did not interfere with surgical procedures and had no impact on operative time, patient management, wound healing, or postoperative recovery.

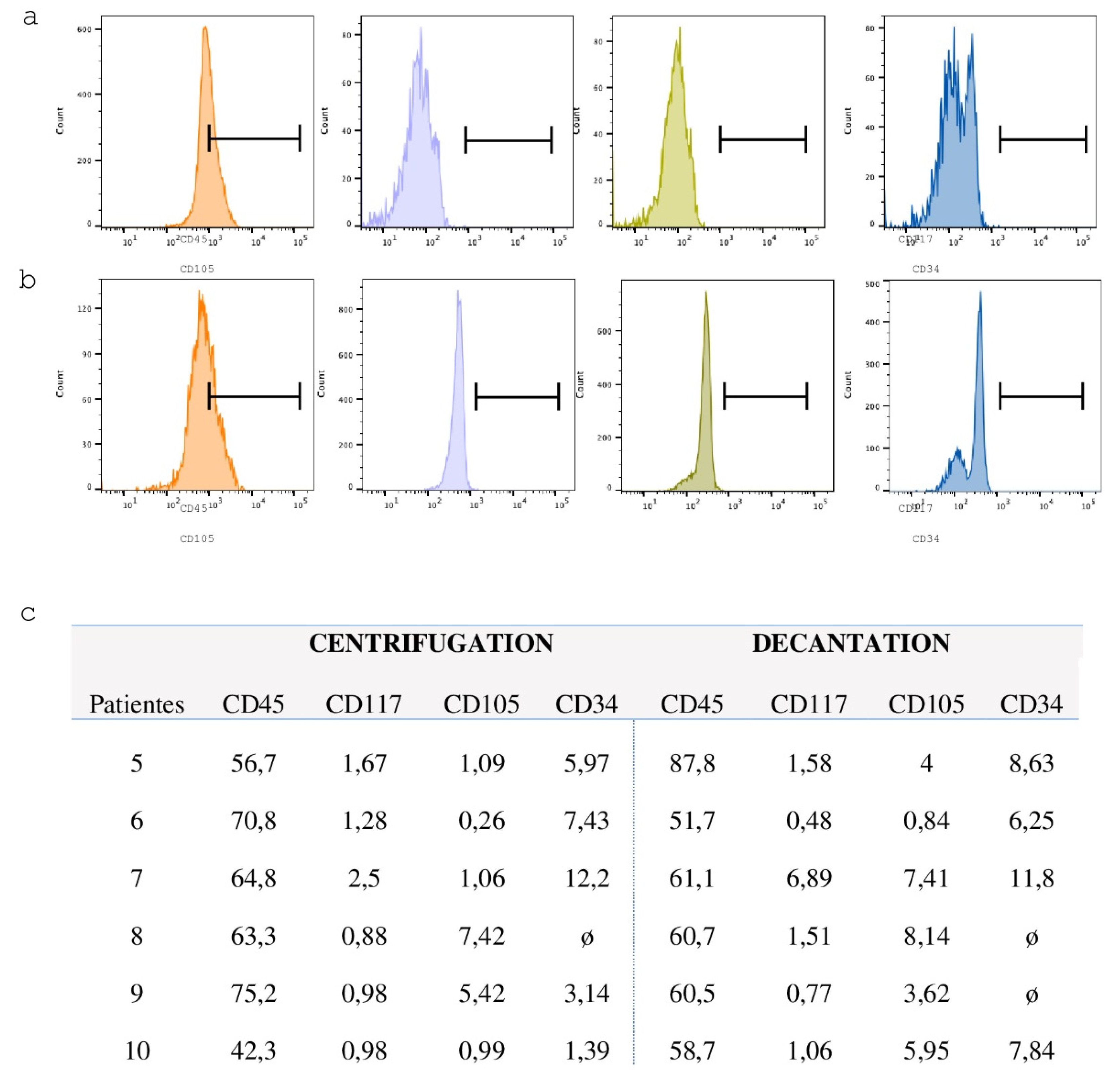

Each 60 mL BM sample was stratified and divided equally into two 150 mL blood collection bags (JP Farma, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil), with 30 mL per bag. A 500 µL aliquot (pre-processing sample) was transferred to a 1.6 mL microtube for subsequent hematological analysis. The BM aspirate was then processed using two distinct protocols to isolate the lymphomononuclear cell fraction: a centrifugation-based protocol and a sedimentation-based protocol (

Figure 1).

2.3. Centrifugation Protocol

The bag containing 30 mL of BM aspirate was centrifuged (Multispeed Centrifuge PK 131) at 84 g for 12 minutes to precipitate the erythrocytes and separate the lymphomononuclear fraction, which is located at the interface between the erythrocytes and the plasma. Following centrifugation, a 20 mL syringe was connected to the bag system to aspirate and discard the erythrocyte layer. The remaining content, composed of plasma and lymphomononuclear cells, was gently homogenized. A 500 µL aliquot of the post-processing material was transferred to a 1.5 mL microtube for subsequent hematological analysis (

Figure 1).

2.4. Decantation Protocol

The BM aspirate bag was placed on a support measuring 27 cm in height, angled at 30 degrees and left undisturbed for one hour to allow sedimentation of erythrocytes and plasma. At the end of the sedimentation period, a 20 mL syringe was connected to the bag system. The erythrocyte layer was aspirated and discarded, and the remaining concentrate was gently homogenized. A 500 µL aliquot of the post-processing material was transferred to a 1.5 mL microtube for subsequent hematological analysis (

Figure 1).

2.5. Cell Recovery Rate

BM samples collected immediately after aspiration (pre-processing) and after processing by centrifugation and sedimentation protocols (post-processing) were diluted at a 1:1 ratio for differential cell counting using a hematology analyzer (Mindray). The following parameters were quantified: total leukocyte count, erythrocyte count, platelet count, and hemoglobin concentration. The data obtained were used to calculate the white blood cell (WBC) recovery rate using the following formula: Recovery rate (%) = total WBC initial x 100 / total WBC final.

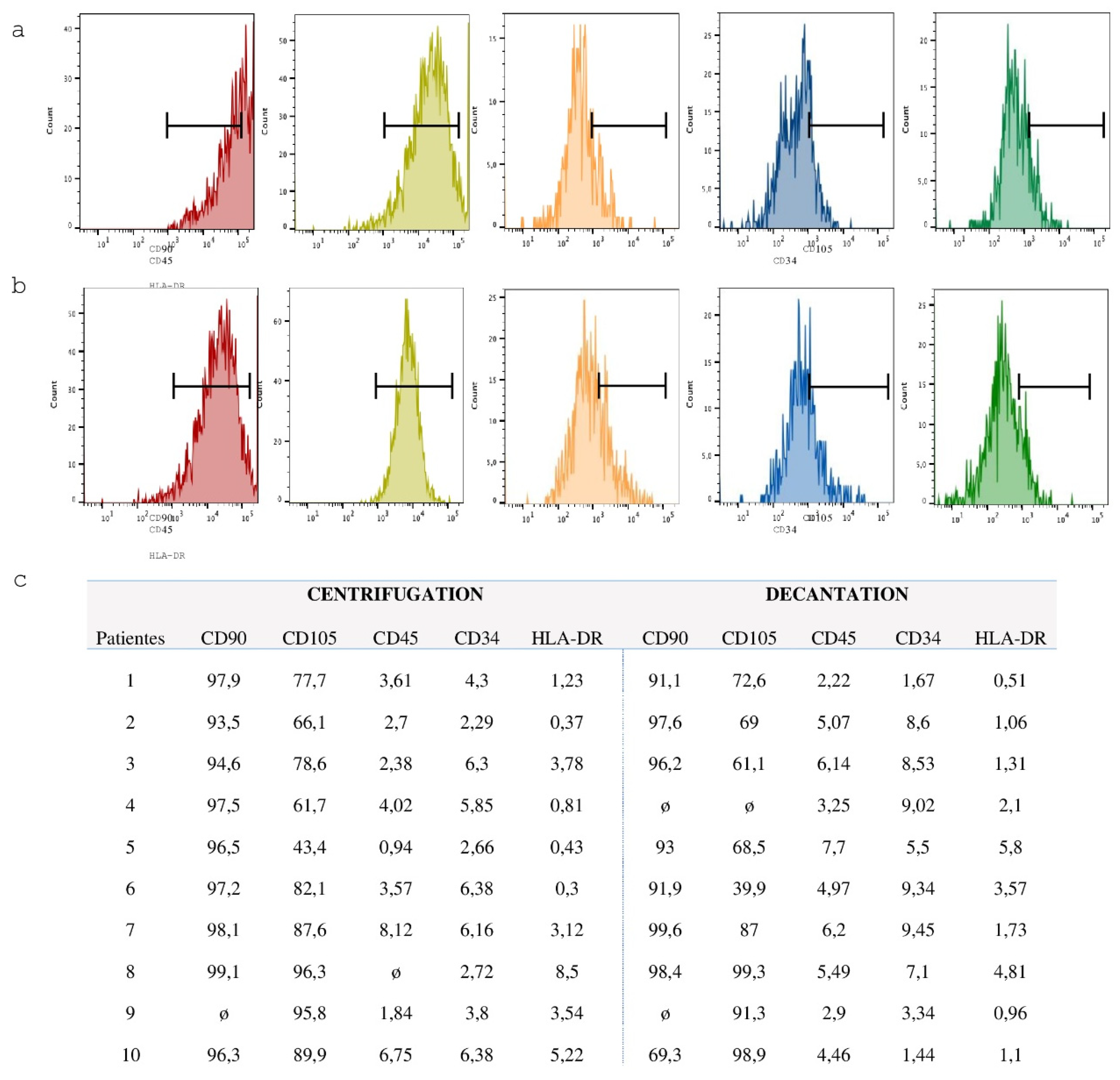

2.6. Expansion of Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSC)

For cell culture, 1 mL of each fraction obtained from the centrifugation and decantation protocols was transferred to individual wells of a 6-well culture plate. Each well received an additional 2 mL of Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 µg/mL streptomycin. Final concentrate volumes were adjusted to 1.0 mL, 0.5 mL, and 0.25 mL to evaluate cell expansion under different conditions. Cultures were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified incubator with 95% humidity and 5% CO₂. After 48 hours, 50% of the culture medium, containing both the cell fraction and DMEM, was carefully removed and replaced with fresh medium. At 96 hours, wells containing plastic-adherent mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) were washed twice with 1X phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and the medium was fully replaced with fresh DMEM. Cells were subsequently maintained under standard culture conditions for further analyses.

2.7. Quantification of Cell Density and Estimate of the Growth Area of MSCs

After culturing for five to seven days, cells adherent to the plastic surface exhibiting fibroblastic morphology were observed and counted according to the minimum criteria established by the International Society for Cell Therapy (ISCT), based on the cell fractions obtained through decantation and centrifugation protocols. This approach allowed for the quantification of mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) density in 1 mL of the total cell fraction. For this analysis, MSCs cultured in 6-well plates were evaluated based on the number of colony-forming units (CFUs) in both decanted and centrifuged bone marrow (BM) fractions. A minimum of 50 cells per colony was required, and the entire well area was analyzed by manual CFU counting under an inverted light microscope at 20x magnification (AXIOVERT, Zeiss, Germany). On day 10, the same 6-well plates used for CFU counting were assessed by measuring the area occupied by MSC growth. The entire well length was photographed using the inverted microscope at 20x magnification, and images were analyzed with ImageJPRO software using the area selection tool within a specified perimeter to quantify MSC growth area in each well.

2.8. Characterization of the Mesenchymal Stem Cells

Utilizing the parameters described by the International Society of Cell Therapy (Dominici, 2012), tests for mesodermal differentiation and flow cytometry will be performed to prove the homogeneity of the MSCs that are being cultured [

18].

2.9. Mesodermal Differentiation

Adipogenic and osteogenic differentiation were induced as described by Phinney

et al., 1999 [

19]. For adipogenic differentiation, the adherent cells were cultured for four weeks in a medium supplemented with 10⁻⁸ mol/L dexamethasone and 5 µg/mL insulin. After differentiation, the cells were fixed in 5% paraformaldehyde for 1 hour at room temperature and subsequently stained with Oil Red O solution (Sigma). For osteogenic differentiation, the adherent cells were cultured for five weeks in a medium containing 10⁻⁸ mol/L dexamethasone, 5 µg/mL ascorbic acid 2-phosphate, and 10 mmol/L glycerol phosphate. The cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 1 hour at room temperature and stained with Alizarin Red solution. Images of the stained cells were captured using a color camera mounted on the AXIOVERT microscope (Zeiss, Germany).

2.10. Flow Cytometry

Flow cytometry was employed to characterize the cell population immediately following the decantation and centrifugation protocols, as well as after the fifth passage of mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) cultures. The samples were incubated for two hours at room temperature with antibodies against CD34, CD45, CD105, and CD117 (for mononuclear cells post-decantation and centrifugation), and CD105, CD90, CD34, and HLA-DR (for MSCs after the fifth passage). After incubation, the cells were washed with DPBS and analyzed by flow cytometry using a FACSCanto cytometer (BD-Becton, Dickinson and Company, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA).

4. Discussion

The use of orthobiologics is gaining increasing interest due to the availability of new promising products to address musculoskeletal and degenerative disorders. Cellular therapies have prompted the development of minimally manipulated cell products focused on the four hallmark characteristics that define stem cells: the abilities to reproduce, differentiate into multiple cell types, mobilize for angiogenesis, and exert paracrine signaling functions (immunomodulatory, anti-inflammatory, and anti-apoptotic signals) that influence the environment of functional tissue regeneration in host cells. In light of this, BMAC is technically straightforward and presents the advantages of overcoming the need for culture expansion, thus reducing the risk of infection and avoiding the risk of allogeneic diseases [

20]. In this sense, the final value of the therapy also has advantages. The decantation protocol techniques are quickly and have manufacturing-costs feasible in academic and small-scale settings, guiding cost-effective planning strategies to guarantees access to therapy without undervaluation of resources.

Previous studies have suggested that MSCs only represent about 0.001% to 0.01% of the cells in bone marrow concentrate, making it uncertain whether processes such as BMAC provide enough viable MSCs to achieve clinical effectiveness [

21].

Conversely, the minimal cell manipulation approach, allowing bone marrow aspirate concentrate to be used directly on-site in a one-step treatment, has been widely utilized in clinical practice for the treatment of cartilage lesions initially and, more recently, has been proposed as a promising injectable approach to treat degenerative conditions [

22,

23]. Since the cellular density of the final product can impact clinical outcomes, it is important to compare systems to ensure equivalence and effectiveness [

24].

Many factors can influence the material collected in a bone marrow aspiration to obtain a stem cell concentrate. Among them, the volume harvested in the aspiration and the access to the iliac crest puncture are directly related to the density and quantity of cells with colony-forming capacity [

25,

26,

27,

28]. While cellular therapy is increasingly popular, its efficacy remains unclear due to variability in the composition of cellular products and lack of consistency among study designs supporting different therapies. In this regard, understanding costs is essential for proper resource allocation and for supporting the development and implementation of cell-based therapies. Recently, Renske

et al., 2020 describe a step-by-step framework has been proposed to help estimate manufacturing costs in academic and small-scale settings, guiding cost-effective planning strategies [

29].

In this study, the procedures related to the bone marrow sample obtained were highly standardized, allowing for a direct comparison between two protocols from the same harvest site, as both protocols (centrifugation and decantation) were applied to all collections. Additionally, these multipotent cells derived from BMAC have been shown to grow exceedingly well in culture. Although limited in sample size (n=10), it was possible to demonstrated that the number of colonies formed was significantly higher in samples from the decantation protocol, suggesting greater viability of MSCs than centrifugation process, which could may harm MSCs into the aspirate20. Furthermore, a larger sample (n > 10) could result in a predictive analysis of the relationship between the cell recovery rate and the density of MSCs present in the aspirate after the decantation protocol. Our work presents clear results regarding the success of obtaining a stem cell concentrate without requiring a centrifugation protocol. Furthermore, the decantation methodology can be all performed, step-by-step, in a sterile surgical field, reducing the risk of contamination.

Surgical site infection is defined as contamination at the primary surgical site or at a site adjacent to the incision [

30]. In the United States, infections occur in 0.5% to 3% of patients undergoing surgical procedures, accounting for an annual healthcare cost of

$3.5 billion to

$10 billion [

31]. Moreover, surgical site infection depends on factors related to exposure to bacterial contamination and the host's ability to control inherent contamination of the incision. These factors can be stratified by patient-related factors (such as diabetes, immunosuppression, malnutrition, obesity, tobacco use) or independent factors (such as airborne contamination, procedure time, surgical technique, contamination of the incision by microbiota or those involved in the procedure, wound care) [

32]. All strategies that minimize the risk of contamination during a surgical procedure have an extremely relevant impact on safe clinical translation. Here, we present an efficient and promising protocol for obtaining bone marrow stem cell concentrates during surgery without the need for centrifugation or the use of devices. We equate the decantation method to standard protocols through quantifiable parameters of cell recovery and expected behavior for mesenchymal stem cells.

In healthcare settings where resources are limited, choosing the optimal treatment requires considering not only the efficacy of the treatment itself but also its cost-effectiveness [

33]. From clinical efficacy to the careful analysis of cost-effectiveness, the public healthcare system deals with limited budgets. The decision between offering a high-cost innovative treatment protocol or a more affordable conventional treatment must consider not only the therapeutic benefits but also the financial impact on the healthcare system and the number of patients that can be treated. At this point, we emphasize that the technical protocol described prioritizes interventions that provide the most significant benefit to the population at a sustainable cost, which can be essential to maximize the reach and effectiveness of public health actions and to disseminated MSCs-based therapies.

Piuzzi et al. conducted a systematic review of 46 clinical trials, analyzing the preparation technique and use of BMAC, and demonstrated disparities in its preparation and application. No definitive protocol could be derived from these 46 clinical trials. When evaluating the protocols in these trials, only 30% provided quantitative metrics of BMAC composition. Similarly, Murray et al. conducted a systematic review of 48 studies and identified deficiencies in the preparation protocol and the composition of BMAC. None of the 48 studies provided an adequate technique or protocol to standardize BMAC formulations. Therefore, there is a gap in the literature regarding a standardized method for harvesting and processing BMAC to achieve optimal outcomes [

34].

Recent studies have reported the aspiration of 30 to 120 mL of BMA to prepare 10 to 12 mL of BMAC for clinical applications. Several studies have demonstrated excellent clinical and functional outcomes with single or multiple doses of BMAC ranging from 4 to 12 mL per knee for cartilage regeneration. A single dose of 8 mL of BMAC has shown superior clinical outcomes compared to PRP and autologous conditioned serum in patients with knee OA. However, it has now been established that the volume of administration is not what matters but rather the count of active cellular components in the delivery vehicle, significantly influencing the perceived outcome [

34].

A point that should be highlighted is that although studies have reported clinical benefits from using devices/systems to separate a BMA fraction, little is known about the composition of the cell concentrate being reinjected into patients. The study group of Gangji et al. described that after concentrating 400 ml of BMA from the iliac crest to a mean volume of 51 ± 1.8 ml, the reinserted concentrate contained 2.0 ± 0.3 × 10⁹ leukocytes and 92 ± 9/10

7 units forming fibroblast colonies. The mononuclear cells within their cell product contained approximately 29% lymphoid cells, 4% monocytoid cells, and 6% myeloid cells. According to the systematic review by Robinson

et al., 2019, all existing clinical studies assessing MSCs for orthopedic or sports medicine applications are limited by inadequate reporting of preparation protocols and composition [

35].

Considering the data available in literature and similar studies and comparing them to our results, we recognize certain limitations in our study. Firstly, the sample size of only 10 patients does not account for the heterogeneity influenced by factors such as age, health condition, and medication use, all of which can affect the quality and concentration of MSCs in the final BMAC product. Additionally, we observed variations in the final BMAC volumes for each protocol. Since this is a manufactured methodology, operational inconsistencies are possible. Furthermore, it may seem contradictory that a smaller aspiration volume could yield a higher MSC concentration than a larger aspiration volume, highlighting the complexity of the process and the need for further investigation.

To better understand the variability in cell composition, this research achieved the quality and quantity of stem cells in BMC using two different protocols with potential clinical applications, particularly in a closed system for intraoperative use. The lack of standardized protocols is widely recognized in the medical literature, as no universally accepted method exists for preparing and applying BMC, resulting in inconsistencies in efficacy across studies and dubious clinical applications.

Although the limited expansion potential differs from that of cultured MSCs, both the decanted and centrifuged protocols have provided valuable insights into the content of BMAC as minimally manipulated autologous cells, thereby supporting advancements in its clinical application. Nonetheless, the use of BMC remains within a regulatory gray area in several countries. The limitations identified and the insights gained from this study underscore the significance of our findings in advancing processing techniques and establishing standardized clinical protocols. These advancements are critical for improving the efficacy of BMC therapies in clinical practice. Building on these findings, our research group is currently conducting a new clinical study (CAAE 86730225.7.0000.5341; approval number: 7.466.709) to further validate the safety and regenerative potential of our bone marrow aspirate concentrate produced by the decantation protocol described.