1. Introduction

Large language models (LLMs) have recently improved their logical reasoning capacities, notably via Chain-of-Thought (CoT) techniques [

1]. By making intermediate reasoning steps explicit, these methods substantially improve performance on datasets such as ProofWriter [

2] or FOLIO [

3]. However, LLM reasoning remains fundamentally opaque, unverifiable, and subject to the vagaries of natural language: lexical inconsistencies, implicit inferences, and lack of guaranteed logical correctness [

4].

To address these limitations, several neuro-symbolic approaches have combined the linguistic power of LLMs with the formal rigor of logic solvers. Systems such as Logic-LM [

5] or LINC [

6] translate LLM-produced reasoning into logical representations that can be executed by a first-order deduction engine. These models reach strong results but remain dependent on the quality of the LLM’s internal logical translation, which is neither controlled nor interpretable and whose errors are difficult to diagnose.

In this context, we propose eXa-LM, a controlled natural language (CNL) interface between LLMs and first-order logic solvers [

7]. Our method aims to establish an explicit and verifiable bridge between the linguistic reformulation of a text and its executable logical representation. It relies on three main components:

- a reformulation prompt designed for the LLM to convert text into a set of facts and rules expressed in a formally defined CNL; - the semantic analyzer eXaSem that turns this CNL into a SWI-Prolog program composed of extended Horn clauses (including contraposition, xor connectors, negative facts and conclusions); - the logic meta-interpreter eXaLog capable of executing the program while integrating second-order reasoning (ontological inheritance).

This approach has three main advantages:

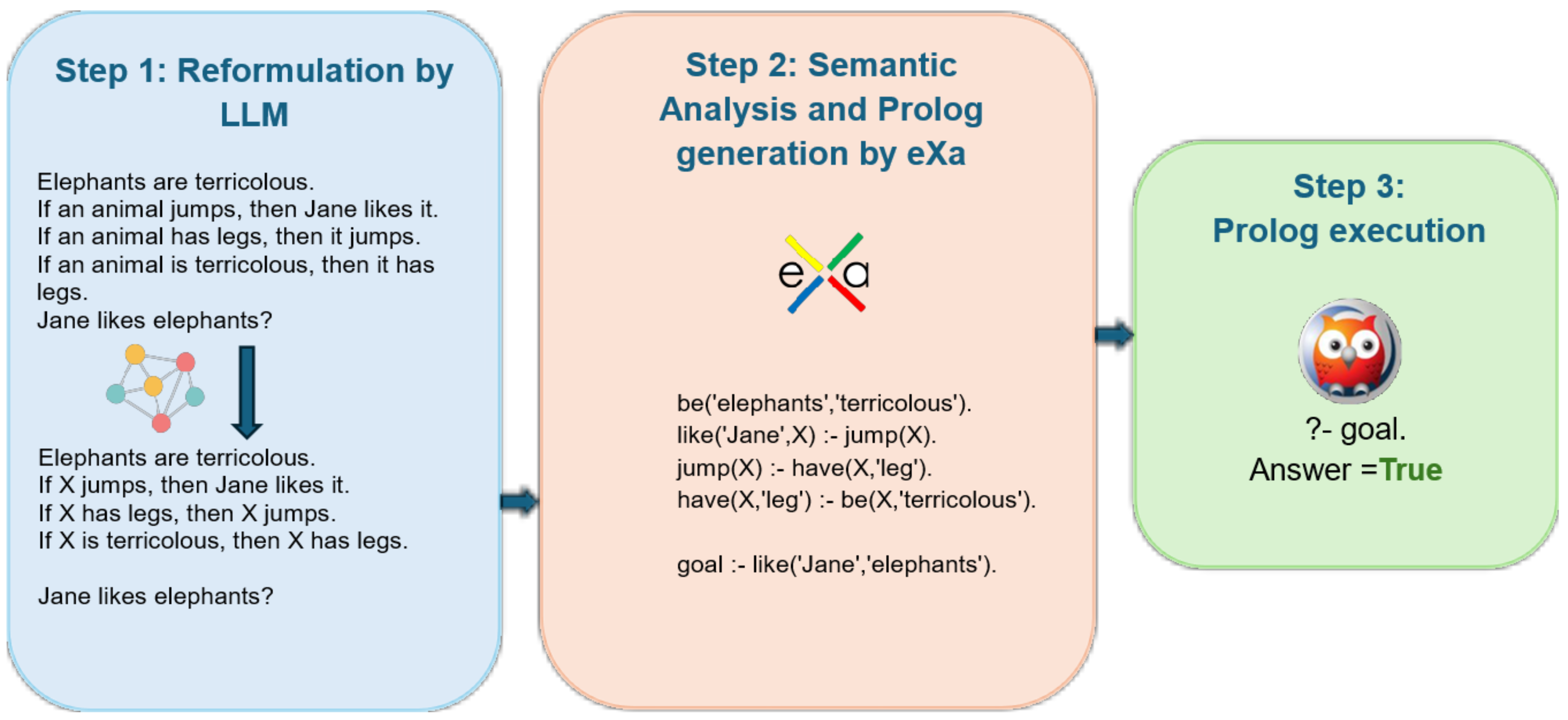

Figure 1.

Schematic of the general principle of our method. Step 1: the problem text is submitted to an LLM with a reformulation prompt that converts it into elementary facts and rules. Step 2: eXa analyzes the reformulated text and turns it into an interpretable Prolog program. Step 3: SWI-Prolog executes the program and returns the answer, which is finally formatted and presented by eXa.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the general principle of our method. Step 1: the problem text is submitted to an LLM with a reformulation prompt that converts it into elementary facts and rules. Step 2: eXa analyzes the reformulated text and turns it into an interpretable Prolog program. Step 3: SWI-Prolog executes the program and returns the answer, which is finally formatted and presented by eXa.

1. It guarantees a clear separation between linguistic processing and logical reasoning, allowing traceability and justification of every inference. 2. It provides full control over the syntax and semantics of admissible sentences, reducing reformulation and translation errors. 3. It enables direct and reproducible evaluation of system performance independent of the language model used.

We evaluate eXa-LM on three reference sets—PrOntoQA [

8], ProofWriter and FOLIO—comparing it with GPT-4 [

9], GPT-4o [

10], Logic-LM and LINC. Our results show that this approach, while more explainable and modular, reaches or exceeds the performance of recent neuro-symbolic systems.

2. Related Work

Logical reasoning from text approaches can be categorized into three families: (1) purely linguistic methods, (2) approaches based on large language models, and (3) neuro-symbolic or neuro-symbolic methods combining both paradigms.

1. Logical reasoning from text

Early work aimed to directly link first-order logic with explicit linguistic representations. Controlled Natural Languages (CNLs) such as Attempto Controlled English [

11] or PENG [

7] have shown that a subset of natural language can be formalized unambiguously to be interpreted by a logic engine. These works inspired many symbolic translation systems [

12] but their linguistic coverage was limited and expressivity rigid. In NLP, efforts were made to extract logical representations from complex sentences via semantic parsing [

13], but these translations remained dependent on costly supervised models and were hard to generalize.

2. Logical reasoning by large language models

The emergence of LLMs changed how logical reasoning is approached. Works such as Chain-of-Thought or Zero-shot CoT [

14] showed that LLMs can produce explicit reasoning chains that improve accuracy on deductive tasks. However, these methods rely on informal linguistic reasoning not verifiable by a logic engine. Recent studies have systematically measured these capabilities. PrOntoQA [

8], ProofWriter [

2] and FOLIO [

3] are now primary benchmarks. These datasets show that LLMs, while strong at surface reasoning, fail frequently when multiple inference steps or complex logical connectives are involved [

4].

3. Neuro-symbolic approaches

To overcome these limits, several works have integrated first-order logic engines into LLM reasoning loops. Logic-LM [

5] combines a generative language model with several logic solvers depending on the task. Although effective on ProofWriter and FOLIO, the system remains dependent on the LLM’s implicit translation and relies on iterative self-refinement calls to the LLM. LINC [

6] follows a similar path but uses a majority-vote mechanism to improve translation reliability, at the cost of multiple model calls. VANESSA [

15] proposes translation by successive rewritings toward an intermediate representation less structured than predicate logic to verify reasoning chains of small language models (SLMs).

4. Specificity of eXa-LM

eXa-LM stands out by introducing a controlled natural language (CNL) as the pivot between the language model and the logic solver. Unlike Logic-LM or LINC, the passage from text to first-order logic is not implicitly delegated to the LLM but is specified formally through a reformulation prompt based on precise syntactic and semantic rules. This ensures traceability, reproducibility and verifiability of the logical representation while allowing fine-grained control over the admissible sentence grammar.

Finally, eXa-LM uses the same semantic analyzer and logic engine for all reasoning types; the logic engine is based on an extensible Prolog meta-interpreter for new tasks.

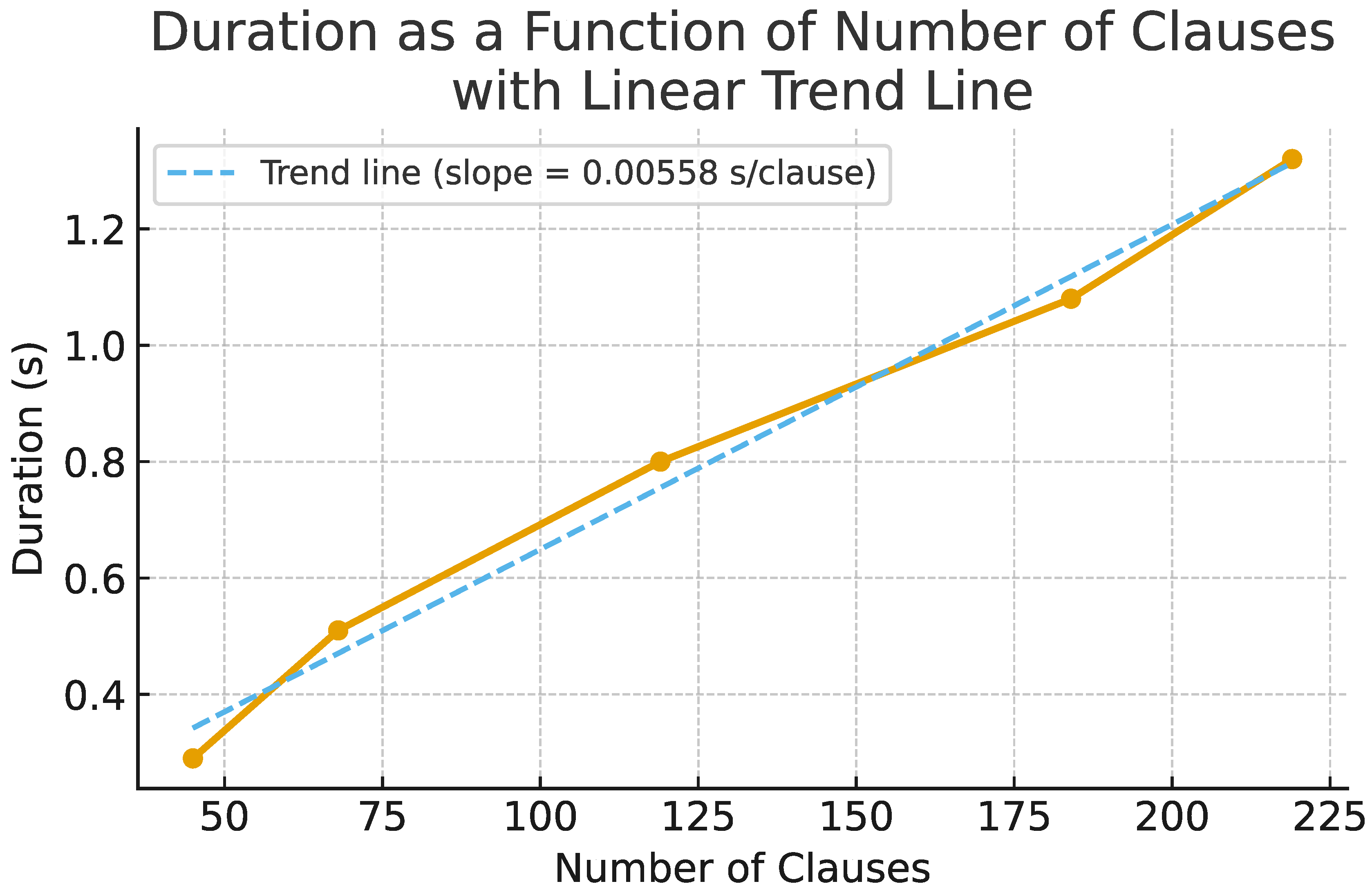

3. Reformulation Prompt

The reformulation prompt, provided in the Appendix, is a sequence of instructions that allows the LLM used (GPT-4o, version 2025-03-26) to convert the submitted text (in one of the LLM-supported languages) into a base of facts and rules accompanied by a question, all written in a Controlled Natural Language (CNL) analyzable by eXa.

Main syntactic and semantic restrictions are:

- Text in French

1, no synonyms, no ambiguous coreferences, elementary sentences (i.e., with a single non-auxiliary verb), optionally connected by "and", "or", "xor" (exclusive or).

- Rules in assertions must have the form: "If <conditions> then <conclusions1> [else <conclusions2>]".

Where:

<conditions> ::= <elementary_sentence 1> [{ and | or | xor <elementary_sentence i> }] <conclusions> ::= <elementary_sentence 1> [{ and | xor <elementary_sentence i> }]

Assertions and questions are treated by two distinct sections of the prompt with slightly different constraints. In particular, questions that are rules whose conclusion contains "or" or "and" must be reformulated using , preserving parentheses and distributing negation to the innermost level when needed.

The prompt also contains semantic transformation instructions (II.6, II.11, II.12, II.14). The main of these instructions is:

"II.6 - Replace the subject of each rule "If ... then ..." and of each fact containing a xor by "X" only when it denotes a general category, while preserving the exact structure of the rule."

For example: "If people order takeout frequently in college, then they work in student jobs on campus" will be reformulated to: "If X order takeout frequently in college, then X work in student jobs on campus"

Some syntactic reformulation instructions may later be removed from the prompt and delegated to eXa, reducing the LLM’s computational burden.

4. eXa

eXa is a program that takes as input a controlled French text (according to the constraints above) composed of assertions and questions, converts it into an executable SWI-Prolog program [

16], and outputs answers to questions optionally accompanied by justification traces of the derivation.

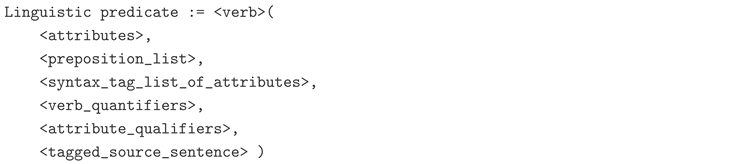

4.1. eXaSem

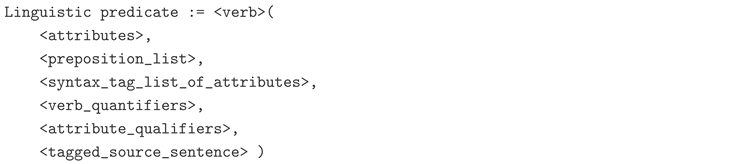

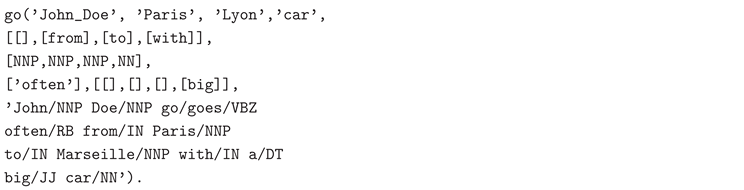

This module applies a complex chain of linguistic processing to the input text, as described in Figure . eXaSem produces a unified representation we call "linguistic predicates", defined as:

Example: "John Doe goes often from Paris to Marseille with a big car."

Produces the linguistic predicate:

Note: the tagged source sentence associated with the linguistic predicate is used by the eXaGen module.

Figure 2.

Full processing chain executed by module eXaSem: lemmatization and POS tagging, partial disambiguation, segmentation, resolution of simple coreferences (grammatical anaphora), construction of linguistic predicates and rule construction. Transformations at each step are highlighted in yellow in the original figure. (1) Uses the tagged French lexicon from [17] (2) [18]

Figure 2.

Full processing chain executed by module eXaSem: lemmatization and POS tagging, partial disambiguation, segmentation, resolution of simple coreferences (grammatical anaphora), construction of linguistic predicates and rule construction. Transformations at each step are highlighted in yellow in the original figure. (1) Uses the tagged French lexicon from [17] (2) [18]

4.2. eXaLog

eXaLog: Translator to first-order logic (FOL) with "xor" connector into extended Horn clauses, Prolog meta-interpreter and execution environment for Prolog programs.

The meta-interpreter enables: - Tracing of reasoning to produce explanations. - Interpreting negative facts and rules with negation in conclusions (extension of Horn clauses) to handle the "xor" connector, while remaining in a closed-world assumption (CWA).

Because Prolog only accepts Horn clauses, eXaLog first translates assertions into extended Horn structures (with negation).

Example transformations :

Table 1.

List of transformations performed by eXaLog on assertions.

Table 1.

List of transformations performed by eXaLog on assertions.

| Original rule |

Transformed form(s) |

| If

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

Contrapositive rules are also added when possible to implement modus tollens, which is not native to Prolog.

This module also supports hypothetical reasoning, i.e., questions posed as rules without transforming them into logical formulas. In particular, when all assertions are rules (no facts), Prolog cannot natively produce an answer regardless of the question form.

Example: If Jean likes strawberries then he buys them. If Jean buys strawberries then he eats them. Question: If Jean likes strawberries, then does he eat them?

4.3. eXaMeta

eXaMeta: Second-order rule meta-interpreter.

This module enriches reasoning by interpreting second-order rules—rules where at least one predicate is a variable. For example, it handles inheritance of properties via ontological relations like "is_a" in syllogistic reasoning.

Example of a metarule:

Where R0 is a predicate variable.

Applied to:

’Socrates is a man. Men are mortal." this metarule allows deducing "Socrates is mortal" by instantiating:

X=Socrates, Y=man, Z=mortal, R0=be, without reformulating "Men are mortal" as a specific rule.

4.4. eXaGen

eXaGen: Generation of natural language answers and explanations.

This module generates human-readable explanations of the deduction chain leading to an answer.

Example:

A Twingo is a car. The Twingo does not go fast. If a car does not go fast then it drives slowly.

Q: How does a Twingo drive? A: slowly.

Q: Why? A: Because the Twingo does not go fast, a Twingo is a car, and if a car does not go fast then it drives slowly.

4.5. eXaGol

eXaGol: Relational learning [19] from texts to generate hypotheses as new rules. Not used in this study, so not detailed here.

5. Experiments

We evaluate eXa-LM on three datasets commonly used for deductive reasoning from text: PrOntoQA, ProofWriter and FOLIO, and compare it to GPT-4 and GPT-4o, LINC and Logic-LM.

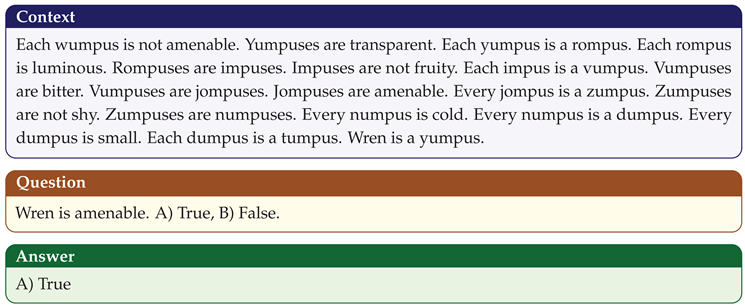

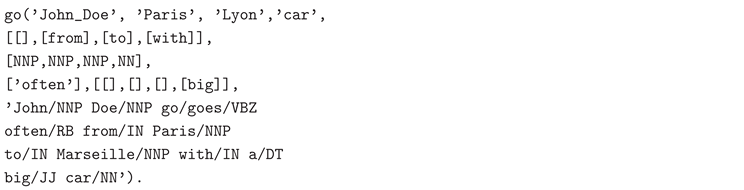

PrOntoQA [

8] is a synthetic dataset to evaluate LLM deductive abilities. We use the same subset as Logic-LM (the hardest, depth 5), containing 500 tests. PrOntoQA only contains "is" and "is a" relations. Example:

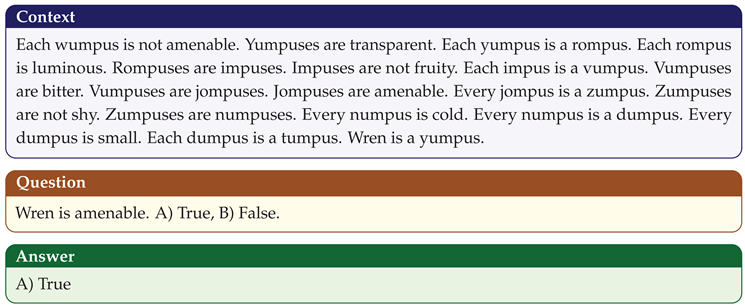

ProofWriter [

2] is another frequently used deductive reasoning dataset, somewhat more varied and complex than PrOntoQA. It consists of a set of simple facts and rules. We use the same random sample of 600 examples (depth 5) as Logic-LM. As eXa currently operates under closed-world assumption (CWA), we convert Unknown answers to False. Example:

FOLIO [

3] is a set of linguistically and logically complex texts, written by experts and inspired by real-world knowledge. Resolving questions requires complex first-order logical reasoning. We use the same FOLIO test set as LINC and Logic-LM: 204 examples minus 22 errata reported by LINC authors, i.e., 182 examples. As for ProofWriter, we map Unknown to False for CWA.

Example:

We compare eXa-LM results to four references: - Two LLMs: GPT-4 and GPT-4o, each in two modes: (1) Standard: "Answer yes or no, using only the provided data"; (2) Chain-of-Thought (CoT): "Answer yes or no, using only the provided data, after decomposing the reasoning step-by-step." - Two neuro-symbolic systems: LINC and Logic-LM, representing the state of the art in combining LLMs and logic solvers.

6. Results and Discussion

For PrOntoQA and ProofWriter, GPT-4o was only used to translate texts into French; eXa’s semantic analyzer can interpret the texts directly without further transformation. The perfect (100%) results for these two datasets are therefore unsurprising, since the tasks reduce to controlled semantic translation rather than complex generation.

Table 2.

Exact-match accuracy percentages obtained with LLMs alone (Standard and CoT), with LINC, Logic-LM, and eXa (our method), without (1) and with (2) GPT-4o prompting. The best results are shown in bold green, the second-best ones in bold black.

Table 2.

Exact-match accuracy percentages obtained with LLMs alone (Standard and CoT), with LINC, Logic-LM, and eXa (our method), without (1) and with (2) GPT-4o prompting. The best results are shown in bold green, the second-best ones in bold black.

| Dataset |

GPT-4 (*) |

GPT-4o |

| |

Std. |

CoT |

LINC |

Logic-LM |

Std. |

CoT |

eXa (ours) |

| PrOntoQA |

77.40 |

98.79 |

– |

83.20 |

85.45 |

99.80 |

100.00 (1) |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

(+0.20) |

| ProofWriter |

52.67 |

68.11 |

98.30 |

79.66 |

65.71 |

74.29 |

100.00 (1) |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

(+1.70) |

| FOLIO |

69.11 |

70.58 |

72.50 |

78.92 |

79.78 |

91.85 |

92.90 (2) |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

(+1.05) |

For FOLIO, we used a 20-step reformulation prompt (see Appendix) with in-context examples. GPT-4o reliably followed the instructions, producing outputs conforming to the CNL in a single pass in all but one case.

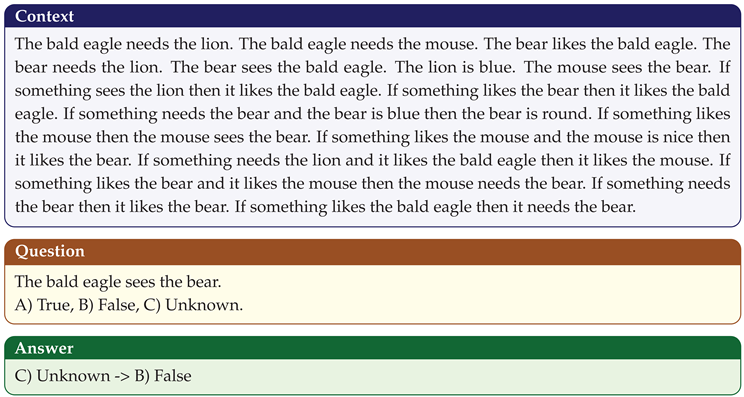

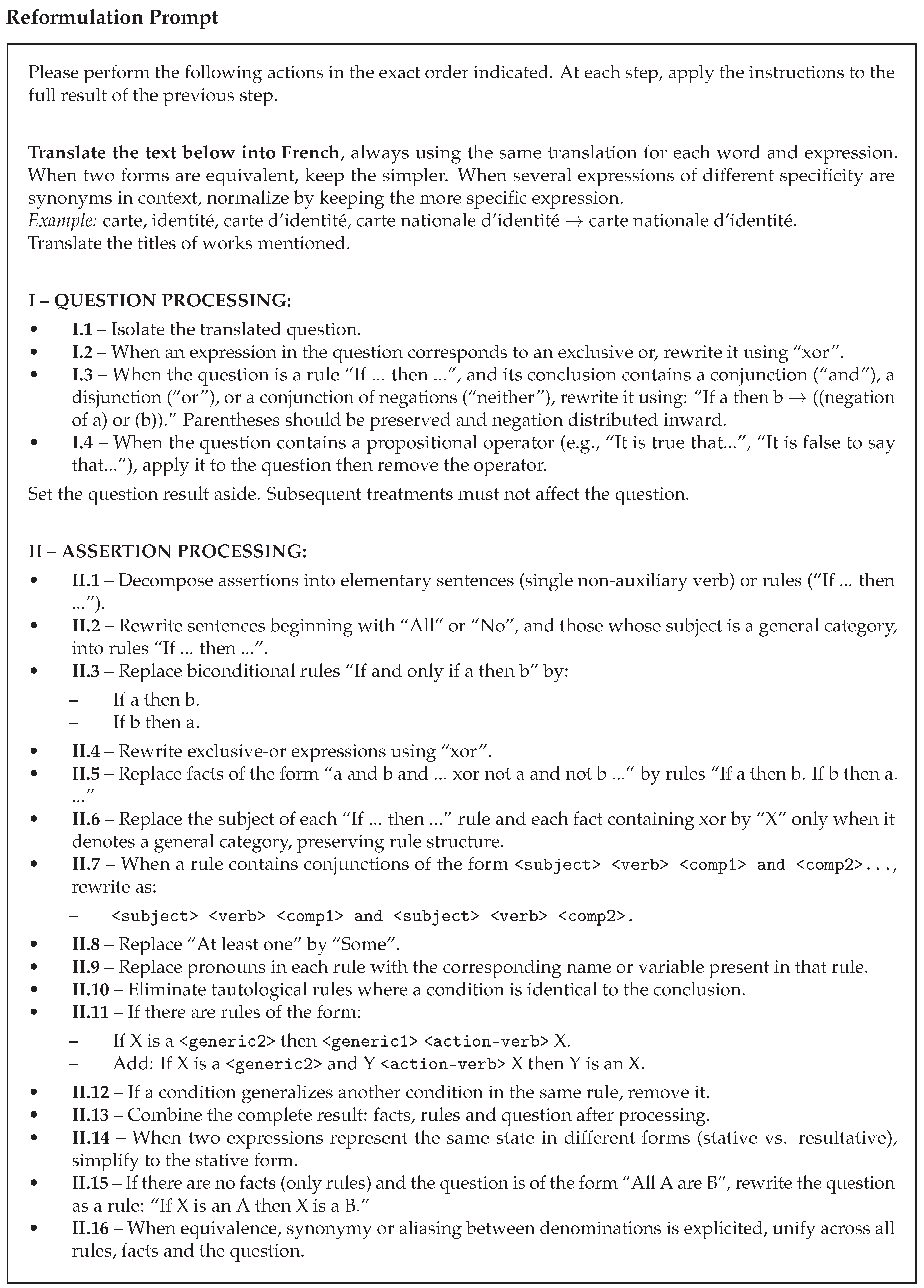

eXa-LM outperforms GPT-4o CoT by 1.05 points on FOLIO, which is not statistically significant (McNemar test: p = 0.84). Comparing gains over CoT across systems on FOLIO: LINC +1.92, Logic-LM +8.34, eXa-LM +1.05.

This is partly due to the notable improvement in CoT reasoning capacity between GPT-4 and GPT-4o on FOLIO (+21.27 points), more than double the progress in Standard mode (+10.3). Another factor is eXa-LM limitations discussed below.

7. Impact of Closed-World Conversion (CWA)

Converting OWA to CWA maps ternary labels (True/False/Unknown) to binary (True/False). A random baseline accuracy rises from 1/3 to 1/2 under this mapping. We computed expected adjustments and found small differences (ProofWriter: negligible, FOLIO: 0.0118 absolute difference).

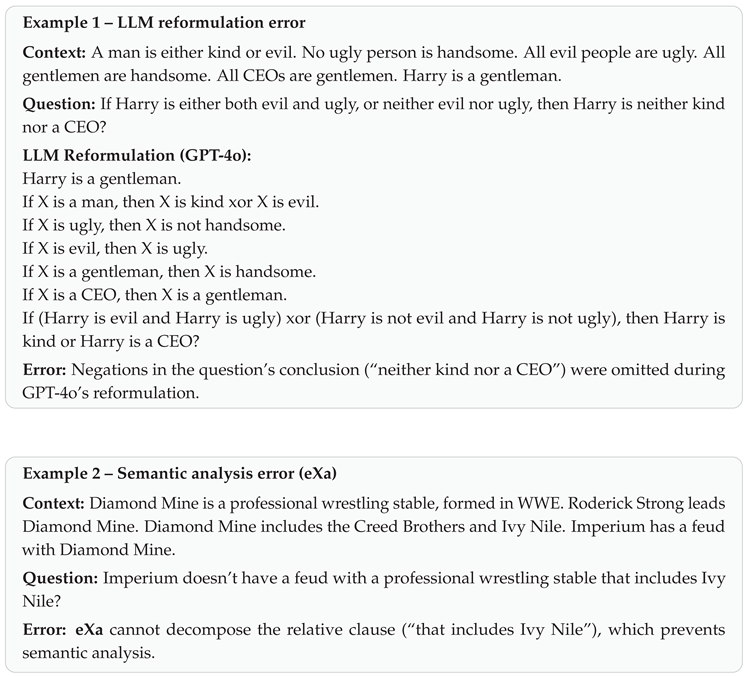

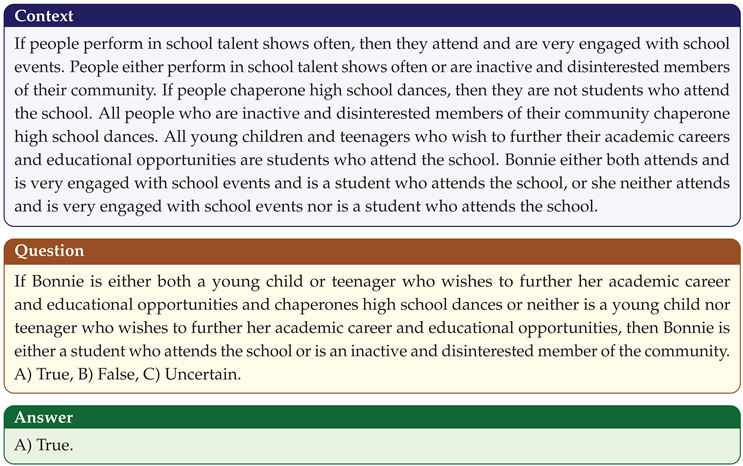

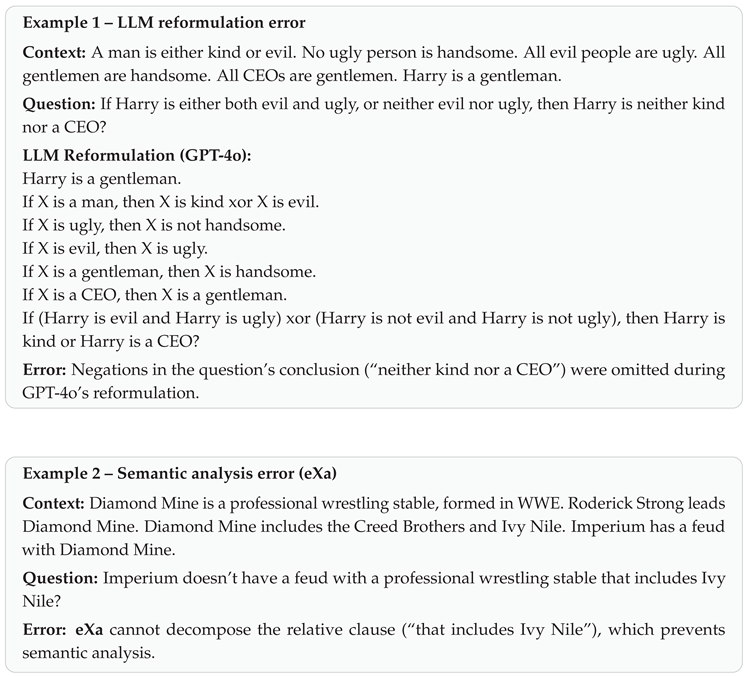

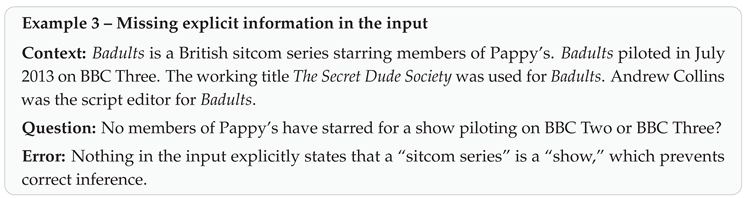

8. Error Analysis

We attribute the low number of LLM reformulation errors to improved instruction following. Semantic-analysis errors can be reduced by extending grammar and parser coverage. The largest category involves missing explicit information in the initial text: eXa-LM cannot rely on implicit world knowledge the LLM might otherwise introduce.

Table 3.

Summarizes the errors and their sources.

Table 3.

Summarizes the errors and their sources.

| Error Source |

Count |

| LLM reformulation |

1 |

| eXa semantic analysis |

5 |

| Missing explicit information in input |

8 |

| Total |

13 |

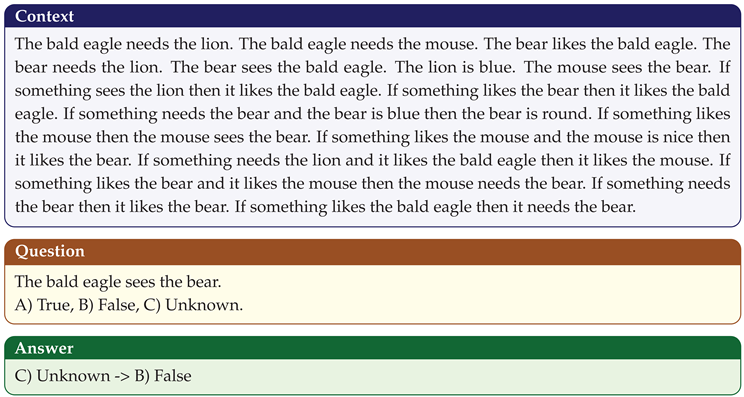

Figure 3.

Confusion matrix comparing GPT-4o CoT and eXa-LM on FOLIO. Darker blue indicates higher agreement counts.

Figure 3.

Confusion matrix comparing GPT-4o CoT and eXa-LM on FOLIO. Darker blue indicates higher agreement counts.

To better understand failure modes, we manually analyzed the 13 errors across the FOLIO dataset. Examples illustrating each category are presented below.

9. Ablation Study

We ablate eXa by replacing eXaLog, the logical module, with the reformulation followed by GPT-4o CoT. Results are shown in

Table 4.

Table 4.

Ablation study. Contribution of eXa-LM is +2.14 points compared to GPT-4o CoT (McNemar ).

Table 4.

Ablation study. Contribution of eXa-LM is +2.14 points compared to GPT-4o CoT (McNemar ).

| Model / Setting |

Accuracy (%) |

| GPT-4o CoT (baseline) |

91.85 |

| Reformulation + GPT-4o CoT |

| (ablation) |

90.76 |

| eXa-LM (ours) |

92.90 |

10. Independence of the LLM

We chose GPT-4o for the reformulation prompt because it gave the best results. The prompt was also tested with Mistral-Large2 [20] with 81.3% accuracy (vs. 92.90% for GPT-4o). The difference is mainly due to Mistral’s difficulty in consistently executing the abstraction instruction (II.6).

11. Computational Costs

Execution costs of eXa-LM decompose into: (1) cost of reformulation prompt execution by GPT-4o, and (2) cost of running eXa on a standard CPU (Intel i9-185H).

Table 5.

Average eXa-LM execution time per task (in seconds).

Table 5.

Average eXa-LM execution time per task (in seconds).

| Dataset |

Average execution time (s) |

| PrOntoQA |

0.21 |

| ProofWriter |

0.27 |

| FOLIO |

0.21 |

Table 6.

Token consumption and average execution time for the FOLIO reformulation prompt.

Table 6.

Token consumption and average execution time for the FOLIO reformulation prompt.

| Metric |

GPT-4o CoT |

eXa-LM |

| Prompt + Task tokens |

350 |

1,100 |

| Output tokens |

850 |

1,200 |

| Total tokens |

1,200 |

2,300 |

| Execution time (s) |

∼3 |

∼5 |

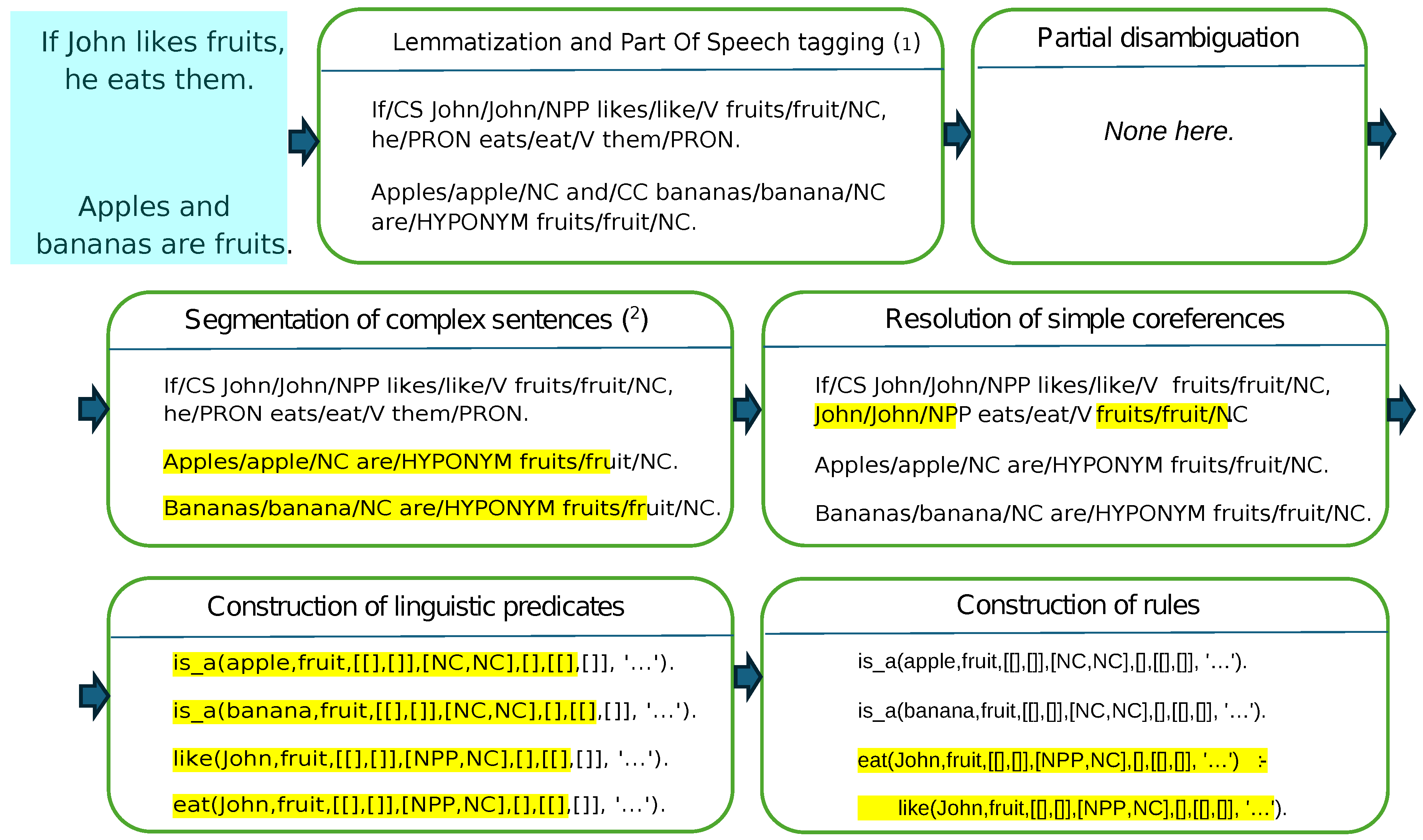

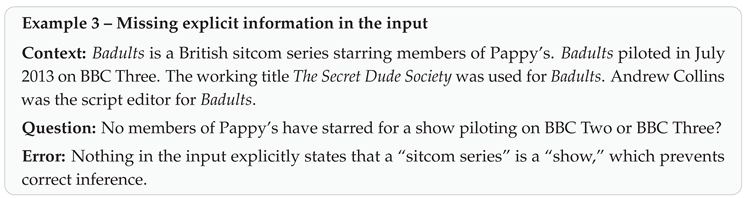

12. Scalability

Qualitatively, scalability concerns extending task variety and grammar coverage. Quantitatively, scalability depends on LLM response time for reformulation and eXa execution time. We measured eXa execution time as a function of number of generated Prolog clauses: execution time grows approximately linearly at 0.005583 s per clause (R⌃

).

Figure 3 illustrates this relation.

Figure 4.

Execution time of eXa-LM as a function of the number of generated Prolog clauses. The relationship is approximately linear (), with an average slope of 0.005583 s per clause.

Figure 4.

Execution time of eXa-LM as a function of the number of generated Prolog clauses. The relationship is approximately linear (), with an average slope of 0.005583 s per clause.

13. Limitations and Future Work

Limited linguistic coverage and expressivity. The CNL grammar is deliberately narrow, excluding nested relatives and complex passives; linguistic predicates do not encode tense or grammatical gender. Future work: Extend grammar via semi-supervised learning and enrich predicates.

Absence of abductive and inductive reasoning. eXa-LM implements deduction and some hypothetical reasoning; abduction is not implemented and induction is present but unused. Future work: Leverage eXaGOL for rule induction and implement abduction.

Limits of logical representation. eXaLog extends Prolog but does not cover full FOL (nested quantifiers, multiple quantifier scopes). Future work: Support richer FOL constructs and partial skolemization strategies.

Closed-world assumption (CWA). Simplifies reasoning but limits inference in partially known contexts. Future work: Study mixed CWA/OWA variants.

Extraction of implicit knowledge from LLMs. Some FOLIO errors stem from missing intermediate relations. Future work: Design prompting methods to surface missing intermediate relations.

Robustness evaluation. Current evaluation uses inference-focused datasets. Future work: Test on broader QA datasets (SQuAD [21], Natural Questions [22], BoolQ [23], DROP [24], HotpotQA [25])

Portability and multilingualism. eXa is French-first. Future work: Implement a native English CNL and assess transferability.

14. Conclusion

We introduced eXa-LM, a controlled natural language bridge between LLMs and first-order logic solvers ensuring traceability and explainability while remaining competitive with recent neuro-symbolic systems. Constraining LLM outputs to a CNL and executing them via a symbolic pipeline yields competitive performance and full auditability of deductions. eXa-LM highlights the feasibility of a transparent neuro-symbolic architecture where linguistic processing and logical reasoning are explicitly separated and controllable.

Institutional Review Board Statement

We discuss energy costs associated with large models [26] and note that our experiments use in-context learning rather than model training, limiting carbon footprint relative to full retraining. No sensitive personal data were used. LLMs were used only for translation and minor stylistic edits; all scientific contributions come from the authors.

References

- Wei, J.; Wang, X.; Schuurmans, D.; Bosma, M.; Ichter, B.; Xia, F.; Chi, E.H.; Le, Q.V.; Zhou, D. Chain-of-thought prompting elicits reasoning in large language models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Red Hook, NY, USA, 2022; NIPS ’22. [Google Scholar]

- Tafjord, O.; Dalvi, B.; Clark, P. ProofWriter: Generating Implications, Proofs, and Abductive Statements over Natural Language. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL-IJCNLP 2021; Online, Zong, C., Xia, F., Li, W., Navigli, R., Eds.; 2021; pp. 3621–3634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Schoelkopf, H.; Zhao, Y.; Qi, Z.; Riddell, M.; Zhou, W.; Coady, J.; Peng, D.; Qiao, Y.; Benson, L.; et al. FOLIO: Natural Language Reasoning with First-Order Logic. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2024 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; Miami, Florida, USA, Al-Onaizan, Y., Bansal, M., Chen, Y.N., Eds.; 2024; pp. 22017–22031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valmeekam, K.; Sreedharan, S.; Kambhampati, S. Can LLMs Really Reason and Plan? In Proceedings of the Proceedings of AAAI 2023, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, L.; Albalak, A.; Wang, X.; Wang, W. Logic-LM: Empowering Large Language Models with Symbolic Solvers for Faithful Logical Reasoning. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2023; Bouamor, H., Pino, J., Bali, K., Eds.; Singapore, 2023; pp. 3806–3824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olausson, T.; Gu, A.; Lipkin, B.; Zhang, C.; Solar-Lezama, A.; Tenenbaum, J.; Levy, R. LINC: A Neurosymbolic Approach for Logical Reasoning by Combining Language Models with First-Order Logic Provers. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; Singapore, Bouamor, H., Pino, J., Bali, K., Eds.; 2023; pp. 5153–5176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwitter, R. Controlled natural languages for knowledge representation. In Proceedings of the Coling 2010: Posters, 2010; pp. 1113–1121. [Google Scholar]

- Saparov, A.; He, H. Language Models Are Greedy Reasoners: A Systematic Formal Analysis of Chain-of-Thought. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2210.01240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenAI, *!!! REPLACE !!!*. GPT-4 Technical Report. 2023, 2303.08774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenAI. GPT-4o System Card. 2024, 2410.21276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, N.; Kaljurand, K.; Kuhn, T. Attempto Controlled English for Knowledge Representation. Proceedings of the Reasoning Web 2008, Lecture Notes in Computer Science 2008, Vol. 5224, 104–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, T. A Survey and Classification of Controlled Natural Languages. Computational Linguistics 2014, 40, 121–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Lapata, M. Coarse-to-Fine Decoding for Neural Semantic Parsing. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 56th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics; Melbourne, Australia, Gurevych, I., Miyao, Y., Eds.; 2018; Volume 1, pp. 731–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojima, T.; Gu, S.S.; Reid, M.; Matsuo, Y.; Iwasawa, Y. Large language models are zero-shot reasoners. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Red Hook, NY, USA, 2022; NIPS ’22. [Google Scholar]

- Sadeddine, Z.; Suchanek, F.M. Verifying the Steps of Deductive Reasoning Chains. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2025; Che, W., Nabende, J., Shutova, E., Pilehvar, M.T., Eds.; Vienna, Austria, 2025; pp. 456–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wielemaker, J.; Schrijvers, T.; Triska, M.; Lager, T. Swi-prolog. Theory Pract. Log. Program. 2012, 12, 67–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrupala, G.; Dinu, G.; van Genabith, J. Learning Morphology with Morfette. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC’08); Marrakech, Morocco, Calzolari, N., Choukri, K., Maegaard, B., Mariani, J., Odijk, J., Piperidis, S., Tapias, D., Eds.; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Feneyrol, C. La segmentation automatique de la phrase dans le cadre de l’analyse du français. In Proceedings of the Actes du Congrès international informatique et sciences humaines – L.A.S.L.A., Université de Liège, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Muggleton, S. Inductive logic programming. New Gen. Comput. 1991, 8, 295–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mistral, AI. Mistral Large 2 (v24.07); Paris, France, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Rajpurkar, P.; Zhang, J.; Lopyrev, K.; Liang, P. SQuAD: 100,000+ Questions for Machine Comprehension of Text. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2016 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; Austin, Texas, Su, J., Duh, K., Carreras, X., Eds.; 2016; pp. 2383–2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwiatkowski, T.; Palomaki, J.; Redfield, O.; Collins, M.; Parikh, A.; Alberti, C.; Epstein, D.; Polosukhin, I.; Devlin, J.; Lee, K.; et al. Natural Questions: A Benchmark for Question Answering Research. Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics 2019, 7, 452–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, C.; Lee, K.; Chang, M.W.; Kwiatkowski, T.; Collins, M.; Toutanova, K. BoolQ: Exploring the Surprising Difficulty of Natural Yes/No Questions. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies; Minneapolis, Minnesota, Burstein, J., Doran, C., Solorio, T., Eds.; 2019; Volume 1, pp. 2924–2936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dua, D.; Wang, Y.; Dasigi, P.; Stanovsky, G.; Singh, S.; Gardner, M. DROP: A Reading Comprehension Benchmark Requiring Discrete Reasoning Over Paragraphs. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies; Minneapolis, Minnesota, Burstein, J., Doran, C., Solorio, T., Eds.; 2019; Volume 1, pp. 2368–2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Qi, P.; Zhang, S.; Bengio, Y.; Cohen, W.; Salakhutdinov, R.; Manning, C.D. HotpotQA: A Dataset for Diverse, Explainable Multi-hop Question Answering. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; Brussels, Belgium, Riloff, E., Chiang, D., Hockenmaier, J., Tsujii, J., Eds.; 2018; pp. 2369–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strubell, E.; Ganesh, A.; McCallum, A. Energy and Policy Considerations for Modern Deep Learning Research. 2020, Vol. 34, 13693–13696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Notes

| 1 |

eXa is a monolingual system originally designed for French. All examples in this paper have been translated into English for ease of understanding. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).