Submitted:

18 December 2025

Posted:

22 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

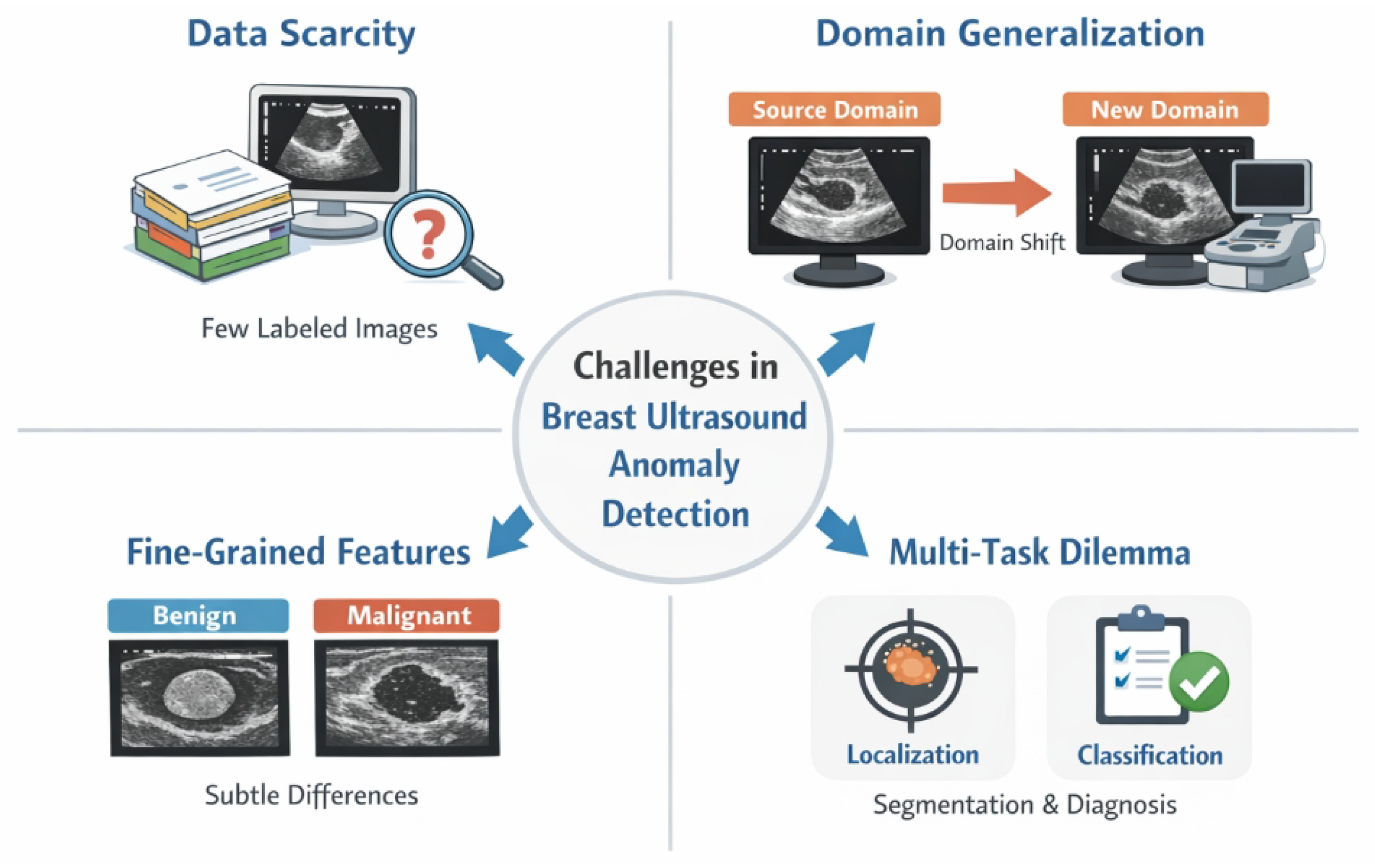

- Data Scarcity: The acquisition of large-scale, high-quality annotated medical image datasets is prohibitively expensive and time-consuming, severely restricting the application of data-hungry deep learning models in clinical practice. Few-shot learning (FSL) has thus emerged as a crucial direction to mitigate this issue [2].

- Domain Generalization: Ultrasound images exhibit significant variations in texture, contrast, and appearance due to differences in imaging equipment and acquisition protocols. This leads to a severe degradation in model performance when knowledge learned from one domain is applied to unseen domains [3].

- Fine-Grained Feature Capture: Subtle differences in ultrasound lesion characteristics are often critical for accurate benign-malignant differentiation. Models must be capable of capturing and discriminating these minute, fine-grained features effectively [4].

- Multi-Task Collaboration: Simultaneously performing pixel-level localization and image-level classification provides a more comprehensive diagnostic picture. However, effectively integrating knowledge from these two interdependent tasks remains an active area of research [5].

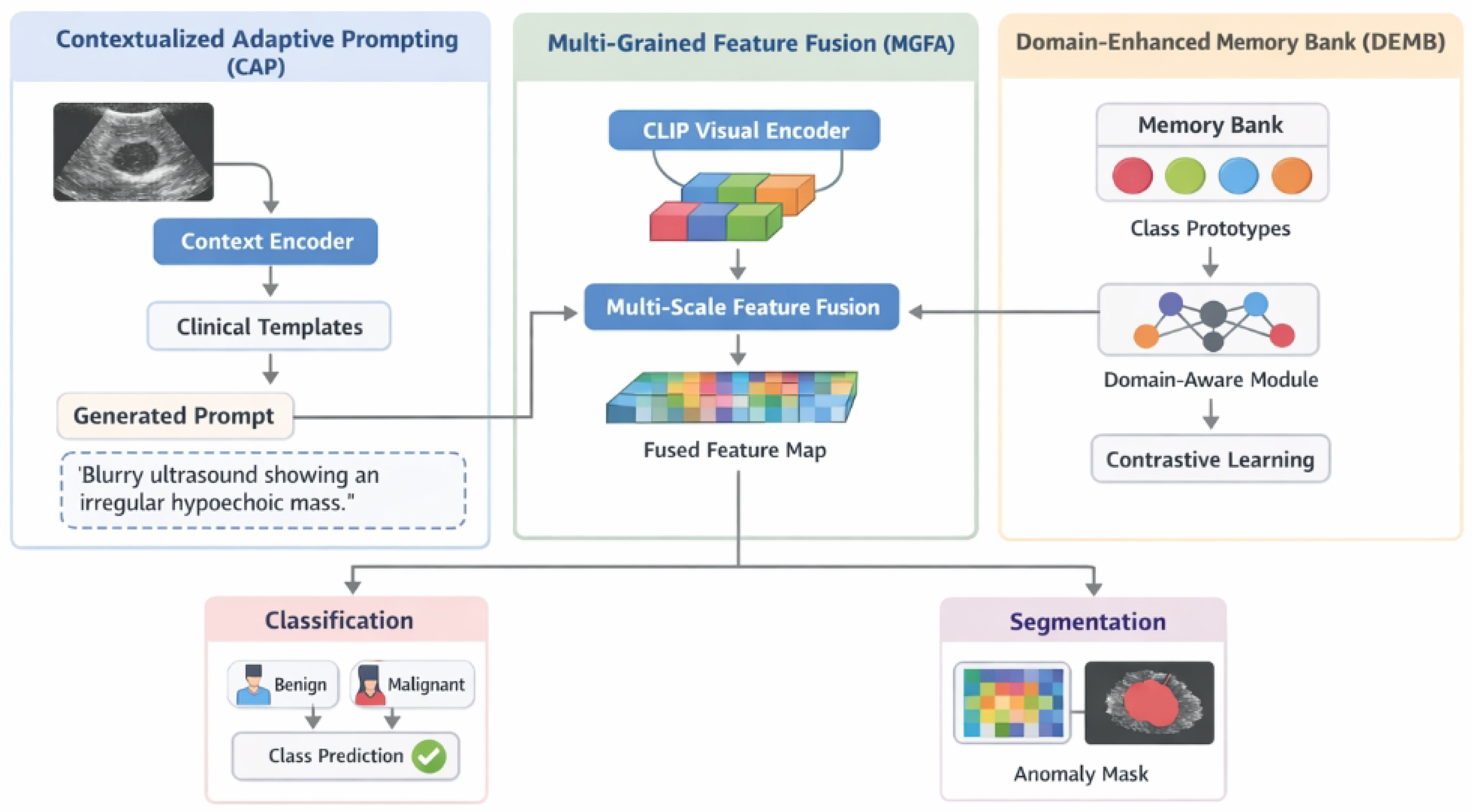

- We propose a novel Contextualized Adaptive Prompting (CAP) generator that integrates higher-order semantic context and clinical templates to create more discriminative and adaptive text prompts for enhanced zero-shot and few-shot classification.

- We introduce a Multi-Grained Feature Fusion Adapter (MGFA) which leverages gated attention to fuse features from multiple layers of the CLIP visual encoder, thereby achieving superior pixel-level localization and rich contextual information for image-level classification of ultrasound anomalies.

- We develop a Domain-Enhanced Memory Bank (DEMB) that improves cross-domain generalization by incorporating a lightweight domain-aware module to reduce intra-class feature distances across diverse source domains, improving robustness without extra adaptation.

2. Related Work

2.1. Vision-Language Models (VLMs)

2.2. Few-Shot and Zero-Shot Learning

2.3. Deep Learning for Medical Image Analysis and Domain Generalization

3. Method

3.1. Contextualized Adaptive Prompting (CAP)

3.1.1. Visual Context Extraction

3.1.2. Dynamic Prompt Generation

3.2. Multi-Grained Feature Fusion Adapter (MGFA)

3.2.1. Multi-Scale Feature Extraction and Alignment

3.2.2. Adaptive Feature Fusion

3.3. Domain-Enhanced Memory Bank (DEMB)

3.3.1. Memory Bank Structure

3.3.2. Domain-Invariant Embedding Learning

3.3.3. Domain-Enhanced Contrastive Loss

3.4. Multi-Task Joint Optimization

3.4.1. Pixel-Level Anomaly Localization

3.4.2. Image-Level Anomaly Classification

3.4.3. Overall Training Objective

4. Experiments

4.1. Experimental Setup

4.2. Datasets

4.3. Evaluation Metrics

4.4. Comparison with State-of-the-Art Methods

4.5. Ablation Studies

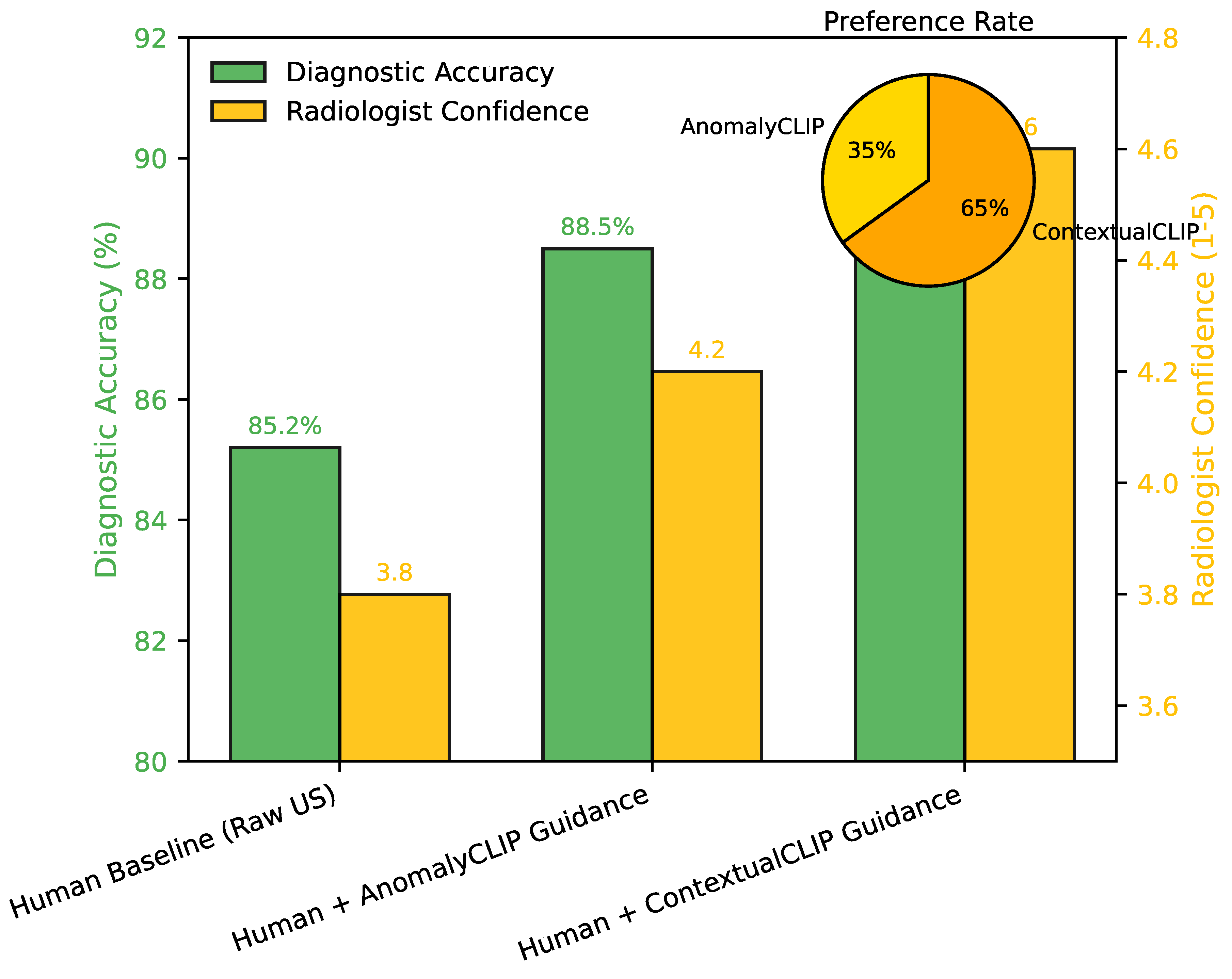

4.6. Human Evaluation

4.7. Performance Across Few-Shot Settings

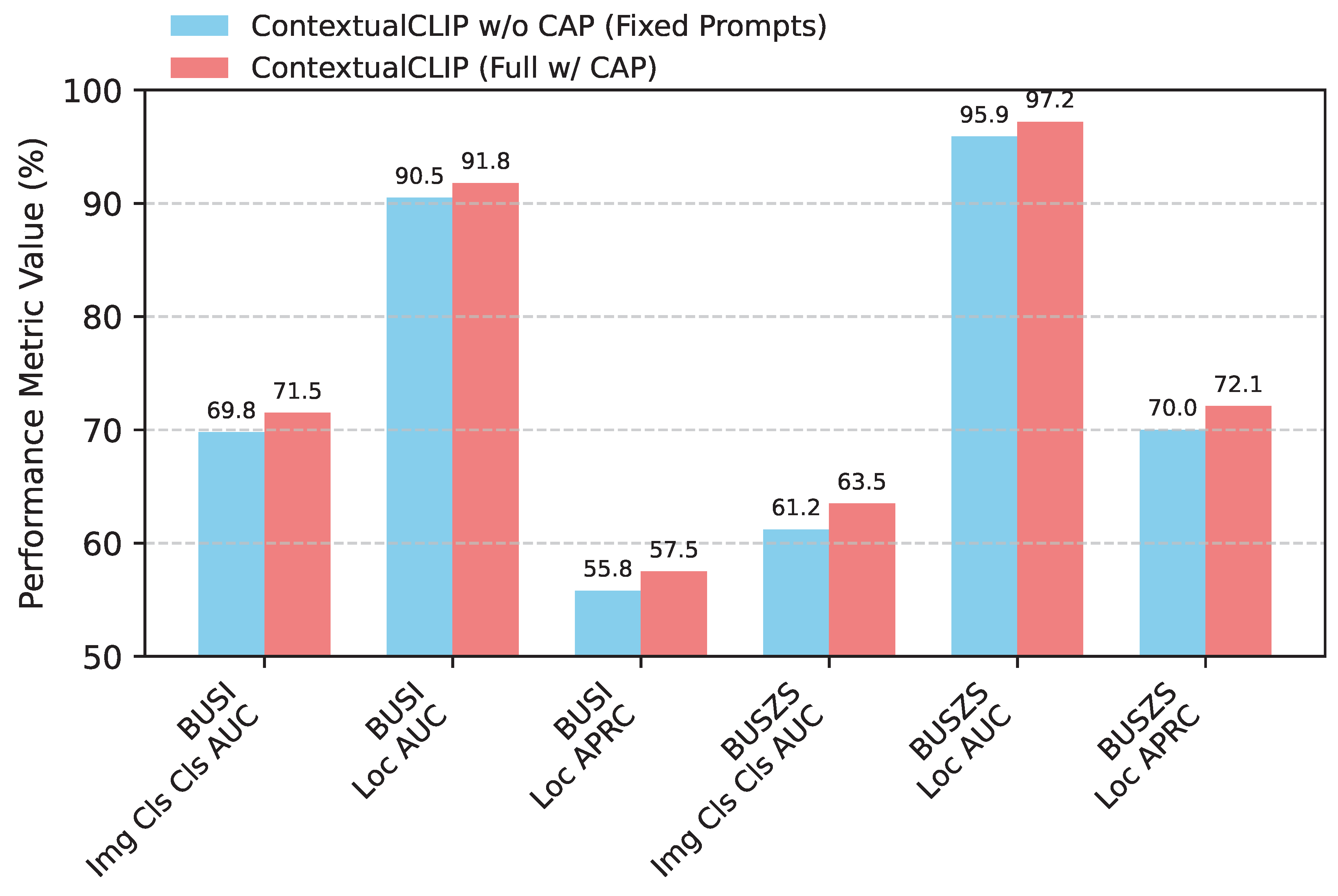

4.8. Impact of Contextualized Adaptive Prompting (CAP)

4.9. Parameter Efficiency and Inference Latency

5. Conclusion

References

- Hazarika, D.; Li, Y.; Cheng, B.; Zhao, S.; Zimmermann, R.; Poria, S. Analyzing Modality Robustness in Multimodal Sentiment Analysis. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2022 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2022, pp. 685–696. [CrossRef]

- Gao, T.; Fisch, A.; Chen, D. Making Pre-trained Language Models Better Few-shot Learners. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers). Association for Computational Linguistics, 2021, pp. 3816–3830. [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Wang, X.; Qin, Y.; Chan, C.M.; Lin, Y.; Wang, H.; Wen, K.; Liu, Z.; Li, P.; Li, J.; et al. On Transferability of Prompt Tuning for Natural Language Processing. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2022 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2022, pp. 3949–3969. [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.; Yoon, S.; Kale, A.; Dernoncourt, F.; Bui, T.; Bansal, M. Fine-grained Image Captioning with CLIP Reward. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: NAACL 2022, 2022; Association for Computational Linguistics; pp. 517–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Ghosh, G.; Huang, P.Y.; Okhonko, D.; Aghajanyan, A.; Metze, F.; Zettlemoyer, L.; Feichtenhofer, C. VideoCLIP: Contrastive Pre-training for Zero-shot Video-Text Understanding. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 2021; Association for Computational Linguistics; pp. 6787–6800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Dong, L.; Zhang, W.; Liu, T.; Wei, F. CLIP Models are Few-Shot Learners: Empirical Studies on VQA and Visual Entailment. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers). Association for Computational Linguistics, 2022, pp. 6088–6100. [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Dholey, M.; Vinod, P.K. A Dual-Mode ViT-Conditioned Diffusion Framework with an Adaptive Conditioning Bridge for Breast Cancer Segmentation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2511.05989v1 2025.

- Busi, M.; Focardi, R.; Luccio, F.L. Strands Rocq: Why is a Security Protocol Correct, Mechanically? In Proceedings of the 38th IEEE Computer Security Foundations Symposium, CSF 2025, Santa Cruz, CA, USA, June 16-20, 2025. IEEE, 2025, pp. 33–48. [CrossRef]

- Busi, M.; Degano, P.; Galletta, L. Translation Validation for Security Properties. arXiv preprint arXiv:1901.05082v1 2019.

- Paschke, A. ECA-LP / ECA-RuleML: A Homogeneous Event-Condition-Action Logic Programming Language. arXiv preprint arXiv:cs/0609143v1 2006.

- Suter, D.; Tennakoon, R.B.; Zhang, E.; Chin, T.; Bab-Hadiashar, A. Monotone Boolean Functions, Feasibility/Infeasibility, LP-type problems and MaxCon. CoRR, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, T.; Dai, W.; Liu, Z.; Fung, P. Vision Guided Generative Pre-trained Language Models for Multimodal Abstractive Summarization. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 2021; Association for Computational Linguistics; pp. 3995–4007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Yan, M.; Li, C.; Bi, B.; Huang, S.; Xiao, W.; Huang, F. E2E-VLP: End-to-End Vision-Language Pre-training Enhanced by Visual Learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers). Association for Computational Linguistics, 2021, pp. 503–513. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, Q.; Shen, J. Visual In-Context Learning for Large Vision-Language Models. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics, ACL 2024, Bangkok, Thailand and virtual meeting, August 11-16, 2024. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2024, pp. 15890–15902.

- Zhou, Y.; Long, G. Improving Cross-modal Alignment for Text-Guided Image Inpainting. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 17th Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 2023; pp. 3445–3456. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Tao, W.; Zhang, W. Triple sequence generative adversarial nets for unsupervised image captioning. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2021-2021 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), 2021; IEEE; pp. 7598–7602. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Bai, S.; Li, G.; Wang, Y.; Tang, Y. Open-vocabulary segmentation with semantic-assisted calibration. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2024; pp. 3491–3500. [Google Scholar]

- Han, K.; Liu, Y.; Liew, J.H.; Ding, H.; Liu, J.; Wang, Y.; Tang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Feng, J.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Global knowledge calibration for fast open-vocabulary segmentation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2023; pp. 797–807. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, F.; Cheng, Z.; Deng, C.; Li, H.; Lian, Z.; Chen, Q.; Liu, H.; Wang, W.; Zhang, Y.F.; Zhang, R.; et al. Mme-emotion: A holistic evaluation benchmark for emotional intelligence in multimodal large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2508.09210 2025.

- Zhang, F.; Li, H.; Qian, S.; Wang, X.; Lian, Z.; Wu, H.; Zhu, Z.; Gao, Y.; Li, Q.; Zheng, Y.; et al. Rethinking Facial Expression Recognition in the Era of Multimodal Large Language Models: Benchmark, Datasets, and Beyond. arXiv preprint arXiv:2511.00389 2025. arXiv.

- Ling, Y.; Yu, J.; Xia, R. Vision-Language Pre-Training for Multimodal Aspect-Based Sentiment Analysis. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers). Association for Computational Linguistics, 2022, pp. 2149–2159. [CrossRef]

- Ding, N.; Xu, G.; Chen, Y.; Wang, X.; Han, X.; Xie, P.; Zheng, H.; Liu, Z. Few-NERD: A Few-shot Named Entity Recognition Dataset. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers). Association for Computational Linguistics, 2021, pp. 3198–3213. [CrossRef]

- Ding, N.; Chen, Y.; Han, X.; Xu, G.; Wang, X.; Xie, P.; Zheng, H.; Liu, Z.; Li, J.; Kim, H.G. Prompt-learning for Fine-grained Entity Typing. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2022, 2022; Association for Computational Linguistics; pp. 6888–6901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Ji, K.; Fu, Y.; Tam, W.; Du, Z.; Yang, Z.; Tang, J. P-Tuning: Prompt Tuning Can Be Comparable to Fine-tuning Across Scales and Tasks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 2: Short Papers). Association for Computational Linguistics, 2022, pp. 61–68. [CrossRef]

- Tam, D.; R. Menon, R.; Bansal, M.; Srivastava, S.; Raffel, C. Improving and Simplifying Pattern Exploiting Training. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 2021; Association for Computational Linguistics; pp. 4980–4991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Ballesteros, M.; Doss, S.; Anubhai, R.; Mallya, S.; Al-Onaizan, Y.; Roth, D. Label Semantics for Few Shot Named Entity Recognition. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2022. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2022, pp. 1956–1971. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Cheng, H.; Klopfer, R.; Gormley, M.R.; Schaaf, T. Effective Convolutional Attention Network for Multi-label Clinical Document Classification. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 2021; Association for Computational Linguistics; pp. 5941–5953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nooralahzadeh, F.; Perez Gonzalez, N.; Frauenfelder, T.; Fujimoto, K.; Krauthammer, M. Progressive Transformer-Based Generation of Radiology Reports. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2021, 2021; Association for Computational Linguistics; pp. 2824–2832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A.; Pan, S. Incorporating medical knowledge in BERT for clinical relation extraction. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 2021; Association for Computational Linguistics; pp. 5357–5366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalopoulos, G.; Wang, Y.; Kaka, H.; Chen, H.; Wong, A. UmlsBERT: Clinical Domain Knowledge Augmentation of Contextual Embeddings Using the Unified Medical Language System Metathesaurus. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, 2021; Association for Computational Linguistics; pp. 1744–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Kumar, D.; Yang, W.; Zi, W.; Tang, K.; Huang, C.; Cheung, J.C.K.; Prince, S.J.; Cao, Y. Optimizing Deeper Transformers on Small Datasets. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers). Association for Computational Linguistics, 2021, pp. 2089–2102. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yu, R.; Yin, F.; Zhao, X.; Zhao, W.; Xia, W.; Yang, Y. Learning quality-aware dynamic memory for video object segmentation. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, 2022; Springer; pp. 468–486. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, F.; Cheng, Z.Q.; Zhao, J.; Peng, X.; Li, X. LEAF: unveiling two sides of the same coin in semi-supervised facial expression recognition. Computer Vision and Image Understanding 2025, 104451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labrak, Y.; Bazoge, A.; Morin, E.; Gourraud, P.A.; Rouvier, M.; Dufour, R. BioMistral: A Collection of Open-Source Pretrained Large Language Models for Medical Domains. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2024, 2024; Association for Computational Linguistics; pp. 5848–5864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madotto, A.; Lin, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Moon, S.; Crook, P.; Liu, B.; Yu, Z.; Cho, E.; Fung, P.; Wang, Z. Continual Learning in Task-Oriented Dialogue Systems. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 2021; Association for Computational Linguistics; pp. 7452–7467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, G.; Darrell, T.; Rohrbach, A. NewsCLIPpings: Automatic Generation of Out-of-Context Multimodal Media. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 2021; Association for Computational Linguistics; pp. 6801–6817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Lin, Z.; Zhao, D.; Zhao, W.; Flynn, D.; Ansari, S.; Wei, C. Evaluating scenario-based decision-making for interactive autonomous driving using rational criteria: A survey. arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.01886 2025.

- Lin, Z.; Tian, Z.; Lan, J.; Zhao, D.; Wei, C. Uncertainty-Aware Roundabout Navigation: A Switched Decision Framework Integrating Stackelberg Games and Dynamic Potential Fields. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2025, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Tian, Z.; He, Y.; Liu, S.; Chen, H.; Yuan, F.; Peng, Y. Enhanced mean field game for interactive decision-making with varied stylish multi-vehicles. arXiv preprint arXiv:2509.00981 2025.

- Huang, S.; et al. Real-Time Adaptive Dispatch Algorithm for Dynamic Vehicle Routing with Time-Varying Demand. Academic Journal of Computing & Information Science 2025, 8, 108–118. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S. Measuring Supply Chain Resilience with Foundation Time-Series Models. European Journal of Engineering and Technologies 2025, 1, 49–56. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, L.; et al. Real-time Threat Identification Systems for Financial API Attacks under Federated Learning Framework. Academic Journal of Business & Management 2025, 7, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Method | BUSI-16 | BUSZS-16 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-class | Localization | Multi-class | Localization | ||

| AUROC (%) | (AUROC, AUPRC) | AUROC (%) | (AUROC, AUPRC) | ||

| LP++ [10] | 70.1 | – | 62.2 | – | |

| ClipAdapter | 52.0 | – | 51.0 | – | |

| TipAdapter | 68.8 | – | 58.7 | – | |

| COOP | 67.7 | – | 62.1 | – | |

| AdaCLIP | – | (86.8, 52.4) | – | (95.4, 70.5) | |

| AnomalyCLIP [11] | – | (90.6, 56.0) | – | (96.6, 70.9) | |

| VCP-CLIP | – | (80.4, 38.4) | – | (83.5, 36.2) | |

| MVFA | – | (69.5, 16.2) | – | (93.5, 68.9) | |

| ContextualCLIP (Ours) | 71.5 | (91.8, 57.5) | 63.5 | (97.2, 72.1) | |

| Method | Multi-class AUROC (%) | Localization (AUROC) | Localization (AUPRC) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (UltraAD-like) | 68.5 | 89.2 | 54.1 |

| Baseline + CAP | 69.4 | 89.9 | 54.8 |

| Baseline + MGFA | 69.0 | 90.5 | 55.2 |

| Baseline + DEMB | 69.1 | 89.6 | 54.5 |

| Baseline + CAP + MGFA | 70.5 | 91.2 | 56.5 |

| Baseline + CAP + DEMB | 70.0 | 90.3 | 55.6 |

| Baseline + MGFA + DEMB | 69.8 | 90.9 | 55.9 |

| ContextualCLIP (Full) | 71.5 | 91.8 | 57.5 |

| Method | Metric | BUSI Dataset | BUSZS Dataset | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4-shot | 8-shot | 16-shot | 4-shot | 8-shot | 16-shot | |||

| ContextualCLIP | Cls AUROC (%) | 66.5 | 68.5 | 71.5 | 56.8 | 59.5 | 63.5 | |

| Loc AUROC (%) | 87.2 | 89.8 | 91.8 | 92.1 | 94.5 | 97.2 | ||

| Loc AUPRC (%) | 48.5 | 51.5 | 57.5 | 63.5 | 67.0 | 72.1 | ||

| LP++ (Cls Only) | Cls AUROC (%) | 64.5 | 67.0 | 70.1 | 54.5 | 57.0 | 62.2 | |

| AnomalyCLIP (Loc Only) | Loc AUROC (%) | 84.5 | 87.0 | 90.6 | 90.0 | 93.5 | 96.6 | |

| Loc AUPRC (%) | 45.5 | 48.0 | 56.0 | 60.0 | 63.0 | 70.9 | ||

| Method | Trainable Params (M) | Inference Latency (ms/image) |

|---|---|---|

| LP++ | 0.5 | 68 |

| AnomalyCLIP | 2.8 | 95 |

| VCP-CLIP | 1.2 | 75 |

| MVFA | 3.5 | 102 |

| ContextualCLIP (Ours) | 4.1 | 110 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).