Submitted:

20 December 2025

Posted:

22 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

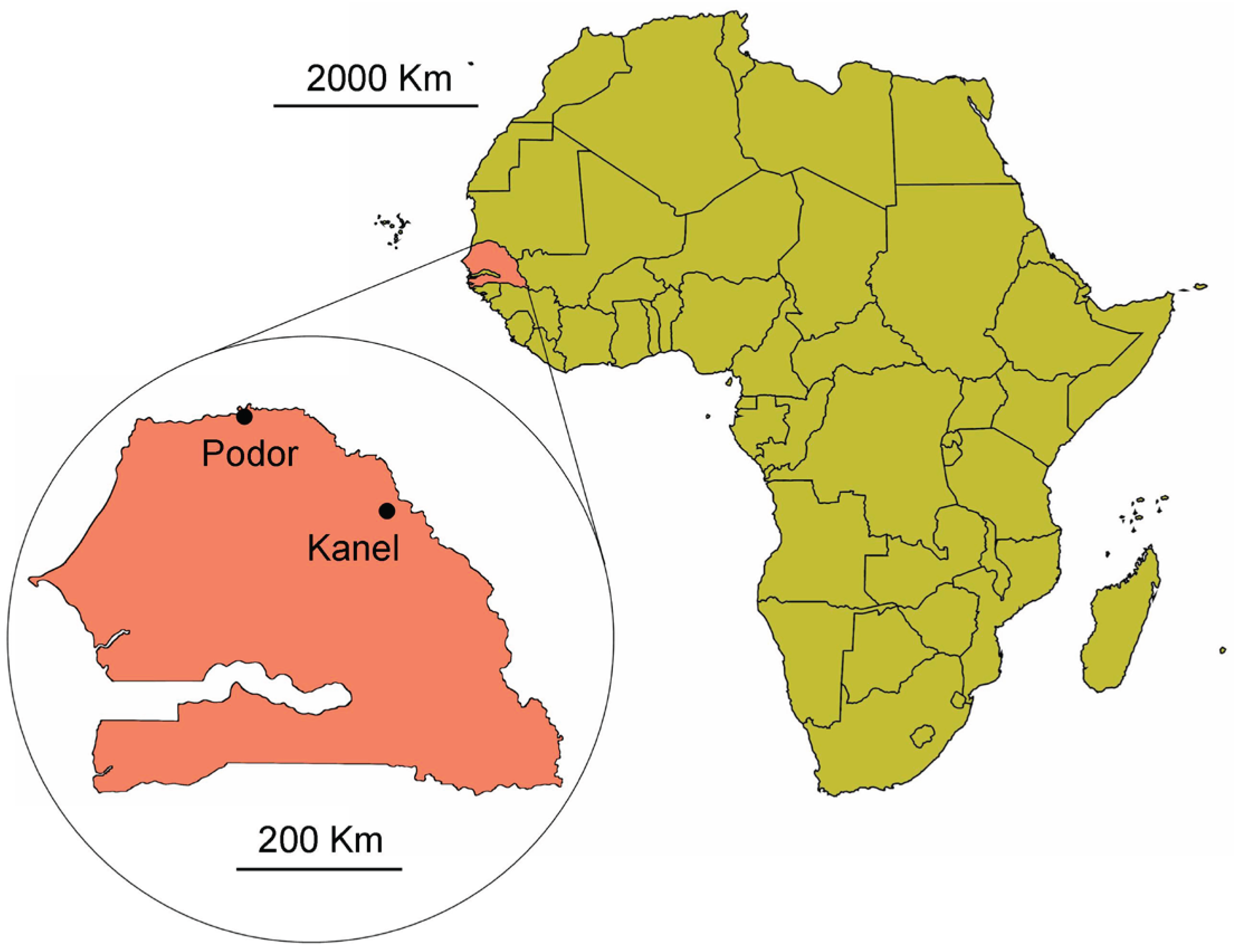

2.1. Study Area and Sampling Campaigns

2.2. Composter Design and Composting Methodology

2.3. Analysis of Waste Samples, Composting Material, Soil and Compost

2.3.1. Sampling and Pre-Treatment of the Sample

2.3.2. Fresh and Dry Moisture Content

2.3.3. Total Organic Matter

2.3.4. pH and Electrical Conductivity

2.3.5. Texture

2.3.6. Oxidisable Organic Carbon and Soluble Carbon

2.3.7. Carbon/Nitrogen

2.3.8. Nutrients and Potential Toxics Elements

2.3.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characteristics of Materials Undergoing Composting and Compost

3.2. Soil Characteristics

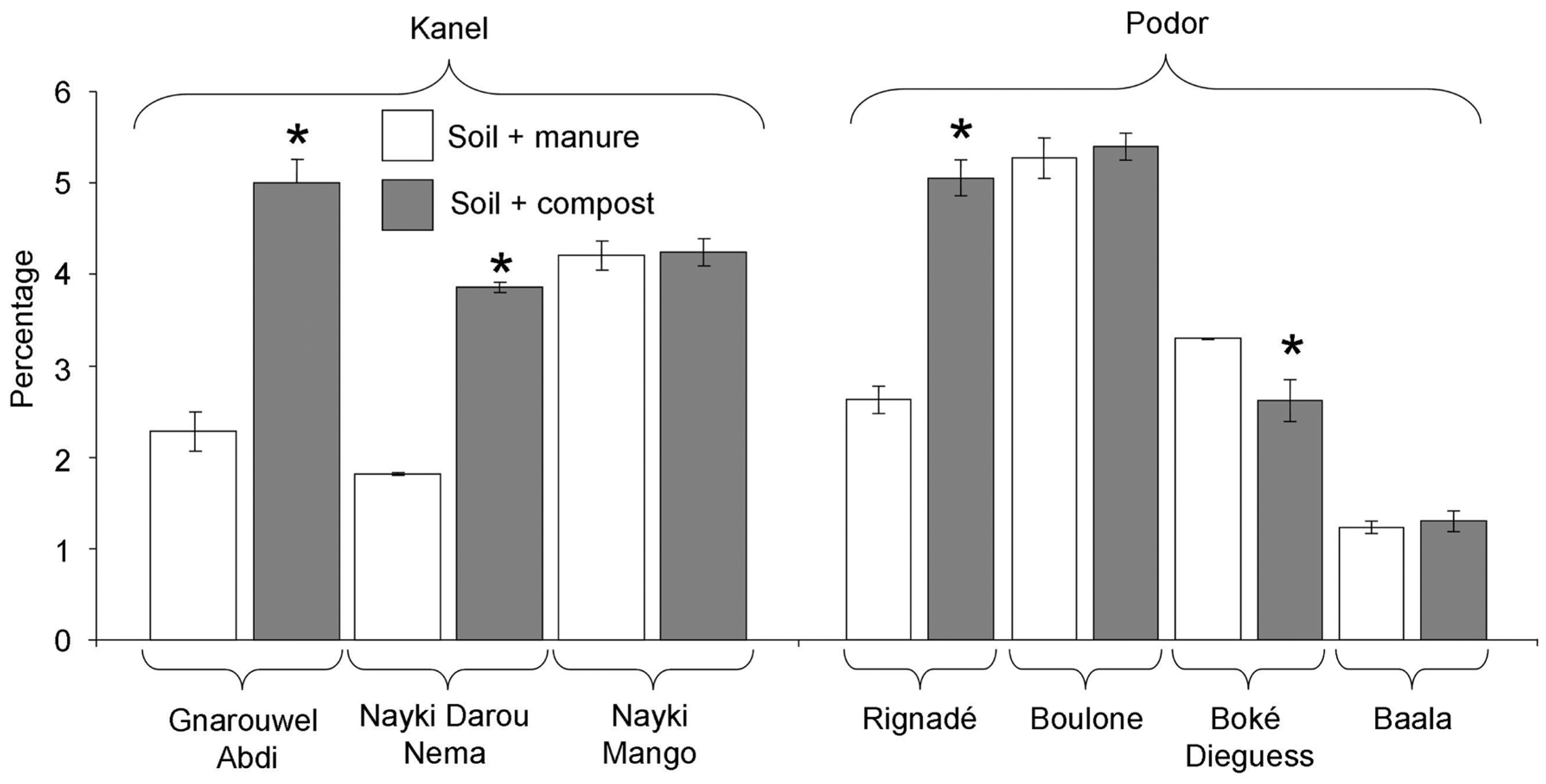

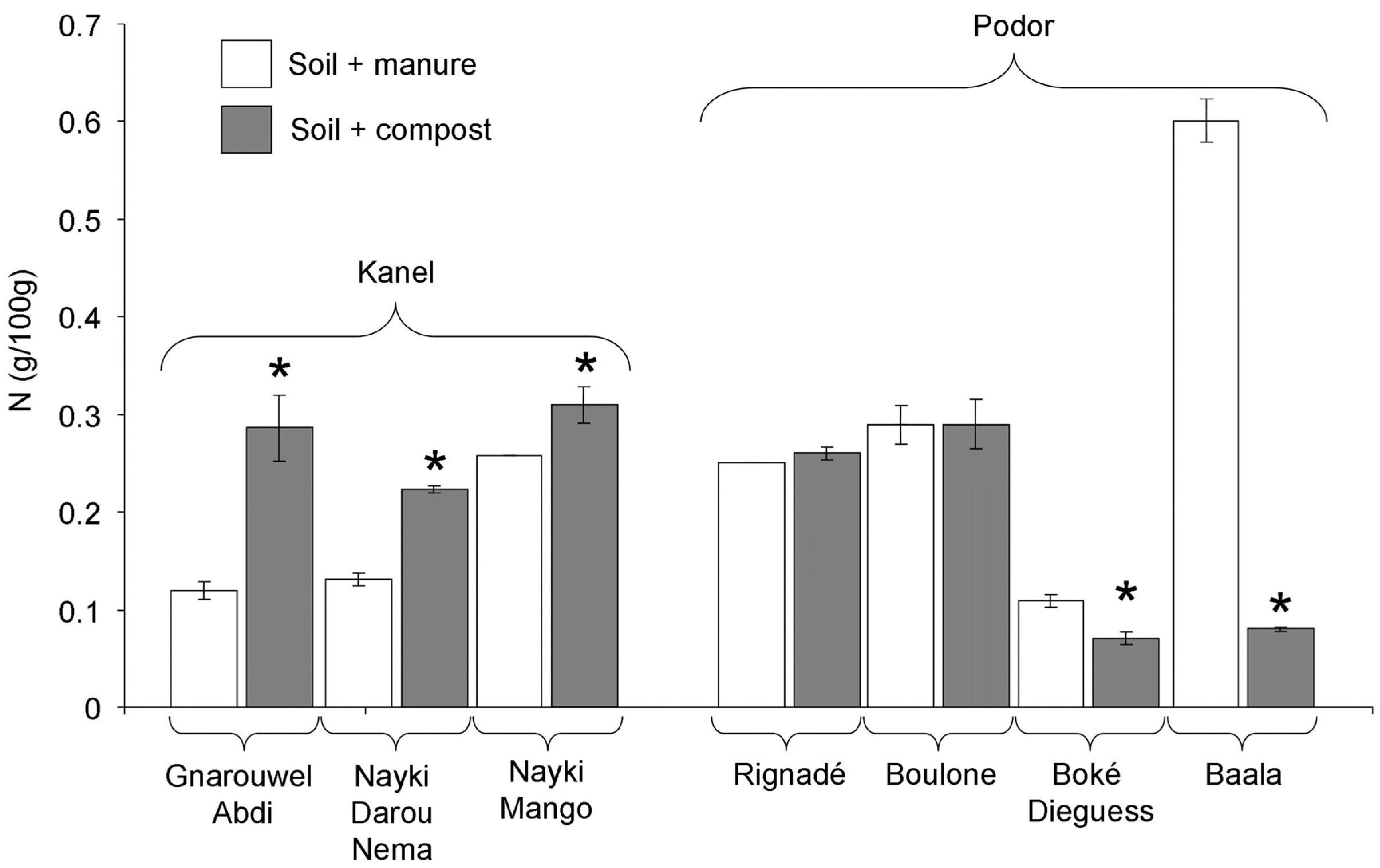

3.3. Application of Compost to the Soil

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aguilar-Paredes, A., Valdés, G., Araneda, N., Valdebenito, E., Hansen, F., & Nuti, M. (2023). Microbial Community in the Composting Process and Its Positive Impact on the Soil Biota in Sustainable Agriculture. agronomy, 13(2). [CrossRef]

- Aïssatou, N., Khadim, D., & Mansour, D. (2023). Spatial Distribution of Climate Risk. Comprehensive action for climate change initiative(06) https://akademiya2063.org/publications/CACCI%20Field%20Notes/CACCI%20Field%20Notes%20No.%2006.pdf.

- Aleman, S. M. (Febrero / 2025). DatosMundial.com. https://www.datosmundial.com/africa/senegal/clima.php.

- Alui, K. A., Yao, S. D., N'guessan, K. A., BLE, P. A., Kouame, N. M., & DIARRASSAOUBA, N. (2020). Réussir le compostage en fosses dans un système intégré (culture/élevage) à l’environnement des parcs à karité au Nord de la Côte d’Ivoire. Journal of Applied Biosciences 148. https://www.ajol.info/index.php/jab/article/view/233976.

- Anwarul Islam Mondol, A., Hossain Chowdhury, M., Ahmed, S., & Alam , M. (2024). Nitrogen dynamics from conventional organic manures as influenced by different temperature regimes in subtropical conditions. Nitrogen, 5(3), 746-762. [CrossRef]

- Bahadur, S., Maurya, S., Bikrmaditya, Singh, R., & Shankar, S. (2022). Green manuring for sustainable crop production. Mahima Research Foundation and Social Welfare, 108-113. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/363091545_GREEN_MANURING_FOR_ SUSTAINABLE_CROP_PRODUCTION.

- Bank, W. (2023). TRANDING ECONOMICS. Senegal - Agriculture, Value Added (% Of GDP): https://tradingeconomics.com/senegal/agriculture-value-added-percent-of-gdp- wb-data.html.

- Barros, V. F. (2014). limate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part B:Regional Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth AssessmentReport of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York. https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/02/WGIIAR5-PartB_FINAL.pdf.

- Bationo, A., Kihara, J., Vanlauwe, B., Waswa, B., & Kimetu, J. (2007). Soil organic carbon dynamics, functions and management in west African agro-ecosystems. Agricultural Systems, 94(1), 13-25. [CrossRef]

- Batjes, N. H. (Març / 2001). Options for increasing carbon sequestration in west african soils: an exploratory study with special focus on Senegal. Land Degradation and Development, 12(2), 131-142. [CrossRef]

- Bissala, Y., & Payne, W. (23 / Maig / 2006). Effect of pit floor material on compost quality in semiarid west Africa. Soil Science Society of America Journal, 1140-1444. [CrossRef]

- CCME. (2007). Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment. Canadian soil quality guidelines for the protection of environmental and human health: summary tables. Canadian environmental quality guidelines.

- CE 889/2008. (05 / Setembre / 2008). por el que se establecen disposiciones de aplicación del Reglamento (CE) no 834/2007 del Consejo sobre producción yetiquetado de los productos ecológicos, con respecto a la producción ecológica, su etiquetado y su control. REGLAMENTO (CE) nº 889/2008 DE LA COMISIÓN. Unió Europea. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/ES/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX%3A32008R0889.

- Climate Data. (2023). Climate Data. (C. C. Service, Editor, & ECMWF, Productor) Clima Podor (Senegal): https://es.climate-data.org/africa/senegal/podor/podor-32284/.

- Climate Data. (2023). Dakar Climate (Senegal). (C. C. information, Editor, & ECMWF, Productor) Retrieved Maig / 2025, from Climate Data: https://en.climate- data.org/africa/senegal/dakar/dakar-521/.

- Day, P. (1965). Particle fractionation and particle-size analysis. In Methods of Soil Analisis: Part 1 Physical and Mineralogical Properties, Including statistics of Measurement and Sampling. American society of Agronomy, 545-567.

- Diack, M., Diom, F., Sow, K., & Sène, M. (2017). Soil Characterization and Classification of the Koutango Watershed in the Semi-Arid Southern Peanut Basin of Senegal. International Journal of Plant & Soil Science, 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Directorate of Analysis, F. a. (2020). Food and Agriculture Organization of the United States. Agricultural integrated survey programme (AGRISurvey): https://www.fao.org/in-action/agrisurvey/news/news-detail/senegal-published- the-annual-agricultural-survey-2019-2020-report--providing-data-and- information-on-the-country-s-agricultural-sector/en.

- DOGC 153/2019. (03 / Juliol / 2019). DECRET 153/2019, de 3 de juliol, de gestió de la fertilització del sòl i de les dejeccions ramaderes i d'aprovació del programa d'actuació a les zones vulnerables en relació amb la contaminació per nitrats que procedeixen de fonts agràries. Catalunya. https://portaljuridic.gencat.cat/eli/es- ct/d/2019/07/03/153.

- EPA. Microwave assisted acid digestion of sediments, sludges, soils, and oils. In 2007. Accessed: October 7, 2025, from https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2015-12/documents/3051a.pdf.

- Fall, S. (2003). SPATIOTEMPORAL CLIMATE VARIABILITY OVER SENEGAL. 229.

- FAO. Plataforma de conocimientos sobre agricultura familiar. Accessed: 07 / Juny / 2025, from Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Alimentación y la Agricultura: https://www.fao.org/family-farming/themes/agroecology/es/.

- FAO (1977). Soil map of the world (Vol. VI). Italia. https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/5379e5cb-24e7-4674- b6b5-0cdd3a730379/content.

- Faye, A., Dièye, m., Bilal Diakhaté, P., Bèye, A., Sall, M., Diop, M. (2021). Senegal – Land, climate, energy, agriculture and development. A study in the Sudano-Sahel Initiative for Regional Development, Jobs, and Food Security. ZEF Working Paper Series, ISSN 1864-6638 Center for Development Research, University of Bonn.

- Fernández, L. R. (2024). DESERTIFICACIÓN EN SENEGAL: UN ANÁLISIS DESDE LA AGRICULTURA COLONIAL Y LA ACCIÓN ACTUAL.https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/libro?codigo=976977.

- García-Serrano, P., Lucena, JJ., Ruano S., Nogales M. Guía práctica de la fertilización racional de los cultivos en España. Ministerio de Medio Ambiente y Medio Rural y Marino. 2010. ISBN 978-84-491-0997-3.

- Giche, Y. H. (2020). Evaluation of Some Physicochemical Parameters of Compost Produced from Coffee Pulp and Locally Available Organic Matter at Dale District, Southern Ethiopia. American Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering, 8(2), 17-26. [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Rico Núñez de Arenas, M. F. (2008). Estudio de contaminantes orgánicos en el aprovechamiento de lodos de depuradora de aguas residuales urbanas. https://rua.ua.es/dspace/bitstream/10045/7719/1/tesis_doctoral_francisca_gome z.pdf.

- Habanabakize, E., Ba, K., & Corniaux, C. (2022). A typology of smallholder livestock production systems reflecting the impact of the development of a local milk collection industry: Case study of Fatick region, Senegal. Pastoralism. [CrossRef]

- Hernández, C. M., Faye, A., Ousseynou Ly, M., Stewart, Z. P., Vara Prasad, P., Mendes Bastos, L., . . . Ciampitti, I. A. (2021). Soil and Climate Characterization to Define Environments for Summer Crops in Senegal. Sustainability, 13(21). [CrossRef]

- Hotfbauer, M., Kincl, D., Vopravil, J., Kabelka, D., & Vráblík, P. (11 / Gener / 2023). Preferential Erosion of Soil Organic Carbon and Fine-Grained Soil Particles—An Analysis of 82 Rainfall Simulations. Agronomy, 13(1). [CrossRef]

- Ibañez Bobadilla, C. (2021). Comparación entre enmiendas orgánicas y lombricompost en el mejoramiento de propiedades del suelo. Agroinformativo Mayor, 1(2). [CrossRef]

- Jusoh, M.L.C., Manaf, L.A. & Latiff, P.A. Composting of rice straw with effective microorganisms (EM) and its influence on compost quality. J Environ Health Sci Engineer 10, 17 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Kaboré, T. W.-T., Houot, S., Hien, E., Zombré , P., Hien, V., & Masse, D. (2010). Effect of the raw materials and mixing ratio of composted wastes on the dynamic of organic matter stabilization and nitrogen availability in composts of Sub-Saharan Africa. Bioresource Technology, 101(3), 1002-1013. [CrossRef]

- Klopp, H. (28 / Novembre / 2023). Soil Carbon Cycle and Laboratory Measurements of Carbon Related to Soil Health. South Dakota State University Extension: https://extension.sdstate.edu/soil-carbon-cycle-and-laboratory-measurements- carbon-related-soil-health.

- Larbi, G. (2023). The natural and Climatic Characteristics of the African Sahel Region and Their Repercussions on the Population. Almuqadimah of Human and Studies Journal Volume (8) Issue (2). https://asjp.cerist.dz/en/article/238745.

- Liang, Y., Leonard, J., Feddes, J., & McGill, W. (2006). Influence of carbon and buffer amendment on ammonia volatilization in composting. Bioresource Technology, 97(5), 748-761. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X., Shi, Y., Kong, L., Tong, L., Cao, H., Zhou, H., & Lv, Y. (2022). Long-Term Application of Bio-Compost Increased Soil Microbial Community Diversity and Altered Its Composition and Network. microorganisms, 10(2). [CrossRef]

- Llavors d´aci. (n.d.). L'agricultura ecològica. Retrieved 07 / Juny / 2025, from LLAVORS d'ACÍ: https://llavorsdaci.org/conservar-la-biodiversitat/lagricultura- ecologica/.

- Lu, J.;Wang, J.; Gao, Q.; Li, D.; Chen, Z.;Wei, Z.; Zhang, Y.;Wang, F. Effect of Microbial Inoculation on Carbon Preservation during Goat Manure Aerobic Composting. Molecules 2021, 26, 4441. [CrossRef]

- Mager Mendiguren, U., Ibarretxe Anuntzibai, L., Legarzegi Irazabal, X., Mayora Sarasua, H., Escudero Olabuenaga, A., Artetxe Arrien, A., & Ruiz de Arkaute Rivero, R. (2012). Compostaje de estiercoles en ganaderia ecológica. https://www.biolur.eus/documentos/descargas/Guia_de_compostaje_final_cast.pdf.

- Mengel, K., A. Kirkby, E., Kosegarten, H., & Appel, T. (2001). Magnesium. Spinger Nature, 541-552. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-94-010-1009-2_12.

- Mohd Lokman Che Jusoh, Latifah Abd Manaf and Puziah Abdul Latiff. Composting of rice straw with effective microorganisms (EM) and its influence on compost quality. Iranian Journal of Environmental Health Sciences & Engineering 2013, 10:17.

- Nathan, C. M., & Amadou, M. D. (2005). Soil fertility management and compost use in Senegal’s Peanut Basin. NTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF AGRICULTURAL SUSTAINABILITY, 3(2). [CrossRef]

- Negro, M. J., Villa, F., Aibar, J., Aracón, R., Ciria, P., Cristóbal, M. V., . . . Zarago. (2000). Producción y gestión del compost. DIGITAL.CSIC, 31. https://digital.csic.es/handle/10261/16792.

- Nomadseason. (2024). Monthly climate in Kanel, Matam, Senegal. (C. C. Service, Editor, & Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service) nomadseason: https://nomadseason.com/climate/senegal/matam/kanel.html.

- Obeng, S. K., Kulhánek, M., Balík, J., Černý, J., & Sedlář, O. (2024). Manganese: From Soil to Human Health-A Comprehensive Overview of Its Biological and Environmental Significance. Nutrients. [CrossRef]

- OECD (2023) Achieving SDG results in development co-operation—a comparative assessment. https://one.oecd.org/document/DCD(2023)29/en/pdf.

- Ouédraogo, E., Mando, A., & Zombré, N. (Maig / 2001). Use of compost to improve soil properties and crop productivity under low input agricultural system in West Africa. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 84(3), 259-266. [CrossRef]

- Policastro, G., & Cesaro, A. (2022). Composting of Organic Solid Waste of Municipal Origin: The Role of Research in Enhancing Its Sustainability. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. [CrossRef]

- Porta, J. C., Lopez-Acevedo, M. R., & Rodriguez, R. O. (1986). Tecnicas y experimentos en edafologia (Vol. 1). Barcelona.

- Rajat Kumar, Y., Kaushal, S., Kaur, G., & Gulati, D. (Maig / 2022). Effect of soil organic matter on physical properties of soil. JUST AGRICULTURE, 1(2). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/360560644_Effect_of_soil_organic_mat ter_on_physical_properties_of_soil.

- Ramos Mompó, C., & Palomares García, F. (2009). GUÍA PRÁCTICA DE LA FERTILIZACIÓN RACIONAL DE LOS CULTIVOS EN ESPAÑA. 23 Abonado de los cultivos Hortícolas. https://www.mapa.gob.es/es/agricultura/publicaciones/01_FERTILIZACI%C3%93 N(BAJA)_tcm30-57890.pdf.

- Real Decreto 506/2013. (28 / Juny / 2013). Real Decreto 506/2013, de 28 de junio, sobre productos fertilizantes. BOE-A-2013-7540. Boletín Oficial del Estado. https://www.boe.es/eli/es/rd/2013/06/28/506/con.

- Real Decreto 9/2005. (2005). Real Decreto 9/2005, de 14 de enero, por el que se establece la relación de actividades potencialmente contaminantes del suelo y los criterios y estándares para la declaración de suelos contaminados. BOE-A-2005-895. Boletín Oficial del Estado. https://www.boe.es/buscar/doc.php?id=BOE-A-2005-895.

- Roca-Pérez, L., Martínez, C., Marcilla, P., & Boluda, R. (2009). Composting rice straw with sewage sludge and compost effects on the soil-plant system. Chemosphere, 75(6), 781–787. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutunga, V., Karanja, N., & Gachene, C. (2008). ix month-duration Tephrosia vogelii Hook.f. and Tithonia diversifolia (Hemsl.) A.Gray planted-fallows for improving maize production in Kenya. Biotechnology, Agronomy and Society and Environment, 267-278.

- Rynk, R., Van de Kamp, M., Singley, M., & Willson, G. (Juny / 1992). On-Farm Composting Handbook. Northeast Regional Agricultural Engineering Service. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/238283750_On- Farm_Composting_Handbook.

- Saña, J., & Soliva, M. (2006). Condiciones para el compostaje in situ de deyecciones ganaderas sólidas. Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya. https://upcommons.upc.edu/bitstream/handle/2117/9747/Soliva%20compost_fe ms_es.pdf.

- Sawyer, C., & P.L., M. (1978). Chemistry for Environmental Engineering, 3rd Edition. Ammonia Odors: https://compost.css.cornell.edu/odors/ammonia.html#2.

- Sneh, G., S.K., D., & K.K., K. (2005). Chemical and biological changes during composting of different organic wastes and assessment of compost maturity. Bioresource Technology, 96(14), 1584-1591. [CrossRef]

- Suchá, L., Dušková, L., Leventon, J. et al. Knowledge based interventions for sustainable development cooperation: insights from knowledge systems mapping in Zambia. Sustain Sci 19, 1543–1559 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Tall, M., Bamba Sylla, M., Diallo, I., & S. Pal, J. (2017). Projected impact of climate change in the hydroclimatology of Senegal with a focus over the Lake of Guiers for the twenty-first century. Theoretical and Applied Climatology. [CrossRef]

- Tappan, G., Sall, M., Wood, E., & Cushing, M. (2004). Ecoregions and land cover trends in Senegal. Journal of Arid Environments, 427-462. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0140196304000783.

- The University of MAINE. (sense data). Compost Report Interpretation Guide. https://umaine.edu/soiltestinglab/wp-content/uploads/sites/227/2016/07/Compost-Report-Interpretation-Guide.pdf.

- TheGlobalEconomy.com. (2022). Senegal, Employment in agriculture: https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/senegal/Employment_in_agriculture/.

- Tomislav, H., Leenaars, J. G., Keith, D., Markus, G., Gerard, B., Tekaligno, M., . . . Matthew, C. (2017). oil nutrient maps of Sub-Saharan Africa: assessment of soil nutrient content at 250 m spatial resolution using machine learning. Nutrient Cycling in Agroecosystems, 109, 77-102. [CrossRef]

- Tovohery, R., Kalimuthu, S., Jean-Martial, J., Ali, I., Job, K., Andrew, S., & Kazuki, S. (2023). Estimating nutrient concentrations and uptake in rice grain in sub-Saharan Africa using linear mixed-effects regression. Fiel Crops Res. [CrossRef]

- Trisos, C., I.O., A., E., E., A., A., J., E., A. Gemeda, . . . S. Zakieldeen. (2022). Africa. In: Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. 1285–1455. [CrossRef]

- UNE-EN 77309:2001. Soil quality. Determination of specific electrical conductivity.

- UNE-EN 77321:2003. Soil quality. Determination of organic carbon and total carbon by dry combustion (elemental analysis).

- UNE-EN 77325:2003. Soil quality. Determination of total nitrogen content by dry combustion ("elemental analysis").

- UNE-EN 13040:2008. Soil improvers and growing media, preparation of the sample for physical and chemical tests, determination of dry matter content, moisture content and apparent density compacted in the laboratory.

- UNE-EN 13037:1012. Soil improvers and growing media. Determination of pH.

- UNE-EN 13038:2012. Soil improvers and growing media. Determination of electrical conductivity.

- UNE-EN 13039:2012. Soil improvers and growing media. Determination of organic matter and ash content.

- Unidas, N. (n.d). Objetivos de desarrollo sostenible. Sustaiable development: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/es/objetivos-de-desarrollo- sostenible/.

- United Nations (2019). United Nations sustainable development cooperation framework. https://unsdg.un.org/resources/united-nations-sustainable-development-cooperation-framework-guidance.

- Wang, Q., Li, Y., Klassen, W., & Hanlon Jr, E. (2022). Sunn Hemp—A Promising Cover Crop in Florida. Agricultural and Horticultural Enterprises. [CrossRef]

- Washaya S., Washaya D. Benefits, concerns and prospects of using goat manure in sub-Saharan Africa. Pastoralism (2023) 13:28. [CrossRef]

- Yavitt, J., T. Pipes, G., Olmos, E., Zhang, J., & Shapleigh, J. (08 / Febrer / 2021). oil Organic Matter, Soil Structure, and Bacterial Community Structure in a Post-Agricultural Landscape. Frontiers in Earth Science, 9. [CrossRef]

- Yongshan, C., Camps-Arbestain, M., Qinhua, S., Singh, B., & Cayuela, M. L. (2018). The long-term role of organic amendments in building soil nutrient fertility: a meta- analysis and review. Nutr Cycl Agroecosyst, 111, 103-125. [CrossRef]

| Department | Community | UTM coordinates (UTM zone, Easting, Northing) |

Elevation (metres above sea level) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kanel | Gnarouwel Abdi | 28N, 666224, 1675187 | 63 |

| Nayki Darou Nema | 28N, 661115, 1669201 | 66 | |

| Nayki Mango | 28N, 660550, 1670009 | 63 | |

| Podor | Rignadé | 28N, 606240, 1768765 | 45 |

| Boulone | 28N, 598377, 1773367 | 41 | |

| Boké Dieguess | 28N, 604496, 1775703 | 34 | |

| Baala | 28N, 603985, 1771850 | 31 |

| Parameter | Kanel | Podor | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gnarouwel Abdi | Nayki Mango | Boké Dieguess | ||

| pH | 9.40 ± 0.06 | 8.97 ± 0.03 | 8.40 ± 0.02 | |

| EC (dS/m) | 3.35 ± 0.48 | 3.03 ± 0.02 | 2.16 ± 0.15 | |

| COOx (%) | 34.07 ± 0.33 | 23.67 ± 0.60 | 12.38 ± 0.79 | |

| TOM (%) | 75.03 ± 0.89 | 53.64 ± 1 35 | 26.69 ± 0.63 | |

| Csol (%) | 2.15 ± 0 11 | 2.27 ± 0.03 | 0.62 ± 0.01 | |

| Ct (%) | 43.50 ± 1 20 | 34.28 ± 4.17 | 18.97 ± 3.72 | |

| Nt (%) | 2.82 ± 0.11 | 2.34 ± 0.19 | 1.32 ± 0.33 | |

| C/N | 15 | 15 | 14 | |

| K2O (g/100g) | 2.47 ± 0.14 | 1.68 ± 0.28 | 0.61 ± 0.15 | |

| P2O5 (g/100g) | 0.59 ± 0.02 | 0.48 ± 0.05 | 0.44 ± 0.07 | |

| MgO (g/100g) | 1.25 ± 0.05 | 0.84 ± 0.12 | 0.47 ± 0.11 | |

| CaO (g/100g) | 3.18 ± 0.12 | 2.53 ± 0.33 | 1.86 ± 0.38 | |

| S (g/100g) | 0.40 ± 0.02 | 0.27 ± 0.02 | 0.17 ± 0.04 | |

| Mn (mg/kg) | 1112 ± 40 | 817 ± 114 | 163 ± 28 | |

| Cu (mg/kg) | 18.28 ± 4.79 | 14.96 ± 2.47 | 13 ± 3.07 | |

| Zn (mg/kg) | 70.15 ± 20.17 | 71.57 ± 8.15 | 89 ± 13 | |

| Parameter | Kanel | Podor | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gnarouwel Abdi |

Nayki Darou Nema |

Nayki Mango | Rignadé | Boulone | Boké Dieguess | Baala | |

| pH | 8.88 ± 0.02 | 8.78 ± 0.07 | 7.71 ± 0.06 | 7.86 ± 0.02 | 8.92 ± 0.01 | 8.82 ± 0.06 | 7.33 ± 0.05 |

| EC (dS/m) | 6.53 ± 0.04 | 5.05 ± 0.11 | 3.35 ± 0.06 | 2.10 ± 0.01 | 0.77 ± 0.03 | 1.10 ± 0.07 | 2.20 ± 0.03 |

| COOx (%) | 22.18 ± 1.01 | 28.41 ± 2.08 | 13.29 ± 0.18 | 17.32 ± 0.33 | 15.73 ± 0.47 | 12.43 ± 0.32 | 13.15 ± 0.31 |

| TOM (%) | 49.20 ± 2.24 | 63.04 ± 4.62 | 29.48 ± 0.40 | 38.43 ± 0.74 | 34.91 ± 1.03 | 27.59 ± 0.70 | 29.18 ± 0.69 |

| Csol (%) | 0.93 ± 0.14 | 1.01 ± 0.13 | 0.56 ± 0.025 | 0.67 ± 0.02 | 0.35 ± 0.06 | 0.41 ± 0.18 | 0.56 ± 0.17 |

|

Moisture content fresh (%) |

54.95 ± 4.27 | 33.63 ± 2.46 | 52.79 ± 0.94 | 44.89 ± 0.64 | 47.28 ± 0.48 | 48.27 ± 0.42 | 33.81 ± 1.71 |

| Elements | Kanel | Podor | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gnarouwel Abdi | Nayki Darou Nema | Nayki Mango | Rignadé | Boulone | Boké Dieguess | Baala | |

| Ca (g/100g) | 2.22 ± 0.21 | 2.12 ± 0.09 | 2.24 ± 0.17 | 1.42 ± 0.09 | 1.27 ± 0.09 | 1.14 ± 0.07 | 0.99 ± 0.06 |

| K (g/100g) | 1.47 ± 0.11 | 1.15 ± 0.13 | 0.97 ± 0.12 | 0.58 ± 0.04 | 0.63 ± 0.04 | 0.47 ± 0.04 | 0.34 ±0.02 |

| Mg (g/100g) | 0.932 ± 0.88 | 0.81 ± 0.66 | 0.662 ± 0.41 | 0.36 ± 0.02 | 0.47 ± 0.02 | 0.34 ± 0.02 | 0.23 ±0.01 |

| Mn (mg/kg) | 1699.08 ± 23.54 | 1840.79 ± 10,29 | 1178.52 ± 9,97 | 306.69 ± 27.13 | 283.10 ± 12.99 | 264.40 ± 31.27 | 213.76 ± 15.42 |

| S (g/100g) | 0.410 ± 0.36 | 0.39 ± 0.041 | 0.28 ± 0.03 | 0.22 ± 0.01 | 0.30 ± 0.01 | 0.26 ± 0.02 | 0.16 ± 0.01 |

| P (g/100g) | 0.38 ± 0.03 | 0.28 ± 0.018 | 0.27 ± 0.03 | 0.22 ± 0.01 | 0.26 ± 0.01 | 0.23 ± 0.03 | 0.16 ± 0.01 |

| Ct (%) | 28.17 ± 3.25 | 34.94 ± 2.74 | 22.47 ± 0.19 | 22.18 ± 0.16 | 22.64 ± 1.55 | 23.94 ± 1.23 | 18.41 ± 1.29 |

| Nt (%) | 2.95 ± 0.19 | 3.42 ± 0.25 | 2.21 ± 0.14 | 1.69 ± 0.06 | 1.67 ± 0.18 | 1.84 ± 0.24 | 1.48 ± 0.09 |

| C/N | 9.55 ± 0.79 | 10.22 ± 0.98 | 10.17 ± 1.54 | 13.11 ± 0.99 | 13.52 ± 0.93 | 12.99 ± 0.99 | 12.41 ± 0.96 |

| Fe (g/Kg) | 3.83 ± 0.15 | 3.43 ± 0.25 | 8.62 ± 0.59 | 4.91 ± 0.38 | 4.87 ± 0.51 | 11.23 ± 0.99 | 4.34 ± 0.25 |

| Cu (mg/kg) | 18.02 ± 1.27 | 15.95 ± 1.22 | 17.06 ± 1.11 | 14.23 ± 0.97 | 16.29 ± 1.11 | 17.57 ± 0.09 | 10.09 ± 0.08 |

| Zn (mg/kg) | 86.17 ± 0.71 | 80.93 ± 7.52 | 83.72 ± 0.95 | 67.69 ± 0.38 | 78.38 ± 0.43 | 85.51 ± 7.41 | 48.70 ± 2.33 |

| Department | Community | pH | EC (dS/m) |

TOM (%) | Nt (%) | Sand (%) | Silt (%) | Clay (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kanel | Gnarouwel Abdi | 7.85 ± 0.08 | 0.685 ± 0.002 | 3.44 ± 0.12 | 0.13 ± 0.010 | 63 | 27 | 10 |

| Nayki Darou Nema | 7.33 ± 0.06 | 0.190 ± 0.003 | 2.49 ± 0.02 | 0.05 ± 0.002 | 75 | 20 | 5 | |

| Nayki Mango | 7.66 ± 0.04 | 0.292 ± 0.08 | 2.60 ± 0.05 | 0.09 ± 0.006 | 53 | 70 | 25 | |

| Podor | Rignadé | 7.46 ± 0.04 | 0.212 ± 0.004 | 1.13 ± 0.05 | <0.03 | 96 | 0 | 4 |

| Boulone | 7.62 ± 0.05 | 0.442 ± 0.005 | 1.64 ± 0.09 | 0.07 ± 0.004 | 90 | 6 | 4 | |

| Boké Dieguess | 7.87 ± 0.04 | 0.092 ± 0.001 | 1.22 ± 0.02 | <0.03 | 90 | 5 | 5 | |

| Baala | 7.85 ± 0.03 | 0.152 ± 0.006 | 1.53 ± 0.03 | 0.04 ± 0.002 | 95 | 5 | 0 |

| Department | Community | Treatment | pH | EC (dS/m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kanel | Gnarouwel Abdi | Soil + manure | 7.93 ± 0.07 | 0.2 ± 0.01 |

| Soil + compost | 8.21 ± 0.02 | 0.22 ± 0.04 | ||

| Nayki Darou Nema | Soil + manure | 8.07 ± 0.04 | 0.29 ± 0.00 | |

| Soil + compost | 8.61 ± 0.02 | 0.21 ± 0.01 | ||

| Nayki Mango | Soil + manure | 8.81 ± 0.09 | 0.34 ± 0.01 | |

| Soil + compost | 8.06 ± 0.02 | 0.33 ± 0.05 | ||

| Podor | Rignadé | Soil + manure | 8.5 ± 0.00 | 0.17 ± 0.01 |

| Soil + compost | 8.8 ± 0.01 | 0.14 ± 0.00 | ||

| Boulone | Soil + manure | 8.28 ± 0.00 | 0.23 ± 0.01 | |

| Soil + compost | 8.72 ± 0.05 | 0.13 ± 0.01 | ||

| Boké Dieguess | Soil + manure | 8.76 ± 0.08 | 0.12 ± 0.00 | |

| Soil + compost | 8.59 ± 0.07 | 0.12 ± 0.00 | ||

| Baala | Soil + manure | 8.23 ± 0.00 | 0.07 ± 0.00 | |

| Soil + compost | 8.84 ± 0.11 | 0.08 ± 0.01 |

| Department | Community | Treatment | Ca (g/100g) |

K (g/100g) |

Mg (g/100g) |

Mn (mg/kg) |

S (g/100g) |

P (g/100g) |

Cu (mg/kg) | Zn (mg/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kanel | Gnarouwel Abdi | Soil + manure | 0.25 ± 0.015 | 0.095 ± 0.008 | 0.081 ± 0.004 | 101.48 ± 9.37 | 0.019 ± 0.01 | 0.022 ± 0.001 | 4.69 ± 0.25 | 13.73 ± 0.98 |

| Soil + compost | 0.30 ± 0.04 | 0.168 ± 0.011 | 0.125 ± 0.009 | 181.65 ± 20.45 | 0.040 ± 0.005 | 0.050 ± 0.002 | 6.10 ± 0.58 | 22.51 ± 1.73 | ||

| Nayki Darou Nema | Soil + manure | 0.16 ± 0.012 | 0.086 ± 0.0071 | 0.072 ± 0.006 | 130.31 ± 10.87 | 0.021 ± 0.001 | 0.016 ± 0.002 | 4.14 ± 0.65 | 12.80 ± 1.90 | |

| Soil + compost | 0.19 ± 0.011 | 0.103 ± 0.009 | 0.075 ± 0.006 | 180.79 ± 12.74 | 0.024 ± 0.002 | 0.028 ± 0.003 | 5.98 ± 0.35 | 24.41 ± 1.87 | ||

| Nayki Mango | Soil + manure | 0.24 ± 0.19 | 0.219 ± 0.018 | 0.125 ± 0.011 | 213.27 ± 18.28 | 0.034 ± 0002 | 0.039 ± 0.003 | 5.99 ± 0.41 | 22.63 ± 2.21 | |

| Soil + compost | 0.33 ± 0.025 | 0.316 ± 0.025 | 0.167 ± 0.012 | 305.59 ± 27.94 | 0.037 ± 0.007 | 0.056 ± 0.002 | 10.66 ± 0.91 | 54.02 ± 2.77 | ||

| Podor | Rignadé | Soil + manure | 0.55 ± 0.043 | 0.093 ± 0.007 | 0.152 ± 0.013 | 107.63 ± 8.71 | 0.034 ± 0.002 | 0.041 ± 0.003 | 4.21 ± 0.37 | 15.29 ± 1.12 |

| Soil + compost | 0.35 ± 0.014 | 0.078 ± 0.005 | 0.118 ± 0.087 | 108.52 ± 7.88 | 0.032 ± 0.001 | 0.039 ± 0.007 | 4.46 ± 0.21 | 15.44 ± 0.99 | ||

| Boulone | Soil + manure | 0.41 ± 0.027 | 0.102 ± 0.015 | 0.134 ± 0.032 | 75.53 ± 8.91 | 0.037 ± 0.006 | 0.053 ± 0.002 | 4.43 ± 0.63 | 17.77 ± 1.54 | |

| Soil + compost | 0.44 ± 0.026 | 0.083 ± 0.007 | 0.134 ± 0.009 | 77.04 ± 4.48 | 0.035 ± 0.004 | 0.052 ± 0.003 | 4.09 ± 0.54 | 17.11 ± 1.33 | ||

| Boké Dieguess | Soil + manure | 0.17 ± 0.04 | 0.061 ± 0.003 | 0.089 ± 0.007 | 106.48 ± 9.22 | 0.020 ± 0.001 | 0.023 ± 0.004 | 3.30 ± 0.31 | 13.16 ± 1.25 | |

| Soil + compost | 0.15 ± 0.017 | 0.043 ± 0.002 | 0.070 ± 0.015 | 50.90 ± 5.38 | 0.014 ± 0.001 | 0.017 ± 0.002 | 2.76 ± 0.29 | 9.17 ± 0.71 | ||

| Baala | Soil + manure | 0.12 ± 0.009 | 0.032 ± | 0.053 ± 0.002 | 58.29 ± 6.63 | 0.008 ± 0.001 | 0.010 ± 0.001 | 2.14 ± 0.19 | 7.94 ± 0.62 | |

| Soil + compost | 0.14 ± 0.008 | 0.052 ± 0.003 | 0.065 ± 0.008 | 75.15 ± 6.22 | 0.011 ± 0.002 | 0.017 ± 0.001 | 2.71 ± 0.10 | 8.88 ± 0.49 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).