Submitted:

19 December 2025

Posted:

22 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

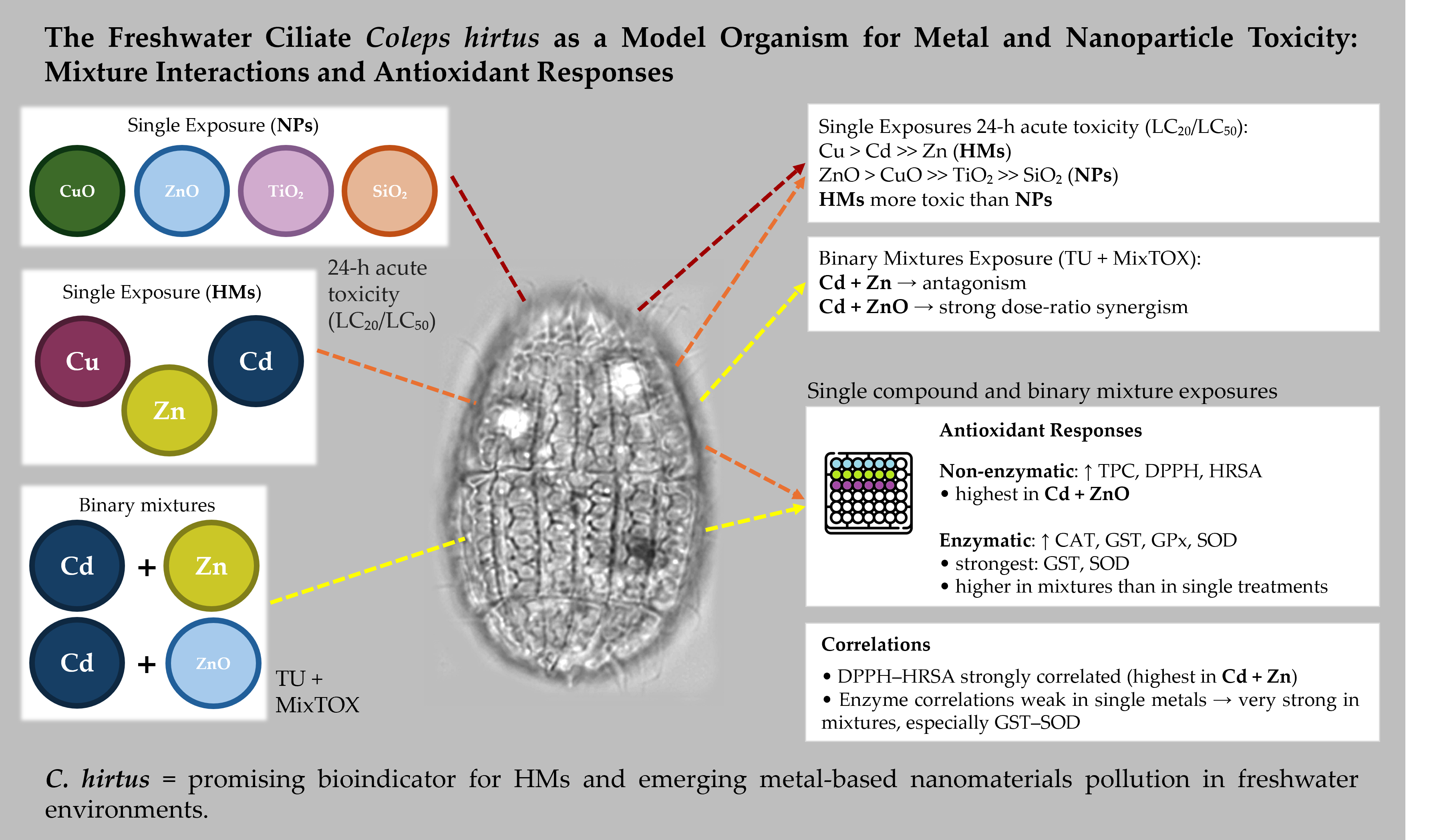

Heavy metals (HMs) and metal-oxide nanoparticles (NPs) frequently co-occur in freshwater systems, yet their combined effects on microbial predators remain poorly understood. Here, the freshwater ciliate Coleps hirtus was used to evaluate the cytotoxicity of single and binary mixtures of HMs (Cd, Cu, Zn) and NPs (ZnO, CuO, TiO₂, SiO₂), and to characterize associated antioxidant responses. Acute toxicity was assessed after 24 h by estimating LC₂₀ and LC₅₀ values, while mixture toxicity for Cd + Zn and Cd + ZnO was analyzed using the Toxic Unit approach and the MixTOX framework. Non-enzymatic (total phenolic content, DPPH, HRSA) and enzymatic (CAT, GST, GPx, SOD) antioxidants were quantified as sub-lethal biomarkers. HMs were markedly more toxic than NPs, with a toxicity ranking of Cu > Cd >> Zn, whereas NPs followed ZnO > CuO >> TiO₂ >> SiO₂. Cd + Zn mixtures showed predominantly antagonistic or non-interactive effects, while Cd + ZnO mixtures exhibited strong, dose-ratio–dependent synergism. Exposure to HMs and NPs induced significant and often coordinated changes in antioxidant biomarkers, with binary mixtures eliciting stronger responses than single contaminants. These results demonstrate that C. hirtus is sensitive to both HMs and metal-oxide NPs and can discriminate among different mixture interaction types. The combination of clear toxicity patterns and robust antioxidant responses supports the use of C. hirtus as a promising bioindicator for freshwater environments impacted by HMs and emerging metal-based nanomaterials.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

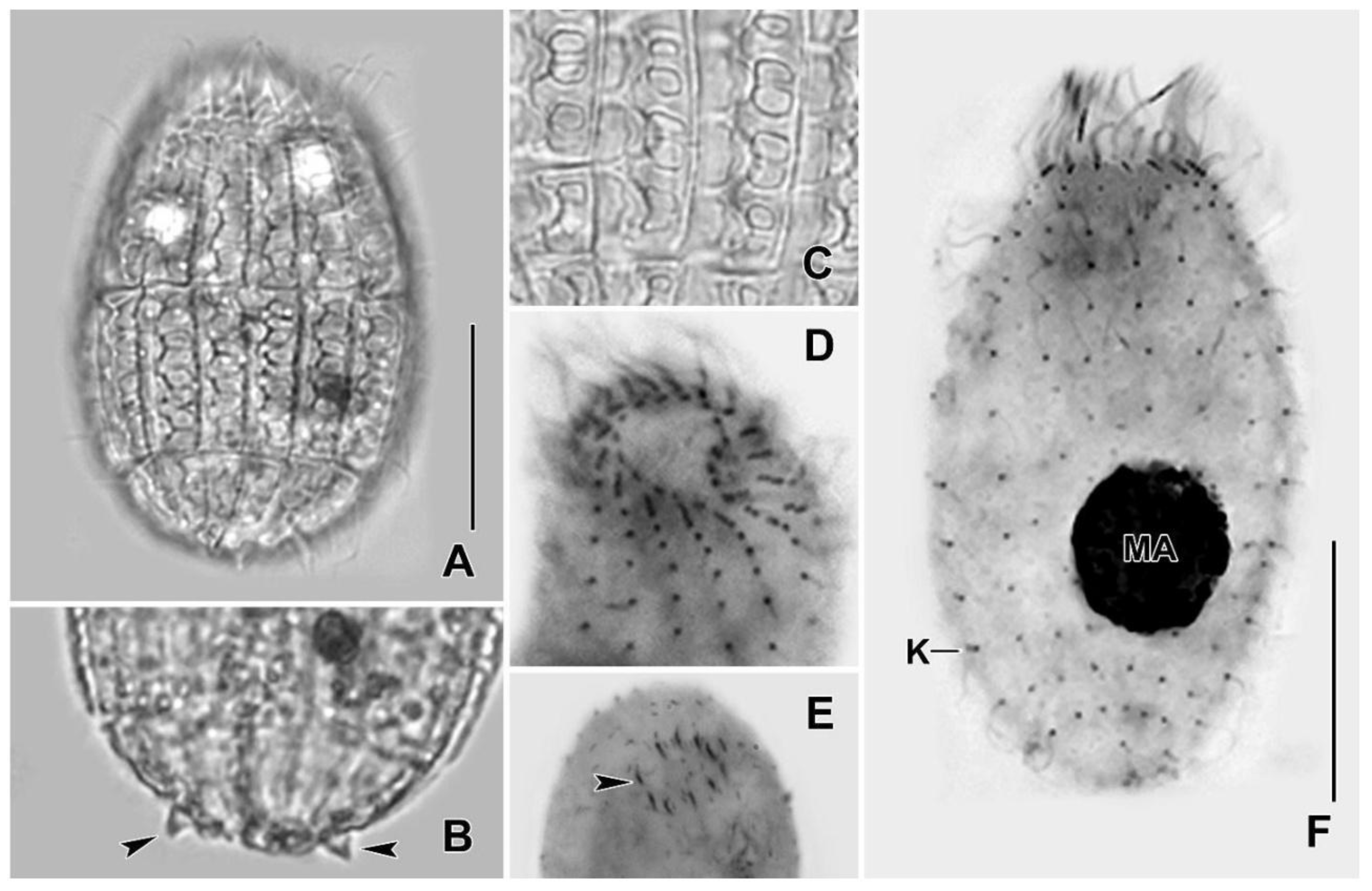

2.1. Ciliate Strain and Culture Conditions

2.2. Metal Salts and NPs Stock Preparation

2.3. Single HMs and NPs Toxicity Tests at 24 h

2.4. Binary Mixture Toxicity Tests (Cd + Zn, Cd + ZnO) at 24 h

2.5. Sample Preparation for Antioxidant Analyses

2.6. Non-Enzymatic Antioxidant Assays

2.7. Antioxidant Enzyme Assays

2.8. Statistical Analysis and MixTOX Modeling

3. Results

3.1. Cytotoxicity of Single HM and NP after 24 h of Exposure

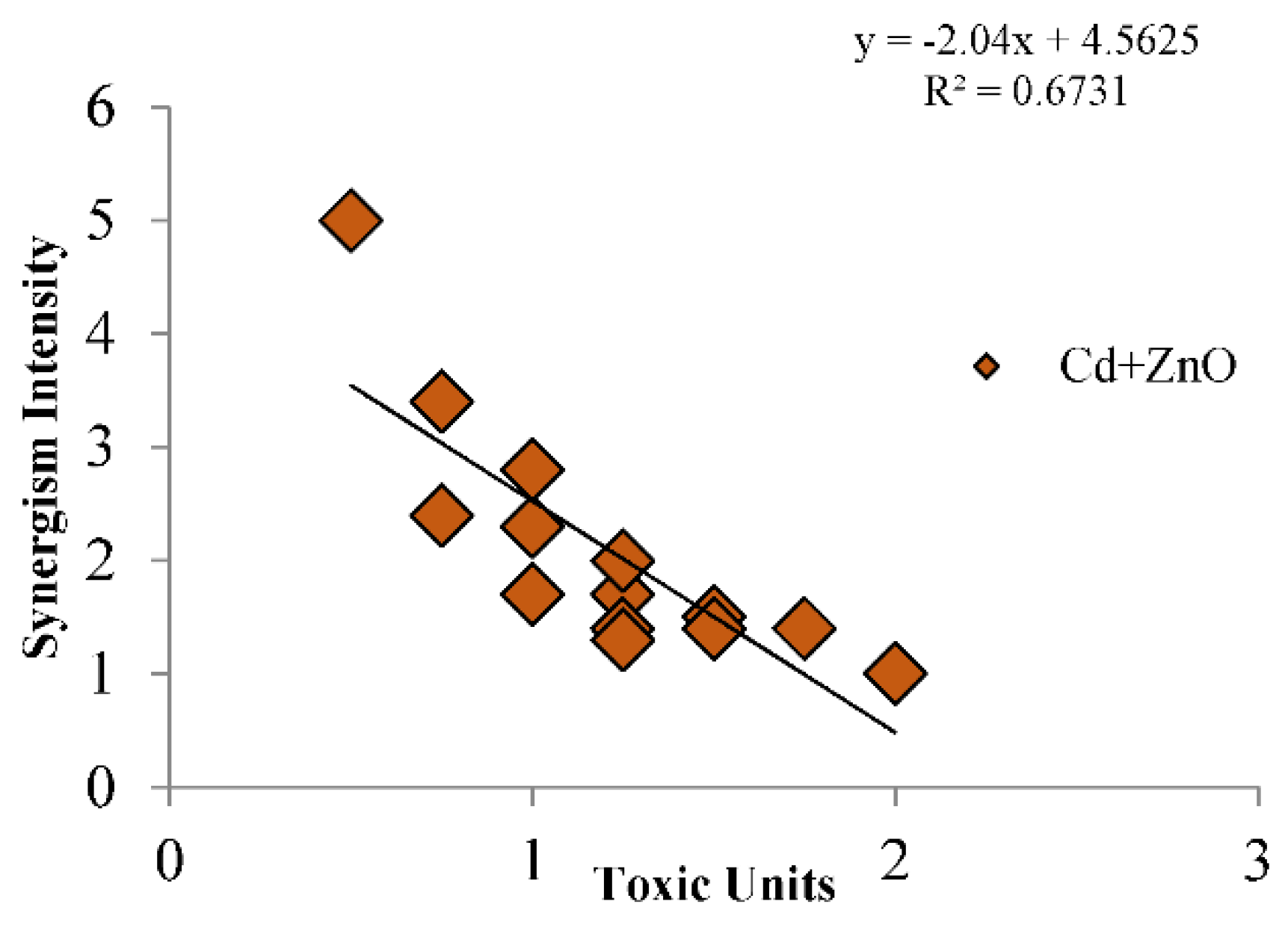

3.2. Cytotoxicity of Binary Mixtures (Cd + Zn and Cd + ZnO) after 24 h of Exposure

3.2.1. Toxic Unit (TU) Approach

3.2.2. MixTOX Modeling

3.3. Antioxidant Properties of Coleps hirtus Cell Extracts

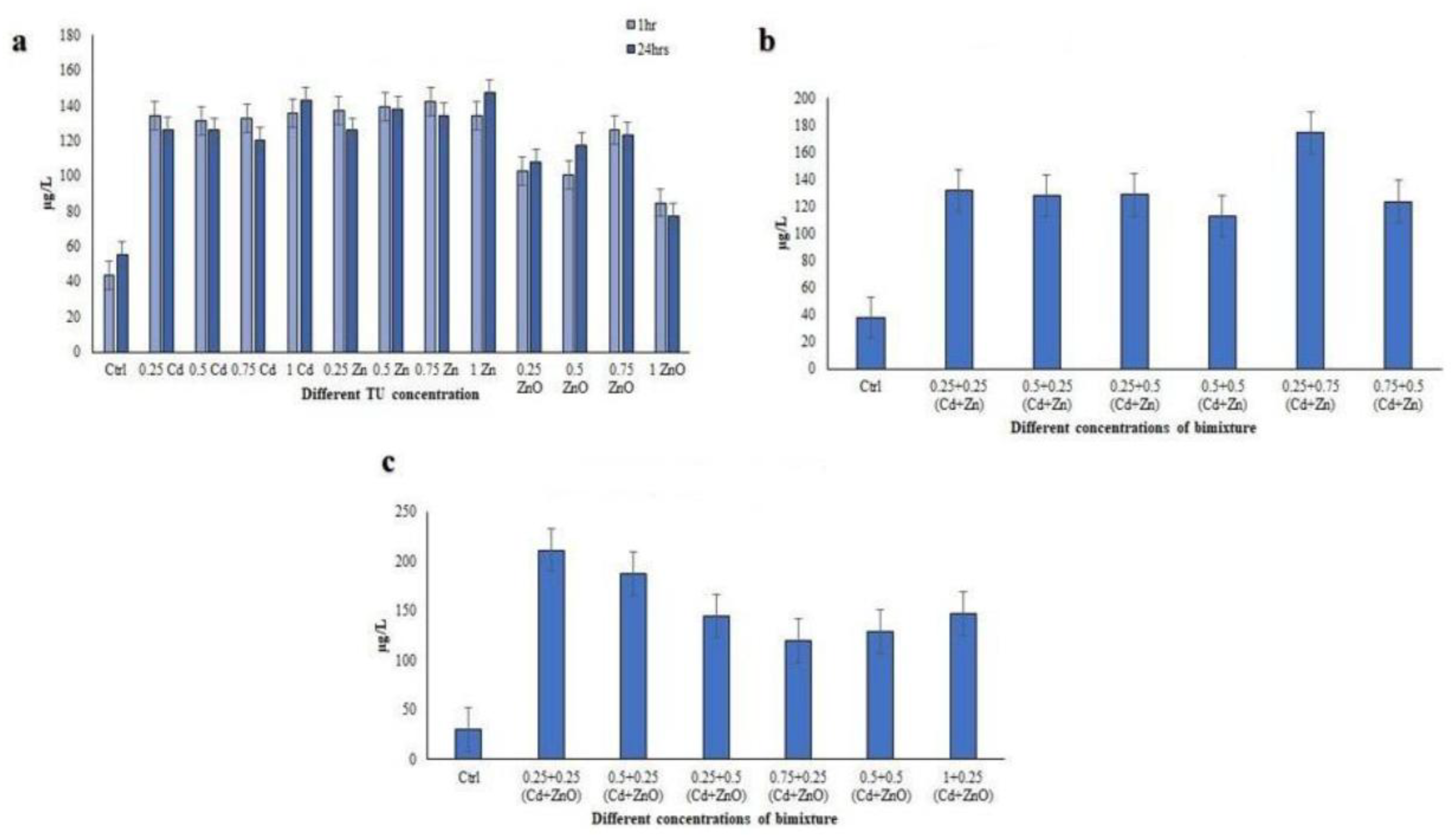

3.3.1. Total Phenolic Content (TPC)

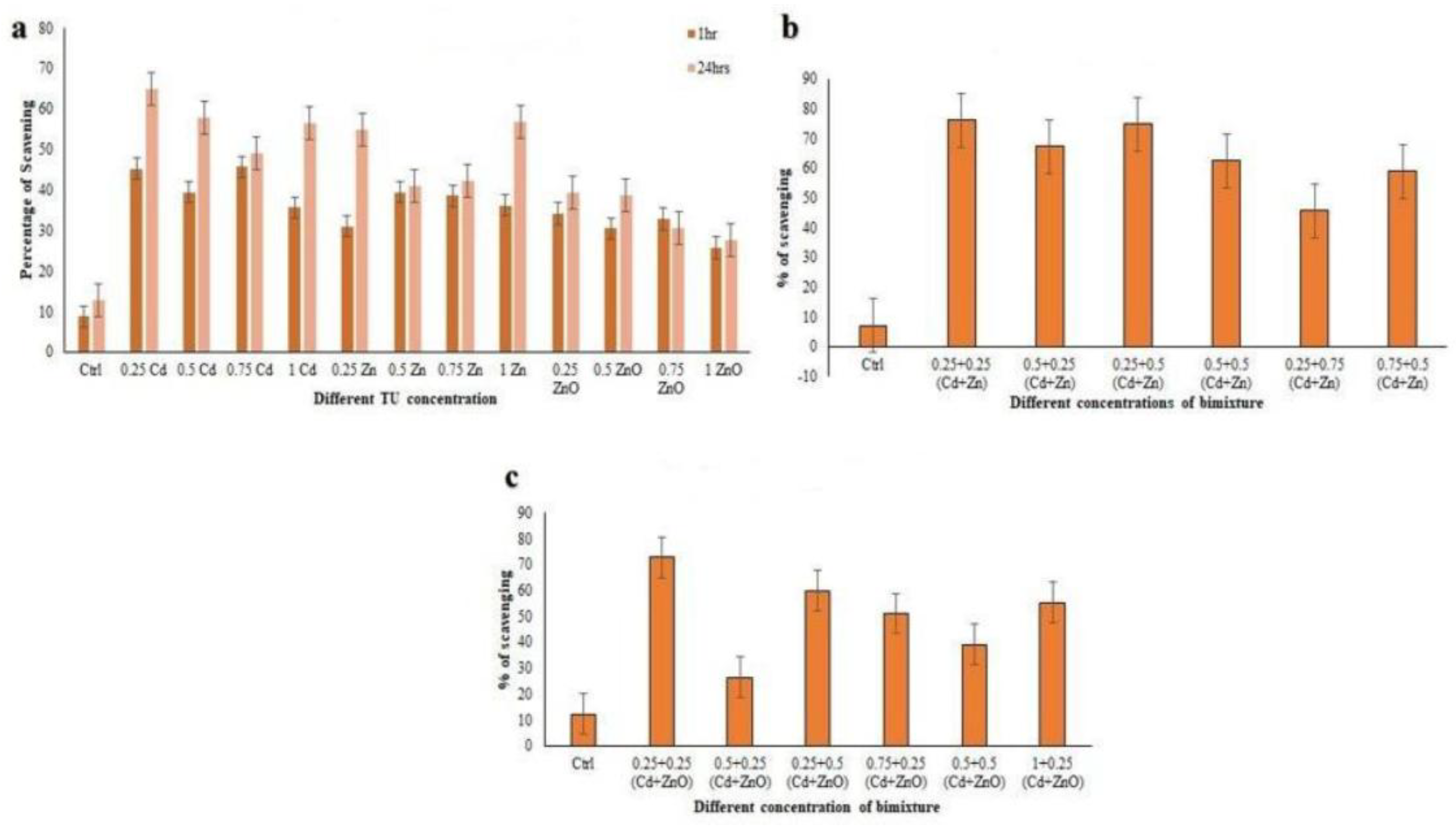

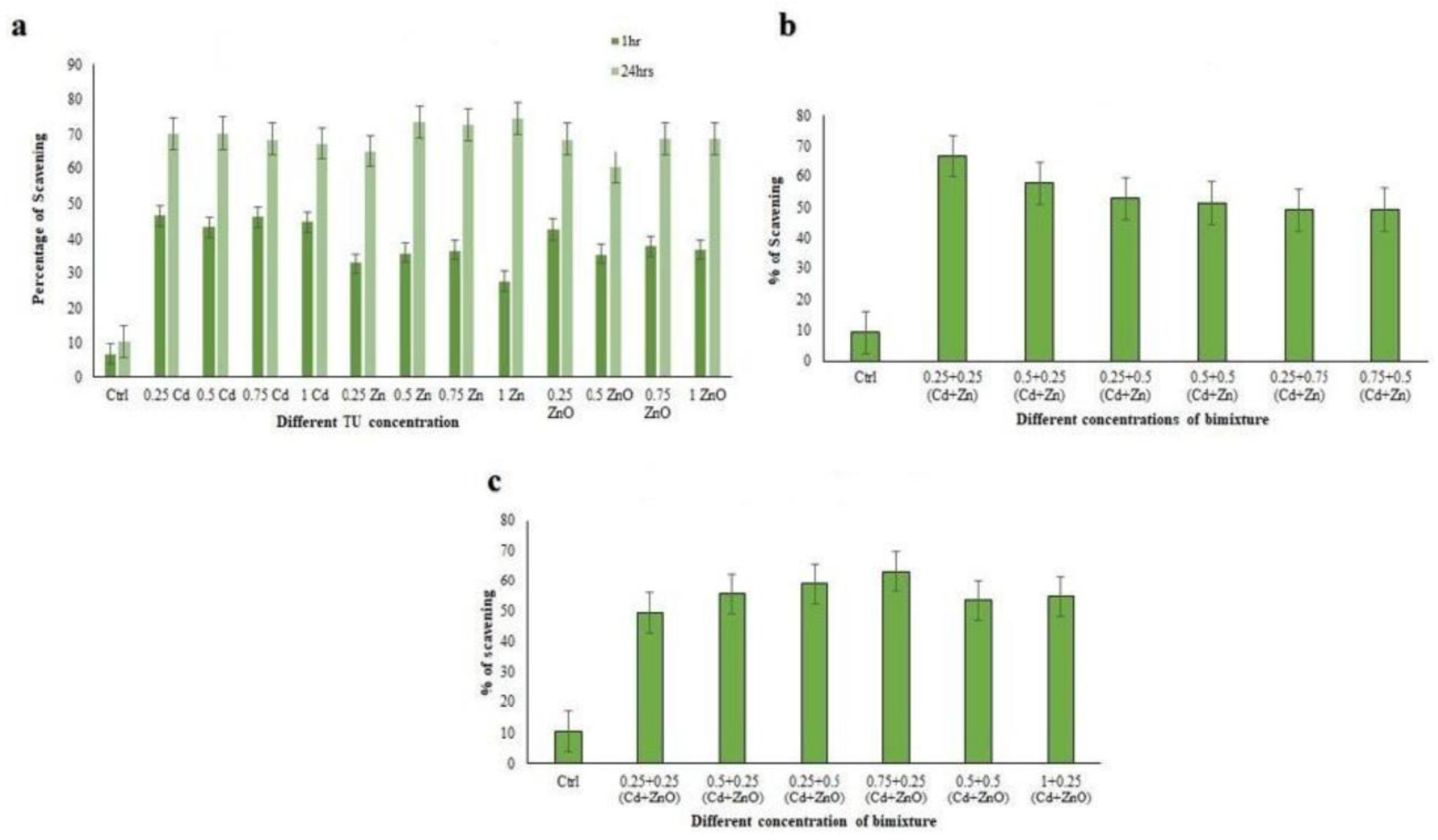

3.3.2. DPPH Radical Scavenging Activity

3.3.3. Hydroxyl Radical Scavenging Activity (HRSA)

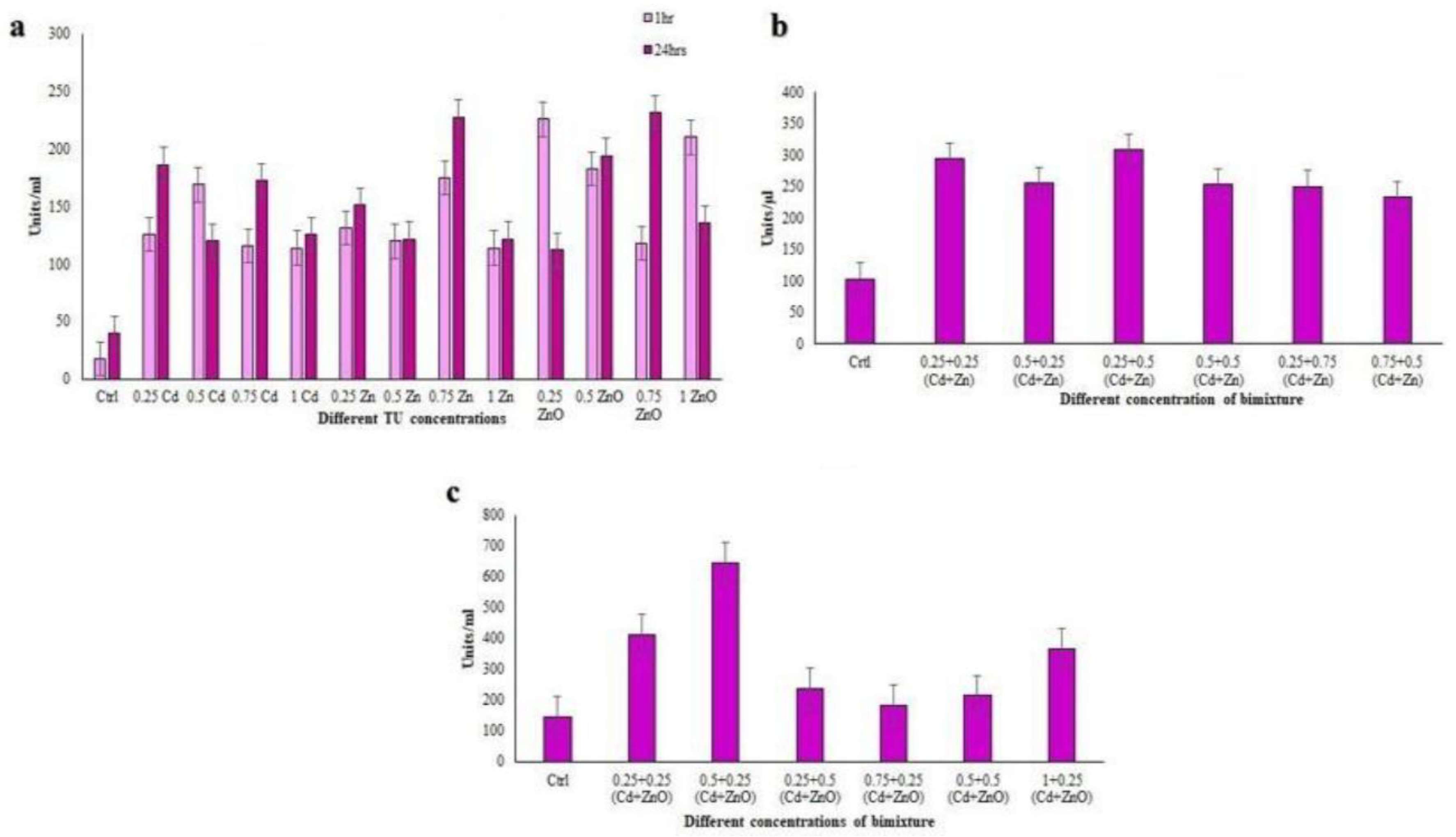

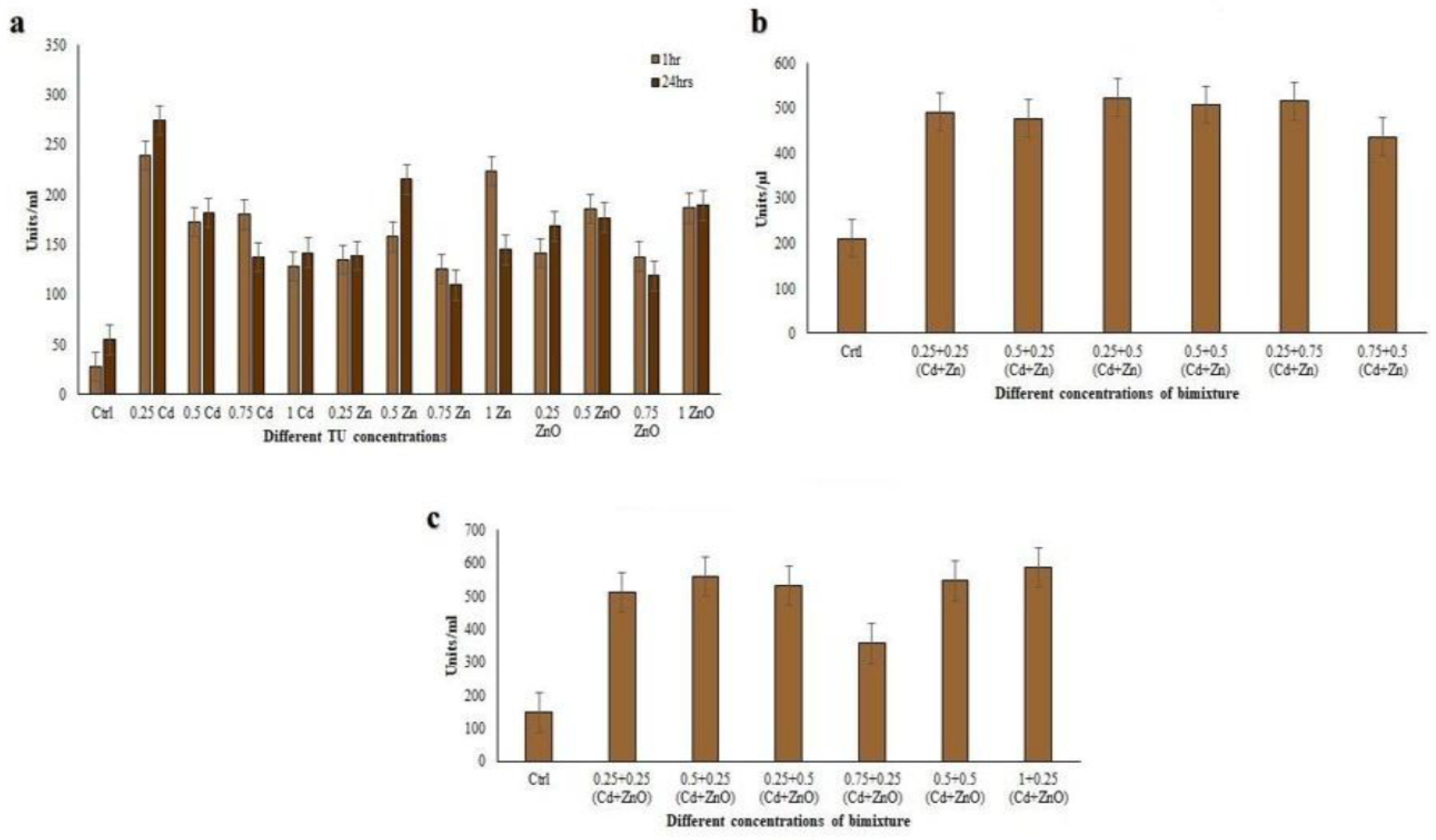

3.4. Antioxidant Enzyme Activities

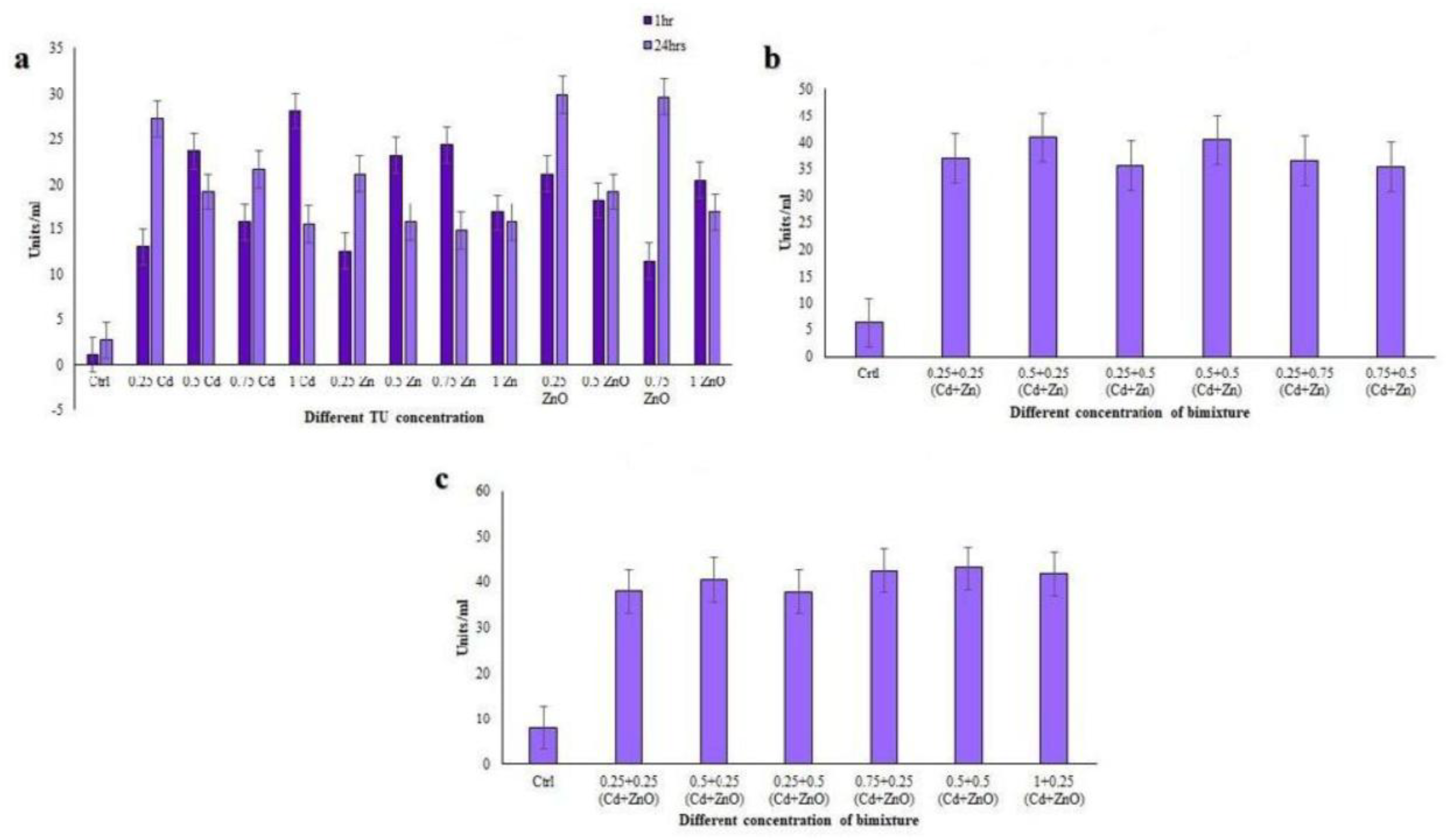

3.4.1. Catalase (CAT) Assay

3.4.2. Glutathione S-Transferase (GST) Assay

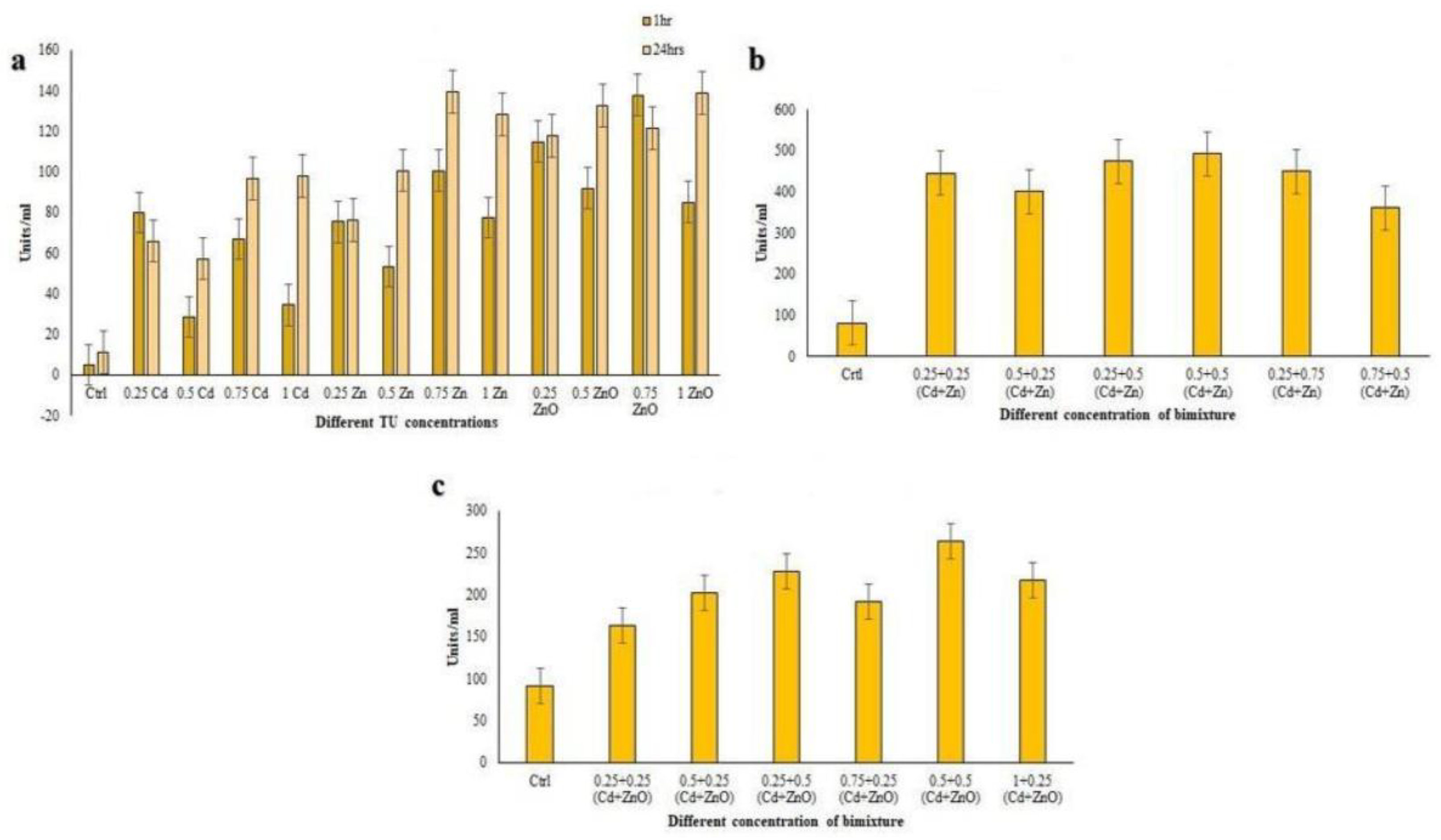

3.4.3. Guaiacol Peroxidase (GPx) Assay

3.4.4. Superoxide Dismutase (SOD) Assay

3.5. Correlation Analyses Among Antioxidant Responses

3.5.1. Correlations Among Non-Enzymatic Antioxidant Assays

3.5.2. Correlations Among Antioxidant Enzymes

4. Discussion

4.1. Toxicity Profiles of HMs and NPs

4.2. Mixture Toxicity: Antagonism in Cd + Zn vs. Synergism in Cd + ZnO

4.3. Antioxidant Responses as Biomarkers of Oxidative Stress

4.4. Coordination of Antioxidant Enzyme Responses under Mixture Stress

4.5. Ecotoxicological Relevance of Coleps hirtus and Implications for Biomonitoring

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mosleh, Y.Y.; Paris-Palacios, S.; Biagianti-Risbourg, S. Metallothioneins induction and antioxidative response in aquatic worms Tubifex tubifex (Oligochaeta, Tubificidae) exposed to copper. Chemosphere 2006, 64, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farkas, J.; Peter, H.; Ciesielski, T.M.; Thomas, K.V.; Sommaruga, R.; Salvenmoser, W.; Weyhenmeyer, G.A.; Tranvik, L.J.; Jenssen, B.M. Impact of TiO2 nanoparticles on freshwater bacteria from three Swedish lakes. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 535, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seebaugh, D.R.; Goto, D.; Wallace, W.G. Bioenhancement of cadmium transfer along a multi-level food chain. Mar. Environ. Res. 2005, 59, 473–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vardakas, P.; Kyriazis, I.D.; Kourti, M.; Skaperda, Z.; Tekos, F.; Kouretas, D. Chapter 6—Oxidative stress–mediated nanotoxicity: Mechanisms, adverse effects, and oxidative potential of engineered nanomaterials. In Advanced Nanomaterials and Their Applications in Renewable Energy, 2nd ed; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 179–218. ISBN 9780323998772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.N.; Desai, F.; Asmatulu, E. Engineered nanomaterials in the environment: Bioaccumulation, biomagnification and biotransformation. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2020, 18, 1073–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, E.; Kumar, V.; Kim, K.H.; Yip, A.C.; Sohn, J.R. Environmental impacts of nanomaterials. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 225, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Fan, W. Metal-based nanoparticles in natural aquatic environments: Concentrations, toxic effects and kinetic processes. Aquat. Toxicol. 2025, 286, 107454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ale, A.; Andrade, V.S.; Gutierrez, M.F.; Ayech, A.; Monserrat, J.M.; Desimone, M.F.; Cazenave, J. Metal-based nanomaterials in aquatic environments: What do we know so far about their ecotoxicity? Aquat. Toxicol. 2024, 275, 107069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Zhang, W.; Gao, H.; Li, Y.; Tong, X.; Li, K.; Zhu, X.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y. Behavior and potential impacts of metal-based engineered nanoparticles in aquatic environments. Nanomaterials 2017, 7, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varatharajan, G.R.; Calisi, A.; Kumar, S.; Bharti, D.; Ghosh, A.; Singh, S.; Kharkwal, A.C.; Coletta, M.; Dondero, F.; La Terza, A. Heavy Metals Affect the Antioxidant Defences in the Soil Ciliate Rigidohymena tetracirrata. J. Xenobiotics 2025, 15, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Beelen, P.; Doelman, P. Significance and application of microbial toxicity tests in assessing ecotoxicological risks of contaminants in soil and sediment. Chemosphere 1997, 34, 455–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foissner, W. Soil protozoa as bioindicators: Pros and cons, methods, diversity, representative examples. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 1999, 74, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madoni, P.; Romeo, M.G. Acute toxicity of heavy metals towards freshwater ciliated protists. Environ. Pollut. 2006, 141, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-González, A.; Díaz, S.; Borniquel, S.; Gallego, A.; Gutiérrez, J.C. Cytotoxicity and bioaccumulation of heavy metals by ciliated protozoa isolated from urban wastewater treatment plants. Res. Microbiol. 2006, 157, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Kim, S.J.; Lee, J.S.; Lee, Y.M. Acute effects of heavy metals on the expression of glutathione-related antioxidant genes in the marine ciliate Euplotes crassus. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2014, 85, 455–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, X.Y.; Xu, B.; Yu, C.P.; Zhang, H.W. Combined toxicity of ferroferric oxide nanoparticles and arsenic to the ciliated protozoa Tetrahymena pyriformis. Aquat. Toxicol. 2013, 134, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, W.-W.; Wang, Y.; Huang, B.; Wang, N.-X.; Wei, Z.-B.; Luo, J.; Miao, A.-J.; Yang, L.-Y. TiO2 nanoparticles act as a carrier of Cd bioaccumulation in the ciliate Tetrahymena thermophila. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 7568–7575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomiero, A.; Dagnino, A.; Nasci, C.; Viarengo, A. The use of protozoa in ecotoxicology: Application of multiple endpoint tests of the ciliate E. crassus for the evaluation of sediment quality in coastal marine ecosystems. Sci. Total Environ. 2013, 442, 534–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pudpong, S.; Chantangsi, C. Effects of Four Heavy Metals on Cell Morphology and Survival Rate of the Ciliate Bresslauides sp. Trop. Nat. Hist. 2015, 15, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-H.; Jung, M.-Y.; Lee, Y.-M. Effect of heavy metals on the antioxidant enzymes in the marine ciliate Euplotes crassus. Toxicol. Environ. Health Sci. 2011, 3, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foissner, W.; Berger, H.; Schaumburg, J. Identification and Ecology of Limnetic Plankton Ciliates; Informationsberichte des Bayerischen Landesamtes für Wasserwirtschaft: Ansbach, Germany, 1999; pp. 1–793. [Google Scholar]

- Pfister, G.; Auer, B.; Arndt, H. Community analysis of pelagic ciliates in numerous different freshwater and brackish water habitats. Verhandlungen Int. Ver. Theor. Angew. Limnol. 2002, 27, 3404–3408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazanec, A.; Trevarrow, B. Coleps, scourge of the baby Zebrafish. Zebrafish Sci. Monit. 1998, 5, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Bharti, D.; Kumar, S.; Buonanno, F.; Ortenzi, C.; Montanari, A.; Quintela-Alonso, P.; La Terza, A. Free living ciliated protists from the chemoautotrophic cave ecosystem of Frasassi (Italy). Subterr. Biol. 2022, 44, 167–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foissner, W. Infraciliatur, Silberliniensystem und Biometrie einiger neuer und wenig bekannter terrestrischer, limnischer und mariner Ciliaten (Protozoa: Ciliophora) aus den Klassen Kinetofragminophora, Colpodea und Polyhymenophora. Stapfia 1984, 12, 1–165. [Google Scholar]

- Sleigh, M. Protozoa and Other Protists; Edward Arnold: London, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto, E.; Sigaud-kutner, T.; Leitao, M.A.; Okamoto, O.K.; Morse, D.; Colepicolo, P. Heavy metal–induced oxidative stress in algae. J. Phycol. 2003, 39, 1008–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-H.; Jung, M.-Y.; Lee, Y.-M. Effect of heavy metals on the antioxidant enzymes in the marine ciliate Euplotes crassus. Toxicol. Environ. Health Sci. 2011, 3, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rico, D.; Martín-González, A.; Díaz, S.; de Lucas, P.; Gutiérrez, J.-C. Heavy metals generate reactive oxygen species in terrestrial and aquatic ciliated protozoa. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2009, 149, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valko, M.; Morris, H.; Cronin, M. Metals, toxicity and oxidative stress. Curr. Med. Chem. 2005, 12, 1161–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, S.S.; Bower, J.J.; Shi, X. Metal-induced toxicity, carcinogenesis, mechanisms and cellular responses. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2004, 255, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lister, K.N.; Lamare, M.D.; Burritt, D.J. Oxidative Damage in Response to Natural Levels of UV-B Radiation in Larvae of the Tropical Sea Urchin Tripneustes gratilla. Photochem. Photobiol. 2010, 86, 1091–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Song, J.; Yuan, H.; Xu, Y.; He, Z. Concentrations of cadmium and zinc in seawater of Bohai Bay and their effects on biomarker responses in the bivalve Chlamys farreri. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2010, 59, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, R.-O.; Rhee, J.-S.; Won, E.-J.; Lee, K.-W.; Kang, C.-M.; Lee, Y.-M.; Lee, J.-S. Ultraviolet B retards growth, induces oxidative stress, and modulates DNA repair-related gene and heat shock protein gene expression in the monogonont rotifer, Brachionus sp. Aquat. Toxicol. 2011, 101, 529–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehman, A.; Shakoori, F.R.; Shakoori, A.R. Heavy metal resistant freshwater ciliate, Euplotes mutabilis, isolated from industrial effluents has potential to decontaminate wastewater of toxic metals. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 3890–3895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomiero, A.; Dagnino, A.; Nasci, C.; Viarengo, A. The use of protozoa in ecotoxicology: Application of multiple endpoint tests of the ciliate E. crassus for the evaluation of sediment quality in coastal marine ecosystems. Sci. Total Environ. 2013, 442, 534–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-H.; Kim, S.-J.; Lee, J.-S.; Lee, Y.-M. Acute effects of heavy metals on the expression of glutathione-related antioxidant genes in the marine ciliate Euplotes crassus. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2014, 85, 455–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, G.; Erra, F.; Cionini, K.; Banchetti, R. Sublethal doses of heavy metals and Slow-Down pattern of Euplotes crassus (Ciliophora, Hypotrichia): A behavioural bioassay. Ital. J. Zool. 2003, 70, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonker, M.J.; Svendsen, C.; Bedaux, J.J.; Bongers, M.; Kammenga, J.E. Significance testing of synergistic/antagonistic, dose level-dependent, or dose ratio-dependent effects in mixture dose-response analysis. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. Int. J. 2005, 24, 2701–2713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyake, A. Physiology and biochemistry of conjugation in ciliates. Biochem. Physiol. Protozoa 1981, 4, 125–198. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, C.; Lee, J.; Soldo, A. Protocols in Protozoology; Lee, J.J., Soldo, A., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1992; D3. [Google Scholar]

- Brunelli, A.; Cazzagon, V.; Faraggiana, E.; Bettiol, C.; Picone, M.; Marcomini, A.; Badetti, E. An overview on dispersion procedures and testing methods for the ecotoxicity testing of nanomaterials in the marine environment. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 921, 171132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strober, W. Trypan blue exclusion test of cell viability. Curr. Protoc. Immunol. 2015, 111, A3.B.1–A3.B.3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sprague, J.B. Measurement of pollutant toxicity to fish. II. Utilizing and applying bioassay results. Water Res. 1970, 4, 3–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravindran, C.; Varatharajan, G.R.; Rajasabapathy, R.; Vijayakanth, S.; Kumar, A.H.; Meena, R.M. A role for antioxidants in acclimation of marine derived pathogenic fungus (NIOCC 1) to salt stress. Microb. Pathog. 2012, 53, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vattem, D.A.; Shetty, K. Solid-state production of phenolic antioxidants from cranberry pomace by Rhizopus oligosporus. Food Biotechnol. 2002, 16, 189–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, A.; Mavi, A.; Kara, A.A. Determination of antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of Rumex crispus L. extracts. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001, 49, 4083–4089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunchandy, E.; Rao, M. Oxygen radical scavenging activity of curcumin. Int. J. Pharm. 1990, 58, 237–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beers, R.F.; Sizer, I.W. A spectrophotometric method for measuring the breakdown of hydrogen peroxide by catalase. J. Biol. Chem. 1952, 195, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannervik, B.; Alin, P.; Guthenberg, C.; Jensson, H.; Tahir, M.K.; Warholm, M.; Jörnvall, H. Identification of three classes of cytosolic glutathione transferase common to several mammalian species: Correlation between structural data and enzymatic properties. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1985, 82, 7202–7206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyer, W.F.; Fridovich, I. Assaying for superoxide dismutase activity: Some large consequences of minor changes in conditions. Anal. Biochem. 1987, 161, 559–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Rienzo, J.A.; Casanoves, F.; Balzarini, M.G.; Gonzalez, L.; Tablada, M.; Robledo, C.W. InfoStat versión 2012. Grupo InfoStat, 2012 Facultad de Ciencias Agropecuarias, Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, Argentina. Available online: http://www.infostat.com.ar.

- Chung, K.T.; Wong, T.Y.; Wei, C.I.; Huang, Y.W.; Lin, Y. Tannins and human health: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 1998, 38, 421–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayyan, M.; Hashim, M.A.; AlNashef, I.M. Superoxide ion: Generation and chemical implications. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 3029–3085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varatharajan, G.R.; Calisi, A.; Kumar, S.; Bharti, D.; Dondero, F.; La Terza, A. Cytotoxicity and Antioxidant Defences in Euplotes aediculatus Exposed to Single and Binary Mixtures of Heavy Metals and Nanoparticles. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 5058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-González, A.; Díaz, S.; Borniquel, S.; Gallego, A.; Gutiérrez, J.C. Cytotoxicity and bioaccumulation of heavy metals by ciliated protozoa isolated from urban wastewater treatment plants. Res. Microbiol. 2006, 157, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortimer, M.; Kasemets, K.; Kahru, A. Toxicity of ZnO and CuO nanoparticles to ciliated protozoa Tetrahymena thermophila. Toxicology 2010, 269, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, S.; Martín-González, A.; Gutiérrez, J.C. Evaluation of heavy metal acute toxicity and bioaccumulation in soil ciliated protozoa. Environ. Int. 2006, 32, 711–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blinova, I.; Ivask, A.; Heinlaan, M.; Mortimer, M.; Kahru, A. Ecotoxicity of nanoparticles of CuO and ZnO in natural water. Environ. Pollut. 2010, 158, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glynn, A.W. The influence of zinc on apical uptake of cadmium in the gills and cadmium influx to the circulatory system in zebrafish (Danio rerio). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2001, 128, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barata, C.; Markich, S.J.; Baird, D.J.; Taylor, G.; Soares, A.M. Genetic variability in sublethal tolerance to mixtures of cadmium and zinc in clones of Daphnia magna Straus. Aquat. Toxicol. 2002, 60, 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fargašová, A. Winter third-to fourth-instar larvae of Chironomus plumosus as bioassay tools for assessment of acute toxicity of metals and their binary combinations. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2001, 48, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rainbow, P.; Amiard-Triquet, C.; Amiard, J.; Smith, B.; Langston, W. Observations on the interaction of zinc and cadmium uptake rates in crustaceans (amphipods and crabs) from coastal sites in UK and France differentially enriched with trace metals. Aquat. Toxicol. 2000, 50, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunda, W.G.; Huntsman, S.A. Antagonisms between cadmium and zinc toxicity and manganese limitation in a coastal diatom. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1996, 41, 373–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Párraga, P.; Hernández, J.A.; Argüelles, J.C. Role of antioxidant enzymatic defences against oxidative stress (H2O2) and the acquisition of oxidative tolerance in Candida albicans. Yeast 2003, 20, 1161–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estruch, F. Stress-controlled transcription factors, stress-induced genes and stress tolerance in budding yeast. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2000, 24, 469–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shakoori, F.R.; Zafar, M.F.; Fatehullah, A.; Rehman, A.; Shakoori, A. Response of Glutathione Level in a Protozoan Ciliate, Stylonychia mytilus, to increasing uptake of and Tolerance to Nickel and Zinc in the Medium. J. Zool 2011, 43, 569–574. [Google Scholar]

- Amaretti, A.; Di Nunzio, M.; Pompei, A.; Raimondi, S.; Rossi, M.; Bordoni, A. Antioxidant properties of potentially probiotic bacteria: In vitro and in vivo activities. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013, 97, 809–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fırat, Ö.; Cogun, H.Y.; Aslanyavrusu, S.; Kargın, F. Antioxidant responses and metal accumulation in tissues of Nile tilapia Oreochromis niloticus under Zn, Cd and Zn+ Cd exposures. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2009, 29, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| S. No: | Parameter | Estimate (± SE) | 95% Confidence Interval | R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heavy Metals | |||||

| 1 | Cu | LC20 | 0.87 ± 0.05 | 0.77–0.97 | 0.997 |

| LC50 | 1.62 ± 0.04 | 1.55–1.69 | |||

| 2 | Zn | LC20 | 8.26 ± 0.68 | 6.93–9.59 | 0.987 |

| LC50 | 20.42 ± 0.89 | 18.68–22.16 | |||

| 3 | Cd | LC20 | 1.47 ± 0.08 | 1.32–1.62 | 0.994 |

| LC50 | 2.75 ± 0.06 | 2.63–2.87 | |||

| Nanoparticles | |||||

| 1 | CuO | LC20 | 256.45 ± 15.32 | 226.43–286.47 | 0.996 |

| LC50 | 447.83 ± 11.94 | 424.43–471.23 | |||

| 2 | ZnO | LC20 | 138.72 ± 9.85 | 119.41–158.03 | 0.993 |

| LC50 | 356.18 ± 16.32 | 324.19–388.17 | |||

| 3 | TiO2 | LC20 | 6487.15 ± 462.25 | 5581.14–7393.16 | 0.995 |

| LC50 | 12879.33 ± 405.67 | 12084.22–13679.44 | |||

| 4 | SiO2 | LC20 | Up to 60080 mg L−1 there is no effects to the cells | ||

| LC50 | |||||

| CdCl2 + ZnSo4 Total TU a | Concentrations (TU) a for each compound CdCl2 ZnSo4 |

Obtained Cytotoxicity b | Expected Cytotoxicity | Interaction type | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 13.00 | ± | 3.04 | 15 | ± | 2.3 | Not significant different |

| 0.75 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 27.11 | ± | 1.62 | 29 | ± | 2.7 | Not significant different |

| 0.75 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 20.89 | ± | 1.27 | 26 | ± | 2.7 | Antagonism |

| 1 | 0.75 | 0.25 | 49.56 | ± | 2.60 | 46 | ± | 2.8 | Synergism |

| 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 34.00 | ± | 1.22 | 40 | ± | 2.8 | Antagonism |

| 1 | 0.25 | 0.75 | 35.44 | ± | 3.28 | 38 | ± | 2.8 | Not significant different |

| 1.25 | 0.75 | 0.5 | 42.56 | ± | 1.33 | 57 | ± | 2.6 | Antagonism |

| 1.25 | 0.5 | 0.75 | 56.67 | ± | 2.60 | 52 | ± | 2.6 | Synergism |

| 1.25 | 1 | 0.25 | 55.00 | ± | 2.80 | 62 | ± | 2.5 | Antagonism |

| 1.25 | 0.25 | 1 | 66.89 | ± | 2.52 | 53 | ± | 2.6 | Synergism |

| 1.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 72.67 | ± | 2.35 | 67 | ± | 2.3 | Synergism |

| 1.5 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 53.00 | ± | 1.00 | 69 | ± | 2.3 | Antagonism |

| 1.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 60.33 | ± | 1.58 | 73 | ± | 2.2 | Antagonism |

| 1.75 | 1 | 075 | 81.00 | ± | 2.12 | 85 | ± | 1.7 | Antagonism |

| 1.75 | 0.75 | 1 | 87.00 | ± | 2.74 | 84 | ± | 1.7 | Not significant different |

| 2 | 1 | 1 | 96.56 | ± | 2.60 | 100 | ± | 0.3 | Not significant different |

| CdCl2 + ZnO Total TU a | Concentrations (TU) a for each compound CdCl2 ZnO |

Obtained Cytotoxicity b | Expected Cytotoxicity | Interaction type | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 42.33 | ± | 1.94 | 8 | ± | 0.3 | Synergism |

| 0.75 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 51.67 | ± | 1.87 | 22 | ± | 1.0 | Synergism |

| 0.75 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 74.11 | ± | 1.45 | 22 | ± | 1.0 | Synergism |

| 1 | 0.75 | 0.25 | 67.44 | ± | 2.46 | 39 | ± | 2.1 | Synergism |

| 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 84.56 | ± | 1.42 | 36 | ± | 2.0 | Synergism |

| 1 | 0.25 | 0.75 | 100.00 | ± | 0.00 | 36 | ± | 2.0 | Synergism |

| 1.25 | 0.75 | 0.5 | 88.67 | ± | 1.00 | 53 | ± | 2.4 | Synergism |

| 1.25 | 0.5 | 0.75 | 100.00 | ± | 0.00 | 49 | ± | 2.4 | Synergism |

| 1.25 | 1 | 0.25 | 76.22 | ± | 2.11 | 55 | ± | 2.3 | Synergism |

| 1.25 | 0.25 | 1 | 100.00 | ± | 0.00 | 53 | ± | 2.4 | Synergism |

| 1.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 100.00 | ± | 0.00 | 67 | ± | 2.0 | Synergism |

| 1.5 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 100.00 | ± | 0.00 | 66 | ± | 2.0 | Synergism |

| 1.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 95.11 | ± | 1.27 | 69 | ± | 1.9 | Synergism |

| 1.75 | 1 | 075 | 100.00 | ± | 0.00 | 82 | ± | 1.3 | Synergism |

| 1.75 | 0.75 | 1 | 100.00 | ± | 0.00 | 84 | ± | 1.2 | Synergism |

| 2 | 1 | 1 | 100.00 | ± | 0.00 | 100 | ± | 0.2 | Not significant different |

|

C. hirtus CdCl2 + ZnSo4 |

Parameter | The Concentration Addition (CA) based module | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| exposures | CA | S/A | DR | DL | |

| 24 hr | a | – | 0.487 | 0.087 | 1.829 |

| b | – | – | 0.783 | 0.583 | |

| R2 | 0.88 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.91 | |

| p (χ2) CA vs. | – | 6.45E-07 * | 2.04E-06 * | 4.71E-09 * | |

| S/A vs. | – | – | 0.231 | 0.0002 * | |

| Parameter | The Independent action (IA) based module | ||||

| IA | S/A | DR | DL | ||

| 24 hr | a | – | -0.147 | -0.689 | -0.047 |

| b | – | – | 1.108 | -3.925 | |

| R2 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.91 | 0.93 | |

| p (χ2) IA vs. | – | 0.331 | 0.343 | 0.604 | |

| S/A vs. | – | – | 0.274 | 0.802 | |

|

C. hirtus CdCl2 + ZnO |

Parameter | The Concentration Addition (CA) based module | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| exposures | CA | S/A | DR | DL | |

| 24 hr | a | – | -1.986 | -5.702 | -0.820 |

| b | – | – | 7.118 | -1.705 | |

| R2 | 0.77 | 0.93 | 0.96 | 0.93 | |

| p (χ2) CA vs. | – | 2.2E-80 * | 5.5E-100 * | 7.99E-81 * | |

| S/A vs. | – | – | 8.36E-23 * | 0.003 * | |

| Parameter | The Independent action (IA) based module | ||||

| IA | S/A | DR | DL | ||

| 24 hr | a | – | -5.629 | -12.304 | -7.321 |

| b | – | – | 12.741 | 0.008 | |

| R2 | 0.33 | 0.92 | 0.96 | 0.90 | |

| p (χ2) IA vs. | – | 0.000 * | 0.000 * | 0.000 * | |

| S/A vs. | – | – | 7.75E-22 * | 1.03E-06 * | |

| Single-compound treatment 24 hr | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| TPC | DPPH | HRSA | |

| TPC | 1 | ||

| DPPH | 0.784 | 1 | |

| HRSA | 0.785 | 0.665 | 1 |

| Bimixture (Cd + Zn) 24 hr | |||

| TPC | DPPH | HRSA | |

| TPC | 1 | ||

| DPPH | 0.666 | 1 | |

| HRSA | 0.799 | 0.952 | 1 |

| Single-compound treatment 24 hr | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAT | GST | GPx | SOD | |

| CAT | 1 | |||

| GST | 0.364 | 1 | ||

| GPx | 0.565 | 0.5848 | 1 | |

| SOD | 0.490 | 0.151 | 0.194 | 1 |

| Bimixture (Cd + Zn) 24 hr | ||||

| CAT | GST | GPx | SOD | |

| CAT | 1 | |||

| GST | 0.945 | 1 | ||

| GPx | 0.884 | 0.938 | 1 | |

| SOD | 0.952 | 0.992 | 0.947 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).