Parenting practices profoundly influence child development and well-being. Positive parenting is associated with lifelong benefits across learning, social participation, employment, and quality of life (Boivin & Bierman, 2013). In contrast, harsh or intrusive parenting can have enduring negative effects on children and the parent-child relationship (Backhaus et al., 2023). Early socioemotional skills fostered by positive parenting support long-term psychological and social adjustment (Pulkkinen et al., 2011). However, parenting stress can undermine parenting behavior, with higher stress levels linked to harsher practices (Östberg & Hagekull, 2000). These challenges may be intensified for adolescent mothers, who frequently co-parent with their own caregivers (Berry et al., 2022), while navigating school progression, their own developmental needs, economic provision, and the social and emotional demands of parenting (Amongin et al., 2021; Branson et al., 2014). Supporting adolescent mothers is therefore critical to fostering positive parenting practices and promoting optimal child development.

Adolescent Motherhood and Family Well-Being

Adolescent mothers, defined as those aged 19 years or younger (World Health Organization, 2024), often become parents unexpectedly (Steventon Roberts et al., 2023), and face the dual challenge of undergoing their own cognitive, physical, and behavioral development while raising young children (DeVito, 2010; Kagawa et al., 2017). These pressures, compounded by demands of schooling, economic insecurity, and childcare (Amongin et al., 2021; Branson et al., 2014), are most acute in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) where adolescent childbearing is prevalent. In these settings, early motherhood is consistently associated with poorer health and well-being outcomes for both mothers (Amongin et al., 2021; Roberts et al., 2022), and children (Toska et al., 2022). Structural disadvantages—including low socioeconomic status, gender inequality, and early age—compound risk, leaving many adolescent mothers vulnerable to multiple deprivations and lifelong poverty (Kilburn et al., 2020).

Despite being one of the more vulnerable parenting populations (Li et al., 2020), adolescent mothers are regularly overlooked in policy and programming. While many interventions aim to prevent adolescent pregnancy or repeat pregnancy (Mohamed et al., 2023), few support adolescents to practice playful and effective parenting while addressing their own developmental, stress, and wellbeing needs (Ward et al., 2020). Parenting interventions have been shown to improve the health and wellbeing of children, mothers, and families (McCoy et al., 2020; Save the Children US, 2022), contributing to the Sustainable Development Goal to end all forms of violence against children (Backhaus et al., 2023). Parenting for Lifelong Health, for example, successfully reduced the risk of child maltreatment in a small-scale randomized controlled trial in South Africa (Lachman et al., 2017), and its adaptation for parents of teenagers included parenting skills alongside general life skills tailored for resource-constrained settings, covering topics such as positive parenting, conflict resolution, relationship building, community safety, finances, and stress management (Cluver et al., 2018; Mejia et al., 2017). Thula Sana, another South African intervention for parents of young children, enhanced maternal sensitivity and mother-infant bonding, and its adaptation piloted in El Salvador for adolescent parents improved maternal responsivity, resulting in better regulated child behaviour and social orientation (Boivin & Bierman, 2013). These findings highlight the potential of targeted parenting interventions to improve outcomes for adolescent mothers and their children.

Study Aims

This study examines adolescent mothers’ parenting experiences as indicators of family relational well-being in the Eastern Cape, South Africa, and how these indicators are associated with young children’s cognitive development. Prior research shows that parenting stress is shaped by child characteristics, family relationship quality, parental mental health, and household resource constraints in both adolescent and adult parent populations (Anderson, 2008; Louie et al., 2017). Supportive intergenerational caregiving and open caregiver–adolescent communication may buffer stress and facilitate more engaged parenting practices. Understanding parenting stress and parenting activities among adolescent mothers is therefore critical for designing developmentally appropriate, two-generation interventions to protect mother and child outcomes. In this study, we assessed levels of parenting stress, mothers’ engagement in playful and responsive parenting activities, factors associated with completing these activities, and how the frequency and enjoyment of parenting interactions relate to children’s cognitive developmental.

Methods

Study Design and Setting

Adolescent and young mothers (11-24 years, who had their first child at 19 or younger) and their children (3-96 months) were recruited between 2017-2019 for the HEYBABY longitudinal cohort study in the Eastern Cape, South Africa (Toska et al., 2022). This province has high numbers of adolescent childbearing, with 1.2 births per 1000 for 10–14-year-olds and 57.1 per 1000 for 15–19-year-olds (Barron et al., 2022). Additionally, 12.7% of the Eastern Cape population live in multidimensional poverty - the highest provincial rate in the country - across indicators of health, education, living standards, and economic activity (South Africa Gateway, 2017). The province is predominantly isiXhosa

This study utilises data from 931 adolescent mothers aged 12–23 years at baseline and their young children aged 0-6 years (Toska et al., 2022). One quarter (25%, n=233) had been pregnant before the age of 16 years. Approximately 13% of adolescents aged 18 years or older had additional children. One quarter were living with HIV (27%, n=251) and 29% (n=270) lived in rural areas. Additionally, 33% were not in school or had not completed school.

Most adolescent mothers (94%; n=875), lived with their biological parents or other female relatives. Very few (6%; n=56) lived with other male relatives or caregivers, with their partner or alone. Three quarters (77%; n=717) of adolescents said that they were anxious or careful about what they say to their caregivers and most (94%; n=875) reported strong house rules and social monitoring. Approximately 29% (n=875) reported that their caregiver always or almost always rewarded them for positive behaviour.

Most homes (93%; n=866) received at least one welfare grant, although 7% did not receive any. Approximately 71% of adolescent mothers (n=661) reported that they were food secure with three meals per day for the past week. Almost no adolescents (n=6) reported frequent drug or alcohol use (to the extent that it affected walking, talking, or remembering). Very few reported domestic violence or arguments (7%; n = 65) or other types of violence or abuse.

Data Collection

Data was collected using a validated and study specific questionnaire. The questionnaire was presented on a tablet, allowing adolescents to answer sensitive questions privately. Field researchers, fluent in both English and the local language isiXhosa, were trained to collect data from children and adolescents. The questionnaire and consent forms were translated from English into isiXhosa - the language most spoken in the study area.

The child cognitive development data were collected by trained research assistants supported by a psychologist; data were collected via paper-and-pen scoring and later captured electronically. Other child measures were completed by mothers as part of their questionnaire.

Quality control measures were in place to ensure uniformity in translation and presentation of items. Interviews lasted between 60 to 90 minutes, and adolescents completed a battery of validated and study-specific questionnaires (available at

www.heybaby.org). Adolescent mothers and their children were mainly assessed in their own homes. A nearby community venue was used in the case of the home not being suitable. A trained Teen Advisory Group consulted on recruitment and data collection tools.

Scales and Measures

The scales and measures used are summarized here with additional material including scale references, adaptation notes, scoring notes, sample mean, SD and range available in the Supplementary Data (

Table S1). Where items are developed by the study team, they were done so in collaboration with a Teen Advisory Group and piloted before inclusion. Demographic variables included maternal age (years), education level (grade completed) and number of children and age at first pregnancy.

Adolescent Mother-Caregiver Relationship

Communication with caregivers was assessed using five items from the Child-Parent Communication Apprehension Scale for Young Adults (C-PCA, YA) (Lucchetti et al., 2002), reduced after piloting due to translation issues. Four items loaded together in factor analysis, while a single item, “I am anxious or careful talking to my caregiver,” was retained separately, as it was culturally understood to represent respectful rather than apprehensive communication (Supplementary Data

Table S2). Two subscales from the Alabama Parenting Questionnaire (APQ) were included: Positive Parenting (six items; high score indicates affirming words, actions, rewards) and Parental Monitoring (10 items; high score indicates poor monitoring) (Kyriazos & Stalikas, 2019).

Psychosocial Variables

The breadth of social support was assessed via the number of people helping buy things for the child, using an item developed by the study team. Food insecurity was measured using by one item from the South African National Food Consumption Survey (Labadarios et al., 2005). Any violence or abuse experiences were measured by two items from the UNICEF Measures for National-level Monitoring of Orphans and Other Vulnerable Children, (Snider & Dawes, 2006). Experiences of any poor mental health symptoms (anxiety, depression, suicidality, post-traumatic stress disorder); were measured using items from the Child Manifest Anxiety Scale (Reynolds & Richmond, 1985), Child Depression Inventory (Kovacs, 1992), Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview for Children and Adolescent (Mini-KID) (Sheehan et al., 2010) and the Child PTSD Checklist (Donnelly & Amaya-Jackson, 2002). Any early childhood development (ECD) access for pre-schoolers was measured with an item developed by the study team.

Child Measures

Child temperament was mother-reported using the 12 items in the Emotionality, Activity and Shyness scale – short form (Buss & Plomin, 2014), which measures child temperament across four dimensions: shyness (fear), emotionality (irritability and anger), sociability (positive affect and approach), activity (activity level). A high score on a domain indicates more of the temperament being measured, i.e. overly shy/fearful, emotional/irritable and active indicating potentially challenging child behaviours, and overly sociable indicating a potentially attractive child behaviour. The scale is predominantly tested in North American contexts with few examples in LMICs, however, there is one LMIC example where the scale was used to document temperament and happiness in children in India (Holder et al., 2012). The validity and reliability of parent reports are consistently found to be good (Masi et al., 2003).

The mother-reported World Health Organisation (WHO) disability screener assessed physical and cognitive disabilities by comparing children to age peers. It is validated across diverse settings, including South Africa (Christianson et al., 2002) and Kenya (Lorencz & Boivin, 2013; Singhi et al., 2007).

The Mullen Scales of Early Learning (MSEL) are published by Pearson Assessments and purchased locally through Mindmuzik. The MSEL offers a well-validated and reliable measure of early childhood development for children aged 3-68 months (Mullen, 1995) and has been extensively used in resource-scarce LMICs, including South Africa and other countries in sub-Saharan Africa (Boivin et al., 2019; Milosavljevic et al., 2019). The MSEL assesses gross motor, fine motor, visual reception, expressive language, and receptive language domains, providing T-scores, percentile ranks, and age equivalents for each scale (Mullen, 1995).

Parenting Experiences

Parenting stress and enjoyment were assessed using six stress and two enjoyment items from the 18-item Parenting Stress Scale (PSS) (57; used with permission) . This scale is widely used across LMIC contexts including Pakistan (Gulamani et al., 2013) and China (Cheung, 2000), with strong cross-cultural performance (Louie et al., 2017). Items were reduced based on pilot feedback as some of the nuances in the items were lost in translation. Stress scores ranged from 6–30, with higher scores indicating greater stress. Enjoyment scores ranged from 2–10, with higher scores indicating greater enjoyment.

Parenting practices were self-assessed using 15 items from the PARYC scale (61; used with permission), reduced from 21 items to minimise interview fatigue while retaining reliability (Lester, 2015). The scale measures items over three domains: supporting good behaviour, setting limits, and proactive parenting, rated from never (0) to almost daily (3), or my child is too young, with scores ranging from 0–45. Scores were categorised into bins based on interquartile ranges, combining the middle 50% because of low variation in these quartiles: Bin 1 (0–8) indicated none or few infrequent activities (n=109, mean MSEL=156), Bin 2 (9–23) some activities on some days (n=199, mean MSEL=165), and Bin 3 (24–24) most activities on most or all days (n=153, mean MSEL=174) (Supplementary Data

Table S3).

Ethical Considerations

Ethics approvals were obtained from the Universities of Oxford (R48876/RE001-2, SSD/CUREC2/12-21) and Cape Town (HREC 226/2017, CSSR 2013/4), Eastern Cape Departments of Health and Basic Education, and participating health and educational facilities. Adolescents who reported violence or abuse were referred to appropriate services following predetermined study protocols. Further data collection and recruitment strategy are described elsewhere (Toska et al., 2022).

Voluntary informed consent was obtained from adolescent mothers and their caregivers where adolescents were under 18 years of age. Adolescents received a snack and small gift back with toiletries, stationery, and toys for their children.

Data Analysis

Data analysis was conducted using STATA-18. Analyses proceeded in sequential stages, beginning with psychometric validation of the parenting measures (adjusted scales are reported in the Supplementary Data (

Tables S2 & S4). This was followed by descriptive and inferential statistics to examine sample characteristics, described above.

Bivariate and multivariate hierarchical analysis was used to model variation in parenting stress. Multivariate linear regression models were nested by categories of variables grouped by demographic, caregiver-adolescent mother relationship, psychosocial and child-oriented variables. The post-hoc F-test was used to confirm that models were significantly different from each other.

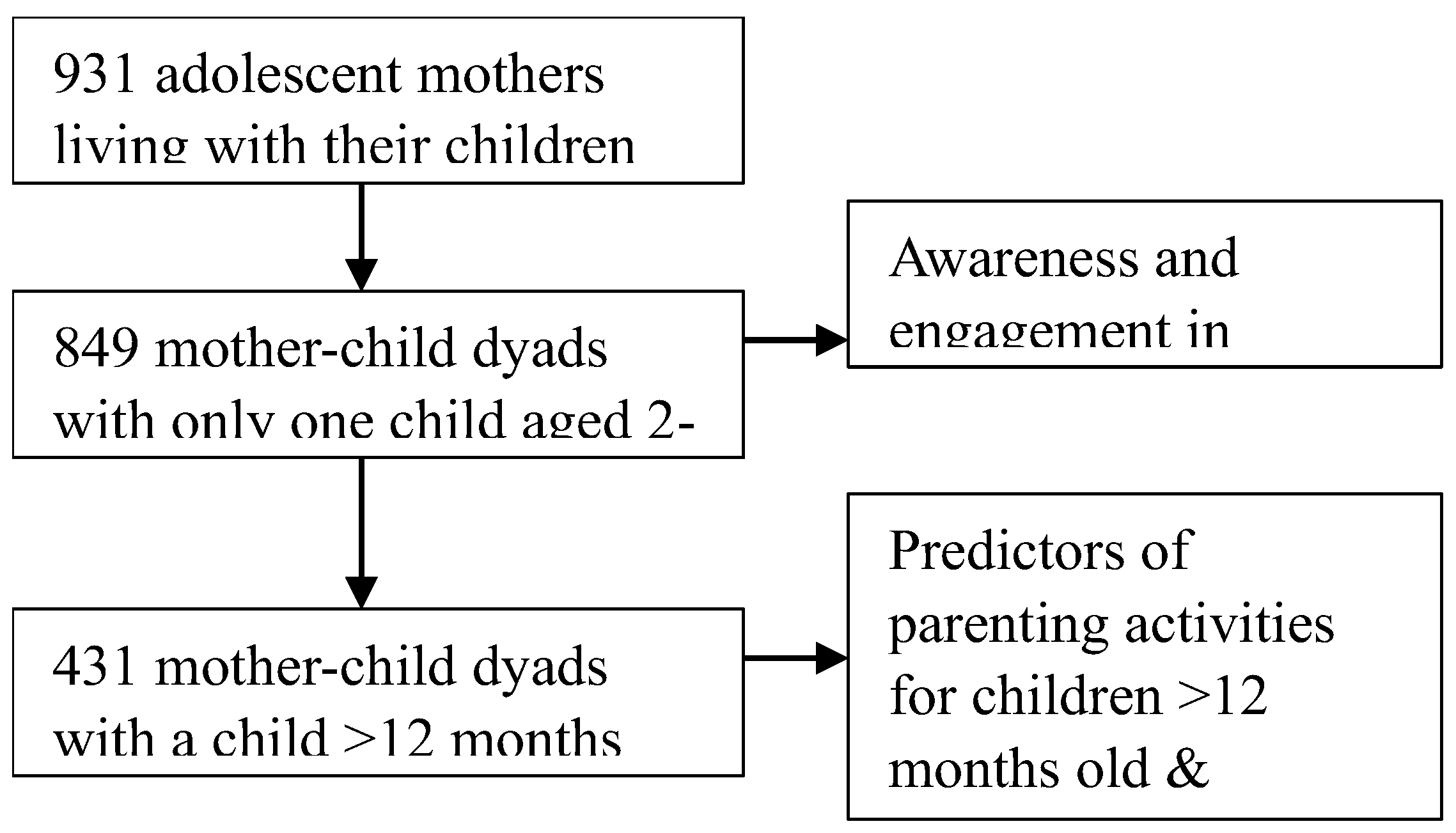

Data analysis for the PARYC scale consisted of three stages (

Figure 1). First, we restricted the participants to mothers who had only one child (n=849) and reshaped the PARYC dataset to identify the youngest child age at which at least 80% of mothers considered the parenting activity age appropriate. We further restricted the par to only include children within the MSEL recommended age range (2-68 months), resulting in 461 children. Finally, for activities deemed age appropriate, responses of “my child is too young” were recoded as “never” completing the activity.

Next, we examined the structure of the scale to prepare it for regression analysis. This included assessing inter-item correlations and removing items with correlation coefficients above 0.8 (Supplementary Data,

Table S5). We conducted factor analysis to eliminate redundant items and refine the scale (Supplementary Data,

Table S6).

We used hierarchical linear regression analysis to model the nested variables that contribute to mothers completing activities using the PARYC at the outcome. Variable groups were: 431 mother-child dyads were selected based on the age of their child and the number of children they had (Figure I). The post-hoc F-test was used to confirm that additional nested sets of variables significantly improved the mode.

Finally, we used a one-way ANOVA with a Bonferroni correction (Bland & Altman, 1995) to identify significant differences in MSEL composite scores between mothers who frequently completed all age-appropriate activities and mothers who sometimes or never completed the activities. Cohen’s d (d) was used to determine the effect size of the difference between activity completion groups.

Results

What Protects from and What Contributes to Adolescent Mother Parenting Stress? (n=931)

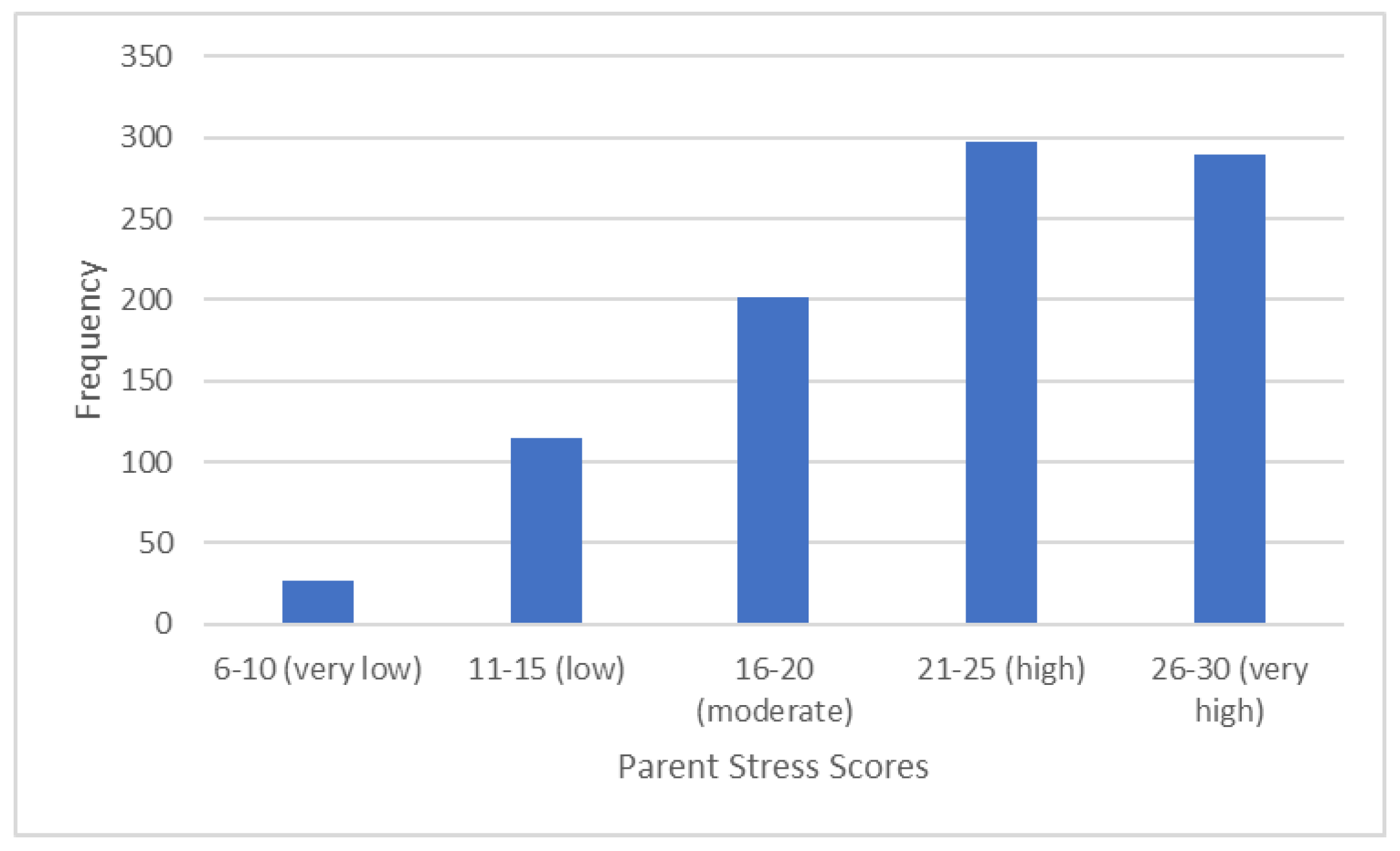

Approximately 63% of adolescents agreed or strongly agreed with the parenting stress items (mean = 22.2, SD = 5.9) (

Figure 2).

Parenting stress among adolescent mothers was shaped by a combination of relational, psychosocial, and child-related factors. Overall, parenting stress was most strongly related to whether children were calm or crying and the quality of relationship between the adolescent mothers and her own mother or caregiver. Bivariate regressions are detailed in the Supplementary Data (

Table S7). Multivariate models examined how adolescent mothers, their children, caregivers, and psychosocial contexts shape parenting stress (

Table 1).

In Model 1, older adolescents reported slightly higher stress, though the variance explained was minimal. Adding adolescent–caregiver relationship variables in Model 2 significantly improved model fit, F(3, 889) = 40.04, p < .001, and explained 12.4% of the variance; anxious communication predicted higher stress, while positive parenting predicted lower stress. Psychosocial variables in Model 3 increased explained variance to 16.9%, F(3, 879) = 16.12, p < .001; anxious communication remained significant, and food insecurity and mental distress were associated with higher stress, whereas access to childcare predicted lower stress. Model 4 added child- and parenting-related variables, raising explained variance to 24.6%, F(2, 871) = 44.53, p < .001; fewer crying children predicted lower stress, and child disability predicted higher stress. A final parsimonious model (Model 5) explained 33.9% of the variance, F(7, 376) = 27.50, p < .001. Standardized coefficients indicated the strongest predictors of higher parenting stress were child-related stress (β = –.44), number of children (β = .26), anxious communication (β = .18), lower food security (β = –.18), and lower parenting enjoyment (β = .15).

Which Parenting Activities Are Adolescent Mothers Engaging In? (n=849)

Table 2 provides a summary of awareness and involvement in each parenting activity. The most frequently completed activities are the playful activities of playing in a way that is fun for both (80%), making a game out of everyday tasks (80%), and inviting your child to play a game with you or share an enjoyable activity (66%). Over the three domains, adolescent mothers were most likely to be aware of, and engaged in, the activities in the sub-scale “supporting good behaviours". The frequent completion of playful activities was an unexpected and welcome finding in understanding adolescent parenting, clarifying H2. The activities on this scale were also identified by participants as being appropriate for younger children (aged 5-11 months). Mothers were less aware and less likely to be engaged, even if aware, in activities on the sub-scales “Setting Limits” and “Proactive Parenting” which were identified as being appropriate for older children (from 11-12 months).

Which Adolescent Mothers Are more Likely to Frequently Complete Parenting Activities? (n=431)

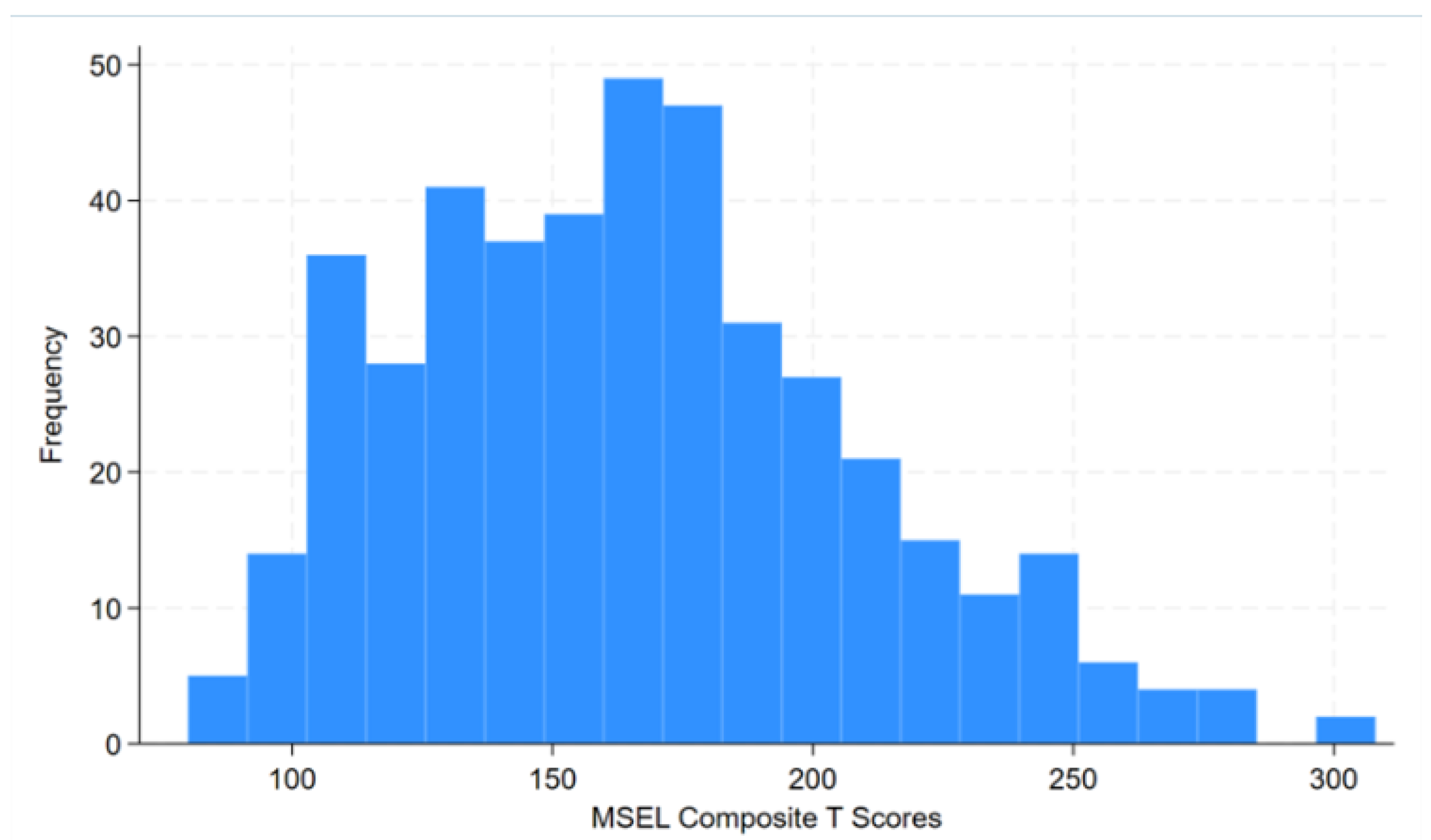

The MSEL distribution is reported here for the restricted participant analysis (n=431) of children over 12 months and who are the only child in the family, explained in the methods above. Full sample scores are published in previous research (Steventon Roberts et al., 2023). MSEL Composite T Scores were right-skewed, with most scores clustering between approximately 120 and 190 (

Figure 3). The most frequent score range fell between 160 and 180, with a mean of 166. Fewer children scored at the lower (<100) and higher (>250) end of the distribution, indicating that extreme scores were relatively uncommon amongst these participants.

Adolescent mothers who enjoy their children, have emotionally regulated children and have supportive caregiver relationships engage in more frequent parenting activities. We examined factors associated with frequent completion of parenting activities among mothers of children aged 12-68 months using hierarchical linear regression. Overall, the final model explained 35% of the variation in parenting activities, (

Table 3). Bivariate analysis is available in the Supplementary Data (

Table S8).

Age was a significant but weak predictor of parenting activity, accounting for only 1% of the variance, F(1, 892) = 5.47, p = .02 (Model 1). Adding caregiver–adolescent relationship variables in Model 2 significantly improved model fit, F(3, 427) = 22.76, p < .001, and explained 11% of the variance; less anxious communication and higher communication quality were associated with greater parenting activity (Model 2). Psychosocial variables further increased explained variance to 18%, F(3, 421) = 11.19, p < .001; communication quality and adolescent anxiety remained significant, and less help buying necessities and access to ECD services predicted higher parenting activity, whereas food security was no longer significant (Model 3). Child-related variables increased explained variance to 30%, F(5, 416) = 14.74, p < .001. More social and less emotional children showed higher parenting activity, child shyness was negatively associated, and child cognitive development and access to ECD remained significant predictors (Model 4). In Model 5, parenting stress and parenting enjoyment significantly improved model fit, F(2, 416) = 21.49, p < .001, increasing explained variance to 35%; both were positively associated with parenting activity, alongside caregiver communication, access to ECD, and child cognitive and emotional functioning. The final parsimonious Model 6 retained key predictors and maintained 35% explained variance. Standardized coefficients indicated that parenting enjoyment (β = .22) and positive caregiver communication (β = .15) were the strongest positive predictors, and lower child emotionality was associated with higher parenting activity (β = –.24).

Does the Completion of Parenting Activities Support the Cognitive Development of the Child? (n=431)

The analysis examined whether the frequency with which mothers engaged in parenting activities was associated with their child’s cognitive development, as measured by the MSEL. A one-way ANOVA was conducted to examine whether the frequency of parenting activities was associated with child cognitive development, as measured by MSEL scores. Results indicated that children whose mothers frequently engaged in most or all parenting activities scored significantly higher on the MSEL than those whose mothers never or almost never engaged (p=0.001). Children appear to benefit cognitively from parenting interactions.

Interestingly, children whose caregivers only sometimes engaged in some of the activities did not differ significantly from either the low-engagement or high-engagement groups. This suggests that irregular or partial participation in parenting activities may not be sufficient to provide meaningful cognitive benefits.

The effect size for the difference between the low- and high-engagement groups was small to moderate (d=0.48), indicating that consistent completion of parenting activities was associated with a meaningful advantage in cognitive scores. Although not a large effect, this is meaningful in the context of child development, where even modest gains in cognitive scores can translate into substantial developmental advantages over time. Levene’s test indicated no significant difference in variance between groups (χ²(2)=1.35), supporting the robustness of the observed association. This indicates that the observed differences were not simply due to unequal spread or variability in the data but reflect a genuine association between parenting practices and child cognitive development.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study globally to explore how adolescent mothers in low-resource contexts experience parenting young children. We identified factors contributing to or alleviating parenting stress, assessed awareness of age-appropriate parenting activities and the frequency of engagement, and examined the association between parenting activities and children’s cognitive development. Findings indicate that adolescent mothers are not a homogenous group; they display a wide range of experiences, awareness, and engagement in parenting practices while simultaneously navigating the challenges of their own developmental stage. These insights can inform the design of targeted interventions for adolescent mothers to benefit themselves and their children.

Parenting challenges are amplified by poverty. Families living in poverty face increased risk for family and community violence, limited access to childcare and early child development programs, health and nutrition challenges, and mental health problems (Beasley et al., 2022). These factors negatively affect child development, often leading to socioemotional and cognitive delays that may co-occur with behavioural problems, further increasing parental strain. Poverty undermines parental sensitivity and responsiveness and is associated with harsh parenting practices and insecure parent-child attachment (Wray, 2015). For adolescent mothers, interventions must address the effects of food insecurity on the entire household and should incorporate guidance on accessing community support services and developing family budgeting plans.

What Protects from, and What Contributes to, Adolescent Mother Parenting Stress?

Higher parity contributed to increased parenting stress among adolescent mothers, even when economic variables were controlled for. This finding underscores the need to incorporate family planning into adolescent parenting interventions. Adolescents with repeat pregnancies need more support than first time mothers. This is likely counter-intuitive compared to adult populations where first-time mothers tend to need more support than more experienced mothers (Lagerberg & Magnusson, 2013).

Adolescents who felt anxious or cautious when communicating with their caregiver experienced significantly higher stress levels, while positive communication with caregivers reduced adolescent parenting stress. Effective communication between caregivers and adolescents is a key component of adolescent mother parenting interventions, as it both reduces stress and increases adolescent engagement and frequency of parenting activities. Given the likely co-parenting nature of the family unit, any new parenting skills taught to adolescents should also be taught to their caregivers to ensure consistency for the child. Open and comfortable communication can facilitate this alignment and further decrease parenting stress. Parenting stress was reduced by having more people contributing to the purchase of food and clothing for the child. This indicates the importance of building supportive social structures to attenuate parent stress.

Contrary to findings in previous literature, (Anderson, 2008; Louie et al., 2017), individual psychosocial factors—including drug and alcohol use, mental illness, exposure to domestic violence or arguments, and exposure to abuse—did not significantly contribute to parenting stress or parenting activities in this study. However, some of these variables affected only small numbers of adolescents, possibly leading to these variables not being significant. Mental illness was significantly associated with parenting stress in the bivariate analysis but not in the nested multivariate regression when economic and child-oriented factors were included. This finding emphasizes the relative importance of psychosocial and child behavior factors in understanding adolescent mother parenting stress.

Finally, child-oriented and adolescent parent variables—including crying, disability, and parenting enjoyment—were all significant in the multivariate regression, highlighting the importance of the parent-child relationship in adolescent experiences of parenting stress. The absence of child crying significantly reduced parenting stress when other variables were held constant. Adolescent parenting programs should therefore aim to build skills for managing difficult child behaviors while also fostering positive affect through playful parenting, making parenting a more rewarding experience. This recommendation aligns with Berry and Jones’s theory that the overall parenting experience consists of a cost-benefit balance between stress and enjoyment (Berry & Jones, 1995). Overall, these findings underscore the complex interplay of child characteristics, caregiver relationships, and household resources in shaping adolescent parenting stress.

Which Parenting Activities Are Adolescent Mothers Engaging In?

Adolescent mothers in this study were most aware of, and engaged in, playful parenting activities, such as playing in ways that are enjoyable for both mother and child. Eighty percent reported doing this activity daily, and only 4% were unaware that it is an age-appropriate activity. Awareness and engagement in playful activities provide a strong foundation for positive parent–child relationships and are a key component of effective parenting (Leijten et al., 2022; World Health Organization, 2022). In contrast, adolescent mothers demonstrated lower awareness and engagement in setting limits and proactive parenting. For example, only 40% reported setting consistent rules daily; additionally, 18% were unaware that this was an age-appropriate practice. Parenting interventions for adolescent mothers should therefore incorporate skill-building in limit-setting and proactive strategies to improve parenting enjoyment and child outcomes.

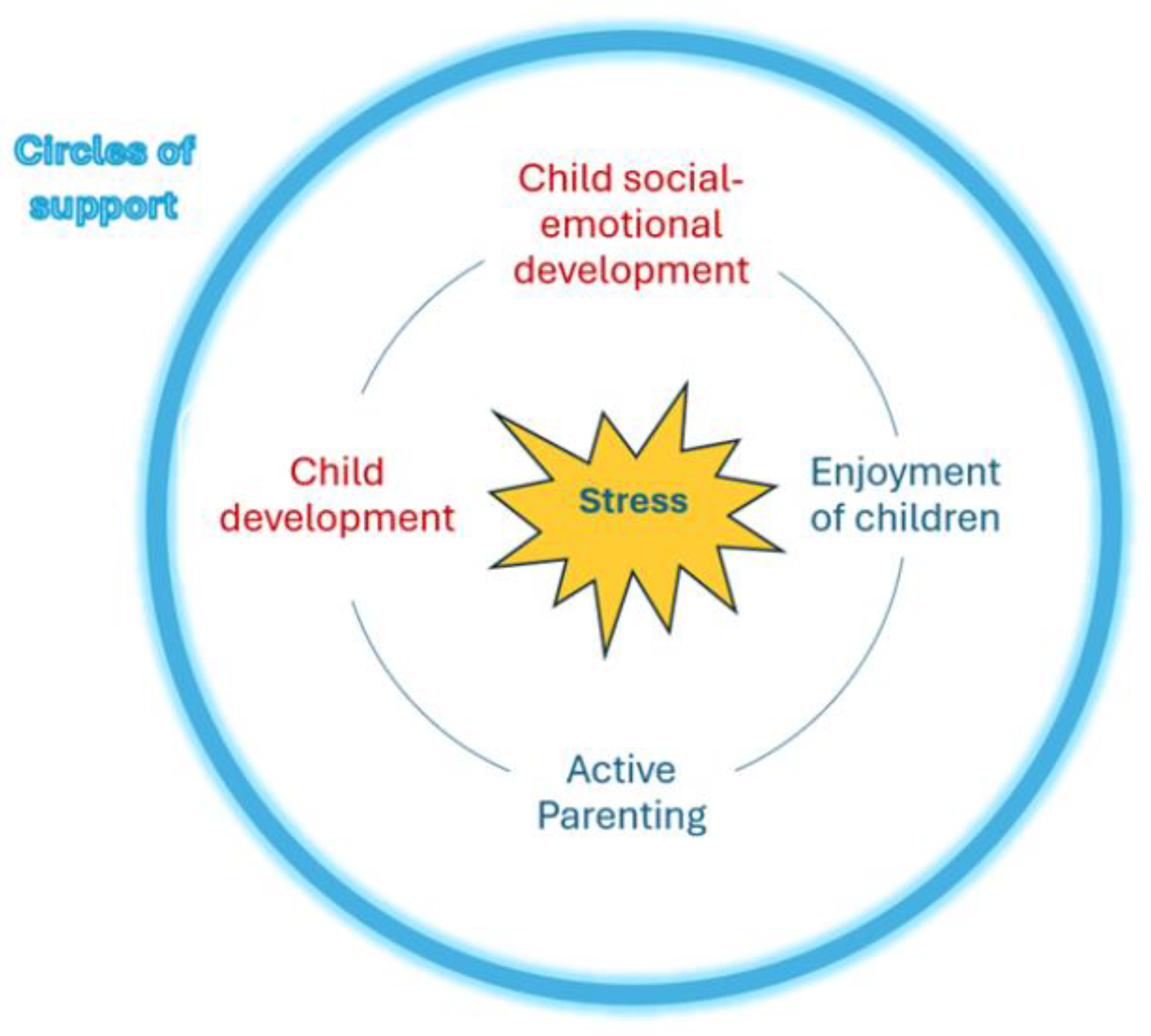

Child characteristics appeared to shape mother–child interactions, and these effects are likely bidirectional (

Figure 4). Mothers of children with higher scores on the MSEL interacted more frequently with their children. While frequent interaction stimulates development, observing a child acquire a new skill can also be rewarding for the mother, motivating continued engagement. Children who preferred quiet, inactive play received more parental interaction, and mothers who set clear boundaries were more likely to have children who were calmer and better able to focus on tasks. Children who were warm and outgoing attracted more engagement from their mothers, although it is equally plausible that appropriate parenting supports the development of these social–emotional traits. Interestingly, children who were more emotional or prone to tearfulness also received more parental attention, suggesting that adolescent mothers can be responsive to their child’s emotional state. Interventions for adolescent mothers should therefore emphasize interpreting and responding constructively to children’s cues. Supporting mothers in understanding child temperament and tailoring their parenting accordingly may strengthen the parent–child relationship and enhance developmental outcomes.

Which Adolescent Mothers Are more Likely to Frequently Complete Parenting Activities?

Older adolescent mothers are more likely to complete age-appropriate parenting activities daily. The caregivers of younger adolescents may be more involved in taking care of the young child, resulting in younger adolescents reporting lower engagement in parenting activities. It may reflect the benefit of maturity in adolescent capacity to respond appropriately to young child needs. This indicates that younger adolescents might need more assistance to bond with their young child and respond appropriately.

Adolescent mothers who have open and respectful communication with their own caregiver are also more likely to frequently complete parenting activities with their young child. Interventions should consider the intergenerational parenting structure in adolescent mother families to ensure protective outcomes for both mothers and their children (Save the Children US, 2022).

Both the availability of support and household constraints shape adolescent parenting behaviors, with ECD access providing a consistent positive influence independent of material or social support. Access to ECD services was positively associated with parenting activity. Adolescents whose children attend ECD may have more structured routines or opportunities for meaningful caregiving. They may also gain parenting knowledge via their relationship with the ECD teachers. In contrast, adolescent mothers with broader assistance in purchasing necessities for their child were less directly engaged, indicating that wider support networks can reduce the hands-on involvement of young mothers. Notably, food security was negatively associated with parenting activity, implying that adolescents from food-insecure households may take a more active role in caregiving, potentially as a compensatory response to limited resources. These data suggest that supported parenting has multiple advantages, whereas the burden of unsupported, “lonely” parenting may compromise the quality of interactions. The importance of these support networks is further illustrated in

Figure 4.

Adolescent mothers who reported enjoyment of their children more frequently completed parenting activities. These findings come with an interesting caveat. The more engaged an adolescent mother becomes with her young child, the more stressed she also becomes. The centrality of this stress in the experience of parenting is illustrated in

Figure 4. In consideration of her young age and developmental stage, this stress is likely more detrimental to her mental health and wellbeing than it would be for an older mother. Adolescent mothers need their own self-care strategies and ways to support their own emotional wellbeing. Of note was the role of others in the parenting demands. Few fathers were involved in parenting, and wider families played a part in a way which may not be directly comparable with adult mothers.

Does the Completion of Parenting Activities Support the Cognitive Development of the Child?

The 25% of mothers completing the least activities (rarely or never) had children with significantly lower MSEL scores than the 25% of mothers completing activities daily or almost daily. This small to moderate effect size could make a significant difference to child early learning outcomes. Early child development establishes building blocks for school readiness and later cognitive development. It is well known in South African educational research that children who start behind in the transition from early education settings to school, stay behind in their schooling achievements (Spaull & Kotze, 2015; Spaull & Pretorius, 2019). Teaching parenting skills to adolescent mothers is crucial for the best outcomes for their children. There was no significant difference between never completing activities and sometimes completing them indicates the importance of establishing daily, well-practised parenting interactions with children.

Policy and Programming Implications

Adolescent parenthood represents a dual developmental transition in which young parents are forming their own adult identities while caring for young children. Our findings indicate that adolescent mothers are motivated to engage playfully and responsively with their children, yet have less confidence in proactive parenting strategies and limit setting. Interventions should therefore build on existing strengths while scaffolding age-appropriate behavioural guidance, rather than assuming parenting “deficits.”

Policy responses should recognise family relationships as central to adolescent parenting. Improving communication between adolescent mothers and their caregivers, and establishing shared expectations for co-parenting, may reduce parenting stress and support more consistent caregiving routines. Including grandmothers or other co-residing caregivers in parenting sessions is likely to increase alignment across generations and reduce conflict over child-rearing norms.

Programming must address both relational and material conditions. Parenting support is unlikely to be effective where households face chronic financial strain or food insecurity. Routine screening for parenting stress and household need, alongside referral pathways to social protection, ECD programmes, and mental health services, is therefore essential. Ensuring accessible, quality early learning opportunities is particularly important for adolescent mothers seeking to continue schooling.

Strengthening parenting during adolescence offers two-generation benefits: adolescents gain skills and confidence during a formative developmental period, while young children receive early stimulation that supports developmental functioning. Policies that situate parenting support within broader youth development and intergenerational family systems are most likely to produce sustained improvements in well-being.

Finally, longitudinal research is needed to examine whether changes in parenting stress and parenting practices are maintained over time, and how these patterns relate to children’s developmental trajectories across early childhood.

Limitations

This study draws on a cross-sectional cohort of adolescent mothers in resource-scarce rural and urban South African settings, which limits the generalizability of findings to young mothers in other contexts. Longitudinal effects of parenting on child development, and vice versa, were not captured. Economic variables central to this population may have less applicability in higher-resource or different sociocultural settings. Child data were collected in home environments that ranged from crowded informal dwellings to township houses, potentially affecting children’s performance on the MSEL. Parenting constructs were assessed via self-report, and some scales were adapted from their original design, which may affect validity and comparability. While the study documents parenting stressors and parental activity among adolescent mothers, it does not clarify how these compare to older parents. The timing and sequence of key life-course events (e.g., sexual debut, first pregnancy, HIV diagnosis, school exclusion) were not tracked, limiting insight into critical intervention timepoints. Future research using longitudinal and qualitative methods is needed to strengthen causal inference and deepen understanding of adolescent parenting.

Conclusion

Adolescent mothers in resource-constrained settings parent while they themselves are still developing, creating a caregiving context shaped by both vulnerability and resilience. In this study, adolescent mothers reported high levels of parenting stress alongside frequent playful and responsive engagement with their children. Supporting adolescent parenting therefore requires attending to both developmental needs and caregiving responsibilities, rather than treating these as separate domains.

Co-parenting relationships with caregivers or grandmothers are central to the parenting environment and may influence stress, confidence, and daily caregiving routines. Interventions that acknowledge these intergenerational dynamics, while also addressing material constraints such as food insecurity and limited income, are likely to be more relevant and feasible.

Supporting adolescent parenting offers a two-generation opportunity in which adolescent developmental growth and child developmental functioning can be understood as linked indicators of family relational wellbeing. Embedding parenting support within broader youth development and family support systems may help sustain improvements. Future longitudinal research is needed to examine how parenting stress and practices change over time and how these patterns relate to children’s developmental trajectories.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Acknowledgments

We wish to express our deepest gratitude to the adolescent mother participants and Teen-Advisory-Group who generously shared their time, experiences, and insights as part of this research. Their openness and commitment made this work possible. We also acknowledge the invaluable contributions of the ORSA research assistants, whose dedication, care, and persistence in the field ensured the integrity and success of data collection. Finally, we thank the broader research and implementation teams for their ongoing support, collaboration, and belief in the importance of this work to improve the lives of young parents and their children. .

Declaration of Conflicting Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results. .

References

- Ajayi, A.I.; Athero, S.; Muga, W.; Kabiru, C.W. Lived experiences of pregnant and parenting adolescents in Africa: A scoping review. Reproductive Health 2023, 20, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amongin, D.; Kågesten, A.; Tunçalp, Ö.; Nakimuli, A.; Nakafeero, M.; Atuyambe, L.; Hanson, C.; Benova, L. Later life outcomes of women by adolescent birth history: analysis of the 2016 Uganda Demographic and Health Survey. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e041545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, L.S. Predictors of parenting stress in a diverse sample of parents of early adolescents in high-risk communities. Nursing Research 2008, 57, 340–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backhaus, S.; Leijten, P.; Jochim, J.; Melendez-Torres, G.J.; Gardner, F. Effects over time of parenting interventions to reduce physical and emotional violence against children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine 2023, 60, 102003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barron, P.; Subedar, H.; Letsoko, M.; Makua, M.; Pillay, Y. Teenage births and pregnancies in South Africa, 2017 - 2021 – a reflection of a troubled country: Analysis of public sector data. South African Medical Journal 2022, 112, 252–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beasley, L.O.; Jespersen, J.E.; Morris, A.S.; Farra, A.; Hays-Grudo, J. Parenting Challenges and Opportunities among Families Living in Poverty. Social Sciences 2022, 11, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, J.O.; Jones, W.H. The Parental Stress Scale: Initial Psychometric Evidence. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 1995, 12, 463–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, L.; Mathews, S.; Reis, R.; Crone, M. Mental health effects on adolescent parents of young children: reflections on outcomes of an adolescent parenting programme in South Africa. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies 2022, 17, 38–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bland, j. M.; Altman, D.G. Multiple significance tests: the Bonferroni method. BMJ 1995, 310, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

Promoting School Readiness and Early Learning: Implications of Developmental Research for Practice; Boivin, M., Bierman, K. L., Eds.; Guilford Publications, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Boivin, M.J.; Maliwichi-Senganimalunje, L.; Ogwang, L.W.; Kawalazira, R.; Sikorskii, A.; Familiar-Lopez, I.; Kuteesa, A.; Nyakato, M.; Mutebe, A.; Namukooli, J.L.; Mallewa, M.; Ruiseñor-Escudero, H.; Aizire, J.; Taha, T.E.; Fowler, M.G. Neurodevelopmental effects of ante-partum and post-partum antiretroviral exposure in HIV-exposed and uninfected children versus HIV-unexposed and uninfected children in Uganda and Malawi: a prospective cohort study. The Lancet HIV 2019, 6, e518–e530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Branson, N.; Hofmeyr, C.; Lam, D. Progress through school and the determinants of school dropout in South Africa. Development Southern Africa 2014, 31, 106–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buss, A.H.; Plomin, R. Temperament (PLE: Emotion); Psychology Press, 2014; Vol. 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, S.-K. Psychometric properties of the Chinese version of the Parental Stress Scale. Psychologia: An International Journal of Psychology in the Orient 2000, 43, 253–261. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2001-00387-004.

- Christianson, A.L.; Zwane, M.E.; Manga, P.; Rosen, E.; Venter, A.; Downs, D.; Kromberg, J.G.R. Children with intellectual disability in rural South Africa: prevalence and associated disability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 2002, 46, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cluver, L.D.; Meinck, F.; Steinert, J.I.; Shenderovich, Y.; Doubt, J.; Herrero Romero, R.; Lombard, C.J.; Redfern, A.; Ward, C.L.; Tsoanyane, S.; Nzima, D.; Sibanda, N.; Wittesaele, C.; De Stone, S.; Boyes, M.E.; Catanho, R.; Lachman, J.M.; Salah, N.; Nocuza, M.; Gardner, F. Parenting for Lifelong Health: a pragmatic cluster randomised controlled trial of a non-commercialised parenting programme for adolescents and their families in South Africa. BMJ Global Health 2018, 3, e000539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVito, J. How Adolescent Mothers Feel About Becoming a Parent. Journal of Perinatal Education 2010, 19, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donnelly, C.L.; Amaya-Jackson, L. Post-traumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents: Epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment options. Pediatric Drugs 2002, 4, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulamani, S.S.; Premji, S.S.; Kanji, Z.; Azam, S.I. A review of postpartum depression, preterm birth, and culture. Journal of Perinatal and Neonatal Nursing 2013, 27, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holder, M.D.; Coleman, B.; Singh, K. Temperament and Happiness in Children in India. Journal of Happiness Studies 2012, 13, 261–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagawa, R.M.C.; Deardorff, J.; García-Guerra, A.; Knauer, H.A.; Schnaas, L.; Neufeld, L.M.; Fernald, L.C.H. Effects of a Parenting Program Among Women Who Began Childbearing as Adolescents and Young Adults. Journal of Adolescent Health 2017, 61, 634–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilburn, K.; Ferrone, L.; Pettifor, A.; Wagner, R.; Gómez-Olivé, F.X.; Kahn, K. The Impact of a Conditional Cash Transfer on Multidimensional Deprivation of Young Women: Evidence from South Africa’s HTPN 068. Social Indicators Research 2020, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovacs, M. Children’s Depression Inventory: Parent Version (CDI:P); Multi-Health Systems, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Kyriazos, T.A.; Stalikas, A. Alabama Parenting Questionnaire—Short Form (APQ-9): Evidencing Construct Validity with Factor Analysis, CFA MTMM and Measurement Invariance in a Greek Sample. Psychology 2019, 10, 1790–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labadarios, D.; Steyn, N.; Maunder, E.; MacIntryre, U.; Gericke, G.; Swart, R.; Huskisson, J.; Dannhauser, A.; Vorster, H.; Nesmvuni, A.; Nel, J. The National Food Consumption Survey (NFCS): South Africa, 1999. Public Health Nutrition 2005, 8, 533–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachman, J.M.; Cluver, L.; Ward, C.L.; Hutchings, J.; Mlotshwa, S.; Wessels, I.; Gardner, F. Randomized controlled trial of a parenting program to reduce the risk of child maltreatment in South Africa. Child Abuse and Neglect 2017, 72, 338–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagerberg, D.; Magnusson, M. Utilization of child health services, stress, social support and child characteristics in primiparous and multiparous mothers of 18-month-old children. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health 2013, 41, 374–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leijten, P.; Melendez-Torres, G.J.; Gardner, F. Research Review: The most effective parenting program content for disruptive child behavior – a network meta-analysis. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 2022, 63, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lester, S.N. Evaluation of the Parent Centre’s positive parenting skills training programme: a randomised controlled trial. 2015. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/11427/15615.

- Li, Z.; Patton, G.; Sabet, F.; Subramanian, S.; Lu, C. Maternal healthcare coverage for first pregnancies in adolescent girls: a systematic comparison with adult mothers in household surveys across 105 countries, 2000–2019. BMJ Global Health 2020, 5, e002373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorencz, E.E.; Boivin, M.J. Screening for Neurodisability in Low-Resource Settings Using the Ten Questions Questionnaire. Neuropsychology of Children in Africa: Perspectives on Risk and Resilience 2013, 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louie, A.D.; Cromer, L.D.; Berry, J.O. Assessing Parenting Stress. The Family Journal 2017, 25, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucchetti, A.E.; Powers, W.G.; Love, D.E. The Empirical Development of the Child-Parent Communication Apprehension Scale for Use With Young Adults. Journal of Family Communication 2002, 2, 109–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masi, G.; Mucci, M.; Favilla, L.; Brovedani, P.; Millepiedi, S.; Perugi, G. Temperament in adolescents with anxiety and depressive disorders and in their families. Child Psychiatry and Human Development 2003, 33, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCoy, A.; Melendez-Torres, G.J.; Gardner, F. Parenting interventions to prevent violence against children in low- and middle-income countries in East and Southeast Asia: A systematic review and multi-level meta-analysis. Child Abuse and Neglect 2020, 103, 104444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEachern, A.D.; Dishion, T.J.; Weaver, C.M.; Shaw, D.S.; Wilson, M.N.; Gardner, F. Parenting Young Children (PARYC): Validation of a Self-Report Parenting Measure. Journal of Child and Family Studies 2012, 21, 498–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejia, A.; Leijten, P.; Lachman, J.M.; Parra-Cardona, J.R. Different Strokes for Different Folks? Contrasting Approaches to Cultural Adaptation of Parenting Interventions. Prevention Science 2017, 18, 630–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milosavljevic, B.; Vellekoop, P.; Maris, H.; Halliday, D.; Drammeh, S.; Sanyang, L.; Darboe, M.K.; Elwell, C.; Moore, S.E.; Lloyd-Fox, S. Adaptation of the Mullen Scales of Early Learning for use among infants aged 5- to 24-months in rural Gambia. Developmental Science 2019, 22, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, S.; Chipeta, M.G.; Kamninga, T.; Nthakomwa, L.; Chifungo, C.; Mzembe, T.; Vellemu, R.; Chikwapulo, V.; Peterson, M.; Abdullahi, L.; Musau, K.; Wazny, K.; Zulu, E.; Madise, N. Interventions to prevent unintended pregnancies among adolescents: a rapid overview of systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews 2023, 12, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullen, E.M. Mullen Scales of Early Learning (MSEL); Circle, Pines, Ed.; American Guidance Service Inc, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Östberg, M.; Hagekull, B. A Structural Modeling Approach to the Understanding of Parenting Stress. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology 2000, 29, 615–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pulkkinen, L.; Lyyra, A.-L.; Kokko, K. Is social capital a mediator between self-control and psychological and social functioning across 34 years? International Journal of Behavioral Development 2011, 35, 475–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, C.R.; Richmond, B. Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale. In RCMAS Manual; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, K.J.; Smith, C.; Cluver, L.; Toska, E.; Zhou, S.; Boyes, M.; Sherr, L. Adolescent Motherhood and HIV in South Africa: Examining Prevalence of Common Mental Disorder. AIDS and Behavior 2022, 26, 1197–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Save the Children US. (2022). Promising directions and missed opportunities for reaching first-time mothers with reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health services: Findings from formative assessments in two countries. 1–12. https://resourcecentre.savethechildren.net/document/promising-directions-and-missed-opportunities-for-reaching-first-time-mother-with-reproductive-maternal-newborn-and-children-health-services-findings-from-formative-in-two-countries.

- Sheehan, D.V.; Sheehan, K.H.; Shytle, R.D.; Janavs, J.; Bannon, Y.; Rogers, J.E.; Milo, K.M.; Stock, S.L.; Wilkinson, B. Reliability and Validity of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview for Children and Adolescents (MINI-KID). The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 2010, 71, 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhi, P.; Kumar, M.; Malhi, P.; Kumar, R. Utility of the WHO Ten Questions Screen for Disability Detection in a Rural Community the North Indian Experience. Journal of Tropical Pediatrics 2007, 53, 383–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snider, L.M.; Dawes, A. Psychosocial Vulnerability and Resilience Measures For National-Level Monitoring of Orphans and Other Vulnerable Children: Recommendations for Revision of the UNICEF Psychological Indicator. 2006. Available online: http://www.meajo.org/text.asp?2020/27/3/172/299645.

- South Africa Gateway. Mapping poverty in South Africa; South Africa Info, 2017; Available online: https://southafrica-info.com/people/mapping-poverty-in-south-africa/.

- Spaull, N.; Kotze, J. Starting behind and staying behind in South Africa: The case of insurmountable learning deficits in mathematics. International Journal of Educational Development 2015, 41, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaull, N.; Pretorius, E. Still Falling at the First Hurdle: Examining Early Grade Reading in South Africa. In South African Schooling: The Enigma of Inequality; 2019; pp. 147–168. [Google Scholar]

- Steventon Roberts, K.J.; Smith, C.; Toska, E.; Cluver, L.; Wittesaele, C.; Langwenya, N.; Shenderovich, Y.; Saal, W.; Jochim, J.; Chen-Charles, J.; Marlow, M.; Sherr, L. Exploring the cognitive development of children born to adolescent mothers in South Africa. Infant and Child Development 2023, 32, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toska, E.; Saal, W.; Chen Charles, J.; Wittesaele, C.; Langwenya, N.; Jochim, J.; Steventon Roberts, K.J.; Anquandah, J.; Banougnin, B.H.; Laurenzi, C.; Sherr, L.; Cluver, L. Achieving the health and well-being Sustainable Development Goals among adolescent mothers and their children in South Africa: Cross-sectional analyses of a community-based mixed HIV-status cohort. PLOS ONE 2022, 17, e0278163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, C.L.; Wessels, I.M.; Lachman, J.M.; Hutchings, J.; Cluver, L.D.; Kassanjee, R.; Nhapi, R.; Little, F.; Gardner, F. Parenting for Lifelong Health for Young Children: a randomized controlled trial of a parenting program in South Africa to prevent harsh parenting and child conduct problems. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 2020, 61, 503–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO guidelines on parenting interventions to prevent maltreatment and enhance parent–child relationships with children aged 0–17 years. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Fact Sheet: Adolescent pregnancy. 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-pregnancy.

- Wray, W. Parenting in Poverty: Inequity through the Lens of Attachment and Resilience. American International Journal of Social Science 2015, 4. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).