Submitted:

19 December 2025

Posted:

22 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Location and Collection

2.2. Biometric Measurements

2.3. Condition Indices

- -

- CI: The condition index was calculated as the ratio between the soft tissue weight and the total weight expressed as a percentage. This index serves as an indicator of the clam’s nutritional and reproductive condition [30].

- -

- BCI: Body condition index derived from DCI (Dry Condition Index, defined as the dry weight of the soft body tissue relative to the dry weight of the shell expressed as a percentage). In our case due to logistical constraints, wet tissue weight was used instead of dry weight, and the index was adapted accordingly, being calculated as a relation between soft tissue weight and shell weight expressed as a percentage [31].

- -

- GCI: The gonadal condition index relates gonadal-visceral mass weight with total body weight (excluding the shell) expressed as a percentage, it provides an idea of the gonadal development stage [32].

2.4. Laboratory Processing and Histology

2.5. Gonadal Histological Examination

2.6. Biochemical Composition

2.7. Environmental Parameters

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Biometric Measurements

3.2. Condition Indices

3.3. Sex Distribution

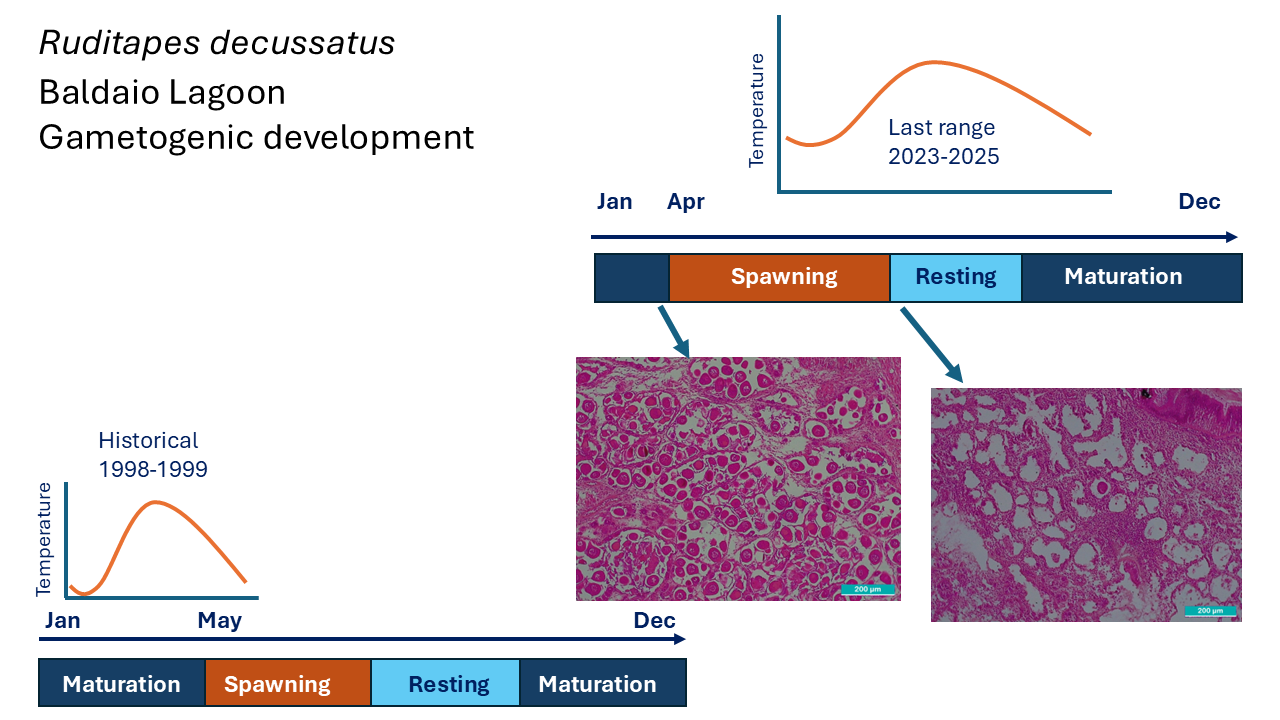

3.4. Histological Study of Gametogenic Cycle

3.5. Gametogenic Cycle and Maturation Scale Distribution

3.6. Biochemical Analyses

3.7. Temperature in the Lagoon

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of Lagoon Temperatures

4.2. Biometrics Measurements

4.3. Seasonal Variations of Gametogenic Cycle

4.4. Condition Indices

4.5. Biochemical Composition

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BCI | Body Condition index |

| CI | Condition index |

| CIMA | Centro de Investigacións Mariñas de Galicia |

| DCI | Dry condition index |

| FBW | Total fresh body weight |

| GCI | Gonadal condition index |

| GW | Gonadal-hepatopancreas tissue weight |

| NW | Northwest |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| STW | Fresh soft tissue weight |

| SW | Shell weight |

| TSL | Total shell length |

| TST | Total shell thickness |

| TSW | Total shell width |

References

- IPCC. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the Impacts of Global Warming of 1.5°C above Pre-Industrial Levels and related Global Greenhouse Gas Emission Pathways, in the Context of Strengthening the Global Response to the Threat of Climate Change, Sustainable Development, and Efforts to Eradicate PovertyCambridge University Press; Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pörtner, H.O., Roberts, D., Skea, J., Shukla, P.R., Pirani, A., Mofouma-Okia, W., Péan, C., Pidcock, R., Connors, S., Matthews, J.B.R., Chen, Y., Zhou, X., Gomis, M.I., Lonnoy, E., Maycock, T., Tignor, M., Waterfield, T., Eds.; Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, 2018; ISBN 978-1-009-15795-7. [Google Scholar]

- Copernicus Ocean State Report (OSR8), 8th ed.; Von Schuckmann, K., Moreira, L., Cancet, M., Gues, F., Autret, E., Aydogdu, A., Castrillo, L., Ciani, D., Cipollone, A., Clementi, E., et al., Eds.; Copernicus Publications, 2024; Volume 1.2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peñuelas, J.; Sardans, J.; Filella, I.; Estiarte, M.; Llusià, J.; Ogaya, R.; Carnicer, J.; Bartrons, M.; Rivas-Ubach, A.; Grau, O.; et al. Assessment of the Impacts of Climate Change on Mediterranean Terrestrial Ecosystems Based on Data from Field Experiments and Long-Term Monitored Field Gradients in Catalonia. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2017, 152, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellwanger, J.H.; Ziliotto, M.; Kulmann-Leal, B.; Chies, J.A.B. Environmental Challenges in Southern Brazil: Impacts of Pollution and Extreme Weather Events on Biodiversity and Human Health Multidisciplinary. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoro-Mendoza, A.; Calvo-Sancho, C.; González-Alemán, J.J.; Díaz-Fernández, J.; Bolgiani, P.; Sastre, M.; Moreno-Chamarro, E.; Martín, M.L. Environments Conductive to Tropical Transitions in the North Atlantic: Anthropogenic Climate Change Influence Study. Atmos. Res. 2024, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraeuter, J.; Beal, B. Molluscan Shellfish Aquaculture: A Practical Guide; Shumway, S.E., Ed.; 5m Publishing: Wallingford Oxfordshire, 2021; pp. 41–60. ISBN 9781789181470. [Google Scholar]

- Mannai, A.; Hmida, L.; Bouraoui, Z.; Guerbej, H.; Gharred, T.; Jebali, J. Does Thermal Stress Modulate the Biochemical and Physiological Responses of Ruditapes decussatus Exposed to the Progestin Levonorgestrel? Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2022, 29, 85211–85228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urrutia, M.B.; Ibarrola, I.; Iglesias, J.I.P.; Navarro, E. Energetics of Growth and Reproduction in a High-Tidal Population of the Clam Ruditapes decussatus from Urdaibai Estuary (Basque Country, N. Spain). J. Sea Res. 1999, 42, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez, E.; Woodin, S.A.; Wethey, D.S.; Peteiro, L.G.; Olabarria, C. Reproduction Under Stress: Acute Effect of Low Salinities and Heat Waves on Reproductive Cycle of Four Ecologically and Commercially Important Bivalves. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 685282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Camacho, A.; Delgado, M.; Fernández-Reiriz, M.J.; Labarta, U. Energy Balance, Gonad Development and Biochemical Composition in the Clam Ruditapes decussatus. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2003, 258, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macho, G.; Woodin, S.A.; Wethey, D.S.; Vázquez, E. Impacts of Sublethal and Lethal High Temperatures on Clams Exploited in European Fisheries. J. Shellfish Res. 2016, 35, 405–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velez, C.; Figueira, E.; Soares, A.M.V.M.; Freitas, R. Effects of Seawater Temperature Increase on Economically Relevant Native and Introduced Clam Species. Mar. Environ. Res. 2017, 123, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabra, M.; Morrall, Z.; Helmer, L.; Watson, G.; Preston, J. Filtration Behaviour of Ostrea edulis: Diurnal Rhythmicity Influenced by Light Cycles, Body Size and Water Temperature. Estuaries and Coasts 2025, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansson, A.; Norkko, J.; Dupont, S.; Norkko, A. Growth and Survival in a Changing Environment: Combined Effects of Moderate Hypoxia and Low PH on Juvenile Bivalve Macoma balthica. J. Sea Res. 2015, 102, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwaner, C.; Barbosa, M.; Connors, P.; Park, T.J.; de Silva, D.; Griffith, A.; Gobler, C.J.; Pales Espinosa, E.; Allam, B. Experimental Acidification Increases Susceptibility of Mercenaria mercenaria to Infection by Vibrio spp. Mar. Environ. Res. 2020, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahé, M.; Aurelle, D.; Poggiale, J.C.; Mayot, N. Assessment of the Distribution of Ruditapes Spp. in Northern Mediterranean Sites Using Morphological and Genetic Data. J. Molluscan Stud. 2022, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickman, C.; Roberts, L.; Larson, A. Integrated Principles of Zoology, 11th ed.; McGraw-Hill, International, 2001; Volume 16, pp. 325–355. ISBN 0–07–290961–7. [Google Scholar]

- Aranda-Burgos, J.A.; Da Costa, F.; Nóvoa, S.; Ojea, J.; Martínez-Patiño, D. Effects of Microalgal Diet on Growth, Survival, Biochemical and Fatty Acid Composition of Ruditapes decussatus Larvae. Aquaculture 2014, 420–421, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, M.; Camacho, A.P. Histological Study of the Gonadal Development of Ruditapes decussatus (L.) (Mollusca: Bivalvia) and Its with Available Food*. Sci. Mar. 2005, 69, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalba, A.; Carballal, M.J.; Lopez, M.C. Estudio Del Ciclo Gonadal de Tres Especies de Almeja, Ruditapes decussatus, Venerupis pullastra y Venerupis rhomboides, de Las Rías Gallegas. IV Congreso Nacional de Acuicultura, Vilanova de Arousa, Spain, January 1993; pp. 341–346. [Google Scholar]

- Smaoui-damak, W.; Mathieu, M.; Rebai, T.; Hamza-chaffai, A. Histology of the Reproductive Tissue of the Clam Ruditapes decussatus from the Gulf of Gabès (Tunisia). Invertebr. Reprod. Dev. 2007, 50, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, M.; Pérez-Camacho, A. Comparative Study of Gonadal Development of Ruditapes philippinarum (Adams and Reeve) and Ruditapes decussatus (L.) (Mollusca: Bivalvia): Influence of Temperature. Sci. Mar. 2007, 71, 471–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, M.; Pérez-Camacho, A. A Study of Gonadal Development in Ruditapes decussatus (L.) (Mollusca, Bivalvia), Using Image Analysis Techniques: Influence of Food Ration and Energy Balance. J. Shellfish Res. 2003, 22, 435–441. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10261/313193.

- Matias, D.; Joaquim, S.; Matias, A.M.; Moura, P.; de Sousa, J.T.; Sobral, P.; Leitão, A. The Reproductive Cycle of the European Clam Ruditapes decussatus (L., 1758) in Two Portuguese Populations: Implications for Management and Aquaculture Programs. Aquaculture 2013, 406–407, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojea, J.; Abad, M.; Pazos, A.J.; Martínez, D.; Novoa, S.; García-Martínez, P.; Sánchez, J.L. Effects of Temperature Regime on Broodstock Conditioning of Ruditapes decussatus. J. Shellfish Res. 2008, 27, 1093–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maneiro, V.; Silva, A.; Pazos, A.J.; Sánchez, J.L.; Pérez-Parallé, M.L. Effects of Temperature and Photoperiod on the Conditioning of the Flat Oyster (Ostrea edulis L.) in Autumn. Aquac. Res. 2017, 48, 4554–4562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xunta De Galicia; Consellería do Mar. Pesca de Galicia Anuario de pesca de Galicia 2024. Available online: https://www.pescadegalicia.gal/gl/publicacions (accessed on September 2025).

- Aranguren, R.; Gomez-León, J.; Balseiro, P.; Costa, M.M.; Novoa, B.; Figueras, A. Abnormal Mortalities of the Carpet Shell Clam Ruditapes decussatus (Linnaeus 1756) in Natural Bed Populations a Practical Approach. Aquac. Res. 2014, 45, 1303–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Geológico y Minero de España. Estudio y Catalogación de Puntos de Interés Geológico-Minero En El Sector Occidental de Galicia. 1981. Available online: https://info.igme.es/SidPDF%5C016000%5C984%5C16984_0001.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Duisan, L.; Salim, G.; Ransangan, J. Sex Ratio, Gonadal and Condition Indexes of the Asiatic Hard Clam, Meretrix meretrix in Marudu Bay, Malaysia. Biodiversitas 2021, 22, 4895–4904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walne, P.R. Experiments on the Culture in the Sea of the Butterfish Venerupis decussata L. Aquaculture 1976, 8, 371–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, A.; Beninger, P.G. The Use of Physiological Condition Indices in Marine Bivalve Aquaculture. Aquaculture 1985, 44, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, D.W.; Lewis, E.J.; Keller, B.J. Histological Techniques for Marine Bivalve Mollusks and Crustaceans NOAA Technical Memorandum NOS NCCOS, 2004; 5, 218 pp. Available online: https://repository.library.noaa.gov/view/noaa/1790/noaa_1790_DS1.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Ojea, J.; Pazos, A.J.; Martínez, D.; Novoa, S.; Sánchez, J.L.; Abad, M. Seasonal Variation in Weight and Biochemical Composition of the Tissues of Ruditapes decussatus in Relation to the Gametogenic Cycle. Aquaculture 2004, 238, 451–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nóvoa, S. Metabolismo Lipídico, Ácidos Grasos En El Cultivo Larvario De Almeja Babosa, Venerupis Pullastra (Montagu, 1803). “Calidad Ovocitaria, Larvaria Y Nutricional Con Una Aproximación Al Uso De La Microencapsulación Lipídica”. PhD. Thesis, Universidade de Santiago de Compostela, Santiago de Compostela, Spain, 29 February 2008. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10347/2397.

- Lowry, O.H.; Rosebrough, N.J.; Farr, A.L.; Randall, R.J. Protein Measurement With the folin phenol reagent*. J. Biol. Chem. 1951, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraga, F. Determinación De Glucógeno En Moluscos Con El Reactivo De Antrona. Inv. Pesq. 1956, 3, 69–74. [Google Scholar]

- Folch, J.; Lees, M.; Sloane, G.H. A Simple Method for the Isolation and Purification of Total Lipides from Animal Tissues. J. Biol. Chem. 1956, 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beninger, P.G.; Lucas, A. Seasonal Variations in Condition, Reproductive Activity, and Gross Biochemical Composition of Two Species of Adult Clam Reared in a Common Habitat: Tapes decussatus L. (Jeffreys) and Tapes philippinarum (Adams & Reeve). Mar. Biol. Ecol. 1984, 79, 19–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazos, A.J.; Román, G.; Acosta, C.P.; Abad, M.; Sánchez, J.L. Seasonal Changes in Condition and Biochemical Composition of the Scallop Pecten maximus L. from Suspended Culture in the Ria de Arousa (Galicia, N.W. Spain) in Relation to Environmental Conditions. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 1997, 211, 169–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Tecnolóxico para o Control do Medio Mariño de Galicia, X. de G. INTECMAR. Available online: https://www.intecmar.gal/ctd/ (accessed on 26 May 2025).

- Simantiris, N.; Theocharis, A. Seasonal Variability of Hydrological Parameters and Estimation of Circulation Patterns: Application to a Mediterranean Coastal Lagoon. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojea, J.; Martínez, D.; Novoa, S.; Pazos, A.J.; Abad, M. Contenido y Distribución de Glucógeno En Relación Con El Ciclo Gametogénico de Ruditapes decussatus (L., 1758) En Una Población Natural de Las lagunas de Baldaio (Galicia, Noroeste de España). Bol. Inst. Esp. Oceanogr. 2002, 18, 307–313. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10261/313231.

- Mccarthy, G.D.; Smeed, D.A.; Cunningham, S.A.; Roberts, C.D. Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation. In Marine Climate Change Impacts Partnership: Science Review; 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smeed, D.A.; Josey, S.A.; Beaulieu, C.; Johns, W.E.; Moat, B.I.; Frajka-Williams, E.; Rayner, D.; Meinen, C.S.; Baringer, M.O.; Bryden, H.L.; et al. The North Atlantic Ocean Is in a State of Reduced Overturning. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2018, 45, 1527–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caesar, L.; Rahmstorf, S.; Robinson, A.; Feulner, G.; Saba, V. Observed Fingerprint of a Weakening Atlantic Ocean Overturning Circulation. Nature 2018, 556, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rato, A.; Joaquim, S.; Matias, A.M.; Roque, C.; Marques, A.; Matias, D. The Impact of Climate Change on Bivalve Farming: Combined Effect of Temperature and Salinity on Survival and Feeding Behaviour of Clams Ruditapes decussatus. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walne, P.R. Factors Affecting the Relation Between Feeding and Growth in Bivalves quantity of food consumed. In Harvesting Polluted Waters; Devik, O., Ed.; Springer: Boston, MA, 1976; ISBN 978-1-4613-4328-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Li, Q.; Kong, L. Reproductive Cycle and Seasonal Variations in Lipid Content and Fatty Acid Composition in Gonad of the Cockle Fulvia mutica in Relation to Temperature and Food. J. Ocean Univ. China 2013, 12, 427–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maneiro, V.; Pérez-Parallé, M.L.; Pazos, A.J.; Silva, A.; Sánchez, J.L. Combined Effects of Temperature and Photoperiod on the Conditioning of the Flat Oyster (Ostrea edulis [Linnaeus, 1758]) in Winter. J. Shellfish. Res. 2016, 35, 137–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toba, M.; Miyama, Y. Influence of Temperature on the Sexual Maturation in Manila Clam, Ruditapes philippinarum. Aquaculture Science 1995, 43, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vélez, A.; Epifanio, C.E. Effects of Temperature and Ration on Gametogenesis and Growth in the Tropical Mussel Perna perna (L.). Aquaculture 1981, 22, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansell, A.D.; Frenkiel, L.; Moueza, M. Seasonal Changes in Tissue Weight and Biochemical Composition for the Bivalve Donax trunculus L. on the Algerian Coast. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 1980, 45, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansell, A.D. Distribution, Growth and Seasonal Changes in Biochemical Composition for the Bivalve Donax vittatus (Da Costa) from Kames Bay, Millport. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 1972, 10, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Qi; Yang, Lin; Ke, Qiaozhen; Kong, Lingfeng. Gametogenic Cycle and Biochemical Composition of the Clam Mactra chinensis (Mollusca Bivalvia) Implications for Aquaculture and Wild Stock Management. Mar. Biol. Res. 2011, 7, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Phases | Characteristics | Microscopic elements |

|---|---|---|

| Phase E0 | Sexual resting stage | Connective tissue fills the gonad, absence of gametes, sexual identification is no possible. |

| Phase E1 | Onset of gametogenesis |

Germinal cells are present, initial formation of follicles, is very difficult to determine the sex of individuals specially in the early phase of the stage |

| Phase E2 | Gametogenic development |

Follicles fill a large part of the tissue, oocyte in females have grown and spermatocytes fill the follicles; sex can be identified in almost all the specimens. |

| Phase E3 | Morphological maturity |

Gonad is filled with mature oocytes or spermatozoa arranged in sheets towards the centre of the follicles; in females the oocyte reach their largest size and the pressure on the follicles makes them polyhedral in shape. |

| Phase E4 | Spawning | In females, oocytes detach from the follicle walls, in males’ spermatozoa lose their radial arrangement. |

| Phase E5 | Postspawning | Follicles disintegrate and only remnants of gametes are present, the animal enters in a sexual resting phase follicle walls are broken. |

| TSL (mm) |

TSW (mm) |

TST (mm) |

FBW (gr) |

SW (gr) |

STW (gr) |

GW (gr) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M±SD | M±SD | M±SD | M±SD | M±SD | M±SD | M±SD | |

| March 2023 | 45.38 ± 2.36 | 32.43 ± 1.72 | 21.65 ± 1.16 | 21.79 ± 3.14 | 11.43 ± 1.19 | 4.35 ± 0.48 | 0.96 ± 0.14 |

| April 2023 | 43.05 ± 1.24 | 31.12 ± 1.01 | 21.33 ± 0.99 | 18.37 ± 1.88 | 10.05 ± 1.1 | 4.56 ± 0.46 | 1.29 ± 0.24 |

| May 2023 | 44.39 ± 3.26 | 31.94 ± 1.98 | 21.63 ± 1.16 | 20.9 ± 3.23 | 11.89 ± 1.56 | 4.86 ± 0.7 | 1.37 ± 0.28 |

| June 2023 | 47.8 ± 2.45 | 34.24 ± 1.49 | 22.89 ± 1.04 | 25.21 ± 3.45 | 13.34 ± 1.46 | 5.26 ± 0.87 | 1.63 ± 0.33 |

| July 2023 | 42.83 ± 0.98 | 31.23 ± 0.9 | 21.46 ± 0.77 | 19.4 ± 1.61 | 11.05 ± 1.19 | 3.26 ± 0.64 | 1.03 ± 0.33 |

| August 2023 | 42.41 ± 0.85 | 31.13 ± 0.79 | 22 ± 2.55 | 18.38 ± 1.85 | 10.39 ± 0.96 | 3.42 ± 0.58 | 0.68 ± 0.14 |

| September 2023 | 42.37 ± 1.3 | 34.08 ± 1.94 | 19.86 ± 1.05 | 16.82 ± 2.45 | 8.88 ± 1.62 | 3.24 ± 0.39 | 0.75 ± 0.17 |

| February 2024 | 42.27 ± 1.4 | 30.22 ± 0.77 | 19.77 ± 0.75 | 17.72 ± 1.68 | 9.68 ± 1.22 | 3.59 ± 0.26 | 0.73 ± 0.06 |

| March 2024 | 38.58 ± 2.01 | 27.92 ± 1.49 | 18.26 ± 1.24 | 14.43 ± 2.56 | 7.78 ± 1.59 | 3.09 ± 0.47 | 0.65 ± 0.12 |

| April 2024 | 41.55 ± 0.92 | 30.08 ± 0.85 | 19.13 ± 0.75 | 16.24 ± 1.25 | 8.6 ± 0.93 | 4.19 ± 0.54 | 1.23 ± 0.27 |

| May 2024 | 40.15 ± 2.57 | 28.95 ± 1.67 | 18.19 ± 1.24 | 13.48 ± 2.87 | 7.69 ± 1.66 | 4.51 ± 0.6 | 1.61 ± 0.31 |

| June 2024 | 41.11 ± 0.82 | 28.8 ± 1.14 | 18.48 ± 0.81 | 13.54 ± 1.39 | 6.92 ± 0.89 | 3.72 ± 0.4 | 1.09 ± 0.2 |

| July 2024 | 40.63 ± 1.86 | 29.4 ± 1.4 | 19.64 ± 2.43 | 14.86 ± 2.13 | 8.27 ± 1.43 | 3.15 ± 0.51 | 1.12 ± 0.26 |

| September 2024 | 42.79 ± 2.46 | 30.83 ± 1.36 | 20.53 ± 1.51 | 18.17 ± 3.3 | 9.54 ± 1.82 | 4.48 ± 0.62 | 1.16 ± 0.27 |

| October 2024 | 41.19 ± 2.5 | 29.35 ± 1.82 | 19.85 ± 1.41 | 16.72 ± 3.38 | 10.04 ± 1.63 | 2.95 ± 0.58 | 0.59 ± 0.16 |

| November 2024 | 41.26 ± 2.25 | 30.02 ± 1.75 | 19.87 ± 1.58 | 16.56 ± 3.18 | 9.16 ± 1.95 | 3.32 ± 0.75 | 0.71 ± 0.18 |

| December 2024 | 42.72 ± 1.21 | 30.77 ± 0.86 | 20.63 ± 0.77 | 19.35 ± 1.62 | 11.37 ± 1.36 | 3.51 ± 0.59 | 0.75 ± 0.23 |

| January 2025 | 44 ± 1.87 | 31.18 ± 1.38 | 19.59 ± 1.88 | 18.01 ± 3.18 | 9.88 ± 2.09 | 3.81 ± 0.5 | 0.81 ± 0.15 |

| TSW | TST | FBW | SW | STW | GW | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TSL | R | .844** | .823** | .933** | .858** | .648** | .365 |

| p-value | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | .004 | .137 | |

| N | 18 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 18 | |

| TSW | R | .745** | .795** | .714** | .433 | .214 | |

| p-value | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | .073 | .395 | ||

| N | 18 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 18 | ||

| TST | R | .908** | .906** | .417 | .192 | ||

| p-value | <.001 | <.001 | .085 | .445 | |||

| N | 18 | 18 | 18 | 18 | |||

| FBW | R | .966** | .537* | .234 | |||

| p-value | <.001 | .022 | .35 | ||||

| N | 18 | 18 | 18 | ||||

| SW | R | .433 | .161 | ||||

| p-value | .072 | .524 | |||||

| N | 18 | 18 | |||||

| STW | R | .833** | |||||

| p-value | <.001 | ||||||

| N | 18 | ||||||

| IC | BCI | GCI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| M ± SD | M ± SD | M ±S D | |

| March 2023 | 20.93 ± 1.63 | 38.21 ± 3.51 | 22.17 ± 2.16 |

| April 2023 | 25.92 ± 2.11 | 45.53 ± 3.21 | 28.13 ± 3.19 |

| May 2023 | 22.43 ± 2.42 | 41.14 ± 5.95 | 28.23 ± 3.94 |

| June 2023 | 21.7 ± 1.99 | 39.39 ± 4.35 | 31.18 ± 5.19 |

| July 2023 | 16.7 ± 2.73 | 29.55 ± 5.29 | 31.3 ± 6.57 |

| August 2023 | 18.31 ± 3.11 | 33.11 ± 5.93 | 19.98 ± 2.41 |

| September 2023 | 19.53 ± 3.63 | 37.56 ± 8 | 23.1 ± 4.08 |

| February 2024 | 20.29 ± 0.85 | 37.29 ± 2.44 | 20.43 ± 1.38 |

| March 2024 | 21.57 ± 1.6 | 40.31 ± 4.09 | 20.98 ± 2.16 |

| April 2024 | 25.7 ± 3.53 | 49.36 ± 8.57 | 29.07 ± 3.69 |

| May 2024 | 29.84 ± 1.66 | 59.53 ± 5.55 | 35.46 ± 2.85 |

| June 2024 | 26.54 ± 1.84 | 54.12 ± 5.43 | 29.25 ± 3.34 |

| July 2024 | 20.8 ± 2.72 | 38.56 ± 7.06 | 35.32 ± 4.13 |

| September 2024 | 25.21 ± 2.47 | 47.62 ± 5.61 | 25.55 ± 3.34 |

| October 2024 | 17 ± 2.75 | 29.69 ± 5.02 | 19.71 ± 2.03 |

| November 2024 | 20.25 ± 3.84 | 36.95 ± 8.09 | 21.37 ± 2.25 |

| December 2024 | 18.01 ± 1.78 | 30.89 ± 3.71 | 20.99 ± 3.44 |

| January 2025 | 21.54 ± 3.78 | 39.7 ± 7.82 | 21.26 ± 3.29 |

| Proteins | Carbohydrates | Lipids | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature | R | .302 | -.515 | .340 |

| p-value | .224 | .029 | .168 | |

| N | 18 | 18 | 18 | |

| INDEX | BIOMOLECULE | r | p-value | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CI | Proteins | .246 | .326 | 18 |

| Carbohydrates | .081 | .750 | 18 | |

| Lipids | .333 | .176 | 18 | |

| BCI | Proteins | .259 | .300 | 18 |

| Carbohydrates | .040 | .875 | 18 | |

| Lipids | .298 | .230 | 18 | |

| GCI | Proteins | .517 | .028 | 18 |

| Carbohydrates | -.440 | .067 | 18 | |

| Lipids | .644 | .004 | 18 |

| Temperature | ||

|---|---|---|

| Length | R | .403 |

| p-value | .098 | |

| N | 18 | |

| Width | R | .507* |

| p-value | .032 | |

| N | 18 | |

| Thickness | R | .637** |

| p-value | .004 | |

| N | 18 | |

| TBW | R | .469 |

| p-value | .05 | |

| N | 18 | |

| SW | R | .535* |

| p-value | .022 | |

| N | 18 | |

| STW | R | .018 |

| p-value | .945 | |

| N | 18 | |

| GW | R | .148 |

| p-value | .557 | |

| N | 18 | |

| Temperature | ||

|---|---|---|

| CI | R | -.476 |

| p-value | .046 | |

| N | 18 | |

| BCI | R | -.468 |

| p-value | .050 | |

| N | 18 | |

| GCI | R | .204 |

| p-value | .417 | |

| N | 18 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).