Submitted:

19 December 2025

Posted:

22 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

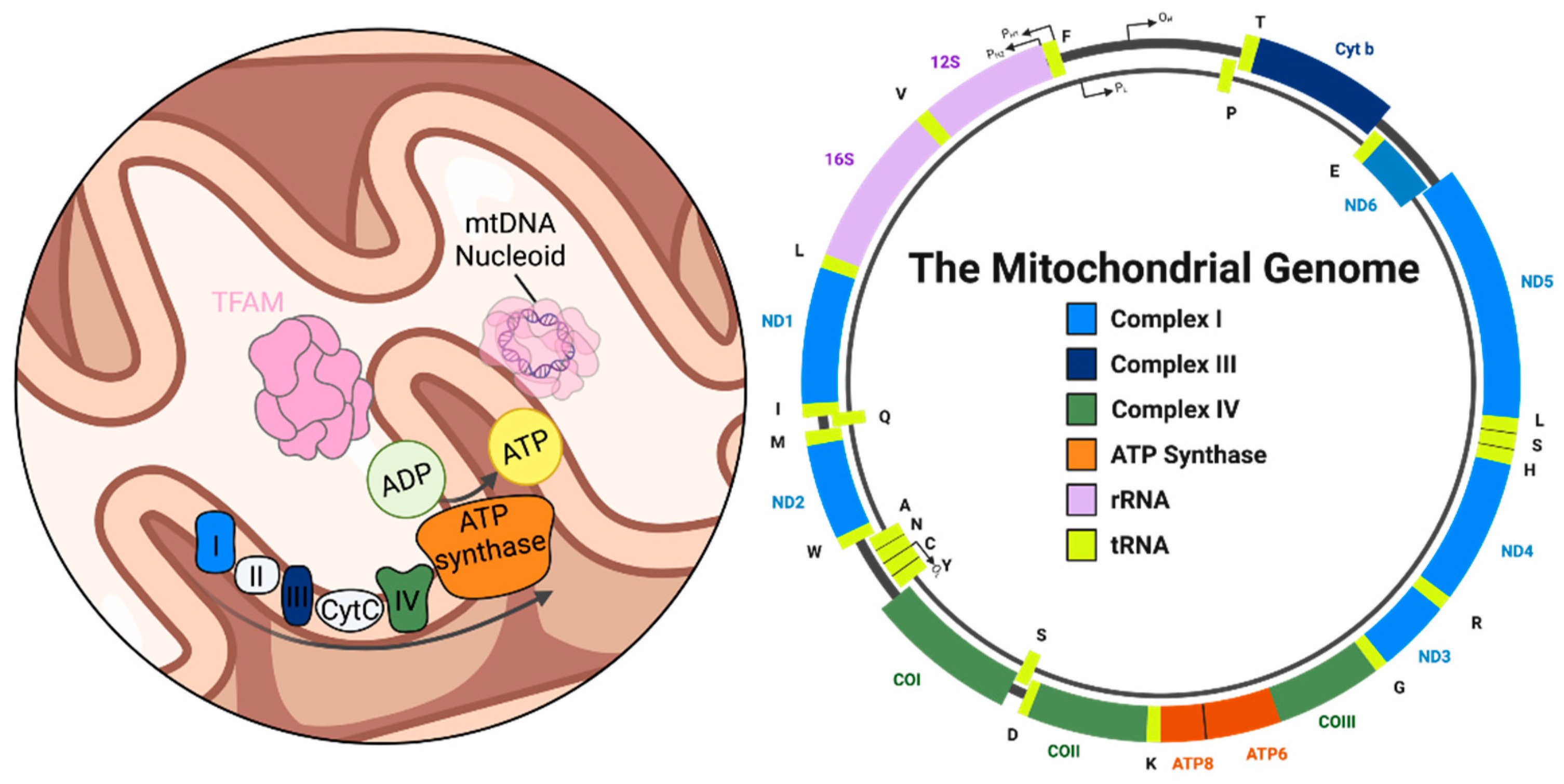

2. Mitochondrial DNA: Structure, Function, and Instability in Neurons

3. Base Excision Repair in Mitochondria: Mechanisms and Enzymes

3.1. Lesion Detection and Removal

3.2. End Processing

3.3. Gap Filling

3.4. Ligation

4. BER Dysfunction: A Delicate Balance in Mitochondrial Genome Maintenance

5. mtDNA Instability as a Trigger for Neuroinflammation

6. Emerging Therapeutic Strategies

7. Conclusions and Future Directions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mattson, M.P.; Gleichmann, M.; Cheng, A. Mitochondria in Neuroplasticity and Neurological Disorders. Neuron 2008, 60, 748–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misgeld, T.; Schwarz, T.L. Mitostasis in Neurons: Maintaining Mitochondria in an Extended Cellular Architecture. Neuron 2017, 96, 651–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogenhagen, D.F. Mitochondrial DNA Nucleoid Structure. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA - Gene Regul. Mech. 2012, 1819, 914–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Druzhyna, N.M.; Wilson, G.L.; LeDoux, S.P. Mitochondrial DNA Repair in Aging and Disease. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2008, 129, 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokolenko, I.; Venediktova, N.; Bochkareva, A.; Wilson, G.L.; Alexeyev, M.F. Oxidative Stress Induces Degradation of Mitochondrial DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, 2539–2548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakes, F.M.; Van Houten, B. Mitochondrial DNA Damage Is More Extensive and Persists Longer than Nuclear DNA Damage in Human Cells Following Oxidative Stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1997, 94, 514–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakabeppu, Y.; Tsuchimoto, D.; Yamaguchi, H.; Sakumi, K. Oxidative Damage in Nucleic Acids and Parkinson’s Disease. J. Neurosci. Res. 2007, 85, 919–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, D.C. A Mitochondrial Paradigm of Metabolic and Degenerative Diseases, Aging, and Cancer: A Dawn for Evolutionary Medicine. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2005, 39, 359–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llanos-González, E.; Henares-Chavarino, Á.A.; Pedrero-Prieto, C.M.; García-Carpintero, S.; Frontiñán-Rubio, J.; Sancho-Bielsa, F.J.; Alcain, F.J.; Peinado, J.R.; Rabanal-Ruíz, Y.; Durán-Prado, M. Interplay Between Mitochondrial Oxidative Disorders and Proteostasis in Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 13, 1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, D.C. A Mitochondrial Etiology of Neuropsychiatric Disorders. JAMA Psychiatry 2017, 74, 863–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossignol, R.; Faustin, B.; Rocher, C.; Malgat, M.; Mazat, J.-P.; Letellier, T. Mitochondrial Threshold Effects. Biochem. J. 2003, 370, 751–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, D.C. Mitochondrial Genetic Medicine. Nat. Genet. 2018, 50, 1642–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, D.C.; Fan, W.; Procaccio, V. Mitochondrial Energetics and Therapeutics. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2010, 5, 297–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnan, K.J.; Reeve, A.K.; Turnbull, D.M. Do Mitochondrial DNA Mutations Have a Role in Neurodegenerative Disease? Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2007, 35, 1232–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallace, D.C.; Lott, M.T.; Shoffner, J.M.; Ballinger, S. Mitochondrial DNA Mutations in Epilepsy and Neurological Disease. Epilepsia 1994, 35 Suppl 1, S43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elfawy, H.A.; Das, B. Crosstalk between Mitochondrial Dysfunction, Oxidative Stress, and Age Related Neurodegenerative Disease: Etiologies and Therapeutic Strategies. Life Sci. 2019, 218, 165–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, A.C.P.; Ferrasa, A.; Muotri, A.R.; Herai, R.H. Frequency and Association of Mitochondrial Genetic Variants with Neurological Disorders. Mitochondrion 2019, 46, 345–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Hunt, C.P.; Sanders, L.H. DNA Damage and Repair in Parkinson’s Disease: Recent Advances and New Opportunities. J. Neurosci. Res. 2021, 99, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kai, Y.; Takamatsu, C.; Tokuda, K.; Okamoto, M.; Irita, K.; Takahashi, S. Rapid and Random Turnover of Mitochondrial DNA in Rat Hepatocytes of Primary Culture. Mitochondrion 2006, 6, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L. Mitochondrial DNA Degradation: A Quality Control Measure for Mitochondrial Genome Maintenance and Stress Response. The Enzymes 2019, 45, 311–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokolenko, I.N.; Wilson, G.L.; Alexeyev, M.F. Persistent Damage Induces Mitochondrial DNA Degradation. DNA Repair 2013, 12, 488–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm, L.P.; Ganley, I.G. Eating Your Mitochondria-When Too Much of a Good Thing Turns Bad. EMBO J. 2023, 42, e114542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, Z.; Tu, P.; Xu, P.; Sun, Y.; Yu, F.; Tu, N.; Guo, L.; Yang, Y. The Mitochondrial Response to DNA Damage. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 669379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazak, L.; Reyes, A.; Holt, I.J. Minimizing the Damage: Repair Pathways Keep Mitochondrial DNA Intact. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012, 13, 659–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prakash, A.; Doublié, S. Base Excision Repair in the Mitochondria. J. Cell. Biochem. 2015, 116, 1490–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gredilla, R. DNA Damage and Base Excision Repair in Mitochondria and Their Role in Aging. J. Aging Res. 2011, 2011, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogenhagen, D.F.; Pinz, K.G.; Perez-Jannotti, R.M. Enzymology of Mitochondrial Base Excision Repair. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 2001, 68, 257–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, M.; Visnes, T.; Krokan, H.E.; Otterlei, M. Mitochondrial Base Excision Repair of Uracil and AP Sites Takes Place by Single-Nucleotide Insertion and Long-Patch DNA Synthesis. DNA Repair 2008, 7, 605–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczesny, B.; Tann, A.W.; Longley, M.J.; Copeland, W.C.; Mitra, S. Long Patch Base Excision Repair in Mammalian Mitochondrial Genomes. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 26349–26356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karahalil, B.; Hogue, B.A.; de Souza-Pinto, N.C.; Bohr, V.A. Base Excision Repair Capacity in Mitochondria and Nuclei: Tissue-Specific Variations. FASEB J. Off. Publ. Fed. Am. Soc. Exp. Biol. 2002, 16, 1895–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart, J.A.; Hashiguchi, K.; Wilson, D.M.; Copeland, W.C.; Souza-Pinto, N.C.; Bohr, V.A. DNA Base Excision Repair Activities and Pathway Function in Mitochondrial and Cellular Lysates from Cells Lacking Mitochondrial DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32, 2181–2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hegde, M.L.; Hazra, T.K.; Mitra, S. Early Steps in the DNA Base Excision/Single-Strand Interruption Repair Pathway in Mammalian Cells. Cell Res. 2008, 18, 27–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, Y.W.; Albarran, E.; Wilson, D.L.; Ding, J.; Kool, E.T. Fluorescence Imaging of Mitochondrial DNA Base Excision Repair Reveals Dynamics of Oxidative Stress Responses. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed Engl. 2022, 61, e202111829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Kim, H.-S.; Chung, J.H. Molecular Mechanisms of Mitochondrial DNA Release and Activation of the cGAS-STING Pathway. Exp. Mol. Med. 2023, 55, 510–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nass, M.M.; Nass, S. INTRAMITOCHONDRIAL FIBERS WITH DNA CHARACTERISTICS. I. FIXATION AND ELECTRON STAINING REACTIONS. J. Cell Biol. 1963, 19, 593–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luck, D.J.; Reich, E. DNA IN MITOCHONDRIA OF NEUROSPORA CRASSA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1964, 52, 931–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schatz, G.; Haslbrunner, E.; Tuppy, H. DEOXYRIBONUCLEIC ACID ASSOCIATED WITH YEAST MITOCHONDRIA. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1964, 15, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, S.; Bankier, A.T.; Barrell, B.G.; De Bruijn, M.H.L.; Coulson, A.R.; Drouin, J.; Eperon, I.C.; Nierlich, D.P.; Roe, B.A.; Sanger, F.; et al. Sequence and Organization of the Human Mitochondrial Genome. Nature 1981, 290, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chomyn, A.; Mariottini, P.; Cleeter, M.W.; Ragan, C.I.; Matsuno-Yagi, A.; Hatefi, Y.; Doolittle, R.F.; Attardi, G. Six Unidentified Reading Frames of Human Mitochondrial DNA Encode Components of the Respiratory-Chain NADH Dehydrogenase. Nature 1985, 314, 592–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chomyn, A.; Cleeter, M.W.; Ragan, C.I.; Riley, M.; Doolittle, R.F.; Attardi, G. URF6, Last Unidentified Reading Frame of Human mtDNA, Codes for an NADH Dehydrogenase Subunit. Science 1986, 234, 614–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, T.; Nagao, A.; Suzuki, T. Human Mitochondrial tRNAs: Biogenesis, Function, Structural Aspects, and Diseases. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2011, 45, 299–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neupert, W.; Herrmann, J.M. Translocation of Proteins into Mitochondria. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2007, 76, 723–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endo, T.; Wiedemann, N. Molecular Machineries and Pathways of Mitochondrial Protein Transport. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2025, 26, 848–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cutter, A.R.; Hayes, J.J. A Brief Review of Nucleosome Structure. FEBS Lett. 2015, 589, 2914–2922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornberg, R.D. Chromatin Structure: A Repeating Unit of Histones and DNA. Science 1974, 184, 868–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogenhagen, D.F.; Rousseau, D.; Burke, S. The Layered Structure of Human Mitochondrial DNA Nucleoids. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 3665–3675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.J.; Butow, R.A. The Organization and Inheritance of the Mitochondrial Genome. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2005, 6, 815–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malka, F.; Lombès, A.; Rojo, M. Organization, Dynamics and Transmission of Mitochondrial DNA: Focus on Vertebrate Nucleoids. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2006, 1763, 463–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucej, M.; Butow, R.A. Evolutionary Tinkering with Mitochondrial Nucleoids. Trends Cell Biol. 2007, 17, 586–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellani, C.A.; Longchamps, R.J.; Sun, J.; Guallar, E.; Arking, D.E. Thinking Outside the Nucleus: Mitochondrial DNA Copy Number in Health and Disease. Mitochondrion 2020, 53, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wai, T.; Ao, A.; Zhang, X.; Cyr, D.; Dufort, D.; Shoubridge, E.A. The Role of Mitochondrial DNA Copy Number in Mammalian Fertility. Biol. Reprod. 2010, 83, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rath, S.P.; Gupta, R.; Todres, E.; Wang, H.; Jourdain, A.A.; Ardlie, K.G.; Calvo, S.E.; Mootha, V.K. Mitochondrial Genome Copy Number Variation across Tissues in Mice and Humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2024, 121, e2402291121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirabayashi, Y.; Lewis, T.L.; Du, Y.; Virga, D.M.; Decker, A.M.; Coceano, G.; Alvelid, J.; Paul, M.A.; Hamilton, S.; Kneis, P.; et al. Most Axonal Mitochondria in Cortical Pyramidal Neurons Lack Mitochondrial DNA and Consume ATP. BioRxiv Prepr. Serv. Biol. 2024, 2024.02.12.579972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuke, S.; Kubota-Sakashita, M.; Kasahara, T.; Shigeyoshi, Y.; Kato, T. Regional Variation in Mitochondrial DNA Copy Number in Mouse Brain. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2011, 1807, 270–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rice, A.C.; Keeney, P.M.; Algarzae, N.K.; Ladd, A.C.; Thomas, R.R.; Bennett, J.P. Mitochondrial DNA Copy Numbers in Pyramidal Neurons Are Decreased and Mitochondrial Biogenesis Transcriptome Signaling Is Disrupted in Alzheimer’s Disease Hippocampi. J. Alzheimers Dis. JAD 2014, 40, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukat, C.; Wurm, C.A.; Spåhr, H.; Falkenberg, M.; Larsson, N.-G.; Jakobs, S. Super-Resolution Microscopy Reveals That Mammalian Mitochondrial Nucleoids Have a Uniform Size and Frequently Contain a Single Copy of mtDNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011, 108, 13534–13539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, S.; Udeshi, N.D.; Deerinck, T.J.; Svinkina, T.; Ellisman, M.H.; Carr, S.A.; Ting, A.Y. Proximity Biotinylation as a Method for Mapping Proteins Associated with mtDNA in Living Cells. Cell Chem. Biol. 2017, 24, 404–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, B.A.; Durisic, N.; Mativetsky, J.M.; Costantino, S.; Hancock, M.A.; Grutter, P.; Shoubridge, E.A. The Mitochondrial Transcription Factor TFAM Coordinates the Assembly of Multiple DNA Molecules into Nucleoid-like Structures. Mol. Biol. Cell 2007, 18, 3225–3236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Wang, W.; Wang, B.; Shi, Q. The Protective Mechanism of TFAM on Mitochondrial DNA and Its Role in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Mol. Neurobiol. 2024, 61, 4381–4390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alam, T.I.; Kanki, T.; Muta, T.; Ukaji, K.; Abe, Y.; Nakayama, H.; Takio, K.; Hamasaki, N.; Kang, D. Human Mitochondrial DNA Is Packaged with TFAM. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003, 31, 1640–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macuada, J.; Molina-Riquelme, I.; Eisner, V. How Are Mitochondrial Nucleoids Trafficked? Trends Cell Biol. 2025, 35, 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, C.; Park, J.W.; Ames, B.N. Normal Oxidative Damage to Mitochondrial and Nuclear DNA Is Extensive. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1988, 85, 6465–6467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, D.E.; Copeland, W.C. DNA Repair Pathways in the Mitochondria. DNA Repair 2025, 146, 103814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontana, G.A.; Gahlon, H.L. Mechanisms of Replication and Repair in Mitochondrial DNA Deletion Formation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, 11244–11258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takao, M.; Aburatani, H.; Kobayashi, K.; Yasui, A. Mitochondrial Targeting of Human DNA Glycosylases for Repair of Oxidative DNA Damage. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998, 26, 2917–2922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Deng, H.; Li, B.; Chen, J.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, X.; Yoshida, S.; Zhou, Y. Mitochondrial Diseases: From Molecular Mechanisms to Therapeutic Advances. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles, R.E.; Blanc, H.; Cann, H.M.; Wallace, D.C. Maternal Inheritance of Human Mitochondrial DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1980, 77, 6715–6719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cree, L.M.; Samuels, D.C.; Chinnery, P.F. The Inheritance of Pathogenic Mitochondrial DNA Mutations. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2009, 1792, 1097–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vadakedath, S.; Kandi, V.; Ca, J.; Vijayan, S.; Achyut, K.C.; Uppuluri, S.; Reddy, P.K.K.; Ramesh, M.; Kumar, P.P. Mitochondrial Deoxyribonucleic Acid (mtDNA), Maternal Inheritance, and Their Role in the Development of Cancers: A Scoping Review. Cureus 2023, 15, e39812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copeland, W.C. Defects of Mitochondrial DNA Replication. J. Child Neurol. 2014, 29, 1216–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viscomi, C.; Zeviani, M. MtDNA-Maintenance Defects: Syndromes and Genes. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2017, 40, 587–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Copeland, W.C. Inherited Mitochondrial Diseases of DNA Replication. Annu. Rev. Med. 2008, 59, 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, R.X.; Correia, S.C.; Zhu, X.; Smith, M.A.; Moreira, P.I.; Castellani, R.J.; Nunomura, A.; Perry, G. Mitochondrial DNA Oxidative Damage and Repair in Aging and Alzheimer’s Disease. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2013, 18, 2444–2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, M.-Y.; Kim, D.K.; Mook-Jung, I. The Role of Mitochondrial DNA Mutation on Neurodegenerative Diseases. Exp. Mol. Med. 2015, 47, e150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mecocci, P.; MacGarvey, U.; Kaufman, A.E.; Koontz, D.; Shoffner, J.M.; Wallace, D.C.; Beal, M.F. Oxidative Damage to Mitochondrial DNA Shows Marked Age-Dependent Increases in Human Brain. Ann. Neurol. 1993, 34, 609–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damas, J.; Samuels, D.C.; Carneiro, J.; Amorim, A.; Pereira, F. Mitochondrial DNA Rearrangements in Health and Disease--a Comprehensive Study. Hum. Mutat. 2014, 35, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissanka, N.; Moraes, C.T. Mitochondrial DNA Damage and Reactive Oxygen Species in Neurodegenerative Disease. FEBS Lett. 2018, 592, 728–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krokan, H.E.; Bjoras, M. Base Excision Repair. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2013, 5, a012583–a012583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.; Hamasaki, N. Mitochondrial Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial DNA. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2003, 41, 1281–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindahl, T. Instability and Decay of the Primary Structure of DNA. Nature 1993, 362, 709–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mol, C.D.; Parikh, S.S.; Putnam, C.D.; Lo, T.P.; Tainer, J.A. DNA Repair Mechanisms for the Recognition and Removal of Damaged DNA Bases. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 1999, 28, 101–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stivers, J.T.; Jiang, Y.L. A Mechanistic Perspective on the Chemistry of DNA Repair Glycosylases. Chem. Rev. 2003, 103, 2729–2759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeberg, E.; Eide, L.; Bjørås, M. The Base Excision Repair Pathway. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1995, 20, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, A.L.; Schär, P. DNA Glycosylases: In DNA Repair and Beyond. Chromosoma 2012, 121, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schormann, N.; Ricciardi, R.; Chattopadhyay, D. Uracil-DNA Glycosylases-Structural and Functional Perspectives on an Essential Family of DNA Repair Enzymes. Protein Sci. Publ. Protein Soc. 2014, 23, 1667–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bharati, S.; Krokan, H.E.; Kristiansen, L.; Otterlei, M.; Slupphaug, G. Human Mitochondrial Uracil-DNA Glycosylase Preform (UNG1) Is Processed to Two Forms One of Which Is Resistant to Inhibition by AP Sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998, 26, 4953–4959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalhus, B.; Helle, I.H.; Backe, P.H.; Alseth, I.; Rognes, T.; Bjørås, M.; Laerdahl, J.K. Structural Insight into Repair of Alkylated DNA by a New Superfamily of DNA Glycosylases Comprising HEAT-like Repeats. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, 2451–2459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Loon, B.; Samson, L.D. Alkyladenine DNA Glycosylase (AAG) Localizes to Mitochondria and Interacts with Mitochondrial Single-Stranded Binding Protein (mtSSB). DNA Repair 2013, 12, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, T.R. Purification and Characterization of Human 3-Methyladenine-DNA Glycosylase. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993, 21, 5561–5569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitaker, A.M.; Schaich, M.A.; Smith, M.R.; Flynn, T.S.; Freudenthal, B.D. Base Excision Repair of Oxidative DNA Damage: From Mechanism to Disease. Front. Biosci. Landmark Ed. 2017, 22, 1493–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trasviña-Arenas, C.H.; Demir, M.; Lin, W.-J.; David, S.S. Structure, Function and Evolution of the Helix-Hairpin-Helix DNA Glycosylase Superfamily: Piecing Together the Evolutionary Puzzle of DNA Base Damage Repair Mechanisms. DNA Repair 2021, 108, 103231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, S.; Biswas, T.; Roy, R.; Izumi, T.; Boldogh, I.; Kurosky, A.; Sarker, A.H.; Seki, S.; Mitra, S. Purification and Characterization of Human NTH1, a Homolog of Escherichia Coli Endonuclease III. Direct Identification of Lys-212 as the Active Nucleophilic Residue. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 21585–21593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aburatani, H.; Hippo, Y.; Ishida, T.; Takashima, R.; Matsuba, C.; Kodama, T.; Takao, M.; Yasui, A.; Yamamoto, K.; Asano, M. Cloning and Characterization of Mammalian 8-Hydroxyguanine-Specific DNA Glycosylase/Apurinic, Apyrimidinic Lyase, a Functional mutM Homologue. Cancer Res. 1997, 57, 2151–2156. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fromme, J.C.; Banerjee, A.; Huang, S.J.; Verdine, G.L. Structural Basis for Removal of Adenine Mispaired with 8-Oxoguanine by MutY Adenine DNA Glycosylase. Nature 2004, 427, 652–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandaru, V. A Novel Human DNA Glycosylase That Removes Oxidative DNA Damage and Is Homologous to Escherichia Coli Endonuclease VIII. DNA Repair 2002, 1, 517–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazra, T.K.; Kow, Y.W.; Hatahet, Z.; Imhoff, B.; Boldogh, I.; Mokkapati, S.K.; Mitra, S.; Izumi, T. Identification and Characterization of a Novel Human DNA Glycosylase for Repair of Cytosine-Derived Lesions. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 30417–30420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Doublié, S.; Wallace, S.S. Neil3, the Final Frontier for the DNA Glycosylases That Recognize Oxidative Damage. Mutat. Res. 2013, 743–744, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Krishnamurthy, N.; Burrows, C.J.; David, S.S. Mutation versus Repair: NEIL1 Removal of Hydantoin Lesions in Single-Stranded, Bulge, Bubble, and Duplex DNA Contexts. Biochemistry 2010, 49, 1658–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hailer, M.K.; Slade, P.G.; Martin, B.D.; Rosenquist, T.A.; Sugden, K.D. Recognition of the Oxidized Lesions Spiroiminodihydantoin and Guanidinohydantoin in DNA by the Mammalian Base Excision Repair Glycosylases NEIL1 and NEIL2. DNA Repair 2005, 4, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minko, I.G.; Christov, P.P.; Li, L.; Stone, M.P.; McCullough, A.K.; Lloyd, R.S. Processing of N5-Substituted Formamidopyrimidine DNA Adducts by DNA Glycosylases NEIL1 and NEIL3. DNA Repair 2019, 73, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, H.; Mitra, S.; Hazra, T.K. Repair of Oxidized Bases in DNA Bubble Structures by Human DNA Glycosylases NEIL1 and NEIL2. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 49679–49684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, D.; Mandal, S.M.; Das, A.; Hegde, M.L.; Das, S.; Bhakat, K.K.; Boldogh, I.; Sarkar, P.S.; Mitra, S.; Hazra, T.K. Preferential Repair of Oxidized Base Damage in the Transcribed Genes of Mammalian Cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 6006–6016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maynard, S.; Schurman, S.H.; Harboe, C.; de Souza-Pinto, N.C.; Bohr, V.A. Base Excision Repair of Oxidative DNA Damage and Association with Cancer and Aging. Carcinogenesis 2009, 30, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tahbaz, N.; Subedi, S.; Weinfeld, M. Role of Polynucleotide Kinase/Phosphatase in Mitochondrial DNA Repair. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, 3484–3495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhong, Z.; Zhu, J.; Xiang, D.; Dai, N.; Cao, X.; Qing, Y.; Yang, Z.; Xie, J.; Li, Z.; et al. Identification and Characterization of Mitochondrial Targeting Sequence of Human Apurinic/Apyrimidinic Endonuclease 1. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 14871–14881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Qian, L.; Sung, J.-S.; de Souza-Pinto, N.C.; Zheng, L.; Bogenhagen, D.F.; Bohr, V.A.; Wilson, D.M.; Shen, B.; Demple, B. Removal of Oxidative DNA Damage via FEN1-Dependent Long-Patch Base Excision Repair in Human Cell Mitochondria. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2008, 28, 4975–4987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copeland, W.C. The Mitochondrial DNA Polymerase in Health and Disease. Subcell. Biochem. 2010, 50, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasich, R.; Copeland, W.C. DNA Polymerases in the Mitochondria: A Critical Review of the Evidence. Front. Biosci. Landmark Ed. 2017, 22, 692–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sykora, P.; Kanno, S.; Akbari, M.; Kulikowicz, T.; Baptiste, B.A.; Leandro, G.S.; Lu, H.; Tian, J.; May, A.; Becker, K.A.; et al. DNA Polymerase Beta Participates in Mitochondrial DNA Repair. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2017, 37, e00237-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, R.; Çağlayan, M.; Dai, D.-P.; Nadalutti, C.A.; Zhao, M.-L.; Gassman, N.R.; Janoshazi, A.K.; Stefanick, D.F.; Horton, J.K.; Krasich, R.; et al. DNA Polymerase β: A Missing Link of the Base Excision Repair Machinery in Mammalian Mitochondria. DNA Repair 2017, 60, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptiste, B.A.; Baringer, S.L.; Kulikowicz, T.; Sommers, J.A.; Croteau, D.L.; Brosh, R.M.; Bohr, V.A. DNA Polymerase β Outperforms DNA Polymerase γ in Key Mitochondrial Base Excision Repair Activities. DNA Repair 2021, 99, 103050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Demple, B. DNA Repair in Mammalian Mitochondria: Much More than We Thought? Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 2010, 51, 417–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De, A.; Campbell, C. A Novel Interaction between DNA Ligase III and DNA Polymerase Gamma Plays an Essential Role in Mitochondrial DNA Stability. Biochem. J. 2007, 402, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vartanian, V.; Lowell, B.; Minko, I.G.; Wood, T.G.; Ceci, J.D.; George, S.; Ballinger, S.W.; Corless, C.L.; McCullough, A.K.; Lloyd, R.S. The Metabolic Syndrome Resulting from a Knockout of the NEIL1 DNA Glycosylase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006, 103, 1864–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza-Pinto, N.C.; Eide, L.; Hogue, B.A.; Thybo, T.; Stevnsner, T.; Seeberg, E.; Klungland, A.; Bohr, V.A. Repair of 8-Oxodeoxyguanosine Lesions in Mitochondrial Dna Depends on the Oxoguanine Dna Glycosylase (OGG1) Gene and 8-Oxoguanine Accumulates in the Mitochondrial Dna of OGG1-Defective Mice. Cancer Res. 2001, 61, 5378–5381. [Google Scholar]

- Ruchko, M.V.; Gorodnya, O.M.; Zuleta, A.; Pastukh, V.M.; Gillespie, M.N. The DNA Glycosylase Ogg1 Defends against Oxidant-Induced mtDNA Damage and Apoptosis in Pulmonary Artery Endothelial Cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2011, 50, 1107–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, P.; Zhou, K.; Zhang, W.; Liu, S.; Ouyang, J.; Bai, M.; Ding, G.; Huang, S.; Jia, Z.; et al. HUWE1-Mediated Degradation of MUTYH Facilitates DNA Damage and Mitochondrial Dysfunction to Promote Acute Kidney Injury. Adv. Sci. Weinh. Baden-Wurtt. Ger. 2025, 12, e2412250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, R.S. Complex Roles of NEIL1 and OGG1: Insights Gained from Murine Knockouts and Human Polymorphic Variants. DNA 2022, 2, 279–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, D.; Schomacher, L.; Schüle, K.M.; Mallick, M.; Musheev, M.U.; Karaulanov, E.; Krebs, L.; von Seggern, A.; Niehrs, C. NEIL1 and NEIL2 DNA Glycosylases Protect Neural Crest Development against Mitochondrial Oxidative Stress. eLife 2019, 8, e49044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Esbensen, Y.; Kunke, D.; Suganthan, R.; Rachek, L.; Bjørås, M.; Eide, L. Mitochondrial DNA Damage Level Determines Neural Stem Cell Differentiation Fate. J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci. 2011, 31, 9746–9751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weren, R.D.A.; Ligtenberg, M.J.L.; Kets, C.M.; de Voer, R.M.; Verwiel, E.T.P.; Spruijt, L.; van Zelst-Stams, W.A.G.; Jongmans, M.C.; Gilissen, C.; Hehir-Kwa, J.Y.; et al. A Germline Homozygous Mutation in the Base-Excision Repair Gene NTHL1 Causes Adenomatous Polyposis and Colorectal Cancer. Nat. Genet. 2015, 47, 668–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Tassan, N.; Chmiel, N.H.; Maynard, J.; Fleming, N.; Livingston, A.L.; Williams, G.T.; Hodges, A.K.; Davies, D.R.; David, S.S.; Sampson, J.R.; et al. Inherited Variants of MYH Associated with Somatic G. Nat. Genet. 2002, 30, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sieber, O.M.; Lipton, L.; Crabtree, M.; Heinimann, K.; Fidalgo, P.; Phillips, R.K.S.; Bisgaard, M.-L.; Orntoft, T.F.; Aaltonen, L.A.; Hodgson, S.V.; et al. Multiple Colorectal Adenomas, Classic Adenomatous Polyposis, and Germ-Line Mutations in MYH. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 791–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonelli, V.; Narciso, L.; Dogliotti, E.; Fortini, P. Base Excision Repair Intermediates Are Mutagenic in Mammalian Cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005, 33, 4404–4411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, G.K.; Russell, W.K.; Garg, N.J.; Yin, Y.W. Poly(ADP-Ribose) Polymerase 1 Regulates Mitochondrial DNA Repair in an NAD-Dependent Manner. J. Biol. Chem. 2021, 296, 100309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teoh, P.J.; An, O.; Chung, T.-H.; Chooi, J.Y.; Toh, S.H.M.; Fan, S.; Wang, W.; Koh, B.T.H.; Fullwood, M.J.; Ooi, M.G.; et al. Aberrant Hyperediting of the Myeloma Transcriptome by ADAR1 Confers Oncogenicity and Is a Marker of Poor Prognosis. Blood 2018, 132, 1304–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishel, M.L.; Seo, Y.R.; Smith, M.L.; Kelley, M.R. Imbalancing the DNA Base Excision Repair Pathway in the Mitochondria; Targeting and Overexpressing N-Methylpurine DNA Glycosylase in Mitochondria Leads to Enhanced Cell Killing. Cancer Res. 2003, 63, 608–615. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Li, C.; Qiao, P.; Xue, Y.; Zheng, X.; Chen, H.; Zeng, X.; Liu, W.; Boldogh, I.; Ba, X. OGG1-Initiated Base Excision Repair Exacerbates Oxidative Stress-Induced Parthanatos. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobson, A.W.; Grishko, V.; LeDoux, S.P.; Kelley, M.R.; Wilson, G.L.; Gillespie, M.N. Enhanced mtDNA Repair Capacity Protects Pulmonary Artery Endothelial Cells from Oxidant-Mediated Death. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2002, 283, L205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Dawson, V.L.; Dawson, T.M. Poly(ADP-Ribose) Signals to Mitochondrial AIF: A Key Event in Parthanatos. Exp. Neurol. 2009, 218, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawson, V.L.; Dawson, T.M. Deadly Conversations: Nuclear-Mitochondrial Cross-Talk. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 2004, 36, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nastasi, C.; Mannarino, L.; D’Incalci, M. DNA Damage Response and Immune Defense. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Goewey Ruiz, J.A.; Sebastian, M.; Kidane, D. Defective DNA Polymerase Beta Invoke a Cytosolic DNA Mediated Inflammatory Response. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1039009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, K.; Chen, T.; Fang, H.; Shen, X.; Tang, Z.; Zhao, J. Mitochondrial DNA Release via the Mitochondrial Permeability Transition Pore Activates the cGAS-STING Pathway, Exacerbating Inflammation in Acute Kawasaki Disease. Cell Commun. Signal. CCS 2024, 22, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patrushev, M.; Kasymov, V.; Patrusheva, V.; Ushakova, T.; Gogvadze, V.; Gaziev, A. Mitochondrial Permeability Transition Triggers the Release of mtDNA Fragments. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. CMLS 2004, 61, 3100–3103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakahira, K.; Haspel, J.A.; Rathinam, V.A.K.; Lee, S.-J.; Dolinay, T.; Lam, H.C.; Englert, J.A.; Rabinovitch, M.; Cernadas, M.; Kim, H.P.; et al. Autophagy Proteins Regulate Innate Immune Responses by Inhibiting the Release of Mitochondrial DNA Mediated by the NALP3 Inflammasome. Nat. Immunol. 2011, 12, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimada, K.; Crother, T.R.; Karlin, J.; Dagvadorj, J.; Chiba, N.; Chen, S.; Ramanujan, V.K.; Wolf, A.J.; Vergnes, L.; Ojcius, D.M.; et al. Oxidized Mitochondrial DNA Activates the NLRP3 Inflammasome during Apoptosis. Immunity 2012, 36, 401–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.; Liu, N.; Qin, Z.; Wang, Y. Mitochondrial-Derived Damage-Associated Molecular Patterns Amplify Neuroinflammation in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2022, 43, 2439–2447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, H.M.; Weidling, I.W.; Ji, Y.; Swerdlow, R.H. Mitochondria-Derived Damage-Associated Molecular Patterns in Neurodegeneration. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, S.; Fu, X.; Cai, H.; Ren, Z.; Xu, Y.; Jia, L. The Neuroimmune Nexus: Unraveling the Role of the mtDNA-cGAS-STING Signal Pathway in Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol. Neurodegener. 2025, 20, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McArthur, K.; Whitehead, L.W.; Heddleston, J.M.; Li, L.; Padman, B.S.; Oorschot, V.; Geoghegan, N.D.; Chappaz, S.; Davidson, S.; San Chin, H.; et al. BAK/BAX Macropores Facilitate Mitochondrial Herniation and mtDNA Efflux during Apoptosis. Science 2018, 359, eaao6047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tait, S.W.G.; Green, D.R. Mitochondrial Regulation of Cell Death. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2013, 5, a008706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crompton, M. The Mitochondrial Permeability Transition Pore and Its Role in Cell Death. Biochem. J. 1999, 341 Pt 2, 233–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Gupta, R.; Blanco, L.P.; Yang, S.; Shteinfer-Kuzmine, A.; Wang, K.; Zhu, J.; Yoon, H.E.; Wang, X.; Kerkhofs, M.; et al. VDAC Oligomers Form Mitochondrial Pores to Release mtDNA Fragments and Promote Lupus-like Disease. Science 2019, 366, 1531–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takamatsu, H. Mitochondrial DNA: Leakage, Recognition and Associated Human Diseases. J. Biochem. (Tokyo) 2025, 178, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, W.; Xiang, W.; He, S.; Hayashi, T.; Mizuno, K.; Hattori, S.; Fujisaki, H.; Ikejima, T. Impaired Mitophagy Causes Mitochondrial DNA Leakage and STING Activation in Ultraviolet B-Irradiated Human Keratinocytes HaCaT. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2023, 737, 109553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, W.; Rao, Z.; Xu, J.; Sun, Y.; Hu, H.; Wang, P.; Xia, Y.; Pan, X.; Tang, W.; Chen, Z.; et al. Defective Mitophagy in Aged Macrophages Promotes Mitochondrial DNA Cytosolic Leakage to Activate STING Signaling during Liver Sterile Inflammation. Aging Cell 2022, 21, e13622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.; Wei, H.; Zhao, A.; Yan, X.; Zhang, X.; Gan, J.; Guo, M.; Wang, J.; Zhang, F.; Jiang, Y.; et al. Mitochondrial DNA Leakage: Underlying Mechanisms and Therapeutic Implications in Neurological Disorders. J. Neuroinflammation 2025, 22, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, L.E.; Weiser Novak, S.; Rojas, G.R.; Tadepalle, N.; Schiavon, C.R.; Grotjahn, D.A.; Towers, C.G.; Tremblay, M.-È.; Donnelly, M.P.; Ghosh, S.; et al. Mitochondrial DNA Replication Stress Triggers a Pro-Inflammatory Endosomal Pathway of Nucleoid Disposal. Nat. Cell Biol. 2024, 26, 194–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Hu, X. cGAS-STING-Mediated Inflammation and Neurodegeneration as a Strategy for the Treatment of Neurodegenerative Diseases. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 2024, 56, 148–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Yang, L.; Wang, K.; Chen, Z.; Liu, H.; Yang, X.; Xu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gong, Z.; Jia, Y. Oxidized Mitochondrial DNA Activates the cGAS-STING Pathway in the Neuronal Intrinsic Immune System after Brain Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury. Neurother. J. Am. Soc. Exp. Neurother. 2024, 21, e00368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xian, H.; Watari, K.; Sanchez-Lopez, E.; Offenberger, J.; Onyuru, J.; Sampath, H.; Ying, W.; Hoffman, H.M.; Shadel, G.S.; Karin, M. Oxidized DNA Fragments Exit Mitochondria via mPTP- and VDAC-Dependent Channels to Activate NLRP3 Inflammasome and Interferon Signaling. Immunity 2022, 55, 1370–1385.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Liu, B.; Xu, L.; Yu, S.; Fu, J.; Wang, J.; Yan, X.; Su, J. ROS-Induced mtDNA Release: The Emerging Messenger for Communication between Neurons and Innate Immune Cells during Neurodegenerative Disorder Progression. Antioxid. Basel Switz. 2021, 10, 1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, B.; Duan, R.; Liu, Y. Mitochondrial DNA Leakage and cGas/STING Pathway in Microglia: Crosstalk Between Neuroinflammation and Neurodegeneration. Neuroscience 2024, 548, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.; Li, L.; Chen, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhu, D.; Cui, J. Mitochondrial DNA Drives Neuroinflammation through the cGAS-IFN Signaling Pathway in the Spinal Cord of Neuropathic Pain Mice. Open Life Sci. 2024, 19, 20220872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Xiao, D.; Mao, Q.; Xia, H. Role of Neuroinflammation in Neurodegeneration Development. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, K.; Wang, Z.; Gao, B.; Li, L.; Gu, F.; Tao, X.; You, W.; Wang, Z. APE1 Regulates Mitochondrial DNA Damage Repair after Experimental Subarachnoid Haemorrhage in Vivo and in Vitro. Stroke Vasc. Neurol. 2024, 9, 230–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.; Chu, X.; Duan Sahbaz, B.; Gray, S.; Pekhale, K.; Park, J.-H.; Croteau, D.L.; Bohr, V.A. Mitochondrial OGG1 Expression Reduces Age-Associated Neuroinflammation by Regulating Cytosolic Mitochondrial DNA. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2023, 203, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, H.; Yan, S.S. Mitochondrial Medicine for Neurodegenerative Diseases. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2010, 42, 560–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garone, C.; Viscomi, C. Towards a Therapy for Mitochondrial Disease: An Update. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2018, 46, 1247–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blázquez-Bermejo, C.; Carreño-Gago, L.; Molina-Granada, D.; Aguirre, J.; Ramón, J.; Torres-Torronteras, J.; Cabrera-Pérez, R.; Martín, M.Á.; Domínguez-González, C.; de la Cruz, X.; et al. Increased dNTP Pools Rescue mtDNA Depletion in Human POLG-Deficient Fibroblasts. FASEB J. Off. Publ. Fed. Am. Soc. Exp. Biol. 2019, 33, 7168–7179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Z.; Zhang, X.; Tang, W.; Yu, Y.; Wei, X.; Zhang, X.; Wei, W. Strand-Selective Base Editing of Human Mitochondrial DNA Using mitoBEs. Nat. Biotechnol. 2024, 42, 498–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joore, I.P.; Shehata, S.; Muffels, I.; Castro-Alpízar, J.; Jiménez-Curiel, E.; Nagyova, E.; Levy, N.; Tang, Z.; Smit, K.; Vermeij, W.P.; et al. Correction of Pathogenic Mitochondrial DNA in Patient-Derived Disease Models Using Mitochondrial Base Editors. PLoS Biol. 2025, 23, e3003207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falkenberg, M.; Hirano, M. Editing the Mitochondrial Genome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 1489–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Lee, H.; Baek, G.; Kim, J.-S. Precision Mitochondrial DNA Editing with High-Fidelity DddA-Derived Base Editors. Nat. Biotechnol. 2023, 41, 378–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, K. Mitochondrial Genome Editing: Strategies, Challenges, and Applications. BMB Rep. 2024, 57, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraes, C.T. Tools for Editing the Mammalian Mitochondrial Genome. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2024, 33, R92–R99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gammage, P.A.; Viscomi, C.; Simard, M.-L.; Costa, A.S.H.; Gaude, E.; Powell, C.A.; Van Haute, L.; McCann, B.J.; Rebelo-Guiomar, P.; Cerutti, R.; et al. Genome Editing in Mitochondria Corrects a Pathogenic mtDNA Mutation in Vivo. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 1691–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gammage, P.A.; Gaude, E.; Van Haute, L.; Rebelo-Guiomar, P.; Jackson, C.B.; Rorbach, J.; Pekalski, M.L.; Robinson, A.J.; Charpentier, M.; Concordet, J.-P.; et al. Near-Complete Elimination of Mutant mtDNA by Iterative or Dynamic Dose-Controlled Treatment with mtZFNs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, 7804–7816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, X.; Jiang, P.; Wang, Z.; Kong, W.; Feng, L. Mitochondrial Transplantation: A Novel Therapeutic Approach for Treating Diseases. MedComm 2025, 6, e70253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCully, J.D.; Del Nido, P.J.; Emani, S.M. Mitochondrial Transplantation: The Advance to Therapeutic Application and Molecular Modulation. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 10, 1268814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clemente-Suárez, V.J.; Martín-Rodríguez, A.; Yáñez-Sepúlveda, R.; Tornero-Aguilera, J.F. Mitochondrial Transfer as a Novel Therapeutic Approach in Disease Diagnosis and Treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 8848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.S.; Lee, S.; Kim, W.-K.; Han, B.-S. Mitochondrial Transplantation: An Overview of a Promising Therapeutic Approach. BMB Rep. 2023, 56, 488–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.-G.; Miao, C.-Y. Mitochondrial Transplantation as a Promising Therapy for Mitochondrial Diseases. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2023, 13, 1028–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.M.; Paez, H.G.; Pitzer, C.R.; Alway, S.E. The Therapeutic Potential of Mitochondria Transplantation Therapy in Neurodegenerative and Neurovascular Disorders. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2023, 21, 1100–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eo, H.; Yu, S.-H.; Choi, Y.; Kim, Y.; Kang, Y.C.; Lee, H.; Kim, J.H.; Han, K.; Lee, H.K.; Chang, M.-Y.; et al. Mitochondrial Transplantation Exhibits Neuroprotective Effects and Improves Behavioral Deficits in an Animal Model of Parkinson’s Disease. Neurother. J. Am. Soc. Exp. Neurother. 2024, 21, e00355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riou, A.; Broeglin, A.; Grimm, A. Mitochondrial Transplantation in Brain Disorders: Achievements, Methods, and Challenges. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2025, 169, 105971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.-J.; Zheng, Q.-W.; Zheng, J.; Zhang, J.-B.; Liu, H.; Tie, J.-J.; Zhang, K.-L.; Wu, F.-F.; Li, X.-D.; Zhang, S.; et al. Mitochondria Transplantation Transiently Rescues Cerebellar Neurodegeneration Improving Mitochondrial Function and Reducing Mitophagy in Mice. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 2839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fields, M.; Marcuzzi, A.; Gonelli, A.; Celeghini, C.; Maximova, N.; Rimondi, E. Mitochondria-Targeted Antioxidants, an Innovative Class of Antioxidant Compounds for Neurodegenerative Diseases: Perspectives and Limitations. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmpilas, N.; Fang, E.F.; Palikaras, K. Mitophagy and Neuroinflammation: A Compelling Interplay. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2023, 21, 1477–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Wang, J.; Yu, L.; Qiao, G.; Qin, D.; Yuen-Kwan Law, B.; Ren, F.; Wu, J.; Wu, A. Mitophagy and cGAS-STING Crosstalk in Neuroinflammation. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2024, 14, 3327–3361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, E.F.; Hou, Y.; Palikaras, K.; Adriaanse, B.A.; Kerr, J.S.; Yang, B.; Lautrup, S.; Hasan-Olive, M.M.; Caponio, D.; Dan, X.; et al. Mitophagy Inhibits Amyloid-β and Tau Pathology and Reverses Cognitive Deficits in Models of Alzheimer’s Disease. Nat. Neurosci. 2019, 22, 401–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagunas-Rangel, F.A. Sirtuins in Mitophagy: Key Gatekeepers of Mitochondrial Quality. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2025, 480, 5877–5896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.-B.; Liu, Y.-X.; Hu, Z.-W.; Luo, H.-Y.; Zhang, S.; Shi, C.-H.; Xu, Y.-M. Study Insights in the Role of PGC-1α in Neurological Diseases: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Potential. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2024, 16, 1454735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Liu, Y.-Y.; Li, L.-S.; Liu, Y.-S. Sirtuins at the Crossroads between Mitochondrial Quality Control and Neurodegenerative Diseases: Structure, Regulation, Modifications, and Modulators. Aging Dis. 2023, 14, 794–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golpich, M.; Amini, E.; Mohamed, Z.; Azman Ali, R.; Mohamed Ibrahim, N.; Ahmadiani, A. Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Biogenesis in Neurodegenerative Diseases: Pathogenesis and Treatment. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2017, 23, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakshe, P.S.; Dutta, B.J.; Chib, S.; Maurya, N.; Singh, S. Unveiling the Interplay of AMPK/SIRT1/PGC-1α Axis in Brain Health: Promising Targets against Aging and NDDs. Ageing Res. Rev. 2024, 96, 102255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Deng, Q.; Chen, X. Mitophagy-Associated Programmed Neuronal Death and Neuroinflammation. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1460286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Liu, B.; Sinha, S.C.; Amin, S.; Gan, L. Mechanism and Therapeutic Potential of Targeting cGAS-STING Signaling in Neurological Disorders. Mol. Neurodegener. 2023, 18, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinkle, J.T.; Patel, J.; Panicker, N.; Karuppagounder, S.S.; Biswas, D.; Belingon, B.; Chen, R.; Brahmachari, S.; Pletnikova, O.; Troncoso, J.C.; et al. STING Mediates Neurodegeneration and Neuroinflammation in Nigrostriatal α-Synucleinopathy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2022, 119, e2118819119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.; Jeong, J.-H.; Park, J.-C.; Han, J.W.; Lee, Y.; Kim, J.-I.; Mook-Jung, I. Blockade of STING Activation Alleviates Microglial Dysfunction and a Broad Spectrum of Alzheimer’s Disease Pathologies. Exp. Mol. Med. 2024, 56, 1936–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fryer, A.L.; Abdullah, A.; Mobilio, F.; Jobling, A.; Moore, Z.; de Veer, M.; Zheng, G.; Wong, B.X.; Taylor, J.M.; Crack, P.J. Pharmacological Inhibition of STING Reduces Neuroinflammation-Mediated Damage Post-Traumatic Brain Injury. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2024, 181, 3118–3135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; He, Z.; Yin, C.; Yang, S.; Li, J.; Lin, H.; Hu, G.; Wu, A.; Qin, D.; Hu, G.; et al. STING-Mediated Neuroinflammation: A Therapeutic Target in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2025, 17, 1659216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Q.-Q.; Le, W. NLRP3 Inflammasome-Mediated Neuroinflammation and Related Mitochondrial Impairment in Parkinson’s Disease. Neurosci. Bull. 2023, 39, 832–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auger, A.; Faidi, R.; Rickman, A.D.; Martinez, C.P.; Fajfer, A.; Carling, J.; Hilyard, A.; Ali, M.; Ono, R.; Cleveland, C.; et al. Post-Symptomatic NLRP3 Inhibition Rescues Cognitive Impairment and Mitigates Amyloid and Tau Driven Neurodegeneration. NPJ Dement. 2025, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, L.; Liu, Y.-Z.; Shen, X.-L.; Wu, T.-Y.; Zhang, T.; Wang, W.; Wang, Y.-X.; Jiang, C.-L. NLRP3 Inflammasome Mediates Chronic Mild Stress-Induced Depression in Mice via Neuroinflammation. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015, 18, pyv006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramalingam, V. NLRP3 Inhibitors: Unleashing Their Therapeutic Potential against Inflammatory Diseases. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2023, 218, 115915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczesny, B.; Brunyanszki, A.; Olah, G.; Mitra, S.; Szabo, C. Opposing Roles of Mitochondrial and Nuclear PARP1 in the Regulation of Mitochondrial and Nuclear DNA Integrity: Implications for the Regulation of Mitochondrial Function. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, 13161–13173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallyas, F.; Sumegi, B. Mitochondrial Protection by PARP Inhibition. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, K.; Zhang, G. The Role of PARP1 in Neurodegenerative Diseases and Aging. FEBS J. 2022, 289, 2013–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murata, M.M.; Kong, X.; Moncada, E.; Chen, Y.; Imamura, H.; Wang, P.; Berns, M.W.; Yokomori, K.; Digman, M.A. NAD+ Consumption by PARP1 in Response to DNA Damage Triggers Metabolic Shift Critical for Damaged Cell Survival. Mol. Biol. Cell 2019, 30, 2584–2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felici, R.; Cavone, L.; Lapucci, A.; Guasti, D.; Bani, D.; Chiarugi, A. PARP Inhibition Delays Progression of Mitochondrial Encephalopathy in Mice. Neurother. J. Am. Soc. Exp. Neurother. 2014, 11, 651–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schriewer, J.M.; Peek, C.B.; Bass, J.; Schumacker, P.T. ROS-Mediated PARP Activity Undermines Mitochondrial Function after Permeability Transition Pore Opening during Myocardial Ischemia-Reperfusion. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2013, 2, e000159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, R.; Sammler, E.; Gonzalez-Hunt, C.P.; Barraza, I.; Pena, N.; Rouanet, J.P.; Naaldijk, Y.; Goodson, S.; Fuzzati, M.; Blandini, F.; et al. A Blood-Based Marker of Mitochondrial DNA Damage in Parkinson’s Disease. Sci. Transl. Med. 2023, 15, eabo1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).