Submitted:

19 December 2025

Posted:

22 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Specimen Selection

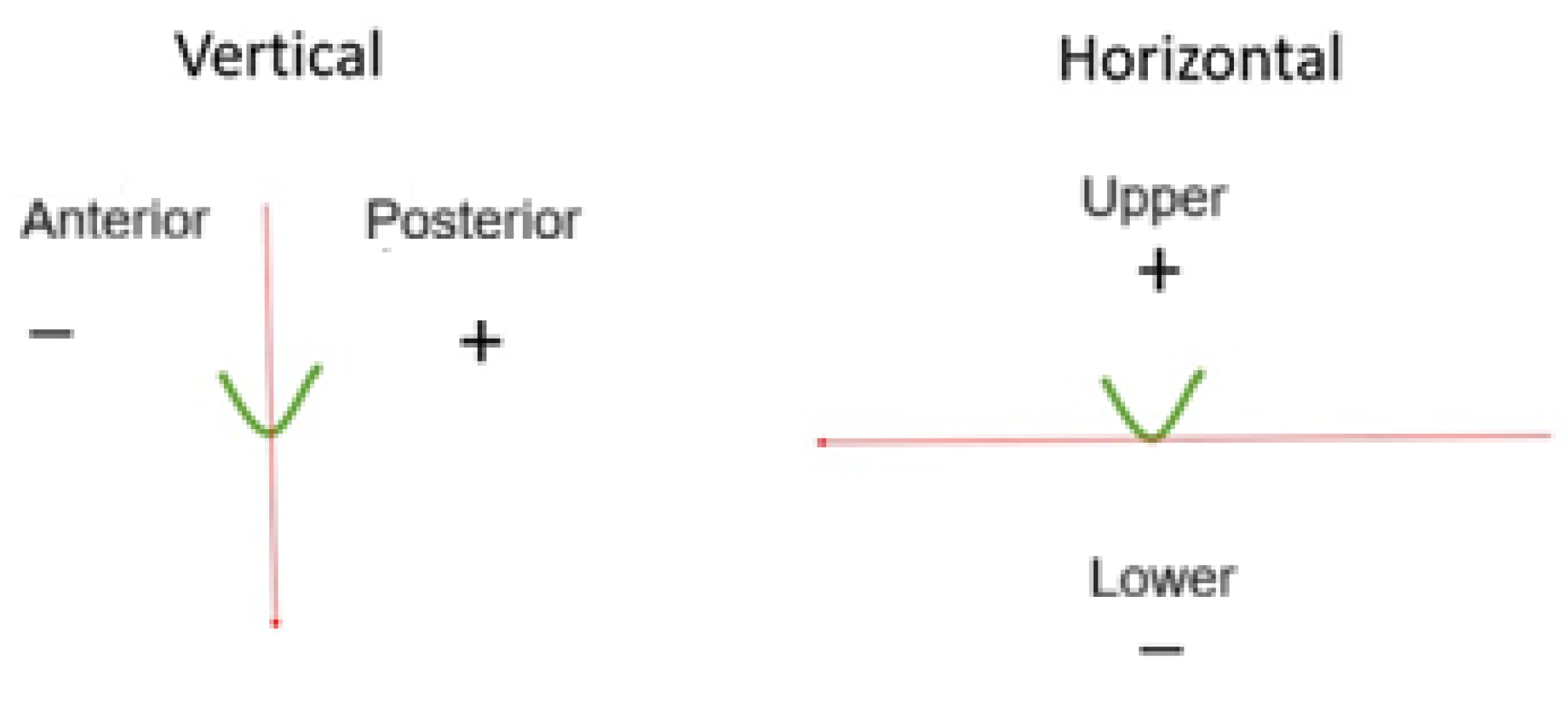

2.2. Measurements

2.3. Statistics

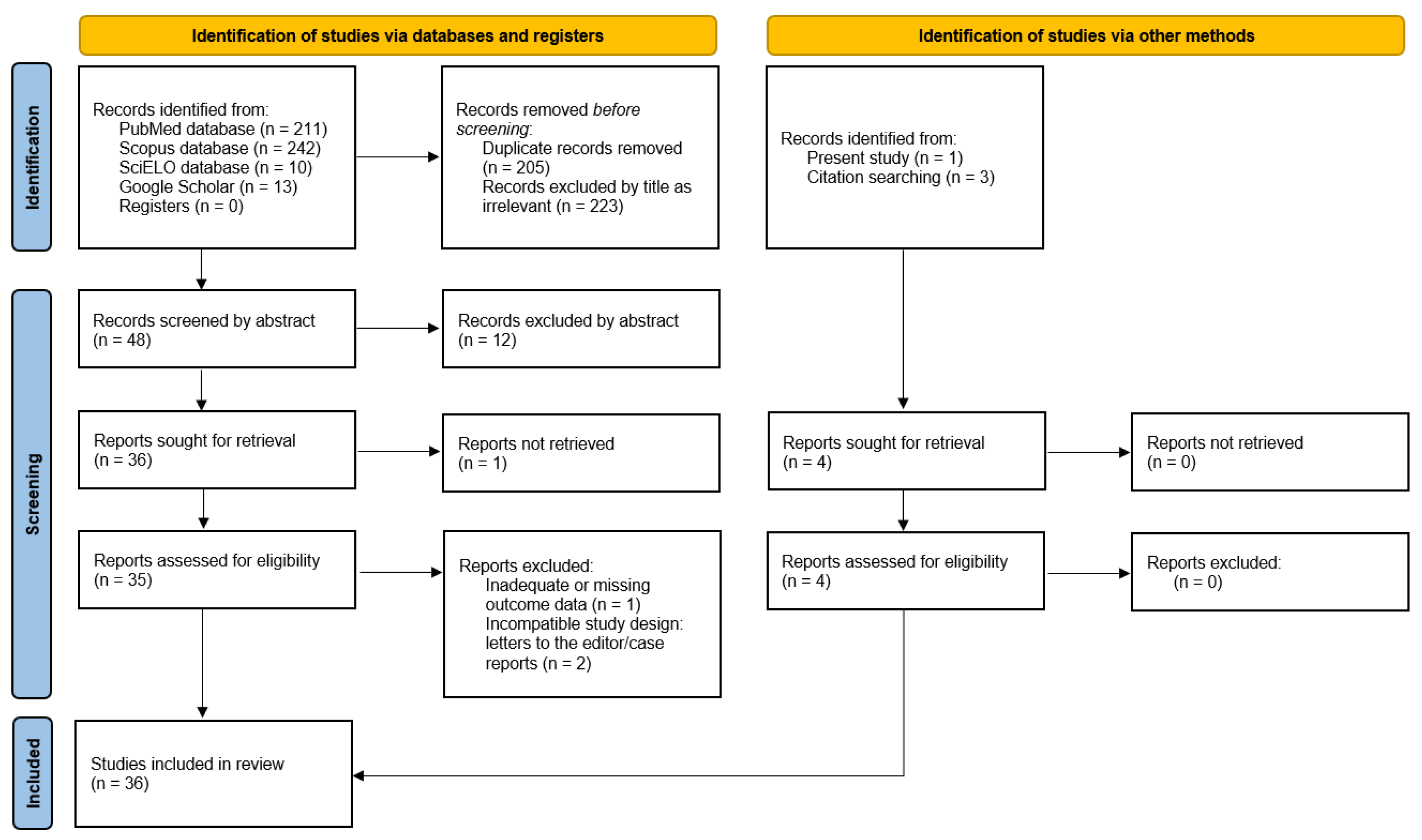

2.4. Meta-Analysis

3. Results

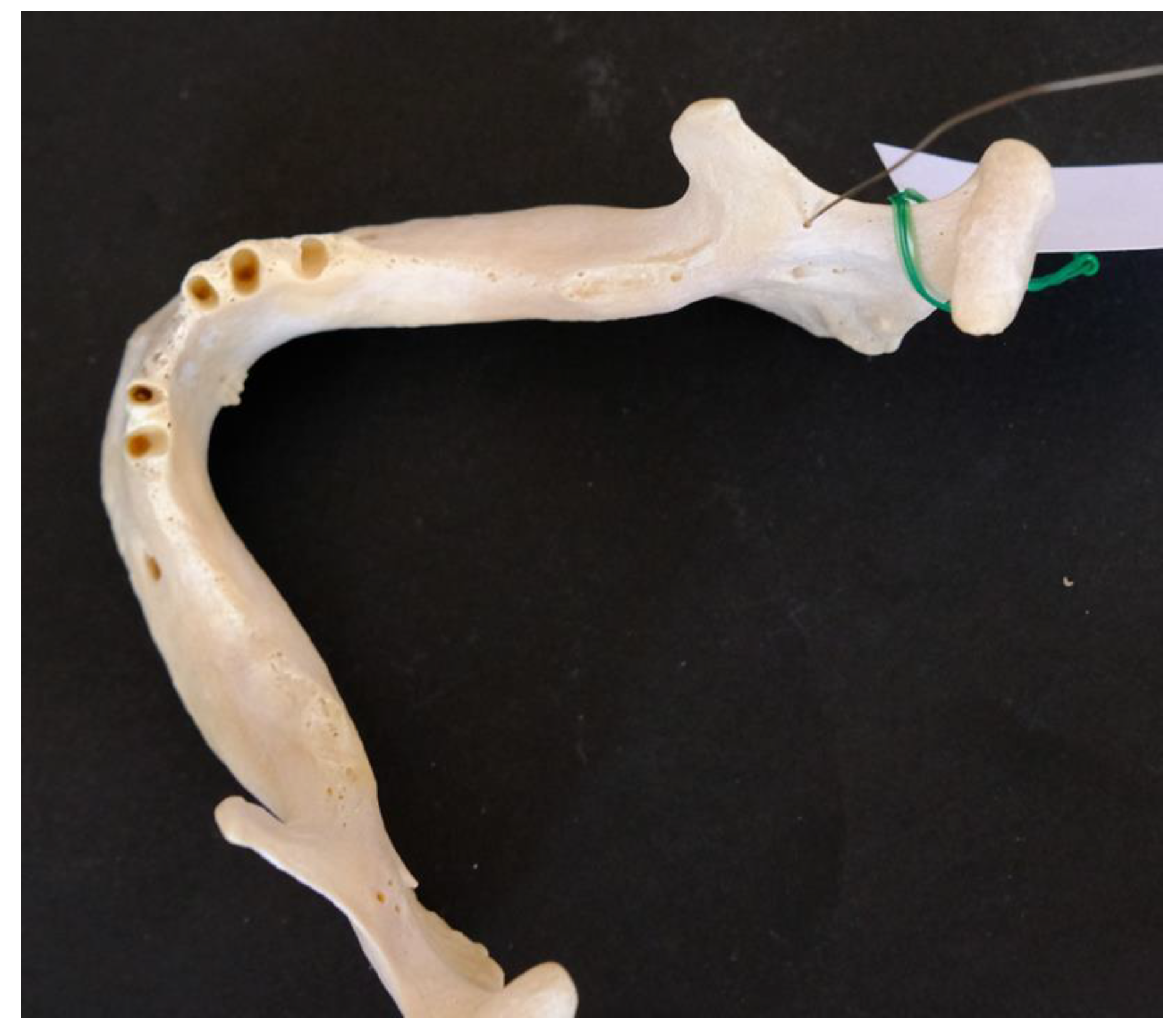

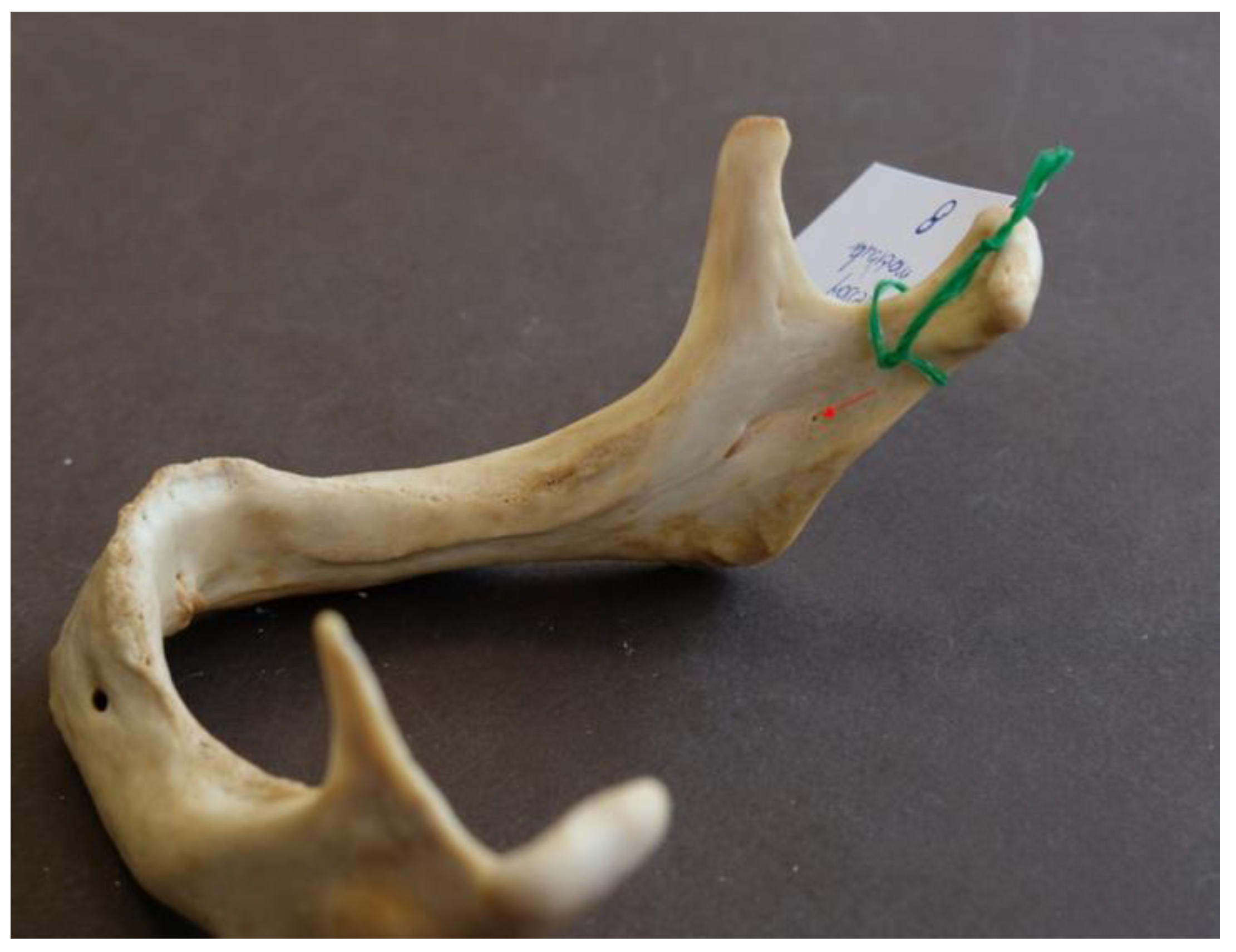

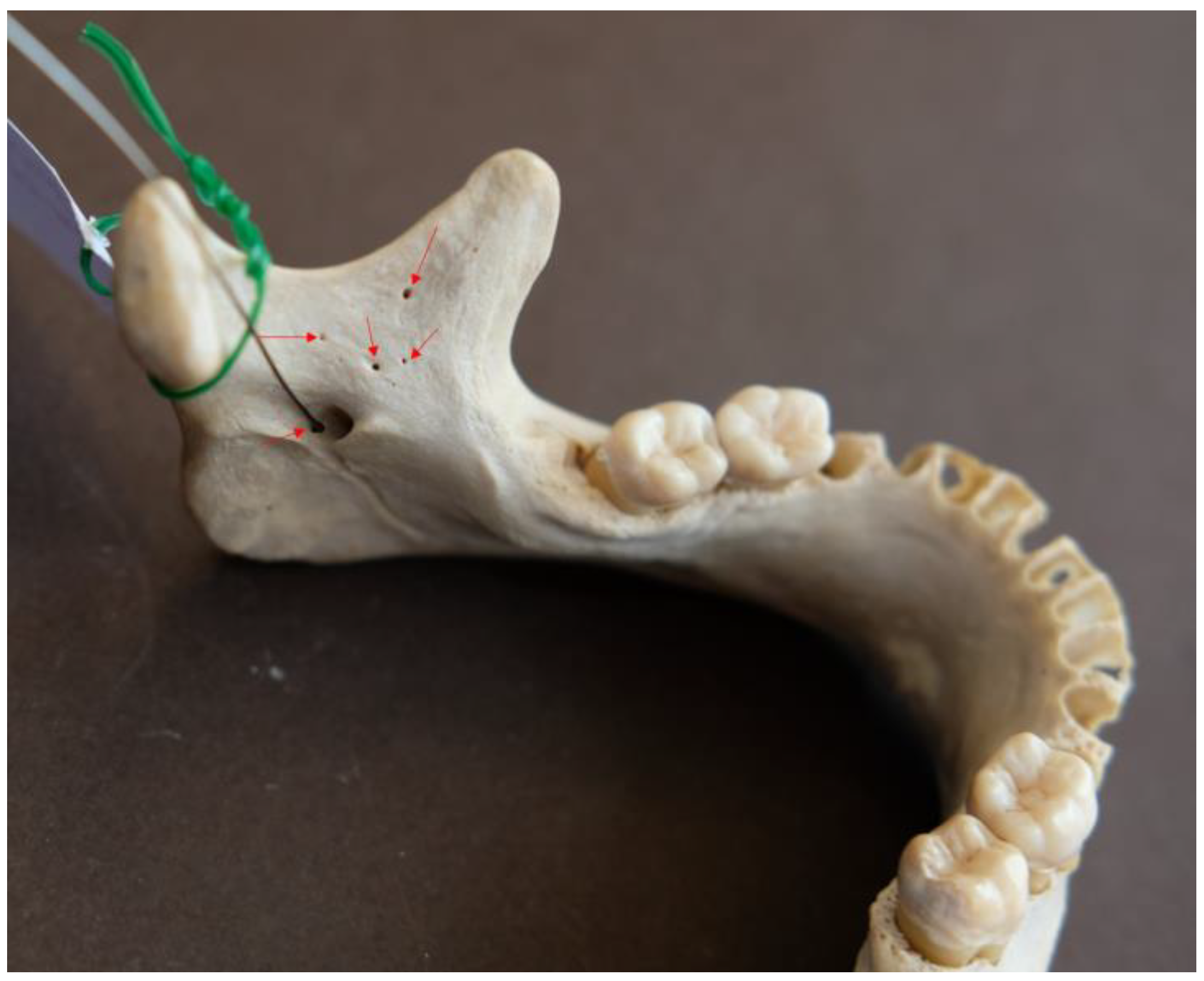

3.1. Prevalence, Size and Location of Accessory Mandibular Foramina

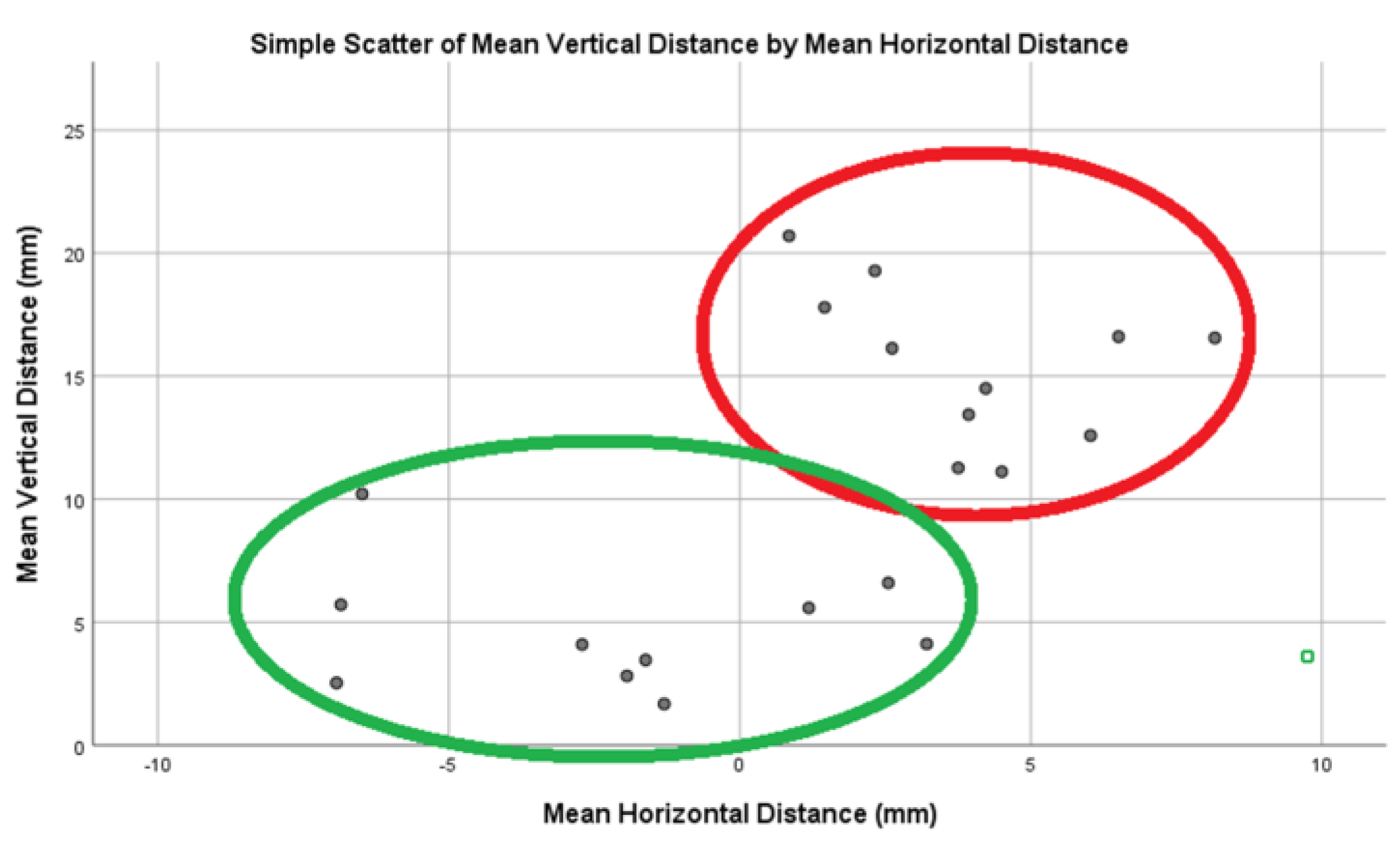

3.2. Clustering Accessory Mandibular Foramina Reveals Two Distinct Groups

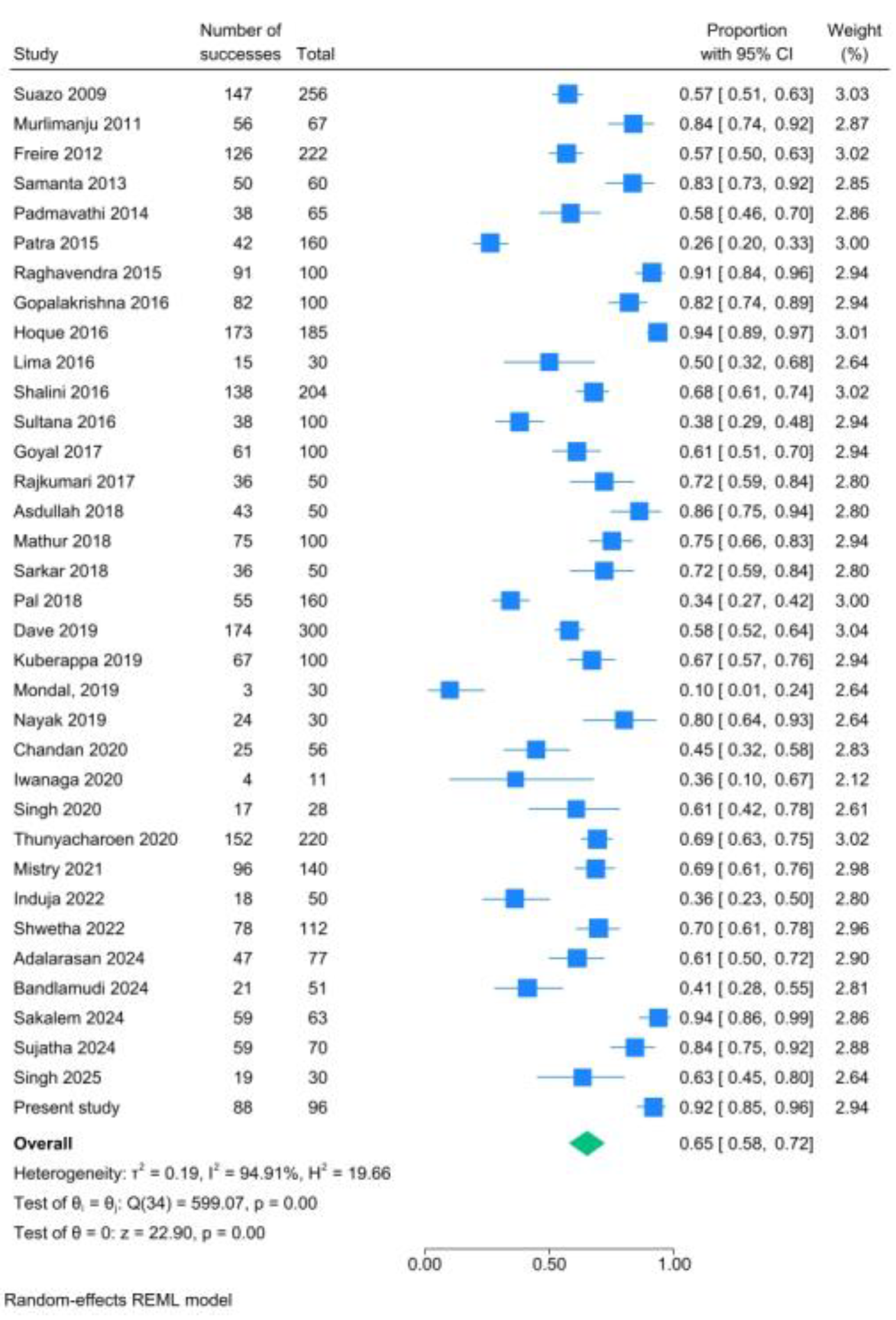

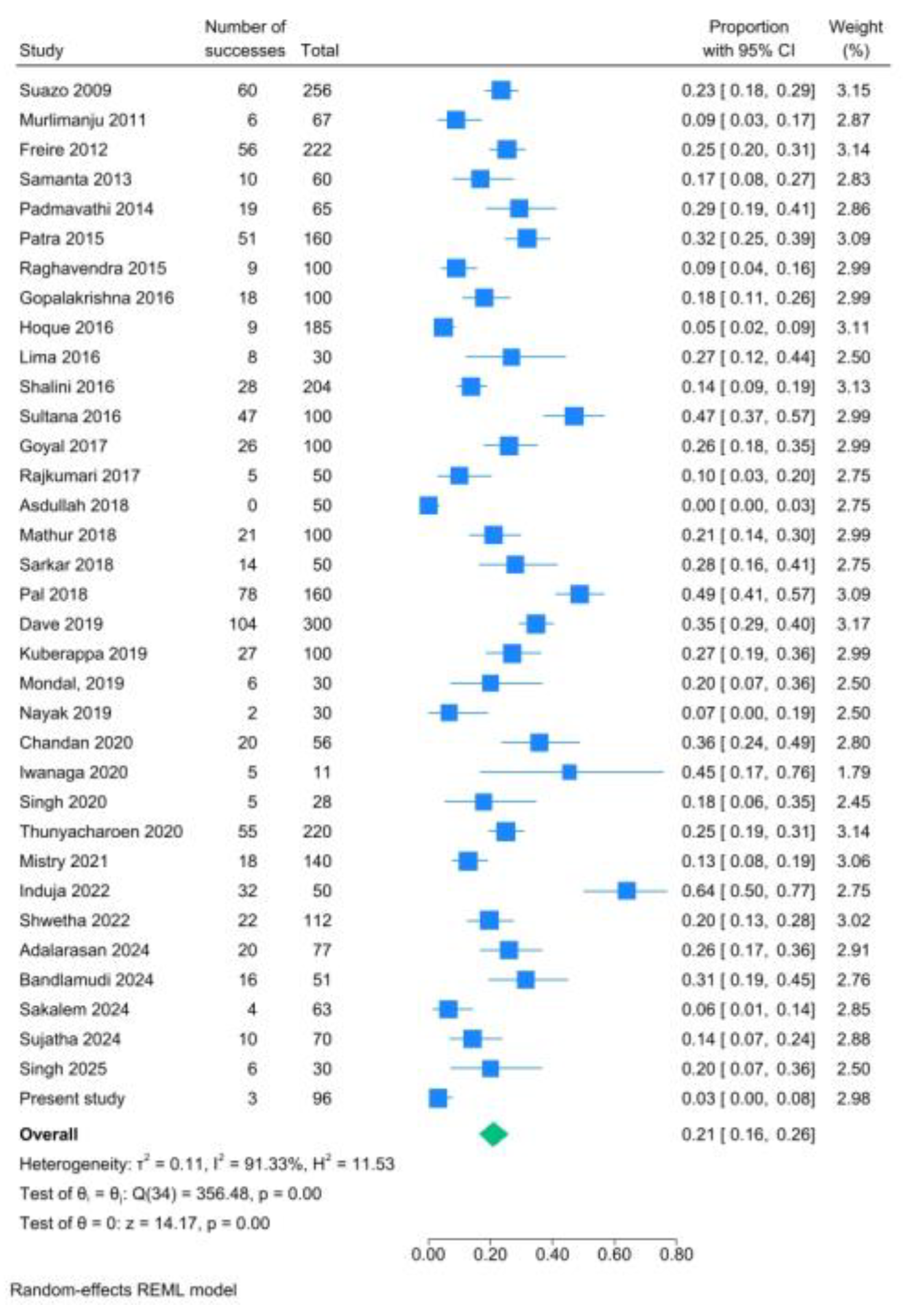

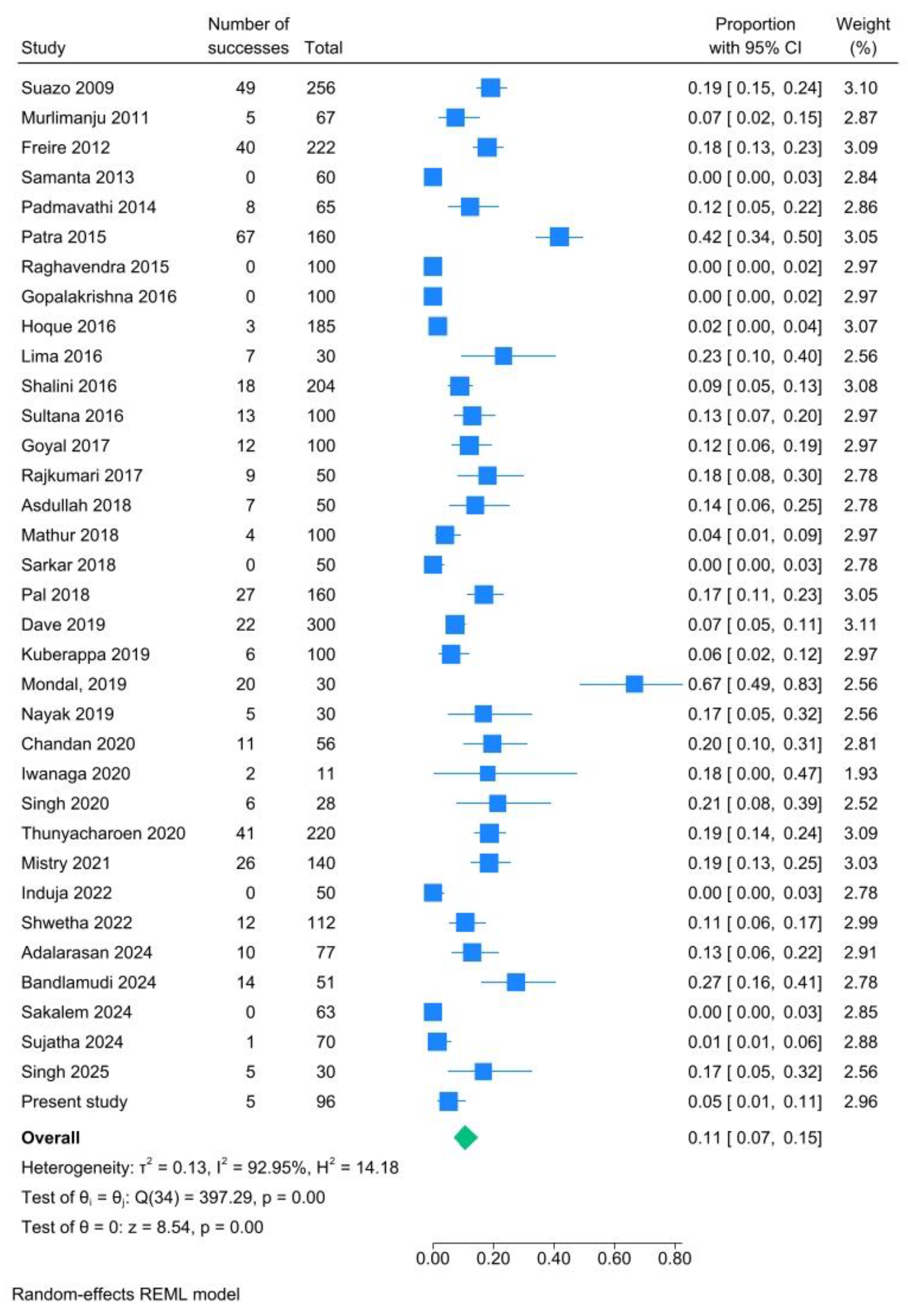

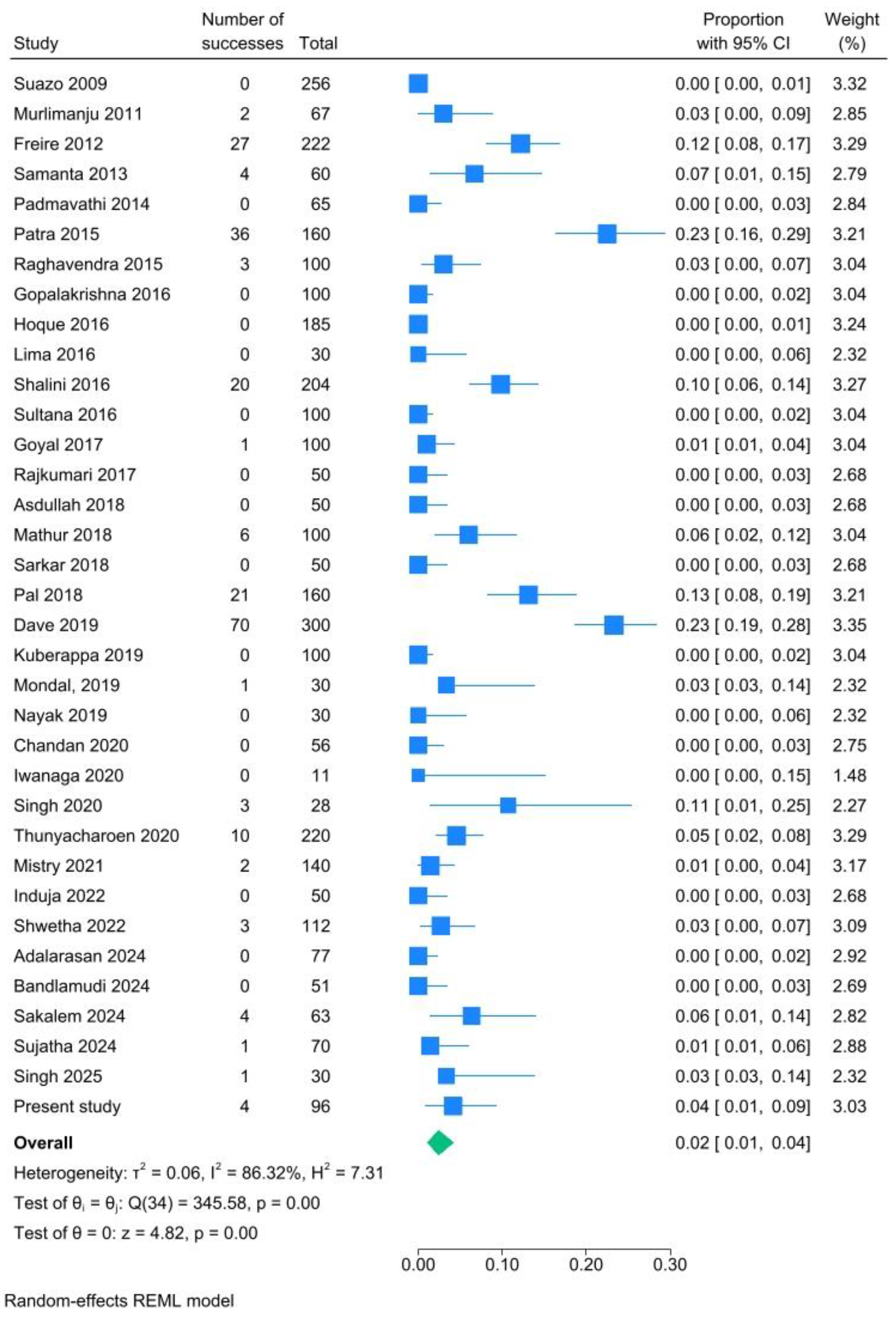

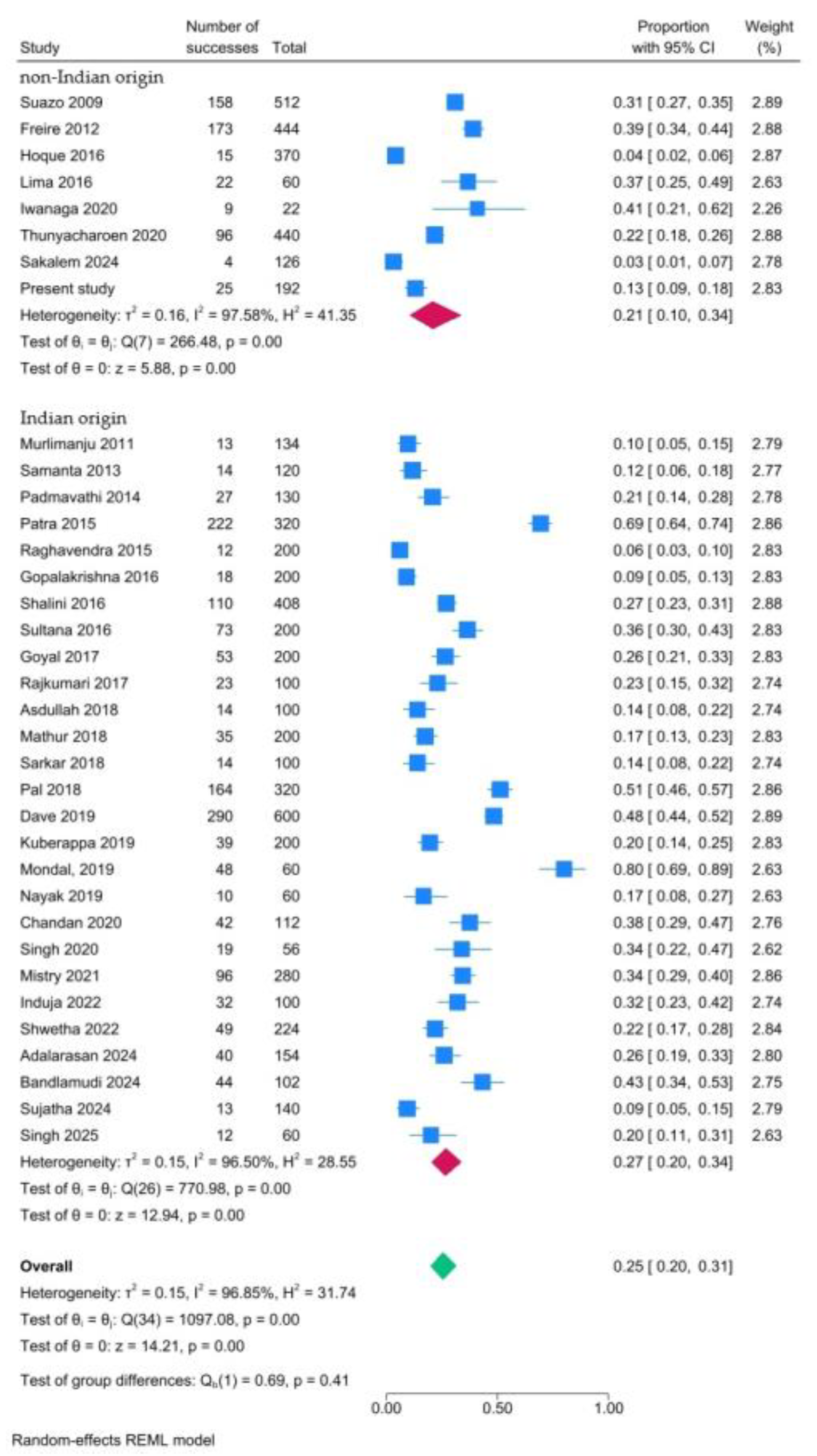

3.3. Meta-Analysis of Prevalence of Accessory Mandibular Foramina

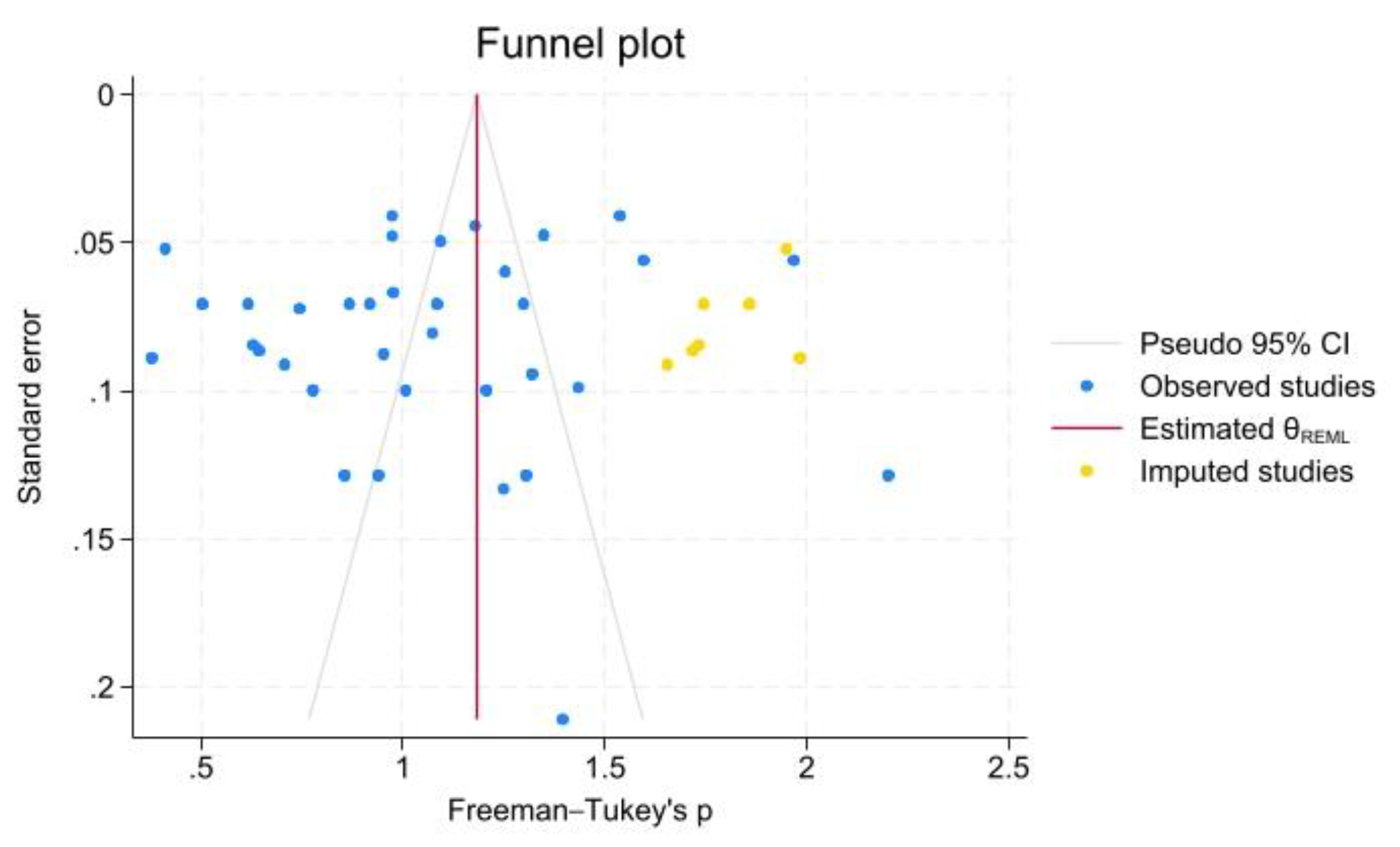

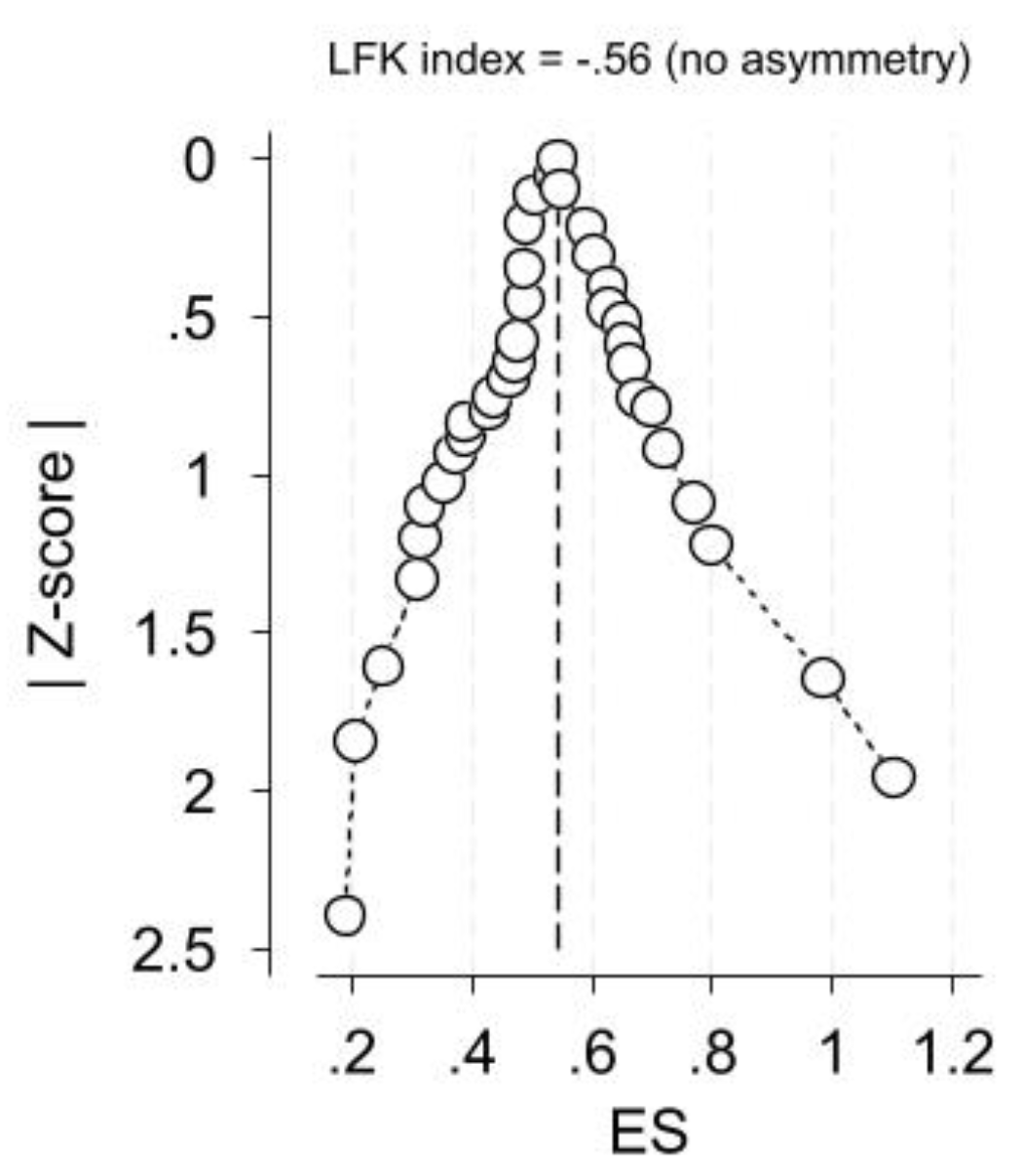

3.4. Critical Appraisal of the Present Meta-Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Additive Value of the Present Study in Relation to the Established Knowledge

4.2. Strengths and Limitations of the Present Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gray’s Anatomy, 38th ed.; Gray, H., Williams, P.L., Bannister, L.H., Berry, M.M., Collins, P., Dyson, M., Dussek, J.E., Ferguson, M.W.J., Eds.; Churchill Livingstone: London, UK, 1995; pp. 576–577. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, K.T.; Brokaw, E.J.; Bell, A.; Joy, A. Variant Inferior Alveolar Nerves and Implications for Local Anesthesia. Anesth Prog. 2016, 63, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Suri, R.K. An anatomico-radiological study of an accessory mandibular foramen on the medial mandibular surface. Folia Morphol (Warsz) 2004, 63, 511–3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Haveman, C.W.; Tabo, H.G. Posterior accessory foramina of the human mandible. J Prosthet Dent. 1974, 35, 462–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Przystańska, A.; Bruska, M. Accessory mandibular foramina: histological and immunohistochemical studies of their contents. Arch Oral Biol. 2010, 55, 77–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwanaga, J.; Kikuta, S.; Ibaragi, S.; Watanabe, K.; Kusukawa, J.; Tubbs, R.S. Clinical anatomy of the accessory mandibular foramen: application to mandibular ramus osteotomy. Surg Radiol Anat. 2020, 42, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olivetto, M.; Bettoni, J.; Duisit, J.; Chenin, L.; Bouaoud, J.; Dakpé, S.; Devauchelle, B.; Lengelé, B. Endosteal blood supply of the mandible: anatomical study of nutrient vessels in the condylar neck accessory foramina. Surg Radiol Anat. 2020, 42, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruneder, S.; Schwaiger, M.; Kerner, A.; Steyer, G.; Toferer, A.; Zemann, W.; Hammer, N.; Brcic, L.; Avian, A.; Wallner, J. Expect the unexpected: The course of the inferior alveolar artery - Preliminary results and clinical implications. Ann Anat. 2022, 240, 151867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Soni, A.; Singh, P. Morphological study of accessory foramina in mandible and its clinical implications. Indian Journal of Oral Sciences. 2017, 4, 12–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanibunda, K.; Matthews, J.N. The relationship between accessory foramina and tumour spread on the medial mandibular surface. J Anat. 2000, 196, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naitoh, M; Hiraiwa, Y; Aimiya, H; Ariji, E. Observation of bifid mandibular canal using cone-beam computerized tomography. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 2009, 24, 155–9. [Google Scholar]

- Orhan, K.; Aksoy, S.; Bilecenoglu, B.; Sakul, B.U.; Paksoy, C.S. Evaluation of bifid mandibular canals with cone-beam computed tomography in a Turkish adult population: a retrospective study. Surg Radiol Anat. 2011, 33, 501–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomaidi, Z.M.; Tsatsarelis, C.; Papadopoulos, V. Accessory Mental Foramina in Dry Mandibles: An Observational Study Along with Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Dent. J. 2025, 13, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, L.N.; Do, T.T.; Truong, L.T.; Dang The, A.T.; Truong, M.H.; Huynh Ngoc, D.K.; Nguyen, L.M. Cone Beam CT Assessment of Mandibular Foramen and Mental Foramen Positions as Essential Anatomical Landmarks: A Retrospective Study in Vietnam. Cureus 2024, 16, e59337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; Chou, R.; Glanville, J.; Grimshaw, J.M.; Hróbjartsson, A.; Lalu, M.M.; Li, T.; Loder, E.W.; Mayo-Wilson, E.; McDonald, S.; McGuinness, L.A.; Stewart, L.A.; Thomas, J.; Tricco, A.C.; Welch, V.A.; Whiting, P.; Moher, D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henry, B.M.; Tomaszewski, K.A.; Ramakrishnan, P.K.; Roy, J.; Vikse, J.; Loukas, M.; Tubbs, R.S.; Walocha, J.A. Development of the anatomical quality assessment (AQUA) tool for the quality assessment of anatomical studies included in meta-analyses and systematic reviews. Clin Anat. 2017, 30, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malkidou, N.; Papadopoulos, V.; Fiska, A. Anatomical variations of the infrahyoid muscles and ansa cervicalis: a systematic review and an updated classification system for the omohyoid muscle. Anat Cell Biol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Antoni, A.V.; Tubbs, R.S.; Patti, A.C.; Higgins, Q.M.; Tiburzi, H.; Battaglia, F. The Critical Appraisal Tool for Anatomical Meta-analysis: A framework for critically appraising anatomical meta-analyses. Clin Anat. 2022, 35, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borenstein, M. Research Note: In a meta-analysis, the I2 index does not tell us how much the effect size varies across studies. J Physiother. 2020, 66, 135–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, V.; Filippou, D.; Fiska, A. Prevalence of rare anatomic variants - publication bias due to selective reporting in meta-analyses studies. Folia Med (Plovdiv) 2024, 66, 795–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, R.N. The practical significance of mandibular accessory foramina. Aust Dent J. 1974, 19, 167–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suazo, G.I.; Zavando, M.D.A.; Smith, R.L. Is the conduct of Serres an anatomical variation? Int J Morphol. 2009, 27, 43–37. [Google Scholar]

- Murlimanju, B.V.; Prabhu, L.V.; Prameela, M.D.; Ashraf, C.M.; Krishnamurthy, A.; Kumar, C.G. Accessory Mandibular Foramina: Prevalence, embryological basis and surgical implications. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research 2011, 5, 1137–1139. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, A.R.; Rossi, A.C.; Prado, F.B.; Caria, P.H.F.; Botacin, P.R. Incidence of the mandibular accessory foramina in Brazilian population. J Morphol Sci. 2012, 29, 171–173. [Google Scholar]

- Samanta, P.P.; Kharb, P. Morphometric analysis of mandibular foramen and incidence of accessory mandibular foramina in adult human mandibles of an Indian population. Rev Arg de Anat Clin. 2013, 5, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmavathi, G.; Tiwari, S.; Varalakshmi, K.L.; Roopashree, R. An anatomical study of mandibular and accessory mandibular foramen in dry adult human mandibles of South Indian Origin. IOSR Journal of Dental and Medical Sciences 2014, 13, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, S.; Nayak, S.; Pradhan, S.; Bara, D.; Mohapatra, C. Incidence and localisation of accessory mandibular foramen in east Indian population-a single centre experience. Indian J Applied Res. 2015, 5, 664–66. [Google Scholar]

- Raghavendra, V.P.; Benjamin, W. Position of mandibular foramen and incidence of accessory mandibular foramen in dry mandibles. Int J Pharm Bio Sci. 2015, 6, 282–288. [Google Scholar]

- Gopalakrishna, K.; Deepalaxmi, S.; Somashekara, S.C.; Rathna, B.S. An anatomical study on the position of mandibular foramen in 100 dry mandibles. International Journal of Anatomy and Research 2016, 4, 1967–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, M.; Ara, S.; Begum, S.; Kamal, S.; Islam, S.A. Incidence of Accessory Mandibular Foramen in Dry Adult Human Mandible. Bangladesh Journal of Anatomy 2016, 14, 43–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, F.J.C.; Oliveira Neto, O.B.; Barbosa, F.T.; Dantas, L.C.; Olave, E.; Sousa-Rodriguez, F.C. Occurrence of the accessory foramina of the mandibular ramus in Brazilian adults and its relation to important mandibular landmarks. Int J Morhpol 2016, 34, 33–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalini, R.; RaviVarman, C.; Manoranjitham, R.; Veeramuthu, M. Morphometric study on mandibular foramen and incidence of accessory mandibular foramen in mandibles of south Indian population and its clinical implications in inferior alveolar nerve block. Anat Cell Biol. 2016, 49, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, Q.; Sharif, M.H.; Avadhani, R. Study of surgical landmarks of mandibular foramen for inferior alveolar nerve block: An osteological study. Indian Journal of Clinical Anatomy and Physiology 2016, 3, 37–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, N.; Sharma, M.; Miglani, R.; Garg, Al.; Gupta, P.K. Clinical significance of accessory foramina in adult human mandible. International Journal of Research in Medical Sciences. 2017, 5, 2449–2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajkumari, K.; Nongthombam, S.S.; Chongtham, R.S.; Huidrom, S.D.; Tharani, R.; Sanjenbam, S.D. A morphometric study of the mandibular foramen in dry adult human mandibles – a study in RIMS, Imphal. IOSR Journal of Dental and Medical Sciences 2017, 16, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asdullah, M.; Ansari, M.M.; Khan, M.M.; Salati, N.A.; Khawja, K.J.; Sachdev, A.S. Morphological variations of lingula and prevalence of accessory mandibular foramina in mandibles. Natl J Maxillofac Surg. 2018, 9, 129–33. [Google Scholar]

- Mathur, S.; Joshi, P. A study of incidence of accessory mandibular foramina in dry mandibles of Rajasthan State. International Journal of Research and Review 2018, 5, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar, A. A morphometric study of mandibular foramen and accessory mandibular foramina in adult human mandibles and its clinical implications. International Journal of Developmental Research 2013, 8, 23575–23578. [Google Scholar]

- Pal, A.; Mandal, T.; Ghosal, A.K. Mandibular and Accessory Mandibular Foramen – an anatomical study in dry adult human mandibles of eastern India. Indian Journal of Basic and Applied Medical Research 2018, 8, 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Dave, U.H.; Gupta, S.; Astik, R.B. Cross sectional analysis of occurrence of accessory mandibular foramina and their positional variations in dry mandibles. International Journal of Anatomy and Research 2019, 7, 6035–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuperappa, V.; Khan, T.A. Study of distribution of various accessory foramina in 100 human mandibles of South India. International Journal of Anatomy and Research 2019, 7, 6423–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, M.; Mukhopadhyay, P. A morphometric study of mandibular foramen and incidence of accessory mandibular foramen in dry adult human mandible and its clinical significance. Indian Journal of Basic and Applied Medical Research 2019, 8, 338–345. [Google Scholar]

- Nayak, G.; Sahoo, N.; Panda, S. Accessory mandibular foramina and bifid mandibular canals – an anatomical study. Eur J Anat 2019, 23, 261–266. [Google Scholar]

- Chandan, C.B.; Akhtar, M.J.; Kumar, A.; Sinha, R.R.; Kumar, N.; Kumar, A. Morphological study of accessory foramina in dry mandible and its clinical significance. International Journal of Medical Research Professionals 2020, 6, 90–93. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A.; Zaidi, S.H.H.; Gupta, R. A study of accessory mandibular foramina in north Indian mandibles. International Journal of Recent Trends in Science and Technology 2020, 10, 58–61. [Google Scholar]

- Thunyacharoen, S.; Lymkhanakhom, S.; Chantakhat, P.; Suwanin, S.; Sawanprom, S.; Iamaroon, A.; Janhom, A.; Mahakkanukrauh, P. An anatomical study on locations of the mandibular foramen and the accessory mandibular foramen in the mandible and their clinical implication in a Thai population. Anat Cell Biol. 2020, 53, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mistry, P.N.; Rajguru, J.; Dave, M.R. Study of the accessory mandibular foramina in dry adult human mandibles and their clinical and surgical implications. International Journal of Anatomy, Radiology and Surgery 2021, 10, AO16–AO19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Induja, M.P.; Chokkattu, J.J. Analysis of various accessory foramina in mandible. International Journal of Health Sciences 2022, 6, 11944–11949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shwetha, K.; Ravishankar, M.V.; Vidya, C.S.; Pushpalatha, K.; Dakshayani, K.R. A study of the morphology of retromolar, mandibular, and accessory mandibular foramen in dry mandibles belonging to the Southern part of Karnataka state and their clinical significance. Journal of Krishna Institute of Medical Sciences University 2022, 11, 36–45. [Google Scholar]

- Adalarasan, S.; Devi, L.; Ps, S. Morphometric Study on the Mandibular Foramen. Cureus 2024, 16, e70862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandlamudi, S.; Pavithra, M.; Subramanian, M.; Mariappan, A.S.; Yoganandham, J. Location of mandibular foramen in dry mandibles in relation to various anatomical landmarks. IP International Journal of Maxillofacial Imaging 2024, 10, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakalem, M.E.; Sestario, C.S.; Motta, A.L.; Quintihano, D.; Myszynski, S.L.; Sato, V.A.H. Anatomical variations of the human mandible and prevalence of duplicate mental and mandibular foramina in the collection of the State University of Londrina. Translational Research in Anatomy 2024, 37, 100357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sujatha, A.; Charitha, G.N.; Indira, T.; Nisha Parveen, C.B.; Rani, S.T. Positional variations and morphometry of mandibular foramen in adult dry human mandibles. Int J Med Pub Health 2024, 14, 765–769. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, Y.; Shakya, P.; Saba, N.U.; Singh, H.; Kumar, N. A Morphometric Study of the Mandibular Foramen, Lingula, and the Incidence of Accessory Mandibular Foramina in Dry Mandibles. Cureus 2025, 17, e81087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tshite, K.; Olaleye, O. Location of mandibular foramen in adult black South African population: A morphometric analysis and investigation into possible radiographic correlation. South African Dental Journal. 2024, 79, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charalampakis, A.; Kourkoumelis, G.; Psari, C.; Antoniou, V.; Piagkou, M.; Demesticha, T.; Kotsiomitis, E.; Troupis, T. The position of the mental foramen in dentate and edentulous mandibles: Clinical and surgical relevance. Folia Morphol. 2017, 76, 709–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pramstraller, M.; Schincaglia, G.P.; Vecchiatini, R.; Farina, R.; Trombelli, L. Alveolar ridge dimensions in mandibular posterior regions: a retrospective comparative study of dentate and edentulous sites using computerized tomography data. Surg Radiol Anat. 2018, 40, 1419–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naitoh, M; Hiraiwa, Y; Aimiya, H; Ariji, E. Observation of bifid mandibular canal using cone-beam computerized tomography. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 2009, 24, 155–9. [Google Scholar]

- Wadu, S.G.; Penhall, B.; Townsend, G.C. Morphological variability of the human inferior alveolar nerve. Clin Anat. 1997, 10, 82–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuribayashi, A.; Watanabe, H.; Imaizumi, A.; Tantanapornkul, W.; Katakami, K.; Kurabayashi, T. Bifid mandibular canals: cone beam computed tomography evaluation. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2010, 39, 235–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumussoy, I.; Demirezer, K.; Duman, S.B.; Haylaz, E.; Bayrakdar, I.S.; Celik, O.; Syed, A.Z. AI-powered segmentation of bifid mandibular canals using CBCT. BMC Oral Health 2025, 25, 907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jindanil, T; Fontenele, RC; de-Azevedo-Vaz, SL; Lahoud, P; Neves, FS; Jacobs, R. Artificial intelligence-based incisive canal visualization for preventing and detecting post-implant injury, using cone beam computed tomography. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2025, 54, 769–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrzat, J.; Ryniewicz, W.; Goncerz, G.; Kozerska, M. Anatomical features of the mandibular foramen and their clinical significance – review of the literature. Folia Medica Cracoviensia 2023, 63, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yameen, M.; Modi, V. Morphometric variation of mandibular foramina with related accessory foramina in dry adult human mandibles and its possible clinical significance. International Journal of Research Publication and Reviews 2024, 5, 3094–3101. [Google Scholar]

- Varvara, G.; Feragalli, B.; Turkyilmaz, I.; D’Alonzo, A.; Rinaldi, F.; Bianchi, S.; Piattelli, M.; Macchiarelli, G.; Bernardi, S. Prevalence and Characteristics of Accessory Mandibular Canals: A Cone-Beam Computed Tomography Study in a European Adult Population. Diagnostics (Basel). 2022, 12, 1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okiriamu, A.; Butt, F.; Opondo, F.; Onyango, F. Morphology and Variant Anatomy of the Mandibular Canal in a Kenyan Population: A Cone-Beam Computed Tomography Study. Craniomaxillofacial Research & Innovation 2023, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajchel, J.; Ellis, E., 3rd; Fonseca, R.J. The anatomical location of the mandibular canal: its relationship to the sagittal ramus osteotomy. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg. 1986, 1, 37–47. [Google Scholar]

- Patil, S.; Matsuda, Y.; Okano, T. Accessory mandibular foramina: a CT study of 300 cases. Surg Radiol Anat. 2013, 35, 323–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Origin | Material | Sample (No of mandibles) | Mandibles without AMaF | Mandibles with unilateral AMaF | Mandibles with bilateral AMaF | Mandibles with multiple AMaFs | Total number of AMaFs |

| Sutton 1974 [21] | Australia | DM | 300 | 131 | ||||

| Suazo 2009 [22] | Brazil | DM | 256 | 147 | 60 | 49 | 0 | 158 |

| Murlimanju 2011 [23] | India | DM | 67 | 56 | 6 | 5 | 2 | 13 |

| Freire 2012 [24] | Brazil | DM | 222 | 126 | 56 | 40 | 27 | 173 |

| Samanta 2013 [25] | India | DM | 60 | 50 | 10 | 0 | 4 | 14 |

| Padmavathi 2014 [26] | India | DM | 65 | 38 | 19 | 8 | 0 | 27 222 12 18 |

| Patra 2015 [27] | India | DM | 160 | 42 | 51 | 67 | 36 | |

| Raghavendra 2015 [28] | India | DM | 100 | 91 | 9 | 0 | 3 | |

| Gopalakrishna 2016 [29] | India | DM | 100 | 82 | 18 | 0 | 0 | |

| Hoque 2016 [30] | Bangladesh | DM | 185 | 173 | 9 | 3 | 0 | 15 |

| Lima 2016 [31] | Brazil | DM | 30 | 15 | 8 | 7 | 0 | 22 |

| Shalini 2016 [32] | India | DM | 204 | 138 | 28 | 18 | 20 | 110 |

| Sultana 2016 [33] | India | DM | 100 | 38 | 47 | 13 | 0 | 73 |

| Goyal 2017 [34] | India | DM | 100 | 61 | 26 | 12 | 1 | 53 |

| Rajkumari 2017 [35] | India | DM | 50 | 36 | 5 | 9 | 0 | 23 |

| Asdullah 2018 [36] | India | DM | 50 | 43 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 14 |

| Mathur 2018 [37] | India | DM | 100 | 75 | 21 | 4 | 6 | 35 |

| Sarkar 2018 [38] | India | DM | 50 | 36 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 14 |

| Pal 2018 [39] | India | DM | 160 | 55 | 78 | 27 | 21 | 164 |

| Dave 2019 [40] | India | DM | 300 | 174 | 104 | 22 | 70 | 290 |

| Kuberappa 2019 [41] | India | DM | 100 | 67 | 27 | 6 | 0 | 39 |

| Mondal, 2019 [42] | India | DM | 30 | 3 | 6 | 20 | 1 | 48 |

| Nayak 2019 [43] | India | DM | 30 | 24 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 10 |

| Chandan 2020 [44] | India | DM | 56 | 25 | 20 | 11 | 0 | 42 |

| Iwanaga 2020 [6] | Japan | FFC | 11 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 9 |

| Singh 2020 [45] | India | DM | 28 | 17 | 5 | 6 | 3 | 19 |

| Thunyacharoen 2020 [46] | Thailand | DM | 220 | 152 | 55 | 41 | 10 | 96 |

| Mistry 2021 [47] | India | DM | 140 | 96 | 18 | 26 | 2 | 96 |

| Induja 2022 [48] | India | DM | 50 | 18 | 32 | 0 | 0 | 32 |

| Shwetha 2022 [49] | India | DM | 112 | 78 | 22 | 12 | 3 | 49 |

| Adalarasan 2024 [50] | India | DM | 77 | 124 | 20 | 10 | 0 | 40 |

| Bandlamudi 2024 [51] | India | DM | 51 | 21 | 16 | 14 | 0 | 44 |

| Sakalem 2024 [52] | Brazil | DM | 63 | 59 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 4 |

| Sujatha 2024 [53] | India | DM | 70 | 59 | 10 | 1 | 1 | 13 |

| Singh 2025 [54] | India | DM | 30 | 19 | 6 | 5 | 1 | 12 |

| Present study | Greece | DM | 96 | 88 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 25 |

| Study | Domain 1: Objectives and study characteristics | Domain 2: Study design | Domain 3: Methodology characterization | Domain 4: Descriptive anatomy | Domain 5: Reporting of results | Quality assessment |

| Sutton 1974 [21] | Unclear | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | Medium |

| Suazo 2009 [22] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | High |

| Murlimanju 2011 [23] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | High |

| Freire 2012 [24] | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Low | High |

| Samanta 2013 [25] | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Medium |

| Padmavathi 2014 [26] | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Low | High |

| Patra 2015 [27] | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Medium |

| Raghavendra 2015 [28] | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Medium |

| Gopalakrishna 2016 [29] | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Medium |

| Hoque 2016 [30] | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Medium |

| Lima 2016 [31] | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Low | High |

| Shalini 2016 [32] | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Low | High |

| Sultana 2016 [33] | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Low | High |

| Goyal 2017 [34] | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Medium |

| Rajkumari 2017 [35] | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Low | High |

| Asdullah 2018 [36] | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Medium |

| Mathur 2018 [37] | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Medium |

| Sarkar 2018 [38] | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Low | High |

| Pal 2018 [39] | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Medium |

| Dave 2019 [40] | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Medium |

| Kuberappa 2019 [41] | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Medium |

| Mondal, 2019 [42] | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Medium |

| Nayak 2019 [43] | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | High |

| Chandan 2020 [44] | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Medium |

| Iwanaga 2020 [6] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | High |

| Singh 2020 [45] | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Medium |

| Thunyacharoen 2020 [46] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | High |

| Mistry 2021 [47] | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Medium |

| Induja 2022 [48] | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Medium |

| Shwetha 2022 [49] | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Low | High |

| Adalarasan 2024 [50] | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Low | High |

| Bandlamudi 2024 [51] | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Low | High |

| Sakalem 2024 [52] | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Low | High |

| Sujatha 2024 [53] | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Low | High |

| Singh 2025 [54] | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Low | High |

| Present study | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Low | High |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).