1. Introduction

The canalis sinuosus, first described by Jones in 1939, is a frequently tortuous anatomical structure that has been demonstrated in 88% to 100% of patients [

1,

2]. This structure is increasingly recognized as a relevant anatomical unit and is no longer considered merely a variant.

As a rule, the sinuosal canal emerges about 25 mm behind the infraorbital foramen on both sides, runs along the lateral nasal wall to the orbital floor and continues to the anterior nasal opening, often ending with small accessory canals to the palatine terminal [

3,

4]. These foramina often occur palatal to the maxillary incisors and canines and are found in 15.7% to 100% of patients [

2,

3,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. A terminal branch of the superior anterior alveolar nerve from the infraorbital nerve runs together with the artery of the same name in this canal.

The arterial structure of the canalis sinuosus is a small branch of the infraorbital artery, which, like the nasopalatine artery, originates from the important maxillary artery in the maxilla [

3,

4]. These arteries supply the maxillary anterior teeth and surrounding soft tissue, with anastomoses also playing a role [

10].

In contrast to the canalis sinuosus, the canalis incisivus and the ductus nasopalatinus are separate structures that develop from the bones of the primary palate [

10]. The nasopalatine duct forms prenatally from epithelial remnants in the incisive canal and provides a connection between the oral and nasal cavities from the 13th embryonic week onwards before it remains as an obliterated epithelial remnant in the [

11]. The incisive canal ends caudally in the incisive foramen and contains nerves as well as vessels, in particular the nasopalatine artery, which forms an anastomosis with the greater palatine artery. The nasopalatine nerve, which innervates the mucous membrane of the hard palate, runs through the incisive foramen and is often referred to clinically as the incisive nerve.

As with any surgical procedure, injury to neighboring structures such as blood vessels, nerves and tissues can lead to relevant complications and postoperative restrictions. Hemorrhagic events as well as hyp- and anesthesia in the implantation area occur frequently, especially in implantations in the premaxilla [

12]. However, thanks to progressive developments in three-dimensional imaging, computer-assisted planning and template-supported implantations, these complications have become significantly less frequent.

Nevertheless, implantations in the maxilla remain more risky than in the mandible. Gaeta-Araujo et al. found that the prevalence of perforations of adjacent structures, such as the maxillary sinus or the incisive canal, is 43.5% in the maxilla, while only 11.3% of cases are affected in the mandible [

13]. The limited space available in the maxilla is a significant factor here [

14]. Despite technical advances, complications continue to occur, often affecting the sensory system in the surgical area. Damage to the nasopalatine nerve was long thought to be the cause of hypoesthesia and anesthesia, but more recent studies have refuted this assumption [

6,

7].

Implant placement should always be planned with the final prosthetic restoration in mind, taking into account both functional and esthetic aspects [

15]. For this reason, the use of imaging techniques such as digital volume tomography (CBCT) is essential today to achieve a predictable outcome [

16]. Orhan et al, Ghandourah et al and Tomrukcu et al show that two-dimensional orthopantomography (OPG) is not sufficient to assess small anatomical structures such as accessory canals of the sinuosal canal [5, 7, 9]. These can easily be mistaken for periapical lesions, which is exacerbated by radiologic artifacts such as superimposition and image distortion. Therefore, a three-dimensional image should also be obtained during postoperative diagnostics [

5,

17]. With modern CBCT technologies and powerful software applications, precise visualization of the anatomical conditions and exact surgical planning are now possible.

The aim of this study was to examine the extent to which the canalis sinuosus occurs in a southern German population and whether there are significant correlations with the age or gender of the patients. In addition, it was investigated whether there are differences in the number, localization, diameter and distances to neighboring anatomical structures. The results should allow conclusions to be drawn for diagnostics and preoperative planning prior to implant surgery.

2. Materials and Methods

CBCT images of 210 patients from a dental clinic in Hilzingen (Germany) between February 2009 and July 2019 were used to analyze the accessory canals of the canalis sinuosus. The DICOM datasets were anonymized and evaluated retrospectively. The study was approved by the responsible ethics committee of the Baden-Württemberg Medical Association.

The patients were divided into three age groups: under 41 years (group 1), 41 to 60 years (group 2) and over 61 years (group 3), with 35 women and 35 men per group. Inclusion criteria were complete radiographs of the maxilla and nasal floor; exclusion criteria included pathological changes, implants in the area of the canalis sinuosus and metallic dental restorations.

Radiographs were taken using the Gendex GXCB-500 CBCT scanner (Gendex Dental Systems, USA), with patients positioned according to established standards. The scan time was 23 seconds with a resolution of 0.2 mm.

The CBCT data was loaded into the i-CAT VisionTM software (version 1.9.3.13) and then transferred to Osirix MD (version 11.0) for analysis. The measurements were performed on a calibrated monitor in a darkened room.

The analysis began with the descriptive mapping of the diameters of the accessory foramina in the axial and sagittal planes, followed by the measurement of the distances of the foramina to neighboring teeth. These measurements helped to identify possible conflicts with future implant positions. The reference value for implant positions was 10 mm from the alveolar ridge.

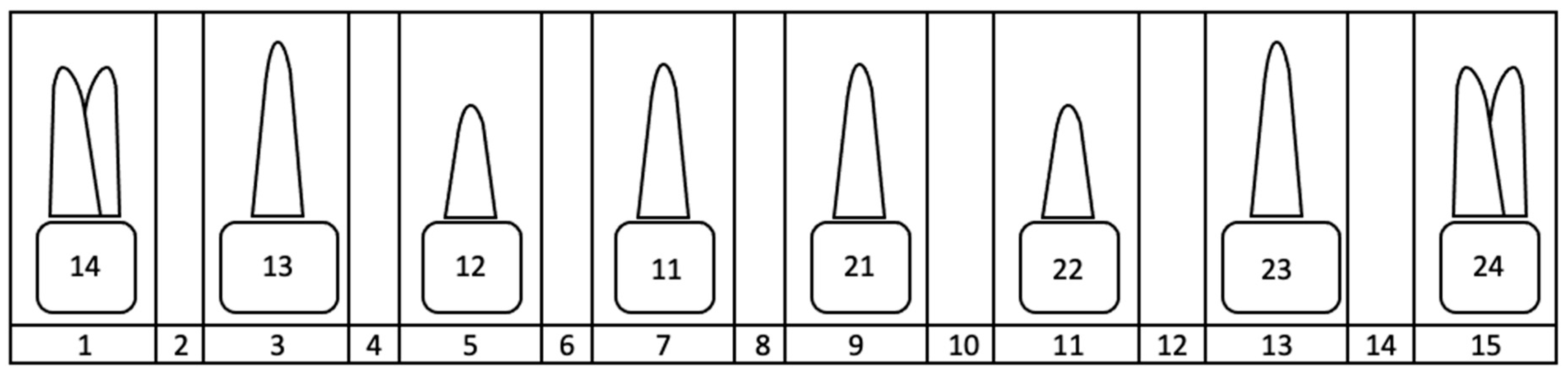

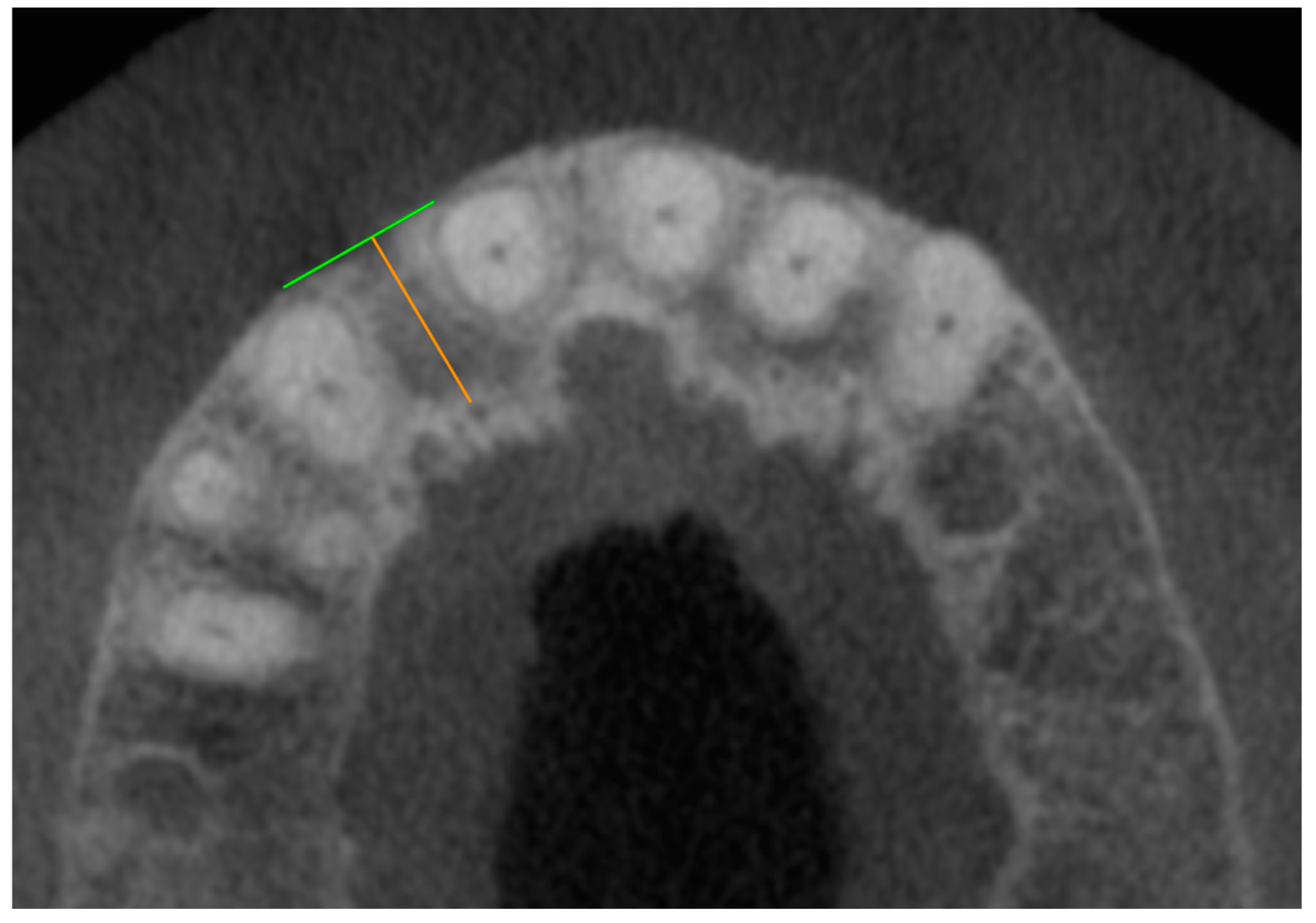

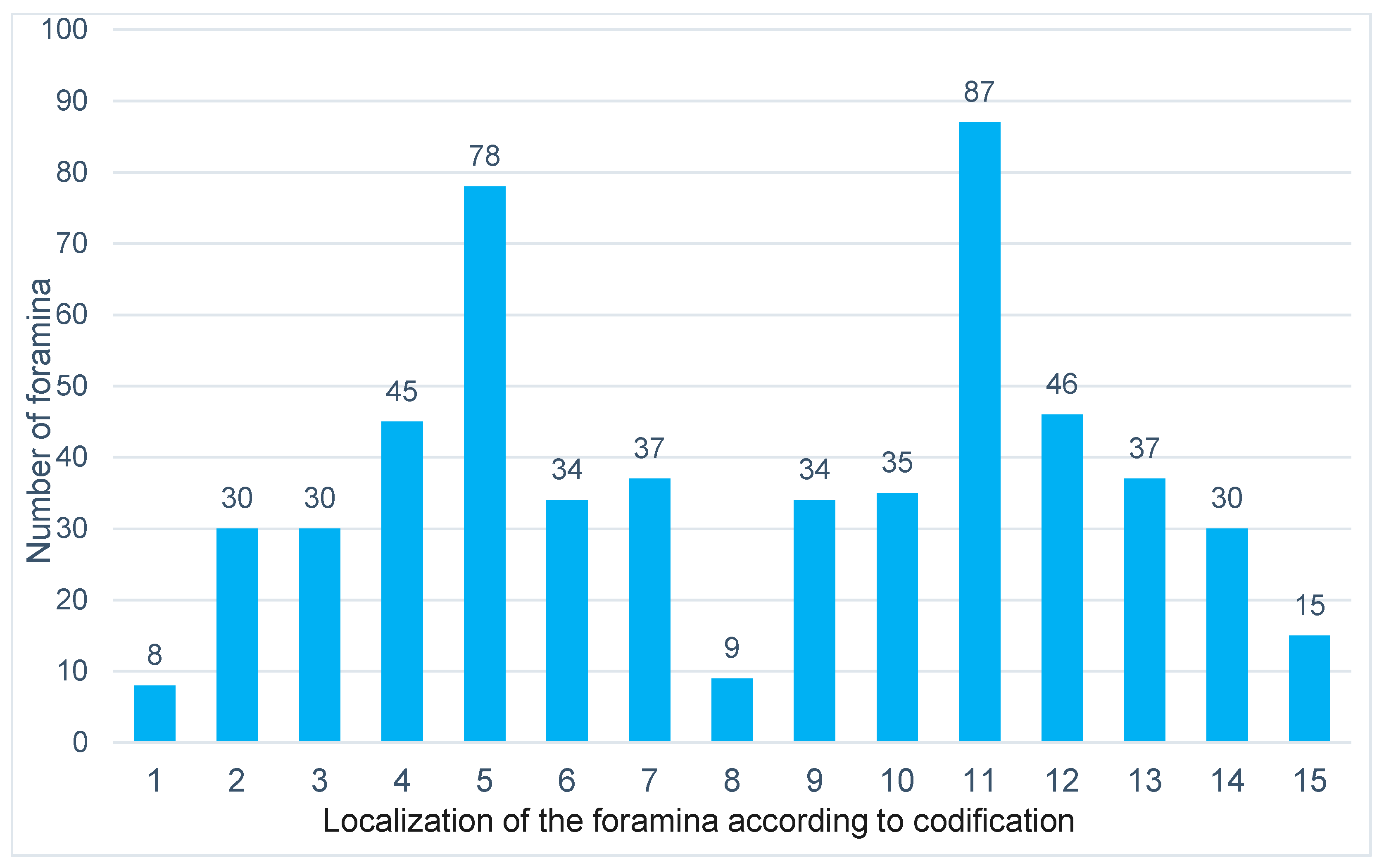

For the measurements, all foramina between the first premolars (teeth 14-24) were taken into account in the axial plane. The foramen to be measured was coded in the axial plane using an assigned number (

Figure 1).

Only clearly recognizable foramina were measured, whereby the incisive foramen was excluded. The largest diameters of the foramina were recorded in the axial and sagittal planes. In the sagittal plane, the largest caudal diameter was measured if the canal wall was clearly visible.

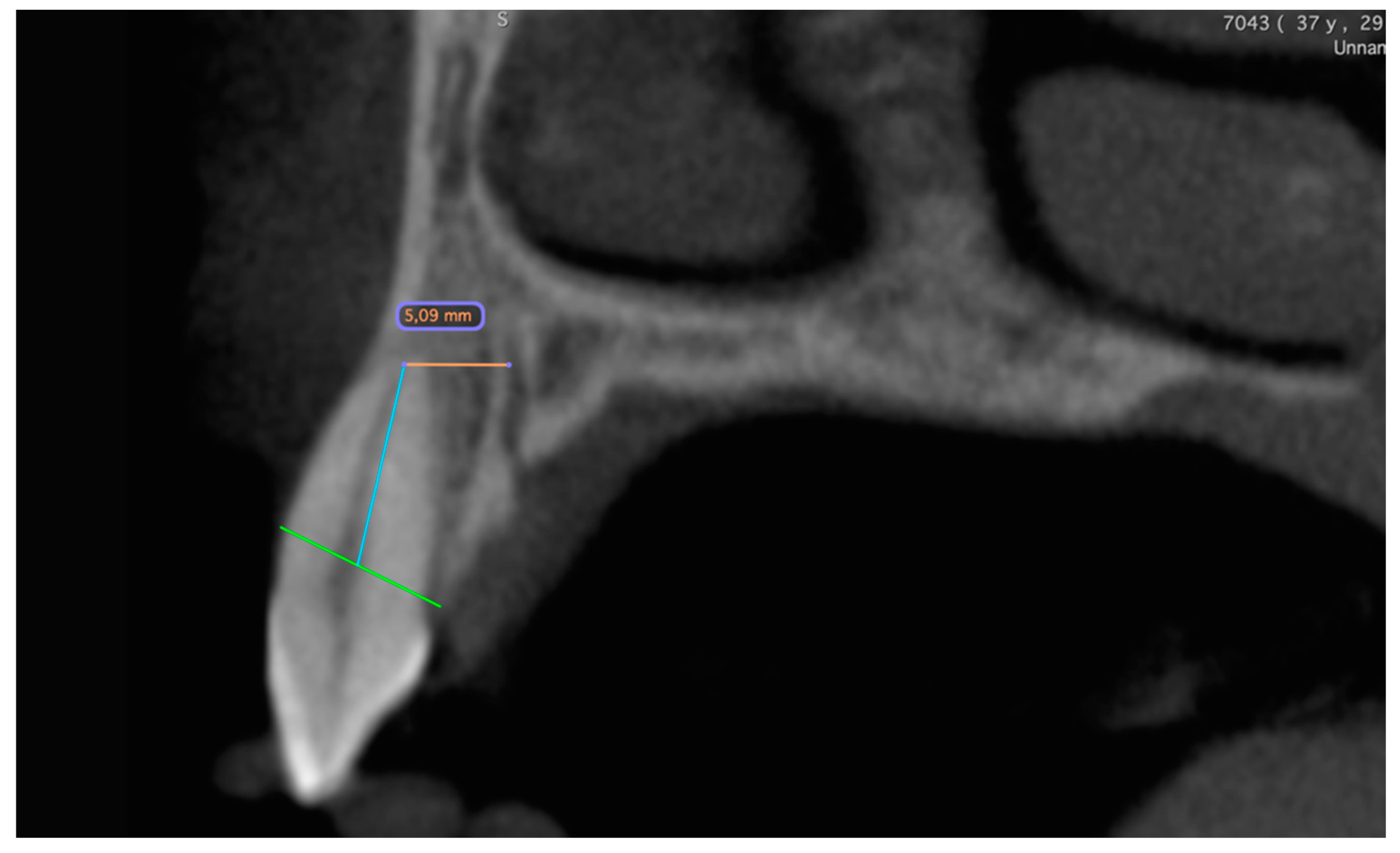

In the second step, the distances between the foramina and the neighboring teeth were measured (

Figure 2). If no tooth was nearby, the alveolar cortex was used as a reference (

Figure 3). If the tooth was not clearly visible, the value was set to 0.

The data collected for each of the 210 patients was recorded for statistical analysis in the spreadsheet program Excel 2019 for Mac version 16.70 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, USA). For the statistical evaluation, the data were analyzed with SPSS version 26 (IBM Corp.). The mean values, standard deviations and confidence intervals were calculated. Both parametric (ANOVA) and non-parametric (Mann-Whitney U test) tests were used. A significance level of 5 % was applied. All results were interpreted to confirm the hypothesis.

3. Results

The main objective of this study was to analyze the accessory canals of the canalis sinuosus with regard to their position, diameter and distance to adjacent teeth, especially with regard to possible subsequent implant placement after tooth loss in the anterior maxilla.

3.1. Data Analysis

To investigate the accessory canals of the canalis sinuosus, the data of 210 patients were evaluated in a descriptive and an explorative analysis. These were divided into three age-dependent groups of 70 patients each:

Group 1: Participants under 41 years of age (average age 32.4 years).

Group 2: Participants aged 41 to 60 years (average age 50.5 years).

Group 3: Participants over 60 years old (average age 68.7 years).

The youngest study participant was 14 years old, the oldest 79 years old. Overall, the gender distribution was balanced with 105 men and 105 women (50%).

3.2. Analysis of Duct Localization, Duct Quantities and Diameter

In the 210 cases, the number, position and diameter of the accessory foramina of the canalis sinuosus were analyzed. A total of 555 foramina were identified:

Group 1: 180 foramina (66 patients, 32.4 %).

Group 2: 200 foramina (69 patients, 36.1 %).

Group 3: 175 foramina (69 patients, 31.5 %).

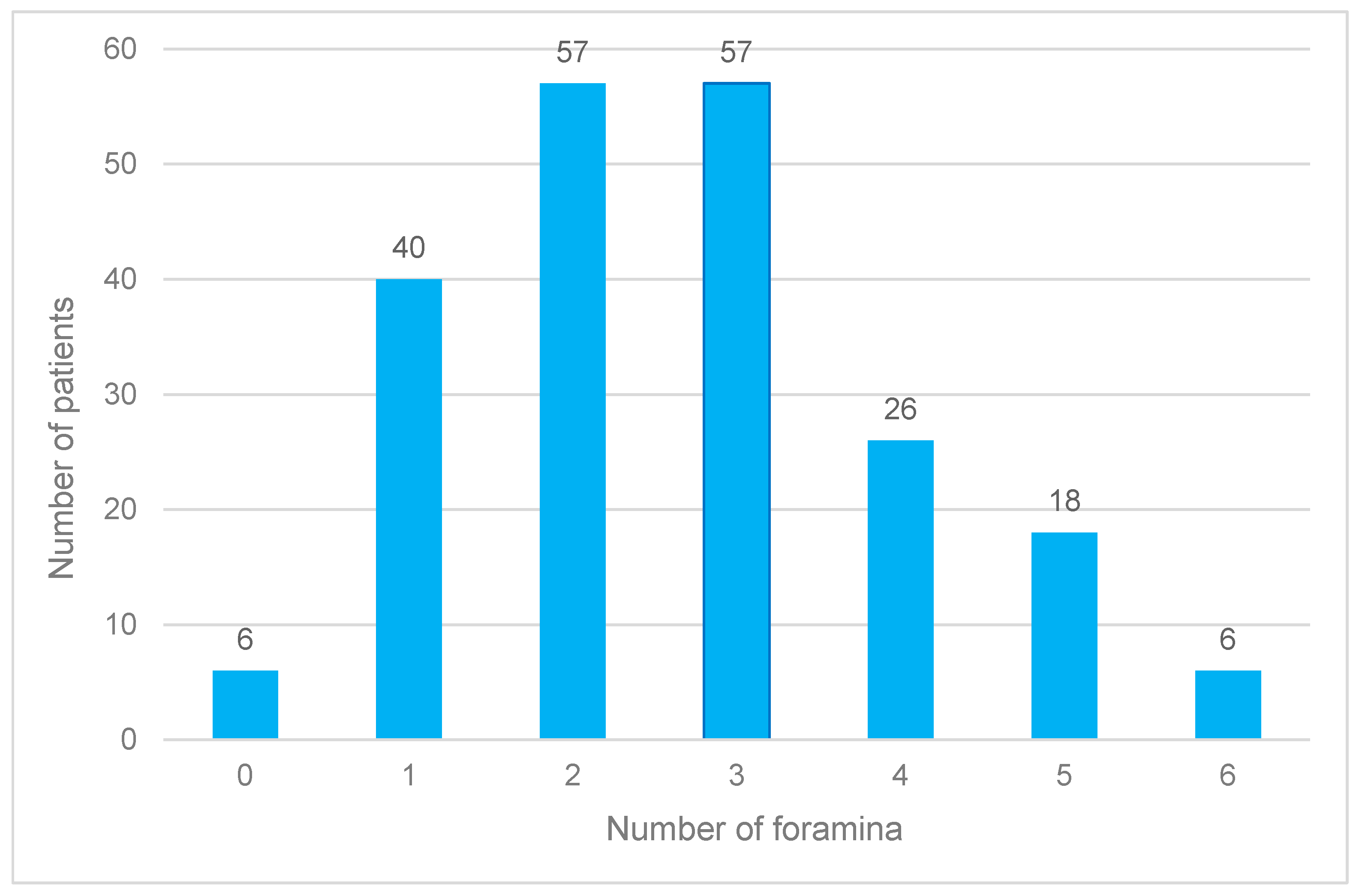

Men (51.5 % of the subjects) had 307 foramina (55 %), women (48.5 %) 248 (45 %). The most common number of foramina per patient was two or three (27.1% each). One, four or five foramina occurred less frequently, while six or no foramina were observed in only 2.9% of participants (

Figure 4).

On average, 2.6 foramina were recorded per patient, with men being affected more frequently (2.9 foramina) than women (2.3 foramina). This difference was significant. While at least one foramen was always detectable in men, no foramina were found in six women.

In terms of age, group 2 had the highest number of foramina with an average of 2.8, followed by group 3 (2.5) and group 1 (2.6). These differences were not significant. The mean axial diameter across all ages was 0.9 mm, with women having smaller diameters on average (0.8 mm) than men (0.9 mm). The maximum axial diameter was 1.9 mm, with gender-specific variations: Men showed larger maximum values than women, especially in group 1.

The most common location of the foramina was medio-palatal to tooth 22. Other common locations were medio-palatal to tooth 12 and proximal between teeth 22 and 23. Men more frequently had foramina close to tooth 22, while women more frequently had them medio-palatal to tooth 12 (

Figure 5).

3.3. Analysis of Distance Measurements in the Axial and Sagittal Plane

The same patient population was used for the distance measurements. The axial distance between the outer edge of a foramen and the pulp wall of the nearest tooth was 4.6 mm on average. On average, men had larger distances (4.8 mm) than women (4.5 mm). The distance increased with increasing age up to 60 years, but stagnated in older men. The minimum axial distance was 2.1 mm in men and 2.0 mm in women. The maximum distance was 10.1 mm regardless of age, but was lower in younger women at 7.1 mm.

In the sagittal plane, the average distance was 2.7 mm, with women showing slightly lower values. Older patients tended to have smaller maximum distances, regardless of gender. Overlaps between the canal and tooth or the defined measuring line occurred in 75 % of sagittal measurements, more frequently in men than in women.

Of the 551 foramina, 30 % were closer than 5 mm to the nearest tooth in the axial plane and 21 % in the sagittal plane. The remaining four foramina could not be clearly localized. None of the measured variables showed significant age- or gender-specific differences.

4. Discussion

Understanding the anatomical structures in the anterior maxilla is essential for dentists who perform surgery in order to avoid complications. For example, there is a risk of injury to neurovascular structures during implant surgery, which in many cases can lead to increased bleeding or sensory impairment [

18,

19].

Digital volume tomography (CBCT) enables precise visualization of the bony structures in the surgical site through three-dimensional imaging and supports preoperative planning through software-supported measurement of adjacent anatomical features [

16,

20]. This technology is of crucial importance not only for implant planning, but also for endosurgical procedures or the removal of impacted teeth in the maxillary front in order to minimize intraoperative complications [

20].

Since the canalis sinuosus and its accessory canals are often unknown in clinical practice, this study aimed to analyze their prevalence and changes over time in order to gain clinically relevant insights. In addition, the results of this study were compared with current literature. The study by Machado et al. served as a reference and was supplemented by other studies, including those by Oliveira-Santos et al, von Arx et al, and Orhan et al [

2,

4,

5,

7,

8,

9,

21,

22].

4.1. Discussion of the Method

Digital volume tomography (CBCT) was used to examine the relevant bony structures, as it enables precise visualization of the localization and course of accessory bone canals

Two-dimensional images are unsuitable due to the small dimensions of the canals and the potential risk of confusion with inflammatory changes [

23]. The device used (GXCB-500, Gendex Dental Systems, USA) offers a resolution of 0.2 mm, which enabled high-precision measurements. The seated positioning of the patients reduced movement artifacts and improved the image quality.

The analysis was carried out in two steps: First, the number and extent of the accessory canals were examined in the axial and sagittal planes. Then the distances of the foramina to neighboring teeth or to the buccal cortical bone were measured. Measuring the maximum diameter of the canals posed a particular challenge, as the canal had to be clearly recognizable in both planes. Due to individual differences and the lack of blinded control measurements, inter-individual variations are likely.

4.2. Discussion of the Results

The results were analyzed by axial and sagittal plane as well as by age group and gender. Similar to the study by Shan et al [

8], foramina from a diameter of 1 mm were examined. A gender-specific comparison showed that men had significantly more foramina than women, although the differences in the mean values of the maximum diameters of the canals were small (men: 1.03 mm, women: 0.96 mm).

There were clear but not significant differences between the age groups. While the distances increased with increasing age in the axial plane, they decreased in the sagittal plane from the youngest to the oldest group. Changes in the number and diameter of the foramina over time could not be clearly demonstrated due to the small number of patients.

However, the study revealed clinically relevant findings for implant planning. Based on the average distances of 4.6 mm (axial) and 2.7 mm (sagittal), there was a high risk of perforation of accessory canals when implants are placed in the anterior maxilla, especially when space is at a minimum. The choice of implant diameter and the implant position play a decisive role here. Safety distances of at least 1.5 mm to adjacent teeth and 3 mm to adjacent implants should be maintained.

4.3. Comparison with Current Studies

The prevalence of accessory canals is reported in the literature with a considerable range between 15.7 % and 100 % [

24,

25]. This variability is due to different examination methods, image resolutions and inclusion and exclusion criteria. The present study found a prevalence of 97%, which is high compared to the results of other studies. This is due to the fact that smaller canals (< 1 mm) were also included.

In their study, Machado et al. (2016) found at least one foramen of the canalis sinuosus in 52.1% of the patients examined [

6]. In contrast, Wanzeler et al. reported a prevalence of 36.9 %, whereby only canals with a diameter of at least 1 mm were examined [

2]. Orhan et al. (2018) found a prevalence of 72.2 % in women and 69.7 % in men, which was also due to the inclusion of only larger canals [

7]. These results make it clear that the recording method and the specified minimum size of the ducts have a considerable influence on the prevalence data.

Another important feature of the present study is the gender-specific analysis. This showed that men tended to have more foramina of the canalis sinuosus than women, which is also consistent with the studies of Orhan et al. and Machado et al. However, it should be noted that the differences between the sexes were significantly more pronounced, especially for larger foramina (> 1 mm) [

6,

7].

With regard to the localization of the accessory canals, the results of the present study are largely consistent with the literature. Most studies report that the highest prevalence is in the vicinity of the central incisors or the lateral incisors. This was also confirmed in studies by von Arx et al., Oliveira-Santos et al. and Wanzeler et al [

8,

21,

22]. The distances to neighboring teeth and the buccal cortical bone varied in the different studies, whereby the results of the present study were within the existing variability.

A particularly noteworthy aspect is the comparison of the results with the study by Shan et al. (2021). They determined a prevalence of 36.9 % in a comparable patient cohort, although a lower image resolution was used. This study confirms the assumption that higher image quality enables more precise detection and measurement of smaller channels [

8].

In addition to the prevalence and localization, the change in the number and size of the accessory canals over time was also investigated. There are only a few studies on this to date, but they also point to an age-related increase in canal spacing. For example, both Beyzade et al. and Tomrukcu et al. reported an increase in spacing with increasing age, which can be attributed to progressive bone degeneration and remodeling [

2,

9]. Although the present study was able to confirm this observation, the number of patients per age group was too small to demonstrate significant differences.

Another relevant aspect is the clinical relevance of the results, especially with regard to implant planning. The identified safety margins of 4.6 mm on average in the axial plane and 2.7 mm in the sagittal plane should be taken into account when selecting the implant position and size. These results confirm the recommendations of Esposito et al. (1998), who suggested a safety distance of at least 1.5 mm to adjacent teeth and 3 mm to adjacent implants [

26].

5. Clinical Relevance

The results underline the importance of precise preoperative planning, taking into account the neighboring anatomical structures. The use of navigated implantation techniques is particularly recommended where space is limited. Case reports show that complications due to perforations of the sinuosal canal can be avoided by careful planning and the selection of suitable implant lengths [

27,

28].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Sigmar Schnutenhaus and Constanze Olms; Methodology, Sigmar Schnutenhaus, Werner Götz and Constanze Olms; Software, Christian Heckemann; Validation, Werner Götz; Formal analysis, Sigmar Schnutenhaus; Investigation, Sigmar Schnutenhaus and Christian Heckemann; Data curation, Christian Heckemann; Writing – original draft, Christian Heckemann; Writing – review & editing, Sigmar Schnutenhaus; Supervision, Werner Götz and Constanze Olms.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gurler, G.; Delilbasi, C.; Ogut, E.E.; Aydin, K.; Sakul, U. Evaluation of the morphology of the canalis sinuosus using cone-beam computed tomography in patients with maxillary impacted canines. Imaging Sci Dent 2017, 47, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wanzeler, A.M.; Marinho, C.G.; Alves Junior, S.M.; Manzi, F.R.; Tuji, F.M. Anatomical study of the canalis sinuosus in 100 cone beam computed tomography examinations. Oral Maxillofac Surg 2015, 19, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arruda, J.A.; Silva, P.; Silva, L.; Alvares, P.; Silva, L.; Zavanelli, R.; et al. Dental Implant in the Canalis Sinuosus: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Case Rep Dent 2017, 2017, 4810123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Oliveira-Santos, C.; Rubira-Bullen, I.R.; Monteiro, S.A.; Leon, J.E.; Jacobs, R. Neurovascular anatomical variations in the anterior palate observed on CBCT images. Clin Oral Implants Res 2013, 24, 1044–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghandourah, A.O.; Rashad, A.; Heiland, M.; Hamzi, B.M.; Friedrich, R.E. Cone-beam tomographic analysis of canalis sinuosus accessory intraosseous canals in the maxilla. Ger Med Sci 2017, 15, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Machado, V.C.; Chrcanovic, B.R.; Felippe, M.B.; Manhaes Junior, L.R.; de Carvalho, P.S. Assessment of accessory canals of the canalis sinuosus: a study of 1000 cone beam computed tomography examinations. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2016, 45, 1586–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orhan, K.; Gorurgoz, C.; Akyol, M.; Ozarslanturk, S.; Avsever, H. An anatomical variant: evaluation of accessory canals of the canalis sinuosus using cone beam computed tomography. Folia Morphol (Warsz) 2018, 77, 551–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, T.; Qu, Y.; Huang, X.; Gu, L. Cone beam computed tomography analysis of accessory canals of the canalis sinuosus: A prevalent but often overlooked anatomical variation in the anterior maxilla. J Prosthet Dent 2021, 126, 560–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomrukcu, D.N.; Kose, T.E. Assesment of accessory branches of canalis sinuosus on CBCT images. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 2020, 25, e124–e130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radlanski, R.J.; Emmerich, S.; Renz, H. Prenatal morphogenesis of the human incisive canal. Anat Embryol (Berl) 2004, 208, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitamura, H. Embryology of the mouth and related structures. Development of nasopalatine ducts. Tokyo: Maruzen, 1976, 1153-1155.

- Kämmerer, P.; Lehmann, k. Nervschäden? Komplikationen nach Implantatinsertionen im anterioren Oberkiefer. Z Zahnärztl Implantologie 2020, 36, 14–16. [Google Scholar]

- Gaeta-Araujo, H.; Oliveira-Santos, N.; Mancini AXM, Oliveira, M. L.; Oliveira-Santos, C. Retrospective assessment of dental implant-related perforations of relevant anatomical structures and inadequate spacing between implants/teeth using cone-beam computed tomography. Clin Oral Investig 2020, 24, 3281–3288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, M.; Dantas, L.; Rodrigues, R.; Fagundes, F.; Rosado, L.; Neves, F. Facial pain due to contact between dental implant with the Canalis Sinousus. Journal of Helath and Biological Sciencess 2022, 10, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Buser, D.; Martin, W.; Belser, U.C. Optimizing esthetics for implant restorations in the anterior maxilla: anatomic and surgical considerations. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 2004, 19, 43–61. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dau, M.; Edalatpour, A.; Schulze, R.; Al-Nawas, B.; Alshihri, A.; Kammerer, P.W. Presurgical evaluation of bony implant sites using panoramic radiography and cone beam computed tomography-influence of medical education. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2017, 46, 20160081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manhaes Junior, L.R.; Villaca-Carvalho, M.F.; Moraes, M.E.; Lopes, S.L.; Silva, M.B.; Junqueira, J.L. Location and classification of Canalis sinuosus for cone beam computed tomography: avoiding misdiagnosis. Braz Oral Res 2016, 30, e49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, R.; Quirynen, M.; Bornstein, M.M. Neurovascular disturbances after implant surgery. Periodontol 2000 2014, 66, 188–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelley, A.; Tinning, J.; Yates, J.; Horner, K. Potential neurovascular damage as a result of dental implant placement in the anterior maxilla. Br Dent J 2019, 226, 657–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bliggenstorfer, S.; Chappuis, V.; von Arx, T. [Misinterpretation of a periapical radiograph: the canalis sinuosus mimicking a root resorption]. Swiss Dent J 2021, 131, 999–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Arx, T.; Lozanoff, S.; Sendi, P.; Bornstein, M.M. Assessment of bone channels other than the nasopalatine canal in the anterior maxilla using limited cone beam computed tomography. Surg Radiol Anat 2013, 35, 783–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyzade, Z.; Yilmaz, H.G.; Unsal, G.; Caygur-Yoran, A. Prevalence, Radiographic Features and Clinical Relevancy of Accessory Canals of the Canalis Sinuosus in Cypriot Population: A Retrospective Cone-Beam Computed Tomography (CBCT) Study. Medicina (Kaunas) 2022, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, P.N.; Arora, A.V.; Kapoor, S.V. Accessory branch of canalis sinuosus mimicking external root resorption: A diagnostic dilemma. J Conserv Dent 2017, 20, 479–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aoki, R.; Massuda, M.; Zenni LTV, Fernandes, K. S. Canalis sinuosus: anatomical variation or structure? Surg Radiol Anat 2020, 42, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira-Neto, O.B.; Barbosa, F.T.; de Lima FJC, de Sousa-Rodrigues, C. F. Prevalence of canalis sinuosus and accessory canals of canalis sinuosus on cone beam computed tomography: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2023, 52, 118–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, M.; Hirsch, J.M.; Lekholm, U.; Thomsen, P. Biological factors contributing to failures of osseointegrated oral implants. (I). Success criteria and epidemiology. Eur J Oral Sci 1998, 106, 527–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orth, C.C.; Orth, C.; Orth, C.C.; da Silva, L.; Streb, M.H.; Dos Reis Bueno, M. A 3-year follow-up of implant placement in proximity to canalis sinuosus: Case study. Clin Adv Periodontics 2024. [CrossRef]

- Rosano, G.; Testori, T.; Clauser, T.; Del Fabbro, M. Management of a neurological lesion involving Canalis Sinuosus: A case report. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res 2021, 23, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).