Submitted:

18 December 2025

Posted:

19 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

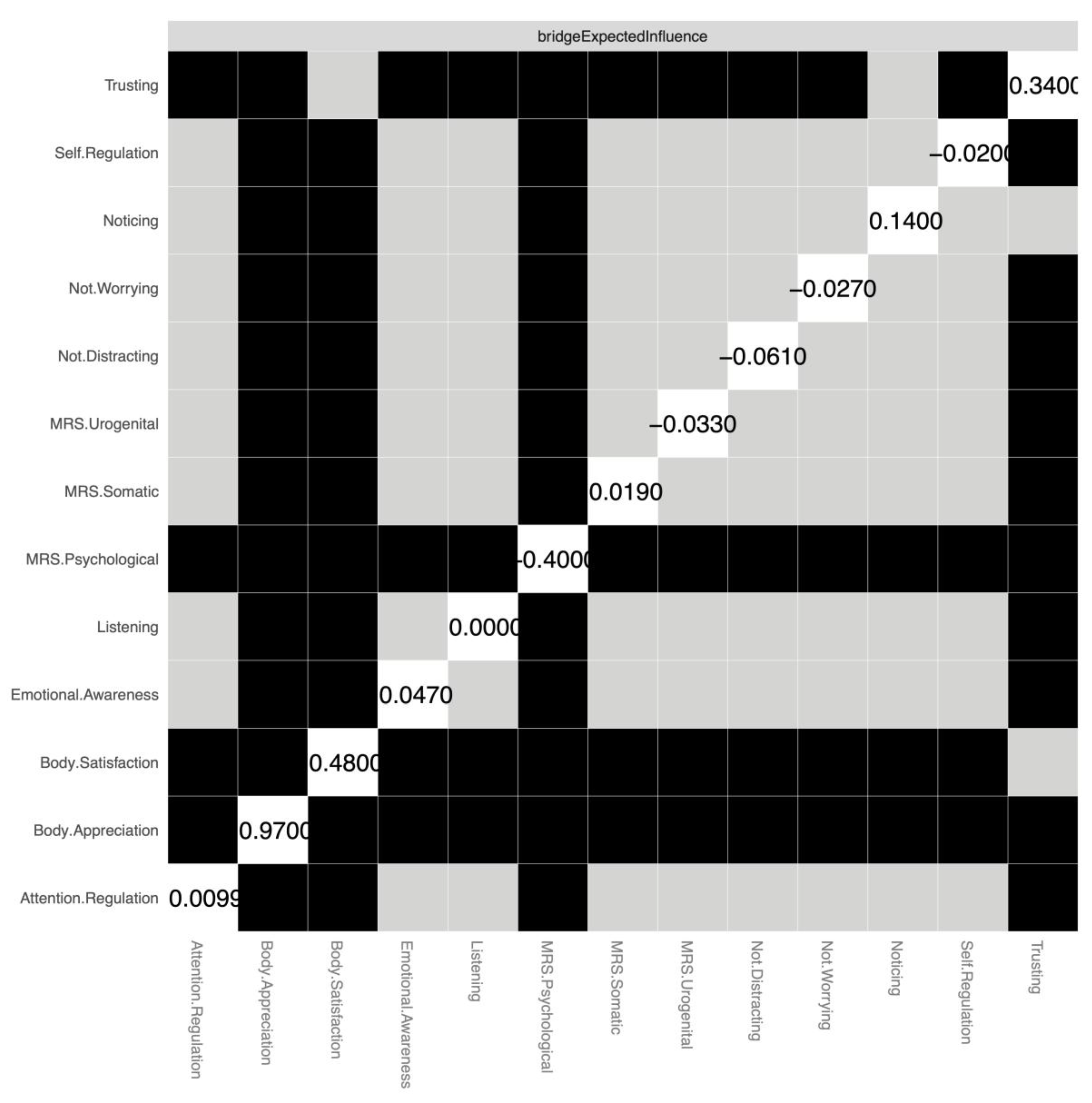

Background: Midlife is a period of heightened vulnerability to menopausal symptoms and body image concerns. However, little is known about how the experience of menopausal symptoms relates to the awareness of and attention toward internal body signals. Taking a dimensional approach, this study employed network analysis to examine how menopausal symptom domains relate to dimensions of interoceptive sensibility and body image in middle-aged women and identified the most influential and bridging features within this interconnected system. Methods: Two hundred and thirteen cisgender women aged 40–60 years residing in Ireland completed online measures of body appreciation (BAS-2), state body satisfaction (BISS), interoceptive sensibility (MAIA-2), and menopausal symptoms (Menopause Rating Scale). Results: Attention Regulation, Trusting, Body Appreciation, and Body Listening showed the highest expected influence. Body Appreciation emerged as the strongest bridge node, connecting interoceptive sensibility, body image, and menopausal symptoms. Trusting was negatively associated with psychological symptoms, whereas Noticing was positively associated with somatic symptoms. Regression analyses showed that lower body appreciation predicted greater somatic, urogenital, and psychological symptom severity, and lower Trusting predicted higher psychological symptom severity. Older age was associated with higher somatic and urogenital symptoms, while younger age was associated with higher psychological symptoms. Conclusions: Findings suggest that body appreciation and interoceptive trust are central, bridging processes in women’s experience of menopausal symptoms. Interventions that enhance body appreciation and interoceptive trust may help reduce psychological and physical symptom burden during the menopausal transition.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

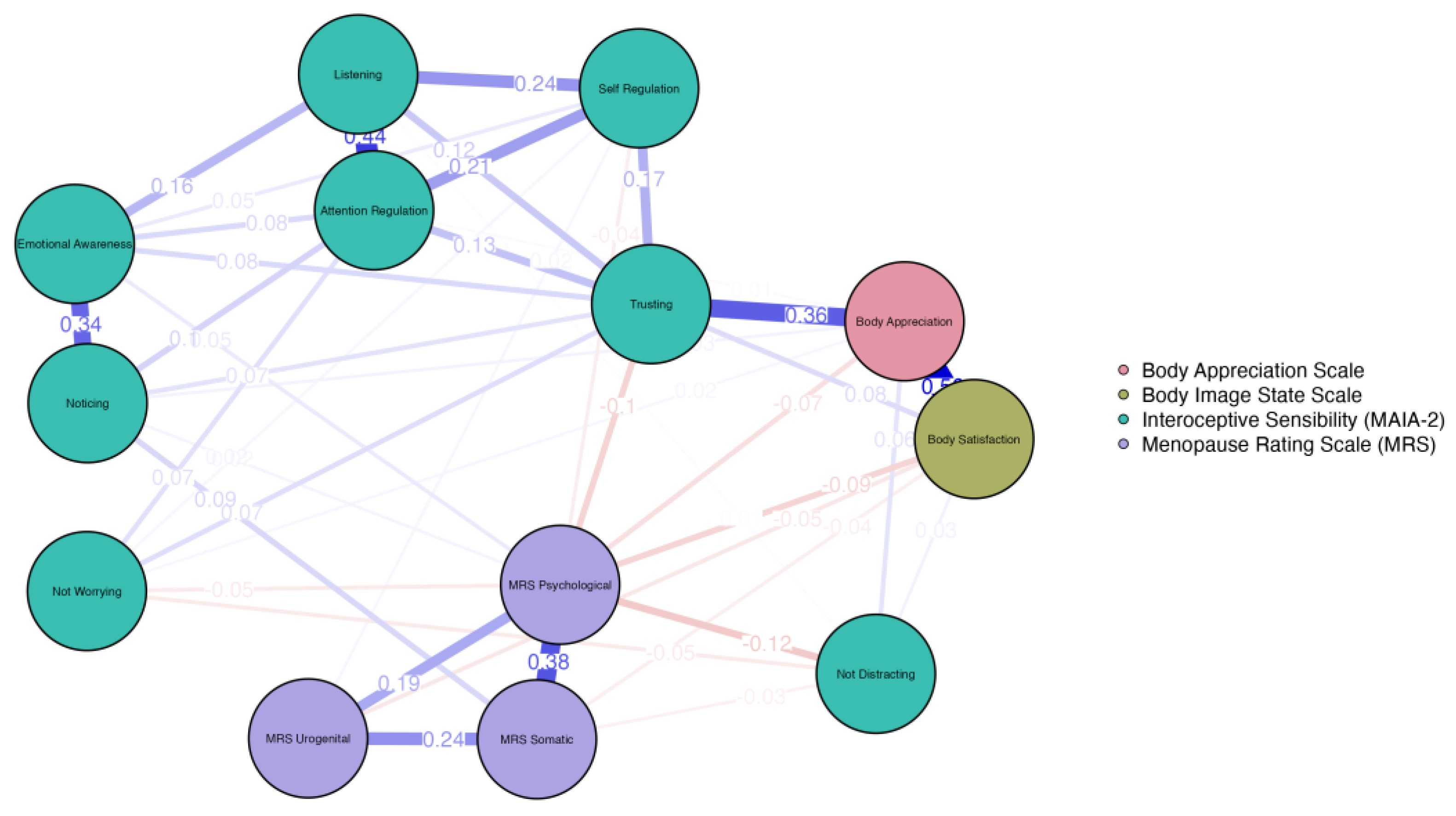

3.2. Network Estimation and Visualisation

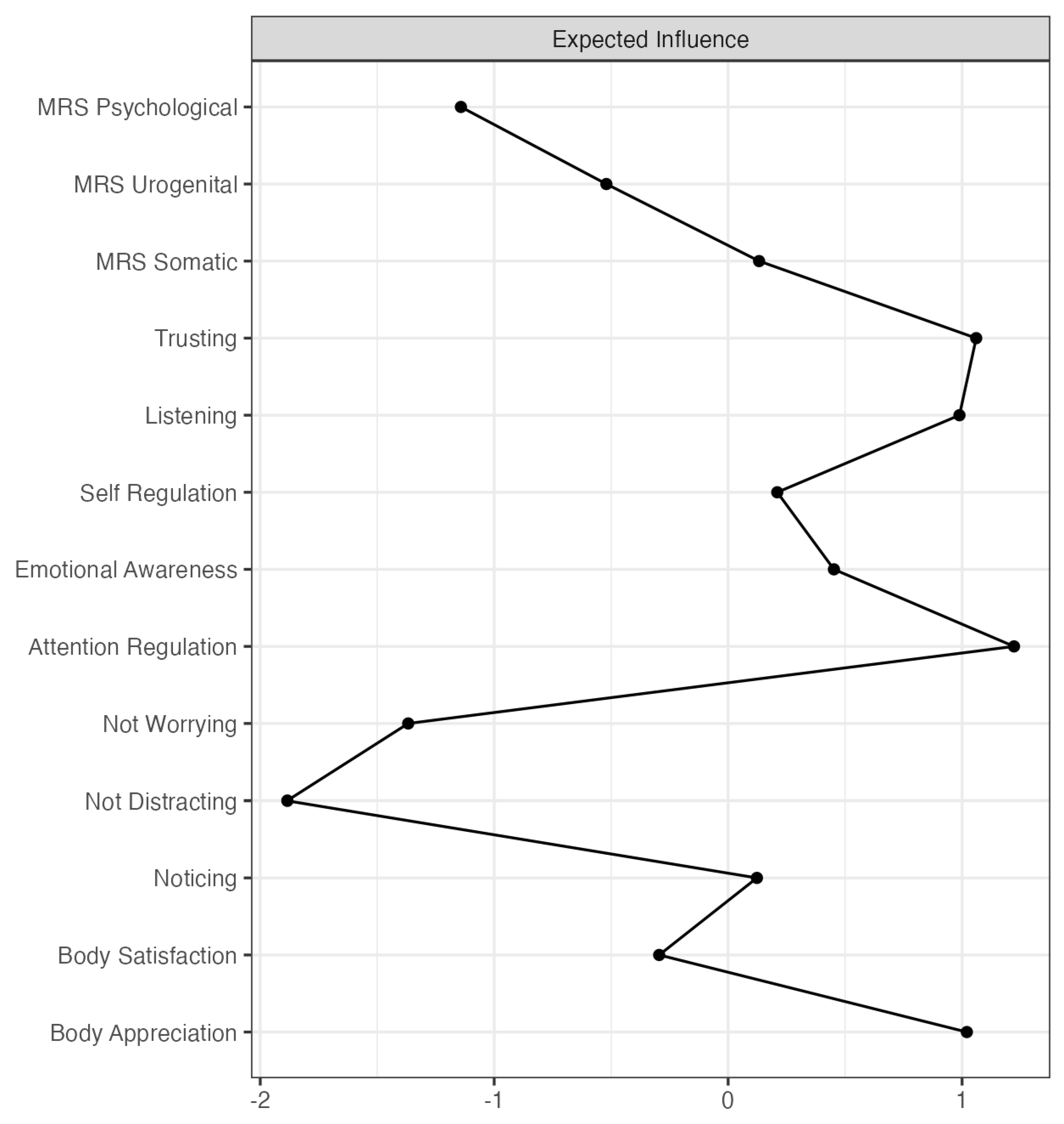

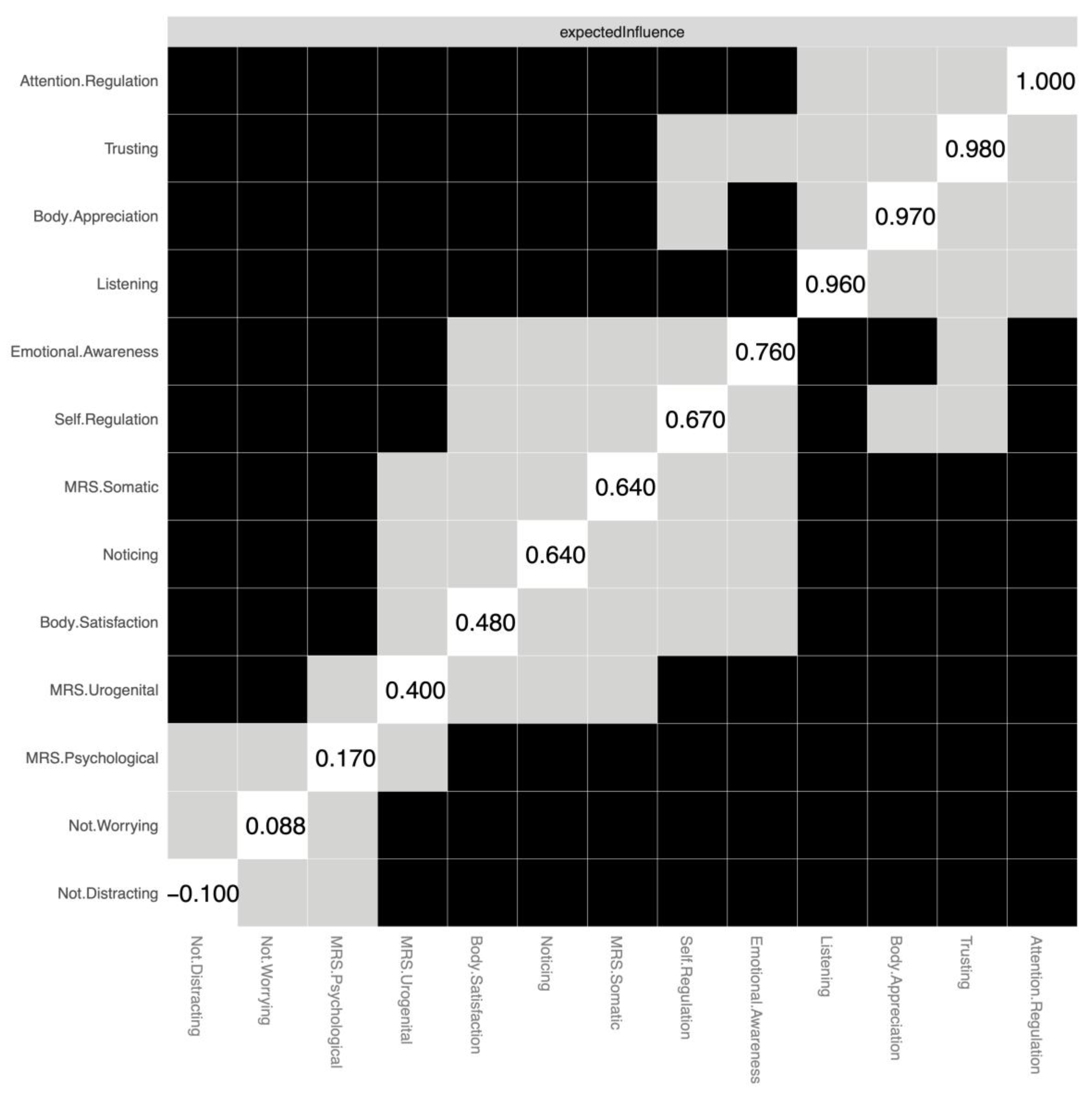

3.3. Centrality and Expected Influence

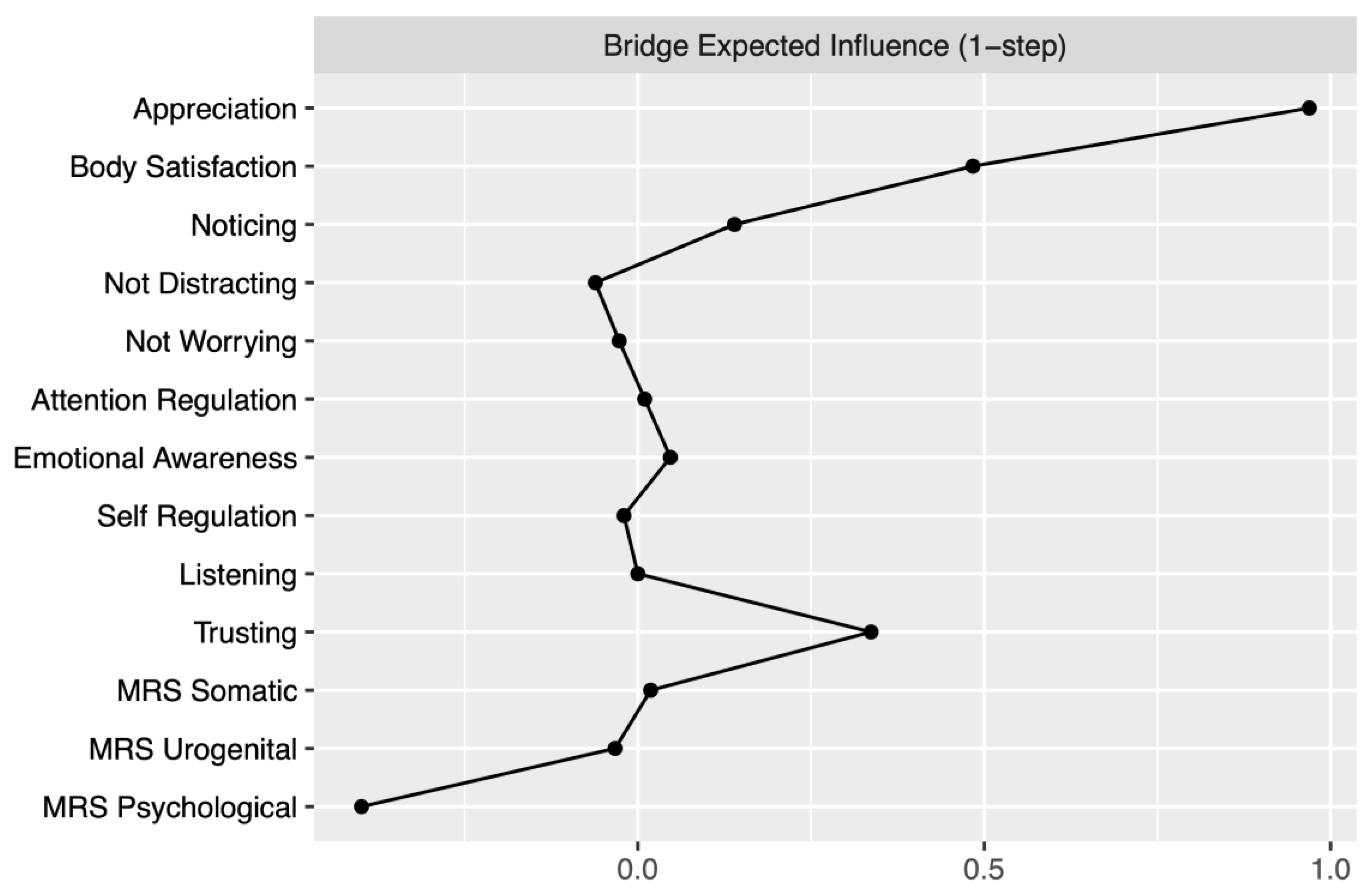

3.4. Bridge Pathways

3.5. Is Age Related to Menopause Symptom Severity?

3.6. Do the Most Influential Interoceptive Sensibility and Body Image Features Predict Menopausal Symptom Severity?

4. Discussion

Interoceptive Sensibility, Body Image, and Central Nodes

Bridge Pathways Between Menopausal Symptoms, Interoception, and Body Image

Predicting Menopausal Symptom Severity

Age and HRT Patterns

Implications for Interoception, Body Image, and Women’s Health

Strengths and Limitations

Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ | Directory of open access journals |

| TLA | Three letter acronym |

| LD | Linear dichroism |

References

- Delanerolle, G.; Phiri, P.; Elneil, S.; Talaulikar, V.; Eleje, G.U.; Kareem, R.; Shetty, A.; Saraswath, L.; Kurmi, O.; Benetti-Pinto, C.L.; et al. Menopause: A Global Health and Wellbeing Issue That Needs Urgent Attention. Lancet Glob. Health 2025, 13, e196–e198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harlow, S.D.; Paramsothy, P. Menstruation and the Menopausal Transition. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. North Am. 2011, 38, 595–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, J.; Wang, Y.-H. Association between Depressive Mood and Body Image and Menopausal Symptoms and Sexual Function in Perimenopausal Women. World J. Clin. Cases 2023, 11, 7761–7769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Dea, J.A.; Abraham, S. Onset Of Disordered Eating Attitudes And Behaviors In Early Adolescence: Interplay Of Pubertal Status, Gender, Weight, And Age. Adolescence 1999, 34, 671–671. [Google Scholar]

- Vincent, C.; Bodnaruc, A.M.; Prud’homme, D.; Olson, V.; Giroux, I. Associations between Menopause and Body Image: A Systematic Review. Womens Health 2023, 19, 17455057231209536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cash, T.F. Body Image: Past, Present, and Future. Body Image 2004, 1, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homan, K.J.; Tylka, T.L. Self-Compassion Moderates Body Comparison and Appearance Self-Worth’s Inverse Relationships with Body Appreciation. Body Image 2015, 15, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alleva, J.M.; Tylka, T.L. Body Functionality: A Review of the Literature. Body Image 2021, 36, 149–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tylka, T.L.; Wood-Barcalow, N.L. The Body Appreciation Scale-2: Item Refinement and Psychometric Evaluation. Body Image 2015, 12, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avalos, L.; Tylka, T.L.; Wood-Barcalow, N. The Body Appreciation Scale: Development and Psychometric Evaluation. Body Image 2005, 2, 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craig, A.D. How Do You Feel? Interoception: The Sense of the Physiological Condition of the Body. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2002, 3, 655–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garfinkel, S.N.; Seth, A.K.; Barrett, A.B.; Suzuki, K.; Critchley, H.D. Knowing Your Own Heart: Distinguishing Interoceptive Accuracy from Interoceptive Awareness. Biol. Psychol. 2015, 104, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naraindas, A.M.; Cooney, S.M. Body Image Disturbance, Interoceptive Sensibility and the Body Schema across Female Adulthood: A Pre-Registered Study. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1285216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd, J.; Aspell, J.E.; Barron, D.; Swami, V. Multiple Dimensions of Interoceptive Awareness Are Associated with Facets of Body Image in British Adults. Body Image 2019, 29, 6–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badoud, D.; Tsakiris, M. From the Body’s Viscera to the Body’s Image: Is There a Link between Interoception and Body Image Concerns? Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2017, 77, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naraindas, A.; McInerney, A.; Deschênes, S.S.; Cooney, S.M. Differences in the Relationships between Interoceptive Sensibility and Self-Objectification in Women with High and Low Body Dissatisfaction: A Network Analysis. PLoS One. 2025, 20, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naraindas, A.M.; Moreno, M.; Cooney, S.M. Beyond Gender: Interoceptive Sensibility as a Key Predictor of Body Image Disturbances. Behav. Sci. 2023, 14, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todd, J.; Aspell, J.E.; Barron, D.; Swami, V. An Exploration of the Associations between Facets of Interoceptive Awareness and Body Image in Adolescents. Body Image 2019, 31, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Honelová, M.; Vidovićová, L. Why Do (Middle-Aged) Women Undergo Cosmetic/Aesthetic Surgery? Scoping Review. Womens Stud. Int. Forum 2023, 101, 102842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilpela, L.S.; Becker, C.B.; Wesley, N.; Stewart, T. Body Image in Adult Women: Moving beyond the Younger Years. Adv. Eat. Disord. 2015, 3, 144–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis-Smith, H.; Diedrichs, P.C.; Rumsey, N.; Harcourt, D. A Systematic Review of Interventions on Body Image and Disordered Eating Outcomes among Women in Midlife. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2016, 49, 434–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiggemann, M. Body Image across the Adult Life Span: Stability and Change. Body Image 2004, 1, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, S. Defining the Menopausal Transition. Am. J. Med. 2005, 118, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avis, N.E.; Crawford, S.L.; Green, R. Vasomotor Symptoms Across the Menopause Transition. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. North Am. 2018, 45, 629–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoro, N.; Roeca, C.; Peters, B.A.; Neal-Perry, G. The Menopause Transition: Signs, Symptoms, and Management Options. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 106, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteleone, P.; Mascagni, G.; Giannini, A.; Genazzani, A.R.; Simoncini, T. Symptoms of Menopause — Global Prevalence, Physiology and Implications. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2018, 14, 199–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambleton, A.; Pepin, G.; Le, A.; Maloney, D.; Aouad, P.; Barakat, S.; Boakes, R.; Brennan, L.; Bryant, E.; et al.; National Eating Disorder Research Consortium Psychiatric and Medical Comorbidities of Eating Disorders: Findings from a Rapid Review of the Literature. J. Eat. Disord. 2022, 10, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangweth-Matzek, B.; Rupp, C.I.; Vedova, S.; Dunst, V.; Hennecke, P.; Daniaux, M.; Pope, H.G. Disorders of Eating and Body Image during the Menopausal Transition: Associations with Menopausal Stage and with Menopausal Symptomatology. Eat. Weight Disord. - Stud. Anorex. Bulim. Obes. 2021, 26, 2763–2769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temple, S.; Hogervorst, E.; Witcomb, G.L. Differences in Menopausal Quality of Life, Body Appreciation, and Body Dissatisfaction between Women at High and Low Risk of an Eating Disorder. Brain Behav. 2024, 14, e3609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gagne, D.A.; Von Holle, A.; Brownley, K.A.; Runfola, C.D.; Hofmeier, S.; Branch, K.E.; Bulik, C.M. Eating Disorder Symptoms and Weight and Shape Concerns in a Large Web-based Convenience Sample of Women Ages 50 and above: Results of the Gender and Body Image (GABI) Study. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2012, 45, 832–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Runfola, C.D.; Von Holle, A.; Trace, S.E.; Brownley, K.A.; Hofmeier, S.M.; Gagne, D.A.; Bulik, C.M. Body Dissatisfaction in Women Across the Lifespan: Results of the UNC- SELF and Gender and Body Image (GABI) Studies. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2013, 21, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinley, N.M.; Lyon, L.A. Menopausal Attitudes, Objectified Body Consciousness, Aging Anxiety, and Body Esteem: European American Women’s Body Experiences in Midlife. Body Image 2008, 5, 375–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, L.; Gringart, E. Body Image and Self-Esteem in Older Adulthood. Ageing Soc. 2009, 29, 977–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosselink, C.A.; Cox, D.L.; McClure, S.J.; De Jong, M.L.G. Ravishing or Ravaged: Women’s Relationships with Women in the Context of Aging and Western Beauty Culture. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 2008, 66, 307–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, L.; Hunter, M.S.; Chen, R.; Crandall, C.J.; Gordon, J.L.; Mishra, G.D.; Rother, V.; Joffe, H.; Hickey, M. Promoting Good Mental Health over the Menopause Transition. The Lancet 2024, 403, 969–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harden, K.P.; Kretsch, N.; Moore, S.R.; Mendle, J. Descriptive Review: Hormonal Influences on Risk for Eating Disorder Symptoms during Puberty and Adolescence. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2014, 47, 718–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildebrandt, B.A.; Racine, S.E.; Keel, P.K.; Burt, S.A.; Neale, M.; Boker, S.; Sisk, C.L.; Klump, K.L. The Effects of Ovarian Hormones and Emotional Eating on Changes in Weight Preoccupation across the Menstrual Cycle. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2015, 48, 477–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klump, K.L. Puberty as a Critical Risk Period for Eating Disorders: A Review of Human and Animal Studies. Horm. Behav. 2013, 64, 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, J.H.; Peterson, C.M.; Thornton, L.M.; Brownley, K.A.; Bulik, C.M.; Girdler, S.S.; Marcus, M.D.; Bromberger, J.T. Reproductive and Appetite Hormones and Bulimic Symptoms during Midlife. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2017, 25, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, J.H.; Eisenlohr-Moul, T.; Wu, Y.-K.; Schiller, C.E.; Bulik, C.M.; Girdler, S.S. Ovarian Hormones Influence Eating Disorder Symptom Variability during the Menopause Transition: A Pilot Study. Eat. Behav. 2019, 35, 101337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elran-Barak, R.; Fitzsimmons-Craft, E.E.; Benyamini, Y.; Crow, S.J.; Peterson, C.B.; Hill, L.L.; Crosby, R.D.; Mitchell, J.E.; Le Grange, D. Anorexia Nervosa, Bulimia Nervosa, and Binge Eating Disorder in Midlife and Beyond. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2015, 203, 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangweth-Matzek, B.; Hoek, H.W.; Rupp, C.I.; Kemmler, G.; Pope, H.G.; Kinzl, J. The Menopausal Transition—A Possible Window of Vulnerability for Eating Pathology. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2013, 46, 609–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, S.; Gomes, A.; Singh, R.S. Is Menopause Still Evolving? Evidence from a Longitudinal Study of Multiethnic Populations and Its Relevance to Women’s Health. BMC Womens Health 2020, 20, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, E.B. The Timing of the Age at Which Natural Menopause Occurs. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. North Am. 2011, 38, 425–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansfield, P.K.; Carey, M.; Anderson, A.; Barsom, S.H.; Koch, P.B. Staging the Menopausal Transition: Data from the TREMIN Research Program on Women’s Health. Womens Health Issues 2004, 14, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, J.H.; Peterson, C.M.; Thornton, L.M.; Brownley, K.A.; Bulik, C.M.; Girdler, S.S.; Marcus, M.D.; Bromberger, J.T. Reproductive and Appetite Hormones and Bulimic Symptoms during Midlife. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2017, 25, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deeks, A.A.; McCabe, M.P. Menopausal Stage and Age and Perceptions of Body Image. Psychol. Health 2001, 16, 367–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, D.; Lomranz, J.; Pines, A.; Shmotkin, D.; Nitza, E.; Bennamitay, G.; Mester, R. Psychological Distress Around Menopause. Psychosomatics 2001, 42, 252–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazarpour, S.; Simbar, M.; Majd, H.A.; Torkamani, Z.J.; Andarvar, K.D.; Rahnemaei, F. The Relationship between Postmenopausal Women’s Body Image and the Severity of Menopausal Symptoms. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wlodarczyk, M.; Dolinska-Zygmunt, G. Role of the Body Self and Self-Esteem in Experiencing the Intensity of Menopausal Symptoms. Psychiatr. Pol. 2017, 51, 909–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakson-Obada, O.; Wycisk, J. The Body Self and the Frequency, Intensity and Acceptance of Menopausal Symptoms. Menopausal Rev. 2015, 2, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalsa, S.S.; Lapidus, R.C. Can Interoception Improve the Pragmatic Search for Biomarkers in Psychiatry? Front. Psychiatry 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, R.; Murphy, J.; Bird, G. Atypical Interoception as a Common Risk Factor for Psychopathology: A Review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2021, 130, 470–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, J.; Viding, E.; Bird, G. Does Atypical Interoception Following Physical Change Contribute to Sex Differences in Mental Illness? Psychol. Rev. 2019, 126, 787–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borlimi, R.; Buattini, M.; Riboli, G.; Nese, M.; Brighetti, G.; Giunti, D.; Vescovelli, F. Menstrual Cycle Symptomatology during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Role of Interoceptive Sensibility and Psychological Health. Compr. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2023, 14, 100182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munns, L.B.; Noonan, M.; Romano, D.L.; Preston, C.E.J. Interoceptive and Exteroceptive Pregnant Bodily Experiences and Postnatal Well-being: A Network Analysis. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2025, 30, e70002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munns, L.B.; Preston, C. The Role of Bodily Experiences during Pregnancy on Mother and Infant Outcomes. J. Neuropsychol. 2025, 19, 131–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballering, A.V.; Bonvanie, I.J.; Olde Hartman, T.C.; Monden, R.; Rosmalen, J.G.M. Gender and Sex Independently Associate with Common Somatic Symptoms and Lifetime Prevalence of Chronic Disease. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 253, 112968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pennebaker, J.W.; Roberts, T.-A. Toward a His and Hers Theory of Emotion: Gender Differences in Visceral Perception. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 1992, 11, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsky, A.J.; Peekna, H.M.; Borus, J.F. Somatic Symptom Reporting in Women and Men. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabauskaitė, A.; Baranauskas, M.; Griškova-Bulanova, I. Interoception and Gender: What Aspects Should We Pay Attention To? Conscious. Cogn. 2017, 48, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor-Swanson, L.J.; Pike, K.; Mitchell, E.S.; Herting, J.R.; Woods, N.F. Self-Awareness and the Evaluation of Hot Flash Severity: Observations from the Seattle Midlife Women’s Health Study. Menopause 2019, 26, 476–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd, J.; Aspell, J.E. Mindfulness, Interoception, and the Body. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terasawa, Y.; Shibata, M.; Moriguchi, Y.; Umeda, S. Anterior Insular Cortex Mediates Bodily Sensibility and Social Anxiety. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2013, 8, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehling, W. Differentiating Attention Styles and Regulatory Aspects of Self-Reported Interoceptive Sensibility. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2016, 371, 20160013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehling, W.E.; Acree, M.; Stewart, A.; Silas, J.; Jones, A. The Multidimensional Assessment of Interoceptive Awareness, Version 2 (MAIA-2). PLOS ONE 2018, 13, e0208034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehling, W.E.; Price, C.; Daubenmier, J.J.; Acree, M.; Bartmess, E.; Stewart, A. The Multidimensional Assessment of Interoceptive Awareness (MAIA). PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e48230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todd, J.; Barron, D.; Aspell, J.E.; Lin Toh, E.K.; Zahari, H.S.; Mohd. Khatib, N.A.; Swami, V. Examining Relationships Between Interoceptive Sensibility and Body Image in a Non-Western Context: A Study With Malaysian Adults. Int. Perspect. Psychol. 2022, 11, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daubenmier, J.J. The Relationship of Yoga, Body Awareness, and Body Responsiveness to Self-Objectification and Disordered Eating. Psychol. Women Q. 2005, 29, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duschek, S.; Werner, N.S.; Reyes Del Paso, G.A.; Schandry, R. The Contributions of Interoceptive Awareness to Cognitive and Affective Facets of Body Experience. J. Individ. Differ. 2015, 36, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oswald, A.; Chapman, J.; Wilson, C. Do Interoceptive Awareness and Interoceptive Responsiveness Mediate the Relationship between Body Appreciation and Intuitive Eating in Young Women? Appetite 2017, 109, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alleva, J.M.; Sheeran, P.; Webb, T.L.; Martijn, C.; Miles, E. A Meta-Analytic Review of Stand-Alone Interventions to Improve Body Image. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0139177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alleva, J.M.; Veldhuis, J.; Martijn, C. A Pilot Study Investigating Whether Focusing on Body Functionality Can Protect Women from the Potential Negative Effects of Viewing Thin-Ideal Media Images. Body Image 2016, 17, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hevey, D. Network Analysis: A Brief Overview and Tutorial. Health Psychol. Behav. Med. 2018, 6, 301–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borsboom, D.; Cramer, A.O.J. Network Analysis: An Integrative Approach to the Structure of Psychopathology. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2013, 9, 91–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, N.F.; Mitchell, E.S. Symptoms during the Perimenopause: Prevalence, Severity, Trajectory, and Significance in Women’s Lives. Am. J. Med. 2005, 118, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cash, T.; Fleming, E.; Alindogan, J.; Steadman, L.; Whitehead, A. Beyond Body Image as a Trait: The Development and Validation of the Body Image States Scale. Eat. Disord. 2002, 10, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinemann, K.; Ruebig, A.; Potthoff, P.; Schneider, H.P.; Strelow, F.; Heinemann, L.A.; Thai, D.M. The Menopause Rating Scale (MRS) Scale: A Methodological Review. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2004, 2, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinemann, K.; Ruebig, A.; Potthoff, P.; Schneider, H.P.; Strelow, F.; Heinemann, L.A.; Thai, D.M. The Menopause Rating Scale (MRS) Scale: A Methodological Review. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2004, 2, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epskamp, S.; Borsboom, D.; Fried, E.I. Estimating Psychological Networks and Their Accuracy: A Tutorial Paper. Behav. Res. Methods 2018, 50, 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epskamp, S.; Fried, E.I. A Tutorial on Regularized Partial Correlation Networks. Psychol. Methods 2018, 23, 617–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epskamp, S.; Cramer, A.O.J.; Waldorp, L.J.; Schmittmann, V.D.; Borsboom, D. Qgraph: Network Visualizations of Relationships in Psychometric Data. J. Stat. Softw. 2012, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.-G. Statistical Power Analyses Using G*Power 3.1: Tests for Correlation and Regression Analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNally, R.J. Can Network Analysis Transform Psychopathology? Behav. Res. Ther. 2016, 86, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borsboom, D.; Deserno, M.K.; Rhemtulla, M.; Epskamp, S.; Fried, E.I.; McNally, R.J.; Robinaugh, D.J.; Perugini, M.; Dalege, J.; Costantini, G.; et al. Network Analysis of Multivariate Data in Psychological Science. Nat. Rev. Methods Primer 2021, 1, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinaugh, D.J.; Millner, A.J.; McNally, R.J. Identifying Highly Influential Nodes in the Complicated Grief Network. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2016, 125, 747–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P.J.; Ma, R.; McNally, R.J. Bridge Centrality: A Network Approach to Understanding Comorbidity. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2021, 56, 353–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, N.; Yang, H. A Network Analysis of Body Image Concern, Interoceptive Sensibility, Self-consciousness, and Self-objectification. J. Clin. Psychol. 2024, 80, 2247–2267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.A.; Vanzhula, I.A.; Reilly, E.E.; Levinson, C.A.; Berner, L.A.; Krueger, A.; Lavender, J.M.; Kaye, W.H.; Wierenga, C.E. Body Mistrust Bridges Interoceptive Awareness and Eating Disorder Symptoms. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2020, 129, 445–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piper, M.A.; Charlton, R.A. Common and Unique Menopause Experiences among Autistic and Non-Autistic People: A Qualitative Study. J. Health Psychol. 2025, 13591053251316500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breheny, E.; O’Keeffe, F.; Cooney, S. Body Image, Sexual Dysfunction and Psychological Distress in People with Multiple Sclerosis. Disabil. Rehabil. 2025, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunne, J.; Flores, M.; Gawande, R.; Schuman-Olivier, Z. Losing Trust in Body Sensations: Interoceptive Awareness and Depression Symptom Severity among Primary Care Patients. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 282, 1210–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hielscher, E.; Zopf, R. Interoceptive Abnormalities and Suicidality: A Systematic Review. Behav. Ther. 2021, 52, 1035–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avis, N.E.; Crawford, S.L.; Greendale, G.; Bromberger, J.T.; Everson-Rose, S.A.; Gold, E.B.; Hess, R.; Joffe, H.; Kravitz, H.M.; Tepper, P.G.; et al. Duration of Menopausal Vasomotor Symptoms Over the Menopause Transition. JAMA Intern. Med. 2015, 175, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dillaway, H.E. (Un)Changing Menopausal Bodies: How Women Think and Act in the Face of a Reproductive Transition and Gendered Beauty Ideals. Sex Roles 2005, 53, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyde, A.; Nee, J.; Howlett, E.; Drennan, J.; Butler, M. Menopause Narratives: The Interplay of Women’s Embodied Experiences With Biomedical Discourses. Qual. Health Res. 2010, 20, 805–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, H.; Kotera, Y. Menopause and Body Image: The Protective Effect of Self-Compassion and Mediating Role of Mental Distress. Br. J. Guid. Couns. 2022, 50, 321–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangadharan, S.; Arulappan, J.; Matua, G.A.; Bhagavathy, M.G.; Alrahbi, H. Effectiveness of Yoga on Menopausal Symptoms and Quality of Life among Menopausal Women: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Nutr. Pharmacol. Neurol. Dis. 2024, 14, 300–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, J. Interoception: Where Do We Go from Here? Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 2024, 77, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Subscale | Definition |

|---|---|

| Noticing | Awareness of both neutral and affectively charged body sensations. |

| Not-Distracting | Tendency not to ignore or distract oneself from sensations of discomfort or pain. |

| Not-Worrying | Tendency not to experience distress or worry when perceiving discomfort or pain. |

| Attention Regulation | Ability to sustain and control attention directed toward body sensations. |

| Emotional Awareness | Recognition of the link between body sensations and emotional states. |

| Self-Regulation | Using attention to body sensations to regulate distress or emotions. |

| Body Listening | Actively attending to the body for insight and guidance. |

| Trusting | Experiencing one’s body as safe, trustworthy, and reliable. |

| Subscale | Items |

|---|---|

| Somatic symptoms | 1. Hot flushes, sweating (vasomotor symptoms) 2. Heart discomfort (e.g., awareness of heartbeat, heart skipping, tightness) 3. Sleep problems (difficulty falling or staying asleep, waking too early) 4. Joint and muscular discomfort (pain in joints, stiffness, muscle pain) |

| Psychological symptoms Urogenital symptoms |

5. Depressive mood (feeling down, sad, lack of drive, mood swings) 6. Irritability (feeling nervous, inner tension, aggressive) 7. Anxiety (inner restlessness, panicky feelings) 8. Physical and mental exhaustion (decrease in performance, impaired memory, concentration difficulties, forgetfulness) 9. Sexual problems (change in sexual desire, activity, satisfaction) 10. Bladder problems (difficulty in urination, increased frequency, incontinence) 11. Vaginal dryness (dryness or burning in the vagina, difficulty with sexual intercourse) |

| Variable | Mean | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 50.4 (5.06) | NA |

| Body Appreciation | 33.49 (7.62) | 0.93 |

| Body Image State Scale | 27.97 (9.41) | 0.76 |

| MAIA2: Noticing | 3.68 (0.91) | 0.76 |

| MAIA2: Not Distracting | 1.76 (0.98) | 0.89 |

| MAIA2: Not Worrying | 2.57 (0.85) | 0.69 |

| MAIA2: Attention Regulation | 2.53 (0.91) | 0.89 |

| MAIA2: Emotional Awareness | 3.59 (0.91) | 0.84 |

| MAIA2: Self-regulation | 2.68 (1.11) | 0.89 |

| MAIA2: Listening | 2.06 (1.21) | 0.90 |

| MAIA2: Trusting | 2.93 (1.14) | 0.89 |

| MRS: Somatic | 5.53 (3.08) | 0.70 |

| MRS: Urogenital | 4.31 (2.73) | 0.71 |

| MRS: Psychological | 6.62 (3.52) | 0.87 |

| Psychological Symptoms |

Somatic Symptoms |

Urogenital Symptoms |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| HRT user | |||

| 6.611 (3.115) | 7.944 (3.254) | 5.097 (2.660) | |

| Non-HRT USER | 4.979 (2.926) | 5.950 (3.473) | 3.091(2.684) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).