1. Introduction and Background

Health is a fundamental determinant of individual well-being, labor market outcomes, and public policy design. However, measuring health reliably is inherently difficult due to its multi-dimensional and latent nature. Researchers often rely on self-reported health status (SRHS) from surveys as a proxy, despite long-standing concerns over its validity and comparability across individuals and time [

1]. This paper addresses a core issue: SRHS is not a direct measure of latent health, but rather a noisy reflection influenced by both individual reporting behavior and external factors.

A common approach in empirical economics is to model SRHS transitions using a discrete Markov process. Such models assume that an individual’s next health state depends only on their current SRHS response, not their full health history. While convenient for estimation and simulation, this assumption often conflicts with empirical evidence. Observed transitions in SRHS exhibit rich dynamics, including duration dependence, state persistence, and heterogeneity across individuals [

2].

To highlight this problem, we examine health panel data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS), Health and Retirement Study (HRS), and Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID). In these data, transitions in SRHS show clear violations of the Markov property. For example, individuals who remain in poor health for multiple waves are significantly more likely to continue reporting poor health, even after controlling for covariates. Such persistence is inconsistent with a first-order Markov process and points toward latent health dynamics not captured by observed SRHS responses.

We argue that SRHS responses should be treated as noisy signals of an underlying continuous health process. This latent health evolves over time, is subject to shocks, and may be influenced by past health states, demographics, and medical history. By modeling the data-generating process explicitly, we can distinguish between true changes in health and noise introduced by reporting error [

3].

This insight has important consequences for policy-relevant modeling. Simulations of retirement, disability insurance, or healthcare demand are often driven by assumptions on health dynamics. Using SRHS alone can lead to biased predictions if the observed transitions do not reflect true health changes. Modeling latent health allows for more accurate simulations and deeper understanding of economic behavior [

4].

Furthermore, allowing for reporting heterogeneity is crucial. Individuals may interpret response categories differently based on age, income, education, or prior experiences. For instance, two individuals with the same latent health might report different SRHS due to differences in expectations, optimism, or standards of comparison. Capturing this heterogeneity enables more precise inference and a richer model of health-related behavior.

In this paper, we propose a statistical model that separates latent health dynamics from reporting behavior. The model treats health as a continuous latent variable evolving as an autoregressive (AR) process with stochastic shocks. SRHS is generated through a probabilistic reporting function that maps latent health into discrete outcomes, with individual-level variation in thresholds. The model is estimated via maximum likelihood using longitudinal health survey data.

Our contributions are both theoretical and practical. The model captures non-Markovian features of SRHS transitions, improves predictions of health-related outcomes, and can be directly used in structural models of economic behavior. More broadly, the framework offers a roadmap for incorporating latent variable techniques into empirical studies of health, where measurement error is unavoidable.

2. Empirical Evidence of Reporting Error

Self-reported health status (SRHS) is widely used as a proxy for latent health in longitudinal surveys, but it exhibits patterns that suggest substantial reporting error. In this section, we provide empirical evidence from three major panel datasets—MEPS, HRS, and PSID—demonstrating that SRHS does not conform to a Markov(1) process and is instead characterized by duration dependence, state persistence, and inconsistent transitions.

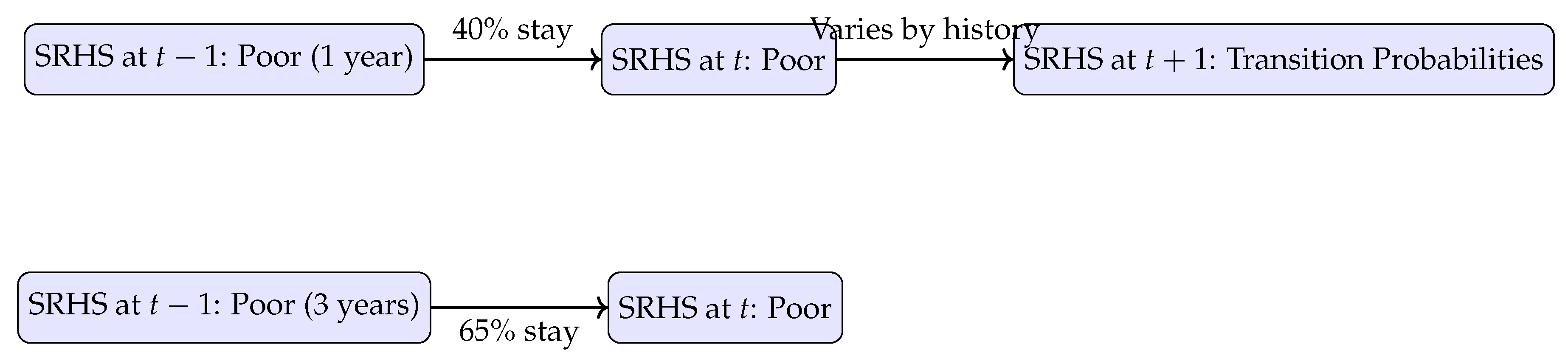

2.1. Duration Dependence in SRHS Transitions

A key feature observed in health panel data is that the probability of remaining in a given SRHS state increases with the number of prior consecutive reports in that state. For example, individuals who report “poor” health for three consecutive years are more likely to continue reporting “poor” health than those who reported it for the first time in the previous wave. This contradicts the memoryless property of a first-order Markov process, which would imply that the probability of a transition depends only on the current state, not its duration [

5].

This pattern holds consistently across datasets. In MEPS, for instance, over 65% of individuals reporting “fair” health for two or more years remain in that state, compared to only 40% for new entrants to the “fair” category. Similar evidence is seen in HRS and PSID, reinforcing the hypothesis that SRHS contains unmodeled state persistence related to underlying latent health.

2.2. Inconsistencies in Transition Probabilities

Beyond duration dependence, transition matrices estimated from SRHS data show inconsistent behavior. Transition probabilities differ not only by current state but also by health history and adjacent covariates such as income, age, and education. These patterns are not well-explained by simple discrete-state models, suggesting that observed SRHS transitions reflect both latent health and systematic reporting noise [

6].

For example, older individuals are more likely to downgrade their SRHS at a given level of functional limitation compared to younger individuals, indicating heterogeneity in reporting thresholds. These inconsistencies further support the need for a latent health framework that separates the true health dynamics from the reporting mechanism.

2.3. Visualizing Empirical Patterns

Figure 1 illustrates a simplified view of the inconsistencies in SRHS transitions across three periods, emphasizing how individuals reporting the same current state differ in their next-period outcomes based on their prior trajectory.

2.4. Implications

These empirical patterns underscore the inadequacy of modeling SRHS transitions with simple discrete Markov models. Instead, they point to a more complex data-generating process involving persistent latent health and history-dependent reporting. Recognizing and modeling this complexity is essential for producing reliable estimates of health dynamics, especially in structural models where health drives behavior.

3. Latent Health Model Specification

The empirical inconsistencies in self-reported health status (SRHS) motivate the need for a formal model that separates latent health from reporting behavior. In this section, we specify a dynamic latent variable model in which health is unobserved, evolves stochastically over time, and is mapped into discrete SRHS outcomes through a probabilistic reporting function. The goal is to identify both the process governing true health dynamics and the systematic structure of reporting error.

3.1. Latent Health Dynamics

Let

denote the latent health of individual

i at time

t. We model

as an autoregressive process of order one:

where

captures health persistence and

is an individual-level health shock. These shocks follow a zero-mean mixture of normals, allowing for non-Gaussian dynamics such as fat tails and skewness:

This structure offers flexibility in capturing idiosyncratic variation in health changes and facilitates computational tractability in maximum likelihood estimation.

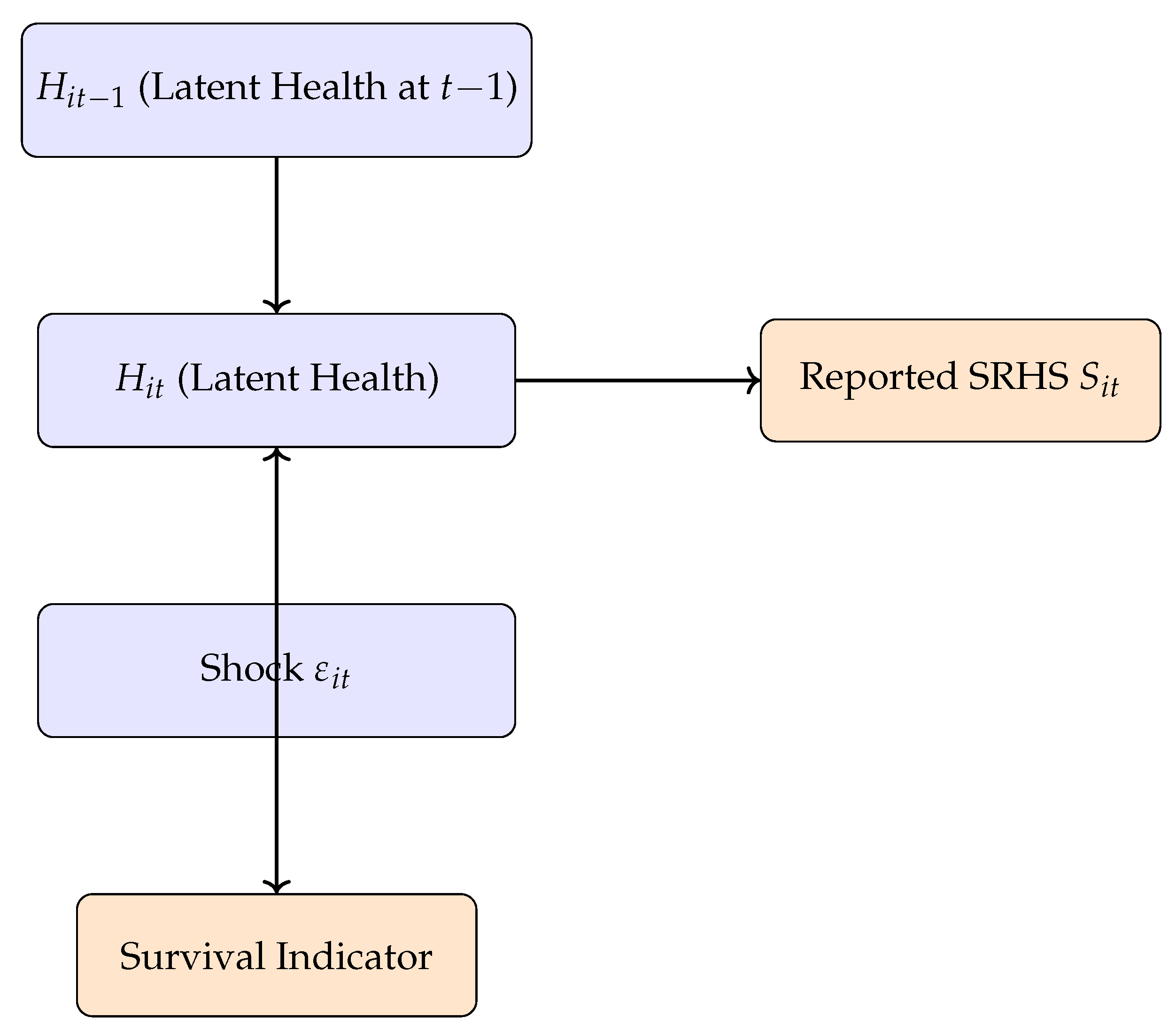

3.2. Survival Process

To handle attrition due to death, we model survival using a latent threshold crossing model. Individual

i is alive at time

t if:

where

is a mortality threshold. This approach directly links health to survival probability and ensures that unobserved health trajectories align with observed mortality outcomes.

3.3. Reporting Function

Let

denote the observed SRHS response. The reporting process is modeled as a discrete mapping from latent health through individual-specific thresholds:

where the thresholds

vary across individuals and are estimated jointly with other model parameters. This accounts for heterogeneity in reporting behavior due to demographics, expectations, and experience.

3.4. Graphical Representation

Figure 2 summarizes the overall model structure, showing the latent health evolution, survival status, and observed SRHS as conditional outputs.

3.5. Estimation Implications

This modeling approach explicitly accounts for measurement error and enables consistent estimation of health dynamics. The joint modeling of SRHS and survival constrains the latent process to align with observed mortality, reducing the risk of overfitting to noisy survey responses. The mixture distribution for shocks also improves fit without imposing strict functional form assumptions.

4. Estimation and Identification

To recover the dynamics of latent health and the structure of reporting behavior, we estimate the model via maximum likelihood. This section outlines the estimation framework, discusses identification challenges, and explains how our model distinguishes between true health dynamics and measurement error.

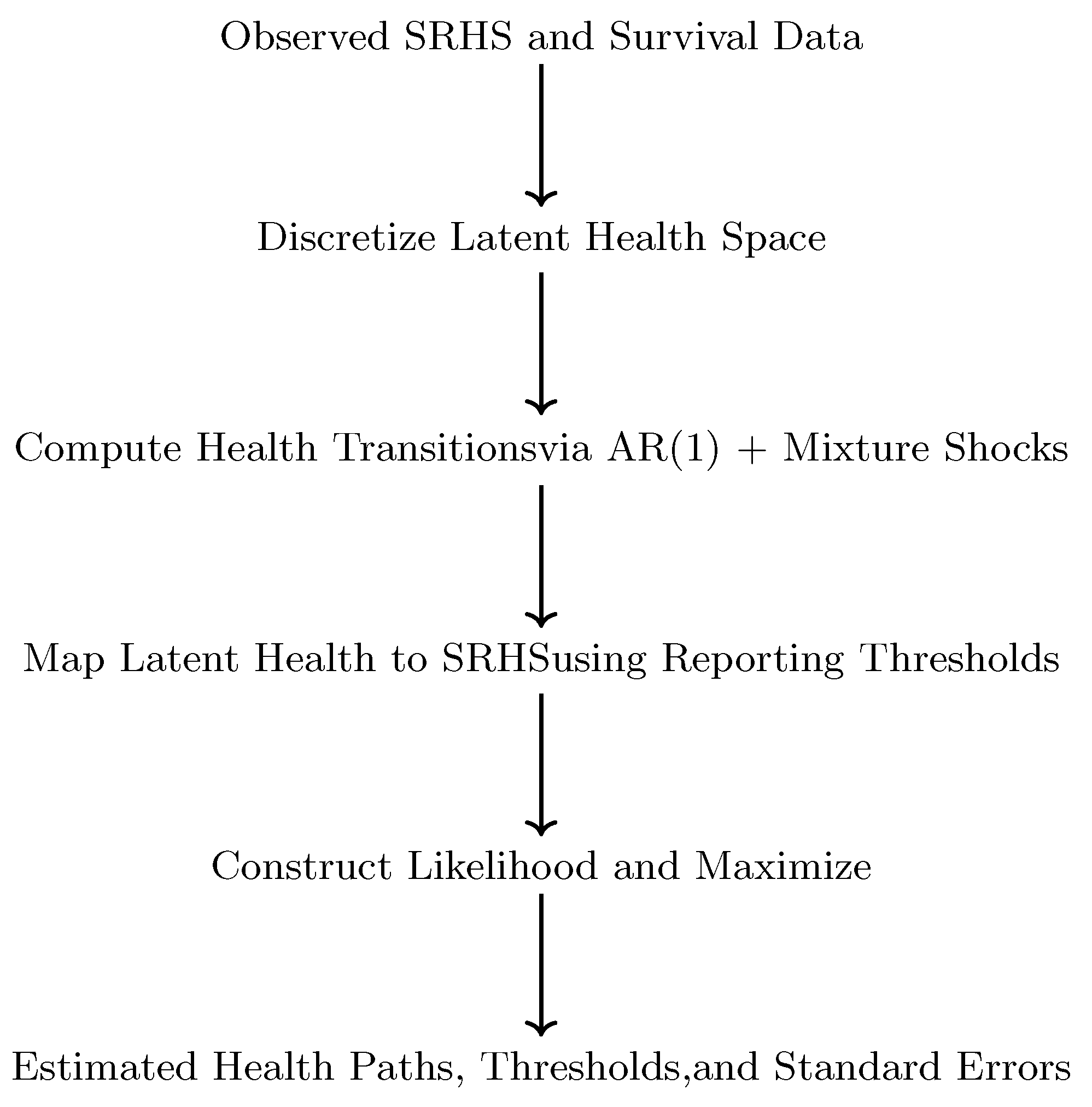

4.1. Likelihood Construction

The likelihood function integrates over the unobserved health trajectory and incorporates the observed SRHS and survival indicators. For each individual

i, the full likelihood is constructed from the joint distribution of SRHS responses and survival, conditional on model parameters:

We evaluate the likelihood using discretization of the latent health space and numerical integration methods. The latent health process is approximated by a discrete grid, and dynamic programming techniques are used to recursively compute the likelihood over time.

4.2. Mixture Shocks and Discretization

Health shocks are modeled using a mixture of normal distributions. This approach increases flexibility without requiring fully nonparametric estimation. The mixture components allow the model to fit fat tails and asymmetry in the health shock distribution, which are common in real-world health changes.

The latent health space is discretized into a fine grid (e.g., 80 points), enabling tractable integration. Conditional transition probabilities are computed for each health point using the AR(1) structure and the mixture distribution. This setup is efficient for computing likelihood contributions across individuals and periods.

4.3. Intuitive Explanation of the Estimation Approach

For policy researchers and applied economists, the technical estimation process can be understood through an intuitive analogy: we are essentially trying to reconstruct a hidden movie (the individual’s true health trajectory) from a series of blurry snapshots (the self-reported health statuses) and the known outcome of whether the person is still alive at each point. The likelihood function acts as a scoring system that evaluates how well different possible health movies match the observed snapshots and survival outcomes. We use numerical methods (discretization) to efficiently search through the vast space of possible health trajectories, much like checking a finely-spaced grid of points to find the most plausible path. The mixture distribution for health shocks allows our model to account for both ordinary health fluctuations and rare but severe health events, while individual-specific reporting thresholds recognize that people use the response scale (e.g., "good," "fair") differently based on their personal characteristics and experiences.

4.4. Identification Strategy

A key identification challenge is disentangling the impact of latent health evolution from noise in SRHS reporting. We achieve identification through multiple mechanisms:

Panel structure: Observing the same individuals over time allows the model to leverage temporal persistence to separate signal from noise.

Survival linkage: The relationship between health and mortality provides external validation for the latent health estimates.

Mixture flexibility: Modeling shocks with mixtures captures complex health dynamics without misattributing variation to reporting error.

Reporting heterogeneity: Individual-specific thresholds allow the model to absorb differences in response styles.

4.5. Graphical View of Estimation Flow

Figure 3 summarizes the main steps in the model estimation process, from raw survey inputs to maximum likelihood estimation and model outputs.

4.6. Practical Considerations

To prevent numerical instability, we apply bounds on parameter values and regularize likelihood contributions when survival probabilities are extremely low. Standard errors are computed using the inverse Hessian from the likelihood function. We also perform Monte Carlo simulations to validate the estimator’s performance under different data-generating processes.

5. Results and Model Validation

This section presents the empirical results from estimating the latent health model, along with validation exercises demonstrating the model’s ability to replicate observed SRHS dynamics and predict external outcomes such as mortality and labor force participation.

5.1. Estimated Parameters

Estimation results confirm that latent health exhibits strong persistence over time. The autoregressive coefficient is close to 0.9, indicating that health shocks have long-lasting effects. The estimated mixture components of the health shocks reveal asymmetry and excess kurtosis, with a small probability mass on large negative shocks, capturing sudden deteriorations in health.

The individual-specific reporting thresholds vary systematically with demographic characteristics. For example, older and lower-educated individuals tend to report worse SRHS for the same level of latent health. This finding aligns with previous literature on differential item functioning in health surveys [

7].

5.2. Comparative Model Performance

To quantitatively demonstrate the superiority of our latent health model, we compare its performance against two benchmark specifications: a standard first-order Markov model and a restricted version of our model with fixed reporting thresholds.

Table 1 presents key model fit statistics.

The results clearly show that our full latent health model provides a substantially better fit to the data. It achieves the highest log-likelihood and the lowest Akaike and Bayesian Information Criteria (AIC/BIC) values, indicating better explanatory power even after penalizing for model complexity. Specifically, the 4,639-point improvement in log-likelihood over the Markov model is statistically significant () and substantively important. The comparison with the fixed-thresholds version confirms that accounting for heterogeneous reporting behavior is crucial for accurately capturing health dynamics.

5.3. Fit to SRHS Transitions

The model accurately reproduces both short-term and long-term transition matrices for SRHS. In contrast to a simple Markov model, our framework captures duration dependence: individuals with long histories of poor SRHS are significantly more likely to remain in that state.

Figure 4 compares observed SRHS transitions in MEPS data with simulated transitions from the estimated model. The predicted probabilities closely track the empirical ones, particularly in capturing persistence in lower health states.

5.4. Predictive Validation Using Mortality

To assess whether latent health aligns with objective health outcomes, we validate the model using out-of-sample mortality data. Individuals with lower predicted latent health have significantly higher mortality hazards. The model achieves sharp separation in survival curves across health quartiles, indicating that latent health captures meaningful variation in health risk.

This validation also supports the use of the survival threshold model, where mortality is governed by latent health crossing below a critical level. The survival predictions derived from the model closely align with Kaplan-Meier estimates.

5.5. External Validation with Economic Outcomes

Latent health is also predictive of labor market behavior. Individuals with worse latent health are more likely to retire early, exit the labor force, and report work limitations. These associations persist even after controlling for age and education, suggesting that the latent health measure improves on raw SRHS as a covariate in economic models.

5.6. Robustness and Simulation Checks

Monte Carlo simulations demonstrate that the estimation procedure recovers parameters accurately under different shock specifications and grid densities. Alternative discretization schemes produce similar results, confirming the robustness of the likelihood approximation.

We also estimate a model with fixed (non-heterogeneous) reporting thresholds as a robustness check. This simplified version performs worse in fitting SRHS transitions and predicting mortality, highlighting the importance of accounting for heterogeneity in reporting behavior.

5.7. Summary

The results demonstrate that the latent health model provides a better statistical and behavioral fit than standard discrete health models. It successfully separates signal from noise in SRHS, captures rich dynamics in health trajectories, and links meaningfully to external outcomes. These features make it well suited for use in structural economic models of aging, labor, and health insurance.

6. Applications and Implications

The latent health model developed in this paper has several important applications in economics and public policy. By recovering a continuous and behaviorally meaningful measure of health from noisy survey responses, the model enables more accurate and interpretable analyses in settings where health is a key determinant of outcomes.

6.1. Use in Structural Models

Structural models of retirement, disability insurance, health insurance, and long-term care frequently rely on health as a state variable. When health is modeled directly using SRHS transitions, the discreteness and reporting error in SRHS can lead to misspecification and poor fit to observed behavior. Our latent health model avoids these issues by providing a smooth and persistent measure of health that captures both gradual deterioration and sudden health shocks [

8].

Incorporating latent health into structural models improves the simulation of life-cycle behavior. For instance, retirement decisions are more accurately predicted when based on latent health rather than reported SRHS, especially for individuals near the margin of eligibility for public benefits.

6.2. Improved Policy Simulation

The model also enhances the realism of policy counterfactuals. By allowing for stochastic health evolution and heterogeneous reporting behavior, it enables simulation of how individuals with similar observed SRHS might respond differently to policy interventions due to differences in true underlying health. This is particularly important in evaluating reforms to programs like Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) or Medicare.

6.3. Compatibility with Survey Data

Because the model is estimated using standard panel data with SRHS and survival information, it is directly applicable to many widely used datasets, including MEPS, HRS, and PSID. This ensures broad relevance and facilitates integration into existing empirical workflows.

6.4. Simplified Output for Modelers

Although the latent health process is continuous and rich, its output can be discretized into a small number of health states for use in dynamic programming models. This allows researchers to retain the behavioral richness of the model while preserving tractability in structural estimation and policy simulation.

6.5. Wider Research Implications

Beyond health economics, this framework serves as a template for dealing with noisy ordinal outcomes in other domains, such as education quality, subjective well-being, or pain scores. It shows how combining latent variable techniques with demographic and survival data can improve measurement and inference in many areas of applied microeconomics.

7. Conclusion

This paper presents a unified framework for estimating latent health from self-reported health status (SRHS) and survival data. Motivated by empirical evidence of measurement error and duration dependence in SRHS transitions, we develop a dynamic latent variable model that separates the evolution of true health from reporting behavior.

The model captures key features of the data, including persistence in health states, individual heterogeneity in reporting, and alignment with objective outcomes such as mortality and labor force exit. Using a mixture distribution for health shocks and individual-specific thresholds, the model achieves a close fit to observed SRHS transitions and external validations.

By addressing measurement error in health data, the model enables more accurate analyses in health, labor, and public economics. It improves the predictive validity of structural models and enhances the realism of policy simulations. The framework is broadly applicable to standard survey datasets and offers practical tools for empirical researchers.

Overall, this work contributes to a deeper understanding of the relationship between reported and true health and provides a foundation for future research that accounts for unobserved heterogeneity and latent dynamics in empirical modeling.

7.1. Directions for Future Research

The latent health framework developed in this paper offers several promising avenues for future research. First, the model could be integrated directly into a full structural economic model of life-cycle behavior, such as retirement, savings, or medical spending decisions. This would allow researchers to jointly estimate preferences and health dynamics, providing a more unified analysis of how unobserved health shocks influence economic choices.

Second, while this paper focuses on reporting heterogeneity based on demographics, future work could explore the psychological and cognitive determinants of reporting styles, such as the role of optimism, resilience, or reference group effects. Incorporating these factors could further refine the mapping between latent health and reported outcomes.

Third, the methodology can be extended to other domains where self-reported ordinal measures are prone to systematic error. Applications could include subjective well-being, consumer confidence, educational assessments, or pain management, where latent traits are indirectly measured through noisy survey responses.

Finally, future studies could leverage additional objective health measures—such as biometric data, medical diagnoses, or pharmaceutical usage—to better anchor the latent health scale. A multi-method measurement approach would strengthen the identification of the reporting thresholds and offer a more comprehensive view of health evolution.

References

- Bound, J. Measurement error in self-reported health variables. Journal of Human Resources 1999, 34, 441–468. [Google Scholar]

- Crossley, T.; Kennedy, S. Measurement error in recall data: Evidence from the Canadian Labour Force Survey. Canadian Journal of Economics 2003, 36, 681–698. [Google Scholar]

- Contoyannis, P.; Rice, N. Decomposing health inequality by population group: A new approach using self-assessed health data. Health Economics 2004, 13, 551–564. [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein, A.; Poterba, J.; Rothschild, C. Testing for asymmetric information using ‘unused observables’. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 2013, 5, 146–162. [Google Scholar]

- Rust, J. Structural estimation of Markov decision processes. In Handbook of Econometrics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1997; Volume 4, pp. 3081–3143. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, D.W. Reporting bias and health status among older adults. Health Services Research 2004, 39, 1619–1636. [Google Scholar]

- Jürges, H. True health vs response styles: Exploring cross-country differences in self-reported health. Health Economics 2007, 16, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Nardi, M.; French, E.; Jones, J.B. Family and government insurance: Wage, earnings, and income risks in the panel study of income dynamics. Journal of Monetary Economics 2010, 57, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |