Submitted:

18 December 2025

Posted:

19 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Background:

Main Text

1. Wastewater as a Mirror of Community Health and Sustainability:

2. Microbial Dynamics in Wastewater Treatment Plants:

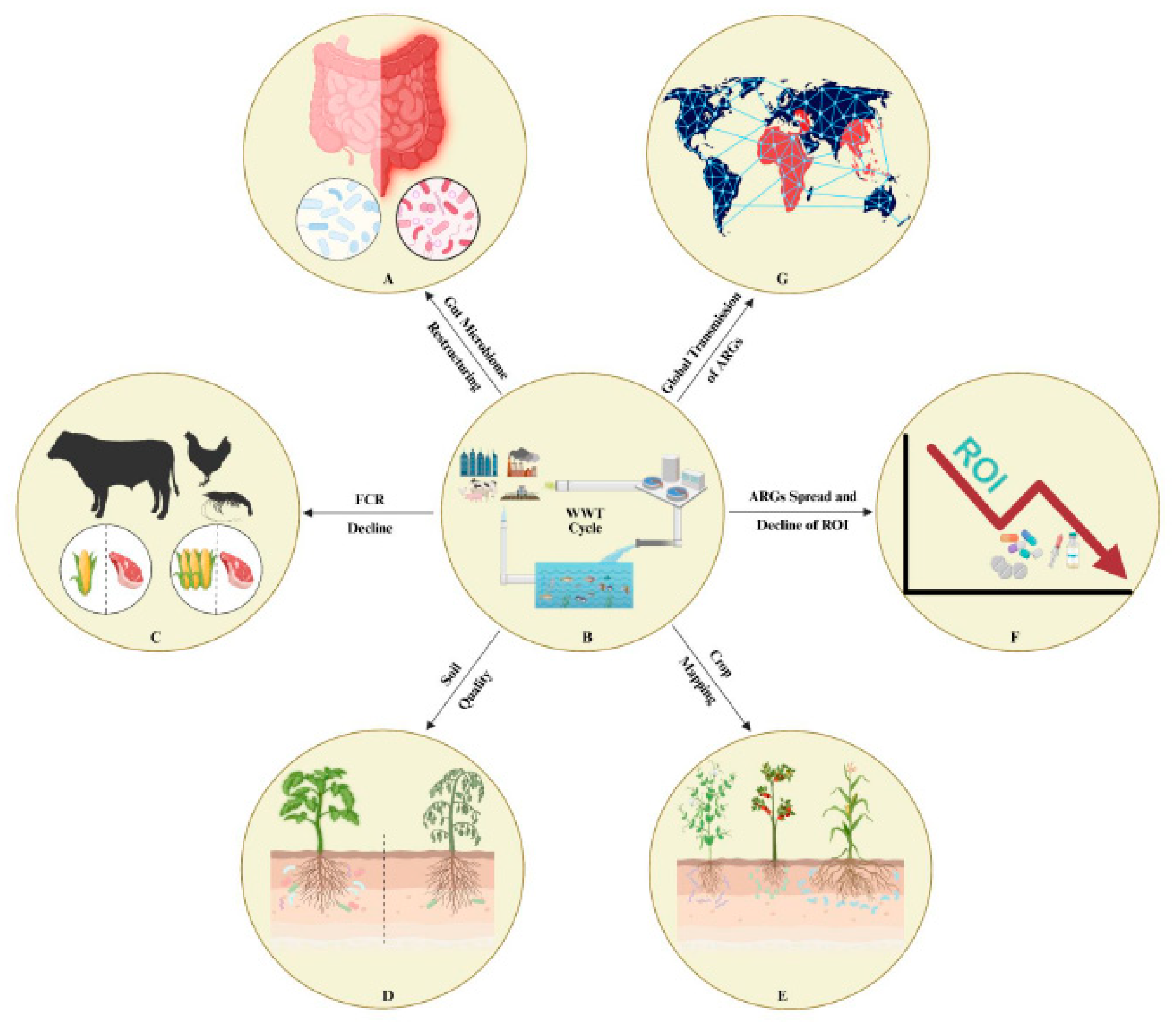

3. Impactful Overview of the Restructuring of Microbial Communities and ARGs:

3.1. Public Health Implications:

3.2. Economic Implications, Food Digestion Efficiency, Aquaculture, Soil

4. Approaches for Characterization of Wastewater Microbial Communities:

5. Water Scarcity as a Driver for Wastewater Treatment and Reuse:

6. Overview of Wastewater Treatment Processes and Effluent Quality:

7. Global Perspectives on Wastewater Treatment, Reuse, and Sustainable Management Strategies:

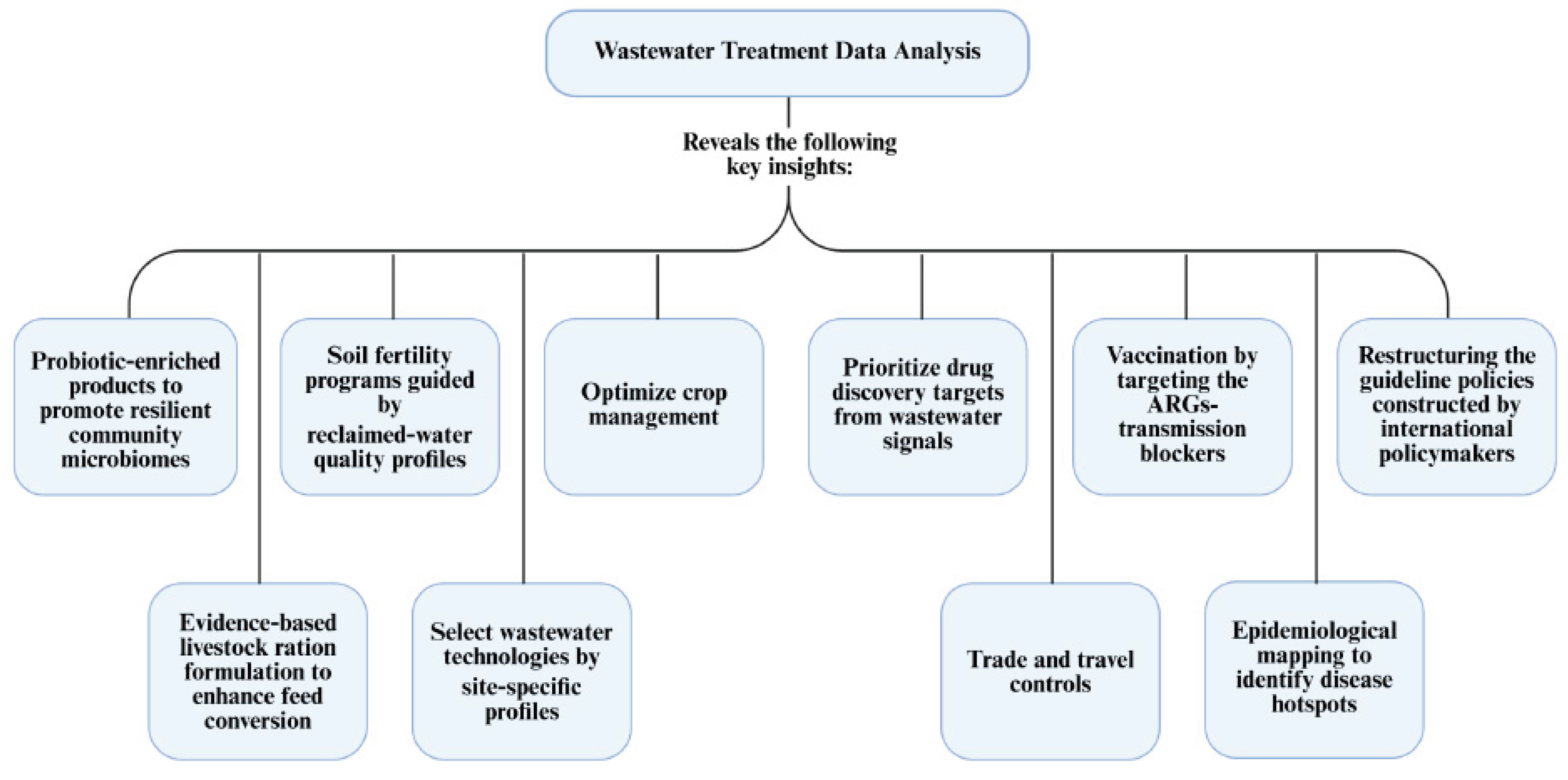

8. Actionable Strategies for Stakeholders and Application of Review Insights:

- Develop and implement probiotic-enriched products and evidence-based livestock feeding strategies to reinforce community microbiome resilience and improve feed conversion, reducing antibiotic reliance and resistance pressure.

- Establish site-specific, reclaimed-water quality–guided soil fertility programs and select locally optimized wastewater treatment technologies to safeguard agricultural productivity and environmental health.

- Prioritize crop management protocols that integrate microbiome and resistome surveillance, enabling adaptive, data-driven decision-making for yield and safety.

- Utilize wastewater signals for drug discovery prioritization as well as trade and travel control measures to intercept emerging resistance threats at both local and international levels.

- Initiate vaccination campaigns targeting key ARGs-transmission mechanisms and employ epidemiological mapping informed by wastewater data to identify disease hotspots and direct resources where most needed.

- Advocate for the restructuring and harmonization of guideline policies by international bodies, grounding regulatory frameworks in robust, real-world wastewater analytics to address the dynamic nature of resistance transmission and environmental change.

Conclusion:

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Consent for publication

List of abbreviations:

References

- Larsson, DGJ; Flach, CF. Antibiotic resistance in the environment. Nat Rev Microbiol 2022, 20, 257–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, DGJ; Flach, CF; Laxminarayan, R. Sewage surveillance of antibiotic resistance holds both opportunities and challenges. Nat Rev Microbiol 2023, 21, 213–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchobanoglus, G; Burton, F; Stensel, HD. Wastewater engineering: treatment and reuse. American Water Works Association Journal 2003, 95, 201. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo, L; Manaia, C; Merlin, C; Schwartz, T; Dagot, C; Ploy, MC; Michael, I; Fatta-Kassinos, D. Urban wastewater treatment plants as hotspots for antibiotic resistant bacteria and genes spread into the environment: A review. Science of The Total Environment 2013, 447, 345–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köck-Schulmeyer, M; Villagrasa, M; López de Alda, M; Céspedes-Sánchez, R; Ventura, F; Barceló, D. Occurrence and behavior of pesticides in wastewater treatment plants and their environmental impact. Science of The Total Environment 2013, 458–460, 466–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henze, M. Biological wastewater treatment : principles, modelling and design; IWA Pub, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Karkman, A; Do, TT; Walsh, F; Virta, MPJ. Antibiotic-Resistance Genes in Waste Water. Trends Microbiol 2018, 26, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wellington, EMH; Boxall, ABA; Cross, P; Feil, EJ; Gaze, WH; Hawkey, PM; Johnson-Rollings, AS; Jones, DL; Lee, NM; Otten, W; Thomas, CM; Williams, AP. The role of the natural environment in the emergence of antibiotic resistance in Gram-negative bacteria. Lancet Infect Dis 2013, 13, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Wintersdorff, CJH; Penders, J; Van Niekerk, JM; Mills, ND; Majumder, S; Van Alphen, LB; Savelkoul, PHM; Wolffs, PFG. Dissemination of antimicrobial resistance in microbial ecosystems through horizontal gene transfer. Front Microbiol 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarmah, AK; Meyer, MT; Boxall, ABA. A global perspective on the use, sales, exposure pathways, occurrence, fate and effects of veterinary antibiotics (VAs) in the environment. Chemosphere 2006, 65, 725–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Piernas, AB; Plaza-Bolaños, P; Agüera, A. Assessment of the presence of transformation products of pharmaceuticals in agricultural environments irrigated with reclaimed water by wide-scope LC-QTOF-MS suspect screening. J Hazard Mater 2021, 412, 125080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachmadi, AT; Azizkhan, ZM; Hong, P-Y. Enteric virus in reclaimed water from treatment plants with different multi-barrier strategies: Trade-off assessment in treatment extent and risks. Science of The Total Environment 2021, 776, 146039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solaiman, S; Micallef, SA. Aeromonas spp. diversity in U.S. mid-Atlantic surface and reclaimed water, seasonal dynamics, virulence gene patterns and attachment to lettuce. Science of The Total Environment 2021, 779, 146472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, JL. Environmental pollution by antibiotics and by antibiotic resistance determinants. Environmental Pollution 2009, 157, 2893–2902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berendonk, TU; Manaia, CM; Merlin, C; Fatta-Kassinos, D; Cytryn, E; Walsh, F; Bürgmann, H; Sørum, H; Norström, M; Pons, M-N; Kreuzinger, N; Huovinen, P; Stefani, S; Schwartz, T; Kisand, V; Baquero, F; Martinez, JL. Tackling antibiotic resistance: the environmental framework. Nat Rev Microbiol 2015, 13, 310–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manaia, CM; Rocha, J; Scaccia, N; Marano, R; Radu, E; Biancullo, F; Cerqueira, F; Fortunato, G; Iakovides, IC; Zammit, I; Kampouris, I; Vaz-Moreira, I; Nunes, OC. Antibiotic resistance in wastewater treatment plants: Tackling the black box. Environ Int 2018, 115, 312–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekizuka, T; Itokawa, K; Tanaka, R; Hashino, M; Yatsu, K; Kuroda, M. Metagenomic Analysis of Urban Wastewater Treatment Plant Effluents in Tokyo. Infect Drug Resist 2022, 15, 4763–4777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onalenna, O; Rahube, TO. Assessing bacterial diversity and antibiotic resistance dynamics in wastewater effluent-irrigated soil and vegetables in a microcosm setting. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huijbers, PMC; Flach, C-F; Larsson, DGJ. A conceptual framework for the environmental surveillance of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance. Environ Int 2019, 130, 104880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flach, C-F; Hutinel, M; Razavi, M; Åhrén, C; Larsson, DGJ. Monitoring of hospital sewage shows both promise and limitations as an early-warning system for carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales in a low-prevalence setting. Water Res 2021, 200, 117261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhm, M-E; Razavi, M; Marathe, NP; Flach, C-F; Larsson, DGJ. Discovery of a novel integron-borne aminoglycoside resistance gene present in clinical pathogens by screening environmental bacterial communities. Microbiome 2020, 8, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriksen, RS; Munk, P; Njage, P; van Bunnik, B; McNally, L; Lukjancenko, O; Röder, T; Nieuwenhuijse, D; Pedersen, SK; Kjeldgaard, J; Kaas, RS; Clausen, PTLC; Vogt, JK; Leekitcharoenphon, P; van de Schans, MGM; Zuidema, T; de Roda Husman, AM; Rasmussen, S; Petersen, B; Bego, A; Rees, C; Cassar, S; Coventry, K; Collignon, P; Allerberger, F; Rahube, TO; Oliveira, G; Ivanov, I; Vuthy, Y; Sopheak, T; Yost, CK; Ke, C; Zheng, H; Baisheng, L; Jiao, X; Donado-Godoy, P; Coulibaly, KJ; Jergović, M; Hrenovic, J; Karpíšková, R; Villacis, JE; Legesse, M; Eguale, T; Heikinheimo, A; Malania, L; Nitsche, A; Brinkmann, A; Saba, CKS; Kocsis, B; Solymosi, N; Thorsteinsdottir, TR; Hatha, AM; Alebouyeh, M; Morris, D; Cormican, M; O’Connor, L; Moran-Gilad, J; Alba, P; Battisti, A; Shakenova, Z; Kiiyukia, C; Ng’eno, E; Raka, L; Avsejenko, J; Bērziņš, A; Bartkevics, V; Penny, C; Rajandas, H; Parimannan, S; Haber, MV; Pal, P; Jeunen, G-J; Gemmell, N; Fashae, K; Holmstad, R; Hasan, R; Shakoor, S; Rojas, MLZ; Wasyl, D; Bosevska, G; Kochubovski, M; Radu, C; Gassama, A; Radosavljevic, V; Wuertz, S; Zuniga-Montanez, R; Tay, MYF; Gavačová, D; Pastuchova, K; Truska, P; Trkov, M; Esterhuyse, K; Keddy, K; Cerdà-Cuéllar, M; Pathirage, S; Norrgren, L; Örn, S; Larsson, DGJ; Heijden, T; Van der; Kumburu, HH; Sanneh, B; Bidjada, P; Njanpop-Lafourcade, B-M; Nikiema-Pessinaba. SC, Levent B, Meschke JS, Beck NK, Van CD, Phuc N Do, Tran DMN, Kwenda G, Tabo D, Wester AL, Cuadros-Orellana S, Amid C, Cochrane G, Sicheritz-Ponten T, Schmitt H, Alvarez JRM, Aidara-Kane A, Pamp SJ, Lund O, Hald T, Woolhouse M, Koopmans MP, Vigre H, Petersen TN, Aarestrup FM (2019) Global monitoring of antimicrobial resistance based on metagenomics analyses of urban sewage. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pärnänen, KMM; Narciso-da-Rocha, C; Kneis, D; Berendonk, TU; Cacace, D; Do, TT; Elpers, C; Fatta-Kassinos, D; Henriques, I; Jaeger, T; Karkman, A; Martinez, JL; Michael, SG; Michael-Kordatou, I; O’Sullivan, K; Rodriguez-Mozaz, S; Schwartz, T; Sheng, H; Sørum, H; Stedtfeld, RD; Tiedje, JM; Giustina, SV; Della; Walsh, F; Vaz-Moreira, I; Virta, M; Manaia, CM. Antibiotic resistance in European wastewater treatment plants mirrors the pattern of clinical antibiotic resistance prevalence. Sci Adv 2019, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, Y-K; Colque, P; Byfors, S; Giske, CG; Möllby, R; Kühn, I. Surveillance of antimicrobial resistance among Escherichia coli in wastewater in Stockholm during 1 year: does it reflect the resistance trends in the society? Int J Antimicrob Agents 2015, 45, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongprommoon, A; Chomkatekaew, C; Chewapreecha, C (). Monitoring pathogens in wastewater. Nat Rev Microbiol 2024, 22, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulia, V; Ait-Mouheb, N; Lesage, G; Hamelin, J; Wéry, N; Bru-Adan, V; Kechichian, L; Heran, M. Short-term effect of reclaimed wastewater quality gradient on soil microbiome during irrigation. Science of the Total Environment 2023, 901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partyka, ML; Bond, RF. Wastewater reuse for irrigation of produce: A review of research, regulations, and risks. Science of The Total Environment 2022, 828, 154385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, ER; van Vliet, MTH; Qadir, M; Bierkens, MFP. Country-level and gridded estimates of wastewater production, collection, treatment and reuse. Earth Syst Sci Data 2021, 13, 237–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ait-Mouheb, N; Mayaux, P-L; Mateo-Sagasta, J; Hartani, T; Molle, B. Water reuse: A resource for Mediterranean agriculture. In Water Resources in the Mediterranean Region; Elsevier, 2020; pp. pp 107–136. [Google Scholar]

- Shan, X; Liu, C; Song, L; Huan, H; Chen, H. Risk characteristics of resistome coalescence in irrigated soils and effect of natural storage of irrigation materials on risk mitigation. Environmental Pollution 2023, 338, 122575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brienza, M; Sauvêtre, A; Ait-Mouheb, N; Bru-Adan, V; Coviello, D; Lequette, K; Patureau, D; Chiron, S; Wéry, N. Reclaimed wastewater reuse in irrigation: Role of biofilms in the fate of antibiotics and spread of antimicrobial resistance. Water Res 2022, 221, 118830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatica, J. Cytryn E Impact of treated wastewater irrigation on antibiotic resistance in the soil microbiome. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2013, 20, 3529–3538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mola, M; Kougias, PG; Statiris, E; Papadopoulou, P; Malamis, S; Monokrousos, N. Short-term effect of reclaimed water irrigation on soil health, plant growth and the composition of soil microbial communities. Science of the Total Environment 2024, 949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G; Nagora, PR; Haksar, P; Chauhan, AR. Utilizing treated wastewater in tree plantation in Indian desert: part I – species suitability, plant growth and biomass production. Int J Phytoremediation 2022, 24, 1014–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campi, P; Navarro, A; Palumbo, AD; Modugno, F; Vitti, C; Mastrorilli, M. Energy of biomass sorghum irrigated with reclaimed wastewaters. European Journal of Agronomy 2016, 76, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Nahhal, Y; Tubail, K; Safi, M; Safi, J. Effect of Treated Waste Water Irrigation on Plant Growth and Soil Properties in Gaza Strip, Palestine. Am J Plant Sci 2013, 4, 1736–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad Rusan, MJ; Hinnawi, S; Rousan, L. Long term effect of wastewater irrigation of forage crops on soil and plant quality parameters. Desalination 2007, 215, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phogat, V; Mallants, D; Cox, JW; Šimůnek, J; Oliver, DP; Pitt, T; Petrie, PR. Impact of long-term recycled water irrigation on crop yield and soil chemical properties. Agric Water Manag 2020, 237, 106167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfanssi, S; Ouazzani, N; Mandi, L. Soil properties and agro-physiological responses of alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) irrigated by treated domestic wastewater. Agric Water Manag 2018, 202, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Hassena, A; Zouari, M; Trabelsi, L; Khabou, W; Zouari, N. Physiological improvements of young olive tree ( Olea europaea L. cv. Chetoui) under short term irrigation with treated wastewater. Agric Water Manag 2018, 207, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leogrande, R; Pedrero, F; Nicolas, E; Vitti, C; Lacolla, G; Stellacci, AM. Reclaimed Water Use in Agriculture: Effects on Soil Chemical and Biological Properties in a Long-Term Irrigated Citrus Farm. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GUO, W; Andersen, MN; QI, X; LI, P; LI, Z; FAN, X; ZHOU, Y. Effects of reclaimed water irrigation and nitrogen fertilization on the chemical properties and microbial community of soil. J Integr Agric 2017, 16, 679–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B; Cao, Y; Guan, X; Li, Y; Hao, Z; Hu, W; Chen, L. Microbial assessments of soil with a 40-year history of reclaimed wastewater irrigation. Science of The Total Environment 2019, 651, 696–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W; Lu, S; Pan, N; Wang, Y; Wu, L. Impact of reclaimed water irrigation on soil health in urban green areas. Chemosphere 2015, 119, 654–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, S; Wu, L; Wen, X; Wang, J; Chen, W. Effects of reclaimed wastewater irrigation on soil-crop systems in China: A review. Science of The Total Environment 2022, 813, 152531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berendonk, TU; Manaia, CM; Merlin, C; Fatta-Kassinos, D; Cytryn, E; Walsh, F; Bürgmann, H; Sørum, H; Norström, M; Pons, MN; Kreuzinger, N; Huovinen, P; Stefani, S; Schwartz, T; Kisand, V; Baquero, F; Martinez, JL. Tackling antibiotic resistance: The environmental framework. Nat Rev Microbiol 2015, 13, 310–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Mozaz, S; Chamorro, S; Marti, E; Huerta, B; Gros, M; Sànchez-Melsió, A; Borrego, CM; Barceló, D; Balcázar, JL. Occurrence of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance genes in hospital and urban wastewaters and their impact on the receiving river. Water Res 2015, 69, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J; Xu, Y; Wang, H; Guo, C; Qiu, H; He, Y; Zhang, Y; Li, X; Meng, W. Occurrence of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance genes in a sewage treatment plant and its effluent-receiving river. Chemosphere 2015, 119, 1379–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, L; Manaia, C; Merlin, C; Schwartz, T; Dagot, C; Ploy, MC; Michael, I; Fatta-Kassinos, D. Urban wastewater treatment plants as hotspots for antibiotic resistant bacteria and genes spread into the environment: a review. Sci Total Environ 2013, 447, 345–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, I; Rizzo, L; McArdell, CS; Manaia, CM; Merlin, C; Schwartz, T; Dagot, C; Fatta-Kassinos, D. Urban wastewater treatment plants as hotspots for the release of antibiotics in the environment: A review. Water Res 2013, 47, 957–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, T; Kohnen, W; Jansen, B; Obst, U. Detection of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and their resistance genes in wastewater, surface water, and drinking water biofilms. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 2003, 43, 325–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czekalski, N; Berthold, T; Caucci, S; Egli, A; Bürgmann, H. Increased Levels of Multiresistant Bacteria and Resistance Genes after Wastewater Treatment and Their Dissemination into Lake Geneva, Switzerland. Front Microbiol 2012, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novo, A; André, S; Viana, P; Nunes, OC; Manaia, CM. Antibiotic resistance, antimicrobial residues and bacterial community composition in urban wastewater. Water Res 2013, 47, 1875–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J; Li, J; Chen, H; Bond, PL; Yuan, Z. Metagenomic analysis reveals wastewater treatment plants as hotspots of antibiotic resistance genes and mobile genetic elements. Water Res 2017, 123, 468–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz-Moreira, I; Nunes, OC; Manaia, CM. Bacterial diversity and antibiotic resistance in water habitats: searching the links with the human microbiome. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2014, 38, 761–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tackling antibiotic resistance from a food safety perspective in Europe; World Health Organization, 2011.

- Ding, D; Wang, B; Zhang, X; Zhang, J; Zhang, H; Liu, X; Gao, Z; Yu, Z. The spread of antibiotic resistance to humans and potential protection strategies. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2023, 254, 114734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, G-G; He, L-Y; Ying, AJ; Zhang, Q-Q; Liu, Y-S; Zhao. J-L China Must Reduce Its Antibiotic Use. Environ Sci Technol 2017, 51, 1072–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S; Ahmed, AI; Almansoori, S; Alameri, S; Adlan, A; Odivilas, G; Chattaway, MA; Salem, S; Bin; Brudecki, G; Elamin, W. A narrative review of wastewater surveillance: pathogens of concern, applications, detection methods, and challenges. Front Public Health 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daughton, CG. Monitoring wastewater for assessing community health: Sewage Chemical-Information Mining (SCIM). Science of The Total Environment 2018, 2024(619–620), 748–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picó, Y; Barceló, D. Identification of biomarkers in wastewater-based epidemiology: Main approaches and analytical methods. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2021, 145, 116465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasprzyk-Hordern, B; Béen, F; Bijlsma, L; Brack, W; Castiglioni, S; Covaci, A; Martincigh, BS; Mueller, JF; van Nuijs, ALN; Oluseyi, T; Thomas, K V. Wastewater-based epidemiology for the assessment of population exposure to chemicals: The need for integration with human biomonitoring for global One Health actions. J Hazard Mater 2023, 450, 131009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L; Lin, X; Di, Z; Cheng, F; Xu, J. Occurrence, Risks, and Removal Methods of Antibiotics in Urban Wastewater Treatment Systems: A Review. Water (Basel) 2024, 16, 3428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, KS; Paul, D; Gupta, A; Dhotre, D; Klawonn, F; Shouche, Y. Indian sewage microbiome has unique community characteristics and potential for population-level disease predictions. Science of The Total Environment 2023, 858, 160178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriksen, RS; Munk, P; Njage, P; van Bunnik, B; McNally, L; Lukjancenko, O; Röder, T; Nieuwenhuijse, D; Pedersen, SK; Kjeldgaard, J; Kaas, RS; Clausen, PTLC; Vogt, JK; Leekitcharoenphon, P; van de Schans, MGM; Zuidema, T; de Roda Husman, AM; Rasmussen, S; Petersen, B; Bego, A; Rees, C; Cassar, S; Coventry, K; Collignon, P; Allerberger, F; Rahube, TO; Oliveira, G; Ivanov, I; Vuthy, Y; Sopheak, T; Yost, CK; Ke, C; Zheng, H; Baisheng, L; Jiao, X; Donado-Godoy, P; Coulibaly, KJ; Jergović, M; Hrenovic, J; Karpíšková, R; Villacis, JE; Legesse, M; Eguale, T; Heikinheimo, A; Malania, L; Nitsche, A; Brinkmann, A; Saba, CKS; Kocsis, B; Solymosi, N; Thorsteinsdottir, TR; Hatha, AM; Alebouyeh, M; Morris, D; Cormican, M; O’Connor, L; Moran-Gilad, J; Alba, P; Battisti, A; Shakenova, Z; Kiiyukia, C; Ng’eno, E; Raka, L; Avsejenko, J; Bērziņš, A; Bartkevics, V; Penny, C; Rajandas, H; Parimannan, S; Haber, MV; Pal, P; Jeunen, G-J; Gemmell, N; Fashae, K; Holmstad, R; Hasan, R; Shakoor, S; Rojas, MLZ; Wasyl, D; Bosevska, G; Kochubovski, M; Radu, C; Gassama, A; Radosavljevic, V; Wuertz, S; Zuniga-Montanez, R; Tay, MYF; Gavačová, D; Pastuchova, K; Truska, P; Trkov, M; Esterhuyse, K; Keddy, K; Cerdà-Cuéllar, M; Pathirage, S; Norrgren, L; Örn, S; Larsson, DGJ; Heijden, T; Van der; Kumburu, HH; Sanneh, B; Bidjada, P; Njanpop-Lafourcade, B-M; Nikiema-Pessinaba. SC, Levent B, Meschke JS, Beck NK, Van CD, Phuc N Do, Tran DMN, Kwenda G, Tabo D, Wester AL, Cuadros-Orellana S, Amid C, Cochrane G, Sicheritz-Ponten T, Schmitt H, Alvarez JRM, Aidara-Kane A, Pamp SJ, Lund O, Hald T, Woolhouse M, Koopmans MP, Vigre H, Petersen TN, Aarestrup FM Global monitoring of antimicrobial resistance based on metagenomics analyses of urban sewage. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X-T; Ye, L; Ju, F; Wang, Y-L; Zhang, T. Toward an Intensive Longitudinal Understanding of Activated Sludge Bacterial Assembly and Dynamics. Environ Sci Technol 2018, 52, 8224–8232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H; Ji, B; Zhang, S; Kong, Z. Study on the bacterial and archaeal community structure and diversity of activated sludge from three wastewater treatment plants. Mar Pollut Bull 2018, 135, 801–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L; Ning, D; Zhang, B; Li, Y; Zhang, P; Shan, X; Zhang, Q; Brown, MR; Li, Z; Van Nostrand, JD; Ling, F; Xiao, N; Zhang, Y; Vierheilig, J; Wells, GF; Yang, Y; Deng, Y; Tu, Q; Wang, A; Zhang, T; He, Z; Keller, J; Nielsen, PH; Alvarez, PJJ; Criddle, CS; Wagner, M; Tiedje, JM; He, Q; Curtis, TP; Stahl, DA; Alvarez-Cohen, L; Rittmann, BE; Wen, X; Zhou, J; Acevedo, D; Agullo-Barcelo, M; Alvarez, PJJ; Alvarez-Cohen, L; Andersen, GL; de Araujo, JC; Boehnke, KF; Bond, P; Bott, CB; Bovio, P; Brewster, RK; Bux, F; Cabezas, A; Cabrol, L; Chen, S; Criddle, CS; Deng, Y; Etchebehere, C; Ford, A; Frigon, D; Sanabria, J; Griffin, JS; Gu, AZ; Habagil, M; Hale, L; Hardeman, SD; Harmon, M; Horn, H; Hu, Z; Jauffur, S; Johnson, DR; Keller, J; Keucken, A; Kumari, S; Leal, CD; Lebrun, LA; Lee, J; Lee, M; Lee, ZMP; Li, Y; Li, Z; Li, M; Li, X; Liu, Y; Luthy, RG; Mendonça-Hagler, LC; de Menezes, FGR; Meyers, AJ; Mohebbi, A; Nielsen, PH; Ning, D; Oehmen, A; Palmer, A; Parameswaran, P; Park, J; Patsch, D; Reginatto, V; de los Reyes, FL; Rittmann, BE; Noyola, A; Rossetti, S; Shan, X; Sidhu, J; Sloan, WT; Smith, K; de Sousa, OV; Stahl, DA; Stephens, K; Tian, R; Tooker, NB; Tu, Q; Van Nostrand, JD; Vasconcelos, DD los C; Vierheilig, J; Wakelin, S; Wang, B; Weaver, JE; Wells, GF; West, S; Wilmes, P; Woo, SG; Wu, L; Wu, JH; Wu, L; Xi, C; Xiao, N; Xu, M; Yan, T; Yang, Y; Yang, M; Young, M; Yue, H; Zhang, B; Zhang, P; Zhang, Q; Zhang, Y; Zhang, T; Zhang, Q; Zhang, W. Zhang Y, Zhou H, Zhou J, Wen X, He Q, He Z, Brown MR. Global diversity and biogeography of bacterial communities in wastewater treatment plants. Nat Microbiol 2019, 4, 1183–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G; Yin, Q. Microbial niche nexus sustaining biological wastewater treatment. NPJ Clean Water 2020, 3, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y; Deng, Y; Wang, C; Li, S; Lau, FTK; Zhou, J; Zhang, T. Effects of operational parameters on bacterial communities in Hong Kong and global wastewater treatment plants. mSystems 2024, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marano, RBM; Cytryn, E. The Mobile Resistome in Wastewater Treatment Facilities and Downstream Environments. In Antimicrobial Resistance in Wastewater Treatment Processes; Wiley, 2017; pp. pp 129–155. [Google Scholar]

- Ju, F; Zhang, T. Bacterial assembly and temporal dynamics in activated sludge of a full-scale municipal wastewater treatment plant. ISME Journal 2015, 9, 683–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G; Bai, R; Zhang, Y; Zhao, B; Xiao, Y. Application of metagenomics to biological wastewater treatment. Science of The Total Environment 2022, 807, 150737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimbrel, JA; Ballor, N; Wu, YW; David, MM; Hazen, TC; Simmons, BA; Singer, SW; Jansson, JK. Microbial community structure and functional potential along a hypersaline gradient. Front Microbiol 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalf; Eddy, Inc. Wastewater Engineering: Treatment and Resource Recovery, 5th ed.; McGraw-Hill Education, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Manaia, CM; Rocha, J; Scaccia, N; Marano, R; Radu, E; Biancullo, F; Cerqueira, F; Fortunato, G; Iakovides, IC; Zammit, I; Kampouris, I; Vaz-Moreira, I; Nunes, OC. Antibiotic resistance in wastewater treatment plants: Tackling the black box. Environ Int 2018, 115, 312–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jutkina, J; Rutgersson, C; Flach, C-F; Joakim Larsson, DG. An assay for determining minimal concentrations of antibiotics that drive horizontal transfer of resistance. Science of The Total Environment 2016, 548–549, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, DE; Zitomer, DH; Hristova, KR; Kappell, AD; McNamara, PJ. Triclocarban Influences Antibiotic Resistance and Alters Anaerobic Digester Microbial Community Structure. Environ Sci Technol 2016, 50, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczepanowski, A; Kurz, R; Schneiker, N; Krahn, S.I. A Erythromycin Resistance-Conferring Plasmid pRSB105, Isolated from a Sewage Treatment Plant, Harbors a New Macrolide Resistance Determinant, an Integron-Containing Tn 402 -Like Element, and a Large Region of Unknown Function. Appl Environ Microbiol 2007, 73, 1952–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dröge, M; Pühler, A; Selbitschka, W. Phenotypic and molecular characterization of conjugative antibiotic resistance plasmids isolated from bacterial communities of activated sludge. Mol Gen Genet 2000, 263, 471–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyoum, MM; Lichtenberg, R; Orlofsky, E; Bernstein, N; Gillor, O. Antibiotic resistance in soil and tomato crop irrigated with freshwater and two types of treated wastewater. Environ Res 2022, 211, 113021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y; Neal, AL; Zhang, X; Fan, H; Liu, H; Li, Z. Cropping system exerts stronger influence on antibiotic resistance gene assemblages in greenhouse soils than reclaimed wastewater irrigation. J Hazard Mater 2022, 425, 128046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C; Li, J; Chen, P; Ding, R; Zhang, P; Li, X. Occurrence of antibiotics and antibiotic resistances in soils from wastewater irrigation areas in Beijing and Tianjin, China. Environmental Pollution 2014, 193, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F-H; Qiao, M; Lv, Z-E; Guo, G-X; Jia, Y; Su, Y-H; Zhu, Y-G. Impact of reclaimed water irrigation on antibiotic resistance in public parks, Beijing, China. Environmental Pollution 2014, 184, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y; Liu, C; Chen, H; Chen, J; Li, J; Teng, Y. Metagenomic insights into resistome coalescence in an urban sewage treatment plant-river system. Water Res 2022, 224, 119061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G; Guan, Y; Zhao, R; Feng, J; Huang, J; Ma, L; Li, B. Metagenomic and network analyses decipher profiles and co-occurrence patterns of antibiotic resistome and bacterial taxa in the reclaimed wastewater distribution system. J Hazard Mater 2020, 400, 123170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C; Shan, X; Zhang, Y; Song, L; Chen, H. Microcosm experiments revealed resistome coalescence of sewage treatment plant effluents in river environment. Environmental Pollution 2023, 338, 122661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evoung Chandja, WB; Onanga, R; Mbehang Nguema, PP; Lendamba, RW; Mouanga-Ndzime, Y; Mavoungou, JF; Godreuil, S. Emergence of Antibiotic Residues and Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria in Hospital Wastewater: A Potential Route of Spread to African Streams and Rivers, a Review. Water (Switzerland) 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y; Shan, X; Liu, C; Chen, H. Microcosm experiments deciphered resistome coalescence, risks and source-sink relationship of antibiotic resistance in the soil irrigated with reclaimed water. J Hazard Mater 2025, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W; Lu, S; Pan, N; Wang, Y; Wu, L. Impact of reclaimed water irrigation on soil health in urban green areas. Chemosphere 2015, 119, 654–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, E; Fan, X; Li, Z; Liu, Y; Neal, AL; Hu, C; Gao, F. Variations in soil and plant-microbiome composition with different quality irrigation waters and biochar supplementation. Applied Soil Ecology 2019, 142, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Valverde, M; Aragonés, AM; Andújar, JAS; García, MDG; Martínez-Bueno, MJ; Fernández-Alba, AR. Long-term effects on the agroecosystem of using reclaimed water on commercial crops. Science of The Total Environment 2023, 859, 160462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y; Linville, JL; Urgun-Demirtas, M; Mintz, MM; Snyder, SW. An overview of biogas production and utilization at full-scale wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) in the United States: Challenges and opportunities towards energy-neutral WWTPs. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2015, 50, 346–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H; Yu, K; Duan, Y; Ning, Z; Li, B; He, L; Liu, C. Profiling microbial communities in a watershed undergoing intensive anthropogenic activities. Science of The Total Environment 2019, 647, 1137–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bej, S; Swain, S; Bishoyi, AK; Mandhata, CP; Sahoo, CR; Padhy, RN. Wastewater-Associated Infections: A Public Health Concern. Water Air Soil Pollut 2023, 234, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rath, S. Microbial Contamination of Drinking Water. In Water Pollution and Management Practices; Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2021; pp. pp 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Magana-Arachchi, DN; Wanigatunge, RP. Ubiquitous waterborne pathogens. In Waterborne Pathogens; Elsevier, 2020; pp. pp 15–42. [Google Scholar]

- Sheahan, M; Gould, CA; Neumann, JE; Kinney, PL; Hoffmann, S; Fant, C; Wang, X; Kolian, M. Examining the Relationship between Climate Change and Vibriosis in the United States: Projected Health and Economic Impacts for the 21st Century. Environ Health Perspect 2022, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aib, H; Parvez, MS; Czédli, HM. Pharmaceuticals and Microplastics in Aquatic Environments: A Comprehensive Review of Pathways and Distribution, Toxicological and Ecological Effects. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2025, 22 . [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boro, D; Chirania, M; Verma, AK; Chettri, D; Verma, AK. Comprehensive approaches to managing emerging contaminants in wastewater: identification, sources, monitoring and remediation. Environ Monit Assess 2025, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garwal, Dilip; Srivastava, Bhawna; Reddy, P. B Ecotoxicological impacts of Microplastic (MP) Pollution in Fish. World Journal of Biology Pharmacy and Health Sciences 2025, 21, 628–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W; Bu, Q; Shi, Q; Zhao, R; Huang, H; Yang, L; Tang, J; Ma, Y. Emerging Contaminants in the Effluent of Wastewater Should Be Regulated: Which and to What Extent? Toxics 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Versporten, A; Bolokhovets, G; Ghazaryan, L; Abilova, V; Pyshnik, G; Spasojevic, T; Korinteli, I; Raka, L; Kambaralieva, B; Cizmovic, L; Carp, A; Radonjic, V; Maqsudova, N; Celik, HD; Payerl-Pal, M; Pedersen, HB; Sautenkova, N; Goossens, H. Antibiotic use in eastern Europe: a cross-national database study in coordination with the WHO Regional Office for Europe. Lancet Infect Dis 2014, 14, 381–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruden, A; Larsson, DGJ; Amézquita, A; Collignon, P; Brandt, KK; Graham, DW; Lazorchak, JM; Suzuki, S; Silley, P; Snape, JR; Topp, E; Zhang, T; Zhu. Y-G Management Options for Reducing the Release of Antibiotics and Antibiotic Resistance Genes to the Environment. Environ Health Perspect 2013, 121, 878–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, JH. Genetic Drift in an Infinite Population: The Pseudohitchhiking Model. Genetics 2000, 155, 909–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acar Kirit, H; Lagator, M; Bollback, JP. Experimental determination of evolutionary barriers to horizontal gene transfer. BMC Microbiol 2020, 20, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y-G; Zhao, Y; Zhu, D; Gillings, M; Penuelas, J; Ok, YS; Capon, A; Banwart, S. Soil biota, antimicrobial resistance and planetary health. Environ Int 2019, 131, 105059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, DGJ. Flach C-F Antibiotic resistance in the environment. Nat Rev Microbiol 2022, 20, 257–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y; Chen, H; Liu, C; Wang, R; Zhang, Z. Effects and mechanisms of reclaimed water irrigation and tillage treatment on the propagation of antibiotic resistome in soil. Science of the Total Environment 2025, 968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, WEH; Zechmeister-Boltenstern, S; Keiblinger, KM. Does soil contribute to the human gut microbiome? Microorganisms 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munck, C; Albertsen, M; Telke, A; Ellabaan, M; Nielsen, PH; Sommer, MOA. Limited dissemination of the wastewater treatment plant core resistome. Nat Commun 2015, 6, 8452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutton, G; Varughese, M. The Costs of Meeting the 2030 Sustainable Development Goal Targets on Drinking Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene; World Bank: Washington, DC, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Antimicrobial resistance; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lood, R; Ertürk, G; Mattiasson, B. Revisiting Antibiotic Resistance Spreading in Wastewater Treatment Plants – Bacteriophages as a Much Neglected Potential Transmission Vehicle. Front Microbiol 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, F; Li, B; Ma, L; Wang, Y; Huang, D; Zhang, T. Antibiotic resistance genes and human bacterial pathogens: Co-occurrence, removal, and enrichment in municipal sewage sludge digesters. Water Res 2016, 91, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J; Li, J; Chen, H; Bond, PL; Yuan, Z. Metagenomic analysis reveals wastewater treatment plants as hotspots of antibiotic resistance genes and mobile genetic elements. Water Res 2017, 123, 468–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahrenfeld, N; Ma, Y; O’Brien, M; Pruden, A. Reclaimed water as a reservoir of antibiotic resistance genes: distribution system and irrigation implications. Front Microbiol 2013, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Center for Global Development. Forecasting the Fallout from AMR: Economic Impacts of Antimicrobial Resistance in Humans. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Pires, L; Gonzalez-Paramás, AM; Heleno, SA; Calhelha, RC. Gut Microbiota as an Endocrine Organ: Unveiling Its Role in Human Physiology and Health. Applied Sciences (Switzerland) 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindell, AE; Zimmermann-Kogadeeva, M; Patil, KR. Multimodal interactions of drugs, natural compounds and pollutants with the gut microbiota. Nat Rev Microbiol 2022, 20, 431–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y; Pedersen, O. Gut microbiota in human metabolic health and disease. Nat Rev Microbiol 2021, 19, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, TC; Olson, CA; Hsiao, EY. Interactions between the microbiota, immune and nervous systems in health and disease. Nat Neurosci 2017, 20, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, L V.; Littman, DR; Macpherson, AJ. Interactions Between the Microbiota and the Immune System. Science (1979) 2012, 336, 1268–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamada, N; Chen, GY; Inohara, N; Núñez, G. Control of pathogens and pathobionts by the gut microbiota. Nat Immunol 2013, 14, 685–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijay, A; Valdes, AM. RETRACTED ARTICLE: Role of the gut microbiome in chronic diseases: a narrative review. Eur J Clin Nutr 2022, 76, 489–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carding, S; Verbeke, K; Vipond, DT; Corfe, BM; Owen, LJ. Dysbiosis of the gut microbiota in disease. Microb Ecol Health Dis 2015, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremlett, H; Bauer, KC; Appel-Cresswell, S; Finlay, BB; Waubant, E. The gut microbiome in human neurological disease: A review. Ann Neurol 2017, 81, 369–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, JA; Blaser, MJ; Caporaso, JG; Jansson, JK; Lynch, S V; Knight, R. Current understanding of the human microbiome. Nat Med 2018, 24, 392–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, XM; Hu, HW; Shi, XZ; Wang, JT; Han, LL; Chen, D; He, JZ. Impacts of reclaimed water irrigation on soil antibiotic resistome in urban parks of Victoria, Australia. Environmental Pollution 2016, 211, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michael, I; Rizzo, L; McArdell, CS; Manaia, CM; Merlin, C; Schwartz, T; Dagot, C; Fatta-Kassinos, D. Urban wastewater treatment plants as hotspots for the release of antibiotics in the environment: A review. Water Res 2013, 47, 957–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czekalski, N; Gascón Díez, E; Bürgmann, H. Wastewater as a point source of antibiotic-resistance genes in the sediment of a freshwater lake. ISME J 2014, 8, 1381–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, DGJ. Flach C-F Antibiotic resistance in the environment. Nat Rev Microbiol 2022, 20, 257–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huijbers, PMC; Flach, C-F; Larsson, DGJ. A conceptual framework for the environmental surveillance of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance. Environ Int 2019, 130, 104880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteiro, HF; Zhou, Z; Gomes, MS; Peixoto, PMG; Bonsaglia, ECR; Canisso, IF; Weimer, BC; Lima, FS. Rumen and lower gut microbiomes relationship with feed efficiency and production traits throughout the lactation of Holstein dairy cows. Sci Rep 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’hara, E; Neves, ALA; Song, Y; Guan, LL. The Role of the Gut Microbiome in Cattle Production and Health: Driver or Passenger. ? AV08CH09_Guan ARjats.cls 2025, 12, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L; Wu, P; Guo, A; Yang, Y; Chen, F; Zhang, Q. Research progress on the regulation of production traits by gastrointestinal microbiota in dairy cows. Front Vet Sci 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choct M Managing gut health through nutrition. Br Poult Sci 2009, 50, 9–15. [CrossRef]

- O’Hara, AM; Shanahan, F. The gut flora as a forgotten organ. EMBO Rep 2006, 7, 688–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S; Luo, S; Yan, C. Gut microbiota implications for health and welfare in farm animals: A review. Animals 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, EE; Stanley, D; Hughes, RJ; Moore, RJ. The time-course of broiler intestinal microbiota development after administration of cecal contents to incubating eggs. PeerJ 2017, 5, e3587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizrahi, I; Wallace, RJ; Moraïs, S. The rumen microbiome: balancing food security and environmental impacts. Nat Rev Microbiol 2021, 19, 553–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F; Li, C; Chen, Y; Liu, J; Zhang, C; Irving, B; Fitzsimmons, C; Plastow, G; Guan, LL. Host genetics influence the rumen microbiota and heritable rumen microbial features associate with feed efficiency in cattle. Microbiome 2019, 7, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eenennaam, AL. Addressing the 2050 demand for terrestrial animal source food. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2024, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laxminarayan, R; Duse, A; Wattal, C; Zaidi, AKM; Wertheim, HFL; Sumpradit, N; Vlieghe, E; Hara, GL; Gould, IM; Goossens, H; Greko, C; So, AD; Bigdeli, M; Tomson, G; Woodhouse, W; Ombaka, E; Peralta, AQ; Qamar, FN; Mir, F; Kariuki, S; Bhutta, ZA; Coates, A; Bergstrom, R; Wright, GD; Brown, ED. Cars O Antibiotic resistance-the need for global solutions. Lancet Infect Dis 2013, 13, 1057–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W; Wang, Z; Ling, H; Zheng, X; Chen, C; Wang, J; Cheng, Z. Effects of Reclaimed Water Irrigation on Soil Properties and the Composition and Diversity of Microbial Communities in Northwest China. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2025, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, P; Jingan, X; Liying, S. The effects of reclaimed water irrigation on the soil characteristics and microbial populations of plant rhizosphere. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2022, 29, 17570–17579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begmatov, S; Dorofeev, AG; Kadnikov, V V.; Beletsky, A V.; Pimenov, N V.; Ravin, N V.; Mardanov, A V. The structure of microbial communities of activated sludge of large-scale wastewater treatment plants in the city of Moscow. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 3458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yáñez-Ruiz, DR; Abecia, L; Newbold, CJ. Manipulating rumen microbiome and fermentation through interventions during early life: a review. Front Microbiol 2015, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozińska, A; Paździor, E; Pękala, A; Niemczuk, W. Acinetobacter johnsonii and Acinetobacter lwoffii - the emerging fish pathogens. Bulletin of the Veterinary Institute in Pulawy 2014, 58, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C; Qiu, S; Wang, Y; Qi, L; Hao, R; Liu, X; Shi, Y; Hu, X; An, D; Li, Z; Li, P; Wang, L; Cui, J; Wang, P; Huang, L; Klena, JD; Song, H. Higher Isolation of NDM-1 Producing Acinetobacter baumannii from the Sewage of the Hospitals in Beijing. PLoS One 2013, 8, e64857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y; Marrs, CF; Simon, C; Xi, C. Wastewater treatment contributes to selective increase of antibiotic resistance among Acinetobacter spp. Science of The Total Environment 2009, 407, 3702–3706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Church, NA; Mckillip, JL. Antibiotic resistance crisis: challenges and imperatives. Published. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Campion, EW; Morrissey, S. A Different Model — Medical Care in Cuba. New England Journal of Medicine 2013, 368, 297–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shade A Diversity is the question, not the answer. ISME J 2017, 11, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Kirk, JL; Beaudette, LA; Hart, M; Moutoglis, P; Klironomos, JN; Lee, H; Trevors, JT. Methods of studying soil microbial diversity. J Microbiol Methods 2004, 58, 169–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edet, U; Antai, S; Brooks, A; Asitok, A; Enya, O; Japhet, F. An Overview of Cultural, Molecular and Metagenomic Techniques in Description of Microbial Diversity. J Adv Microbiol 2017, 7, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X; Polz, MF; Alm, EJ. Interactions in self-assembled microbial communities saturate with diversity. ISME J 2019, 13, 1602–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y; Niu, Q; Zhang, X; Liu, L; Wang, Y; Chen, Y; Negi, M; Figeys, D; Li, Y-Y; Zhang, T. Exploring the effects of operational mode and microbial interactions on bacterial community assembly in a one-stage partial-nitritation anammox reactor using integrated multi-omics. Microbiome 2019, 7, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dueholm, MKD; Nierychlo, M; Andersen, KS; Rudkjøbing, V; Knutsson, S; Arriaga, S; Bakke, R; Boon, N; Bux, F; Christensson, M; Chua, ASM; Curtis, TP; Cytryn, E; Erijman, L; Etchebehere, C; Fatta-Kassinos, D; Frigon, D; Garcia-Chaves, MC; Gu, AZ; Horn, H; Jenkins, D; Kreuzinger, N; Kumari, S; Lanham, A; Law, Y; Leiknes, T; Morgenroth, E; Muszyński, A; Petrovski, S; Pijuan, M; Pillai, SB; Reis, MAM; Rong, Q; Rossetti, S; Seviour, R; Tooker, N; Vainio, P; van Loosdrecht, M; Vikraman, R; Wanner, J; Weissbrodt, D; Wen, X; Zhang, T; Nielsen, PH; Albertsen, M; Nielsen, PH. MiDAS 4, A global catalogue of full-length 16S rRNA gene sequences and taxonomy for studies of bacterial communities in wastewater treatment plants. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J; Zhu, Q; Zhang, T; Wu, Y; Zhang, Q; Fu, B; Fang, F; Feng, Q; Luo, J. Distribution patterns of microbial community and functional characteristics in full-scale wastewater treatment plants: Focusing on the influent types. Chemosphere 2021, 281, 130899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W; Wei, J; Su, Z; Wu, L; Liu, M; Huang, X; Yao, P; Wen, D. Deterministic mechanisms drive bacterial communities assembly in industrial wastewater treatment system. Environ Int 2022, 168, 107486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L; Wang, S; Xu, X; Zheng, J; Cai, T; Jia, S. Metagenomic analysis reveals the distribution, function, and bacterial hosts of degradation genes in activated sludge from industrial wastewater treatment plants. Environmental Pollution 2024, 340, 122802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrovski, S; Rice, DTF; Batinovic, S; Nittami, T; Seviour, RJ. The community compositions of three nitrogen removal wastewater treatment plants of different configurations in Victoria, Australia, over a 12-month operational period. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2020, 104, 9839–9852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J; Bu, Y; Zhang, X-X; Huang, K; He, X; Ye, L; Shan, Z; Ren, H. Metagenomic analysis of bacterial community composition and antibiotic resistance genes in a wastewater treatment plant and its receiving surface water. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2016, 132, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B; Ning, D; Van Nostrand, JD; Sun, C; Yang, Y; Zhou, J; Wen, X. Biogeography and Assembly of Microbial Communities in Wastewater Treatment Plants in China. Environ Sci Technol 2020, 54, 5884–5892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B; Yu, Q; Yan, G; Zhu, H; Xu, X; yang; Zhu, L. Seasonal bacterial community succession in four typical wastewater treatment plants: correlations between core microbes and process performance. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 4566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quince, C; Walker, AW; Simpson, JT; Loman, NJ; Segata, N. Shotgun metagenomics, from sampling to analysis. Nat Biotechnol 2017, 35, 833–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Numberger, D; Ganzert, L; Zoccarato, L; Mühldorfer, K; Sauer, S; Grossart, H-P; Greenwood, AD. Characterization of bacterial communities in wastewater with enhanced taxonomic resolution by full-length 16S rRNA sequencing. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 9673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oluseyi Osunmakinde, C; Selvarajan, R; Mamba, BB; Msagati, TAM. Profiling Bacterial Diversity and Potential Pathogens in Wastewater Treatment Plants Using High-Throughput Sequencing Analysis. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, I; Tyagi, K; Ahamad, F; Bhutiani, R; Kumar, V. Assessment of Bacterial Community Structure, Associated Functional Role, and Water Health in Full-Scale Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plants. Toxics 2025, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masrahi, AS. Effect of long-term influx of tertiary treated wastewater on native bacterial communities in a dry valley topsoil: 16S rRNA gene-based metagenomic analysis of composition and functional profile. PeerJ 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasir M Analysis of Microbial Communities and Pathogen Detection in Domestic Sewage Using Metagenomic Sequencing. Diversity (Basel) 2020, 13, 6. [CrossRef]

- Janda, JM; Abbott, SL. 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing for Bacterial Identification in the Diagnostic Laboratory: Pluses, Perils, and Pitfalls. J Clin Microbiol 2007, 45, 2761–2764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woese, CR; Kandler, O; Wheelis, ML. Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1990, 87, 4576–4579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abellan-Schneyder, I; Matchado, MS; Reitmeier, S; Sommer, A; Sewald, Z; Baumbach, J; List, M. Neuhaus K Primer, Pipelines, Parameters: Issues in 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing. mSphere 2021, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klindworth, A; Pruesse, E; Schweer, T; Peplies, J; Quast, C; Horn, M; Glöckner, FO. Evaluation of general 16S ribosomal RNA gene PCR primers for classical and next-generation sequencing-based diversity studies. Nucleic Acids Res 2013, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukin, YS; Galachyants, YP; Morozov, I V.; Bukin, S V.; Zakharenko, AS; Zemskaya, TI. The effect of 16s rRNA region choice on bacterial community metabarcoding results. Sci Data 2019, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, KJ; Saito, T; Silva, RS; Delforno, TP; Duarte, ICS; de Oliveira, VM; Okada, DY. Microbiome taxonomic and functional profiles of two domestic sewage treatment systems. Biodegradation 2021, 32, 17–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B; Lee, SH; Lee, J; Kim, NK; Kim, I; Park, S; Kim, S; Ham, SY; Park, HD; Im, D; Kim, HS. Influence of wastewater type on the distribution of microbial community compositions including pathogenic bacteria within wastewater treatment processes. Sustainable Environment Research 2025, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurvansuu, J; Länsivaara, A; Palmroth, M; Kaarela, O; Hyöty, H; Oikarinen, S; Lehto, KM. Machine learning-based identification of wastewater treatment plant-specific microbial indicators using 16S rRNA gene sequencing. Sci Rep 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Celis, M; Belda, I; Ortiz-Álvarez, R; Arregui, L; Marquina, D; Serrano, S; Santos, A. Tuning up microbiome analysis to monitor WWTPs’ biological reactors functioning. Sci Rep 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B; Wang, Y; Qian, PY. Sensitivity and correlation of hypervariable regions in 16S rRNA genes in phylogenetic analysis. BMC Bioinformatics 2016, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quast, C; Pruesse, E; Yilmaz, P; Gerken, J; Schweer, T; Yarza, P; Peplies, J; Glöckner, FO. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: Improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res 2013, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, BJ; Wong, J; Heiner, C; Oh, S; Theriot, CM; Gulati, AS; McGill, SK; Dougherty, MK. High-throughput amplicon sequencing of the full-length 16S rRNA gene with single-nucleotide resolution. Nucleic Acids Res 2019, 47, E103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdool Karim, Q; Abdool Karim, SS. Infectious diseases and the Sustainable Development Goals: progress, challenges and future directions. Nat Rev Microbiol 2023, 21, 626–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNGA. 70/1. Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development Preamble. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tortajada, C. Contributions of recycled wastewater to clean water and sanitation Sustainable Development Goals. NPJ Clean Water 2020, 3, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bain, R; Gundry, S; Wright, J; Yang, H; Pedley, S; Bartram, J. Accounting for water quality in monitoring access to safe drinking-water as part of the Millennium Development Goals: lessons from five countries. Bull World Health Organ 2012, 90, 228–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Juaidi, AE; Kaluarachchi, JJ; Mousa, AI. Hydrologic-Economic Model for Sustainable Water Resources Management in a Coastal Aquifer. J Hydrol Eng 2014, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, D; Arya, S; Kumar, S. Industrial wastewater treatment: Current trends, bottlenecks, and best practices. Chemosphere 2021, 285, 131245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, H; Gar Alalm, M; El-Etriby, HKh. Environmental and cost life cycle assessment of different alternatives for improvement of wastewater treatment plants in developing countries. Science of The Total Environment 2019, 660, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskar, A V.; Bolan, N; Hoang, SA; Sooriyakumar, P; Kumar, M; Singh, L; Jasemizad, T; Padhye, LP; Singh, G; Vinu, A; Sarkar, B; Kirkham, MB; Rinklebe, J; Wang, S; Wang, H; Balasubramanian, R; Siddique, KHM. Recovery, regeneration and sustainable management of spent adsorbents from wastewater treatment streams: A review. Science of The Total Environment 2022, 822, 153555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canaj, K; Mehmeti, A; Morrone, D; Toma, P; Todorović, M. Life cycle-based evaluation of environmental impacts and external costs of treated wastewater reuse for irrigation: A case study in southern Italy. J Clean Prod 2021, 293, 126142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, J; Chen, J; Wang, C; Fu, P. Wastewater reuse potential analysis: implications for China’s water resources management. Water Res 2004, 38, 2746–2756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capodaglio, AG. Fit-for-purpose urban wastewater reuse: Analysis of issues and available technologies for sustainable multiple barrier approaches. Crit Rev Environ Sci Technol 2021, 51, 1619–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chojnacka, K; Witek-Krowiak, A; Moustakas, K; Skrzypczak, D; Mikula, K; Loizidou, M. A transition from conventional irrigation to fertigation with reclaimed wastewater: Prospects and challenges. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2020, 130, 109959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debaere, P. D’Odorico P The Water Cycle, Climate Change, and (Some of) Their Interactions. SSRN Electronic Journal 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheripour, F; Tyner, WE; Sajedinia, E; Aguiar, A; Chepeliev, M; Corong, E; De Lima, CZ; Haqiqi, I. Water in the balance: the economic impacts of climate change and water scarcity in the Middle East. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO); FAO. Water. 2025. Available online: https://www.fao.org/land-water/water/en/ (accessed on 29 Aug 2025).

- Kaczan, D; Ward, J. Water statistics and poverty statistics in Africa: do they correlate at national scales? Water Int 2011, 36, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boretti, A; Rosa, L. Reassessing the projections of the World Water Development Report. NPJ Clean Water 2019, 2, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, R; van Koppen, B; Shah, T. Give to AgEcon Search.

- Redhu, S; Jain, P. Unveiling the nexus between water scarcity and socioeconomic development in the water-scarce countries. Environ Dev Sustain 2023, 26, 19557–19577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WWAP UNWWAP/ U-W. The United Nations World Water Development Report: Water for a Sustainable World. UNESCO, 2015. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000231823 (accessed on 25 Oct 2025).

- Van Bavel, JJ; Baicker, K; Boggio, PS; Capraro, V; Cichocka, A; Cikara, M; Crockett, MJ; Crum, AJ; Douglas, KM; Druckman, JN; Drury, J; Dube, O; Ellemers, N; Finkel, EJ; Fowler, JH; Gelfand, M; Han, S; Haslam, SA; Jetten, J; Kitayama, S; Mobbs, D; Napper, LE; Packer, DJ; Pennycook, G; Peters, E; Petty, RE; Rand, DG; Reicher, SD; Schnall, S; Shariff, A; Skitka, LJ; Smith, SS; Sunstein, CR; Tabri, N; Tucker, JA; Linden, S; van der; van Lange, P; Weeden, KA; Wohl, MJA; Zaki, J; Zion, SR; Willer, R. Using social and behavioural science to support COVID-19 pandemic response. Nat Hum Behav 2020, 4, 460–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta L Water and Human Development. World Dev 2014, 59, 59–69. [CrossRef]

- Anand, S. Sen A Human Development and Economic Sustainability. World Dev 2000, 28, 2029–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Water Governance for Poverty Reduction: Key Issues and the UNDP Response to Millennium Development Goals; UNDP, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF. Water, Sanitation and Hygiene. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Khawas V Human Development Report 2005-2006. Soc Change 2006, 36, 245–246. [CrossRef]

- Hutton, G; Varughese, M. The costs of meeting the 2030 sustainable development goal targets on drinking water, sanitation, and hygiene. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global Health Observatory (GHO) data: Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) access in health care facilities. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Educational S and CO (UNESCO). Education for all Global Monitoring Report 2012, Youth and Skills—Putting Education to Work; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kazianga, Hanan; Wahhaj, Zafiris. Water scarcity and child health: The role of women’s resource availability in rural Nepal. J Health Econ 2013, 32, 759–772. [Google Scholar]

- Dinesh Kumar, M; Shah, Z; Mukherjee, S; Mudgerikar, A. Water, human development and economic growth: some international perspectives; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kharraz, J; El; El-Sadek, A; Ghaffour, N; Mino, E. Water scarcity and drought in WANA countries. Procedia Eng 2012, 33, 14–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koolwal, G; van de Walle, D. Access to Water, Women’s Work, and Child Outcomes. Econ Dev Cult Change 2013, 61, 369–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duflo, E; Udry, C. Time spent collecting water and women’s productivity: Evidence from a water supply project in rural Zambia. Econ Dev Cult Change 2004, 52, 605–647. [Google Scholar]

- Sachs, JD; Schmidt-Traub, G; Mazzucato, M; Messner, D; Nakicenovic, N; Rockström, J. Six Transformations to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. Nat Sustain 2019, 2, 805–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damania, R; Desbureaux, S; Rodella, A-S; Russ, J; Zaveri, E. Quality Unknown: The Invisible Water Crisis; World Bank: Washington, DC, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Choudhuri, P; Desai, S. Lack of access to clean fuel and piped water and children’s educational outcomes in rural India. World Dev 2021, 145, 105535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, TP. Productive Benefits of Health: Evidence from Low-Income Countries. In Health and Economic Growth; The MIT Press, 2005; pp. pp 257–286. [Google Scholar]

- Duflo, E. Schooling and Labor Market Consequences of School Construction in Indonesia: Evidence from an Unusual Policy Experiment. American Economic Review 2001, 91, 795–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabr, M. Environmentally Friendly Wastewater Treatment in Egypt: Opportunities and Challenges. Journal of Engineering Research 2023, 7, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-Elaty, I; Abd-Elmoneem, SM; Abdelaal, GM; Vrána, J; Vranayová, Z; Abd-Elhamid, HF. Groundwater Quality Modeling and Mitigation from Wastewater Used in Irrigation, a Case Study of the Nile Delta Aquifer in Egypt. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19, 14929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atalla, AG; Ismail, EM; Abdelmalek, S. High-Resolution 16S rRNA and Metagenomics Reveal Taxonomic, Functional Restructuring and Pathogen Persistence in Egyptian Treated Wastewater. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Shalaby, EA. Prospects of effective microorganisms technology in wastes treatment in Egypt. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed 2011, 1, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayoub, M; Gar, I; Rashed, A-A; El-Morsy, A. Energy Production from Sewage Sludge in a Proposed Wastewater Treatment Plant. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkhazragy, ML; Matta, ME; Abdalla, KZ. Watershed Management, A Tool for Sustainable Safe Reuse Practice, Case Study: El-Salam Canal; 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahgoub, SA. Microbial Hazards in Treated Wastewater: Challenges and Opportunities for Their Reusing in Egypt 2018, pp 313–336.

- Zziwa, A; Matsapwe, D; Ssempira, EJ; Kizito, SS. Transforming Agriculture: Innovations in Sustainable Wastewater Reuse – A review. International Journal Of Scientific Advances 2023, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, OS; Hozayen, WG; Almutairi, AS; Edris, SA; Abulfaraj, AA; Ouf, AA; Mahmoud, HM. Metagenomic Analysis Reveals the Fate of Antibiotic Resistance Genes in a Full-Scale Wastewater Treatment Plant in Egypt. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Feky, AM; Saber, M; Abd-El-Kader, MM; Kantoush, SA; Sumi, T; Alfaisal, F. Abdelhaleem A Comprehensive environmental impact assessment and irrigation wastewater suitability of the Arab El-Madabegh wastewater treatment plant, Assiut City, Egypt. PLoS One 2024, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, P; Chandra, M; Fatima, N; Sarwar, S; Chaudhary, A; Saurabh, K; Yadav, BS. Predicting Influent and Effluent Quality Parameters for a UASB-Based Wastewater Treatment Plant in Asia Covering Data Variations during COVID-19, A Machine Learning Approach. Water (Switzerland) 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Englande, AJ; Krenkel, P; Shamas, J. Wastewater Treatment &Water Reclamation☆. In Reference Module in Earth Systems and Environmental Sciences; Elsevier, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Abualhaija, M. Applying the quality and pollution indices for evaluating the wastewater effluent quality of Kufranja wastewater treatment plant, Jordan. Water Conservation and Management 2023, 7, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osuolale, O; Okoh, A. Assessment of the physicochemical qualities and prevalence of Escherichia coli and vibrios in the final effluents of two wastewater treatment plants in South Africa: Ecological and public health implications. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2015, 12, 13399–13412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szklarek, S; Kiedrzyńska, E; Kiedrzyński, M; Mankiewicz-Boczek, J; Mitsch, WJ; Zalewski, M. Comparing ecotoxicological and physicochemical indicators of municipal wastewater effluent and river water quality in a Baltic Sea catchment in Poland. Ecol Indic 2021, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathya, K; Nagarajan, K; Carlin Geor Malar, G; Rajalakshmi, S; Raja Lakshmi, P. A comprehensive review on comparison among effluent treatment methods and modern methods of treatment of industrial wastewater effluent from different sources. Appl Water Sci 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atalla, AG; Ismail, EM; Tork, IM; Abdelmalek, S. Spatial Evaluation of Wastewater Treatment Efficacy in Five Egyptian Regions: Implications for Water Scarcity. Veterinary Medical Journal (Giza) 2025, 71, 126–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, J; Giurea, R; Bettinetti, R. Preliminary correlations between climate change and wastewater treatment plant parameters. WIT Transactions on Ecology and the Environment 2024, 262, 957–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of the European Communities. Council Directive 91/271/EEC of 21 May 1991 concerning urban waste-water treatment. 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Wastewater Treatment and Use in Agriculture. 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Egypt. Law No. 48 of 1982 concerning the protection of the Nile River and waterways from pollution and its Executive Regulations No. 92 of 2013 (Article 52). Egypt, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Osman, HEM; Abdel-Hamed, EMW; Al-Juhani, WSM; Al-Maroai, YAO; El-Morsy, MHE-M. Bioaccumulation and human health risk assessment of heavy metals in food crops irrigated with freshwater and treated wastewater: a case study in Southern Cairo, Egypt. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2021, 28, 50217–50229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmoud, MEM; Abd El-Razek, TAM; Abd El-Rahman, HS; Saad, MA. 2021) 50); Iss. (10); No. (4).

- Szczepanowski, R; Linke, B; Krahn, I; Gartemann, K-H; Gützkow, T; Eichler, W; Pühler, A; Schlüter, A. Detection of 140 clinically relevant antibiotic-resistance genes in the plasmid metagenome of wastewater treatment plant bacteria showing reduced susceptibility to selected antibiotics. Microbiology (N Y) 2009, 155, 2306–2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y; Marrs, CF; Simon, C; Xi, C. Wastewater treatment contributes to selective increase of antibiotic resistance among Acinetobacter spp. Science of The Total Environment 2009, 407, 3702–3706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guardabassi, L; Lo Fo Wong, DMA; Dalsgaard, A. The effects of tertiary wastewater treatment on the prevalence of antimicrobial resistant bacteria. Water Res 2002, 36, 1955–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novo, A; Manaia, CM. Factors influencing antibiotic resistance burden in municipal wastewater treatment plants. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2010, 87, 1157–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, JA. Wastewater Treatment and Reuse for Sustainable Water Resources Management: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanjra, MA; Blackwell, J; Carr, G; Zhang, F; Jackson, TM. Wastewater irrigation and environmental health: Implications for water governance and public policy. Int J Hyg Environ Health 2012, 215, 255–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, OA; Hsu, A; Johnson, LA; de Sherbinin. A A global indicator of wastewater treatment to inform the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Environ Sci Policy 2015, 48, 172–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odlare, M. Introductory Chapter for Water Resources. In Reference Module in Earth Systems and Environmental Sciences; Elsevier, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Carolin, CF; Kumar, PS; Saravanan, A; Joshiba, GJ. Naushad Mu Efficient techniques for the removal of toxic heavy metals from aquatic environment: A review. J Environ Chem Eng 2017, 5, 2782–2799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fito, J; Van Hulle, SWH. Wastewater reclamation and reuse potentials in agriculture: towards environmental sustainability. Environ Dev Sustain 2021, 23, 2949–2972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoatey, P; Bani, R. Wastewater management programs. Metal Finishing 2011, 100, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X; Chiang, P; Pan, S; Chen, G; Tao, Y; Wu, G; Wang, F; Cao, W. Systematic approach to evaluating environmental and ecological technologies for wastewater treatment. Chemosphere 2019, 218, 778–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Narvaez, OM; Peralta-Hernandez, JM; Goonetilleke, A; Bandala, ER. Treatment technologies for emerging contaminants in water: A review. Chemical Engineering Journal 2017, 323, 361–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paruch, AM; Mæhlum, T; Eltun, R; Tapu, E; Spinu, O. Green wastewater treatment technology for agritourism business in Romania. Ecol Eng 2019, 138, 133–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinos-Senante, M; Gómez, T; Caballero, R; Hernández-Sancho, F; Sala-Garrido, R. Assessment of wastewater treatment alternatives for small communities: An analytic network process approach. Science of The Total Environment 2015, 532, 676–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ponce-Robles, L; Oller, I; Polo-López, MI; Rivas-Ibáñez, G; Malato, S. Microbiological evaluation of combined advanced chemical-biological oxidation technologies for the treatment of cork boiling wastewater. Science of The Total Environment 2019, 687, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puyol, D; Batstone, DJ; Hülsen, T; Astals, S; Peces, M; Krömer, JO. Resource Recovery from Wastewater by Biological Technologies: Opportunities, Challenges, and Prospects. Front Microbiol 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawaf, MB; Al; Karaca, F. Different stakeholders’ opinions toward the sustainability of common textile wastewater treatment technologies in Turkey: A Case study Istanbul province. Sustain Cities Soc 2018, 42, 194–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Elsayed, N; Rezaei, N; Guo, T; Mohebbi, S; Zhang, Q. Wastewater-based resource recovery technologies across scale: A review. Resour Conserv Recycl 2019, 145, 94–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talvitie, J; Mikola, A; Koistinen, A; Setälä, O. Solutions to microplastic pollution – Removal of microplastics from wastewater effluent with advanced wastewater treatment technologies. Water Res 2017, 123, 401–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, S; Aydin, ME; Ulvi, A; Kilic, H. Antibiotics in hospital effluents: occurrence, contribution to urban wastewater, removal in a wastewater treatment plant, and environmental risk assessment. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2019, 26, 544–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalin, D; Craddock, HA; Assouline, S; Ben Mordechay, E; Ben-Gal, A; Bernstein, N; Chaudhry, RM; Chefetz, B; Fatta-Kassinos, D; Gawlik, BM; Hamilton, KA; Khalifa, L; Kisekka, I; Klapp, I; Korach-Rechtman, H; Kurtzman, D; Levy, GJ; Maffettone, R; Malato, S; Manaia, CM; Manoli, K; Moshe, OF; Rimelman, A; Rizzo, L; Sedlak, DL; Shnit-Orland, M; Shtull-Trauring, E; Tarchitzky, J; Welch-White, V; Williams, C; McLain, J. Cytryn E Mitigating risks and maximizing sustainability of treated wastewater reuse for irrigation. Water Res X 2023, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mañas, P; Castro, E; De Las Heras, J. Risks for Human Health of Using Wastewater for Turf Grass Irrigation. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Guidelines for the safe use of wastewater, excreta and greywater in agriculture and aquaculture; World Health Organization, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Shoushtarian, F; Negahban-Azar, M. World wide regulations and guidelines for agriculturalwater reuse: A critical review. Water (Switzerland) 2020, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Hashem, MS; Qi, X. Bin Treated wastewater irrigation-a review. Water (Switzerland) 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berbel, J; Mesa-Pérez, E; Simón, P. Challenges for Circular Economy under the EU 2020/741 Wastewater Reuse Regulation. Global Challenges 2023, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalin, D; Craddock, HA; Assouline, S; Ben Mordechay, E; Ben-Gal, A; Bernstein, N; Chaudhry, RM; Chefetz, B; Fatta-Kassinos, D; Gawlik, BM; Hamilton, KA; Khalifa, L; Kisekka, I; Klapp, I; Korach-Rechtman, H; Kurtzman, D; Levy, GJ; Maffettone, R; Malato, S; Manaia, CM; Manoli, K; Moshe, OF; Rimelman, A; Rizzo, L; Sedlak, DL; Shnit-Orland, M; Shtull-Trauring, E; Tarchitzky, J; Welch-White, V; Williams, C; McLain, J. Cytryn E Mitigating risks and maximizing sustainability of treated wastewater reuse for irrigation. Water Res X 2023, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J; Monnot, M; Ercolei, L; Moulin, P. Membrane-based processes used in municipal wastewater treatment for water reuse: State-of-the-art and performance analysis. Membranes (Basel) 2020, 10, 1–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra-Rodríguez, S; Oulego, P; Rodríguez, E; Singh, DN; Rodríguez-Chueca, J. Towards the implementation of circular economy in the wastewater sector: Challenges and opportunities. Water (Switzerland) 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duque, AF; Campo, R; Del Rio, AV; Amorim, CL. Wastewater valorization: Practice around the world at pilot-and full-scale. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18. [Google Scholar]

- IWA. 2025. Available online: https://www.iwa-network.org/news/iwa-launches-new-cluster-on-nature-based-solutions-for-climate-resilient-water-and-sanitation-management (accessed on 25 Oct 2025).

- UNEP. Wastewater - Turning Problem to Solution. 2023. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).