Submitted:

18 December 2025

Posted:

19 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

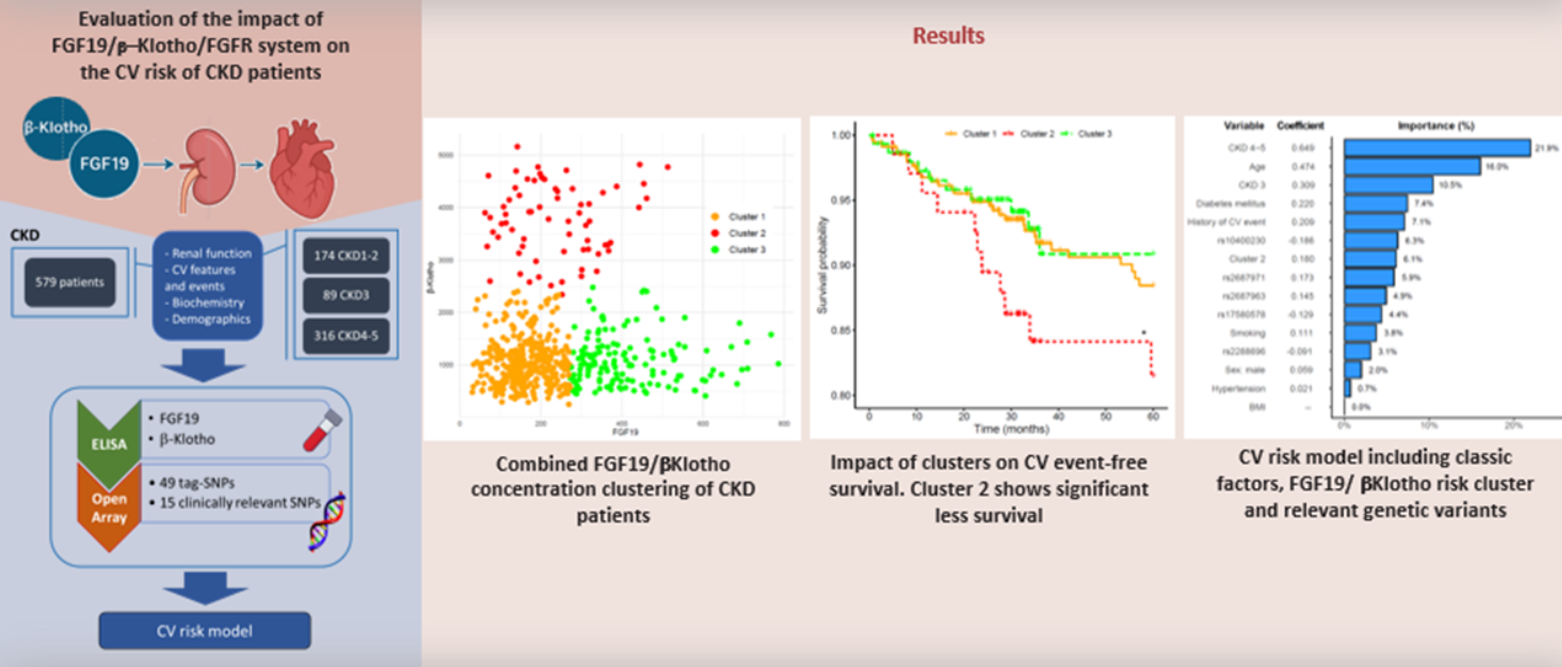

Abstract

Keywords:

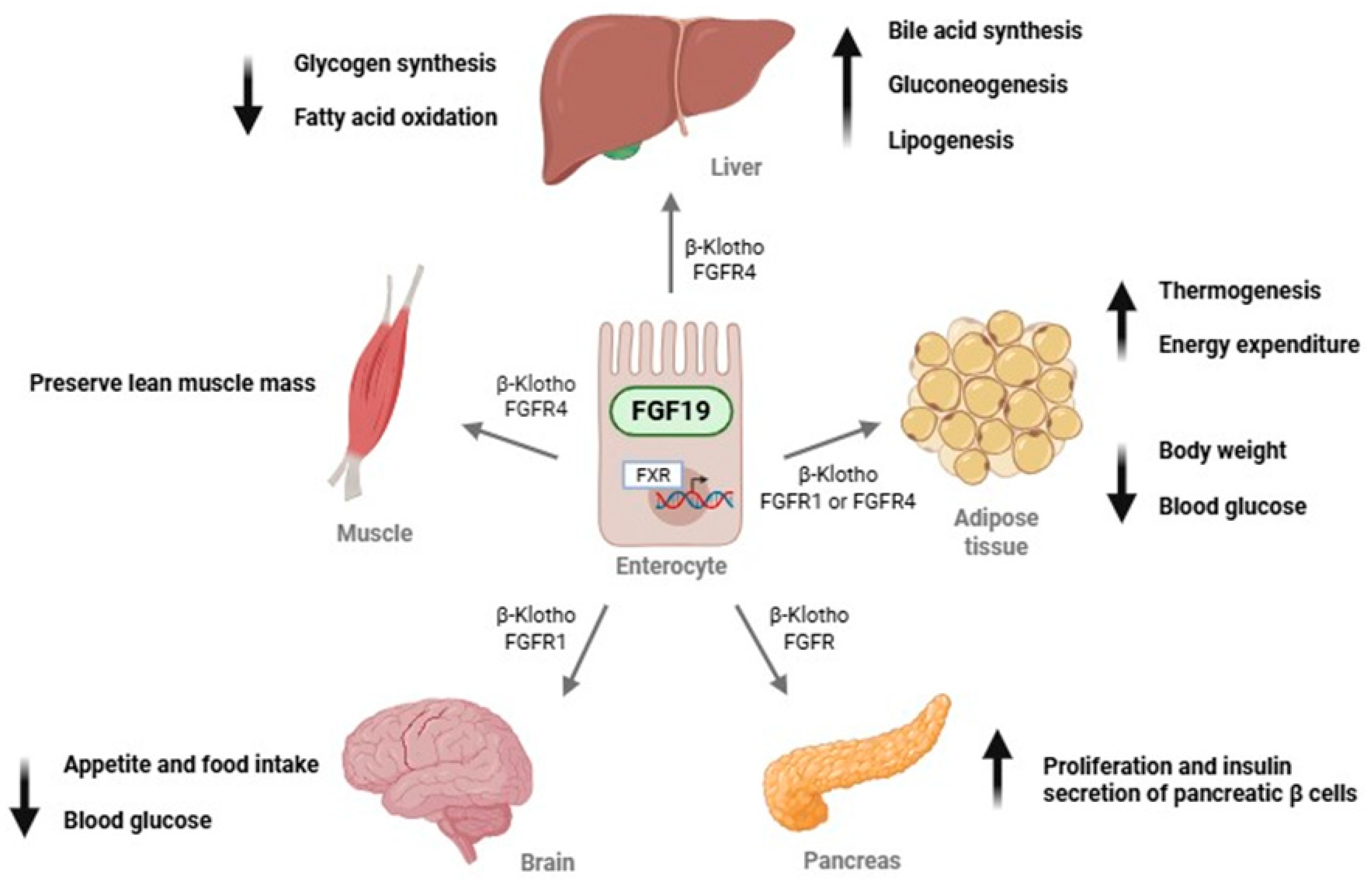

1. Introduction

2. Results

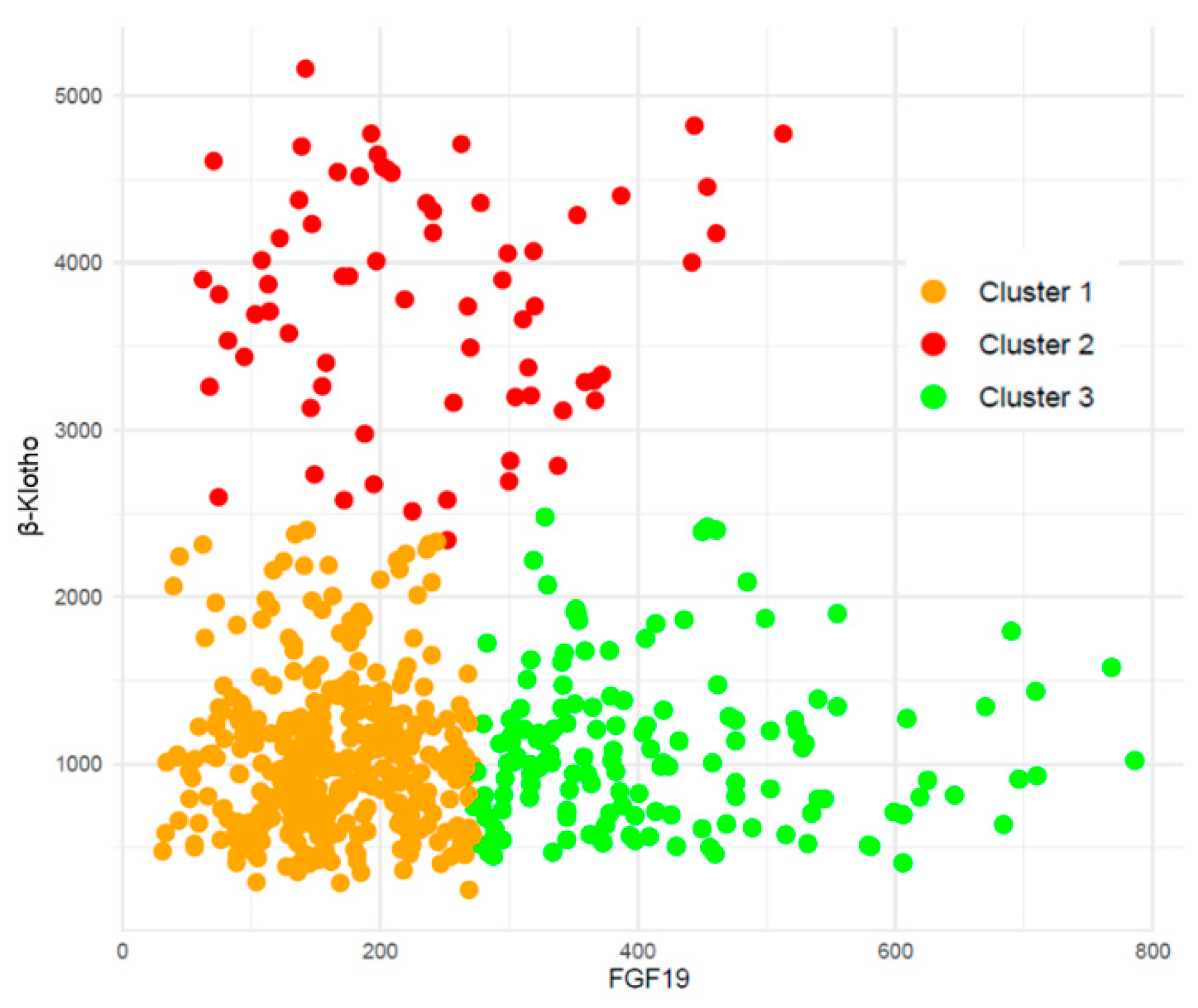

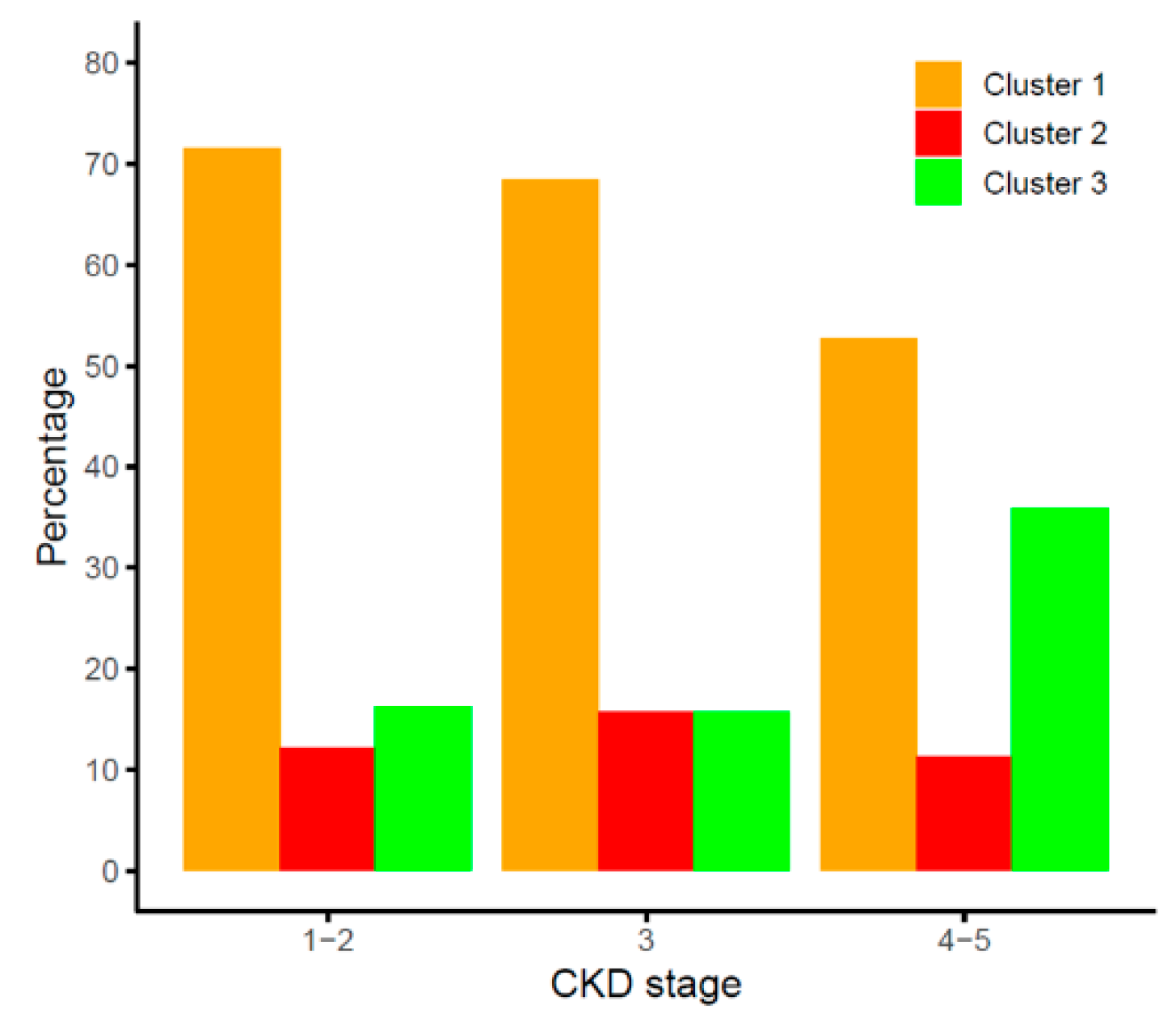

2.1. Combined FGF19 and β-Klotho Concentrations in Chronic Kidney Disease

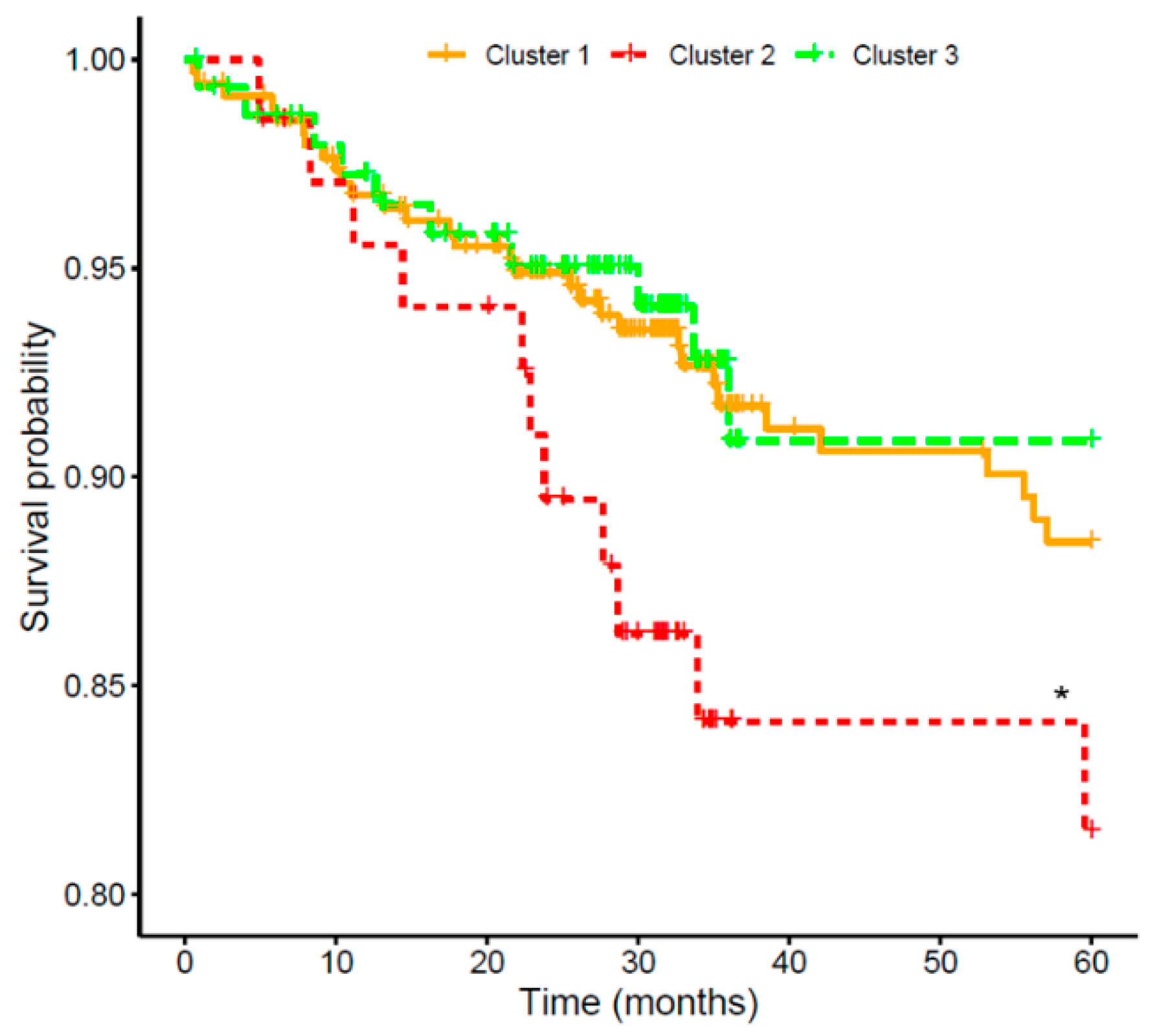

2.2. Effect of FGF19/β-Klotho Combined Concentrations on Cardiovascular Risk in CKD Patients

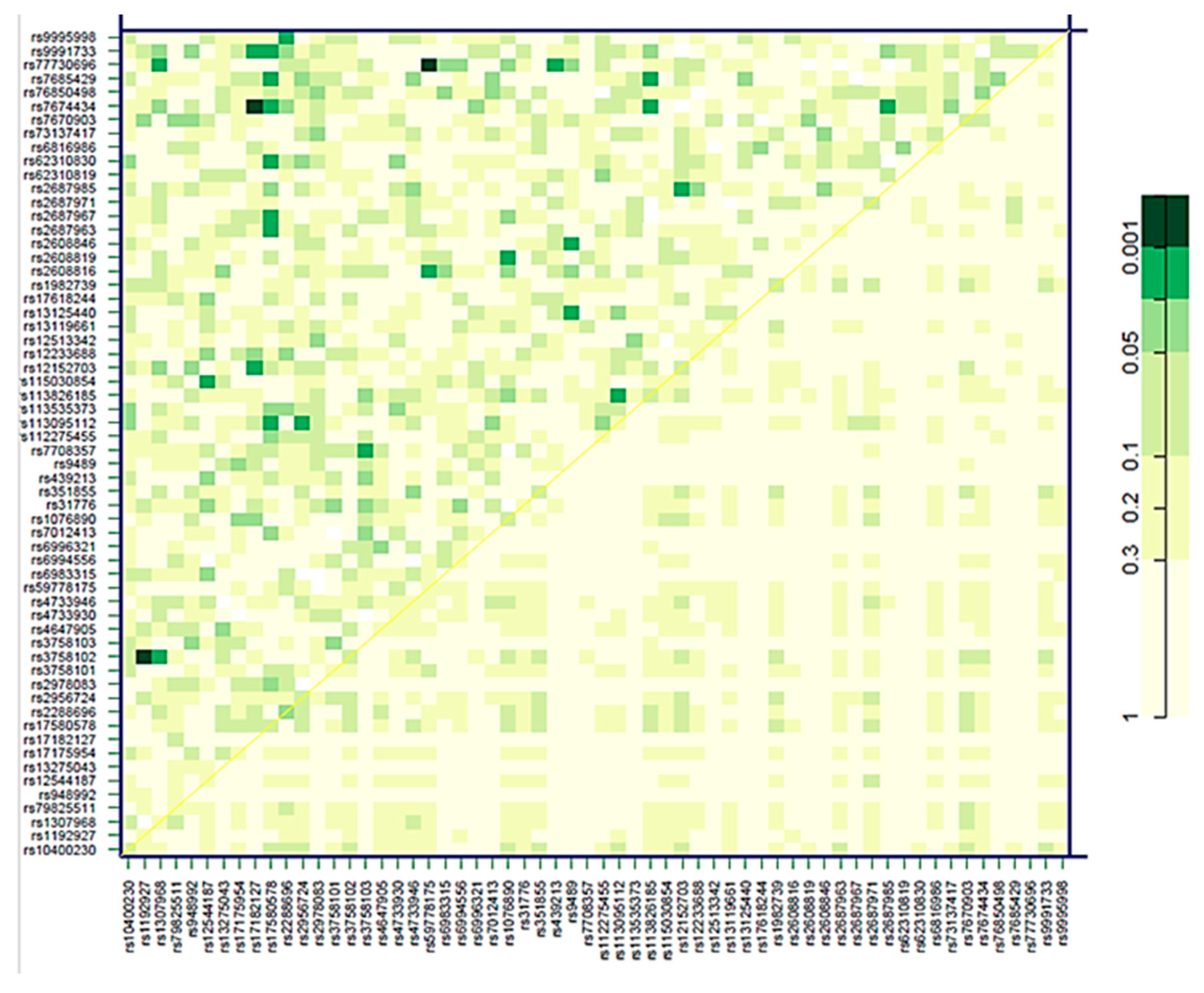

2.3. Association of Genetic Variants in the FGF19-Klotho System with Cardiovascular Risk

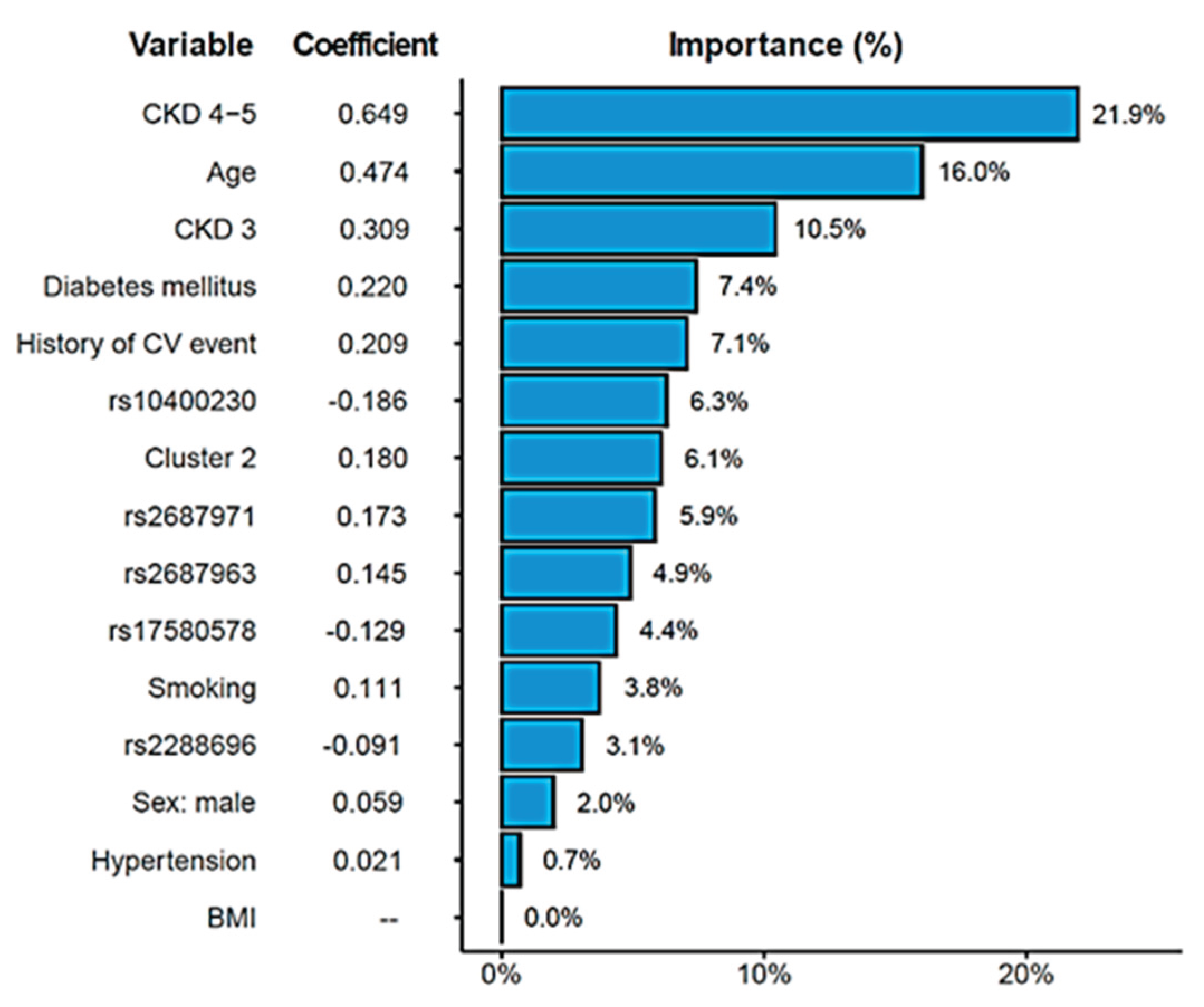

2.4. Combined Risk Model for Cardiovascular Risk in Chronic Kidney Disease

3. Discussion

4. Patients and Methods

4.1. Clinical Variables

4.2. Determination of Biomarkers Circulating Levels

4.3. Genetic Analyses

4.4. Statistical Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CKD | Chronic Kidney Disease |

| CVE | Cardiovascular Event |

| SNP | Single-nucleotide polymorphism |

| eGFR | Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate |

| HR | Hazard Ratio |

| ACR | Albumin to Creatinine Ratio |

| BMI | Body-mass Index |

References

- Ortiz, A. RICORS2040: the need for collaborative research in chronic kidney disease. Clin Kidney J 2022, 15, 372–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schunk, S.J.; Zimmermann, P. Cardiovascular Risk and Its Presentation in Chronic Kidney Disease. J Clin Med 2025, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, N. Regulation and Potential Biological Role of Fibroblast Growth Factor 21 in Chronic Kidney Disease. Front Physiol 2021, 12, 764503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alobaidi, S., Emerging Biomarkers and Advanced Diagnostics in Chronic Kidney Disease: Early Detection Through Multi-Omics and AI. Diagnostics (Basel) 2025, 15.

- Phan, P.; Ternier, G.; Edirisinghe, O.; Kumar, T.K.S. Exploring endocrine FGFs - structures, functions and biomedical applications. Int J Biochem Mol Biol 2024, 15, 68–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuro, O.M. Klotho and endocrine fibroblast growth factors: markers of chronic kidney disease progression and cardiovascular complications? Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2019, 34, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, M.B.; Jorge, G.; Zanardo, L.W.; et al. The role of FGF19 in metabolic regulation: insights from preclinical models to clinical trials. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2024, 327, E279–E289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, T.; Tang, X.; Bai, X.; Xiong, H. FGF19 Promotes the Proliferation and Insulin Secretion from Human Pancreatic beta Cells Via the IRS1/GLUT4 Pathway. Exp. Clin. Endocrinol. Diabetes 2024, 132, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Fu, L.; Sun, J.; et al. Structural basis for FGF hormone signalling. Nature 2023, 618, 862–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Jin, C.; Li, X.; Wang, F.; McKeehan, W.L.; Luo, Y. Differential specificity of endocrine FGF19 and FGF21 to FGFR1 and FGFR4 in complex with KLB. PLoS One 2012, 7, e33870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, S.; Koyama, D.; Igarashi, R.; et al. Serum Endocrine Fibroblast Growth Factors as Potential Biomarkers for Chronic Kidney Disease and Various Metabolic Dysfunctions in Aged Patients. Intern. Med. 2020, 59, 345–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolegowska, K.; Marchelek-Mysliwiec, M.; Nowosiad-Magda, M.; Slawinski, M.; Dolegowska, B. FGF19 subfamily members: FGF19 and FGF21. J. Physiol. Biochem. 2019, 75, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, M.; Guo, J.; Tao, H.; et al. Circulating mediators linking cardiometabolic diseases to HFpEF: a mediation Mendelian randomization analysis. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2025, 24, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morita, H.; Hoshiga, M. Fibroblast Growth Factors in Cardiovascular Disease. J Atheroscler Thromb 2024, 31, 1496–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchelek-Mysliwiec, M.; Dziedziejko, V.; Nowosiad-Magda, M.; et al. Chronic Kidney Disease Is Associated with Increased Plasma Levels of Fibroblast Growth Factors 19 and 21. Kidney Blood Press. Res. 2019, 44, 1207–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, S.; James, M.; Wiebe, N.; et al. Cause of Death in Patients with Reduced Kidney Function. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2015, 26, 2504–2511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, A.C.; Nagler, E.V.; Morton, R.L.; Masson, P. Chronic Kidney Disease. Lancet 2017, 389, 1238–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarun, T.; Ghanta, S.N.; Ong, V.; et al. Updates on New Therapies for Patients with CKD. Kidney Int Rep 2024, 9, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freise, C.; Jernej, T.; Metzkow, S.; Schnorr, J.; Taupitz, M. Fibroblast growth factor-23 remodels vascular extracellular matrix via glycosaminoglycan induction: implications for calcification in chronic kidney disease. Ren. Fail. 2025, 47, 2567528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgado, J.V.; Goes, M.A.; Salgado Filho, N. FGF21 and Chronic Kidney Disease. Metabolism 2021, 118, 154738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Rodríguez, L.; Martí-Antonio, M.; Mota-Zamorano, S.; et al. Combined concentrations and genetic variability of Fibroblast Growth Factors predict cardiovascular risk in renal patients. iScience 2025, On line ahead of print. [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Wang, Y.; Guo, Y.; et al. Fibroblast growth factor 19 improves cardiac function and mitochondrial energy homoeostasis in the diabetic heart. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 505, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Yang, P.; Sun, L.; et al. High plasma fibroblast growth factor 19 is associated with improved prognosis in patients with acute ischemic stroke. Clin. Nutr. 2025, 48, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Liu, Z.; Tong, Y.; et al. Fibroblast Growth Factor 19 Levels Predict Subclinical Atherosclerosis in Men With Type 2 Diabetes. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2020, 11, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchelek-Mysliwiec, M.; Dziedziejko, V.; Dolegowka, K.; et al. Association of FGF19, FGF21 and FGF23 with carbohydrate metabolism parameters and insulin resistance in patients with chronic kidney disease. J Appl Biomed 2020, 18, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiche, M.; Bachmann, A.; Lossner, U.; Bluher, M.; Stumvoll, M.; Fasshauer, M. Fibroblast growth factor 19 serum levels: relation to renal function and metabolic parameters. Horm. Metab. Res. 2010, 42, 178–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaldijk, A.S.; Verzijl, C.R.C.; Jonker, J.W.; Struik, D. Biological and pharmacological functions of the FGF19- and FGF21-coreceptor beta klotho. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2023, 14, 1150222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Yu, L.; Yin, X.; Ye, J.; Li, S. Correlation Between Soluble Klotho and Vascular Calcification in Chronic Kidney Disease: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review. Front Physiol 2021, 12, 711904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.Y.; Lu, Y.W.; Richardson, J.; et al. A systematic dissection of sequence elements determining beta-Klotho and FGF interaction and signaling. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 11045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sunaga, H.; Yoshida, K.; Kagami, K.; et al. Prognostic Impact of Fibroblast Growth Factor 21 in Patients With Heart Failure. Circ Rep 2025, 7, 922–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ianos, R.D.; Iancu, M.; Pop, C.; et al. Predictive Value of NT-proBNP, FGF21, Galectin-3 and Copeptin in Advanced Heart Failure in Patients with Preserved and Mildly Reduced Ejection Fraction and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Medicina (Kaunas) 2024, 60 . [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.H.; Xu, E.; Hildebrandt, M.A.; et al. Genetic variants in the fibroblast growth factor pathway as potential markers of ovarian cancer risk, therapeutic response, and clinical outcome. Clin. Chem. 2014, 60, 222–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Luo, W.; Chen, L.; et al. Ang II (Angiotensin II)-Induced FGFR1 (Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor 1) Activation in Tubular Epithelial Cells Promotes Hypertensive Kidney Fibrosis and Injury. Hypertension 2022, 79, 2028–2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, C.; Dou, C.; Liu, D.; et al. Multivariate genome-wide analyses of insulin resistance unravel novel loci and therapeutic targets for cardiometabolic health. Nat Commun 2025, 16, 10057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, M.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; et al. Genetic polymorphisms associated with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease and cardiometabolic risk susceptibility in the Chinese Han population. Hum Genomics 2025, 19, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunez-Rodriguez, A.; Garcia-Rodriguez, S.; Pozo-Agundo, A.; et al. Targeted next-generation sequencing panel to investigate antiplatelet adverse reactions in acute coronary syndrome patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention with stenting. Thromb. Res. 2024, 240, 109060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Zhu, J.; Han, W.; et al. Significance of serum microRNAs in pre-diabetes and newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes: a clinical study. Acta Diabetol. 2011, 48, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mota-Zamorano, S.; Gonzalez, L.M.; Robles, N.R.; et al. Polymorphisms in glucose homeostasis genes are associated with cardiovascular and renal parameters in patients with diabetic nephropathy. Ann. Med. 2022, 54, 3039–3051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erqou, S.; Shahab, A.; Fayad, F.H.; et al. Cardiovascular Risk Prediction Scores in Type 1 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JACC Adv 2025, 4, 101462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.S.; Matsushita, K.; Sang, Y.; et al. Development and Validation of the American Heart Association's PREVENT Equations. Circulation 2024, 149, 430–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Rodriguez, L.; Marti-Antonio, M.; Mota-Zamorano, S.; et al. Endothelin-1 as dual marker for renal function decline and associated cardiovascular complications in patients with chronic kidney disease. Eur J Intern Med 2025, 106542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, L.M.; Robles, N.R.; Mota-Zamorano, S.; et al. Influence of variability in the cyclooxygenase pathway on cardiovascular outcomes of nephrosclerosis patients. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gervasini, G.; Verde, Z.; Gonzalez, L.M.; et al. Prognostic Significance of Amino Acid and Biogenic Amines Profiling in Chronic Kidney Disease. Biomedicines 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foreman, K.J.; Marquez, N.; Dolgert, A.; et al. Forecasting life expectancy, years of life lost, and all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 250 causes of death: reference and alternative scenarios for 2016-40 for 195 countries and territories. Lancet 2018, 392, 2052–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiler, S.; Wen, M.; Roth, H.J.; et al. Plasma Klotho is not related to kidney function and does not predict adverse outcome in patients with chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2013, 83, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sellier, A.B.; Seiler-Mussler, S.; Emrich, I.E.; et al. FGFR4 and Klotho Polymorphisms Are Not Associated with Cardiovascular Outcomes in Chronic Kidney Disease. Am. J. Nephrol. 2021, 52, 808–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunawan, A.; Fajar, J.K.; Tamara, F.; et al. Nitride oxide synthase 3 and klotho gene polymorphisms in the pathogenesis of chronic kidney disease and age-related cognitive impairment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. F1000Res 2020, 9, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Zhu, H.; Chen, X.; et al. Genetic Variants Flanking the FGF21 Gene Were Associated with Renal Function in Chinese Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. J Diabetes Res 2019, 2019, 9387358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| CKD 1-2 (N=174) | CKD 3 (N=89) | CKD 4-5 (N=316) | *p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males (%) | 97 (55.7%) | 59 (66.3%) | 202 (63.9%) | 0.133 |

| Age (Years) | 58.0 (49.0-67.0) | 66.0 (60.0-75.0) | 71.0 (60.0-79.3) | <0.0001 |

| Weight (Kg) | 81.0 (66.3-91.4) | 79.7 (73.0-90.5) | 78.1 (67.1-89.1) | 0.108 |

| BMI | 28.3 (25.1-31.1) | 29.5 (26.8-32.4) | 28.8 (25.5-32.7) | 0.099 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 100.5 (93.0-112.0) | 111.0 (97.0-145.0) | 101.0 (90.0-119.3) | <0.0001 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 173.0 (154.3-196.8) | 158.0 (138.0-199.0) | 144.0 (122.8-171.3) | <0.0001 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 54.0 (44.0-64.0) | 46.0 (37.0-54.0) | 45.0 (37.0-57.0) | <0.0001 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 96.0 (79.0-114.0) | 83.0 (62.0-109.5) | 68.7 (51.0-92.0) | <0.0001 |

| Total calcium (mg/dL) | 9.4 (9.3-9.7) | 9.6 (9.2-9.8) | 9.3 (8.9-9.6) | <0.0001 |

| Potassium (mEq/L) | 4.3 (4.1-4.6) | 4.7 (4.4-5.1) | 5.0 (4.5-5.3) | <0.0001 |

| Sodium (mEq/L) | 141.0 (140.0-143.0) | 142.0 (140.0-143.0) | 141.0 (139.0-142.0) | 0.0001 |

| ACR (mg/g) in urine 24h | 8.4 (4.2-31.3) | 97.7 (12.4-281.9) | 410.0 (139.4-1180.0) | <0.0001 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 98.9 (83.3-106.8) | 40.9 (33.7-49.0) | 16.4 (13.0-20.0) | <0.0001 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 132.0 (123.0-147.0) | 147.0 (129.5-164.0) | 144.0 (127.0-163.3) | <0.0001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 80.0 (74.0-89.0) | 80.0 (67.5-87.5) | 74.0 (66.0-85.0) | <0.0001 |

| Pulse pressure (mmHg) | 51.0 (43.0-64.0) | 67.0 (53.5-83.0) | 69.0 (51.0-86.3) | <0.0001 |

| Hypertension (%) | 0.042 | |||

| No | 40 (23.0%) | 16 (18.0%) | 44 (13.9%) | |

| Yes | 134 (77.0%) | 73 (82.0%) | 272 (86.1%) | |

| Diabetes (%) | <0.0001 | |||

| No | 143 (82.2%) | 40 (44.9%) | 167 (52.8%) | |

| Yes | 31 (17.8%) | 49 (55.1%) | 149 (47.2%) | |

| Smoking (%) | 0.304 | |||

| Nonsmoker | 84 (48.8%) | 33 (38.8%) | 140 (44.4%) | |

| Ever smoker | 88 (51.2%) | 52 (61.2%) | 175 (55.6%) | |

| Hyperlipidemia (%) | <0.0001 | |||

| No | 120 (69.0%) | 40 (44.9%) | 90 (28.6%) | |

| Yes | 54 (31.0%) | 49 (55.1%) | 224 (71.1%) |

| No CVE (N=527) | CVE (N=52) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Males (%) | 322 (61.1%) | 36 (69.2%) | 0.214 |

| Age (Years) | 66 (56-75) | 72 (66-78) | <0.0001 |

| Weight (Kg) | 79 (68-90) | 79 (69-90) | 0.417 |

| BMI | 28.7 (25.5-32.5) | 28.9 (25.6-31.8) | 0.751 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 101.0 (91.0-117.0) | 123.0 (96.5-150.5) | 0.001 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 158 (136-184) | 129 (117-175) | <0.0001 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 48 (39-60) | 43 (36-52) | 0.001 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 82 (61-104) | 60 (51-93) | 0.005 |

| Total calcium (mg/dL) | 9.4 (9.1-9.7) | 9.3 (8.9-9.6) | 0.116 |

| Potassium (mEq/L) | 4.7 (4.3-5.1) | 4.8 (4.4-5.3) | 0.613 |

| Sodium (mEq/L) | 141 (139-143) | 141 (139-142) | 0.990 |

| ACR (mg/g) in urine 24h | 156.5 (14.2-594.1) | 377.9 (73.3-1056.7) | <0.0001 |

| Troponin | 33.3 (21.5-51.6) | 49.3 (34.8-68.5) | 0.045 |

| NT_proBNP | 796 (307-2092) | 2923 (698-6538) | 0.007 |

| eGFR (ml/min/1.73 m2) | 26.0 (16.0-81.5) | 20.0 (15.0-42.3) | <0.0001 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 140 (125-159) | 149 (132-167) | 0.082 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 77 (69-87) | 74 (66-84) | 0.025 |

| Pulse pressure (mmHg) | 61 (47-78) | 73 (60-86) | 0.001 |

| Hypertension (%) | 0.128 | ||

| No | 94 (17.8%) | 6 (11.5%) | |

| Yes | 433 (82.2%) | 46 (88.5%) | |

| History of CV event (%) | <0.0001 | ||

| No | 395 (75.4%) | 28 (54.9%) | |

| Yes | 129 (24.6%) | 23 (45.1%) | |

| Diabetes (%) | <0.0001 | ||

| No | 330 (62.6%) | 20 (38.5%) | |

| Yes | 197 (37.4%) | 32 (61.5%) | |

| CKD stages | <0.0001 | ||

| CKD 1-2 | 170 (32.3%) | 4 (7.7%) | |

| CKD 3 | 75 (14.2%) | 14 (26.9%) | |

| CKD 4-5 | 282 (53.5%) | 34 (65.4%) | |

| Smoking (%) | 0.308 | ||

| Non smoker | 238 (45.6%) | 19 (38.0%) | |

| Ever smoker | 284 (54.4%) | 31 (62.0%) | |

| Hyperlipidemia (%) | 0.032 | ||

| No | 234 (44.5%) | 16 (30.8%) | |

| Yes | 291 (55.3%) | 36 (69.2%) |

| SNP | Genotype | No CVE | CVE | HR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FGFR1 rs2288696 | G/G | 87.6% | 12.4% | Reference | |

| A/G, A/A | 91.5% | 8.5% | 0.51 (0.27,0.95) | 0.029 | |

| KLB rs2687971 | C/C | 91.9% | 8.1% | Reference | |

| CG, GG | 88.1% | 11.9% | 2.03 (0.97,4.27) | 0.046 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).