1. Introduction

Emergence and self-organization are two of the core concepts of the new science of complexity [

1,

2,

3,

4]. When describing complex adaptive systems, such as flocks of birds, markets, cities, or far-from-equilibrium chemical reactions, researchers commonly observe processes of self-organization that lead to the emergence of novel properties. Moreover, if we look more deeply, at the most fundamental problems in the whole of science, such as the origins of space-time [

5], matter, life [

6], mind, consciousness, language [

7] and culture, then we must conclude that these phenomena have emerged in some particular period in the history of the universe, and that this process can only be really understood as one of self-organization [

8].

The only alternative to explain the appearance of such fundamentally novel forms is that they have been created by some intelligent designer, separate from these emerging forms. But this immediately begs the question where this designer came from. A possible answer is self-creation, but that seems tantamount to self-organization. This merely brings us back to square one: how can a whole create itself, and thus produce genuine novelty, without some pre-existing agent directing the process?

Because this is such a deep, metaphysical problem, it may appear that science is not able to answer it. After all, the traditional, Newtonian worldview of science is materialistic, deterministic and reductionistic [

9]. That means that it reduces all change to the movement of material particles along predetermined trajectories that are governed by the Laws of Nature. In such a worldview, there is no room for novelty, creation, agency, uncertainty, freedom, or purpose. However, since the 19

th century, when this worldview became dominant, we have witnessed a number of scientific revolutions—including quantum mechanics, chaos theory, and complexity—that have shaken the Newtonian worldview to its core. The emerging new worldview of complexity embraces uncertainty from the beginning, while focusing on the non-linear interactions and feedbacks between systems, agents and their environments that give rise to novel structures [

9,

10].

Starting from a minimal assumption of what a system is, I will now argue that emergence and self-organization arise commonly and naturally when such systems are allowed to interact and become coupled. Thus, I hope to show that these phenomena are conceptually simple, requiring no outlandish metaphysical assumptions, even when their products become increasingly complex.

2. Wholes and Emergent Properties

Reductionism is the assumption that every property of a whole is ultimately reducible to the properties of its parts. More precisely, it assumes that given everything we know about the parts, we can explain and predict everything there is to know about the whole. In contrast, systems thinking assumes that

a whole is more than the sum of its parts [

9,

11]. That means that it has certain additional properties that cannot be derived just from the properties of its parts. These are the properties that are commonly called

emergent [

12,

13,

14]. Some examples will illustrate such emergent properties.

A classic example from physics is temperature, which measures the average kinetic energy of the molecules that make up a gas, liquid or solid. A single molecule does not have a temperature. One may object that a molecule still has a velocity of movement and therefore a kinetic energy. However, velocity is not absolute, but relative to some standard of rest. Without other molecules relative to which one molecule is moving, there cannot be an absolute velocity and therefore no average kinetic energy or temperature. A similar example is the property of the hardness of a material, such as iron. Hardness measures the strength of the bonds between the atoms or molecules in the material: how difficult is it to dislodge individual atoms from the material? Therefore, a single atom does not have any hardness.

These examples of common physical properties suggest that you need a very large number of simple components, such as atoms, in order to have emergent properties [

15]. Nevertheless, this is a frequent misapprehension about emergence. Some examples from other domains will show that emergence does not require large numbers. Consider the property of a marriage as being happy or miserable. Independently examining the properties of each of the partners in the marriage will in general not allow you to predict whether their marriage will be happy or miserable. Like in the case of hardness or temperature, this is a property of the

relation between the components, not of the components individually. And in this case, two components are sufficient to establish a relation that has meaningful, holistic, and irreducible properties.

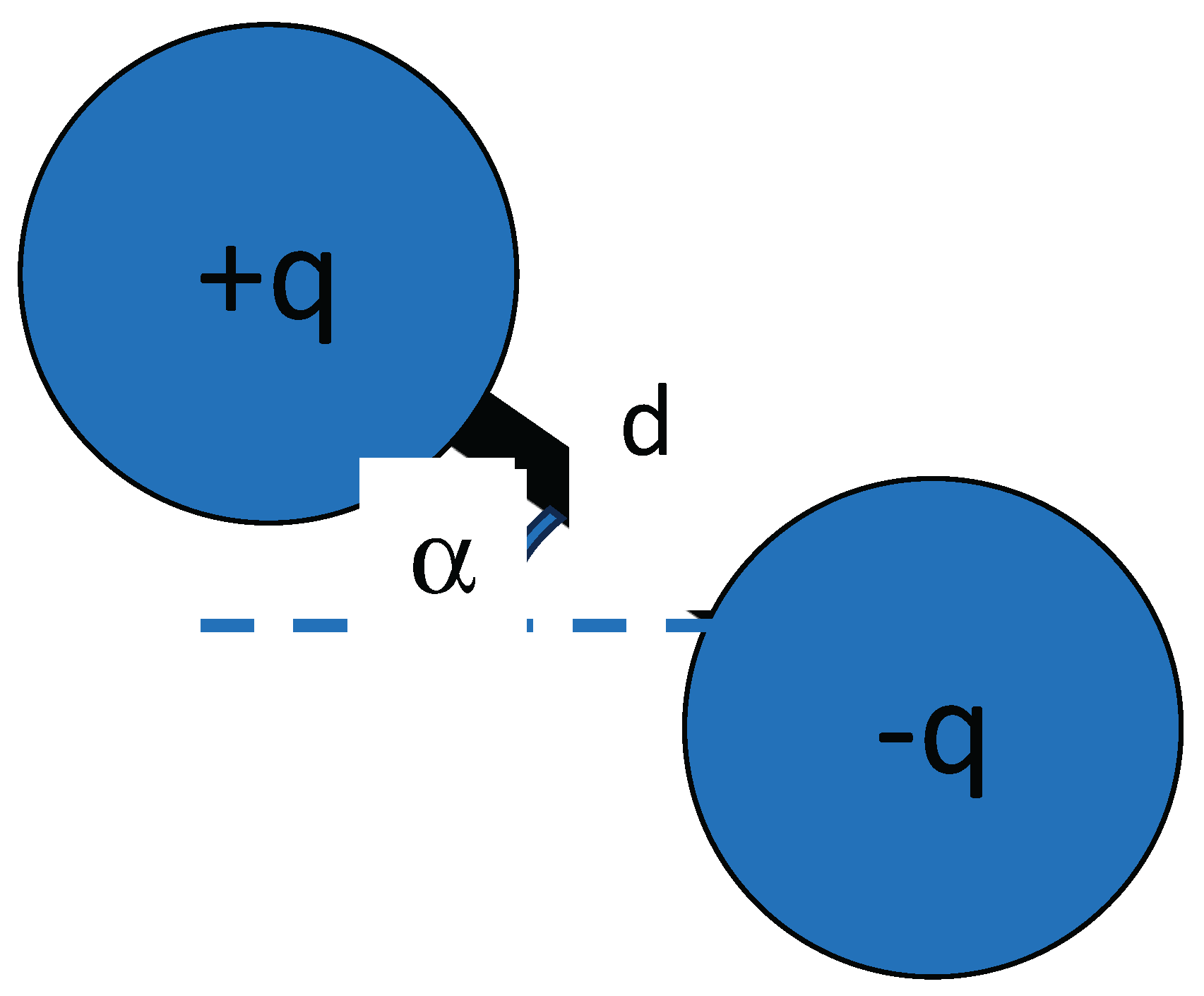

Still, when the components of the whole are people, these components already have such a rich variety of properties that we may consider the emergent relationship as something intrinsically difficult to characterize. Let us then consider an extremely simple example of a two-component whole: an electric

dipole. A dipole is formed when two equal but opposite charges +

q and –

q (e.g. two atoms) stick together because of their electrostatic attraction, while remaining at a small distance from each other (see

Figure 1). If properties were merely additive, the total charge of the dipole would be zero: +

q –

q = 0.

That implies that it would be insensitive to electrostatic fields. However, because of the distance between the two charges, the dipole will orient itself so that its positive pole points towards a negative charge and away from any positive charge, and vice-versa for its negative pole. This tendency of a dipole to orient itself parallel to the electrical field, is captured by an emergent property called

dipole moment, which is determined by the charges

q, their distance

d and their orientation a [

16]. The individual components of the dipole, on the other hand, are (spherically) symmetric: they have no orientation or distance, and therefore lack this property.

A dipole is an extremely simple model of a molecule. More complex molecules consist of different atoms arranged according to different orientations while carrying different densities of charge. Therefore, different molecules have different chemical properties in terms of bonding or reacting with other molecules, even when they consist of the same atoms. The infinite variety of shapes that organic molecules can take underlies the complex structures and processes that constitute a living organism. For example, each sequence made of amino acids, selected out of the 20 types of amino acids used by life, constitutes a different protein. Such a protein is characterized by a complex three-dimensional structure, and a unique ability to catalyze certain metabolic reactions.

Some everyday examples may further show that emergent properties are truly common. When we appreciate a song for its properties of rhythm, harmony, and melody, then we are not paying attention to the pitch, loudness or duration of the individual notes that make up the musical piece. We are sensitive to the way these notes follow each other, forming a coherent pattern extended in time. It is possible to replace every individual component (note) by one with a different pitch, timbre, duration, or loudness, and yet still recognize the same melody in this arrangement of notes. That is because the elements of a melody can maintain their relations (higher-lower, longer-shorter, or louder-quieter) even while changing individually. Thus, melody is an emergent property that cannot be reduced to the properties of the notes that compose it.

As a last concrete example, a car can be characterized by properties such as weight, fuel consumption, and maximum speed. The only property here that is not emergent is weight, which is merely the sum of the weights of all the individual components of the car, such as tires, engine, body, and seats. However, none of these components has anything like a maximum speed on its own: it is only the particular manner in which they are arranged in a three-dimensional shape that will determine how efficient the resulting assembly will be in overcoming the forces of friction that slow down movement and thus impose a maximum speed and fuel consumption.

3. Measuring Properties

While such examples are intuitively clear, one may wonder whether they would still hold up to a more formal analysis. To perform such an analysis, we must provide a formal definition of a property. Such a definition has been elaborated in the foundations of quantum mechanics [

17,

18]. Unlike classical mechanics, quantum mechanics does not assume that the properties of some system, such as an electron, are inherent to the system. Instead, quantum theory defines properties as the outcome of an observation, i.e. an interaction between the system and some observation apparatus controlled by the experimenter. In quantum mechanics, measurable properties—such as position, momentum or spin—are called “observables”. This means that they result from a particular operation performed by an observer on the system (“preparation”), to which the system reacts in a particular way, after which the observer notes that reaction (“detection”).

For a simple illustration, consider the property of color. How do you determine the color of some object, such as a billiard ball? You shine white light on the ball and then observe the color of the light that is reflected. Note that you cannot observe the color of a ball in the dark: the system must first be subjected to some input (here, white light), after which you detect the output produced by the system in response to that input (here, reflection of only the red frequencies in that input). The property is then established by the relation between input and output.

In psychology, the input to the system being observed is traditionally called “stimulus” and its output is known as “response”. As an example of a psychological property, consider arachnophobia (fear of spiders). Determining the presence of this property in a person is simple: confront the person with a (non-dangerous) spider (stimulus). If the person reacts with fright, e.g. by running away (response), then we may conclude that he or she exhibits arachnophobia.

This operational determination of properties also works for properties that can vary over time, such as position, velocity, or momentum. In the example of the dipole (

Figure 1), charge

q and distance

d are assumed to be invariant, while orientation a can vary, e.g. under the influence of an electric field. Here the measured value of the property will depend on the variable state of the system being observed.

As another example, in physics the momentum of a system such as a moving billiard ball can be measured through the following experiment: let the ball hit a static object with known mass m; then measure the velocity of the object after it was hit. Velocity times mass then defines the momentum imparted by the ball to the object.

The principle also holds for qualitative rather than quantitative properties. Here, what the observation establishes is whether a particular property, such as “redness”, is present or not. The corresponding measurement has two possible outcomes, 1 (

yes, the reflected light is red) or 0 (

no, the reflected light is not red). The corresponding experiment can be conceived as asking the system a

yes-no question [

17,

18].

4. Measuring Emergent Properties

We have defined a property of a system as the relation between a particular input received by the system and the corresponding output produced by the system. An emergent relationship would then be an input-output relation for a whole (system), where that whole is more than a mere collection of loose components. We say that components form a system or whole when they are

coupled in a particular manner. When they are independent, i.e. not coupled, then the components form an

aggregate rather than a

system [

19,

20]. An example of an aggregate is sand, which consists of separate grains of sand. A sandstone, on the other hand is a system, because it consists of grains of sands that are coupled together, and therefore are unable to move independently. Another example of an aggregate is a group of people wandering individually across a lawn. A team of people playing a football game on that same lawn, on the other hand, forms a system, because their movements are dependent on each other: the action of one player, such as kicking the ball, will incite an action by another player, such as running after the ball.

In systems theory, coupling between components is defined in terms of inputs and outputs [

9,

19]. If the inputs of some of the components depend on the inputs or outputs of other components, then these components are coupled. For example, the output of one football player (kicked ball) becomes the input of another player. The simplest case of coupling is

serial (or sequential): components A and B are coupled in series if the output of A forms (part of) the input of B. Other rudimentary forms of coupling are

parallel (A and B both receive input from the same system and provide output to another system), and

circular (input of A is output of B and vice-versa).

Serial coupling already provides us with an example of an emergent property. Imagine that A is a yellow object, and that B is a transparent sheet of blue glass. The input of A, as in our previous example of color, is white light. Its output is yellow light. Assume that B is serially coupled to A, i.e. the output of A (yellow light) functions as input to B (blue glass). The glass will normally filter out the more reddish frequencies of the yellow light. The light that is let through by B (final output of the coupled system) will therefore appear as greenish. Thus, by coupling A and B we have created a whole with the new, emergent property of being green.

This is merely the simplest form of coupling. Complex systems can have the most intricate arrangement of serial, parallel and circular couplings between their different components, forming intricate networks. Examples are the integrated circuits connecting transistors that make up the motherboard of a computer, the food web characterizing which species consume which other species in an ecosystem, or the network of chemical reactions that make up the metabolism of an organism, such as a bacterium [

21].

Imagine a typical property we might use to characterize a species of bacteria, such as being sensitive to a certain antibiotic. This means that if the bacterium is subjected to the input of that antibiotic, it will die, i.e. it will disintegrate (output reaction of the system). But where in the circuit of interconnected components is the vulnerability to the antibiotic precisely situated? In general, we cannot say, because the antibiotic interferes with several biochemical reactions whose output functions as input to other reactions that in turn collaborate with further reactions to perform certain functions that are essential to the survival of the bacterium. A change in any of those reactions may change the reaction to the antibiotic, and thus potentially provide the bacterium with the new property of

antibiotic resistance [

6].

5. Systems as Constraints

We defined emergent properties as properties of a whole that lack in the components of that whole. That means that such properties can only arise when a whole is formed. A whole is formed when components become coupled, i.e. when inputs and outputs become connected in a dependable manner, so that a certain component normally receives its input from the output of one or more other components. For example, B (footballer) normally receives input from A and C (players in the same team), but not from D or E (players in the other team). That implies that the interactions between the different components are not arbitrary but constrained.

Thus, a system can be understood as imposing a

constraint on its components [

20]. In contrast, for an aggregate the components are free to interact in any which way. For example, an (unbounded) gas is an aggregate of molecules that move independently, randomly colliding from time to time with other molecules. These collisions can be seen as input-output interactions, in which momentum (output) is transferred from one molecule to another (input). However, there is no restriction on which molecule collides with which other molecule. In a crystal, on the other hand, the molecules are rigidly coupled with their neighbors according to a specific geometric arrangement. Such a constraint defines a certain order or organization in the system, restricting the number of possible interactions between components (e.g. molecules can pass on momentum only to their direct neighbors).

In artificial systems—such as a car or a motherboard—the particular organization has been imposed from the outside, by a designer who has decided that this component should connect in this way to this other component in order to produce the desired output. For example, in a traditional car, fuel coming from the tank is mixed with air and injected into the piston, forming its input. The further input of a spark, produced as output by the electrical battery, creates an explosion of this mixture that pushes the piston outward. This linear movement (output of the piston) is then converted into a circular movement of the wheels. That is in turn converted into a forward movement of the car. This specific arrangement of couplings between components implements the most important property of a car, namely its ability to transform fuel and air (its required input) into movement (its desired output) and exhaust (its undesired output). The efficiency of that process, which depends on the properties and arrangement of many other components, including the aerodynamic shape of the outer hull and the internal friction between the moving parts, determines the car’s emergent properties of maximum speed, fuel consumption, and emission of CO2.

Natural systems, such as crystals, rivers, or bacteria, have similar emergent properties that depend on the configuration of their parts. These include the hardness, transparency or color of a crystal, the flow rate of a river, and the multiplication rate of a bacterial species. From a biological perspective, a bacterial species can be conceived as a system that converts a given amount of food (input) into a number of additional bacteria and waste products (output). Different bacteria can be distinguished by their ability to process different types of foods under different conditions with varying efficiency into more bacteria. These properties depend on the coordinated action of multiple molecular and cellular components and reactions that are coupled within the bacterial metabolism [

6,

21].

6. Self-Organization and Evolution

The difference between artificial systems and natural systems is that in the natural case these couplings have not been imposed by a designer: they have evolved or self-organized. At the most fundamental level, both evolution and self-organization are governed by a mechanism of

variation and

natural selection. In its most general formulation, the principle of natural selection is so simple that it can be seen as a tautology—that is, a statement that is true by definition [

22]:

stable configurations (by definition of stability) tend to persist, while unstable ones tend to fall apart.

That means that stable configurations will be selected for survival, while unstable configurations will be eliminated, and eventually replaced by different (stable or unstable) ones. The only other ingredient we need to set in motion a process of evolution is the (undirected) variation that produces a variety of different configurations. Out of these, the most stable ones can then be repeatedly selected.

Imagine different atoms randomly colliding with each other. Most of the temporary configurations formed in this way will disintegrate nearly immediately. However, in less common cases, the atoms will couple in such a way as to form a chemical bond. This is a configuration that is energetically more stable than one where the atoms are disconnected: it requires energy to destroy such a bond. Once bonded to each other, atoms are constrained to remain together. They can no longer move or react independently. Such bonded atoms now form an encompassing system or “whole”: a molecule. As noted, this whole has emergent properties that were not present in its atomic components.

A classic example may illustrate the principle (Corning, 2002). The molecules of table salt (NaCl) consist of one sodium atom (Na) and one chlorine (Cl) atom. Separately, these atoms are highly reactive and therefore toxic to humans: sodium is a soft metal that will burn tissues, while chlorine is a poisonous gas that may kill when inhaled. The properties of the whole they form when bound together in a molecule are completely different: NaCl is a common ingredient of our food, forming white crystals, while having a pleasant, salty taste. That is because salt reacts completely differently to the same inputs than the elements that constitute it, for example when it is brought into contact with water or with bodily tissues.

The only process needed to generate such an emergent system is variation: atoms randomly colliding with other atoms to form different configurations. Selection then takes over by eliminating all configurations that are unstable, while retaining the stable ones. In a stable configuration, the components are in a sense mutually adapted: they are coupled in such a way that they can survive in their present state, protecting the whole from disintegration. From another perspective, the coupling between the components exhibits synergy (Corning, 1995): together they can achieve a form of stability that they could not achieve alone. Another example is a neutron. This particle is unstable on its own: it disintegrates after a while into a proton, electron and neutrino. However, it can survive forever when it is bonded by the strong nuclear force to one or more protons within an atomic nucleus.

The mechanism of mutual adaptation we described here is what the cybernetician Ashby has formulated long ago as “the principle of self-organization” [

24,

25]. Another way to formulate this principle uses the language of dynamical systems [

26,

27]—which is more common in complexity science. The different components together, even before they have become coupled, define a

dynamical system. Its variables, which define its state space, are the degrees of freedom of each of the individual components. The interactions between and forces working on the components define the dynamics of the overall system.

The dynamics of such a complex system typically exhibits a number of

attractors, i.e. regions in the state space that the system can enter, but cannot (through its own dynamics) leave [

28]. From a given initial state, the dynamic system will describe a (deterministic or stochastic) trajectory across its state space. This trajectory will typically end up in an attractor, given that once it enters an attractor, it can no longer leave that attractor. The further trajectory of the system is now restricted to remain within the attractor. In other words, the system is now

constrained: it no longer has the freedom to move outside the attractor. That constraint typically imposes linkages or couplings between the components of the system. These couplings, as Ashby argued, can be interpreted as

mutual adaptations. They also impose an organization characterized by emergent properties.

7. The Self-Organization of Complexity

Some further observations may explain how this intrinsically simple principle can give rise to complex forms of organization. First, the process does not stop at a given level of complexity. The emergent system formed in this way, such as a molecule, can still interact with other emergent systems, thus eventually forming a system of a higher order, such as a macromolecule. This type of system can similarly interact with others of its kind and form an even higher-order system, such as a primitive cell. This process of whole-formation recursively generates a hierarchical organization with multiple levels, which Herbert Simon has argued forms the characteristic “architecture of complexity” [

29,

30].

A second observation is that even at a given level, a system can grow by absorbing more and more components into a given configuration. An example is a crystal, where additional atoms can join the crystal lattice by bonding with the already bonded atoms in the lattice. This kind of growth is typically amplified through a positive feedback mechanism: the more components that have joined the stable configuration, the larger that configuration, and the greater the influence of that configuration is on the remaining unattached components, e.g. by offering more positions for these components to attach themselves to.

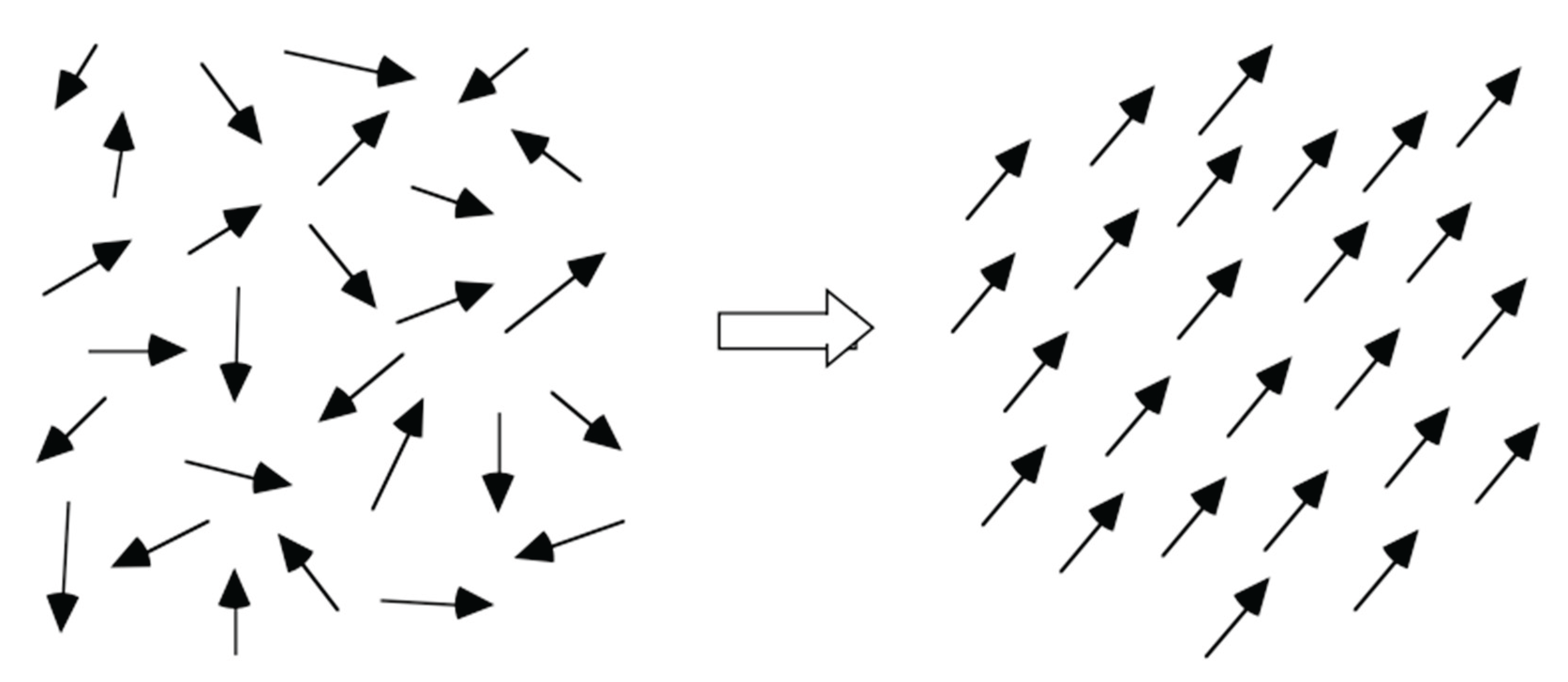

An instructive example of such a process is magnetization [

25]. Imagine a material such as iron, in which the different atoms each have a tiny magnetic field, initially pointing in different, random directions (see the arrows in

Figure 2). Self-organization starts when a few atoms, through chance fluctuations, align their fields so that they point in the same direction, instead of opposing each other. This aligned configuration is more stable, because magnetic fields pointing in opposite directions repel each other, while aligned ones reinforce each other. The aligned configuration will not only be more difficult to dislodge, but it will also exhibit synergy: together, the atoms produce a stronger overall magnetic field, thus having a stronger influence on the remaining magnetic atoms. Through on-going random variation caused by thermal fluctuations, the neighboring ones will sooner or later also join the aligned configuration, becoming difficult to dislodge, while further reinforcing the overall field. Thus, an accelerating “wave” of alignment will tend to sweep through all the atoms in the material, starting from the initial local alignment, until alignment becomes global, with all atoms pointing in the same direction (Fig. 2). This illustrates a common characterization of self-organization as

global order arising from local interactions [

2,

25].

A similar process can be found in social self-organization, where people tend to conform (“align”) to the norms of the people they most closely interact with (typically their geographic neighbors), until the whole group settles on using the same norms [

31,

32,

33]. The selection principle here is that individuals that obey different norms will encounter conflict, friction or misunderstanding with the others they interact with, putting them in a difficult (unstable) position. They can stabilize their position by conforming to the norms of the majority, thus joining that majority and increasing its power to make further converts.

In these cases, the different components are assumed to be similar, and therefore self-organization tends to end up in an ordered, repetitive arrangement in which the components all behave similarly. However, the principle of mutual adaptation does not in general lead to conformity or sameness. When the components are diverse, such as different species in an ecosystem, different companies in a market, or people with different interests and skills, then self-organization rather tends to result in further

differentiation, i.e. increased diversity. In ecology, this evolved differentiation is known as

adaptive radiation [

34]. This can be understood as a form of division of labor: each component tends to find its own, personal “niche”, specializing in activities that are different from the ones of the others [

19]. As a result, they no longer obstruct or compete with each other, but rather complement each other, by consuming inputs or producing outputs that the others cannot consume or produce as efficiently, thus generating synergy.

Another observation is that the emerging organization does not need to be static or rigid, the way it is in a molecule or a crystal. A system in its most general terms can be viewed as a

process that transforms input into output. Coupled systems then are coupled processes, characterized by an on-going flow of matter and energy throughout the system. For example, an ecosystem is a complex network of living organisms (plants, animals, bacteria, fungi…) and geophysical flows (sunlight, rivers, rain, erosion, sedimentation…) that is characterized by a

self-maintaining configuration [

35,

36]. This means that all flows, i.e. resources continuously produced by one type of system as output (e.g. rainwater), are consumed as input by one or more other types of systems (e.g. rivers, plants, animals). Vice-versa, all resources consumed by certain systems (e.g. food, oxygen) are produced again by other systems (e.g. plants). Therefore, the flows never stop, and the ecosystem remains running.

Chemical Organization Theory is a recently developed formalism for modeling such self-maintaining networks of processes [

6,

36,

37]. It demonstrates that such self-sustaining configurations (called “chemical organizations”) can self-organize rather easily. This happens by different processes mutually adjusting their inputs and outputs until they are either in balance with others—or eliminated because they could not find a sufficient inflow of resources. This is similar to how a new species that enters an ecosystem either learns to efficiently use the resources available, or is eliminated because it could not adapt [

35].

The metabolism of a living organism, such as a bacterium, can also be modeled as such a self-maintaining organization, where everything consumed by one reaction is produced again by one or more other reactions [

21,

35]. Here, we observe an additional mechanism of variation by the acquisition of new genes (through mutation or recombination). A gene normally codes for an enzyme, which in turns catalyzes a reaction that consumes certain molecules and produces other molecules. The introduction of this new process may make the metabolism more (or less) efficient in producing necessary resources, or in removing waste products or toxins (e.g. neutralizing antibiotics). As a result, the organism as a whole may become more (or less) likely to survive and multiply. In this way, variation in the self-organizing network of processes, as encoded and reliably stored in the genome, allows organisms to adapt and evolve. They thus accumulate an increasingly complex and powerful repertoire of processes and components for dealing with an increasingly wide variety of challenges [

6]. It is this cumulative nature of genetic variation and selection that explains the emergence of advanced biological functions and forms of organization, such as organs, skeletons, sensory organs, nervous systems, and finally human intelligence.

8. The Unpredictability of Emergent Properties

Reductionists are unlikely to be convinced by the above argument that self-organization produces emergent properties, i.e. properties that cannot be explained by the properties of the parts. They will argue that the interactions that result in components becoming coupled after all depend on the individual properties of these components. For example, the alignment between magnetic atoms is caused by the magnetic fields of the individual atoms, and the molecules formed by atoms are dependent on the quantum properties of these atoms, such as the number of electrons in the atom’s outer orbitals. In theory, all possible molecular configurations could be derived from these atomic properties.

In practice, however, the number of possible configurations is so large as to be effectively infinite (especially for organic molecules). Moreover, the number of possible interaction processes between atoms is actually infinite. Finally, the Heisenberg uncertainty principle in quantum mechanics implies that their outcome is intrinsically unpredictable. Therefore, we in general cannot determine what configuration will be the outcome from a particular interaction. For example, we cannot predict whether two colliding atoms will bond and form a molecule or continue on their independent trajectories. It is only at the statistical level of billions of such encounters that we can estimate how many bonds will be formed during a particular chemical reaction.

This unpredictability of variation applies even more strongly to interactions at levels more complex than atoms. For example, it is simply impossible to predict which mutation may affect a genome, which new species may enter an ecosystem, or which new idea may come up in a community of people. Since the interactions in such systems are typically non-linear, such variation can moreover be amplified through positive feedback. This is the basis of the famous “butterfly effect” in chaotic systems, which is more technically known as “sensitive dependence on initial conditions” [

25,

38]. It means that variations too small to observe (such as the pressure differential caused by a butterfly flapping its wings) may cause enormous differences in the eventual effect (such as the formation of a hurricane).

Selection will at most eliminate the unstable configurations. However, the remaining number of configurations stable enough to form a persistent system (e.g. all potentially viable organisms) is still effectively infinite. This is confirmed by the mathematical principle known as the

combinatorial explosion: the number of possible combinations of elements increases exponentially with the number of elements to be combined. The number of combinations of combinations increases even more radically, as noted by Kauffman’s

theory of the adjacent possible [

39,

40]. That makes an

a priori investigation of the space of possible outcomes effectively impossible, and the outcome of the process intrinsically unpredictable.

We may conclude that the forms and properties that could emerge through the processes of self-organization and evolution intrinsically cannot be determined. This statement holds not only in practice, but also in principle, because of the Heisenberg uncertainty principle and the non-linear amplification of the quantum fluctuations entailed by the butterfly effect. Therefore, most emergent forms are truly novel or creative: they not only never existed as such in the world, moreover their eventual coming into existence was impossible to deduce from the known properties of their components.

This intrinsic unpredictability applies even to a seemingly simple process such as magnetization [

25]. Initially, all the atoms in the magnetizable material point in different directions (Fig. 2). Random fluctuations may lead some neighboring atoms to temporarily point in the same direction, thus reinforcing each other’s magnetic field. Because of non-linear amplification, such local alignment may start to spread so that it eventually dominates the whole region. Since the direction of the initial alignment was random, the eventual direction of the global magnetic field that results from it is impossible predict. Yet, once reached, this alignment will be very stable, because any atom moving away from this alignment will have to overcome the opposing force of billions of other atoms that are still pointing in the same direction.

9. Downward Causation

While this argument may convince reductionists that the eventual emergent configuration cannot be predicted, they may retort that this configuration can still be fully explained by the properties of the lower-level components. According to this line of reasoning, the laws of nature are specified at the lowest level of components: the elementary particles. These laws specify the possible interactions and combinations of the components. The combinations still obey these same laws. Therefore, according to the reductionist perspective, the emergence of such a combination does not add anything fundamental to the way nature operates.

To clarify the situation, we need to explain what a scientific law precisely entails. A law imposes a restriction or

constraint on possible processes. For example, the law of energy conservation prohibits processes in which the total energy of the universe would increase or decrease. In the Newtonian, deterministic worldview [

41], such restrictions are assumed to be such that only a

single process is allowed at any given moment. However, we have just argued that in the new scientific worldview, which takes into account quantum indeterminacy, non-linearity and complexity, there is no such determinism: the number of potential processes is effectively infinite, even when it is constrained by laws such as energy conservation. It is precisely that infinite range of potential outcomes that allows the appearance of additional constraints that limit the range in some respect.

As we argued, the formation of an emergent whole is such a novel constraint. A whole imposes a restriction on the freedom of its constituent parts: they can no longer act independently, but must obey certain rules, norms, or “laws” inherent to the system to which they belong [

13]. For example, in a gas, which is an aggregate and not a system, molecules can move freely. On the other hand, in a crystal, there is an imposed order, mathematically characterized by translational and rotational symmetry, which specifies the precise positions at which molecules are allowed to reside. Similarly, the atoms in a magnetized material are all forced to align in the direction of the global magnetic field. This feature is called

downward causation [

42,

43,

44]. It is as if the whole, in a “top-down” manner, tells its parts how they should behave.

The traditional, reductionist picture only considers “upward” causation: the parts tell the whole how it should behave. If such upward causation is assumed to be deterministic (i.e. no freedom is left for the whole to select from a range of possible configurations), then it obviously does not make sense to consider any additional mechanism of downward causation. Otherwise, downward causation would either merely confirm the constraints imposed by upward causation, being superfluous, or—worse—it would contradict them, making the configuration self-contradictory and thus impossible to realize [

26]. If we follow this reasoning, there cannot be laws at the level of the whole that are irreducible to the laws at the level of the parts. That is why traditional science and philosophy tend to consider emergent organization as some bizarre phenomenon, which is either an illusion, an epiphenomenon that does not produce anything new, or a mystery that science cannot explain as yet (Corning, 2002; Cunningham, 2001).

On the other hand, if you assume incomplete determination at the level of the parts, then self-organized constraint resulting in downward causation—and with it the emergence of laws at the level of the whole—becomes a very simple and natural phenomenon. Let us demonstrate this with some examples of such higher-order, emergent laws [

5].

10. Emergent Laws

The

genetic code, which specifies which triplet of DNA base pairs is translated by the cellular machinery into which amino acid, and thus how genes code for proteins, is virtually universal for life [

46]. All organisms we know on Earth use the same code (with some minor exceptions in certain organelles and bacteria). Therefore, it appears like a law of biological organization. Yet, there are no laws of chemistry or physics that entail that only this coding scheme could work. If the transfer-RNA and the ribosome—the translation machinery that the cell uses to read sequences of RNA codons and convert them to proteins—would have a different structure, then the same DNA string would be translated to different proteins. The most likely explanation for this universal code is that at an early stage in the history of life, an effective coding process emerged through some random variation, and that its relative success in helping primitive cells survive was so great that its spread was non-linearly amplified, so that it outcompeted all rival organizations. That effectively fixed its specific organization as a universal constraint characteristic for life. Thus, the specific code used by life is traditionally considered as a “frozen accident”: something that might have ended up very differently, but which now no longer can be changed.

A less universal example of an emergent law is the grammar of a particular language, such as English. The rules of grammar constrain the sentences you can form in English. For example, they specify that an adjective, such as “universal”, must always be positioned before the noun to which it applies, as in “universal law”. In French, on the other hand, the standard position of an adjective is just after the noun, as in “loi universelle”. There is no law of physics (or even of psychology) that specifies that one position is either more or less natural than the other one. Nevertheless, if in a few centuries English would become the only language that is still spoken on Earth, people may find it difficult to imagine that you could ever form a sentence in which an adjective came after the noun. At that moment, the law of adjective positioning would have become truly universal, downwardly causing us, as components of the English-speaking community, to form sentences using just this specific word order.

Yet, that law, together with the other rules of English grammar and vocabulary, is in reality merely the outcome of a particular, contingent process of self-organization. That process of the emergence of a common language occurs when different individuals in a community mutually align the implicit norms they use to communicate their thoughts, until they settle on a common system of conventions that thus becomes universal within that community [

7,

32,

47].

In fact, a plausible explanation for the universality of the genetic code starts from a similar hypothesis [

46,

48]: early, bacteria-like organisms communicated by exchanging pieces of DNA (horizontal gene transfer). That allowed them to acquire useful genes from other organisms, something bacteria still do through the exchange of plasmids. But this would only have worked if they settled on the same language/code (transfer-RNA molecules) for interpreting these genes. Organisms using a different code would not have been able to interpret genes received in this way, and thus would have lost the competition with the others, unless they somehow aligned their code to the one of the majority.

11. The Emergence of Goals and Norms

As a last example of the emergence of laws, let us look at norms, goals and values. Physical and chemical systems are not goal-directed: they do not care about what happens to them. Biological systems, on the other hand, have been selected for survival, i.e. for safeguarding their metabolic network. As we saw, this network is a system of processes that consume and produce resources in such a way that the activity sustains itself. However, since the availability of external resources—such as food, water, or light—fluctuates, self-maintenance requires active intervention, in order to compensate for perturbations, such as shortfalls in certain resources or the occurrence of dangers, such as toxins, heat, or cold.

This propensity of a living system to counteract perturbations that make the system deviate from its regime of self-maintenance defines the system as

normative or

goal-directed [

6,

26,

49]. Such a goal-directed system distinguishes between “good” situations that satisfy its goal of continuing survival and that it will therefore act to attain, and “bad” situations that endanger its survival, and that it will therefore act to evade. Thus, all organisms have the emergent property of having goals, norms or values that direct their actions. These norms can be interpreted as internal laws, specifying which types of actions are allowed and which are not. While the goal of survival is universal for living systems, the concrete norms depend on the type of organism. For example, for herbivores a basic norm is to obtain sufficient plant material for food, for carnivores to catch prey, and for plants to get sufficient light, water and nutrients.

Animals living in groups tend to evolve additional norms that specify the interactions with other members of the group, in order to coordinate activities, promote cooperation, and avoid conflict. For humans, these norms about social interactions tend to become formalized in the shape of various ethical rules, rituals, conventions, institutions, and eventually laws—in the original, legal sense. Like all constraints, these laws restrict the range of allowable interactions. Yet, they too are the result of a contingent process of self-organization, as illustrated by the fact that different countries tend to have different laws for governing the same kinds of interactions—such as driving on the left-hand, respectively right-hand, side of the road.

Still, non-linear amplification tends to make these emergent constraints more universal and more rigid, so that it becomes increasingly difficult to deviate from the norm. As a result, social norms tend to become absolute, and to be interpreted as ordained by some goal-directed agent with absolute powers, such as a king, emperor or God. That in turn has inspired early scientists, such as Newton, to interpret the order found in Nature as similarly imposed by some intelligent designer, which some have conceived as “the Great Architect of the Universe”. That finally brings us full circle to the Newtonian worldview, in which everything that happens is supposed to be fully determined by the absolute and universal Laws of Nature, leaving no room for self-organization or emergence to create any novel order that obeys different laws.

From the perspective of complexity and evolution, on the other hand, the process of self-organization itself could be cast in the role of the designer or architect of the (incomplete) order we find in the universe. In that view, creation is an on-going process of the emergence of novel phenomena. The known laws of nature could then be interpreted either as purely mathematical truths (i.e. tautologies that must be true by definition) or as the outcome of some earlier, contingent process of self-organization (e.g. at the time of the Big Bang), during which one out of a range of possible constraints became universally fixed [

5]. A similar idea is proposed in the theory on the origin of time developed by Stephen Hawking and his collaborator Thomas Hertog [

50]. It sees the particular values of the fundamental physical constants, which determine the laws of nature, as the result of a series of “frozen accidents” that occurred during the very beginning of the universe, when space, time, particles and forces were still not separated and thus able to locally interact. These ideas about the ultimate origin are still quite speculative. Yet, I hope to have demonstrated that at least during more recent periods self-organization and the emergence of higher-level constraints and laws are common processes, which are able to explain a very wide range of complex phenomena.

12. Conclusion

This paper has examined the important but frequently misunderstood concept of emergence, trying to clarify the underlying assumptions and mechanisms. We have defined an emergent property as a property of a whole that cannot be reduced to the properties of its parts. This required an analysis of properties in general. We noted that a property of a system can be defined operationally as a relation between a particular type of input (“stimulus”) given to that system, and the corresponding output (reaction or “response”) of the system. A whole is created when different components are coupled together, by dependably linking their inputs and outputs in a particular manner. Therefore, the output of the whole for a given input will typically be different from the output of any of its parts in isolation. That means that the whole has different, emergent properties. For example, the particular coupling between the different components of an automobile is such that it can process an input of fuel into an output of forward motion, an ability that none of its parts has.

From a reductionist perspective, the output could still be predicted or explained from the properties of the parts if we know these properties and the precise manner in which the parts are coupled. However, we argued that the eventual coupling is typically the result of a process of self-organization in which different components randomly interact, until they settle into a stable coupling or “bond” with specific other components. These interactions cannot be predicted, neither in principle (because of quantum uncertainty), nor in practice (because of complexity and the butterfly effect). Therefore, the eventual outcome of the interaction, in terms of the particular stable arrangement or “attractor” reached, is not determined by the initial configuration of the parts. That means that it is effectively novel or emergent.

We then argued that this arrangement imposes an order or constraint on the parts: they have lost some of their freedom to act independently. This constraint can be interpreted as a “law”, which now governs the behavior of the parts (downward causation). We looked at the genetic code and the rules of grammar as examples of such higher-order laws that cannot be derived from the lower-level laws of physics and chemistry that govern their parts in isolation (upward causation). We also looked at the emergence of goals, norms and values that constrain the behavior of living and social systems. Here, norms on interaction between individuals may eventually consolidate into actual juridical or ethical rules or laws.

The overall conclusion is that emergence should not be seen as a mystical phenomenon outside the bounds of science, nor as an illusion, nor as an epiphenomenon that does not tell us anything new. The emergence of wholes with novel properties is not only real, it is a fundamental and natural process that can explain a wide range of both common and extraordinary phenomena, including, crystallization, magnetization, and the origins of life, language and goal-directedness. The mechanism underlying such emergence,

self-organization [

2,

25], is a conceptually simple process of components freely exploring different configurations, until they find one that is stable, i.e. where they settle in a relation of mutual adaptation or synergy. Still, the systems resulting from that process are unlimited in their complexity, because the process of evolution never stops, and systems continue interacting with other systems, potentially acquiring ever more diverse components, couplings, and capabilities.

Funding

This research was funded by the John Templeton Foundation as part of the project “The Origins of Goal-Directedness” (grant ID61733).

Acknowledgment

This paper is based on an invited lecture presented at the Science Week on Complexity, in the Ben Guerir campus of Mohammed VI Polytechnic University (UM6P) in 2023.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Halley, Julianne.D.; Winkler, D.A. Classification of Emergence and Its Relation to Self-Organization. Complexity 2008, 13, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heylighen, F. Complexity and Self-Organization. In Encyclopedia of Library and Information Sciences, Third Edition; Taylor & Francis, 2009; pp. 1215–1224. ISBN 0-8493-9712-X. [Google Scholar]

- Holland, J.H. Emergence: From Chaos To Order; Basic Books: Cambridge, Mass, 1999; ISBN 978-0-7382-0142-9. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, S. Emergence: The Connected Lives of Ants, Brains, Cities, and Software; Scribner: New York, 2001; ISBN 978-0-684-86875-2. [Google Scholar]

- Heylighen, F. The Self-Organization of Time and Causality: Steps Towards Understanding the Ultimate Origin. Found Sci 2010, 15, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heylighen, F.; Beigi, S.; Busseniers, E. The Role of Self-Maintaining Resilient Reaction Networks in the Origin and Evolution of Life. Biosystems 2022, 219, 104720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steels, L. The Emergence and Evolution of Linguistic Structure: From Lexical to Grammatical Communication Systems. Connection Science 2005, 17, 213–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jantsch, E. The Self-Organizing Universe: Scientific and Human Implications of the Emerging Paradigm of Evolution; Pergamon Pr, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Heylighen, F.; Cilliers, P.; Gershenson, C. Complexity and Philosophy. In Complexity, science and society; Bogg, J., Geyer, R., Eds.; Radcliffe Publishing: Oxford, 2007; pp. 117–134. ISBN 978-1-84619-203-6. [Google Scholar]

- Gershenson, C.; Heylighen, F. How Can We Think Complex? In Managing organizational complexity: philosophy, theory and application; Richardson, K., Ed.; Information Age Publishing, 2005; pp. 47–61. ISBN 978-1-59311-318-6. [Google Scholar]

- Laszlo, E. The Systems View of the World: A Holistic Vision for Our Time; 2nd edition; Hampton Pr: Cresskill, NJ, 1996; ISBN 978-1-57273-053-3. [Google Scholar]

- Corning, P.A. The Re-Emergence of “Emergence”: A Venerable Concept in Search of a Theory. Complexity 2002, 7, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heylighen, F. Emergence. In Elgar Encyclopedia of Complexity in the Social Sciences; Mitleton-Kelly, E., Ed.; Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd., 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Salt, G.W. A Comment on the Use of the Term Emergent Properties. The American Naturalist 1979, 113, 145–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, P.W. More Is Different. Science 1972, 177, 393–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Electric Dipole Moment. Wikipedia 2022.

- Aerts, D. Classical Theories and Nonclassical Theories as Special Cases of a More General Theory. Journal of Mathematical Physics 1983, 24, 2441–2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piron, C. Ideal Measurement and Probability in Quantum Mechanics. Erkenntnis (1975-) 1981, 16, 397–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heylighen, F. Complexity and Evolution: Fundamental Concepts of a New Scientific Worldview; Vrije Universiteit Brussel: Brussels, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Heylighen, F. (Meta)Systems as Constraints on Variation— a Classification and Natural History of Metasystem Transitions. World Futures 1995, 45, 59–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centler, F.; di Fenizio, P.S.; Matsumaru, N.; Dittrich, P. Chemical Organizations in the Central Sugar Metabolism of Escherichia Coli. In Mathematical Modeling of Biological Systems, Volume I; Springer, 2007; pp. 105–119. [Google Scholar]

- Heylighen, F. Principles of Systems and Cybernetics: An Evolutionary Perspective. Cybernetics and Systems’ 92 1992, 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Corning, P.A. Synergy and Self-Organization in the Evolution of Complex Systems. Systems Research 1995, 12, 89–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashby, W.R. Principles of the Self-Organizing System. In Principles of Self-Organization; von Foerster, H., Zopf, G.W., Eds.; Pergamon Press, 1962; pp. 255–278. [Google Scholar]

- Heylighen, F. The Science of Self-Organization and Adaptivity. In The Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems; EOLSS Publishers Co Ltd, 2001; Vol. 5, pp. 253–280. ISBN 978-1-84826-913-2. [Google Scholar]

- Heylighen, F. The Meaning and Origin of Goal-Directedness: A Dynamical Systems Perspective. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 2023, 139, 370–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternberg, S. Dynamical Systems; Courier Corporation, 2010; ISBN 978-0-486-47705-3. [Google Scholar]

- Milnor, J.W. Attractor. Scholarpedia 2006, 1, 1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heylighen, F. Self-Organization, Emergence and the Architecture of Complexity. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 1st European conference on System Science, 1989; pp. 23–32. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, H.A. The Architecture of Complexity. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 1962, 106, 467–482. [Google Scholar]

- Henrich, J.; Boyd, R. The Evolution of Conformist Transmission and the Emergence of Between-Group Differences. Evolution and Human Behavior 1998, 19, 215–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heylighen, F. Self-Organization in Communicating Groups: The Emergence of Coordination, Shared References and Collective Intelligence. In Complexity Perspectives on Language, Communication and Society;Understanding Complex Systems; Massip-Bonet, À., Bastardas-Boada, A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2013; pp. 117–149. ISBN 978-3-642-32816-9. [Google Scholar]

- Pickering, M.J.; Garrod, S. The Interactive-Alignment Model: Developments and Refinements. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 2004, 27, 212–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroud, J.T.; Losos, J.B. Ecological Opportunity and Adaptive Radiation. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 2016, 47, 507–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heylighen, F. Relational Agency: A New Ontology for Co-Evolving Systems. In Evolution ‘On Purpose’: Teleonomy in Living Systems;Vienna Series in Theoretical Biology; Corning, P., Kauffman, S.A., Noble, D., Shapi, J.A., Vane-Wright, R.I., Pross, A., Eds.; MIT Press, 2023; pp. 79–104. [Google Scholar]

- Veloz, T. The Complexity–Stability Debate, Chemical Organization Theory, and the Identification of Non-Classical Structures in Ecology. Found Sci 2019, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dittrich, P.; Fenizio, P.S. di Chemical Organisation Theory. Bull. Math. Biol. 2007, 69, 1199–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilborn, R.C. Sea Gulls, Butterflies, and Grasshoppers: A Brief History of the Butterfly Effect in Nonlinear Dynamics. American Journal of Physics 2004, 72, 425–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckage, B.; Gross, L.J.; Kauffman, S. The Limits to Prediction in Ecological Systems. Ecosphere 2011, 2, art125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatti, R.C.; Hordijk, W.; Kauffman, S. Biodiversity Is Autocatalytic. Ecological Modelling 2017, 346, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heylighen, F.; Beigi, S.; Vidal, C.

The Third Story of the Universe: An Evolutionary Worldview for the Noosphere

. CLEA/Human Energy 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bedau, M. Downward Causation and the Autonomy of Weak Emergence. Principia 2002, 6, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, D.T. ‘Downward Causation’in Hierarchically Organised Biological Systems. In Studies in the Philosophy of Biology; Springer, 1974; pp. 179–186. [Google Scholar]

- Heylighen, F. Modelling Emergence. World Futures 1991, 32, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, B. The Reemergence of ‘Emergence. Philosophy of Science 2001, 68, S62–S75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koonin, E.V.; Novozhilov, A.S. Origin and Evolution of the Universal Genetic Code. Annual Review of Genetics 2017, 51, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrod, S.; Doherty, G. Conversation, Co-Ordination and Convention: An Empirical Investigation of How Groups Establish Linguistic Conventions. Cognition 1994, 53, 181–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froese, T.; Campos, J.I.; Fujishima, K.; Kiga, D.; Virgo, N. Horizontal Transfer of Code Fragments between Protocells Can Explain the Origins of the Genetic Code without Vertical Descent. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 3532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, A.; Mossio, M. Teleology, Normativity and Functionality. In Biological Autonomy: A Philosophical and Theoretical Enquiry;History, Philosophy and Theory of the Life Sciences; Moreno, A., Mossio, M., Eds.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 2015; pp. 63–87. ISBN 978-94-017-9837-2. [Google Scholar]

- Hertog, T. On the Origin of Time: Stephen Hawking’s Final Theory; Bantam: New York, 2023; ISBN 978-0-593-12844-2. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).