1. Introduction

Pathologies of the mammary gland usually led to loss of milk production, which decreases the economic value of the animals involved [

1], and may lead to their premature culling [

2].

In small ruminants, teat wounds are more common than in cattle [

3], above all in those animals whose very large udders predispose themselves to trauma [

4].

Teat fistula could be the consequence of deep traumas or could be a negative outcome of previous surgery; sometimes, it could have a congenital origin [

5]. Nevertheless, teat fistulas do not occur often in ewes [

6].

Obstructions of the milk ejection in “hard milkers” may be due to teat spiders, milk stones, bacterial thelitis, traumas, frost injury, malfunctioning of the milking machines or genetic inheritance [

3].

Hyperthelia, or supernumerary teats, is a congenital condition of ancillary teats in addition to the primary teats [

7], and its percentage can reach 64.92% in ewes and 30.72% in does [

1].

Skin neoplasms of the teat and the udder are quite common, especially in breeds with depigmented skin that are reared in areas largely exposed to UV rays [

8]. The majority of these lesions are represented by papilloma, fibropapillomas and squamous cell carcinomas [

9].

On the other hand, many udder diseases are characterized by severe and irreversible impairment of organ functions, such as suppurative or gangrenous mastitis [

10,

11], chronic sclerosing mastitis [

12], pendulous udder, parenchymal neoplasms, inappropriate lactation syndrome [

13,

14], gynecomastia in bucks [

3,

15,

16]. Thus, affected animals could represent good candidates for surgery.

Anatomy

In small ruminants, teat’s wall consists of the skin, a large intermediate layer (mainly represented of connective tissue, smooth muscle and numerous large blood vessels), a very thin submucosa, and a mucosa which is composed of two floors of cuboidal epithelium [

17]. The orifice (

ostium papillae) located at the distal end of the teat is internally communicating with the teat duct (

ductus papillaris), then follows the teat cistern (

sinus papillaris); this latter is empirically separated from the gland cistern of the relative udder by an annular ring, which contains a large vein that encircles the base of the teat [

6,

18].

Each half udder in small ruminants is formed by the skin, the subcutis, the superficial fascia, an area under this fascia (rich in blood vessels, nerves and lymph vessels), the internal fascia and the mammary parenchyma [

18]. Each half of the udder is supplied mainly by the external pudendal artery, that emerges from the inguinal ring and gives a number of branches to the udder and continues cranially as the superficial cranial epigastric artery. At the same time, each half of the udder is drained by a circular venous plexus, which derives mainly from the external pudendal, the subcutaneous abdominal and the perineal veins (

Figure 1a-c). The relatively poor blood supply of the small ruminant udder, together with the scarcity of anastomoses, are considered to be predisposing factors for gangrenous mastitis in sheep and goats [

19].

The cranial part of the udder is innervated by the ventral rami of iliohypogastric and the ilioinguinal nerves, while the caudal part is innervated by the pudendal nerve [

3].

Although most of the knowledge of mammary gland and teat surgery regards the bovine [

17], surgical treatments are also often applicable in small ruminants and aim to salvage the integrity and the function of the teats and mammary glands, especially in pets and in valuable animals. However, there are several gaps in knowledge for some surgical injuries, and their prognosis, management, and long-term follow-up in sheep and goats, such as teat and udder skin cancers or the curettage of unilateral and bilateral streak canal stenosis.

This article describes the on-farm surgical procedures and outcome of teat and udder lesions in dairy small ruminants reared in Sicily (Italy). The surgeries here described were performed for free with a double aim: (i) to increase data on small ruminant surgery; (ii) to collect skin neoplasms for further investigations.

2. Materials and Methods

Treatment involved 135 cases in 129 animals. Precisely, 19 repairs of teat wounds, 2 repairs of fistulas, 26 curettages of the teat cistern and of their orifices, 5 thelectomy (teat amputations), 14 removals of neoplasms from the teat skin, 67 removals of neoplasms from the udder skin, and 2 mastectomies are discussed (

Table 1).

For all these interventions, sedation, anesthesia, surgical field preparation, surgery and post-operative management are described in each section. Usually, the animals were manually and adequately restrained by the owners in lateral recumbency or standing position.

Throughout the surgery, respiratory and heart rates, and when appropriate non-invasive systolic pressure by a multi-parameter monitor (Leonardo model, AMI Italia srl, Milano, Italy) were monitored; any variation equal or more than 20% of the normal values was considered animal discomfort.

2.1. Repair of Teat Wounds

Seventeen ewes and 2 does were treated. The wounds were consequent to traumas (i.e. bites, cuts) and had different shapes and sizes. Only lesions penetrating through the wall and into the teat sinus were selected for this study. When the orifice was involved, surgery was excluded due to the very poor prognosis. The surgery was performed within 24 hours from the injury, but, when possible, the owner started the antibiotic and NSAID therapy also before the intervention. The animals were adequately restrained, the area was disinfected with a chlorhexidine-based disinfectant and a ring block infiltration with 2-6 ml of lidocaine 2% around the teat base was performed. The teat was clamped at its base by Kelly forceps or by a simple or double overhand knot with a strip of gauze bandage, and a sterile plastic cannula was inserted inside the streak canal before suturing (

Figure 2a). A continuous, non-penetrating suture of the mucosa and of the submucosa, using a round-bodied needle and a 3-0 or 4-0 polydioxanone suture (PDS) was used, followed by a simple interrupted suture of the muscle and of the skin, using a triangular needle and a 1-0 or 2-0 PDS (

Figure 2b). Animals were gently milked once a day, whilst the cannula was replaced every 48 hours. Postoperative care included 2 grams of dihydrostreptomycin associated with 2 million IU of penicillin G procaine (IM, once a day -OD-, for 6 days), and 10 mg of flunixin meglumine (IM, repeated after 12 hours when necessary).

2.2. Repair of Fistulas

Two ewes, one with congenital fistula and one with acquired fistula (due to a non-treated wound) underwent surgery. Both lesions were located at the wall of the teat. The animals were adequately restrained, and the area was disinfected with a chlorhexidine-based disinfectant. Local anesthesia by 2 ml of lidocaine, using an inverted 'V' block infiltration, was performed. The teat was clamped with Kelly forceps and thereafter, a sterile plastic disposable cannula was introduced into the orifice. A thin probe was introduced inside the fistula to facilitate dissection, and, around it, a small elliptical full thickness incision was carried out. The sutures and the postoperative care were the same as the teat wound repairs.

2.3. Curettage of the Teat Cistern and of the Orifice

Twenty-two ewes with contracted sphincter, called “hard milkers”, were treated. Lesions were unilateral in 18 animals, and bilateral in 4. The lesions were represented by partial stenosis of the teat sinus, but in the bilateral lesions the teats orifice seemed more affected than the sinus. The animals were adequately restrained, and the teat orifice was disinfected with a chlorhexidine-based disinfectant. When necessary, the teat was emptied and desensitized with an intraluminal injection of 1-2 ml of lidocaine 2%, simultaneously applying a finger pressure around the teat base for few minutes. After that, a lubricated and disinfected Hug teat punch - Ø 2-4 mm (Erbrich Instrumente GmbH, Tuttlingen - DE) to remove debris was introduced. In 5 cases with unilateral lesions, 12 and 24 hours later, a new intervention to obtain an optimum milk flow was necessary. After each treatment, 0.1-0.2 g (1/3 or 2/3 of tube) of cloxacillin benzathine of an intraluminal antibiotic suspension were inoculated and a sterile plastic cannula was inserted.

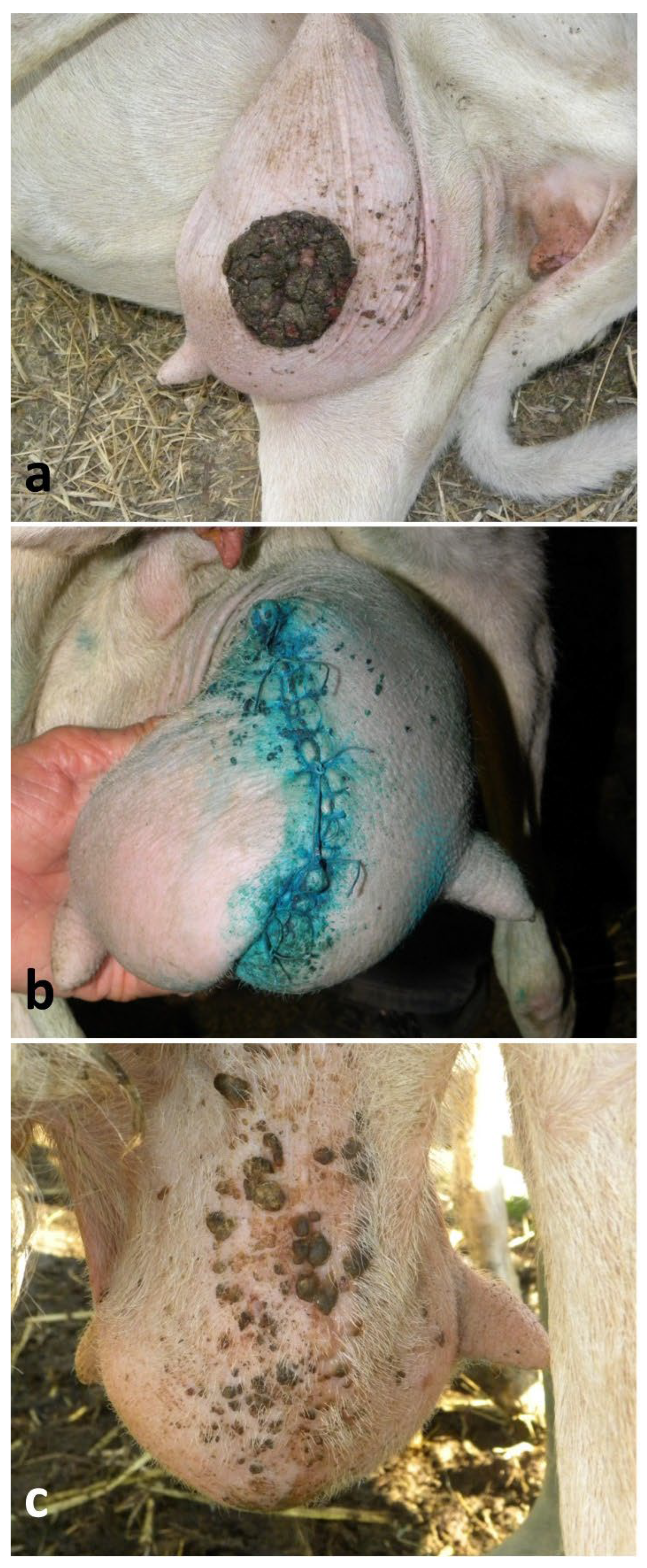

2.4. Thelectomy

One lactating ewe and one young goat, both bilaterally affected by supernumerary teats, and one lactating ewe with a neoplasm complicated by myiasis at the teat orifice, were treated. The animals were adequately restrained, and the area was disinfected with a chlorhexidine-based disinfectant. The gland was emptied and treated with 0.3 g of cloxacillin benzathine of intraluminal antibiotic. A ring block infiltration with 4-6 ml of lidocaine 2% around the teat base was performed, forceps were applied at the base of the teat and the dissection was performed by using an electrosurgical unit (KLS Martin ME MB 2, KLS Martin Group, Tuttlingen - DE). Leaving the forceps in place, two layers of suturing were applied. One included the mucosa and submucosa, and it was a continuous, inverting and non-penetrating suture with 2-0 PDS; instead, the muscle and the skin were closed using a simple interrupted pattern with 0 PDS (

Figure 3a-c). The postoperative care was the same as teat wound repairs.

2.5. Removal of Neoplasms from the Teat Skin

Fourteen ewes were treated. The animals were adequately restrained, the area was disinfected with a chlorhexidine-based disinfectant, and a cannula was introduced into the teat. Anesthesia was performed by injecting 4-8 ml of lidocaine 2% approx. 5-10 mm beside and externally the incision line, and the teat was clamped at its base. In some cases, the dissection and tumor removal were performed using a scalpel blade; while in the other cases, an electrosurgical spatula blade was used. The subcutis was sutured with continuous suture pattern by using a 3-0 PDS, while the skin was sutured with a simple interrupted suture, by using a 2-0 or 1-0 PDS (

Figure 4a-e). The postoperative care was the same as the teat wound repairs.

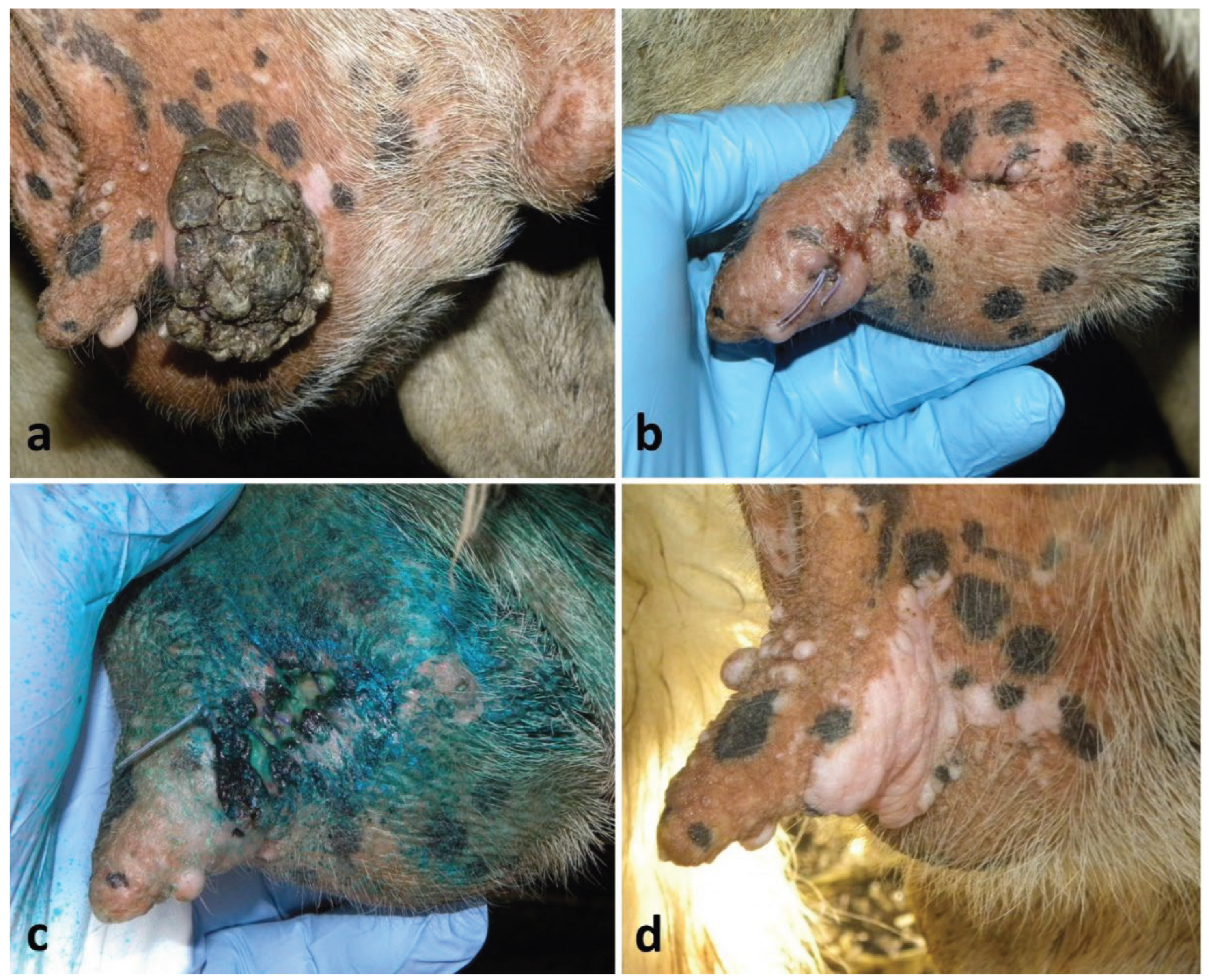

2.6. Removal of Skin Neoplasms from the Udder

Sixty-seven ewes underwent surgery. In most of the animals, the lesions were located on the caudal aspect of the udder. The animals were adequately restrained, the area was disinfected with a chlorhexidine-based disinfectant and desensitized by using 10-30 ml of lidocaine 2%, approximatively 1-3 cm far from the incision and into the subcutaneous tissue under the neoplasm. The skin was incised with a scalpel blade all around the tumor, drawing an ellipse encompassing approximately 1-2 cm from the outer portion of the lesion, while the subcutis was dissected by using Mayo scissors; blunt dissection was usually preferred to minimize intraoperative hemorrhage. Vessels were identified, clamped and ligated if necessary. The subcutis was closed with a simple running suture (overlock) by using a 2-0 or 1-0 PDS. The skin was closed either via continuous suture by using a 1-0 or 0 PDS in 45 animals, or a simple interrupted suture by using a 0 PDS in the other 22 animals (

Figure 5a-d). The postoperative care was the same as the teat wound repairs, but the flunixin meglumine administration lasted 3 days.

2.7. Mastectomies

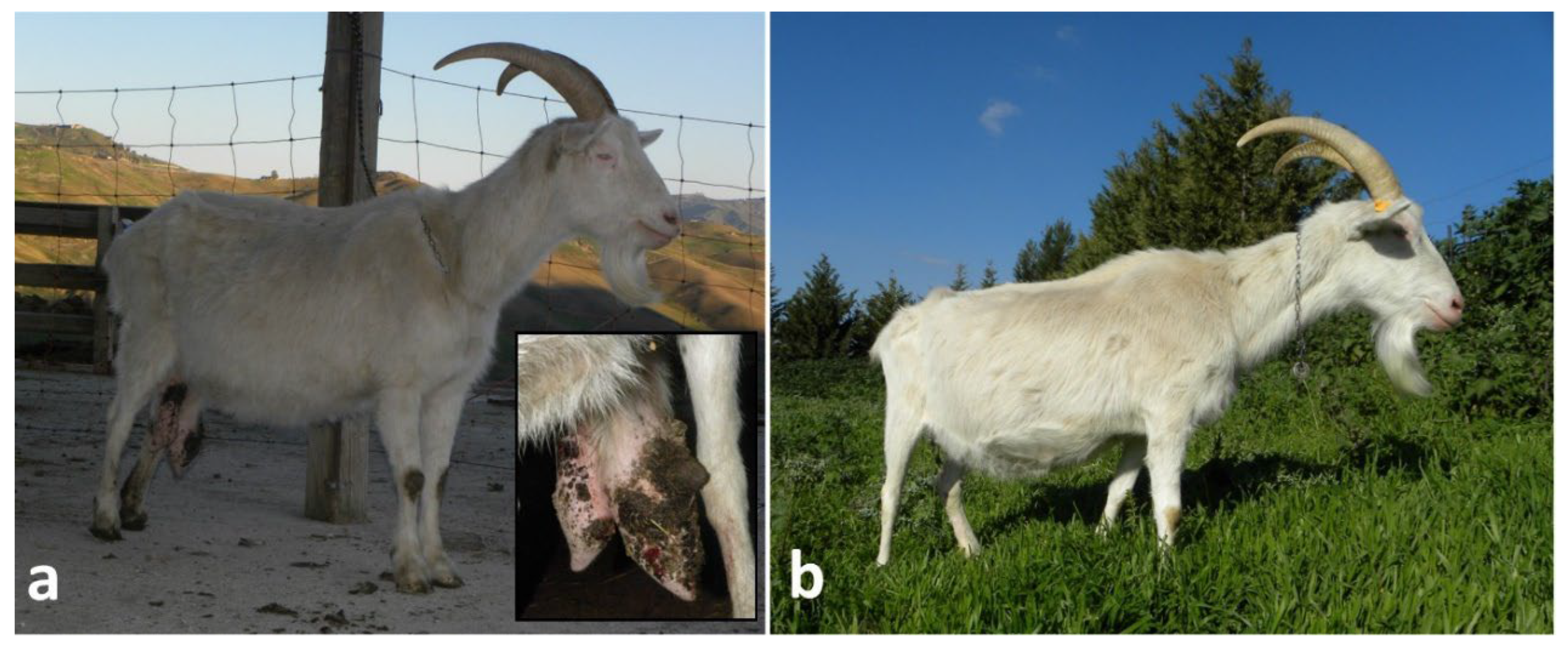

Two pluriparous Saanen does affected by severe and diffuse cutaneous neoplasms on the udder (

Figure 6a) underwent mastectomy. Each animal was withheld feed and water for 24 hours and 12 hours, respectively, before the surgery. Sedation was obtained by administering 2 mg/kg IM of tiletamine/zolazepam, associated with 0,05 mg/kg IM of xylazine 2%. They were placed in right lateral recumbency and firmly restrained as in the "horse castration" position (upper hind limb pulled cranially), and an IV catheter was placed. The udder was disinfected with a chlorhexidine-based disinfectant. About 20 ml of anesthetic solution containing 15 ml of lidocaine 2% previously mixed with 5 ml of physiological saline solution were injected in both the ischiorectal fossae (10 ml each side); while at the base of the udder, in proximity of the supramammary lymph nodes and along the incision line, 50 ml of anesthetic solution, containing 35 ml of lidocaine 2% previously mixed with 15 ml of physiological solution were deposited. The surgical field was prepared according to the procedure and the udder was put in a disposable rectal examination glove. The skin was incised at about 4-5 cm below the dorsal edge of the udder, extending the incision line through the lateral suspensory ligament in an elliptic manner. Therefore, two skins flaps (one on each side) were created. Both the external pudendal arteries and veins were identified and ligated. The entire half-udder was isolated from the abdominal wall by an electrosurgical spatula blade while all the vessels of medium and large caliber were isolated and ligated. The same procedure was applied to the contralateral gland, and the organ was removed along with the respective lymph nodes. The subcutis was closed by using a simple running suture with a 2-0 PDS, while the skin was sutured via a continuous interlocking suture and simple reinforcement knots by using a 0 PDS. Simple knots were applied to obliterate dead spaces and subcutaneous pockets, especially proximally the external inguinal ring. A passive drainage was inserted at the most ventral aspect of the dead space.

During the surgery, discomfort in both patients was observed, and 1 mg/kg of tramadol IV was administered. Postoperative care included 2 grams of dihydrostreptomycin and 2 million UI of penicillin G procaine (IM, OD, for 10 days), associated with 10 mg of flunixin meglumine (IM, OD, repeated for 3 days). Moreover, the surgical wound was treated with tetracyclines spray for 7 days.

The following-up of all the cases was obtained via telephone interview or with clinical examination during the on-farm referral which was spread from six months to over two years.

3. Results

For the 19 reconstructions of teat lacerations, a primary intention healing of 13 (68%) cases and a secondary intention healing of 4 (21%) cases were observed. Overall, good we healing was already appreciated on the 7th day post-intervention; in cases where the trauma involved the distal portion of the teat, but the orifice was intact, the functional integrity of the organ was always preserved (

Figure 2c). The 4 cases resolved by secondary intention required additional 10-14 days to obtain the same degree of healing. Two (11%) animals suffered dehiscence, thelitis and mastitis.

The two (100%) sheep treated for fistula showed the same postoperative fate of the teat lacerations with a primary intention healing.

On 26 teat curettages, all 18 (69%) unilateral lesions were successfully resolved, even though in 5 cases a new intervention was necessary showing then a mild to moderate local teat inflammation. Opposite, all 8 (31%) teats of the 4 ewes with bilateral lesions showed a poor outcome; in these 4 animals, a primary resolution was obtained only in one case, while for the other 3 it was necessary to repeat the intervention at 12, 24 and 36 hours after. All 4 animals showed a relapse within six months and in two of them a total bilateral obliteration of the treated teats at the next lactation was observed.

Thelectomy showed a complete resolution on the 18th day (± 4 days) (

Figure 3d) after the surgical removal of all 5 (100%) teats.

Treatments of the 14 (100%) teat neoplastic lesions achieved great results in their healing process already on the 7th day and a complete healing on the 21st day (

Figure 4f), but this depended on the shape and size of the wound.

Regarding the removal of the 67 neoplastic lesions of the udder skin, 59 (88%) of them showed primary intention healing, and the healing times ranged between 17 and 26 days (

Figure 7a-c). However, the continuous sutures showed greater traction than the simple interrupted ones, and teats showed a permanent slight curvature as result. The healing depended on the extension of the surgical wound, but above all, on the owner’s compliance. Indeed, in 8 (12%) cases the animals were not correctly treated with antibiotics during the post-operative care, showing wound inflammation on the 2nd day, and suppuration and dehiscence on the 5th-7th day and healing by secondary intention with extended scar (

Figure 8a-d); 2 of them suffered mastitis.

Regarding the mastectomies, the follow-up was evaluated daily. In the days following surgery, moderate subcutaneous oedema and discharges through the drainage points were observed. The drainage was removed 1 week post-surgery. The suture and the surrounding skin were slightly swollen and painful and ketoprofen-based ointment - 25 mg/g (Fastum gel® - Menarini, Firenze) in derogation was applicated. Fourteen days after, a suppurative focus in the anchor point from which flowed a mild amount of smelly pus lasting approx. 1 week was observed in a doe. Thirty-eight days after the intervention (± 6 days), the follow-up revealed a complete healing of the suture in both animals (

Figure 6b).

4. Discussion

With the increasing culture of small ruminants being kept as pets, veterinarians are facing new diagnostic and treatment challenges that go beyond the traditional health management of the conventional food animal species kept for commercial purpose [

20]. Moreover, many pathological conditions affecting the teat and the udder can result in chronic poor health, negative impact of both animal welfare and production, and should require effective surgical treatments to eliminate the associated discomfort and pain [

14,

20].

Teats are prone to various degrees of injuries because of direct trauma, particularly at the end of gestation and the start of lactation mainly in dairy breeds [

14]. This reduces its ability to function efficiently, and predisposes to teat fistulae, mastitis, or sloughing of the udder [

2]. Although non-penetrating teat lacerations often do not require suturing, the full-thickness ones should be sutured since their surgical treatment is associated with good prognosis [

2]. However, complications such as the delay in the healing process and fistula formation may be recorded. The success in most of the cases in this study was attributed to the fact that wounds were usually treated within 24 hours, adequate medical therapy was administered as soon as possible, and because only the cases without orifice involved were selected for surgeries. Similarly, the good outcome of the fistula repair cases included in this work (although only 2 cases) was likely also achieved by the plannability of the intervention and the fact that the wound margins were neat and without loss of tissue. On the other hand, in the rest of the cases, the poor outcome of teat surgery was likely caused by lack of owner compliance.

Regarding teat stenotic lesions in “hard milkers”, the good outcome of the unilateral lesions was referred to the presence of intraluminal small fibrotic septa only, without any damage of the orifice; on the other hand, the bilateral lesions might have had a poor outcome due to the damage of their orifices, moreover they could have a genetic cause. This consideration is also supported by Couture and Mulon [

21], who observed that injuries to the end of the teat are frustrating to approach, and management of these injuries evolved from being too aggressive when using teat knives rather than employing a more conservative approach, such as nonreactive teat inserts.

Hyperthelia directly influences mammary health. In does with triplets, the third kid may suckle the non-functional teat with consequent predisposition to mastitis, moreover, the supernumerary teat/s could hamper the milking [

7]. In dairy farms, supernumerary teats are often removed in young animals; however, the average frequency of infection has been found to be 4.3% in sheep and 29.7% in goats after this surgery [

22]. The thelectomies reported in this study were not performed for aesthetic reasons, and in all cases have had a good prognosis, as also observed by Edler and Grunert [

23], who reported an outcome of 94.6% in 204 teat goat amputations.

Neoplastic lesions on the skin are quite common and are reported both in sheep [

9] and goat [

24,

25]. The majority of cutaneous tumors in sheep are squamous cell carcinoma [

26], and the udder is a common site where this neoplasm develops [

9]. The outcome here observed was good, but it is supposed that a good use of a disposable cannula helps to reach good results when the surgery involves the teat. Moreover, simple interrupted sutures are more indicated for surgeries near the teat and its base, due to the excessive traction that continuous sutures may exercise.

Mastectomy is a salvage procedure indicated in many cases, especially in animals with high economic value, at the end of pregnancy, raised as pet, or used as embryo donors [

14,

20,

27]. Although El-Maghraby [

19] reported that vascular ligation and teat amputation proved to be less traumatic and required less time, effort and expense compared to the classical radical mastectomy, in cases similar to those here reported, where a large area of skin udder is involved, radical mastectomy must be taken into consideration. Even though some authors [

14] recommend creating four semielliptical skin incisions (inverted cloverleaf technique) could better preserve more tissue to reduce excessive skin tension during the closure and consequent dead space formation, in both the cases here described this was not possible because the diffuse presence of cutaneous neoplasm, and the opted alternative was an elliptical incision technique, as also observed in similar cases [

20].

The evaluation of intraoperative pain is fundamental and ethically necessary. However, in some field interventions this practice is difficult to implement and requires the presence of trained professionals [

28].

Local anesthetics represent the choice for the most operative interventions in ruminants because they do not influence the forestomachal motility [

29]. Nevertheless, in some cases the use of general anesthesia is essential, and the association of an alpha2-adrenergic agonists and dissociative drugs, used here for the sedation of the goats which underwent mastectomy, is also widespread in field anesthesia in small ruminants [

6,

28]. The tramadol used here represented a good choice as a rescue analgesic drug because it has little influence on both forestomachal motility and the cardiovascular system [

29,

30]. Moreover, contrary to the commonly used local anesthetics, tramadol has a quick onset time and a strong efficacy in acid inflamed environment, and it is excreted almost entirely with feces and urine [

29]. On the other hand, the reason why local anesthesia was performed in the does by mixing physiological solution is because lidocaine 2% can be toxic in this species if used at high doses [

31].

Nevertheless, when a surgical procedure is not urgent and a long duration of the surgery is expected, ruminants must be fasted 24 hours prior to minimizing forestomachal distention and risk of regurgitation during the procedure [

19,

20].

5. Conclusions

To conclude, repair of teat lacerations and teat amputation after traumatisms represent urgent interventions that must be properly carried out, but they are not particularly challenging and do not require deep anatomic and surgical knowledge or a complex surgical set, although basic surgical principles must be applied. Moreover, aesthetics or functional thelectomy or skin neoplasm removals are simple and plannable. In case of bilateral stenotic lesions of the canal the practitioner should avoid overtreatment and should discourage the farmers from rearing their offspring. Mastectomy requires more technical knowledge but, apart from cases of acute mastitis, it is also often programmable, thus, predisposing the surgery to a good outcome too.

For all these interventions, the owner should be educated and made aware that the animal can often return to production and that these injuries can be treated at a reasonable cost. Indeed, although the interventions here described were performed for free, usually the practitioners perform the majority of these surgeries during their routine flock health plans and the costs applied (mastectomies excluded) are between 10€ and 40€.

Finally, the post-operative treatments performed by the owner are the key to a successful intervention regardless of the lesion and the type of surgical technique used.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.A.M.; methodology, S.A.M., M.C., M.M., G.L.C.; software, S.A.M., B.A.; validation, S.A.M., B.A., M.C., M.M., G.L.C.; formal analysis, S.A.M., B.A.; investigation, S.A.M., M.C., M.M., G.L.C.; resources, S.A.M., M.C., M.M., G.L.C.; data curation, S.A.M.; writing—original draft preparation, S.A.M.; writing—review and editing, S.A.M., M.M.; visualization, S.A.M., B.A., M.C., M.M., G.L.C.; supervision, S.A.M., M.M.; project administration, S.A.M., M.M.; funding acquisition, S.A.M., M.M., G.L.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

In memory of Prof. Marcello Musico’, a mentor to hundreds of VM and PhD students. Goodbye dear Marcello, we will always remember you with that nice and ironic smile on you. Thank you!

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Awad, M.; Ahmed, I.; El-Hamamy, M.; Mohammed, M. Survey on surgical affections of udder and teats in small ruminants in Ismailia and North Sinai governorates. Suez Canal Veterinary Medicine Journal 2008, 13, 223–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seddek, A.M.; Abedellaah, B.; Awaad, A.S.; Bakr, H.A. Treatment of irreparable full-thickness teat laceration in goats by connecting gland cisterns. Indian J Vet Surg 2013, 34, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Plummer, P.J.; Still Brooks, K.M.; Edmondson, M.A. Diseases of mammary gland. In Sheep, Goat, and Cervid Medicine, 3rd ed.; Pugh, D.G., Baird, A.N., Edmondson, M.A., et al., Eds.; Elsevier Saunders: Philadelphia (PA), 2020; pp. 1063–1075. [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier, J.F. Teat surgery in sheep and goat. Summa Suppl 2002, 1, 62. [Google Scholar]

- Amstutz, F. Teat surgery in goat. Mod Vet Pract 1978, 59, 674–677. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tsioli, V.; Fthenakis, G.C. Udder surgery in ewes. Small Rum Res 2019, 181, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raheem, K.A.; Leigh, O.O. Supernumenary teat in West Africa dwarf goat in Ibadan, Southwest Nigeria. J Agric Vet Sci 2014, 7, 60–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puleio, R.; Capucchio, M.T.; Tamburello, A.; Mignacca, S.A.; Atanasio, A.; Vitale, M.; Amato, B.; Loria, G.R.; Di Marco Lo Presti, V. Ocular squamous cell carcinoma in Valle del Belice sheep: histology and immunohistochemistry. Small Rum Res 2015, 126, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Hassanein, K. Ovine and caprine cutaneous and ocular neoplasms. Small Rum Res 2012, 106, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgos, F.; Almeida, E. Radical and unilateral mastectomy as treatment of choice for gangrenous mastitis in goats. Med Vet 2013, 7, 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Dar, M.; Dar, K.H.; Dar, S.H.; Naikoo, M. Unilateral mastectomy for fibrotic udder and moist gangrenous lacerated teat in a goat. Indian Vet J 2015, 92, 63–65. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A.; Mahajan, S.K.; Singh, K.; Sangman, V.; Chandra, M.; Saini, N.S.; Anand, A. Unilateral mastectomy for the management of chronic suppurative mastitis in a goat. Indian J Small Ruminants 2012, 18, 148–151. [Google Scholar]

- Arlt, S.; Reinecke, A.; Drillich, M.; Fischer-Tenhagen, C.; Heuwieser, W. Mastectomy in goats with inappropriate lactation syndrome. Tierärztliche Praxis Großtiere 2011, 1, 27–32. [Google Scholar]

- Hermida, J.A.; Baird, A.N.; Hawkins, J.F.; Moore, G.E. Mastectomy in 25 small ruminants (2002–2019). Vet Surg 2021, 50, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wooldridge, A.A.; Gill, M.S.; Lemarchand, T.; Eilts, B.; Taylor, H.W.; Otterson, T. Gynecomastia and mammary gland adenocarcinoma in a Nubian buck. Can Vet J 1999, 40, 663–665. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pilo, C.; Cannas, E.A.; Coghe, F.; Dore, S.; Liciardi, M. Gynaecomastia and galactorrhea in goat buck. Large Anim Rev 2011, 17, 23–26. [Google Scholar]

- Steiner, A. Teat surgery in dairy cow. Large Anim Rev 2008, 1, 27–29. [Google Scholar]

- Barone, R. Udder. In Comparative anatomy of domestic animals, 4th ed.; Barone, R., Ed.; Edizioni Edagricole: Milano (IT), 2009; pp. 365–409. [Google Scholar]

- El-Maghraby, H.M. Comparison of two surgical techniques for mastectomy of goats. Small Rum Res 2001, 40, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rok, M.; Starič, J.; Geč, L.V.; Klinc, P. Total mastectomy in severe necrotic mastitis in a pet goat complicated by a post-operative generalized emphysema. Vet Rec Case Rep 2024, 12, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couture, Y.; Mulon, P.Y. Procedures and surgeries of the teat. Vet Clin North Am Food Anim Pract 2005, 21, 173–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palacios, C.; Abecia, J.A. Supernumerary teat removal can be avoided in dairy sheep. J Appl Anim Welf Sci 2014, 17, 178–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edler, B.; Grunert, E. Teat amputation in goat - indications, surgical results and economy. Berl Munch Tierarztl Wochenschr 1994, 107, 397–400. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Löhr, C. One hundred two tumors in 100 goats (1987-2011). Vet Pathol 2012, 50, 668–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mignacca, S.A.; Agnello, S.; Castiglione, S.; Guercio, A.; Purpari, G.; Capucchio, M.T. Malignant skin neoplasms in goats in Sicily, Italy: clinical, virological and pathological investigations. J Comp Pathol 2024, 213, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastianello, S.S. A survey on neoplasia in domestic species over a 40-year period from 1935 to 1974 in the Republic of South Africa. II. Tumours occurring in sheep. Onderstepoort J Vet Res 1982, 49, 205–209. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cable, C.; Peery, K.; Fubini, S. Radical mastectomy in 20 ruminants. Vet Sur 2004, 33, 263–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, G.; Musicò, M.; Spadola, F.; Oliveri, M.; Leonard, F.; Interlandi, C. Comparison of tiletamine/zolazepam combined with dexmedetomidine or xylazine for chemical immobilization of wild fallow deer (Dama dama). J Zoo Wildlife Med 2021, 52, 1009–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, G.; Musicò, M.; Spadola, F.; Cortigiani, S.; Leonardi, F.; Cucinotta, G.; Interlandi, C. Effects of tramadol slow injection vs fast bolus in the therapeutic balance of the foot in bovine. Large Anim Rev 2018, 24, 219–221. [Google Scholar]

- Interlandi, C.; Nastasi, B.; Morici, M.; Calabrò, P.; Costa, G.L. Effects of the combination romifidine/tramadol drugs administration on several physiological and behavioral variables in calves. Large Anim Rev 2017, 23, 51–54. [Google Scholar]

- Casamitjana, P. Anesthesia in small ruminants. Summa Suppl 2001, 1, 17. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1.

Anatomy of the udder and the teat in an ovine cadaver: (a) specimen showing the anatomical connections between the mammary gland and the abdominal wall, including the mammary lymph-node (*), the overturned mammary gland (*), the mammary artery and vein (*), and the subcutaneous abdominal veins (**); (b) longitudinal opening of the teat showing the teat duct (*), the teat cistern (*), the annular ring (*), and the gland cistern (*); (c) dorsal view from the gland cistern showing the annular ring (arrow) and the underneath teat cistern.

Figure 1.

Anatomy of the udder and the teat in an ovine cadaver: (a) specimen showing the anatomical connections between the mammary gland and the abdominal wall, including the mammary lymph-node (*), the overturned mammary gland (*), the mammary artery and vein (*), and the subcutaneous abdominal veins (**); (b) longitudinal opening of the teat showing the teat duct (*), the teat cistern (*), the annular ring (*), and the gland cistern (*); (c) dorsal view from the gland cistern showing the annular ring (arrow) and the underneath teat cistern.

Figure 2.

Repair of teat wound in a lactating ewe: (a) recent, semi-circular and penetrating teat wound with a teat cannula inserted; (b) closure completed by a simple interrupted suture of the muscle and of the skin (the underneath suture of the mucosa and submucosa is not shown); (c) outcome after 6 months with healed wound and complete resolution of the functions.

Figure 2.

Repair of teat wound in a lactating ewe: (a) recent, semi-circular and penetrating teat wound with a teat cannula inserted; (b) closure completed by a simple interrupted suture of the muscle and of the skin (the underneath suture of the mucosa and submucosa is not shown); (c) outcome after 6 months with healed wound and complete resolution of the functions.

Figure 3.

Thelectomy in a lactating ewe: (a-b) identification and application of a forceps at the base of the desensitized supernumerary teat and its removal using an electrosurgical spatula; (c) closure of the muscle and skin by a simple interrupted suture (the underneath suture of the mucosa and submucosa is not shown); (d) good outcome on the 16th day of post-surgery.

Figure 3.

Thelectomy in a lactating ewe: (a-b) identification and application of a forceps at the base of the desensitized supernumerary teat and its removal using an electrosurgical spatula; (c) closure of the muscle and skin by a simple interrupted suture (the underneath suture of the mucosa and submucosa is not shown); (d) good outcome on the 16th day of post-surgery.

Figure 4.

Teat neoplasm removal in a lactating ewe: (a-c) steps of a multiple papilloma removal located alongside the teat using an electrosurgical spatula; (d) closure of the subcutis with a simple running suture; (e) closure of the skin using a simple interrupted suture; (f) good outcome after 3 months.

Figure 4.

Teat neoplasm removal in a lactating ewe: (a-c) steps of a multiple papilloma removal located alongside the teat using an electrosurgical spatula; (d) closure of the subcutis with a simple running suture; (e) closure of the skin using a simple interrupted suture; (f) good outcome after 3 months.

Figure 5.

Removal of a tumor located at the lateral surface of the udder in a dry ewe: (a) local anesthesia surrounding the lesion; (b) clamping using Kelly forceps, dissection and removal of the lesion including a sufficient surrounding tissue using a scalpel blade; (c) closure of the subcutis with a simple running suture; (d) closure of the skin with a simple interrupted suture.

Figure 5.

Removal of a tumor located at the lateral surface of the udder in a dry ewe: (a) local anesthesia surrounding the lesion; (b) clamping using Kelly forceps, dissection and removal of the lesion including a sufficient surrounding tissue using a scalpel blade; (c) closure of the subcutis with a simple running suture; (d) closure of the skin with a simple interrupted suture.

Figure 6.

Mastectomy in a doe: (a) dry pregnant Saanen doe with multifocal to coalescing severe squamous cell carcinoma at the udder that requested a total mastectomy; (b) the doe on the 38th day post-surgery.

Figure 6.

Mastectomy in a doe: (a) dry pregnant Saanen doe with multifocal to coalescing severe squamous cell carcinoma at the udder that requested a total mastectomy; (b) the doe on the 38th day post-surgery.

Figure 7.

Good healing course of a skin neoplasm removal from the udder in a lactating ewe: (a) skin tumor in an ewe (note the numerous small papillomas surrounding the larger mass); (b) closure of the skin using a simple interrupted suture, and good healing on the 5th day post-surgery - the closure of the subcutis is not shown; (c) outcome after 6 months that shows healing by primary intention (however, note the growth of the small multifocal papillomas).

Figure 7.

Good healing course of a skin neoplasm removal from the udder in a lactating ewe: (a) skin tumor in an ewe (note the numerous small papillomas surrounding the larger mass); (b) closure of the skin using a simple interrupted suture, and good healing on the 5th day post-surgery - the closure of the subcutis is not shown; (c) outcome after 6 months that shows healing by primary intention (however, note the growth of the small multifocal papillomas).

Figure 8.

Poor healing course of a skin neoplasm removal from the udder in a lactating ewe: (a) single skin tumor located at the cranial aspect of the udder; (b-c) outcome on the 2nd and on the 7th day, respectively, showing infection, poor healing and dehiscence of the continuous suture due to the incorrect post-operative care by the owner; (d) outcome after 6 months showing a healing by second intention and a large scar (the teat functionality was preserved).

Figure 8.

Poor healing course of a skin neoplasm removal from the udder in a lactating ewe: (a) single skin tumor located at the cranial aspect of the udder; (b-c) outcome on the 2nd and on the 7th day, respectively, showing infection, poor healing and dehiscence of the continuous suture due to the incorrect post-operative care by the owner; (d) outcome after 6 months showing a healing by second intention and a large scar (the teat functionality was preserved).

Table 1.

Surgical treatment of 135 lesions of teat and udder in 129 small ruminants.

Table 1.

Surgical treatment of 135 lesions of teat and udder in 129 small ruminants.

| Surgical condition |

Ewes |

Does |

Animals |

Cases |

| Teat wound reparations |

17 |

2 |

19 |

19 |

| Teat fistula reparations |

2 |

- |

2 |

2 |

| Teat cistern curettage |

22 |

- |

22 |

26* |

| Thelectomies |

2 |

1 |

3 |

5** |

| Removals of teat skin neoplasms |

14 |

- |

14 |

14 |

| Removals of udder skin neoplasms |

67 |

- |

67 |

67 |

| Mastectomies |

- |

2 |

2 |

2 |

| Total |

124 |

5 |

129 |

135 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |