1. Introduction

High pathogenicity avian influenza (HPAI) continues to pose a global threat to the poultry industry, causing rapid mortality and substantial economic loss. According to the World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH), HPAI has led to the death of more than 663 million poultry worldwide from 2005 to 2024, including infected and exposed birds, with a peak of 146 million poultry in 2022 [

1]. Avian influenza viruses (AIVs) are classified into the following two pathotypes based on their pathogenicity in chickens: low and high pathogenicity AIV (HPAIV), which is the causal agent of HPAI [

2]. AIVs possess two surface glycoproteins: hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA), which are classified into 16 HA (H1–H16) and 9 NA (N1–N9) based on their reactivity to antiserum [

2]. HPAIVs are limited to the H5 or H7 subtype [

2]. Since the 2000s, H5 HPAIVs, especially those derived from A/goose/Guangdong/1/1996 (H5N1) lineage, have been prevalent for more than 20 years with genetic diversity. Notably, H5 HPAIVs in clade 2.3.4.4b have been mainly circulating in Europe and Asia since 2016 [

3] and have recently become a global concern [

4].

Although strict biosecurity and stamping out are primary HPAI control measures, vaccination in poultry is a useful optional measure for reducing mortality, virus shedding, and virus spreading [

5]. In addition, WOAH limits the use of vaccination under the implementation of appropriate surveillance [

2]. Given that HPAI control strategies vary widely across countries, including nonendemic and endemic countries, an ideal vaccine must demonstrate effectiveness for both emergency deployment and routine protection. To support regional control efforts against influenza outbreaks in animal health, the establishment of an influenza virus library under continuous surveillance should be an ideal preparedness to forestall control measures [

6]. One of the practical uses of this library is to provide viruses as a source for biologics. A Japanese stockpiled vaccine against H5 HPAIV for emergency use was prepared using this library. The vaccine comprised a nonpathogenic AIV, A/duck/Hokkaido/Vac-1/2004 (H5N1; Dk/Hok/Vac-1/04), inducing sufficient immunity in chickens, preventing mortality and clinical signs, although shedding of the challenge virus could not be completely prevented [

7,

8]. However, the antigenic drift in recently circulating H5 HPAIVs poses a significant risk of reducing the protective efficacy of this traditional vaccine. Since 2020, clade 2.3.4.4b of H5 HPAIVs has caused outbreaks across Europe and Asia [

9,

10,

11]. Clade 2.3.4.4b of H5N1 HPAIVs, isolated in Japan and Republic of Korea in winter 2022–2023, was classified as subgroups of G2b, G2c, and G2d in genotype group 2 [

12]. Although the antigenic characteristics of these subgroups were similar to each other and to previous clade 2.3.4.4b viruses, they were antigenically distinct from the stockpiled vaccine strain Dk/Hok/Vac-1/04 (H5N1) [

13]. A vaccine developed from a circulating field strain should provide high protective efficacy against the latest field strains.

Therefore, updating a vaccine strain that is antigenically matched to circulating strains is essential for preparedness against HPAI outbreaks in Asia. The primary goal of this study was to establish a candidate vaccine strain using a series of research steps, including enrichment of the AIV library by surveillance in the field, analysis of the genetic and antigenic properties of HPAIVs, and evaluation of the protective efficacy of vaccine. Protective efficacy was assessed through a challenge study using an HPAIV from clade 2.3.4.4b, A/Ezo red fox/Hokkaido/1/2022 (H5N1; Fox/Hok/1/22) [

14]. In addition, an inactivated vaccine made of a recombinant strain carrying HA and NA genes of Fox/Hok/1/22 with a modified HA cleavage site, designated NIID-002 (A/Ezo red fox/Hokkaido/1/2022) (H5N1; NIID-002) [

15], and an inactivated vaccine made of Dk/Hok/Vac-1/04 (H5N1) [

7] were included for comparing protective efficacy. Given the need to assess the efficacy of the candidate vaccine for both routine prophylactic use and emergency deployment scenarios, three independent animal experiments were conducted. First, to simulate routine vaccination program in HPAI endemic countries, protective efficacy was confirmed in juvenile chickens, which are the primary target population for mass vaccination. Second, to evaluate the suitability of the vaccine for emergency deployment, particularly for rapid containment during widespread outbreaks, the earliest onset of protective immunity was determined in juvenile chickens. Third, given that all the poultry, including juvenile and adult birds, must be targets of emergency vaccines, the study was extended to evaluate the protective efficacy of vaccine in around 40-week-old laying hens, with initial single-dose testing and optimization using a double-dose simultaneous regimen. Overall, these findings contribute to deepening the efficacy and limitations of the oil-adjuvanted vaccine in juvenile and adult birds as well as improving HPAI control efforts using inactivated vaccines.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection, Virus Isolation and Sequencing

To collect HPAIVs circulating in the field, AIV surveillance was conducted in northern Vietnam in 2019, 2021, 2023, and 2024 and southern Vietnam in 2019 and 2021. Oropharyngeal and cloacal swabs from live poultry, including chickens, ducks, and Muscovy ducks, and environmental swabs from floor or water containers were collected at live bird markets, farms, and poultry transport stations. The samples were preserved in viral transport medium, prepared in-house at The National Centre of Veterinary Diagnostics, Hanoi, Vietnam, using minimum essential medium (MEM; Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), penicillin–streptomycin (10,000 IU/mL; Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), HEPES buffer (Sartorius, Göttingen, Germany), and 35% bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA).

To detect AIV genes, 10 individual swab samples were pooled and screened by reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) targeting the M gene, following WOAH guidelines [

2], at The National Centre of Veterinary Diagnostics, Hanoi, Vietnam. Viruses were isolated from RT-qPCR-positive samples by inoculation into 10-day-old embryonated chicken eggs under Biosafety Level 3 (BSL-3) conditions at the Laboratory of Microbiology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Hokkaido University, Hokkaido, Japan.

From the H5 HPAIVs isolated, representative H5 HPAIVs were selected for whole-genome sequencing using next-generation sequencing, based on geographic region and isolation year. Oxford Nanopore libraries were prepared using NEB Ultra II End Repair/dA-Tailing Module (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) and sequenced on Flongle using the Nanopore Direct cDNA sequencing kit or Ligation Sequencing kit V14 (Oxford Nanopore Technologies, Oxford, England). Reads were mapped and assembled using FluGAS version 2 (World Fusion, Tokyo, Japan). H5 HPAIV sequence profiles were registered at the Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data (GISAID).

2.2. Phylogenetic Analysis

The nucleotide sequences of the representative isolates and other H5 HPAIVs obtained from GISAID were phylogenetically analyzed using MEGA 7 with the maximum likelihood method, including bootstrap analysis involving 1,000 replications and the best fit general time-reversible model of nucleotide substitution with gamma-distribution rate variation among sites (with 4 rate categories, Γ) according to the Tamura-Nei model [

16].

2.3. Hemagglutination Inhibition (HI) Test

Serum samples were inactivated at 56 °C for 30 min and adsorbed with chicken red blood cells (cRBCs) following the Japanese standards for veterinary biological products. Serum was mixed with 10% cRBCs at 1:3 ratio (1 volume of serum and 3 volumes of 10% cRBCs), incubated at 4 °C overnight, and centrifuged (1,000 × g, 5 min). The supernatant was collected as 4-fold diluted sera. The HI test was performed according to WOAH guidelines, and HI titers were defined as the highest serum dilution completely inhibiting 4 hemagglutination (HA) units of antigen [

2].

2.4. Antigenic Analysis

The antigenic characteristics of the representative viruses were evaluated through a cross-HI test using chicken hyperimmune antisera, as described [

17]. An antigen panel was set up with the following antigens: A/duck/Vietnam/HU16-DD3/2023 (H5N1; Dk/VN/DD3/23), A/duck/Vietnam/HU16-NS82/2023 (H5N1; Dk/VN/NS82/23), A/Muscovy duck/Vietnam/HU14-GV50/2021 (H5N8; Mdk/VN/GV50/21), A/chicken/Vietnam/HU11-903/2019 (H5N6; Ck/VN/903/19), A/duck/Vietnam/HU12-971/2019 (H5N6; Dk/VN/971/19), and A/chicken/Vietnam/HU12-657/2019 (H5N1; Ck/VN/657/19), which was isolated in this study. Reference antigens from other H5 clades were also analyzed. Viruses from clade 2.3.4.4b included A/Eurasian wigeon/Hokkaido/Q71/2022 (H5N1; EW/Hok/Q71/22) [

13], A/white-tailed eagle/Hokkaido/22-RU-WTE-2/2022 (H5N1; WTE/Hok/R22/22) [

18], Fox/Hok/1/22 (H5N1) [

14], and A/northern pintail/Hokkaido/M13/2020 (H5N1; Np/Hok/M13/20) [

19]. Clade 2.3.4.4c was represented by A/chicken/Kumamoto/1-7/2014 (H5N8; Ck/Kum/1-7/14) [

20]. Clade 2.3.4.4e was represented by A/black swan/Akita/1/2016 (H5N6; Bs/Aki/1/16) [

21]. Clade 2.3.4.4 was represented by A/chicken/Vietnam/HU4-42/2015 (H5N6; Ck/VN/42/15) [

22]. Clade 2.3.4.4g was represented by A/Muscovy duck/Vietnam/HU7-20/2017 (H5N6; Mdk/VN/20/17) [

22]. Clade 2.3.4 was represented by A/peregrine falcon/Hong Kong/810/2009 (H5N1; Pfal/HK/810/09) [

23]. Clade 2.3.2.1e, formerly 2.3.2.1c [

24], was represented by A/duck/Vietnam/HU3-836/2015 (H5N1; Dk/VN/386/15) [

22]. Clade 1.1 was represented by A/Muscovy duck/Vietnam/OIE-559/2011 (H5N1; Mdk/VN/559/11) [

23]. The stockpiled vaccine strain Dk/Hok/Vac-1/04 (H5N1) was included as a reference. An antisera panel including EW/Hok/Q71/22, WTE/Hok/R22/22, Bs/Akita/1/16, Ck/Kum/1-7/14, Dk/VN/20/17, Dk/VN/386/15, and Pfal/HK/810/09 was used. Hyperimmune serum against Dk/VN/DD3/23 strains was prepared, according to Kida and Yanagawa [

17]. Antigenic cartography was generated based on the cross-HI test using Racmac software [

25]. HI titers were converted into antigenic distances by log

2 transformation, where a 2-fold difference in titers corresponds to one unit of distance. The x–y coordinates of antigens and antisera were obtained through multidimensional scaling to best represent the antigenic relationships, minimizing the discrepancy between observed and map distances.

2.5. Animals, Cells and Viruses

White Leghorn chickens were hatched from embryonated chicken eggs and raised at the Experimental Animal Facility, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Hokkaido University, until 7 weeks of age. Chickens were transferred to a self-contained isolator unit (Tokiwa Kagaku Kikai) at the BSL-3 facility, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Hokkaido University. In addition, 40-week-old White Leghorn laying hens were kindly provided by Hokuryo Co., Ltd. (Hokkaido, Japan). The hens were individually housed in the same type of self-contained isolator units within the BSL-3 facility. All chickens used in this study had no prior vaccination history and were free of maternally derived antibodies, because vaccination against AIVs is not implemented in Japan.

Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells were cultured at 37 °C in MEM (Shimadzu Diagnostics Corporation, Tokyo, Japan), supplemented with 0.3 mg/mL L-glutamine (Nacalai Tesque Inc., Kyoto, Japan), 100 U/mL penicillin G, 0.1 mg/mL streptomycin (both from Meiji Seika Pharma Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), 8 µg/mL gentamicin (Takata Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Saitama, Japan), and 10% fetal bovine serum (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany). Human embryonic kidney 293T (HEK293T) cells were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 in pyruvate-free Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA), supplemented with the same antibiotics and 10% fetal bovine serum (Nichirei Biosciences Inc., Tokyo, Japan).

Fox/Hok/1/22 (H5N1), previously isolated from a deceased Ezo red fox (

Vulpes vulpes schrencki) [

14], was used as a challenge strain. For comparison, NIID-002 (H5N1) virus [

15], provided by the National Institute of Infectious Diseases, Japan, was used as the vaccine strain. Dk/VN/DD3/23 (H5N1) isolated from an apparently healthy duck at a live bird market in northern Vietnam was used as the parental strain for establishing the vaccine strain. All three viruses were propagated in 10-day-old embryonated chicken eggs. The presence of viruses in allantoic fluid was confirmed using the HA test; 50% egg infectious dose (EID

50) was determined for each strain. In addition, 50% chicken lethal dose (CLD

50) was determined for the challenge strain Fox/Hok/1/22 (H5N1).

2.6. Generation and Evaluation of Vaccine Strain

Reverse genetics was used to generate a recombinant virus by incorporating H5 HA and N1 NA from the representative field strain with the internal genes derived from A/Puerto Rico/8/1934 (H1N1; PR8). To reduce virulence, HA gene was cloned into the pGEM-T easy vector (Promega, US) and mutated at the HA cleavage site. Polybasic amino acids (EKRRKR|GLF) were mutated to the monobasic amino acid threonine (ETR|GLF) using KOD-Plus Mutagenesis Kit (TOYOBO, Japan). The modified HA gene was subcloned, and NA gene was directly cloned into the pHW2000 vector [

26]. Plasmids containing the PR8-derived internal genes were utilized. The eight pHW2000 plasmids were used to transfect co-cultured MDCK and HEK293T cells. At 72 hours post-transfection, the supernatant was collected and inoculated into 10-day-old embryonated chicken eggs for virus propagation.

To assess growth kinetics, the vaccine strains were inoculated into 10-day-old embryonated chicken eggs at doses of 2.0 and 4.0 log10 EID50/0.1 mL per egg. All eggs were collected at 12-, 24-, 36-, 48-, 60-, and 72-h post-inoculation to measure virus titers (expressed as EID50).

To confirm the low pathogenicity of the vaccine strains, intravenous pathogenicity index (IVPI) was determined following the WOAH guidelines [

2]. Briefly, 6-week-old chickens (n = 8 per vaccine strain) were intravenously inoculated into the wing vein with 0.1 mL of 1:10 dilution of infective allantoic fluid. The chickens were observed daily for 10 days, and clinical signs were scored as follows: 0 (normal) for no sign; 1 (sick) for showing a single sign (respiratory symptom, depression, diarrhea, cyanosis, edema, or nervous symptom); 2 (seriously sick) for showing multiple signs; and 3 for death. The IVPI was calculated as the mean score per chicken, with an index score above 1.2 used as the definitive threshold for classifying viruses as HPAIV.

2.7. Vaccine Preparation

Whole harvested allantoic fluid containing each candidate vaccine strain was inactivated by incubation with formalin at a final concentration of 0.2% for 3 days at 4 °C. Inactivation was confirmed by three successive serial passages in 10-day-old embryonated chicken eggs. Trial vaccines were produced by mixing with an oil adjuvant, according to Sasaki et al. [

27]. Based on HA titers, the inactivated virus suspension was diluted with sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to a final concentration of 633.5 HA units/0.5 mL. The suspensions were mixed with oil adjuvant. The emulsion was homogenized using an ultra-homomixer (PRIMIX Co., Ltd.) to produce a water-in-oil vaccine.

2.8. Assessment of Vaccine Protective Capacity in Juvenile Chickens

Forty 4-week-old White Leghorn chickens were randomly divided into four groups of 10 chickens each, including three vaccinated groups and one unvaccinated group. Chickens were intramuscularly injected with the vaccine developed in this study, NIID-002 vaccine, and Dk/Hok/Vac-1/04 vaccine at a single dose of 633.5 HA units/0.5 mL. Blood was collected weekly to monitor the antibody response. At 21 days post-vaccination (dpv) (7-week-old), all chickens were intranasally challenged with 100 CLD50 of Fox/Hok/1/22 (H5N1), equivalent to 6.2 log10 EID50/0.1 mL. Clinical signs and mortality in chickens were monitored until 14 days post-challenge (dpc). Oropharyngeal and cloacal swab samples were collected at 2, 3, 5, and 7 dpc to assess viral shedding.

2.9. RT-qPCR

A subset of oropharyngeal and cloacal swab samples was used, which were obtained from chickens injected with the vaccine developed in this study, the Dk/Hok/Vac-1/04 vaccine as well as unvaccinated chickens (five chickens per group). Viral RNA was extracted using MagMAX-96 Total RNA Isolation Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RT-qPCR was performed with duplicate technical replicates per sample using Thunderbird Probe One-Step qRT-PCR Kit (TOYOBO, Japan), following the manufacturer’s instructions. The test targeted the M gene using primers and probe as listed in

Table S1.

2.10. Determination of the Earliest Onset of Protective Immunity in Juvenile Chickens

Twenty 35-day-old White Leghorn chickens were randomly divided into five groups of four chickens each. Four groups of chickens were intramuscularly injected with a single dose of the vaccine developed in this study at 35-, 39-, 41-, and 43-days old, corresponding to 14, 10, 8, and 6 days before the challenge. The remaining chickens were in the unvaccinated group. All chickens were bled at 49-day-old (7-week-old) to evaluate antibody responses immediately prior to the challenge and subsequently intranasally inoculated with 100 CLD50/0.1 mL of Fox/Hok/1/22 (H5N1). Clinical signs and mortality were monitored daily for 14 days. Oropharyngeal and cloacal swab samples were collected at 2, 3, 5, and 7 dpc to assess viral shedding.

2.11. Evaluation of Vaccine Efficacy in the Laying Hens

Two independent experimental rounds were conducted to evaluate vaccination regimens in 40-week-old White Leghorn hens. Both rounds included unvaccinated and vaccinated groups, with four hens per group. In round 1 (n = 8), the efficacy of a single vaccine dose (633.5 HA units/0.5 mL) was assessed. Simultaneous injections of a single- and double-dose (2 × 0.5 mL total) were compared in round 2 (n = 12). The hens were intramuscularly vaccinated, and their blood was collected weekly to monitor antibody responses. All hens were intranasal challenged with 100 CLD50/0.1 mL of Fox/Hok/1/22 (H5N1) at 21 dpv. Clinical signs and mortality were monitored daily. Oropharyngeal and cloacal swab samples were collected at 2, 3, 5, and 7 dpc in round 1, and at 2, 3, 4, 5, and 7 dpc in round 2. Additionally, eggs laid by hens were collected daily from 1 to 7 dpc to detect H5 HPAIV contamination. Eggshells were wiped with cotton swabs soaked in viral transport medium. Egg yolks and egg whites were collected separately.

2.12. Virus Titration

Oropharyngeal and cloacal swab samples were serially 10-fold diluted in MEM. Confluent MDCK cell monolayers were incubated with the diluted swab samples for 1 h at 35 °C. The inoculum was removed, cells were washed with sterile PBS, and cultured in serum-free MEM supplemented with 1.0 µg/mL acetylated trypsin (Merck) at 35 °C for 72 hours. Cytopathic effect was observed and recorded to calculate 50% tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50).

Eggshell swab and egg white samples were serially 10-fold diluted in sterile PBS. Egg yolk was prediluted 1:2 in sterile PBS before performing serial 10-fold dilutions, due to high viscosity. The diluted egg-derived samples were then inoculated into 10-day-old embryonated chicken eggs. After incubation at 35 °C for 48 hours. Allantoic fluid was harvested and HA test was performed to calculate EID

50 values. All virus titers were calculated using the method of Reed and Muench [

28].

2.13. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 10.1.2 (GraphPad Software

Inc.; San Diego, CA, USA). Antibody titers across groups were compared using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey’s honestly significant difference post-hoc test for pairwise comparisons. Data obtained from two groups were analyzed using Student’s t-test. The log-rank test was used for analyzing survival rates. A p-value of less than 0.05 (p < 0.05) was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. AIV Surveillance in Vietnam from 2019 to 2024

Surveillance in poultry was conducted in North and South Vietnam between 2019 and 2024, excluding 2020 and 2022. Seven hundred and forty-nine AIVs were isolated from 6,034 collected samples, of which 108 viruses were H5 HPAIVs, including 37 H5N6 viruses in 2019 and 2021; 21 H5N8 viruses in 2021; and 50 H5N1 viruses in 2019, 2023, and 2024. Other subtypes of virus isolates were H9N2, H6N6, H3N2, H3N8, H3N4, H6N2, H6N3, H6N4, H9N4, and H10N3 (

Table S2).

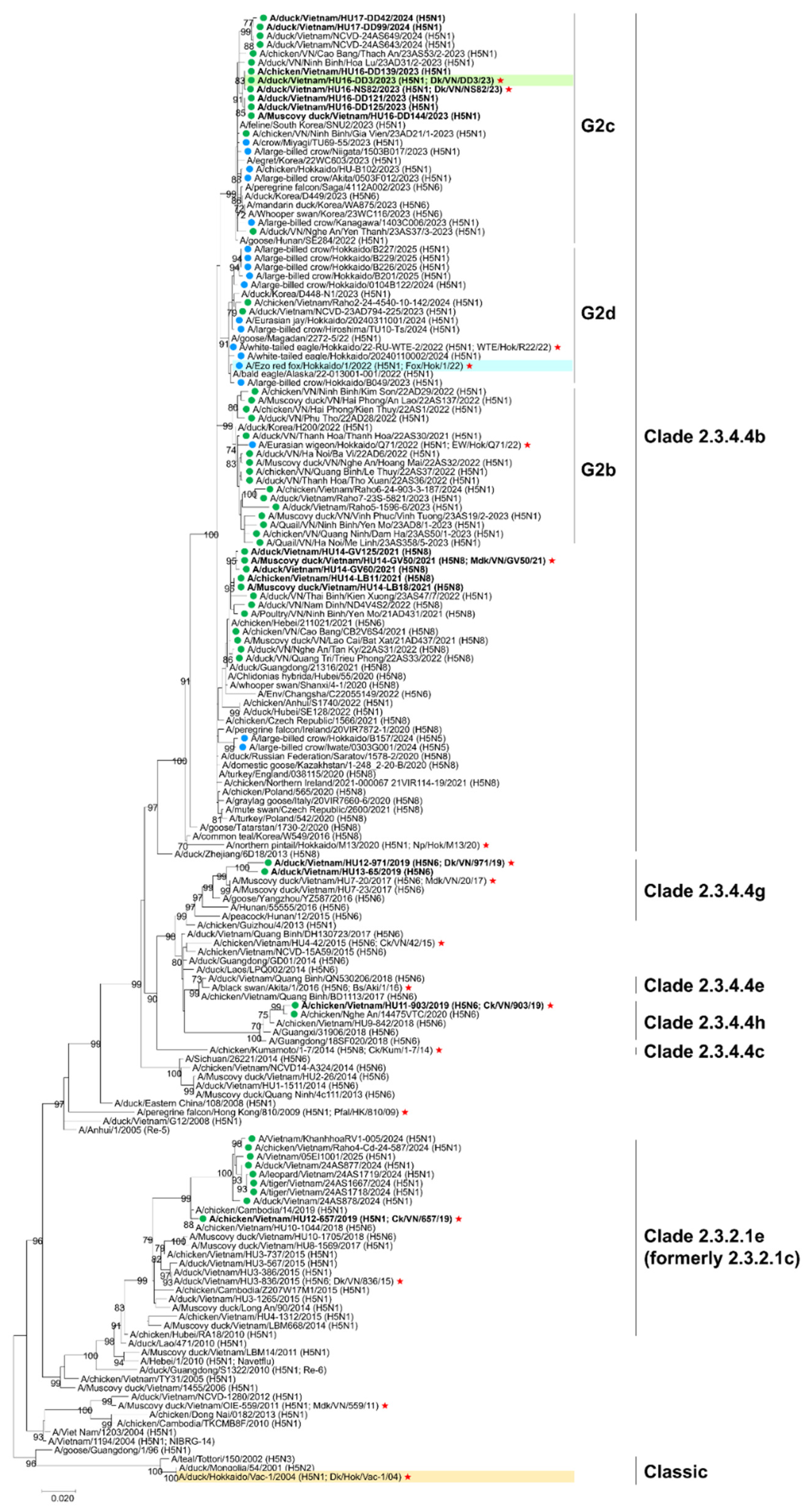

3.2. Genetic Analysis of H5 HA Genes of HPAIVs

HA genes from 17 H5 HPAIVs obtained through surveillance were sequenced to perform phylogenetic analysis (

Table S3). Phylogenetic analysis showed that isolates in 2019 belonged to clades 2.3.2.1e (formerly 2.3.2.1c), 2.3.4.4h, and 2.3.4.4g (

Figure 1). Clade 2.3.4.4h and 2.3.4.4g viruses were genetically related to strains previously isolated in Vietnam and China but have not been detected after 2021. Clade 2.3.2.1e viruses, which are genetically close to strains previously isolated in Vietnam and Cambodia, were circulating with slight genetic variability. Vietnamese isolates in 2023–2024 belonged to clade 2.3.4.4b and subgroups G2c, which were genetically similar to those from Japan and the Republic of Korea. Collectively, these results highlight the significant genetic diversity of H5 HPAIVs in the field. Furthermore, all analyzed H5 HPAIVs were genetically distinct from classic H5 strains, including the Japanese stockpiled vaccine strain.

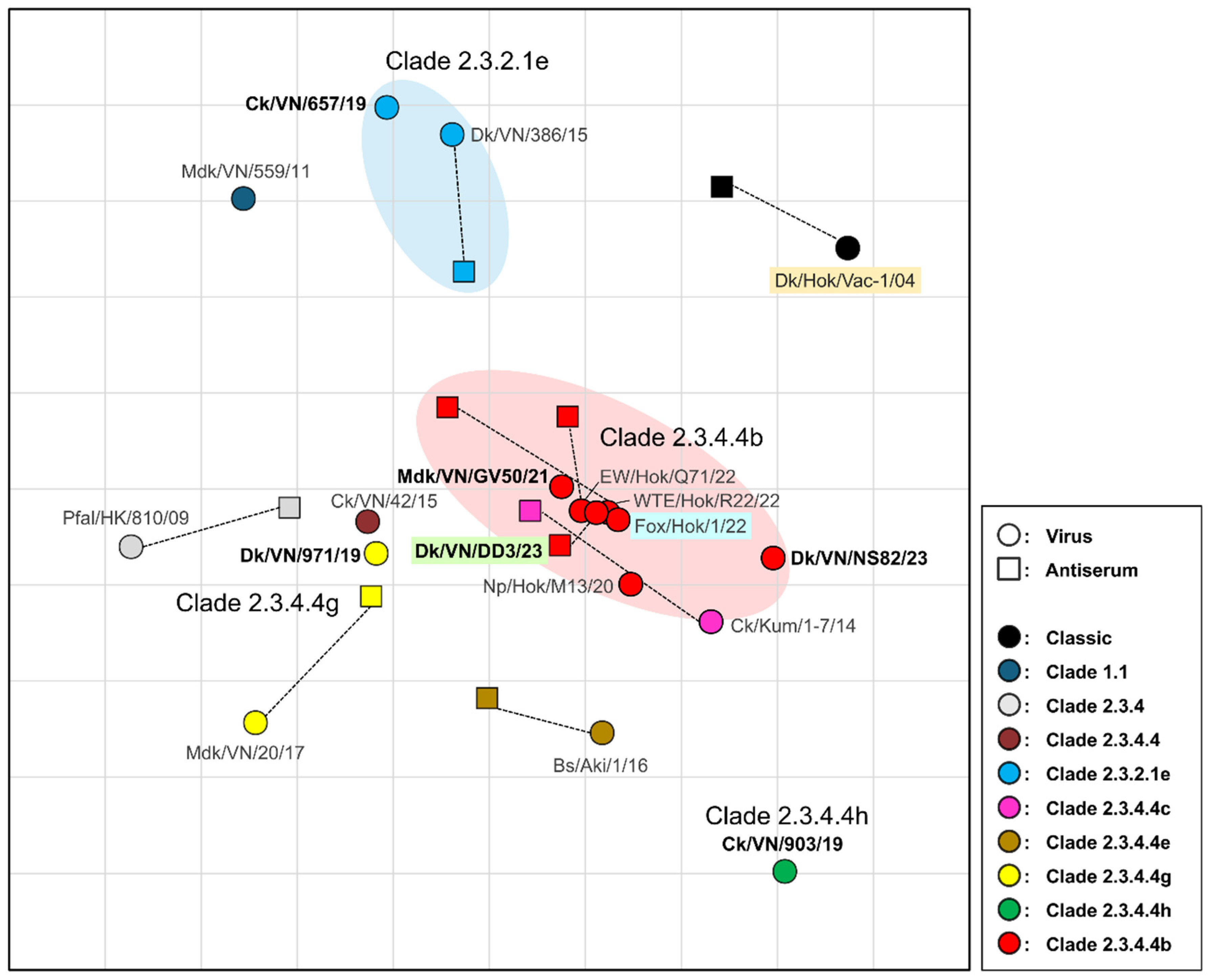

3.3. Antigenic Analysis of the H5 HPAIVs

Antigenicity of H5 HPAIVs isolated from 2019 to 2024 was analyzed and visualized through antigenic cartography (

Figure 2 and

Table S4). On the cartograph, clade 2.3.4.4b viruses displayed antigenic similarity, with distances within 1 antigenic unit. Clade 2.3.4.4b viruses showed antigenic proximity with strains belonging to clade 2.3.4.4c (Ck/Kum/1-7/14) and precursor clade 2.3.4.4 (Ck/VN/42/15). Dk/VN/971/19 strain, belonging to clade 2.3.4.4g, exhibited antigenic closeness with viruses of clades 2.3.4.4b and 2.3.4.4, despite having a more than 4-fold difference in HI titer compared with the Mdk/VN/20/17 isolate of clade 2.3.4.4g. Clade 2.3.2.1e viruses formed an antigenically distinct cluster that was different from clade 2.3.4.4b viruses, as shown on the antigenic map. Similarly, clade 2.3.4.4h virus (Ck/VN/903/19) was antigenically distinct from the other analyzed isolates. Notably, all analyzed isolates were antigenically divergent from Dk/Hok/Vac-1/04. Together, these findings highlight the antigenic distinctions of the circulating H5 HPAIVs in the field.

3.4. Generation and Characterization of Vaccine Strain

Dk/VN/DD3/23 (H5N1) was selected for vaccine development based on genetic and antigenic analysis. A recombinant strain, rgPR8/VN23HA∆KRRK-NA (H5N1; rgPR8/VN23), was successfully rescued using reverse genetics. The virus does not possess the polybasic HA cleavage site and unexpected mutations, carrying the HA and NA genes derived from Dk/VN/DD3/23 (H5N1) and the six internal genes of the PR8 (H1N1) backbone. Both cross-HI titers of rgPR8/VN23 and Dk/VN/DD3/23 against antisera of Dk/VN/DD3/23 were 640 HI, suggesting that rgPR8/VN23 was not antigenically different from Dk/VN/DD3/23, thus confirming antigenic integrity.

Chickens intravenously inoculated with rgPR8/VN23 or NIID-002 were clinically normal for the 10 days of observation. Both vaccine strains scored an IVPI of 0.0 (

Table S5). These results confirm the successful attenuation and safety of both rgPR8/VN23 and NIID-002.

rgPR8/VN23 exhibited high growth properties in embryonated chicken eggs at inoculation doses of both 2.0 and 4.0 log

10 EID

50/0.1 mL. Virus titers increased rapidly within the first 24 hours of inoculation; the highest titers were achieved and maintained in the range of 9.3–10.3 log

10 EID

50/mL (

Figure S1). Although NIID-002 (H5N1), which carries the HA and NA genes of Fox/Hox/22 (H5N1) and six internal genes of PR8 (H1N1), showed a lower growth ability in the early stages of infection, its growth kinetics were comparable to those of rgPR8/VN23 after 48 hours. These data indicated that both rgPR8/VN23 and NIID-002 have high growth potential in eggs and satisfy the requirements of a vaccine strain: low pathogenicity in chickens and high growth potential in embryonated chicken eggs.

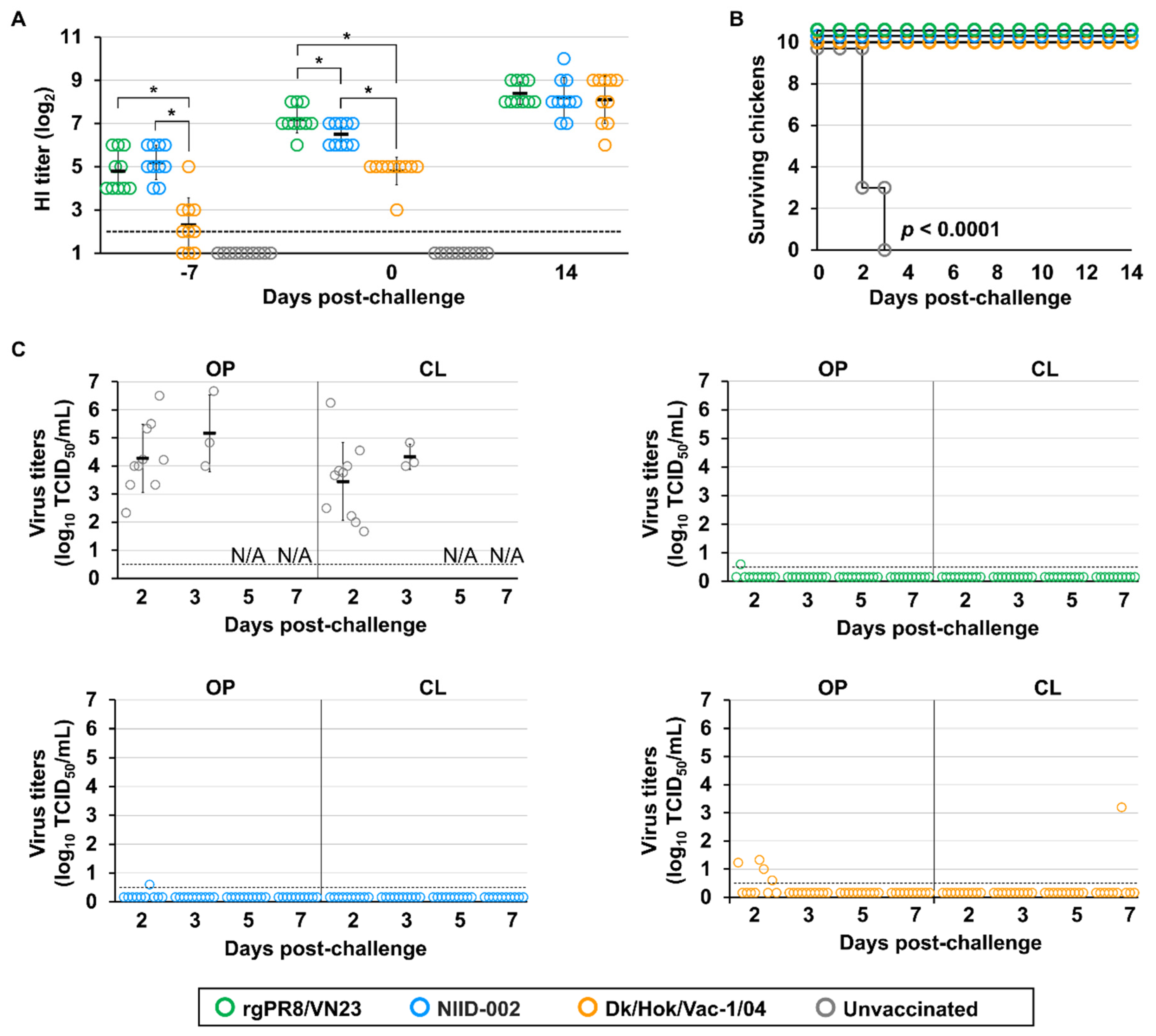

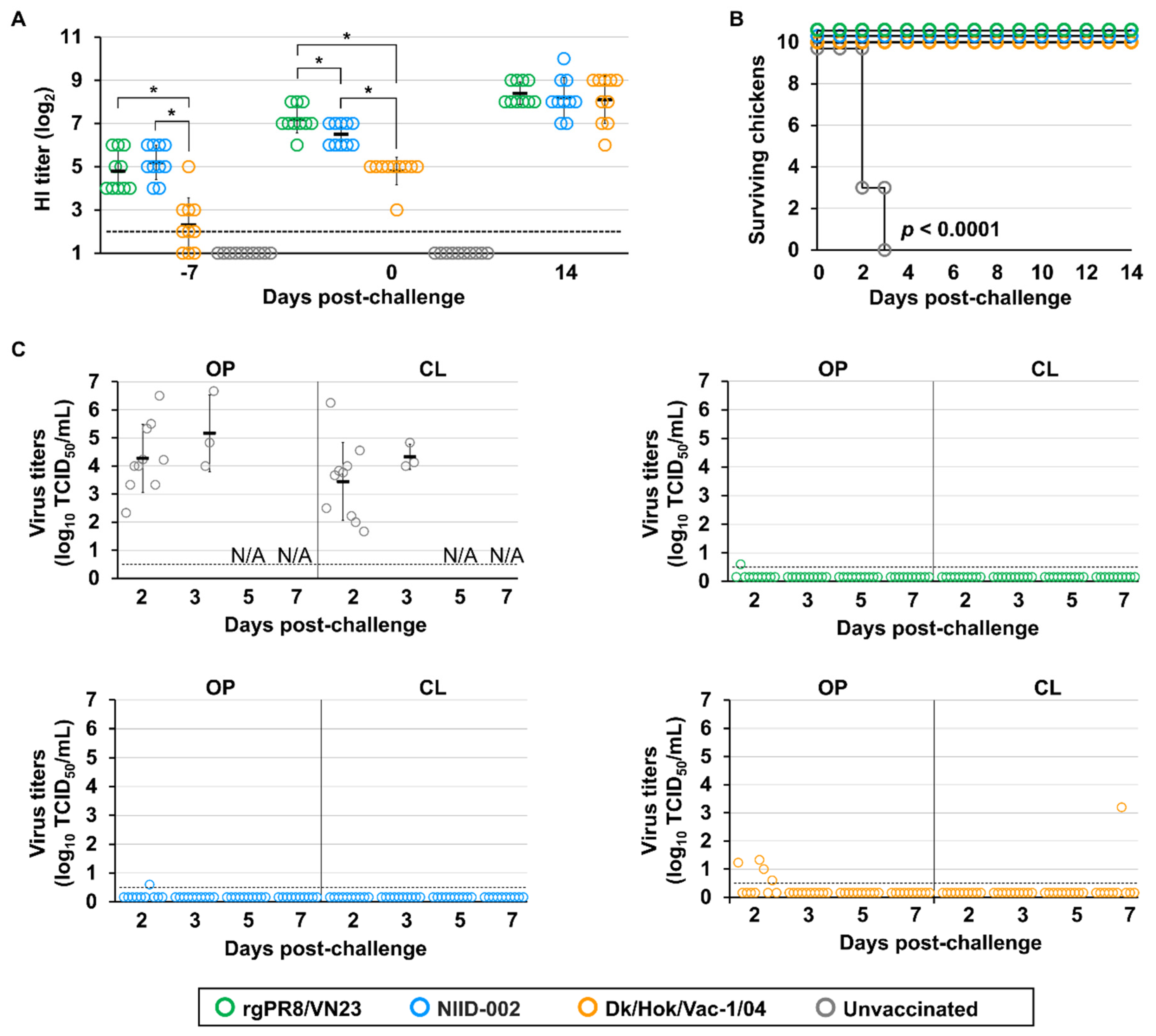

3.5. Vaccine Protective Capacity in Juvenile Chickens

After the preparation of inactivated oil-adjuvanted vaccines, the immunogenicity of the vaccines was assessed by monitoring antibody titers. The three vaccines derived from rgPR8/VN23 (H5N1), NIID-002 (H5N1), and Dk/Vac-1/04 (H5N1) successfully elicited an immune response against their homologous and challenge strains (

Figure 3A and

Figure S2). Antibodies were detectable at 14 dpv; antibody titers before vaccination and at 7 dpv were below 2 log

2 HI. The antibody levels of chickens vaccinated with the rgPR8/VN23 or NIID-002 vaccine against the challenge strain were similar, with geometric mean titers (GMTs) of 4.8 ± 0.92 log

2 and 5.2 ± 0.79 log

2, respectively (

Table S6A). Antibody titers of chickens vaccinated with Dk/Hok/Vac-1/04 against the challenge strain were significantly lower (

p < 0.05) than those vaccinated with others. Only one reached 5 log

2, and others ≤3 log

2, including undetectable titer. At 21 dpv, the antibody levels of chickens in all the three vaccinated groups against the challenge strain continued to increase. The GMT of the rgPR8/VN23 vaccine reached 7.2 ± 0.63 log

2 and was higher than that of the NIID-002 vaccine (6.5 ± 0.53 log

2,

p < 0.05). The titers of chickens vaccinated with Dk/Hok/Vac-1/04 were significantly lower than those of others, with a GMT of 4.8 ± 0.63 log

2. At 14 dpc, differences in HI titers were non-significant across the three vaccinated chicken groups (

p > 0.05). In each vaccine group, differences in HI titers were non-significant between challenge and vaccine strains. Together, these data demonstrate that the HI titers of vaccinated chickens increased within 14 days of vaccination, although the antibody levels against the challenge strain in the Dk/Hok/Vac-1/04 group was lower due to different antigenicity between the clade 2.3.4.4b virus and classic virus.

Vaccine efficacy was evaluated based on mortality following challenge with Fox/Hok/1/22 (H5N1). All chickens in the unvaccinated group died within 3 days, whereas all vaccinated chickens survived for 14 dpc (

Figure 3B), demonstrating that all three vaccines conferred strong preventive immunity against clinical symptoms after HPAIV infection.

Virus shedding from both oropharyngeal and cloacal swabs was observed in all chickens in the unvaccinated group at 2 dpc (n = 10) and 3 dpc (n = 3). The viral load exhibited individual variations, with titers of 2.3–6.7 and 1.7–6.3 log

10 TCID

50/mL in oropharyngeal and cloacal samples, respectively (

Figure 3C). By contrast, detectable viruses (>0.5 log

10 TCID

50/mL were not confirmed from most chickens vaccinated with rgPR8/VN23 (9/10) and NIID-002 (9/10) in both the oropharynx and cloaca during sampling. The transient virus shed was confirmed from oropharyngeal samples of only one chicken in each vaccinated group, with very low virus titer (0.6 log

10 TCID

50/mL) at 2 dpc. Infectious viruses were not detected in cloacal swabs. In the Dk/Hok/Vac-1/04 group, infectious viruses were recovered from four out of ten chickens from oropharyngeal swabs at 2 dpc, with titers of 0.6–1.3 log

10 TCID

50/mL. Of these four chickens, three ceased viral shedding thereafter, and one chicken exhibited a recurrence of virus shedding in the cloacal swab at 7 dpc, with a titer of 3.2 log

10 TCID

50/mL. Overall, all three vaccines reduced the titers of viruses recovered from swab samples compared with the unvaccinated group. The rgPR8/VN23 and NIID-002 vaccines demonstrated superior efficacy by markedly reducing virus titer recovered, resulting in near-sterile protection, whereas the Dk/Hok/Vac-1/04 vaccine provided only partial reduction.

To investigate the persistence of viral genes, the M gene was detected using RT-qPCR on a subset of swab samples. The rgPR8/VN23 and Dk/Hok/Vac-1/04 vaccine groups were assessed, because similar protection was observed in rgPR8/VN23 and NIID-002 vaccines. Swab samples before challenge, which served as negative controls for the M gene detection by RT-qPCR, exhibited

Ct values of ≥37 (data not shown). Samples from the unvaccinated group (positive controls) showed strong signals with

Ct values of <35, consistent with titers of infectious virus (

Figure S3). In samples obtained from the rgPR8/VN23 group, despite the absence of infectious virus, M gene was detected with

Ct values of 35–37. A similar finding of low-level RNA persistence was observed in the Dk/Hok/Vac-1/04 vaccine group, in addition to the strong signals (

Ct < 35) found in samples positive for infectious virus.

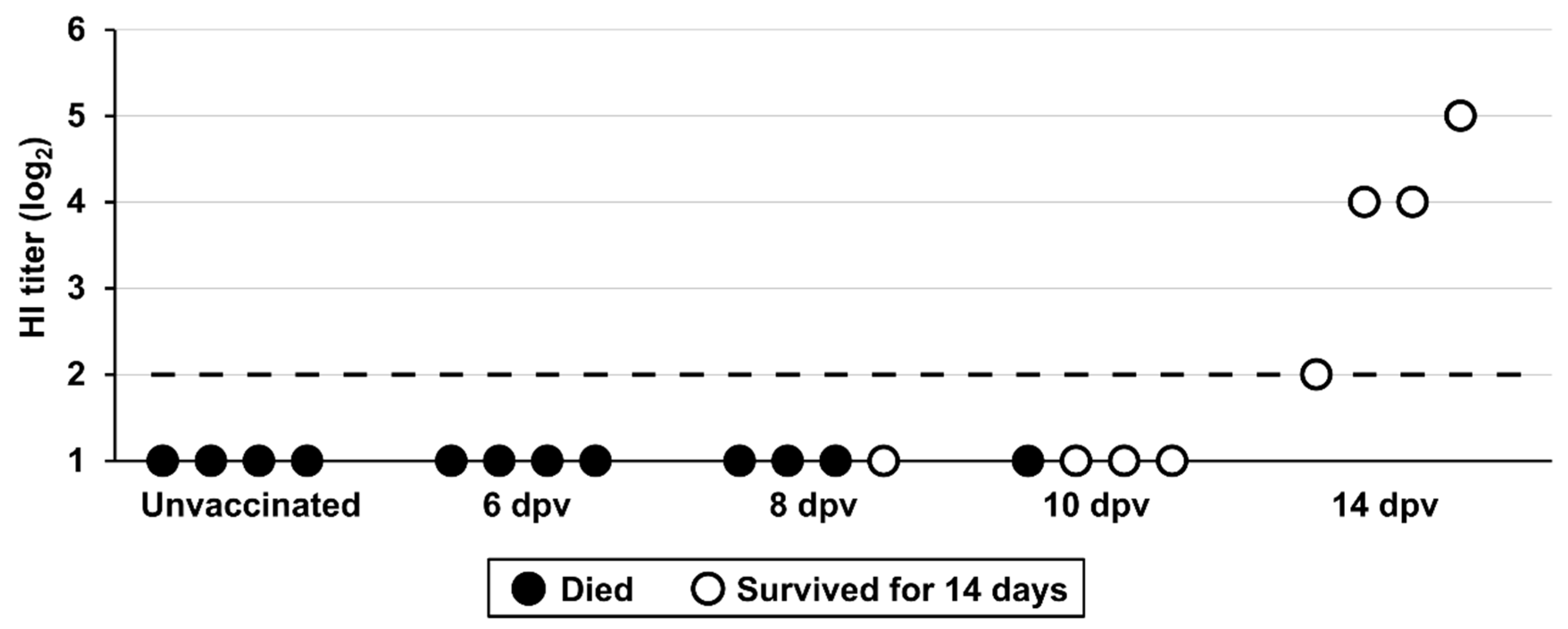

3.6. Vaccine Protection Onset in Juvenile Chickens

The acquisition of vaccine protection was determined at the earliest time after vaccination when the chickens were protected against mortality following the H5 HPAIV challenge. All vaccinated chickens challenged at 6 dpv died within 3 days, similar to the unvaccinated group (

Figure 4 and

Figure S4). When challenged at 8 dpv, one of four chickens survived, indicating partial immunity at 8 dpv. Protection rates substantially increased in the group challenged at 10 dpv, with three of four chickens surviving. Optimal protection was achieved at 14 dpv, where all chickens survived. HI titers were below the limit of detection (2 log

2) for serum samples collected at 6, 8, and 10 dpv, whereas antibodies were detectable in serum samples collected at 14 dpv, ranging from 2 to 5 log

2. Infectious viruses were not detected in the 14 dpv group, contrasting with virus recovery in chickens challenged at 6, 8, and 10 dpv.

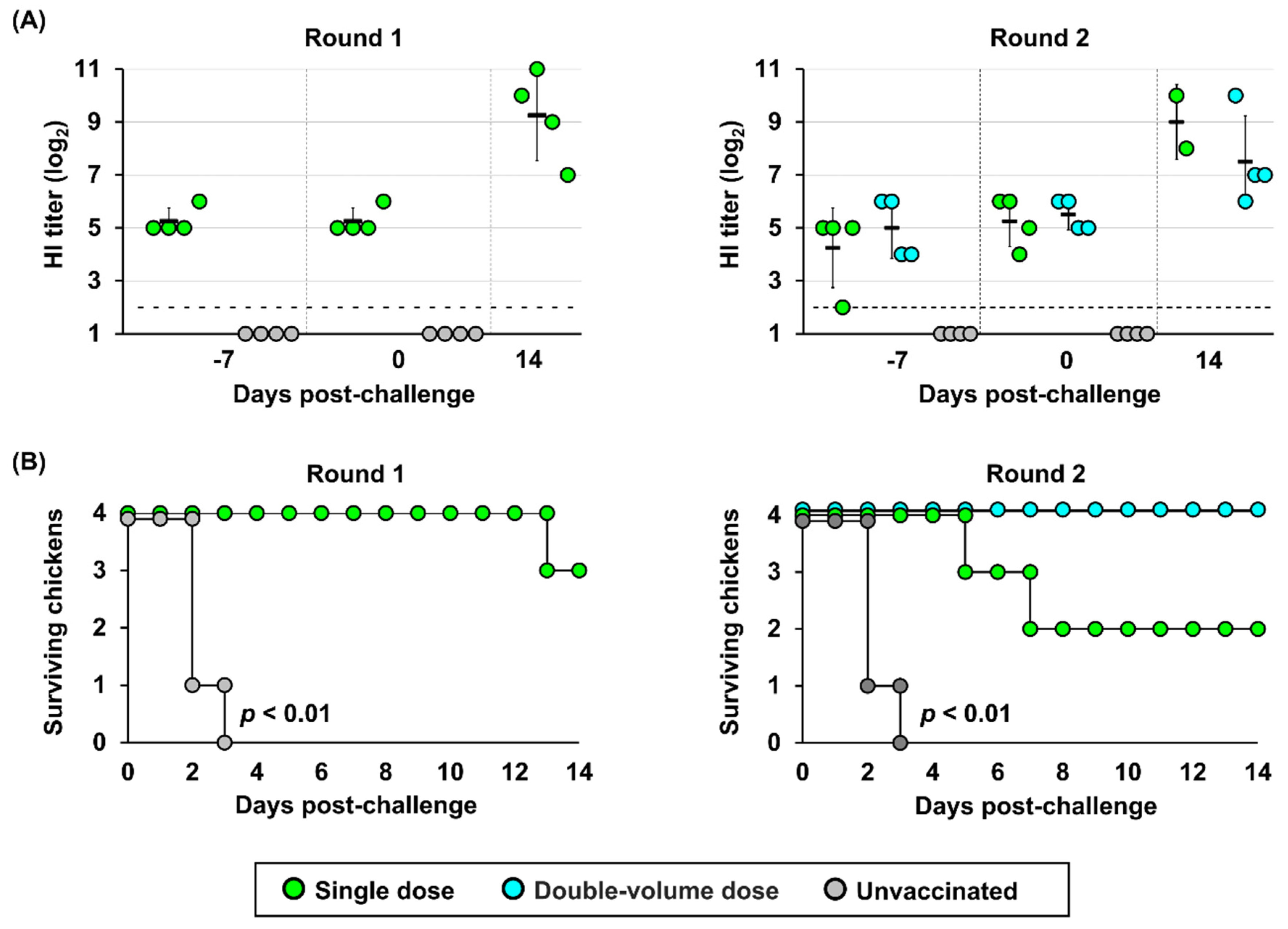

3.7. Vaccine Efficacy in Laying Hens

Given the application of vaccines in emergency use, all poultry, including juvenile and adult chickens, were targets of vaccine administration, and protective immunity can be conferred only by single-shot injection. Two independent experimental rounds were conducted in hens to evaluate the efficacy of a single dose, and a double-volume dose, assuming that a single dose of vaccine should not be enough to induce protective immunity in hens of bigger body sizes than juvenile chickens through a single-shot injection. Antibodies were successfully elicited in all vaccinated hen groups, with no-significant differences observed in the antibody titers at 14 and 21 dpv (

Figure 5A and

Table S6B). Although the HI titer at 21 dpv was similar, the protective efficacy of double-volume vaccines was higher than that of a single dose vaccine (

Figure 5B). At 14 dpc, a strong second response was observed in all surviving hens, in which GMTs were significantly higher than before challenge. In the double-volume dose group, only one hen displayed mild clinical signs, including depression, ruffled feathers, loss of appetite, and cessation of egg production, from 5 dpc. By contrast, in both rounds, the single dose provided partial protection and consistent clinical signs. In round 1, three of four vaccinated hens displayed clinical signs since 4 dpc, beginning with transient prominent periorbital and facial swelling, and progressing to severe neurological signs, such as torticollis or coma. One of these hens was euthanized due to reaching the humane endpoint at 13 dpc. The limited efficacy of a single-dose vaccine in hens was observed in round 2; two out of four hens died at 5 and 7 dpc, with symptoms of fatigue and progressive lethargy. These hens produced eggs before becoming lethargic, but eggshells were thin and fragile on their last day of production at 3 and 5 dpc. Of the other two surviving individuals, one was asymptomatic, but the other showed neurological signs with mild neck torticollis and ceased egg production starting at 7 dpc.

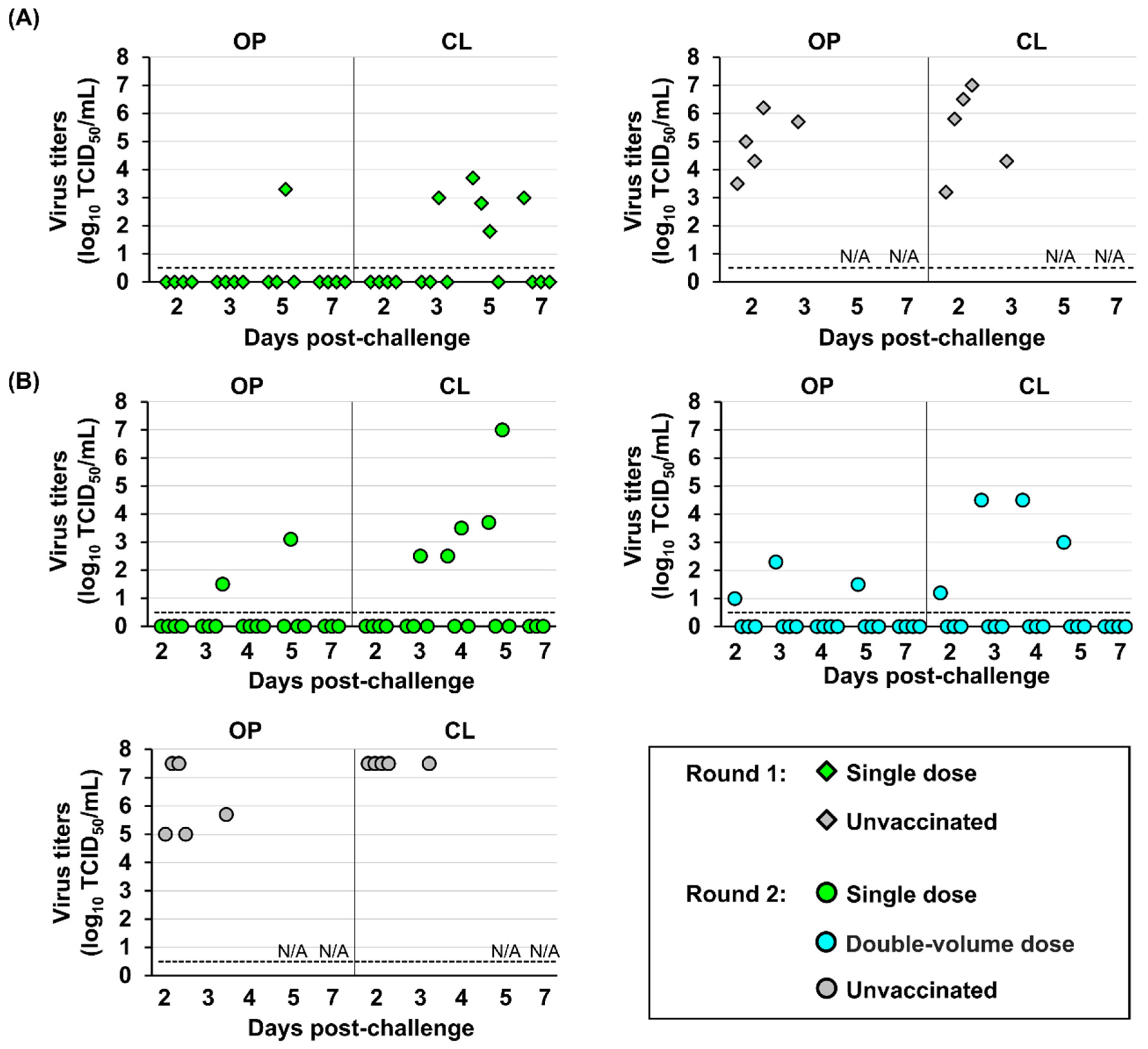

Viruses with high titers were detected from both oropharyngeal and cloacal swabs of all unvaccinated hens at 2 and 3 dpc (

Figure 6). The single-dose regimen showed low efficacy in reducing viral shedding, with detectable viruses in three out of four vaccinated chickens in round 1 and in all four vaccinated chickens in round 2. A delay of viral recovery was observed in some individuals compared with the unvaccinated groups, peaking at 4–5 dpc and persisting up to 7 dpc. By contrast, in the double-volume dose group, virus recovery was limited in only one hen, which displayed mild clinical signs and virus recovery at 2, 3, 4, and 5 dpc. For this specific shedding hen, virus titer was higher in cloacal swabs, with the highest titers of 4.5 log

10 TCID

50 at 3 and 4 dpc and lowest titers of 1.2 log

10 TCID

50 at 2 dpc.

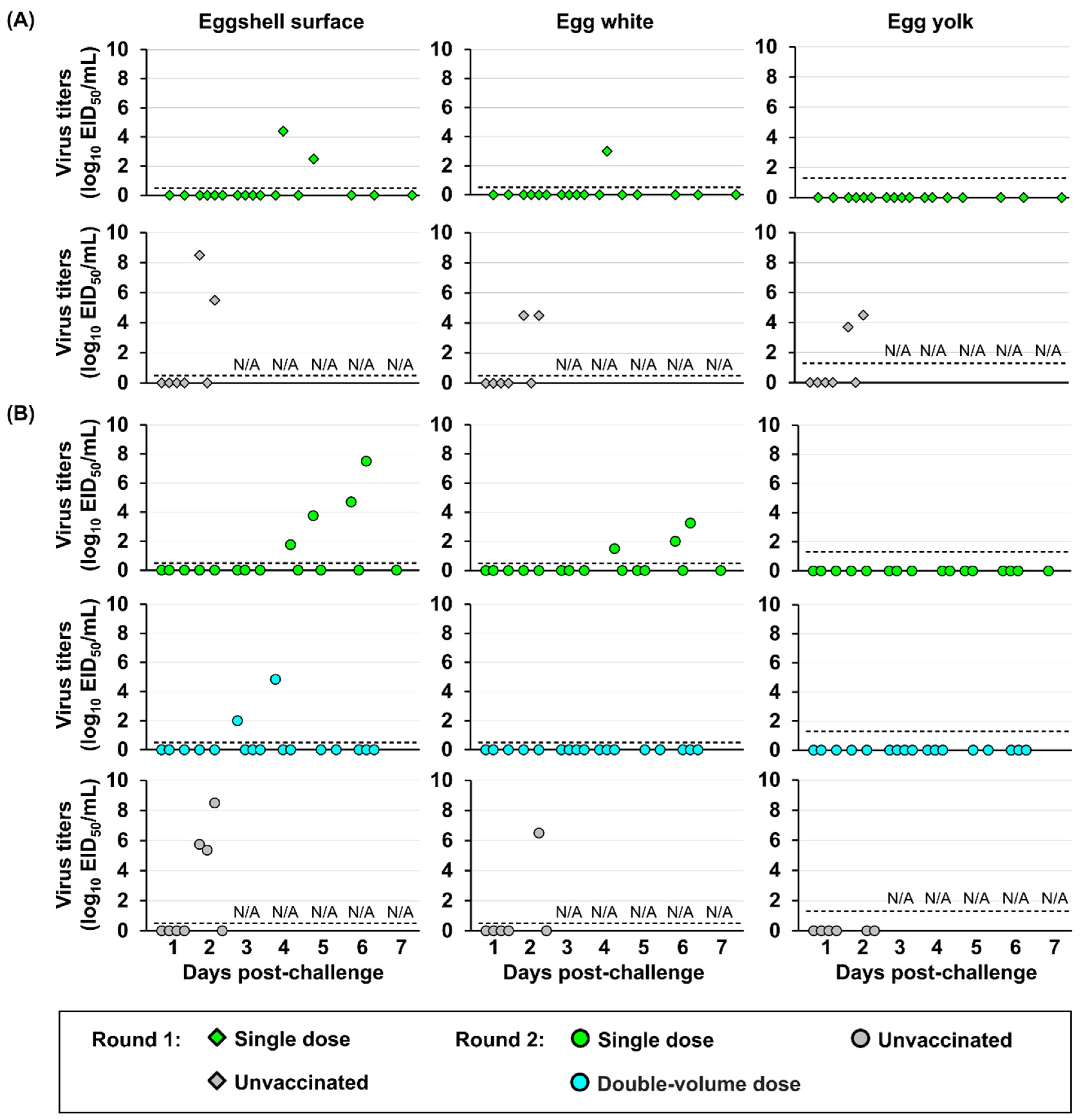

Virus contamination in egg products was evaluated. Eggs laid by hens from a single-dose vaccine group exhibited higher viral contamination than those by hens from a double-dose vaccine group (

Figure 7). In the single-dose vaccine group, the infectious virus was not only on the eggshell surface but also within the egg white, with the highest titer of 3.3 log

10 EID

50 at 6 dpc and the lowest titers of 1.5 log

10 EID

50 at 4 dpc. By contrast, in the double-volume dose group, viruses were only detected on the eggshell surface of eggs laid by hens exhibiting viral shedding in cloacal swabs, with the highest titers of 4.8 log

10 EID

50 at 4 dpc and the lowest titers of 2.0 log

10 EID

50 at 3 dpc. Notably, no detectable virus was confirmed in the egg yolk of eggs from either vaccinated group. By contrast, viruses were detected in the egg white and egg yolk and on the eggshell surface of eggs laid by unvaccinated hens.

4. Discussion

In this study, a new candidate vaccine derived from a representative field strain was established, and its protective efficacy was evaluated, comparing it with the antigenically homologous vaccine to challenge strain and a Japanese stockpiled vaccine. Furthermore, its effectiveness was assessed in multiple trials to establish and improve control strategies in the field. These results underscore the paramount importance of antigenic match between vaccine and field strains to ensure optimal effectiveness of vaccines and show potential limitations of an antigenically ideal vaccine in emergency use.

Interestingly, while the antigenic distance among AIVs is generally believed to increase proportionally to their genetic distance [

29], a divergence from this trend was observed in this study. Specifically, although clade 2.3.4, 2.3.4.4e, 2.3.4.4g, and 2.3.4.4h viruses were antigenically distant from classic group viruses, the circulating clade 2.3.4.4b viruses appeared to antigenic revert toward the classic group despite accumulating further genetic distance (

Figure 2). These findings suggest that these viruses were selected under immune pressures favoring antigenic structures similar to the classic group, instead of simply exhibiting novel antigenic properties. This occurrence can be explained by the fact that genetic changes in HA gene may not uniformly affect the key epitopes involved in immune recognition. Antigenicity can be attributed to a limited number of key amino acid residues near the receptor binding site [

30]. Amino acid position 158 on HA could be one of the key residues responsible for antigenicity, as a potential site of glycosylation that can obscure antigenic epitopes, allowing viruses to evade antibody recognition. However, no virus of clade 2.3.4.4b used in this study possessed the glycosylation site at 158–160 regions. Therefore, the efficacy of available or potential vaccines against viruses in the field, which would be obtained by routine monitoring, should be evaluated based on both genetic and antigenic analysis, rather than genetic analysis alone.

According to WOAH requirements, HI titers must be at least 1/32 (5 log

2) for protection from mortality or greater than 1/128 (7 log

2) to reduce recovery of the challenge virus [

2]. Although the HI titers of some vaccinated juvenile chickens immediately before challenge were lower than those required by the WOAH, all vaccinated juvenile chickens survived for 14 days after HPAIV challenge (

Figure 3). A high level of near-sterile protection was confirmed in both rgPR8/VN23 and NIID-002 vaccine groups, with no detectable virus shedding observed in nine out of ten chickens. This robust protective efficacy, even with suboptimal antibody levels immediately before challenge, may be correlated with the development of immunity, because the antibody response had not peaked at 21 dpv. In a previous study, the antibody titers induced by stockpiled vaccine peaked at 6–7 weeks post-vaccination and may be high for extended periods, up to 100 weeks post-vaccination [

7,

27]. Conversely, infectious viruses were detectable in four chickens vaccinated with Dk/Hok/Vac-1/04 that mismatched antigenically with the challenge strain. The increase in shed virus can be attributed to an antigenic gap between the vaccine and challenge strains. Although the antibody response is developing after the challenge, antigenic mismatch limits vaccine efficacy.

The experiment of early protection onset demonstrated that a protective effect of the vaccine against mortality was observable as early as 8 dpv, with one of four chickens surviving, despite the absence of detectable antibodies immediately before challenge (

Figure 4). These results demonstrate that the protective effect observed in the early post-vaccination period should be reflected by the continued maturation of the immune response. However, complete suppression of virus shed from vaccinated chickens is required to prevent virus spread within the flock, mitigating the risk of antigenic variant generation through continuous circulation. The infectious dose of AIVs varies significantly across bird species, previous studies have reported that at least 3.4 log

10 EID

50 viruses are required to infect chickens, but fewer than 1.0 log

10 EID

50 viruses are enough to infect ducks [

31]. These results highlight the concern that circulation of HPAIVs with low virus titer promotes the emergence of antigenicity variants through continuous infections in flocks highly sensitive to HPAIV. Therefore, effective post-vaccination surveillance strategies are indispensable in countries employing routine immunization programs.

Independent experiments in vaccinating laying hens revealed limitations under the standard single-dose regimen. Although the antibody titers immediately before challenge met the WOAH requirement of 1/32 HI (5 log

2), it was insufficient to fully protect the hens with a single dose (

Figure 5). This observation aligns with a previous study where a single dose induced a mean HI titer of 1/45 in hens but failed to provide complete protection against virus contamination in the egg products, even with an antigenic match between the vaccine and challenge strains [

32]. The temporal antibody titer induction varied between vaccinated laying hens and juvenile chickens. Antibody titers in vaccinated hens at 3 weeks post-vaccination showed a non-significant increase compared to those at 2 weeks post-vaccination. Conversely, HI titers in juvenile chickens were significantly higher than those at 2 weeks post-vaccination. Consistent with a previous study, antibody levels in vaccinated 76-week-old chickens were largely similar between 3 and 8 weeks post-vaccination, whereas a marked increase in antibodies was observed in vaccinated 4-week-old chickens [

33]. The difference in vaccine efficacy between 40-week-old hens and 4-week-old chickens may be related to the development and function of the immune system, particularly B cells that differentiate in the bursa of Fabricius. In hens, the bursa of Fabricius undergoes physiological involution beginning approximately at 10–16 weeks of age and is almost completed at 24 weeks, resulting in a replacement of the capacity to produce new B cells [

34,

35]. Although data on B-cell activity, lymphocyte count, and innate immunity were not collected in the present study, these physiological factors provide a plausible explanation for the lower vaccine efficacy observed in 40-week-old hens. Moreover, relative vaccine dosage per body weight may influence the serological response in birds, as supported by a previous study in zoo birds [

36]. Thus, the true effective dose received in hens should be updated from that in juvenile chickens. To test this hypothesis, a double-volume dose was injected into hens. Notably, a double-volume dose did not significantly change antibody titers compared with a single dose (

Figure 5). However, the double-volume dose improved clinical protection and substantially reduced virus shedding and its egg contamination, suggesting that enhanced efficacy is not solely dependent on the antibody. The specific mechanism of enhanced protection with double-volume dose is unclear and needs further investigation. Notably, HPAI vaccination policies vary between countries that permit routine vaccination and those that restrict vaccines to emergency use only. In this study, a single-dose protocol consistent with emergency-use policy was applied to evaluate vaccine efficacy under conditions where booster administration is not required. Therefore, the limited protective efficacy in 40-week-old laying hens after a single dose reflects the practical limitations of the emergency use framework in the field. Given these constraints, control strategies using vaccination must prioritize optimizing the timing, preferably administering at before 16 weeks of age, for routine use in countries that permit vaccination. In countries that adopt an emergency-only vaccination policy, including Japan, relative vaccine dosage per body weight of birds must be considered.

RT-qPCR is a highly sensitive tool for identifying H5 HPAIV in disease-free areas or during the early stages of an outbreak. However, under vaccination or endemic settings, interpreting positive RT-qPCR results becomes more complicated. In this study,

Ct values with positive results were obtained from samples of vaccinated chickens, although infectious viruses were not recovered from the same samples (

Figure S3). This discrepancy arises because viral RNA may persist long after virus clearance following vaccination or recovery, leading to positive PCR results even in protected animals. Positive PCR results can lead to misinterpretation of infection status. Differentiating between vaccinated, infected, and uninfected individuals based solely on

Ct values is challenging given the principle of gene detection diagnosis. Therefore, in the context of post-vaccination monitoring, positive qPCR results must be interpreted with caution, and virus isolation remains the gold standard for confirming active, infectious virus shedding and accurately assessing vaccine efficacy in the field.

5. Conclusions

This study rigorously evaluated a newly developed H5 avian influenza vaccine against the contemporary clade 2.3.4.4b of H5 HPAIV, comparing its efficacy with both a challenge strain-originated vaccine and the Japanese stockpile vaccine strain. The trial antigenically matched inactivated vaccine provided sufficient immunity to protect juvenile chickens with a single dose but did not fully protect hens from the circulating H5N1 HPAIV belonging to clade 2.3.4.4b. Although antigenically mismatched, the stockpiled vaccine protects against mortality but does not completely prevent virus shedding, confirming that antigenic matching is required for achieving sterile immunity. The failure to fully protect the hens suggests that the effectiveness of vaccines is affected by both antigenic variation and insufficient relative dose in older birds. These results highlight a major limitation of inactivated vaccines, where vaccine efficacy may decrease due to antigenic change or when adult birds receive an insufficient vaccine dose. Therefore, continuous surveillance of circulating strains, combined with antigenic and genetic analysis, as well as post-vaccination monitoring, is essential for early detection and timely response. Furthermore, to achieve complete protection in older birds, a refined vaccination strategy may be required, particularly under single-shot emergency use policies.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org. Figure S1: Growth kinetics of vaccine strains in embryonated chicken eggs; Figure S2: Antibody responses elicited by rgPR8/VN23 (A) and Dk/Hok/Vac-1/04 (B) vaccines against their homologous antigens; Figure S3: Virus recovery and M gene detection in a subset of swab samples from unvaccinated chickens (A), chickens vaccinated with the rgPR8/VN23 (B), and Dk/Hok/Vac-1/04 (C); Figure S4: Survival and viral shedding of vaccinated chickens challenged at various time points post-vaccination; Table S1: Primer and probe sequences used for reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction targeting the M gene; Table S2: Surveillance of avian influenza viruses (AIVs) in Vietnam from 2019 to 2024; Table S3: List of H5 AIVs used in genetic and antigenic analysis; Table S4: H5 AIVs cross-reactivity with antisera using the hemagglutination inhibition (HI) assay; Table S5: Intravenous Pathogenicity Index (IVPI) of the vaccine strains; Table S6: Geometric mean titer (GMT).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.L.N., N.I., and Y.S.; methodology, B.L.N. and N.I.; validation, B.L.N., N.I., and Y.S.; formal analysis, B.L.N.; investigation, B.L.N., L.Y.H., L.T.H., L.T.K., Y.SH., D.K., D.N.H; resources, D.H.C., D.T.N., K.T., Y.N., T.S. and Y.S.; data curation, B.L.N., N.I. and Y.S.; writing—original draft preparation, B.L.N.; writing—review and editing, B.L.N., N.I., T.H., and Y.S.; visualization, B.L.N.; supervision, N.I.; project administration, Y.S.; funding acquisition, Y.S.

Funding

This work was partially supported by the World-Leading Innovative and Smart Education Program (1801) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan. Additionally, this work was partially supported by the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) [grant numbers JP223fa627005 and JP24wm000125008].

Institutional Review Board Statement

All animal procedures were conducted under strict adherence to the guidelines established by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Hokkaido University. Ethical authorization for these experiments was obtained through approval numbers 21-0016 (approved on April 02, 2021) and 23-0053 (approved on March 30, 2023). The Faculty of Veterinary Medicine at Hokkaido University has been accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International (AAALAC International) since 2007.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the National Institute of Infectious Diseases, Japan, for kindly providing NIID-002 (A/Ezo red fox/Hokkaido/1/2022) (H5N1) (NIID-002). We sincerely thank Hokuryo Co., Ltd. (Hokkaido, Japan) for their generous support in providing the 40-week-old White Leghorn laying hens used in this study. We also sincerely thank Kyoto Biken Laboratories, Inc., Japan, for preparing and providing the vaccine used in this study with no financial compensation or commercial involvement.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors affirm that no conflicts of interest exist. Furthermore, the funding bodies played no role in the design of the study, the collection or interpretation of data, the analysis process, the manuscript preparation, or the ultimate decision regarding publication of the findings.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AIVs |

Avian influenza viruses |

| BSL-3 |

Biosafety Level 3 |

| CLD50 |

50% chicken lethal dose |

| cRBCs |

Chicken red blood cells |

| dpc |

Days post-challenge |

| dpv |

Days post-vaccination |

| EID50

|

50% egg infectious doses |

| GISAID |

Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data |

| GMT |

Geometric mean titer |

| HA |

Hemagglutination/Hemagglutinin |

| HEK293T |

Human embryonic kidney 293T |

| HI |

Hemagglutinin inhibition |

| HPAI |

High pathogenicity avian influenza |

| HPAIV |

High pathogenicity avian influenza virus |

| IVPI |

Intravenous pathogenicity index |

| MDCK |

Madin-Darby canine kidney |

| MEM |

Minimum essential medium |

| PBS |

Phosphate-buffered saline |

| NA |

Neuraminidase |

| RT-qPCR |

Reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction |

| TCID50

|

50% tissue culture infectious dose |

| WOAH |

World Organization of Animal Health |

References

- World Organisation for Animal Health. High pathogenicity avian influenza (HPAI) – situation report 76, 2025. Available online: https://www.woah.org/app/uploads/2025/11/hpai-report-76.pdf (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- World Organisation for Animal Health. Avian influenza (including infection with high pathogenicity avian influenza viruses), 2021. Available online: https://www.woah.org/fileadmin/Home/fr/Health_standards/tahm/3.03.04_AI.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- Charostad, J.; Rezaei Zadeh Rukerd, M.; Mahmoudvand, S.; Bashash, D.; Hashemi, S.M.A.; Nakhaie, M.; Zandi, K. A comprehensive review of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) H5N1: an imminent threat at doorstep. Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease 2023, 55, 102638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chrzastek, K.; Lieber, C.M.; Plemper, R.K. H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b: evolution, global spread, and host range expansion. Pathogens 2025, 14, 929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swayne, D.E. The role of vaccines and vaccination in high pathogenicity avian influenza control and eradication. Expert Review of Vaccines 2012, 11, 877–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nomura, N.; Matsuno, K.; Shingai, M.; Ohno, M.; Sekiya, T.; Omori, R.; Sakoda, Y.; Webster, R.G.; Kida, H. Updating the influenza virus library at Hokkaido University -it’s potential for the use of pandemic vaccine strain candidates and diagnosis. Virology 2021, 557, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isoda, N.; Sakoda, Y.; Kishida, N.; Soda, K.; Sakabe, S.; Sakamoto, R.; Imamura, T.; Sakaguchi, M.; Sasaki, T.; Kokumai, N.; et al. Potency of an inactivated avian influenza vaccine prepared from a non-pathogenic H5N1 reassortant virus generated between isolates from migratory ducks in Asia. Archives of Virology 2008, 153, 1685–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamatsu, M.; Tanaka, T.; Yamamoto, N.; Sakoda, Y.; Sasaki, T.; Tsuda, Y.; Isoda, N.; Kokumai, N.; Takada, A.; Umemura, T.; et al. Antigenic, genetic, and pathogenic characterization of H5N1 highly pathogenic avian influenza viruses isolated from dead whooper swans (Cygnus cygnus) found in northern Japan in 2008. Virus Genes 2010, 41, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, N.S.; Banyard, A.C.; Whittard, E.; Karibayev, T.; Al Kafagi, T.; Chvala, I.; Byrne, A.; Meruyert, S.; King, J.; Harder, T.; et al. Emergence and spread of novel H5N8, H5N5 and H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4 highly pathogenic avian influenza in 2020. Emerging Microbes and Infections 2021, 10, 148–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, Y.-G.; Lee, Y.-N.; Lee, D.-H.; Shin, J.; Lee, J.-H.; Chung, D.H.; Lee, E.-K.; Heo, G.-B.; Sagong, M.; Kye, S.-J.; et al. Multiple reassortants of H5N8 clade 2.3.4.4b highly pathogenic avian influenza viruses detected in South Korea during the winter of 2020–2021. Viruses 2021, 13, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mine, J.; Takadate, Y.; Kumagai, A.; Sakuma, S.; Tsunekuni, R.; Miyazawa, K.; Uchida, Y. Genetics of H5N1 and H5N8 high-pathogenicity avian influenza viruses isolated in Japan in winter 2021–2022. Viruses 2024, 16, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takadate, Y.; Mine, J.; Tsunekuni, R.; Sakuma, S.; Kumagai, A.; Nishiura, H.; Miyazawa, K.; Uchida, Y. Genetic diversity of H5N1 and H5N2 high pathogenicity avian influenza viruses isolated from poultry in Japan during the winter of 2022–2023. Virus Research 2024, 347, 199425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hew, L.Y.; Isoda, N.; Takaya, F.; Ogasawara, K.; Kobayashi, D.; Huynh, L.T.; Morita, T.; Harada, R.; Zinyakov, N.G.; Andreychuk, D.B.; et al. Continuous introduction of H5 high pathogenicity avian influenza viruses in Hokkaido, Japan: characterization of viruses isolated in winter 2022-2023 and early winter 2023-2024. Transboundary and Emerging Diseases 2024, 2024, 199876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiono, T.; Kobayashi, D.; Kobayashi, A.; Suzuki, T.; Satake, Y.; Harada, R.; Matsuno, K.; Sashika, M.; Ban, H.; Kobayashi, M.; et al. Virological, pathological, and glycovirological investigations of an Ezo red fox and a tanuki naturally infected with H5N1 high pathogenicity avian influenza viruses in Hokkaido, Japan. Virology 2023, 578, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Summary of status of development and availability of A(H5N1) candidate vaccine viruses and potency testing reagents, 2024. Available online: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/influenza/cvvs/cvv-zoonotic-northern-hemisphere-2024-2025/h5n1_summary_a_h5n1_cvv_20240223.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Tamura, K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2016, 33, 1870–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kida, H.; Yanagawa, R. Isolation and characterization of influenza A viruses from wild free-flying ducks in Hokkaido, Japan. Zentralblatt fur Bakteriologie, Parasitenkunde, Infektionskrankheiten und Hygiene. Erste Abteilung Originale. Reihe A: Medizinische Mikrobiologie und Parasitologie 1979, 244, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Isoda, N.; Onuma, M.; Hiono, T.; Sobolev, I.; Lim, H.Y.; Nabeshima, K.; Honjyo, H.; Yokoyama, M.; Shestopalov, A.; Sakoda, Y. Detection of new H5N1 high pathogenicity avian influenza viruses in winter 2021–2022 in the Far East, which are genetically close to those in Europe. Viruses 2022, 14, 2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isoda, N.; Twabela, A.T.; Bazarragchaa, E.; Ogasawara, K.; Hayashi, H.; Wang, Z.J.; Kobayashi, D.; Watanabe, Y.; Saito, K.; Kida, H.; et al. Re-invasion of H5N8 high pathogenicity avian influenza virus clade 2.3.4.4b in Hokkaido, Japan, 2020. Viruses 2020, 12, 1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanehira, K.; Uchida, Y.; Takemae, N.; Hikono, H.; Tsunekuni, R.; Saito, T. Characterization of an H5N8 influenza A virus isolated from chickens during an outbreak of severe avian influenza in Japan in April 2014. Archives of Virology 2015, 160, 1629–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiono, T.; Okamatsu, M.; Matsuno, K.; Haga, A.; Iwata, R.; Nguyen, L.T.; Suzuki, M.; Kikutani, Y.; Kida, H.; Onuma, M.; et al. Characterization of H5N6 highly pathogenic avian influenza viruses isolated from wild and captive birds in the winter season of 2016–2017 in northern Japan. Microbiology and Immunology 2017, 61, 387–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.T.; Firestone, S.M.; Stevenson, M.A.; Young, N.D.; Sims, L.D.; Chu, D.H.; Nguyen, T.N.; Van Nguyen, L.; Thanh Le, T.; Van Nguyen, H.; et al. A systematic study towards evolutionary and epidemiological dynamics of currently predominant H5 highly pathogenic avian influenza viruses in Vietnam. Scientific Reports 2019, 9, 7723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shichinohe, S.; Okamatsu, M.; Yamamoto, N.; Noda, Y.; Nomoto, Y.; Honda, T.; Takikawa, N.; Sakoda, Y.; Kida, H. Potency of an inactivated influenza vaccine prepared from a non-pathogenic H5N1 virus against a challenge with antigenically drifted highly pathogenic avian influenza viruses in chickens. Veterinary Microbiology 2013, 164, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ort, J.T.; Zolnoski, S.A.; Lam, T.T.-Y.; Neher, R.; Moncla, L.H. Development of avian influenza A(H5) virus datasets for nextclade enables rapid and accurate clade assignment. Virus Evolution 2025, 11, veaf058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, D.J.; Lapedes, A.S.; de Jong, J.C.; Bestebroer, T.M.; Rimmelzwaan, G.F.; Osterhaus, A.D.M.E.; Fouchier, R.A.M. Mapping the antigenic and genetic evolution of influenza virus. Science 2004, 305, 371–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, E.; Neumann, G.; Kawaoka, Y.; Hobom, G.; Webster, R.G. A DNA transfection system for generation of influenza A virus from eight plasmids. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2000, 97, 6108–6113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasaki, T.; Isoda, N.; Soda, K.; Sakamoto, R.; Saijo, K.; Hagiwara, J.; Kokumai, N.; Ohgitani, T.; Imamura, T.; Sawata, A.; et al. Evaluation of the potency, optimal antigen level and lasting immunity of inactivated avian influenza vaccine prepared from H5N1 virus. Japanese Journal of Veterinary Research 2009, 56, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishnan, M.A. Determination of 50% endpoint titer using a simple formula. World Journal of Virology 2016, 5, 85–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, B.; Reemers, S.; Dortmans, J.; de Vries, E.; de Jong, M.; van de Zande, S.; Rottier, P.J.M.; de Haan, C.A.M. Genetic versus antigenic differences among highly pathogenic H5N1 avian influenza A viruses: consequences for vaccine strain selection. Virology 2017, 503, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Cui, P.; Shi, J.; Chen, Y.; Zeng, X.; Jiang, Y.; Tian, G.; Li, C.; Chen, H.; Kong, H.; et al. Key amino acid residues that determine the antigenic properties of highly pathogenic H5 influenza viruses bearing the clade 2.3.4.4 hemagglutinin gene. Viruses 2023, 15, 2249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldous, E.W.; Seekings, J.M.; McNally, A.; Nili, H.; Fuller, C.M.; Irvine, R.M.; Alexander, D.J.; Brown, I.H. Infection dynamics of highly pathogenic avian influenza and virulent avian paramyxovirus type 1 viruses in chickens, turkeys and ducks. Avian Pathology 2010, 39, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertran, K.; Moresco, K.; Swayne, D.E. Impact of vaccination on infection with Vietnam H5N1 high pathogenicity avian influenza virus in hens and the eggs they lay. Vaccine 2015, 33, 1324–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imamura, T.; Sakamoto, R.; Sasaki, T.; Kokumai, N.; Ohgitani, T.; Sawata, A.; Lin, Z.; Sakaguchi, M. Safety test and field study of an inactivated oil-adjuvanted H5N1 avian influenza vaccine. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2010, 72, 1455–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naukkarinen, A.; Sorvari, T.E. Involution of the chicken bursa of Fabricius: a light microscopic study with special reference to transport of colloidal carbon in the involuting bursa. Journal of Leukocyte Biology 1984, 35, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romppanen, T. Postembryonic development of the chicken bursa of Fabricius: a light microscopic histoquantitative study. Poultry Science 1982, 61, 2261–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lécu, A.; De Langhe, C.; Petit, T.; Bernard, F.; Swam, H. Serologic response and safety to vaccination against avian influenza using inactivated H5N2 vaccine in zoo birds. Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine 2009, 40, 731–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree of hemagglutinin (HA) genes of H5 avian influenza viruses (AIVs) analyzed using the maximum-likelihood method with MEGA 7. Scale bar indicates nucleotide substitutions per site; node values show bootstrap support (>50%, 1000 replicates). Vietnamese isolates are marked with green circles (•), and isolates from this study are in bold. Japanese isolates from the 2022–23, 2023–24, and 2024–25 seasons are marked with blue circles (•). Strains highlighted in green, blue, and orange represent the chosen strain of the new vaccine candidate strain, challenge strain, and stock vaccine strain, respectively. Isolates selected for antigenic analysis are marked with red stars (★).

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree of hemagglutinin (HA) genes of H5 avian influenza viruses (AIVs) analyzed using the maximum-likelihood method with MEGA 7. Scale bar indicates nucleotide substitutions per site; node values show bootstrap support (>50%, 1000 replicates). Vietnamese isolates are marked with green circles (•), and isolates from this study are in bold. Japanese isolates from the 2022–23, 2023–24, and 2024–25 seasons are marked with blue circles (•). Strains highlighted in green, blue, and orange represent the chosen strain of the new vaccine candidate strain, challenge strain, and stock vaccine strain, respectively. Isolates selected for antigenic analysis are marked with red stars (★).

Figure 2.

Antigenic cartography of H5 AIVs. Vertical and horizontal axes show antigenic distances. Grid lines represent 1 unit, equivalent to 2-fold difference on hemagglutination inhibition (HI) titer. Circles indicate viruses; squares indicate sera. Colors indicate different clades. Isolated viruses in this study are written in bold. Strains highlighted in green, blue, and orange correspond to the chosen strain of the new vaccine candidate strain, challenge strain, and stock vaccine strain, respectively.

Figure 2.

Antigenic cartography of H5 AIVs. Vertical and horizontal axes show antigenic distances. Grid lines represent 1 unit, equivalent to 2-fold difference on hemagglutination inhibition (HI) titer. Circles indicate viruses; squares indicate sera. Colors indicate different clades. Isolated viruses in this study are written in bold. Strains highlighted in green, blue, and orange correspond to the chosen strain of the new vaccine candidate strain, challenge strain, and stock vaccine strain, respectively.

Figure 3.

Vaccine efficacy against H5 high pathogenicity avian influenza (HPAI) in juvenile chickens. (A) Immunological responses against the challenge strain, Fox/Hok/1/22 (H5N1). The X-axis displays time in days; 0 marks the challenge time point corresponding to 21 days post-vaccination (dpv); −7 corresponds to 14 dpv, and 14 represents days post-challenge. Open circles represent individual HI titers. Bars represent geometric mean titer. Horizontal dashed line represents limit of detection (2 log2). *Significant difference with p-value < 0.05. (B) Survival rates of chickens after challenge. Survival curves were analyzed using the Kaplan–Meier method, and differences between vaccinated and unvaccinated groups were determined by the log-rank test (p < 0.0001). (C) Virus recovery from oropharyngeal (OP) and cloacal (CL) swabs after challenge. Virus titers are expressed as log10 of the 50% tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50/mL). Horizontal dashed line represents detection limit (0.5 log10 TCID50/mL). N/A: Not available due to chicken mortality.

Figure 3.

Vaccine efficacy against H5 high pathogenicity avian influenza (HPAI) in juvenile chickens. (A) Immunological responses against the challenge strain, Fox/Hok/1/22 (H5N1). The X-axis displays time in days; 0 marks the challenge time point corresponding to 21 days post-vaccination (dpv); −7 corresponds to 14 dpv, and 14 represents days post-challenge. Open circles represent individual HI titers. Bars represent geometric mean titer. Horizontal dashed line represents limit of detection (2 log2). *Significant difference with p-value < 0.05. (B) Survival rates of chickens after challenge. Survival curves were analyzed using the Kaplan–Meier method, and differences between vaccinated and unvaccinated groups were determined by the log-rank test (p < 0.0001). (C) Virus recovery from oropharyngeal (OP) and cloacal (CL) swabs after challenge. Virus titers are expressed as log10 of the 50% tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50/mL). Horizontal dashed line represents detection limit (0.5 log10 TCID50/mL). N/A: Not available due to chicken mortality.

Figure 4.

Immune response and protection status at various time points after vaccination. The X-axis displays different groups, including groups of unvaccinated and vaccinated chickens challenged at 6, 8, 10, and 14 dpv. Individual HI antibody titers (log2) were measured before the challenge. Each dot represents a single chicken. White and black dots denote survival and mortality, respectively. Horizontal dashed line represents limit of detection (2 log2).

Figure 4.

Immune response and protection status at various time points after vaccination. The X-axis displays different groups, including groups of unvaccinated and vaccinated chickens challenged at 6, 8, 10, and 14 dpv. Individual HI antibody titers (log2) were measured before the challenge. Each dot represents a single chicken. White and black dots denote survival and mortality, respectively. Horizontal dashed line represents limit of detection (2 log2).

Figure 5.

Immunogenicity and survival rate of hens vaccinated using different regimens. (A) Immunological responses against the challenge strain. HI titers of hens with single- or double-volume dose vaccines are indicated over time. Horizontal dashed line represents limit of detection (2 log2). (B) Kaplan–Meier survival curves illustrating the survival of laying hens for the two vaccination regimens and the unvaccinated control group after the challenge. Differences among groups were determined using the log-rank test (p < 0.01).

Figure 5.

Immunogenicity and survival rate of hens vaccinated using different regimens. (A) Immunological responses against the challenge strain. HI titers of hens with single- or double-volume dose vaccines are indicated over time. Horizontal dashed line represents limit of detection (2 log2). (B) Kaplan–Meier survival curves illustrating the survival of laying hens for the two vaccination regimens and the unvaccinated control group after the challenge. Differences among groups were determined using the log-rank test (p < 0.01).

Figure 6.

Virus recovery from OP and CL swabs of laying hens following challenge under different vaccination regimens in round 1 (A) and round 2 (B). Virus titers are expressed as TCID50/mL. Horizontal dashed line represents the detection limit (0.5 log10 TCID50/mL). N/A: Not available due to chicken mortality.

Figure 6.

Virus recovery from OP and CL swabs of laying hens following challenge under different vaccination regimens in round 1 (A) and round 2 (B). Virus titers are expressed as TCID50/mL. Horizontal dashed line represents the detection limit (0.5 log10 TCID50/mL). N/A: Not available due to chicken mortality.

Figure 7.

Viral contamination in egg components (eggshell surface, egg white, and egg yolk) of laying hens following challenge with single- or double-volume dose vaccines in two independent experiment rounds, including round 1 (A) and round 2 (B). Virus titers are expressed as 50% egg infectious dose (EID50). Horizontal dashed line represents the detection limit (0.5 log10 EID50/mL for eggshell surface and egg white, 1.3 log10 EID50/mL for egg yolk). N/A: Not available due to chicken mortality.

Figure 7.

Viral contamination in egg components (eggshell surface, egg white, and egg yolk) of laying hens following challenge with single- or double-volume dose vaccines in two independent experiment rounds, including round 1 (A) and round 2 (B). Virus titers are expressed as 50% egg infectious dose (EID50). Horizontal dashed line represents the detection limit (0.5 log10 EID50/mL for eggshell surface and egg white, 1.3 log10 EID50/mL for egg yolk). N/A: Not available due to chicken mortality.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).