Submitted:

17 December 2025

Posted:

19 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Theoretical Rationale for PT/CBT-ED

3.1. Neurobiological Effects

3.1.1. Serotonergic Neurotransmission

3.1.2. Neuroplasticity

3.1.3. Neural Network Connectivity

3.2. Psychological Effects

3.2.1. Body Image

3.2.2. Psychiatric Comorbidities

3.2.3. Social Functioning

3.2.4. Social Functioning

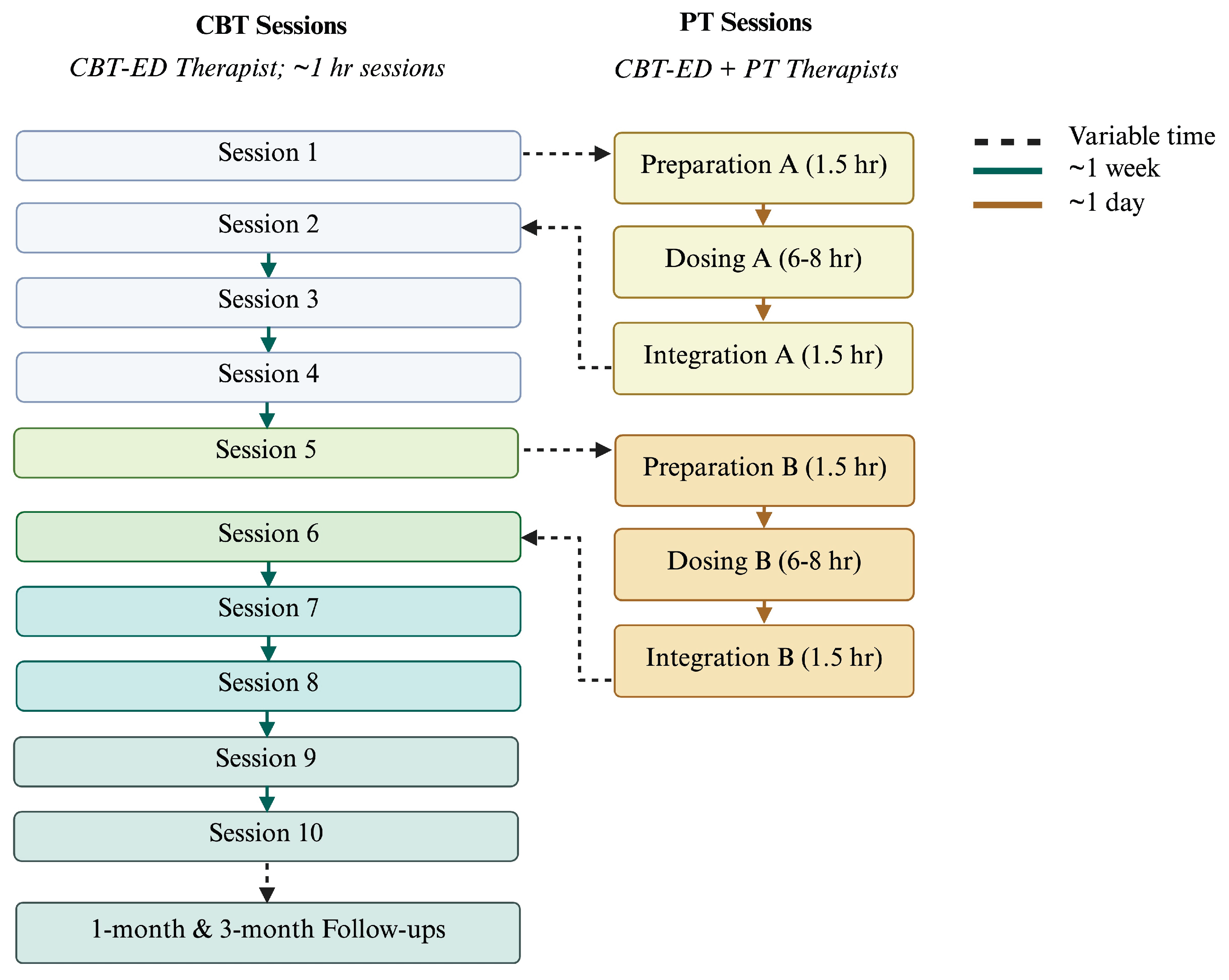

4. Considerations for PT/CBT-ED Protocol Development

5. Discussion

5.1. Implications

5.2. Limitations

5.3. Safety & Tolerability Considerations

5.4. Research Recommendations

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ED | Eating Disorders |

| AN | Anorexia Nervosa |

| BN | Bulimia Nervosa |

| BED | Binge eating disorder |

| CBT | Cognitive-behavioral therapy |

| PT | Psilocybin treatment |

| MAPS | Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies |

| MDMA | 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine |

| BDNF | Brain-derived neurotrophic factor |

References

- Accurso, E. C.; Fitzsimmons-Craft, E. E.; Ciao, A.; Cao, L.; Crosby, R. D.; Smith, T. L.; Klein, M. H.; Mitchell, J. E.; Crow, S. J.; Wonderlich, S. A.; Peterson, C. B. Therapeutic alliance in a randomized clinical trial for bulimia nervosa. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 2015, 83, 637–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebo, M.; Bonnet, M.; Laouej, O.; Defaix, C.; McGowan, J. C.; Butlen-Ducuing, F.; David, D. J.; Poupon, E.; Tritschler, L.; Gardier, A. M. Psilocybin as Transformative Fast-Acting Antidepressant: Pharmacological Properties and Molecular Mechanisms. Fundamental & Clinical Pharmacology 2025, 39, e70038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agras, W. S.; Crow, S. J.; Halmi, K. A.; Mitchell, J. E.; Wilson, G. T.; Kraemer, H. C. Outcome predictors for the cognitive behavior treatment of bulimia nervosa: Data from a multisite study. The American Journal of Psychiatry 2000, 157, 1302–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amianto, F.; Ottone, L.; Abbate Daga, G.; Fassino, S. Binge-eating disorder diagnosis and treatment: A recap in front of DSM-5. BMC Psychiatry 2015, 15, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askew, A. J.; Peterson, C. B.; Crow, S. J.; Mitchell, J. E.; Halmi, K. A.; Agras, W. S.; Haynos, A. F. Not all body image constructs are created equal: Predicting eating disorder outcomes from preoccupation, dissatisfaction, and overvaluation. The International Journal of Eating Disorders 2020, 53, 954–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attia, E.; Walsh, B. T. Eating Disorders: A Review. JAMA 2025, 333, 1242–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avanceña, A. L. V.; Vuong, L.; Kahn, J. G.; Marseille, E. Psilocybin-assisted therapy for treatment-resistant depression in the US: A model-based cost-effectiveness analysis. Translational Psychiatry 2025, 15, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailer, U. F.; Kaye, W. H. Serotonin: Imaging Findings in Eating Disorders. Current Topics in Behavioral Neurosciences 2011, 6, 59–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, G. S.; Aaronson, S. T. The Emerging Field of Psychedelic Psychotherapy. Current Psychiatry Reports 2022, 24, 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, A. M.; Holze, F.; Grandinetti, T.; Klaiber, A.; Toedtli, V. E.; Kolaczynska, K. E.; Duthaler, U.; Varghese, N.; Eckert, A.; Grünblatt, E.; Liechti, M. E. Acute Effects of Psilocybin After Escitalopram or Placebo Pretreatment in a Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Crossover Study in Healthy Subjects. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics 2022, 111, 886–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berner, L. A.; Fiore, V. G.; Chen, J. Y.; Krueger, A.; Kaye, W. H.; Viranda, T.; de Wit, S. Impaired belief updating and devaluation in adult women with bulimia nervosa. Translational Psychiatry 2023, 13, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevione, F.; Lacidogna, M. C.; Lavalle, R.; Abbate Daga, G.; Preti, A. Psilocybin in the treatment of eating disorders: A systematic review of the literature and registered clinical trials. Eating and Weight Disorders 2025, 30, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breeksema, J. J.; Niemeijer, A.; Krediet, E.; Karsten, T.; Kamphuis, J.; Vermetten, E.; van den Brink, W.; Schoevers, R. Patient perspectives and experiences with psilocybin treatment for treatment-resistant depression: A qualitative study. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 2929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, W.; Belser, A. B. Models of Psychedelic-Assisted Psychotherapy: A Contemporary Assessment and an Introduction to EMBARK, a Transdiagnostic, Trans-Drug Model. Frontiers in Psychology 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calder, A.; Mock, S.; Friedli, N.; Pasi, P.; Hasler, G. Psychedelics in the treatment of eating disorders: Rationale and potential mechanisms. European Neuropsychopharmacology: The Journal of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology 2023, 75, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calugi, S.; Dalle Grave, R. Body image concern and treatment outcomes in adolescents with anorexia nervosa. The International Journal of Eating Disorders 2019, 52, 582–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardi, V.; Tchanturia, K.; Treasure, J. Premorbid and Illness-related Social Difficulties in Eating Disorders: An Overview of the Literature and Treatment Developments. Current Neuropharmacology 2018, 16, 1122–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carhart-Harris, R. L.; Erritzoe, D.; Williams, T.; Stone, J. M.; Reed, L. J.; Colasanti, A.; Tyacke, R. J.; Leech, R.; Malizia, A. L.; Murphy, K.; Hobden, P.; Evans, J.; Feilding, A.; Wise, R. G.; Nutt, D. J. Neural correlates of the psychedelic state as determined by fMRI studies with psilocybin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2012, 109, 2138–2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carhart-Harris, R. L.; Friston, K. J. REBUS and the Anarchic Brain: Toward a Unified Model of the Brain Action of Psychedelics. Pharmacological Reviews 2019, 71, 316–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, M.; Weiselberg, E. Bulimia Nervosa/Purging Disorder. Current Problems in Pediatric and Adolescent Health Care 2017, 47, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavarra, M.; Falzone, A.; Ramaekers, J. G.; Kuypers, K. P. C.; Mento, C. Psychedelic-Assisted Psychotherapy—A Systematic Review of Associated Psychological Interventions. Frontiers in Psychology 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chisamore, N.; Johnson, D.; Chen, M. J. Q.; Offman, H.; Chen-Li, D.; Kaczmarek, E. S.; Doyle, Z.; McIntyre, R. S.; Rosenblat, J. D. Protocols and practices in psilocybin assisted psychotherapy for depression: A systematic review. Journal of Psychiatric Research 2024, 176, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coker, S.; Vize, C.; Wade, T.; Cooper, P. J. Patients with bulimia nervosa who fail to engage in cognitive behavior therapy. The International Journal of Eating Disorders 1993, 13, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crone, C.; Fochtmann, L. J.; Attia, E.; Boland, R.; Escobar, J.; Fornari, V.; Golden, N.; Guarda, A.; Jackson-Triche, M.; Manzo, L.; Mascolo, M.; Pierce, K.; Riddle, M.; Seritan, A.; Uniacke, B.; Zucker, N.; Yager, J.; Craig, T. J.; Hong, S.-H.; Medicus, J. The American Psychiatric Association Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Eating Disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry 2023, 180, 167–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crowe, M.; Manuel, J.; Carlyle, D.; Lacey, C. Experiences of psilocybin treatment for clinical conditions: A qualitative meta-synthesis. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing 2023, 32, 1025–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuerva, K.; Spirou, D.; Cuerva, A.; Delaquis, C.; Raman, J. Perspectives and preliminary experiences of psychedelics for the treatment of eating disorders: A systematic scoping review. European Eating Disorders Review 2024, 32, 980–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, H.; Attia, E. Pharmacotherapy of Eating Disorders. Current Opinion in Psychiatry 2017, 30, 452–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daws, R. E.; Timmermann, C.; Giribaldi, B.; Sexton, J. D.; Wall, M. B.; Erritzoe, D.; Roseman, L.; Nutt, D.; Carhart-Harris, R. Increased global integration in the brain after psilocybin therapy for depression. Nature Medicine 2022, 28, 844–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, L.; Price, C.; Bartel, S.; Harris, A.; Schenkels, M.; Spinella, T.; Nunes, A.; Ali, S. I.; Waller, G.; Wournell, J.; Gamberg, S.; Keshen, A. Delivering Brief Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT-T) for Eating Disorders: Examining Real-World Outcomes of a Large-Scale Training Program. The International Journal of Eating Disorders 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doss, M. K.; Považan, M.; Rosenberg, M. D.; Sepeda, N. D.; Davis, A. K.; Finan, P. H.; Smith, G. S.; Pekar, J. J.; Barker, P. B.; Griffiths, R. R.; Barrett, F. S. Psilocybin therapy increases cognitive and neural flexibility in patients with major depressive disorder. Translational Psychiatry 2021, 11, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Downey, A. E.; Chaphekar, A. V.; Woolley, J.; Raymond-Flesch, M. Psilocybin therapy and anorexia nervosa: A narrative review of safety considerations for researchers and clinicians. Journal of Eating Disorders 2024, 12, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erritzoe, D.; Smith, J.; Fisher, P. M.; Carhart-Harris, R.; Frokjaer, V. G.; Knudsen, G. M. Recreational use of psychedelics is associated with elevated personality trait openness: Exploration of associations with brain serotonin markers. Journal of Psychopharmacology (Oxford, England) 2019, 33, 1068–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evens, R.; Schmidt, M. E.; Majić, T.; Schmidt, T. T. The psychedelic afterglow phenomenon: A systematic review of subacute effects of classic serotonergic psychedelics. Therapeutic Advances in Psychopharmacology 2023, 13, 20451253231172254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fairburn, C. G. Cognitive Behavior Therapy and Eating Disorders; Guilford Press, 2008a. [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn, C. G. Eating disorders: The transdiagnostic view and the cognitive behavioral theory. In Cognitive behavior therapy and eating disorders; Guilford Press, 2008b; pp. 7–22. [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn, C. G.; Cooper, Z.; Doll, H. A.; O’Connor, M. E.; Bohn, K.; Hawker, D. M.; Wales, J. A.; Palmer, R. L. Transdiagnostic cognitive-behavioral therapy for patients with eating disorders: A two-site trial with 60-week follow-up. The American Journal of Psychiatry 2009, 166, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Q.; Chan, V. K. Y.; Chan, S. S. M.; Jiao, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, X. Efficacy and safety of psilocybin on treatment-resistant depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Research 2024, 337, 115960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fassino, S.; Daga, G. A.; Pierò, A.; Rovera, G. G. Dropout from brief psychotherapy in anorexia nervosa. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics 2002, 71, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fassino, S.; Pierò, A.; Tomba, E.; Abbate-Daga, G. Factors associated with dropout from treatment for eating disorders: A comprehensive literature review. BMC Psychiatry 2009, 9, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauvel, B.; Strika-Bruneau, L.; Piolino, P. Changes in self-rumination and self-compassion mediate the effect of psychedelic experiences on decreases in depression, anxiety, and stress. Psychology of Consciousness: Theory, Research, and Practice 2023, 10, 88–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feulner, L.; Sermchaiwong, T.; Rodland, N.; Galarneau, D. Efficacy and Safety of Psychedelics in Treating Anxiety Disorders. Ochsner Journal 2023, 23, 315–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fluoxetine Bulimia Nervosa Collaborative Study Group. Fluoxetine in the Treatment of Bulimia Nervosa: A Multicenter, Placebo-Controlled, Double-blind Trial. Archives of General Psychiatry 1992, 49, 139–147. [CrossRef]

- Frank, G. K. W.; Reynolds, J. R.; Shott, M. E.; O’Reilly, R. C. Altered temporal difference learning in bulimia nervosa. Biological Psychiatry 2011, 70, 728–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, R. R.; Gotsis, E. S.; Gallo, A. T.; Fitzgibbon, B. M.; Bailey, N. W.; Fitzgerald, P. B. The safety of psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy: A systematic review. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 2025, 59, 128–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gattuso, J. J.; Perkins, D.; Ruffell, S.; Lawrence, A. J.; Hoyer, D.; Jacobson, L. H.; Timmermann, C.; Castle, D.; Rossell, S. L.; Downey, L. A.; Pagni, B. A.; Galvão-Coelho, N. L.; Nutt, D.; Sarris, J. Default Mode Network Modulation by Psychedelics: A Systematic Review. The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology 2023, 26, 155–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godart, N. T.; Flament, M. F.; Curt, F.; Perdereau, F.; Lang, F.; Venisse, J. L.; Halfon, O.; Bizouard, P.; Loas, G.; Corcos, M.; Jeammet, P.; Fermanian, J. Anxiety disorders in subjects seeking treatment for eating disorders: A DSM-IV controlled study. Psychiatry Research 2003, 117, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, G. M.; Malievskaia, E.; Fonzo, G. A.; Nemeroff, C. B. Must Psilocybin Always “Assist Psychotherapy”? American Journal of Psychiatry 2024, 181, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorrell, S.; Hail, L.; Reilly, E. E. Predictors of Treatment Outcome in Eating Disorders: A Roadmap to Inform Future Research Efforts. Current Psychiatry Reports 2023, 25, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves, T. A.; Tabri, N.; Thompson-Brenner, H.; Franko, D. L.; Eddy, K. T.; Bourion-Bedes, S.; Brown, A.; Constantino, M. J.; Flückiger, C.; Forsberg, S.; Isserlin, L.; Couturier, J.; Paulson Karlsson, G.; Mander, J.; Teufel, M.; Mitchell, J. E.; Crosby, R. D.; Prestano, C.; Satir, D. A.; Thomas, J. J. A meta-analysis of the relation between therapeutic alliance and treatment outcome in eating disorders. The International Journal of Eating Disorders 2017, 50, 323–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grilo, C. M. Why no cognitive body image feature such as overvaluation of shape/weight in the binge eating disorder diagnosis? The International Journal of Eating Disorders 2013, 46, 208–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grilo, C. M.; Crosby, R. D.; Masheb, R. M.; White, M. A.; Peterson, C. B.; Wonderlich, S. A.; Engel, S. G.; Crow, S. J.; Mitchell, J. E. Overvaluation of shape and weight in binge eating disorder, bulimia nervosa, and sub-threshold bulimia nervosa. Behaviour Research and Therapy 2009, 47, 692–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grilo, C. M.; Ivezaj, V.; Tek, C.; Yurkow, S.; Wiedemann, A. A.; Gueorguieva, R. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and Lisdexamfetamine, Alone and Combined, for Binge-Eating Disorder With Obesity: A Randomized Controlled Trial. The American Journal of Psychiatry 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gukasyan, N.; Schreyer, C. C.; Griffiths, R. R.; Guarda, A. S. Psychedelic-Assisted Therapy for People with Eating Disorders. Current Psychiatry Reports 2022, 24, 767–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haikazian, S.; Chen-Li, D. C. J.; Johnson, D. E.; Fancy, F.; Levinta, A.; Husain, M. I.; Mansur, R. B.; McIntyre, R. S.; Rosenblat, J. D. Psilocybin-assisted therapy for depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Research 2023, 329, 115531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halmi, K. A. Perplexities of treatment resistance in eating disorders. BMC Psychiatry 2013, 13, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, B. C.; Jimerson, M.; Haxton, C.; Jimerson, D. C. Initial Evaluation, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia Nervosa. American Family Physician 2015, 91, 46–52. [Google Scholar]

- Heal-Cohen, N.; Allan, S. M.; Gauvain, N.; Nabirinde, R.; Burgess, A. Relapse in Eating Disorders: A Systematic Review and Thematic Synthesis of Individuals’ Experiences. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy 2025, 32, e70101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinkle, J. T.; Graziosi, M.; Nayak, S. M.; Yaden, D. B. Adverse Events in Studies of Classic Psychedelics: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2024, 81, 1225–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, J. T.; Preller, K. H.; Lenggenhager, B. Neuropharmacological modulation of the aberrant bodily self through psychedelics. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews 2020, 108, 526–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holze, F.; Avedisian, I.; Varghese, N.; Eckert, A.; Liechti, M. E. Role of the 5-HT2A Receptor in Acute Effects of LSD on Empathy and Circulating Oxytocin. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2021, 12, 711255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holze, F.; Vizeli, P.; Ley, L.; Müller, F.; Dolder, P.; Stocker, M.; Duthaler, U.; Varghese, N.; Eckert, A.; Borgwardt, S.; Liechti, M. E. Acute dose-dependent effects of lysergic acid diethylamide in a double-blind placebo-controlled study in healthy subjects. Neuropsychopharmacology 2021, 46, 537–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hultgren, J.; Hafsteinsson, M. H.; Brulin, J. G. A dose of therapy with psilocybin—A meta-analysis of the relationship between the amount of therapy hours and treatment outcomes in psychedelic-assisted therapy. General Hospital Psychiatry 2025, 96, 234–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irizarry, R.; Winczura, A.; Dimassi, O.; Dhillon, N.; Minhas, A.; Larice, J. Psilocybin as a Treatment for Psychiatric Illness: A Meta-Analysis. Cureus 2022, 14, e31796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M. W.; Garcia-Romeu, A.; Griffiths, R. R. Long-term follow-up of psilocybin-facilitated smoking cessation. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 2017, 43, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J. L. Harnessing neuroplasticity with psychoplastogens: The essential role of psychotherapy in psychedelic treatment optimization. Frontiers in Psychiatry 2025, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaye, W. H.; Bulik, C. M.; Thornton, L.; Barbarich, N.; Masters, K. Comorbidity of anxiety disorders with anorexia and bulimia nervosa. The American Journal of Psychiatry 2004, 161, 2215–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keegan, E.; Waller, G.; Wade, T. D. A systematic review and meta-analysis of a 10-session cognitive behavioural therapy for non-underweight eating disorders. Clinical Psychologist 2022, 26, 241–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeler, J. L.; Bahnsen, K.; Wronski, M. L.; Bernardoni, F.; Tam, F.; Arold, D.; King, J. A.; Kolb, T.; Poitz, D. M.; Roessner, V.; Treasure, J.; Himmerich, H.; Ehrlich, S. Longitudinal changes in brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) but not cytokines contribute to hippocampal recovery in anorexia nervosa above increases in body mass index. In Psychol Med; Publisher, 2024; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeler, J. L.; Kan, C.; Treasure, J.; Himmerich, H. Novel treatments for anorexia nervosa: Insights from neuroplasticity research. Eur Eat Disord Rev 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keeler, J. L.; Robinson, L.; Keeler-Schaffeler, R.; Dalton, B.; Treasure, J.; Himmerich, H. Growth factors in anorexia nervosa: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cross-sectional and longitudinal data. In World J Biol Psychiatry; Medline, 2022; Volume 23, pp. 582–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, M. B.; Herzog, D. B.; Lavori, P. W.; Bradburn, I. S.; Mahoney, E. S. The naturalistic history of bulimia nervosa: Extraordinarily high rates of chronicity, relapse, recurrence, and psychosocial morbidity. International Journal of Eating Disorders 1992, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, J. R.; Gillan, C. M.; Prenderville, J.; Kelly, C.; Harkin, A.; Clarke, G.; O’Keane, V. Psychedelic Therapy’s Transdiagnostic Effects: A Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) Perspective. Frontiers in Psychiatry 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koning, E.; Brietzke, E. Psilocybin-Assisted Psychotherapy as a Potential Treatment for Eating Disorders: A Narrative Review of Preliminary Evidence. Trends in Psychiatry and Psychotherapy 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koning, E.; Chaves, C.; Kirkpatrick, R. H.; Brietzke, E. Exploring the neurobiological correlates of psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy in eating disorders: A review of potential methodologies and implications for the psychedelic study design. Journal of Eating Disorders 2024, 12, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koning, E.; McMillan, R. M.; Keshen, A.; Hay, P.; Fernandez, A. V.; Reynolds, J.; Touyz, S. Why psychedelic-assisted therapy studies in eating disorders risk missing the mark on outcomes: A phenomenological psychopathology perspective. Journal of Eating Disorders 2025, 13, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacroix, E.; Fatur, K.; Hay, P.; Touyz, S.; Keshen, A. Psychedelics and the treatment of eating disorders: Considerations for future research and practice. Journal of Eating Disorders 2024, 12, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, A. W.; Lancelotta, R.; Sepeda, N. D.; Gukasyan, N.; Nayak, S.; Wagener, T. L.; Barrett, F. S.; Griffiths, R. R.; Davis, A. K. The therapeutic alliance between study participants and intervention facilitators is associated with acute effects and clinical outcomes in a psilocybin-assisted therapy trial for major depressive disorder. PloS One 2024, 19, e0300501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levinson, C. A.; Zerwas, S.; Calebs, B.; Forbush, K.; Kordy, H.; Watson, H.; Hofmeier, S.; Levine, M.; Crosby, R. D.; Peat, C.; Runfola, C. D.; Zimmer, B.; Moesner, M.; Marcus, M. D.; Bulik, C. M. The Core Symptoms of Bulimia Nervosa, Anxiety, and Depression: A Network Analysis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 2017, 126, 340–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lie, S. Ø.; Rø, Ø.; Bang, L. Is bullying and teasing associated with eating disorders? A systematic review and meta-analysis. The International Journal of Eating Disorders 2019, 52, 497–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linardon, J. Meta-analysis of the effects of cognitive-behavioral therapy on the core eating disorder maintaining mechanisms: Implications for mechanisms of therapeutic change. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy 2018, 47, 107–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linardon, J.; Hindle, A.; Brennan, L. Dropout from cognitive-behavioral therapy for eating disorders: A meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. The International Journal of Eating Disorders 2018, 51, 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lydecker, J. A.; White, M. A.; Grilo, C. M. Form and Formulation: Examining the Distinctiveness of Body Image Constructs in Treatment- Seeking Patients with Binge-Eating Disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 2017, 85, 1095–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, D. E.; Trottier, K. Rapid improvements in emotion regulation predict eating disorder psychopathology and functional impairment at 6-month follow-up in individuals with bulimia nervosa and purging disorder. The International Journal of Eating Disorders 2019, 52, 962–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLean, K. A.; Johnson, M. W.; Griffiths, R. R. Mystical Experiences Occasioned by the Hallucinogen Psilocybin Lead to Increases in the Personality Domain of Openness. Journal of Psychopharmacology (Oxford, England) 2011, 25, 1453–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, M. K.; Fisher, P. M.; Burmester, D.; Dyssegaard, A.; Stenbæk, D. S.; Kristiansen, S.; Johansen, S. S.; Lehel, S.; Linnet, K.; Svarer, C.; Erritzoe, D.; Ozenne, B.; Knudsen, G. M. Psychedelic effects of psilocybin correlate with serotonin 2A receptor occupancy and plasma psilocin levels. Neuropsychopharmacology: Official Publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology 2019, 44, 1328–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majić, T.; Schmidt, T. T.; Gallinat, J. Peak experiences and the afterglow phenomenon: When and how do therapeutic effects of hallucinogens depend on psychedelic experiences? Journal of Psychopharmacology 2015, 29, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marques, C.; Simão, M.; Guiomar, R.; Castilho, P. Self-disgust and urge to be thin in eating disorders: How can self-compassion help? Eating and Weight Disorders - Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity 2021, 26, 2317–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertens, L. J.; Wall, M. B.; Roseman, L.; Demetriou, L.; Nutt, D. J.; Carhart-Harris, R. L. Therapeutic mechanisms of psilocybin: Changes in amygdala and prefrontal functional connectivity during emotional processing after psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression. Journal of Psychopharmacology 2020, 34, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monson, C. M.; Wagner, A. C.; Mithoefer, A. T.; Liebman, R. E.; Feduccia, A. A.; Jerome, L.; Yazar-Klosinski, B.; Emerson, A.; Doblin, R.; Mithoefer, M. C. MDMA-facilitated cognitive-behavioural conjoint therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder: An uncontrolled trial. European Journal of Psychotraumatology n.d., 11, 1840123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteleone, P.; Brambilla, F.; Bortolotti, F.; Maj, M. Serotonergic dysfunction across the eating disorders: Relationship to eating behaviour, purging behaviour, nutritional status and general psychopathology. Psychological Medicine 2000, 30, 1099–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, R.; Straebler, S.; Cooper, Z.; Fairburn, C. G. Cognitive behavioral therapy for eating disorders. The Psychiatric Clinics of North America 2010, 33, 611–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nechita, D.-M.; Bud, S.; David, D. Shame and eating disorders symptoms: A meta-analysis. The International Journal of Eating Disorders 2021, 54, 1899–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, D. E. Psychedelics. Pharmacological Reviews 2016, 68, 264–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olson, D. E. Psychoplastogens: A Promising Class of Plasticity-Promoting Neurotherapeutics. Journal of Experimental Neuroscience 2018, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Öst, L.-G.; Brattmyr, M.; Finnes, A.; Ghaderi, A.; Havnen, A.; Hedman-Lagerlöf, M.; Parling, T.; Welch, E.; Wergeland, G. J. Cognitive behavior therapy for adult eating disorders in routine clinical care: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The International Journal of Eating Disorders 2024, 57, 249–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otterman, L. S. Research into Psychedelic-Assisted Psychotherapy for Anorexia Nervosa Should be Funded. Journal of Bioethical Inquiry 2023, 20, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paphiti, A.; Newman, E. 10-session Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT-T) for Eating Disorders: A Systematic Review and Narrative Synthesis. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy 2023, 16, 646–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peck, S. K.; Brewerton, T. D.; Fisher, H.; Trim, J.; Shao, S.; Modlin, N. L.; Kim, J.; Finn, D. M.; Kaye, W. H. Therapeutic emergence of dissociated traumatic memories during psilocybin treatment for anorexia nervosa. Journal of Eating Disorders 2025, 13, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peck, S. K.; Shao, S.; Gruen, T.; Yang, K.; Babakanian, A.; Trim, J.; Finn, D. M.; Kaye, W. H. Psilocybin therapy for females with anorexia nervosa: A phase 1, open-label feasibility study. Nature Medicine 2023, 29, 1947–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, K.; Keane, K.; Wolfe, B. E. Peripheral Brain Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) in Bulimia Nervosa: A Systematic Review. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing 2014, 28, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinna, F.; Sanna, L.; Carpiniello, B. Alexithymia in eating disorders: Therapeutic implications. Psychology Research and Behavior Management 2014, 8, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, J.; Wu, Y.; Liu, F.; Zhu, Y.; Jin, H.; Zhang, H.; Wan, Y.; Li, C.; Yu, D. An update on the prevalence of eating disorders in the general population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eating and Weight Disorders 2022, 27, 415–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raykos, B. C.; McEvoy, P. M.; Fursland, A. Socializing problems and low self-esteem enhance interpersonal models of eating disorders: Evidence from a clinical sample. The International Journal of Eating Disorders 2017, 50, 1075–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodan, S.-C.; Bryant, E.; Le, A.; Maloney, D.; Touyz, S.; McGregor, I. S.; Maguire, S. Pharmacotherapy, alternative and adjunctive therapies for eating disorders: Findings from a rapid review. Journal of Eating Disorders 2023, 11, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodan, S.-C.; Maguire, S.; Meez, N.; Greenstien, K.; Zartarian, G.; Mills, K. L.; Suraev, A.; Bedoya-Pérez, M. A.; McGregor, I. S. Prescription and Nonprescription Drug Use Among People With Eating Disorders. JAMA Network Open 2025, 8, e2522406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roseman, L.; Nutt, D. J.; Carhart-Harris, R. L. Quality of Acute Psychedelic Experience Predicts Therapeutic Efficacy of Psilocybin for Treatment-Resistant Depression. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2017, 8, 974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenblat, J. D.; Husain, M. I.; Lee, Y.; McIntyre, R. S.; Mansur, R. B.; Castle, D.; Offman, H.; Parikh, S. V.; Frey, B. N.; Schaffer, A.; Greenway, K. T.; Garel, N.; Beaulieu, S.; Kennedy, S. H.; Lam, R. W.; Milev, R.; Ravindran, A. V.; Tourjman, V.; Ameringen, M. V.; Taylor, V. The Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) Task Force Report: Serotonergic Psychedelic Treatments for Major Depressive Disorder. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. Revue Canadienne De Psychiatrie 2023, 68, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, H.; Aouad, P.; Le, A.; Marks, P.; Maloney, D.; Touyz, S.; Maguire, S. Psychotherapies for eating disorders: Findings from a rapid review. Journal of Eating Disorders 2023, 11, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutschmann, R.; Romanczuk-Seiferth, N.; Gloster, A.; Richter, C. Increasing psychological flexibility is associated with positive therapy outcomes following a transdiagnostic ACT treatment. Frontiers in Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1403718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampedro, F.; de la Fuente Revenga, M.; Valle, M.; Roberto, N.; Domínguez-Clavé, E.; Elices, M.; Luna, L. E.; Crippa, J. A. S.; Hallak, J. E. C.; de Araujo, D. B.; Friedlander, P.; Barker, S. A.; Álvarez, E.; Soler, J.; Pascual, J. C.; Feilding, A.; Riba, J. Assessing the Psychedelic “After-Glow” in Ayahuasca Users: Post-Acute Neurometabolic and Functional Connectivity Changes Are Associated with Enhanced Mindfulness Capacities. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology 2017, 20, 698–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnicker, K.; Hiller, W.; Legenbauer, T. Drop-out and treatment outcome of outpatient cognitive-behavioral therapy for anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Comprehensive Psychiatry 2013, 54, 812–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, N.; Hanstock, T. L.; Thornton, C. Dysfunctional self-talk associated with eating disorder severity and symptomatology. Journal of Eating Disorders 2014, 2, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shobeiri, P.; Bagherieh, S.; Mirzayi, P.; Kalantari, A.; Mirmosayyeb, O.; Teixeira, A. L.; Rezaei, N. Serum and plasma levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in individuals with eating disorders (EDs): A systematic review and meta-analysis. In J Eat Disord; PubMed-not-MEDLINE, 2022; Volume 10, p. 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, J. S.; Subramanian, S.; Perry, D.; Kay, B. P.; Gordon, E. M.; Laumann, T. O.; Reneau, T. R.; Metcalf, N. V.; Chacko, R. V.; Gratton, C.; Horan, C.; Krimmel, S. R.; Shimony, J. S.; Schweiger, J. A.; Wong, D. F.; Bender, D. A.; Scheidter, K. M.; Whiting, F. I.; Padawer-Curry, J. A.; Dosenbach, N. U. F. Psilocybin desynchronizes the human brain. Nature 2024, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloshower, J.; Skosnik, P. D.; Safi-Aghdam, H.; Pathania, S.; Syed, S.; Pittman, B.; D’Souza, D. C. Psilocybin-assisted therapy for major depressive disorder: An exploratory placebo-controlled, fixed-order trial. Journal of Psychopharmacology (Oxford, England) 2023, 37, 698–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smink, F. R. E.; van Hoeken, D.; Hoek, H. W. Epidemiology of eating disorders: Incidence, prevalence and mortality rates. Current Psychiatry Reports 2012, 14, 406–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sønderland, N. M.; Solbakken, O. A.; Eilertsen, D. E.; Nordmo, M.; Monsen, J. T. Emotional changes and outcomes in psychotherapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 2024, 92, 654–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steel, Z.; Jones, J.; Adcock, S.; Clancy, R.; Bridgford-West, L.; Austin, J. Why the high rate of dropout from individualized cognitive-behavior therapy for bulimia nervosa? The International Journal of Eating Disorders 2000, 28, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiger, H. Eating disorders and the serotonin connection: State, trait and developmental effects. Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience 2004, 29, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stenbæk, D. S.; Madsen, M. K.; Ozenne, B.; Kristiansen, S.; Burmester, D.; Erritzoe, D.; Knudsen, G. M.; Fisher, P. M. Brain serotonin 2A receptor binding predicts subjective temporal and mystical effects of psilocybin in healthy humans. Journal of Psychopharmacology (Oxford, England) 2021, 35, 459–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steward, T. Endocrinology-informed neuroimaging in eating disorders: GLP1, orexins, and psilocybin. Trends in Molecular Medicine 2024, 30, 321–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swinbourne, J.; Hunt, C.; Abbott, M.; Russell, J.; St Clare, T.; Touyz, S. The comorbidity between eating disorders and anxiety disorders: Prevalence in an eating disorder sample and anxiety disorder sample. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 2012, 46, 118–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, W. H.; Skau, S. On the scope of scientific hypotheses. Royal Society Open Science 2023, 10, 230607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vall, E.; Wade, T. D. Predictors of treatment outcome in individuals with eating disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Eating Disorders 2015, 48, 946–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eeden, A. E.; van Hoeken, D.; Hoek, H. W. Incidence, prevalence and mortality of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Current Opinion in Psychiatry 2021, 34, 515–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Elk, M.; Fried, E. I. History repeating: Guidelines to address common problems in psychedelic science. Therapeutic Advances in Psychopharmacology 2023, 13, 20451253231198466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Hoeken, D.; Hoek, H. W. Review of the burden of eating disorders: Mortality, disability, costs, quality of life, and family burden. Current Opinion in Psychiatry 2020, 33, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velkoff, E. A.; Rubino, L. G.; Liu, J.; Manasse, S. M.; Juarascio, A. S. Early reduction in anxiety sensitivity predicts greater reduction in disordered eating and trait anxiety during treatment for bulimia nervosa. The International Journal of Eating Disorders 2024, 57, 1791–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, G.; Penelo, E.; Nobis, G.; Mayrhofer, A.; Wanner, C.; Schau, J.; Spitzer, M.; Gwinner, P.; Trofaier, M.-L.; Imgart, H.; Fernandez-Aranda, F.; Karwautz, A. Predictors for good therapeutic outcome and drop-out in technology assisted guided self-help in the treatment of bulimia nervosa and bulimia like phenotype. European Eating Disorders Review: The Journal of the Eating Disorders Association 2015, 23, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waller, G.; Beard, J. Recent Advances in Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy for Eating Disorders (CBT-ED). Current Psychiatry Reports 2024, 26, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, B. T.; Wilson, G. T.; Loeb, K. L.; Devlin, M. J.; Pike, K. M.; Roose, S. P.; Fleiss, J.; Waternaux, C. Medication and psychotherapy in the treatment of bulimia nervosa. The American Journal of Psychiatry 1997, 154, 523–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, R.; Day, C.; Krzanowski, J.; Nutt, D.; Carhart-Harris, R. Patients’ Accounts of Increased “Connectedness” and “Acceptance” After Psilocybin for Treatment-Resistant Depression. Journal of Humanistic Psychology 2017, 57, 520–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiepking, L.; de Bruin, E.; Ghiţă, A. The potential of psilocybin use to enhance well-being in healthy individuals – A scoping review 2023. [CrossRef]

- Wolff, M.; Gukasyan, N.; Roseman, L.; Liknaitzky, P. Reframing psychedelic regulation: Tools, not treatments. Drug Science, Policy and Law 2025, 11, 20503245251348272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulff, A. B.; Nichols, C. D.; Thompson, S. M. Preclinical perspectives on the mechanisms underlying the therapeutic actions of psilocybin in psychiatric disorders. Neuropharmacology 2023, 231, 109504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xi, D.; Berger, A.; Shurtleff, D.; Zia, F. Z.; Belouin, S. National Institutes of Health psilocybin research speaker series: State of the science, regulatory and policy landscape, research gaps, and opportunities. Neuropharmacology 2023, 230, 109467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Du, Y.; Yao, Y.; Dai, W.; Yin, Y.; Wang, G.; Li, Y.; Zhang, L. Psilocybin promotes neuroplasticity and induces rapid and sustained antidepressant-like effects in mice. Journal of Psychopharmacology 2024, 02698811241249436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.; Zhang, C.; Hellerstein, D.; Feusner, J. D.; Wheaton, M. G.; Gomez, G. J.; Schneier, F. Single-dose psilocybin alters resting state functional networks in patients with body dysmorphic disorder. Psychedelics 2025, 1, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Mechanism | ED Psychopathology and CBT-ED Barriers | Psilocybin Treatment | ||

| Neurobiological | ||||

| Serotonergic neurotransmission |

Dysregulated serotonin signaling; clinical response from serotonergic medications | ↑ serotonin signaling | ||

| Neuroplasticity | ↓ markers of neuroplasticity | ↑ markers of neuroplasticity | ||

| Neural network connectivity | Maladaptive neural network connectivity; ↓ cognitive flexibility | Disrupted functional connectivity; ↑ cognitive flexibility | ||

| Psychological | ||||

| Body image | ↑ body image overvaluation | ↓ body image overvaluation | ||

| Mood | ↑ depressive and anxiety symptoms | ↓ depressive and anxiety symptoms | ||

| Social function | Social dysfunction; challenges to therapeutic alliance | Prosocial effects; strengthened therapeutic alliance | ||

| General well-being | Experiential avoidance, shame, self-criticism, low self-esteem | Self-acceptance/compassion, sense of connectedness and insight | ||

| Phase | Session | Key Activities & Topics | PT Considerations / Facilitator Guidance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phase 1: Early engagement & eating structure | 1 |

|

|

| 2 |

|

||

| 3 |

|

||

| 4 |

|

||

| Phase 2: Behavioural Experiments | 5 |

|

|

|

Phase 3: Emotional Triggers (Behavioural Experiments if needed) |

6 |

|

|

|

Phase 4: Body Image (Behavioural Experiments and/or Emotional Triggers if needed) |

7 |

|

|

| 8 |

|

||

|

Phase 5: Relapse Prevention (Body image if needed) |

9 |

|

|

| 10 |

|

||

| Follow-up Phase | 11 12 |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).