1. Introduction

While climate change is driven by global atmospheric shifts, its most acute impacts on human well-being are felt locally through the increasing frequency of extreme weather events-such as prolonged heatwaves and wildfires-which directly threaten physical health and exacerbate mental stress through displacement and infrastructure instability [

1,

2]. These environmental pressures simultaneously impose unprecedented strain on local utility grids, creating an urgent imperative for a higher standard of affordable and energy-independent dwellings capable of sustaining habitability during systemic infrastructure failures [

3,

4]. Consequently, the delivery of sustainable and affordable habitable dwelling has transcended economic policy to become a fundamental humanitarian imperative, as the escalating crisis of unsheltered homelessness leaves vulnerable populations exposed to increasing hostile environmental conditions that are no longer survivable without adequate affordable housing [

5,

6]. Furthermore, the status quo of mass unsheltered living is untenable from a public health and social equity perspective [

5], necessitating a rapid paradigm shift toward housing solutions that are not only economically accessible but also physically resilient enough to serve as sanctuary against climate volatility [

7,

8].

California currently stands at the precipice of two intersecting emergencies: a chronic housing affordability crisis and an increasingly volatile energy landscape driven by climate change. The state’s housing market remains the most expensive in the nation; as of the third quarter of 2025, the Legislative Analyst’s Office (LAO) reported that the median California home price is now more than double the national average for comparable mid-tier properties [

9]. This disparity has resulted in a profound affordability gap, with the California Association of Realtors (C.A.R.) noting that in Q2 2025, only 15% of California households earned the minimum income required to purchase a median-priced home [

10]. Furthermore, a seminal study by the McKinsey Global Institute estimated that California is in lack of approximately 3.5 million homes by 2025 to satisfy pent-up demand and meet the needs of a growing population [

11].

Simultaneously, the state’s energy grid faces unprecedented strain. As climate-induced wildfires become more frequent, utilities have increasingly relied on Public Safety Power Shutoffs (PSPS) to mitigate risk, a practice that left thousands of customers without power during critical high-heat events in late 2024 [

12]. These distinct challenges—shelter and energy—are further complicated by aggressive state mandates, such as the 2025 update to Title 24, Part 6, which requires expanded photovoltaic and battery storage capabilities for new construction [

13]. Consequently, the state is tasked with a complex objective: it must rapidly densify its housing stock to alleviate a shortfall of millions of units [

14] while simultaneously ensuring that this new load does not destabilize a fragile electrical grid.

The escalating housing crisis in California, characterized by extreme affordability deficits, is causing critical sectoral displacement of essential workers, thereby necessitating localized, entrepreneurial solutions to bolster housing supply. The profound disconnect between essential worker compensation and regional housing costs poses a direct threat to California’s key local economies, a phenomenon acutely demonstrated in Napa Valley. While the wine industry generates a total economic impact of more than

$11.7 billion annually for the county [

15], the median home price—which was approximately

$986,250 in 2022 [

16]—has created untenable living costs for middle-income residents. This sectoral displacement is evidenced by the departure of over 8,000 households earning under

$100,000 since 2005, a critical loss that includes sommeliers, chefs, and other foundational service workers vital to the region’s global appeal [

17]. This trend is not unique to Napa, as service and middle-income workers statewide face similar pressures, contributing to an overall outflow from California. Furthermore, this crisis exacerbates social equity issues, pushing essential frontline workers—such as custodians and healthcare aids—into severely overcrowded conditions, with roughly 21% of essential workers in Los Angeles County residing in overcrowded housing, double the rate of some other demographics [

18]. Recognizing the imperative for a swift, decentralized response to retain these indispensable community members, Ryan O’Connell, a former wine industry professional in the region, established How to ADU. LLC. This formation represents a localized entrepreneurial effort designed to leverage regulatory reforms for the expedited creation of Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs), thereby increasing affordable supply within the existing residential framework of the critically impacted region [

19].

Characterized by extreme cost burdens and persistent grid instability, the California energy crisis constitutes another critical threat to residents’ energy security, thereby accelerating the imperative for decentralized resilience strategies at the dwelling level. This instability is immediately felt through the state’s exorbitant electricity costs, which currently hover at approximately 31.66¢ per kilowatt-hour (kWh)—a rate more than double that of many contiguous U.S. states [

20]. Furthermore, this high cost is not matched by reliable service; major utilities have reported significant reliability deficits, with customers experiencing an average of nearly 11.9 hours of downtime per year [

20]. This utility-scale fragility is acutely worsened by climate-induced grid events. Public Safety Power Shutoffs (PSPS), mandated during periods of extreme wildfire risk, cause widespread disruption; for example, a single event in July 2024 de-energized over 3,000 customers to mitigate fire spread [

20]. This confluence of financial burden and physical instability necessitates a rapid shift toward localized energy autonomy. The integration of Battery Energy Storage Systems (BESS) within the ADU framework is thus critical, ensuring the dwelling can achieve passive survivability and maintain essential loads during these increasingly common systemic failures [

3,

4].

Conventional approaches to these crises have largely been siloed. Housing policy has focused on zoning reform and density bonuses, while energy policy has targeted grid hardening and utility-scale renewables. For instance, California’s legislature enacted several pivotal laws that catalyzed the growth of Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs), transforming them from a marginalized housing type into a primary component of the state’s housing solution. Key legislation, including AB 68 and AB 881 [

21], mandated streamlined ministerial approval for ADUs, effectively removing subjective local review processes and requiring local jurisdictions to approve conforming applications within 60 days [

21]. Concurrently, this legislative package removed previous hurdles like minimum lot size requirements and eliminated replacement parking requirements when a garage is converted to an ADU, accelerating the supply of affordable units [

22]. This pro-housing stance is directly mirrored in the state’s aggressive energy policy, primarily executed through the Building Energy Efficiency Standards (Title 24, Part 6). The 2022 Energy Code first established the Solar Photovoltaic (PV) Mandate for virtually all new residential construction, ensuring all new ADUs contribute to clean energy generation. Crucially, the subsequent 2025 Energy Code (effective January 1, 2026) expands this mandate by requiring all newly constructed single-family buildings, including ADUs, with services greater than 125 amps to be BESS-Ready (§150.0(s)) [

23]. This mandate requires specific infrastructure, such as dedicated raceways and subpanels, ensuring the residence is prepared for cost-effective battery installation. Furthermore, the state uses financial incentives like the Self-Generation Incentive Program (SGIP), which allocates substantial funding (often up to

$1.00 per Wh) through its Equity Resiliency budget to subsidize BESS for homeowners in High Fire-Threat Districts (HFTDs) who have experienced Public Safety Power Shutoffs [

24]. This tandem approach—removing bureaucratic barriers to ADU creation while subsidizing the resilient infrastructure required for BESS—forms the legal and economic foundation for the proposed synergistic solution. Rapidly expanding housing supply without integrated energy resilience risks overwhelming local distribution infrastructure, while independent residential battery retrofits remain prohibitively expensive for the average homeowner. Despite of the policy incentives mentioned above, there is still a critical lack of integrated frameworks that treat housing density and energy resilience as a unified architectural and policy objective.

The Residential Accessory Dwelling Unit (ADU) coupled with a Battery Energy Storage System (BESS) represents a powerful decentralized, scalable, and synergistic solution capable of addressing California’s dual crises simultaneously. The housing component leverages existing single-family zoning to enable rapid, incremental densification and increase the housing stock, a strategy widely validated in the literature for its ability to enhance affordability and bypass contentious, land-intensive development [

25,

26,

27]. Crucially, the integration of residential BESS transforms these new dwelling units into resilient prosumer nodes—a key concept within the literature on Distributed Energy Resources (DERs) [

28]. The BESS provides on-site power autonomy during grid failures, directly mitigating risks from Public Safety Power Shutoffs (PSPS) and extreme weather events, an effectiveness that has been quantified by federal laboratory analysis [

29]. Concurrently, it offers essential grid services, such as peak demand reduction and load shifting, necessary to stabilize the local utility infrastructure [

4]. This synergy effectively links the proposed solution to both crises: the ADU provides the affordable, climate-resilient structure, and the residential BESS provides the energy security and grid forming and support, establishing a viable model for sustainable, bottom-up urban densification.

This review paper is structured to systematically examine the synergistic relationship between accessory dwelling units (ADUs) and residential battery energy storage systems (BESS) within the context of California’s concurrent housing and energy crises, as intensified by climate change. The scope of this study is confined to residential deployment in California’s single-family zoning context and focuses on policy and technical frameworks established between 2016 and 2025. Following,

Section 2 evaluates the potential of ADUs to alleviate the housing crisis, emphasizing their critical role in rapidly expanding housing supply and improving affordability in California. Next,

Section 3 analyzes the theoretical foundations and regulatory frameworks governing ADU development. Then,

Section 4 provides a critical review of the role of residential BESS in mitigating the energy crisis and examines how the integration of BESS with ADUs may enhance energy resilience and improve grid stability. Subsequently,

Section 5 further investigates the interactions between residential BESS and the modern electrical grid. Building upon this,

Section 6 proposes an integrated synergy framework based on the Photovoltaic–Energy Storage–Direct Current–Flexibility (PEDF) system, positioning it as a unified solution to address California’s dual housing and energy challenges.

Section 7 assesses the economic feasibility and incentive structures supporting the proposed framework, while

Section 8 analyzes its environmental impacts and sustainability performance metrics.

Section 9 identifies key research gaps and unresolved challenges within the current literature. Subsequently,

Section 10 evaluates the practical implementation barriers associated with the proposed framework, and

Section 11 outlines directions for future research. Finally,

Section 12 presents the concluding remarks of this review.

2. Housing Crisis Alleviation Potentials Through ADUs

Contemporary scholarship identifies Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs) as a highly scalable housing solution, primarily due to their ability to circumvent two critical development bottlenecks: land acquisition and infrastructure expansion. By densifying existing residential parcels, ADUs significantly reduce per-unit production costs compared to multifamily infill or greenfield developments. Chapple et al. [

30] quantify this “market-feasible potential” at nearly 1.5 million new units in California, suggesting a massive capacity to address the state’s housing deficit without altering neighborhood morphology. This finding is corroborated by Wegmann and Chapple [

31], who argue that single-family zones possess significant “absorptive capacity” for new units that remains underutilized (

Figure 1).

Furthermore, ADUs offer distinct infrastructure and sustainability advantages. Unlike greenfield projects requiring extensive capital investment in roads and utilities, ADUs leverage existing municipal infrastructure. Stacy et al. [

32] note that this efficient land use reduces per-capita carbon footprints by increasing density in transit-rich areas. Brown and Palmeri [

33] extend this argument to operational energy, finding that the smaller footprint of ADUs (typically < 800 sq. ft.) results in lower energy demands compared to standard single-family homes. Economically, the absence of land costs makes ADUs a fiscally superior option for affordable housing production; Garcia and Tucker [

34] find that while developing a deed-restricted affordable unit in the Bay Area exceeds

$500,000, a private ADU can be constructed for approximately

$150,000 to

$250,000.

Table 1.

Comprehensive Comparison between Traditional Affordable Housing Project and ADU/JADU Project.

Table 1.

Comprehensive Comparison between Traditional Affordable Housing Project and ADU/JADU Project.

| Metric |

Traditional Affordable Housing Project |

ADU/JADU |

| Land Cost |

High (15-30% of total budget) |

$0 (Utilizes existing lot) |

| Infrastructure Cost |

High (New roads/sewers often needed) |

Low (Connects to existing main) |

| Permit Timeline |

2-5 Years |

< 60 Days (State Mandate) |

| Cost Per Unit |

$500k - $800k |

$150k - $250k |

From a statistical point of view, California’s ADU production has experienced a dramatic, exponential surge, often described as a “hockey stick” growth curve, directly mirroring the passage of key state legislation (

Figure 2). Prior to the effective date of the 2016 reforms (SB 1069 and AB 2299) [

35,

36,

37], ADU permitting was stagnant; in 2016, only 1,336 ADU permits were issued statewide [

26]. Following the implementation of these laws, which streamlined approval processes and reduced fee barriers, permits more than tripled to 5,154 in 2017. This upward trajectory continued unabated, fueled by subsequent legislative packages in 2019 that further removed local restrictions. By 2022, the annual number of ADU permits had skyrocketed to 24,857 [

26], representing a staggering 1,760% increase in just six years. As of 2022, ADUs accounted for approximately 19% of all new housing units permitted in California [

34], underscoring their rapid evolution from a niche housing type to a mainstream solution for the state’s housing shortage challenges.

Meanwhile, the legislative deregulation of ADUs has catalyzed a rapidly expanding “turnkey” construction industry, attracting significant venture capital into the sector to professionalize what was once a fragmented market of individual contractors. Prominent startups like Samara (incubated by Airbnb) [

38,

39] and Villa [

40] have collectively raised over

$100 million in recent funding rounds to scale prefabricated delivery models, responding to a market where ADUs now represent approximately 19% of all new housing production in California [

26]. This industrialization of “backyard homes” signals a shift toward mass-produced, factory-built housing as a primary mechanism for urban infill.

Beyond their role in increasing housing stock, studies have also found that ADUs have emerged as a critical infrastructure for multigenerational living, allowing families to adapt to changing economic and caregiving needs without displacement. This “invisible density” functions as a private social safety net; a seminal survey by the Garcia et al. [

41] revealed that 51% of ADU occupants are friends or family members of the homeowner, with 17% living rent-free and another 12% paying below-market rates. This arrangement directly counters displacement by providing affordable housing options within established support networks. Furthermore, the motivation to build is increasingly driven by caregiving needs. Recent data from Binette [

42] indicates that among adults over age 50 considering an ADU, 58% cite “providing a home for a loved one in need of care” as their primary motivation. This aligns with recent consumer sentiment analysis by Samara [

43], which found that 36% of California homeowners specifically intend to use ADUs to house aging parents or adult children, effectively using the units to bridge the gap between expensive assisted living facilities and the inaccessible entry-level housing market.

Table 2 illustrates the dichotomy in ADU deployment. While legislative reforms have successfully incentivized a speculative market focused on maximizing density and rental yield, a significant portion of ADU production remains driven by social necessity—specifically, the need for intergenerational care and non-market housing solutions, reducing community social vulnerability and strengthening social fabric at the same time.

3. Legislative and Regulatory Framework for ADUs

The legislative history of Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs) in California demonstrates a sustained and deliberate political commitment to easing the housing crisis through incremental densification. Starting with SB 1069 [

35], the state initiated a fundamental shift away from local exclusionary zoning by easing parking requirements and restricting local authority to prohibit ADUs [

35]. This initial groundwork was significantly accelerated by a package of legislation effective in 2020. AB 68 and AB 881 introduced the critical concept of ministerial approval, requiring local jurisdictions to approve conforming ADU plans within 60 days, thereby stripping away subjective and time-consuming discretionary review [

21]. Concurrently, AB 68 eliminated minimum lot size requirements and significantly reduced or abolished impact fees for smaller units [

44], addressing the economic and spatial constraints previously limiting homeowners. This cumulative body of law, which reached its zenith with measures like SB 9 [

45], effectively standardized ADU regulation statewide, transforming the ADU from a marginalized housing option into a viable, market-based tool for increasing affordable housing supply [

25].

The legislative momentum to facilitate ADU production has continued robustly beyond the foundational 2020 reforms, moving aggressively toward enabling “missing middle” housing types through streamlined processes. SB 684 (2023), known as the Starter Home Revitalization Act (effective July 2024), pioneered a CEQA-exempt, ministerial approval pathway for small-scale residential developments of 10 or fewer units/parcels [

46]. This initial framework was immediately bolstered by SB 1123 (2024) (effective July 2025), which crucially expanded the streamlining benefit of SB 684 to include vacant lots zoned for single-family residential use [

46]. These bills collectively aim to spur the creation of naturally affordable, entry-level homes by removing the lengthy discretionary review previously required under the Subdivision Map Act (SMA). Concurrently, SB 1211 (2024) (effective January 2025) delivered a massive expansion of ADU potential on multifamily parcels, significantly increasing the cap on detached ADUs from two to up to eight units [

47]. Furthermore, it disallowed local agencies from requiring replacement parking when surface parking is converted, thereby unlocking immense potential in underutilized parking lots on existing apartment properties [

48]. This sustained legislative effort by the state, summarized in

Table 3, validates the ADU and its associated housing typologies as central to California’s housing supply strategy.

4. Energy Crisis Alleviation Through BESS

The integration of residential BESS with ADUs is fundamentally driven by California’s legislative push for decentralized resilience, codified within the state’s stringent Building Energy Efficiency Standards (Title 24, Part 6). The 2025 Energy Code (effective January 1, 2026) mandates that all newly constructed single-family dwellings, including detached ADUs with services greater than 125 amps, must be certified as Energy Storage System (ESS) Ready [

23]. This specific infrastructure requirement, detailed under §150.0(s), ensures the installation of dedicated raceways, reserved panel space, and structural support during construction, which significantly lowers the future retrofit cost barrier for homeowners—an estimated reduction of

$500 to

$2,000 per installation. This policy serves a critical dual objective: first, it enables rapid BESS adoption for dwelling-level power autonomy, directly mitigating risks from Public Safety Power Shutoffs (PSPS) and climate-induced grid events [

29]. Second, by preparing the ADU to function as a prosumer node or Distributed Energy Resource (DER), the mandate facilitates participation in load shifting and demand response programs, thereby promoting localized grid stability and reducing reliance on carbon-intensive peaker plants [

4,

28]. This proactive regulatory approach is essential for ensuring that new housing stock contributes not only to supply but also to the state’s energy security targets.

The dual function of residential BESS is central to its value proposition, providing essential economic stabilization alongside dwelling security. BESS directly addresses the “Duck Curve” phenomenon characteristic of high solar penetration grids by storing Photovoltaic (PV) energy generated during low-demand midday hours for discharge during the grid’s high-demand evening peak. This crucial load shifting capability is projected to significantly reduce the need for expensive, high-emission natural gas infrastructure, which the state estimates can be offset more cost-effectively by distributed battery capacity [

3,

29]. It is estimated that residential BESS provides this crucial load shifting capability at a cost roughly 40% cheaper than constructing and operating new natural gas peaker plants to achieve the same capacity offset [

49]. Beyond economics, BESS offers immediate financial and physical security, directly mitigating the risks of climate-induced grid failure. The massive economic cost of grid instability—estimated by the CPUC to have caused statewide losses between

$10 billion and

$26 billion during past major Public Safety Power Shutoff (PSPS) events—underscores the value of residential autonomy [

50]. During climate-induced outages, such as Public Safety Power Shutoffs (PSPS), the battery enables the ADU to automatically island and sustain critical loads, thereby increasing the resilience and habitability of the dwelling unit for the resident. This function is so critical that incentive programs, such as the Self-Generation Incentive Program (SGIP) Equity Resiliency budget, specifically prioritize funding for these systems in high-risk areas to ensure vulnerable populations have access to reliable backup power during emergencies [

24]. By providing dwelling-level energy resilience, ADU BESS installations shift the financial burden of reliability away from centralized utilities and onto decentralized, resilient assets, offering homeowners and tenants guaranteed power for critical loads during emergency periods.

The inherently smaller scale of ADUs positions them as a critical element in achieving sustainable urban growth and reducing the per-capita energy burden. Compared to the average new single-family home, the construction of an ADU is estimated to reduce the residential energy consumption per capita by approximately 52% [

51]. This low-demand profile is coupled with a supply mandate: the state’s Title 24 Energy Codes prescriptively require solar Photovoltaic (PV) installation on new ADUs, guaranteeing clean power generation [

13]. When BESS is integrated to store this mandated PV generation, the system promotes complete sustainable densification and aids California in meeting its rigorous climate mandates. This decentralized, zero-carbon energy model is essential for achieving the goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 40% below 1990 levels by 2030 (SB 32), as well as advancing the mandate for 100% clean electricity by 2045 [

52]. By providing the power necessary to support electrification—such as 240V Level 2 EV charging and highly efficient heat pumps—the BESS-equipped ADU model ensures new housing stocks can contribute actively to the state’s aggressive decarbonization targets and goals.

5. Energy Crisis Alleviation Through BESS

Residential Battery Energy Storage Systems (BESS) have evolved into highly sophisticated, bidirectional grid assets, predominantly utilizing Lithium Iron Phosphate (LFP) (LiFePO

4) due to its superior thermal stability and cycle life, which often exceeds 6,000 cycles at 90% Depth of Discharge [

53]. This reliance on LFP has driven a global market expansion, which saw residential storage capacity grow by an average of 45% annually over the last three years [

54]. The residential BESS system centers around two primary components: the Power Conversion System (PCS) and the battery module. The PCS, often integrated into a hybrid inverter, manages the bidirectional power flow between the DC battery and the AC household or grid, achieving high efficiency, typically exceeding 97%, during the critical power conversion [

55]. The operational value of a typical residential BESS is derived from its three primary modes (

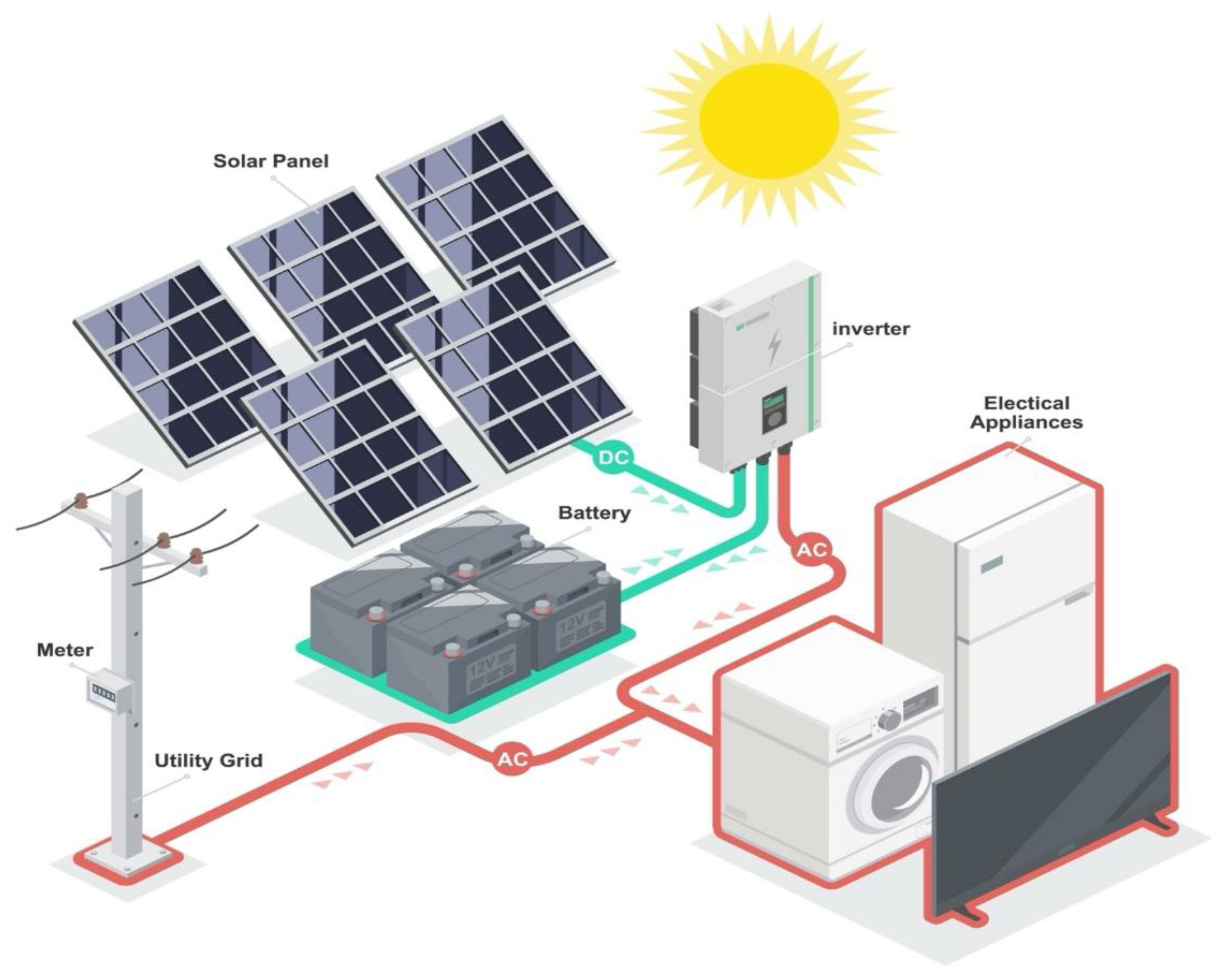

Figure 3):

Self-Consumption: Optimizing daily PV generation for use within the home, maximizing financial savings under various net metering tariffs.

Backup Power Source: Providing seamless islanding and sustained power to critical loads during grid outages (e.g., PSPS events), ensuring dwelling habitability.

Grid Services: Providing utility-directed services such as automate Demand Desponse (DR) and peak shifting, where the BESS discharges during periods of peak grid stress to stabilize local infrastructure [

24].

While the US market has historically been dominated by domestic or integrated incumbents like Tesla and Enphase, the global landscape is defined by massive vertically integrated conglomerates such as Sungrow and Canadian Solar. These manufacturers leverage immense economies of scale from the electric vehicle and utility-scale sectors to offer highly competitive residential solutions, such as Sungrow’s hybrid inverter-battery stacks and Canadian Solar’s EP Cube [

56]. However, the entry of these foreign Tier-1 manufacturers into the US residential market is currently throttled by significant geopolitical and regulatory “headwinds.”

The primary obstacle is the protectionist trade framework, specifically the escalation of Section 301 tariffs, which were significantly increased in 2024 to target Chinese-origin batteries and critical minerals, effectively raising the landed cost of imported units by 25% or more [

57]. Furthermore, the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) creates a structural disadvantage for imported hardware; specifically, the 10% Domestic Content Bonus Credit incentivizes installers and homeowners to select systems with US-manufactured components, rendering foreign systems less financially attractive despite their lower raw hardware costs [

58]. Beyond economics, “soft” barriers such as strict data security requirements for Virtual Power Plant (VPP) participation and rigorous UL 9540 safety certification standards continue to slow the penetration of non-domestic players, forcing global giants to navigate a complex compliance landscape to compete with established US incumbents [

59].

While tariffs present a financial hurdle, the most formidable barrier for foreign manufacturers—particularly those based in China, such as Sungrow and Huawei—is the escalating regulatory scrutiny regarding Critical Infrastructure Protection (CIP) [

60]. As residential BESS units are increasingly aggregated into Virtual Power Plants (VPPs), they effectively become distributed components of the bulk power system, creating a vast “attack surface” vulnerable to cyber-intrusions [

61]. U.S. regulators and utilities cite fears that cloud-connected inverters managed by foreign servers could be exploited for data espionage or, in a worst-case scenario, coordinated to execute a “distributed denial of service” (DDoS) attack on the grid by simultaneously manipulating load or export settings [

62]. Consequently, the 2024 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) restrictions often trickle down to the residential market; installers and aggregators are increasingly hesitant to deploy hardware that may be banned from federal funding or future utility VPP programs due to “foreign adversary” concerns [

63]. This pushes the market toward manufacturers who can certify strict adherence to data sovereignty protocols, often requiring domestic data hosting and rigorous third-party penetration testing as a prerequisite for market entry [

64].

The “Modern Grid” is characterized by a fundamental shift from a centralized, unidirectional delivery model to a decentralized, bidirectional network with high penetrations of variable renewable energy. This architecture requires residential BESS products to evolve from simple backup devices into active, “Grid-Interactive” assets capable of stabilizing voltage and frequency deviations in milliseconds. To support this, California’s Rule 21 interconnectivity standard now mandates that all BESS inverters be certified to UL 1741 SB (Smart Inverter) standards. This certification requires the BESS to autonomously perform complex grid-support functions, such as Volt-Var optimization (adjusting reactive power to stabilize local voltage) and Frequency-Watt response (curtailing output during over-frequency events) without human intervention [

65]. Furthermore, the modern grid requires standardized interoperability; BESS units must support the IEEE 2030.5 (SEP 2.0) communication protocol, which functions as the “universal translator” allowing utility operators to send pricing signals or dispatch commands to thousands of disparate residential batteries simultaneously. Without these advanced communication and autonomous control capabilities, a residential BESS product is functionally obsolete in the California market, as it cannot participate in the lucrative VPP markets that monetize these grid services [

55].

Residential BESS units are essential decentralized energy assets that enable grid stability by performing three coordinated services: peak shaving, load shifting, and Demand Response (DR). These services create immense economic and infrastructural value for the utility and the collective ratepayer by reducing reliance on centralized, high-cost resources. The primary economic function of residential BESS is to manage the temporal mismatch between solar generation (midday) and household consumption (evening peak).

Load Shifting Mechanism: Residential systems, typically sized between 15 kWh and 25 kWh (e.g., a Tesla Powerwall or Enphase IQ Battery) [

66], automatically charge during midday when solar PV generation is high and Time-of-Use (TOU) rates are low. The stored energy is then seamlessly discharged between 4 PM and 9 PM to meet the home’s demand.

Grid Stability Quantification: This collective action provides peak shaving or reducing the highest point of aggregated demand. Without this decentralized support, the California Independent System Operator (CAISO) must rapidly activate expensive, less efficient natural gas “peaker” plants to bridge the daily 15,000 MW (15 GW) solar ramp-down and evening load [

49]. Studies indicate that BESS achieves this necessary peak capacity offset at a cost that is significantly 40% cheaper than building and operating new gas peaker plants [

49].

DR Program Participation: Demand Response programs allow utilities to communicate with BESS units via standardized protocols (like IEEE 2030.5) and briefly dispatch them during unexpected grid emergencies or predicted heatwaves. Homeowners are compensated for allowing the battery to discharge into their home (or the grid) for a critical few hours, which is vital for preventing rolling blackouts [

65].

The residential BESS also shifts the financial risk of reliability away from the utility. For example, by storing a typical 13.5 kWh battery’s capacity, an ADU can run its critical loads (refrigerator, lights, communication) for over 12 hours during an outage. This prevents the significant economic damage caused by widespread grid failures, which have been estimated to cause statewide losses between

$10 billion and

$26 billion during past major Public Safety Power Shutoff (PSPS) events [

50]. The islanding capability of the BESS ensures the ADU remains habitable during extended outages, fulfilling the basic security mandate that grid-resilient housing provides.

California’s energy policy mandates have created the legal and technical foundation for the widespread adoption of BESS in new construction, positioning DERs as the core of its decarbonization strategy. This push is formalized within the Building Energy Efficiency Standards (Title 24, Part 6), which is updated every three years with the dual goal of increasing efficiency and staying cost-effective for ratepayers [

23]. The initial policy step was the Solar Photovoltaic (PV) Mandate, which became effective in 2020 for new residential construction. This mandate requires most new single-family homes and low-rise multifamily buildings to include a solar PV system sized to offset the building’s annual electricity usage [

67]. Critically, this requirement applies to newly constructed ADUs of any size [

67]. The mandate ensures that new housing stock is immediately carbon-reducing and provides the necessary DC energy source for a future BESS installation. Furthermore, the ability to pair BESS with PV allows builders to reduce the required solar system size, providing compliance flexibility and cost control [

68].

The evolution of the code has shifted from merely requiring generation (PV) to mandating system-readiness for energy storage. The 2022 Energy Code introduced the Energy Storage System (ESS) Ready requirements, which mandate that all newly constructed single-family buildings (including new detached ADUs) must install the necessary electrical infrastructure to support a future battery system [

67].

This requirement, detailed in §150.0(s), ensures the following infrastructure is in place:

Dedicated Raceway: A raceway (conduit) of at least one inch from the main service panel to a subpanel or designated location.

Reserved Capacity: A minimum busbar rating of 225 amps in the main panelboard to handle the future BESS load.

Critical Loads: Provision for at least four branch circuits to be supplied by the future ESS, ensuring critical functions like the refrigerator and lighting near egress are supported during an outage.

By enforcing the ESS-Ready mandate, the state significantly lowers the retrofit cost barrier for BESS installation and proactively ensures new housing stock is equipped for load flexibility and grid resilience. This strategy supports California’s long-term system cost (LSC) goals and its commitment to reducing peak cooling energy demand on the grid [

69].

These mandates are fully aligned with the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) DER Action Plan, which seeks to modernize the electric grid and coordinate policies across proceedings related to affordability, load flexibility, and market integration [

70]. The mandatory integration of PV and BESS readiness in new ADUs serves the DER Action Plan’s vision by:

Maximizing Societal Value: Ensuring new housing contributes to statewide decarbonization goals.

Promoting Reliability: Creating decentralized assets (BESS) that improve local grid reliability during high-stress periods.

Encouraging Electrification: Strongly favoring electric heat pump systems and electric readiness, accelerating the shift away from natural gas in the built environment.

This comprehensive regulatory framework transforms the ADU from a simple housing unit into a strategic, grid-supporting dwelling asset, essential for the state’s transition to a high-DER future

6. PEDF Architecture Synergy: Photovoltaic-Energy Storage-Direct Current-Flexibility ADUs as a Unified Solution

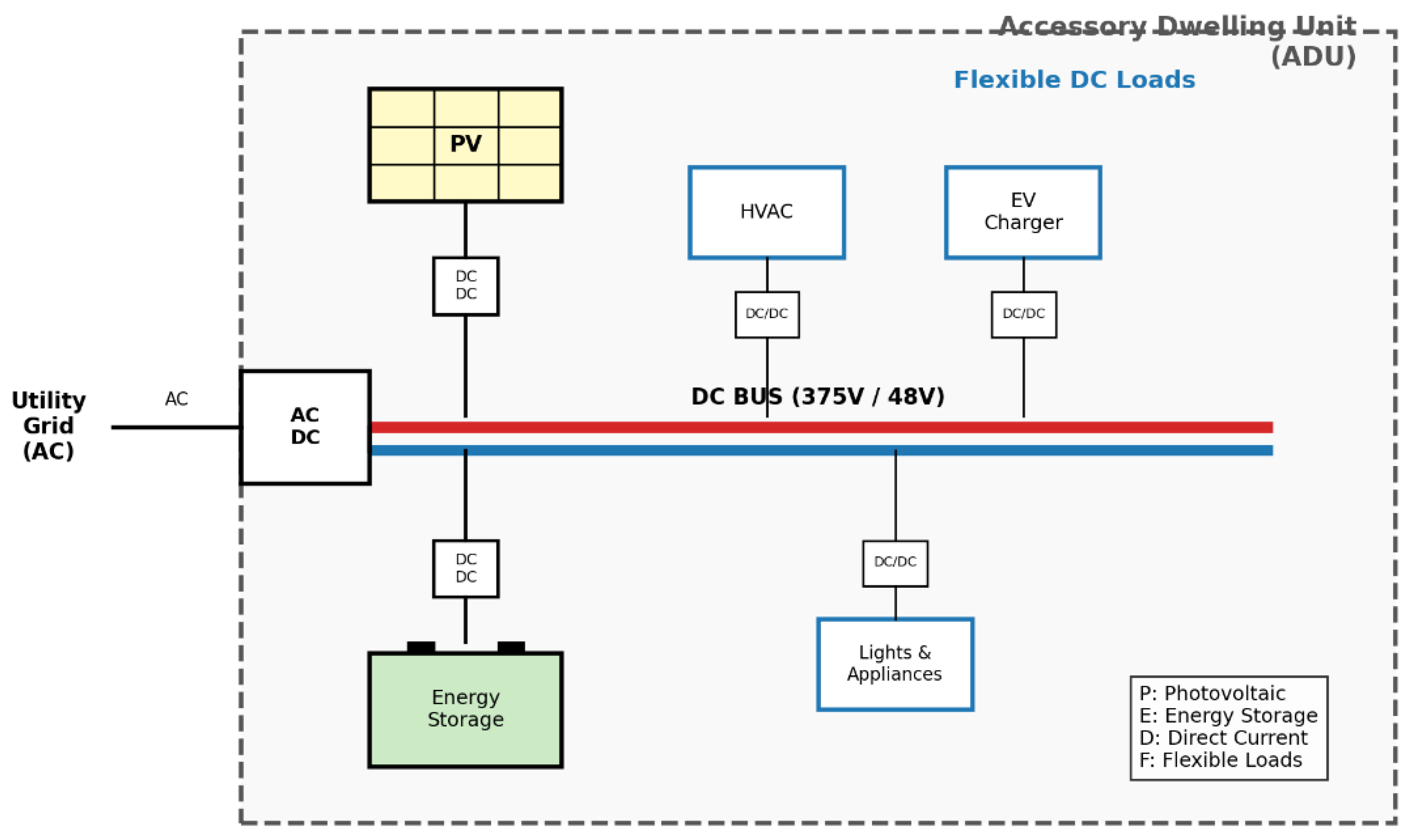

The deployment of PEDF (

Photovoltaic-

Energy Storage-

Direct Current-

Flexibility,

PEDF) architecture within Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs) offers a transformative, unified solution to California’s intersecting housing shortage and grid instability crises. By shifting ADUs from passive grid burdens to active, decentralized energy nodes, the PEDF framework leverages an internal DC distribution topology to eliminate redundant AC-DC conversion losses, thereby maximizing the efficiency of on-site solar capture and battery energy storage. PEDF (Photovoltaics, Energy storage, Direct current, and Flexibility) refers to a novel architecture power distribution system constructed via renewable energy generation (such as photovoltaics), energy storage, DC distribution, and flexible energy consumption to adapt to the requirements of carbon neutrality goals [

71,

72].

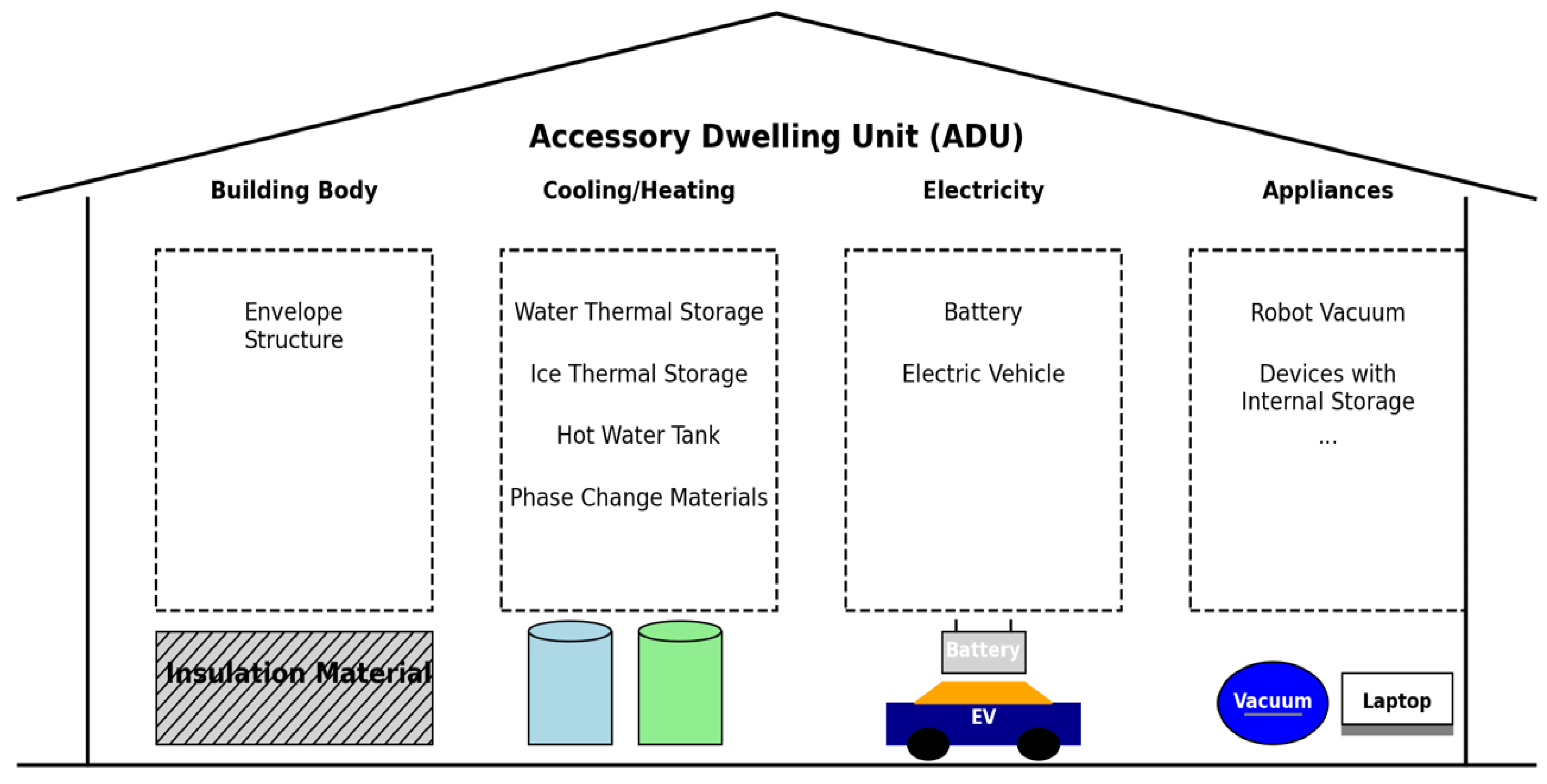

Figure 4 illustrates the fundamental configuration of the PEDF system. Deploying photovoltaic panels on ADU surfaces to fully utilize ADUs as producers of renewable energy (such as photovoltaics) is a crucial pathway for achieving low-carbon building development. Energy storage serves as a vital means for ADU energy accumulation and regulation, requiring a holistic consideration of storage methods at the ADU level; notably, electric vehicles parked in the vicinity can serve as effective energy storage resources. Furthermore, the application of Direct Current (DC) is a key approach for the efficient utilization of on-site photovoltaics and high-efficiency electromechanical equipment. Devices within the system are connected to the DC bus via DC/DC converters, thereby establishing a DC distribution system within the ADU. The ultimate goal of PEDF ADUs is to achieve comprehensive energy flexibility, transforming ADUs from mere passive loads in traditional energy systems into ‘three-in-one’ integrated complexes capable of renewable energy production, self-consumption, and energy regulation and storage. This transformation represents a critical function that ADUs must fulfill to meet the requirements for constructing a future low-carbon energy system.

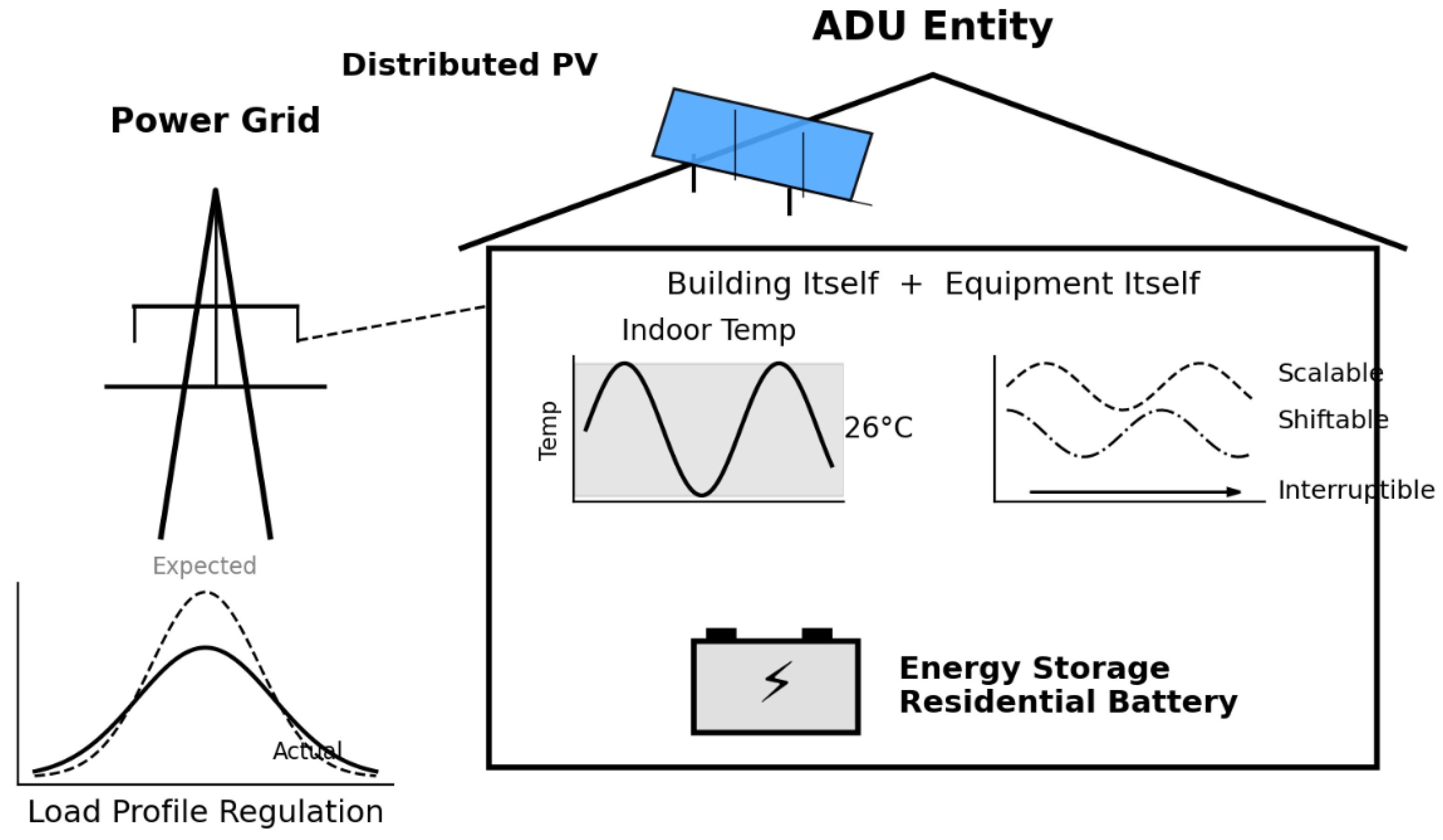

Conventionally, the residential energy infrastructure is predicated on satisfying the operational requisites of the dwelling unit—encompassing thermal regulation and electrical loads—thereby relegating the residence to the role of a passive energy consumer. In this centralized paradigm, internal utilization demands are met exclusively through external energy importation, primarily via grid electricity and fossil fuel sources such as natural gas [

73]. Consequently, energy conservation objectives within this framework are realized solely through the optimization of internal consumption systems, lacking the capacity for active generation or bidirectional flexibility. Under the strategic guidance of the ‘Dual Carbon’ mandates, residential energy systems are currently confronted with elevated developmental exigencies, necessitating a paradigm shift from fundamental energy conservation to comprehensive low-carbon innovation. These decarbonization imperatives dictate that dwelling units must decouple from traditional fossil fuel reliance, positioning the comprehensive electrification of residential energy consumption as the foundational step toward net-zero future. Furthermore, within the context of this electrification, it is imperative to reconceptualize the strategic role of the dwelling unit within the macro-energy architecture; consequently, enhancing the

flexibility of residential energy systems has emerged as a critical operational objective.

The future electric power system is poised to transition into a net-zero infrastructure predominantly anchored by renewable energy sources, specifically wind and solar photovoltaics (PV). However, the continued expansion of these variable resources necessitates the resolution of critical implementation challenges, particularly regarding optimal spatial deployment, effective grid accommodation (assimilation), and the requirement for robust regulation and energy storage capabilities. Consequently, driven by the imperatives of low-carbon energy development, the strategic positioning of ADUs within the grid architecture has undergone a fundamental paradigm shift. While retaining their baseline function as energy consumers, dwelling units are now required to evolve into producers of renewable energy (e.g., photovoltaics) while simultaneously responding to external supply-side volatility through active demand-side regulation [

74]. In essence, the dwelling unit is transforming from a singular passive load into an integrated entity capable of unified energy generation, consumption, and modulation [

75]. The ‘Photovoltaic-Energy Storage-Direct Current-Flexibility’ (PEDF) building has been formally proposed as the novel residential energy system specifically designed to realize this objective [

76] (

Figure 5).

The construction of PEDF ADUs represents a pivotal challenge that this emerging technology must address. The dwelling system is not merely the combined application of solar photovoltaics or any single technology, nor can its objectives be achieved through a simplistic aggregation of ‘Photovoltaics,’ ‘Energy Storage,’ ‘Direct current,’ and ‘Flexibility.’ Rather, the rational construction of a PEDF system requires multi-faceted synergy. Only through such coordination can buildings be successfully transformed into ‘three-in-one’ integrated complexes within the energy system, uniting the functions of production, consumption, and regulation/storage. The detailed illustration regarding each part is elaborated in the following:

Solar Photovoltaics: Maximizing Feasible Deployment

The deployment of renewable energy technologies, particularly solar photovoltaics (PV), is fundamentally contingent upon available surface area. Photovoltaic modules require specific installation space to efficiently convert solar irradiation into clean, decarbonized electricity. Consequently, the building envelope—specifically the rooftop and facade—emerges as a critical, spatially defined resource. This inherent capacity serves as the foundational requirement for buildings to transition from being simple electrical loads to active renewable energy producers. Thus, Determining the maximum potential contribution of dwelling units and quantifying their solar photovoltaic (PV) installation capacity are pivotal questions that must be addressed in the process of fully leveraging renewable resources and constructing the next-generation power system.

Studies found that the technical potential of solar photovoltaic (PV) capacity within California’s residential sector is immense, yet its deployment remains significantly below its full capability potentials [

77,

78]. Based on EIA [

78], While the installed capacity in small residential systems surpassed 12GW by late 2023, establishing the state as already a clean energy leader within the nation, the market for new residential solar installations saw a sharp 45% decline in 2024, stemming primarily from the transition to the state’s new net billing policy [

79]. Quantifying the full, theoretical potential of approximate 10 billion square feet of total usable rooftop area reveals the scale of the untapped solar resource: analyses estimate that California possesses the technical potential to install 128.9 GW of rooftop solar panels on existing buildings that include commercial, residential, and industrial sectors, capable of generating enough energy around 273,750 GWh per year to offset nearly 100% of California’s total electricity consumption in 2022 [

77,

80]. Most of this potential resides within the residential domain, necessitating robust policy to drive utilization. This is achieved through the 2022 Energy Code’s PV mandate, which prescriptively requires every new residential dwelling unit, including Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs), to install PV sized to offset its annual consumption [

67]. This mandate guarantees continuous, incremental growth of the residential PV fleet, making the integration of Battery Energy Storage Systems (BESS) essential to effectively shift the value of this vast, mandated resource toward the evening peak and ensure the state meets its ultimate goal of 100% clean energy by 2045.

A second critical research vector for advancing building-integrated photovoltaics (BIPV) involves developing effective utilization strategies and optimizing the synergy between energy production and consumption. Specifically, at the scale of the individual dwelling unit, pivotal attention must be directed toward the precise temporal and quantitative matching between the unit’s photovoltaic generation profile, and its internal energy consumption demands. Given the varying energy consumption characteristics across building typologies, internal energy usage patterns exhibit considerable temporal volatility. Furthermore, photovoltaic generation capacity is influenced by multiple factors, including panel performance, installation methodology, and local solar irradiance. Consequently, the relationship between a dwelling unit’s internal load profile and its on-site PV generation necessitates in-depth scholarly inquiry. This analysis must move beyond a simplistic comparison of annual totals, focusing critically on the correlation between hourly consumption characteristics and hourly PV output profiles to accurately determine the potential for optimal dwelling unit self-consumption.

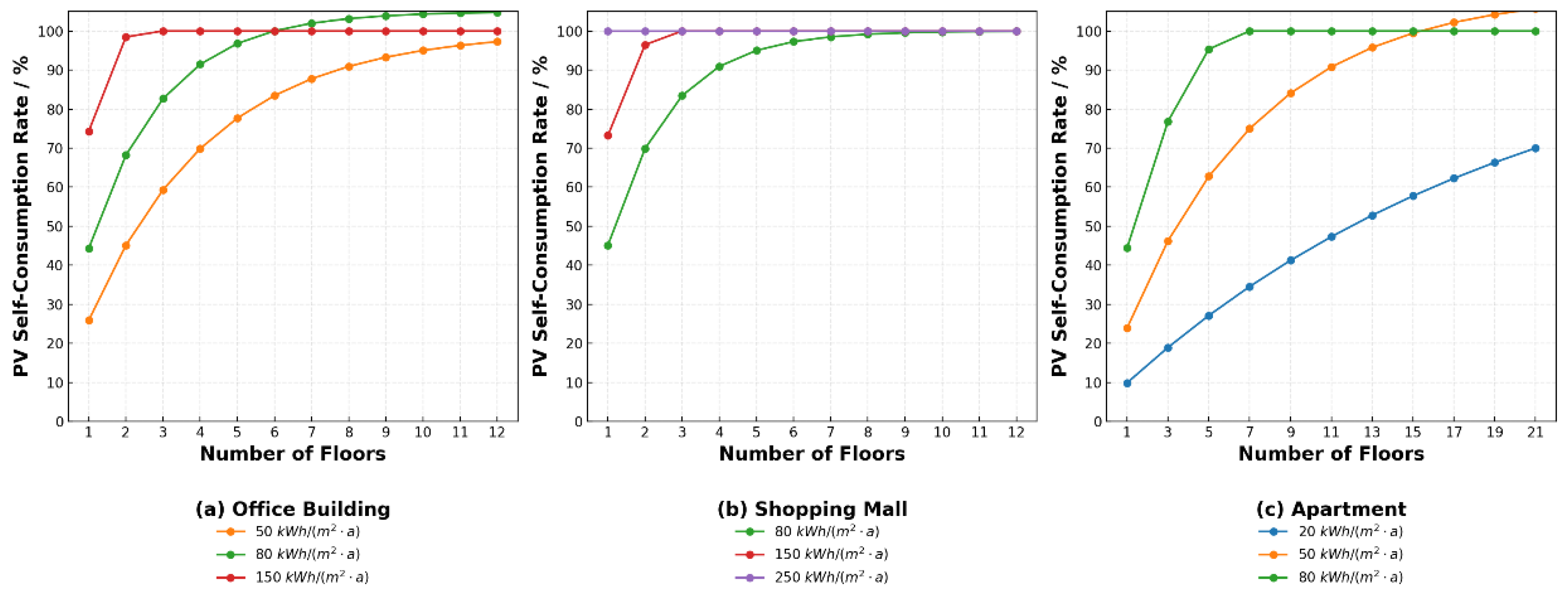

From the perspective of PEDF building construction requirements, it is essential to clearly define the pivotal role of buildings as renewable energy prosumers, distinguishing their primary orientation as either energy producers or self-consumption-dominated entities. Based on the electricity consumption characteristics of typical buildings, a quantitative characterization must be made regarding the hourly variation patterns between available photovoltaic generation resources and internal energy demand (

Figure 6) [

81].

Figure 6 shows that for vertical commercial typologies—specifically office structures exceeding six stories—operational protocols frequently mandate a ‘zero-export’ or complete self-consumption strategy. This paradigm necessitates the total in-situ absorption of photovoltaic generation, thereby precluding reverse power flows to the utility network. By maximizing the utilization of available on-site renewable solar resources, the system architecture is designed to mitigate bidirectional grid interaction; consequently, the external grid functions exclusively as a unidirectional supplier to satisfy residual load deficits, rather than serving as a buffering medium for excess generation. On the other hand, regarding high energy-intensity commercial typologies, such as retail complexes and shopping mall, structures exceeding three stories generally possess a load profile sufficient to achieve complete photovoltaic self-consumption. In contrast, low-rise structures (two stories or fewer), provided that available surface resources are maximally exploited for PV deployment, should be explicitly designated as critical energy producers. Beyond satisfying internal demand via effective energy storage strategies—which mitigate the temporal misalignment between solar generation and operational consumption—these units possess the capacity to export surplus energy. Consequently, for most of their operational duration, such low-rise entities can sustain a net-positive export status, supplying the external grid without requiring inbound power transmission.

For example, in contrast to high-density commercial structures, low-rise residential dwelling entities—exemplified by Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs) — exhibit a favorable surface-to-volume ratio, allowing on-site photovoltaic generation to frequently surpass dwelling units’ internal operational demands. Consequently, these units are uniquely positioned to evolve beyond simple self-sufficiency, functioning instead as net-positive distributed generation nodes that export surplus zero-carbon energy to support the broader utility grid. Therefore, we postulate that the vast majority of Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs) possess the capacity to leverage on-site photovoltaic power resources to effectively resolve internal energy demands while simultaneously exporting surplus power to the utility network. This capability identifies the ADU as a residential typology with profound photovoltaic utilization potential, positioning it to become a pivotal source of distributed clean energy within the future net-zero power system architecture.

Consequently, contingent upon variations in typology, functional program, and physical scale, the built environment can be broadly delineated into two distinct operational paradigms: those characterized by ‘self-generation with complete in-situ absorption’ (zero-export) and those defined by ‘generation primarily for grid export’ (net-positive). It is posited that the vast preponderance of contemporary dwelling units’ stock will align with one of these two primary classifications. Even for the minority of structures occupying the intermediate spectrum, their operational profiles are expected to exhibit a distinct polarity, functioning predominantly as either net exporters or self-consumers during most operational intervals. Within the framework of the ‘Photovoltaic-Energy Storage-Direct Current-Flexibility’ (PEDF) architecture, the inherent attributes of ‘Energy Storage’ and ‘Flexibility’ can be strategically leveraged to augment on-site photovoltaic self-consumption. This optimization effectively mitigates the complex grid-interconnection challenges currently impeding the wide-scale deployment of distributed building photovoltaics. Premised on the mandate of ‘maximizing feasible deployment’, this system architecture simultaneously achieves high utilization rates—thereby mitigating solar curtailment—while ensuring a predominantly unidirectional interaction with the utility grid. Consequently, this operational stability constitutes a fundamental functional requirement of the PEDF residential dwelling unit and represents one of its most significant systemic advantages.

Energy Storage: Unlocking Latent Potential, Optimizing Configuration

The transition toward a next-generation power system, predominantly anchored by variable renewable energy (VRE) sources such as wind and solar photovoltaics, necessitates the resolution of inherent intermittency and volatility challenges, requiring the deployment of substantial regulation and energy storage resources [

82]. Currently, the primary storage modalities under consideration encompass electrochemical batteries, thermal energy storage, pumped hydroelectric storage, compressed air energy storage (CAES), flywheels, and hydrogen. Each of these technologies corresponds to distinct temporal scales, applicable for addressing regulation requirements across varying capacities and durations. However, a significant economic disparity remains a critical bottleneck: regulation and storage technologies are currently prohibitively expensive relative to generation. For instance, while lithium-ion battery pack prices have fallen to approximately

$0.14/Wh (

$139/kWh), fully installed residential battery systems in the U.S. often command premiums exceeding

$1.30/Wh (

$1,300/kWh) [

83,

84]. In stark contrast, photovoltaic generation—which allows for widespread, large-scale application—has achieved a dramatically lower cost basis, with module costs stabilizing around

$0.30/W and utility-scale system costs approaching

$1.00/W [

85]. Consequently, the high capital cost of storage relative to generation constitutes a formidable barrier to the successful construction of a future low-carbon power system dominated by variable renewable energy.

Achieving the requisite grid-scale regulation for a net-zero power system via exclusive reliance on conventional assets, such as electrochemical batteries, entails prohibitive capital costs, underscoring the urgent need for economically viable flexibility alternatives. To address this cost barrier, two distinct pathways have emerged. The first prioritizes technological innovation to suppress the Levelized Cost of Storage (LCOS), a primary objective of federal initiatives like the U.S. Department of Energy’s ‘Energy Earthshots’ [

86]. The second, and perhaps more immediate pathway, seeks to mitigate the aggregate demand for dedicated storage capacity by leveraging demand-side flexibility; herein, the building sector emerges as a pivotal, underutilized regulation resource. Under this paradigm, the definition of ‘energy storage’ must transcend traditional modalities—such as chemical batteries, compressed air, or hydrogen—to encompass the inherent ‘virtual storage’ capabilities of the built environment. Viewed through the lens of Grid-Interactive Efficient Buildings (GEBs) and the PEDF framework, diverse building sub-systems—ranging from HVAC thermal inertia to controllable electric loads—are re-conceptualized as distributed storage assets. Consequently, a rigorous re-characterization of these building components is essential to quantify their potential to function as active resources within the ‘Solar-Storage-DC-Flexibility’ system, effectively displacing the need for expensive dedicated storage hardware [

87,

88].

The spectrum of available energy storage modalities within the built environment—ranging from passive structural reservoirs to active mechanical systems—is delineated in

Figure 7. Fundamentally, the building envelope possesses significant thermal inertia, which, when synergized with HVAC operations, functions as a critical ‘passive’ storage resource. This is complemented by ‘active’ Thermal Energy Storage (TES) technologies, such as ice and chilled water systems, which are widely deployed in the U.S. commercial sector to execute peak load shifting strategies [

89]. Extensive scholarship has validated the efficacy of utilizing the building fabric itself as a battery. For instance, Xu et al. (Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory) demonstrated through field tests that optimized pre-cooling strategies could shift 80% to 100% of the electrical cooling load away from peak utility windows without generating occupant thermal comfort complaints [

90]. Regarding air-side flexibility, Hao et al. established that Variable Air Volume (VAV) fan systems can modulate airflow to provide regulation services—reducing fan power significantly for durations up to an hour without compromising Indoor Air Quality (IAQ) [

91]. Furthermore, predictive control studies by Henze et al. [

92] confirm that leveraging a building’s intrinsic thermal mass can significantly flatten heating and cooling demand curves, achieving flexibility without additional capital investment [

92]. Finally, the electrification of heating systems positions Heat Pumps as pivotal flexibility assets; specifically, Ground Source Heat Pumps (GSHP) effectively utilize the subsurface as a seasonal thermal battery, realizing long-duration energy transfer distinct from short-term diurnal shifts [

93].

Beyond the established thermal storage capabilities of HVAC systems, the built environment encompasses a broader spectrum of underutilized flexibility assets, most notably Electric Vehicles (EVs) and miscellaneous electric loads (MELs) with internal storage. Preliminary behavioral studies indicate a high degree of spatiotemporal synchronization between EV charging patterns and building occupancy, effectively characterizing the EV as a ‘mobile building’ or transient energy reservoir [

94]. Consequently, EVs are increasingly recognized not merely as transportation loads, but as critical bidirectional assets capable of providing robust regulation services to building energy systems through Vehicle-to-Building (V2B) and Vehicle-to-Grid (V2G) integration. While transportation and power systems literature has extensively documented the grid-level storage potential of EV fleets [

95], a distinct gap remains in characterizing this resource from the building’s perspective. Specifically, further research is required to quantify the available battery capacity within a building’s distinct functional boundary and determine the magnitude of regulation services these ‘mobile nodes’ can reliably provide. Furthermore, the aggregation of decentralized appliance-level storage—such as uninterruptible power supplies (UPS) and battery-integrated electronics—represents a theoretical but largely untapped reservoir of distributed storage. However, the effective orchestration of these dispersed, low-capacity assets and the quantification of their collective load-shifting potential remain areas necessitating rigorous empirical investigation [

96].

Consequently, the building entity functions conceptually as a unified ‘Virtual Battery’ capable of bidirectional energy modulation, thereby establishing itself as a critical regulation node within the macro-energy infrastructure [

97]. Premised on the maximization of these intrinsic flexibility assets—such as thermal inertia and EV integration—the sizing of electrochemical battery energy storage system (BESS) within the PEDF architecture demands a rigorous optimization strategy. The configuration must strike an economic balance: ensuring sufficient regulation capacity to meet dwelling-level resilience mandates while strictly minimizing capital expenditure by preventing the oversizing of redundant battery modules [

98]. By re-conceptualizing miscellaneous electric loads and appliances as active storage resources, and subsequently unlocking their latent regulation potential, it is feasible to significantly attenuate the requisite capacity of dedicated, high-cost storage hardware. This paradigm shift not only optimizes the dwelling’s inherent regulation efficacy but also accelerates the fundamental transition of the residential unit from a passive consumption endpoint into a dynamic, Grid-Flexible Asset [

88].

Direct Current: Hierarchical Power Conversion, Dynamic Adaptation to Volatility

The emergence of Low-Voltage Direct Current (LVDC) distribution architectures in the built environment is driven not only by intrinsic topological advantages but also by convergent structural shifts on both the supply and demand sides of the energy spectrum. On the supply side, the proliferation of distributed generation—predominantly Solar Photovoltaics (PV)—creates a native DC source (

Figure 8). Direct coupling via DC buses circumvents the need for multiple inversion stages, thereby optimizing the integration efficiency of renewable assets [

99]. Concurrently, on the demand side, there is a pervasive transition toward DC-native end-use technologies. Modern high-efficiency building loads, including Light Emitting Diode (LED) illumination, Electronically Commutated (EC) motors for HVAC fans, and Variable Frequency Drive (VFD) centrifugal chillers, inherently operate on internal DC power [

100]. While conventional Alternating Current (AC) networks necessitate multiple, loss-incurring rectification steps (AC-to-DC) to serve these loads, an LVDC architecture eliminates these redundant conversion stages. This results in a streamlined system topology that is thermodynamically superior and better aligned with the trajectory of high-efficiency equipment evolution [

101].

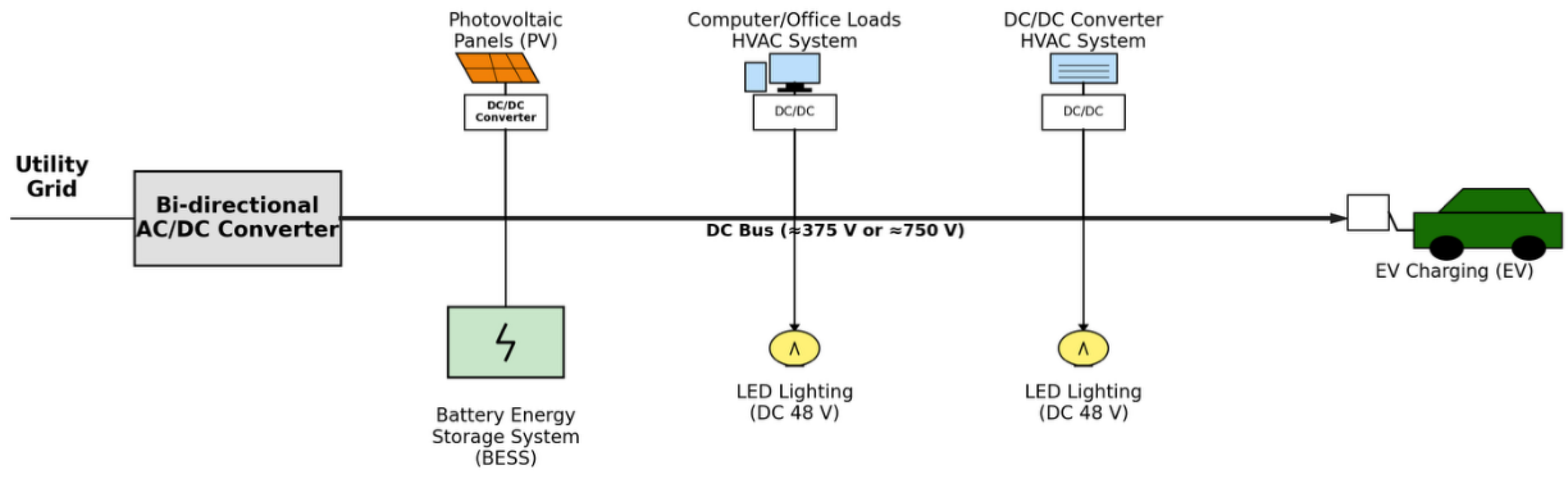

The foundational architecture of Low-Voltage Direct Current (LVDC) distribution relies heavily on the standardization of voltage levels, protection protocols, and component selection. Historically, the lack of a unified consensus on optimal voltage thresholds for building applications has hindered widespread adoption, limiting discourse to theoretical explorations of topology design [

102]. However, recent regulatory frameworks have begun to crystallize these parameters. In the United States, standards such as ANSI/EMerge Alliance and IEEE 2030.10 provide the critical design basis for DC microgrids, advocating for a stratified voltage architecture to balance efficiency with safety [

103]. Contemporary design best practices recommend a three-tier voltage topology: utilizing higher voltages (e.g., 375V or 750V DC) for the primary distribution bus and heavy loads and stepping down to 48V DC for plug loads and LED lighting [

104]. Within the PEDF framework, this stratified approach enables the seamless integration of distributed assets; photovoltaic arrays, energy storage systems, and DC-native loads are coupled to the central DC bus via efficient DC/DC converters. Ultimately, the system interfaces with the external utility grid through a bidirectional AC/DC inverter, ensuring that power conversion is hierarchically optimized to meet the specific voltage requirements of generation, storage, and consumption endpoints [

105].

A defining characteristic of the PEDF distribution architecture is the engineered tolerance for DC bus voltage fluctuations, which functions as a primary control mechanism for system stability. Unlike rigid AC regulation, DC microgrid standards—such as those outlined in IEEE 2030.10—delineate specific operational voltage windows to facilitate decentralized control. Typically, equipment is engineered to maintain full operational fidelity within a nominal band (e.g., 5% to 10%) while retaining survivability and ‘derated’ functionality during wider excursions (e.g., -20% to +7%) [

103]. This voltage elasticity serves a dual function: first, it establishes the physical constraints for component durability; second, and more critically, it enables DC Bus Signaling (DBS). Through strategies such as droop control, the bus voltage level itself acts as a communication signal—indicating surplus or deficit power states—without the need for complex digital communication layers [

106,

107]. Consequently, modern DC-native end-use equipment must be engineered not only for robust voltage ride-through capabilities but also for active responsiveness. Advanced ‘smart’ loads can detect these voltage deviations and autonomously modulate their power consumption, thereby functioning as flexible resources that contribute to the system’s dynamic equilibrium [

105].

To operationalize the PEDF architecture, the entire spectrum of end-use equipment—ranging from miscellaneous plug loads to heavy mechanical systems—must be engineered to accommodate the inherent voltage elasticity of the DC bus. Currently, the market for DC-ready technology is bifurcated by maturity. Low-power applications, such as Light Emitting Diode (LED) illumination and portable consumer electronics, have effectively standardized around DC inputs. Simultaneously, high-load appliances like refrigerators, washing machines, and HVAC compressors are increasingly transitioning toward Brushless Direct Current (BLDC) and Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motors (PMSM) to leverage their superior thermodynamic efficiency and variable-speed control capabilities [

108]. Significant breakthroughs have also been realized in the ‘DC-ification’ of large-scale centrifugal chillers. However, realizing a comprehensive DC building ecosystem requires further technological evolution. Future product development must focus on eliminating redundant rectification stages in native-DC electronics—such as computers, televisions, and mobile devices—by redesigning power adapters to interface directly with the building’s DC distribution network [

109]. Establishing this interoperable hardware ecosystem is a prerequisite for maximizing the systemic efficiency gains of the ‘Solar-Storage-DC-Flexibility’ framework.

Parallel to the optimization of end-use appliances, the large-scale deployment of PEDF architectures necessitates a robust ‘Balance of System’ (BOS) ecosystem, comprising specialized power conversion interfaces (DC/DC and AC/DC converters) and advanced protection hardware (e.g., solid-state DC circuit breakers, residual current detectors, and insulation monitoring devices). Currently, the power electronics landscape is fragmented, characterized by bespoke, application-specific converter designs that impede interoperability and scalability. To resolve this, the industry is transitioning toward a paradigm of ‘Hardware Standardization via Software Diversification.’ By categorizing converter topologies based on fundamental physical attributes—such as power rating, galvanic isolation, and bidirectional flow capability—manufacturers can produce universal, modular hardware units akin to Power Electronics Building Blocks (PEBBs) [

110]. Distinct operational functionalities—whether Maximum Power Point Tracking (MPPT) for PV, charge management for BESS, or voltage regulation for loads—are subsequently implemented via the digital control layer. This architectural shift towards Software-Defined Power Electronics (SDPE) allows for a decoupling of physical topology from application logic, establishing a scalable, universal framework essential for the mass marketization of building DC microgrids [

111].

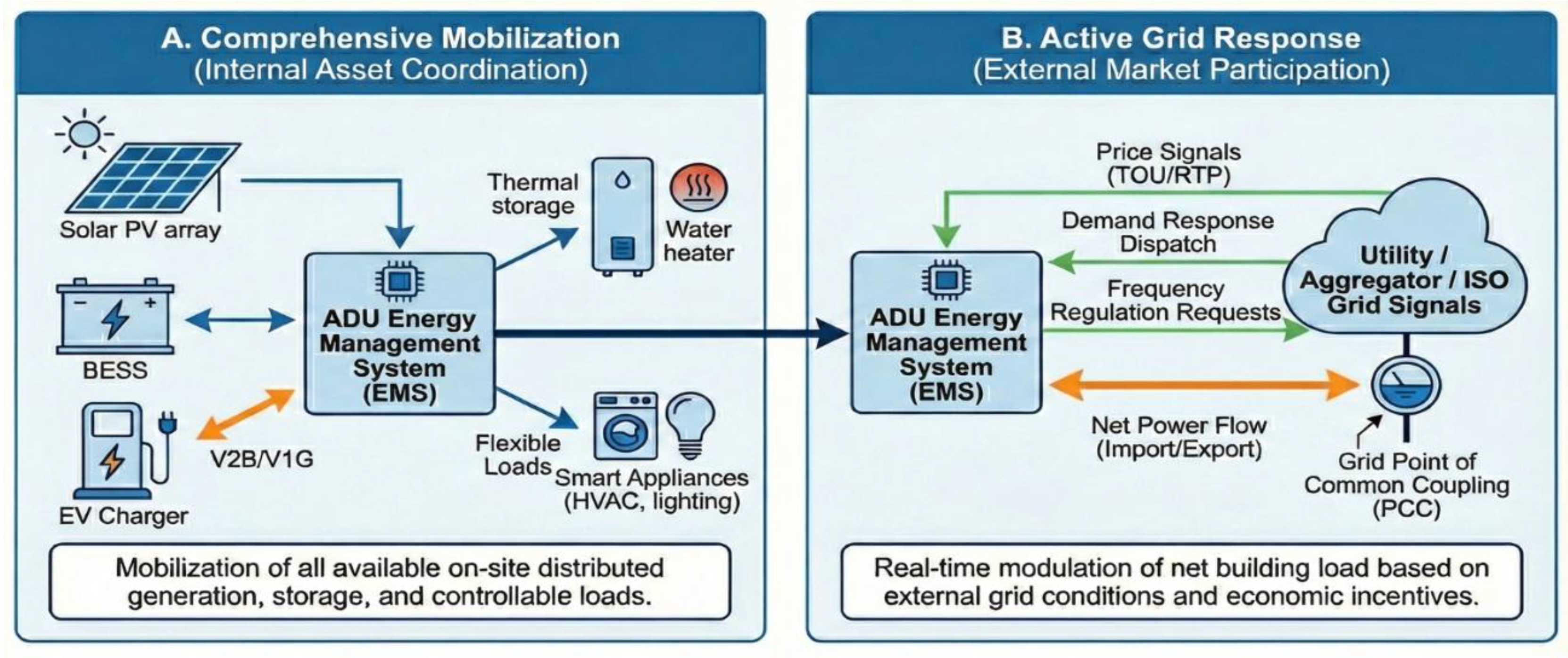

Flexibility: Comprehensive Mobilization, Active Grid Response

The paradigm of Building Energy Flexibility has emerged as a central vector of contemporary energy scholarship. This domain was formally codified by the International Energy Agency (IEA) EBC Annex 67 project (2014–2020), which defined energy flexibility as the capability of a building to modulate its energy demand and generation profile in response to local climate conditions, user needs, and grid requirements [

112]. This adaptability is technically imperative for mitigating the stochastic volatility introduced by high-penetration variable renewable energy (VRE) supply. Consequently, achieving operational flexibility constitutes the terminal objective of the PEDF architecture, which seeks to transmute the residential sector from static, inelastic load endpoints into dynamic, Grid-Interactive Efficient Buildings (GEBs). Realizing this transition requires a bipartite strategy: first, establishing a robust interface with the utility macro-grid to quantify specific regulation necessities (e.g., peak shedding, ramping); and second, deploying advanced internal control strategies to orchestrate distributed assets—ranging from HVAC thermal inertia to electrical storage—thereby executing precise load modulation in alignment with utility dispatch signals [

97,

113].

Analyzing current evolutionary trajectories, the future power infrastructure is transitioning toward a decarbonized paradigm anchored predominantly by Variable Renewable Energy (VRE) sources, with dispatchable resources serving complementary regulation roles. Realizing this vision necessitates a synchronized orchestration of generation, storage, distribution networks, and end-use loads—a framework often referred to as Integrated Grid Planning [

114] (

Figure 9). Given the inherent stochasticity and intermittency of wind and solar generation, the supply side faces acute stability challenges that demand effective mitigation strategies. Crucially, if the demand side—specifically the building sector—can transition to an adaptive consumption model that mirrors these supply-side fluctuations, it effectively alleviates the capital-intensive requirement for utility-scale storage and regulation reserves. This dynamic establishes the fundamental significance of Grid-Interactive Efficient Buildings (GEBs), positioning them as essential flexible loads that provide ‘non-wires alternatives’ within the architecture of the future low-carbon electric grid [

88,

115] (

Figure 9).

From the perspective of the utility grid or Independent System Operator (ISO), building energy flexibility theoretically constitutes a valuable dispatchable resource. However, the limited capacity and granularity of individual structures typically preclude their direct participation in wholesale electricity markets or system-level frequency regulation. Consequently, practical implementation necessitates the aggregation of multiple end-users into a unified ‘Load Aggregator’ to achieve the minimum capacity thresholds requisite for market entry (

Figure 9 (b)). This structural necessity elevates the operational architecture of the Aggregator-Grid interface to a critical research priority [

116]. In the envisioned interactive paradigm, the ISO broadcasts dispatch signals to the aggregator, which functions as a hierarchical mediator (

Figure 9(b)). The aggregator is responsible for decomposing the aggregate Demand Response (DR) target into granular sub-instructions, which are then disseminated to individual buildings for local control execution [

97]. Optimally, these aggregators comprise a heterogeneous portfolio of building typologies with varying functional constraints and thermal inertias. This diversity enables the stochastic optimization of response baselines, allowing the aggregator to mitigate the risk of non-compliance by individual nodes. It is only through this collective architecture that the built environment can function as a bona fide flexible asset, effectively operating as a Virtual Power Plant (VPP) capable of competing with traditional generation resources in the dispatch network [

117] (

Figure 9).

In the context of Time-of-Use (TOU) tariff structures, the PEDF system functions as an automated economic optimization engine, executing ‘peak shaving’ and ‘valley filling’ strategies to reshape the building’s power demand curve (P*) and minimize operational expenditures [

118]. Beyond individual cost minimization, the PEDF architecture serves as a foundational node within a Virtual Power Plant (VPP) network, executing real-time control logic in response to aggregated dispatch setpoints (P*) broadcast by the utility or Independent System Operator (ISO). The magnitude of this regulation potential is best illustrated by the integration of electric mobility assets: a standard 10,000 m

2 commercial facility hosting a fleet of 100 Electric Vehicles (EVs) can theoretically provide 0 to 2 MW of bidirectional regulation capacity via Vehicle-to-Grid (V2G) and Vehicle-to-Building (V2B) interfaces (

Figure 9(a)). Notably, this capacity exists independently of additional contributions from onsite photovoltaics or passive building thermal mass, highlighting the immense latent flexibility of the electrified built environment [

95,

119].

The economic viability of the PEDF architecture is fundamentally predicated on Transactive Energy participation—specifically, the monetization of grid-interactive services through bidirectional interoperability. By modulating internal demand profiles to provide demand-side regulation, buildings can accrue significant revenue streams, effectively transforming from cost centers into profit-generating assets [

120]. However, realizing this value proposition necessitates a regulatory paradigm shift wherein Independent System Operators (ISOs) and Regional Transmission Organizations (RTOs) formally recognize building aggregations as dispatchable resources comparable to traditional generation. This transition is currently being accelerated by federal mandates such as FERC Order 2222, which requires ISOs to remove barriers for Distributed Energy Resource (DER) aggregators to compete in wholesale markets [

121]. At the state level, jurisdictions like California have operationalized these concepts through high-value compensation mechanisms. For instance, the Emergency Load Reduction Program (ELRP) in California explicitly compensates non-utility educational and commercial aggregators for voluntary load shedding during grid emergencies, offering a clearing price of

$2,000/MWh (approx.

$2/kWh) for peak-shaving events—a valuation that significantly incentivizes the deployment of flexible, storage-integrated building systems [

122].

To achieve genuine flexible Grid-Interactivity, the PEDF architecture must possess the autonomous capability to modulate its operation in response to dynamic dispatch setpoints (P*) broadcast by the utility or aggregator. The efficacy of this response relies heavily on robust Hierarchical Control Strategies that can orchestrate the diverse flexibility assets within the building—ranging from EV chargers to variable-speed HVAC drives—each of which possesses distinct ramping constraints and regulation capacities [

123]. Unlike traditional centralized building management systems (BMS) that rely on complex, single-point communication links, the PEDF system utilizes DC Bus Signaling (DBS) as the primary control logic. In this decentralized paradigm, the DC bus voltage itself acts as a universal state-of-charge indicator: voltage deviations function as real-time pricing signals, triggering autonomous response from connected loads and storage assets based on pre-programmed Droop Control characteristics [

105]. This architecture allows critical loads to be prioritized while deferrable loads automatically curtail during ‘low-voltage’ (supply-constrained) events, significantly reducing system complexity and enhancing the resilience of the local microgrid without reliance on continuous external communication [

107].

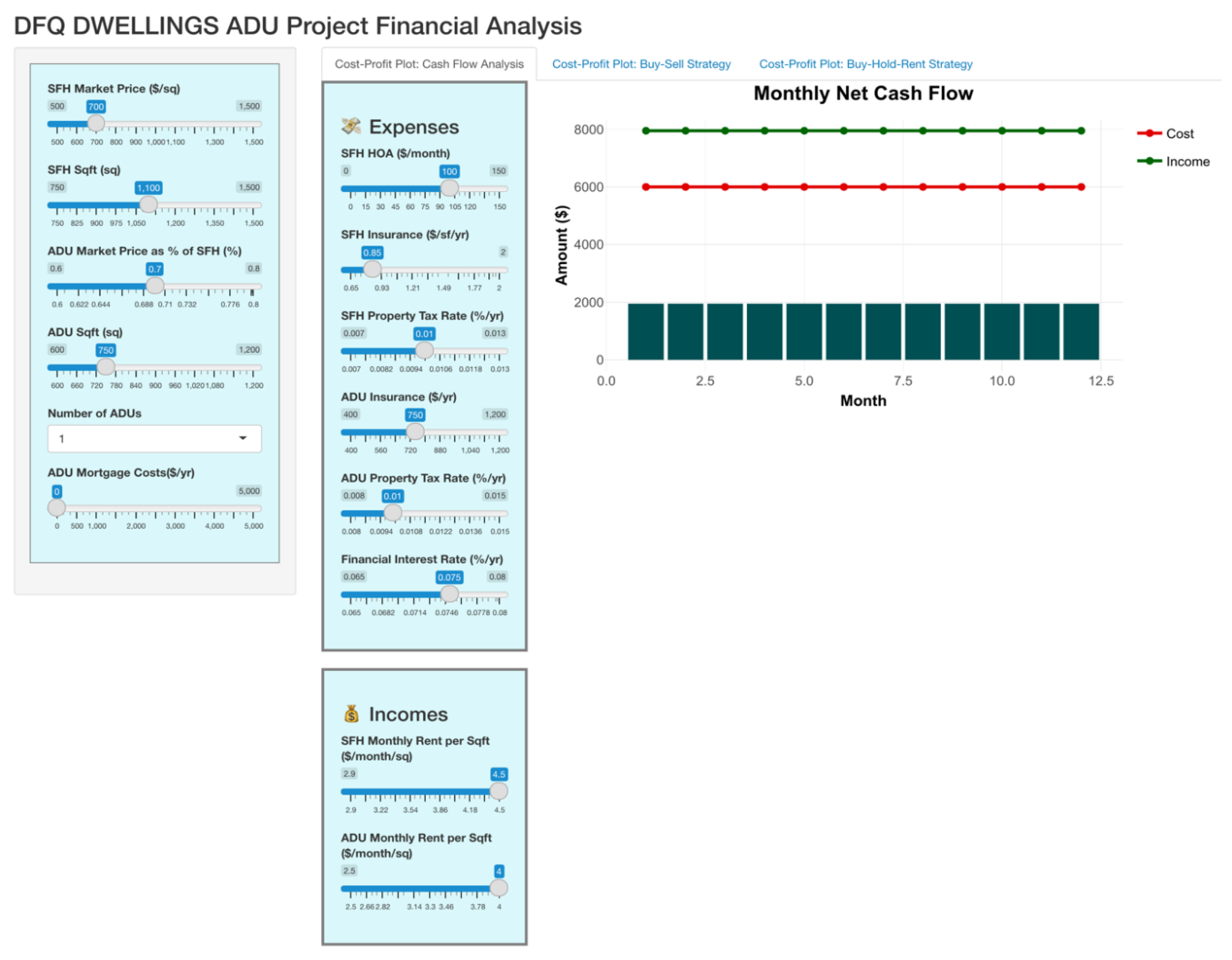

7. Economic Feasibility and Incentives

The economic viability of ADU deployment in California is fundamentally predicated on the elimination of land acquisition costs, allowing homeowners to leverage existing equity to achieve superior returns on investment (ROI) and a significantly lower Levelized Cost of Housing (LCOH). Research by the Terner Center for Housing Innovation indicates that despite construction costs averaging

$300–

$400 per square foot, the generated Net Operating Income (NOI) in high-demand coastal regions yields capitalization rates that frequently exceed 6–8%, far outperforming standard single-family rental yields [

124]. This intrinsic structural advantage is further catalyzed by a multi-layered state incentive framework designed to minimize “soft costs” and barriers to entry; specifically, the CalHFA ADU Grant Program has provided up to

$40,000 in pre-development subsidies to support architectural and permitting phases [

125], while legislative reform via SB 13 (2019) prohibited impact fees on units smaller than 750 square feet, reducing development costs by an estimated

$10,000 to

$20,000 per project [

126]. Next, studies also found that the incorporation of residential BESS is essential for improving the efficiency of residential solar energy usage and further improve the energy efficiencies of the dwelling units [

127]. Furthermore, long-term operational affordability is preserved under Proposition 13, which utilizes a “blended value” assessment strategy that adds only the value of the new improvement rather than triggering a prohibitive full property reassessment [

128]. Finally, access to capital has been significantly expanded through lending modernization by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, which now allow borrowers to count 75% of projected rental income from the ADU toward qualifying income ratios, thereby democratizing access to this housing typology for middle-income households [

129].

Beyond regulatory and energy-related advantages, significant returns on investment (ROI) are realized through the strategic application of prefabrication technology (also known as off-site or modular construction/manufacturing). This methodology shifts most in-situ processes—traditionally subject to weather delays and site constraints—into a controlled manufacturing environment. The comparative advantages over conventional “stick-built” construction are quantifiable and substantial. On the one hand, modular construction can compress project schedules by 30% to 50% by allowing site preparation (grading, foundation) and vertical construction to proceed concurrently rather than sequentially, thereby accelerating the time-to-market and reducing carrying costs for investors [

130,

131]. On the other hand, the precision of factory-based manufacturing significantly reduces material waste. Studies indicate that modular methods can reduce overall construction waste by approximately 80% compared to traditional on-site methods, primarily by optimizing material cuts and recycling off cuts [

132]. More importantly, lifecycle assessments (LCA) demonstrate that prefabricated housing generates 30% to 47% fewer greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions during the construction phase [

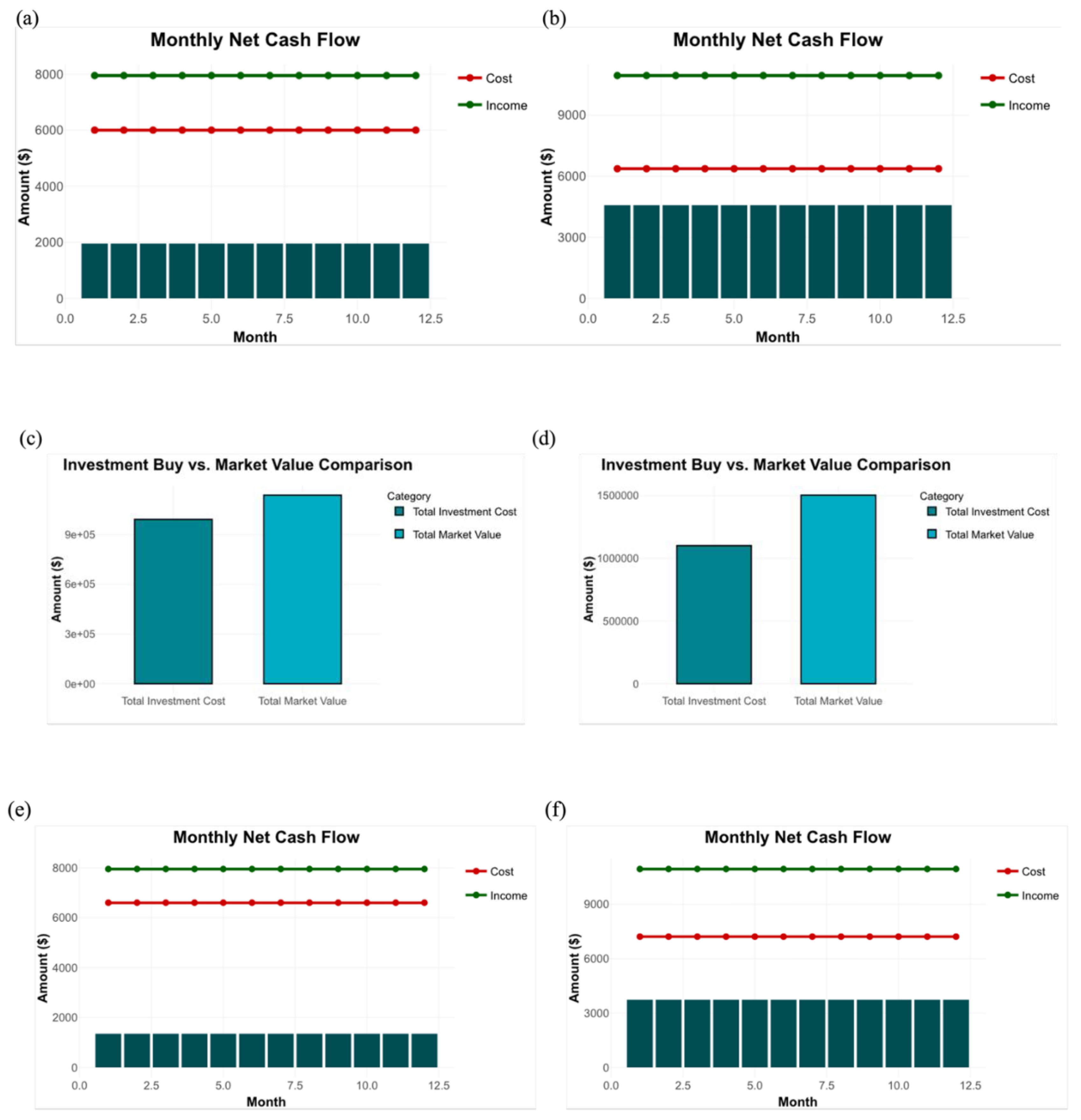

133]. This reduction is attributed to fewer vehicle trips to the site, reduced on-site heavy machinery usage, and tighter building envelopes that lower long-term operational energy demand.