1. Introduction

Digital product passports (DPP) specify information about a product and its lifecycle, including component suppliers, manufacturer, validity period, information that enables its circularity, and sustainability-related information [

1]. Sustainability claims in DPP are data claims that specify certain regulatory and quality properties in a product. Such claims may outline specific material composition in a product, carbon footprints, recycled material content, etc. Sustainability claims, especially in consumer products, are becoming a regulatory necessity, particularly with the European Union’s upcoming DPP requirements and Green Claims Directive [

2,

3]. Companies must disclose data such as carbon footprint, recycled content, material compositions, and sourcing practices to comply with these rules. In addition, sustainability claims also specify product quality attributes that help build consumer trust in a product [

4]. For instance, eco-conscious consumers are more likely to purchase an organic product over a non-organic one of similar quality. They will also choose products with lower carbon footprints and more recycled content over similar products without these properties, as the former adopts environmental conservation practices during its production.

However, current practices face two major challenges. First, consumers and regulators struggle to verify sustainability claims, which can lead to greenwashing and erode confidence in environmental information [

5]. Second, companies are reluctant to disclose detailed product and supply chain data due to concerns over intellectual property, trade secrets, and competitive advantage. This tension between transparency and confidentiality creates a pressing need for a system that ensures verifiable, trustworthy sustainability claims while safeguarding sensitive business information.

Privacy-aware computation provided in ZKP systems provides the possibility for verifying sustainability claims in products without revealing sensitive business information. ZKPs are a cryptographic protocol that enables a prover to prove the correctness of a statement without revealing sensitive information about the statement [

6]. Using selective disclosure mechanisms within ZKPs, companies can prove statements such as “this product contains at least 30% recycled material” or “its carbon footprint is below a regulatory threshold” without revealing confidential raw data. Stakeholders, such as manufacturers, auditors, regulators, and consumers, will benefit from trusted, machine-verifiable sustainability information tailored to their needs. The value proposition lies in enabling compliance with emerging regulations, protecting intellectual property, preventing greenwashing, and enhancing consumer trust in sustainable products.

The objective of this paper is to formally describe sustainability claims in consumer products and provide a ZKP-based system for verifying sustainability claims while protecting sensitive information about the claim. The rest of this paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 provides background and related literature review.

Section 3 provides a formal description of various sustainability claims.

Section 4 describes the data types and the trust model scenarios for the input data used in proof generation.

Section 5 outlines the interaction sequences for the relevant stakeholders and entities for the proof generation and verification lifecycle.

Section 6 shows the necessary algorithms for the implementation of the ZKP system for sustainability claim verifications.

Section 7 provides the discussions resulting from this work.

Section 8 provides the conclusion of this work, limitations, and future works.

2. Background and Related Works

2.1. Technical Concepts

Blockchain: this is a p2p network of nodes that executes and stores transactions in an immutable ledger using cryptography to ensure that data stored in the network cannot be modified, and with formal consensus mechanisms specifies conditions for adding new data to the network [

7].

Smart contracts: these are self-executable computer programs running on various blockchain networks and do not require any centralized entity to enforce business conditions defined in them. Solidity is the common programming language for writing smart contracts [

8].

zk-SNARK: this is a cryptographic framework for developing general ZKP systems covering different problem types. Due to their non-interactive verification process and fixed proof size, they are commonly used in decentralized applications. Logic conditions and signals that satisfy these conditions are represented as formal circuits in zk-SNARKs [

9].

Circom: this is a high-level human-readable language for realizing zk-SNARKs circuits. Several open-source libraries and IDEs, like the REMIX tool, can be used to implement Circom codes and generate proofs. These open source tools can also be used to generate the verifier scripts for zk-SNARK circuits. These verification scripts can be realized as Solidity code for smart contracts [

10].

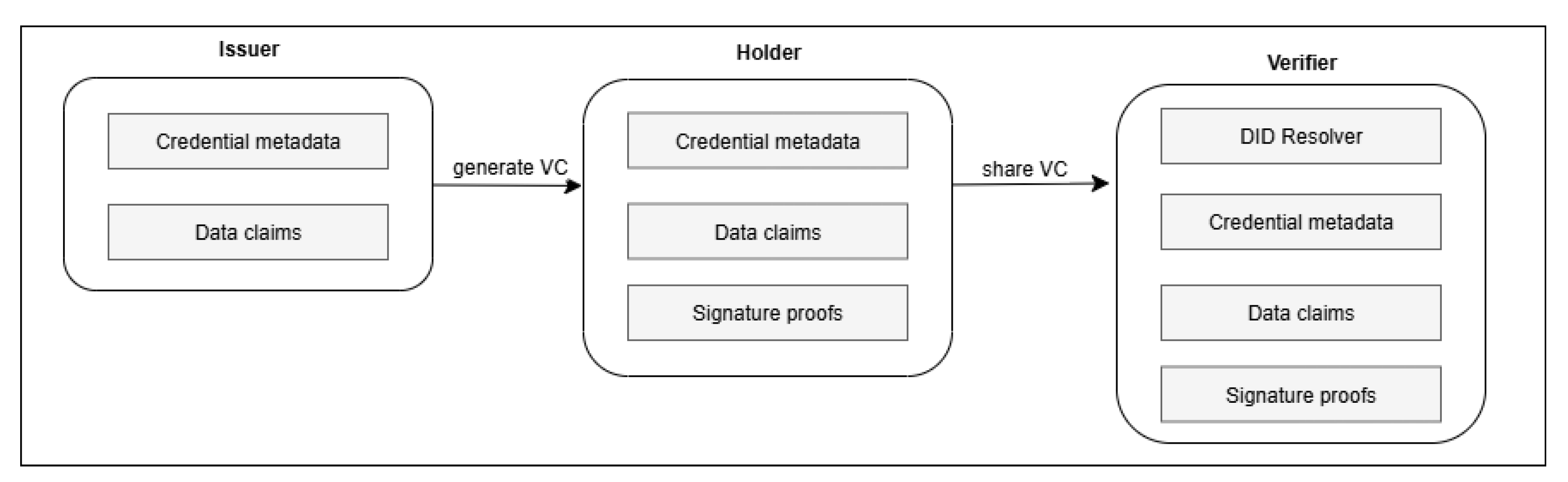

Verifiable Credential: VCs contain a collection of data claims and digital signatures that validate the claims. The credential is issued by an issuer (who signs the claims) to the holder (who makes the claims). In a VC structure, usually specified as JSON, the upper layer outlines the information subject of the claim and the issuer of the signature. The middle layer contains a list of claims. The bottom layer contains the digital signatures signed by the issuer on each of the claims [

11].

Decentralized ID: this is a unique identifier that addresses the entities in a verifiable credential, such as the issuer, holder, and data subjects. To verify the data claims in a VC, a verifier uses a DID resolver, which is software that retrieves public keys associated with a DID to verify the digital signatures in a credential [

12].

2.2. Related Works

2.2.1. DPP Architecture and Product Sustainability Information

To describe the architecture of DPP, we use a metamodel derived from the conceptual definition of DPP components following the CIRPASS initiative and GS1 standards. Both CIRPASS and GS1 are two successful EU-wide projects that seek to provide frameworks and standards for describing and implementing DPP for different industry sectors and use cases [

13]. According to CIRPASS, a DPP is simply defined as a structured collection of product-related data focused on sustainability and circularity [

14]. The GS1 describes DPP as a unique representation of a product/ product information, composed of multiple component entities representing sub-parts or materials of the product. Each product and Component can carry associated sustainability objects that capture specific environmental or social metrics [

13]. Some of the sustainability information represented in DPP includes carbon footprint values, percentage of recycled material content, material composition details, or ethical raw material sourcing certifications, which are contextualized by a relevant lifecycle stage of the product (such as manufacturing, use, or end-of-life phase). The sustainability information specified in DPP may also include digital attestation (credentials).

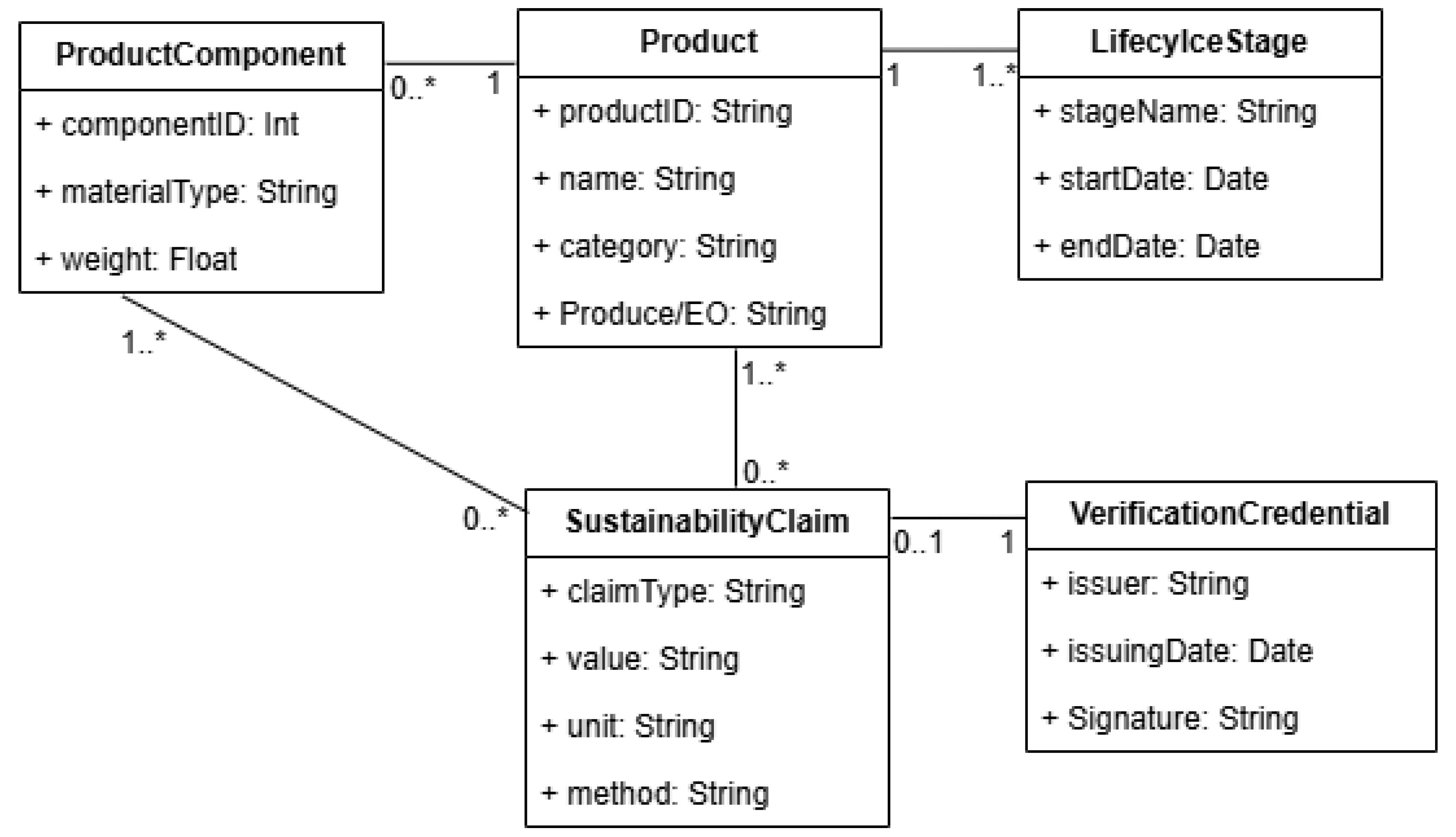

Figure 1 shows a metamodel schema that provides a structured representation of a DPP that applies to real-world DPP implementations across multiple industries, enabling interoperability and trustworthy disclosure of sustainability claims.

Figure 1 outlines the UML class diagram of a DPP metamodel, showing the key classes such as the

Product,

Component,

LifecycleStage,

SustainabilityClaim, and

VerificationCredential with their attributes. A product is composed of zero or more components, and each component is part of a product. In that case, a component of a product can also be an independent product. A product can have multiple lifecycle stages, each representing a phase (e.g., manufacturing, usage, end-of-life) with start and end dates. Each lifecycle stage is associated with at least one product. Each instance of a sustainability claim can be linked to either a product or a component. Hence, a product or component may have many sustainability claims. A sustainability claim may have a digital credential for its attestation with a verification method. The goal of the current paper is to describe a privacy-preserving method for verifying sustainability claims in DPPs using ZKPs.

2.2.2. ZKPs in Supply Chain Verifications

There is an increasing research in applying ZKPs for verifications in supply chain and production processes [

15]. These works have integrated ZKPs in supply chains for product authenticity verifications [

16], product integrity and counterfeit checks [

17,

18], supply chain data privacy in public blockchains [

19,

20]. Still, the research on applying ZKPs in verifying sustainability claims in the supply chain of consumer products is still in the early phase. The work [

21] applied chain of custody models in DPPs for tracking and validating sustainability attributes of products throughout supply chains. The research [

22] applied range proofs in ZKPs to provide origin information for a supply chain product without revealing its exact location. Proof of product origins is essential for providing compliance and ethical raw material sourcing. Similarly, the research applied ZKPs to validate adherence to sustainability standards, origin, and handling procedures without revealing sensitive supply chain data [

23]. Lastly, the research works applied ZKPs for proving carbon emissions claims in production and green product labeling [

24,

25]. Our work follows a generalized framework for sustainability claims verification by first formally describing different sustainability claims and describing various trust models for verifying these claims based on different public and private data inputs in the claim generation. Although the field of sustainability verification research is still evolving, and there is no defined list of sustainability claims, our work provides an extendable approach for verifying different types of sustainability claims information in DPPs.

3. Formalization of Sustainability Claims in DPP

3.1. Product Carbon Footprint

The carbon footprint of a product is derived from the sum of the emission indexes of activities during its production, divided by the total units produced [

26]. Activities may include inbound and outbound logistics, energy consumption, etc. Different product groups have a well-established list of activities used in estimating their carbon footprints. Each activity type has an emission index associated with it. Different means of moving products (air, sea, land, rail, etc.) have different emission indices, and the emission index in production energy consumption for renewable energy is expected to be lower than that of fossil fuels when used in production factories. Formulating a specific carbon footprint formula is beyond the scope of this paper.

where:

is the quantity of activity i

is the activity type i

is the emission index of activity i

is the total product units produced

is the carbon footprint for the product x

is the maximum allowed carbon footprint for the product x

Equations (

1) and (

2) show a generalized formulation of carbon footprints for a range of activity types

, for a total amount of product units

, such that each unit has a carbon footprint

. For Equation (

2), the carbon footprint value is expected to always be lower than or equal to a specified maximum carbon footprint value. These equations, when realized in a zk-SNARKs circuit, allow specific activities (and other variables in the formula) that are not to be disclosed to the public cab be hidden in the circuit. A proof can be generated that the computation of the carbon footprint calculation results in a given value

. Specifically for Equation (

2), the output of the equation can also be hidden, especially when doing so can result in a competitive advantage. Hence, a manufacturer can also prove that the carbon footprint of its product is less than a given amount of maximum allowed carbon footprint (

) without revealing the actual footprint. Such high boundaries of carbon footprint are usually specified by regulators for compliance purposes.

3.2. Product Material Composition

The percentage of the material composition is the ratio of specific material to all other materials used in production. In the textile industry, the material composition of a product could include different percentage representations of materials such as cotton, wool, polyester, etc. The zk-SNARK provides the possibility to represent the material composition formula as a circuit and generate proofs for the material composition percentages, such that IP-protected materials and their compositions can be hidden in the circuit.

where:

Equation (

3) shows the material composition of a given input raw material

in comparison to all the raw materials

used in the production of a product. The raw materials composition in a product is a function of their weights in the product. Proofs of a percentage representation of materials

can be generated for specific materials, while the sensitive materials are hidden in the circuit.

3.3. Recycled Material Composition

Verification of recycled material composition shares a similar formula with material composition, such that the percentage of recycled material composition is the ratio of recycled materials to all materials used in production. Also, the actual amount of Recycled material and other IP-protected materials and their compositions can be hidden in the circuit. With zk-SNARK representation of the formula in a circuit, the proof of the composition of recycled material (ratio), not the actual amount, can be generated.

where:

is the weight of the recycled materials used in the production

is the total weight of all materials used in the production of x

is the percentage of recycled material composition of the product x

is the percentage of the minimum amount of recycled material composition required in a product x

Equation (

4) shows the material composition for a recycled material

in comparison to the total raw material

used in production. The composition is represented as the weights of each material. In a case of special regulatory requirements, where a specified amount of recycled material is expected to be reused in a product, a manufacturer can provide proof that the recycled material content is greater than or equal to the minimum required recycled content composition

as shown in Equation (

5).

Recycled material in Equation (

5) is a positive product property, unlike Equation (

2) where carbon footprint is a negative product property. The higher the carbon footprint, the lower the quality of a product is, while the higher the recycled material, the higher the quality of the product is considered in terms of its sustainability properties. Hence, less than and greater than are used to express these attributes in Equations (

2) and (

5), respectively.

3.4. Other Sustainability Claims

Beyond the previously formalized sustainability claims, there are several other sustainability claims for regulatory compliance or to outline product quality, such as Ethical raw material sourcing, raw materials sources, suppliers, etc. A manufacturer can provide proof that materials used in the production of a product are ethically sourced or are within a specified location. Manufacturers can also provide proof that their suppliers are within a specified list of approved suppliers. These proofs can be provided without revealing the exact sourcing locations or revealing their product suppliers. Still, formalizing and implementing zk-SNARK circuits for these types of claims is beyond the scope of the current paper.

4. Sustainability Claims Data Matrix and Trust Model

4.1. Input and Output Data Sources

Outlining the sources of data used in the generation (and verification of proofs) for sustainability claim validation is necessary to understand the trust model necessary for the proof lifecycle. Equations (

1) to (

5) all have input data on the left side and output data on the right side. The trustability of generated proofs in sustainability claims verification is dependent on the source of data. The output data is not problematic since it is either provided by the circuit or by an external entity like a regulator. However, for the input data, which are mostly provided by the manufacturer, different types of trust models are needed to analyze the trustability of the proofs.

Table 1 shows data objects associated with different sustainability claim types. The table shows that input data for proof generation are mostly produced by economic operators such as product manufacturers and external data sources like regulatory databases. The output is produced mostly from the circuit or from regulatory databases when they are comparative outputs, like the maximum allowed carbon footprint or the minimum required recycled material in a product.

4.2. ZKP Input Data Validation Trust Model

Different trust levels are connected to different scenarios of input data validation for proof generation.

4.2.1. Economic Operator (EO) Validates its Input Data

This is the minimum trust level where an economic operator, like a product manufacturer, provides input data for proof generation and validates the input data by issuing a credential certifying the data’s correctness. Since a sustainability claim is made by the same entity that certifies the input data, there is a potential risk that this economic operator can manipulate the data such that the proof generated is always valid for the claim made. This is particularly relevant for the carbon footprint claim, as shown in Equation (

1), the input data for this claim are internal production activities of the manufacturer.

4.2.2. EO Input Data Validated by Another EO

In this scenario, an economic operator that makes a claim provides the input data for the claim proof generation; however, another economic operator provides a credential that certifies the input data. In this setup, trust is distributed across multiple organizations for input data, and the risk of data manipulation by the economic operator that makes the claim is reduced. This scenario is relevant for a claim about material composition. As shown in Equation (

3), the input data for this claim verification are raw materials used in the actual production of the product. Hence, suppliers of raw materials can each provide credentials that validate the quantity supplied to the manufacturer.

4.2.3. EO iNput Data Validated by an Auditor

Another level of trust in proof generation for sustainability claims is the use of external auditors to verify and issue data credentials for the input data. In this setup, an economic operator that wishes to generate a proof about a sustainability claim will first obtain a credential from an external auditor that validates the input data. If an external auditor certifies the data, then proof can be generated for the claim made by the economic operator. In some designs of the DPP, auditors can have access to an external backup of data associated with a product. This can provide the auditor with an alternative data source to verify the correctness of the data provided by the economic operator. Besides that, auditors also have access to internal processes in production facilities; hence, they can validate the correctness of data provided by the economic operator. This level of distribution of trust between the economic operator and the auditor reduces the risk of input data manipulation, ensuring that the proof generated represents the correct situation in the production process.

4.2.4. EO Input dAta Validated by Blockchain-Enabled Merkle Tree

In this setup, a Merkle Tree is first used to aggregate all the data associated with a particular product of a DPP, and the root hash is stored on the blockchain. This prevents the product manufacturer from manipulating or changing the input data for the proof generation. Hence, a manufacturer provides the input dataset along with their Merkle proof to a verification service provider. This service provider verifies the input data by checking the Merkle tree such that the data provided along with the Merkle proofs matches the Merkle root stored on the blockchain. If the data supplied is correct, the service provider then generates the proof of the claim. In this setup, trust is distributed across the economic operator that provides the input data, the blockchain that stores the Merkle root, and a third-party verifier that checks the Merkle tree to verify the correctness of the input data.

5. ZKP Interaction Sequences

5.1. Auditor Issued Credentials for Input Data Validation

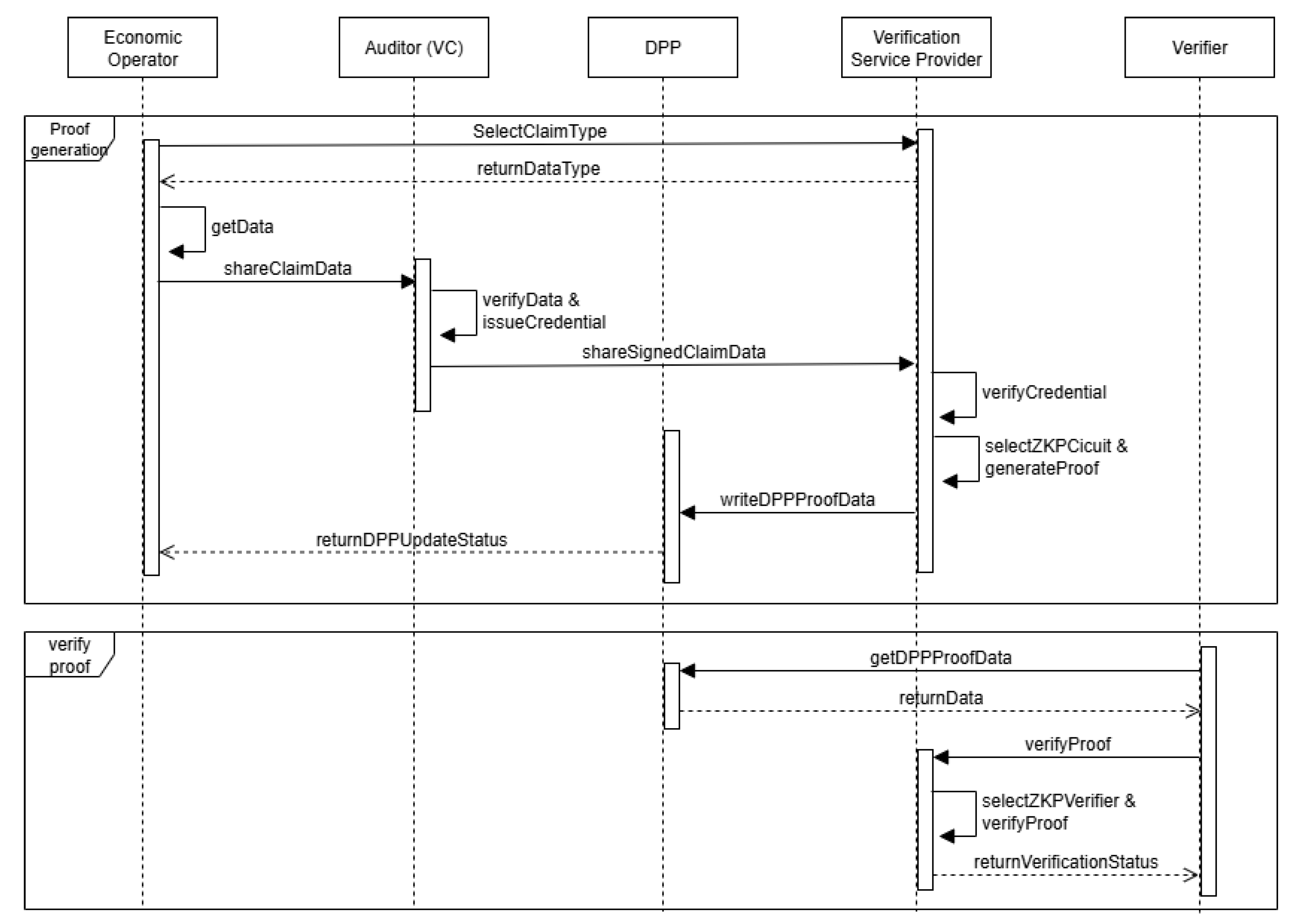

The ZKP lifecycle is largely divided into proof generation and proof verification processes.

Figure 2 shows the sequences of activities in proof generation, where an external auditor issues credentials for input data for proof generation.

The sequence of activities starts with an Economic Operator selecting a

claim type it wants to generate proof for. As already shown in Equations (

1) to (

5), each claim type has different formal representations, hence a different circuit for each sustainability claim. The Verification Service Provider publicly hosts the zk-SNARK circuits files for different types of claims. To increase trustability, a hash of the circuit file can also be stored on the blockchain or copies of the circuit stored in manipulation-resistant databases like IPFS. The verification service provider returns the needed

data type for the requested claim. The economic operator gets the data and shares the

claim data with an external auditor to issue credentials for the datasets provided. The auditor internally verifies the data, issues a credential for the input data for proof generation, and shares the

credential-backed claim data with the verification service provider for proof generation. The verification service provider verifies the credential validity, selects the correct zk-circuit for the claim, and generates a proof of the sustainability claim. The generated proof and the public data associated with the proof are directly written into the DPP of the particular product the claim is made.

To verify the claim, a customer who wishes to purchase the product or another economic operator can read the proof data from the DPP, select a suitable verifier for the claim. The verifiers for specific circuits are hosted by the Verification Service provider. Also, other economic operators can independently host and run the verifier for different proof circuits that have been established within the DPP system. The verifier checks the proof and the public statements to verify that they certify the conditions of the circuit on which the proof is based. The status of the verification is returned to the verifier.

5.2. Blockchain-Stored Merkle Root for Input Data Validation

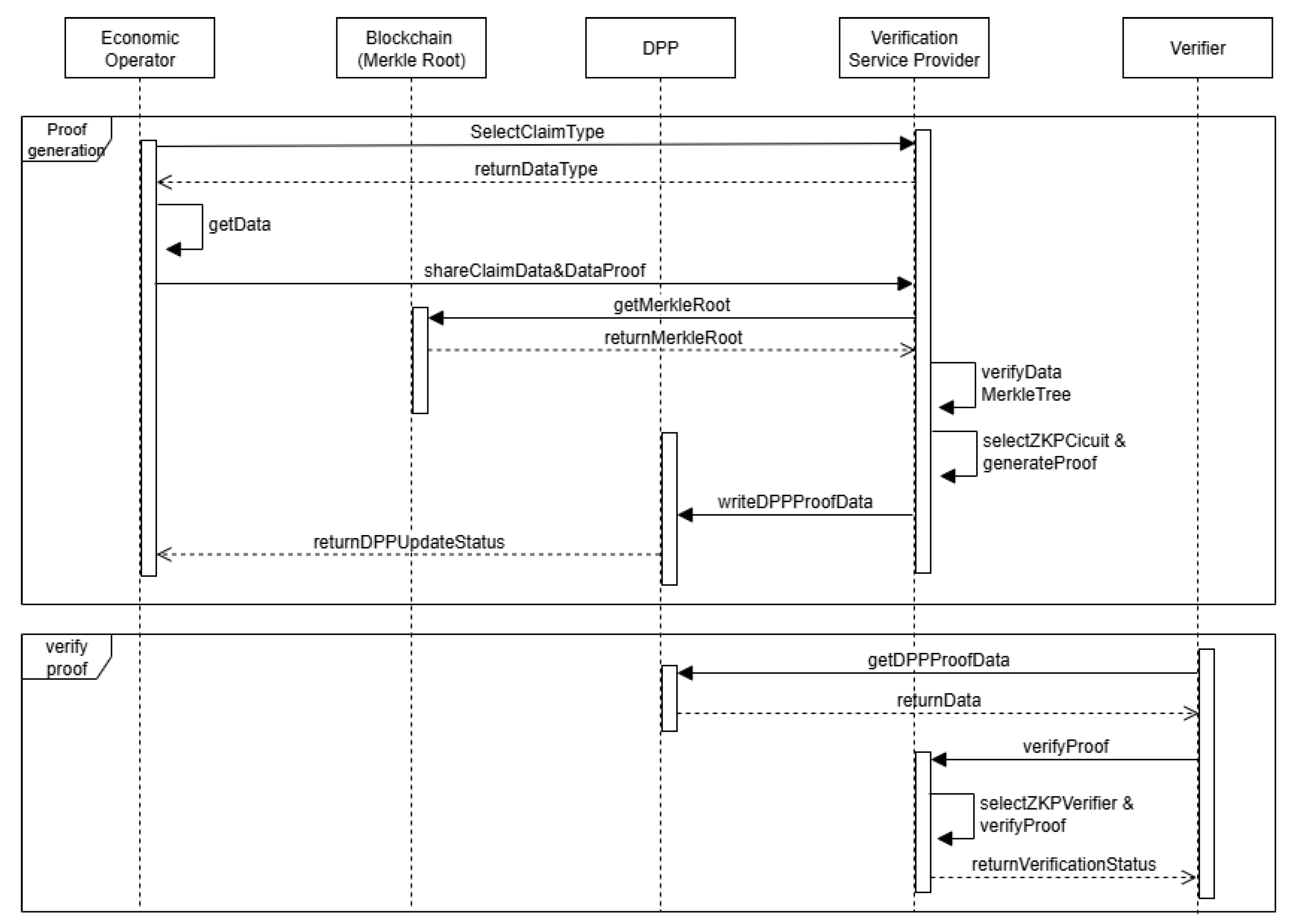

All previous interaction sequences, except those related to input data validation for proof generation. In this case, the economic operator obtains all the necessary input data for the selected claim type and then shares the data, along with the Merkle Proof of the input data’s correctness, directly with the verification service provider. The verification service provider rebuilds the Merkle tree with the data provided by the economic operator and checks that the Merkle root matches the manipulation-resistant Merkle root previously stored on the blockchain.

Figure 3.

ZKP Interaction Sequence with Smart Contract.

Figure 3.

ZKP Interaction Sequence with Smart Contract.

6. ZKP Extensions Implementing Concepts

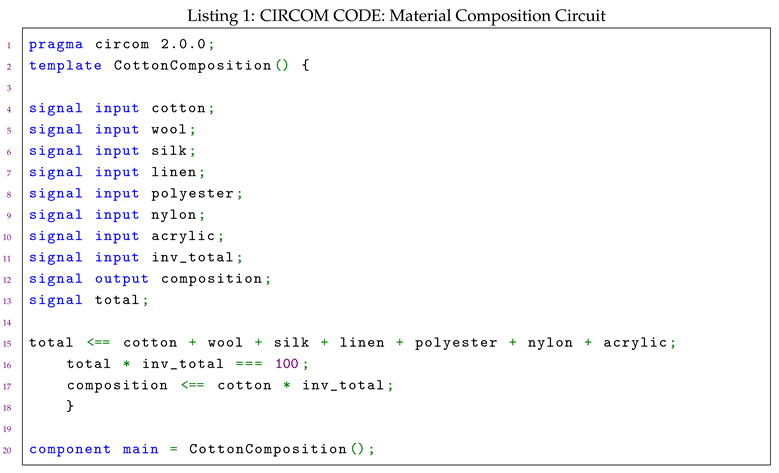

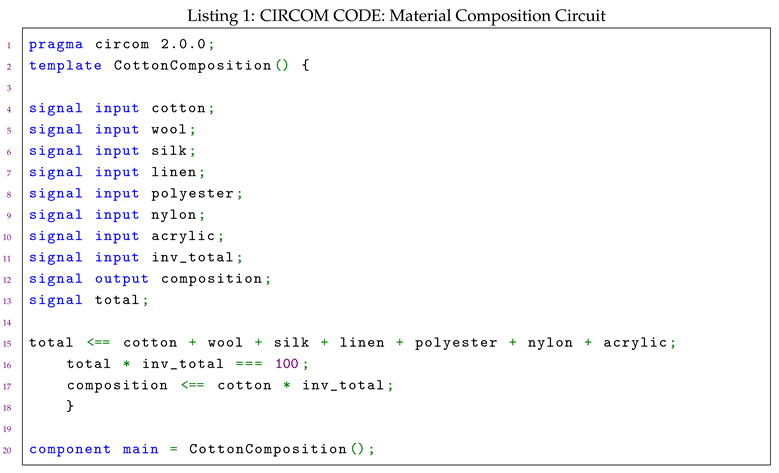

6.1. ZKP Circuit for Sustainability Claims

For sustainability claims in Equations (

1) to (

5), a separate zk-SNARK circuit has to be prepared for each of them to outline the signal conditions that satisfy the equation. In outlining the implementation concepts, this paper focuses on Equation (

3) to show the input signals, output signals, and mathematical conditions for realizing the equation in a circuit in a textile material production scenario.

The material composition Circuits represents the ratio of a particular material and the summation of the list of all materials used in textile production. Each material input is provided in weight, and zero input is provided when a material in the list is not used in the textile product. Using a list of all possible materials protects the circuit’s signals from linking to a specific manufacturer’s input materials list. Since direct divisions are not easily implemented in zk-SNARK circuits, the inverse of the total materials’ weight is also provided. The input total inverse is validated with a condition in the circuit that checks that the multiplication of the inverse total supplied and the total produced in the circuit results in 1. The zk-SNARK circuits are designed for integer calculations; hence, the decimal number produced by the inverse total is scaled using a factor that ensures the number becomes an integer. The input inverse total validation becomes . The rest of the calculation follows basic arithmetic operations. The composition percentage, which is the output of the circuit, is the multiplication of the specific product weight and the validated inverse of the total weight. These are shown in the Circom code below. If the circuit is instantiated with the following input data cotton:3, wool:2, silk:5, linen:0, polyester:10, nylon:0, acrylic:0, and inv_total:5, a proof of material composition 15% is generated for Cotton. This proof can be verified without revealing the weight of cotton and other materials used.

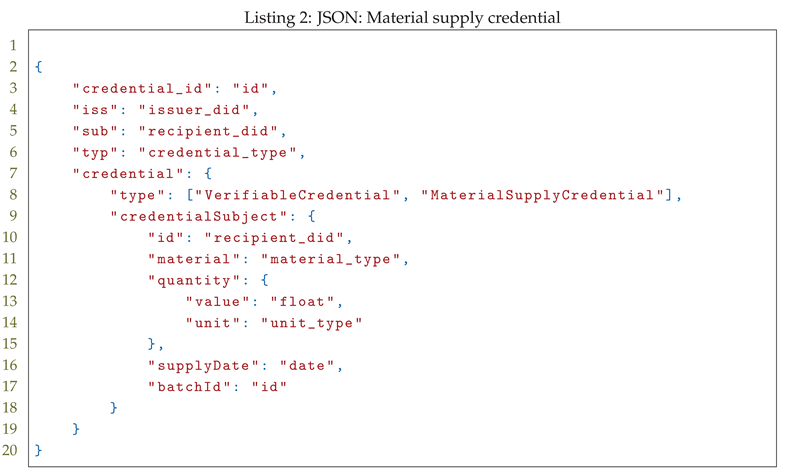

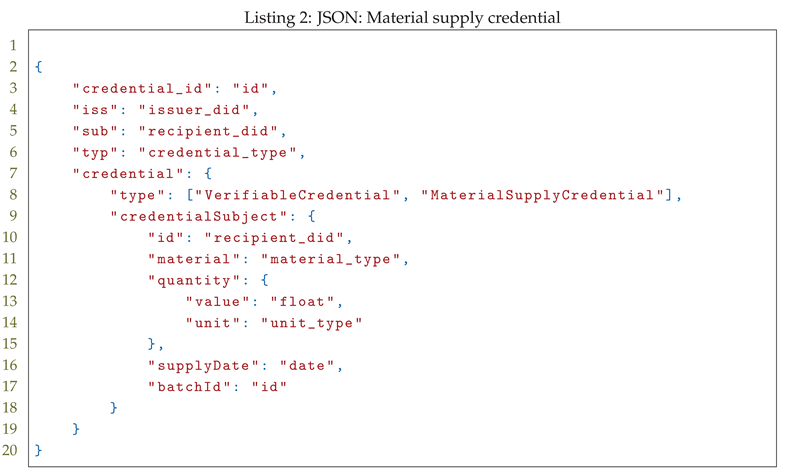

6.2. Verifiable Credential for ZKP Input Data Validation

The input data for proof generation can be verified by another party that issues a data credential to the party that makes the sustainability claim. The credential issuer can be a trusted entity (e.g., an auditor), another economic operator (e.g., a supplier), or self self-issued data credential by the economic operator that makes the sustainability claim (e.g., manufacturer).

Figure 4 shows the changes in the credential structure as it moves from the issuer to the verifier. The core structure of the credential contains the credential metadata and the data claims. The metadata comprises the issuer DID, the subject (holder) DID address, and the type of credential. The data claims part consists of specific claims and values assigned to the claims, such as material type, material quantity, supply date, etc. The issuer of the credential signs each data claim in the credential with their private key. The verifier (which in this case is the entity that produces the proof) uses a DID resolver and associated DID document to verify the signatures in the claim before using the data in the VC for proof generation.

To use the credential structure provided in the JSON above for the circuit earlier presented, it is expected that the suppliers of the materials will provide credentials for the supply of cotton, wool, silk, and polyester with the following quantities: 3 Tonnes, 2 Tonnes, 5 Tonnes, and 10 Tonnes, respectively.

7. Discussions

7.1. Research Implication

- Sustainability fraud prevention and anti-greenwashing: The main implication of the research presented in this paper is that introducing verifiability to sustainability claims will potentially reduce greenwashing and other associated frauds. The privacy-preserving aspect of the verification provides additional motivation to economic operators and manufacturers to share verifiable claims without revealing sensitive product information. Still, the approach presented in this paper uses ZKPs for sustainability reporting and verification is not without inherent risks of manipulation. To reduce the potential risk of manufacturers using flawed production processes to generate fake proofs, the system relies on a blockchain network for data provenance from manufacturing operations, and auditors and other economic operators sign VCs for data validation. Still, the described verification system is still prone to collusion attacks and data quality limitations. Hence, a robust governance system is necessary to manage stakeholder activities in the proof generation and verification process. The paper [

27] proposes a consortium-based approach for governing stakeholders and managing infrastructure in decentralized applications. A token incentivization approach can also be adopted to reward the activities of economic operators and auditors in verifying data from other economic operators for proof generation [

28]. Practically, manufacturers can generate proof for their sustainability claims without any data verification from an external entity. Hence, a rating system can be introduced for the sustainability claims - claims without any proof, claims with ZKP proof but without input data verification, claims with proofs and input data validated by an external entity. The external entity that validates input data can be ranked based on its historical activities. In this way, the risk of fake proof generation due to collusion of economic operators is reduced. This approach of tokenized consortium governance of stakeholders in proof generation and verification also addresses the data quality concerns in ZKP proofs, addressing the problem of "garbage in data, valid proof out" with decentralized data verification.

- Extendability of sustainability claims verification: The sustainability claims formalized in this paper do not cover claims like ethical sourcing, approved suppliers, geo-bounded provenance claims, and social impact labor practice claims. The goal of formalizing sustainability claims is to ensure that a formal circuit can be generated for their verification. Hence, this research provides a foundation for more research in designing ZKP circuits and schemas for different sustainability claims by following a similar approach applied in this paper. Furthermore, the current list of sustainability claims is non-exhaustive, as these types of claims are open to addition (or even removal) of claims due to the changing regulatory landscape in sustainability research [

29,

30]. Although it is practically impossible to formalize all sustainability claims and generate ZKP circuits or algorithms for each of the claims, a proper framework is needed to navigate this challenge and prioritize claim verifications that have the most impact for consumers. The current work formalized three claims, including carbon footprint, material composition, and recycled materials, and then provided a ZKP circuit template for verifying material composition.

7.2. Adoption Pathways and Socio-Technical Challenges

Adoption of ZKPs in reporting and verifying sustainability claims in consumer products faces three main challenges, including regulatory, technical (interoperability and computing), and user experience issues.

- Regulatory readiness: ZKP provides an enabler for economic operators and manufacturers to report sustainability information about their products without revealing sensitive proprietary information. No regulation currently requires business organizations to use privacy-preserving technologies like ZKPs for their sustainability reporting. The question arises whether a separate regulation is needed for the adoption of ZKPs in supply chains and consumer-facing products. For instance, can manufacturers present ZKP proof to government compliance officers instead of full data disclosure for their auditing processes? The paper [

31] discusses how ZKPs can help public and private entities verify compliance in business operations, raising conflicting dilemmas for government oversight. Furthermore, the work [

32] notes that although the EU regulation on digital identity wallets mentions the use of ZKPs, still, no clear legal process has been established for their use. Hence, one of the steps necessary to ensure the adoption of ZKPs in product sustainability verification is to provide a clear legal framework for their use, especially in consumer-facing applications where trust and privacy are essential.

- Interoperability and technical integration challenges: Beyond the CIRPASS and GS1, there are several other implementations of DPPs for different industry sectors [

33,

34]. Hence, developing a ZKP schema and algorithms for sustainability claims verifications and integrating them into different DPP implementations will be a daunting task. One approach to solving this is to develop an independent ZKP-based sustainability reporting and verification tool and provide an API for their optional integration into existing DPPs. The DPP component can provide a presentation layer for the sustainability claims and their proofs; however, the proof generation and verification are handled by services outside of core DPP components. Besides interoperability challenges, there is also an operational computing challenge for generating and verifying ZKPs. Generating proofs consumes a lot of computing resources, especially for a large list of products in supply chains [

35]. A well-designed token incentivization mechanism will ensure that entities that provide input data verification services, proof generation, and verification services are well compensated. Integrating verifiable sustainability claims to product information improves product quality and consumer goodwill; hence, entities and organizations that enable the verification process within supply chains should be rewarded for their contributions.

- User experience challenges: Different stakeholders, consumers, manufacturers, and regulators have different expectations in using ZKPs to report and verify sustainability claims. For ZKPs to be widely adopted and accepted in supply chains, they have to be usable, especially for the consumer. The consumers’ interactions with ZKPs with mostly be for the claim verification process. For the ZKP interaction sequences presented in this paper, the consumer (verifier) will read the proof/claim data from the DPP and then verify the proof through the verification service provider components. This process can be automated through API exchanges between DPPs hosted by a supply chain entity and a verification service hosted by an external service provider. Hence, the usage of the verification service by the consumer is expected to be fast and incur no additional cost to the consumer. There are still system complexity challenges in setting and maintaining proof generation and verification[

6]. If the proof generation and verification service is outsourced to a thirdparty service provider, the manufacturer only has to cover the additional cost of the verification services provided. The manufacturer has to balance the gains from product quality and consumer goodwill (due to verifiable sustainability claims) and additional costs that ZKPs introduce to each product. The manufacturer or economic operator can also prioritize consumer products where goodwill gained balances their ZKP costs.

8. Conclusions

This work explored the application of ZKPs to extend the capabilities of DPP in presenting and verifying the sustainability claims in consumer products. Relevant sustainability claims were identified and formalized to identify necessary input and output data, useful for proof generation and verification. For instance, a range proof can be generated to show that the carbon footprint of a product is less than a specified amount. The actual amount of carbon footprint per product unit can also be presented as an output where whereas the input production activities used for their calculation are hidden from the public. The percentages of material composition or recycled content composition can be generated as the output of a proof, whereas other confidential materials and their compositions are protected from the public. A data matrix is presented for different sustainability claims, and the data sources were also examined. and trust model scenarios for input data validation are presented. The validation of input data for proof generation is necessary to ensure trust in the generated proof; otherwise, the system faces a problem of "garbage input data, valid proof output". The trust model shows different scenarios where manufacturers, other economic operators, and blockchain technologies play different roles in validating input supply chain data and generating trustable ZKP proofs. Furthermore, this work used sequence diagrams to show different components in the privacy-aware sustainability claims verification and the interactions necessary for the proof generation and verification. Lastly, a SNARK circuit is used to provide a template for the proof generation schema of a sustainability claim, and a VC structure is used to present the schema for input data validation for the proof generation service.

This work has some limitations. First, the formalization of sustainability claims and circuit templates for the proof generation does not cover all the sustainability claims that can be represented in DPPs. Secondly, although this work provides template schemas for proof generation and input data validation, the output proofs have not been integrated into an actual DPP system to evaluate the performance and usability of the approach. The main future work that will evolve from the current work is a ZKP-based sustainability reporting tool, and loosely integrate the proof presentation part into the DPP structure. The tool will expand the circuits to support different types of sustainability claims and enable automated proof generation for validated input data.

Data Availability Statement

No new data is created in this research.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to the colleagues at ABC-Research for their support towards this research.

References

- Psarommatis, F.; May, G. Digital product passport: a pathway to circularity and sustainability in modern manufacturing. Sustainability 2024, 16, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walden, J.; Steinbrecher, A.; Marinkovic, M. Digital product passports as enabler of the circular economy. Chemie Ingenieur Technik 2021, 93, 1717–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcatajo, G. Green claims, green washing and consumer protection in the European Union. Journal of Financial Crime 2023, 30, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffen, A.; Doppler, S. Building consumer trust and satisfaction through sustainable business practices with organic supermarkets: The case of Alnatura. In Case studies in food retailing and distribution; Elsevier, 2019; pp. 205–228. [Google Scholar]

- Şenyapar, H.N.D. Unveiling greenwashing strategies: A comprehensive analysis of impacts on consumer trust and environmental sustainability. Journal of Energy Systems 2024, 8, 164–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udokwu, C. Zero Knowledge Proof Solutions to Linkability Problems in Blockchain-Based Collaboration Systems. Mathematics 2025, 13, 2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, R.; Chatterjee, R. An overview of the emerging technology: Blockchain. In Proceedings of the 2017 3rd International Conference on Computational Intelligence and Networks (CINE), 2017; IEEE; pp. 126–127. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Yuan, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, J.; Qin, R.; Wang, F.Y. An overview of smart contract: architecture, applications, and future trends. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE intelligent vehicles symposium (IV), 2018; IEEE; pp. 108–113. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto, A.M. An introduction to the use of zk-SNARKs in blockchains. In Proceedings of the Mathematical Research for Blockchain Economy: 1st International Conference MARBLE 2019, Santorini, Greece, 2020; Springer; pp. 233–249. [Google Scholar]

- Bellés-Muñoz, M.; Isabel, M.; Muñoz-Tapia, J.L.; Rubio, A.; Baylina, J. Circom: A circuit description language for building zero-knowledge applications. IEEE Transactions on Dependable and Secure Computing 2022, 20, 4733–4751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, K. Verifiable credentials flavors explained. In Linux Foundation Public Health: Linux Foundation Public Health; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzocca, C.; Acar, A.; Uluagac, S.; Montanari, R.; Bellavista, P.; Conti, M. A survey on decentralized identifiers and verifiable credentials. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials; 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Shee Weng, L. Digital Product Passports: Transforming Industries Through Transparency, Circularity, and Compliance. In Digital Product Passports: Transforming Industries Through Transparency, Circularity, and Compliance November 10, 2024); 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Maigre, R.; Haav, H.; Robal, T.; Wolf, M.; Danash, F. Ontology Requirements Specification for an EU DPP Core Ontology Proposal. CIRPASS-2 Consortium, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Curado Silveirinha, J.; Bhandari, M.; Ferreira, J.C.; Martins, A.L. Enhancing maritime supply chain security and efficiency: a review of Zero-Knowledge Proofs in blockchain applications. Maritime Policy & Management 2025, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, S.; Tiwari, N.; Chawla, M.; Tomar, D.S. Zero-knowledge proofs in blockchain-enabled supply chain management. In Sustainable Security Practices Using Blockchain, Quantum and Post-Quantum Technologies for Real Time Applications; Springer, 2024; pp. 47–70. [Google Scholar]

- Sahai, S.; Singh, N.; Dayama, P. Enabling privacy and traceability in supply chains using blockchain and zero knowledge proofs. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Blockchain (Blockchain). IEEE, 2020; pp. 134–143. [Google Scholar]

- Anita, N.; Vijayalakshmi, M.; Shalinie, S.M. Blockchain-based anonymous anti-counterfeit supply chain framework. Sādhanā 2022, 47, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naga Nithin, G.; Pradhan, A.K.; Swain, G. zkHealthChain-blockchain enabled supply chain in healthcare using zero knowledge. In Proceedings of the IFIP International Internet of Things Conference, 2023; Springer; pp. 133–148. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.; Xu, J.; Wang, X.; Zhao, Z.; Chen, S.; Zhang, X. Research on the construction of grain food multi-chain blockchain based on zero-knowledge proof. Foods 2023, 12, 1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsson, R.; Nevzorova, T. Verifiable Sustainability Claims. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Malik, S.; Dedeoglu, V.; Kanhere, S.S.; Jurdak, R. PrivChain: Provenance and privacy preservation in blockchain enabled supply chains. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Blockchain (Blockchain). IEEE, 2022; pp. 157–166. [Google Scholar]

- Rani, P.; Rani, P.; Gupta, I.; Sachan, R.K.; Sharma, P. BT-CSRS: A decentralized and distributed solution for sustainable seafood supply chain system utilizing zero-knowledge proofs and permissionless blockchain. Peer-to-Peer Networking and Applications 2025, 18, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, J.; Jaffer, S.; Ferris, P.; Kleppmann, M.; Madhavapeddy, A. Emission Impossible: privacy-preserving carbon emissions claims. arXiv arXiv:2506.16347. [CrossRef]

- Sedlmeir, J.; Völter, F.; Strüker, J. The next stage of green electricity labeling: using zero-knowledge proofs for blockchain-based certificates of origin and use. ACM SIGENERGY Energy Informatics Review 2021, 1, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurent, A.; Olsen, S.I.; Hauschild, M.Z. Carbon footprint as environmental performance indicator for the manufacturing industry. CIRP annals 2010, 59, 37–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezz, M.; Alaerjan, A.S.; Mostafa, A.M. Ethical AI in Healthcare: Integrating Zero-Knowledge Proofs and Smart Contracts for Transparent Data Governance. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhal, P.; Joshi, N. Designing mathematical incentive mechanisms to encourage farmers in a ZKP-based system. Engineering Research Express 2025, 7, 035261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arayess, S.; de Boer, A. How to navigate the tricky landscape of sustainability claims in the food sector. European journal of risk regulation 2022, 13, 643–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swartz, J.J. Thinking Green or Scheming Green: How and Why the FTC Green Guide Revisions Should Address Corporate Claims of Environmental Sustainability. Penn St. Envtl. L. Rev. 2009, 18, 95. [Google Scholar]

- Bamberger, K.A.; Canetti, R.; Goldwasser, S.; Wexler, R.; Zimmerman, E.J. Verification dilemmas in law and the promise of zero-knowledge proofs. Berkeley Tech. LJ 2022, 37, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos Fernández, R. Regulatory options for integrating zero-knowledge proofs into the European Digital Identity Wallet. International Review of Law, Computers & Technology 2024, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, C.; Silva, C.J.; Abreu, M.J. Circular Economy: Literature Review on the Implementation of the Digital Product Passport (DPP) in the Textile Industry. Sustainability (2071-1050) 2025,

17

. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicaksono, H.; Mengistu, A.; Bashyal, A.; Fekete, T. Digital Product Passport (DPP) technological advancement and adoption framework: A systematic literature review. Procedia Computer Science 2025, 253, 2980–2989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokulakrishnan, D.; Sinha, T.; et al. Scalable Supply Chain Product Source Verification Using Zero-Knowledge Proofs. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Computing and Communication Technologies (ICCCT), 2025; IEEE; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).