1. Introduction

Melon (

Cucumis melo L.) is one of the most economically and nutritionally important horticultural crops worldwide, particularly in temperate and subtropical regions (Zhang et al., 2024 [

1]). It belongs to the Cucurbitaceae botanical family, and its summer fruit is valued for its sensory attributes. Among the many varieties, cantaloupe and netted melon are the most consumed, although the

flexuosus,

acidulus, and

conomon types are often used as underripe in salads or cooked preparations, while the

cantalupensis,

reticulatus, and

inodorus varieties are typically consumed ripe and fresh due to their high sugar content and aromatic features (Manchali et al., 2021 [

2]).

The sugar profile is a key determinant of fruit quality in sweet melons (Shah et al., 2025 [

3]). Immature fruits primarily contain glucose and fructose, while sucrose accumulation in the mesocarp occurs during the final maturation stage, and continues until harvest or natural abscission (Schemberger et al., 2020 [

4]; Stroka et al., 2024 [

5]). Due to the absence of starch reserves in the fruit mesocarp, sugar content does not increase after the harvest. Thus, optimal harvest timing is critical, since early harvesting can result in reduced sweetness, while delayed harvesting may compromise the fruit shelf life. Whereas the relative parts of these soluble sugars may justify some taste variation at equal total sugar content (Stroka et al., 2024 [

5]; Lestari et al.,2025 [

6]; Shah et al., 2025 [

3];), the content of total soluble solids (TSS) is a dependable quality marker (Seo et al., 2018 [

7]), and can be quickly quantified by extracting pulp juice onto a refractometer.

Melon pulp is a significant source of vitamins and dietary fibre, with low fat and caloric content (Sultana et al., 2023 [

8]). According to traditional Chinese medicine, it was used for pain relief and as a diuretic (Ezzat et al., 2019 [

9]). It is also rich in phytochemicals, such as polyphenols and β-carotene, recognized for their strong antioxidant properties (Sultana et al., 2023 [

8]). In this respect, polyphenols contribute to body protection against oxidative stress and have documented anti-inflammatory, antitumor, and cardiovascular effects (Di Sotto & Di Giacomo, 2023 [

10]).

Melon is particularly rich in vitamin A, providing approximately 112% of the recommended daily allowance (RDA) per 100 g. This nutrient supports vision, skin, and mucous membrane health, and may reduce the risk of respiratory cancers. Additionally, a melon portion of 100 g offers about 61% of the RDA for vitamin C, which bolsters immune function and limits oxidative damage (Evana et al., 2021 [

11]).

Flavonoids, including β-carotene, lutein, zeaxanthin, and cryptoxanthin, further enhance protection against serious pathologies including cancers (Gómez-García et al., 2021 [

12]). Melon is also a good source of potassium, a key electrolyte for regulating blood pressure and cardiovascular health, providing about 270 mg per 100 g (Mallek-Ayadi et al., 2022 [

13]).

Due to its sensorial attributes and nutritional profile, melon enjoys is a globally popular fruit (Farcuh et al., 2020 [

14]). In 2022, China led the global annual production (14.20 million tons), followed by Turkey (1.59 million tons), India (1.50 million tons), and Kazakhstan (1.21 million tons), while in Europe, Spain ranked first (664,000 tons), and Italy followed (593,000 tons) (FAOSTAT, 2022 [

15]).

In Italy, melon cultivation is widespread in both open-field and greenhouse with a total area of 22,888 ha, including 20,520 ha in open-field and 2,368 ha under greenhouses and tunnels, corresponding to 13.7% of total production in protected cultivation (ISTAT 2022 [

16]).

Melon production, however, faces considerable issues in open field (Pethybridge et al., 2024 [

17]), since outdoor systems are vulnerable to biotic and abiotic stresses, seasonal growth restrictions, and unpredictable weather conditions (Adamović et al., 2024 [

18]). Furthermore, open-field crops often require more intensive phyto-pathological treatments and are concentrated in regional growing period, particularly in cooler or more variable climatic areas. Conversely, protected cultivation allows a better control over climate conditions (temperature, humidity), enhancing plant performance in terms of early production and yield, while decreasing disease frequency and climatic stress (Amaroek et al., 2025 [

19]).

Vertical plant training in greenhouse is a novel approach that allows higher planting densities and optimizes space utilization and resource use efficiency (Zhuang et al., 2025 [

20]). Training melon plants vertically on trellises or supports enhances air circulation, water distribution, and nutrient management. This practice is applicable for high value horticultural crops like melon, where earliness, uniformity, and postharvest quality are fundamental market requirements (Singh et al., 2025 [

21]).

Despite these promising advantages, comparative studies evaluating the agronomic and qualitative performance of melon under greenhouse vertical training systems are limited. Particularly, data comparing ungrafted plants grown in vertical greenhouse systems compared to traditional open-field horizontal growth methods are not available in literature, and the influence of these systems on harvest earliness, yield potential, and fruit nutritional and nutraceutical composition is not known in the different commercial genotypes.

The aim of this research is to fill this gap by investigating the agronomic and qualitative responses of four ungrafted melon hybrids under two growing systems, open-field cultivation with horizontally sprawling plants and greenhouse vertical cultivation with supported plants. Our study evaluated the production earliness and fruit yield and quality and provided a trade-off of benefits and limits of each system, to guide growers toward more efficient and sustainable production strategies.

2. Results

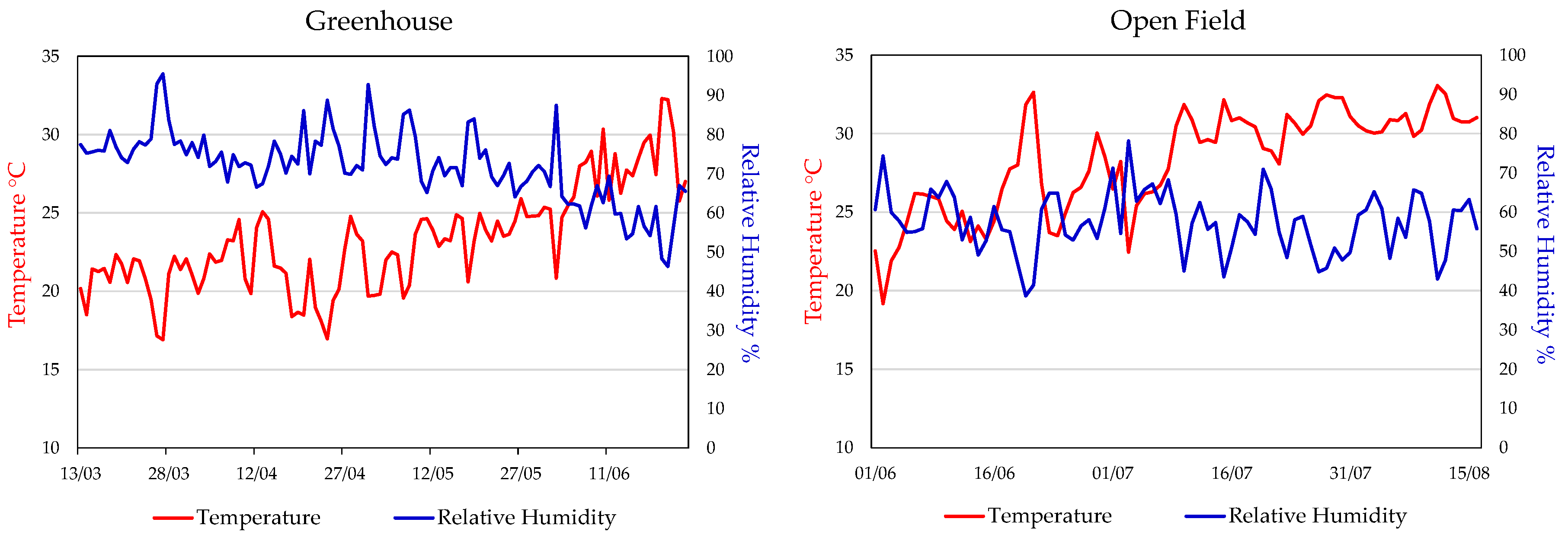

2.1. Environmental Parameters: Temperature and Relative Humidity

Figure 1 shows the temperature and relative humidity values recorded in greenhouse and open field during the two related cultivation periods. In greenhouse, data were collected daily during the sunlight period, from 6:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m. from March 13 to June 24, while in open field, data were recorded from 7:00 a.m. to 7:00 p.m. from June 01 to August 16. In greenhouse, the average temperature ranged from 15 to 25 °C for most of the period, gradually increasing to 30 °C from May to June. Relative humidity fluctuated between 70 and 90%, showing a gradual decline towards the end of cultivation period. In open field, the average temperatures ranged from 20 to 30 °C, with peaks above 30 °C in July and August. Relative humidity ranged between 40% and 80%, with frequent fluctuations caused by wind, particularly in the afternoon.

2.2. Plant Growth

Statistical analysis showed a relevant interaction between cultivation system (S) and hybrids (H) for the different analysed parameters except for SPAD, which did not show statistically significant differences.

The results reported in

Table 1 show that, overall, fresh weight, dry weight, and dry matter percentage of the whole plant (aerial part) were significantly higher in trailing plants grown in open field compared to those trained vertically in greenhouse. For example, trailing plants in open field recorded a higher fresh weight per plant (+346.9% compared to vertically grown plants in greenhouse). The dry matter percentage also showed marked differences, with 21.3% in open field versus 10.4% under vertical cultivation.

Considering the two cultivation systems separately, the different hybrids showed statistically significant responses for all the analysed parameters.

Under open field conditions, hybrids 2001, 2005, and 2008 showed the highest SPAD values, while 2003 recorded the lowest. In addition, fresh weight was slightly higher in 2001 and 2008 compared to 2003 and 2005, whereas dry weight was significantly higher in hybrid 2008 compared to the others. Finally, dry matter percentage was higher in the hybrid 2008 than in 2005 and 2003, with the lowest value recorded for 2001.

In vertical farming conditions, hybrid 2005 showed the highest SPAD value, while hybrid 2001 showed the lowest, compared to hybrids 2003 and 2008. Furthermore, fresh weight was particularly lower in hybrid 2005 compared to hybrids 2001, 2003, and 2008; whereas dry weight was lower in hybrid 2005 than in hybrids 2001 and 2008, which recorded the highest values. Finally, the percentage of dry matter showed a similar trend across all four hybrids.

Leaf greenness

2.3. Fruit Yield, Dry Matter Content, and Refractometric Index

Data analysis revealed that the interaction between cultivation system (S) and hybrid (H) had highly significant effects on all the growth parameters analysed, including fresh weight, dry weight, dry matter percentage, and fruit weight (

Table 2), with the sole exception of fruit number and fruit yield, for which the interaction was not significant.

In open field conditions, higher fruit weight, fruit number, and pulp dry matter content were recorded compared to vertical cultivation. On the other hand, in vertical cultivation, slightly higher fruit yield and Brix degrees were observed compared to open field cultivation. Particularly, in open field, hybrids 2003 and 2005 showed higher fresh weight compared to hybrids 2001 and 2008; whereas fruit number and fruit yield were higher in hybrid 2008 compared to the others, although not statistically significant. Hybrid 2005 recorded higher pulp dry matter content and Brix degrees compared to the others.

Conversely, vertical cultivation showed higher fresh weight for hybrid 2005 compared to hybrids 2001, 2003, and 2008. Hybrids 2001 and 2008 exhibited higher fruit number compared to the others, whereas fruit yield was particularly high in hybrid 2008, although not statistically significant. Moreover, hybrid 2005 showed higher pulp dry matter content and Brix degrees compared to the others.

2.4. Multielement Profile of Fruits

The analysis of carbon (C) and macronutrients content in the pulp (

Table 3) revealed that cultivation system significantly influenced the levels of nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), magnesium (Mg), and sodium (Na), which were higher under greenhouse vertical cultivation compared to conventional open field conditions. For example, the N content in fruits from plant grown in the vertical system reached 18.3 g kg

−1, compared to 14.6 g kg

−1 in the open field. Similarly, P and Na concentration was higher in vertical cultivation, and a similar trend was noted for Mg.

Significant differences in the pulp composition were also found among hybrids. Hybrid 2003 stood out for the high P content (3.76 g kg−1) and shared the highest accumulation of potassium (K), N, calcium (Ca), and Mg with hybrid 2001. Additionally, 2003 showed the lowest Na concentration. Hybrid 2005 was characterized by the highest Ca and the lowest K level. No significant differences in C content were observed among the hybrids, while P level exhibited a descending gradient across genotypes. The interaction between cultivation system and hybrid (S×H) was statistically significant for several macronutrients (e.g., N, P, and Mg), while not significant for the microelements.

Table 5 presents the concentration in the pulp of key microelements detected, such as iron (Fe), manganese (Mn), boron (B), zinc (Zn), copper (Cu), molybdenum (Mo), selenium (Se). Cultivation system significantly influenced the accumulation, with higher values in fruits from plants grown in greenhouse compared to those from open field. In contrast, Cu showed the opposite trend, with higher concentration recorded in open field compared to greenhouse. No significant differences between the two cultivation systems were found for the remaining microelements.

Significant differences were also observed among hybrids for all analysed microelements. Hybrids 2001 and 2003 showed significantly higher concentration of Fe, Mn, Zn, and Se, whereas hybrids 2005 and 2008 accumulated lower levels of these elements except for Mo, which was highest in hybrid 2008. Additionally, hybrid 2001 recorded the highest Cu content, while the lowest was measured in hybrid 2008.

Regarding the concentration of macro elements, Na, and C in the exocarp (Table 5), the cultivation system had a highly significant effect on K, P, Mg, and Na, with higher values in vertical greenhouse cultivation. For instance, P content reached 6.98 g kg−1 in vertical cultivation compared to 3.74 g kg−1 in open field. Conversely, Ca was higher under open field conditions than in the vertical system.

When comparing hybrids, N showed highly significant differences, with hybrids 2008 and 2001 exhibiting the highest values (24.3 g kg−1 on average). Significant differences also emerged for K, Mg, and Na, with hybrid 2005 showing the lowest K concentration and the others with similar values; hybrid 2003 reaching the highest Mg content, while the remaining hybrids had comparable values. Differences were less pronounced for Na, with the only significant contrast was between hybrid 2005 (highest) and 2001 (lowest).

The interaction between the cultivation system and hybrid (S×H) was not significant for most macro elements, except for P and Mg. Specifically, vertical cultivation resulted in the highest content of P for hybrid 2008 (8.48 g kg−1) and Mg for hybrid 2003 (4.77 g kg−1).

The analysis presented in Table 6 regarding microelement concentration in the peel shows that cultivation system significantly influenced most of the measured elements. Among them, Mo stands out in particular: under vertical cultivation, its concentration was nearly 10 times higher than that in open field conditions (0.695 vs. 0.070 ppm). Vertical cultivation also promoted a higher accumulation of Mn, B, Zn, and Se. In contrast, Cu levels were higher under open field than in greenhouse.

Table 4.

Content of microelements (ppm) in the pulp of melon fruits of the four tested hybrids, 2001, 2003, 2005, and 2008, grown in the two cultivation systems, open field with trailing growth (FT) and greenhouse with vertical training (GV).

Table 4.

Content of microelements (ppm) in the pulp of melon fruits of the four tested hybrids, 2001, 2003, 2005, and 2008, grown in the two cultivation systems, open field with trailing growth (FT) and greenhouse with vertical training (GV).

| Treatment |

Fe |

Mn |

B |

Zn |

Cu |

Mo |

Se |

| Cultivation system (S) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| FT |

25.5 ± 0.94 |

6.36 ± 0.52 |

12.1 ± 0.49 |

12.07 ± 0.88 |

4.8 ± 0.2 |

0.069 ± 0.024 |

0.020 ± 0.002 |

| VT |

30.4 ± 1.89 |

6.98 ± 0.82 |

17.7 ± 1.12 |

15.47 ± 1.99 |

3.92 ± 0.3 |

0.183 ± 0.021 |

0.025 ± 0.003 |

| Hybrid (H) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2001 |

32 ± 2.72 a |

7.69 ± 1.05 ab |

15.7 ± 1.2 b |

19.17 ± 1.8 a |

5.47 ± 0.21 a |

0.139 ± 0.036 b |

0.029 ± 0.003 ab |

| 2003 |

31.5 ± 1.67 a |

9.38 ± 0.67 a |

18.5 ± 2.03 a |

17.59 ± 2.47 a |

4.55 ± 0.39 b |

0.098 ± 0.030 bc |

0.030 ± 0.004 a |

| 2005 |

21.6 ± 0.74 b |

4.09 ± 0.3 c |

11.2 ± 0.55 c |

9.38 ± 0.39 b |

3.83 ± 0.26 bc |

0.044 ± 0.016 c |

0.018 ± 0.002 bc |

| 2008 |

26.6 ± 1.31 ab |

5.51 ± 0.38 bc |

14.1 ± 1.06 b |

8.96 ± 0.27 b |

3.6 ± 0.32 c |

0.225 ± 0.036 a |

0.016 ± 0.002 c |

| SxH |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| FT X 2001 |

28 ± 2.01 |

5.8 ± 0.61 bc |

13.5 ± 1.19 cd |

15.12 ± 0.53 |

5.27 ± 0.28 a |

0.057 ± 0.027 |

0.024 ± 0.005 |

| FT X 2003 |

27.8 ± 1.33 |

8.9 ± 1.01 ab |

13.4 ± 0.56 cd |

15.5 ± 1.02 |

5.37 ± 0.45 a |

0.024 ± 0.005 |

0.024 ± 0.003 |

| FT X 2005 |

21.3 ± 0.93 |

4.42 ± 0.57 c |

9.8 ± 0.33 d |

8.51 ± 0.31 |

4.27 ± 0.2 ab |

0.002 ± 0.003 |

0.016 ± 0.002 |

| FT X 2008 |

24.6 ± 1.06 |

6.31 ± 0.41 abc |

11.6 ± 0.16 d |

9.16 ± 0.28 |

4.3 ± 0.38 ab |

0.194 ± 0.058 |

0.018 ± 0.002 |

| GV X 2001 |

36 ± 4.48 |

9.59 ± 1.53 ab |

17.9 ± 1.42 b |

23.22 ± 1.98 |

5.68 ± 0.3 a |

0.221 ± 0.029 |

0.033 ± 0.003 |

| GV X 2003 |

35.2 ± 1.48 |

9.85 ± 0.98 a |

23.5 ± 1.3 a |

19.67 ± 4.96 |

3.74 ± 0.26 b |

0.172 ± 0.024 |

0.034 ± 0.008 |

| GV X 2005 |

21.9 ± 1.27 |

3.75 ± 0.12 c |

12.5 ± 0.34 d |

10.24 ± 0.32 |

3.38 ± 0.36 b |

0.085 ± 0.006 |

0.020 ± 0.002 |

| GV X 2008 |

28.5 ± 2.1 |

4.72 ± 0.29 c |

16.7 ± 0.87 bc |

8.76 ± 0.5 |

2.91 ± 0.13 b |

0.255 ± 0.044 |

0.014 ± 0.003 |

| Cultivation system (S) |

* |

ns |

*** |

ns |

* |

** |

ns |

| Hybrid (H) |

*** |

*** |

*** |

*** |

*** |

*** |

** |

| SxH |

ns |

* |

** |

ns |

* |

ns |

ns |

Table 5.

Content of macroelements, carbon, and sodium (g kg−1) in the peel of melon fruits in the four tested hybrids, 2001, 2003, 2005, and 2008, grown in the two cultivation systems, open field with trailing growth (FT) and greenhouse with vertical training (GV).

Table 5.

Content of macroelements, carbon, and sodium (g kg−1) in the peel of melon fruits in the four tested hybrids, 2001, 2003, 2005, and 2008, grown in the two cultivation systems, open field with trailing growth (FT) and greenhouse with vertical training (GV).

| Treatment |

C |

K |

N |

S |

P |

Ca |

Mg |

Na |

| Cultivation system (S) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| FT |

411 ± 2.07 |

47.7 ± 1.06 |

21.76 ± 1.04 |

4.59 ± 0.5 |

3.74 ± 0.16 |

6.56 ± 0.31 |

2.78 ± 0.08 |

1.36 ± 0.08 |

| GV |

413 ± 4.02 |

41 ± 1.33 |

22.79 ± 0.8 |

4.23 ± 0.39 |

6.98 ± 0.29 |

5.44 ± 0.39 |

3.92 ± 0.17 |

2.71 ± 0.2 |

| Hybrid (H) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2001 |

418 ± 6.27 |

45.2 ± 1.29 a |

24.15 ± 1.04 a |

4.55 ± 0.64 |

5.08 ± 0.62 b |

6.1 ± 0.3 |

3.26 ± 0.24 ab |

1.62 ± 0.23 b |

| 2003 |

408 ± 3.95 |

45.7 ± 1.25 a |

22.04 ± 0.9 ab |

3.39 ± 0.13 |

5.26 ± 0.67 b |

6.59 ± 0.52 |

3.79 ± 0.38 a |

1.83 ± 0.24 ab |

| 2005 |

417 ± 3.36 |

39.8 ± 2.85 b |

18.53 ± 1.26 b |

4.3 ± 0.75 |

4.82 ± 0.48 b |

4.96 ± 0.67 |

3.18 ± 0.23 b |

2.53 ± 0.37 a |

| 2008 |

405 ± 2.16 |

46.8 ± 1.74 a |

24.4 ± 0.92 a |

5.39 ± 0.67 |

6.3 ± 0.84 a |

6.33 ± 0.46 |

3.16 ± 0.21 b |

2.15 ± 0.38 ab |

| SxH |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| FT X 2001 |

410 ± 4.64 |

47.2 ± 1.8 |

22.8 ± 1.87 |

5.36 ± 1.18 |

3.53 ± 0.24 c |

6.33 ± 0.35 |

2.64 ± 0.11 c |

1.02 ± 0.08 |

| FT X 2003 |

412 ± 5.73 |

47.9 ± 1.68 |

20 ± 0.92 |

3.66 ± 0.11 |

3.6 ± 0.35 c |

6.38 ± 0.98 |

2.82 ± 0.16 c |

1.38 ± 0.13 |

| FT X 2005 |

415 ± 4.51 |

45.8 ± 2.65 |

18.9 ± 2.66 |

3.37 ± 0.2 |

3.73 ± 0.46 c |

6.41 ± 0.73 |

2.87 ± 0.21 bc |

1.7 ± 0.15 |

| FT X 2008 |

409 ± 1.71 |

49.9 ± 2.52 |

25.35 ± 1.27 |

5.96 ± 1.37 |

4.12 ± 0.2 c |

7.09 ± 0.47 |

2.77 ± 0.15 c |

1.35 ± 0.11 |

| GV X 2001 |

426 ± 10.8 |

43.3 ± 1.39 |

25.5 ± 0.6 |

3.75 ± 0.22 |

6.63 ± 0.35 b |

5.88 ± 0.5 |

3.87 ± 0.08 ab |

2.23 ± 0.05 |

| GV X 2003 |

404 ± 5.34 |

43.4 ± 1.06 |

24.08 ± 0.38 |

3.12 ± 0.12 |

6.91 ± 0.4 ab |

6.8 ± 0.52 |

4.77 ± 0.18 a |

2.29 ± 0.35 |

| GV X 2005 |

418 ± 5.54 |

33.8 ± 2.6 |

18.15 ± 0.5 |

5.23 ± 1.42 |

5.91 ± 0.28 b |

3.52 ± 0.42 |

3.48 ± 0.37 bc |

3.35 ± 0.38 |

| GV X 2008 |

402 ± 3.36 |

43.8 ± 1.3 |

23.45 ± 1.33 |

4.81 ± 0.13 |

8.48 ± 0.34 a |

5.56 ± 0.61 |

3.56 ± 0.28 bc |

2.95 ± 0.47 |

| Cultivation system (S) |

ns |

*** |

ns |

ns |

*** |

* |

*** |

*** |

| Hybrid (H) |

ns |

** |

*** |

ns |

*** |

ns |

* |

* |

| SxH |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

* |

ns |

* |

ns |

Table 6.

Content of microelements (ppm) in the peel of melon fruits in the four tested hybrids, 2001, 2003, 2005, and 2008, grown in the two cultivation systems, open field with trailing growth (FT) and greenhouse with vertical training (GV).

Table 6.

Content of microelements (ppm) in the peel of melon fruits in the four tested hybrids, 2001, 2003, 2005, and 2008, grown in the two cultivation systems, open field with trailing growth (FT) and greenhouse with vertical training (GV).

| Treatment |

Fe |

Mn |

B |

Zn |

Cu |

Mo |

Se |

| Cultivation system (S) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| FT |

62.1 ± 2.61 |

16.6 ± 0.88 |

25.8 ± 0.6 |

17.3 ± 1.13 |

7.36 ± 0.71 |

0.070 ± 0.020 |

0.024 ± 0.002 |

| GV |

66 ± 3.79 |

79.7 ± 7.81 |

30.2 ± 1.26 |

27.3 ± 2.5 |

4.83 ± 0.37 |

0.695 ± 0.128 |

0.033 ± 0.002 |

| Hybrid (H) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2001 |

79.1 ± 4.27 a |

47.5 ± 13.8 ab |

26.8 ± 0.81 b |

29.4 ± 2.54 a |

8.39 ± 0.9 a |

0.355 ± 0.098 b |

0.030 ± 0.003 a |

| 2003 |

61.1 ± 3.1 b |

61.6 ± 18 a |

32.1 ± 2.06 a |

22.1 ± 4.58 ab |

5.84 ± 0.51 b |

0.236 ± 0.091 b |

0.026 ± 0.002 a |

| 2005 |

54.1 ± 3.11 b |

33 ± 5.74 b |

24.9 ± 0.84 b |

19.7 ± 2.72 b |

4.47 ± 0.58 b |

0.173 ± 0.062 b |

0.024 ± 0.002 b |

| 2008 |

61.9 ± 2.61 b |

50.6 ± 15.1 ab |

28.2 ± 1.19 b |

18.1 ± 1.05 b |

5.67 ± 1.05 b |

0.766 ± 0.273 a |

0.034 ± 0.004 a |

| SxH |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| FT X 2001 |

71.3 ± 4.15 |

16.2 ± 0.84 c |

25.7 ± 1.03 b |

23.3 ± 1.35 |

9.96 ± 1.39 |

0.117 ± 0.063 bc |

0.026 ± 0.005 |

| FT X 2003 |

62.4 ± 3.82 |

14.6 ± 2.73 c |

26.9 ± 1.08 b |

15.9 ± 1.36 |

6.74 ± 0.79 |

0.030 ± 0.005 c |

0.021 ± 0.002 |

| FT X 2005 |

50.6 ± 4.26 |

18.3 ± 2.14 c |

24.5 ± 1.24 b |

13.1 ± 1.68 |

4.95 ± 1.04 |

0.016 ± 0.006 c |

0.023 ± 0.004 |

| FT X 2008 |

64.2 ± 3.56 |

17.3 ± 0.5 c |

26.3 ± 1.56 b |

16.9 ± 0.97 |

7.77 ± 1.48 |

0.118 ± 0.027 bc |

0.028 ± 0.004 |

| GV X 2001 |

87 ± 5.17 |

78.7 ± 15.5 ab |

27.9 ± 1.06 b |

35.6 ± 1.69 |

6.83 ± 0.5 |

0.592 ± 0.060 b |

0.035 ± 0.004 |

| GV X 2003 |

59.7 ± 5.38 |

108.6 ± 5.52 a |

37.3 ± 0.85 a |

28.3 ± 8.39 |

4.94 ± 0.23 |

0.441 ± 0.103 bc |

0.031 ± 0.002 |

| GV X 2005 |

57.6 ± 4.36 |

47.7 ± 2.29 bc |

25.3 ± 1.28 b |

26.2 ± 1.8 |

3.99 ± 0.58 |

0.331 ± 0.040 bc |

0.026 ± 0.002 |

| GV X 2008 |

59.6 ± 3.94 |

84 ± 17.8 ab |

30.1 ± 1.34 b |

19.3 ± 1.79 |

3.58 ± 0.23 |

1.414 ± 0.261 a |

0.040 ± 0.004 |

| Cultivation system (S) |

ns |

*** |

** |

*** |

** |

*** |

** |

| Hybrid (H) |

*** |

* |

*** |

* |

** |

*** |

* |

| SxH |

ns |

* |

** |

ns |

ns |

*** |

ns |

Hybrids exhibited differences in microelement accumulation in the peel: hybrid 2008 stood out with the highest Mo content, while the other hybrids had similar values; 2003 had the highest B concentration; 2001 showed significantly higher levels of both Fe and Cu. In absolute terms, Mn was most accumulated in hybrid 2003, although it did differ significantly only from hybrid 2005. A similar trend was observed for Zn, which showed lower levels in hybrids 2005 and 2008 compared to hybrid 2001. The Se was significantly lower in the peel of hybrid 2005 compared to the others.

Regarding the interaction between cultivation system and hybrid (S×H), it was highly significant for Mo, with hybrid 2008 in greenhouse showing higher values than any other combination. Significant interactions were also found for Mn and B, with hybrid 2003 in greenhouse recording the highest values. No significant interactions were observed for the other microelements.

2.5. Phenolic Profile of Melon Fruits

Quantification of specific polyphenols within the melon sample extracts was performed using UHPLC-Q-Orbitrap HRMS. To ensure both precision and accuracy, calibration curves were prepared in triplicate across eight concentration levels, demonstrating excellent linearity with regression coefficients (R2) exceeding 0.990. Untargeted analysis in full-scan HRMS mode enabled the identification of vanillic acid and provided comprehensive data for the retrospective analysis of additional compounds. Structural characterization of untargeted compounds was confirmed through accurate mass measurements, elemental composition assignment, and interpretation of MS/MS spectra.

Quantitative results are presented in Table 7, with average contents expressed in micrograms per gram (μg g−1) of extract. These findings provide valuable insights into the polyphenolic composition and concentrations in the extracts derived from melon samples, supporting the reliability and accuracy of the quantification process. The data revealed a significant interaction between the cultivation system and hybrid only for vanillic acid. This pattern appears to be largely driven by vanillic acid itself, which was found at much higher concentrations than other identified phenolic acids and flavonoids.

Table 7.

Polyphenol content (µg g−1) in the pulp of four melon hybrids (2001, 2003, 2005, and 2008), grown under two cultivation systems: open field with trailing growth (FT) and greenhouse with vertical training (GV).

Table 7.

Polyphenol content (µg g−1) in the pulp of four melon hybrids (2001, 2003, 2005, and 2008), grown under two cultivation systems: open field with trailing growth (FT) and greenhouse with vertical training (GV).

| Treatment |

Phenolic acid |

Flavonoids |

Vanillic acid |

Total phenols |

| Cultivation system (S) |

|

| FT |

22.75 ± 2.74 |

0.37 ± 0.11 |

55.83 ± 6.28 |

68.48 ± 6.87 |

| GV |

19.3 ± 2.24 |

11.37 ± 3.94 |

53.12 ± 7.2 |

83.79 ± 11.5 |

| Hybrid (H) |

|

|

|

|

| 2001 |

30.9 ± 3.19 a |

11.64 ± 7.44 |

73.78 ± 5.64 a |

107.1 ± 13.34 a |

| 2003 |

24.97 ± 2.9 ab |

9.1 ± 3.37 |

63.84 ± 7.75 a |

89.94 ± 11.72 a |

| 2005 |

14.79 ± 1.17 b |

0.15 ± 0.03 |

26.13 ± 7.83 b |

37.79 ± 7.41 c |

| 2008 |

13.44 ± 2.34 b |

2.59 ± 2.21 |

53.69 ± 7.73 a |

69.72 ± 7.26 b |

| SxH |

|

|

|

|

| FT X 2001 |

32.77 ± 5.39 |

0.42 ± 0.17 |

63.81 ± 2.98 a |

81.05 ± 14.01 bc |

| FT X 2003 |

25.19 ± 6.1 |

0.31 ± 0.2 |

51.91 ± 12.04 ab |

64.43 ± 11.05 cd |

| FT X 2005 |

16.81 ± 1.51 |

0.08 ± 0.03 |

38.2 ± 17.16 ab |

45.54 ± 14.63 cd |

| FT X 2008 |

16.22 ± 4.43 |

0.66 ± 0.37 |

66.02 ± 12.51 a |

82.9 ± 10.38 abc |

| GV X 2001 |

29.04 ± 3.99 |

22.86 ± 13.21 |

81.26 ± 7.96 a |

133.15 ± 13.46 a |

| GV X 2003 |

24.76 ± 1.35 |

17.89 ± 1.13 |

72.79 ± 8.69 a |

115.44 ± 9.24 ab |

| GV X 2005 |

12.76 ± 1.16 |

0.21 ± 0.04 |

17.08 ± 1.93 b |

30.05 ± 1.53 d |

| GV X 2008 |

10.65 ± 0.82 |

4.53 ± 4.48 |

41.36 ± 4.56 ab |

56.54 ± 4.7 cd |

| Cultivation system (S) |

ns |

** |

ns |

ns |

| Hybrid (H) |

*** |

ns |

*** |

*** |

| SxH |

ns |

ns |

* |

*** |

3. Discussion

This study analysed the productive and qualitative performance of four hybrids of melon grown under two different cultivation systems: the traditional open field method with trailing plants on the ground and the greenhouse vertical cultivation. The primary aim was to evaluate the plant response to these cultivation systems, which differ in both growth environments and plant management practices. Besides, the study also explored the specific response based on genotype intrinsic features, highlighting the advantages and limitations of each system on the specific genetic material.

Open field cultivation of melon is particularly suited in subtropical regions, allowing for the extensive use of land to produce high quality produce (McCreight et al. 2020 [

22]). However, it is limited by climatic factors such as unfavourable weather conditions and higher susceptibility to phytopathogenic attacks (Maniçoba et al. 2023 [

23]). In contrast, vertical cultivation in protected environment (greenhouse, tunnel) offers several advantages over open field, including higher planting density and better space utilization (Jain et al. 2023 [

24]), particularly beneficial in areas where cultivable land is limited (Battistel, 2014 [

25]). Experimental results showed more uniform fruit growth and improved quality traits in open field, such as colour, firmness, and sugar content, likely due to better exposure of the canopy to solar radiation (Gruda et al. 2025 [

26]).

In our experiment, analysing the differences in the trend of climatic parameters in the two growth environments is essential for interpreting results. In greenhouse (March 13 – June 24), temperature (T) and humidity (RH) remained relatively stable, with a few peaks of T exceeding 30 °C, preventing climate related stress and supporting uniform plant development. In open field (May 30 – August 16), greater fluctuations of both T and RH may have negatively affected plant growth and increased crop sensitivity to pathogens. Nevertheless, environmental stress has not always negative effects, as it can promote the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites, useful to increase the plant tolerance, with beneficial effects in human health (Weng et al., 2022 [

27]).

The SPAD index, an indirect measure of chlorophyll content based on leaf greenness and nitrogen content in plant tissue and a useful marker of the plant nutritional status (Peterson et al. 1993 [

28]) revealed no sign of nutrient deficiency regardless of cultivation system.

Plants grown in open field exhibited significantly higher biomass compared to those in greenhouse. This difference can be attributed to the lower planting density, which reduced the plant competition for nutrients (Vescera & Brown, 2016 [

29]), as well as to the cultivation practice, since plants grown vertically were pruned at the topped to be conformed to the system. Besides, possible water and environmental stress in the field likely contributed to the accumulation of soluble sugars and a corresponding increase in dry matter content (Weng et al., 2022 [

27]). However, in terms of fruit production, greenhouse vertical cultivation outperformed the traditional ground-level growth in open field (+18.1% in fruit yield per m

2, on the average of the 4 hybrids). This is mainly due to the more homogeneous climatic conditions, as well as the higher planting density (2.2 vs. 0.5 plants m

−2 in open field). In this respect, while the higher density notably reduced the vegetative biomass, it did not affect fruit production, allowing for a greater number of fruits per unit area (m

2) in greenhouse (Vatistas et al. 2022 [

30]).

In our experiment, the varietal response revealed a critical importance for fruit quality. For the hybrids 2001 and 2003, the refractometric index (in Brix degrees), which indicates the total soluble solids content, was higher in fruits from plants in open field, whereas 2005 exhibited higher values in those from greenhouse. The hybrid 2008, on the other hand, showed no sensitivity to the growth environment, with similar a refractometric index in both systems. This evidence highlights the need to balance yield and quality based on the available plant genotype and cultivation environment, and on specific commercial objectives.

Fruits grown under protected conditions exhibited higher concentration of N, P, Mg, and Na compared to those from open field, suggesting that the controlled environment improved the nutrient uptake, likely due to the reduced leaching and lower weed competition as well as the better fertigation management (Vatistas et al. 2022 [

30]). Furthermore, fruits from the vertical greenhouse system exhibited higher uptake of Fe, B, Mo, and Cu. Notably, B content was 46% higher than that in fruits from open field, confirming the better fertilization in the protected system. These findings underscore the significant influence of the growing environment on plant physiological responses and the importance of tailoring cultivation practices to the desired produce features (Dong et al., 2019 [

31]).

Among the plant genotypes, the hybrid 2005 showed the lowest K content, possibly due to inherent genetic traits or a higher sensitivity to heat stress (Amarasinghe et al., 2021 [

32]).

The analysis of macro and microelements in the fruit peel revealed a different pattern compared to the pulp. The Ca and K content was significantly higher in fruits from open field. This is likely related with the climacteric ripening process, which is influenced by environmental factors that may stimulate the accumulation of Ca and K in the peel as an adaptive response to enhance cell wall strength and improve mechanical and osmotic resistance (Ríos et al., 2017 [

33]).

Micronutrient data showed that fruits produced in greenhouse exhibited higher levels of all elements except Cu, probably due to the more frequent application of phytosanitary treatments in open field: for instance, copper-based products (e.g., copper oxychloride, Cu

2(OH)

3Cl) were used in the field to prevent and control fungal diseases, such as downy mildew (

Pseudoperonospora cubensis). However, Cu

2(OH)

3Cl leaves residues on plant tissues, especially on the peel, which is often rougher and more retentive (Pscheidt & Ocamb, 2022 [

34]).

In the hybrids comparison, once again, hybrid 2005 demonstrated a lower capacity to accumulate most micronutrients, likely due to genetic traits limiting the nutrient uptake or translocation within the fruit (Hsieh & Waters, 2016 [

35]).

Within the broad class of bioactive compounds, polyphenols are of considerable interest due to their protective and preventive effects against chronic diseases, including cardiovascular disorders, cancer, and neurodegenerative conditions in the human body (Durazzo et al., 2019 [

36]). Although the total polyphenol content in the analysed melon samples was relatively low, the presence of vanillic acid is noteworthy for its documented antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antitumor properties.

Total phenolic compound content in the samples varied significantly, ranging from 18.96 µg g

−1 to 109.72 µg g

−1. This variability is consistent with findings by Wang et al. (2023) [

37], who reported free phenolic content in the pulp of six melon varieties grown in China’s Hainan Province, with values ranging from 193.29 µg g

−1 to 1830.11 µg g

−1.

The cultivation system showed a significant effect only on flavonoid content. Melons grown on vertically trained plants in greenhouse had a significantly higher flavonoid concentration (11.37 µg g

−1) compared to those cultivated in the open field (0.37 µg g

−1). This result aligns with findings by Mallek-Ayadi et al. (2022) [

13], who suggested that the growing environment may differentially influence various classes of phenolic compounds. Therefore, it can be hypothesized that greenhouse cultivation using vertical architecture may promote greater flavonoid biosynthesis.

The analysed hybrids displayed significant differences across nearly all parameters, indicating a genetic aptitude for synthesizing specific phenolic acids (Singh et al., 2025 [

21]). Vanillic acid may enhance the nutraceutical quality of the fruit (Kolaylı et al., 2010 [

38], Silveira et al. 2015 [

39]), making melon fruits not only a pleasant to be consumed but also a functional food with recognized health promoting properties (Calixto-Campos et al., 2015 [

40]). In our samples, vanillic acid emerged as one of the most abundant compounds, reaching the maximum level of 99.30 µg g

−1. This value exceeds those reported by Mallek-Ayadi et al. (2022) [

13], who found concentrations of 7.24 mg 100 g

−1 in the pulp of the ‘

Maazoun’ melon cultivar. Conversely, Wang et al. (2023) [

37] detected free vanillic acid in only one sample, at a concentration of 0.38 µg g

−1. In their study, the predominant compound was a vanillin derivative, ethyl vanillin, with concentrations up to 123.90 µg g

−1. Rodríguez-Pérez et al. (2013) [

41] also identified hexoxide derivatives of vanillic acid, confirming its occurrence in multiple forms in melons, including the ‘

Cantaloupe’ variety. In our study, hybrids 2001 and 2008 consistently exhibited high vanillic acid content in both open field and greenhouse systems. Hybrid 2001 stood out as having the highest total phenolic content. Beyond its inherent genetic traits, this elevated production may be linked to a cultivar-specific response to environmental stress (such as excess ultraviolet radiation), which may have stimulated secondary metabolism pathways to synthesize these compounds as a means of adaptation or protection against oxidative stress (Chalker-Scott & Fuchigami, 2018 [

42]).

Conclusions

Our study demonstrated that cultivation system and plant genotype significantly affect both the fruit production and the nutritional–nutraceutical quality of fruits in melon (Cucumis melo L.). Vertical cultivation under greenhouse conditions was particularly effective in optimizing the space use efficiency, leading to higher yield per unit area and facilitating multiple cropping cycles per year. This approach is especially advantageous for intensive or small-scale farming operations. Notably, fruits produced I greenhouse exhibited high concentration of flavonoids and vanillic acid, thereby enhancing their nutraceutical profile and potential health-promoting properties.

Among the evaluated hybrids, genotypes 2005 and 2008 demonstrated higher yield and soluble solids content across both cultivation systems, underscoring their adaptability and agronomic potential. The observed genetic variability among the hybrids further highlights the importance of targeted genotype selection in relation to the production system. Such strategic matching between genotype and cultivation method can contribute to achieving desired agronomic performance, fruit quality, and market alignment.

Overall, these findings provide a valuable basis for breeding programs and grower decision-making, supporting the selection of melon hybrids best suited to specific environmental conditions and production systems. The integration of genotype-specific responses with optimized cultivation strategies can contribute to the sustainable production of melon, ensuring both high yield and improved fruit quality.

In conclusion, the individual hybrid results reveal a noteworthy degree of genetic variability, underscoring the critical importance of matching varietal selection to the cultivation environment. Such alignment can enhance the plant’s adaptability to the cropping system and ultimately help producers achieve improved yield and fruit quality.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Material and Crop Management

The experiment was conducted during the spring–summer season of 2024 at the Bayer Research Centre in Latina (Italy). We compared two cultivation systems, vertical greenhouse cultivation and traditional crawling open-field cultivation, using four commercial hybrids of melon (Cucumis melo L.), 2001 and 2003 (Italian netted, short shelf-life – SSL type), 2005 (Amarillo type), and 2008 (Galia, long shelf-life – LSL type).

In greenhouse, the experiment was conducted in a 36.48 m2 area (19.2 m × 1.9 m). Plants were arranged in three rows, each containing one replicate of the four hybrids. In open field, the trial covered 192 m2 (38.4 m × 5.0 m), using three central rows, each also hosting one replicate per treatment in a similar layout.

Seeds were sown on 9 February 2024 in 84-cell trays and pre-germinated for 72 h at 22.5 °C and 78% relative humidity, then seedlings were transferred to a heated nursery. On 13 March, plants with 2 true leaves were manually transplanted into greenhouse. In open field, sowing and transplanting were performed on 26 April and 30 May 2024, respectively, according to the usual practice of the farm. Transplants were initially protected using mini-tunnels (0.80 m height, 0.60–0.70 m width), consisting in iron semicircles and covered with nonwoven geotextile, increasing air temperature by more than 10 °C and soil temperature by 2–3 °C compared to outside. Tunnels were removed between 23 and 25 June to allow for plant acclimatation. Honeybee (Apis mellifera) hives were used to ensure adequate pollination.

In both the environments, soil was classified as sandy loam, with a pH of 6.8, organic matter content of 1.14%, total nitrogen (N) of 0.075%, and a C:N ratio of 8.8. Irrigation was managed according to the crop requirement in each environment, and fertigation was applied during the vegetative phase using a balanced N–P–K fertilizer enriched with micronutrients. Foliar applications of micronutrient-based fertilizers containing B and Mg were also carried out. Once fruits reached approximately 8 cm in diameter, 3 additional fertigation events were performed with potassium sulphate to support fruit development. In open field, post-trans plant fertigation was supplemented with calcium, magnesium, and ammonium nitrate during vegetative growth. Following the removal of protective tunnels, 5 additional fertigation treatments were applied to promoter fruit growth and ripening. In greenhouse, the harvest started on 16 June and ended on 24 June, based on physiological maturity, assessed by peduncle detachment and days from fruit set. In open field, the harvest was conducted from 28 July to 16 August, following the same criteria. In both cases, harvest was done progressively to match the fruit ripening rhythm. In both cultivation systems, temperature and relative humidity (RH) were continuously monitored throughout the entire crop cycle using the automated PRIVA system (De Lier, The Netherlands). Daily mean values were calculated from hourly data (

Figure 1).

4.2. Fruit Production and Quality Traits

At each harvest, plant productivity was assessed by recording the number of fruits per plant and the total yield, expressed in kg m−2. Fruits at physiological maturity were harvested daily, individually counted, cut and weighed.

Total soluble solids (TSS) were measured on the juice of each fruit using a portable optical refractometer with automatic temperature compensation (ATC Refractometer, Brix range 0–32%), and values were expressed as °Brix. For each treatment (hybrid per cultivation environment), fresh biomass was determined on one representative fruit per replicate (3 fruits in total per treatment). Each fruit was divided into two sub-samples: one was immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, lyophilized, and stored at –80 °C for future phytochemical analyses, and the other was used to determine water content by oven drying at 70 °C until constant weight (~72 h). Dried tissues were ground to a particle size of 0.5 mm using a cutting-head mill (IKA MF 10.1, Staufen, Germany) for subsequent mineral content analysis.

At the end of the cultivation cycle, the above ground plant biomass, including stems and leaves, was harvested and weighed to determine the fresh weight. Plant samples were then dried in kraft paper bags (40 × 60 cm) at 65 °C for 48 h to determine the dry matter content.

4.3. SPAD Index Determination

SPAD index measurement provides an indirect estimate of leaf chlorophyll content, which is closely associated with photosynthetic activity and tissue nitrogen concentration [

28]. SPAD values are commonly used to assess crop nutritional status under field conditions [

3]. Measurements were taken using a SPAD-502 Plus chlorophyll meter (Minolta Corp. Ltd., Osaka, Japan). The instrument measures light transmittance through leaves at two wavelengths: ~650 nm (red, high chlorophyll absorbance) and ~930 nm (infrared, low absorbance) (Xiong et al. 2015) [

43]. Light passing through the leaf is captured by a photodiode and converted into an electric signal, which is processed into a SPAD unit. SPAD readings were conducted during fruit set, on well-developed leaves (Yuan et al. 2016) [

44]. Measurements were taken from three different points on the fourth leaf from the apical meristem. Data were recorded in Microsoft Excel for subsequent statistical analysis.

4.4. Multi Elemental Profile Evaluation

Total Carbon (C), nitrogen (N), and sulfur (S) concentrations were measured in freeze-dried, powdered samples (2 mg) using a Micro Elemental Analyzer (UNICUBE®, Elementar, Germany), calibrated with sulphanilamide (99.5%) for quality control. Total concentrations of Ca, P, K, Mg, Na, Fe, Mn, Zn, Cu, and B were determined by ICP-MS (Thermo Scientific iCAP Q, USA) following microwave-assisted acid digestion of 100 mg freeze-dried samples. The digestion employed a mixture of 65% HNO3 (2.5 mL), 3 M HCl (0.5 mL), and 50% HF (0.5 mL). Analytical accuracy was verified using certified reference material NCS ZC85006, with element recoveries within ±10% of certified values.

4.5. Polyphenolic Profile Assessment

Extraction of phenolic compounds from melon samples followed the method of Rodríguez-Pérez et al. (2013) [

41] with slight modifications. Briefly, 0.5 g of freeze-dried melon was extracted with 5 mL of methanol: water (80:20, v/v). The mixture was vortexed for 3 min, sonicated for 15 min, agitated on a rotary shaker for 10 min, and centrifuged at 5000 × g for 5 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was collected, and the residue re-extracted using the same procedure. Combined supernatants were filtered through a 0.2 μm nylon membrane and diluted with methanol containing 0.1% formic acid.

Chromatographic separation was performed on a UHPLC system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) using a Dionex Ultimate 3000 pump and a Kinetex 1.7 μm biphenyl column (100 × 2.1 mm, Phenomenex) at 25 °C. A 2 μL injection was run at 0.2 mL/min with a gradient of 0.1% formic acid in water (A) and methanol (B): 0 min, 5% B; 1.3 min, 30% B; 9.3 min, 100% B; 11.3 min, 100% B; 13.3 min, 5% B; 20 min, 5% B (Ignat et al. 2011) [48].

Mass spectrometry was conducted using a Q Exactive Orbitrap LC-MS/MS (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in Full MS mode with a resolution of 70,000 FWHM and mass tolerance of 5 ppm. Targeted analysis employed Parallel Reaction Monitoring (PRM) with optimized retention times and collision energies for each polyphenol. Method linearity was assessed between 5 and 120 mg/kg using six calibration points. Limits of detection (LOD) and quantification (LOQ) were established based on signal-to-noise ratios of chlorogenic acid and rutin standards via serial dilutions. Data analysis was performed using Xcalibur software (v. 3.1.66.19).

4.6. Experimental Design and Statistical Analysis

Data were subjected to two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 2022 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The experimental design included two factors: cultivation system (factor S), comparing open-field horizontal training versus greenhouse vertical training, and hybrid (factor H), consisting of four commercial melon genotypes. Main effects were assessed using Student’s t-test for factor A and one way ANOVA for factor C. When significant differences were detected (p < 0.05), means were compared using the Tukey–Kramer HSD post hoc test for factor C and the A × C interaction. A significance level of p < 0.05 was used throughout the analysis.