Submitted:

17 December 2025

Posted:

18 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

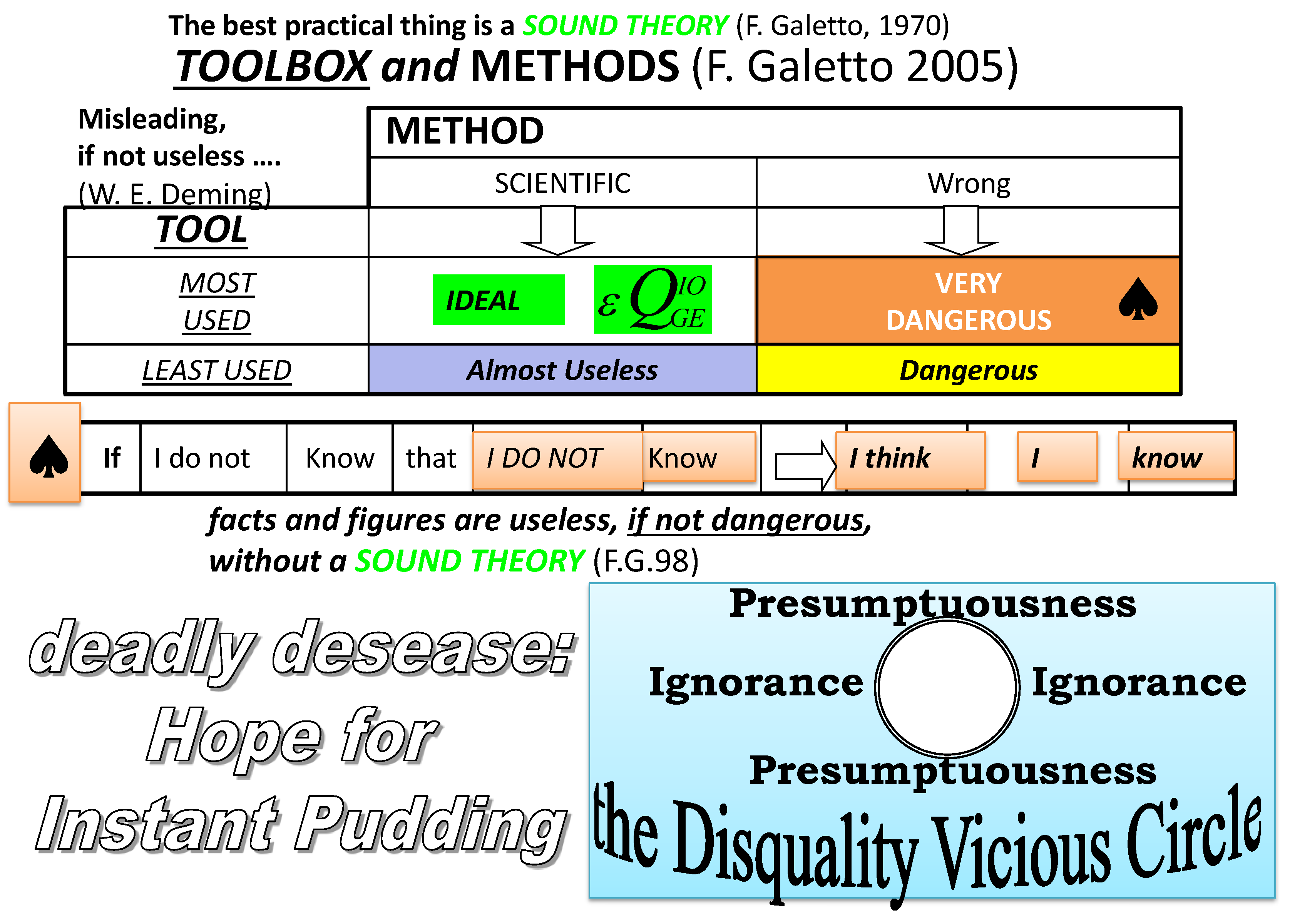

1. Introduction

- "… encoding a discrete verbal scale into numerical form … introduces properties that were not present in the original linguistic scale … eliminates the meaning of the collected data … Scalarisation, introducing in the scale … some “metrological properties” … may determine a “distortion” effect on information meaning. … with intuitable consequences."

- "… the analyst of the problem does directly influence the acceptance of results. Consequently, by attributing numbers to verbal information we move away from the original logic of the evaluator…. Proper scales for this purpose are linguistic scales ... because the concept of distance is not defined."

2. Materials and Methods

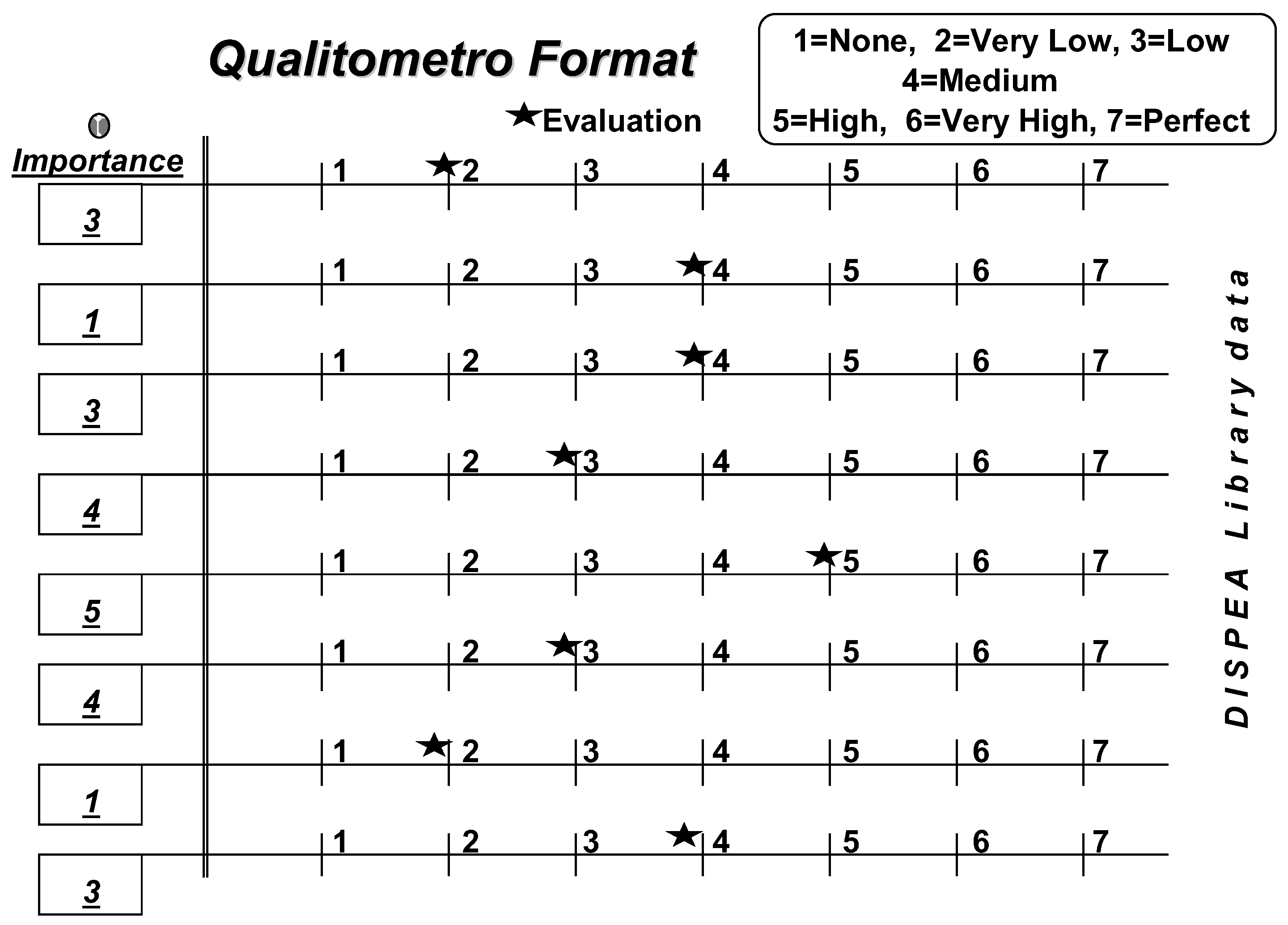

2.1. The Qualitometro I (Q I)

|

“Services and their quality are now the core of many investigative studies of managers and researchers. Many stimulating ideas and conceptual models have been proposed in such a way as to describe the mechanisms at the basis of delivered and received service. Developing this knowledge, there is now a strong need for proper service quality evaluation tools…. A great effort was made to specify and classify differences between the process characterizing a product and a service. Services are different in their intangibility, their limited standardization, and their contextual links, in place and time, between service production and delivery (impossibility to store), implying, usually, customer personal involvement. Finally, it is their heterogeneity resulting from the human factor that makes the service strongly affected by the conditions and the environment where it is delivered”. … “The central difference between products and services is the greater difficulty for the latter to ‘quantify’ them. This does not imply that for products, considered during their whole life cycle (not only in the product step), there is a simple solution for the analogous problem of global quality quantification”. ... “It is not easy for most services to define the qualitative elements to ‘observe’ which measurements are to be done and, no less, which test and checks to perform to control them”. “Many studies made efforts to realize how the customer perceives and evaluates the quality of received service, but to the problem’s complexity, the results represent only a promising beginning. Here, we offer a contribution to the growing discussion, suggesting an evaluation and on-line control of the gap between expected and perceived quality. In this context, on-line means evaluation during service delivery, remembering a term from control theory. “The main innovations of this method are the operative procedures for data collection and data elaboration”. “It is now common opinion among service operators that quality operators that quality comes from a stimulus of continuous comparison between expectations and perceptions. According to this criterion, Gronroos prepared a model founded on the assumption that the customer compares expected and the received service when evaluating quality… Some theoretical and empirical studies are offered as useful guidelines for service quality evaluation, control, and design”. “Suggestions by researchers found their base and consistency in some conceptual models for delivering service processes. Among them, the most famous and well know is that proposed by Parasuraman et al. If conceptual models are able to interpret service delivery steps on one hand to be used operatively on the other, they need to contain the values of the variables and parameters invoked, the evaluation of which is often other than immediate. To solve this problem, proper inquiry tools (questionnaires typically) able to collect customer evaluations are employed. The literature offers many tools to evaluate service quality. SERVQUAL and SERVPERF are two of the most well know and often used examples in the applications. Common feature of these methods are as followings: using questionnaires; the acknowledgement of the multidimensionality of quality (quality can be expressed as a set of attributes); considering expected and perceived quality or the latter only; ‘numerical’ interpretation of data collected in the questionnaires. The problem of the quantification service quality is solved by first stating the following: attribute affecting service delivery and their relative importance for the customer; objective and/or subjective measurable elements; ‘measuring systems’ adequate to evaluate attributes and variables; a proper model to define the link between variables and delivery process; procedures needed to monitor service delivery continuously; reference standards. People, mostly because of the diversity of each individual ‘reference system’ influence service evaluations substantially. |

|

“Nowadays, most of the questionnaires used to collect information on service quality use a point evaluation scale (1 to 7 or 1 to according to different versions) associated with adjectives to qualify a particular position. During data elaboration, scales are converted into numerical interval scale, and symbols are interpreted as numbers. Using these numbers, the statistical elaboration is then performed… …This conversion results in moving from an ordinal interval scale to a cardinal one”. “The scalarization of collected data presents two main problems: the first is in introducing through coding an arbitrary metric, resulting in a wrong interpretation of gathered data; the second is a hidden assumption for an identical scale interpretation by any interviewed individual and rigidity of this scale in time, especially for periodic service users. Scalarizationmay generate a ‘distortion’ effect, modifying the collected data partially or completely. A critical aspect of the question is that, usually, the entity of introduced distortions is not clear nor is the distance from the real value of the information given by customer”. “The Qualitometro method was created in order to evaluate and check on-line service quality”. |

|

“The analysis of information collected on one scale and elaborated on another one, with different properties, causes some interpretation problems”. “During data elaboration, scales are converted into numerical interval scales, and symbols are interpreted as numbers. Using these numbers, the statistical elaboration is then performed. Thus, for example, if the ends of a seven-point scales are the statements strongly disagree and strongly agree and we associate to these the numerical symbols 1 and 7 and symbols from 2 to 6 to the intermediate statements, we have carried out a conversion results in moving from an ordinal interval scale to a cardinal one” . “The scalarization of collected data presents two main problems: the first is in introducing through coding an arbitrary metric, resulting in a wrong interpretation of gathered data; the second is a hidden assumption for an identical scale interpretation by any interviewed individual and rigidity of this scale in time, especially for periodic service users. Scalarizationmay generate a ‘distortion’ effect, modifying the collected data partially or completely. A critical aspect of the question is that, usually, the entity of introduced distortions is not clear nor is the distance from the real value of the information given by customer”. “In other words, the original information, ‘arbitrary’ enriched or directed to simpler aggregation and elaboration, may be highly modified if compared with the one really expressed by customers, with intuitable consequences”. “Qualitometro allows two possibilities for data elaboration: |

|

2.2. The Qualitometro II (Q II)

| “Although numerization simplifies data elaboration for analysts, it eliminates the meaning of the collected data by the logic of evaluators/experts that delivered them. Scalarirization, introducing in the scale used to gather information some metrical properties higher than those really owned when supplied by the customer/evaluator, may then determine a distortion effect on information meaning. The critical side of the problem is that usually distortion is introduced and the shifts between arbitrary interpretation and customer opinion are not known ”. |

| «Another delicate question is the numerical coding for judgements expressed on interview questionnaires. … During data elaboration, scales are converted into numerical interval scales, and symbols are interpreted as numbers. … The scalarization of collected data presents two main problems. The first is in introducing through coding an arbitrary metric, resulting in a wrong interpretation of gathered data; the second is a hidden assumption for an identical scale "interpretation" by any interviewed individual and a rigidity of this scale in time, especially for periodic service users. Scalarization may generate "distortion" effect, modifying the collected data partially or completely. … In other words, the original information, "arbitrarily" enriched or directed to simpler aggregation and elaboration, may be highly modified if compared with the one really expressed by customers, with intuitable consequences.» |

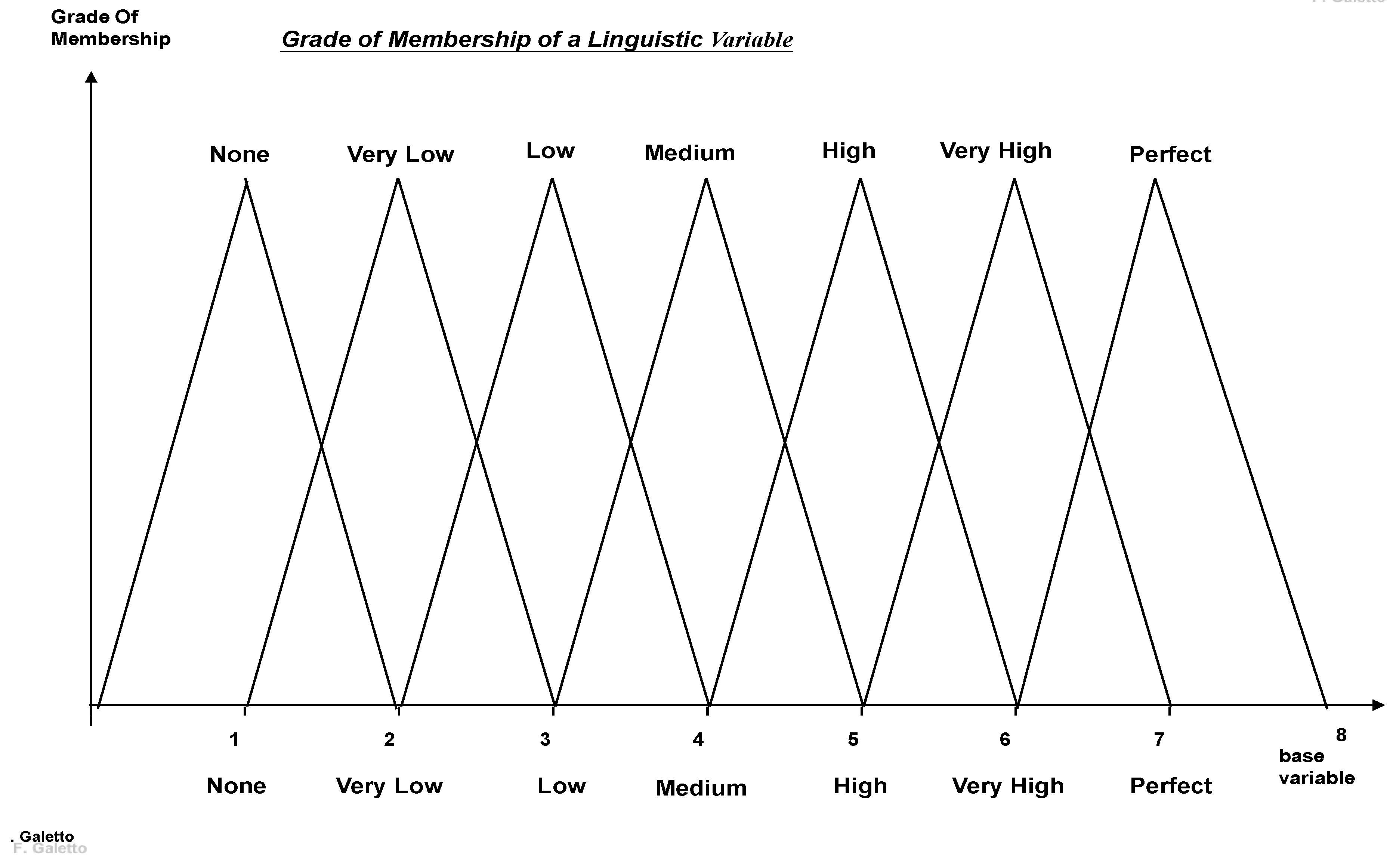

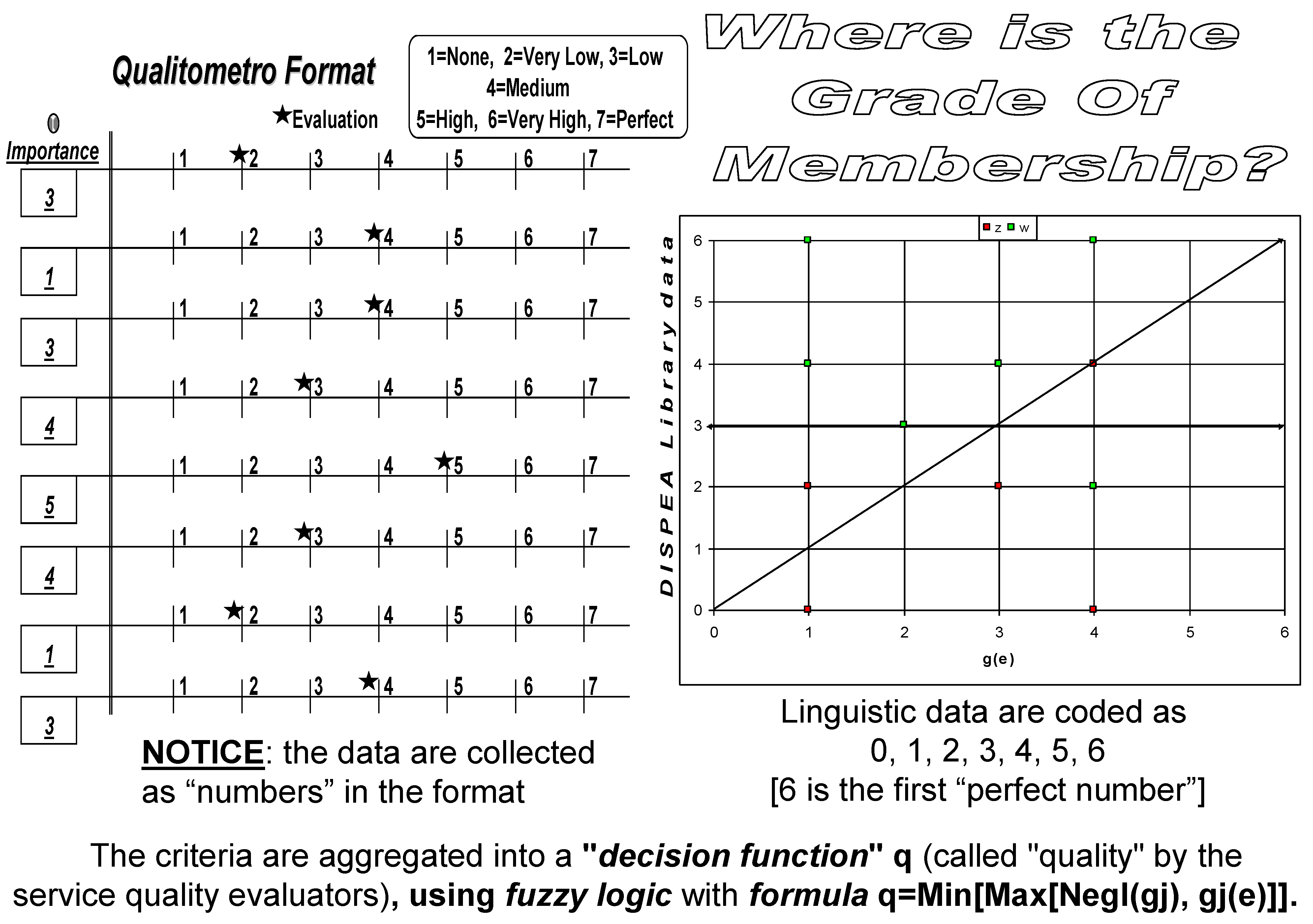

| «Ordered linguistic scales mainly differ from numeric or ratio scales because the concept of distance is not defined. The ordering is the main property attributed to such scales. For example, on a production line for fine liqueurs, a visual control of the corking and closing process might have the following possibilities: (a) 'reject', (b) 'poor quality', (c) 'medium quality', (d) 'good quality', (e) 'excellent quality'. The monitoring of production, using sampling control technique, is aimed at recognizing and, possibly, correcting … out-of-control conditions. In order to do this the five classifications listed above could be attributed to some numerical values, leading to the construction, for example, of standard X-R charts. Although the numerical conversion of the verbal information simplifies subsequent analysis, it also gives rise to two problems. The first is concerned with the validity of encoding a discrete verbal scale into a numerical form. This approach introduces properties that were not present in the original linguistic scale (for example, is it legitimate to assume that the difference between the 'reject' state and the 'poor quality' state is the same as that between the 'medium' and 'high quality'?) [notice: 'high quality' does not exist (in the "possibilities"!] Moreover, unlike scales used for physical measurements, ordered linguistic scales do not have either metrological reference standard or a measurement unit (QEG). The second problem is related to the absence of consistent criteria for the selection of the type of numerical conversion. It is obvious that changing the type of numerical encoding may determine a change in the obtained results. Introducing arbitrary weight for quality categories may condition substantially the way of interpreting the process evolution. For example, if we assign to each quality level for a five-level scale, the series of numbers: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, or the series: -9, -3, 0, 3, 9, we obtain two different results. In this sense the analyst of the problem does directly influence the acceptance of results. Consequently, by attributing numbers to verbal information we might effectively [sic] move away from the original logic of the evaluator. In this way any conclusion drawn from the analysis on 'equivalent' numerical data could be partially or wholly distorted. … The fuzzy operator that is used in the paper allows for this flexibility in the decision logic.» |

|

“For data elaboration, Qualitometro I allows two possibilities: Statistical data analysis according to the traditional approach (after data numerization), Central tendency and dispersion estimation without any numerical coding of collected information. Qualitometro I develops also a consistency test for gathered information. We now present and discuss a new proposal for data processing that enhances elaboration capabilities of Qualitometro I. This new procedure, named Qualitometro II, is able to manage information given by customers on linguistic scales, without any arbitrary and artificial conversion of collected data”. “Collecting and treating data by means of the Qualitometro II eases this process, providing a method for performing elaboration closer to the customers’ fuzzy thoughts” |

|

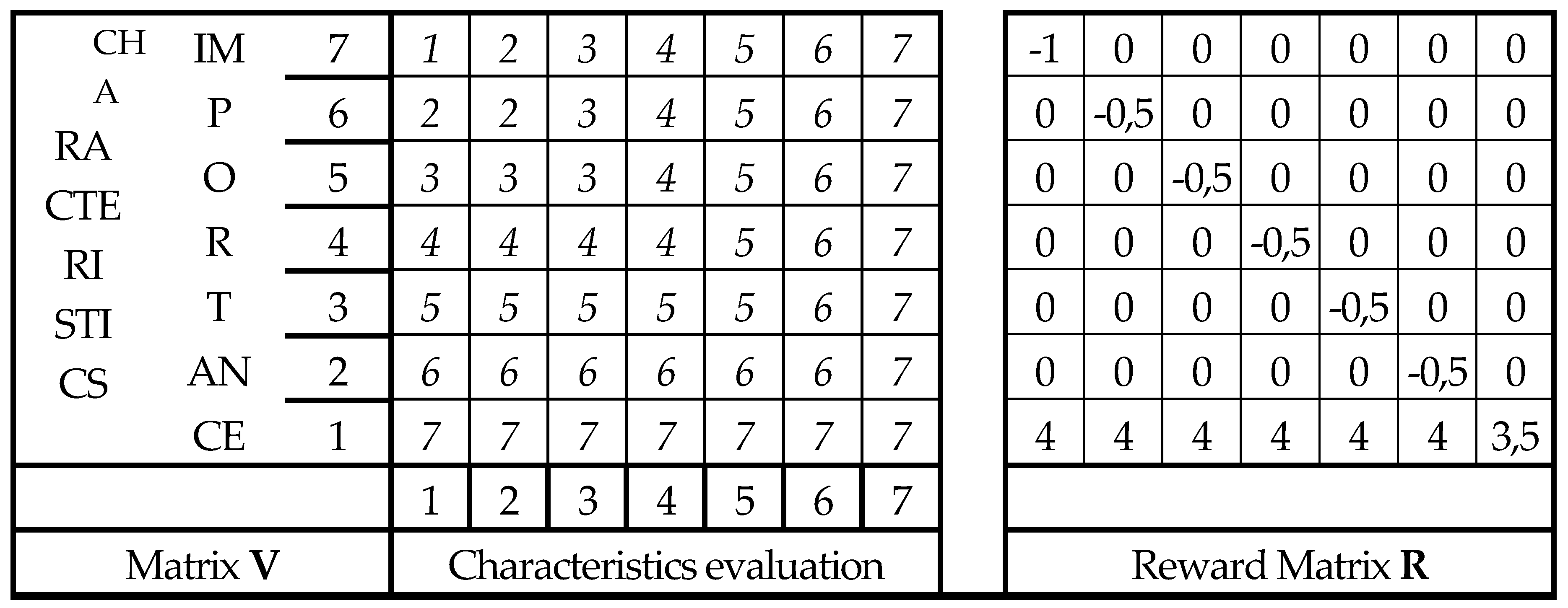

“The method proposed may be classified among the ME–MCDM (multiexpert–multiple criteria decision making) techniques”. “It is able to handle information expressed on linguistic scales without any artificial numeric scalarization. The use of linguistic scales introduces many constraints in the data elaboration process. As an example, we consider the calculation of the distance between two scale elements: this operation is fully defined on a numeric scale (with ratio or interval properties), but is not on an ordered linguistic scale. We assume the hypothesis of homogeneous interpretation of linguistic terms by each expert. In this manner, it is possible to ‘aggregate’ information coming from different evaluators”. “The authors propose interpreting any criterion as a fuzzy subset on the set of alternatives ai to be selected. If gj is the jth criterion (j=1, …, n), then the membership degree of an alternative ai to gj shows the degree to which the same alternative satisfies the criterion”. “The second idea given in the Bellman and Zadeh approach to how a DM (Decision Maker) aggregates evaluations expressed for each evaluation criterion”. “Particularly, they suggest the following relationship as a logical aggregating operation: where is the symbol of the logic operator “and” according to fuzzy logic interpretation”. For , (A is the set of alternatives) the decision function then becomes ... and following Yager (1993) (introducing the Importances) . “According to this model, global evaluation indicators for expected and perceived qualities given by the kth evaluator (k=1, …, s) becomes respectively: are the evaluations expressed by the kth evaluator on the jth criterion about expected (Qe) and perceived quality (Qp) respectively; the terms are the negations of the importances assigned to each evaluation criterion”. “It is worthwhile to emphasize that the provided aggregation does not perform any arbitrary scalarization of information given by evaluators on linguistic scales”. |

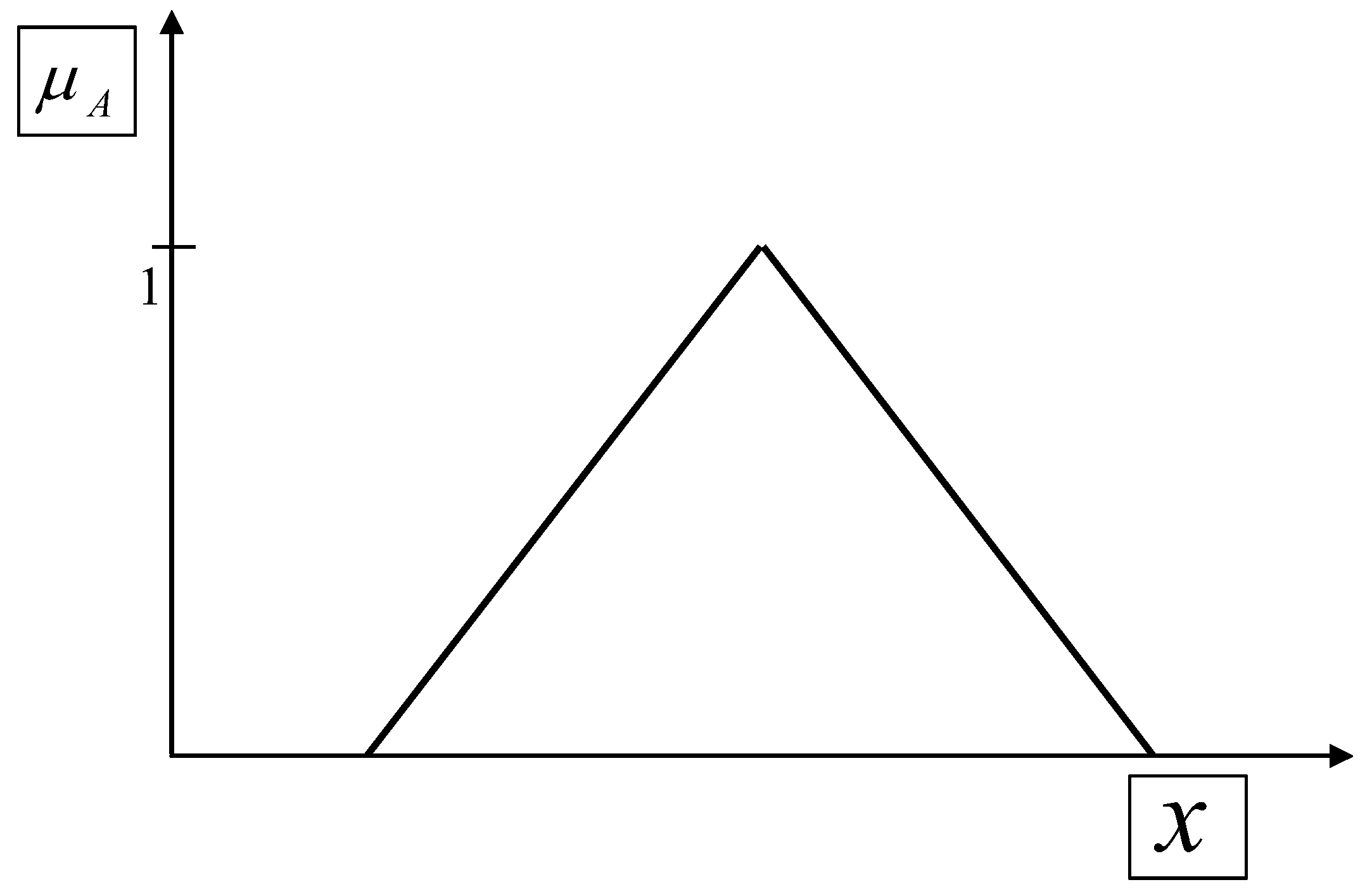

2.3. The “Fuzzy Sets” and the “Lattice Theory” for the Qualitometro II (Q II)

| "The main difference of this method [Qualitometro!], with respect to others inspired by fuzzy logic, is that it does not require explicit information on the membership function"! |

| Sequence | Axioms A | Axioms B |

| I | To every ordered pair (a, b) of elements a, b is assigned a unique element a∩b of L. |

To every ordered pair (a, b) of elements a, b is assigned a unique element a∪b of L. |

| II | (Commutative property of ∩) a∩b = b∩a | (Commutative property of ∪) a∪b = b∪a |

| III | (Associative property of ∩) a∩(b∩c) = (a∩b)∩c | (Associative property of ∪) a∪ (b∪c) = (a∪b) ∪c |

| IV | (Absorption property of ∩) a∩(a∪b) = a | (Absorption property of ∪) a∪(a∩b) = a |

- Structural identity: Isomorphic lattices are indistinguishable from a structural point of view. One is essentially a copy of the other, just with different labels for its elements.

- Bijective map: An isomorphism is a bijective function, meaning every element in the first lattice corresponds to exactly one element in the second, and vice versa.

- Preservation of operations: The most crucial property is that the function preserves the lattice operations. For any two elements a and in the first lattice (), and their corresponding elements in the second lattice () denoted as and , we have:

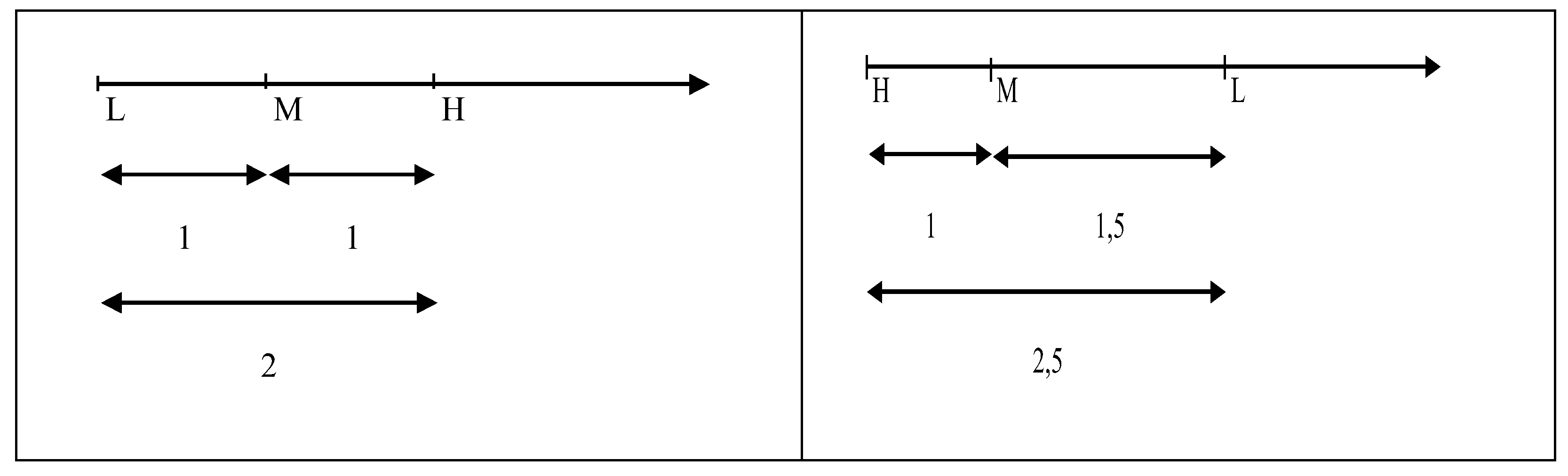

2.4. Various Few Cases of “Scalarisation” for the Qualitometro (Q I and Q II)

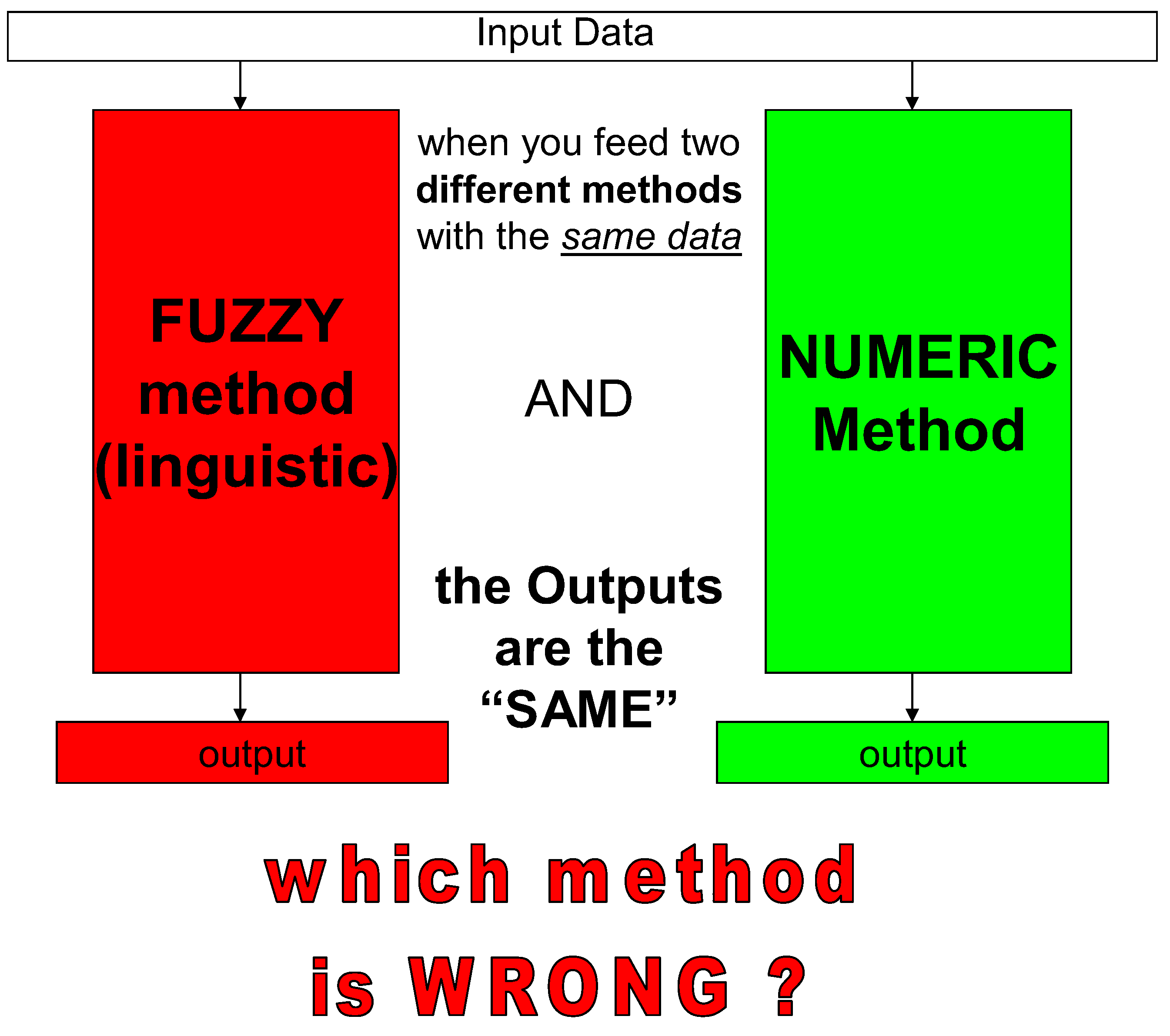

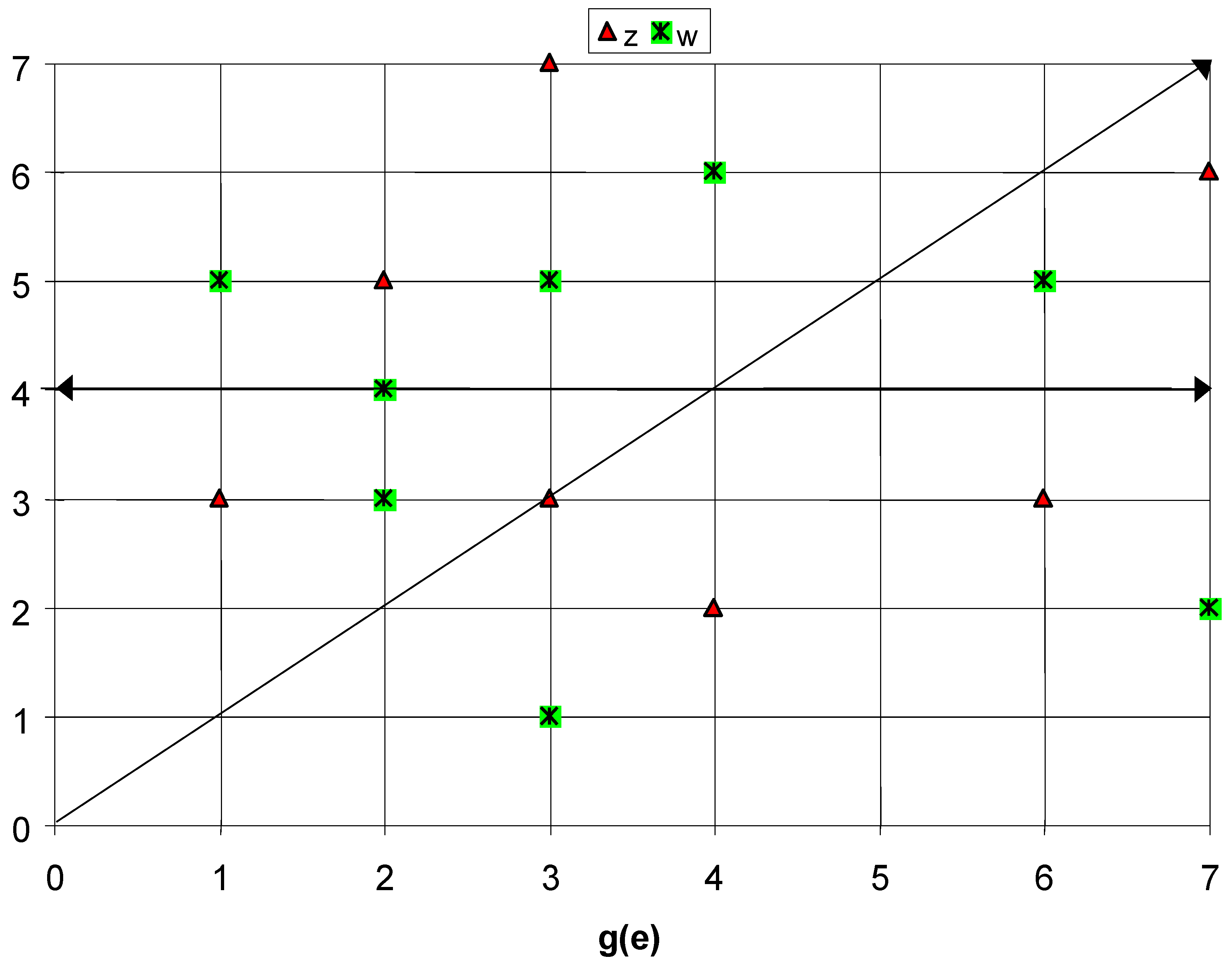

- IF the PR says "Galetto did not provide the proof of the falseness of Qualitometro and Yager methods" HE is wrong: F.G. used numbers, distance, and no GoM, and he found the "SAME"=EQUIVALENT results [see fig. 4, 5]

- IF the PR says "Galetto did not provide the right formulae" HE is wrong: F.G., up to now, gave two methods, one geometric, another algebraic (F.G. can provide more than 20; some are given later).

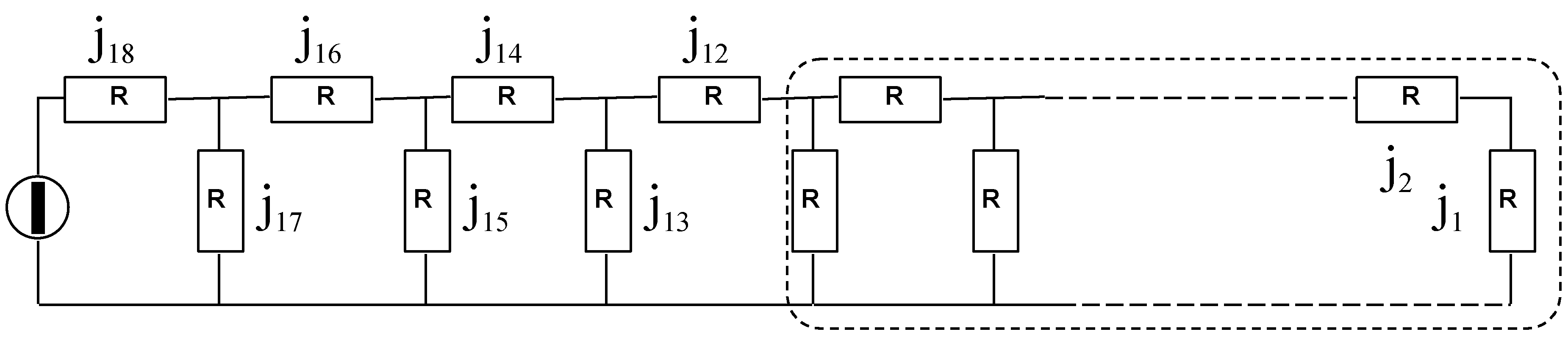

- I)

- For evaluations, we associate the 1st of the “7-shot” s1 to the power [named x1] connected to the current j12, and so on till the last the “7-shot” s7 to the power [x7] connected to the current j18,

- II)

- For importances, we associate the 1st of the “7-shot” s1 to the power [named y1] connected to the current j18, and so on till the last the “7-shot” s7 to the power [y7] connected to the current j12.

2.5. The Qualitometro III (Q III)

| “The paper presents a new method for statistical process control when ordinal variables are involved. This is the case of a quality characteristic evaluated by on ordinal scale. The method allows a statistical analysis without exploiting an arbitrary numerical conversion of scale levels and without using the traditional sample synthesis operators (sample mean and variance). It consist of different approach based on the use of a new sample scale obtained by ordering the original variable sample space according to some specific ‘dominance criteria’ fixed on the basis of the monitored process characteristics. Samples are directly reported on the chart and no distributional shape is assumed for the population (universe) of evaluations”. |

|

“Many quality characteristics are evaluated on linguistic or ordinal scales… …The levels of this scale are terms such as ‘good’, ‘bad’, ‘medium’, etc…, which can be ordered according to the specific meaning of the quality characteristic at hand. Ordered linguistic scales mainly differ from numerical or cardinal scales because the concept of distance is not defined. The ordered is the main property associated to such scales”. Two problems arise with scalarization: (1) “the first is concerned with the validity of encoding a discrete verbal scale into a numerical form. The numerical codification implies fixing the distances among scales levels, thus converting the ordinal scale into a cardinal one”, (2) the second is related to the absence of consistent criteria for the selection of the type of numerical conversion. It is obvious that changing the numerical encoding may determine a change in the obtained results. In this way the analyst directly influences the acceptance of results. Therefore, any conclusions drawn from the analysis on ‘equivalent’ numerical data could be partially or wholly distorted”. |

| Reject (R) | Poor quality (P) | Medium quality (M) | Good quality (G) | Excellent quality (E) | Mean | |

| 2 corks | 5 corks | 9 corks | 7 corks | 7 corks | ||

| code | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 3.4 (M_G) |

| code | 1 | 3 | 9 | 27 | 81 | 28.5 (G_E) |

| code | -9 | -3 | 0 | 3 | 9 | 1.7 (M_G) |

|

The first mean is 3.4; “Hence, the sample mean seems to be between ‘medium quality’ and ‘good quality’. The adopted numerical conversion is based on the implicit assumption that all scale levels are equispaced. However, we are not sure that the evaluator perceives the subsequent levels of the scales as equispaced, nor even if s/he has been preliminary trained”. The second mean is 28.5;“The sample mean seems to be between ‘good quality’ and ‘excellent quality’. We cannot say which is the right value of the sample mean at hand because an ‘exact’ codification does not exist... The third mean is 1.7 (=3.4/2); that sample mean is between‘medium quality’ and ‘good quality’. …This example points out that a simple codification of scale levels could result in a misrepresentation of the original gathered information. A correct approach should be based on the usage of the properties of ordinal scales themselves. The main aim of the present paper is to propose a new method for on-line process control of a quality characteristic evaluates on an ordinal scale, without exploiting an artificial conversion of scale levels… …The new proposal does not consider the synthesis operators. It allows on-line monitoring based on a new process sample scale obtained by ordering the original variable sample space according to some specific ‘dominance criteria’. Samples are directly reported on the chart and no distributional shape assumed for the population (universe) of evaluations”. |

|

“The sample space of a generic ordinal quality characteristic is not ordered in nature”. “A dominance criterion allows attributing a position in the ordered sample space to each sample. If sample B dominates sample A, the sample A has a lower position in the ordering. For each pair samples a dominance criterion states a dominance or an equivalence relationship. If the resolution of the dominance criterion is high, the dimension of equivalence classes is very small. The most resolving criterion is the one assigning a different position to each ordered sample. This is the same as saying that every equivalence class has only one element ”. |

|

“The first classical answer to this question is the assignment of a specific numerical value to each level of the evaluation scale. A possible codification could be the following: ‘Low’ = 1; ‘Medium’ = 2; ‘High’ = 3”. “The codification allows building traditional X-R control charts. However, this procedure has three main contraindications. First, each conversion is arbitrary and different codifications can lead to different results. Second, codification introduces the concept of distance among scale levels, which is not originally defined. Third, since the original distribution of evaluations is discrete with a very small number of levels, the central limit theorem hardly applies to this context.A second analysis of data inTable 2 (our Table 5.) can be executed by method suggested by Franceschini e Romano. This methodology is based on the use of operators that do not require the numerical codification of ordinal scale levels. The adopted location measure is the ordered weighted average (OWA) emulator of arithmetic mean, firstly introduced by Yager and Filev”. “The OWA operator can take values only in the set of levels of the original ordinal scale. The related control chart is built following a methodology very similar to the traditional chart for mean values. The adopted dispersion measure is the range of ranks rs, defined as the total number of levels contained between the maximum and the minimum value of a sample (the rank r(q) is the sequential integer number of a generic level q on a linguistic scale): . For the range of ranks too, the related control chart is constructed using the traditionalapproach. Figures V.3 andV.4 show the control charts for the OWA and the range of ranks of data reported in Table II (table 5.) “Although this methodology does not exploit the device of codification, the dynamics of the charts are poor and little information can be extracted about the process (on the contrary, in Qualitometro II, they said that is was fantastic.). Moreover, the method is not free from distributional assumptions. The dispersion measure assumes that the scale ranks do not depend on the position of level of the ordinal variable. |

| In this paper we propose a third way of analyzing data reported in Table II (ourTable 5.). It exploits the only properties of ordinal scales, avoiding the synthesis of information contained in the sample. No distributional assumptions are required about the population (universe) of evaluations. As traditional control charts, this new methodology is based on the use of two different charts: one for ordered sample values, and the other for ordered sample ranges… As a consequence, they can be built and used separately. However, for an exhaustive analysis, a conjoint approach is highly recommended”. “The new proposal is based on the ordering of the sample space of the ordinal quality characteristic”. |

|

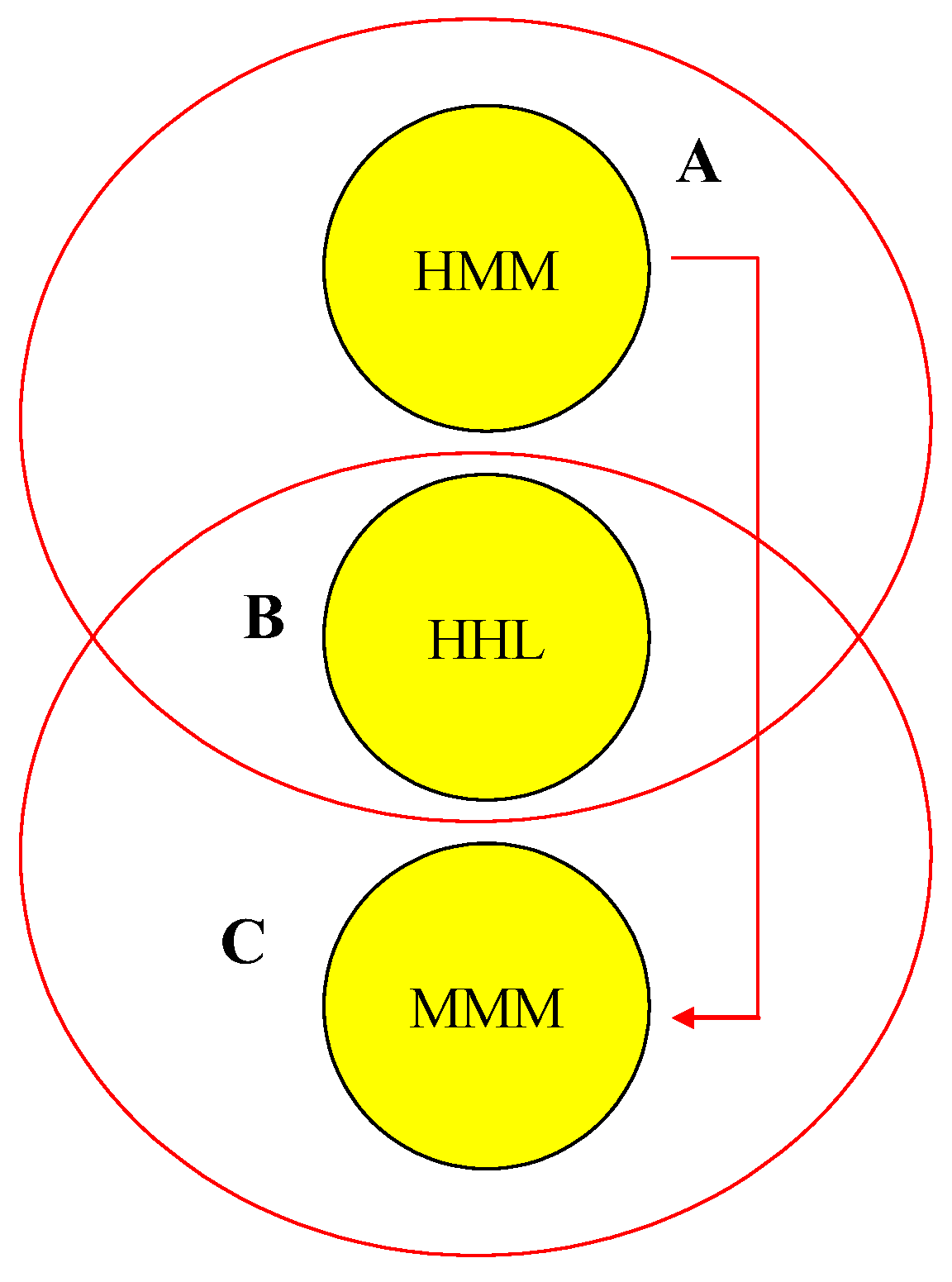

“To compare and order these samples we introduce a rule called ‘dominance criterion’, defined, case by case, on the basis of the characteristics of the monitored process. In accordance with this rule, if sample A dominates sample B, then sample A is preferred to sample B. As a result we can define a new ordinal scale whose levels are the positions of the samples in the ordered sample space. If there is no dominance relationship between sample A and sample B, they belong to the same ‘equivalence class’. The choice of the dominance criterion influences the resolution of the scale (i.e. the number of levels of the ordered sample space) and also the order of levels. For each process one or more dominance criterion may be established on the basic of the specific application”. “We begin analyzing the Pareto-dominance criterion. We state that sample X Pareto-dominates sample Y if all elements in Y do not exceed the corresponding elements in X, and at least one element in X exceeds sponding one in Y. This situation is formally denothe correted by . In case samples X and Y belong to the same equivalence class, i.e. no dominance relationship can be defined between them, we use the following notation: X≈Y”. “As we can see from figure, it is not possible to assign a well-defined position to samples A, B and C, because their intersection is not empty. The problem can be solved by introducing the concept of ‘semi-equivalence class’. A semi equivalence class is composed of equivalence classes whose intersections are not empty… |

|

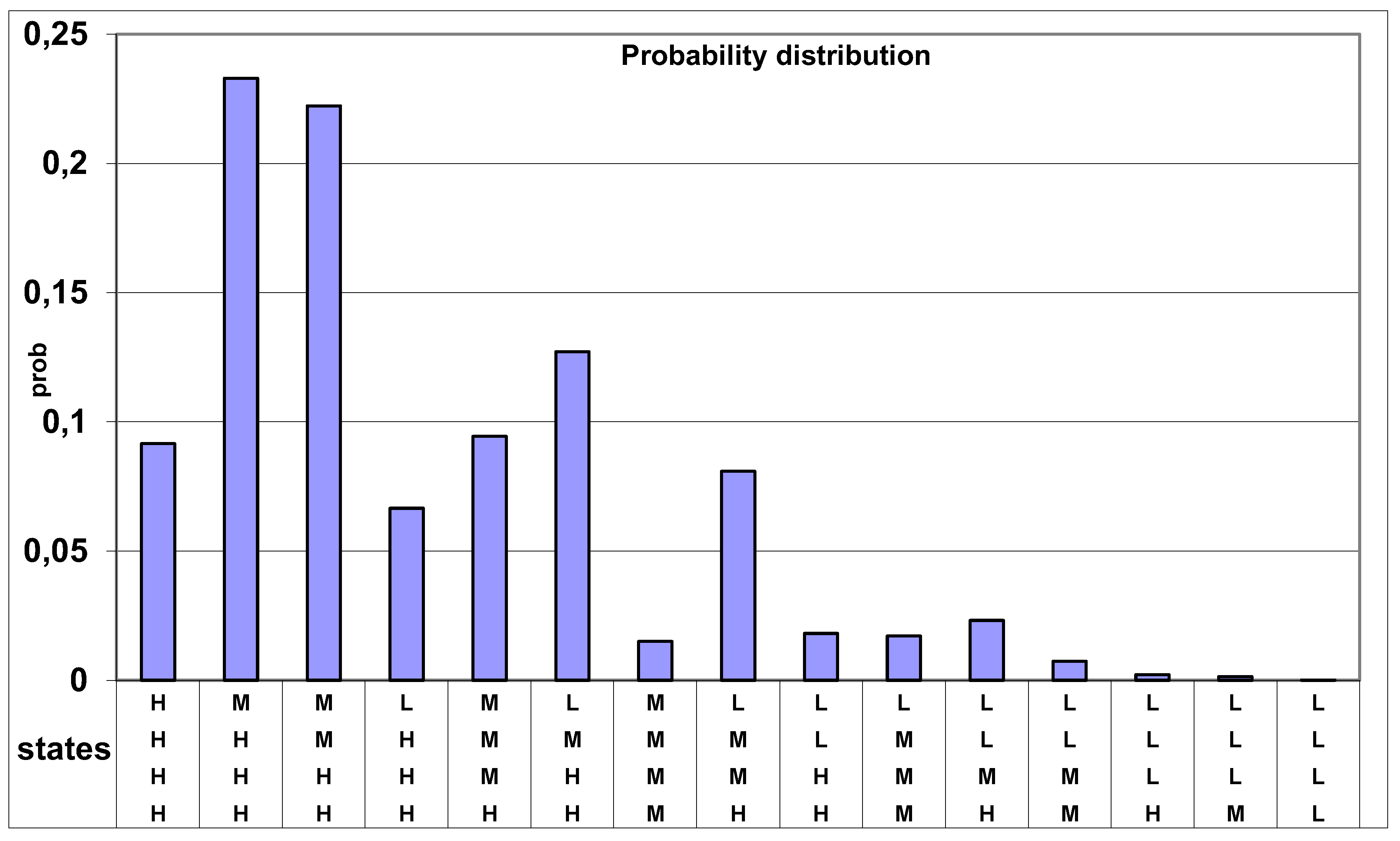

“As we can see from figure, it is not possible to assign a well-defined position to samples A, B and C, because their intersection is not empty. The problem can be solved by introducing the concept of ‘semi-equivalence class’. A semi equivalence class is composed of equivalence classes whose intersections are not empty… In general, Pareto dominance criterion gives a ‘poor’ ordering for the sample space of an ordinal quality characteristic. A more discerning criterion is the ‘rank dominance criterion’. Its introduction requires the definition of the concept of ‘optimal sample’. A sample is said to be optimal if all elements assume the highest level of an ordinal scale. In our example the optimal sample is HHH. For each sample we define a rank index which quantifies its positioning with regard to the optimal sample. The index is built in by adding up the numbers of scale levels contained between each sample value and the corresponding value of the optimal sample”. Consider the sample D={H, M, L}: its rank index is 3. “A high value of rank index corresponds to a ‘bad’ sample. All samples that are characterized by the same index belong to the same equivalence class. Therefore their positioning with respect to the optimal sample can be equivalently identified by the corresponding equivalence class. The number of elements of the new ordinal sample scale depends on the sample size and on the number of levels of the evaluation scale… Table V.6 (first column) reports all possible ordered samples of size n = 4, on an evaluation scale with t=3 levels. For each sample, the corresponding position on the resulting scales is reported (third column). The greater the position number, the higher the sample evaluation. A greater resolution, i.e. a larger number of levels, on the ordinal sample scale can be obtained by integrating the rank dominance criterion with the dispersion dominance criterion. This criterion allows distinguishing among samples belonging to the same equivalence class by analyzing sample dispersion. A lower position is associated with a greater dispersion. The fourth column of table V.6 reports the position of each sample in the new ordered sample space after the sequential application of the rank and the dispersion dominance criteria. As we can see, each ordered sample is associated with a different position; this is the greatest possible resolution”. |

| Sample Space | Rank Index | Position in the ordered sample space (equivalent class) [rank dominance criterion] |

Position in the ordered sample space (equivalent class) [rank & dispersion dominance criterion] |

| LLLL | 8 | 1st | 1st |

| MLLL | 7 | 2nd | 2nd |

| MMLL | 6 | 3rd | 4th |

| MMML | 5 | 4th | 6th |

| MMMM | 4 | 5th | 9th |

| HLLL | 6 | 3rd | 3rd |

| HMLL | 5 | 4th | 5th |

| HMML | 4 | 5th | 8th |

| HMMM | 3 | 6th | 11th |

| HHLL | 4 | 5th | 7th |

| HHML | 3 | 6th | 10th |

| HHMM | 2 | 7th | 13th |

| HHHL | 2 | 7th | 12th |

| HHHM | 1 | 8th | 14th |

| HHHH | 0 | 9th | 15th |

| Sample Space | Rank Index | Position in the ordered sample space (equivalent class) [rank dominance criterion] |

Position in the ordered sample space (equivalent class) [rank & dispersion dominance criterion] |

| LLL | 6 | 1st | 1st |

| MLL | 5 | 2nd | 2nd |

| MML | 4 | 3rd | 4th |

| MMM | 3 | 4th | 6th |

| HHH | 0 | 7th | 10th |

| HLL | 4 | 3rd | 3rd |

| HML | 3 | 4th | 5th |

| HMM | 2 | 5th | 8th |

| HHM | 1 | 6th | 9th |

| HHL | 2 | 5th | 7th |

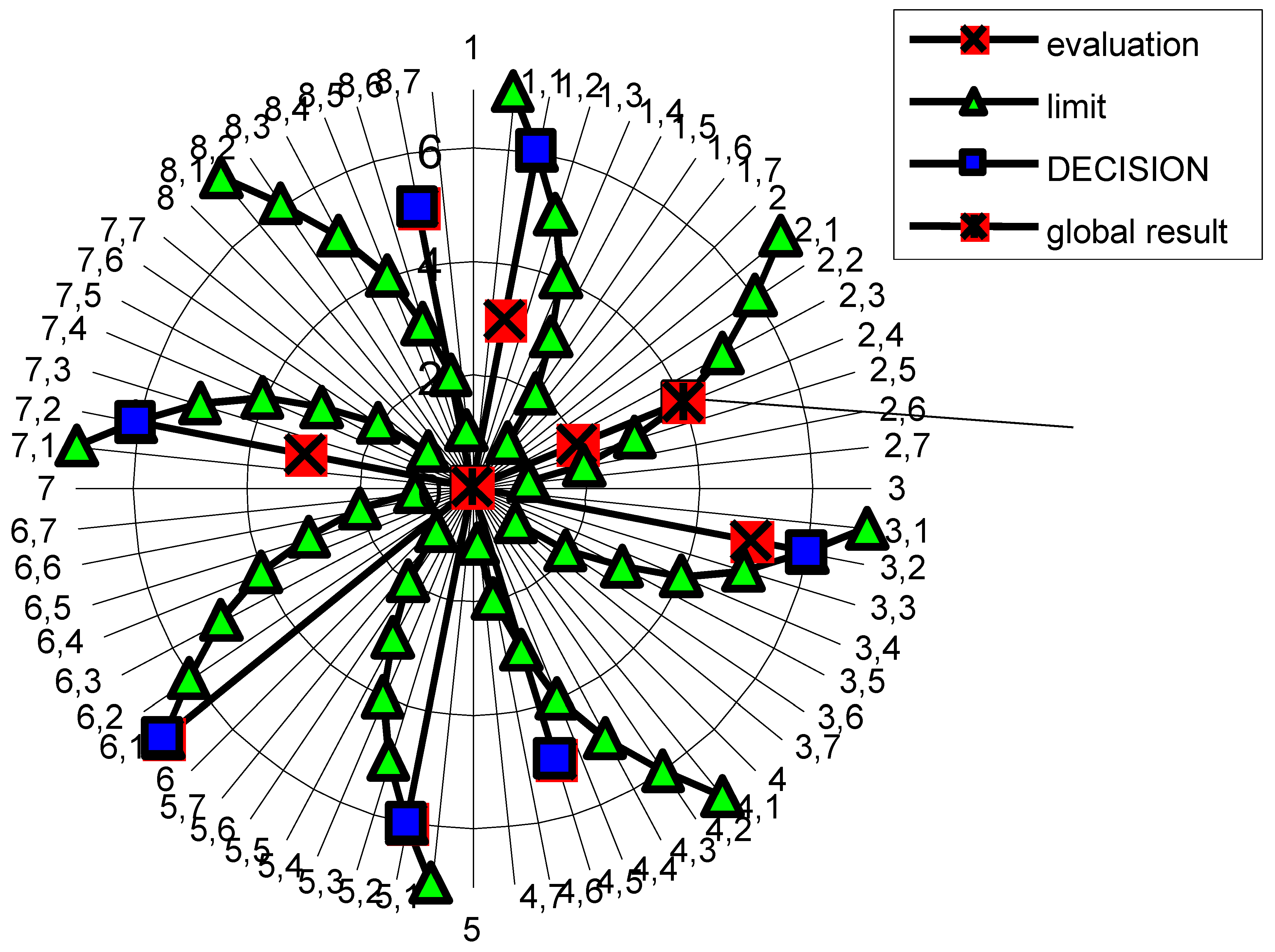

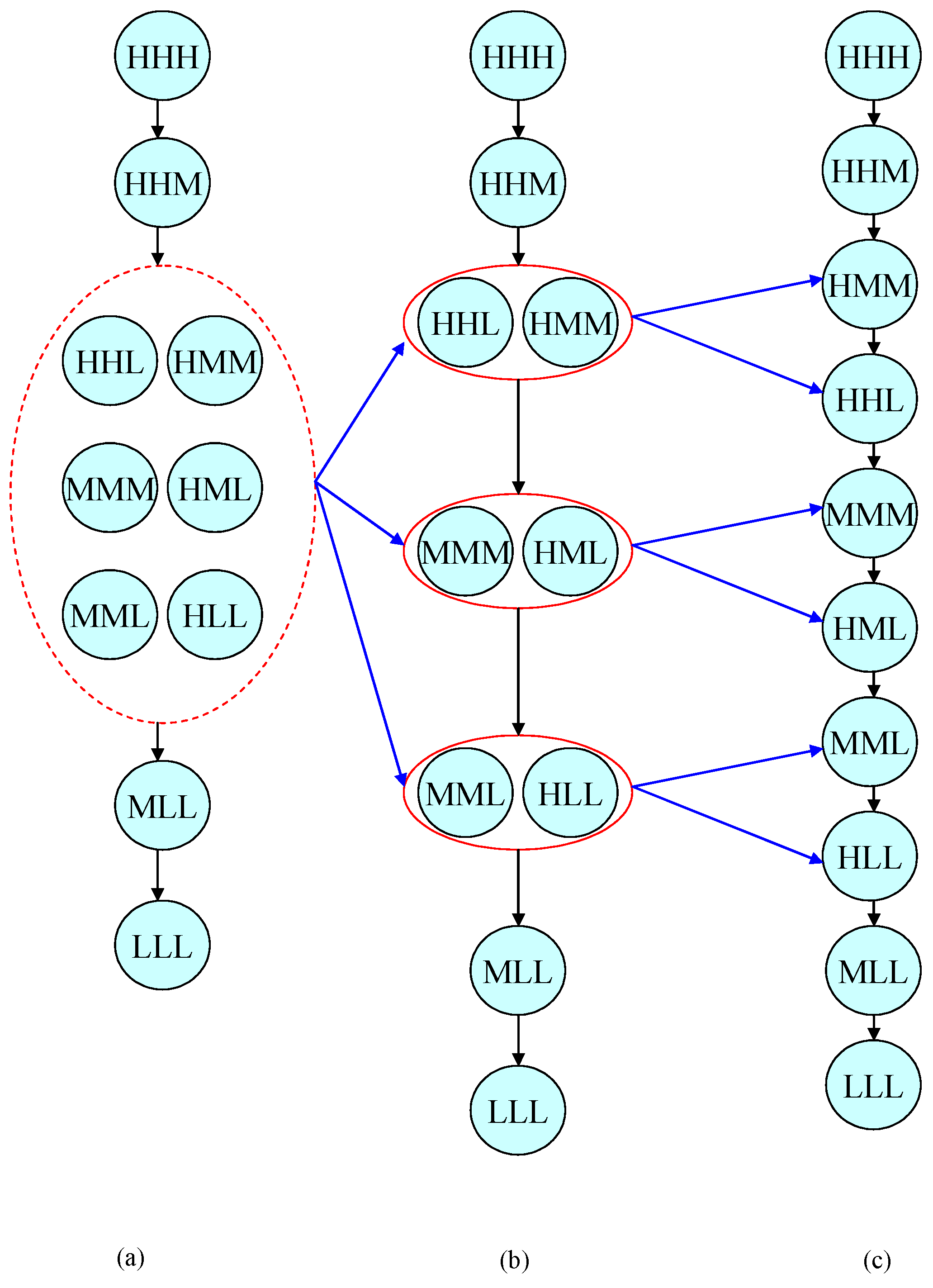

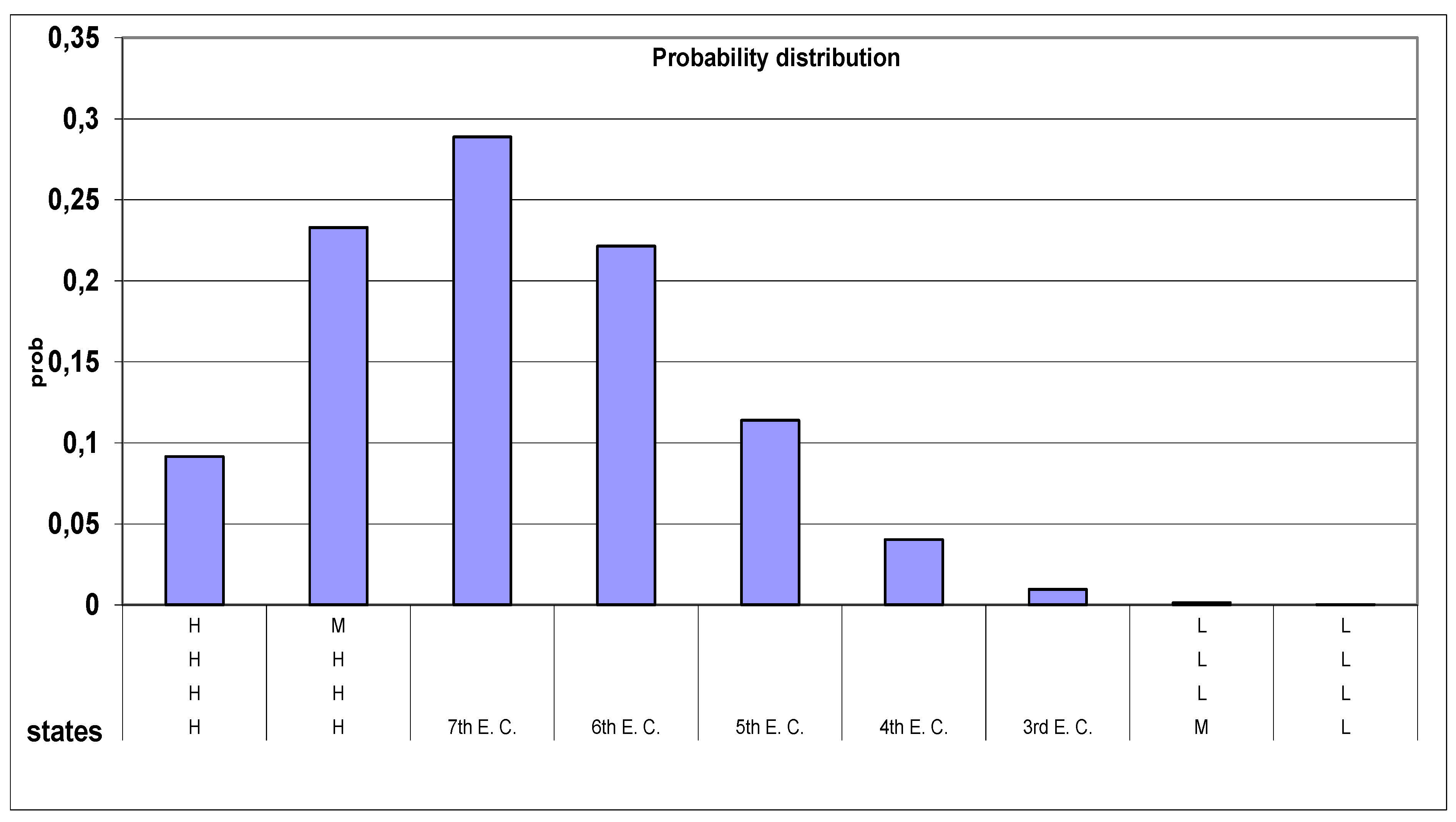

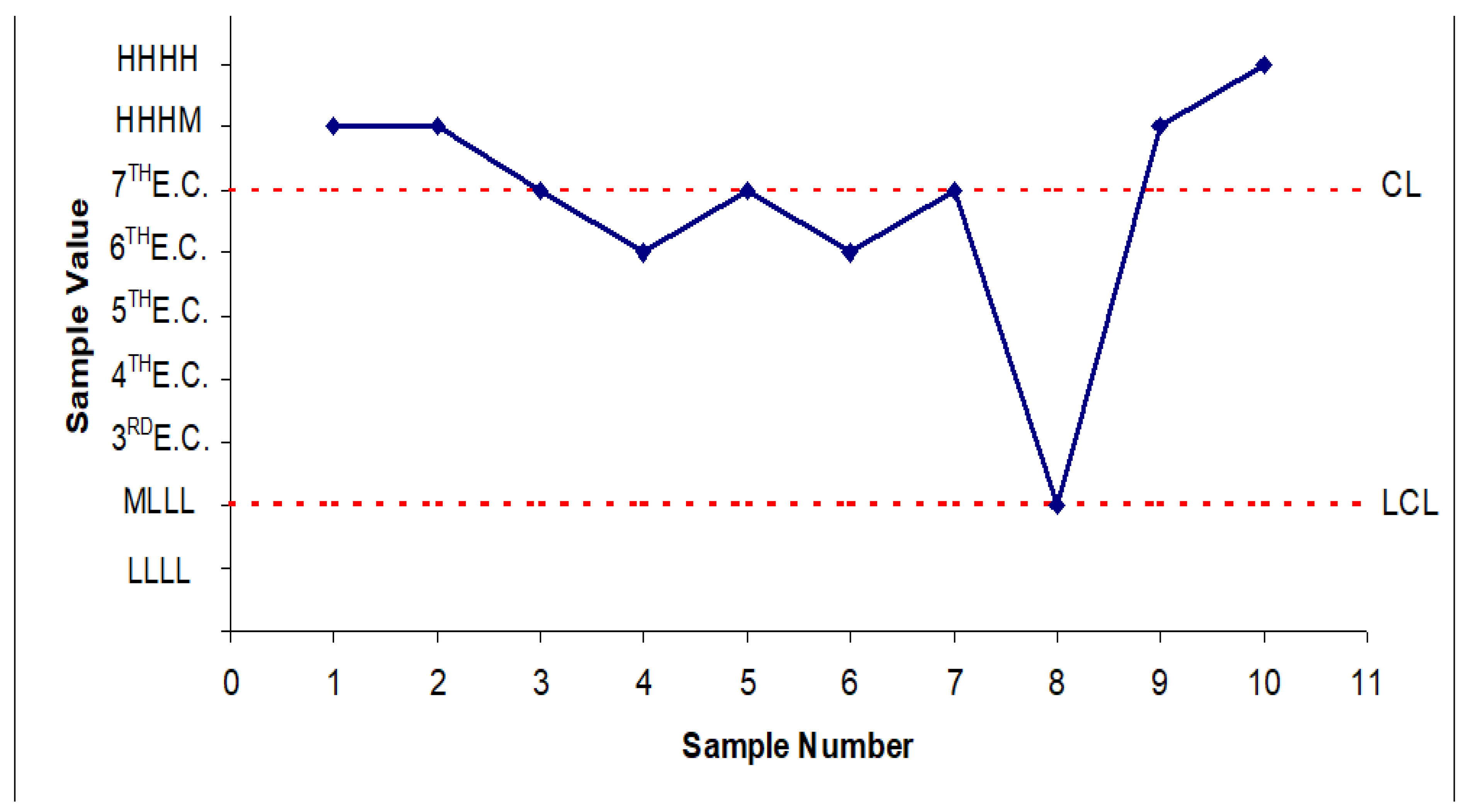

| “A vertical arrow represents a dominance relationship. A continuous ellipse represents an equivalence class, while a dashed ellipse represents a semi-equivalence class. The figures (a), (b) e (c) report respectively the results of the application of the Pareto-dominance, the rank dominance and the rank plus dispersion dominance criteria. The transverse arrows describe how each equivalence or semi-equivalence class is split by the application of a more discerning dominance criterion. The resolution of the ordered sample space varies with the considered dominance criterion. In accordance with a specific dominance criterion, sample charts report the positions of samples in the ordered sample space on the vertical axis. Given the particular meaning of sample charts, only the lower control limit (LCL) is defined. The central line (CL) represents the median of sample distribution. A set of initial samples is considered to determine the sample empirical frequency distribution. This empirical distribution (so a distribution exists!!!) is then used to calculate the lower control limit for a given type I error. Control limits are determined by empirical estimates of probabilities based on observed frequencies in a set of initial samples. Therefore, because the probabilities are estimated, the estimates contain errors, which could become significant for very small probabilities. A large initial set of samples or an alternative approach based on bootstrap techniques are needed to estimate the limits with a more reasonable accuracy”. |

3. Results

3.1. Results on the Qualitometro III (Q III)

- ⇒

- "The numerical codification implies fixing the distances among scales levels, thus converting the ordinal scale into a cardinal one; the second is related to the absence of consistent criteria for the selection of the type of numerical conversion [are consistent the "dominance criteria" of the new three "tenors"?????]. It is obvious that changing the numerical encoding [as the "dominance criteria" of the new three "tenors"] may determine a change in the obtained results. In this way the analyst directly influences the acceptance of results.

- ⇒

- Therefore, any conclusions drawn from the analysis on ‘equivalent’ numerical [as the "dominance criteria" of the new three "tenors"] data could be partially or wholly distorted "

- ⇒

- “By the adopted criteria, the example presents some significant differences compared with the approach based on the numeric codification of levels. Using different criteria the difference between the proposed approach and the traditional one becomes more evident, such as for the ordinal sample charts. Furthermore, ordinal range charts also allow a process positioning analysis. A good quality process will present a concentration of samples at the lowest positions of the ordinal range space scale”.

- ⇒

- “The paper presents two new control charts for the process control of quality characteristics evaluated on an ordinal scale, without exploiting an artificial conversion of scale levels. The basic concept of the charts is the ordering of the sample space of the quality characteristic at hand.

- ⇒

- Charts do not suffer from the poor resolution shown by other linguistic charts [while BEFORE for Qualitometro II they said, some years before, that they were fantastic!], where the original evaluation scale is used to evaluate samples”.

- ⇒

- “No distributional shape is assumed for the population (universe) of evaluations”. [a distribution exists and it is the multinomial!]

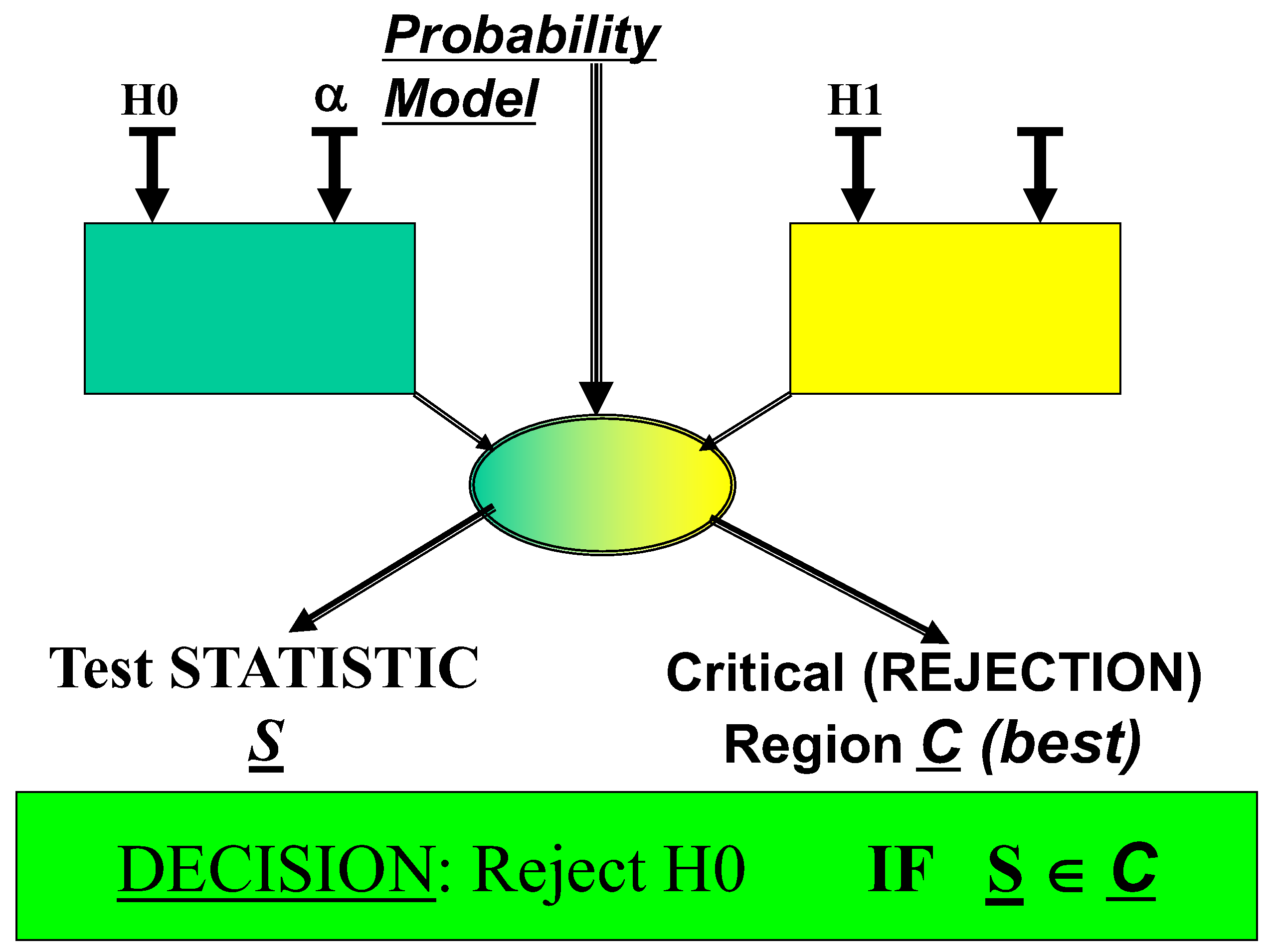

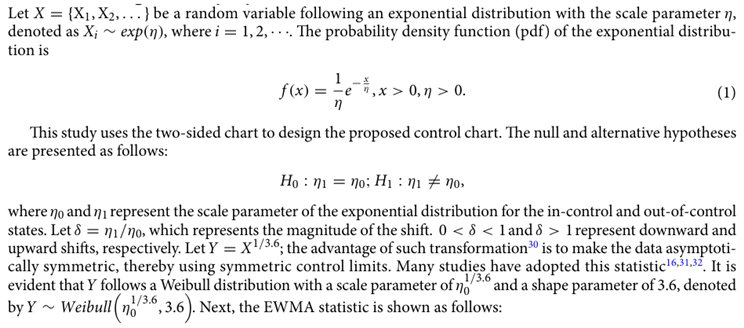

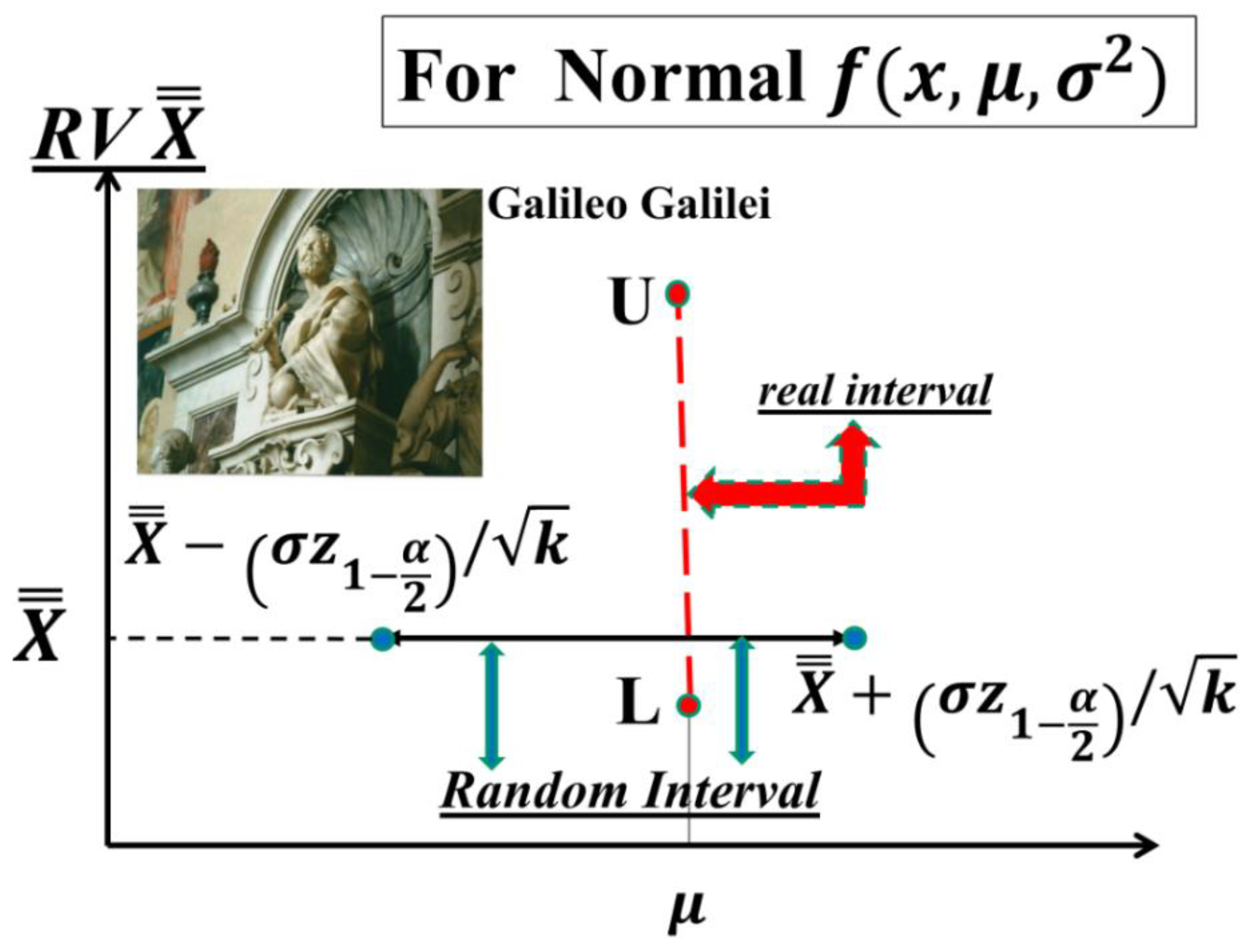

3.2. Control Charts for “for Monitoring the Exponential Process with Estimated Parameter”

|

Control charts have been used to monitor product manufacturing processes for decades. The exponential distribution is commonly used to fit data in research related to healthcare and product lifetime. This study proposes an exponentially weighted moving average control chart with a variable sampling interval scheme to monitor the exponential process, denoted as a VSIEWMA-exp chart. The performance measures are investigated using the Markov chain method. In addition, an algorithm to obtain the optimal parameters of the model is proposed. We compared the proposed control chart with other competitors, and the results showed that our proposed method outperformed other competitors. Finally, an illustrative example with the data concerning urinary tract infections is presented. Keywords Exponential process, Estimated parameter, Exponentially weighted moving average, Variable sampling interval, Markov chain method, Optimization algorithm design |

|

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- R. E. Bellman und L. A. Zudeh, Decision-Making in a Fuzzy Environment, Report No ERL-69-8, NASA.

- Zadeh, I. (1976) The concept of linguistic variable and application to approximate reasoning, Inf. Science.

- Belmann, R., Zadeh, I. (unknown) Decision making in a fuzzy environment, NASA CR-1594.

- Yager, R. (1981) New methodology for ordinal decision based on fuzzy sets, Decision Sciences, 12, 589-600.

- Yager, R.R. Non-numeric multi-criteria multi-person decision making. Group Decis. Negot. 1993, 2, 81–93. [CrossRef]

- Yager, R., Filev, D. P. (1994). Essentials of Fuzzy Modeling and Control. New York, USA: J. Wiley.

- Zadeh, L. Polak, E. (1969) System Theory, McGraw-Hill.

- Journals: Quality and Reliability Engineering International, Quality Engineering,, Reliability Engineering and System Safety, IIE Transactions, Quality Technology and Quantitative Management, Quality & Quantity, J. of Applied Statistics, J. of Quality Technology, J. of Statistical Planning and Inference, J. of Statistical Computation and Simulation, International J. of Production Research, J. of the American Statistical Association, International J. for Quality Research, J. of Quality Technology, J. of Statistical Theory and Practice, J. of Statistical Theory and Applications, J. of Applied Probability and Statistics, International J. of Advanced Manufacturing Technology, J. of Systems Science and Information, European J. of Operational Research, J. of Nonparametric Statistics, J, of the Japanese Society of Computational Statistics, Communications in Statistics - Simulation and Computation, Statistics and Probability Letters, Communications in Statistics - Theory and Methods, Computational Statistics, Computational Statistics & Data Analysis, www.nature.com/scientificreports.

- Bass, F.M. A new product growth for model consumer durables. Manag. Sci. 1969, 15, 215–227. [CrossRef]

- Bellman, R. (1970) Introduction to Matrix Analysis, 2nd ed., McGraw-Hill.

- Belz, M. Statistical Methods in the Process Industry: McMillan; 1973.

- Casella, Berger, Statistical Inference, 2nd edition: Duxbury Advanced Series; 2002.

- Cramer, H. Mathematical Methods of Statistics: Princeton University Press; 1961.

- Deming W. E., Out of the Crisis, Cambridge University Press; 1986.

- Propst, A.L.; Deming, W.E. The new economics for industry, government, education. Technometrics 1996, 38, 294. [CrossRef]

- Dore, P., (1962) Introduzione al Calcolo delle Probabilità e alle sue applicazioni ingegneristiche, Casa Editrice Pàtron, Bologna.

- Cramer, H., (1961) Mathematical Methods of Statistics, Princeton University Press.

- Ziegel, E.R.; Juran, J.M.; Gryna, F.M. Quality Control Handbook, 4th. Technometrics 1990, 32, 97. [CrossRef]

- Kendall, Stuart, (1961) The advanced Theory of Statistics, Volume 2, Inference and Relationship, Hafner Publishing Company.

- Meeker, W., Hahn, G.., Escobar, L. Statistical Intervals: A Guide for Practitioners and Researchers. John Wiley & Sons. 2017.

- Mood, Graybill, Introduction to the Theory of Statistics, 2nd ed.: McGraw Hill; 1963.

- Papoulis, A.; Saunders, H. Probability, Random Variables and Stochastic Processes. J. Vib. Acoust. 1989, 111, 123–125. [CrossRef]

- Rao, C. R., (1965) Linear Statistical Inference and its Applications, Wiley & Sons.

- Rozanov, Y., (1975) Processus Aleatoire, Editions MIR, Moscow, (traduit du russe) Ryan, T. P., (1989) Statistical Methods for Quality Improvement, Wiley & Sons.

- Saaty, T. (1969) Mathematical Methods of Operations Research, McGraw-Hill.

- Saaty, T., Bram, J. (1964) Nonlinear Mathematics, McGraw-Hill.

- Shewhart W. A., (1931) Economic Control of Quality of Manufactured Products, D. Van Nostrand Company.

- Shewhart W.A., (1936) Statistical Method from the Viewpoint of Quality Control Graduate School, Washington.

- D. J. Wheeler, “The normality myth”, Online available from Quality Digest.

- D. J. Wheeler, “Probability limits”, Online available from Quality Digest.

- D. J. Wheeler, “Are you sure we don’t need normally distributed data?” Online available from Quality Digest.

- D. J. Wheeler, “Phase two charts and their Probability limits”, Online available from Quality Digest.

- Feller, W. (1967) An Introduction to Probability Theory and its Applications, Vol. 1, 3rd Ed. Wiley.

- Feller, W. (1965) An Introduction to Probability Theory and its Applications, Vol. 2, Wiley.

- Parzen, E. (1999) Stochastic Processes, Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics.

- Jones, P., Smith, P. (2018) Stochastic Processes An Introduction, 3rd Ed. CRC Press.

- Knill, O. Probability Theory and Stochastic Processes with Applications; World Scientific Pub Co Pte Ltd: Singapore, Singapore, 2016; ISBN: .

- Shannon, Weaver (1949) The Mathematical Theory of Communication, University of Illinois Press.

- Galetto, F., (1981, 84, 87, 94) Affidabilità Teoria e Metodi di calcolo, CLEUP editore, Padova (Italy).

- Galetto, F., (1982, 85, 94) “Affidabilità Prove di affidabilità: distribuzione incognita, distribuzione esponenziale”, CLEUP editore, Padova (Italy).

- Galetto, F., (1995/7/9) Qualità. Alcuni metodi statistici da Manager, CUSL, Torino (Italy).

- Galetto, F., (2010) Gestione Manageriale della Affidabilità”, CLUT, Torino (Italy).

- Galetto, F., (2015) Manutenzione e Affidabilità, CLUT, Torino (Italy).

- Galetto, F., (2016) Reliability and Maintenance, Scientific Methods, Practical Approach”, Vol-1, www.morebooks.de.

- Galetto, F., (2016) Reliability and Maintenance, Scientific Methods, Practical Approach”, Vol-2, www.morebooks.de.

- Zhang, H.; Guo, J.; Zhou, L. Hope for the Future: Overcoming the DEEP Ignorance on the CI (Confidence Intervals) and on the DOE (Design of Experiments. Sci. J. Appl. Math. Stat. 2015, 3, 70. [CrossRef]

- Galetto, F., 2019, Statistical Process Management, ELIVA press ISBN 9781636482897.

- Galetto, F., (1989) Quality of methods for quality is important, EOQC Conference, Vienna,.

- Galetto, F., (2015) Management Versus Science: Peer-Reviewers do not Know the Subject They Have to Analyse, Journal of Investment and Management. Vol. 4, No. 6, pp. 319-329. [CrossRef]

- Galetto, F. The first step to Science Innovation: Down to the Basics. Sci. Innov. 2015, 3, 81. [CrossRef]

- Galilei, Galileo, Saggiatore, 1623 (in Italian).

- Galilei, Galileo, Dialogo sopra i due massimi sistemi del mondo, Tolemaico e Copernicano (Dialogue on the two Chief World Systems), 1632 (in Italian).

- Galetto, F. Minitab T charts and quality decisions. J. Stat. Manag. Syst. 2021, 25, 315–345. [CrossRef]

- Galetto, F. Minitab T charts and quality decisions. J. Stat. Manag. Syst. 2021, 25, 315–345. [CrossRef]

- Galetto, F., (2012) Six Sigma: help or hoax for Quality?, 11th Conference on TQM for HEI, Israel.

- Galetto, F., (2020) Six Sigma_Hoax against Quality_Professionals Ignorance and MINITAB WRONG T Charts, HAL Archives Ouvert, 2020.

- Galetto, F., (2021) Control Charts for TBE and Quality Decisions, submitted.

- Galetto F. (2022), “Affidabilità per la manutenzione Manutenzione per la disponibilità”, tab edezioni, Roma (Italy), ISBN 978-88-92-95-435-9, www.tabedizioni.it.

- Scholar, P.L.A.P.d.T.I.; Galetto, F. ASSURE: Adopting Statistical Significance for Understanding Research and Engineering. 2021, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Galetto F. (2023) Control Charts, Scientific Derivation of Control Limits and Average Run Length, International Journal of Latest Engineering Research and Applications (IJLERA) ISSN: 2455-7137 Volume – 08, Issue – 01, January 2023, PP – 11-45.

- Galetto, F. GIQA the Golden Integral Quality Approach: from Management of Quality to Quality of Management. Total. Qual. Manag. 1999, 10, 17–35. [CrossRef]

- Galetto, F., (2004) Six Sigma Approach and Testing, ICEM12 –12th International Conference on Experimental Mechanics, 2004, Bari Politecnico (Italy).

- Galetto, F., (2006) Quality Education and quality papers, IPSI, Marbella (Spain).

- Galetto, F., (2006) Quality Education versus Peer Review, IPSI, Montenegro.

- Galetto, F., (2006) Does Peer Review assure Quality of papers and Education? 8th Conference on TQM for HEI, Paisley (Scotland).

- Montgomery D., (1996, 2009, 2011) Introduction to Statistical Quality Control, Wiley & Sons (wrong definition of the term "Quality", and many other drawbacks in wrong applications).

- Montgomery D., (2019) “Introduction to Statistical Quality Control”, 8th Wiley & Sons.

- Galetto, F., “Design Of Experiments and Decisions, Scientific Methods, Practical Approach”, 2016, www.morebooks.de.

- Galetto, F., “The Six Sigma HOAX versus the versus the Golden Integral Quality Approach LEGACY”, 2017, www.morebooks.de.

- Galetto, F., “Quality Education on Quality for Future Managers”, 1st Conference on TQM for HEI (Higher Education Institutions), 1998, Toulone (France).

- Galetto, F., “Quality Education for Professors teaching Quality to Future Managers”, 3rd Conference on TQM for HEI, 2000, Derby (UK).

- Galetto, F., “Quality, Bayes Methods and Control Charts”, 2nd ICME 2000 Conference, 2000, Capri (Italy).

- Galetto, F., “Looking for Quality in "quality books", 4th Conference on TQM for HEI, 2001, Mons (Belgium).

- Galetto, F. Quality and Control Carts: Managerial assessment during Product Development and Production Process”. Automotive and Transportation Technology Congress and Exposition. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, SpainDATE OF CONFERENCE; .

- Galetto, F. Quality QFD and control charts: a managerial assessment during the product development process”. Automotive and Transportation Technology Congress and Exposition. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, SpainDATE OF CONFERENCE; .

- Galetto, F., “Business excellence Quality and Control Charts”, 7th TQM Conference, 2002, Verona (Italy).

- Galetto, F., “Fuzzy Logic and Control Charts”, 3rd ICME 2002 Conference, Ischia (Italy).

- Galetto, F., “Analysis of "new" control charts for Quality assessment”, 5th Conference on TQM for HEI, 2002, Lisbon (Portugal).

- Galetto, F., “The Pentalogy, VIPSI, 2009, Belgrade (Serbia).

- Galetto, F., The Pentalogy Beyond, 9th Conference on TQM for HEI, 2010, Verona (Italy).

- Scholar, P.L.A.P.d.T.I.; Galetto, F. ASSURE: Adopting Statistical Significance for Understanding Research and Engineering. 2021, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Galetto, F., (2024), News on Control Charts for JMP, Academia.edu.

- Galetto, F., Papers and Documents in Academia.edu, 2015-2025.

- Galetto, F., Several Papers and Documents in the Research Gate Database, 2014.

- Giordani, A., (2011), Lezioni di Filosofia della Scienza, EduCatt, ISBN 978-88-8311-787-9.

| Franceschini F. et al. | On-line service quality control: The ‘Qualitometro’ method | Quality Engineering | 1999 | QI |

| Franceschini F. et al. | Service Qualimetrics: The Qualitometro II method | Quality Engineering | 1999 | QII |

| Franceschini F. et al. | Control chart for linguistic variables: A method based on the use of linguistic quantifiers | International Journal of Production Research | 1999 | |

| Franceschini F. et al. | Qualitative ordinal scales: The concept of ordinal range | Quality Engineering | 2004 | |

| Franceschini F. et al. | Ordered Sample Control Charts for Ordinal Variables (named here Qualitometro III) | Quality and Reliability Engineering International | 2005 | QIII |

| Original data | Scalarised data, with mean and range | Scalarised Control Limits | Linguistic | |||||||||||||

| Sample\part | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 4th | 1st | 2ndt | 3rd | 4th | Ri | OWA | ri | |||||

| 1 | H | H | M | H | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2.75 | 1 | 1.721 | 3.179 | 0 | 2.282 | M | 1 |

| 2 | H | M | H | H | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2.75 | 1 | 1.721 | 3.179 | 0 | 2.282 | M | 1 |

| 3 | H | M | M | H | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2.50 | 1 | 1.721 | 3.179 | 0 | 2.282 | H | 1 |

| 4 | H | H | M | L | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2.25 | 2 | 1.721 | 3.179 | 0 | 2.282 | M | 2 |

| 5 | H | M | M | H | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2.50 | 1 | 1.721 | 3.179 | 0 | 2.282 | H | 1 |

| 6 | M | H | M | M | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2.25 | 1 | 1.721 | 3.179 | 0 | 2.282 | M | 1 |

| 7 | H | M | H | M | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2.50 | 1 | 1.721 | 3.179 | 0 | 2.282 | M | 1 |

| 8 | L | L | M | L | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1.25 | 1 | 1.721 | 3.179 | 0 | 2.282 | M | 1 |

| 9 | M | H | H | H | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2.75 | 1 | 1.721 | 3.179 | 0 | 2.282 | H | 1 |

| 10 | H | H | H | H | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3.00 | 0 | 1.721 | 3.179 | 0 | 2.282 | H | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).