1. Introduction

Since 1989, the author (FG) tried

to inform the Scientific Community about the flaws in the use of (“wrong”)

quality methods for making Quality

[1]

and in 1999 about the GIQA (Golden Integral Quality Approach)

showing how to manage Quality during all the activities of the Product and

Process Development in a Company

[2]

, including the Process Management and Control Charts (CC) for Process Control.

Here we show how to deal

correctly with I-CC (Individual Control Charts)

by analysing a literature case [3] comprising the famous data-set on coal-mining disasters of

Jarrett (1979); these data are considered and analysed in [4,5].

We found very interesting the

statements in the Excerpt 1:

In the recent paper “Misguided

Statistical Process Monitoring Approaches” by W. Woodall, N. Saleh, M.

Mahmoud, V. Tercero-Gómez, and S. Knoth, published in Advanced Statistical

Methods in Process Monitoring, Finance, and Environmental Science, 2023, We

read in the Abstract: Hundreds of papers on flawed statistical

process monitoring (SPM) methods have appeared in the literature over the past

decade or so. The presence of so many ill-advised methods, and so much

incorrect theory, adversely affects the SPM research field. Critiques of some

of the various misguided, and/or misrepresented, approaches have been published

in the past 2 years in an effort to stem this tide. These critiques are briefly

reviewed here. References…

Excerpt 1

.

From the paper “Misguided Statistical

Process Monitoring Approaches”.

We agree with the authors in the

excerpt 1, but, nevertheless, they did not realise the problem that we are

giving here: wrong Control Limits in CCs for Rare Events, with data

exponentially or Weibull distributed. See References…

Using the data in

[3–5]

with good statistical methods

[6–33]

we give our

“reflections on Control Charts (CCs)”.

We will try to state that several

papers (that are not cited here, but you can find in the “Garden of

flowers”

[24]

and

some in the

Appendix C

) compute in an a-scientific way (see the formulae in the

Appendix C

) the Control Limits

of CCs for “Individual Measures or Exponential, Weibull and Gamma distributed

data”, indicated as I-CC (Individual Control Charts);

we dare to show, to the Scientific Community, how to compute the True

Control Limits. If the author is right, then all the decisions, taken

up today, have been very costly to the Companies using those Control Limits;

therefore, “Corrective Actions” are needed, according to the Quality

Principles, because NO “Preventive Actions” were taken

[1,2,27–36]

: this is shown through

the suggested published papers. Humbly, given our strong commitment to Quality

[34–57]

, we would dare to provide

the “truth”: Truth makes you free [hen (“hic et nunc”=here and now)].

On 22nd of February

2024, we found the paper “Publishing an applied statistics paper:

Guidance and advice from editors” published in Quality and

Reliability Engineering International (QREI-2024, 1-17) [by C. M.

Anderson-Cook, Lu, R. B. Gramacy, L. A. Jones-Farmer, D. C. Montgomery, W. H.

Woodall; the authors have important qualifications and Awards]; since I-CC is a

part of “applied statistics” we think that their hints will help: the

authors’ sentence “Like all decisions made in the face of uncertainty, Type

I (good papers rejected) and Type II (flawed papers accepted) errors happen

since the peer review process is not infallible.” is very important for

this paper: the interested readers can see

[34–57]

.

By reading

[24]

, the readers are confronted

with this type of practical problem: we have a warehouse with two departments

- 1)

in the 1

st of them, we have a sample (the “

The Garden of flowers… in [

24]”) of “products (

papers)” produced by various production lines (

authors)

- 2)

while, in the other, we have some few products produced by the same production line (same author)

- 3)

several inspectors (Peer Reviewers, PRs) analyse the “quality of the products” in the two departments; the PRs can be the same (but we do not know) for both the departments

- 4)

The final result, according to the judgment of the inspectors (PRs), is the following: the products stored in the 1

st dept. are good, while the products in the 2

nd dept. are defective. It is a very clear situation, as one can guess by the following statement of a PR: “

Our limits [in the 1

st dept.]

are calculated using standard mathematical statistical results/methods as is typical in the vast literature of similar papers [

4,

5,

24].” See the

standard mathematical statistical results/methods in theFigures A1, A2, A3, of the

Appendix A and meditate (see the formulae there)!

Hence, the problem becomes “…the

standard … methods

as is typical …

”: are

those standards typical methods (in the “The Garden … in

[24]

” and in the

Appendix C

) scientific?

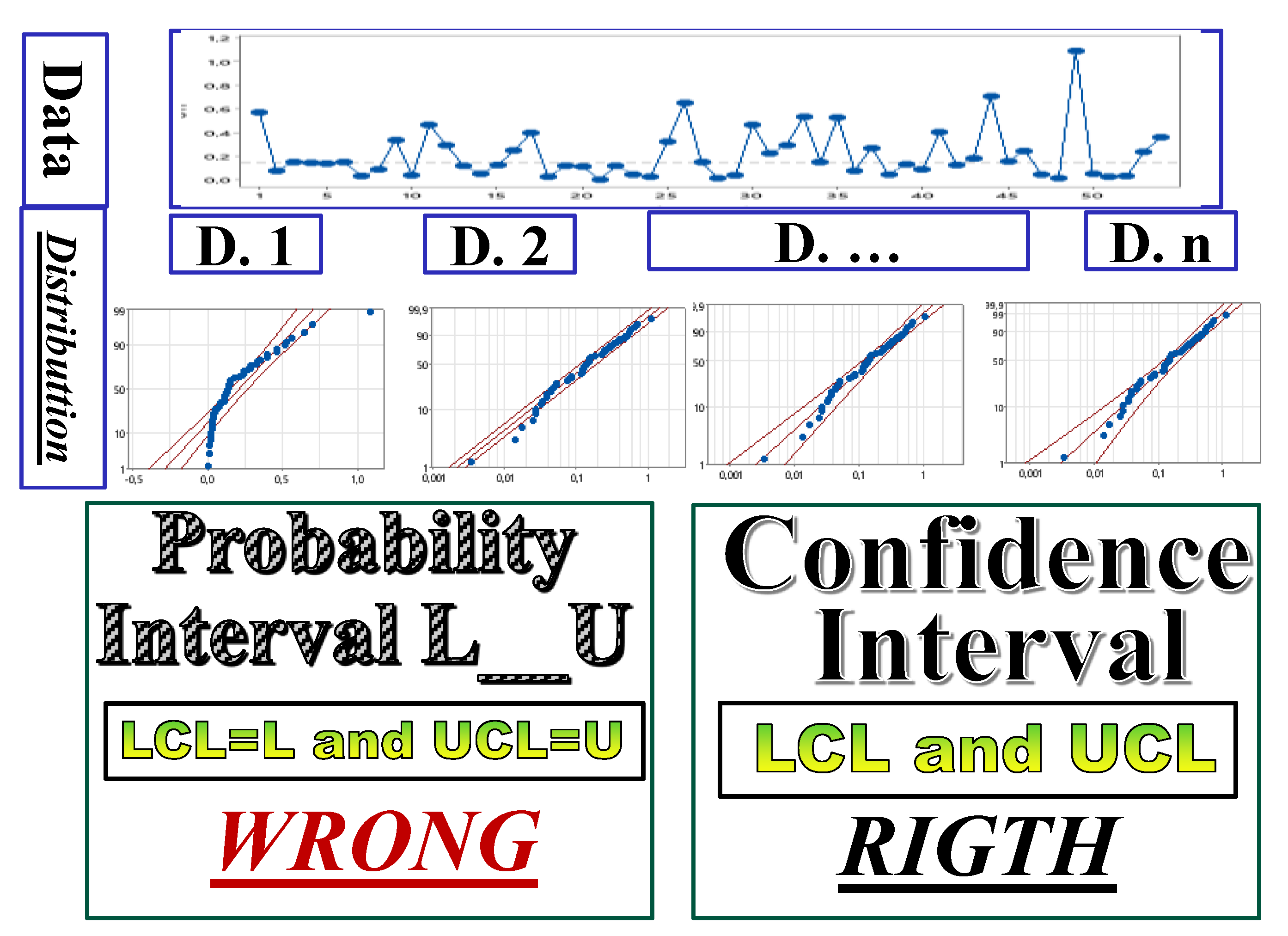

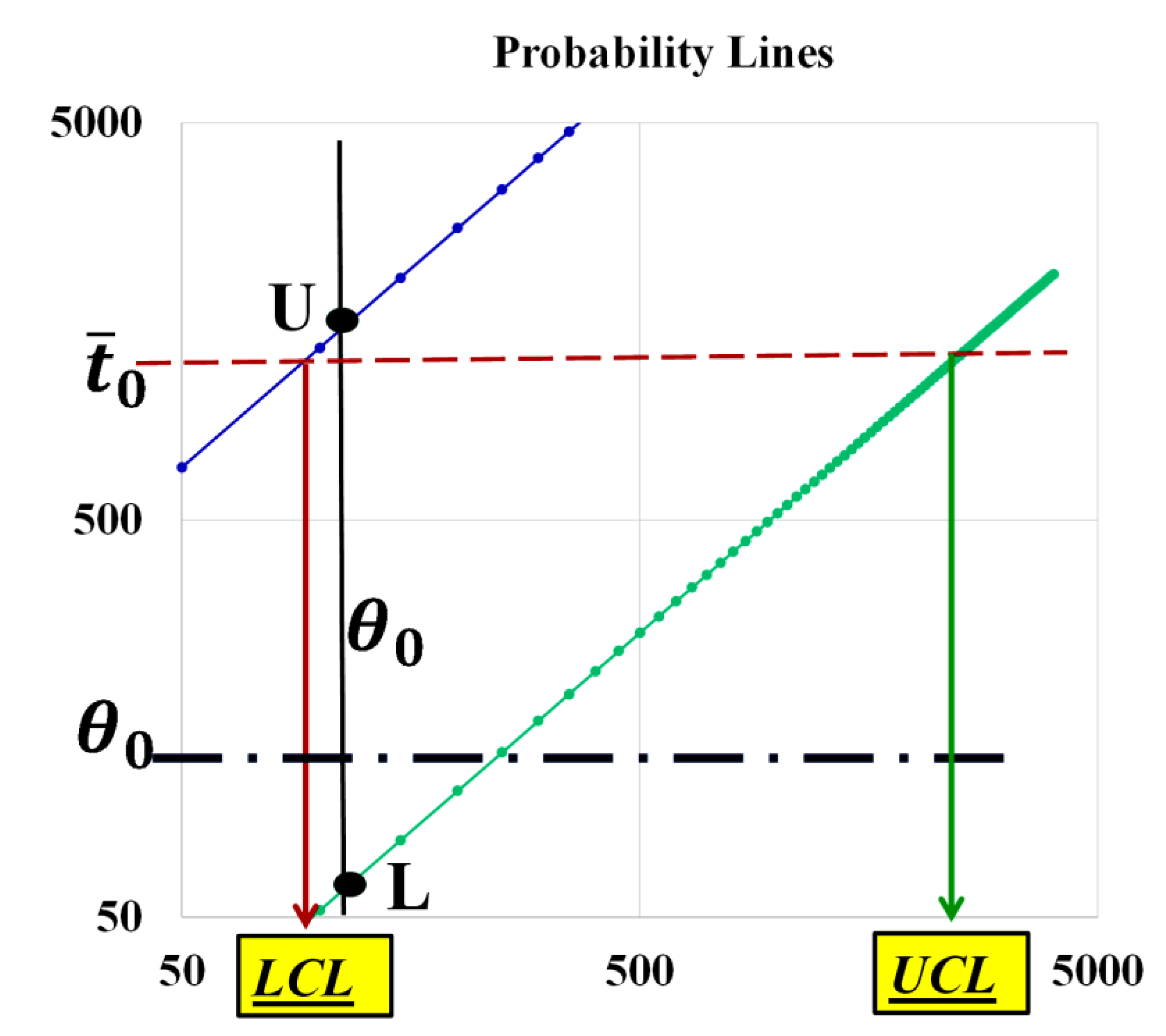

The practical problem becomes

hence a Theoretical one

[1–57]

(all references and

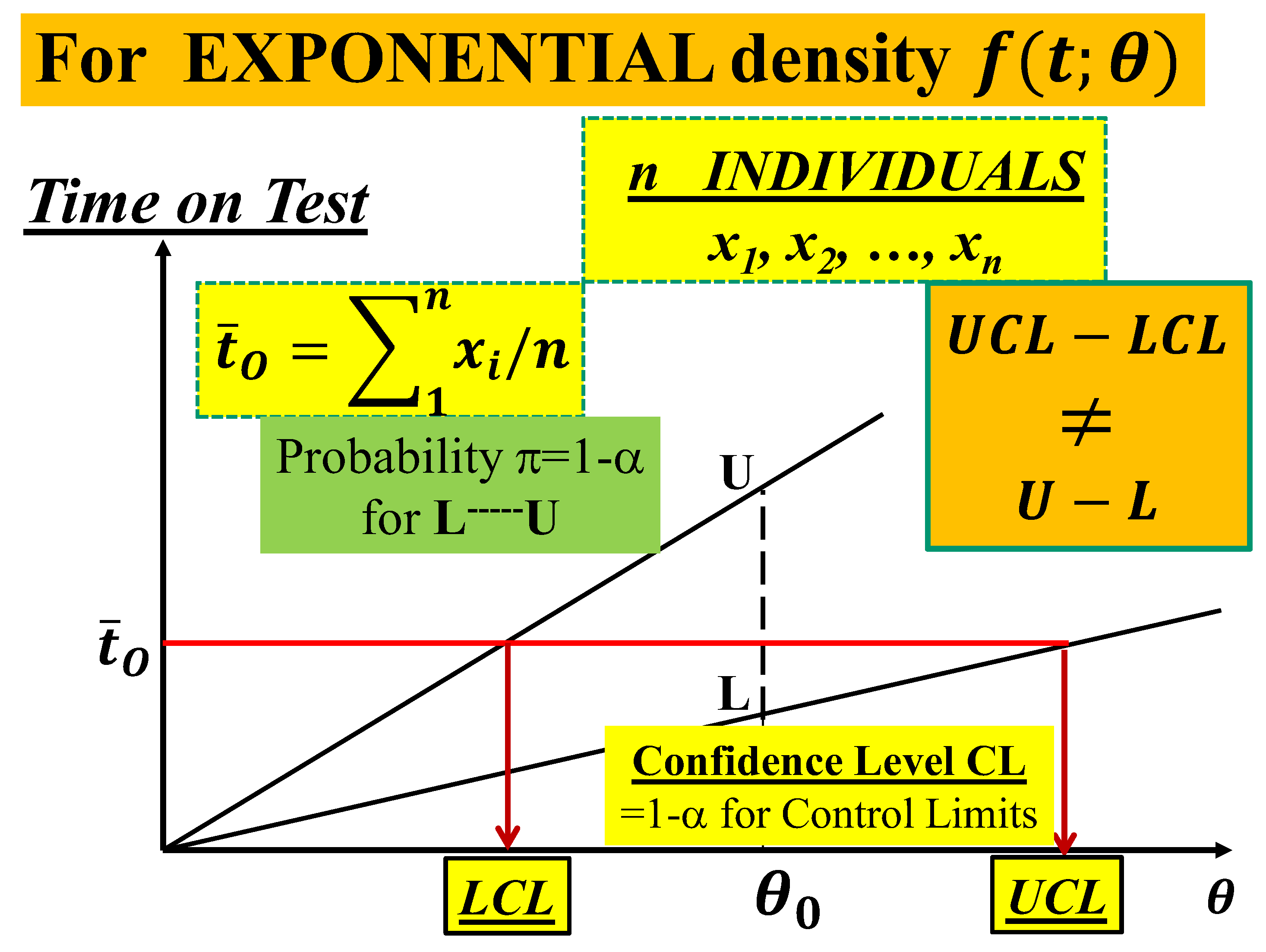

Figure 1

): we show here, immediately, the wrong formulae (either

using the parameter

or its estimate

, with

) in the formula (1)

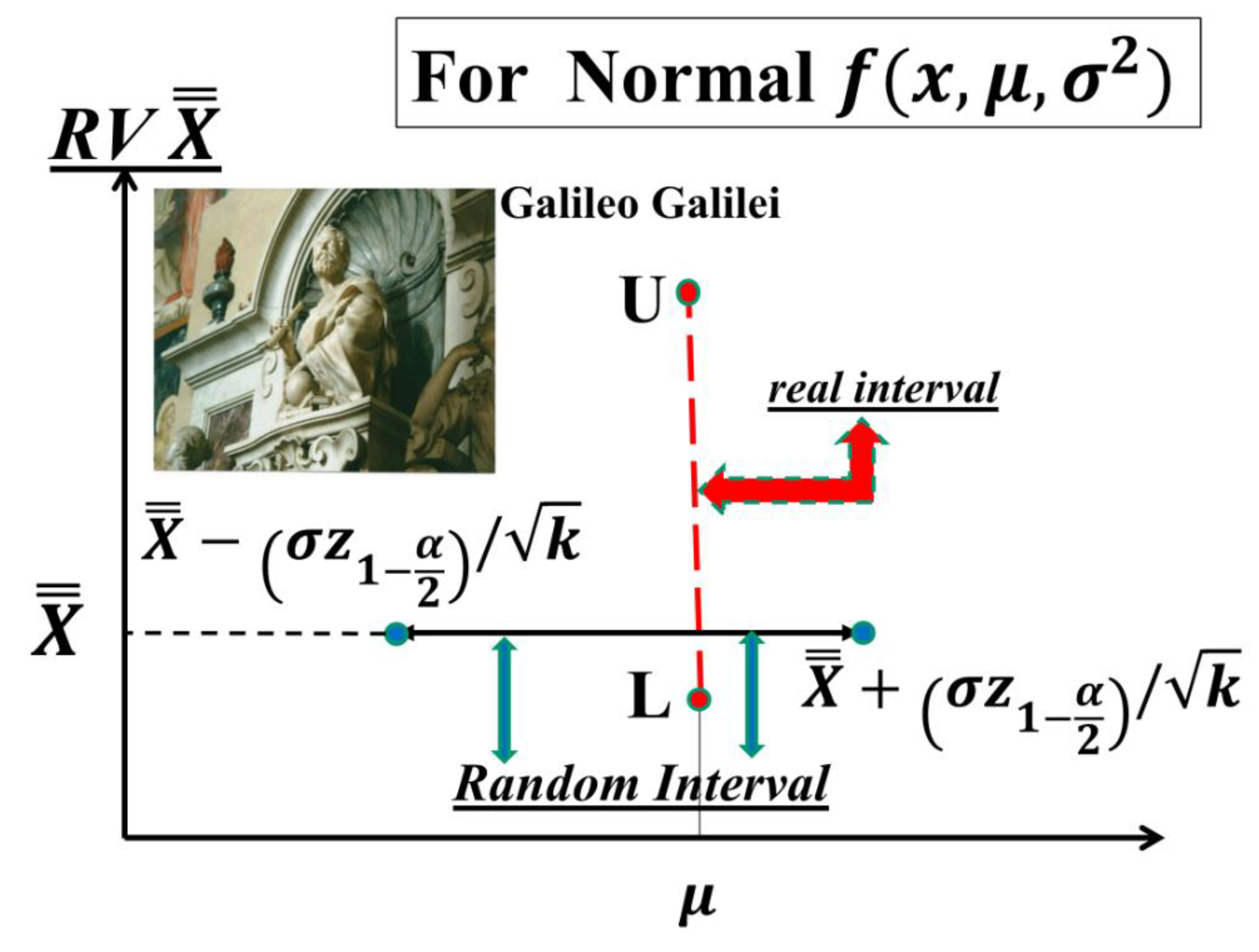

Figure 1.

Theoretical Difference between L------U and LCL------UCL.

Figure 1.

Theoretical Difference between L------U and LCL------UCL.

In the formulae (1), in the (named) interval LCL------UCL

(Control Interval), the LCL must be L and the UCL must be U, vertical interval

L------U (Figure 1); the

actual interval LCL------UCL is the horizontal one in the Figure 1, which is not that of the formulae

(1). Since the errors have been continuing for at least 25 years, we dare to

say that this paper is an Education Advance for all the Scholars, for the software sellers and the users: they

should study the books and papers in [1–57].

The readers could think that the

I-CCs are well known and well dealt in the scientific literature about Quality.

We have some doubt about that: we will show that, at least in one field, the

I-CC_TBE (with TBE, Time Between Event data) usage, it is not so: there are

several published papers, in “scientific magazines and Journals (well

appreciated by the Scholars)” with wrong Control Limits; a sample of the

involved papers (from 1994 to January 2024) can be found in

[23,24]

”. Therefore, those

authors do not extract the maximum information from the data in the Process

Control. “The Garden…”

[24]

and the excerpts 1, with the Deming’s statements, constitute the

Literature Review.

Excerpt 2

.

Some statements of Deming about

Knowledge and Theory (Deming 1986, 1997).

We hope that the Deming statements

about knowledge will interest the Readers (Excerpt 2).

A preliminary case is shown in

Appendix A

.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. A Reduced Background of Statistical Concepts

This section is essential to

understand the “problems related to I-CC” as we found in the literature. We

suggest it for the formulae given and for the difference between the concepts

of PI (Probability Interval, NOT “Prediction Interval”) and CI (Confidence

Interval): this is overlooked in “The Garden …

[24]

” (a sample is in the

Appendix C

).

See a first case in the appendix

A. Therefore, we humbly ask the reader to carefully meditate on the content.

Engineering Analysis is related to

the investigation of phenomena underlying products and processes; the analyst

can communicate with the phenomena only through the observed data,

collected with sound experiments (designed for the purpose): any phenomenon, in

an experiment, can be considered as a measurement-generating process

[MGP, a black box that we do not know] that provides us with information about

its behaviour through a measurement process [MP, known and managed by

the experimenter], giving us the observed data (the “message”).

It is a law of nature that the

data are variable, even in conditions considered fixed, due to many unknown

causes.

MGP and MP form the Communication

Channel from the phenomenon to the experimenter.

The information, necessarily

incomplete, contained in the data, has to be extracted using sound statistical

methods (the best possible, if we can). To do that, we consider a statistical

model F(x|

θ

) associated with a random variable (RV) X giving rise to the

measurements, the “determinations” {x1, x2, …, xn}=D

of the RV, constituting the “observed sample” D; n is the sample size.

Notice the function F(x|

θ

) [a function of real numbers, whose form we assume we know] with

the symbol

θ

accounting for an unknown quantity (or some unknown quantities)

that we want to estimate (assess) by suitably analysing the sample D.

We indicate by

the pdf (probability density

function) and by

the Cumulative Function, where

is the set of the parameters of

the functions.

When

we have the Normal model,

written as

(x|

), with (parameters) mean E[X]=

μ

and variance

Var[X]=

σ

2

When

we have Exponential model,

with (the single parameter) mean E[X]=

(variance Var[X]=

2

), written in two equivalent ways

.

When we have the observed

sample D={x1, x2, …, xn}, our general

problem is to estimate the value of the parameters of the model (representing

the parent population) from the information given by the sample. We

define some criteria which we require a "good" estimate to satisfy

and see whether there exist any "best" estimates. We assume that the

parent population is distributed in a form, the model, which is completely

determinated but for the value

θ

0

of some parameter, e.g.

unidimensional,

θ

, or bidimensional

θ

={

μ

,

σ

2

}; we consider only one or two

parameters, for easiness.

We seek some function of

θ

, say

τ

(

θ

), named inference

function, and we see if we can find a RV T which can have the following

properties: unbiasedness, sufficiency, efficiency. Statistical Theory allows us

the analysis of these properties of the estimators (RVs).

We use the symbols

and

for the unbiased estimators T1

and T2 of the mean and the variance.

Luckily, we have that T1,

in the Exponential model

, is efficient

[6–21,25–33]

, and it extracts the

total available information from any random sample, while the couple T1

and T2, in the Normal model, are jointly sufficient

statistics for the inference function

τ

(

θ

)=(

μ

,

σ

2

), so

extracting the maximum possible of the total available information from any

random sample. The estimators (which are RVs) have their own “distribution”

depending on the parent model F(x|

θ

) and on the sample D: we use the symbol

for that “distribution”. It is

used to assess their properties. For a given (collected) sample D the estimator

provides a value t (real number) named the estimate of

τ

(

θ

),

unidimensional.

A way of finding the estimate is

to compute the Likelihood Function

[LF] and to maximise it: the

solution of the equation

=0 is termed Maximum Likelihood

Estimate [MLE].

The LF is important because it

allows us finding the MVB (Minimum Variance Bound, Cramer-Rao theorem)

[1,2,6–16,26–36]

of an unbiased RV

T [related to the inference function

τ

(

θ

)], such that

The inverse of the MVB(T) provides

a measure of the total available amount of information in D, relevant to

the inference function

τ

(

θ

) and to the statistical model F(x|

θ

).

Naming IT(T) the

information extracted by the RV T we have that

[6–21,26–36]

IT(T)=1/MVB(T)

⇔

T is an

Efficient Estimator.

If T is an Efficient Estimator

there is no better estimator able to extract more information from D.

The estimates considered before

were “point estimates” with their properties, looking for the “best”

single value of the inference function

τ

(

θ

).

We must now introduce the concept

of Confidence Interval (CI) and Confidence Level (CL)

[6–21,26–36]

.

The “interval estimates”

comprise all the values between

τ

L

(Lower

confidence limit) and

τ

U

(Upper confidence limit); the CI is

defined by the numerical interval CI=

{τ

L

-----

τ

U

}

, where

τ

L

and

τ

U

are two quantities computed from the observed sample D: when

we make the statement that

τ

(

θ

)

∈

CI, we accept, before any computation, that, doing that, we can be

right, in a long run of applications, (1-

α

)%=CL of the applications,

BUT we cannot know IF we are right in the single application (CL=Confidence

Level).

We know, before any computation,

that we can be wrong

α

% of the times but we do not know when it happens.

The reader must be very careful

to distinguish between the Probability Interval

PI=

{

L

-----U

}

, where the

endpoints L and U depends on the distribution

of the estimator T (that we

decide to use, which does not depend on the “observed sample” D) and, on

the probability

π

=1-

α

(that we fix before any computation), as follows by the

probabilistic statement (4) [se the

Figure

1

for the exponential density, when n=1]

and Confidence Interval CI=

{τ

L

-----

τ

U

}

which depends on the “observed sample” D.

Notice that the Probability

Interval PI=

{

L-----U

}

does not depend on the data D: L and U are the

Probability Limits. Notice that, on the contrary, the Confidence Interval CI=

{τ

L

-----

τ

U

}

does depend on the data D.

Shewhart identified this approach,

L and U, on page 275 of

[19]

where he states:

“For the most part, however, we

never know [this is the symbols of Shewhart

for our ] in sufficient detail to set up

such limit… We usually chose a symmetrical range characterised by

limits symmetrically spaced in reference to . Tchebycheff’s Theorem tells us

that the probability P that an observed value of will lie within these symmetric

limits so long as the quality standard is maintained satisfies the inequality

P>1-1/t2. We are still faced with the choice of t. Experience

indicated that t=3 seems to be an acceptable economic value”. See the excerpts

3,…

The Tchebycheff Inequality

: IF the RV X is arbitrary with density f(x) and finite variance

THEN we have the probability

, where

. This is a “Probabilistic

Theorem”.

It can be transferred into Statistics.

Let’s suppose that we want to determine experimentally the unknown mean

within a “stated error

ε

”. From the

above (Probabilistic) Inequality we have

; IF

THEN the event

is “very probable” in an

experiment: this means that the observed value

of the RV X can be written as

and hence

. In other words, using

as an estimate of

we commit an error that “most

likely” does not exceed

. IF, on the contrary,

, we need n data in order to write

, where

is the RV “mean”; hence we can

derive

., where

is the “empirical mean” computed

from the data. In other words, using

as an estimate of

we commit an error that “most

likely” does not exceed

. See the excerpts 3, 3a, 3b.

Notice

that, when we write

, we consider the Confidence

Interval CI

[6–21,25–33]

, and no longer the Probability Interval PI

[6–21,25–33]

.

These statistical concepts are

very important for our purpose when we consider the Control Charts, especially the Individual CCs, I-CC.

Notice

that the error made by several authors

[4,5,24]

is generated by lack of

knowledge of the difference between PI and CI

[6–21,25–33]

: they think wrongly

that CI=PI, a diffused disease

[4,5,24]

! They should study some of the books/papers

[6–21,25–33]

and remember the

Deming statements (excerpt 2).

The Deming statements are

important for Quality. Managers, scholars; the professors must learn Logic,

Design of Experiments and Statistical Thinking to draw good decisions. The

authors must, as well. Quality must be their number one objective: they must learn

Quality methods as well, using Intellectual Honesty

[1,2,6–21,25–33]

. Using (4), those

authors do not extract the maximum information from the data in the

Process Control. To extract the maximum information from the data

one needs statistical valid Methods

[1,2,6–21,25–33]

.

As you can find in any good book

or paper [6–21,25–33]

there is a strict relationship between CI and Test Of Hypothesis, known also as

Null Hypothesis Significance

Testing Procedure (NHSTP). In Hypothesis Testing, the experimenter wants to assess if a “thought” value of a

parameter of a distribution is confirmed (or rejected) by the collected data:

for example, for the mean μ (parameter) of the Normal

(x|

) density,

he sets the “null hypothesis” H

0={μ=μ

0} and the probability P=α of being wrong if he decides that the “null

hypothesis” H

0 is true, when actually it is opposite: H

0

is wrong. We analyse the observed sample D={x

1,

x

2, …, x

n} and we compute the empirical (observed)

mean

and the empirical (observed)

standard deviation

hence, we define the Acceptance

interval, which is the CI

Notice that the interval (for the

Normal model) [see the appendix B]

is the Probability Interval such

that

.

A fundamental reflection is

in order

: the formulae (5) and (6) tempt the

unwise guy to think that he can get the Acceptance interval, which is the

CI

[1–23]

, by

substituting the assumed values

of the parameters with the empirical

(observed) mean

and standard deviation

.

This

trick is valid only for the Normal distribution

.

More ideas about this can be found

in

[34–57]

.

In the field of Control Charts, following Shewhart, instead of the formula

(5), we use (7)

where the value

of the t distribution is

substituted by the value

of the Normal distribution,

actually

=3, and a coefficient

is used to make “unbiased” the

estimate of the standard deviation, computed from the information given by the

sample.

Actually, Shewhart does not use

the coefficient

is as you can see from page 294

of Shewhart book (1931), where

is the “Grand Mean”, computed

from D [named here empirical (observed) mean

],

is “estimated standard of each

sample” (named here s, with sample size n=20, in excerpt 3)

Excerpt 3

.

From Shewhart book (1931), on page 294.

The application of these ideas in

the Individual CCs can be seen in the

Appendix

A

, in the

Figure A1

: the standard deviation is derived from the Mobile Range (which is

exponentially distributed as the original UTI data). The formula in the excerpt

3 tells us that the process is OOC (Out Of Control).

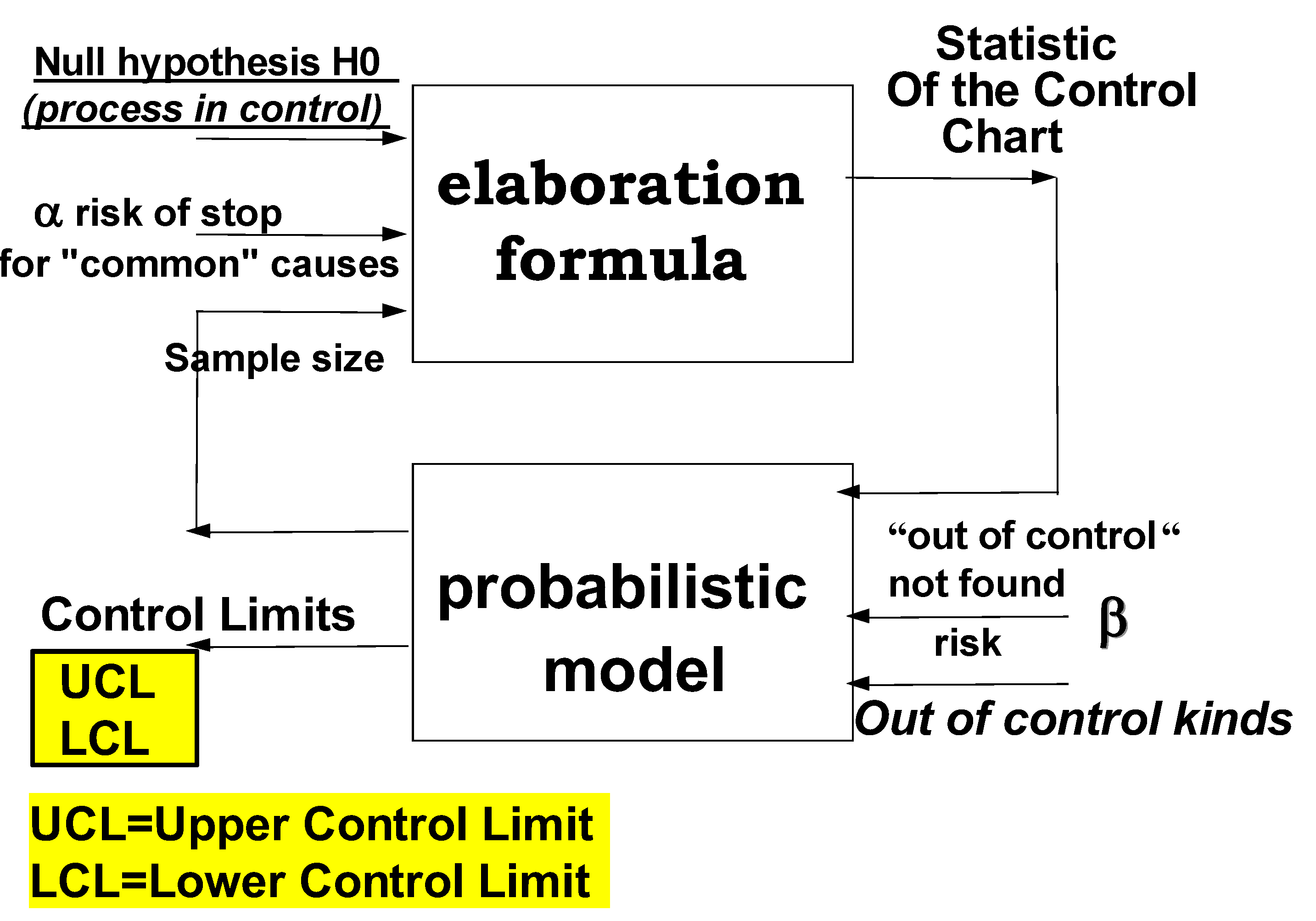

2.2. ControlCharts for Process Management

Statistical Process Management

(SPM) entails Statistical Theory and tools used for monitoring any type of

processes, industrial or not. The Control Charts

(CCs) are the tool used for monitoring a process, to assess its two states: the

first, when the process, named IC (In Control), operates under the common

causes of variation (variation is always naturally present in any

phenomenon) and the second, named OOC (Out Of Control), when the

process operates under some assignable causes of variation. The

CCs, using the observed data, allow us to decide if the process is IC or OOC.

CCs are a statistical test of hypothesis for the process null hypothesis H0={IC}

versus the alternative hypothesis H1={OOC}. Control Charts were very considered by Deming

[9,10]

and Juran

[12]

after Shewhart invention

[19,20]

.

We start with Shewhart ideas (see

the excerpts 3, 3a and 3b).

In the excerpts, is the (experimental) “Grand Mean”, computed from

D (we, on the contrary, use the symbol ), is the (experimental) “estimated standard of each

sample” (we, on the contrary, use the symbol s, with sample size n=20, in

excerpts 3a, 3b), is the “estimated mean standard deviation of all

the samples” (we, on the contrary, use the symbol ).

Excerpt 3a. From Shewhart book

(1931), on page 89.

On page 95, he also states that

Excerpt 3b. From Shewhart book

(1931), on page 294.

So, we clearly see that Shewhart,

the inventor of the CCs, used the data to compute the Control Limits,

LCL (Lower Control Limit) and UCL (Upper Control Limit) both for the mean

(the 1st parameter of

the Normal pdf) and for

(the 2nd parameter of

the Normal pdf). They are considered the limits comprising 0.9973n of the

observed data. Similar ideas can be found in

[5–21,25–42]

(with Rozanov, 1975, we see the idea that CCs can be viewed as a

Stochastic Process).

We invite the readers to consider

that if one assumes that the process is In Control (IC) and if he

knows the parameters of the distribution he can test if the assumed known

values of the parameters are confirmed or disproved by the data, then he

does not need the Control Charts; it is

sufficient to use NHSTP! (see App. B)

Remember the ideas in the previous

section and compare Excerpts 3, 3a, 3b (where LCL, UCL depend on the data)

with the following Excerpt 4 (where LCL, UCL depend on the Random Variables)

and appreciate the profound “logic” difference: this is the cause of the many

errors in the CCs for TBE [Time Between Events (see

[4,5,24]

).

The same type

of arguments are used in another paper

[4]

JQT

, 2017

where the data are Erlang distributed with

λ

0

is the

scale parameter and the Control Limits LCL and UCL are defined [copying Xie et

al.] erroneously as

Excerpt 4

.

From a paper in the “Garden…

[24]

”. Notice that one of the

authors wrote several papers….

The formulae, in the excerpt 4,

LCL

1 and UCL

1 are actually the Probability Limits (L

and U) of the Probability Interval PI in the formula (4), when

is the pdf of the Estimator T,

related to the Normal model F(x;

μ

,

σ

2

). Using

(4), those authors do not extract the maximum information from the data in

the Process Control. From the Theory

[6–36]

we derive that the interval L=

μ

Y

-3

σ

Y

------

μ

Y

+3

σ

Y

=U is the PI such that the RV Y=

and it is not the CI of the mean

μ

=

μ

Y

[as wrongly said in the Excerpt 4,

where actually (LCL1-----UCL1)=PI].

The same error is in other books

and papers (not shown here but the reader can see in

[21–24]

).

The data plotted in the CCs

[6–21,25–36]

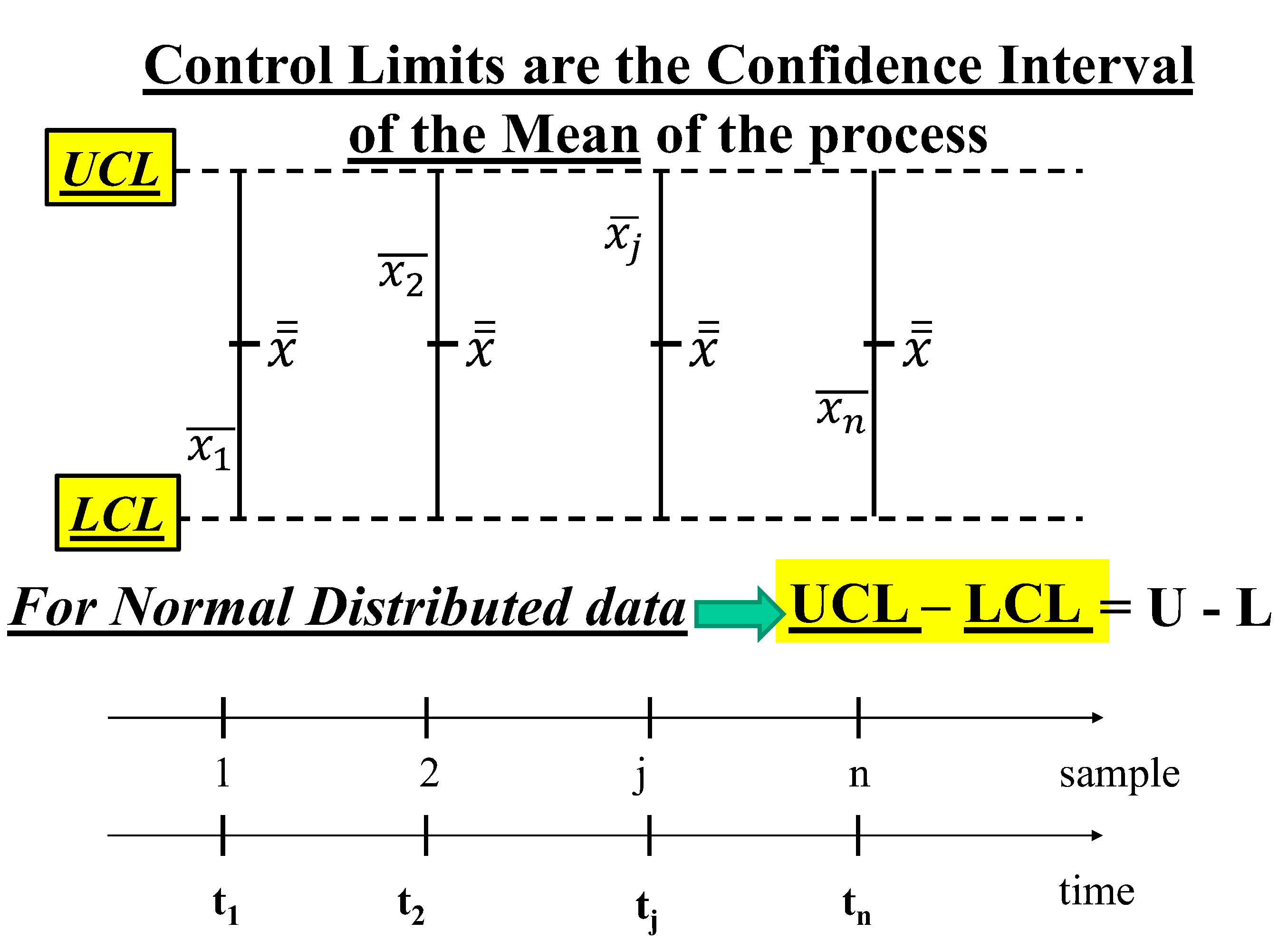

(see the

Figure 2

) are the means

, determinations of the RVs

, i=1, 2, ..., n (n=number of the

samples) computed from the collected data of the i-th sample Di={xij,

j=1, 2, ..., k} (k=sample size)}, determinations of the RVs

at very close instants tij,

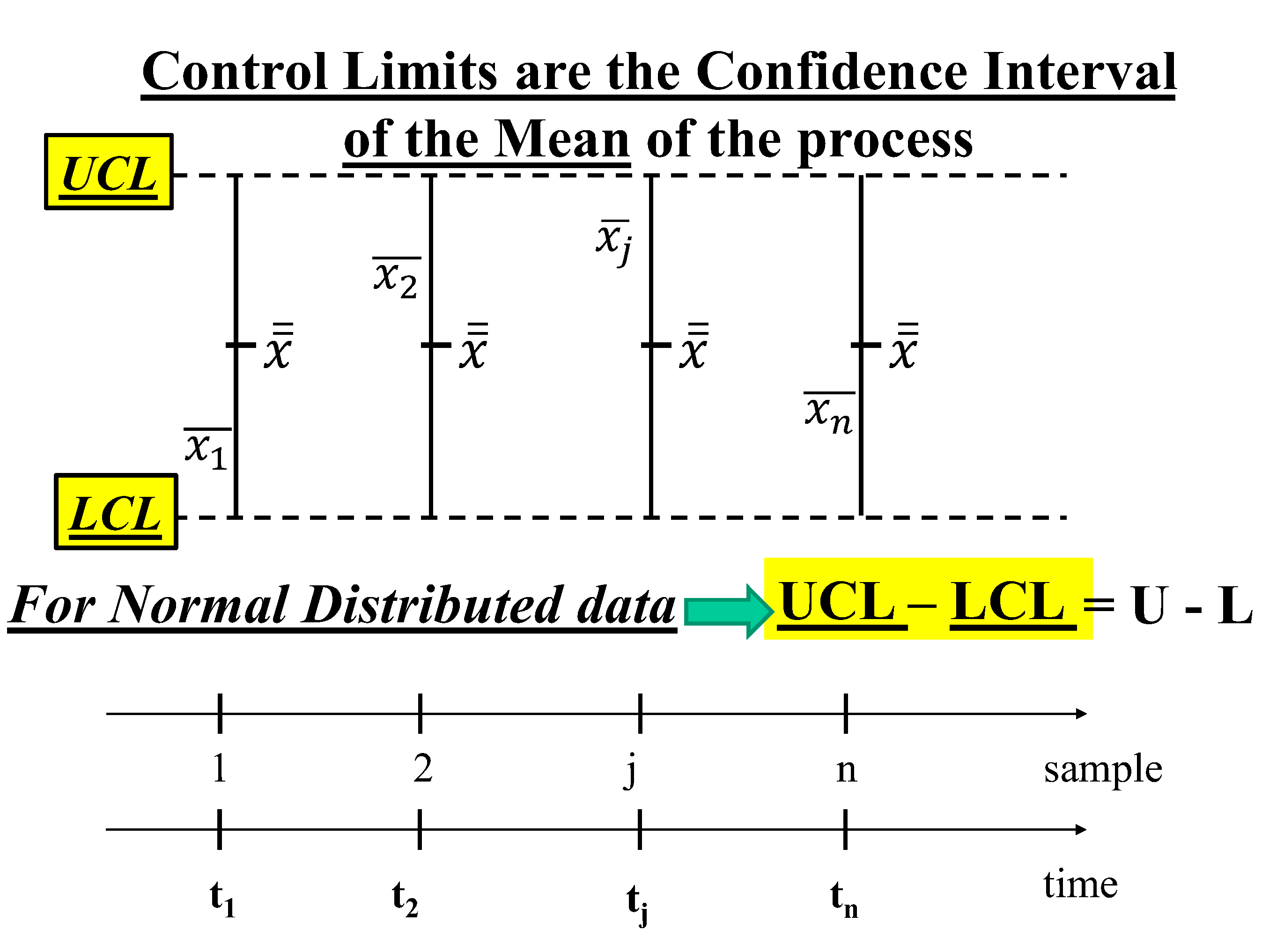

j=1, 2, ..., k. In other applications I-CC (see the

Figure 3

), the data plotted

are the Individual Data

, determinations of the Individual

Random Variables

, i=1, 2, ..., n (n=number of the

collected data), modelling the measurement process (MP) of the “Quality

Characteristic” of the product: this model is very general because it is able

to consider every distribution of the Random Process

, as we can see in the next

section. From the excerpts 3, 3a, 3b and formula (5) it is clear that Shewhart

was using the Normal distribution, as a consequence of the Central Limit

Theorem (CLT)

[6–20,26–36]

. In fact, he wrote on page 289 of his book

(1931) “… we saw that, no matter what the nature of the distribution

function of the quality is, the distribution of the arithmetic mean approaches

normality rapidly with increase in n (his n is our k), and in all

cases the expected value of means of samples of n (our k) is the same as

the expected value of the universe” (CLT in Excerpt 3, 3a, 3b).

and “grand mean”

Figure 2.

Control Limits LCLX----UCLX=L----U (Probability interval), for Normal data (Individuals xij, sample size k) “sample means”

Figure 2.

Control Limits LCLX----UCLX=L----U (Probability interval), for Normal data (Individuals xij, sample size k) “sample means”

Figure 3.

Individual Control Chart (sample size k=1). Control Limits LCL----UCL=L----U (Probability interval), for Normal data (Individuals xi) and “grand mean”

Figure 3.

Individual Control Chart (sample size k=1). Control Limits LCL----UCL=L----U (Probability interval), for Normal data (Individuals xi) and “grand mean”

Let k be the sample size; the RVs

are assumed to follow a normal

distribution and uncorrelated;

[ith rational

subgroup] is the mean of RVs IID

j=1, 2, ..., k, (k data sampled,

at very near times tij).

To show our way of dealing with

CCs we consider the process as a “stand-by system whose

transition times from a state to the subsequent one” are the collected data.

The lifetime of “stand-by system” is the sum of the lifetimes of each unit. The

process (modelled by a “stand-by …”) behaves as a Stochastic Process [25–33], that we can manage by the Reliability Integral Theory (RIT): see

the next section; this method is very general because it is able to consider

every distribution of .

If we assume that

is distributed as f(x)

[probability density function (pdf) of “transitions from a state to the

subsequent state” of a stand-by subsystem] the pdf of the (RV) mean

is, due the CLT (page 289 of 1931

Shewhart book),

[experimental mean

] with mean

and variance

.

is the “grand” mean and

is the “grand” variance: the pdf

of the (RV) grand mean

[experimental “grand” mean

]. In

Figure 2

we show the

determinations of the RVs

and of

.

When the process is Out Of Control (OOC, assignable

causes of variation, some of the means , estimated by the experimental means , are “statistically different)” from the others [6–21,25–36]. We can assess the OOC state of the

process via the Confidence Interval (provided by the Control Limits) with CL=0.9973;

see the Appendix B. Remember the trick

valid only for the Normal Distribution ….; consider the

PI, L=μY-3σY------μY+3σY=U;

putting in place of and in place of we get the CI of when the sample size k is considered for each , with CL=0.9973. The quantity is the mean of the standard deviations of each

sample. This allows us to compare each (subsystem) mean , q=1,2, …, n, to any other (subsystem) mean r=1,2, …, n, and to the (Stand-by system) grand

mean . If two of them are different, the process is

classified as OOC. The quantities and are the Control Limits of the CC. When the Ranges

Ri=max(xij)-min(xij) are considered for each

sample we have , and , U, where is the “mean range” and the coefficients A2,

D3, D4 are tabulated and depend on the sample size k [6–21,25–36].

See the Appendix B:

it is important for understanding our ideas.

The interval LCLX-------UCLX

is the “Confidence Interval” with “Confidence Level” CL=1-α=0.9973 for the unknown mean of the Stochastic Process X(t) [25–36]. The interval LCLR----------UCLR

is the “Confidence Interval” with “Confidence Level” CL=1-α=0.9973 for the unknown Range of the

Stochastic Process X(t) [25–36].

Notice that, ONLY for normally

distributed data, the length of the Control Interval (UCLX-LCLX,

which is the Confidence Interval) equals the length of the Probability

Interval, PI (U-L): UCLX-LCLX=U-L.

The error highlighted, i.e. the confusion

between the Probability Interval and the Control Limits (Confidence

Interval!) has no consequences for decisions when the data are Normally

distributed, as considered by Shewhart. On the contrary, it has BIG

consequences for decisions WHEN the data are Non-Normally distributed

[4,5,24]

.

We think that the paper “Quality

of Methods for Quality is important”, [1]

appreciated and mentioned by J. Juran at the plenary session

of the EOQC (European Organization for Quality Control) Conference (1989),

should be considered and meditated.

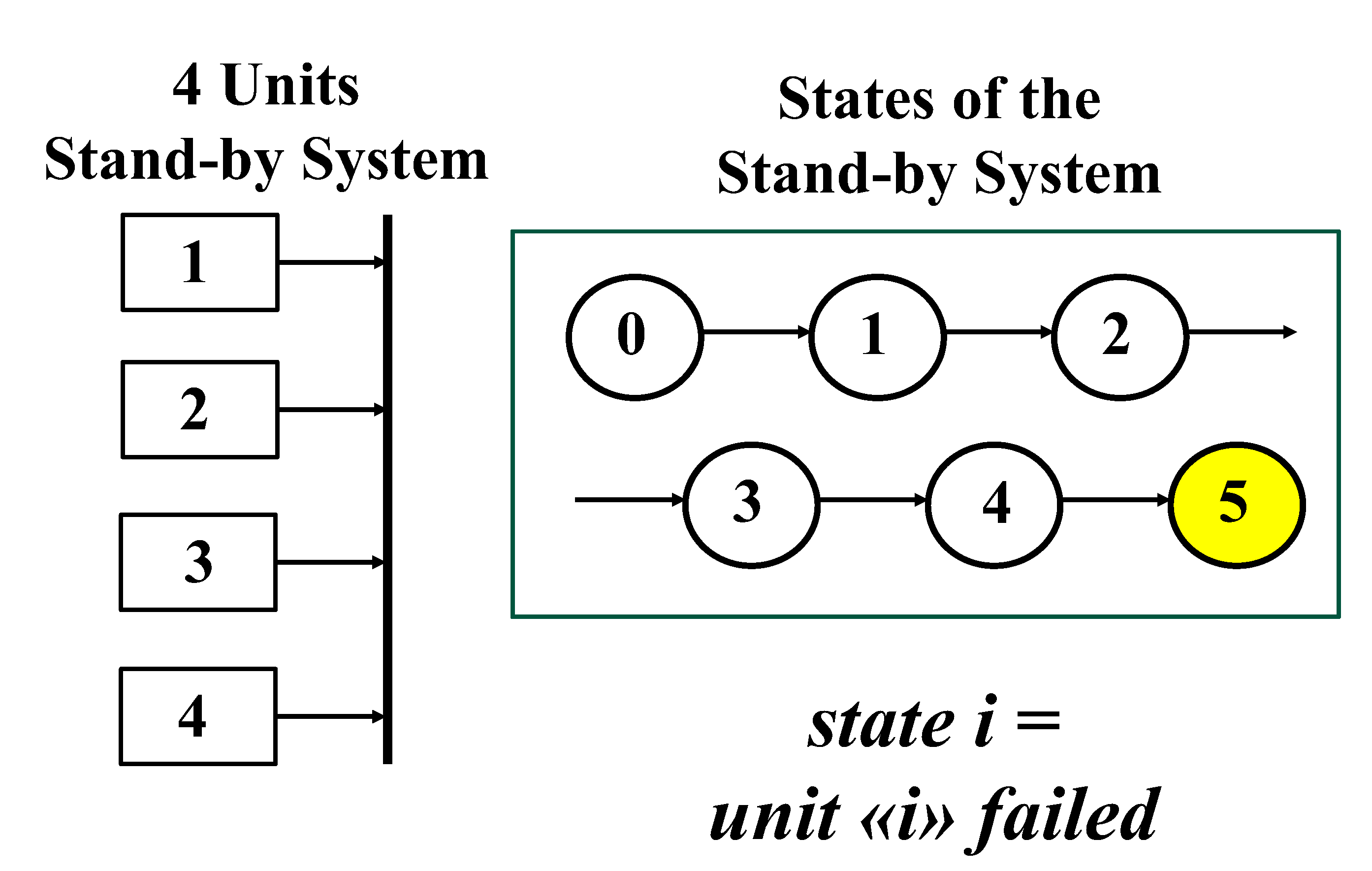

2.3. Statistics and RIT

We are going to present the fundamental concepts

about RIT (Reliability Integral Theory) that we use for computing the Control

Limits of CCs. Since in the example chosen, 4 data will be “compounded” we use

a “4 units Stand-by system”, depicted by 5 states (Figure 4): 0 is the state with all units

not-failed; 1 is the state with the first unit failed; 2 is the state with the

second unit failed; and so on, until the system enters the state 5 where all

the 4 units are failed (down state, in yellow): any transition provides a datum

to be used for the computations. RIT can be found in the author’s books…

Figure 4.

A “4 units Stand-by system” and its states.

Figure 4.

A “4 units Stand-by system” and its states.

RIT can be used for parameters estimation and

Confidence Intervals (CI), (Galetto 1981, 1982, 1995, 2010, 2015, 2016), in

particular for Control Charts (Deming, 1986,

1997, Shewhart 1931, 1936, Galetto 2004, 2006, 2015). In fact, any Statistical

or Reliability Test can be depicted by an “Associated Stand-by System” [25–36] whose transitions are ruled by the kernels bk,j(s);

we write the fundamental system of integral equations for the reliability

tests, whose duration t is related to interval 0-----t; the

collected data tj can be viewed as the times of the various failures

(of the units comprising the System) [t0=0 is the start of the test,

t is the end of the test and g is the number of the data (4 in the Figure 4)]

Firstly, we assume that the kernel is the pdf of the exponential distribution (|), where is the failure rate of each unit and : is the MTTF of each unit. We state that is the probability that the stand-by system does

not enter the state g (5 in Figure 4), at

time t, when it starts in the state j (0, 1, …, 4) at time tj, is the probability that the system does not leave

the state j, is the probability that the system makes the

transition j→j+1, in the interval s-----s+ds.

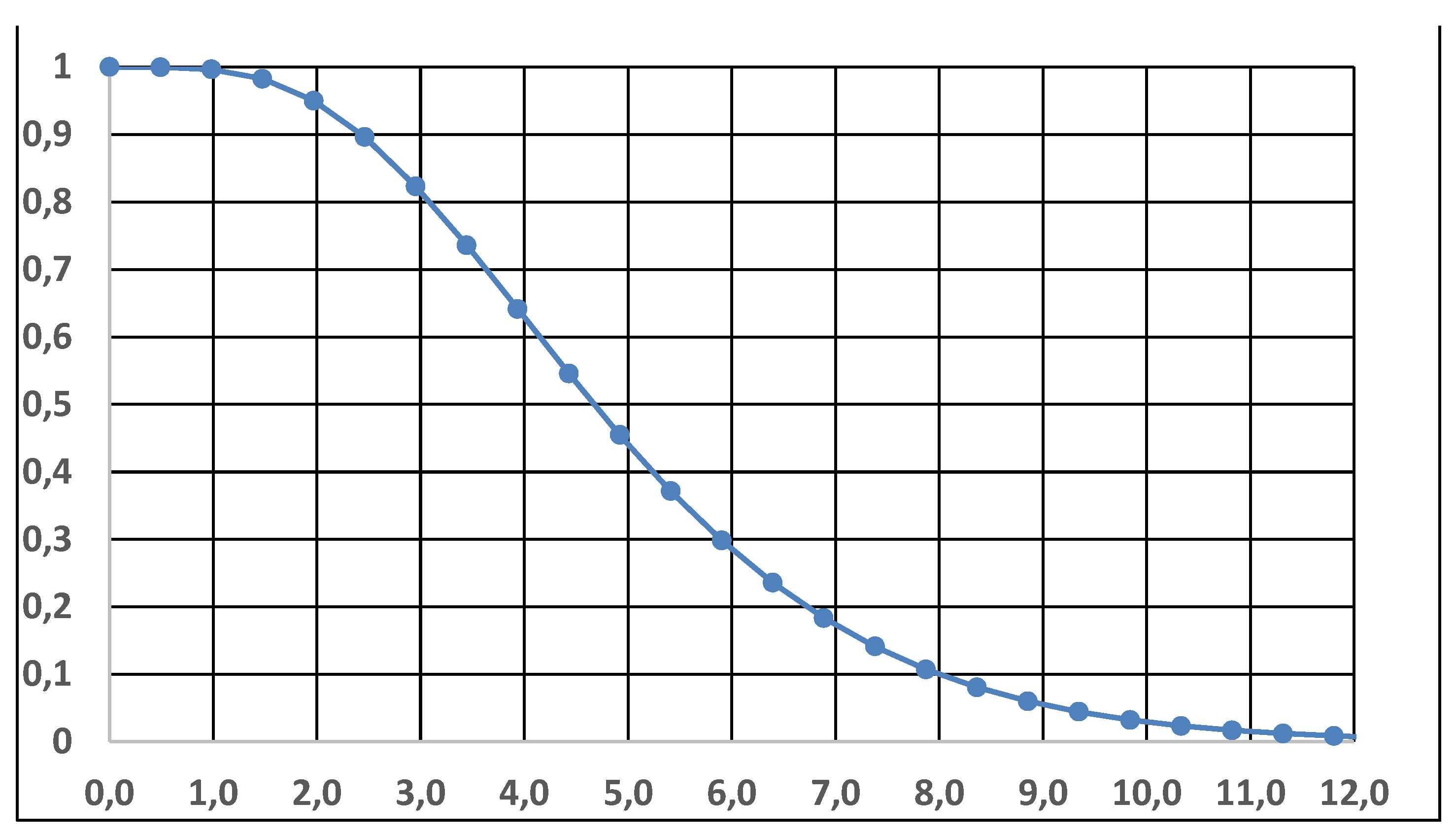

The system reliability

is the solution of the

mathematical system of the Integral Equations (8)

With

we obtain the solution (see Figure 5, putting the Mean Time To Failure

MTTF=θ=123 days,

)

The reliability system (8) can be written in matrix

form,

At the end of the reliability test, at time t, we

know the data (the times of the transitions tj) and the “observed”

empirical sample D={x1, x2, …, xg},

where xj=tj – tj-1 is the length between the

transitions; the transition instants are tj = tj-1 + xj

giving the “observed” transition sample D*={t1, t2, …, tg-1,

tg, t=end of the test}

(times of the transitions tj).

We consider now that we want to estimate the unknown MTTF=θ=1/λ of each item comprising the “associated” stand-by system [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30]: each datum is a measurement from the exponential pdf; we compute the determinant

of the integral system (9), where

is the “Total Time on Test”

[

in the

Figure 5]: the “Associated Stand-by System” [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33] in the Statistics books provides the pdf of the sum of the RV X

i of the “

observed”

empirical sample D={x

1, x

2, …, x

g}. At the end time t of the test, the integral equations, constrained by the

constraintD*, provide the equation

It is important to notice that, in the case of exponential distribution [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36], it is

exactly the same result as the one provided by the MLM Maximum Likelihood Method.

If the kernel is the pdf (|) the data are normally distributed, , with sample size n, then we get the usual estimator such that .

of a “4 units Stand-by system” with MTTF=θ=123 days; is the total time on test of the 4 units. To compute the CI (with CL=0.8), find the abscissas of the intersections at and ….

The same happens with any other distribution provided that we write the kernel .

The reliability function

, [formula (8)], with the parameter

, of the “Associated Stand-by System” provides the

Operating Characteristic Curve (OC Curve, reliability of the system) [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36] and allows to find the Confidence Limits (

Lower and

Upper) of the “unknown” mean

, to be estimated, for any type of distribution (Exponential, Weibull, Rayleigh, Normal, Gamma, …); by solving, with unknown

, the two equations

(

|

)

; we get the two values (

,

) such that

where is the (computed) “total of the length of the transitions xi=tj - tj-1 data of the empirical sampleD” and CL= is the Confidence Level. CI=-------- is the Confidence Interval: and .

For example, with

Figure 5, we can derive

and

, with CL=0.8. It is quite interesting that the book [

14] Meeker et al., “

Statistical Intervals: A Guide for Practitioners and Researchers”, John Wiley & Sons (2017) use the same ideas of FG (shown in the formula 11) for computing the CI; the only difference is that the author FG defined the procedure in 1982 [

26], 35 years before Meeker et al.

2.4. ControlCharts for TBE Data. Some Ideas for Phase I Analysis

Let’s consider now TBE (Time Between Event) data,

exponentially or Weibull distributed. Quite a lot of authors (in the “

Garden … [

24]”)

compute wrongly the Control Limits of these CCs.

The formulae, shown in the section “ControlCharts for Process Management”, are based on the Normal distribution (thanks to the CLT; see the excerpts 3, 3a and 3b); unfortunately, they are used also for NON_normal data (e.g. see formulae (1)): for that, sometimes, the NON_normal data are transformed “with suitable transformations” in order to “produce Normal data” and to apply those formulae (above) [e.g. Montgomery in his book].

Sometimes we have few data and then we use the so called “Individual ControlCharts” I-CC. The I-CCs are very much used for exponentially (or Weibull) distributed data: they are also named “rare events ControlCharts for TBE (Time Between Events) data”, I-CC_TBE.

The Jarret data (1979) are used also in the paper (

found online, 2024, March 1) [

4] (Kumar, Chakraborti et al. with various presence in the “

Garden … [

24]”) who decided to consider the paper [

5] (Zhang et al. also present in the “

Garden …]”): they use the first 30 observed time intervals as phase 1 and start the monitoring at m = 31. You find the original data in the

Table 1 in the paper [

3]; moreover, for the benefit of the readers we provide them in the section 3 “Results”.

It is a very good example for understanding better the problem and the consequences of the difference between PI (Probability Intervals) and the Control Limits, using RIT.

Let’s see what the authors say: Kumar, Chakraborti et al. , Journal of Quality Technology, 2016, present the case by writing (highlight due to FG):

5. An Illustrative Example

In this Section, we use the data from Table 6 of Zhang et al. (2006) (see also Jarrett 1979) in order to illustrate the application of the proposed charting schemes. The data consist of the time intervals in days between explosions in coal mines (i.e., the events) from 15 March 1981 to 22 March 1962 (190 observations in total) in Great Britain. As in Zhang et al. (2006), we consider the first m=30 observations to be from the in-control process, from which we estimate that (or equivalently, the mean TBE is approximately 123 days). In the sequel, we assume that this is the true in-control value . Since our numerical analysis showed that r=4 is the best choice we apply the t4-chart … Thus, the remaining 160 observations are first converted by accumulating a set of four consecutive failure times and the corresponding observations are shown in Table… These are the times until the fourth failure, and are used for monitoring the process in order to detect a change in the mean TBE; an increase (which means process improvement) or a decrease (process deterioration).

Excerpt 5. From Kumar, Chakraborti et al., “Journal of Quality Technology”, 2016.

In the paper of Zhang et al. (2006) we read:

The second example presented here uses real data taken from Jarrett (1979). The data set consists of time intervals in days between explosions in coal mines from March 15, 1851 to March 22, 1962. The data are reproduced in Table 6. We first establish the ARL-unbiased exponential chart with the first 30 observations using the proposed approach. The phase I analysis is presented in Table …. Then the established control limits are used to monitor the subsequent data, i.e., from number 31 to number 190. The resultant ARL-unbiased exponential chart for all the data is plotted in Fig…., where the dotted lines represent the estimated control limits which stop updating at point number 30 and the continuing straight lines represent the established control limits. It is revealed, surprisingly, that the mean of the time intervals between explosions remained constant for a very long period of time (about 40 years), and the accident rate only started to decrease sometime after the 125th explosion. There is an alarm at data point number 80 (value = 0), which is considered here a false alarm.

Excerpt 6. From Zhang et al. (2006), “IIE Transactions”.

Notice that both the papers [

4,

5] are (and were) present in the “

Garden … [

24]”.

Zhang et al., 2006, compute the Control Limits from the first 30 data and find LCL=0.268 and UCL=1013.9 (you can see them in their Table 7, that is “our” excerpt 11).

All the data [30+40 t4] are very interesting for our analysis; we recap the two important points, given by the authors (Kumar et al.):

… first m=30 observations to be from the in-control process, from which we estimate … the mean TBE approximately, 123 days; we name it θ0.

… we apply the t4-chart… Thus, … converted by accumulating a set of four consecutive failure times … the times until the fourth failure, used for monitoring the process to detect a change in the mean TBE.

The 3 authors (Kumar, Chakraborti et al.) state: “… the control limits … t4-chart are seen to be equal to LCL=63.95, UCL=1669.28 with CL (Centre Line)=451.79.”

Notice that the authors Zhang et al. and Kumar, Chakraborti et al. find different Control Limits to be used for monitoring the same process: a very interesting situation; the reason is that they use “different” statistics in Phase II.

The FG findings for the Phase I, using the first 30 data, compute different Control Limits with RIT: RIT solves the I-CC_TBE with

exponentially distributed data as those of

Table 1, considered by Zhang et al. and Kumar et al.

In the previous section, we computed the CI=-------- of the parameter , using the (subsample) “transition times durations”: =“total of the transition times durations (length of the transitions xi=tj - tj-1 data) in the empirical sample (subsample with n=4 only, as an example)” and Confidence Level CL=.

When we deal with a I-CC_TBE we compute the LCL and UCL of the mean θ through the

empirical mean of each transition, for the

n=30 data (

Phase I of Zhang et al. and Kumar et al.); we solve the two following equations (12) for the two unknown values LCL and UCL, for

of each item in the sample, similar to (11)

where now /n is the “mean, to be attributed, to the single lengths of the single transitions xi=tj-tj-1 data in the empirical sampleD with the Confidence Level CL=: and .

In the next sections we can see the Scientific Results found by a Scientific Theory (we anticipate them: the Control Limits are LCL=18.0 days and UCL=88039.3 days).

3. Results

In these sections we provide the scientific analysis of the Jarret data [

3] and compare our result with those of Chakraborty [

4,

5]: the findings are completely different and the decisions, consequently, should be different, with different costs of wrong decisions.

3.1. ControlCharts for TBE Data. Phase I Analysis

The Jarret data are in the

Table 1.

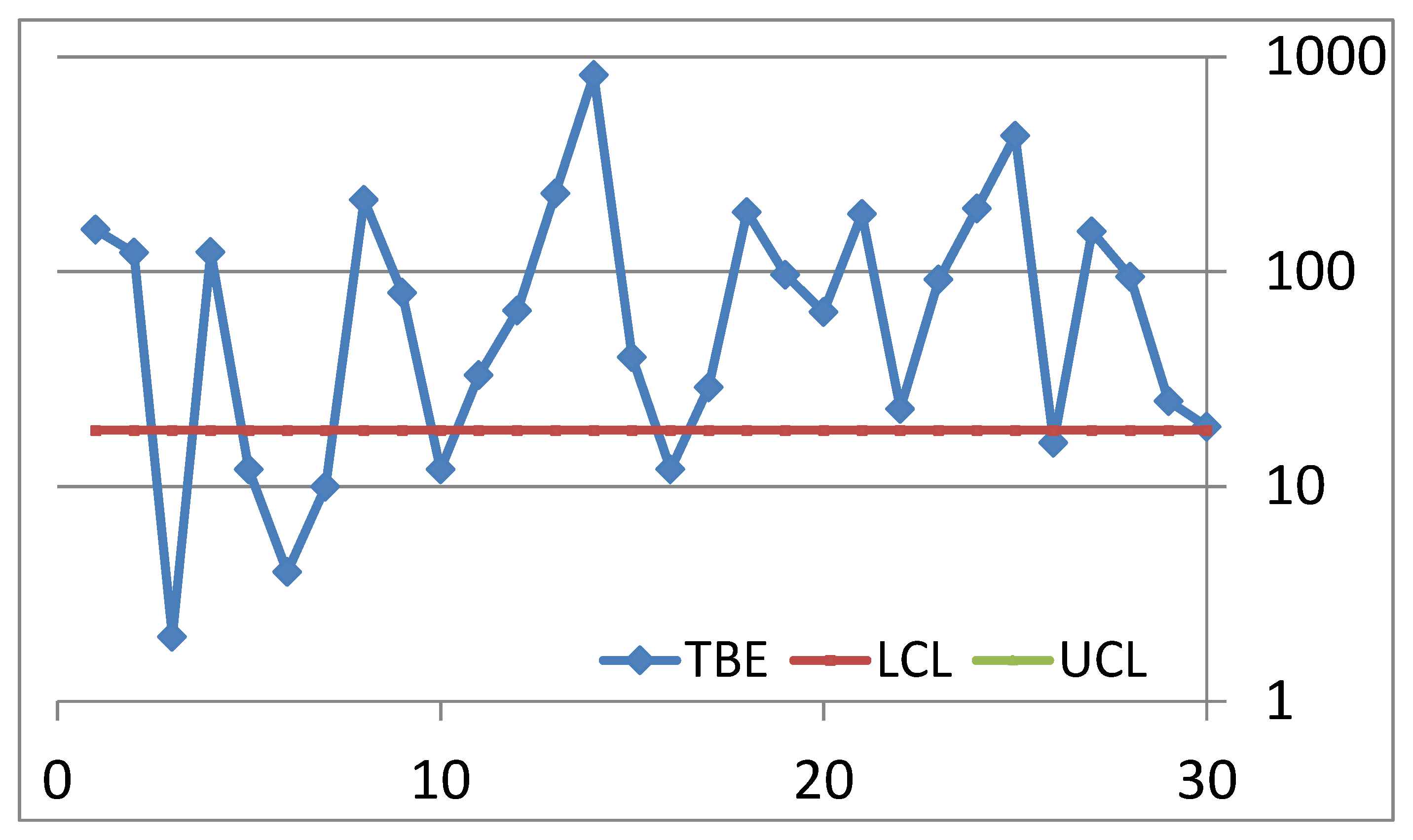

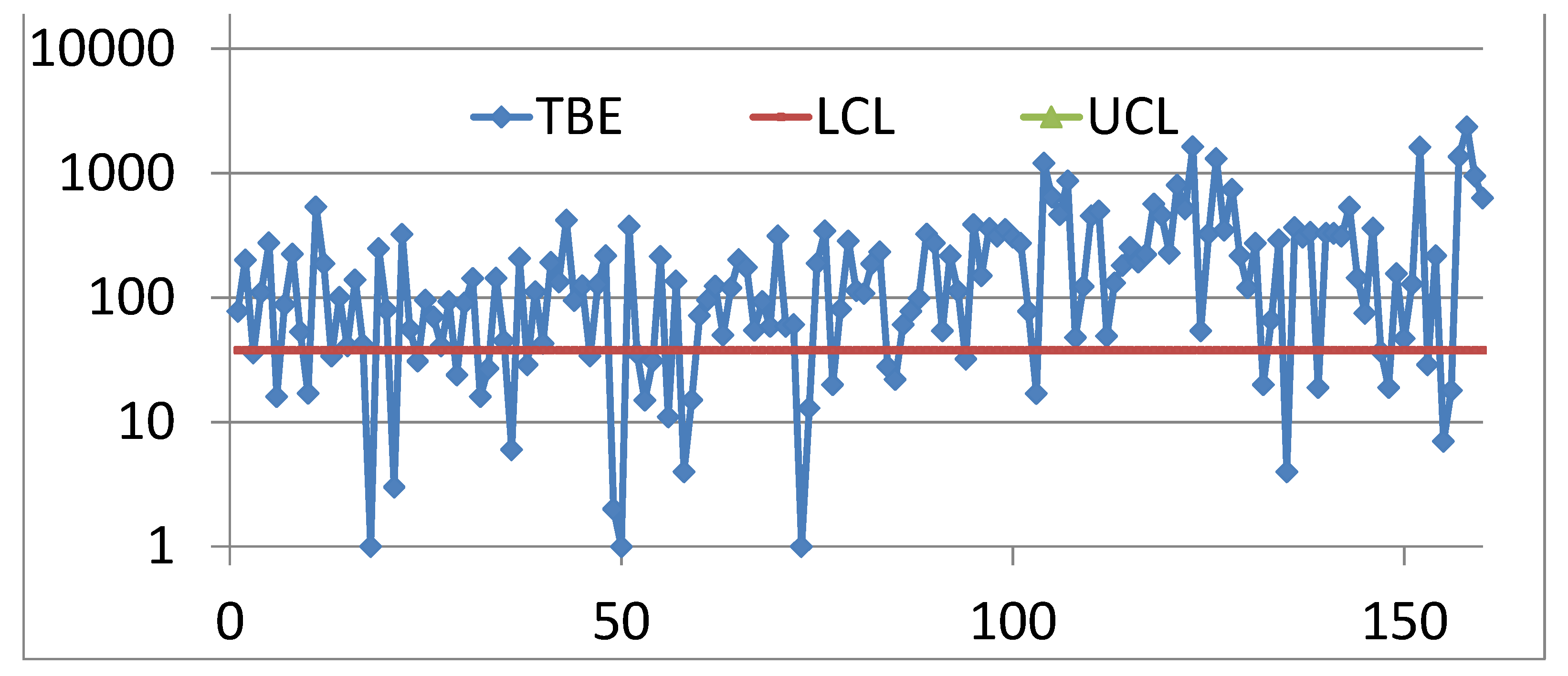

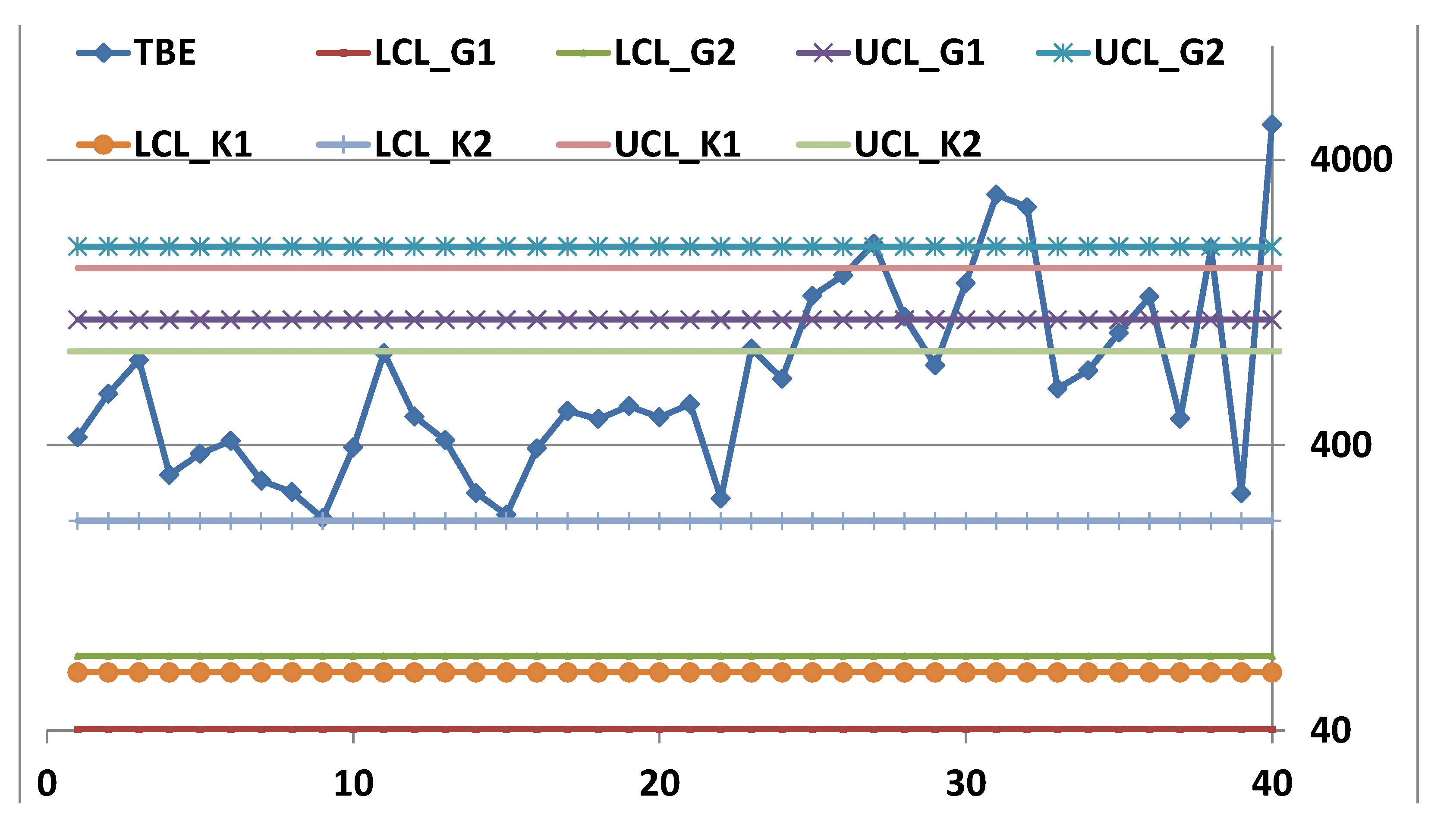

Excerpt 7. The CC of the 190 data from “Improved Shewhart-TypeCharts for Monitoring Times Between Events”, Journal of Quality Technology, 2016, (Kumar, Chakraborti et al): the first 30 are used to find the Control Limits for the other 40 t4 (time between “4 failures”: 4*40=160).

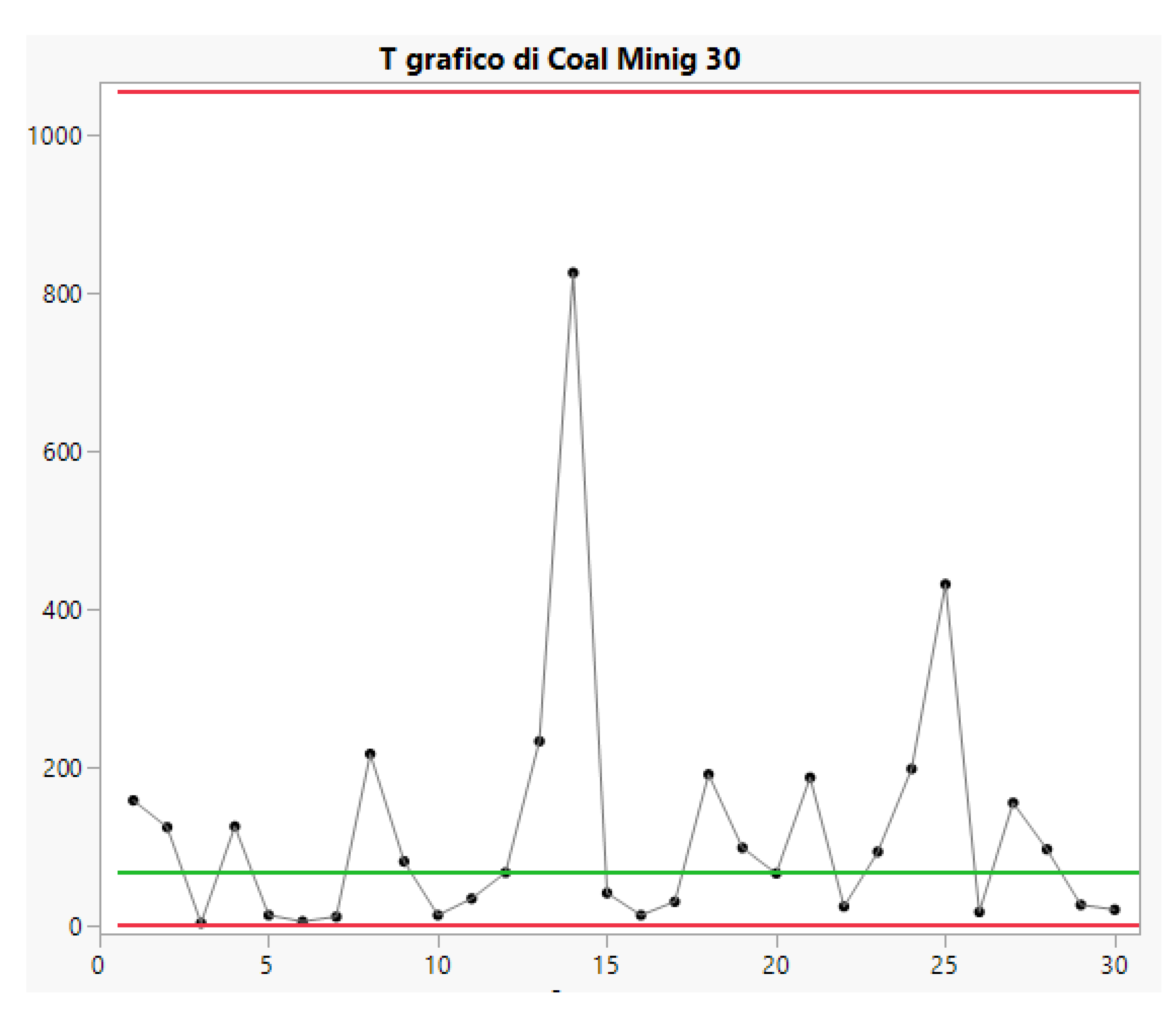

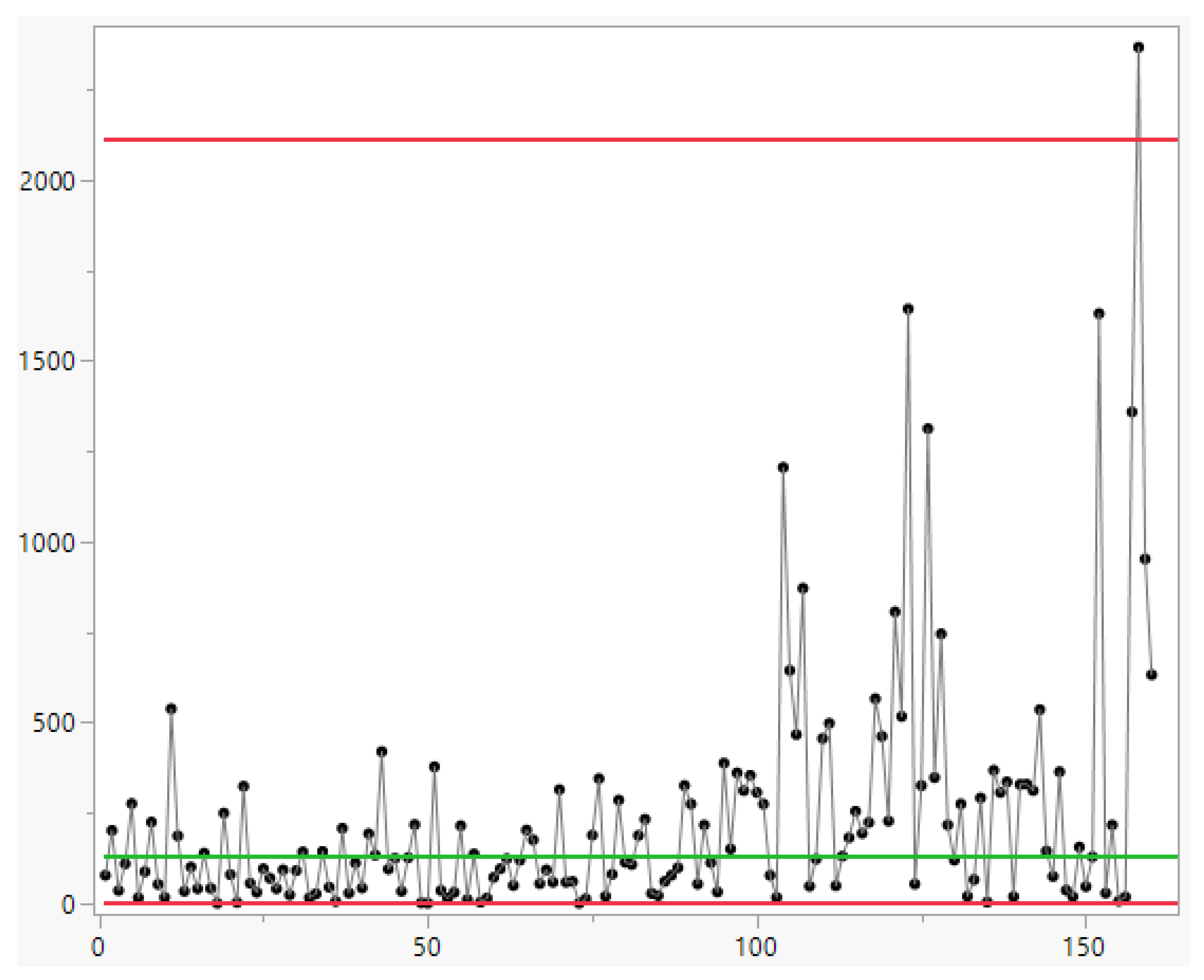

Excerpt 8. The CC of the 190 data [named by the authors “

Figure 7. ARL-unbiased exponential chart for the coal mining data”] from “Design of exponential control charts using a sequential sampling scheme”,

IIE Transactions, (Zhang et al., 2006) [the first 30 data are used to find the Control Limits].

Notice that the authors Zhang et al. and Kumar, Chakraborti et al. find different Control Limits to be used for monitoring the same process: a very interesting situation; the reason is that they use “different” statistics in Phase II. The results are in the excerpts 7 and 8.

For exponentially distributed data (12) becomes (13) [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33], k=1, with CL=

The endpoints of the CI=-------- are the Control Limits of the I-CC_TBE.

This is the right method to extract the “true” complete information contained in the sample (see the

Figure 9).

The

Figure 9 is justified by the Theory [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33] and is related to the formulae [(12), (13) for k=1], for the I-CC_TBE charts.

Remember the book Meeker et al., “Statistical Intervals: A Guide for Practitioners and Researchers”, John Wiley & Sons (2017): the authors use the same ideas of FG; the only difference is that FG invented 30 years before, at least.

Compare the formulae [(13), for k=1], theoretically derived with a sound Theory [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33], with the ones in the Excerpt [in the

Appendix C (a small sample from the “

Garden … [

24]”)] and notice that the two Minitab authors (Santiago&Smith) use the “empirical mean

” in place of the

in the

Figure 1: it is the

same trick of replacing to the mean

μ which is valid for the Normal distributed data only; e.g., see the formulae (1)!

Analysing the first 30 data of the two articles (Zhang et al. and Kumar, Chakraborti et al.) we get a total =3568 days and a mean /30=118.9 days; notice that it is rather different from the value 123 computed by (Kumar, Chakraborti et al.). Fixing α=0.0027, with RIT we find the CI{72.6--------} for the parameter , and the Control Limits LCL=18.0 days and UCL=88039.3 days.

Compare these with the LCLZhang=0.268 and UCLZhang=1013.9 (Zhang et al., 2006) and the “LCLKumar=63.95, UCLKumar=1669.28 with Centre_LineKumar=451.79” (Kumar, Chakraborti et al., for the t4-chart).

Quite big differences… with profound consequences on the decision on the states IC or OOC of the process; the

Figure 1, and the “scientific” formula (13) justify our findings.

Now we try to explain why those authors (Zhang et al. and Kumar, Chakraborti et al.) got their results.

In Zhang et al. (“Design of exponential control charts using a sequential sampling scheme”, IIE Transactions); at page 1107, we find the values Lu and Uu versus LCLZhang and UCLZhang

We do not know the cause of the “little” difference.

The interesting point is that with these Control Limits the Process “appears” IC (In Control), for the first m=30 observations, Phase I; see the excerpt 11.

So, one is induced to think that the mean /30=118.9 days can be used to find the λ0=1/118.9 for using the Control Limits in the Phase II (the next 160 data) (see the excerpt 12, with the words “plugging into …”).

Notice that the formulae in excerpt 9 are very similar to those in

Appendix C (related to [

24])”.

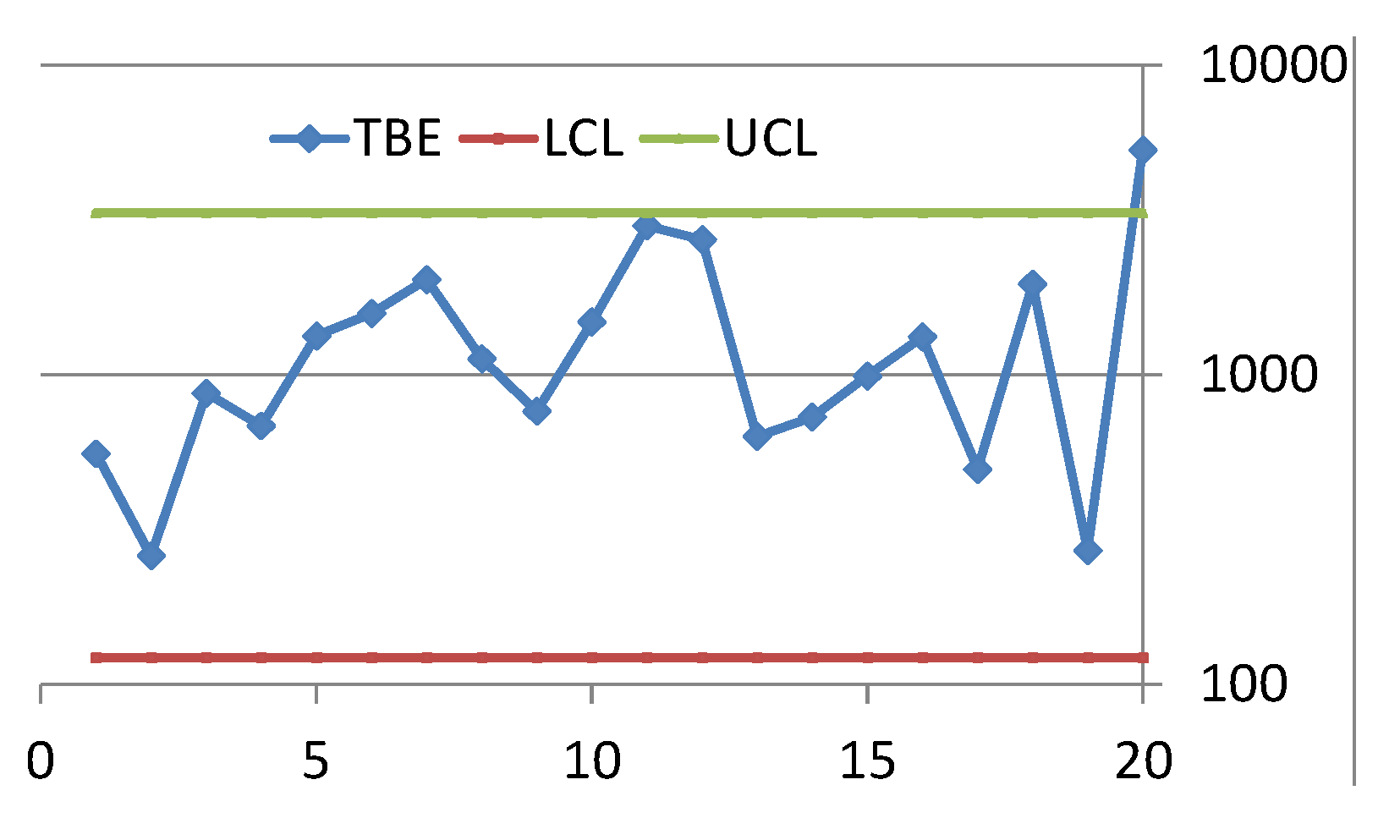

This fact generates an IC which is not real. See the

Figure 9.

The analysis of the first 30 data show that three possible distributions can be considered, using Minitab 21: Weibull, Gamma, and Exponential; since the Weibull is acceptable, we could use it. See the

Table 2.

α=0.0027, α*=0.00372, γα*=1.2927.

Excerpt 9. Formulae for the Control Limits for the first 30 data, IIE Transactions, (Zhang et al., 2006).

1000.

Anyway, for comparison with Zhang et al., 2006, we use the exponential distribution, which is not the “best” to be considered: as you can see the Process is OOC, with 7 points below the LCL.

Therefore, these data should be discarded for the computation of λ0.

Hence, the Control Limits (Zhang et al., 2006), based on the estimate “assumed as true” λ0=0.0081

cannot be used for the next 160 data.

Is the statement (assumption!) “… first m=30 observations to be from the in-control process…” sound?

NO!

By formulae (13) we find the

Figure 9 that proves that the process is OOC.

Using the formulae in the Excerpt 9, those authors do not extract the maximum information from the data in the Process Control.

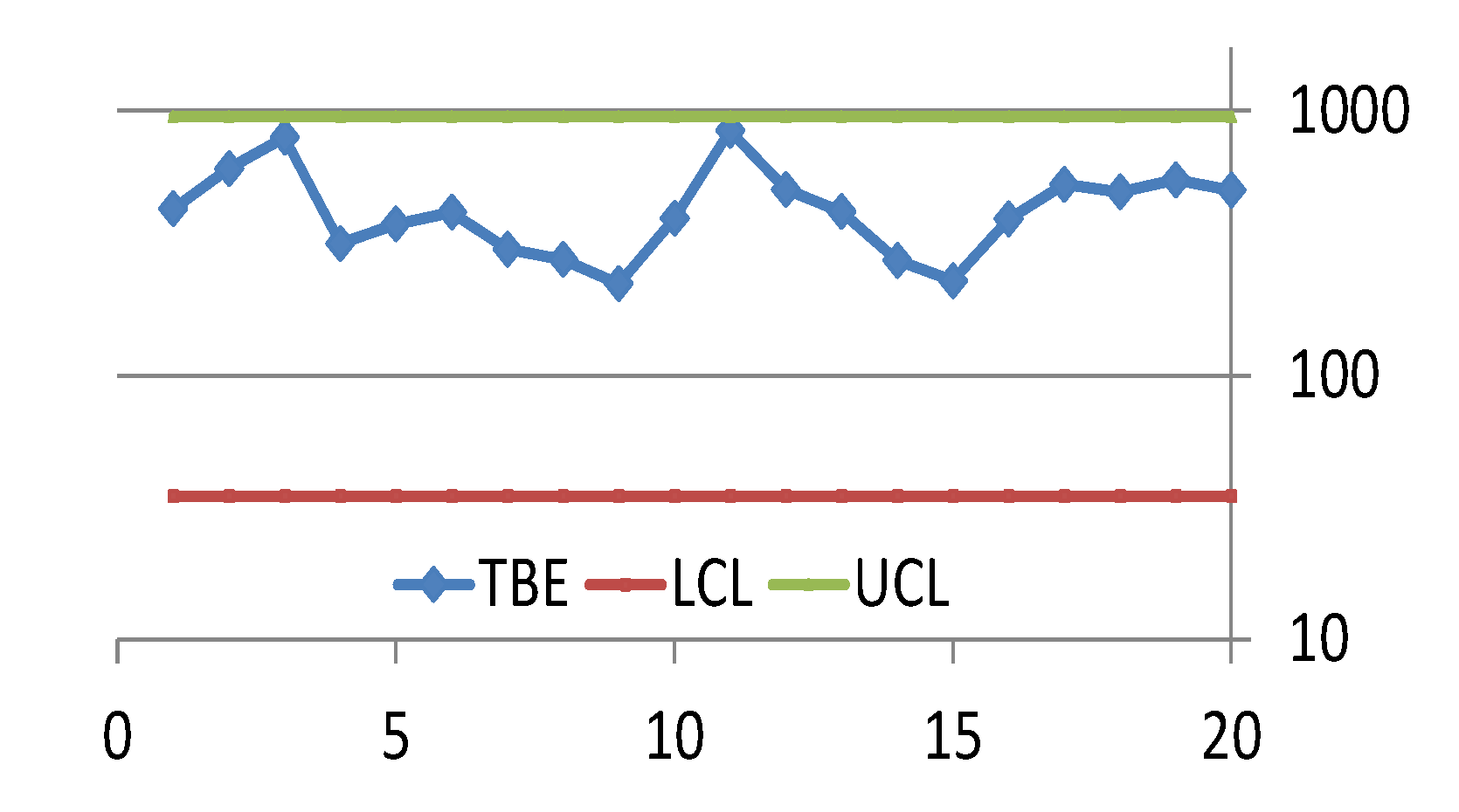

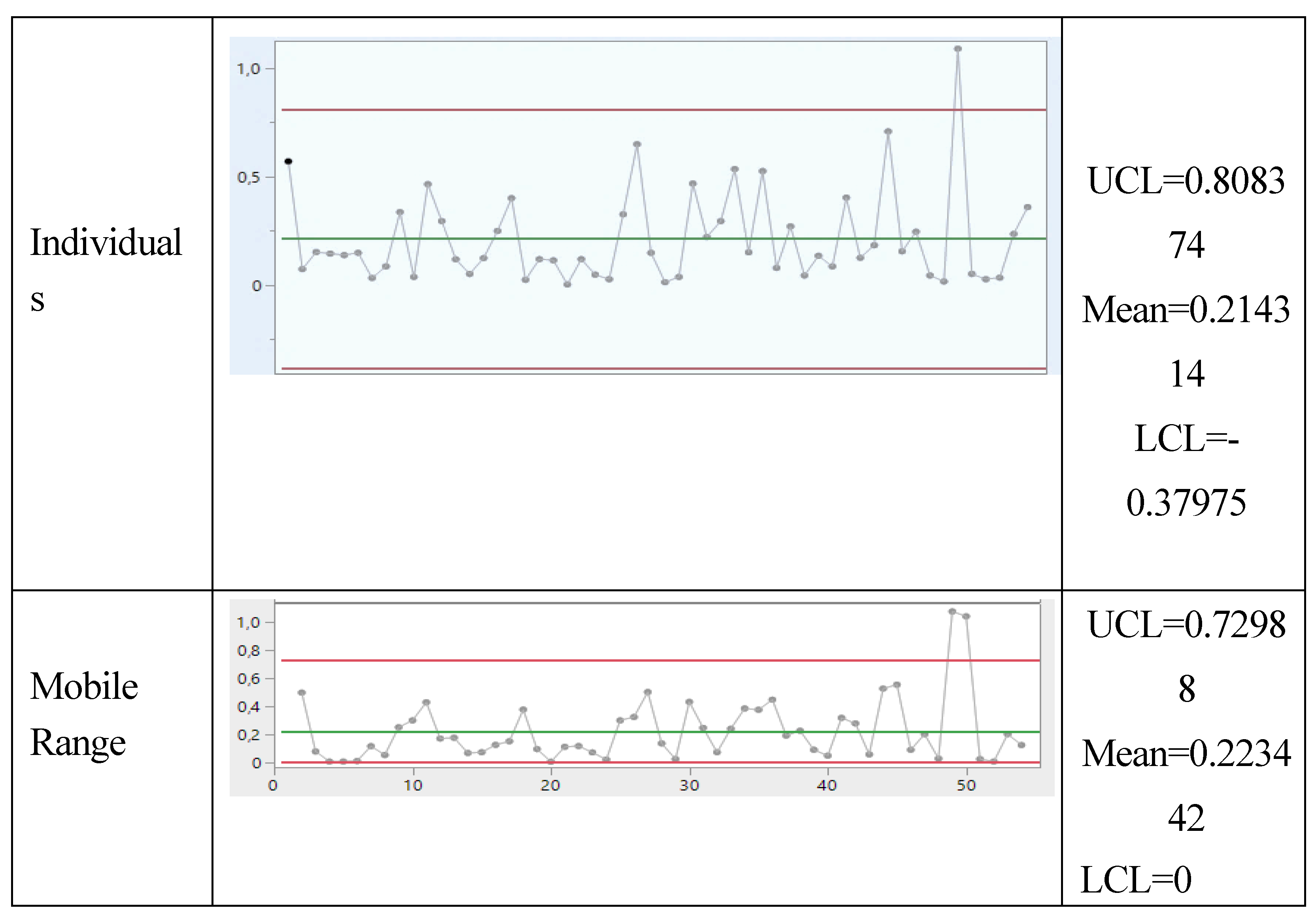

Before ending this section, let’s see what MINITAB, which use the ideas of Santiago & Smith, provides us in Phase I (

Figure 7a)

Notice that JMP (using the ideas of Santiago & Smith), provides us in Phase I the same type of information (

Figure 7b)

For the software Minitab, the process is IC, the same as Zhang et al. and Kumar et al.; same result could have been found by JMP (

Appendix B) and SAS, and all the authors in the “

Garden [

24]”…

3.2. ControlCharts for TBE Data. Phase II Analysis

We saw in the previous section what usually it is done during the Phase I of the application of CCs: estimation of the mean and standard deviation; later, their values are assumed as “true known” parameters of the data distribution, in view of the Phase II.

In particular, for TBE individual data the exponential distribution is assumed with a known parameter λ0 or θ0.

We consider now what it is done during the Phase II of the application of CCs for TBE data individual exponentially distributed.

We go on with the paper “Improved Shewhart-TypeCharts for ….”, Journal of Quality Technology, 2016, (Kumar, Chakraborti et al. with various presence in the “Garden …”) who analysed the Jarret data. In their paper we read:

Thus we focus on Shewhart-type TBE charts and try to improve their performance. The process is said to be in-control (IC) when λ=λ0, where λ0 is the given (known) or specified value of the failure rate. It should be noted here that when λ0 is not known from previous knowledge, it has to be estimated from a preliminary IC sample. In the sequel, we assume that λ0 is known or that it has been estimated from a (sufficiently) large Phase I sample. Omissis….. Therefore, following Kumar and Chakraborti (2014), the UCL and LCL given in (2) can be more conveniently rewritten

Excerpt 10. From “Improved … Monitoring Times Between Events”, J. Quality Technology, ‘16.

They combining 4 data to generate a t4 chart giving the formulae in the excerpt 10 (with r in place of 4; notice the authors mentioned… ).

Notice the formulae: the mentioned authors provide

their LCL and UCL which are actually the Probability Limits L and U of the Probability Interval (PI) and NOT the Control Limits of the Control Chart, as it is easily seen By using the Theory of CIs (

Figure 1 and

Figure 5).

All the Jarret data [30+40 t4] are very interesting for our analysis; we recap the two important points, given by the authors (Chakraborti et al.):

… first m=30 observations to be from the in-control process, from which we estimate … the mean TBE approximately, 123 days; we name it θ0.

… we apply the t4-chart… Thus, … converted by accumulating a set of four consecutive failure times … the times until the fourth failure, used for monitoring the process to detect a change in the mean TBE.

The 3 authors (Chakraborti et al.) state: “… the control limits … t4-chart are seen to be equal to LCL=63.95, UCL=1669.28 with CL (Centre Line)=451.79”, named by them “ARL-unbiased {1/1, 1/1}”.

The 3 authors (Chakraborti et al.) state also: “… the control limits … t4-chart are seen to be equal to LCL=217.13, UCL=852.92 with CL (Centre Line)=451.79”, named by them “ARL-unbiased {M:3/4, M:3/4}”.

Dropping out the OOC data (from the first 30 observations), in Phase I, with RIT, we find that now the process is IC: the distribution fitting the remaining data is the Weibull with parameters η=140.6 days and β=1.39; since the CI of the shape parameter is 0.98-----2.15, with CL=90%, we can assume β=1 (exponential with θ=127.9); therefore, we have the “true” LCL=18.6, quite different from the LCLs of the authors (Chakraborti et al.).

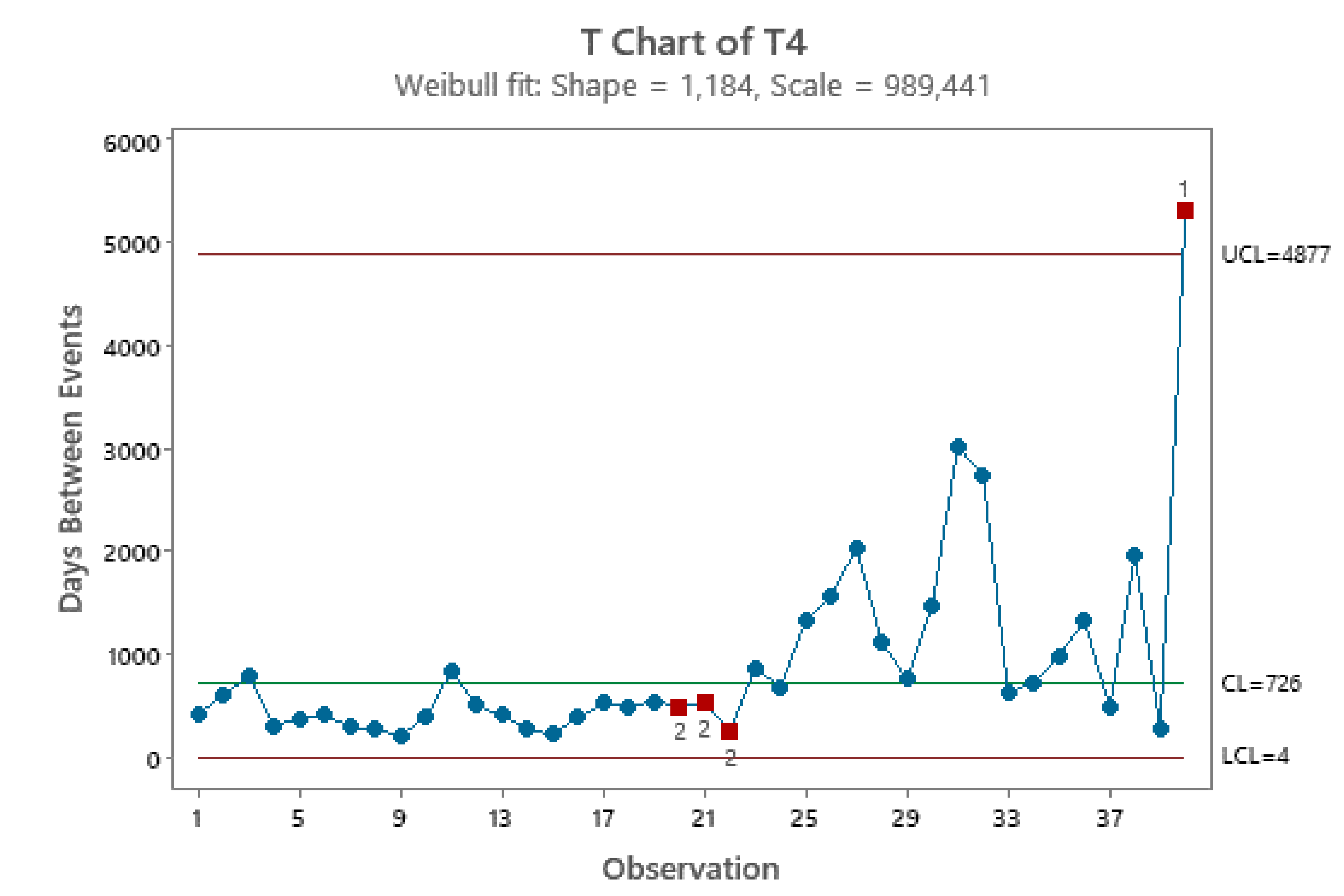

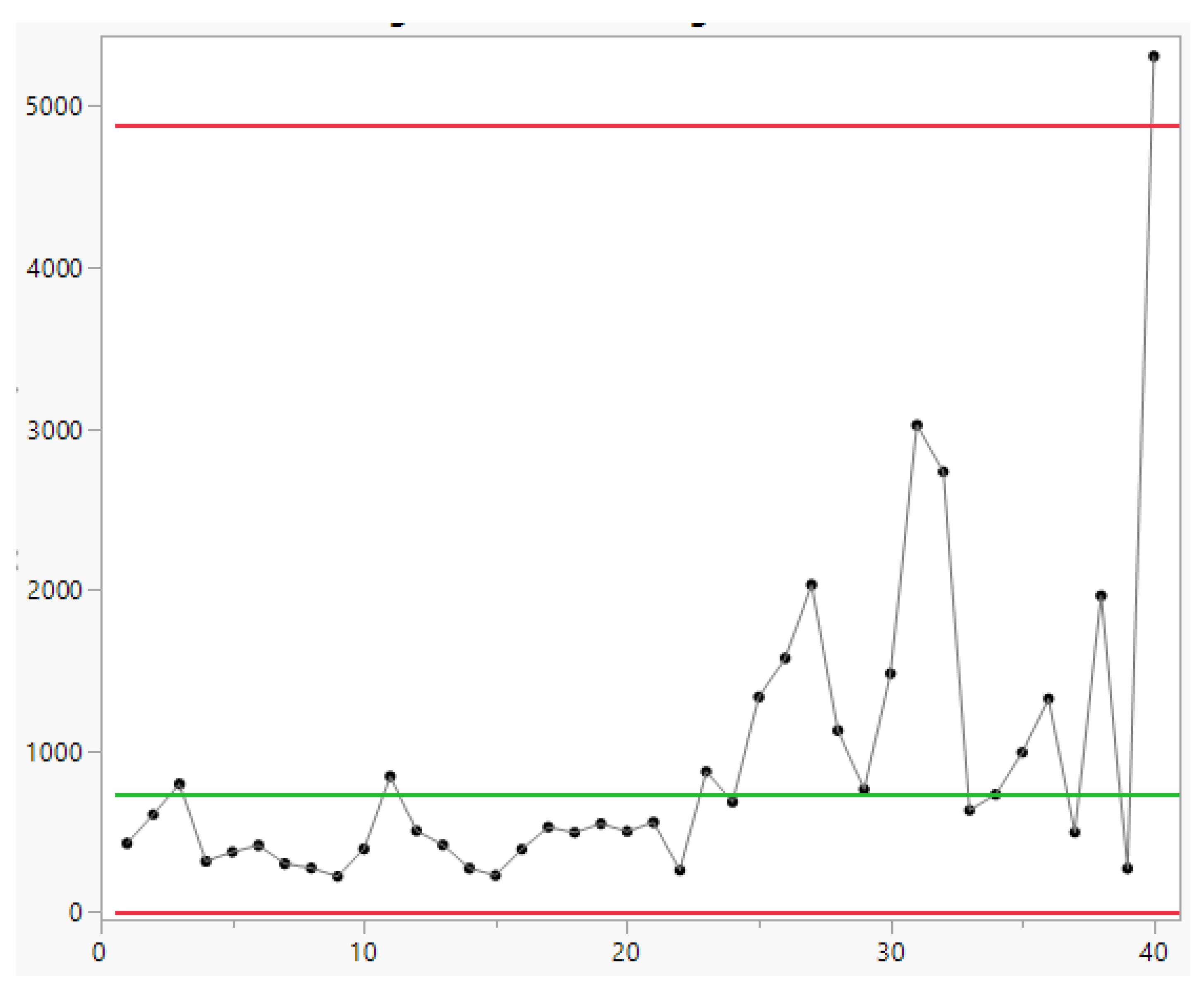

Considering the

40 t4 data, the distribution fitting the data is the Weibull with parameters η=990.2 days and β=1.18; since the 1∈CI of the shape parameter, with CL=90%, we can assume β=1 (exponential with θ=924.5); therefore, we have the “true” LCL=72.9 and UCL=1987, quite different from the Control Limits of the authors (Kumar, Chakraborti et al.): hence there is a profound consequence on the analysis of the

t4-chart; see the

Figure 12.

with

Excerpt 11. From “Improved … Monitoring Times Between Events”, J. Quality Technology, ‘16.

Considering, on the contrary, the value θ=127.9 from the

first [<30]

INDIVIDUAL observations of the IC process, transformed into the one for the

t4 chart, we have the “true” LCL=40.38 and UCL=1100.37; so, we have 4 LCLs and 4 UCLs (see

Figure 12).

The 3 authors (Kumar, Chakraborti et al.) show the formulae for the Control Limits (excerpt 11):

Now we face a problem: in which way could the 3 authors (Kumar, Chakraborti et al.) compute their Control Limits from the individual first m=30 observations?

FG (in spite of excerpt 11) did not find the way: is θ0=1/λ0 the value estimated from the first m=30 observations? He suspects that they used a trick (not shown): they use the fist 30 data to find θ0=123 days (from the total t0 of days in the Phase I) and then, they consider the total as though it were 4t0, i.e. 30 t4, to find LCL and UCL for the t4-chart … We did it, but we could not find them…

Doing that, Chakraborti et al. missed the fact that the process, in the individual first m=30 observations was OOC and they should not use the ″λ0 specified value of the failure rate, that has to be estimated from a preliminary IC sample.″

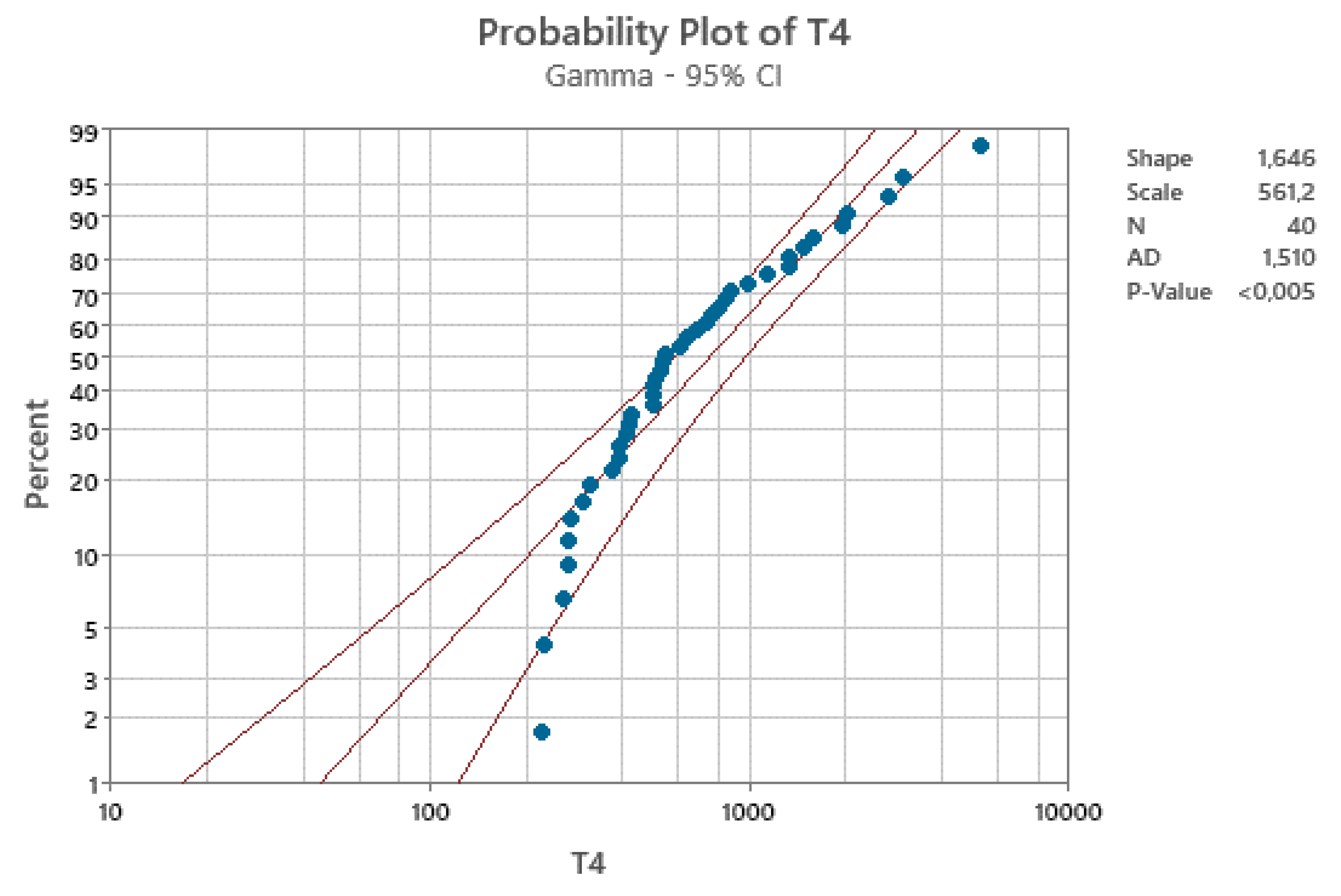

Since the data are assumed (by the 3 authors) Exponentially distributed it follows from the Theory that “… by accumulating a set of four consecutive failure times (times until the fourth failure)…” we should find the t4 data (determinations of the RV T4) Erlang distributed. Since k=4 we could expect that the CLT could apply and find that the 40 t4 data (determinations of the 40 RV T4) follow “approximately” the Normal distribution.

Considering the 40 t

4 data and searching for the distribution, we are disillusioned: the distributions Normal, Lognormal, Exponential, Gamma, Smallest Extreme, Largest Extreme, Logistic, Loglogistic do not fit the data; only the Weibull, and the Box-Cox and Johnson transformations seem adequate… See the Gamma (Erlang) fitting in the

Figure 8.

Therefore, the authors formulae for the Control Limits are inadequate in three ways, because

the gamma (Erlang) distribution does not apply, with CL=95%

then, the formulae in the excerpt 11 cannot be applied.

the formulae, in their paper,

and are generated by the confusion (of the authors) between LCL and L and UCL and U, as you can see in the

Figure 9, based on the non-applicable Gamma distribution; you see the vertical line intercepting the two probability lines in the points L and U such that

and versus the horizontal line, at

, intercepting the two lines at LCL and UCL.

It is clear that the two intervals, L

-----U and LCL

-----UCL, are

different and have

different definitions, meaning and length, through the Theory [

6,

7,

8,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36]. Notice, in the

Figure 9, the logarithmic scale for both axes (to have readable intervals).

It should be noted that we drew two horizontal lines, one at (the experimental mean) and the other at (the assumed known mean) to show the BIG difference between the interception points: we showed the TRUE LCL and UCL; the reader can guess that the WRONG Control Limits (not shown in the figure) have quite different values from the TRUE Control Limits.

and at ….

The reader is humbly asked to be very attentive in the analysis of the

Figure 9: FG thanks him!

Using the original 160 data, divided in 40 samples of size 4, we could compare the estimates with those found by the 40 t

4 (in the paper “

Improved … for Monitoring TBE”,

Journal of Quality Technology, 2016”); you see them in the

Table 3.

Notice that the

Figure 10a shows the same behaviour as the Phase I figure; it would be interesting to understand IF, with that, the authors would have been able to find an ARL=370: the process is Out Of Control both considering the

first individual 30 data and the last individual 160 data ….

How many OOC are in the Jarret data?

Analysing the 40 t4 data with Minitab (which uses the Santiago&Smith formulae,

Appendix C) we get

Figure 11a, and with JMP we get

Figure 11b;

See the authors Acknowledgement (in the paper)….

Notice that the OOC points in the

Figure 10 disappear when we plot the

40 t4, as you can see in the

Figure 12, where we draw 4 LCLs and 4 UCLs, from Kumar, Chakraborti et al. analysis and FG analysis (with RIT). We have the

Figure 12.

Notice theFigures 11a and 11b. Compare it with

Figure 12. What can we deduce from this analysis?

That the Method is fundamental to draw sound decisions.

Which is the best Method? Only the one which is Scientific, based on a sound Theory. Which one?

From the Theory [

6,

7,

8,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36] we know that we must assess the “true (to be used in the Phase II)” Control Limits from the data of an IC Process in the Phase I: therefore, only LCL_G1=40.38 and UCL_G1=1100.37 are the Scientific Control Limits; you can compare with the others in

Figure 12.

From

Figure 12 we see that the first

20 t4 have a mean lower than the last

20 t4: the mean time between events increased with calendar time. We can assess that by computing the two mean values: their ratio is 3.18 and we can see if it is significant and we find that it is so with CL=0.9973 (0.0027 probability of being wrong).

See alsoFigures 13a and 13b.

FromFigures 11a, 11b, 12, 13a and 13b we saw that the mean time between explosions was changing with time: it became larger (improved); a method that should show better this behaviour is the EWMA Control Chart. We do not analyse this point; also, for this chart there is the problem of the confusion between the intervals L-------U and LCL-------UCL.

5. Conclusions

With our figures (and the

Appendix C, that is a short extract from the “

Garden … [

24]”) we humbly ask the readers to look at the references [1-57] and find how much the author has been fond of Quality and Scientificness in the Quality (Statistics, Mathematics, Thermodynamics, …) Fields.

The errors, in the “

Garden … [

24]”, are caused by the lack of knowledge of sound statistical concepts about the properties of the parameters of the parent distribution generating the data, and the related Confidence Intervals. For the I-CC_TBE the computed Control Limits (which are actually the Confidence Intervals), in the literature are wrong due to lack of knowledge of the difference between Probability Intervals (PI) and Confidence Intervals (CI); see the

Figure 17 (remembering also the

Figure 14 and

Figure 1). Therefore, the consequent decisions about Process IC and OOC are wrong.

We saw that RIT is able to solve vario[1–57us problems in the estimation (and Confidence Interval evaluation) of the parameters of distributions for ControlCharts. The basics of RIT have been given.

We could have shown many other cases (from papers not mentioned here, that you can find in [

22,

23,

24]) where errors were present due to the lack of knowledge of RIT and sound statistical ideas.

Following the scientific ideas of Galileo Galilei, the author many times tried to compel several scholars to be scientific (Galetto 1981-2025). Only Juran appreciated the author’s ideas when he mentioned the paper “Quality of methods for quality is important” at the plenary session of EOQC Conference, Vienna. [

1]

For the control charts, it came out that RIT proved that the TCharts, for rare events and TBE (Time Between Events), used in the software Minitab, SixPack, JMP or SAS are wrong. So doing the author increased the h-index of the mentioned authors who published wrong papers.

RIT allows the scholars (managers, students, professors) to find sound methods also for the ideas shown by Wheeler in Quality Digest documents.

We informed the authors and the Journals who published wrong papers by writing various letters to the Editors…: no “Corrective Action”, a basic activity for Quality has been carried out by them so far. The same happened for Minitab Management. We attended a JMP forum in the JMP User Community and informed them that their “ControlCharts for Rare Events” were wrong: they preferred to stop the discussion, instead to acknowledge the JMP faults [

56,

57].

So, dis-quality continues to be diffused people and people continue taking wrong decisions…

Deficiencies in products and methods generate huge cost of Dis-quality (poor quality) as highlighted by Deming and Juran. Any book and paper are products (providing methods): their wrong ideas and methods generate huge cost for the Companies using them. The methods given here provide the way to avoid such costs, especially when RIT gives the right way to deal with Preventive Maintenance (risks and costs), Spare Parts Management (cost of unavailability of systems and production losses), Inventory Management, cost of wrong analyses and decisions.

Figure 15.

Probability Intervals L-----U versus Confidence Intervals LCL-----UCL in ControlCharts.

Figure 15.

Probability Intervals L-----U versus Confidence Intervals LCL-----UCL in ControlCharts.

We think that we provided the readers with the belief that Quality of Methods for Quality is important.

The reader should remember the Deming’s statements and the ideas in [6-57].

Unfortunately, many authors do not know Scientifically the role (concept) of Confidence Intervals (

Appendix B) for Hypothesis Testing.

Therefore, they do not extract the maximum information form the data in the Process Control.

Control Charts are a means to test the hypothesis about the process states, H0={Process In Control} versus H1={Process Out Of Control}, with stated risk α=0.0027.

We have a big problem about Knowledge: sound Education is needed.

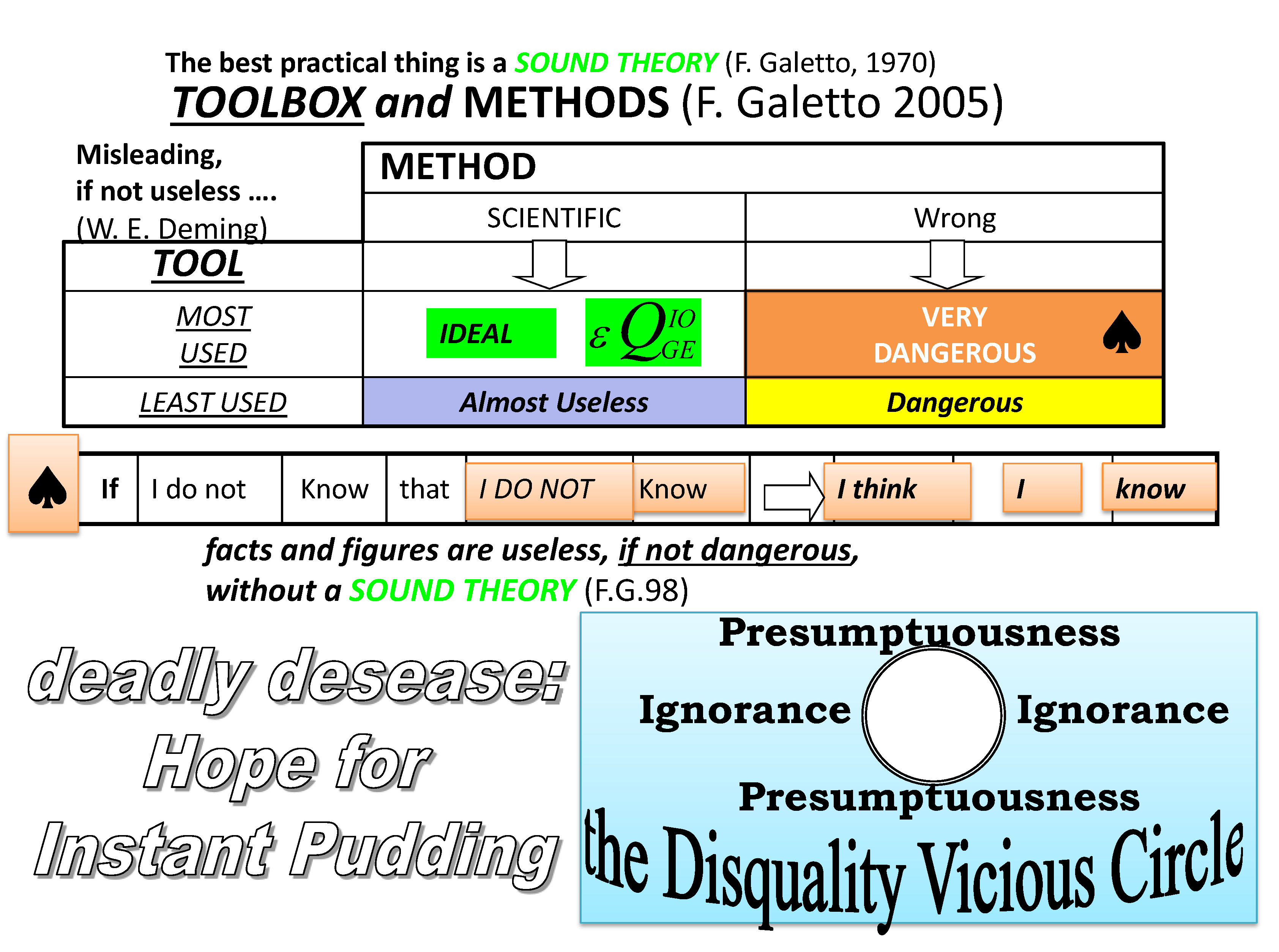

We think that the

Figure 16 conveys the fundamental ideas about the need of Theory for devising sound Methods, to be used in real applications in order to avoid the Dis-quality Vicious Circle.

Humbly, given our commitment to Quality and our long-life love for it [1-57], we would venture to quote Voltaire: [6–57

“It is dangerous to be right in matters on which the established men are wrong.” because “Many are destined to reason wrongly; others, not to reason at all; and others, to persecute those who do reason.” So, “The more often a stupidity is repeated, the more it gets the appearance of wisdom.” and “It is difficult to free fools from the chains they revere.”

Figure 16.

Knowledge versus Ignorance, in Tools and Methods.

Figure 16.

Knowledge versus Ignorance, in Tools and Methods.

Let’s hope that Logic and Truth prevail and allow our message to be understood (

Figure 15 and

Figure 16).

The objective of collecting and analysing data is to take the right action. The computations are merely a means to characterize the process behaviour. However, it is important to use the right Control Limits take the right action about the process states, i.e., In Control versus Out Of Control.

On July-August 2024 we again verified (through Six????? new downloaded papers) that the Pandemic Disease about the (wrong) Control Limits, that are actually the Probability Limits of the PI is still present (notice the Journals):

Zameer Abbas et al., (30 June 2024): “Efficient and distribution-free charts for monitoring the process location for individual observations”, Journal of Statistical Computation and Simulation,

Marcus B. Perry (June 2024) [University of Alabama 674 Citations] “Joint monitoring of location and scale for modern univariate processes”, Journal of Quality Technology.

E. Afuecheta et al., (

2023) “A compound exponential distribution with application to control charts”, Journal of Computational and Applied Mathematics [the authors use data of Santiago&Smith (

Appendix C) and erroneously find that the UTI process IC].

N. Kumar (2019), “Conditional analysis of Phase II exponential chart for monitoring times to an event”, Quality Technology & Quantitative Management

N. Kumar (2021), “Statistical design of phase II exponential chart with estimated parameters under the unconditional and conditional perspectives using exact distribution of median run length”, Quality Technology & Quantitative Management

S. Chakraborti et al. (2021), “Phase II exponential charts for monitoring time between events data: performance analysis using exact conditional average time to signal distribution”, Journal of Statistical Computation and Simulation

Other papers with the same problem have been downloaded from June 2024 to December 2024…

There will be any chance that the

Pandemic Disease ends? See the Excerpt 12:

notice the (ignorant) words “

plugging into …”. The only way out is

Knowledge… (

Figure 16):

Deming’s [

7,

8]

Profound Knowledge, Metanoia, Theory.

Excerpt 12. From “Conditional analysis of Phase II exponential chart… an event”, Q. Tech. & Quantitative Mgt, ’19.

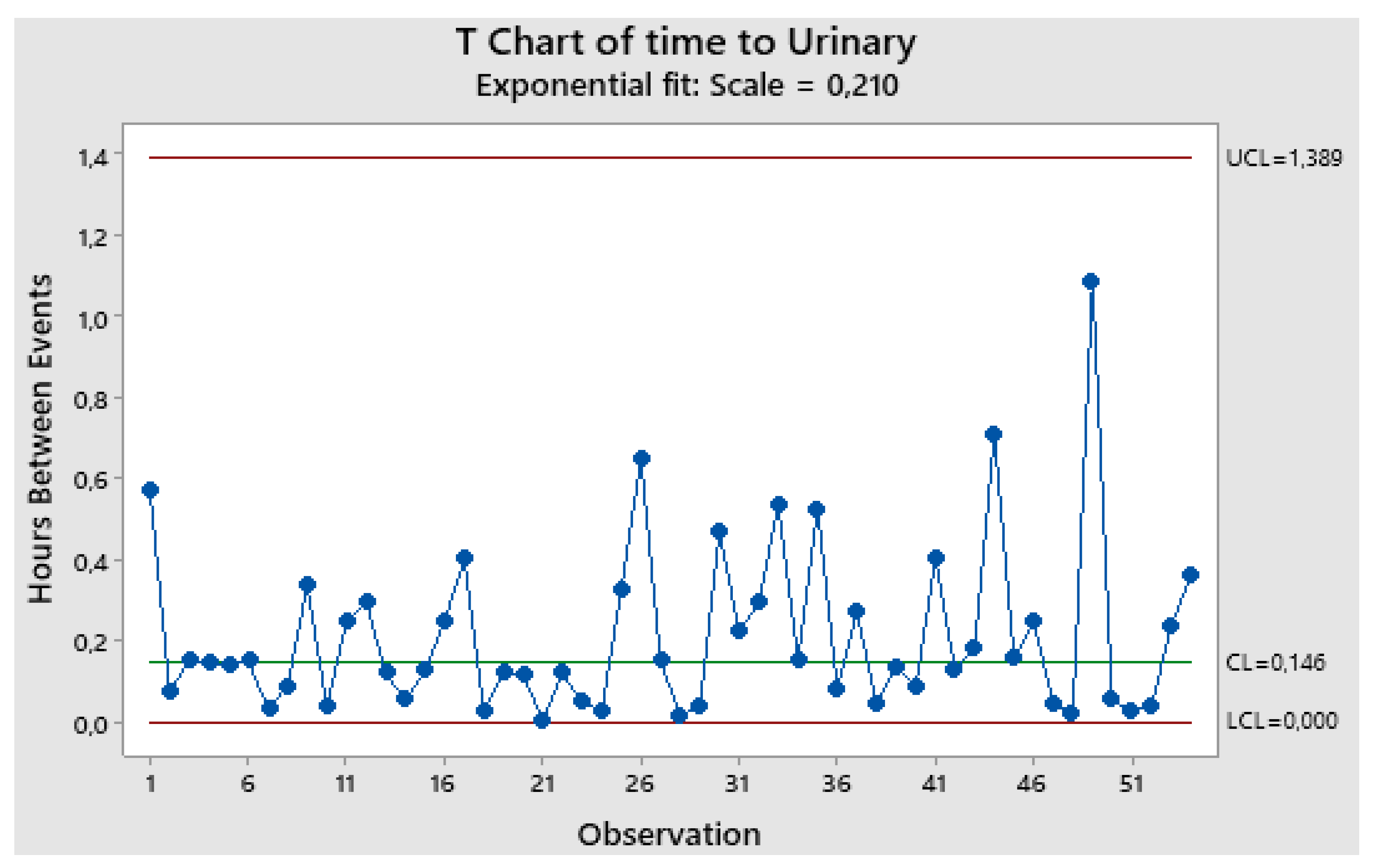

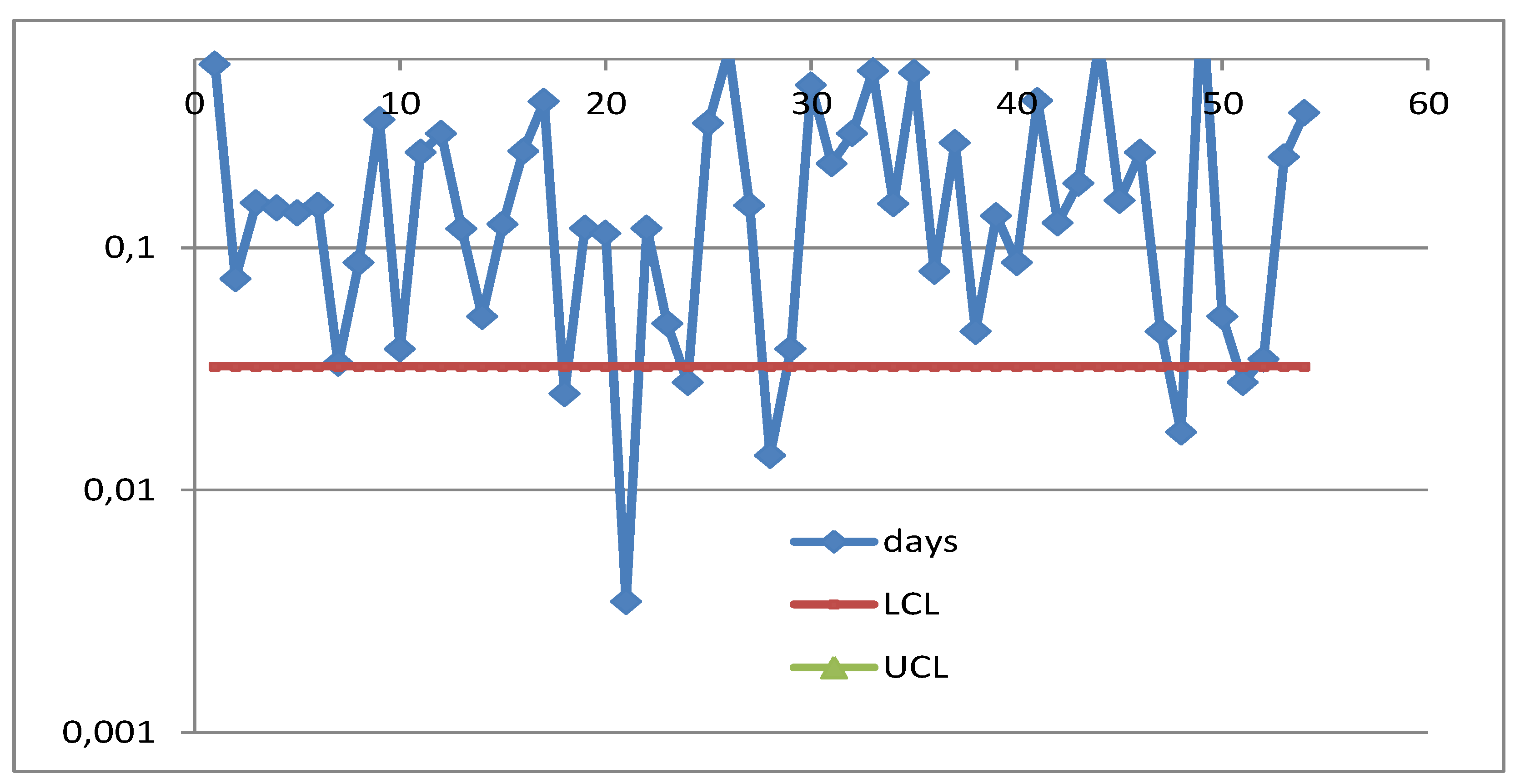

LCL=0.001

Notice the LCL, the Mean and the UCL of both charts.

Compute the mean of all the data and you find a different value: therefore, the mean in the charts is not the mean of the process!

If one analyses the data with Minitab, he finds the

Figure A3.

You see that now the UTI process is IC: notice the LCL, Mean and UCL.

A natural question arises: which of the three figures is correct?

Actually, they all are wrong, as you can see from the

Figure A4:

The author offered JMP to become a better statistical software provider by solving the flaw according to JMP advertising:

Our Purpose

Our purpose is to empower scientists and engineers via our statistical discovery software. That’s pretty straightforward, and it’s never wavered. Sometimes we work directly with the data explorers themselves, sometimes with their companies, and other times with colleges and universities so that the next generation of scientists and engineers will count on JMP by the time they enter the workforce.

Although our purpose is clearly connected to our software, it doesn’t end there. As an employer, JMP purposefully creates and maintains a culture of camaraderie that allows the personalities of our diverse and inclusive employee base to shine through. JMP is an equal opportunity employer.

And as inhabitants of this planet, we intentionally measure and work to mitigate our impact on the world. Explore our Data for Green program to see how we’re working to empower other organizations to make a difference too.

The catchphrase “corporate social responsibility” could be used for a lot of what we do for our employees, communities, education and the Earth. But starting with JMP founder John Sall, we just try to do the right thing.

No reaction … and therefore NO Corrective Action.

A Very Illuminating Case

We consider a case found in the paper (with 148 mentions) “

ControlCharts based on the Exponential distribution”,

Quality Engineering, March 2013, of Santiago&Smith, two experts of Minitab Inc. at that time. You find it mentioned in the “

Garden…” [

24] and in the

Appendix C.

This is important because we analysed the data with Minitab software and JMP software and we found astonishing results: the cause are the formulae .

The author knew that Minitab computes wrongly the Control Limits of the Individual Control Chart. He wanted to assess how the JMP Student Version would deal with them using the following 54 data analysed by Santiago&Smith in their paper; they are “Urinary Tract Infection (UTI) data collected in a hospital”; the distribution of the data is the Exponential.

Table A1.

UTI data (“ControlCharts based on the Exponential distribution”).

Table A1.

UTI data (“ControlCharts based on the Exponential distribution”).

| |

UTI |

|

UTI |

|

UTI |

|

UTI |

|

UTI |

|

UTI |

| 1 |

0.57014 |

11 |

0.46530 |

21 |

0.00347 |

31 |

0.22222 |

41 |

0.40347 |

51 |

0.02778 |

| 2 |

0.07431 |

12 |

0.29514 |

22 |

0.12014 |

32 |

0.29514 |

42 |

0.12639 |

52 |

0.03472 |

| 3 |

0.15278 |

13 |

0.11944 |

23 |

0.04861 |

33 |

0.53472 |

43 |

0.18403 |

53 |

0.23611 |

| 4 |

0.14583 |

14 |

0.05208 |

24 |

0.02778 |

34 |

0.15139 |

44 |

0.70833 |

54 |

0.35972 |

| 5 |

0.13889 |

15 |

0.12500 |

25 |

0.32639 |

35 |

0.52569 |

45 |

0.15625 |

|

|

| 6 |

0.14931 |

16 |

0.25000 |

26 |

0.64931 |

36 |

0.07986 |

46 |

0.24653 |

|

|

| 7 |

0.03333 |

17 |

0.40069 |

27 |

0.14931 |

37 |

0.27083 |

47 |

0.04514 |

|

|

| 8 |

0.08681 |

18 |

0.02500 |

28 |

0.01389 |

38 |

0.04514 |

48 |

0.01736 |

|

|

| 9 |

0.33681 |

19 |

0.12014 |

29 |

0.03819 |

39 |

0.13542 |

49 |

1.08889 |

|

|

| 10 |

0.03819 |

20 |

0.11458 |

30 |

0.46806 |

40 |

0.08681 |

50 |

0.05208 |

|

|

The analysis with JMP software, using the Rare Events Profiler, is in the

Figure A1.

NOTICE that JMP, for Rare Events, Exponentially distributed, in the

Figure A1, uses the Normal distribution! NONSENSE

It finds the UTI process OOC: both the charts, Individuals and Mobile Range are OOC.

The author informed the JMP User Community.

After various discussions, a member of the Staff (using the Exponential Distribution) provided the

Figure A2.

You see that, now (

Figure A2), the UTI process is IC: both the charts, Individuals and Mobile Range are IC; opposite decision than before (

Figure A1), by the same JMP software (but with two different methods: the first is the standard method, while the second was devised by a JMP Staff member).

The Statistical Hypotheses and the Related Risks

We define as statistical hypothesis a statement about a population parameter (e.g. the ′′true′′ mean, the ′′true′′ shape, the ′′true′′ variance, the ′′true′′ reliability, the ′′true′′ failure rate, …). The set of all the possible values of the parameter is called the parameter space Θ. The goal of a hypothesis test is to decide, based on a sample drawn from the population, which value hypothesed for the population parameter of the parameter space Θ can be accepted as true. Remember: nobody knows the truth…

Generally, two competitive hypotheses are defined, the null hypothesis H0 and the alternative hypothesis H1.

If θ denotes the population parameter, the general form of the null hypothesis is H0: θ∈Θ0 versus the alternative hypothesis H1: θ∈Θ1, where Θ0 is a subset of the parameter space Θ and Θ1 a subset disjoint from Θ0. If the set Θ0={θ0, a single value} the null hypothesis H0 is called simple; on the contrary, the null hypothesis H0 is called composite. If the set Θ1={θ1, a single value} the alternative hypothesis H1 is called simple; on the contrary, the alternative hypothesis H1 is called composite.

In a hypothesis testing problem, after observing the sample (and getting the empirical sample of the data D) the experimenter (the Manager, the Researcher, the Scholar) must decide either to «accept» H0 as true or to reject H0 as false and then decide, on the opposite, that H1 is true.

Let’s make an example: let the reliability goal be [θ being the MTTF]; we ask the data D, from the reliability test to confirm the goal we set. Nobody knows the reality; otherwise, there would be no need of any test.

The test data D are the determinations of the random variables related to the items under test; it can happen then that the data, after their elaboration, provide us with an estimate far from (and therefore they induce us to decide that the goal has not been achieved).

Generally, in the case of reliability test, the reliability goal to be achieved is called null hypothesis .

The hypotheses are classified in various manners, such as (and some suitable combinations)

Simple Hypothesis: it specifies completely the distribution (probabilistic model) and the values of the parameters of the distribution of the Random Variable under consideration

Composite Hypothesis: it specifies completely the distribution (probabilistic model) BUT NOT the values of the parameters of the distribution of the Random Variable under consideration

a. Parametric Hypothesis: it specifies completely the distribution (probabilistic model) and the values (some or all) of the parameters of the distribution of the Random Variable under consideration

b. Non-parametric Hypothesis: it does not specify the distribution (probabilistic model) of the Random Variable under consideration

A hypothesis testing procedure (or simply a hypothesis test) is a rule (decision criterion) that specifies

for which sample values the decision is made to «accept» H0 as true,

for which sample values H0 is rejected and then H1 is accepted as true.

based on managerial/Statistics which defines

to be used for decisions, with the stated risks: decision criterion.

The subset of the sample space for which H0 will be rejected is called rejection region (or critical region). The complement of the rejection region is called the acceptance region.

A hypothesis test of H0: θ∈Θ0 versus H1: θ∈Θ1, (Θ0∩Θ1=∅) might make one of two types of errors, traditionally named Type I Error and Type II Error; their probabilities are indicated as α and β.

Table B1. Statistical Hypotheses and risks.

If «actually» H0: θ∈Θ0 is true and the hypothesis test (the rule), due to the collected data, incorrectly decides to reject H0 then the test (and the Experimenter, the Manager, the Researcher, the Scholar who follow the rule) makes a Type I Error, whose probability is α. If, on the other hand, «actually» θ∈Θ1 but the test (the rule), due to the collected data, incorrectly decides to accept H0 then the test (and the Experimenter, the Manager, the Researcher, the Scholar who follow the rule) makes a Type II Error, whose probability is β.

These two different situations are depicted in the previous table (for simple parametric hypotheses).

Notice that when we decide to “accept the null hypothesis” in reality we use a short-hand statement saying that we do not have enough elements to state the contrary.

Suppose R is the rejection region for a test, based on a «statistic s(D)» (the formula to elaborate the sampled data D).

Then for H0: θ∈Θ0, the test makes a mistake if «s(D)∈R», so that the probability of a Type I Error is α=P(S(D)∈R) [S(D) is the random variable giving the result s(D)].

It is important the

power of the test 1-β, which is the probability of rejecting H

0 when

in reality H

0 is false

Therefore, the power function of a hypothesis test with rejection region R is the function of θ defined by β(θ)=P(S(D)∈R). The function 1-power function is often named the Operating Characteristic curve [OC curve].

A good test has power function near 1 for most θ∉Θ0 and, on the other hand, near 0 and for most θ∈Θ0.

From a managerial point of view, it is sound using powerful tests: a powerful test (finds the reality and) rejects what must be rejected.

It is obvious that we want that the test be the most powerful and therefore one must seek for the statistics which have the maximum power; it’s absolutely analogous to the search of efficient estimators.

We know that the competition of simple hypotheses can have a good property: the most powerful critical region [i.e. the rejection region found has the highest power 1-β(θ)=P(S(D)∉R) of H1 against H0, for any α (α sometimes is called size of the critical region)]; a theorem regarding the likelihood ratio proves that.

Let’s define the