Submitted:

17 December 2025

Posted:

18 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material and Growing Conditions

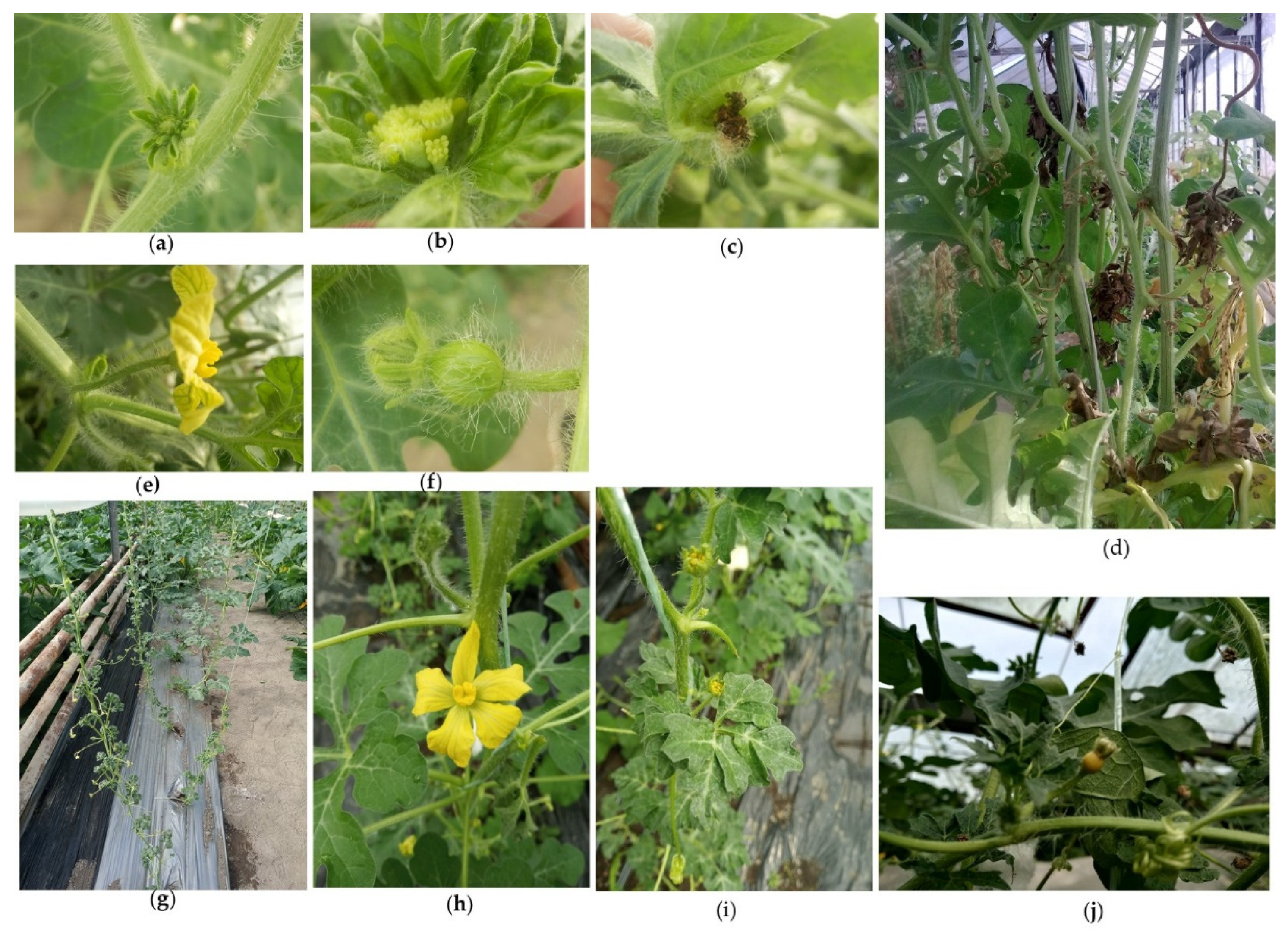

2.2. Phenotype Description

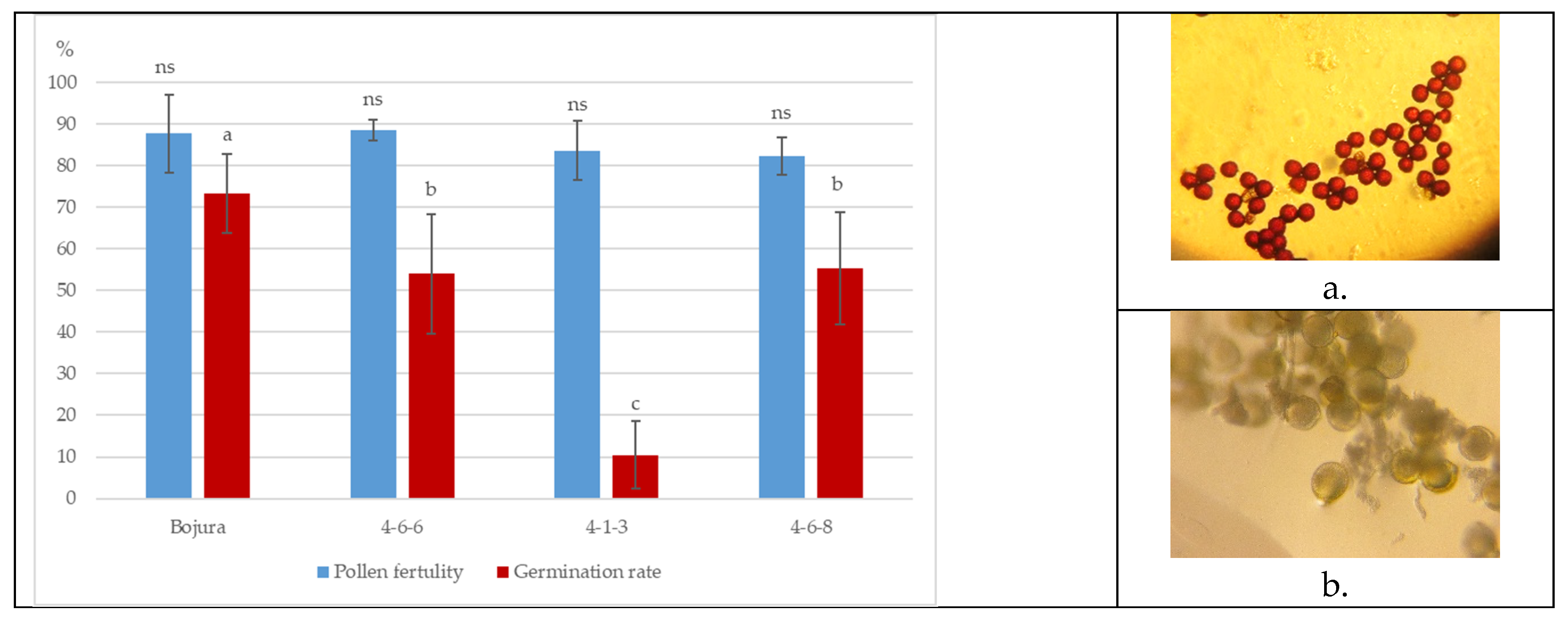

Pollen Fertility and Germination Rate

2.3. Probability of Occurrence of Mutations in a Collection of Watermelons and Determination of the Minimum Number of Plants to Obtain at Least One Mutant Plant

2.4. Experimental Design and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Screening a Watermelon Collection for Natural Mutants

3.2. Inheritance of Mutation

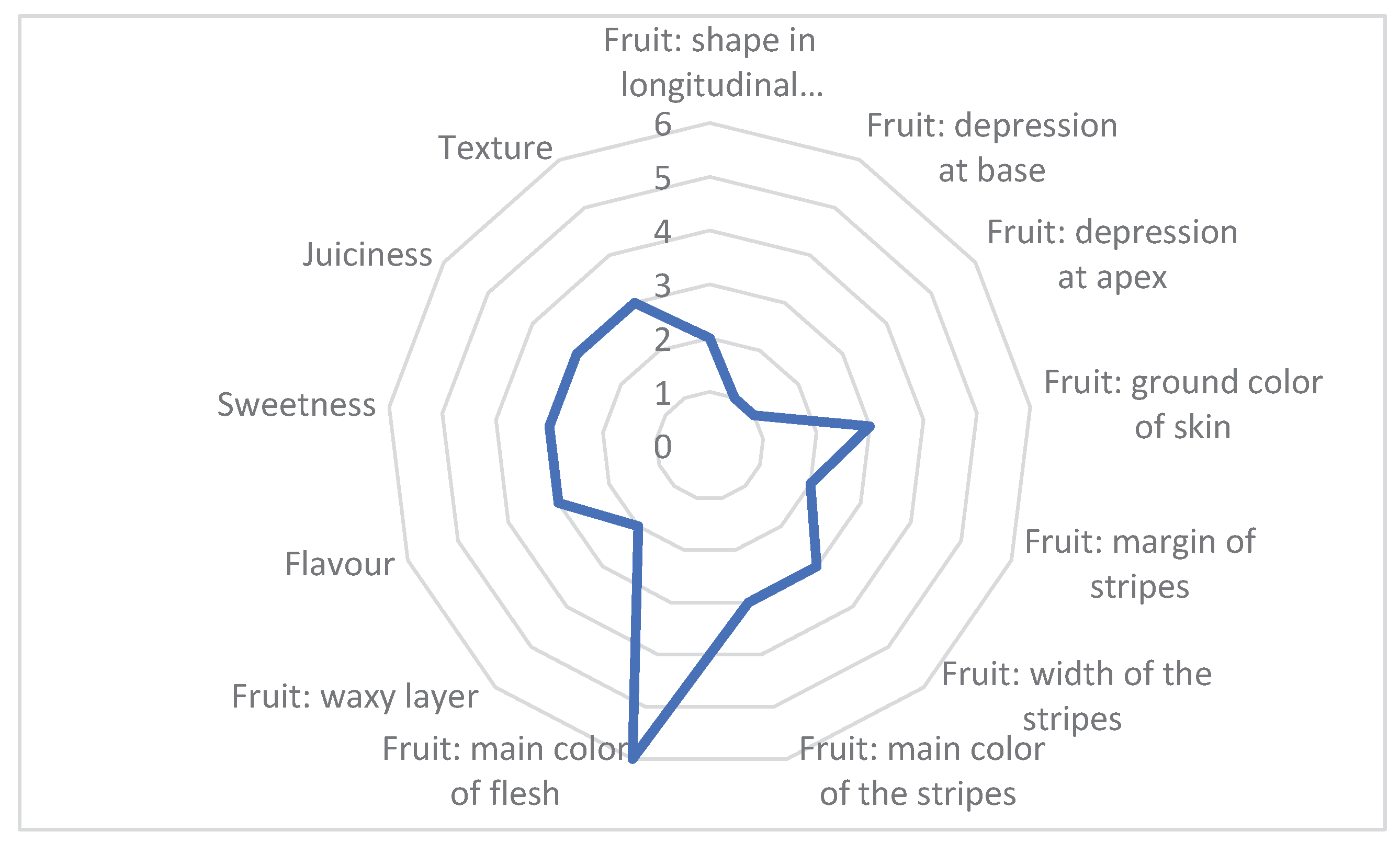

3.3. Phenotyping of Some Important Traits of cv. Concurrent

Pollen Fertility and Germination Rate

3.4. Probability of Mutation

4. Discussion

4.1. Screening a Watermelon Collection for Natural Mutants

4.2. Inheritance of Mutation

4.3. Phenotyping of Some Important Traits of cv. Concurrent

4.4. Probability of Mutation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Whitaker, T.; Davis, G. Cucurbits; Interscience Publishers, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Ene, C.O.; Ogbonna, P.E.; Agbo, C.U.; Chukwudi, U.P. Heterosis and combining ability in cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.). Inform. Process. Agric. 2019, 6, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napolitano, M.; Terzaroli, N.; Kashyap, S.; Russi, L.; Jones-Evans, E.; Albertini, E. Exploring Heterosis in Melon (Cucumis melo L.). Plants 2020, 9, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darrudi, R.; Nazeri, V.; Soltani, F.; Shokrpour, M.; Ercolano, M.R. Evaluation of combining ability in Cucurbita pepo L. and Cucurbita moschata Duchesne accessions for fruit and seed quantitative traits. J. Appl. Res. Med. Aromat. Plants 2018, 9, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, V.M. A marked male-sterile mutant in watermelon. Proc. Amer. Soc. Hort. Sci. 1962, 81, 498–505. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.P.; Wang, M. A genetic male-sterile (ms) watermelon from China. Cucurbit Genetics Coop. Rpt 1990, 13, 45–46. [Google Scholar]

- Dyutin, K.E.; Sokolov, S.D. Spontaneous mutant of watermelon with male sterility. Cytology and Genetics 1990, 24, 56–57. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, D.; Paek, K.; Hwang, J.; Park, H. Characterization of a New Male Sterile Mutant in Watermelon. Cucurbit Genetics Cooperative Report 2001, 24, 52–58. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, W.; Wu, D.; Yan, C.; Wu, D. Mapping and analysis of a novel genic male sterility gene in watermelon (Citrullus lanatus). Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 639431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Ding, Q.; Wei, B.; Yang, H. Transcriptome analysis of sterile and fertile floral buds from recessive genetic male sterility lines in watermelon (Citrullus lanatus L.). J. Plant Growth Regul. 2023, 42, 2800–2812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adıgüzel, P.; Solmaz, İ.; Karabıyık, Ş.; Sarı, N. Comparison on flower, fruit and seed characteristics of tetraploid and diploid watermelons (Citrullus lanatus Thunb. Matsum. & Nakai). Int. J. Agric. Environ. Food Sci. 2022, 6, 704–710. [Google Scholar]

- Kara, E.; Ta¸skın, H.; Karabıyık, ¸S.; Solmaz, ˙I.; Sarı, N.; Karaköy, T.; Baktemur, G. Are Cytological and Morphological Analyses Sufficient in Ploidy Determination of Watermelon Haploid Plants? Horticulturae 2024, 10, 818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijesinghea, S.A.E.C.; Evans, L.J.; Kirkland, L.; Rader, R. A global review of watermelon pollination biology and ecology: The increasing importance of seedless cultivars. Sci. Hortic. 2020, 271, 109493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Chang, J.; Li, J.; Lan, G.; Xuan, C.; Li, H.; Ma, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, J.; Tian, S.; Yuan, L.; Zhang, X. Disruption of the bHLH transcription factor Abnormal Tapetum 1 causes male sterility in watermelon. Hortic. Res. 2021, 8, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozanov, P. Breeding of male-sterile parental components for facilitating the production of hybrid seeds from melon. In Proceedings of the First Scientific Conference on Genetics and Breeding, Razgrad, Bulgaria, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Lecouviour, M.; Pitrat, M.; Risser, G. A Fifth Gene for Male Sterility in Cucumis melo. Cucurbit Genetics Cooperative Report 1990, 13, 34–35. [Google Scholar]

- Weng, Y.; Wehner, T.C. Cucumber Gene Catalog 2017. Cucurbit Genet. Coop. Rep. 2017, 39–40. [Google Scholar]

- Pitrat, M. Melon. In: Handbook of plant breeding. Vol. 1, Vegetables I: Asteraceae, Brassicaceae, Chenopodicaceae, and Cucurbitaceae. Ed. by Prohens J and Nuez F. Springer, 2008; p. 283-316.

- Li, Y.; Yang, H.; Yang, J.; Yang, D. A Apetalous Gynoecious Mutant in Watermelon. Cucurbit Genet. Coop. Rep. 2009, 31–32, 15–16. [Google Scholar]

- Xiantao, J.; Depei, L. Discovery of Watermelon Gynoecious Gene gy. Acta Hortic. Sin. 2007, 34, 141–142. [Google Scholar]

- UPOV Code: CTRLS_LAN, (Citrullus lanatus (Thunb.) Matsum. et Nakai), International union for the protection of new varieties of plants, Geneva, TG/142/5 Rev. Watermelon, 2013-03-20 + 2019-10-29.

- Lidanski, T. Statistical methods in biology and agriculture; Zemizdat: Sofia, Bulgaria, 1988; p. 375. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz, C.D. GENES - a software package for analysis in experimental statistics and quantitative genetics. Acta Sci Agron 2013, 35, 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonfack, L.B.; Foamouhoue, E.N.; Tchoutang, D.N.; Youmbi, E. Application of pesticide combinations on watermelon affects pollen viability, germination, and storage. J. App. Biol. Biotech. 2019, 7, 35–39. [Google Scholar]

- Dogimont, C. Gene List for Melon. Cucurbit Genet. Coop. Rep. 2011, 33-34, 104–133. [Google Scholar]

- Lozanov, P. Heterosis in watermelon, melon and squashes. In The Heterosis and Their Use in Vegetable Production; Publisher house Hristo G. Danov: Plovdiv, Bulgaria, 1974; pp. 254–322. [Google Scholar]

- Lecouviour, M.; Pitrat, M.; Risser, G. A fifth gene for male sterility in Cucumis melo. Cucurbit Genet. Coop. Rep. 1990, 13, 34–35. [Google Scholar]

- Wehner, T.C. Overview of the genes of watermelon, Cucurbitaceae 2008, Proceedings of the IXth EUCARPIA meeting on genetics and breeding of Cucurbitaceae, (Pitrat M, ed), INRA, Avignon (France), May 21-24th, 2008.

- Ray, D.T.; Sherman, J.D. Desynaptic chromosome behavior of the gms mutant in watermelon. J. Hered 1988, 79, 397–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.P.; Rhodes, B.B.; Baird, W.V.; Skorupska, H.T.; Bridges, W.C. Phenotype, Inheritance, and Regulation of Expression of a New Virescent Mutant in Watermelon: Juvenile Albino. J. Amer. Soc. Hort. Sci. 1996, 121, 609–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Zhang, X.; Wei, Z.; Li, Q.; Li, X. Inheritance of male-sterility and dwarfism in watermelon [Citrullus lanatus (Thunb.) Matsum. and Nakai]. Sci. Hortic. 1998, 74, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugyama, K.; Morishita, M. Production of seedless watermelon using soft-X-irradiated pollen. Sci. Hortic. 2000, 84, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velkov, N.; Tomlekova, N.; Sarsu, F. Sensitivity of watermelon variety Bojura to mutant agents 60Co and EMS. J. BioSci. Biotech. 2016, 5, 105–110. [Google Scholar]

| Self-pollinated progeny | Total | Male fertile |

Male sterile |

Ratio Obs:Exp | Chi square | Probability P(%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2022 | ||||||

| Concurrent 4-1 | 18 | 14 | 4 | 3:1 | 0.0741 | 78.55 |

| Concurrent 4-4 | 18 | 12 | 6 | 3:1 | 0.6667 | 41.42 |

| Concurrent 4-6 | 17 | 13 | 4 | 3:1 | 0.0196 | 88.86 |

| 2023 | ||||||

| Concurrent 4-1-3 | 10 | 7 | 3 | 3:1 | 0.1333 | 71.50 |

| Concurrent 4-4-6 | 12 | 8 | 4 | 3:1 | 0.4444 | 50.50 |

| Concurrent 4-6-8 | 14 | 10 | 4 | 3:1 | 0.0952 | 75.76 |

| Total | ||||||

| Concurrent | 89 | 64 | 25 | 3:1 | 0.4532 | 50.08 |

| Genotype | Days to mass flowering | Days to ripening | Vegetation period (days) | Fruit weight (kg) | Fruit length (cm); | Fruit diameter (cm); | Rind thickness (cm) | TSS (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2022 | ||||||||

| Concurrent 4-1 | 56 | 35 | 91 | 3.414 | 18 | 19 | 0.9 | 8.2 |

| Concurrent 4-4 | 55 | 42 | 98 | 4.316 | 22 | 20 | 0.6 | 7.0 |

| Concurrent 4-6 | 56 | 33 | 89 | 4.156 | 19.5 | 20 | 0.9 | 8.2 |

| 2023 | ||||||||

| Concurrent 4-1-3 | 61 | 50 | 111 | 1.754 | 14 | 15 | 1 | 9.0 |

| Concurrent 4-4-6 | 59 | 44 | 103 | 1.140 | 14 | 12 | 1 | 9.8 |

| Concurrent 4-6-8 | 60 | 55 | 115 | 1.446 | 14 | 14 | 0.6 | 8.0 |

| Mean | 57.8 | 43.2 | 101.2 | 2.7 | 16.9 | 16.7 | 0.8 | 8.4 |

| Standard Error± | 1.0 | 3.5 | 4.3 | 0.6 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 0.1 | 0.4 |

| Confidence Level (95.0%) | 2.6 | 8.9 | 11.0 | 1.5 | 3.6 | 3.6 | 0.2 | 1.0 |

| Probability of mutation occurring | Confidence probability | nmin |

|---|---|---|

| 0.00067 | P3 – 0.95 | 4492 |

| 0.067% | P3 – 0.99 | 6905 |

| P3 = 0.999 | 10358 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).