1. Introduction

With the growing demand for Additive manufacturing (AM, or 3D printing) to produce quick, customizable parts for prototyping and finished parts, the pressure has risen to improve its energy demand and use more sustainable materials. This is because the environmental impacts of AM are often 1.4 – 10 times that of injection molding the same plastics, and casting or extruding in the same metals [

1,

2,

3,

4]. One way to reduce the impacts of both energy and materials at once is to replace the melting of plastics or metals with ambient temperature processing of biomaterials that can also be sourced from preconsumer or postconsumer waste [

5].

Additive manufacturing (AM, or 3D printing) is a broad collection of technologies that can produce small batches of parts in a short time, with various materials, including polymers, ceramics, concrete, metals, and even hydrogels for tissue engineering, as well as advanced high-entropy ferrites. These offer a wide range of applications, from marine industry to large scale building construction [

6] to medical and pharmaceutical applications [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. AM is often thought of as a “green” technology, because it often does reduce impacts compared to machining, mostly because of reduced material waste [

12].

Many AM technologies require high temperatures to melt plastic or metal. For example, wire arc additive manufacturing (WAAM), where subsequent layers of metal are deposited like welding in an inert atmosphere, need to provide temperature peaks exceeding 1000˚C to melt Cu-Al alloys [

13,

14], consuming very large amounts of energy [

15]. For plastic 3D printing technologies, temperatures are much lower; the most common polymer printing method is Fused Filament Fabrication (FFF, also called FDM), using temperatures of 190 – 250˚C for ABS plastic [

16], 190 – 220˚C for PET plastic [

17], and 120 – 190˚C for PLA bioplastic [

16]. Metal printing of almost all technologies also require large amounts of energy for melting metals.

However, eliminating the need to melt plastic or metal can cut energy demand up to 75% [

18]. Some conventional AM technologies already avoid melting materials, such as stereolithography (SLA) and digital light projection (DLP) both using ultraviolet light to cure photopolymers, but these technologies are often still energy-intensive [

19] and also often use hazardous substances [

20]. Clay printing uses low-environmental-impact mineral material in an ambient temperature extrusion process, and has grown to become a notable fraction of the global printing market [

21], but it still requires energy-intensive firing of the clay after printing, and produces brittle parts with low resolution. Thus, new materials should be found that can be printed at ambient temperature at adequate quality and strength without the need for high energy.

Biomaterials are an emerging group of materials used for additive manufacturing. Most biomaterial extrusion printing has been a form of FFF, still melting plastic, but using cellulosic fillers. For example, betel nut shell-derived carbon as a filler for PLA composite FFF resulted in tensile strength increasing by 51.1% with 0.1% biocarbon content and 24.5% increase of flexural strength with 0.025% biocarbon addition [

22]. Even though this does not improve energy impacts, it can reduce the amount of non-biodegradable waste as well as the negative impacts associated with sourcing of fossil-based materials, and biomaterials are often easy to process and available locally, thus saving material processing energy and machinery [

18]. For more sustainable printing, biomaterials can be extruded at room temperatures. This is often used in biomedical and tissue engineering sectors, to avoid killing living cells, with novel hydrogels containing gelatin and alkali lignin [

23]. Food is also being 3D printed, e.g., chocolate, fruit based snacks, pork paste, potato puree, or banana matrix [

24]. Biomaterial 3D printing has even been used for coral reef structural restoration [

25], and for wastewater treatment using 3D printed bio-ink hydrogel to immobilize heterotrophic bacteria with ammonia removal ability [

26].

Replacing plastics with new materials can also reduce the embodied impacts of materials by up to 80% [

18]. This enormous gain is usually achieved by printing waste biomass, e.g., agricultural, timber, or food waste [

27]. These include sawdust, nut shells, mussel shells, egg shells, coffee grounds, citrus peels, and more [

5,

18,

28,

29]. In addition to saving energy and saving material impacts, they are generally non-toxic, using water-based solvents that evaporate to harden. This also improves the circular economy, because in most cases, objects printed with these upcycled waste biomaterials can be easily recycled on-site by simply grinding and adding water to re-print [

30]. While the environmental advantages are large, these materials and processes have so far had significant disadvantages also. Because they are water soluble, they are not waterproof, limiting their applications. Also, they are brittle, often with 2% - 50% the strength of an ABS or PLA plastic FFF print [

5,

31]. Their print quality is also sometimes unpredictable during and after printing, e.g., shrinking or warping, with worse overhang angle and bridging distance capability than plastic FFF [

30]. These can sometimes be fixed using pre- or postprocessing, including coatings or thermal treatment, and material formulations may be improved with artificial intelligence, but such developments are still in early stages [

32].

We cannot assume that all biomaterial AM provides sustainability improvements. Most published studies of such materials do not quantify their environmental impacts [

33,

34,

35], but we should quantify them, to find how much better some materials and processes are than others, and how much better or worse they are than conventional plastic AM.

Thus, this study used life cycle assessment (LCA) to quantify the impacts of new material formulations in a new kind of printer than have been quantified before. Specifically, it measured materials mostly comprised of oyster shells, pistachio shells, and clay; it measured these being extruded by a motorized leadscrew printhead, not a pneumatic pressure printhead as studied in [

18].

2. Materials and Methods

To compare environmental impacts of the materials and processes, one model was used and printed in all different materials, with a standard FFF desktop printer and a version of the same printer modified for biomaterial paste extrusion (direct ink writing). For each print run, printer energy and material use and waste were all empirically measured. The masses and types of materials comprising the printer hardware were also empirically measured. Then various LCA scenarios were modeled for sensitivity analysis of different electricity sources and different printer utilization rates, calculating environmental impacts per part printed. These were then compared to a large body of previous studies printing a different part, calculating environmental impacts per kg of material printed. Details of material selection, printer modification, part geometry, measuring print energy, and LCA methods follow.

2.1. Material Selection

The three biomaterials were selected for the study—oyster shells, pistachio shells, and clay—were selected for local availability and previous experience with printing at ambient temperatures with better quality than most biomaterials. They were compared to PLA bioplastic FFF as a baseline reference because PLA is a ubiquitous desktop print filament and because it is more sustainable than fossil fuel plastics. While it is biodegradable in some industrial composting conditions, it often requires decades to decompose in natural conditions [

36]. The three biomaterials for ambient temperature printing were prepared with xanthan gum as a binder. Xanthan gum has been recognized as an easily available, safe, and reliable binder characterized by nearly instantaneous solidification [

37]. The recipes used to prepare oyster shells and pistachio shells mixtures were as follows:

- -

Oyster shells (61g) + xanthan gum (3g) + water (36g);

- -

Pistachio shells (61g) + xanthan gum (3g) + water (96g).

Filler materials (oyster shells and pistachio shells) were ground and sieved to the desired particle size between 0.2 – 0.4 mm in order to prevent the print nozzle from clogging.

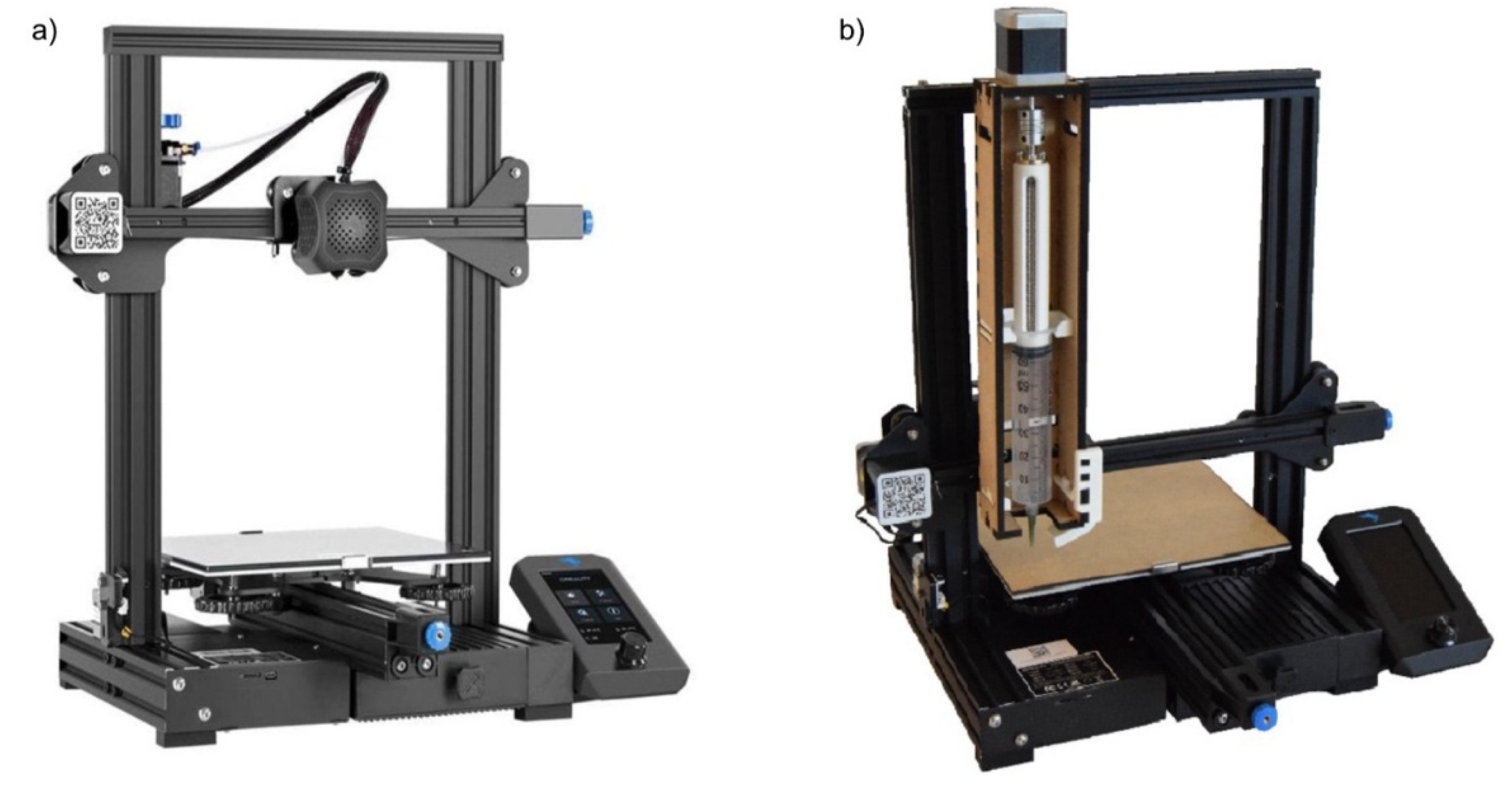

2.2. Printer and Its Modifications

The Creality Ender-3 V3 SE is a popular small scale FFF printer that allows users to create 3D objects by melting and extruding plastics such as PLA, ABS, and TPU. A reference part was printed from PLA to compare the biomaterial prints to. In order to print using biomaterial pastes at ambient temperatures, the extruder was replaced with a Junai print head, which uses a stepper motor with leadscrew to push the syringe plunger down, squeezing paste out the syringe nozzle instead of feeding plastic filament through a melting head [

38]. The original printer [

39] and the printer after modifications are presented in

Figure 1.

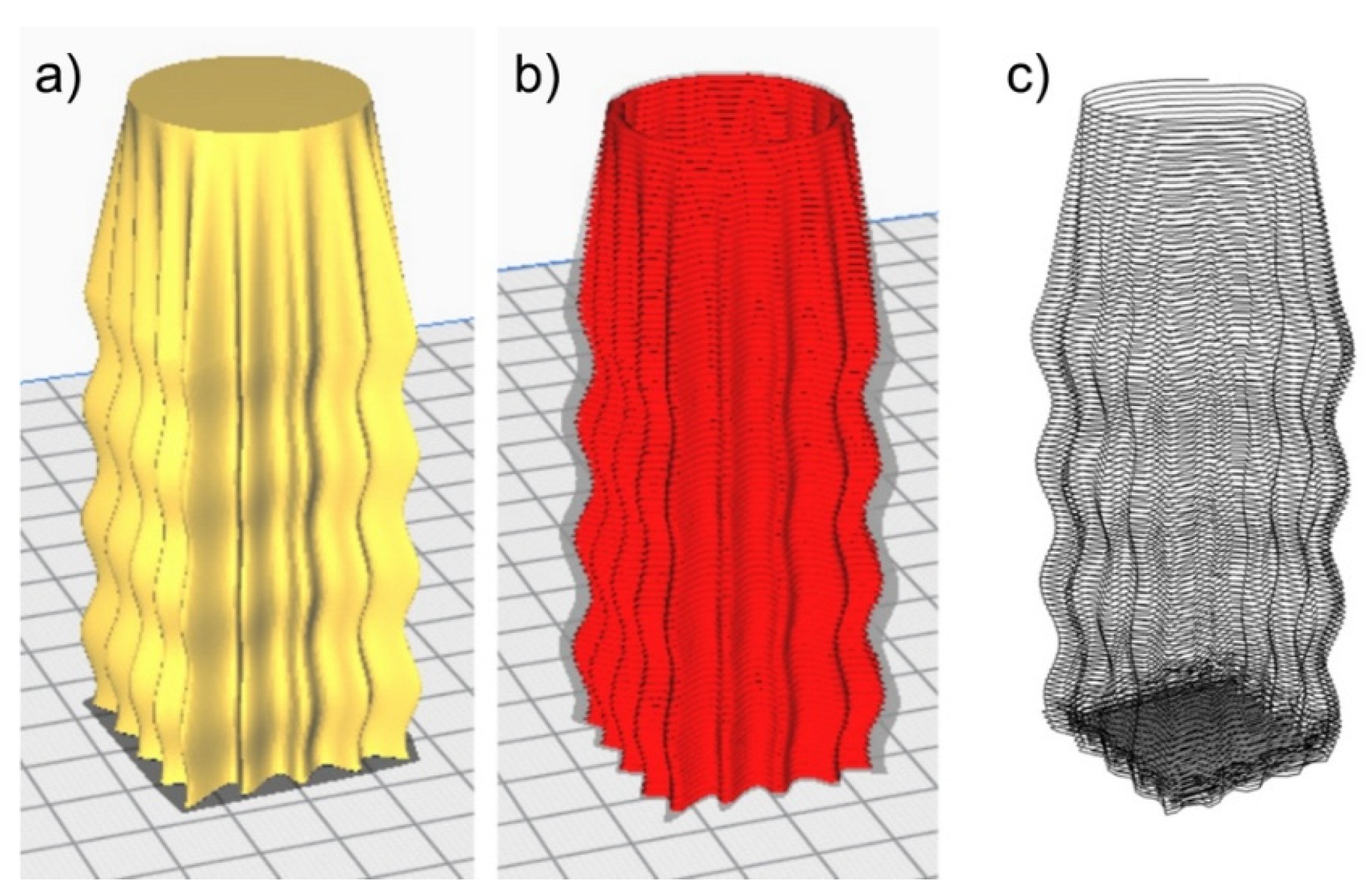

2.3. Part Geometry

Instead of slicing a solid object from a CAD model into 2D layers and converting these to a print path, a grasshopper script that generates the print path directly was created [

36]. While it is true that CAD models run through slicing software make higher resolution prints, this is at such a small scale that it is not needed, it only makes the print file larger and the printing more difficult. The difference between CAD mesh and polysurface objects is that mesh objects are made up of vertices, edges, and faces defined by triangular or quadrilateral polygons, whereas polysurface objects are composed of NURBS (Non-Uniform Rational B-Splines) surfaces that are mathematically precise [

35]. When slicing meshes, there are more intersection points at each slicing plane, thus printing curves takes longer.

Figure 2 shows the 3D model in Cura, the sliced 3D object (print path) in Cura, and the print path generated in Grasshopper.

A file sliced in Cura (ordinary plastic printing slicer) - the original size of the object is in faded-out grey, whereas the actual print path is in red. It is visually evident that the actual printed object will be much smaller than the 3D model itself. The Grasshopper print path in contrast, modelling directly the curves (print path) gives great control over the resolution, speed of printing, accuracy of the manufactured shape, etc.

2.3. Measuring Print Energy

Before printing the reference part candle holder, the printer was calibrated and preliminary testing bars were printed to adjust the printer parameters. After satisfactory results were obtained for the test samples, the candle holders were printed with the paste mixtures. After printing, each part was left to dry for at least 24 hours.

Print energy was measured by connecting the printer to a wattmeter that logged cumulative energy use in kWh; readings were taken at the beginning and end of each printer operational mode (warmup, printing, and idling), to measure energy use for each mode. For the upcycled biomaterial DIW printing, no warmup was required prior to printing, but it was required for the baseline FFF printing of PLA bioplastic.

3. Life Cycle Assessment Methods

The environmental impacts associated with the application of organic materials and the 3D printing process itself were quantified using life cycle assessment (LCA). One of the most comprehensive methodologies for performing LCA is ReCiPe 2016, which covers 18 different impact categories. These categories include factors such as global warming potential, mineral resource depletion, human toxicity, and water consumption, among others. By applying this methodology, it becomes possible to compare the overall impacts of different material formulations, electricity mixes, printer utilization rates, and more, to guide the development of more sustainable 3D printing solutions. Additionally, the information collected during an LCA can support regulatory compliance and encourage the adoption of sustainable innovations within the additive manufacturing industry [

40]. This study was performed with SimaPro 9.6.0.1 software, using ReCiPe 2016 Endpoint (H) V1.05 / World (2010) H/H [

41] method and ecoinvent 3.10 database. The comparisons with previous studies were performed using the same ReCiPe 2016 Endpoint (H) method and also IPCC 2013 GWP 100a V1.03.

3.1. Goal, Scope, and Functional Units

The LCA goal, scope, and functional unit were set following the protocol of previous studies comparing impacts of many different AM technologies, including other sustainable direct ink writing (paste extrusion) [

12,

18,

19,

28]. This enabled not only the comparison of the scenarios measured in this study, but also the comparison of this study’s results to the previous studies. To summarize, the goals were to A) find the largest environmental impacts in each process measured, and B) compare the impacts of printing with ambient temperature upcycled biomaterial extrusion to printing with conventional FFF melting of PLA bioplastic.

The boundaries were cradle-to-grave, as follows:

Print material (the material in the final printed part): Boundaries included raw material extraction, transportation from the collection site, processing (including filament extrusion for PLA), and end of life. Boundaries excluded usage of the printed part, or transport to / from a usage site, as it was assumed parts were used on-site and were inert (e.g., not used in a vehicle burning fuel). Disposal of materials were not included because they can be reprinted multiple times. Impacts of producing crops which the waste biomaterial came from were also excluded, as those should be allocated to the impacts of people eating those foods (e.g., oysters or pistachios).

Waste material: process can be considered waste free as the material can be reused; the only waste was unmeasurable (i.e., leftovers from the clogged nozzle).

Printer hardware: Boundaries included raw material extraction, processing, transportation of the printer from the factory producing it to the local site of printing, and end of life, all amortized per printed part (see functional unit below). This also included hardware for the modified extruder for direct ink writing.

Print process energy: Boundaries included electricity use while starting up / calibrating, warming up (if it occurred), printing, and idling (for low utilization scenarios).

The functional unit for the characterization of environmental impacts was a reference part – a candle holder. This was different from the reference part used in the previous studies (an apple shape) because the print quality of this study’s biomaterials and process were insufficient to print the apple part, due to its high overhang angle and high resolution feature requirements. Therefore, to allow the comparisons with previous studies, a second functional unit was chosen: those comparisons used environmental impacts per kg of material in the final printed part.

3.2. Life Cycle Inventory

In order to assess the environmental impacts of the process, all the inputs and outputs were quantified and organized. Electricity use per part printed was measured as described above. Material consumption and waste for the baseline FFF prints of PLA were measured by weighing the final part and any other filament extruded in calibration or other processes. Material consumption and waste for DIW upcycled biomaterial prints were measured directly from the extruder syringe. This was to avoid counting evaporated water weight as material waste, since the materials required roughly one day to dry after printing. While there was almost no material wasted during printing, as the model did not require any support material, there was calibration material and material left over in the syringe after printing. Any material not in the final print was reused.

Printer hardware masses were measured by weighing components separately, since it was a new printer being assembled from parts. Extruder modifications were included in the bill of materials for the ambient temperature biomaterial printing—conservatively not assuming a purpose-built DIW printer, but counting the impacts of the normal Ender FFF printhead which was removed, plus the new syringe print head. In the previous studies we compare to, the printer hardware was modeled not by disassembling printer parts and weighing them, but according to the protocol [

12,

18,

19,

28]: measuring each component’s dimensions to calculate volumes, then multiplying these volumes by reference values of the densities of materials (e.g., steel, aluminum, etc.) and estimating manufacturing methods based on the appearance of components (e.g., rolling for sheet metal parts, extrusion for rods, etc.) Minor disassembly was performed as needed to measure circuit boards and other interior components, but this was minimal to avoid damaging the printer. Because masses were estimates, all bill of materials data was assumed to have ±30% uncertainty or higher, though the total sum of component masses was within 5% of the total mass of the printer. Electronic components (e.g., circuit boards, cables, and screen) were modeled not by mass but by area or length or item, as needed to match EcoInvent database processes. For this study, before the printer as assemblied, all the parts were weighted using a laboratory scale, including the modified extruder. The lifespan of the printer was assumed to be 5 years, as in the earlier studies.

The printer is produced in a factory located in China. The transport included in the study covers 132.26 tkm travelled in a container ship from Shenzhen to Rotterdam, and 0.17 tkm by truck from Rotterdam to Delft. As mentioned above, transport of print materials was not considered, as the upcycled biomaterials are widely available locally. This does ignore the transportation of PLA filament, but it is likely a negligible impact overall.

End of life of the printer was simply assumed to be average disposal scenario for the location modeled, including various percentages of materials recycled, incinerated, or landfilled. Two different locations were used for average disposal scenarios, the Netherlands and the US (see Scenarios, below). End of life of the printed PLA was assumed to be incineration or landfill, depending on the scenario (see below), because it is not compostable in most cities. End of life of upcycled biomaterials was assumed to be backyard composting, as all the materials used are easily degradable in such conditions.

3.3. Scenarios

Two variables can greatly change the impacts per part printed for any 3D printer: electricity mix and printer utilization. Electricity mix obviously matters because 100% solar or wind energy has a tiny fraction of the impacts of coal-fired electricity, and different countries and regions have different electricity generation mixes. This study was performed in the Netherlands but wished to compare data across Europe and with the previous studies performed in the US, so three sets of scenarios were run, one with 2024 Ecoinvent average Dutch electricity mix and end of life disposal, one with 2024 average European Union electricity mix and Dutch (not EU) end of life disposal (because the Dutch high rates of recycling and waste-to-energy are used as a goal for many EU countries, but there is no average EU disposal in the database), and one with 2024 United States national average electricity mix and end of life disposal.

Printer utilization also greatly changes the impacts per part, because it determines idle energy usage and determines the amortization of printer hardware impacts. Following the protocol of previous studies [

12,

18,

19,

28] utilization was modeled in three scenarios:

- a)

1 part printed per week, with the printer turned off between prints (1x/week, off);

- b)

1 part printed per week, with the printer left on idling (1x/week, idle);

- c)

Maximum theoretical utilization: continuous printing for the printer’s entire life (print 24/7).

The print energy per part (electricity consumption for printing alone, not counting warmup or idling), maximum amount of parts printed per day, and mass per part for each material are presented in

Table 1.

Considering the number of parts printed from each material for the three utilization scenarios and the lifespan of the printer, the allocation coefficients for the three different scenarios are presented in

Table 2.

3.4. Analysis

For each of the four print materials and processes, six LCA models were generated to cover all the scenarios listed above. Monte Carlo analysis was performed to quantify overall uncertainties for each model’s total impacts. In each model, impacts were graphed with impacts categorized by: material production and manufacturing, transport, electricity use, material use, and disposal. These graphs were compared to find which materials and processes caused the least impacts in the different scenarios, as well as what caused the largest impacts for each material and process in each scenario (e.g., energy use, material use, or other).

3.5. Comparison to Previous Studies

To compare the new materials and print method to as many other existing polymer printing technologies as possible, results from this study were compared with the previous studies which this protocol was based on [

12,

18,

19,

28]. However, those studies were performed printing a different reference part, with an older version of the ReCiPe methodology and Ecoinvent database (see papers for details). The reason for the different reference part was described above, a result of limitations in printable overhang angles and resolution. To normalize between the part printed here and the part printed in the previous studies, the data from this study and the previous studies were all recalculated with a different functional unit: impacts per kg of material printed.

There was no way to normalize between different Ecoinvent databases and ReCiPe methods, because the previous studies did not disclose full bills of materials for all printer hardware. This means the results are not quite in the same units or based on quite the same source data, and thus cannot be precisely compared. It is not clear how much error margin this introduces, but we estimate it to be no more than 10% overall. Even without precisely matching methods, the comparison was still deemed useful, as many of the impacts of different printers are orders of magnitude apart, much larger than differences due to databases and updated methodologies are likely to be.

4. Results and Discussion

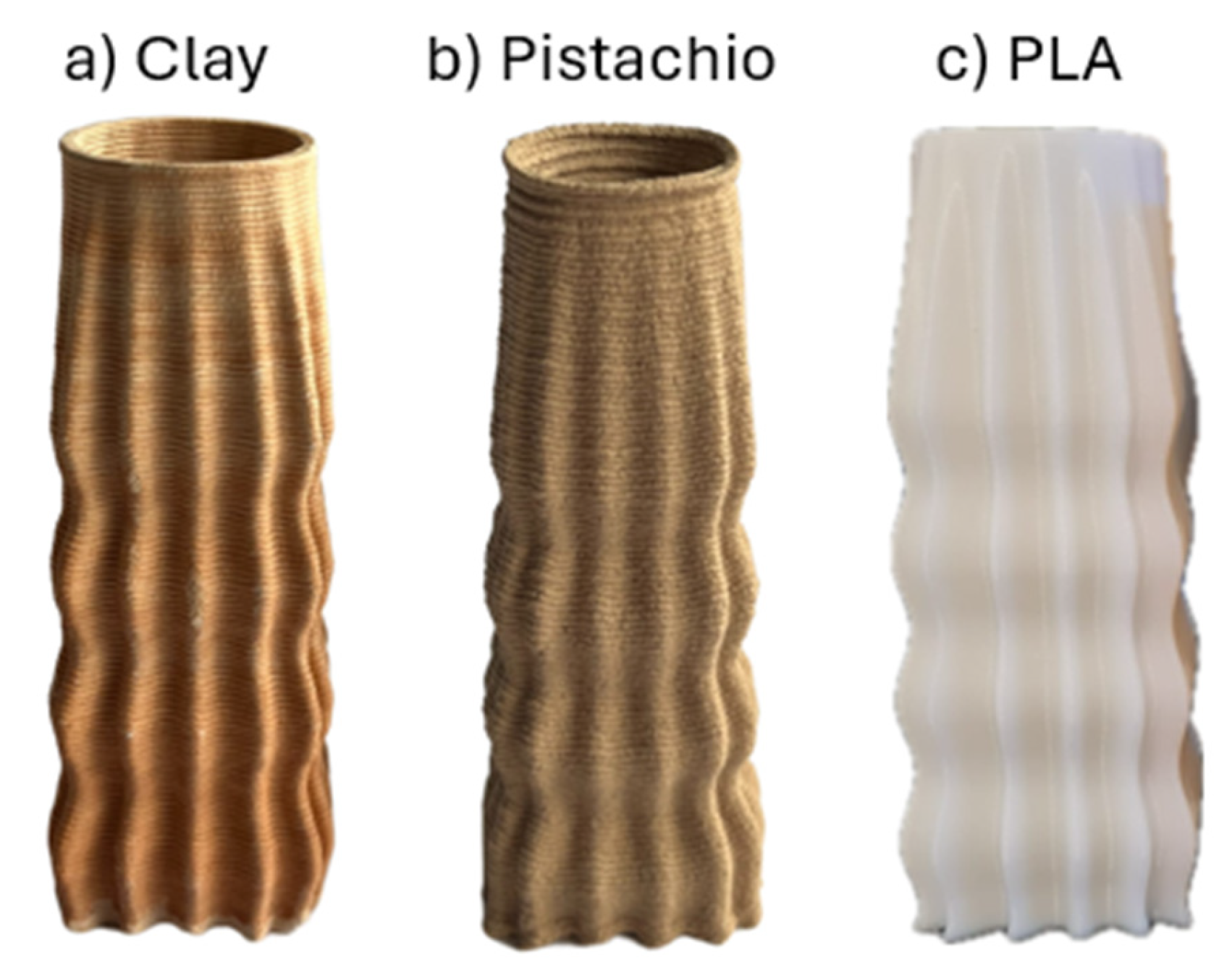

Printing the candle holder in the upcycled biomaterials was successful, as shown in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3. While the material and process was not able to achieve the high overhang angles and fine resolution of previous apple prints, it did print this larger object faster, and achieved significant vertical height without collapsing or slumping. Reference parts printed using Creality Ender-3 V3 SE are presented in

Figure 3.

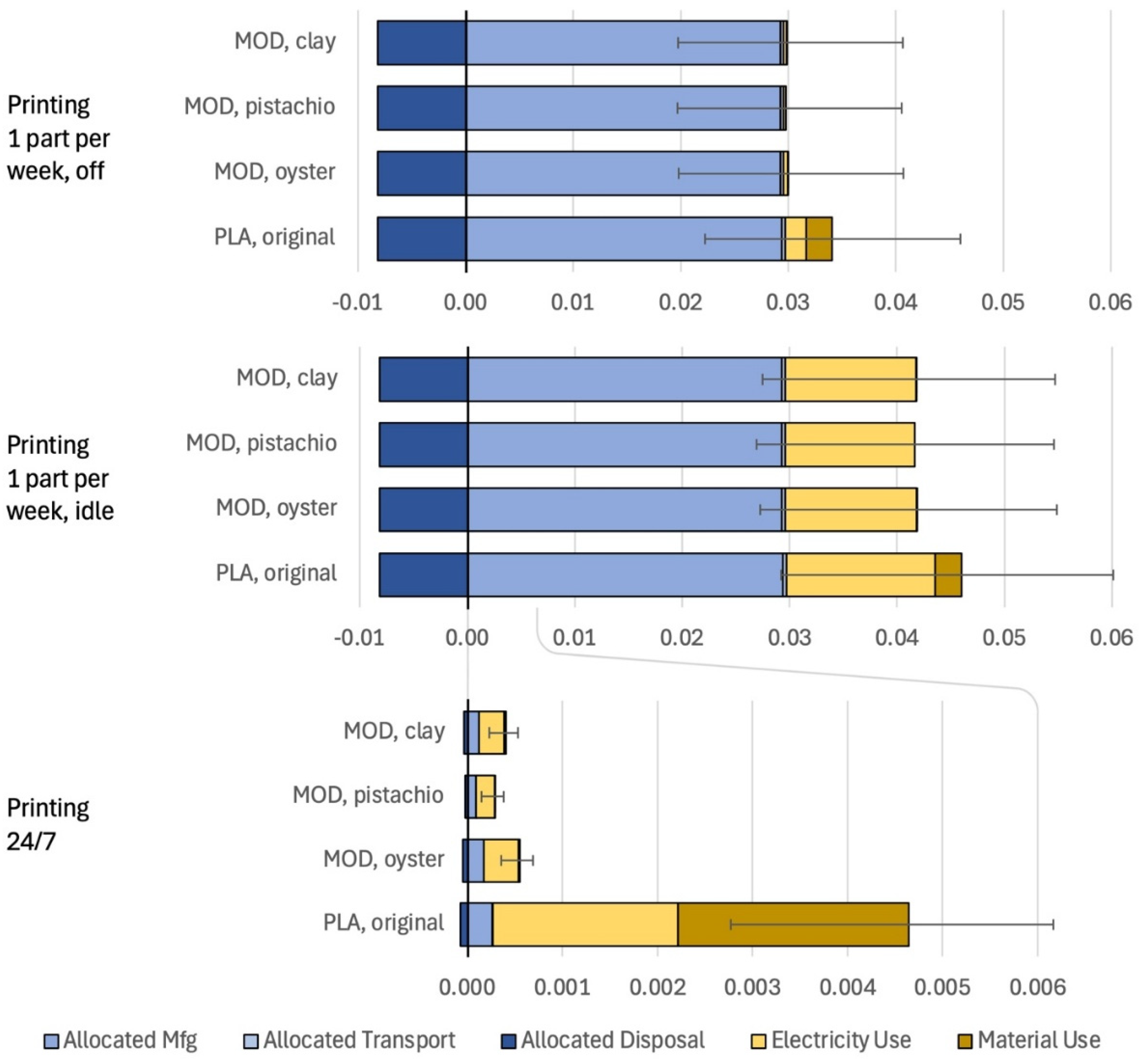

4.1. ReCiPe 2016 Endpoint (H) Impacts

The life cycle impacts of 3D printing candle holders from clay, pistachio shells, oyster shells, and PLA were compared to each other in the three utilization scenarios (1 part per week/off, 1 part per week/idle, print 24/7). The ReCiPe 2016 Endpoint (H) impact results and their Monte Carlo uncertainties are summarized in

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and Figure 6. All four materials in all three utilization scenarios were also modeled in scenarios for Dutch energy mix and disposal (NL), average European energy mix and Dutch disposal (EU avg), and average US energy mix and disposal (US avg).

Figure 4 shows only the NL scenarios; the remaining results are presented in the Supplementary Material (

Figure S1).

For both scenarios printing 1 part per week, the printer manufacturing, transport, and disposal impacts are equal. This type of utilization of the printer is usually the case for domestic, occasional use. The highest difference can be observed for electricity use, which proved that leaving the printing on idle will increase the energy consumption (and, consequently, economic costs) when compared to switching off the printer after the part is ready. Commercial applications are closer to the printing 24/7 scenario. Here, the machine manufacturing impacts per part are a relatively small fraction of the whole, while the share of electricity consumption increases. However, the overall environmental impacts for all of these are roughly an order of magnitude smaller than any of the lower-utilization scenarios (i.e., 0.022 Pts for 1 part/week off scenario, 0.033 Pts for 1 part/week idle scenario, and 0.003 Pts for print 24/7 scenario for pistachio shells).

Another important factor is the material use. For all the scenarios it can be observed that the biomaterials (pistachio shells, oyster shells and clay) display a significantly lower impact than PLA. This difference becomes especially large in the printing 24/7 scenario. This is because there is very little impact caused by upcycling waste and easily accessible materials that do not include excessive processing prior to printing. The production of PLA, on the other hand, involves extensive chemical processing and often competes with food crops for land. Also, elevated temperatures are required to perform the printing procedure, what translates into increased energy consumption, which is often associated with fossil fuel combustion, depending on the country’s energy mix. Figure 6 shows that replacing the melting of plastics with ambient temperature extrusion cut energy use by up to 89%. The overall improvement in environmental impacts (not counting beneficial impacts of machine end of life) was up to 94%.

Note that the beneficial (negative) impacts of disposal are largely negative because the printer is mostly comprised of metals, which will be recycled at end of life. This uses the system expansion and avoided burden approach, which accounts for material and/or energy recovery as well as recycling benefits. The waste treatment processes (i.e., recycling, or even incineration) generate environmental profits by avoiding the burden of mining virgin metals for future products, or burning fossil fuels for electricity. In the Netherlands, recycling and waste-to-energy incineration are highly efficient, with almost no landfill [

42].

Different electricity mixes and disposal methods significantly change the results shown above (see

Figure S1 of the Supplementary Material for the NL, EU, and US scenarios). They do not change which print materials and process scores best— pistachio shell printing scores best and PLA printing scores by far the worst in all electricity/disposal scenarios. But they change the absolute values of the impacts, and change how much better or worse the different print processes are relative to each other. In all cases, the results are less favorable for the US scenario, because their energy mix involves much more fossil fuels than the average European countries, and the Netherlands and other EU countries have very strict rules regarding waste collection and end-of-life disposal, while the US mostly landfills.

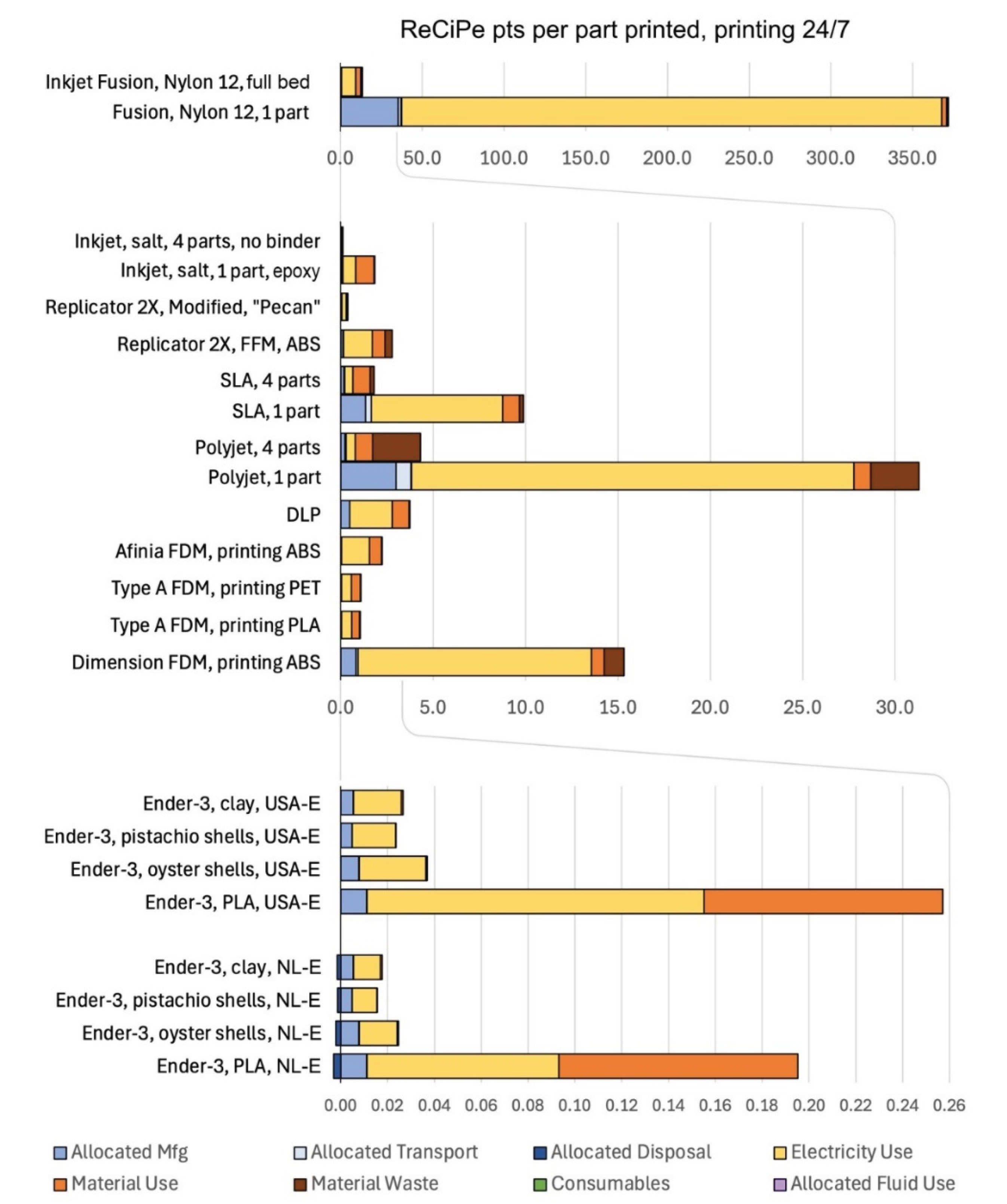

4.2. Comparison with Previous Apple Studies

As mentioned above, the previous studies which this protocol was based on were performed printing a different reference part, with an older version of the ReCiPe methodology and Ecoinvent database. This means the results are not quite in the same units or based on the same source data, and thus cannot be precisely compared. However, as can be seen below, many of the impacts are orders of magnitude apart, much larger than differences due to databases and updated methodologies are likely to be. The ReCiPe 2016 Endpoint (H) impacts per kg of material printed are presented for both NL and USA scenarios. The results for the print 24/7 scenario are presented in Figure 7. The results for print 1 part/week, off and print 1 part/week, idle scenarios are presented in

Figures S2 and S3 in the supplementary material. The materials from the previous studies included CPS 4D, Accura ABS White, ABS, PET/PLA, chemically bonding paste, Fullcure 720 and salt with optional epoxy infusion, and the printers used such technologies as Digital Light Processing (DLP), stereolithography (SLA), FFF, pneumatic extrusion, polyjet and inkjet binding [

19].

The impacts per kg of material printed show the Ender printing in pistachio, clay, and oyster to cause some of the lowest environmental impacts, lower than any other polymer printing technologies that melt plastics or use UV-curing epoxies, sometimes 5x – 50x better. The modifed Ender impacts were comparable only to the Injket printer printing 4 parts simultaneously and the modified Replicator 2X, also printing with ambient temperature paste extrusion. This is encouraging, as the modified Replicator used pneumatic pressure to extrude paste, eliminating one motor from the bill of materials and eliminating the motor’s energy use from print processing, in comparison to the modified Ender’s leadscrew-driven paste extrusion. This means that the extra environmental impacts of this motor and its energy use are not significant compared to the large energy savings of not melting plastic, and the low impacts of producing the upcycled materials compared with producing PLA plastic (even though it is a bioplastic). The results for printing with biomaterials for both EU average and US average electricity mix scenarios seem promising.

However, when comparing to previous studies, it is important to remember that the they were performed 5 - 10 years ago, with older versions of both SimaPro and the Ecoinvent database. The newer database might include not only updated and more in-depth information about processes and materials, but also changes in such fields as manufacturing procedures and energy mix variations. Thus, readers should assume more margins of error.

5. Conclusions

The increasing demand for quick and easily customizable production is driving the rise of additive manufacturing. While AM is currently a highly energy-intensive process with large environmental impacts, this can be radically improved. This study showed that, at least for some applications, PLA printing can be replaced with clay, upcycled oyster shell, or upcycled pistachio shell, using xanthan gum as a binder. Printer modifications, including extruder adjustments, were necessary for the application of these novel materials, highlighting the adaptability required for sustainable 3D printing applications.

Replacing the melting of plastics with ambient temperature extrusion of upcycled biomaterials can cut print energy up to 89% and cut overall impacts up to 94% . Such large improvements even include comparing printing of “green” bioplastic to extruding simple mineral clay, not even using upcycled biomaterial waste. These results were for a printer at maximum utilization for its whole life; other models tested lower utilization scenarios and found them to cause roughly 10x the impacts per part, depending on circumstances, without as large a difference between DIW upcycled biomaterials and melting plastic, because amortized impacts of printer hardware become a much larger share of total impacts.

The numbers listed above were for electricity use and disposal in the Netherlands; scenarios for EU and US electricity use and disposal show potentially even greater improvements for replacing melted plastics with ambient temperature biomaterials. The absolute impacts of all scenarios were much better in NL and EU than the US. Disposal impacts played a significant part in this for low utilization scenarios, not just cleaner electricity grids, because recycling rates are far higher in NL and EU, while the US landfills most waste.

These environmental advantages are great, but there are challenges like lower strength, lack of waterproofness, shrinkage, and lower print quality (such as the inability to print parts matching previous studies, due to limitations on overhang angle and resolution). Future research into new formulations (perhaps with AI assistance), protective coatings, thermal treatment, and other strategies may help mitigate these problems.

Comparing with previous studies showed that this study’s printing with the modified Creality Ender-3 V3 SE performs with minimal environmental impact, better than any other polymer printing technologies that melt plastics or use UV-curing epoxies, comparable only to the previous studies’ modified Replicator 2X using “Pecan” material and inkjet printer printing four or more parts at once. However, caution is required when comparing these findings with previous studies, as they were conducted several years ago using older versions of SimaPro and the Ecoinvent database. Updates in software, manufacturing procedures, and energy mix data may have significantly altered impact assessments, highlighting the importance of considering methodological advancements when interpreting results.

In the end, shifting towards ambient temperature printing of biomaterials offers extremely large environmental benefits, even when compared to “green” bioplastics. These materials and processes do not yet have the strength or print quality to directly replace all polymer printing, but they are already viable for some applications, such as prototyping “look and feel” product models, architectural models, or other objects with low strength and resolution requirements. Ongoing advancements in material formulation, processing, and printing should optimize the performance of these emerging technologies so they can replace high-energy printing of plastics at scale. Even with their current limitations, they offer a wide range of new possible applications that should be explored.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

The study was performed during K.K.’s research visit at TU Delft, supervised by J.F., with technical mentoring and test execution performed by N.J. with K.K. assistance. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, J.F., N.Y. and K.K.; methodology, K.K., N.Y.; software, K.K.; validation, J.F.; formal analysis, K.K., J.F.; investigation, K.K.; resources, K.K, N.J.; data curation, K.K.; writing—original draft preparation, K.K.; writing—review and editing, J.F.; visualization, J.F., N.Y.; supervision, J.F.; project administration, K.K.; funding acquisition, K.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.” Please turn to the CRediT taxonomy for the term explanation. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Funding

The study was performed in the cooperation between Łukasiewicz Research Network – Institute of Non-Ferrous Metals and TU Delft Faculty of Industrial Design Engineering as a part of the Łukasiewicz Research Program.

Institutional Review Board Statement

n/a.

Informed Consent Statement

n/a.

Data Availability Statement

n/a.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Garcia, F.L.; Nunes, Andréa Oliveira; Martins, Mariane Guerra; Belli, Maria Cristina; Saavedra, Yovana M.B.; Silva, Diogo Aparecido Lopes; Moris, V.A. da S. Comparative LCA of Conventional Manufacturing vs. Additive Manufacturing: The Case of Injection Moulding for Recycled Polymers. Int. J. Sustain. Eng. 2021, 14, 1604–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faludi, J.; Cline-Thomas, N.; Agrawala, S. The Next Production Revolution: Implications for Governments and Business. Ch.5: 3D Printing and Its Environmental Implications; Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD): Paris, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- DeBoer, B.; Nguyen, N.; Diba, F.; Hosseini, A. Additive, Subtractive, and Formative Manufacturing of Metal Components: A Life Cycle Assessment Comparison. Int J Adv Manuf Technol 2021, 115, 413–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Sice, C.; Faludi, J. Comparing Environmental Impacts of Metal Additive Manufacturing to Conventional Manufacturing. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Proceedings of the International Conference on Engineering Design, Gothenburg, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera, M.L.; Bae, S.S.; Hudson, S.E. Designing a Sustainable Material for 3D Printing with Spent Coffee Grounds; 2023; pp. 294–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.H.; Ahmed, A.; Ali, T.; Qureshi, M.Z.; Islam, S.; Ahmed, H.; Ajwad, A.; Khan, M.A. Comprehensive Review of 3D Printed Concrete, Life Cycle Assessment, AI and ML Models: Materials, Engineered Properties and Techniques for Additive Manufacturing. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2025, 43, e01164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warski, T.; Kubacki, J.; Łukowiec, D.; Babilas, R.; Włodarczyk, P.; Hawełek, Ł.; Polak, M.; Jóźwik, B.; Kowalczyk, M.; Kolano-Burian, A.; et al. Magnetodielectric and Low-Frequency Microwave Absorption Properties of Entropy Stabilised Ferrites and 3D Printed Composites. Compos. Part B Eng. 2022, 243, 110126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceylan, H.; Yasa, I.C.; Yasa, O.; Tabak, A.F.; Giltinan, J.; Sitti, M. 3D-Printed Biodegradable Microswimmer for Theranostic Cargo Delivery and Release. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 3353–3362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, H.; Seo, Y.B.; Kim, D.Y.; Lee, J.S.; Lee, Y.J.; Lee, H.; Ajiteru, O.; Sultan, T.; Lee, O.J.; Kim, S.H.; et al. Digital Light Processing 3D Printed Silk Fibroin Hydrogel for Cartilage Tissue Engineering. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, Q.; Zeng, Y.; Chen, J. The Applications and Latest Progress of Ceramic 3D Printing. Addit. Manuf. Front. 2024, 3, 200113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ódonnchadha, B.; Tansey, A. A Note on Rapid Metal Composite Tooling by Selective Laser Sintering. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2004, 153–154, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faludi, J.; Bayley, C.; Bhogal, S.; Iribarne, M. Comparing Environmental Impacts of Additive Manufacturing vs Traditional Machining via Life-Cycle Assessment. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2015, 21, 14–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleta, M.; Kulasa, J.; Kowalski, A.; Kwaśniewski, P.; Boczkal, S.; Nowak, M. Microstructure, Mechanical and Corrosion Properties of Copper-Nickel 90/10 Alloy Produced by CMT-WAAM Method. Mater. 2024, Vol. 17 17, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sideris, I.; Petrik, J.; Bambach, M. Too Hot to Print, Too Slow to Handle; Finding Optimal Path Characteristics for WAAM. Manuf. Lett. 2024, 41, 879–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghavendra Pai, K.; Vijayan, V.; Narayan Prabhu, K. Recent Challenges and Advances in Metal Additive Manufacturing: A Review. Mater. Today Proc. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajendran Royan, N.R.; Leong, J.S.; Chan, W.N.; Tan, J.R.; Shamsuddin, Z.S.B. Current State and Challenges of Natural Fibre-Reinforced Polymer Composites as Feeder in Fdm-Based 3d Printing. Polymers (Basel) 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Rashid, A.; Koç, M. Additive Manufacturing for Sustainability, Circularity and Zero-Waste: 3DP Products from Waste Plastic Bottles. Compos. Part C Open Access 2024, 14, 100463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faludi, J.; Van Sice, C.M.; Shi, Y.; Bower, J.; Brooks, O.M.K. Novel Materials Can Radically Improve Whole-System Environmental Impacts of Additive Manufacturing. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 212, 1580–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Faludi, J. Using Life Cycle Assessment to Determine If High Utilization Is the Dominant Force for Sustainable Polymer Additive Manufacturing. Addit. Manuf. 2020, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, C.; Killgore, J.; Poster, D. NIST Special Publication 1500-17 Report from the Photopolymer Additive Manufacturing Workshop: Roadmapping a Future for Stereolithography, Inkjet, and Beyond. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulidindi, K.; Verma, M. Ceramic 3D Printing Market Size, Share & Trends Report - 2032. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Arora, N.; Dua, S.; Choudhary, V.; Singh, S.K.; Senthilkumar, T. Mechanical Properties of Novel PLA Composite Infused with Betel Nut Waste Biocarbon for Sustainable 3D Printing. Compos. Commun. 2025, 53, 102188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decante, G.; Cengiz, I.F.; Costa, J.B.; Collins, M.N.; Reis, R.L.; Silva-Correia, J.; Oliveira, J.M. Sustainable Highly Stretchable and Tough Gelatin-Alkali Lignin Hydrogels for Scaffolding and 3D Printing Applications. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 39, 108875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hai Alami, A.; Ghani Olabi, A.; Khuri, S.; Aljaghoub, H.; Alasad, S.; Ramadan, M.; Ali Abdelkareem, M. 3D Printing in the Food Industry: Recent Progress and Role in Achieving Sustainable Development Goals. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2024, 15, 102386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de León, E.H.P.; Valle-Pérez, A.U.; Khan, Z.N.; Hauser, C.A.E. Intelligent and Smart Biomaterials for Sustainable 3D Printing Applications. Curr. Opin. Biomed. Eng. 2023, 26, 100450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Peng, S.; Li, K.; Qin, D.; Weng, Z.; Li, J.; Zheng, L.; Wu, L.; Yu, C.P. Material Extrusion-Based 3D Printing for the Fabrication of Bacteria into Functional Biomaterials: The Case Study of Ammonia Removal Application. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 60, 103268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.; Mohanty, A.K.; Misra, M. 3D Printing in Upcycling Plastic and Biomass Waste to Sustainable Polymer Blends and Composites: A Review. Mater. Des. 2024, 237, 112558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faludi, J.; Hu, Z.; Alrashed, S.; Braunholz, C.; Kaul, S.; Faludi, Authors Jeremy; Kassaye, A.H. Does Material Choice Drive Sustainability of 3D Printing? World Acad. Sci. Eng. Technol. Int. J. Mech. 2015, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Sauerwein, M.; Doubrovski, E.L. Local and Recyclable Materials for Additive Manufacturing: 3D Printing with Mussel Shells. Mater. Today Commun. 2018, 15, 214–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henssen, A. Print Quality Optimisation of Upcycled Biomaterials for Ambient 3D-Printing; TU Delft, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Pitt, K.; Lopez-Botello, O.; Lafferty, A.D.; Todd, I.; Mumtaz, K. Investigation into the Material Properties of Wooden Composite Structures with In-Situ Fibre Reinforcement Using Additive Manufacturing. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2017, 138, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousaf, A.; Al Rashid, A.; Koç, M. Parameter Tuning for Sustainable 3D Printing(3DP) of Clay Structures. J. Eng. Res. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogas-Soldevila, L.; Duro-Royo, J.; Oxman, N. Water-Based Robotic Fabrication: Large-Scale Additive Manufacturing of Functionally Graded Hydrogel Composites via Multichamber Extrusion. 3D Print. Addit. Manuf. 2014, 1, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rael, R.; San Fratello, V. Printing Architecture, Innovative Recipes for 3D Printing; Princeton Architectural Press: NY, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sauerwein, M.; Zlopasa, J.; Doubrovski, Z.; Bakker, C.; Balkenende, R. Reprintable Paste-Based Materials for Additive Manufacturing in a Circular Economy. Sustain. 2020, Vol. 12 12, 8032 2020 8032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, S.; Zhang, Y.; Gu, J.; Tan, H. Biodegradation Behavior and Modelling of Soil Burial Effect on Degradation Rate of PLA Blended with Starch and Wood Flour. Colloids Surfaces B Biointerfaces 2017, 159, 800–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mallesham, P.; Parveen, S.; Pandiselvam, R.; Rajkumar, P.; Naik, R. Characterisation of 3D Printing Cake Batter with Xanthan Gum and Optimization of Printing Parameters Using Response Surface Methodology. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2024, 38, 101026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junai. Earth. Available online: https://www.junai.earth/product/extruder-kit-direct-drive (accessed on 29 November 2024).

- Official Creality Ender 3 3D Printer|High Precision 3D Printer – Official Creality3D European Online Shop. Available online: https://www.creality.shop/products/ender-3-3d-printer?gad_source=1&gclid=Cj0KCQiAqL28BhCrARIsACYJvkfe6b2FkC-Np4mLfVEiyvajkrU_bARvG_rFktpqymp63HnPv1kjru8aAngaEALw_wcB (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- Klejnowska, K.; Sydow, M.; Michalski, R.; Bogacka, M. Life Cycle Impacts of Recycling of Black Mass Obtained from End-of-Life Zn-C and Alkaline Batteries Using Waelz Kiln. Energies 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huijbregts, M.A.J. ReCiPe 2016 A Harmonized Life Cycle Impact Assessment Method at Midpoint and Endpoint Level Report I: Characterization.

- Early Warning Assessment Related to the 2025 Targets for Municipal Waste and Packaging Waste. 2022.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).