Submitted:

17 December 2025

Posted:

18 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| APC | Annual Percentage Change |

| Bootstrap | Bootstrap resampling technique |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus Disease 2019 |

| Chi-square | Chi-square test |

| DATASUS | Department of Informatics of the Brazilian Public Health System |

| ES | Espírito Santo |

| FU | Federated Unit |

| HDI | Human Development Index |

| IBGE | Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics |

| INCA | Brazilian National Cancer Institute |

| MG | Minas Gerais |

| PAP | Papanicolaou |

| PHEIC | Public Health Emergency of International Concern |

| RJ | Rio de Janeiro |

| SARS-COV-2 | Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 |

| SE | Southeast |

| SP | São Paulo |

| TNM | Tumor, Node, Metastasis |

| FU | Federated Unit |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| n | Number of cases |

| n.d. | Not reported/Not determined |

| P-value | Statistical significance level |

References

- Brasil; Ministério da Saúde; Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Vigitel Brasil 2019: principais resultados. Boletim Epidemiológico 2020, 51, 16. Available online: https://antigo.saude.gov.br/images/pdf/2020/April/16/Boletim-epidemiologico-SVS-16.pdf (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- Brasil; Instituto Nacional do Câncer. Estatísticas de câncer. Available online: https://www.gov.br/inca/pt-br/assuntos/cancer/numeros (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Teixeira, C.F.D.S.; Soares, C.M.; Souza, E.A.; et al. A saúde dos profissionais de saúde no enfrentamento da pandemia de COVID-19. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva 2020, 25, 3465–3474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharwani, A.; Li, D.; Vermund, S.H. A review of the effect of COVID-19-related lockdowns on global cancer screening. Cureus 2023, 15, e40268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patt, D.; Gordan, L.; Diaz, M.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 on cancer care: How the pandemic is delaying cancer diagnosis and treatment for American seniors. Journal of Clinical Oncology Clinical Cancer Informatics 2020, 4, 1059–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasil; Ministério da Saúde. DATASUS TABNET. Available online: http://tabnet.datasus.gov.br/cgi/tabcgi.exe?sim/cnv/evitb10go.def (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- Brasil; Ministério da Saúde; Conselho Nacional de Saúde. RESOLUÇÃO no 510. Available online: https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/saudelegis/cns/2016/res0510_07_04_2016.html (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- Brasil. Brasil | Cidades e Estados | IBGE. Available online: https://ibge.gov.br/cidades-e-estados.html (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Statistical Methodology and Applications Branch, Surveillance Research Program, National Cancer Institute. Joinpoint Regression Program, Version 5.0.2. Available online: https://surveillance.cancer.gov/help/joinpoint/tech-help/citation (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Liu, B.; Kim, H.J.; Feuer, E.J.; Graubard, B.I. Joinpoint regression methods of aggregate outcomes for complex survey data. Journal of Survey Statistics and Methodology 2022, smac014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delacre, M.; Lakens, D.; Leys, C. Why psychologists should by default use Welch’s t-test instead of Student’s t-test. International Review of Social Psychology 2017, 30, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serdar, C.C.; Cihan, M.; Yücel, D.; Serdar, M.A. Sample size, power and effect size revisited: simplified and practical approaches in pre-clinical, clinical and laboratory studies. Biochemia Medica 2021, 31, 27–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Análise Multivariada de Dados, 6ª ed.; Bookman: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2009; pp. 1–688. [Google Scholar]

- RStudio Team. RStudio: Integrated Development for R; Version 4.3.2; Posit Support: Boston, MA, USA, 2024; Available online: https://www.rstudio.com/ (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- Wild, C.P.; Weiderpass, E.; Stewart, B.W. World Cancer Report: Cancer Research for Cancer Prevention, 3rd ed.; International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France, 2020; pp. 1–627. [Google Scholar]

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, M.D.O.; Lima, F.C.D.S.D.; Martins, L.F.L.; Oliveira, J.F.P.; Almeida, L.M.D.; Cancela, M.D.C. Estimativa de incidência de câncer no Brasil, 2023–2025. Revista Brasileira de Cancerologia 2023, 69, e3700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smetana, K., Jr.; Lacina, L.; Szabo, P.; Dvořánková, B.; Brož, P.; Šedo, A. Ageing as an important risk factor for cancer. Anticancer Research 2016, 36, 5009–5018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunneram, Y.; Greenwood, D.C.; Cade, J.E. Diet, menopause and the risk of ovarian, endometrial and breast cancer. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society 2019, 78, 438–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lillard, J.W.; Moses, K.A.; Mahal, B.A.; George, D.J. Racial disparities in Black men with prostate cancer: A literature review. Cancer 2022, 128, 3787–3795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamoah, K.; Lee, K.M.; Awasthi, S.; et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in prostate cancer outcomes in the Veterans Affairs Health Care System. JAMA Network Open 2022, 5, e2144027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga, L.L.B.C.; Ferreira, A.F.; Pinheiro, F.A.S.; et al. Temporal trends and spatial clusters of gastric cancer mortality in Brazil. Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública 2022, 46, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Ailawadhi, M.; Dutta, N.; et al. Trends in early mortality from multiple myeloma: A population-based analysis. Clinical Lymphoma, Myeloma and Leukemia 2021, 21, e449–e455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tachibana, B.M.T.; Ribeiro, R.L.D.M.; Federicci, É.E.F.; et al. The delay of breast cancer diagnosis during the COVID-19 pandemic in São Paulo, Brazil. Einstein 2021, 19, eAO6721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, T.A.; Camargo, G.; Estevão, R.; Lisboa Coda Dias, N.; Hattori, W.T. Perfil epidemiológico dos casos de neoplasias pulmonares durante a pandemia da COVID-19 no Brasil. Journal of Health & Biological Sciences 2022, 10, e4519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesus, A.S.; Guedes, T.D.S.; Martins, G.B. Impacto da pandemia de COVID-19 no atendimento do serviço de radioterapia em um hospital público de Salvador/BA. Cambio 2021, 20, 369–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabuco, G.; Pires de Oliveira, M.H.P.; Afonso, M.P.D. O impacto da pandemia pela COVID-19 na saúde mental: qual é o papel da Atenção Primária à Saúde? Revista Brasileira de Medicina de Família e Comunidade 2020, 15, 2532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ornell, F.; Schuch, J.B.; Sordi, A.O.; Kessler, F.H.P. “Pandemic fear” and COVID-19: mental health burden and strategies. Brazilian Journal of Psychiatry 2020, 42, 232–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.T.; Yang, Y.; Li, W.; et al. Timely mental health care for the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak is urgently needed. The Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 228–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araujo, L.H.; Baldotto, C.; Castro, G., Jr.; et al. Lung cancer in Brazil. Jornal Brasileiro de Pneumologia 2018, 44, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shuja, K.H.; Aqeel, M.; Jaffar, A.; et al. COVID-19 pandemic and impending global mental health implications. Psychiatria Danubina 2020, 32, 32–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eckhardt, B.L.; Francis, P.A.; Parker, B.S.; Anderson, R.L. Strategies for the discovery and development of therapies for metastatic breast cancer. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 2012, 11, 479–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medford, A.J.; Gillani, R.N.; Park, B.H. Detection of cancer DNA in early stage and metastatic breast cancer patients. In Digital PCR; Karlin-Neumann, G., Bizouarn, F., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2018; Volume 1768, pp. 209–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, I.; Rêgo, J.; Reis, L.; Moura, T. A importância do exame preventivo na detecção precoce do câncer de colo uterino: uma revisão de literatura. Revista Eletrônica Acervo Enfermagem 2021, 10, e6472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, T.C.D.; Fortes, R.C.; Ferrão, P.D.A. Percepção de pacientes oncológicos quanto ao impacto da pandemia de COVID-19 frente ao diagnóstico e tratamento do câncer. Brazilian Journal of Development 2022, 8, 6508–6532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Costa Bezerra, Í.; Cardoso da Rocha, R.; Lucas Pereira Guimarães, G.; Dos Santos Santana, S.; Cunha Silva, Q.G.; Costa Tavares, P.P. Datasus: possibilidade de contribuição no combate à violência contra a mulher no Rio de Janeiro. Saúde Coletiva 2020, 10, 4194–4203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, B.G.D.; Silva, I.O.S.D.; Silva, G.D.O.; Silva, B.D.O.; Guedes, L.S. Um panorama da esquistossomose na Bahia: a realidade de uma doença negligenciada. Revista de APS 2020, 23. Available online: https://periodicos.ufjf.br/index.php/aps/article/view/33837 (accessed on 30 August 2025).

| Cancer site | Gender* | Minas Gerais | Espírito Santo | Rio de Janeiro | São Paulo | P value |

Cramér’s V | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||||

| M | 4773,00 | 63,67 | 978,00 | 59,49 | 2099,00 | 53,26 | 9343,00 | 53,73 | 0,00 | 0,08 | |

| Stomach | F | 2724,00 | 36,33 | 666,00 | 40,51 | 1842,00 | 46,74 | 8047,00 | 46,27 | ||

| Total | 7497,00 | 100,00 | 1644,00 | 100,00 | 3941,00 | 100,00 | 17390,00 | 100,00 | |||

| M | 6819,00 | 46,06 | 1086,00 | 46,69 | 4301,00 | 46,77 | 13393,00 | 49,29 | 0,00 | 0,03 | |

| Colon | F | 7987,00 | 53,94 | 1240,00 | 53,31 | 4896,00 | 53,23 | 13781,00 | 50,71 | ||

| Total | 14806,00 | 100,00 | 2326,00 | 100,00 | 9197,00 | 100,00 | 27174,00 | 100,00 | |||

| M | 3689,00 | 52,23 | 586,00 | 50,60 | 2015,00 | 48,14 | 7586,00 | 54,94 | 0,00 | 0,05 | |

| Rectum | F | 3374,00 | 47,77 | 572,00 | 49,40 | 2171,00 | 51,86 | 6221,00 | 45,06 | ||

| Total | 7063,00 | 100,00 | 1158,00 | 100,00 | 4186,00 | 100,00 | 13807,00 | 100,00 | |||

| M | 4478,00 | 58,13 | 856,00 | 51,85 | 2256,00 | 51,32 | 7867,00 | 53,79 | 0,00 | 0,04 | |

| Lung | F | 3226,00 | 41,87 | 795,00 | 48,15 | 2140,00 | 48,68 | 6759,00 | 46,21 | ||

| Total | 7704,00 | 100,00 | 1651,00 | 100,00 | 4396,00 | 100,00 | 14626,00 | 100,00 | |||

| M | 13506,00 | 45,48 | 3699,00 | 42,77 | 4235,00 | 49,07 | 30526,00 | 47,46 | 0,00 | 0,03 | |

| Non-melanoma Skin | F | 16191,00 | 54,52 | 4949,00 | 57,23 | 4396,00 | 50,93 | 33794,00 | 52,54 | ||

| Total | 29697,00 | 100,00 | 8648,00 | 100,00 | 8631,00 | 100,00 | 64320,00 | 100,00 | 0,04 | ||

| M | 326,00 | 1,00 | 147,00 | 2,36 | 226,00 | 0,97 | 1388,00 | 2,24 | 0,00 | ||

| Breast | F | 32242,00 | 99,00 | 6095,00 | 97,64 | 23099,00 | 99,03 | 60529,00 | 97,76 | ||

| Total | 32568,00 | 100,00 | 6242,00 | 100,00 | 23325,00 | 100,00 | 61917,00 | 100,00 | |||

| M | 29351,00 | 99,95 | 4279,00 | 100,00 | 15229,00 | 99,88 | 49024,00 | 99,93 | 0,01 | 0,01 | |

| Prostate | F | 14,00 | 0,05 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 18,00 | 0,12 | 35,00 | 0,07 | ||

| Total | 29365,00 | 100,00 | 2099,00 | 53,26 | 15247,00 | 100,00 | 49059,00 | 100,00 | |||

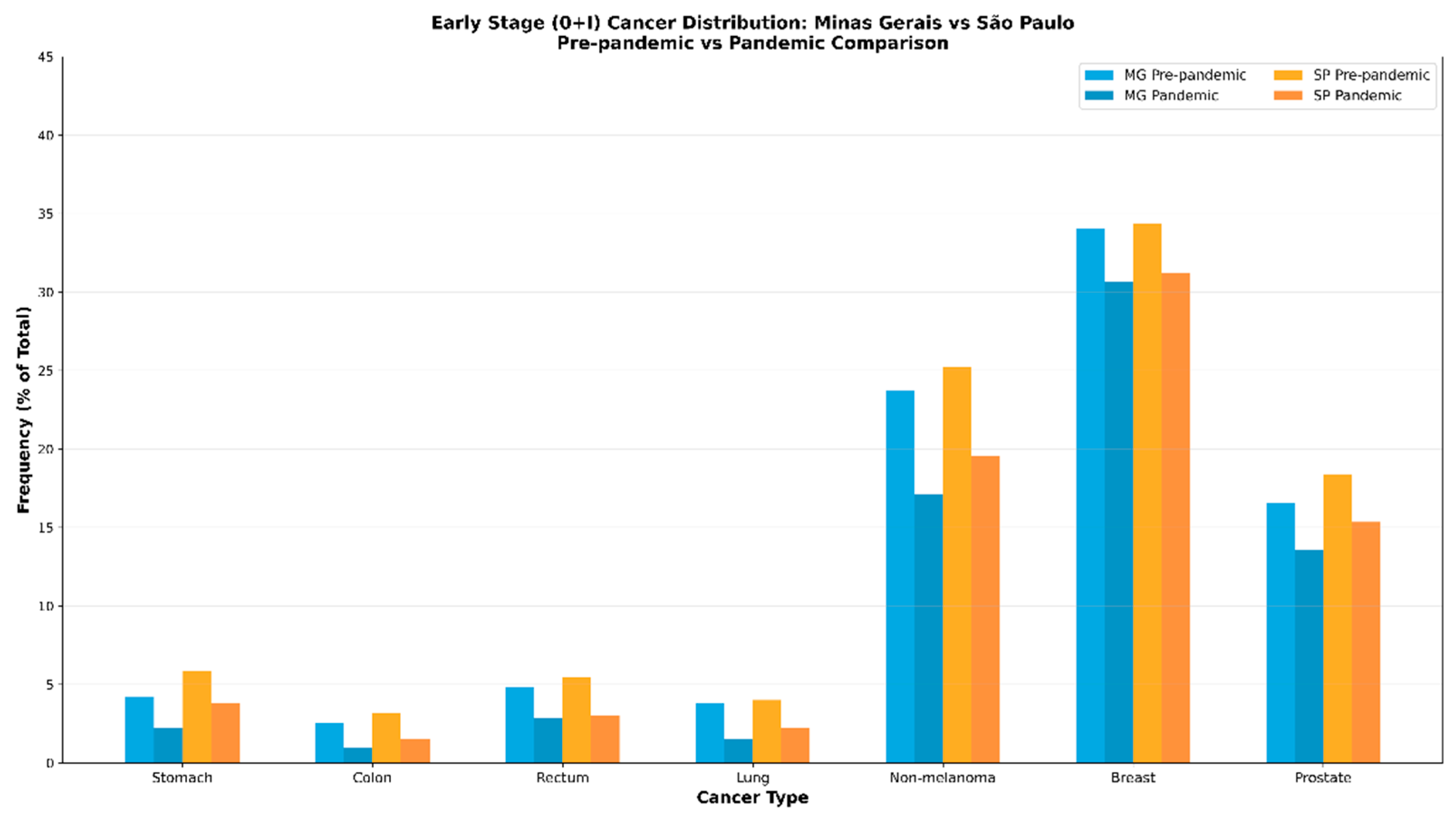

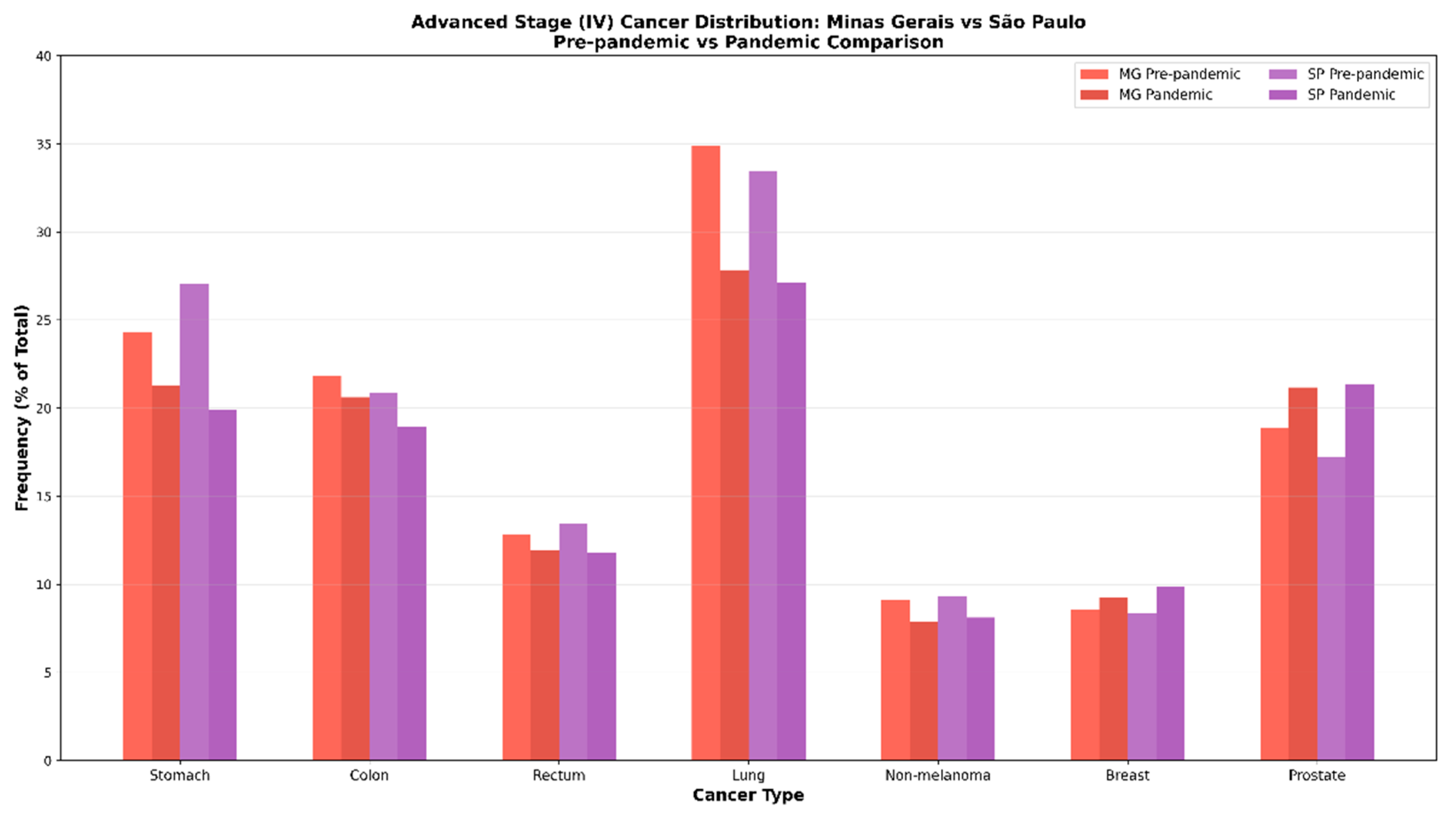

| Cancer Location | Period | Number of cases | Staging | P value | Effect Size* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||||||

| Stomach | Pre | 6379,00 | 315,00 | 203,00 | 818,00 | 2209,00 | 2834,00 | 0,00 | 0,03 | |

| Pan | 4846,00 | 166,00 | 153,00 | 640,00 | 1667,00 | 2220,00 | ||||

| Colon | Pre | 10315,00 | 398,00 | 145,00 | 1681,00 | 3732,00 | 4359,00 | 0,00 | 0,05 | |

| Pan | 8042,00 | 177,00 | 92,00 | 1325,00 | 2905,00 | 3543,00 | ||||

| Rectum | Pre | 9035,00 | 517,00 | 335,00 | 2109,00 | 3834,00 | 2240,00 | 0,00 | 0,05 | |

| Pan | 6724,00 | 283,00 | 325,00 | 1370,00 | 3076,00 | 1670,00 | ||||

| Lung | Pre | 9735,00 | 516,00 | 234,00 | 554,00 | 2480,00 | 5951,00 | 0,00 | 0,05 | |

| Pan | 6592,00 | 223,00 | 175,00 | 316,00 | 1617,00 | 4261,00 | ||||

| Non-melanoma Skin | Pre | 2532,00 | 213,00 | 813,00 | 720,00 | 420,00 | 366,00 | 0,00 | 0,06 | |

| Pan | 1595,00 | 153,00 | 468,00 | 417,00 | 342,00 | 215,00 | ||||

| Breast Cancer | Pre | 42778,00 | 1962,00 | 7822,00 | 12110,00 | 15919,00 | 4965,00 | 0,00 | 0,06 | |

| Pan | 31476,00 | 1227,00 | 4602,00 | 8729,00 | 12465,00 | 4453,00 | ||||

| Prostate Cancer | Pre | 31807,00 | 2816,00 | 3650,00 | 11537,00 | 6173,00 | 7631,00 | 0,00 | 0,06 | |

| Pan | 17432,00 | 1193,00 | 1871,00 | 5716,00 | 3690,00 | 4962,00 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).