1. Introduction

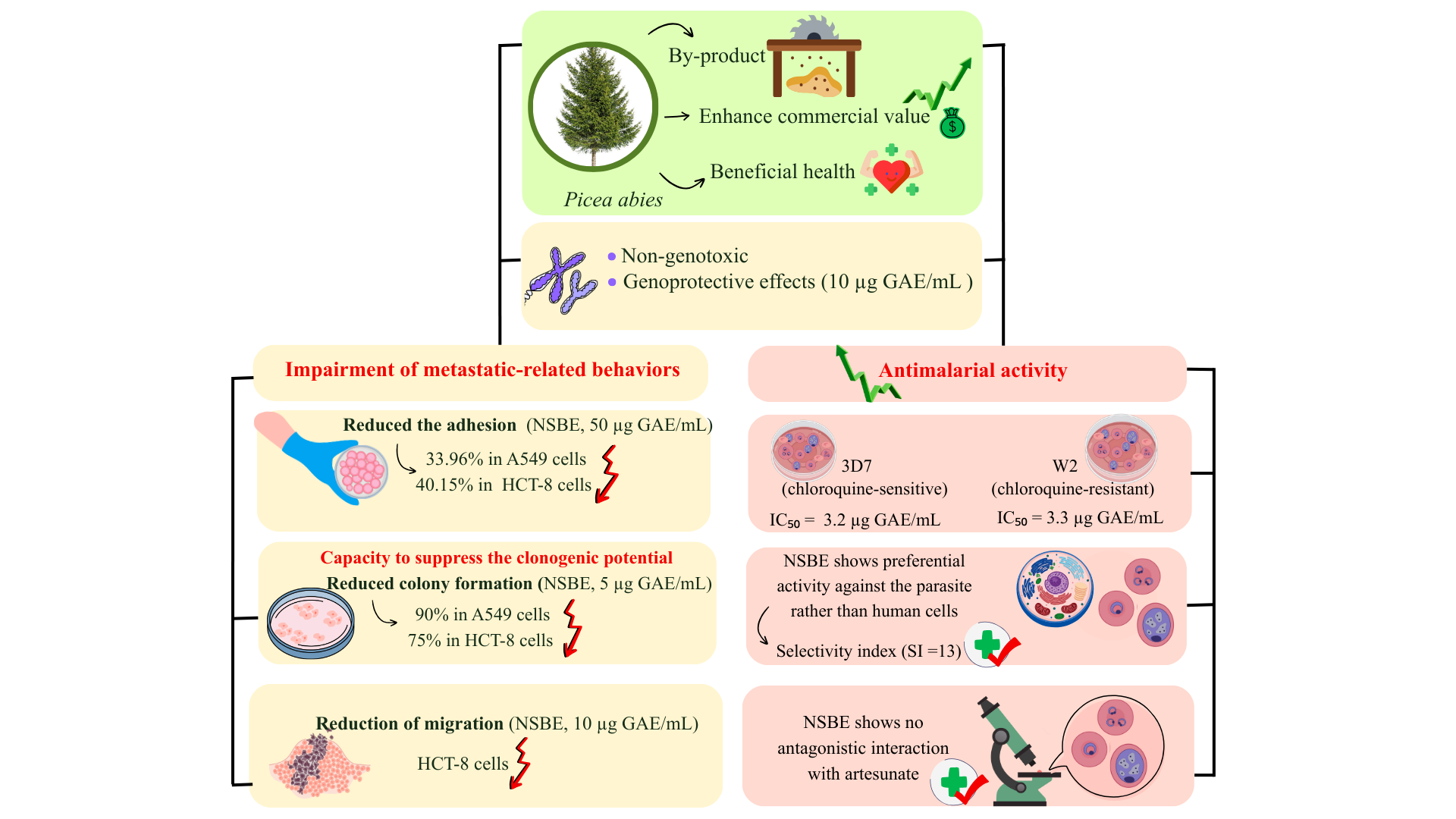

The sawdust from coniferous trees is considered a forest industrial by-product and is usually discarded or combusted to generate energy, leaving a large amount of residue that is not fully utilized. This lignocellulosic biomass contains various polysaccharides, primarily hemicelluloses and polyphenols, which are considered beneficial for health and are gaining interest in technological and functional applications in the food and pharmaceutical industries [1]. In alignment with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 12, which promotes sustainable consumption and production patterns, the valorization of lignocellulosic residues through their integration into biorefinery processes represents a strategic approach toward a more circular and sustainable bioeconomy. Within this framework, such residues, abundant yet underutilized, emerge as promising matrices for the extraction of functional and potentially therapeutic ingredients.

Scientific interest in natural products has intensified, driven by their complex chemical composition, broad range of potential applications, and evidence of positive biological effects on human health. Studies have explored plant by-product extracts rich in polyphenols, such as jabuticaba tree leaf [2]; camu-camu seed [3] ; Tapirira seed extract [4] and reported promising antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antimalarial properties. In line with this growing trend, we investigated the conifer Picea abies (Norway spruce), a species whose by-products represent a valuable source of bioactive polysaccharides and phenolic compounds. The Norway spruce by-product extract (NSBE) is known to contain a galactoglucomannan-rich matrix associated with phenolic constituents such as catechin and epicatechin [5]. The coexistence of these flavanols within the polysaccharide framework has been reported to promote synergistic biological effects, enhancing antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and immunomodulatory responses [5]. From an applied perspective, the chemical composition of NSBE highlights its potential as a multifunctional ingredient derived from renewable forest resources. The combination of galactoglucomannan and phenolic compounds not only supports its technological functionality but also confers biological properties that could be exploited in the development of antioxidant or chemopreventive formulations.

Polyphenols are a significant source of antioxidants, including phenolic acids, flavonoids, and alkylresorcinols, which are recognized for their ability to neutralize free radicals and other reactive oxygen species (ROS) implicated in oxidative stress and chronic diseases [6]. Oxidative stress is a key factor in the onset and progression of non-communicable diseases such as cardiovascular disorders, cancer, and neurodegenerative conditions [7] The antioxidant potential of these compounds primarily arises from three mechanisms: hydrogen atom transfer (HAT); single electron transfer (SET); and metal ion chelation, which collectively mitigate ROS generation and lipid peroxidation, thereby preserving cellular integrity [8]. Beyond their antioxidant role, phenolic compounds have demonstrated cytotoxicity toward cancer cells[9], anti-inflammatory [10], antimicrobial and anti-hypertensive [11], in addition to anti-hemolytic and anti-hyperglycemic activities [12]. In this context, the phenolic compounds identified in the NSBE, particularly catechin and epicatechin, may play a crucial role in modulating oxidative and inflammatory mechanisms associated with cancer progression and metabolic regulation.

In addition to these effects, phenolic compounds have also been reported to exert antiparasitic activity, particularly against Plasmodium falciparum, the etiological agent of malaria. This parasitic infection remains one of the most critical global health challenges, particularly in tropical and subtropical regions, where it is responsible for an estimated 600,000 deaths annually, with the highest incidence occurring in sub-Saharan Africa [13]. The increasing emergence of P. falciparum strains resistant to conventional antimalarial therapies has significantly compromised treatment efficacy, underscoring the urgent need to identify novel bioactive molecules from natural sources with potential therapeutic relevance. Although the antimalarial activity of Norway spruce phenolics has not yet been described, evidence from other plant sources demonstrates that similar compounds, such as epicatechin, catechin, quercetin, and gallic acid, can inhibit or reduce Plasmodium growth in vitro [14-3]. These findings suggest that the phenolic profile of the NSBE, mainly composed of catechin and epicatechin, may also contribute to its potential antimalarial activity.

Despite promising evidence regarding the composition and bioactivity of NSBE, a comprehensive understanding of its toxicological safety, biological activity, and functional potential remains essential, particularly as it represents an extract from an unconventional source intended for applications in food and pharmaceutical formulations derived from renewable resources [15]. From a toxicological standpoint, ensuring the absence of cytotoxic, genotoxic, and mutagenic effects is a fundamental prerequisite for validating novel bioactive ingredients and supporting their safe use in human-related applications. Consequently, exploring the biological mechanisms underlying NSBE activity is crucial for assessing its suitability as a safe and functional bioingredient.

Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the biological effects of the Norway spruce by-product extract (NSBE) in A549 and HCT-8 cell lines. To this end, in vitro assays were performed to investigate its influence on cell viability, adhesion, migration, and colony formation, as well as its genotoxic and antimalarial potential, to elucidate its cytoprotective and chemopreventive effects.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Reagents

Quercetin, chlorogenic acid, (+)-catechin, gallic acid, ferric chloride hexahydrate, and sodium nitrite (Sigma Aldrich, São Paulo, Brazil). Sodium molybdate (Reatec, Colombo, Brazil), 37% hydrochloric acid, 98% sulfuric acid (Fmaia, Indaiatuba, Brazil), and anhydrous sodium acetate (Anidrol, São Paulo, Brazil). Vanillin, sodium hydroxide, ethanol, and aluminium chloride hexahydrate (Dinâmica, Indaiatuba, Brazil). 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT), 2′,7′-dichlorodihydro-fluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA), Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium/Nutrient Mixture F-12 Ham (DMEM/F-12), penicillin-streptomycin, SYBR Gold (S11494), disodium ethylenediaminetetraacetate dihydrate (EDTA), Triton X-100, cisplatin, artesunate, and hydrogen peroxide (Sigma Aldrich, São Paulo, Brazil). Albumax I and Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI)-1640 (Gibco, New York, USA).

2.2. NSBE Phenolic Composition

The sample used in this study was obtained from the industrial processing of Norway spruce (Picea abies), a conifer species rich in galactoglucomannans. The extract was produced through pressurized hot water extraction (PHWE) [16], a green technology that selectively solubilizes hemicelluloses from the sawdust under high temperature and pressure, followed by ultrafiltration and spray drying [17].

The quantification of total phenolics was determined based on the reduction of Fe³⁺ to Fe²⁺ using the Prussian Blue assay [18]. Results were expressed as milligrams of gallic acid equivalents per gram of NSBE (mg GAE/g). The content of ortho-diphenols was assessed by forming a colored complex between the ortho-dihydroxyl groups in the sample and a molybdate-based reagent [19]. Results were expressed as milligrams of chlorogenic acid equivalents per gram of NSBE (mg CAE/g). Tannin quantification was performed using the vanillin–HCl method, in which condensed tannins react with vanillin under acidic conditions to produce a red-colored complex proportional to their concentration [20]. Results were expressed as milligrams of catechin equivalents per gram of NSBE (mg CE/g). Flavonol content was determined using the colorimetric chemical consistency and reduced interference from non-carbohydrate components, results were expressed as milligrams of quercetin equivalents per gram of NSBE (mg QE/g) [21]. Finally, total flavonoids were quantified by the complexation reaction between Al³⁺ ions and the hydroxyl groups on flavonoid structures, yielding a stable chromogenic complex proportional to the flavonoid concentration [22]. Results were expressed as milligrams of catechin equivalents per gram of NSBE (mg CTE/g).

2.3. Cell Lines, Culture Conditions, and Treatment Schedule

HUVEC (normal primary human umbilical vein endothelial cells), HCT-8 (human ileocecal adenocarcinoma cells), and A549 (lung adenocarcinoma epithelial cells) cells were obtained from the Rio de Janeiro Cell Bank (Rio de Janeiro, Brazil). The cell cultures were grown in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium/Nutrient Mixture F-12 Ham (DMEM/F-12) supplemented with 1% penicillin-streptomycin solution (100 U/mL penicillin and 0.1 mg/mL streptomycin) and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO₂.

The NSBE stock solution (1000 µg GAE/mL) was prepared in ultrapure water. For the experimental assays, the corresponding working concentrations were obtained by diluting the stock solution in culture medium. The cisplatin (3.33 mM) and artesunate (0.016 mM) stock solutions were solubilized in NaCl 0.9% and DMSO respectively, and the working concentrations were diluted in culture medium.

2.3. Effect of NSBE on Cell Adhesion

To assess cell adhesion, A549 and HCT-8 cells were treated with NSBE at concentrations ranging from 5 to 75 μg GAE/mL for 1 h. Following this treatment, the cells were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 5 × 10⁴ cells per well and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C in a 5% CO₂ atmosphere. To prevent detachment of adherent cells, a gentle washing step with PBS was performed to remove non-adherent cells. Subsequently, the adherent cells were stained with crystal violet (0.5% v/v) for 30 min, then solubilized with SDS (1% w/v) at 37 °C for 30 min. The absorbance was measured at 570 nm using a microplate reader (Synergy TM 234 H1, Biotek). The results were normalized relative to the control culture [23].

2.4. Antiproliferative Activity of NSBE

The clonogenic assay, also referred to as the colony formation assay, was performed to evaluate the ability of the NSBE to inhibit proliferation and colony-forming capacity in A549, and HCT-8 cell lines[23]. Cells were seeded into 6-well plates at a density of 3 × 10³ cells per well and incubated at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO₂ for 24 h to allow proper cell attachment. Subsequently, the culture medium was replaced with fresh medium supplemented with 2% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and NSBE at concentrations of 2.5 and 5 μg GAE/mL. Cells were exposed to the treatments for 24 h, followed by incubation for an additional 6 days in growth medium containing 2% FBS, which was refreshed every two days. On day 7, the colonies were fixed with methanol for 30 min and stained with 0.5% crystal violet (w/v) for 30 min. Colony quantification was performed using ImageJ software, and the results were expressed as a percentage relative to the control group[25].

2.6. Evaluation of the Genotoxicity of NSBE by Chromosomal Aberrations Assay

The chromosomal aberration assay was performed to evaluate whether the NSBE has protective activity against chromosomal damage or if it induces genotoxicity in the A549 cell line. The cells were seeded in 25 cm² flasks at a density of 5 × 10⁵ cells per flask. The positive control was treated with 4 μM cisplatin, known for its ability to damage DNA, while the negative control received only the culture medium. The treatment groups received isolated concentrations of NSBE (10, 25, and 50 μg GAE/mL) and also these same concentrations in combination with 4 μM cisplatin. After incubation at 37 °C for 48 h, 200 μL of 0.0016% colchicine (Sigma Aldrich, São Paulo, Brazil) solution, an antimitotic known to prevent metaphase, was added to each group, and the flasks were incubated for an additional 6 hours. The cells were then incubated in a hypotonic 75 mM KCl solution for 10 minutes at 37 °C, which promotes chromosome dispersion. They were then fixed and stained with Giemsa stain. To analyze the types of chromosomal aberrations, chromosomal breakage criteria were used. The chromosomal aberration rate (%) was calculated as the percentage of observed chromosomal breaks in relation to the total number of chromosomes analyzed[27].

2.7. In Vitro Antimalarial Properties

The antiplasmodial activity of NSBE was evaluated in vitro against the 3D7 (chloroquine-sensitive) and W2 (chloroquine-resistant) strains of Plasmodium falciparum. The strains were cultivated in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco, New York, USA) supplemented with 10% Albumax II (Gibco, New York, USA) and 4% hematocrit (Erythrocytes, type O+). The plates were incubated at 37°C using the candle jar method, and the medium was replaced every 48 h. Parasitemia was monitored using Panoptic fast-stained blood smears (Renylab, Minas Gerais, Brazil) [28].

After synchronization with 5% sorbitol (Sigma Aldrich, Missouri, EUA) to obtain ring-stage parasites, the antiplasmodial assay was conducted in 96-well microplates using serial dilutions of GGM extract ranging from 40 to 0.31 µg GAE/mL (1:1 v/v). Each well received the parasitized erythrocyte suspension prepared in RPMI 1640 medium containing 2% hematocrit and 1% parasitemia. Non-parasitized erythrocytes (2% hematocrit) were used as negative controls, while untreated infected cultures served as positive controls. Following 48 h of incubation, a lysis buffer solution containing 0.1 µL/mL SYBR Gold nucleic acid gel stain (Sigma Aldrich, São Paulo, Brazil) was added to each well to lyse the erythrocytes and stain parasite DNA. The fluorescence intensity was measured at 485 nm (excitation) and 520 nm (emission) [4]. Following the viability assay with the W2 and 3D7 strains, parasitized cultures at 2% hematocrit and 1% parasitemia were treated with the respective IC₅₀ concentrations of the NSBE, and images were acquired at 0, 8, 24, and 48 h to determine the effect of the extract on the intraerythrocytic cycle of the parasite.

To assess whether the NSBE could potentiate the antiplasmodial effect of artesunate, combination assays were conducted using P. falciparum 3D7 and W2 strains. The IC₅₀ of artesunate was determined in the absence and presence of fixed concentrations (1 or 0.5 µg GAE/mL) of NSBE. Synchronized ring-stage parasites were exposed to serial dilutions of artesunate together with a constant concentration of the extracts for 48 h. Parasite proliferation was quantified using a lysis buffer solution containing the SYBR Gold fluorescence method. The IC₅₀ values obtained for artesunate alone and in combination were compared to determine potentiation or additive effects [29].

In terms of comparison between the cytotoxicity of P. falciparum and cell culture, the cell viability was assessed using the MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) assay, following the methods described by [16]. The selective index (SI) was calculated as the ratio between the IC50 in HUVEC cells and the IC50 of the 3D7 and W2 strains of P. falciparum [30]

3. Results and Discussion

The chemical composition of the NSBE reveals a complex matrix enriched in structurally diverse phenolic constituents. In this study, we quantified key phenolic subclasses, including ortho-diphenolics (10.5 ± 0.2 mg CAE/g), condensed tannins (2.7 ± 0.83 mg CTE/g), flavonols (1.9 ± 0.2 mg QE/g), and total flavonoid content (16.4 ± 1.08 mg CE/g). This profile is consistent with the broader phytochemical composition reported for coniferous species, in which tannins, stilbenes, phenolic acids, and multiple flavonoid classes are commonly identified [30,31,32] Moreover, these findings complement previous analyses performed with the same batch of this NSBE by our research group [5-16]. This chemical profile pointed out that NSBE contains galactoglucomannan (GGM)-rich matrix together with a defined pool of phenolic compounds dominated by epicatechin (≈177 µg/g) and catechin (≈45 µg/g), as well as a total reducing phenolic content of ~33 mg GAE/g. The presence of these structurally varied phenolics reinforces the characterization of the NSBE as a chemically complex extract with potential for multifunctional biological activity. Beyond, NSBE is a complex mixture of polysaccharides and free phenolics chemically integrated into a matrix, contributing to the extract’s stability, chemical profile, and potentially its bioactivity [34-5].

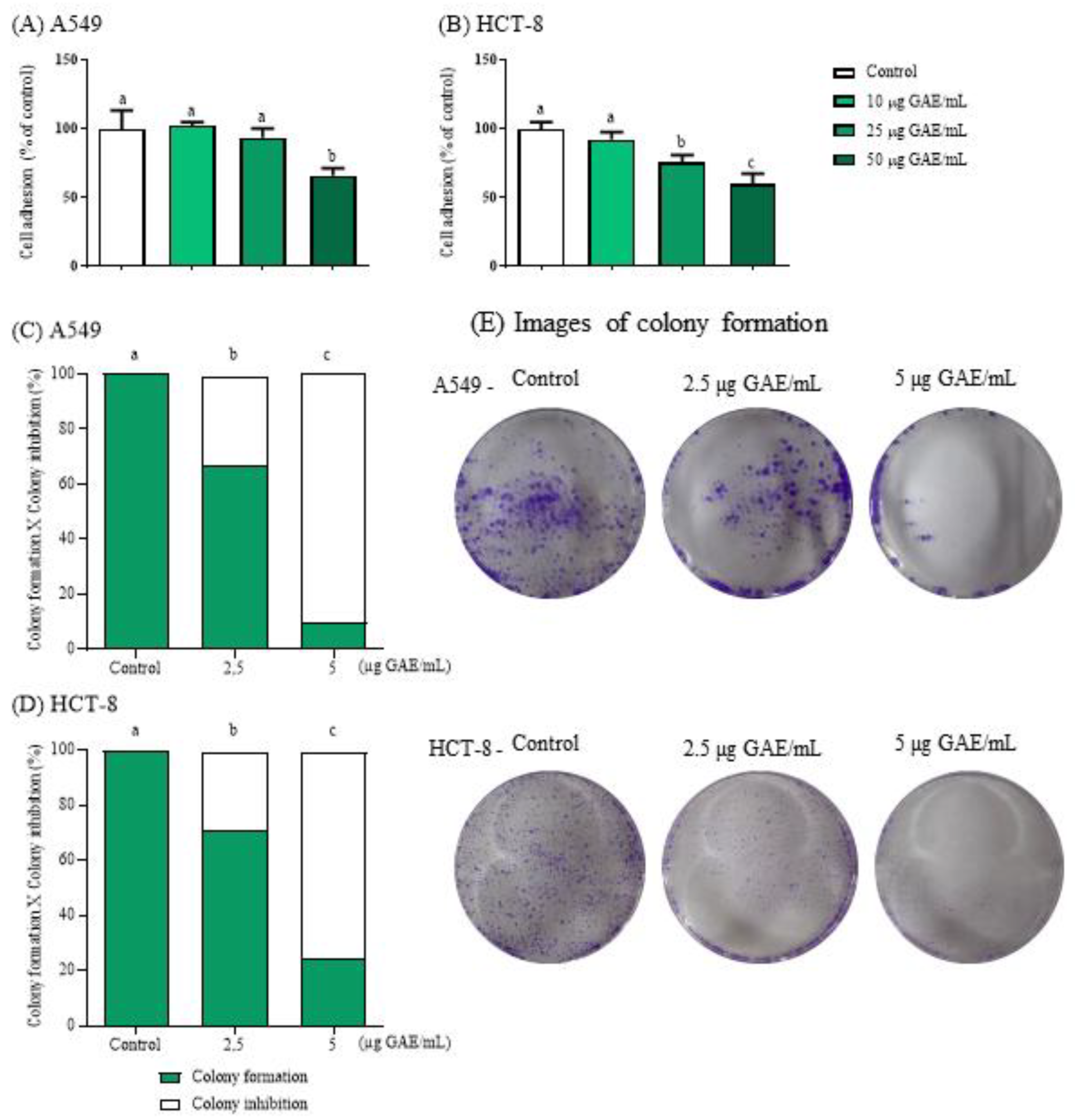

3.2. NSBE Impaired Cell Adhesion

Adhesion and migration are essential steps in the metastatic cascade, enabling tumor cells to detach from the primary site and colonize distant tissues [23]. The cell adhesion assay demonstrated that treatment with the NSBE reduced the adhesion capacity of tumor cell lines in a concentration-dependent manner. In A549 cells, adhesion decreased by 33.96% at 50 µg GAE/mL, while in HCT-8 cells, reductions of 23.76% and 40.15% were observed at 25 and 50 µg GAE/mL, respectively (

Figure 1), indicating that the phenolic constituents of NSBE interfere with cell–substrate interactions relevant to tumor progression.

Importantly, tumor cells inherently display a greater capacity for adhesion due to the overexpression and hyperactivation of adhesion molecules, particularly integrins, which are essential mediators of cell-extracellular matrix adhesion, coupling extracellular ligands to the actin cytoskeleton and coordinating focal adhesion assembly, processes critical for migration and metastatic dissemination [35,36] . In this context, the marked reduction in adhesion observed in A549 and HCT-8 cells suggests that NSBE may interfere with integrin-mediated interactions and the stability of focal adhesion complexes.

Polyphenols compromise focal adhesion dynamics and integrin-dependent interactions, ultimately attenuating tumor cell migration and invasiveness [37]. Epicatechin, a phenolic constituent of NSBE, reinforces this mechanism by modulating the FAK/Src and PI3K/Akt pathways, suppressing MMP-9 expression, and upregulating key metastasis-suppressor genes such as CDH1, PTEN, and BRMS1 [38]. Collectively, these molecular events impair cytoskeletal reorganization, extracellular matrix degradation, and cellular motility. Thus, the anti-adhesive properties observed for NSBE likely arise from the synergistic actions of its phenolic profile, particularly epicatechin, highlighting its potential to disrupt early molecular events involved in metastatic progression.

3.3. NSBE Inhibits the Colony Formation

The proliferation dynamics of A549 and HCT-8 cancer cells after NSBE treatment were assessed using the clonogenic assay. Unlike conventional viability-based cytotoxicity assays, which predominantly capture metabolic inhibition after continuous exposure of cancer cells to the cytotoxic agent, the clonogenic assay evaluates the long-term proliferative potential of tumor cells after treatment withdrawal. This distinction is critical, as many cytotoxic agents induce transient cell-cycle arrest without immediately compromising cell survival, allowing cells to recover once the treatment is removed. By incorporating a 7-day extract-free recovery period, the clonogenic assay provides a measure of true tumor-cell killing and the ability of surviving cells to sustain proliferation [39]. Thus, under these conditions, NSBE demonstrated the ability to reduce the clonogenic potential of both cancer cell lines, exhibiting a dose-dependent antiproliferative effect that reduced colony formation relative to the control by 32% and 90% in A549 cells and by 28% and 75% in HCT-8 cells at 2.5 and 5 µg GAE/mL, respectively (

Figure 1).

The anti-clonogenic effect observed may be closely associated with the ability of the phenolic constituents of NSBE to modulate signaling pathways related to cell-cycle progression and cell survival, which are key mechanisms through which plant extracts inhibit cancer cell proliferation [40,41,42]. In particular, catechin, one of the major phenolics in NSBE, has been reported to influence cell-cycle control and survival pathways in A549 cells, by upregulating the CDK inhibitor p21, suppressing Cyclin E1 and AKT/p-AKT in A549 cells [43]. This is consistent with the nearly 100% reduction in colony formation observed in A549 cells at the 5 µg GAE/mL concentration.

Moreover, NSBE contains diverse bioactive constituents that may act synergistically, as they can target multiple signaling pathways involved in tumor growth and progression more effectively than isolated compounds [41]. In this context, condensed tannins may act in concert with other phenolic constituents present in the extract, modulating markers associated with apoptosis and cell-cycle control, such as Bax, Bcl-2, and the JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway [44]. Thus, the intrinsic phytochemical complexity of the phytocomplex may contribute to the antiproliferative potential observed for NSBE.

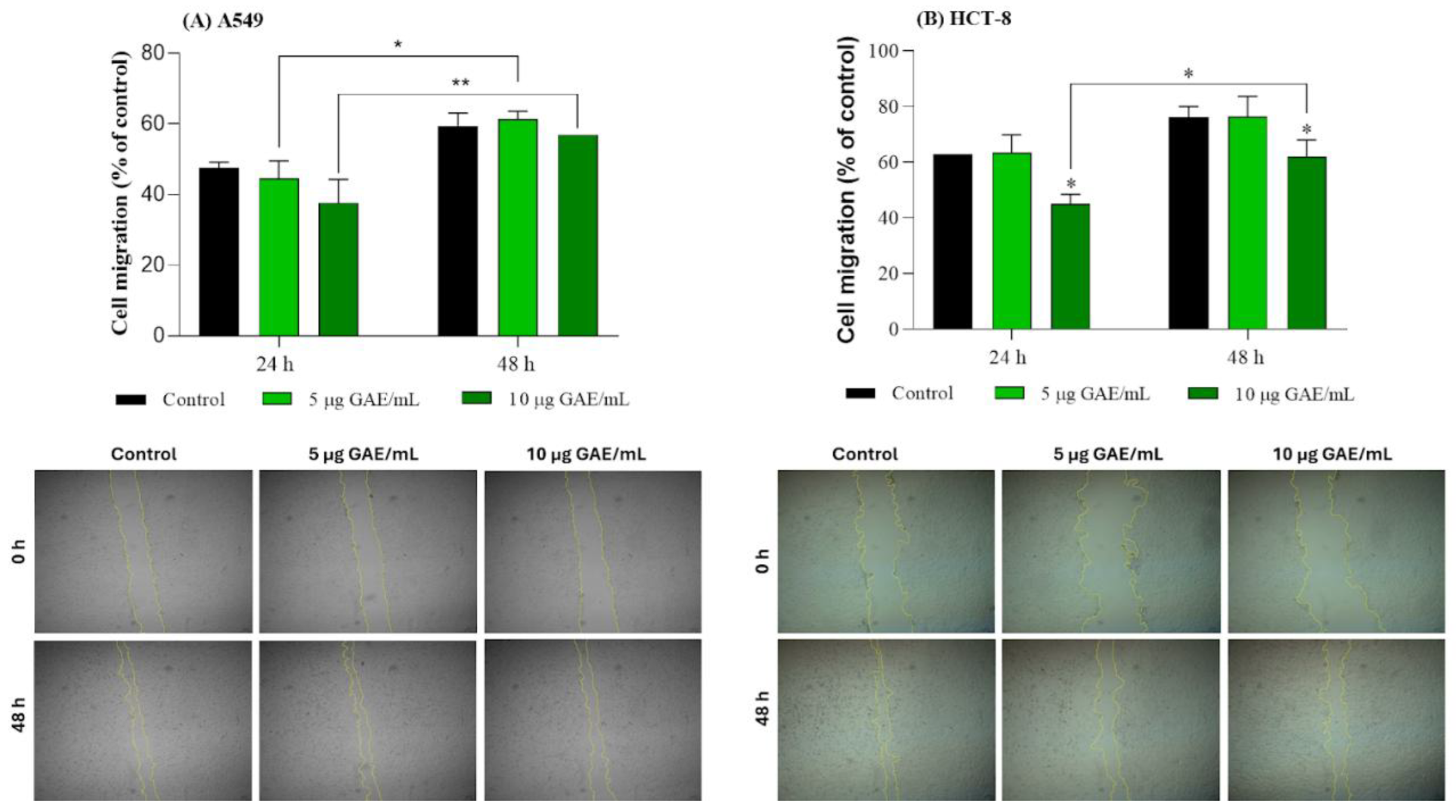

3.4. Migration Profile of A549 and HCT-8 Cells Treated with NSBE

Collective cell migration plays a central role in tissue morphogenesis and wound closure, functioning alongside the well-known single-cell migration used in processes such as immune cell trafficking. In the context of wound-healing assays, epithelial or fibroblast monolayers migrate directionally toward the scratch gap, driven by leader cells at the wound edge and supported by follower cells that maintain structural integrity [45].

In this study, the wound healing assay revealed distinct effects of the NSBE on cell migration in A549 and HCT-8 cells (

Figure 2). In A549 cells, no differences were observed between the control and treatment groups at 24 h and 48 h, although a slight increase in migration was noted after 48 h in the treated groups, associated with the time-dependent closure of the wound, indicating that the variations were primarily driven by temporal progression rather than treatment. Microscopic images supported these findings, as the reduction of the wound area over time occurred similarly across all conditions. In contrast, HCT-8 cells exhibited sensitivity to the extract, with a 24-h treatment of 10 µg GAE/mL already resulting in a reduction of migration compared with the control. This inhibitory effect persisted after 48 h, although its proportion was smaller, indicating that the cells were able to migrate. The micrographs corroborated the quantitative data, showing visibly delayed wound closure in the treated groups relative to the control.

The coordinated movement of cell migration is facilitated by intercellular junctions that remain preserved, allowing neighboring cells to stay physically connected and to transmit mechanical forces across the tissue. Adherens junctions—primarily mediated by homotypic cadherin interactions—are essential for this behavior, ensuring that the advancing front moves as an integrated sheet to progressively close the wound space [45]. The impact on the cell migration process by wound healing can occur through several mechanisms: (i) modulation of adhesion molecules such as αvβ3 and β1, negatively affecting the expression or activity of integrins, reducing the tumor cell's ability to adhere to the ECM and consequently decreasing the driving force for migration; (ii) interference in signaling pathways essential for cell adhesion and migration (PI3K/Akt), suppressing the cell motility necessary to fill the wound; (iii) impact on the cytoskeleton through modifications of actin (such as Rho GTPases proteins), compromising the dynamic reorganization of the cytoskeleton necessary for cell protrusion [45-35]. Therefore, the migration inhibition observed in HCT-8 cells may reflect this dysregulation of adhesive interactions and the signaling pathways associated with them, even though the A549 cells were not affected under the same circumstances. These results suggest a cell line–dependent response and a potential antimetastatic action in colorectal cancer cells.

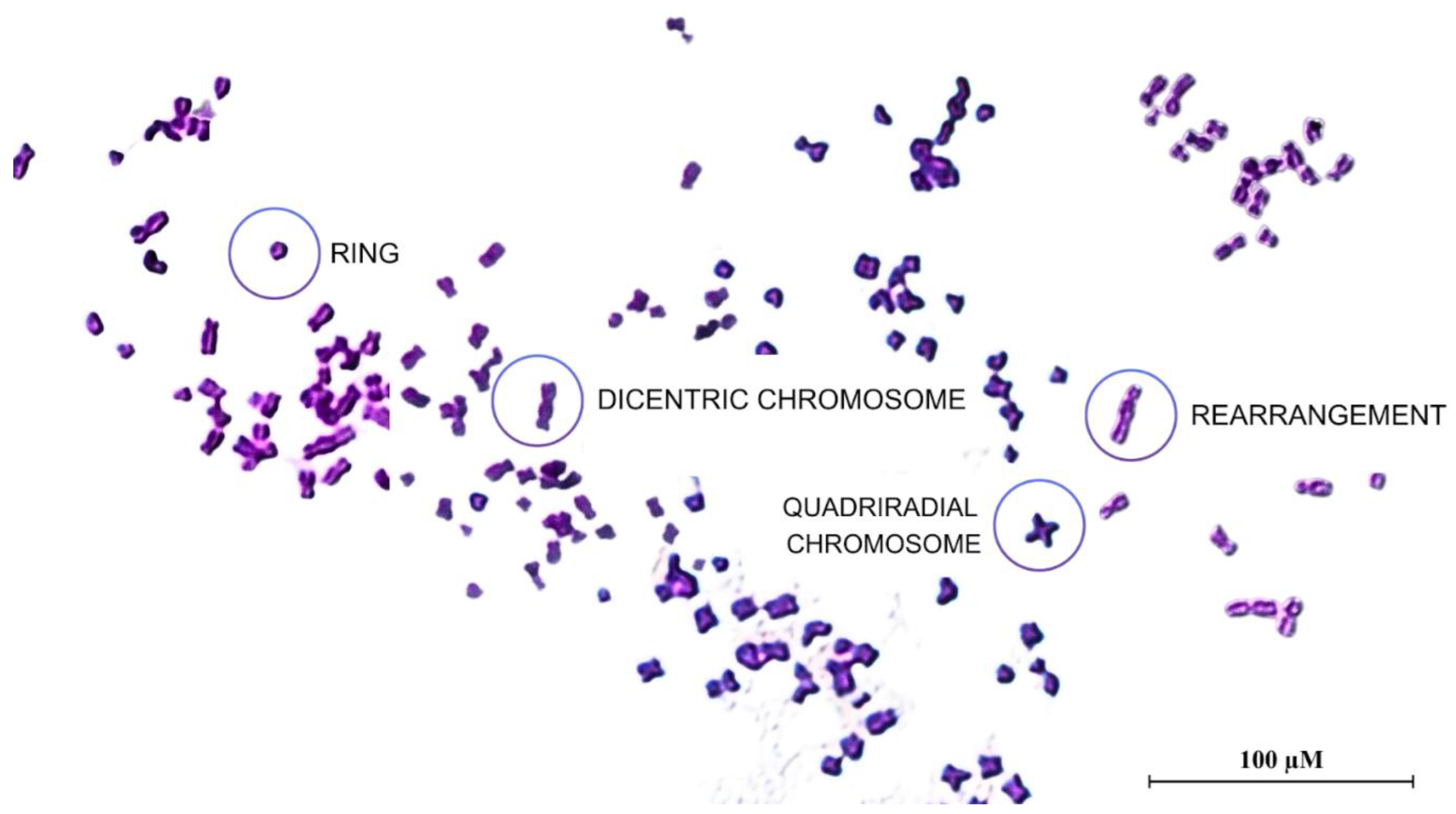

3.5. NSBE Protected Against Cisplatin-Induced Chromosomal Damage

To preserve genomic stability, cells must accurately replicate their DNA before each division and rely on efficient mechanisms to detect, signal, and repair DNA damage [46]. Chromosomal instability, a form of genomic instability observed in cancer and congenital disorders, is commonly associated with the action of mutagens and characterized by numerical or structural chromosomal alterations [47]. In this context, plant extracts have long been recognized for their therapeutic potential; however, evidence also indicates that some extracts may exert toxic, genotoxic, or mutagenic effects. Accordingly, a comprehensive assessment of their genotoxic profile is essential to ensure safety and guide their rational application [48].

Building on this premise, the present study evaluated the potential protective effect of NSBE against cisplatin-induced chromosomal damage in A549 cells. The extract did not induce chromosomal damage in cells exposed only to NSBE, indicating that it is not genotoxic under the tested conditions. Moreover, when combined with cisplatin, the 10 µg GAE/mL concentration reduced chromosomal aberrations relative to the positive control, demonstrating a protective effect on DNA integrity.

We hypothesize that this response is consistent with the extract’s composition, particularly its catechin and epicatechin content [5-17], which is known to modulate cellular signaling pathways such as the MAPK/ERK pathway. Inhibition of this pathway has been associated with reduced oxidative stress; these compounds can mitigate genotoxic damage and preserve genomic stability through their hydroxyl-rich structure, which efficiently scavenges reactive oxygen species. Such mechanisms may have contributed to maintaining chromosomal integrity and, consequently, minimizing the genotoxic effects induced by the chemotherapeutic agent. [49,50]

Additionally, mannose present in the NSBE extract [5] can hinder the efficient utilization of glucose, the preferred energy and biosynthetic substrate in cancer cells, a metabolic disruption that has been associated with increased cellular sensitivity to DNA-damaging chemotherapeutic agents, such as cisplatin, thereby potentially enhancing the cellular response to this drug [51]. Taken together, the protective, and sensitizing properties of NSBE suggest that this extract may modulate key cellular pathways to preserve genomic stability during cisplatin treatment, highlighting its potential value in therapeutic contexts.

Table 1.

Results of the chromosomal aberrations assay in A549 cells treated with NSBE in vitro.

Table 1.

Results of the chromosomal aberrations assay in A549 cells treated with NSBE in vitro.

| NSBE |

CIS |

TC |

Aberrant Type |

TNCA |

CA (%) |

NSBE |

CIS |

TC |

Aberrant Type |

TNCA |

CA (%) |

| |

R |

DC |

QC |

RE |

|

R |

DC |

QC |

RE |

| NC |

- |

5072 |

|

1 |

11 |

6 |

31 |

49 |

0.97 a

|

NC |

- |

5072 |

|

1 |

11 |

6 |

31 |

49 |

0.97 a

|

| PC |

yes |

5323 |

|

2 |

17 |

5 |

51 |

75 |

1.41b

|

PC |

yes |

5323 |

|

2 |

17 |

5 |

51 |

75 |

1.41 b

|

| 0 |

- |

5263 |

|

1 |

21 |

3 |

28 |

53 |

1.01abc

|

10 |

yes |

5656 |

|

0 |

7 |

3 |

40 |

50 |

0.88ac

|

| 25 |

- |

5288 |

|

2 |

1 |

1 |

40 |

44 |

0.83ac

|

25 |

yes |

4935 |

|

2 |

4 |

1 |

44 |

51 |

1.03abc

|

| 50 |

- |

4869 |

|

0 |

9 |

0 |

32 |

41 |

0.84ac

|

50 |

yes |

4890 |

|

1 |

11 |

1 |

45 |

58 |

1.19abc

|

Figure 3.

Photomicrographs (1000×) of metaphase plates of A549 cells. Different kinds of chromosomal aberrations were observed, such as ring (R), dicentric chromosome (DC), quadriradial chromosome (QC), and rearrangement (RE).

Figure 3.

Photomicrographs (1000×) of metaphase plates of A549 cells. Different kinds of chromosomal aberrations were observed, such as ring (R), dicentric chromosome (DC), quadriradial chromosome (QC), and rearrangement (RE).

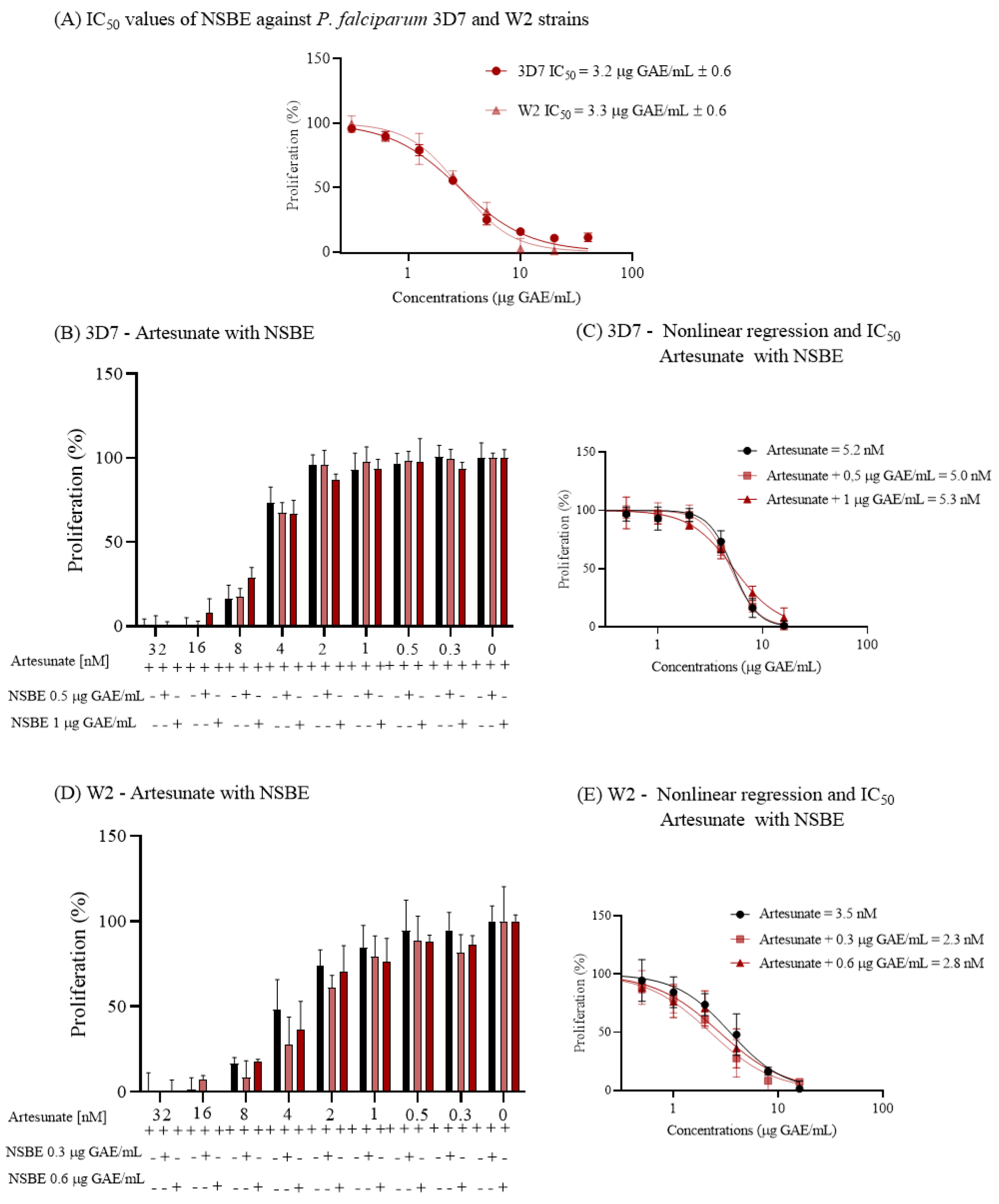

3.6. NSBE Exerts Antimalarial Activity in 3D7 and W2 Strains

The antiplasmodial activity of NSBE was assessed against the 3D7 (chloroquine-sensitive) and W2 (chloroquine-resistant) strains of Plasmodium falciparum. The extract exhibited potent inhibition of parasite proliferation, with IC₅₀ values of 3.2 ± 0.6 and 3.3 ± 0.6 µg GAE/mL for 3D7 and W2, respectively (

Figure 5). These nearly identical IC₅₀ values indicate that NSBE’s inhibitory activity is not influenced by chloroquine resistance and lies within the range typically considered promising for crude plant extracts in antimalarial screening.

Combination assays with artesunate demonstrated that NSBE does not alter the efficacy of this front-line antimalarial. For both strains, the IC₅₀ values of artesunate remained essentially unchanged in the presence of fixed NSBE concentrations, and the corresponding dose–response curves overlapped with the control (

Figure 5). This absence of potentiation or antagonism suggests that NSBE and artesunate act through independent or non-interacting mechanisms under the tested conditions.

Literature consistently shows that extracts with higher phenolic abundance tend to exhibit stronger antiplasmodial activity, both in chloroquine-sensitive and -resistant strains [52]. Given this context, flavanols such as catechin and epicatechin, together with tannins and other phenolic subclasses typically associated with NSBE, likely contribute to the observed activity [53,54]. Polyphenol-rich extracts and structurally related compounds have been reported to inhibit P. falciparum proliferation, supporting the hypothesis that the phenolic fraction, not the polysaccharidic backbone is the main driver of the antiplasmodial effect [55].

Still, it is improbable that a single molecule fully explains the IC₅₀ values observed. Plant extracts often behave as phytocomplexes, in which different constituents act additively or synergistically on multiple parasite processes, including redox balance, membrane integrity, and metabolic pathways [56]. In NSBE, the coexistence of epicatechin, catechin, and other redox-active phenolics within compounds from sawdust matrix may improve stability, uptake, or interaction with parasite structures, collectively driving growth inhibition in the low concentration range[57,58,59,60,61,62].

The lack of artesunate interaction reinforces a non-overlapping, broad cytostatic/cytotoxic mode of action rather than a single stage-specific target. The selectivity index (SI ≈ 13), calculated from the IC₅₀ in HUVEC cells (43 µg GAE/mL), further highlights the preferential action of NSBE on the parasite relative to mammalian cells, surpassing the SI ≥ 10 threshold commonly considered suitable for antimalarial candidates [63].

Figure 4.

In vitro antiplasmodial activity of Norway spruce by-product extract (NSBE) against Plasmodium falciparum 3D7 and W2 strains and its interaction with artesunate. (A) Dose–response curves of NSBE against 3D7 (chloroquine-sensitive) and W2 (chloroquine-resistant) strains after 48 h of incubation, showing IC₅₀ values of 3.2 ± 0.6 and 3.3 ± 0.6 µg GAE/mL, respectively. Parasite proliferation was quantified by SYBR Gold fluorescence. (B, D) Effect of NSBE (0.5 or 1.0 µg GAE/mL, fixed concentrations) on artesunate dose–response curves in 3D7 (B) and W2 (D) strains. (C, E) Nonlinear regression analysis of artesunate IC₅₀ values in the absence and presence of NSBE in 3D7 (C) and W2 (E), showing no significant shifts in potency and indicating a lack of synergistic or antagonistic interaction under the conditions tested.

Figure 4.

In vitro antiplasmodial activity of Norway spruce by-product extract (NSBE) against Plasmodium falciparum 3D7 and W2 strains and its interaction with artesunate. (A) Dose–response curves of NSBE against 3D7 (chloroquine-sensitive) and W2 (chloroquine-resistant) strains after 48 h of incubation, showing IC₅₀ values of 3.2 ± 0.6 and 3.3 ± 0.6 µg GAE/mL, respectively. Parasite proliferation was quantified by SYBR Gold fluorescence. (B, D) Effect of NSBE (0.5 or 1.0 µg GAE/mL, fixed concentrations) on artesunate dose–response curves in 3D7 (B) and W2 (D) strains. (C, E) Nonlinear regression analysis of artesunate IC₅₀ values in the absence and presence of NSBE in 3D7 (C) and W2 (E), showing no significant shifts in potency and indicating a lack of synergistic or antagonistic interaction under the conditions tested.

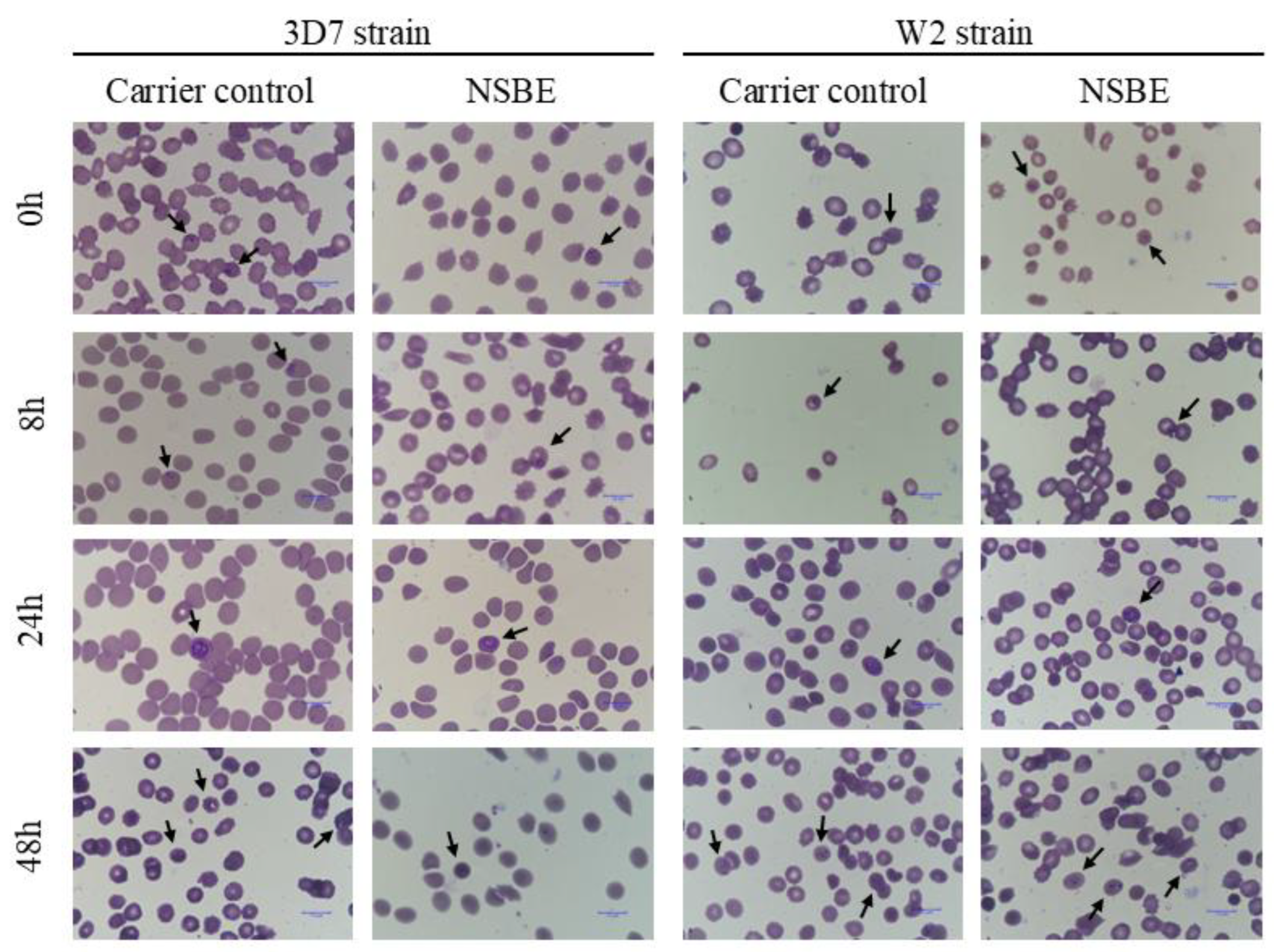

3.7. Microscopic Evaluation of the Intraerythrocytic Cycle

Microscopic analysis of Giemsa-stained thin smears at 0, 8, 24, and 48 h showed no morphological abnormalities or evidence of stage-specific arrest in parasites exposed to NSBE (

Figure 5). Rings, trophozoites, and schizonts preserved their typical morphology and progressed normally through the erythrocytic cycle when compared with untreated controls. These findings indicate that NSBE does not induce clear morphological alterations detectable by light microscopy, suggesting that its antiplasmodial activity is more likely driven by metabolic or redox-related perturbations than by interference with a discrete morphological transition.

In summary, NSBE demonstrates potent antiplasmodial activity in vitro, effectively inhibiting the growth of both chloroquine-sensitive and resistant P. falciparum strains, with no observed impact on the intraerythrocytic progression or interaction with artesunate.

Figure 5.

Microscopy images of synchronized P. falciparum 3D7 and W2 strains at different time points, stained using the rapid panoptic method. Smears show parasites cultured under control conditions (RPMI medium containing 10% Albumax II) and treated with NSBE at the IC₅₀ values for each strain (3D7: 3.2 µg GAE/mL; W2: 3.3 µg GAE/mL). Arrows indicate intraerythrocytic structures.

Figure 5.

Microscopy images of synchronized P. falciparum 3D7 and W2 strains at different time points, stained using the rapid panoptic method. Smears show parasites cultured under control conditions (RPMI medium containing 10% Albumax II) and treated with NSBE at the IC₅₀ values for each strain (3D7: 3.2 µg GAE/mL; W2: 3.3 µg GAE/mL). Arrows indicate intraerythrocytic structures.

5. Conclusions

The findings of this study demonstrate that the Norway spruce by-product extract (NSBE) exhibits relevant biological activities that support its potential as a multifunctional bioingredient. The extract reduced adhesion and clonogenic capacity in A549 and HCT-8 tumor cells, indicating antiproliferative and antimetastatic effects. Although migration inhibition occurred only in HCT-8 cells, the response suggests a cell line–dependent sensitivity. NSBE did not induce chromosomal damage and showed a protective effect against cisplatin at 10 µg GAE/mL, reinforcing its toxicological safety under the tested conditions. Additionally, the extract displayed potent antiplasmodial activity in both chloroquine-sensitive and -resistant Plasmodium falciparum strains, with IC₅₀ values below 3.5 µg GAE/mL and a selectivity index above the recommended threshold for natural antimalarial candidates.

Overall, the results indicate that NSBE, obtained from a renewable forest by-product, combines safety and biological efficacy, supporting its potential application in the development of functional ingredients for pharmaceutical or nutraceutical purposes. Altogether, these results emphasize the therapeutic relevance of NSBE and support future in vivo and mechanistic studies to validate its safety, efficacy, and potential applications as a multifunctional bioingredient.

Author Contributions

J.C.C.C. and G.F.: conceptualization, formal analysis, methodology, data curation, investigation, project administration, writing—original draft, writing - review & editing; N.A.B., T.M.C., F.V.V. and G.K.P.d.S: formal analysis, methodology; writing original draft; I.B.V. and M.C.: writing original draft; A.d.S.L.: formal analysis, methodology; writing original draft, conceptualization, funding acquisition, supervision, data curation, writing—review and editing.; P.K.: resources; review and editing; L.A.: conceptualization, funding acquisition, supervision, data curation, writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the financial support provided by Minas Gerais State Research Support Foundation (FAPEMIG) [grant number: APQ- 04299-22; APQ-02221-24] and National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) [grant number: 422096-2021-0; 304302-2025-2]. MC is fellow of the Beatriu de Pinós programme (2023 BP 00050), funded by the Agència de Gestió d’Ajuts Universitaris i de Recerca (AGAUR), Generalitat de Catalunya. IBV is a fellow from the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP); IBV FAPESP process number: 2022/09526-4

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

References

- Zhao H, Mikkonen KS, Kilpeläinen PO, Lehtonen MI. Spruce Galactoglucomannan-Stabilized Emulsions Enhance Bioaccessibility of Bioactive Compounds. Foods. 2020 May 23;9(5):672. [CrossRef]

- dos Santos Lima A, Cruz TM, Mohammadi N, da Silva Cruz L, da Rocha Gaban de Oliveira R, Vieira FV, et al. Turning agro-food waste into resources: Exploring the antioxidant effects of bioactive compounds bioaccessibility from digested jabuticaba tree leaf extract. Food Chem. 2025 Mar;469:142538. [CrossRef]

- do Carmo MAV, Fidelis M, Sanchez CA, Castro AP, Camps I, Colombo FA, et al. Camu-camu (Myrciaria dubia) seeds as a novel source of bioactive compounds with promising antimalarial and antischistosomicidal properties. Food Research International. 2020 Oct;136:109334.

- Crispim M, Silva TC, Lima A dos S, Cruz L da S, Bento NA, Cruz TM, et al. From Traditional Amazon Use to Food Applications: Tapirira guianensis Seed Extracts as a Triad of Antiproliferative Effect, Oxidative Defense, and Antimalarial Activity. Foods. 2025 Feb 1;14(3):467. [CrossRef]

- dos Santos Lima A, de Oliveira Pedreira FR, Bento NA, Novaes RD, dos Santos EG, de Almeida Lima GD, et al. Digested galactoglucomannan mitigates oxidative stress in human cells, restores gut bacterial diversity, and provides chemopreventive protection against colon cancer in rats. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024 Oct;277:133986.

- Rathod NB, Elabed N, Punia S, Ozogul F, Kim SK, Rocha JM. Recent Developments in Polyphenol Applications on Human Health: A Review with Current Knowledge. Plants. 2023 Mar 7;12(6):1217. [CrossRef]

- Jomova K, Raptova R, Alomar SY, Alwasel SH, Nepovimova E, Kuca K, et al. Reactive oxygen species, toxicity, oxidative stress, and antioxidants: chronic diseases and aging. Arch Toxicol. 2023 Oct 19;97(10):2499–574. [CrossRef]

- Leopoldini M, Russo N, Toscano M. The molecular basis of working mechanism of natural polyphenolic antioxidants. Food Chem. 2011 Mar;125(2):288–306.

- Tsouh Fokou PV, Kamdem Pone B, Appiah-Oppong R, Ngouana V, Bakarnga-Via I, Ntieche Woutouoba D, et al. An Update on Antitumor Efficacy of Catechins: From Molecular Mechanisms to Clinical Applications. Food Sci Nutr. 2025 Apr 18;13(4).

- Al-Khayri JM, Sahana GR, Nagella P, Joseph B V., Alessa FM, Al-Mssallem MQ. Flavonoids as Potential Anti-Inflammatory Molecules: A Review. Molecules. 2022 May 2;27(9):2901.

- Willemann JR, Escher GB, Kaneshima T, Furtado MM, Sant’Ana AS, Vieira do Carmo MA, et al. Response surface optimization of phenolic compounds extraction from camu-camu ( Myrciaria dubia ) seed coat based on chemical properties and bioactivity. J Food Sci. 2020 Aug 9;85(8):2358–67.

- Schechtel SL, de Matos VCR, Santos JS, Cruz TM, Marques MB, Wen M, et al. Flaxleaf Fleabane Leaves ( Conyza bonariensis ), A New Functional Nonconventional Edible Plant? J Food Sci. 2019 Dec 13;84(12):3473–82.

- World Health Organization. World Malaria Report 2024: Addressing inequality in the global response to malaria. WHO [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Dec 1]; Available from: https://www.who.int/teams/global-malaria-programme/reports/world-malaria-report-2024.

- de Noronha MC, Cardoso RR, dos Santos D’Almeida CT, Vieira do Carmo MA, Azevedo L, Maltarollo VG, et al. Black tea kombucha: Physicochemical, microbiological and comprehensive phenolic profile changes during fermentation, and antimalarial activity. Food Chem. 2022 Aug;384:132515. [CrossRef]

- Rifna EJ, Dwivedi M, Seth D, Pradhan RC, Sarangi PK, Tiwari BK. Transforming the potential of renewable food waste biomass towards food security and supply sustainability. Sustain Chem Pharm. 2024 Apr;38:101515. [CrossRef]

- Kilpeläinen PO, Hautala SS, Byman OO, Tanner LJ, Korpinen RI, Lillandt MKJ, et al. Pressurized hot water flow-through extraction system scale up from the laboratory to the pilot scale. Green Chem. 2014;16(6):3186–94. [CrossRef]

- Granato D, Reshamwala D, Korpinen R, Azevedo L, Vieira do Carmo MA, Cruz TM, et al. From the forest to the plate – Hemicelluloses, galactoglucomannan, glucuronoxylan, and phenolic-rich extracts from unconventional sources as functional food ingredients. Food Chem. 2022 Jul;381:132284.

- Margraf T, Karnopp AR, Rosso ND, Granato D. Comparison between Folin-Ciocalteu and Prussian Blue Assays to Estimate The Total Phenolic Content of Juices and Teas Using 96-Well Microplates. J Food Sci. 2015 Nov 8;80(11).

- Maestro Durán M, Borja Padilla R, Martín Martín A, Fiestas Ros de Ursinos JA, Alba Mendoza J. Bíodegradación de ios compuestos fenólícos presentes en el alpechín. Grasas y Aceites. 1991;

- Horszwald A, Andlauer W. Characterisation of bioactive compounds in berry juices by traditional photometric and modern microplate methods. J Berry Res. 2011 Nov;1(4):189–99. [CrossRef]

- A. I. Yermako, V. V. Arasimov, N. P. Yarosh. Methods of Biochemical Analysis of Plants. Agropromizdat. 1987;

- Zhishen J, Mengcheng T, Jianming W. The determination of flavonoid contents in mulberry and their scavenging effects on superoxide radicals. Food Chem. 1999 Mar;64(4):555–9.

- Pijuan J, Barceló C, Moreno DF, Maiques O, Sisó P, Marti RM, et al. In vitro Cell Migration, Invasion, and Adhesion Assays: From Cell Imaging to Data Analysis. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2019 Jun 14;7. [CrossRef]

- Franken N, Rodermond H, Stap J. Clonogenic assay of cells in vitro. 2006; [CrossRef]

- Vale JA do, Rodrigues MP, Lima ÂMA, Santiago SS, Lima GD de A, Almeida AA, et al. Synthesis of cinnamic acid ester derivatives with antiproliferative and antimetastatic activities on murine melanoma cells. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2022 Apr;148:112689.

- Sampaio JG, Pressete CG, Costa AV, Martins FT, de Almeida Lima GD, Ionta M, et al. Methoxylated Cinnamic Esters with Antiproliferative and Antimetastatic Effects on Human Lung Adenocarcinoma Cells. Life. 2023 Jun 22;13(7):1428. [CrossRef]

- Auerbach A, Rogatko A, Schroeder-Kurth T. International Fanconi Anemia Registry: relation of clinical symptoms to diepoxybutane sensitivity. Blood. 1989 Feb 1;73(2):391–6.

- Trager W, Jensen JB. Human Malaria Parasites in Continuous Culture. Science (1979). 1976 Aug 20;193(4254):673–5.

- Sannella AR, Messori L, Casini A, Francesco Vincieri F, Bilia AR, Majori G, et al. Antimalarial properties of green tea. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007 Feb;353(1):177–81.

- do Carmo MAV, Pressete CG, Marques MJ, Granato D, Azevedo L. Polyphenols as potential antiproliferative agents: scientific trends. Curr Opin Food Sci. 2018 Dec;24:26–35. [CrossRef]

- Metsämuuronen S, Sirén H. Bioactive phenolic compounds, metabolism and properties: a review on valuable chemical compounds in Scots pine and Norway spruce. Phytochemistry Reviews. 2019 Jun 22;18(3):623–64.

- Spinelli S, Costa C, Conte A, La Porta N, Padalino L, Del Nobile MA. Bioactive Compounds from Norway Spruce Bark: Comparison Among Sustainable Extraction Techniques for Potential Food Applications. Foods. 2019 Oct 23;8(11):524. [CrossRef]

- Kim KJ, Hwang ES, Kim MJ, Park JH, Kim DO. Antihypertensive Effects of Polyphenolic Extract from Korean Red Pine (Pinus densiflora Sieb. et Zucc.) Bark in Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats. Antioxidants. 2020 Apr 19;9(4):333.

- Pitkänen L, Heinonen M, Mikkonen KS. Safety considerations of plant polysaccharides for food use: a case study on phenolic-rich softwood galactoglucomannan extract. Food Funct. 2018;9(4):1931–43.

- Ruan Y, Chen L, Xie D, Luo T, Xu Y, Ye T, et al. Mechanisms of Cell Adhesion Molecules in Endocrine-Related Cancers: A Concise Outlook. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022 Apr 7;13. [CrossRef]

- Michael M, Parsons M. New perspectives on integrin-dependent adhesions. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2020 Apr;63:31–7. [CrossRef]

- Carrano R, Grande M, Leti Maggio E, Zucca C, Bei R, Palumbo C, et al. Dietary Polyphenols Effects on Focal Adhesion Plaques and Metalloproteinases in Cancer Invasiveness. Biomedicines. 2024 Feb 21;12(3):482. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Durán J, Luna A, Portilla A, Martínez P, Ceballos G, Ortíz-Flores MÁ, et al. (−)-Epicatechin Inhibits Metastatic-Associated Proliferation, Migration, and Invasion of Murine Breast Cancer Cells In Vitro. Molecules. 2023 Aug 24;28(17):6229.

- Eastman A. Improving anticancer drug development begins with cell culture: misinformation perpetrated by the misuse of cytotoxicity assays. Oncotarget. 2017 Jan 31;8(5):8854–66.

- Paes LT, D’Almeida CT dos S, do Carmo MAV, da Silva Cruz L, Bubula de Souza A, Viana LM, et al. Phenolic-rich extracts from toasted white and tannin sorghum flours have distinct profiles influencing their antioxidant, antiproliferative, anti-adhesive, anti-invasive, and antimalarial activities. Food Research International. 2024 Jan;176:113739. [CrossRef]

- Hołota M, Posmyk MM. Nature-Inspired Strategies in Cancer Management: The Potential of Plant Extracts in Modulating Tumour Biology. Int J Mol Sci. 2025 Jul 18;26(14):6894.

- Russo GL, Stampone E, Cervellera C, Borriello A. Regulation of p27Kip1 and p57Kip2 Functions by Natural Polyphenols. Biomolecules. 2020 Sep 13;10(9):1316.

- Sun H, Yin M, Hao D, Shen Y. Anti-Cancer Activity of Catechin against A549 Lung Carcinoma Cells by Induction of Cyclin Kinase Inhibitor p21 and Suppression of Cyclin E1 and P–AKT. Applied Sciences. 2020 Mar 19;10(6):2065.

- Wu Y, Liu C, Niu Y, Xia J, Fan L, Wu Y, et al. Procyanidins mediates antineoplastic effects against non-small cell lung cancer via the JAK2/STAT3 pathway. Transl Cancer Res. 2021 May;10(5):2023–35.

- Janiszewska M, Primi MC, Izard T. Cell adhesion in cancer: Beyond the migration of single cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2020 Feb;295(8):2495–505. [CrossRef]

- Paniagua I, Jacobs J. Quantification of Chromosomal Aberrations in Mammalian Cells. Bio Protoc. 2023;13(16).

- Hemminki K, Niazi Y, Vodickova L, Vodicka P, Försti A. Genetic and environmental associations of nonspecific chromosomal aberrations. Mutagenesis. 2025 Mar 15;40(1):30–8.

- Al-Naqeb G, Kalmpourtzidou A, Giampieri F, De Giuseppe R, Cena H. Genotoxic and antigenotoxic medicinal plant extracts and their main phytochemicals: “A review.” Front Pharmacol. 2024 Nov 29;15.

- del Carmen García-Rodríguez M, Kacew S. Green tea catechins: protectors or threats to DNA? A review of their antigenotoxic and genotoxic effects. Arch Toxicol. 2025 Sep 13;99(9):3485–504.

- Lee S, Rauch J, Kolch W. Targeting MAPK Signaling in Cancer: Mechanisms of Drug Resistance and Sensitivity. Int J Mol Sci. 2020 Feb 7;21(3):1102.

- Harada Y. Manipulating mannose metabolism as a potential anticancer strategy. FEBS J. 2025 Apr 11;292(7):1505–19. [CrossRef]

- Mamede L, Ledoux A, Jansen O, Frédérich M. Natural Phenolic Compounds and Derivatives as Potential Antimalarial Agents. Planta Med. 2020 Jun 23;86(09):585–618. [CrossRef]

- Dantas TBV, Moura IMR, da Costa RP, de Souza GE, Severino RP, Consolaro HN, et al. Tandem Mass Spectrometry and Bio-Guided Isolation of Secondary Metabolites With Antiplasmodial Activity From Dalbergia miscolobium Bark. Chem Biodivers. 2025 Sep 8;

- Tayler NM, De Jesús R, Spadafora R, Coronado LM, Spadafora C. Antiplasmodial activity of Cocos nucifera leaves in Plasmodium berghei-infected mice. Journal of Parasitic Diseases. 2020 Jun 9;44(2):305–13.

- Dantas TBV, Moura IMR, da Costa RP, de Souza GE, Severino RP, Consolaro HN, et al. Tandem Mass Spectrometry and Bio-Guided Isolation of Secondary Metabolites With Antiplasmodial Activity From Dalbergia miscolobium Bark. Chem Biodivers. 2025 Sep 8. [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro G de JG, Rei Yan SL, Palmisano G, Wrenger C. Plant Extracts as a Source of Natural Products with Potential Antimalarial Effects: An Update from 2018 to 2022. Pharmaceutics. 2023 Jun 1;15(6):1638.

- Metsämuuronen S, Sirén H. Bioactive phenolic compounds, metabolism and properties: a review on valuable chemical compounds in Scots pine and Norway spruce. Phytochemistry Reviews. 2019 Jun 22;18(3):623–64.

- Herniter IA, Lo R, Muñoz-Amatriaín M, Lo S, Guo YN, Huynh BL, et al. Seed Coat Pattern QTL and Development in Cowpea (Vigna unguiculata [L.] Walp.). Front Plant Sci. 2019 Oct 25;10.

- Ali O, Ramsubhag A, Jayaraman J. Biostimulant Properties of Seaweed Extracts in Plants: Implications towards Sustainable Crop Production. Plants. 2021 Mar 12;10(3):531. [CrossRef]

- Api AM, Belsito D, Biserta S, Botelho D, Bruze M, Burton GA, et al. RIFM fragrance ingredient safety assessment, spiro[bicyclo[4.1.0]heptane-2,5’-[1,3]dioxane], 2′,2′,3,7,7-pentamethyl-, (1α,3α,6α)-, CAS Registry number 121251-67-0. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 2021 Mar;149:111984.

- Chylinski C, Degnes KF, Aasen IM, Ptochos S, Blomstrand BM, Mahnert KC, et al. Condensed tannins, novel compounds and sources of variation determine the antiparasitic activity of Nordic conifer bark against gastrointestinal nematodes. Sci Rep. 2023 Aug 18;13(1):13498. [CrossRef]

- Tienaho J, Liimatainen J, Myllymäki L, Kaipanen K, Tagliavento L, Ruuttunen K, et al. Pilot scale hydrodynamic cavitation and hot-water extraction of Norway spruce bark yield antimicrobial and polyphenol-rich fractions. Sep Purif Technol. 2025 Jul;360:130925.

- Alves UV, Jardim e Silva E, dos Santos JG, Santos LO, Lanna E, de Souza Pinto AC, et al. Potent and selective antiplasmodial activity of marine sponges from Bahia state, Brazil. Int J Parasitol Drugs Drug Resist. 2021 Dec;17:80–3. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).