Submitted:

17 December 2025

Posted:

18 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

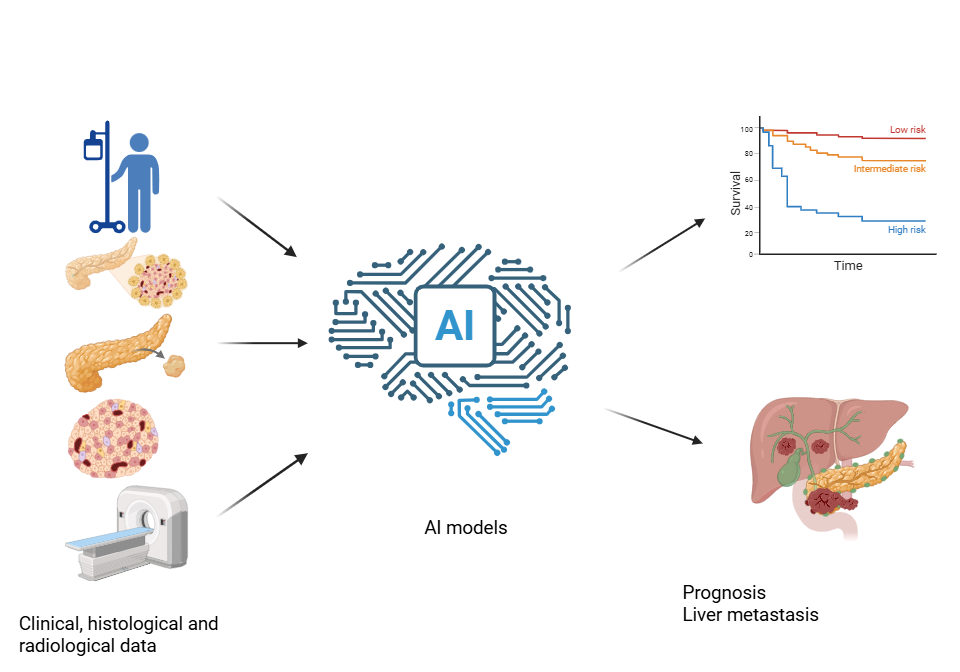

2. AI-Driven Prognostic Models for Pan-NENs

2.1. Prediction of Overall Survival

| Study | Study Population | Objective | AI Model | Variables included in the analysis | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bi 2025 [19] | SEER-based, 7,463 Pan-NETs | Prediction of liver metastases | Combination of LASSO and Boruta, 10 ML algorithms |

Age, gender, race, marital status, social status, TNM, size, functional status, primary site, grade, metastatic pattern, surgery | - Best performance GBM - AUC: 0.91 |

| Greenberg 2024 [22] |

Multicenter, 95 Pan-NETs | Prediction of metastatic recurrence | ML applied to define a transcriptomic-based gene panel | Genes: SV2, chromogranin A and B, (TPH1), ARX, PDX1, UCHL1, novel 8-gene panel (AURKA, CDCA8, CPB2, MYT1L, NDC80, PAPPA2, SFMBT1, ZPLD1) | AUC: 0.88 |

| Hillman 2025 [16] | SEER-based, 3,225 Pan-NENs | Prediction of OS | EACCD | AJCC TNM system, age | C-index: 0.70 |

| Huang 2021 [21] |

Single-center, 72 Pan-NENs | Prediction of 3-yr RFS | Semiautomatic segmentation DL method applid to CEUS: Fine-tuned SE-ResNeXt-50 CNN + multivariate logistic nomogram | CEUS images, arterial enhancement level, tumor size | AUC: 0.70 – 0.78 |

| Ji 2025 [23] | Single-center, 108 Pan-NETs + 51 external validation cohort | Prediction of OS | Reproducible Prognosis Molecular Signature platform (ML-based model) |

Proteogenomic data, data about disease recurrence | - Identified three-protein prognostic signature (GNAO1, INA, VCAN) |

| Jiang 2023 [13] |

SEER-based, 3,239 Pan-NENs | Prediction of 5- and 10-yr OS | DeepSurv neural network vs. NMTLR, Random Survival Forest, Cox model | Age, gender, race, marital status, primary site, grade, tumor size, tumor extension, treatment | - Best performance by DeepSurv - AUC: 0.87 (5-yr) 0.90 (10-yr) - Web calculator provided |

| Li 2023 [12] |

SEER-based, 1,998 Pan-NETs + 245 Chinese cases |

Prediction of OS | LASSO + Random-Forest feature selection → logistic & Cox nomogram models | Diagnostic model: grade, N-stage, surgery, chemotherapy, tumor size, bone metastasis Prognostic model: subtype, grade, surgery, age, brain metastases |

- Nomogram outperforms TNM staging system - AUC: 0.88 - 0.89 - C-index: 0.76 |

| Ma 2024 [18] |

Single-center, 163 Pan-NETs | Prediction of RFS | Integrated nomogram (Pathomics logistic score + ResNet-based DLR + nerve infiltration) | Gender, age, tumor site in the pancreas, vascular/nerve infiltration, stage, ATRX/DAXX, Ki-67 hotspot index, MH index, DLR score | - AUC: 0.96 – 0.98 - C-index: 0.96 |

| Murakami 2023 [17] |

Multicenter, 371 Pan-NETs G1/G2 | Prediction of RFS | Random Survival Forest vs. Cox model | Ki-67, WHO grade, tumor size, residual tumor status, lymph node metastases | - Best performance by Random Survival Forest - AUC: 0.73 – 0.83 - C-index: 0.84 |

| Singh 2025 [15] |

Single-center, 447 Pan-NETs after PRRT | Prediction of OS | Random Survival Forest, Cox model | Age, gender, , grade, Karnofsky performance score, weight loss, tumor functionality, time from diagnosis to first PRRT, hepatomegaly, Hedinger syndrome, metastatic pattern, lab values, [18F]FDG-PET/CT positivity |

- C-index: 0.82-0.86 |

| Song 2021 [20] |

Multicenter, 74 Pan-NENs | Prediction of 5-yr RFS | U-Net segmentation + DL radiomics (SE-ResNeXt-50) + SVM | Age, neuroendocrine symptoms, arterial-phase DLR features | AUC: 0.77 – 0.83 |

| Yu 2025 [14] | SEER-based, 1,430 metastatic Pan-NETs | Prediction of OS | Seven ML–based prognostic models | Age, gender, primary site, TNM, tumor grade, surgery, chemotherapy, | - Best performance: XGBoost algorithm - AUC: 0.74-0.78 |

2.2. Prediction of Recurrence-Free Survival and Progression-Free Survival

3. Comments and Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Pan- | Pancreatic |

| NEN | Neuroendocrine Neoplasm |

| NET | Neuroendocrine Tumor |

| SSTR | Somatostatin Receptor |

| SSA | Somatostatin Analog |

| PRRT | Peptide Receptor Radionuclide Therapy |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| SEER | Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results |

| LASSO | Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator |

| C-index | Concordance Index |

| OS | Overall Survival |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| RFS | Recurrence-Free Survival |

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| AJCC | American Joint Committee on Cancer |

| EACCD | Ensemble Algorithm for Clustering Cancer Data |

| CEUS | Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound |

| GBM | Gradient Boosting Machine |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| NMLTR | Neural Multi-Task Logistic Regression |

| DLR | Deep Learning-Radiomics |

| [18F]FDG-PET/CT | 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| XGBoost | eXtreme Gradient Boosting |

References

- Nordstrand, MA; Lea, D; Soreide, JA. Incidence of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms (GEP-NENs): An updated systematic review of population-based reports from 2010 to 2023. J Neuroendocrinol 2025, 37(4), e70001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merola, E; Pascher, A; Rinke, A; Bartsch, DK; Zerbi, A; Nappo, G; Carnaghi, C; Ciola, M; McNamara, MG; Zandee, W; et al. Radical Resection in Entero-Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors: Recurrence-Free Survival Rate and Definition of a Risk Score for Recurrence. Ann Surg Oncol. 2022, 29(9), 5568–5577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambrosini, V; Kunikowska, J; Baudin, E; Bodei, L; Bouvier, C; Capdevila, J; Cremonesi, M; de Herder, WW; Dromain, C; Falconi, M. : Consensus on molecular imaging and theranostics in neuroendocrine neoplasms. Eur J Cancer 2021, 146, 56–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santo, G; di Santo, G; Cicone, F; Virgolini, I. Peptide receptor radionuclide therapy with somatostatin analogs beyond gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. J Neuroendocrinol 2025, 37(3), e70013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kos-Kudła, B; Castaño, JP; Denecke, T; Grande, E; Kjaer, A; Koumarianou, A; de Mestier, L; Partelli, S; Perren, A; Stättner, S; et al. European Neuroendocrine Tumour Society (ENETS) 2023 guidance paper for nonfunctioning pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours. J Neuroendocrinol 2023, 35(12), e13343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesselaar, MET; Partelli, S; Braat, AJAT; Croitoru, A; Soares Santos, AP; Schrader, J; Welin, S; Christ, E; Falconi, M; Bartsch, DK. Controversies in NEN: An ENETS position statement on the management of locally advanced neuroendocrine neoplasia of the small intestine and pancreas without distant metastases. J Neuroendocrinol 2025, e70083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 7; Zandee, WT; Merola, E; Poczkaj, K; de Mestier, L; Klumpen, HJ; Geboes, K; de Herder, WW; Munir, A. Evaluation of multidisciplinary team decisions in neuroendocrine neoplasms: Impact of expert centres. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2022, 31(6), e13639. [Google Scholar]

- Rv, Lloyd; Ry, Osamura; Klöppel, G; Rosai, J. WHO Classification of Tumours of Endocrine Organs, 4th ed; IARC Press: Lyon, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Panzuto, F; Merola, E; Pavel, ME; Rinke, A; Kump, P; Partelli, S; Rinzivillo, M; Rodriguez-Laval, V; Pape, UF; Lipp, R. : Stage IV Gastro-Entero-Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Neoplasms: A Risk Score to Predict Clinical Outcome. Oncologist 2017, 22(4), 409–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merola, E; Fanciulli, G; Pes, GM; Dore, MP. Artificial intelligence in the diagnosis of gastro-entero-pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms: Potential benefits and current limitations. J Neuroendocrinol 2025, 37, e70087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merola, E; Fanciulli, G; Pes, GM; Dore, MP. Artificial Intelligence for Prognosis of Gastro-Entero-Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Neoplasms. Cancers (Basel) 2025, 17(12), 1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J; Huang, L; Liao, C; Liu, G; Tian, Y; Chen, S. Two machine learning-based nomogram to predict risk and prognostic factors for liver metastasis from pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: a multicenter study. BMC Cancer 2023, 23(1), 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C; Wang, K; Yan, L; Yao, H; Shi, H; Lin, R. Predicting the survival of patients with pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms using deep learning: A study based on Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database. Cancer Med 2023, 12(11), 12413–12424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z; Zheng, Y; Wang, K; Fang, Z; Huang, H; Gao, Z; Du, C; Zhang, C; Huang, D; Zhang, J; et al. A clinically applicable machine learning model for personalized survival prediction in metastatic pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Eur J Surg Oncol 2025, 51(9), 110222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A; Sanduleanu, S; Kulkarni, HR; Langbein, T; Lambin, P; Baum, RP. The PANEN nomogram: clinical decision support for patients with metastatic pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasm referred for peptide receptor radionuclide therapy. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2025, 16, 1514792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillman, J; Clark, Q; Rehm, L; Ahmed, AE; Chen, D. Using Machine Learning to Revise the AJCC Staging System for Neuroendocrine Tumors of the Pancreas. Cancers (Basel) 2025, 17(22), 3658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, M; Fujimori, N; Nakata, K; Nakamura, M; Hashimoto, S; Kurahara, H; Nishihara, K; Abe, T; Hashigo, S; Kugiyama, N. : Machine learning-based model for prediction and feature analysis of recurrence in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors G1/G2. J Gastroenterol 2023, 58(6), 586–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M; Gu, W; Liang, Y; Han, X; Zhang, M; Xu, M; Gao, H; Tang, W; Huang, D. A novel model for predicting postoperative liver metastasis in R0 resected pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: integrating computational pathology and deep learning-radiomics. J Transl Med 2024, 22(1), 768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bi, J; Yu, Y. Predicting liver metastasis in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors with an interpretable machine learning algorithm: a SEER-based study. Front Med (Lausanne) 2025, 12, 1533132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, C; Wang, M; Luo, Y; Chen, J; Peng, Z; Wang, Y; Zhang, H; Li, ZP; Shen, J; Huang, B. : Predicting the recurrence risk of pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms after radical resection using deep learning radiomics with preoperative computed tomography images. Ann Transl Med 2021, 9(10), 833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B; Lin, X; Shen, J; Chen, X; Chen, J; Li, ZP; Wang, M; Yuan, C; Diao, XF; Luo, Y. : Accurate and Feasible Deep Learning Based Semi-Automatic Segmentation in CT for Radiomics Analysis in Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Neoplasms. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform 2021, 25(9), 3498–3506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenberg, JA; Shah, Y; Ivanov, NA; Marshall, T; Kulm, S; Williams, J; Tran, C; Scognamiglio, T; Heymann, JJ; Lee-Saxton, YJ. : Developing a Predictive Model for Metastatic Potential in Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumor. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2024, 110(1), 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, S; Cao, L; Gao, J; Du, Y; Ye, Z; Lou, X; Liu, F; Zhang, Y; Xu, J; Shi, X; et al. Proteogenomic characterization of non-functional pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors unravels clinically relevant subgroups. Cancer Cell 2025, 43(4), 776–796.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harishbhai Tilala, M; Kumar Chenchala, P; Choppadandi, A; Kaur, J; Naguri, S; Saoji, R; Devaguptapu, B. Ethical Considerations in the Use of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Health Care: A Comprehensive Review. Cureus 2024, 16(6), e62443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smiley, A; Reategui-Rivera, CM; Villarreal-Zegarra, D; Escobar-Agreda, S; Finkelstein. J: Exploring Artificial Intelligence Biases in Predictive Models for Cancer Diagnosis. Cancers (Basel) 2025, 17(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, A; Alderman, JE; Palmer, J; Ganapathi, S; Laws, E; McCradden, MD; Oakden-Rayner, L; Pfohl, SR; Ghassemi, M; McKay, F; et al. The value of standards for health datasets in artificial intelligence-based applications. Nat Med 2023, 29(11), 2929–2938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, S; Sharifa, M; I Kh Almadhoun, MK; Khawar, MM, Sr.; Shaikh, U; Balabel, KM; Saleh, I; Manzoor, A; Mandal, AK; Ekomwereren, O; et al. The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Optimizing Diagnosis and Treatment Plans for Rare Genetic Disorders. Cureus 2023, 15(10), e46860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).