Contents

1. Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

2. Epidemiology and Risk Factors . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4

2.1 Tobacco and Other Risk Factors . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4

2.2 Lung Cancer in Never-Smokers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

3. Early Detection and Screening . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6

4. Diagnosis and Staging . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8

4.1 Diagnostic Workup . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8

4.2 Molecular Diagnostics . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9

4.3 Staging . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

5. Surgical Management . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11

6. Radiation Therapy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

7. Systemic Therapies: Chemotherapy and Targeted Therapy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16

7.1 Cytotoxic Chemotherapy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16

7.2 Molecular Targeted Therapies . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

8. Immunotherapy and Tumor Microenvironment . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21

8.1 Immune Checkpoint Inhibition in Advanced NSCLC . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21

9. Role of Artificial Intelligence in Lung Cancer . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 24

9.1 AI in Lung Cancer Screening and Early Detection . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 24

9.2 AI in Diagnostic Imaging and Pathology . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25

9.3 AI in Treatment Decision Support and Prognosis . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25

9.4 AI in Radiation and Surgical Planning . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26

9.5 AI for Drug Discovery and Research . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26

9.6 Challenges and Future Outlook . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26

10. Future Directions and Ongoing Research . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27

10.1 Advances in Prevention and Screening . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27

10.2 Molecular and Personalized Therapies . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28

10.3 Immunotherapy Innovations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29

10.4 Interdisciplinary and Global Efforts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 30

11. Conclusion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31

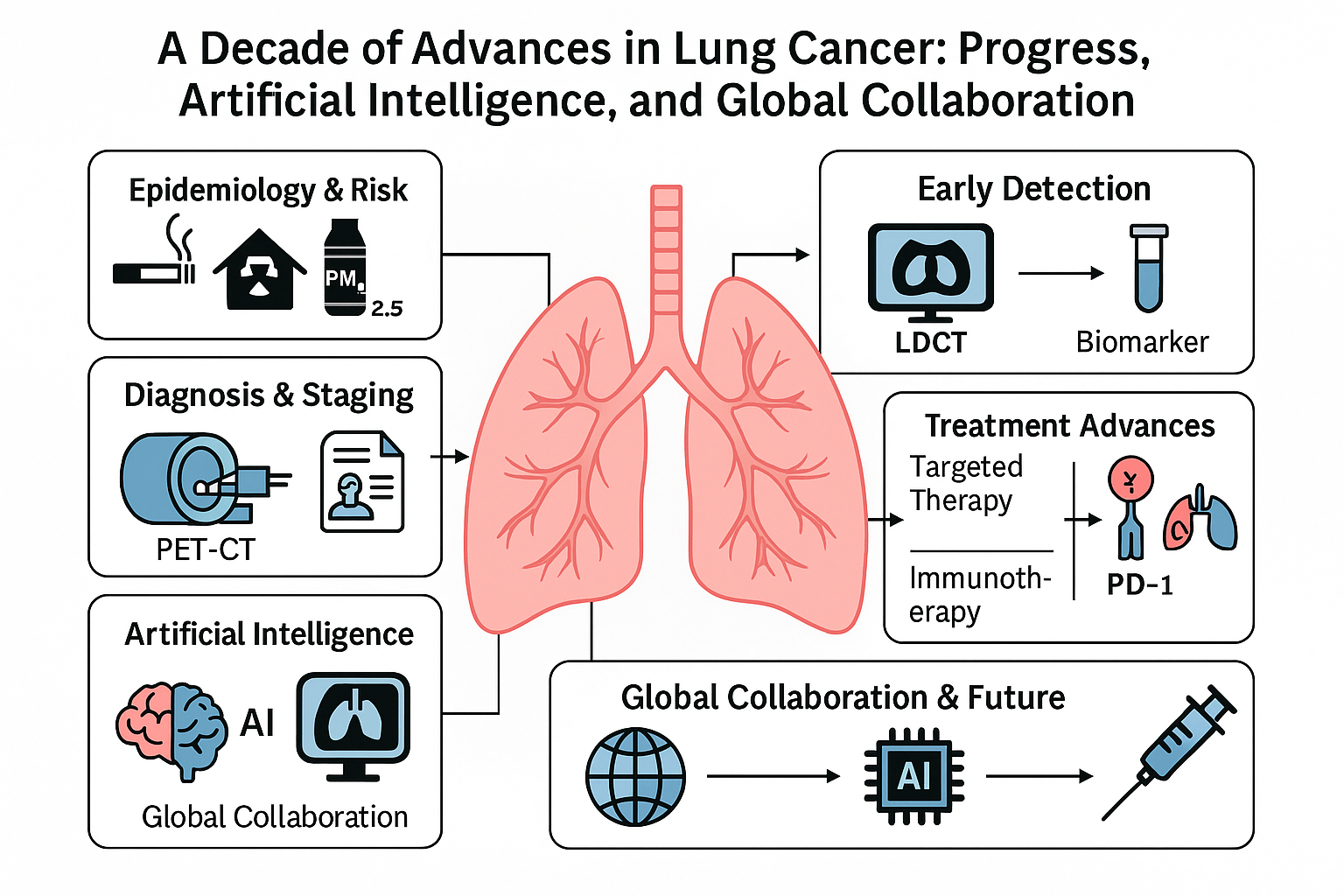

1. Introduction

Lung cancer remains the foremost cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide, accounting for an estimated 1.8 million deaths per year Lung cancer is broadly classified into two main types: non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and small cell lung cancer (SCLC). NSCLC accounts for about 85% of cases

Notably, around 10–20% of lung cancers worldwide occur in never-smokers (individuals who have smoked fewer than 100 cigarettes in their lifetime)[

7]. If considered separately, lung cancer in never-smokers would rank among the top ten causes of cancer mortality. Such tumors are more frequently adenocarcinomas and often display distinct molecular profiles (for instance, a higher prevalence of driver mutations like EGFR)[

7]. The etiology of lung cancer in never-smokers is an area of active research; identified factors include prolonged secondhand smoke exposure, indoor radon, environmental pollution (especially in regions with severe air quality issues), and possibly oncogenic viral infections or hormonal factors[

7,

8]. The high incidence of lung cancer in non-smokers, particularly in certain parts of Asia, underscores that lung carcinogenesis can arise via multiple pathways, not solely through tobacco-induced DNA damage.

One of the greatest challenges in lung cancer control has been the typically late stage at diagnosis. Early-stage lung cancer is often asymptomatic or causes only subtle symptoms (like mild cough), so it frequently goes undetected. As a result, the majority of patients historically presented with locally advanced or metastatic disease, where 5-year survival is under 10%. By contrast, when lung cancer is detected at Stage I (confined to lung), surgical resection can be curative and 5-year survival can exceed 60–70%

Fortunately, the past decade has brought tremendous progress. We have seen the advent of

low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) screening for lung cancer in high-risk individ- uals, which has been shown to significantly reduce mortality (

Section 3)[

11,

12]. On the therapeutic front, there has been a paradigm shift toward personalized medicine: a deeper understanding of lung tumor genomics led to the development of molecularly targeted ther- apies that have dramatically improved outcomes for patients with certain oncogenic driver mutations. In parallel, immunotherapy emerged as a game changer—immune checkpoint in- hibitors now form the backbone of treatment for many patients with advanced NSCLC, pro- ducing long-term remissions in a subset (

Section 8)[

21,

23,

24]. Throughout these advances, the importance of the tumor microenvironment (TME) and host immune response has be- come increasingly evident, guiding new research into combination therapies and biomarkers. Another exciting development is the integration of

artificial intelligence (AI) into lung cancer research and care. AI algorithms, particularly those based on deep learning, have demonstrated expert-level performance in tasks such as detecting lung nodules on imaging and analyzing pathology slides (

Section 9)[

69]. They are also being used to predict patient outcomes and optimize treatment strategies, heralding an era of data-driven clinical decision support. Although still in early phases of implementation, AI holds great promise in improving accuracy and efficiency across the lung cancer care continuum.

In this review, we will detail the key advances in lung cancer over approximately the last ten years and discuss how they are influencing clinical practice and patient outcomes. We begin with epidemiological trends and prevention efforts, then cover developments in early detection and diagnosis, followed by a deep look at modern treatment modalities (surgery, radiation, systemic therapies). We dedicate a section to the role of AI, reflecting its grow- ing impact. We also highlight contributions from major clinical trials and research groups worldwide—from large consortia like The Cancer Genome Atlas and TRACERx, to industry- sponsored trials and academic collaborations—underscoring the global nature of progress in this field. Finally, we discuss future directions, ongoing clinical trials, and emerging research that aim to further reduce the burden of lung cancer.

2. Epidemiology and Risk Factors

Lung cancer is the second most commonly diagnosed cancer and the leading cause of cancer death globally[

5,

6]. In 2020, it was estimated that there were 2.2 million new lung cancer cases worldwide (roughly 11% of all new cancers) and 1.8 million deaths (about 18% of all cancer deaths)[

6]. These sobering figures illustrate lung cancer’s outsized contribution to global cancer mortality. In many high-income countries, lung cancer incidence in men has been declining (paralleling reduced smoking rates), while in women it has plateaued or is still rising slightly as smoking became prevalent later among women[

4]. In low- and middle- income countries, smoking prevalence remains high or is increasing, portending a continued high lung cancer burden in coming decades. Overall, although age-adjusted lung cancer mortality has begun to inch downward in some regions, the absolute number of lung cancer deaths globally has risen – between 1990 and 2019, annual lung cancer deaths increased by approximately 0.97 million (a 91.8% rise) according to Global Burden of Disease analyses

2.1. Tobacco and Other Risk Factors

Cigarette smoking is by far the principal cause of lung cancer. Smokers have approximately 20-fold higher risk of developing lung cancer compared to never-smokers, and about 85% of lung cancers are attributable to smoking[

1,

4]. The risk increases with the duration of smoking and number of cigarettes per day (pack-years), and risk remains elevated even decades after cessation (though it does decrease over time after quitting). In former heavy smokers, lung cancer risk can remain several-fold above baseline even 15 years after cessation, which is why screening guidelines still include those who have quit within that time frame (

Section 3)[

11].

Beyond active smoking, secondhand smoke (involuntary smoking) is an established risk factor. Non-smokers who live with a smoker or have long-term occupational exposure to tobacco smoke have a higher incidence of lung cancer than those with no such exposure. Radon gas exposure is another key risk; radon is a radioactive gas released from soil that can accumulate in homes (particularly basements). Radon decay products emit alpha particles that can damage lung DNA. Radon is considered the second leading cause of lung cancer in never-smokers, and high residential radon levels correlate with increased lung cancer rates. Certain geographic areas with uranium-rich soils (for example, parts of Europe and the United States) have more radon-associated lung cancers, which has led to public health initiatives for radon testing and mitigation in homes.

Various occupational carcinogens contribute to lung cancer risk. Historically, as- bestos exposure (in mining, construction, shipbuilding, etc.) was a notorious cause of lung cancer (and mesothelioma); smokers with asbestos exposure have an especially high risk due to synergistic effects. Other occupational exposures linked to lung cancer include crystalline silica dust (e.g., in mining or sandblasting, causing silicosis that predisposes to cancer), heavy metals like arsenic, chromium and nickel, diesel exhaust, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocar- bons. Many countries have implemented industrial regulations to limit these exposures.

Air pollution has emerged as a significant environmental risk factor for lung cancer. Chronic exposure to fine particulate matter (PM2.5) and other pollutants from vehicle ex- haust, industrial emissions, and burning of coal/biomass has been associated with an in- creased lung cancer incidence, even at levels previously considered relatively safe. The WHO now classifies outdoor air pollution (and particulate matter specifically) as a Group 1 carcinogen. Notably, certain fast-developing countries with severe urban air pollution have seen rising lung cancer rates in non-smokers, implicating pollution as a contributor.

Pre-existing

lung diseases can also elevate lung cancer risk. Chronic obstructive pul- monary disease (COPD) and pulmonary fibrosis, for instance, carry a higher lung cancer risk even after adjusting for smoking history, suggesting that chronic inflammation and lung injury may predispose to malignancy[

84]. Individuals with a history of tuberculosis or other prior lung infections have scarred areas in the lung that can occasionally develop cancer (scar carcinomas).

Finally, there are genetic predispositions. While no highly penetrant single-gene mu- tations (like BRCA for breast cancer) are common in lung cancer, genome-wide association studies have identified certain susceptibility loci (e.g., in nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit genes) that slightly increase lung cancer risk, often by influencing smoking behavior or carcinogen metabolism. Rare familial syndromes, such as Li-Fraumeni syndrome (TP53 mutation) or EGFR mutation in never-smoking Asian female adenocarcinoma patients, ex- emplify cases where genetics play a more direct role, but these account for a very small fraction of lung cancers.

2.2. Lung Cancer in Never-Smokers

One of the intriguing aspects of lung cancer epidemiology is cancer in

never-smokers. Glob- ally, an estimated 15% of men and 50% of women with lung cancer are never-smokers (owing to lower smoking prevalence in women in many regions)[

4,

8]. If lung cancer in never-smokers were considered a separate entity, it would be the ∼7th most common cause of cancer death worldwide[

9]. Never-smoker lung cancers are more likely to be

adenocarcinomas (which tend to arise in the lung periphery). They often harbor specific mutations—for example, a large proportion of EGFR-mutant NSCLCs and ALK-rearranged NSCLCs are in never- smokers. The reasons why certain never-smokers get lung cancer are not fully elucidated, but as mentioned above, environmental exposures like secondhand smoke, radon, and air pollution are believed to play a role. Molecular profiling suggests that many never-smoker lung cancers have a different mutational signature (often lacking the widespread tobacco- related DNA damage), and some appear to arise from endogenous processes or as a result of susceptibility to smaller carcinogen doses Overall, the epidemiological trends and risk fac- tor insights reinforce two critical points: most lung cancers are preventable (by eliminating tobacco smoke exposure and other known carcinogens), and lung cancer is not a monolithic disease tied solely to smoking. This context sets the stage for why screening and early detection efforts (to catch cancer early, especially in high-risk smokers) are vital, and why a deeper biological understanding (to develop targeted interventions for various subgroups) is needed. In the next sections, we discuss how these efforts have materialized in the past decade.

3. Early Detection and Screening

Because lung cancer outcomes are so much better when the disease is caught early, consider- able effort has gone into developing effective screening methods. Until the 2000s, attempts at lung cancer screening (e.g., with chest X-rays and sputum cytology) had not shown a mortality benefit. This changed with the advent of low-dose helical computed tomography (LDCT) screening. The

National Lung Screening Trial (NLST) was a large randomized study conducted in the U.S. that compared annual LDCT versus annual chest radiographs in heavy smokers (aged 55–74, with ≥30 pack-year smoking history). The NLST results, published in 2011, demonstrated a 20% reduction in lung cancer-specific mortality in the LDCT arm[

11]. This was a groundbreaking finding: for the first time, a screening method was shown to save lives in lung cancer. LDCT screening could detect tumors at much smaller sizes (often

<2 cm) and earlier stages than they would have been without screening. Im- portantly, about 70% of screen-detected lung cancers in NLST were stage I, whereas in the radiography or unscreened cohorts, the majority were stage III or IV[

11].

Subsequent studies in Europe, such as the NELSON trial in Belgium and the Netherlands, confirmed these benefits. The NELSON trial (published 2020) found a 24% reduction in lung cancer mortality with LDCT screening compared to no screening, after 10 years of follow- up[

12]. Intriguingly, the mortality reduction in NELSON was even larger (up to 33%) in women, possibly because women in the trial tended to have slower-growing screen-detectable tumors that benefited more from early detection.

On the strength of this evidence, screening guidelines worldwide have been updated. In the United States, since 2013 the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) has recommended annual LDCT screening for high-risk individuals. The criteria were initially ages 55–80 with ≥30 pack-years and (if former smokers) having quit within the last 15 years. In 2021, the USPSTF broadened the eligibility (lowering the start age to 50 and pack-years to 20) to include more at-risk persons (especially women and African Americans, who on average smoke fewer cigarettes per day but still face high risk). Many other countries have initiated or are considering lung screening programs, often tailoring entry criteria to their populations. For instance, some European programs start at age 50 or 55 with similar smoking exposure requirements, while certain Asian guidelines consider risk models that incorporate factors like environmental exposures or chronic lung disease history (since never-smokers form a higher fraction of cases in Asia).

Lung cancer screening with LDCT, however, comes with challenges. One major issue is the high rate of

false positive findings. LDCT will detect any small nodule in the lungs, and lung nodules are very common (especially in older smokers) and usually benign (from old infections or inflammation). In the NLST, about 24% of participants had a positive screen result (requiring follow-up) at some point, but 96% of those positive screens turned out not to be cancer[

11]. Thus, the vast majority of nodules flagged by screening are false alarms. This can lead to unnecessary invasive procedures (biopsies or even surgeries) and significant anxiety for patients. Guidelines have since refined how to handle nodules based on size, growth, and appearance to reduce unnecessary interventions. For example, small nodules (

<6 mm) are generally just followed with another CT in 12 months, whereas larger or suspicious nodules are investigated sooner. Even so, in practice false positives remain a concern. A meta-analysis of LDCT screening studies found an aggregate false-positive rate of about 5–7% per round of screening

Overdiagnosis is another potential harm: this is the detection of a lung cancer that would never have caused clinical problems in the person’s lifetime (for example, an extremely slow-growing tumor in an elderly patient who might die of something else first). Overdiag- nosis leads to unnecessary treatment. Estimates of overdiagnosis in LDCT screening have varied, but a long-term NLST analysis suggested around 10–18% of screen-detected lung can- cers may be overdiagnosed[

10]. Ongoing follow-up and newer statistical models are refining these estimates.

Another challenge is

screening uptake. Those who stand to benefit the most from screening (long-term heavy smokers) often have lower rates of participation due to various factors like lack of access, knowledge gaps, or distrust. Studies found that current smokers and individuals of lower socioeconomic status were less likely to enroll in screening programs Despite these issues, lung cancer screening is gaining traction as a valuable tool. Importantly, screening is not a one-time event but an annual commitment (for as long as the person remains at risk, typically until age 80 or they have been quit

>15 years per guidelines). Many ongoing studies are exploring improved criteria for selecting who should be screened. Some use risk prediction models that include age, smoking intensity, and possibly genetic or biomarker factors to better stratify risk than the blunt pack-year criteria[

13]. Others are examining whether screening can be beneficial in groups like never-smokers with other risk exposures (though currently no guidelines recommend that).

Beyond CT scans, other methods of

early detection are under investigation. For exam- ple, analysis of sputum for molecular markers: a panel of microRNAs in sputum has shown high specificity (95%) and moderate sensitivity (72%) for detecting lung squamous-cell car- cinoma in high-risk individuals [

15]. While not accurate enough to be a standalone test, such an approach could complement CT screening by helping distinguish which nodules are likely malignant. Similarly, blood-based biomarkers are a hot area of research. Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) can be detected in the blood of patients with lung cancer; studies have demonstrated that ctDNA analysis can identify mutations associated with lung cancer with ∼85% sensitivity and 96% specificity in known cancer patients, but in early-stage dis- ease, only about 50% of stage I patients had detectable ctDNA [

14]. This indicates current ctDNA assays might miss too many early cases to be used alone for screening. However, as technologies improve (e.g., using targeted next-generation sequencing or combining multiple protein and DNA markers), there is optimism that a blood test could one day augment or even partly substitute imaging in lung cancer screening.

Another novel imaging approach is lung cancer screening with Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI). MRI traditionally has not been used for lung screening due to lower spatial resolution for lung tissue and susceptibility to motion artifacts from breathing. But recent developments in MRI sequences (like ultrashort echo time imaging) and the absence of ionizing radiation make MRI an attractive option. Early research suggests MRI can detect lung nodules ∼5 mm and larger with sensitivity approaching that of LDCT, and with fewer false positives in some cases (because MRI may better distinguish tumor tissue from benign abnormalities like fibrosis)

In summary, lung cancer screening using LDCT has now become a proven, guideline- endorsed intervention for high-risk individuals. It shifts the stage distribution toward earlier disease and has been shown to save lives[

11,

12]. The focus is now on optimizing screening protocols (minimizing false positives, determining the ideal frequency and duration of screen- ing) and expanding eligibility to maximize public health benefit. There is also a drive to find complementary methods (biomarkers, improved imaging) that could increase the sensitivity or specificity of early detection. In the next section, we will move from screening to the diagnostic process that follows when a suspicious lesion is identified, and how advances in diagnostics have improved accuracy and staging.

4. Diagnosis and Staging

Accurate diagnosis and staging of lung cancer are critical, as they directly inform treat- ment decisions. Once a pulmonary lesion is detected (either via screening or inciden- tally/symptomatically), the goal is to establish a pathological diagnosis and determine the extent of disease. In the past decade, improvements in imaging and minimally invasive tech- niques have enhanced our ability to do this promptly and safely, while molecular diagnostic advances have allowed precise tumor characterization from small biopsy samples.

4.1. Diagnostic Workup

The initial evaluation of a suspected lung cancer often involves imaging beyond the detection scan. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest (with contrast) is standard to charac- terize the nodule or mass (size, location, features like spiculation or cavitation) and to look for additional lesions or lymph node enlargement. If a malignant process is likely, further imaging such as fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) is usually performed for staging (to evaluate metabolic activity in the main lesion and screen for metastases). PET-CT is highly sensitive for cancer involvement in mediastinal lymph nodes and distant organs like adrenal glands or bone; a positive PET in a lung nodule or lymph node has a fairly high likelihood of malignancy, whereas a negative PET in a small nodule does not completely exclude cancer (some slow-growing tumors like certain adenocar- cinomas or carcinoid tumors are PET-negative). Nonetheless, PET-CT has become integral in staging workups, as it often spares a patient unnecessary surgery by revealing occult metastases.

To confirm a lung cancer diagnosis, a tissue biopsy is required (providing histology and increasingly molecular data). The choice of biopsy technique depends on the location of the lesion:

For central tumors or enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes,

bronchoscopy is typically the first approach. Modern flexible bronchoscopy can visualize tumors in the airways and allow forceps biopsies or brushings. Even if the main tumor is peripheral, bronchoscopy can sample lymph nodes via

endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration (EBUS-TBNA). EBUS uses an ultrasound probe at the bronchoscope tip to see beyond the airway walls. It has revolutionized mediastinal staging by enabling minimally invasive needle biopsy of mediastinal and hilar lymph nodes as small as 5–10 mm. The diagnostic yield of EBUS-TBNA for malignant nodes is around 85–90%, comparable to surgical mediastinoscopy [

93]. Current lung cancer guidelines recommend EBUS (and/or esophageal ultrasound, EUS) as the preferred first method to biopsy mediastinal nodes, due to its safety and accuracy

For peripheral or difficult-to-reach lesions, a transthoracic needle biopsy (TTNB) is often employed. Under CT or fluoroscopic guidance, an interventional radiologist inserts a fine needle through the chest wall into the nodule to aspirate cells or obtain a core tissue sample. TTNB has a high sensitivity (90%+) for malignancy in experienced hands, and can often provide a diagnosis for small, solitary pulmonary nodules that bronchoscopy cannot reach. The main risk of TTNB is pneumothorax (collapse of lung due to air entry through the needle tract), which occurs in about 15–25% of cases, though only a subset of those require chest tube placement. Risk of significant bleeding is low but present, especially if a vascular structure is inadvertently traversed.

If both bronchoscopy and TTNB are non-diagnostic and suspicion remains high, or if the patient is a surgical candidate, a diagnostic video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) biopsy or resection may be done. This is essentially proceeding to surgery to either wedge resect the nodule or perform a lobectomy, and have a pathologist examine it intraoperatively (with frozen section) to confirm malignancy. With the prevalence of minimally invasive techniques, the morbidity of such surgical diagnosis has decreased, but it is still typically a last resort due to being an invasive procedure. One scenario where upfront surgery is considered is a growing nodule in a patient highly likely to have lung cancer (say an enlarging 2 cm spiculated upper lobe nodule in a 65-year-old heavy smoker) where biopsies might be risky or have high false-negative rates—in such a case, it can be reasonable to go straight to definitive surgical resection, combining diagnosis and treatment.

Once a tissue diagnosis of lung cancer is obtained, pathologists differentiate the histo- logical type. Broadly, NSCLC versus SCLC is the crucial distinction (the latter is usually obvious from morphology: sheets of small blue cells with neuroendocrine features). Within NSCLC, the main subtypes are adenocarcinoma (by far the most common, especially in non-smokers), squamous cell carcinoma (more common in smokers, often centrally located), and large cell or other less common variants. Immunohistochemistry aids classification (e.g., TTF-1 positivity supports adenocarcinoma of lung origin, p40 positivity confirms squamous differentiation). Accurate subtyping is important because it influences treatment decisions (for instance, pemetrexed chemotherapy is effective in non-squamous NSCLC but not squa- mous NSCLC, and certain targeted drugs are only relevant to adenocarcinomas). In the last decade, the World Health Organization updated the lung tumor classification (2015) to incorporate new entities like adenocarcinoma in situ and to discontinue terms like “bronchi- oloalveolar carcinoma,” reflecting better understanding of early-stage adenocarcinomas.

4.2. Molecular Diagnostics

A defining feature of modern lung cancer diagnosis is the incorporation of

molecular test- ing. Given the explosion of targeted therapies for specific genetic alterations (discussed later), it is now standard of care to test lung adenocarcinoma (and other NSCLC, if non-squamous or in select cases) for a panel of driver mutations and gene fusions. Guidelines typically recommend at least testing for EGFR mutations, ALK and ROS1 fusions, BRAF mutations, MET exon 14 skipping mutations, RET fusions, and now KRAS G12C mutations, among others, in patients with advanced NSCLC[

93]. This is often done via next-generation sequencing (NGS) panels on the biopsy specimen. Even patients with earlier-stage NSCLC may undergo molecular testing, especially if adjuvant targeted therapy might be considered (e.g., EGFR mutation testing in a resected stage II NSCLC patient, given the recent ap- proval of osimertinib in that setting). In addition to mutations,

PD-L1 expression by immunohistochemistry is assessed in virtually all newly diagnosed advanced NSCLC cases, as it guides first-line immunotherapy use (

Section 8). PD-L1 is expressed on tumor and im- mune cells; a high PD-L1 Tumor Proportion Score (TPS) ≥ 50% identifies patients who can receive pembrolizumab monotherapy with excellent outcomes[

23], whereas low or negative PD-L1 often suggests using combination chemo-immunotherapy instead. Thus, PD-L1 IHC has become as routine as staining for TTF-1 in lung tumor pathology.

To ensure adequate material for all this testing, it’s crucial that biopsy specimens are handled properly. Small needle biopsies can yield limited tumor cells; pathologists and oncologists have had to coordinate so that, for example, tissue is triaged for molecular testing (sometimes doing a rapid on-site evaluation during EBUS to get extra passes for DNA extraction). If initial biopsy is insufficient for molecular analysis, a repeat biopsy or plasma ctDNA test may be done.

In cases of SCLC, or squamous NSCLC in heavy smokers, extensive molecular testing is less routinely pursued (because targeted therapies to date have mostly benefited adenocar- cinoma patients), but this is evolving: trials of immunotherapy and novel targets in SCLC mean that things like DLL3 expression or others might be tested in future. Already, all pa- tients with extensive-stage SCLC get testing for PD-L1 on tumor cells, not because it changes first-line treatment (immunotherapy is given regardless) but because it might influence later trial eligibility or prognosis.

4.3. Staging

Accurate staging of lung cancer is indispensable for choosing appropriate therapy. The TNM staging system is used, where T (tumor) describes the size and local extent of the primary tumor, N (nodes) denotes regional lymph node involvement, and M (metastasis) indicates spread to distant organs. The 8th edition of the TNM staging (implemented around 2017) refined some size cut-offs (e.g., <1 cm T1a, etc.) and reclassified certain metastasis patterns (like a single contralateral lung nodule is M1a). Essentially: - Stage I: tumor confined to lung, no nodes (subdivided by tumor size into IA, IB). - Stage II: involvement of hilar or intrapulmonary (N1) nodes, or a larger tumor with chest wall invasion, etc. - Stage III: involvement of mediastinal (N2 or N3) lymph nodes or more extensive local invasion (like into mediastinal structures). IIIA often indicates resectable disease with N2 nodes, IIIB and IIIC often unresectable due to contralateral nodes or extensive invasion. - Stage IV: distant metastases (including malignant pleural effusion) or tumor in contralateral lung lobe.

The staging workup at diagnosis typically includes: - CT or PET-CT of the chest and upper abdomen (to cover lungs, mediastinum, liver, adrenals). - MRI of the brain (or CT brain with contrast) for NSCLC stage II or higher (since about 10% of those have brain metastases). In SCLC, brain MRI is done even for limited stage due to high propensity. - Bone scan or PET for skeletal metastases (PET covers it). - Possibly additional imaging like abdominal ultrasound if PET not done.

Invasive staging is focused on the mediastinum as described: EBUS/EUS and/or me- diastinoscopy as needed to confirm nodal status. For example, if PET shows an N2 node uptake, EBUS biopsy is done to confirm malignancy histologically. If PET is negative in mediastinum but tumor is centrally located or >3 cm, guidelines often still recommend sampling mediastinal nodes (since PET can be falsely negative if nodes are small or tumor has low FDG uptake). EBUS has largely replaced surgical staging for routine evaluation, reserving mediastinoscopy for cases where EBUS is not available or results are inconclusive. Once all data are in, the patient is assigned a stage group (I–IV). Staging determines treatment: e.g., Stage I generally goes to surgery alone, Stage III might go to combined chemoradiation, Stage IV usually needs systemic therapy, etc. Staging also carries prognostic information: 5-year survival ranges from > 80% in the smallest Stage IA tumors to <5% in Stage IV.

One recent refinement in staging is the concept of oligometastatic disease (usually a few metastases, e.g., 1–3, in limited sites). This isn’t a separate TNM category, but there’s growing evidence that patients with a very limited metastatic burden (like a single brain or adrenal metastasis) may benefit from aggressive local therapies to all disease sites (surgery or SBRT), approaching a potentially curative intent in some cases. Thus, some Stage IV patients with oligometastases are managed with a different strategy than those with widespread metastases. Trials like SABR-COMET (though not lung-specific) and ongoing lung-specific trials are exploring this.

In summary, the diagnostic and staging process for lung cancer has advanced to become more accurate and less invasive. The combination of high-resolution imaging (PET-CT), endoscopic biopsy techniques (EBUS), and detailed pathological/molecular analysis allows clinicians to precisely classify the cancer type and extent before starting therapy. This is crucial because, as the next sections will discuss, treatment is now highly tailored to the individual patient’s disease characteristics. A decade ago, a patient might simply be labeled as having “NSCLC, Stage IIIA” and be offered a fairly uniform treatment. Today, that same patient’s workup would yield a plethora of information (e.g. adenocarcinoma vs squamous, EGFR wild-type, ALK-negative, high PD-L1, PET-negative N2 nodes confirmed by EBUS, etc.), and the treatment plan would be personalized accordingly (perhaps chemoradiation followed by immunotherapy if unresectable Stage III, or surgery followed by targeted therapy if resectable and a driver mutation is present, etc.). All of this hinges on accurate diagnosis and staging.

We will now delve into the treatment modalities themselves and how they have evolved, starting with surgery and radiotherapy, and then systemic medical therapies.

5. Surgical Management

Surgery offers the best chance of long-term survival or cure for patients with early-stage NSCLC. For localized tumors (generally Stage I and II, and select Stage IIIA), surgical resection of the tumor can be curative. Over the past decade, surgical management of lung cancer has seen significant advancements in two main areas: (1) adoption of minimally invasive techniques that reduce operative morbidity, and (2) refinements in the extent of resection, including the validation of sublobar resection for small tumors.

The traditional gold standard surgical procedure for NSCLC is an

anatomical lobec- tomy (removal of the lung lobe containing the tumor) with systematic mediastinal lymph node dissection. This was established by a pivotal trial in 1995 that showed lobectomy was superior to sublobar wedge resection for stage I cancers

<3 cm, in terms of local control and survival[

58]. However, that study pre-dated modern imaging and techniques. In the last several years, evidence has accumulated that for carefully selected patients with very small, peripheral lung cancers (particularly those ≤2 cm with ground-glass features or ra- diologic appearance of early adenocarcinoma), a

segmentectomy (removal of an anatomic segment of lung) or wedge resection can achieve outcomes equivalent to lobectomy. In 2022, results from two phase III trials (JCOG0802 in Japan and CALGB/Alliance 140503 in North America) were published, confirming that sublobar resection is non-inferior to lobectomy for peripheral NSCLC tumors up to 2 cm with no nodal involvement[

59,

60]. Five-year over- all survival in these trials was around 80–90% in both arms, and cancer recurrence rates were similar. These findings represent a paradigm shift—surgeons can now consider lung- sparing surgery for small tumors, which preserves more lung function while still providing a cure[

60]. Accordingly, guidelines are beginning to endorse segmentectomy for

<2 cm stage IA NSCLC, especially for tumors with favorable features (e.g., those that are ground-glass or

in situ/minimally invasive adenocarcinoma). The caveat is that an adequate margin (usually the entire anatomical segment containing the tumor) and thorough nodal evaluation are needed to achieve lobectomy-equivalent outcomes.

In terms of

technique, there has been widespread adoption of

minimally invasive tho- racic surgery. Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) and, more recently, robotic- assisted thoracic surgery (RATS) allow lung resections to be performed via small ports (typically 3–4 incisions of 1–3 cm) without the need for rib-spreading thoracotomy. Numer- ous studies and meta-analyses have shown that VATS lobectomy results in significantly less postoperative pain, shorter hospital stays, and fewer complications (like air leaks and atrial fibrillation) compared to open lobectomy, while achieving equivalent oncologic outcomes[

61]. As of 2020, over half of lobectomies in many centers are done via VATS/RATS. Minimally invasive approaches also facilitate sublobar resections and bilobectomies/pneumonectomies in experienced hands. Robotic systems have offered surgeons improved dexterity and vi- sualization, potentially increasing the adoption of minimally invasive lung surgery even for complex cases. The improved recovery from minimally invasive techniques means more pa- tients (especially elderly) can tolerate surgery, and also enables quicker transition to adjuvant therapy when indicated. For example, an older patient who might have avoided surgery due to fear of a difficult recovery might accept a VATS procedure. Enhanced recovery pathways (including better pain control, early ambulation, etc.) further complement these surgical advances

Mediastinal lymph node dissection or sampling is a crucial part of lung cancer surgery for accurate staging. In the modern era, even with PET/EBUS preopera- tively, unexpected nodal metastases (especially microscopic N1 or N2 disease) are found in a proportion of patients. NCCN and other guidelines recommend dissection of at least 3 mediastinal nodal stations during lung cancer surgery. This ensures correct staging and can improve local control. Some minimally invasive surgeons perform nodal dissection entirely via scopes; others exteriorize the lung after lobe removal to manually dissect nodes. Over- all, surgical staging accuracy has improved, and upstaging or detection of occult N2 disease post-surgery leads to patients getting appropriate adjuvant therapies.

While surgery is primarily for NSCLC, it has a limited role in SCLC, which is usually disseminated at diagnosis. Only in rare cases of very early SCLC (e.g. a solitary nodule with no nodes, found incidentally) is surgery performed, typically followed by chemotherapy.

An area of surgical innovation is the management of patients with limited metastases (oligometastatic disease). If a patient has, for example, a resectable lung tumor and a single brain metastasis, a combined modality approach can be considered: surgical resection of the lung tumor and either surgery or radiosurgery for the brain lesion. This approach has led to long-term survival in select cases and is being studied formally in trials. It blurs the line between Stage III and IV, and surgeons now sometimes collaborate with radiation oncologists to aggressively treat all disease sites in oligometastatic NSCLC, potentially offering a chance of remission where none existed before.

Another evolving concept is

neoadjuvant and adjuvant therapies in surgical patients. Traditionally, Stage I NSCLC was surgery alone, Stage II and III received surgery + adjuvant chemotherapy (which provides a 5% absolute survival benefit)[

47]. Over the last decade, tar- geted therapies and immunotherapies have entered the perioperative space. For instance, the ADAURA trial showed that giving the EGFR inhibitor osimertinib for 3 years after surgery in patients with EGFR-mutant stage IB–IIIA NSCLC reduced the risk of recurrence by ∼80% and markedly improved disease-free survival (the overall survival data are pending). This led to regulatory approval of adjuvant osimertinib, making it a new standard for EGFR-mutant lung cancers after resection. Likewise, adjuvant chemotherapy-immunotherapy combina- tions are being tested. On the neoadjuvant side, the CheckMate 816 trial demonstrated that adding nivolumab (anti–PD-1 immunotherapy) to chemotherapy before surgery signif- icantly increased the pathological complete response rate (to 24% vs 2% with chemo alone) and improved event-free survival in resectable stage IB–IIIA NSCLC[

34]. This regimen was approved by the FDA in 2022, meaning some patients now receive chemo-immunotherapy first, then surgery. From a surgeon’s perspective, these therapies can downstage tumors and potentially make an inoperable tumor operable (e.g., a bulky N2 node shrinks enough to allow resection). However, surgery after immunotherapy can sometimes be more challeng- ing due to fibrosis and immune effects. Multidisciplinary planning is essential to time and integrate these treatments. It is foreseeable that the majority of surgically managed lung cancer patients will also receive some form of systemic therapy (targeted or immunologic) either before or after surgery to eradicate micrometastatic disease and improve cure rates.

In summary, surgical management of lung cancer has become more patient-friendly and more nuanced in the last decade. Minimally invasive lobectomy is now routine, sublobar resections have gained acceptance for small cancers, and surgeons are part of a broader team delivering multi-modality therapy (with systemic treatments before or after surgery). These developments have expanded the pool of patients who can undergo curative-intent surgery (including older patients, those with borderline lung function, etc.) and have improved outcomes, with surgical patients now enjoying higher cure rates for early-stage disease than ever before.

6. Radiation Therapy

Radiation therapy is a cornerstone of lung cancer treatment, used in various settings ranging from curative therapy for early-stage disease (in patients who cannot have surgery) to part of combined-modality therapy in locally advanced disease, to palliation of symptoms in metastatic disease. Over the past ten years, radiation oncology for lung cancer has advanced significantly with respect to technology (allowing more precise and higher-dose treatments) and strategy (integrating with systemic therapies, expanding indications).

One of the most important advances has been the rise of stereotactic body radiother- apy (SBRT) for early-stage lung cancer. SBRT (also called SABR, stereotactic ablative radiotherapy) involves delivering a very high dose of radiation to the tumor in a small num- ber of fractions (often 3–5 sessions) with sub-millimeter precision, while sparing surrounding normal tissue. For medically inoperable patients with stage I NSCLC (for example, an elderly patient with severe COPD who cannot tolerate surgery), SBRT has become the standard of care and has demonstrated 3-year local control rates of 90–95%, which rival surgical outcomes. Multiple prospective studies (including the SPACE and CHISEL trials) have shown SBRT yields excellent tumor control with minimal toxicity for peripheral lung nodules up to ∼5 cm. Even in operable patients, randomized trials (RASLC, STARS, etc.) comparing SBRT vs surgery for small tumors suggested similar survival, though those trials struggled with enrollment. The technological improvements enabling SBRT include better tumor imaging (4D-CT scans that account for respiratory motion), refined treatment plan- ning systems, and image-guidance during delivery (on-board cone-beam CT to verify tumor position each session). As a result, radiation oncologists can now concentrate curative doses on just the tumor with sharp fall-off over a few millimeters, sparing most of the lung. SBRT is delivered non-invasively and is very well tolerated; the most common side effect is mild fatigue, with low rates of serious toxicity (e.g., <5% risk of chest wall pain or rib fracture for peripheral tumors, and a small risk of radiation pneumonitis or bronchial strictures for central tumors). The convenience of SBRT (completed in 1–2 weeks) versus surgery (hospi- tal stay, recovery time) has led some patients to choose SBRT even if surgery is an option. However, SBRT is generally reserved for patients who are not surgical candidates or who refuse surgery, as long-term follow-up beyond 5 years is still limited. Ongoing phase III trials (VALOR, StableMates) are comparing SBRT vs surgery in operable patients to better inform this choice. For now, SBRT has firmly established itself as a curative option for early NSCLC in non-surgical patients.

In locally advanced NSCLC (Stage III), radiation therapy has long been combined with chemotherapy for patients who are not surgical candidates (e.g., unresectable N2 or N3 disease). The standard approach is concurrent chemoradiation to the thorax, typically delivering around 60 Gy in 6 weeks with a platinum-based chemotherapy regimen. This ap- proach can achieve median survival around 28–30 months and 5-year survival on the order of 15–20%. Several advances in this domain are noteworthy. First, technological improvements such as intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) have allowed better sparing of organs at risk (like the esophagus, spinal cord, and healthy lung) compared to older 3D conformal techniques. IMRT and image-guidance have been shown to reduce rates of esophagitis and high-grade pneumonitis in Stage III treatment. Additionally, adaptive planning (adjusting the radiation plan mid-treatment based on tumor shrinkage) is being explored to further limit dose to normal tissues.

Perhaps the biggest recent change for Stage III NSCLC has been the introduction of consolidation immunotherapy after chemoradiation. The PACIFIC trial (2017) demon- strated that giving the PD-L1 inhibitor durvalumab for one year after definitive chemoradio- therapy significantly improved progression-free and overall survival for patients with unre- sectable Stage III NSCLC (3-year OS 57% with durvalumab vs 43% with placebo). This led to regulatory approval of durvalumab in this setting and a new standard of care: chemora- diation followed by immunotherapy for PD-L1 positive cases. This multimodal regimen has pushed 5-year survival for Stage III NSCLC above 40%, a substantial improvement

For limited-stage SCLC (confined to one hemithorax and regional nodes), radiation therapy combined with chemotherapy is the standard approach, as SCLC is typically too disseminated for surgery. The addition of thoracic radiation to chemo for LS-SCLC signif- icantly improves 3-year survival (20–30% vs <15% with chemo alone). Advances in SCLC radiation include exploring hyperfractionation (twice-daily radiation which was the origi- nal Turrisi regimen of 45 Gy in 1.5 Gy BID fractions) versus once-daily high dose (66 Gy in 33 fractions). Both are considered acceptable standard options now. Additionally, prophy- lactic cranial irradiation (PCI) has been a mainstay in SCLC to reduce brain metastases. In recent years, there’s been debate about PCI in the era of MRI surveillance; a Japanese trial suggested MRI monitoring might obviate PCI in some cases, but Western practice largely still favors PCI for fit patients with SCLC who respond to initial therapy.

Palliative radiotherapy remains vital in managing advanced lung cancer symptoms. Short courses of radiation (e.g., 30 Gy in 10 fractions or even 20 Gy in 5 fractions) are very effective at alleviating symptoms like hemoptysis, bronchial obstruction (causing dyspnea or post-obstructive pneumonia), bone pain from metastases, or brain metastasis symptoms. Improvements in radiotherapy planning have also benefited palliation; for instance, modern brain radiotherapy often employs stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) to treat a limited number of brain metastases with high precision, sparing patients the cognitive side effects of whole- brain radiotherapy.

Another notable concept is the abscopal effect, where radiation to a tumor lesion causes not only local tumor control but also regression of metastatic tumors outside the radiation field, presumably via immune activation. Historically rare, abscopal effects have been ob- served more frequently when radiation is combined with immunotherapies like checkpoint inhibitors

Technologically, beyond IMRT, the use of proton therapy for lung cancer has been investigated. Protons deposit most of their energy at a defined range (the Bragg peak), potentially sparing more normal tissue beyond the tumor compared to photons. For lung tumors near critical organs (like centrally located tumors where excess dose to heart and esophagus is a concern), proton therapy could reduce toxicity (e.g., lower risk of radiation pneumonitis or cardiotoxicity)

Another growing indication for radiotherapy is oligometastatic NSCLC. As men- tioned, evidence (e.g., the SABR-COMET trial and lung-specific studies like Gomez et al. 2019) indicates that for patients with a small number of metastatic lesions (like 1–5), ag- gressive local therapy to all sites (often using SBRT) plus systemic therapy can significantly prolong disease control and possibly survival. In NSCLC, randomized trials (Gomez, Iyen- gar) showed that consolidative SBRT after first-line chemo improved progression-free survival by many months. This has led to more routine use of SBRT for metastases in lung cancer management. For example, a patient with 3 metastases might receive systemic therapy and SBRT to all visible sites, aiming for a durable remission.

In terms of radiation planning and delivery, there have been continuous improve- ments: better motion management (e.g., respiratory gating or tracking tumor motion in real-time), use of adaptive radiotherapy where the plan is recalculated based on interval changes (particularly useful if a tumor shrinks significantly mid-treatment, allowing dose redistribution), and integration of functional imaging (using PET or MRI to guide dose painting to more active tumor subregions). These all contribute to more personalized and precise radiation therapy.

Finally, one cannot overstate the importance of multidisciplinary care in thoracic oncology. The best outcomes are achieved when surgeons, radiation oncologists, medical oncologists, pulmonologists, etc., collaborate from the time of diagnosis. For instance, bor- derline Stage III cases are discussed in tumor board to determine if trimodality therapy (chemoradiation then surgery) is feasible, or whether definitive chemoradiation is better. The addition of immunotherapy has required coordination (e.g., ensuring patients start dur- valumab within 6 weeks of radiation as per PACIFIC trial protocol). As radiation courses become shorter (with SBRT, for example), timing with systemic therapy requires planning (some sequence chemo after SBRT for select early-stage high-risk patients).

In summary, radiotherapy for lung cancer has become more effective and more integrated with other treatments. For early-stage disease, SBRT offers a non-surgical curative option with minimal morbidity. For locally advanced disease, modern chemoradiation techniques, combined now with immunotherapy, have significantly improved survival. Radiation oncol- ogists can deliver higher, more ablative doses to tumors with better sparing of normal tissue than a decade ago, improving both outcomes and quality of life for patients. As we move forward, ongoing trials and technological innovations (like proton therapy and MRI-guided radiotherapy) will further refine the role of radiation in lung cancer, likely expanding its curative potential and synergy with evolving systemic therapies.

7. Systemic Therapies: Chemotherapy and Targeted Therapy

Systemic therapy for lung cancer encompasses traditional cytotoxic chemotherapy as well as newer molecularly targeted agents that inhibit specific oncogenic drivers. Over the past decade, the paradigm of treating lung cancer has shifted dramatically, especially for NSCLC. While platinum-based chemotherapy was once the only option for advanced disease, we now have an array of targeted drugs that have transformed outcomes for molecularly-defined subgroups of patients. This section will review both chemotherapy developments and the explosion of targeted therapies.

7.1. Cytotoxic Chemotherapy

Platinum-doublet chemotherapy (typically cisplatin or carboplatin combined with a second drug such as paclitaxel, docetaxel, gemcitabine, vinorelbine, or pemetrexed) has been the backbone of systemic treatment for advanced NSCLC for decades. In the 2000s, multiple trials established that various platinum-doublet regimens yield a median survival around 8– 10 months in advanced NSCLC, with 1-year survival of 30–40%[

82]. No single regimen was vastly superior, though pemetrexed was found to be particularly effective in non-squamous NSCLC and is now commonly used in adenocarcinoma patients[

83].

In the last ten years, chemotherapy per se has not seen revolutionary changes in lung cancer—rather, its role has been redefined by integration with targeted and immunotherapies (discussed later). However, some noteworthy points include: -

Maintenance chemother- apy: Trials such as JMEN and PARAMOUNT showed that continuing pemetrexed as main- tenance after first-line chemo (in non-squamous NSCLC) could prolong progression-free and even overall survival. Maintenance therapy (with pemetrexed or gemcitabine or erlotinib in different trials) became an accepted strategy for patients who tolerate initial chemo well. -

Anti-angiogenic therapy: The angiogenesis inhibitor bevacizumab (an antibody against VEGF) was approved in 2006 for non-squamous NSCLC in combination with carboplatin- paclitaxel, after it improved survival in a phase III trial[

49]. In the last decade, bevacizumab continued to be used in some first-line regimens for non-squamous NSCLC. Additionally, a second-line trial (REVEL) in 2014 showed adding

ramucirumab (an antibody to VEGFR- 2) to docetaxel modestly improved survival in advanced NSCLC after platinum failure[

50]. Ramucirumab was thus approved as a second-line option with docetaxel. While these agents offer incremental benefits, they also carry risks (bevacizumab can cause bleeding, which is why it’s contraindicated in squamous cell carcinoma due to pulmonary hemorrhage risk).

- Small cell lung cancer (SCLC): Chemotherapy (usually etoposide with cisplatin or carboplatin) remains the cornerstone for SCLC. There were few changes for decades. In second-line SCLC, topotecan (a topoisomerase inhibitor) is the standard, with limited effi- cacy. A noteworthy development was the approval of lurbinectedin in 2020 (accelerated approval in the US) for relapsed SCLC, based on a phase II trial showing a 35% response rate. Lurbinectedin is a novel marine-derived compound targeting oncogenic transcription. While its benefit over topotecan is still under confirmatory study, it provided a new option for a tough-to-treat setting. Another drug, nal-IRI (nanoliposomal irinotecan), is being tested in SCLC second-line as well.

The challenges with cytotoxic chemotherapy are the well-known toxicities (myelosup- pression, neuropathy, nausea, etc.) and the fact that responses are often not durable due to chemo-resistant cancer cell clones. The 2010s didn’t bring new cytotoxic drugs that dramatically changed NSCLC outcomes, but the existing drugs found new utility in com- bination with immunotherapy and in the peri-operative setting: - In

adjuvant therapy after surgery, the benefit of chemotherapy (cisplatin-based) was reaffirmed (5% absolute OS improvement in meta-analyses for stages II–III)[

47]. The decade saw better patient selection for adjuvant chemo (e.g., avoiding it in stage IA or low-risk IB where it may not help, fo- cusing on higher risk patients). - In

neoadjuvant therapy (before surgery), multiple trials have shown platinum-doublets can downstage disease and perhaps improve surgical outcomes in stage III; however, the absolute survival benefit of neoadjuvant chemo alone is modest (around 5% at 5 years, similar to adjuvant). As we will discuss, adding immunotherapy to neoadjuvant chemo has produced more striking results recently[

34].

Chemotherapy has also been combined with other modalities: -

Chemoradiation: As covered, chemo acts as a radiosensitizer in concurrent therapy for stage III NSCLC and limited SCLC. The optimal chemo regimen for NSCLC chemoradiation was an area of study (e.g., PACIFIC trial used cisplatin-etoposide or carboplatin-paclitaxel), but no huge differ- ences emerged between regimens aside from toxicity profiles. -

Combination with tar- geted therapy: Generally, targeted therapy and chemo were not given concurrently for driver-positive NSCLC (targeted therapy alone was superior). But one interesting approach is combining EGFR TKIs with chemo. A Japanese trial (NEJ009) showed that erlotinib + chemo was better than erlotinib alone for EGFR-mutant NSCLC[

46]. This combination is not widely adopted yet but suggests chemo still has a role even in oncogene-driven cancers to prevent resistance. -

Combination with immunotherapy: Perhaps the biggest shift was the realization that adding platinum-doublet chemotherapy to immunotherapy could im- prove outcomes in metastatic NSCLC. The landmark KEYNOTE-189 trial (2018) found that pembrolizumab (PD-1 inhibitor) + platinum-pemetrexed gave a median OS of 22 months vs 10 months with chemo alone in first-line non-squamous NSCLC[

24]. This established chemo- immunotherapy as a new standard (discussed in next section). For squamous histology, KEYNOTE-407 showed pembrolizumab + carboplatin-taxane similarly improved OS[

25]. In these regimens, chemotherapy likely helps reduce tumor bulk and potentially modulates the immune environment to allow immunotherapy to work better, while immunotherapy then maintains response after chemo is finished. This synergy has revived the use of chemotherapy in the immunotherapy era as part of combination regimens.

In summary, conventional chemotherapy remains an important part of lung cancer treat- ment but is no longer the sole major systemic tool. Its incremental advances (maintenance, optimized scheduling) have improved convenience and slightly outcomes, but the real gains for patients have come from targeted therapies and immunotherapies. That said, chemo still provides significant benefit in patients without targetable mutations or as an adjunct to newer therapies. Additionally, nearly all patients with advanced lung cancer who receive immunotherapy will also receive chemotherapy either concurrently or at progression, so it remains a cornerstone that underpins the modern lung cancer therapeutic landscape.

7.2. Molecular Targeted Therapies

The past decade has witnessed an explosion in the development of targeted therapies for lung cancer, completely changing the treatment paradigm for patients whose tumors harbor certain driver mutations. Targeted therapies are drugs (often oral small molecules) designed to specifically inhibit the oncogenic proteins that drive tumor growth, thereby inducing dramatic responses with less toxicity than general chemotherapy. Lung cancer has been at the forefront of precision oncology, with multiple genomic alterations identified that are effectively druggable.

The prototypical example is

EGFR mutation-positive NSCLC. Sensitizing mutations in the EGFR gene (such as exon 19 deletions or L858R point mutation in exon 21) occur in roughly 10–15% of NSCLC in Western patients (and up to 40% in Asian, never-smoking patients). Tumors with these mutations are highly responsive to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs). The first-generation TKIs (erlotinib, gefitinib) and second-generation (afatinib, dacomitinib) showed improved response rates (60–70%) and progression-free sur- vival (PFS) compared to chemotherapy in this population[

44]. The median PFS on first-gen TKIs was around 10–12 months versus 5–6 months on chemo. However, resistance eventually develops, most commonly via a secondary EGFR mutation T790M in about 50–60% cases. This led to the development of

third-generation EGFR TKIs (namely osimertinib) that selectively target both EGFR sensitizing and T790M resistance mutations while spar- ing wild-type EGFR (resulting in fewer side effects). Osimertinib was initially approved for T790M-positive resistance[

55], but then the FLAURA trial (2018) demonstrated that os- imertinib as

first-line therapy for EGFR-mutant NSCLC significantly prolonged PFS (18.9 vs 10.2 months for standard EGFR-TKI) and improved 3-year overall survival 54% vs 44%. Osimertinib also has excellent CNS penetration, reducing brain metastasis risk. Thus, os- imertinib became the standard first-line therapy for EGFR-mutant lung cancer worldwide. It represents how targeted therapy can markedly improve outcomes—many patients on os- imertinib live several years with stage IV disease, and some achieve near-normal life during that time. Furthermore, as mentioned, osimertinib has proven beneficial in early-stage dis- ease after surgery (ADAURA trial), raising the possibility of actually curing more patients by eradicating micrometastases.

Another success story is

ALK-rearranged NSCLC, found in about 5% of lung adenocar- cinomas (especially never-smokers, younger patients). The first ALK inhibitor, crizotinib, showed high response rates ( 60%) and improved PFS vs chemo (PROFILE 1014 trial)[

56]. However, next-generation ALK inhibitors have since taken center stage: drugs like alec- tinib, brigatinib, ceritinib, and lorlatinib were developed to overcome resistance mutations and better penetrate the CNS. The ALEX trial (2017) established

alectinib as superior to crizotinib in first line, with median PFS around 34 months vs 10 months and much better 2-year PFS (62% vs 14%)[

57]. This was a remarkable improvement—many ALK+ patients now have durable disease control for 3+ years on alectinib before needing a change. Lor- latinib (a third-gen ALK inhibitor) can then be used post-alectinib and is effective against most known resistance mutations. The median survival of ALK-positive patients in the current era likely exceeds 5 years, which is a tremendous accomplishment compared to the∼1 year median survival in the pre-crizotinib era[

45]. It’s also notable that many ALK+ patients are young, never-smokers who now can hope to have a chronic disease managed over many years, often while maintaining good quality of life.

Beyond EGFR and ALK, multiple other targets have been identified: -

ROS1 rearrange- ments (1–2% of NSCLC): These are akin to ALK (the ROS1 protein is similar to ALK). Crizotinib is also active against ROS1 and was approved with response rates 70%. Next-gen ROS1 inhibitors like entrectinib have CNS activity and are approved first-line as well. Lorla- tinib has ROS1 activity too. -

BRAF mutations (about 2–4% of NSCLC, especially V600E): BRAF V600E is targetable by combined BRAF/MEK inhibition (dabrafenib + trametinib), which yields 60% response rates[

38]. This combo is an option after chemo in patients with BRAF-mutant lung cancer. -

MET exon 14 skipping mutations (3–4% of NSCLC, often older patients): This alteration leads to increased MET signaling. In 2020, two MET in- hibitors, capmatinib and tepotinib, were approved based on trials showing 40–50% response rates and median PFS ∼8 months in METex14-mutant lung cancer[

39]. These drugs are now standard options for this subset. -

RET fusions (1–2%, often in non-smokers): Previ- ously, multi-kinase inhibitors like cabozantinib had some activity, but highly specific RET inhibitors selpercatinib and pralsetinib were developed and approved in 2020 after show- ing 60–70% response rates and durable responses in RET-fusion lung cancers[

40]. These have manageable toxicity and are now first-line choices for RET-driven cases. –

NTRK fusions (

<1% of lung cancers, but actionable): TRK inhibitors larotrectinib and entrectinib have dramatic efficacy across TRK fusion-positive cancers (including lung), with response rates

>70%[

41]. Though very rare in lung, when present they can be treated with these agents (the so-called ”tumor-agnostic” approvals). -

KRAS: Historically ”undruggable”, but KRAS mutations are the most common driver in NSCLC (20–25% cases, particularly in smokers). In 2021, a breakthrough came with

sotorasib, which targets the KRASG12C mu- tation (present in ∼13% of NSCLC). Sotorasib showed a response rate of 37% and median PFS 6.8 months in heavily pretreated KRASG12C patients[

42], leading to approval as the first KRAS inhibitor. A similar drug adagrasib also gained approval. While these results are modest compared to EGFR/ALK drugs, they represent a crucial proof-of-concept that KRAS can be targeted. Combinations (like adding SHP2 inhibitors or EGFR inhibitors) are being explored to improve efficacy, as are inhibitors for other KRAS mutants (like G12D). This is a rapidly evolving area, and ongoing trials may soon bring KRAS inhibitors into earlier lines or in combinations that extend benefit. -

Others on the horizon: There are emerging targets like HER2 (2% of NSCLC have HER2 mutations; antibodies-drug conju- gates like trastuzumab-deruxtecan show promise),

Nrg1 fusions (rare, trial of afatinib or new NRG1-fusion targeted agents ongoing), etc.

Overall, in 2025 the landscape of metastatic NSCLC is such that

every patient’s tumor is tested for a panel of at least 8–10 driver genes. Roughly 50% of non-squamous NSCLC pa- tients have an identifiable driver that can be treated with an approved targeted therapy[

36]. For example, in one dataset: EGFR ( 15%), KRAS G12C ( 13%), ALK ( 5%), ROS1 (2%), BRAF (3%), METex14 (3%), RET (1–2%), NTRK (

<1%). If one includes emerging targets (HER2 2–3%, others), the fraction with “actionable” aberrations is slightly over half. This has translated into significantly improved outcomes. To illustrate: a patient with metastatic EGFR-mutant NSCLC treated with osimertinib now has a median survival of 3+ years (some live

>5 years), whereas a decade ago on chemo it would have been 1 year[

37]. Similarly, ALK+ patients on sequential alectinib then lorlatinib often survive

>5 years[

35]. The chal- lenge remains that eventually resistance develops even to targeted therapy. Research into

mechanisms of resistance has been intense, and it turns out tumors often evolve new mutations (e.g., EGFR C797S after osimertinib, ALK G1202R after alectinib) or alternate pathway activation (MET amplification in EGFR, etc.). This has led to next-next-generation inhibitors and combination trials. For EGFR C797S, novel fourth-gen EGFR TKIs are in trials. For ALK, lorlatinib handles most known resistances, but some compound mutations are arising that future drugs might tackle. In many cases, when targeted therapy resistance occurs, a tissue re-biopsy or liquid biopsy is done to see

how the tumor changed, and therapy is tailored accordingly (e.g., if an EGFR patient gets MET amplification, one might add a MET inhibitor). This personalized approach is an ideal, and as more drugs become available for various bypass mechanisms, it might become routine.

Another trend is moving targeted therapies into early stage disease. The ADAURA trial as mentioned showed disease-free survival benefit with adjuvant osimertinib. Trials are ongoing for adjuvant ALK inhibitors (ALINA: alectinib vs chemo in resected ALK+ NSCLC) and others. Neoadjuvant targeted therapy is being tested too (e.g., neoadjuvant osimertinib). The aim is to improve cure rates by eradicating micro-metastatic disease early. The results are awaited, but ADAURA’s success hints this could be practice-changing in the curative setting as well.

Targeted therapies generally have a different side effect profile than chemo: rash, di- arrhea, and liver enzyme elevations are common with TKIs; some have unique ones like VEGFR inhibitors causing hypertension or ALK inhibitors causing bradycardia and visual disturbances. Importantly, targeted drugs typically cause less severe cytopenias or nausea than chemo, so patients often feel better on them. However, they are not without issues (some, like early crizotinib, could cause vision issues, or third-gen ALK lorlatinib can cause cognitive/mood effects, etc.). Overall though, quality of life on targeted therapy tends to be better than on cytotoxic chemo for most.

In conclusion, targeted therapies have redefined what a diagnosis of metastatic lung can- cer means, turning certain subsets into chronic diseases with multi-year disease control. The necessity now is ensuring molecular testing is done for every eligible patient; unfortu- nately, studies show not all patients in the real-world get comprehensive testing (due to tissue limits, test availability, cost). Efforts by professional societies and advocacy groups push for broader NGS testing coverage and fast turnaround so that no patient misses the opportunity for a targeted drug if one is indicated.

As of 2025, the list of targets will likely continue to expand (e.g., newer KRAS inhibitors, more HER2 and others). The interplay of targeted therapy with other modalities is also of interest: combining targeted therapy with immunotherapy has generally been challenging (e.g., EGFR TKIs plus checkpoint inhibitors had high toxicity of pneumonitis in trials). So sequencing them is the norm (targeted therapy first, then immunotherapy at resistance if no other targets). Nonetheless, the integration of all these modalities is a current research frontier.

Having covered targeted therapies, we will next examine immunotherapy, which has been another pillar revolutionizing lung cancer outcomes, often complementing or substituting for chemotherapy in patients without targetable mutations.

8. Immunotherapy and Tumor Microenvironment

Immunotherapy, particularly the use of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), has transformed the treatment landscape of lung cancer in the last decade. By unleashing the body’s own immune system to recognize and attack tumor cells, immunotherapy has achieved outcomes never before seen in metastatic lung cancer, including long-term remissions in a subset of patients that appear to be cured. This section will discuss the major developments in im- munotherapy for lung cancer and the growing understanding of the tumor microenvironment (TME) that influences immune responses.

Immune Checkpoint Inhibition in Advanced NSCLC

Lung cancer was one of the first solid tumors to show dramatic benefits from immune check- point blockade. The two main checkpoints targeted have been PD-1/PD-L1 and CTLA-4:

PD-1 is an inhibitory receptor on T-cells that, when engaged by its ligand PD-L1 (on tumor or immune cells), dampens T-cell activity. Tumors often exploit this pathway by expressing PD-L1 to turn off anti-tumor T-cells. - CTLA-4 is another inhibitory receptor on T-cells (particularly during the priming phase in lymph nodes).

The first indication of efficacy came from the PD-1 inhibitors

nivolumab and

pem- brolizumab. In 2015, two landmark phase III trials (CheckMate-017 and -057) showed that in previously treated metastatic NSCLC, nivolumab significantly improved overall sur- vival compared to docetaxel chemotherapy[

21,

22]. These trials established immunotherapy as a new standard in the second-line setting. Response rates with nivolumab were about 20% vs 9% with chemo, and importantly responses were often durable; the 1-year survival nearly doubled (42% vs 24% in squamous NSCLC, for example)[

21]. Pembrolizumab sim- ilarly showed activity and was notable for requiring tumor PD-L1 expression as selection (the KEYNOTE-010 trial showed pembrolizumab improved survival vs docetaxel in PD-L1 positive NSCLC)[

20]. These successes led to widespread testing in the first-line setting.

The key breakthrough in first-line therapy was recognizing that in patients with high tumor PD-L1 expression, single-agent pembrolizumab could outperform chemotherapy. The KEYNOTE-024 trial (2016) demonstrated that for advanced NSCLC patients with PD-L1 TPS ≥50%, pembrolizumab alone yielded a response rate of 45% (vs 28% with chemo) and a median PFS of 10.3 vs 6.0 months, as well as improved overall survival

For patients without high PD-L1, trials investigated combining immunotherapy with chemotherapy. As mentioned in the chemotherapy section, KEYNOTE-189 (non-squamous) and KEYNOTE-407 (squamous) both showed that adding pembrolizumab to platinum- doublet chemotherapy substantially improved outcomes regardless of PD-L1 status

Another strategy was dual checkpoint blockade: combining PD-1 and CTLA-4 inhibitors. The CheckMate-227 trial (2019) had a complex design but importantly showed that nivolumab + ipilimumab (a CTLA-4 inhibitor) improved progression-free survival compared to chemo in a subset with high tumor mutation burden (TMB)

One remarkable feature of immunotherapy is the

tail of the survival curve. With chemo, almost all patients eventually succumb to disease, but with immunotherapy, a propor- tion (around 15–20%) achieve long-term remission. In 5-year follow-ups of the KEYNOTE- 024 trial, the 5-year OS was 32% with pembrolizumab vs 16% with chemo for PD-L1 high patients[

53]. Similarly, among those who responded to pembrolizumab, the majority re- mained in remission 5 years later. This suggests that a subset of lung cancer is essentially cured by immunotherapy, something unheard of with chemo. This “plateau” is reminiscent of metastatic melanoma where immunotherapy cures some patients. For lung, it’s a smaller fraction but real.

However, not all patients respond to immunotherapy. Primary resistance is common (e.g., PD-L1 negative tumors respond less, though some still do). And some respond then progress (acquired resistance). Research into biomarkers has expanded beyond PD-L1. Tumor mutational burden (TMB) was thought to predict benefit (more mutations might produce more neoantigens for T-cells to recognize). Trials gave mixed results on TMB; CheckMate-227 found high TMB patients benefitted from dual ICI even if PD-L1 low, but Keynote trials did not find TMB as predictive for pembrolizumab with chemo. TMB is not routinely used clinically (except in tumor-agnostic approval of pembrolizumab for TMB-high solid tumors, which is rarely applied to lung because we have other approvals).

The tumor microenvironment (TME) composition is increasingly recognized as crit- ical. Tumors with pre-existing TILs (tumor infiltrating lymphocytes), especially CD8+ T- cells, and an “inflamed” gene signature (interferon-gamma pathway etc.) tend to respond better

Another cause of resistance is tumor antigen loss or MHC downregulation, meaning T-cells no longer recognize tumor. Others include an immunosuppressive metabolic envi- ronment (like adenosine accumulation, which new drugs targeting CD73/adenosine pathway attempt to counter).

Immunotherapy has also extended to SCLC. SCLC often has high TMB (from tobacco), but initial trials of single-agent ICIs had modest results. The breakthrough was adding immunotherapy to first-line chemo in extensive-stage SCLC. The IMpower133 trial (2018) showed that adding atezolizumab to carboplatin-etoposide improved median OS from 10.3 to 12.3 months (and 2-year OS doubled from 10% to 22%)[

51]. Similarly, the CASPIAN trial (2019) found durvalumab with chemo improved OS (13.0 vs 10.3 mo)[

52]. These led to approval of atezolizumab or durvalumab + chemo as new standards for extensive SCLC. While these gains are more incremental than in NSCLC, they are the first improvement in SCLC first-line therapy in decades. In contrast to NSCLC, PD-L1 isn’t as clearly predictive in SCLC (many SCLCs have low PD-L1, but still benefit some). SCLC unfortunately lacks effective second-line immunotherapy (the Keynote-158 trial of pembrolizumab in relapsed SCLC saw only 19% response in PD-L1 positive, leading to an approval but many patients don’t respond and that indication was actually later withdrawn due to confirmatory trial failure).

Turning back to NSCLC, immunotherapy is now moving into early-stage disease as well. We’ve already discussed the PACIFIC trial where consolidation durvalumab after chemoradiation in Stage III unresectable NSCLC significantly improved long-term survival (with 5-year OS 43

All told, by 2025 immunotherapy is touching all stages of lung cancer: - In metastatic NSCLC, nearly all patients without targetable mutations will receive an ICI (either alone if PD-L1 high, or with chemo, or dual ICI). - In unresectable Stage III, consolidation immunotherapy after chemoradiation is standard. - In resectable Stage II–III, adjuvant immunotherapy after surgery and chemo is becoming a standard for PD-L1 positive disease.

In resectable Stage I–III, neoadjuvant chemoimmunotherapy is an emerging approach to improve surgical outcomes. - In Extensive SCLC, chemo + immunotherapy is standard first-line. - In Limited SCLC, trials are ongoing adding immunotherapy to concurrent chemoradiation (like adding atezo or durva; preliminary results have not yet shown a big improvement, but studies continue).

Despite these successes, many challenges remain. As mentioned, many patients do not respond to ICIs (especially those with ”cold” tumors). There is intense research into mak- ing immunotherapy effective for more patients. Strategies include: - Combining ICIs with other immunomodulatory agents: e.g.,

TIGIT inhibitors (like tiragolumab) combined with PD-L1 inhibitor; initial results (CITYSCAPE trial in PD-L1 high NSCLC) were promising, showing higher response and PFS[

80], but a larger trial didn’t meet the endpoint, casting uncertainty. Still, TIGIT is considered a viable target and trials continue. -

LAG-3 block- ers as noted are being tried. - Agents targeting

adenosine pathway (CD73, A2aR) to make TME less immunosuppressive. -

Cytokine therapies (like IL-2 variants) or