1. Introduction

The advent of the Space Race between the USA and the Soviet Union in the 1960s, saw the development of the world’s first human spaceflight programs. The earliest astronaut training programs involved selecting candidates from primarily military backgrounds, whose skill sets were suited to piloting vehicles and operating in high pressure environments. However, over time, government space agencies from six different sovereign nations have come to establish their own astronaut corps, and with them their own astronaut training programs.

Training has evolved over the decades, along with the requirements and technology employed to enable it. Astronauts are no longer selected purely from the military, and training is no longer focused on only one or two spacecraft types. Today, training requires astronauts to become familiar with a variety of spacecraft and space station modules, as well as developing their abilities to conduct complex scientific experiments, whilst working as part of multinational crews, on missions of ever-increasing time and complexity.

This paper aims to outline the earlier training approaches and resources that have been utilized by space agencies to date.

2. History of Astronaut Training

The first human in space was Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin, who launched as part of the Soviet Union's Vostok program on 12 April 1961 at the beginning of the Space Race. On 5 May 1961, Alan Shepard became the first American in space, as part of Project Mercury. Humans traveled to the Moon nine times between 1968 and 1972 as part of the United States' (U.S.) Apollo program and have had a continuous presence in space for over 25 years onboard the International Space Station (ISS). On 15 October 2003, the first Chinese taikonaut, Yang Liwei, traveled to space as part of the Shenzhou 5 mission, but as of 2025, humans have not traveled beyond Low Earth Orbit (LEO) since the Apollo 17 lunar mission in December 1972.

Currently, the United States, Russia, and China are the only countries with public or commercial human spaceflight-capable programs. However, non-governmental spaceflight companies have been working to develop human space programs of their own, for the purposes of space tourism, commercial astronaut transportation, in-space research and other business-related objectives. The first private human spaceflight launch was a suborbital flight conducted by the company Scaled Composites with SpaceShipOne on June 21, 2004. The first commercial orbital crew launch was conducted by SpaceX and took place in May 2020, transporting National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) astronauts to the ISS under a United States government contract.

Early astronaut selection was based on the ability to fulfill a variety of requirements necessary to successfully complete various space missions, along with the ability to portray the desired stereotype of an astronaut that the agencies required. The astronauts of the 1960s and 1970s were primarily military pilots who were chosen for their ability to function in high stress environments. These astronauts were competent ‘lone wolf’ types who were highly capable technical individuals and excellent pilots but not particularly known for their communication skills or ability to work well with others.

Training for these original astronauts focused on common academic classroom technical subjects, systems training in the spacecraft being flown, integrated emergency procedures, and crew related team building exercises. They also transferred their technical knowledge and training into the design of the vehicles they flew, enabling them to be considered not just as operators, but as integral participants in the development and testing of these new technologies and vehicles.

During the 1980s, NASA's strategic requirements for human spaceflight were dominated by the Space Shuttle program. Although plans for Space Station Freedom were discussed and approved in the 1980s, it was not until this project evolved into the International Space Station (ISS) program in the 1990s, that long duration human spaceflight strategic requirements were given a focus. After the retirement of the space shuttle program, the operation of the ISS saw many new complicated training requirements imposed, such as the requirement for Russian language proficiency.

Astronauts expected to spend time on the ISS are now required to be familiar not only with the U.S. equipment onboard the station but European, Japanese, and Russian station modules and equipment as well. They must also be knowledgeable about the Soyuz spacecraft, the U.S. commercial spacecraft (SpaceX Dragon) and the Russian Progress and Japanese HTV-X robotic resupply craft. They must be proficient in using space station software, conducting extravehicular activities, operating the space station’s robotic arm, along with numerous other tasks. Furthermore, astronauts are no longer trained for focused, limited duration missions with clearly defined skill sets as they were with the shuttle, but instead are required to have the knowledge and skills to live in space for a long duration of time, respond to unforeseen eventualities that may arise and fix them there rather than return to Earth, as well as conduct a large array of scientific experiments.

The U.S. astronaut program has evolved over the decades to meet the needs of the new activities initiated by NASA, and it has adapted to new social and political realities. The program has incorporated non-test pilots, such as scientists, along with diversifying its demographic base to include international participants, and other previously marginalized groups. Changes in training have been driven not only by the introduction of new spacecraft and requirements but by the need to accommodate astronauts whose experiences are different from that of test pilots.

3. Different Space Agency Astronaut Training Approaches

3.1. Space Agencies

Astronaut basic training, conducted by both NASA and Roscosmos, has advanced considerably since the early days in the 1960s. Today, astronauts are required to possess a greater array of abilities than ever before and are expected to perform as both pilots and mission specialists who are assigned primary responsibilities for carrying out operations related to payloads or experiments. Due to these increased demands, astronaut training programs have had to evolve to ensure that they meet the new higher standards required.

Recent developments in commercial spaceflight have seen the requirement for astronauts to learn and operate a number of new vehicles, whilst often also being involved in the development of their displays, habitability, and human factors. Therefore, astronaut support and training that ensures the safe use and operation of these new spacecraft is ever evolving.

The main difference that exists between training approaches employed by NASA, compared to Roscosmos, is the level of autonomy permitted to the astronauts with regards to decision making concerning technical maintenance and repair of the spacecraft. NASA astronauts are trained to work closely with Mission Control Centers (MCC), and no repairs are undertaken without consent of the MCC, whereas Roscosmos cosmonauts are trained to be able to fix problems by themselves [

1]. This difference in approach is highlighted by the high level of scenario-based team training that NASA conducts with its astronauts and ground crew prior to launch, compared to the Russians, who ensure that all cosmonauts receive a significant level of training with regards to engineering, and troubleshooting of technical problems.

Historically training practices initially employed by NASA during the space race and shuttle missions, focused heavily on the practice of mission operations for specific flight plans and mission roles [

2]. However, the construction of the ISS saw astronaut training requirements change to include a broader set of skills, which could be used to accomplish a wider array of tasks. This stems from the fact that the ISS consists of several modules, which have been developed by different international partners, consisting of the Canadian Space Agency (CSA), European Space Agency (ESA), Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), NASA, and Roscosmos, each of which performs distinct key functions necessary for the operation of the station. It is therefore essential that the crew are familiar with all modules and possess the required knowledge to operate their systems [

3].

3.2. U.S., NASA

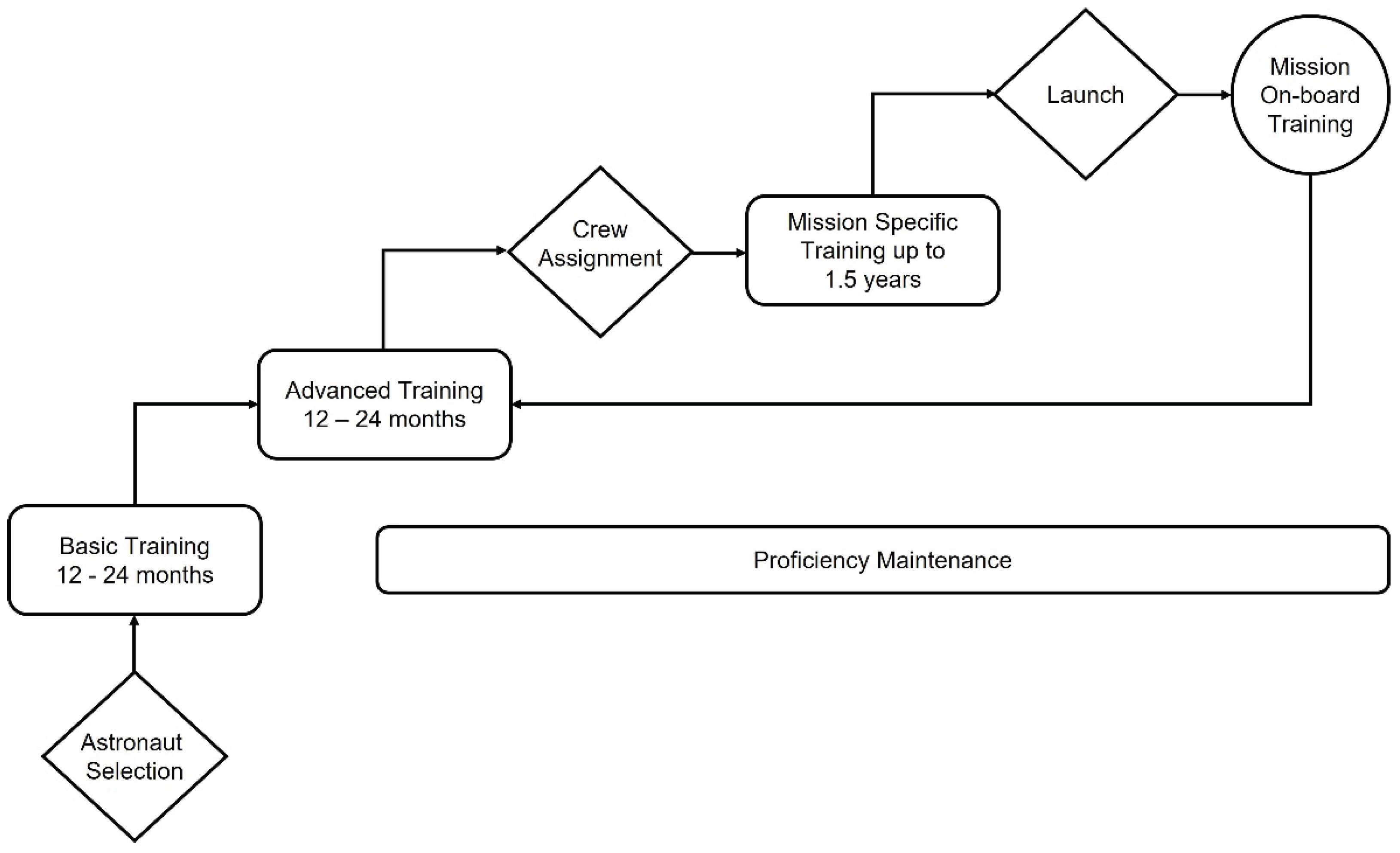

NASA’s astronaut candidates (known as ASCANs) are currently provided with two years of basic training, which includes familiarization with all the American modules and their functions. This is complemented by a curriculum designed to teach the fundamental skills vital for living and working onboard the ISS (see

Table 1). ASCANs must satisfactorily meet standards set in eight technical and team disciplinary areas, before they can progress to the next stage of advanced training as qualified astronauts [

4]. By the time an astronaut is assigned to a mission, they will have completed four stages of training: basic, advanced, mission-specific (for their assigned mission), and on-board mission training. Alternative names may be given to these training phases by different space organizations, but they all essentially function as equivalent stages in the training process. A fourth stage of ‘in-flight’ or proficiency maintenance training is also implemented once astronauts are active within the corps and begin flying on missions.

Note that in

Figure 1, the numbers of years for each training phase are indicative only. The total duration of the NASA three-phase training programme can range from 2.5 years to 5.5 years (or more). Training is tailored partially to the trainees’ background, and each astronaut completes the different phases and reaches proficiency at a different pace, depending on their previous experience, skills and tasks assigned to a mission.

3.3. Russia, Roscosmos

Russian cosmonauts also receive four stages of training in total; basic, advanced, increment-specific (for a given mission), and in-flight training [

5]. Much like NASA, the basic training focuses on acquiring the necessary skills and knowledge that are required before more in-depth training activities can take place. In the early days of human spaceflight, during the 1960s, the Russian training program, which is based at the Gagarin Cosmonaut Training Center (GCTC), was primarily established by professionals working within the military domain. Cosmonauts who flew on the Vostok and Voskhod spacecraft typically had limited input into the vehicle control, and it was not until the advent of the Soyuz missions, that it became necessary for the crew to take on piloting roles, that required them to receive increased levels of technical and engineering training [

6]. Later, as the construction of orbital stations began to take place during the 1970s onwards, starting with the Salyut, the cosmonaut training program saw a shift in requirements, to satisfy the more complicated, longer duration missions that developed as a result. Today, crew members are trained to operate the Russian segment of the ISS along with the Soyuz transport vehicle during their basic training, with an emphasis placed upon preparing for off-nominal situations, and creatively solving new challenges [

7].

3.4. Europe, ESA

ESA astronauts undergo three stages of training; basic, pre-assignment, and assigned crew, or so-called increment training. Basic training takes place at ESA’s European Astronaut Center (EAC), which was founded in 1990, and prepares candidates for the more in-depth stages of training, by providing them with a solid introduction to the agency and its various activities, along with an overview of other European and cooperative space programs [

8]. Unlike NASA and Roscosmos who were involved in the early days of the Space Race, the inception of ESA’s astronaut corps has from the start always been focused on realizing crew flight readiness for travel to the ISS [

9]. Much like the Americans and Russians, with their respective ISS modules, ESA astronauts spend a considerable amount of time familiarizing themselves with the European developed Columbus module during their basic training period. The EAC houses a Columbus training mock-up, where candidates can perform systems and operational tasks in preparation for flight. Training during this stage is also partially tailored to an individual’s existing set of skills and background, and it is expected that they will each reach competence and proficiency at slightly differing rates [

10].

3.5. China, CNSA

China’s National Space Administration (CNSA) was founded in the early 1990s and since that time the considerable advancements made have led to the establishment of a very successful human spaceflight program, which is currently designated ‘Project 921’. The time between the agency’s establishment, and the flight of its first taikonaut in 2003, has seen the swift development of the taikonaut training program, which is based at the Astronaut Center of China (ACC). During early manned operations, the crew were focused on honing the various flight procedures that would be repeatedly required for future missions, such as launch and re-entry processes, docking and undocking, and practicing for emergency scenarios [

11]. Initial taikonaut candidates were selected from members of the military, but with the Chinese Tiangong research station in orbit, the most recent recruitment cohort of taikonauts also included individuals with backgrounds in areas such as aerospace engineering and science [

12].

3.6. Japan, JAXA

The Japanese human space exploration program began in earnest with the signing of the International Space Station Intergovernmental Agreement, which committed Japan to the cooperative framework laid out for establishing a permanently inhabited civil space station [

13]. Japan’s space agency, JAXA, first flew an astronaut aboard NASA’s Space Shuttle Endeavour in 1992, with the purpose of conducting scientific experiments, and gaining knowledge and experience with regards to the training required for manned spaceflight [

14]. Following on from this event, Japanese astronauts continued to receive training from NASA, in preparation for the role that they would play in the construction and operation of the ISS. From 1999 onwards, astronaut candidates began to receive basic training from JAXA itself, through a newly developed training program, consisting of a year and a half of basic training, followed by advanced and finally increment specific training, interspersed with refresher courses as required [

15]. Basic training covers all of the same key areas that the ISS partner agency’s cover, along with module specific knowledge concerning the Japanese Kibo segment of the ISS.

3.7. Canada, CSA

The Canadian Space Agency is another member of the five core collaborators who operate the ISS, and adhere to a similar training routine as ESA, JAXA, NASA, and Roscosmos, consisting of basic, ongoing, and mission specific training periods. The country’s first round of astronaut recruitment was conducted in 1983, with the aim of training the selected candidates to become payload specialists, that could fly as part of the Space Shuttle program [

16]. Due to this fact, the first Canadian astronaut (Marc Garneau) was sent to conduct his basic training at NASA’s Johnson Space Center (JSC), and it was not until near the end of the decade that the CSA itself was established. Still today Canadian astronauts receive part of their basic training at the CSA headquarters in Quebec, and part at the NASA-JSC.

3.8. International Cooperation

Five of the above six agencies (CSA, ESA, JAXA, NASA, and Roscosmos) have all been involved with the construction and operation of the ISS, and they are overseen at the highest level by the Multilateral Coordination Board (MCB). The MCB in turn has established a Multilateral Crew Operations Panel (MCOP), who are responsible for determining the criteria required for the selection, assignment, and training of all space station crew [

17]. Therefore, although these five agencies are responsible for their own astronauts’ basic training programs, they must all adhere to certain internationally agreed upon standards. China is the only country out of the spacefaring nations whose astronaut training program is not governed by such multilateral agreements.

4. Commercial Entity Astronaut Training Approaches

A variety of private companies have entered the space sector in more recent years, with some developing their own launch vehicles, and consequently their own human spaceflight programs along with them. NASA currently uses the SpaceX Dragon spacecraft to transport both crew and cargo to and from the ISS, through a public-private partnership agreement. The nature of this arrangement ensures that SpaceX therefore receives NASA training for all of their crew. Other commercial companies such as Blue Origin and Virgin Galactic have undertaken suborbital flights with human participants and continue to leverage their niche in the market by offering private astronaut experiences in microgravity.

In the United States, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) is currently prohibited from issuing regulations regarding the health and safety of spaceflight participants, due to a moratorium set by the U.S. Congress [

18]. This was implemented to allow a period of time where the rapidly evolving commercial spacecraft market could be monitored, and a suitable safety framework developed. The moratorium ended in 2023, and therefore until that time there were no nationally recognized regulations with regards to safety and training for commercial human spaceflight activities.

However, in 2006 the FAA did issue a number of ‘human spaceflight requirements for crew and spaceflight participants’, which do include guidance on safety, training and medical standards [

19]. Although these stipulations have only been issued as guidance at present, the FAA continues to work in tandem with spaceflight operators, to better understand the requirements necessary to establish a fully regulated commercial spaceflight sector. However, until such a time arrives, it is the responsibility of the operator to ensure that all crew training is sufficient, and spaceflight participants fully understand the risks involved. Therefore, at present, different companies provide different levels of training, but these tend to include physiological training, (such as, G force training in centrifuges, emergency procedures, zero-g aircraft parabolic flights, motion sickness awareness, survival and altitude training, as well as aerobatic flight training), simulator training, and familiarization with safety protocols [

20]. Unlike the training programs operated by space agencies that take years to complete, those offered by commercial entities vary in length. Axiom offers a 17 week course for all private astronauts, whilst Blue Origin boasts the ability to get its participants flight ready in just 2 days for suborbital experiences [

21,

22].

5. Conclusions

Astronaut training has evolved from narrowly focused, mission-specific preparation for short-duration flights into a highly complex, multidisciplinary process designed to support long-duration, multinational, and increasingly commercial space missions. Early training programs emphasized piloting skills, technical aptitude, and individual performance, reflecting the demands and constraints of early spacecraft and national space race priorities. Over time, the construction and operation of long-term orbital infrastructure, most notably the International Space Station, required a fundamental shift toward broader systems knowledge, teamwork, cultural awareness, and adaptability to unforeseen situations.

Although major space agencies follow similar multi-phase training structures, notable differences remain in training philosophy, particularly with respect to crew autonomy, engineering proficiency, and interaction with ground control. These differences reflect historical experience, organizational culture, and mission design. At the same time, international coordination mechanisms have ensured a high degree of standardization among ISS partner agencies.

The rapid growth of commercial human spaceflight introduces new challenges and opportunities for astronaut training, including shorter training timelines, diverse participant backgrounds, and evolving regulatory oversight. As human spaceflight moves toward future missions beyond low Earth orbit, astronaut training programs will need to continue adapting to ensure crew safety, mission success, and effective human performance in increasingly demanding environments.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft preparation, VP; writing—review and editing, VP, SE. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The contributions of Dr Amy Holt, and Debbie Trainor are acknowledged.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| NASA |

National Aeronautics and Space Administration |

| ESA |

European Space Agency |

| ISS |

International Space Station |

| LEO |

Low Earth Orbit |

| CSA |

Canadian Space Agency |

| JAXA |

Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency |

| MCC |

Mission Control Center |

| ASCANs |

Astronaut Candidates |

| GCTC |

Gagarin Cosmonaut Training Center |

| EAC |

European Astronaut Center |

| CNSA |

China National Space Administration |

| ACC |

Astronaut Center of China |

| MCB |

Multilateral Coordination Board |

| FAA |

Federal Aviation Administration |

| MCOP |

Multilateral Crew Operations Panel |

| JSC |

Johnson Space Center |

References

- "Cosmonaut training overview; RuSpace". Archived from the original on 2020-07-26. Available online https://web.archive.org/web/20200726111624/http://suzymchale.com/ruspace/training.html (Accessed on 15 December 2025).

- D.L. Dempsey, I. Barshi (2020). Applying Research-Based Training Principles: Towards Crew-Centered, Mission-Oriented Space Flight Training, in: Proc. Int. Conf. Appl. Hum. Factors Ergon. AHFE Affil. Conf., Orlando, Florida, U.S.A. Available online https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.1201/9780429440854-4/applying-research-based-training-principles-donna-dempsey-immanuel-barshi (Accessed on 15 December 2025). [CrossRef]

- National Research Council (2011). Preparing for the High Frontier: The Role and Training of NASA Astronauts in the Post-Space Shuttle Era, The National Academies Press, Washington, DC. https://doi.org/10.17226/13227. (Accessed on 15 December 2025). [CrossRef]

- I. Barshi, D.L. Dempsey (2017). ISS Training Best Practices and Lessons Learned. Available online https://ntrs.nasa.gov/citations/20170009779 (Accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Gagarin Research & Test Cosmonaut Center (2022). Cosmonauts’ training at the Center, Yu Gagarin Res. Test Cosmonaut Centre. Available online http://www.gctc.su/main.php?id=117 (Accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Gagarin Cosmonaut Training Center (2022). Stages of development of selection and cosmonaut training system (СОПК), Gagarin Res. Test Cosmonaut Centre. Available online http://www.gctc.su/main.php?id=244 (Accessed on 15 December 2025).

- S. Krikalev, A.A. Kuritsyn, I.G. Sokhin (2011). Organization of ISS crew training and further development of cosmonaut training system, in: Proc. 62nd Int. Astronaut. Congr., Cape town, South Africa, pp. 1–7. Available online https://iafastro.directory/iac/archive/browse/IAC-11/B3/5/9840/ (Accessed on 15 December 2025).

- ESA (1998). The European Astronaut Centre (EAC) – Past and Present Achievements, ESA Bull. 130, 13–17. Available online https://www.esa.int/About_Us/ESA_Publications/ESA_Publications_Brochures/ESA_BR-130_The_European_Astronaut_Centre_EAC_Past_and_Present_Achievements (Accessed on 15 December 2025).

- E. Messerschmid, J.P. Haignere, K. Damian, V. Damann (2000). EAC training and medical support for International Space Station astronauts, ESA Bull. 104, 101–108. Available online https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14763461/ (Accessed on 15 December 2025).

- ESA (2015). Getting ready for space - Astronaut training. Available online https://esamultimedia.esa.int/multimedia/publications/Getting_ready_for_space/Getting_ready_for_space.pdf (Accessed on 15 December 2025).

- China Space Report (2016). Astronaut Selection and Training, News Anal. Chinas Space Programme. Available online https://chinaspacereport.wordpress.com/programmes/astronaut-selection-training/ (Accessed on 15 December 2025).

- CNSA (2018). China to select astronauts for its space station, China Natl. Space Adm. Available online http://www.cnsa.gov.cn/english/n6465652/n6465653/c6799623/content.html (Accessed on 15 December 2025).

- ESA (1998). The Space Station Cooperation Framework, ESA Bull. 94, 49–56. Available online https://www.esa.int/esapub/bulletin/bullet94/FARAND.pdf (Accessed on 15 December 2025).

- JAXA (2004). History of Japan’s manned space activities, JAXAs Astronauts. Available online https://iss.jaxa.jp/astro/history_e.html (Accessed on 15 December 2025).

- JAXA (2001). Basic Training for International Space Station Crew Candidates, JAXAs Astronauts. Available online https://iss.jaxa.jp/astro/ascan/ascan01_e.html (Accessed on 15 December 2025).

- A.B. Godefroy (2017). The Canadian Space Program, From Black Brant to the International Space Station, Springer International Publishing. Available online https://www.scribd.com/document/618868514/The-Canadian-Space-Program-From-Black-Brant-to-the-International-Space-Station-Andrew-B-Godefroy-auth-z-lib-org. (Accessed on 15 December 2025).

- ESA/NASA (1998). Memorandum of Understanding between the National Aeronautics and Space Administration of the United States of America and the European Space Agency concerning cooperation on the civil International Space Station. Available online https://download.esa.int/docs/ECSL/ISS_NASA-ESA-MoU.pdf (Accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Federal Aviation Administration (2017). Report to Congress: FAA Evaluation of Commercial Human Space Flight Safety Frameworks and Key Industry Indicators. Available online https://www.faa.gov/about/plansreports/evaluation-commercial-human-spaceflight-safety-frameworks-and-key-industry (Accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Federal Aviation Administration (2006). Human Space Flight Requirements for Crew and Space Flight Participants. Available online https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2006-12-15/pdf/E6-21193.pdf (Accessed on 15 December 2025).

- T. Sgobba, L.B. Landon, J.-B. Marciacq, E. Groen, N. Tikhonov, F. Torchia (2017). Chapter 16 - Selection and training, in: T. Sgobba, B. Kanki, J.-F. Clervoy, G.M. Sandal (Eds.), Space Saf. Hum. Perform., Butterworth-Heinemann: pp. 721–793.

- Axiom Space (2022). Private Astronauts. Available online https://www.axiomspace.com/private-astronauts (Accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Blue Origin (2022). Book your flight on New Shephard, Blue Orig. - Benefit Earth. Available online https://www.blueorigin.com/new-shepard/fly/ (Accessed on 15 December 2025).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).