1. Introduction

Neurological conditions have long ranked among the leading causes of disability, long-term dependence on others, and loss of independence. According to the World Health Organization, such conditions account for around 10% of the global burden of disease, and their prevalence is increasing as populations age. Current projections suggest that, over the coming decades, the number of people requiring daily care due to neurological disorders may rise by as much as 40–60%. This trend places heavy demands on healthcare systems, social care services, and the families who most commonly assume the role of primary carers [

1,

2,

3].

In Poland, as in many other European countries, family carers provide the vast majority of long-term support for people with severe neurological deficits. European estimates indicate that as much as 80–85% of all long-term care is delivered informally: by relatives, friends and neighbours. Although this form of care is largely “invisible” to the system, its economic significance is considerable; in some EU member states, its estimated value reaches 2–3% of GDP [

4,

6].

Caring for patients with neurological conditions involves several distinctive characteristics that intensify the load placed on carers [

7]. First, most neurological disorders are chronic and progressive. Second, many patients experience a combination of motor impairments, cognitive decline, behavioural changes and communication difficulties. Third, the clinical course is often unpredictable, with periods of stability interspersed with sudden deterioration. Finally, many neurological diseases entail a gradual loss of the patient’s former identity, which carers often find particularly painful and emotionally taxing [

8,

10,

11].

Research conducted among populations living with dementia, Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, epilepsy and stroke shows that carers experience exceptionally high levels of strain. Brodaty and Donkin describe this burden as “a constant battle on two fronts”: on the one hand, against the symptoms of the illness, and on the other, against the carer’s own fatigue, uncertainty, anxiety and sense of losing control [

12]. Among carers supporting people after a stroke, physical challenges tend to dominate, particularly those related to transfers, personal hygiene and feeding. In dementia, by contrast, the main burden arises from cognitive decline and behavioural disturbances. In Parkinson’s disease, the nature of strain shifts with the progression of symptoms: from predominantly motor problems to escalating neuropsychiatric complications [

9,

10].

Theoretical models have played an important role in understanding caregiver burden. Pearlin’s Stress Process Model, for instance, posits that strain results from the interaction between primary stressors (such as symptoms of the illness, loss of independence and behavioural problems), secondary stressors (including role conflict and financial strain), and available resources, such as social support and coping strategies. Empirical findings demonstrate that a combination of strong primary stressors and insufficient social support leads to chronic emotional overload [

12]. Another influential framework, Lazarus and Folkman’s transactional model of stress and coping, holds that the caregiver’s subjective appraisal of the situation determines both their coping strategies and the intensity of stress [

4,

13].

Despite a substantial body of research, studies involving mixed neurological populations remain scarce, even though such groups more closely mirror clinical reality, as patients commonly present with overlapping motor, cognitive and behavioural impairments. This gap is particularly visible in Central and Eastern Europe, where system-level support for family carers is less developed than in Scandinavian or Western European contexts. In Poland, for example, respite care is difficult to access, psychological support for carers is limited, and support pathways are opaque and poorly coordinated [

6,

14,

15,

16,

17].

Against this backdrop, it has become increasingly important to investigate both the scope and the nature of support provided by carers of people with neurological conditions, as well as the factors that modulate caregiver burden. Our study concentrates on the active role of carers in the care process, analysing the forms of support that they provide on a daily basis and the conditions that shape these caregiving practices.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Research Methods

This study was designed as a cross-sectional quantitative investigation aimed at assessing caregiver burden and the scope of support provided by caregivers to individuals with neurological conditions. Data were collected using a diagnostic survey method, which enabled the examination of both subjective perceptions and objective aspects of the caregiving situation. The CAWI method (Computer-Assisted Web Interviewing) was employed, using an online questionnaire completed independently by participants via a computer or mobile devices.

Eligibility criteria included: age ≥ 18 years; provision of unpaid care (informal caregiving) to a person with a neurological condition for at least one month; and the ability to complete the questionnaire independently. Eligibility was verified through questionnaire items. The sole exclusion criterion was lack of informed consent.

The research instrument was a 44-item questionnaire comprising both an author-deigned section and a standardised scale addressing the main research objective. The questionnaire was administered electronically in a manner ensuring respondent anonymity.

The author-developed section included sociodemographic characteristics, caregiving workload, and proxy reporting, whereby caregivers provided information on the care recipient’s health status, functional capacity, and the relationship between these variables. The standardised instrument used was the Berlin Social Support Scales (BSSS), specifically the caregiver version, Actually Provided Support. This subscale assesses the scope and type of support provided by caregivers, including emotional, instrumental, and informational support in daily care. Responses were rated on a four-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating greater levels of support. The internal consistency of the scale was high (Cronbach’s α = 0.86).

Statistical analyses were performed using STATISTICA 10 (StatSoft). Descriptive statistics were calculated, including mean, median, standard deviation, and minimum and maximum values. Differences between quantitative and qualitative variables were analysed using the Kruskal–Wallis test, Mann–Whitney U test, and Friedman test, while associations between variables were assessed using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (Spearman’s R). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

2.2. Study Organisation and Procedure

The study was non-interventional and involved the anonymous completion of an online questionnaire. No personally identifiable data were collected, and participation did not entail any risk or burden for respondents. In accordance with Polish law and the regulations governing research involving human participants, studies of this type do not require approval from a bioethics committee.

The questionnaire was administered via the dedicated online platform Google Forms, which enabled the automatic recording and archiving of data. Before deciding whether to participate, potential respondents were provided with information regarding the purpose of the study, as well as assurances of anonymity and voluntary participation. Upon providing informed consent, participants were granted access to the first question of the questionnaire. If consent was not given, the form automatically closed without allowing access to the survey items.

Participants were free to withdraw from the study at any stage without providing a reason. Data were analysed exclusively in aggregated form.

2.3. Participants

The study included 104 informal caregivers of individuals with various neurological conditions. The sample was heterogeneous with respect to age, educational level, place of residence, and economic status, which allowed for the capture of a broad spectrum of caregiving experiences and the identification of factors associated with increased or reduced caregiver burden. The sociodemographic characteristics of the participants are presented in

Table 1.

The caregiver sample was predominantly female (86.4%), with more than half of participants aged 45 years or younger (55.8%). Over half of the respondents reported having higher (tertiary) education (54.4%). A considerable proportion resided in rural areas, where access to caregiving and rehabilitation services is often limited, which may have contributed to increased caregiver burden.

3. Results

The caregivers participating in the study provided daily, long-term care to individuals with chronic and progressive conditions that impaired patients’ functioning and increased the extent of assistance required. The care recipients represented a heterogeneous group with respect to the type of condition, stage of disease progression, and associated health consequences. The majority of patients had severe neurological or neurodegenerative disorders, which frequently led to reduced independence, functional decline, and an increased risk of complications. The socio-clinical characteristics of the care recipients are presented in

Table 2.

Caregiving for a close relative required carers to manage nearly all aspects of the care recipient’s daily life, including assistance with personal hygiene, medication administration, and mobility, as well as, in many cases, constant supervision. The nature and progression of the care recipients’ conditions determined both the scope of caregiving responsibilities and the level of caregiver fatigue, providing essential context for the interpretation of the subsequent findings.

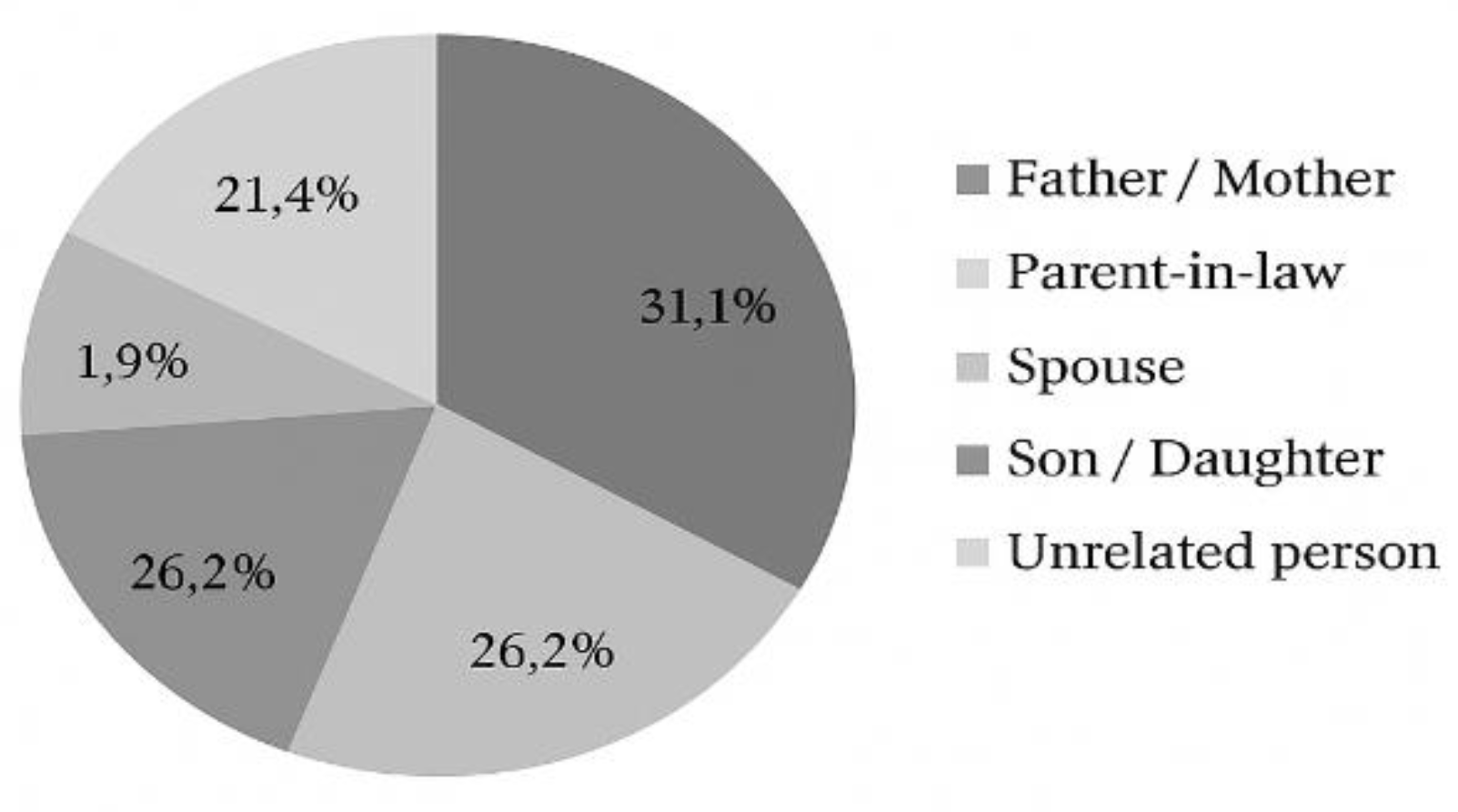

The caregivers most commonly provided care for a parent (31.1%, n = 32) or for more distant relatives (26.2%, n = 27). For 21.4% of respondents (n = 22), the care recipient was not a family member, while 17.5% (n = 18) were caring for a parent-in-law (

Figure 1)

Nearly 44% of caregivers did not reside with their care recipients, while the remainder lived with them either permanently (38.8%) or intermittently (17.5%). The vast majority of respondents (82.5%) reported receiving assistance from others in the provision of care. The most frequently identified sources of support were spouses (42.4%), siblings (37.7%), children (14.1%), institutional services or staff (15.3%), as well as acquaintances (11.8%) and friends (11.8%).

Despite this, 40.8% of participants (n = 42) reported not using any form of institutional support. Among those who did, one or more types of assistance were utilised, most commonly financial support (50.5%), a care allowance (43.7%), a caregiver benefit (20.4%), and formal care services (10.7%).

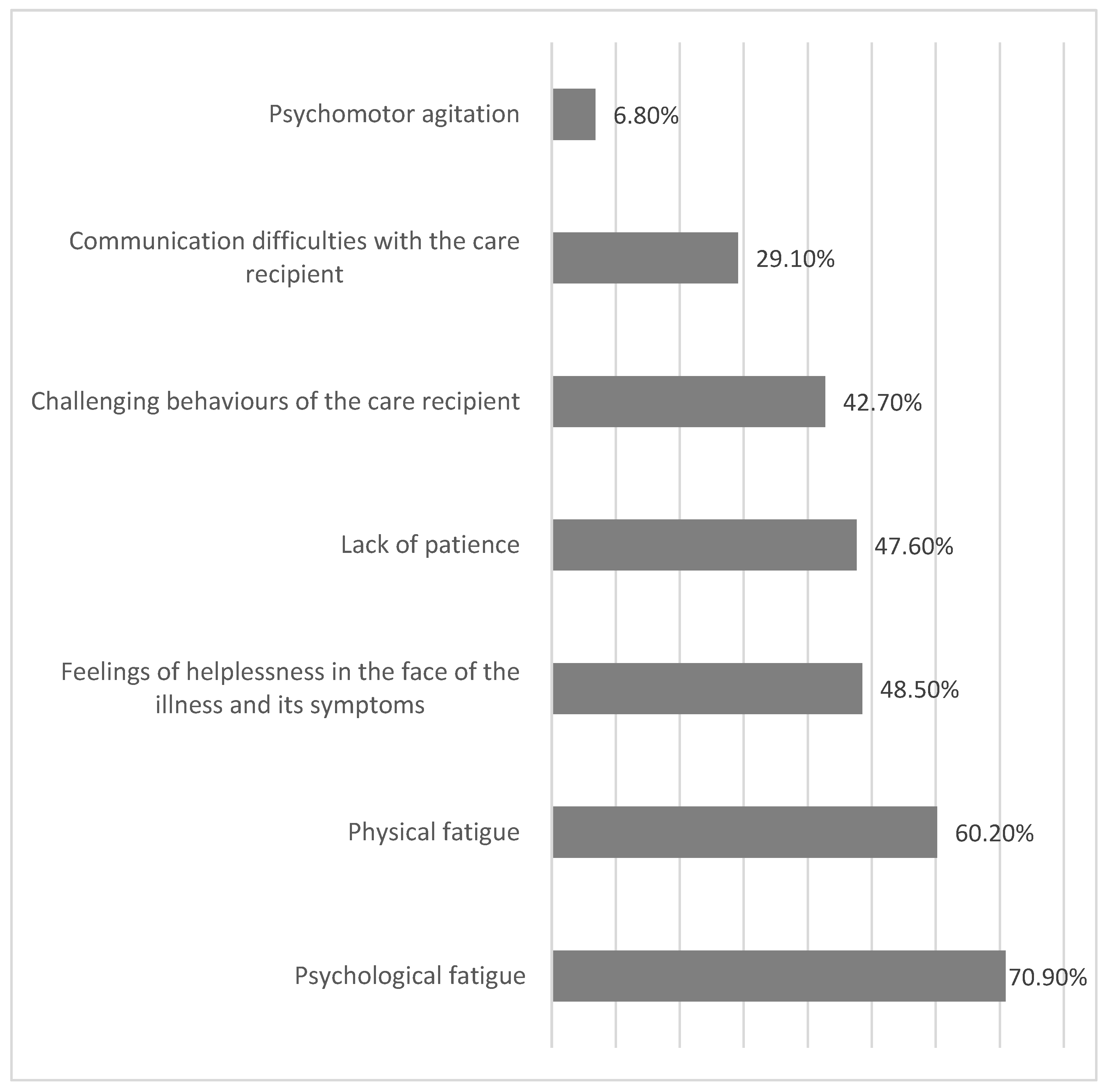

Caregivers also reported difficulties encountered in the course of daily care, often selecting more than one response (

Figure 2). The most prevalent burden was psychological fatigue (70.9%), with many respondents reporting a persistent sense of tension and responsibility. Physical fatigue was the second most frequently reported burden (60.2%), attributable to the physical demands of caregiving tasks and repetitive daily activities.

The analysis showed that among younger caregivers (aged 45 years or younger), a statistically significant association was observed specifically with feelings of helplessness in response to illness and its symptoms. No significant relationships were found between the other reported caregiving difficulties and caregivers’ gender, age, receipt of support from others, or use of financial assistance.

The study also identified external factors that hinder caregiving for individuals with disabilities. The most frequently reported barriers were limited access to healthcare services reimbursed by the National Health Fund (NFZ) (47.6%, n = 49) and the absence of respite care or someone who could temporarily assume caregiving responsibilities (38.8%, n = 40). Fewer than one in three caregivers identified additional external barriers to care, such as architectural barriers (32.0%, n = 33), insufficient information about available forms of support (30.1%, n = 31), or other factors. These responses suggest that caregivers often function in an environment that fails to provide adequate systemic support, thereby intensifying the burden associated with daily caregiving.

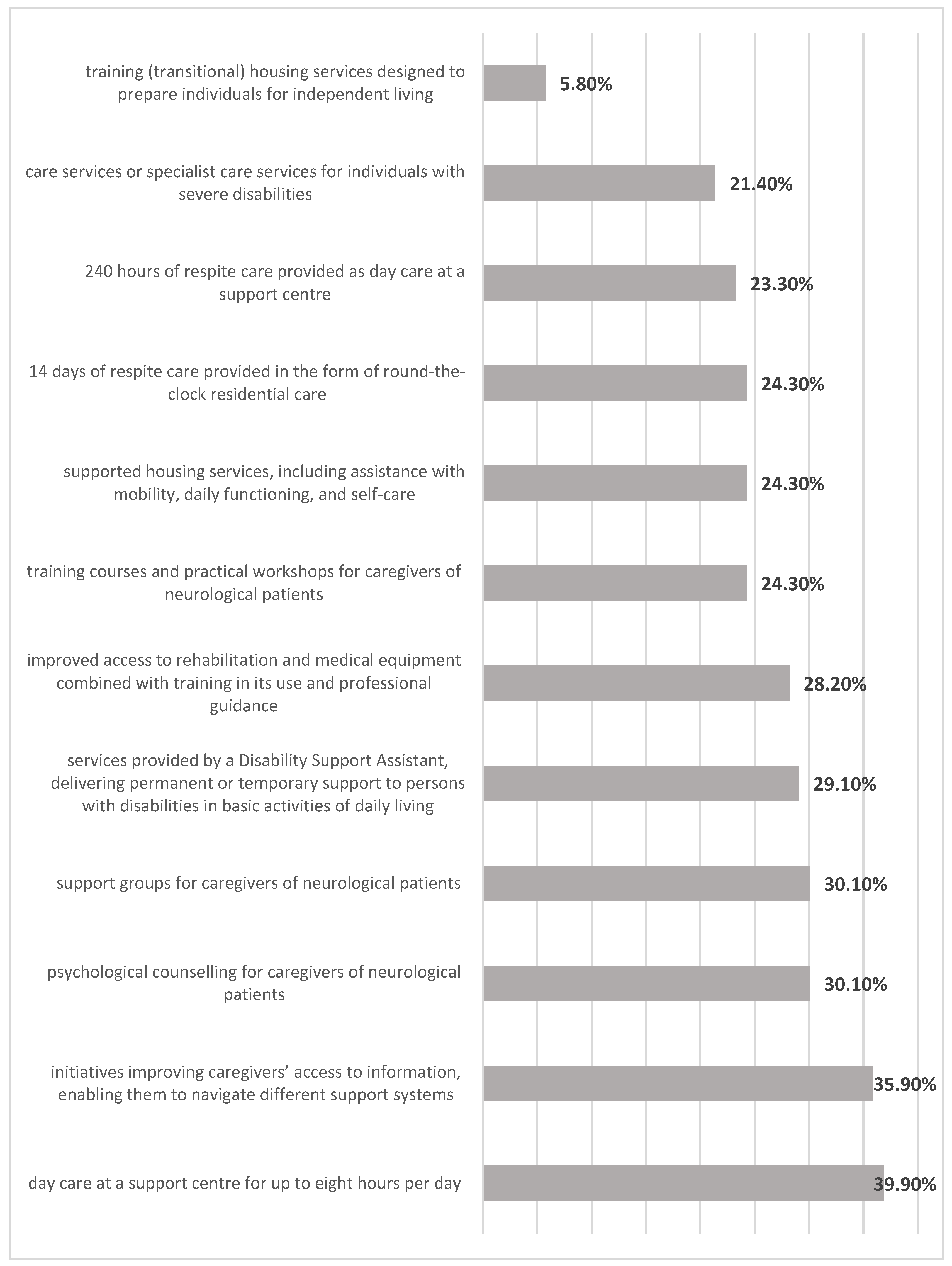

With regard to potential forms of relief from caregiving responsibilities, respondents most frequently expressed interest in day care services at a support centre for up to eight hours per day (36.9%, n = 38), as well as initiatives designed to improve caregivers’ access to information that would enable them to navigate different support systems, funding schemes, and benefits and thereby enhance the quality of care (35.9%, n = 37). Slightly lower levels of interest were reported for psychological counselling for caregivers of neurological patients (30.1%, n = 31), support groups for caregivers of neurological patients (30.1%, n = 31), and services provided by a Disability Support Assistant, which include permanent or temporary assistance with basic activities of daily living necessary for social, occupational, or educational participation (29.1%, n = 30). Improved access to rehabilitation and medical equipment, combined with training on how to use it and professional guidance, was also indicated by a similar proportion of respondents (28.2%, n = 29). Fewer than one in four caregivers expressed interest in other forms of relief from caregiving responsibilities (

Figure 3).

Women were significantly more likely to express interest in support groups for caregivers of neurological patients (p = 0.0440). Caregivers who received financial support more frequently reported interest in a 14-day period of respite care provided as round-the-clock residential care (p = 0.0498). By contrast, caregivers who did not receive financial support more often preferred psychological counselling for caregivers of neurological patients (p = 0.0054). No significant associations were observed between the potential use of support resources and caregivers’ age, educational attainment, receipt of assistance from others, or use of financial benefits.

A key component of the study was the analysis of the standardised Berlin Social Support Scales (BSSS). The findings indicated that caregivers provided their care recipients with a relatively high degree of support. Mean scores were 21.44 for emotional support, 7.26 for instrumental support, and 4.19 for informational support (

Table 3).

The emotional social support currently provided by caregivers was predominantly rated as high (68.0%, n = 70), with the remaining respondents reporting a moderate level (32.0%, n = 33). Similarly, nearly two thirds of caregivers reported providing a high level of instrumental support. Specifically, 67.0% of caregivers (n = 69) indicated a high level of instrumental support, 28.1% (n = 30) a moderate level, and only 3.9% (n = 4) a low level. Informational social support was reported as high by 44.7% of caregivers (n = 46) and as moderate by 37.9% (n = 39), while 17.5% (n = 18) indicated a low level of informational support. Satisfaction with the social support currently received was most frequently rated as moderate (43.7%, n = 45), followed by high (31.1%, n = 32), while one quarter of caregivers reported low satisfaction (25.2%, n = 26).

Female caregivers were significantly more likely to report high levels of emotional social support (p = 0.0054) and instrumental social support (p = 0.0277) currently provided to their care recipients (

Table 4).

The analysis of the relationship between gender and levels of support provision indicated that women more frequently reported high levels of emotional and instrumental support. This pattern is consistent with findings from studies conducted in other caregiver populations, in which women tend to be more involved in activities related to direct caregiving and the organisation of care. This may be explained both by socially entrenched gender role divisions and by differences in caregiving practices between women and men.

It is important to note, however, that the observed differences do not necessarily reflect variations in the quality of care provided, but rather the gendered distribution of caregiving tasks. Men may be more involved in other forms of support that are not adequately captured by the measurement tool used in this study. The findings therefore underscore the importance of applying a gender-sensitive perspective when designing educational and organisational interventions for caregivers, as well as the need to develop solutions that enable a more equitable distribution of caregiving responsibilities in the family.

Age was not found to have a significant effect on the degree of emotional, instrumental, or informational support (

Table 5).

The analysis of the relationship between caregivers’ age and the support that they provide indicated that higher levels of buffering (protective) support were more common among caregivers aged over 45 years. This pattern may be indicative of differences in caregiving at various stages of life. Younger caregivers are more likely to combine caregiving with paid employment and other responsibilities, which can limit their capacity to take on additional caregiving tasks. On the other hand, older caregivers—benefiting from greater life experience and more stable occupational or family circumstances—may be better positioned to organise and safeguard care.

Age-related differences in support provision point to the need to tailor forms of assistance to the specific circumstances of different age groups. Younger caregivers may need support that helps them balance caregiving with work, whereas support for older caregivers may be better directed towards maintaining physical capacity and accessing respite services. Overall, these findings reveal that caregivers’ age is an important factor shaping both the type of support provided and the strategies employed in daily care

4. Discussion

Caring for people with neurological conditions is highly demanding, both physically and emotionally. These conditions—chronic, progressive, and unpredictable—disrupt fundamental aspects of human functioning and lead to a gradual loss of independence. As a result, caregivers take on many roles. In addition to providing day-to-day care, they often become the main organisers of the care recipient’s daily life, as well as their advocates, companions, and sources of emotional support [

3,

18] . Research increasingly recognises caregiving as a complex and deeply human experience, involving care, constant vigilance, and a form of responsibility that goes beyond routine tasks. This complexity is well described in established theoretical models, which help explain the psychosocial consequences of the caregiving role [

19,

20,

21].

Pearlin’s stress process model suggests that caregiver burden arises from the interaction between primary stressors—such as disease symptoms, loss of independence, and behavioural disturbances—and secondary stressors, including role conflicts, financial difficulties, institutional barriers, and emotional strain. At the same time, caregivers may draw on resources that help mitigate stress, including social support, a sense of meaning, and caregiving skills. Similarly, Lazarus and Folkman’s transactional model of stress and coping posits that individuals’ subjective appraisal of a situation—whether it is seen as a threat, a loss, or a challenge—determines the choice of coping strategies and the perceived level of burden. From this perspective, the support that caregivers provide serves two functions: it meets the needs of the person receiving care and helps caregivers regulate their own emotions and maintain psychological balance in a highly demanding situation.

The findings of this study clearly show that caregivers of people with neurological conditions provide support of high intensity. The vast majority of respondents reported moderate to high levels of emotional, instrumental, and informational support. The particularly high level of emotional support highlights the central importance of relationships in caregiving: presence, patience, understanding, and companionship form the basis of the care recipient’s sense of safety and security [

22].

Instrumental support—such as assistance with personal care, physical transfers, medication administration, and organising daily routines—places a substantial physical demand on caregivers. This observation is consistent with previous research on caregivers of people after stroke, with Parkinson’s disease, and with dementia [

16]. Informational support, although provided to a lesser extent than emotional and instrumental support, illustrates caregivers’ active efforts to seek knowledge needed for everyday decision-making related to treatment and care organisation.

High levels of support—particularly emotional and instrumental—were more commonly reported by women. This pattern has been widely documented in the literature, which shows that women more often assume caregiving roles, tend to be more emotionally involved, and have greater experience with caregiving tasks. At the same time, research also indicates that women are more vulnerable to prolonged emotional fatigue, feelings of overload, and caregiver burnout. This supports the case for targeted support measures for female caregivers. Age-related differences were also observed. Older caregivers reported higher levels of buffering (protective) support, which may be associated with higher emotional stability, broader life experience, and more established ways of coping. These findings are consistent with both Pearlin’s stress process model and the transactional model of stress and coping proposed by Lazarus and Folkman [

19,

23] .

Psychological fatigue emerges from the analysis as the most significant burden for caregivers. It is linked to chronic stress, a constant sense of responsibility, the unpredictable progression of neurological illness, and limited opportunities for rest. Physical fatigue, in turn, results from the frequent performance of repetitive and physically strenuous caregiving tasks that require strength and endurance. These findings are consistent with international research showing that caregivers of people with neurological disorders experience greater burden than caregivers in many other disease groups [

24].

External factors that make caregiving more difficult are also of great importance. The main barrier reported by respondents was limited access to publicly funded healthcare services. This included long waiting times, a shortage of available rehabilitation appointments, and difficulties in accessing specialist care. European research identifies inadequate institutional support and limited access to respite services as persistent problems, particularly in Central and Eastern European countries. Another major barrier was the absence of someone who could temporarily take over caregiving duties, which increases caregivers’ feelings of isolation and constant strain. Gaps in information—such as difficulties understanding benefit systems and the absence of clear and accessible support pathways—further add to uncertainty and confusion.

Caregivers’ preferences regarding forms of respite support clearly reflect their everyday needs. The most frequently indicated option was day care for the care recipient at a support centre, which points to a strong need for relief, rest, and recovery time. Access to information and education was also seen as highly important. These areas are often overlooked in healthcare systems, despite their crucial role in strengthening caregivers’ sense of competence and ability to cope with their responsibilities. Support groups, psychological counselling, and services provided by a Disability Support Assistant were mentioned less often, but still attracted notable interest [

20,

24,

25,

26,

27].

These findings show that caregivers continue to operate within a system that fails to provide sufficient formal or informational support. Their strong commitment, despite institutional shortcomings, demonstrates the considerable social value of informal caregivers. At the same time, the results underline the need for strategies that strengthen caregivers’ resources and reduce the negative effects of caregiving burden. This is essential not only for caregivers’ wellbeing, but also because the quality of informal care is one of the most important factors influencing the quality of life of people living with neurological conditions [

28,

29,

30].

Implications for Practice

Expansion of respite care services, including both day care and 24-hour options.Caregivers clearly need opportunities for temporary relief from caregiving. Access to respite care can substantially reduce the risk of physical and emotional exhaustion.

Improved access to rehabilitation, neurological consultations, and publicly funded healthcare services., Limited availability of these services was one of the most frequently reported barriers. Improving access may reduce waiting times, ease the burden on caregivers, and increase the effectiveness of formal care.

Strengthening information and educational support systems.Caregivers require clear, reliable, and practical information about the illness, available benefits, medical equipment, and care organisation. Closing information gaps may reduce uncertainty and enhance caregivers’ confidence and sense of competence.

Provision of psychological support and support groups. Although not the most commonly selected forms of assistance, psychological support and peer groups can make a difference in preventing caregiver burnout and supporting emotional wellbeing.

Training and educational programmes for caregivers, focusing on home-based care, managing crisis situations, navigating the healthcare system, and using medical and rehabilitation equipment.

Development of coordinated, interdisciplinary care pathways that consider the needs of both care recipients and caregivers, in line with Integrated Care initiatives promoted across Europe.

Strengths and limitations of the Study

A major strength of this study is its focus on the support that caregivers actually provide, rather than only on their perceived needs or subjective assessments. This approach is used less often in research, but it provides a clearer picture of what caregiving involves in everyday practice. Another important strength is the use of proxy reporting, which combines information provided by caregivers with data on the health and functioning of the care recipients. This makes it possible to interpret the findings in relation to the clinical characteristics of the person receiving care, which is rarely done in studies involving people with different neurological conditions.

The study also gains value from being conducted in the context of the Polish healthcare system, where research on caregivers of people with neurological conditions is still limited. The findings help fill an important gap in knowledge and may inform future research, service planning, and policy development.

The main limitation of the study is its cross-sectional design, which restricts the ability to assess how caregiving changes over time or how it relates to disease progression. In addition, the data are based on self-report, which carries a risk of bias stemming from caregivers’ perceptions. Although this limitation is common in survey-based studies, it should be considered when interpreting the results.

5. Conclusions

Caregivers of people with neurological conditions provide ongoing, intensive support, especially emotional and practical support. This clearly confirms their central role in enabling the daily functioning and safety of care recipients.

Informational support is provided less often, largely due to poor access to reliable information and the complexity of the healthcare system. This finding demonstrates a clear and pressing need for better education and guidance for caregivers.

Women provide high-intensity care more frequently than men, which confirms well-documented gender differences in caregiving roles. This finding requires gender to be explicitly taken into account when planning support interventions for caregivers.

Caregivers aged over 45 report higher levels of buffering (protective) support, which is likely linked to greater life experience and more developed coping skills.

Psychological and physical exhaustion are the most serious difficulties reported by caregivers, resulting from long-term burden and insufficient opportunities for rest. These findings clearly support the need to expand and prioritise respite care services.

Limited access to healthcare services and the absence of temporary replacement care are the main barriers to effective caregiving. These issues can be addressed through better availability of social services and better coordination between health and social care systems.

Caregivers’ preferred forms of respite support—such as day care for care recipients and easier access to information about benefits—point to priority areas for system-level actions with real potential to reduce caregiver burden

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.P. and Z.S.; methodology, M.P. and Z.S.; software, M.P. and Z.S.; validation, M.P. and Z.S..; formal analysis, M.P., Z.S.; AG and M.J.; investigation, M.P..; resources, M.P. and Z.S.; data curation, M.P. and Z.S.; writing— M.P., Z.S.; AG and M.J.; writing—review and editing, M.P. and A.G; visualization, M.P., A.G and M.J.; supervision, M.P.; project administration, M.P.; funding acquisition, M.P., Z.S.; AG and M.J All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki,.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data can be obtained by contacting the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.:

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BSSS |

Berlin Social Support Scales |

References

- Bartoszek, A; Slusarska, B; Deluga, A; Nowicki, G; Piasecka, K; Kocka, K; et al. Selected determinants of burden among informal caregivers according to the COPE Index in home care for patients with functional impairment. 2019, 59, 164–71. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, L; Zhao, X; Chen, X; He, Y; Liu, J; Xian, J; et al. Caregiver Burden and Its Associated Factors Among Family Caregivers of Hospitalized Patients with Neurocritical Disease: A Cross-Sectional Study. J Multidiscip Healthc 2024, 17, 5593–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryś, B; Bąk, E. Factors Determining the Burden of a Caregiver Providing Care to a Post-Stroke Patient. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2025, 14(9), 3008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walkowiak, D; Jabkowski, P; Domaradzki, J. Validation of the Zarit Burden Interview for Polish caregivers of individuals with rare diseases: a multidimensional approach to assessing caregiver burden. BMC Psychol 2025, 13(1), 1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z; Heffernan, C; Tan, J. Caregiver burden: A concept analysis. Int J Nurs Sci 2020, 7(4), 438–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maksymowicz-Śliwińska A, Lulé D, Nieporęcki K, Ciećwierska K, Ludolph AC, Kuźma-Kozakiewicz M. The quality of life and depression in primary caregivers of patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis is affected by patient-related and culture-specific conditions. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Frontotemporal Degeneration [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2025 Dec 7];24(3–4). Available online: https://ppm.wum.edu.pl/info/article/WUM.

- George, LK; Gwyther, LP. Caregiver Weil-Being: A Multidimensional Examination of Family Caregivers of Demented Adults. The Gerontologist [Internet] 1986, 26(3), 253–9. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/gerontologist/article-lookup/doi/10.1093/geront/26.3.253. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Y; Shen, S; Liu, C; Hong, H; Guan, H; Zhang, J; et al. Internet-Based Supportive Interventions for Family Caregivers of People With Dementia: Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Aging 2024, 7, e50847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ting CY, Ahmed Z. Impact of caregiver interventions on caregiver burden in adult traumatic brain injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Public Health [Internet]. 2025 Dec 3 [cited 2025 Dec 7];13. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/public-health/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2025.1698592/full.

- Bleijlevens, MHC; Stolt, M; Stephan, A; Zabalegui, A; Saks, K; Sutcliffe, C; et al. Changes in caregiver burden and health-related quality of life of informal caregivers of older people with Dementia: evidence from the European RightTimePlaceCare prospective cohort study. Journal of Advanced Nursing [Internet] 2015, 71(6), 1378–91. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jan.12561. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hvalič-Touzery, S; Trkman, M; Dolničar, V. Caregiving Situation as a Predictor of Subjective Caregiver Burden: Informal Caregivers of Older Adults during the COVID-19 Pandemic. IJERPH [Internet]. 2022 Nov 4 [cited 2025 Dec 15];19(21):14496. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/19/21/14496.

- Winblad, B; Amouyel, P; Andrieu, S; Ballard, C; Brayne, C; Brodaty, H; et al. Defeating Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias: a priority for European science and society. The Lancet Neurology [Internet] 2016, 15(5), 455–532. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1474442216000624. [CrossRef]

- Brodaty, H; Donkin, M. Family caregivers of people with dementia. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2009, 11(2), 217–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macchi, ZA; Koljack, CE; Miyasaki, JM; Katz, M; Galifianakis, N; Prizer, LP; et al. Patient and caregiver characteristics associated with caregiver burden in Parkinson’s disease: a palliative care approach. Ann Palliat Med. 2020, 9 Suppl 1, S24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekhuri, S; Dale, C; Buchanan, F; Hammash, N; Ambreen, M; Saha, S; et al. Family Caregivers of Individuals With Neuromuscular Disease Participating in a Randomized Controlled Trial of a Digital Peer Support Program: Nested Qualitative Study. J Med Internet Res. 2025, 27, e72141–e72141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourão, CML; Fernandes, AFC; Moreira, DP; Martins, MC. Motivational interviewing in the social support of caregivers of patients with breast cancer in chemotherapy. Rev Esc Enferm USP 2017, 51, e03268. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Alfakhri, AS; Alshudukhi, AW; Alqahtani, AA; Alhumaid, AM; Alhathlol, OA; Almojali, AI; et al. Depression Among Caregivers of Patients With Dementia. Inquiry 2018, 55, 46958017750432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donzuso, G; Brunelli, P; Milesi, G; Mancini, S; Martillotti, F; Cicero, CE; et al. Caregiver burden in Parkinson’s disease: a nationwide observational survey. Neurol Sci. 2025, 46(10), 5093–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middleton, JW; Simpson, GK; De Wolf, A; Quirk, R; Descallar, J; Cameron, ID. Psychological Distress, Quality of Life, and Burden in Caregivers During Community Reintegration After Spinal Cord Injury. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation [Internet] 2014, 95(7), 1312–9. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0003999314002573. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, S; Scholcz, A; Rouse, MA; Klar, VS; Ganse-Dumrath, A; Toniolo, S; et al. Self- versus caregiver-reported apathy across neurological disorders. Brain Communications [Internet] 2025, 7(3), fcaf235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suksatan, W; Tankumpuan, T; Davidson, PM. Heart Failure Caregiver Burden and Outcomes: A Systematic Review. J Prim Care Community Health [Internet] 2022, 13, 21501319221112584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del-Pino-Casado, R; Priego-Cubero, E; López-Martínez, C; Orgeta, V. Subjective caregiver burden and anxiety in informal caregivers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE [Internet] 2021, 16(3), e0247143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meurer, KJ; Presciutti, AM; Bannon, SM; Kubota, R; Baskaran, N; Kim, J; et al. Characterizing Stressors and Coping Strategies Among Caregivers of Patients with Severe Acute Brain Injury by Level of Distress. Neurocrit Care [Internet]. 2025 June 6 [cited 2025 Dec 15]. [CrossRef]

- Bártolo, A; Sousa, H; Ribeiro, O; Figueiredo, D. Effectiveness of psychosocial interventions on the burden and quality of life of informal caregivers of hemodialysis patients: a systematic review. Disability and Rehabilitation [Internet] 2022, 44(26), 8176–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ransmayr, G. Challenges of caregiving to neurological patients. Wien Med Wochenschr [Internet] 2021, 171(11–12), 282–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugh, JD; McCoy, K; Williams, AM; Pienaar, CA; Bentley, B; Monterosso, L. Neurological patient and informal caregiver quality of life, and caregiver burden: A cross-sectional study of postdischarge community neurological nursing recipients. Contemporary Nurse [Internet] 2022, 58(2–3), 138–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rokach, A; Findler, L; Chin, J; Lev, S; Kollender, Y. Cancer patients, their caregivers and coping with loneliness. Psychology, Health & Medicine [Internet] 2013, 18(2), 135–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabata-Kelly, M; Ruan, M; Dey, T; Sheu, C; Kerr, E; Kaafarani, H; et al. Postdischarge Caregiver Burden Among Family Caregivers of Older Trauma Patients. JAMA Surg [Internet] 2023, 158(9), 945. Available online: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamasurgery/fullarticle/2806773. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Onofrio, G; Sancarlo, D; Addante, F; Ciccone, F; Cascavilla, L; Paris, F; et al. Caregiver burden characterization in patients with Alzheimer’s disease or vascular dementia. Int J Geriat Psychiatry [Internet] 2015, 30(9), 891–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, CK. Concepts in Caregiver Research. J Nursing Scholarship [Internet] 2003, 35(1), 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).