Submitted:

26 November 2024

Posted:

27 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.2. Participants and Data Collection

2.3. Measurements

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Questionnaire

3.1.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics of Study Participants

3.1.2. The ZBI-22 tool

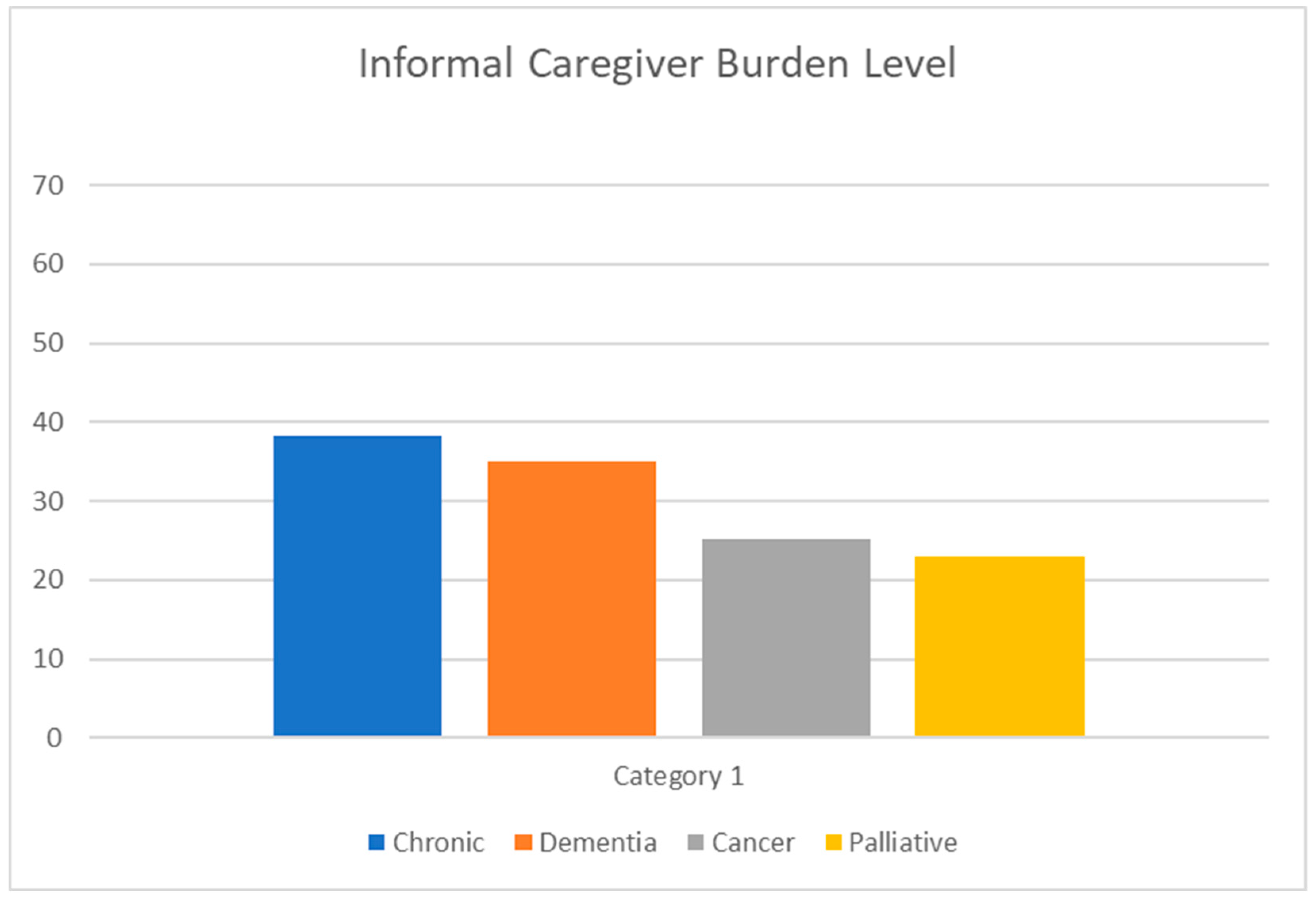

3.2. Informal Caregiver Burden

3.3. Bivariate Analysis (ZBI-22) with Significant (P-Value > 0.05)

3.4. Multiple Logistic Regression Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gov.sa. https://www.my.gov.sa/wps/portal/snp/careaboutyou/elderly/!ut/p/z0/04_Sj9CPykssy0xPLMnMz0vMAfIjo8zijQx93d0NDYz8LYIMLA0CQ4xCTZwN_Ay8Qgz1g1Pz9AuyHRUB-ivojg!!/#:~:text=The%20Ministry%20provides%20the%20elderly,and%20their%20families%20through%20the. 2024 [cited 2024 Nov 19]. Elderly. Available from: https://www.my.gov.sa/wps/portal/snp/careaboutyou/elderly/!ut/p/z0/04_Sj9CPykssy0xPLMnMz0vMAfIjo8zijQx93d0NDYz8LYIMLA0CQ4xCTZwN_Ay8Qgz1g1Pz9AuyHRUB-ivojg!!/#:~:text=The%20Ministry%20provides%20the%20elderly,and%20their%20families%20through%20the.

- United Nations. World Population Ageing - Highlights. Department of Economic and Social Affairs - Population Division. 2017;((ST/ESA/SER.A/397)).

- Althabe F, Belizán JM, McClure EM, Hemingway-Foday J, Berrueta M, Mazzoni A, et al. A population-based, multifaceted strategy to implement antenatal corticosteroid treatment versus standard care for the reduction of neonatal mortality due to preterm birth in low-income and middle-income countries: The ACT cluster-randomised trial. The Lancet. 2015 Feb 14;385(9968):629–39. [CrossRef]

- Home health services [Internet]. [cited 2024 Nov 19]. Available from: https://www.medicare.gov/coverage/home-health-services.

- Ellenbecker CH, Samia L, Cushman MJ, Alster K. Chapter 13. Patient Safety and Quality in Home Health Care.

- Homecare is the solution [Internet]. [cited 2024 Nov 19]. Available from: http://www .aahomecare .org/associations/3208 /files/home%20healthcare%202%20pager .pdf.

- Wilson DR. Home health nursing: scope and standards of practice. Act Adapt Aging. 2019;43(1). [CrossRef]

- Shaughnessy PW, Hittle DF, Crisler KS, Powell MC, Richard AA, Kramer AM, et al. Improving patient outcomes of home health care: Findings from two demonstration trials of outcome-based quality improvement. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(8). [CrossRef]

- Almoajel A, Al-Salem A, Al-Ghunaim L, Al-Amri S. The Quality of Home Healthcare Service in Riyadh/Saudi Arabia. Asian Journal of Natural & Applied Sciences. 2016;5(2).

- Lang A, Edwards N, Hoffman C, Shamian J, Benjamin K, Rowe M. Broadening the patient safety agenda to include home care services. Healthc Q. 2006;9 Spec No. [CrossRef]

- Gouin JP, da Estrela C, Desmarais K, Barker ET. The Impact of Formal and Informal Support on Health in the Context of Caregiving Stress. Fam Relat. 2016;65(1). [CrossRef]

- van Exel J, Bobinac A, Koopmanschap M, Brouwer W. The invisible hands made visible: Recognizing the value of informal care in healthcare decision-making. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2008;8(6). [CrossRef]

- Brouwer WBF, Van Exel NJA, Van Den Berg B, Van Den Bos GAM, Koopmanschap MA. Process utility from providing informal care: The benefit of caring. Health Policy (New York). 2005;74(1). [CrossRef]

- Pendergrass A, Mittelman M, Graessel E, Özbe D, Karg N. Predictors of the personal benefits and positive aspects of informal caregiving. Aging Ment Health. 2019;23(11). [CrossRef]

- Knight BG, Fox LS, Chou CP. Factor structure of the burden interview. J Clin Geropsychology. 2000;6(4). [CrossRef]

- Arai Y, Kudo K, Hosokawa T, Washio M, Miura H, Hisamichi S. Reliability and validity of the Japanese version of the Zarit Caregiver burden Interview. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1997;51(5). [CrossRef]

- M Bédard 1 DWMLSSDJALMO. The Zarit Burden Interview: a new short version and screening version. Gerontologist. 2001.

- Harding R, Gao W, Jackson D, Pearson C, Murray J, Higginson IJ. Comparative Analysis of Informal Caregiver Burden in Advanced Cancer, Dementia, and Acquired Brain Injury. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;50(4). [CrossRef]

- Ahmad Zubaidi ZS, Ariffin F, Oun CTC, Katiman D. Caregiver burden among informal caregivers in the largest specialized palliative care unit in Malaysia: a cross sectional study. BMC Palliat Care. 2020 Dec 1;19(1).

- Al-Rawashdeh SY, Lennie TA, Chung ML. Psychometrics of the zarit burden interview in caregivers of patients with heart failure. Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2016;31(6). [CrossRef]

- Steven H. Zarit JMZ. The memory and behavior problems checklist and the burden interview. 1983.

- Schulz R, Beach SR. Caregiving as a Risk Factor for Mortality The Caregiver Health Effects Study [Internet]. Available from: www.jama.com.

- Gratao ACM, Vale F de AC do, Roriz-Cruz M, Haas VJ, Lange C, Talmelli LF da S, et al. The demands of family caregivers of elderly individuals with dementia. Revista da Escola de Enfermagem da USP. 2010;44(4).

- Denno MS, Gillard PJ, Graham GD, Dibonaventura MD, Goren A, Varon SF, et al. Anxiety and depression associated with caregiver burden in caregivers of stroke survivors with spasticity. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;94(9). [CrossRef]

- Del-Pino-Casado R, Millán-Cobo MD, Palomino-Moral PA, Frías-Osuna A. Cultural correlates of burden in primary caregivers of older relatives: A Cross-sectional Study. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2014;46(3). [CrossRef]

- Al-Khashan H, Mishriky A, Selim M, El Sheikh A, Binsaeed A. Home caregivers’ satisfaction with the services provided by Riyadh Military Hospital’s home support program. Ann Saudi Med. 2011 Nov;31(6):591–7. [CrossRef]

- Youngmee Kim1 RLS and DLH. Quality of life of family caregivers 5 years after a relative’scancer diagnosis: follow-up of the national quality of lifesurvey for caregivers. Psychooncology. 2012.

- Rostami M, Abbasi M, Soleimani M, Moghaddam ZK, Zeraatchi A. Quality of life among family caregivers of cancer patients: an investigation of SF-36 domains. BMC Psychol. 2023 Dec 1;11(1). [CrossRef]

- Hsu T, Loscalzo M, Ramani R, Forman S, Popplewell L, Clark K, et al. Factors associated with high burden in caregivers of older adults with cancer. Cancer. 2014;120(18). [CrossRef]

- Yoon SJ, Kim JS, Jung JG, Kim SS, Kim S. Modifiable factors associated with caregiver burden among family caregivers of terminally ill Korean cancer patients. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2014;22(5). [CrossRef]

- Lowenstein A, Gilbar O. The perception of caregiving burden on the part of elderly cancer patients, spouses and adult children. Vol. 18, Families, Systems and Health. 2000. [CrossRef]

- Doorenbos AZ, Given B, Given CW, Wyatt G, Gift A, Rahbar M, et al. The influence of end-of-life cancer care on caregivers. Vol. 30, Research in Nursing and Health. 2007.

- Depasquale N, Davis KD, Zarit SH, Moen P, Hammer LB, Almeida DM. Combining formal and informal caregiving roles: The psychosocial implications of double- and triple-duty care. Journals of Gerontology - Series B Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2016;71(2). [CrossRef]

- Schwartz K, Beebe-Dimmer J, Hastert TA, Ruterbusch JJ, Mantey J, Harper F, et al. Caregiving burden among informal caregivers of African American cancer survivors. Journal of Cancer Survivorship. 2021;15(4). [CrossRef]

- Ye Ji Seo HP. Factors influencing caregiver burden in families of hospitalised patients with lung cancer. Wiley. 2019.

- Mirsoleymani S, Rohani C, Matbouei M, Nasiri M, Vasli P. Predictors of caregiver burden in Iranian family caregivers of cancer patients. J Educ Health Promot. 2017;6(1). [CrossRef]

- Lukhmana S, Bhasin SK, Chhabra P, Bhatia MS. Family caregivers’ burden: A hospital based study in 2010 among cancer patients from Delhi. Indian J Cancer. 2015;52(1). [CrossRef]

- Zarzycki M, Seddon D, Bei E, Dekel R, Morrison V. How Culture Shapes Informal Caregiver Motivations: A Meta-Ethnographic Review. Vol. 32, Qualitative Health Research. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Otis-Green S, Juarez G. Enhancing the Social Well-Being of Family Caregivers. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2012;28(4). [CrossRef]

- Yoo JS, Lee JH, Chang SJ. Family Experiences in End-of-Life Care: A Literature Review. Asian Nurs Res (Korean Soc Nurs Sci). 2008;2(4). [CrossRef]

- Lee J, Cha C. Unmet Needs and Caregiver Burden among Family Caregivers of Hospice Patients in South Korea. Journal of Hospice and Palliative Nursing. 2017;19(4). [CrossRef]

- Nathan E Goldstein 1 JCTRFSVKRJHEHB. Factors associated with caregiver burden among caregivers of terminally ill patients with cancer. J Palliat Care. 2004.

| VARIABLE | Category | Total |

|---|---|---|

| Age | n | 384 |

| Age | Mean (SD) | 52.3 ± 11.49 |

| Age | Median (Q1, Q3) | 53.0(45.50, 60.00) |

| Age | Min, Max | 19.0, 85.0 |

| Disease | Chronic | 104 (27.1%) |

| Disease | Dementia | 119 (31.0%) |

| Disease | Cancer | 78 (20.3%) |

| Disease | Palliative | 83 (21.6%) |

| Duration of Care | Less one year | 114 (29.7%) |

| Duration of Care | More than three years | 160 (41.7%) |

| Duration of Care | One year to three years | 110 (28.6%) |

| Education Level | General education | 192 (50.0%) |

| Education Level | High education | 28 (7.3%) |

| Education Level | University education | 164 (42.7%) |

| Employee | no | 279 (72.7%) |

| Employee | yes | 105 (27.3%) |

| Gender | Female | 266 (69.3%) |

| Gender | Male | 118 (30.7%) |

| Marital Status | Divorced | 30 (7.8%) |

| Marital Status | Married | 288 (75.0%) |

| Marital Status | Single | 60 (15.6%) |

| Marital Status | Widowed | 6 (1.6%) |

| Relationship with Patient | Brother/Sister | 50 (13.0%) |

| Relationship with Patient | Father/Mother | 223 (58.1%) |

| Relationship with Patient | Grandmother/Grandfather | 19 (4.9%) |

| Relationship with Patient | Husband/Wife | 65 (16.9%) |

| Relationship with Patient | Other | 27 (7.0%) |

| Item (384 Responses) | 0 (never) | 1 (rarely) | 2 (sometimes) | 3 (quite frequently) | 4 (nearly always) | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Are you afraid of what the future holds for your neighbor? | 95 (24.7%) | 75 (19.5%) | 99 (25.8%) | 98 (25.5%) | 17 (4.4%) | 1.7 ± 1.23 |

| 2. Are you ashamed of your relative’s behavior? | 201 (52.3%) | 62 (16.1%) | 65 (16.9%) | 56 (14.6%) | 0 (0%) | 0.9 ± 1.13 |

| 3. Do you feel angry or angry if you are with your relative? | 202 (52.6%) | 62 (16.1%) | 83 (21.6%) | 34 (8.9%) | 3 (0.8%) | 0.9 ± 1.08 |

| 4. Do you feel that more needs to be done than you already do for your neighbor? | 45 (11.7%) | 67 (17.4%) | 121 (31.5%) | 102 (26.6%) | 49 (12.8%) | 2.1 ± 1.19 |

| 5. Do you feel that the time you spend with your relative affects your time? | 95 (24.7%) | 91 (23.7%) | 112 (29.2%) | 68 (17.7%) | 18 (4.7%) | 1.5 ± 1.18 |

| 6. Do you feel that you are missing privacy to some degree because of your relative? | 177 (46.1%) | 72 (18.8%) | 79 (20.6%) | 50 (13.0%) | 6 (1.6%) | 1.1 ± 1.15 |

| 7. Do you feel that you can improve the level of care you provide to your relative? | 29 (7.6%) | 82 (21.4%) | 117 (30.5%) | 109 (28.4%) | 47 (12.2%) | 2.2 ± 1.12 |

| 8. Do you feel that you don't have enough money to take care of your relative in addition to the rest of your allowance? | 74 (19.3%) | 54 (14.1%) | 124 (32.3%) | 106 (27.6%) | 26 (6.8%) | 1.9 ± 1.20 |

| 9. Do you feel that you have lost control of your life since your relative’s illness? | 129 (33.6%) | 53 (13.8%) | 98 (25.5%) | 86 (22.4%) | 18 (4.7%) | 1.5 ± 1.29 |

| 10. Do you feel that your health has been affected by the result of your neighbor's care? | 130 (33.9%) | 75 (19.5%) | 114 (29.7%) | 56 (14.6%) | 9 (2.3%) | 1.3 ± 1.15 |

| 11. Do you feel that your relative is currently affecting your relationship with the rest of the family or friends negatively? | 199 (51.8%) | 70 (18.2%) | 68 (17.7%) | 45 (11.7%) | 2 (0.5%) | 0.9 ± 1.10 |

| 12. Do you feel that your relative expects to take care of him as if you are the only person who can rely on him? | 46 (12.0%) | 52 (13.5%) | 114 (29.7%) | 126 (32.8%) | 46 (12.0%) | 2.2 ± 1.18 |

| 13. Do you feel that your relative is asking for help and help more than he really needs? | 130 (33.9%) | 100 (26.0%) | 61 (15.9%) | 48 (12.5%) | 45 (11.7%) | 1.4 ± 1.37 |

| 14. Do you feel that your social life is suffering because of your care for your relative? | 137 (35.7%) | 87 (22.7%) | 81 (21.1%) | 67 (17.4%) | 12 (3.1%) | 1.3 ± 1.21 |

| 15. Do you feel the psychological pressure resulting from the distribution of attention between the care of your relative and the performance of your responsibilities towards the family or work? | 78 (20.3%) | 107 (27.9%) | 110 (28.6%) | 63 (16.4%) | 26 (6.8%) | 1.6 ± 1.18 |

| 16. Do you feel tight (uncomfortable) when you’re with your relative? | 170 (44.3%) | 63 (16.4%) | 95 (24.7%) | 48 (12.5%) | 8 (2.1%) | 1.1 ± 1.17 |

| 17. Do you feel uncomfortable inviting a friend because of your relative? | 163 (42.4%) | 70 (18.2%) | 91 (23.7%) | 48 (12.5%) | 12 (3.1%) | 1.2 ± 1.19 |

| 18. Do you feel unsure of what to do with your relative? | 131 (34.1%) | 70 (18.2%) | 108 (28.1%) | 70 (18.2%) | 5 (1.3%) | 1.3 ± 1.16 |

| 19. Do you feel you can't continue to take care of your relative? | 180 (46.9%) | 71 (18.5%) | 77 (20.1%) | 47 (12.2%) | 9 (2.3%) | 1.0 ± 1.17 |

| 20. Do you price that your relative depends on you? | 27 (7.0%) | 49 (12.8%) | 92 (24.0%) | 148 (38.5%) | 68 (17.7%) | 2.5 ± 1.13 |

| 21. In general, how much do you feel the burden of caring for your neighbor? | 117 (30.5%) | 76 (19.8%) | 117 (30.5%) | 64 (16.7%) | 10 (2.6%) | 1.4 ± 1.16 |

| 22. Would you like to leave your neighbor's care for someone else? | 193 (50.3%) | 59 (15.4%) | 76 (19.8%) | 50 (13.0%) | 6 (1.6%) | 1.0 ± 1.17 |

| NAME OF FORMER VARIABLE | cat2 | Yes (ZBI-22 score ≥ 21) = 286 | No (ZBI-22 score < 21) = 98 | Total=384 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Mean (SD) | 53.5 (10.97) | 48.8 (12.29) | 52.3 (11.49) | 0.0003 ^ |

| Age | Median (Q1, Q3) | 54.0 (48.00, 61.00) | 50.0(40.00, 57.00) | 53.0(45.50, 60.00) | 0.0003 ^ |

| Disease | Chronic | 94 (32.9) | 10 (10.2) | 104 (27.1) | <.0001 ** |

| Disease | Dementia | 101 (35.3) | 18 (18.4) | 119 (31.0) | <.0001 ** |

| Disease | Cancer | 46 (16.1) | 32 (32.7) | 78 (20.3) | <.0001 ** |

| Disease | Palliative | 45 (15.7) | 38 (38.7) | 83 (21.6) | <.0001 ** |

| Duration of Care | Less one year | 75 (26.2) | 39 (39.8) | 114 (29.7) | 0.0342 ** |

| Duration of Care | More than three years | 127 (44.4) | 33 (33.7) | 160 (41.7) | 0.0342 ** |

| Duration of Care | One year to three years | 84 (29.4) | 26 (26.5) | 110 (28.6) | 0.0342 ** |

| Education Level | General education | 148 (51.7) | 44 (44.9) | 192 (50.0) | 0.0113 ** |

| Education Level | High education | 26 (9.1) | 2 (2.0) | 28 (7.3) | 0.0113 ** |

| Education Level | University education | 112 (39.2) | 52 (53.1) | 164 (42.7) | 0.0113 ** |

| Employee | no | 228 (79.7) | 51 (52.0) | 279 (72.7) | <.0001 ** |

| Employee | yes | 58 (20.3) | 47 (48.0) | 105 (27.3) | <.0001 ** |

| Gender | Female | 218 (76.2) | 48 (49.0) | 266 (69.3) | <.0001 ** |

| Gender | Male | 68 (23.8) | 50 (51.0) | 118 (30.7) | <.0001 ** |

| Marital Status | Divorced | 21 (7.3) | 9 (9.2) | 30 (7.8) | 0.4497 ^^ |

| Marital Status | Married | 220 (76.9) | 68 (69.4) | 288 (75.0) | 0.4497 ^^ |

| Marital Status | Single | 41 (14.4) | 19 (19.4) | 60 (15.6) | 0.4497 ^^ |

| Marital Status | Widowed | 4 (1.4) | 2 (2.0) | 6 (1.6) | 0.4497 ^^ |

| Relationship with Patient | Brother/Sister | 42 (14.7) | 8 (8.2) | 50 (13.0) | <.0001 ** |

| Relationship with Patient | Father/Mother | 149 (52.1) | 74 (75.5) | 223 (58.1) | <.0001 ** |

| Relationship with Patient | Grandmother/ Grandfather | 10 (3.5) | 9 (9.2) | 19 (4.9) | <.0001 ** |

| Relationship with Patient | Husband/Wife | 62 (21.7) | 3 (3.1) | 65 (16.9) | <.0001 ** |

| Relationship with Patient | Other | 23 (8.0) | 4 (4.0) | 27 (7.0) | <.0001 ** |

| Denominator of the percentage is the total number of subjects in each group. | |||||

| *T -Test / ^ Wilcoxon rank sum test is used to calculate the P-value. | |||||

| **Chi-square test is used to calculate the P-value. | |||||

| ^^Fisher exact test is used to calculate the P-value. | |||||

| Effect | Beta | Standard Error | Odds Ratio | [95% Conf. Interval] | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | -0.00114 | 0.0144 | 0.999 | (0.97, 1.03) | 0.9367 |

| Disease Chronic vs Dementia | 0.5697 | 0.4459 | 1.768 | (0.74, 4.24) | 0.2014 |

| Disease Cancer vs Dementia | -0.8910 | 0.4259 | 0.410 | (0.18, 0.95) | 0.0364 |

| Disease Palliative vs Dementia | -0.8242 | 0.4238 | 0.439 | (0.19, 1.01) | 0.0518 |

| Gender Female vs Male | 0.4141 | 0.3033 | 1.513 | (0.83, 2.74) | 0.1721 |

| Duration of Care More than three years vs Less one year | 0.2763 | 0.3544 | 1.318 | (0.66, 2.64) | 0.4357 |

| Duration of Care One year to three years vs Less one year | 0.2582 | 0.3596 | 1.295 | (0.64, 2.62) | 0.4727 |

| Marital Status Divorced vs Married | 0.2789 | 0.4827 | 1.322 | (0.51, 3.40) | 0.5634 |

| Marital Status Single vs Married | 0.3900 | 0.4159 | 1.477 | (0.65, 3.34) | 0.3484 |

| Marital Status Widowed vs Married | -0.4699 | 0.9956 | 0.625 | (0.09, 4.40) | 0.6369 |

| Employee Yes vs No | -0.7084 | 0.3110 | 0.492 | (0.27, 0.91) | 0.0228 |

| Education Level General education vs University education | 0.2055 | 0.2843 | 1.228 | (0.70, 2.14) | 0.4697 |

| Education Level High education vs University education | 2.0668 | 0.8001 | 7.899 | (1.65, 37.90) | 0.0098 |

| Relationship W/ Patient Brother/Sister vs Father/Mother | 0.4146 | 0.4576 | 1.514 | (0.62, 3.71) | 0.3649 |

| Relationship W/ Patient GrandMoth/GrandFath vs Father/Mother | -0.4272 | 0.5679 | 0.652 | (0.21, 1.99) | 0.4519 |

| Relationship W/ Patient Husband/Wife vs Father/Mother | 2.1022 | 0.6493 | 8.184 | (2.29, 29.22) | 0.0012 |

| Relationship W/ Patient Other vs Father/Mother | 0.2945 | 0.6099 | 1.342 | (0.41, 4.44) | 0.6293 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).