Submitted:

09 August 2023

Posted:

10 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Research Methodology

The Study Design

Study Setting

Study Population

Recruitment

Sampling Techniques

Sample Size

Data Collection Tools

- The Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI) Scale was used to measure the burden of care among the participants. The ZBI is a globally validated tool which is designed for measuring caregiver’s perceived burden of care while providing family care for a relative. The tool has been widely used in both developed and developing countries, and has been confirmed to be both reliable and valid [13,14,15].

- A quantitative questionnaire was used to collect socio-demographic data of the participants, as well as data on their relatives with mental disorders.

Data Collection

Ethical Considerations

Data Analysis

Characteristics of Caregivers

Socio-Demographic Information of MHCUs

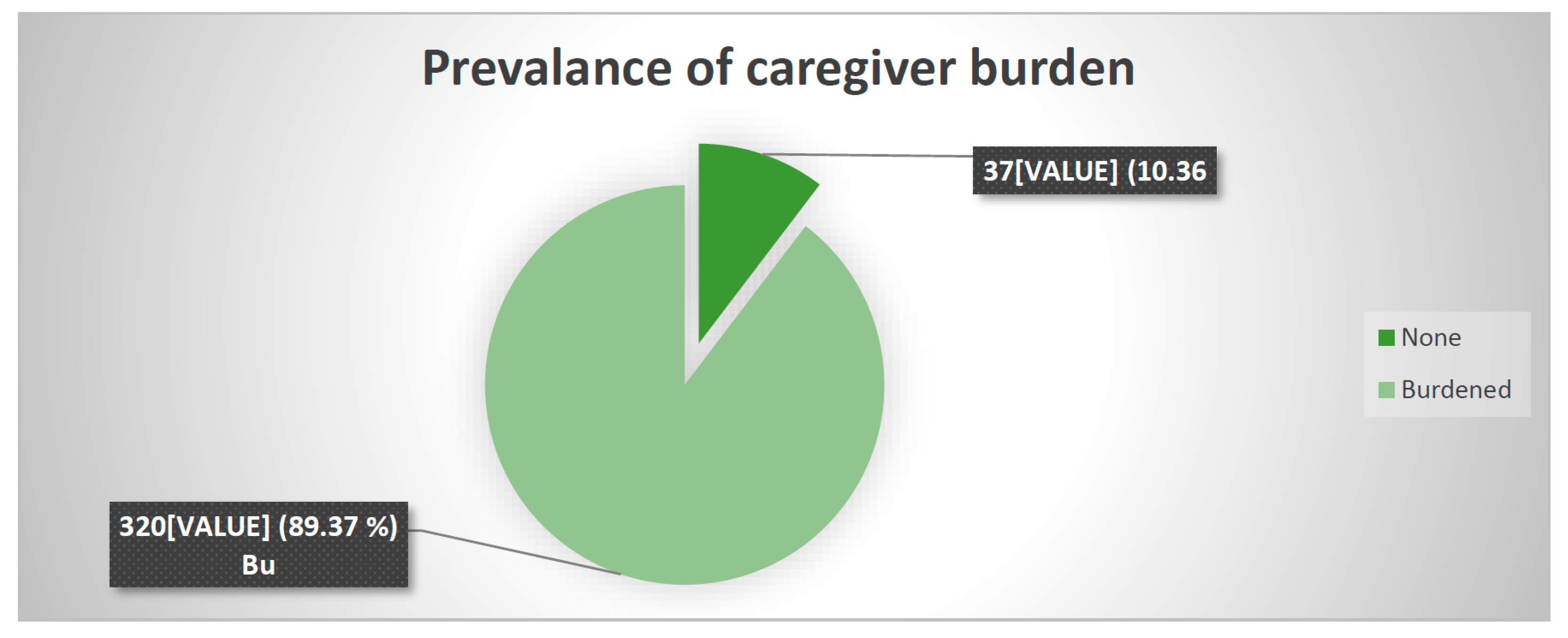

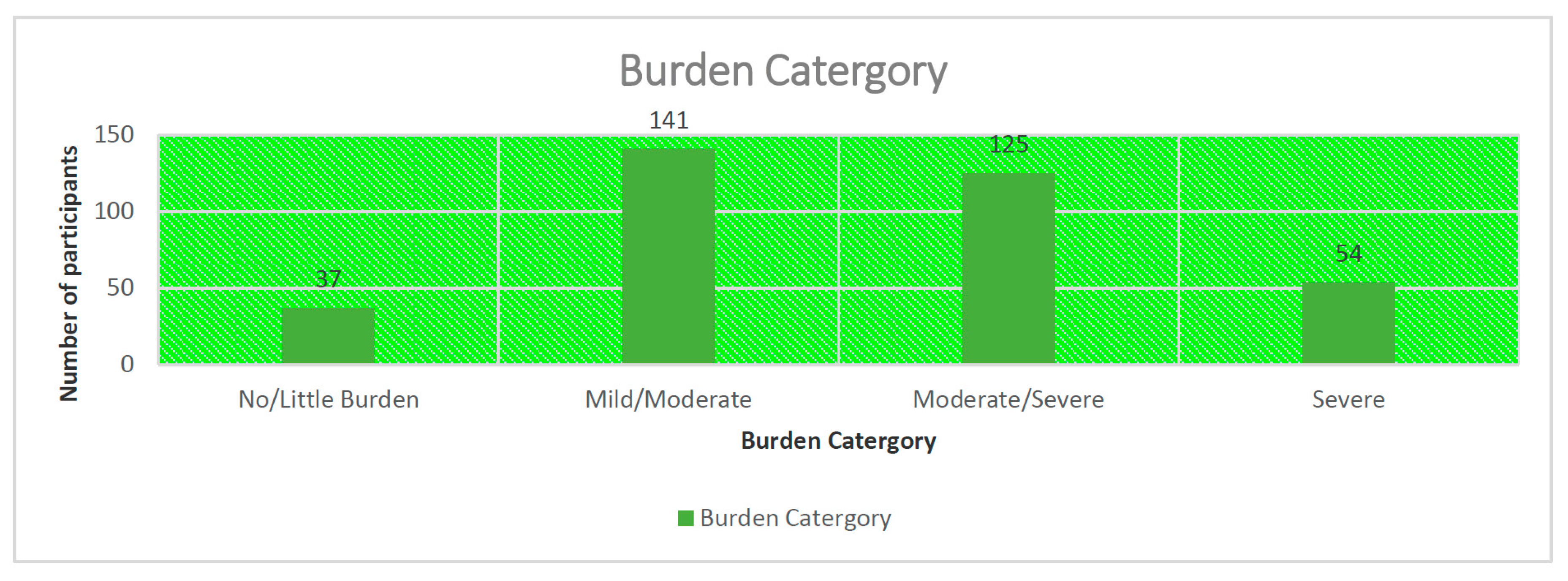

Quantification of Caregiver Burden

Factors Associated with Caregiving Burden

Discussion

Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Recommendations

References

- Ae-Ngibise K, Victor Christian Korley Doku, Kwaku Poku Asante & Seth Owusu-Agyei (2015) The experience of caregivers of people living with serious mental disorders: a study from rural Ghana, Global Health Action, 8:1, 26957 10.3402/gha.v8.26957. [CrossRef]

- GBD 2019 Disease and Injuries Collaborators. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020; 396: 1204–22.

- Zwane, F.L., 2012, ‘Family caregivers’ lived experiences of violence at the hands of their mentally ill relatives in Swaziland’, M.Cur dissertation (Psychiatric nursing), University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg.

- Gupta S, Isherwood G, Jones K, Impe KV. Assessing health status in informal schizophrenia caregivers compared with health status in non-caregivers and caregivers of other conditions. BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15:162.

- Makhosazane Ntuli and Sphiwe Madiba. 2019.The Burden of Caring: An Exploratory Study of the Older Persons Caring for Adult Children with AIDS-Related Illnesses in Rural Communities in South Africa. Department of Public Health, Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University, Pretoria 0001, South Africa.

- Kartalova-O'Doherty, Y and D TedstoneDoherty , 2008 . Coping strategies and styles of family carers of persons with enduring mental Illness: a mixed methods analysis; Scand J Caring Sci . March 2008 ; 22(1): 19–28. [CrossRef]

- Dussel V, Bona K, Heath JA, Hilden JM, Weeks JC, Wolfe J. Unmeasured Costs of a Child’s Death: Perceived Financial Burden, Work Disruptions, and Economic Coping Strategies Used by American and Australian Families Who Lost Children to Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011; 29(8): 1007-1013.

- Santomauro D & COVID-19 Mental Disorders Collaborators, 2021. Global Prevalence and Burden of Depressive and Anxiety Disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Queensland Centre for Mental Health Research. The Park Centre for Mental Health, Locked Bag, 500. Archerfield, 4108, Australia.

- Ndetei D, Pizzo M, Khasakhala L, Maru H, Mutiso V, Ongecha-Owuor F. Perceived economic and behavioural effects of the mentally ill on their relatives in Kenya: A case study of Mathari hospital. Afr J Psychiatr 2009;12:293-99.

- Jack-Ide, I.O., Uys, L.R. & Middleton, L.E., 2012, ‘Caregiving experiences of families of persons with serious mental health problems in the Niger Delta region of Nigeria’, International Journal of Mental Health Nursing 22(2), 170–179.

- Mamabolo, L. M. (2013). Exploring community based interventions for mentally ill patients to improve quality of care. Potchefstroom Campus, North West University, South Africa.

- Monyaluoe, M., Mvandaba, M., Du Plessis, E.D. & Koen, M.P., 2014, ‘Experiences of families living with a mentally ill family member’, Journal of Psychiatry 17(5), 131. [CrossRef]

- Hagell, P., Alvariza, A., Westergren, A., &Årestedt, K. (2017). Assessment of burden among family caregivers of people with Parkinson's disease using the Zarit Burden Interview. Journal of pain and symptom management, 53(2), 272-278.

- Galindo-Vazquez, O., Benjet, C., Cruz-Nieto, M. H., Rojas-Castillo, E., Riveros-Rosas, A., Meneses-Garcia, A., & Alvarado-Aguilar, S. (2015). Psychometric properties of the Zarit Burden Interview in Mexican caregivers of cancer patients. Psycho-oncology, 24(5), 612-615.

- Pinyopornpanish, K., Pinyopornpanish, M., Wongpakaran, N., Wongpakaran, T., Soontornpun, A., &Kuntawong, P. (2020). Investigating psychometric properties of the Thai version of the Zarit Burden Interview using rasch model and confirmatory factor analysis. BMC research notes, 13(1), 1-7.

- Powell, R. A., & Hunt, J. (2013). Family care giving in the context of HIV/AIDS in Africa. Progress in Palliative Care, 21(1), 13-21.

- Cabral, L., Duarte, J., Ferreira, M., & dos Santos, C. (2014). Anxiety, stress and depression in family caregivers of the mentally ill. AtenciónPrimaria, 46, 176-179.

- Xiong, C., Biscardi, M., Astell, A., Nalder, E., Cameron, J. I., Mihailidis, A., &Colantonio, A. (2020). Sex and gender differences in caregiving burden experienced by family caregivers of persons with dementia: A systematic review. PLoS One, 15(4), e0231848.

- Van Rooijen, G., Isvoranu, A. M., Kruijt, O. H., van Borkulo, C. D., Meijer, C. J., Wigman, J. T. & Bartels-Velthuis, A. A. (2018). A state-independent network of depressive, negative and positive symptoms in male patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Schizophrenia Research, 193, 232-239.

- Adeosun II. Correlates of caregiver burden among family members of patients with schizophrenia in Lagos, Nigeria. Schizophr ResTreatment 2013;2013:1–7.

- Ntsayagae, E.I., Poggenpoel, M. &Myburgh, C., 2019, ‘Experiences of family caregivers of persons living with mental illness: A meta-synthesis’, Curationis 42(1), a1900. [CrossRef]

- Souza Ana LúciaRezende , Rafael Alves Guimarães, Daisy de Araújo Vilela, Renata Machado de Assis, LizeteMalagoni de Almeida Cavalcante Oliveira, Mariana Rezende Souza, Douglas José Nogueira and Maria Alves Barbosa. Factors associated with the burden of family caregivers of patients with mental disorders: a cross-sectional study. 2017. BMC Psychiatry 17:353. [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, F., Ranjbar, F., Hosseinzadeh, M., Razavi, S. S., Dickens, G. L., & Vahidi, M. (2019). Coping strategies of family caregivers of patients with schizophrenia in Iran: A cross-sectional survey. International journal of nursing sciences, 6(2), 148-153.

- Niedzwied, C.L. (2019). How does mental health stigma get under the skin? : Cross-sectional analysis using Health Survey for England. Institute of Health and Wellbeing. University of Glasgow, 1 Lilybank Gardens, Glasgow, G12 8RZ, United Kingdom.

- Mulaudzi, R., & Ajoodha, R. (2020), November). An exploration of machine learning models to forecast the unemployment rate of South Africa: a univariate approach. In 2020 2nd International Multidisciplinary Information Technology and Engineering Conference (IMITEC) (pp. 1-7). IEEE.

- Alenda-Demoutiez, J., &Mügge, D. (2020). The lure of ill-fitting unemployment statistics: How South Africa’s discouraged work seekers disappeared from the unemployment rate. New Political Economy, 25(4), 590-606.

- Mamabolo, M. A. (2015). Drivers of community xenophobic attacks in South Africa: poverty and unemployment. TD: The Journal for Transdisciplinary Research in Southern Africa, 11(4), 143-150.

- Weir-Smith, G. (2016). Changing boundaries: Overcoming modifiable areal unit problems related to unemployment data in South Africa. South African Journal of Science, 112(3-4), 1-8.

- Mavundla, T.R., Toth, F. &Mphelane, M.L., (2009). ‘Caregiver experience in mental illness: A perspective from a rural community in South Africa’, International Journal of Mental Health Nursing 18(5), 357–367. [CrossRef]

- Chang H-Y, Chiou C-J, Chen N-S. Impact of mental health and caregiver burden on family caregivers’ physical health. Arch GerontolGeriatr. 2010; 50(3):267–71.

- Lund C, Myer L, Stein DJ, William DR, Flisher AJ. Mental illness and lost income among adult South Africans. Soc Psychiatry PsychiatrEpidemiol. 2013; 48 (5):845-51.

- Zendjidjian, X., Richieri, R., Adida, M., Limousin, S., Gaubert, N., Parola, N., Lançon, C. and Boyer, L., 2012. Quality of life among caregivers of individuals with affective disorders. Journal of affective disorders, 136(3), pp.660-665.

- Kate N, Grover S, Kulhara P, Nehra R. Relationship of caregiver burden with coping strategies, social support, psychological morbidity, and quality of life in the caregivers of schizophrenia. Asian J Psychiatr. 2013;6(5):388.

- Chang S, Zhang Y, Jeyagurunathan A, Lau YW, Sagayadevan V, Chong SA, Subramaniam M. Providing care to relatives with mental illness: reactions and distress among primary informal caregivers. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16:80.

- Ostacher MJ, Nierenberg AA, Iosifescu DV, Eidelman P, Lund HG, Ametrano RM, Kaczynski R, Calabrese J, Miklowitz DJ, Sachs GS,. Correlates of subjective and objective burden among caregivers of patients with bipolar disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2008;118(1):49–56.

- Tomlinson, M., Grimsrud, A.T., Stein, D.J., Williams, D.R. and Myer, L., 2009. The epidemiology of major depression in South Africa: results from the South African Stress and Health study: mental health. South African Medical Journal, 99(5), pp.368-373.

- Lotfaliany, M., Bowe, S.J., Kowal, P., Orellana, L., Berk, M. and Mohebbi, M., 2018. Depression and chronic diseases: Co-occurrence and communality of risk factors. Journal of affective disorders, 241, pp.461-468.

- Burns JK & Tomita A. (2015). Traditional and religious healers in the pathway to care for people with mental disorders in Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Social psychiatry and Psychiatric epidemiology, 50, 6, 867.

- Nhlapo Z. (2017). Being Poor and Mentally Ill In South Africa Equals Being Pretty Much Screwed. http://www. huffingtonpost.co.za/2017/07/31/being-poor-and-mentally-ill-in-south-africa-equals-being-pretty_a_23057607/.

- Olawale KO, Mosaku KS, Fatoye O, Mapayi BM, Oginni OA. Caregiver burden in families of patients with depression attending Obafemi Awolowo university teaching hospitals complex Ile-Ife Nigeria. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2014;36(6):743–.

- Mokwena, K. E., & Ngoveni, A. (2020). Challenges of Providing Home Care for a Family Member with Serious Chronic Mental Illness: A Qualitative Enquiry. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(22), 8440.

| Variable | Frequency(n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (n=357) | ||

| ≤40 years | 77 | 21.57 |

| 41-60 years | 185 | 51.82 |

| ≥61 years | 95 | 26.61 |

| Age (Mean 50.3; SD 12.2; Min 18; Max 65) | ||

| Gender (n=357) | ||

| Female | 306 | 85.71 |

| Male | 51 | 14.29 |

| Level of Education(n=357) | ||

| No formal education. | 99 | 27.73 |

| Primary | 110 | 30.81 |

| Secondary | 127 | 35.57 |

| Tertiary | 21 | 5.88 |

| Marital status(n=357) | ||

| Co-habiting | 76 | 21.29 |

| Married | 80 | 22.41 |

| Single | 192 | 53.78 |

| Widowed | 9 | 2.52 |

| Employment status(n=357) | ||

| Employed | 56 | 15.69 |

| Unemployed | 301 | 84.31 |

| Religion (n=357) | ||

| Christian | 323 | 90.48 |

| Nazareth | 25 | 7.00 |

| None | 3 | 0.84 |

| Other | 6 | 1.68 |

| Other Chronic Diseases (n=357) | ||

| No | 153 | 42.86 |

| Yes | 204 | 57.14 |

| Self-reported depression (n=357) | ||

| No | 343 | 96.08 |

| Yes | 14 | 3.92 |

| Number of children | ||

| None | 14 | 3.92 |

| 1-4 children | 264 | 73.95 |

| More than 5 children | 79 | 22.13 |

| Monthly family income | ||

| Below 2000 | 146 | 40.90 |

| R2001-R4000 | 147 | 41.18 |

| R4000-R10 000 | 48 | 13.45 |

| Above R10 000 | 16 | 4.48 |

| Income (Mean R3803.70; SD 4217.45; Min R0; Max R39000 ) | ||

| Relationship to patient | ||

| Child | 135 | 37.82 |

| Parent | 23 | 6.44 |

| Sibling | 85 | 23.81 |

| Spouse | 39 | 10.92 |

| Other | 75 | 21.01 |

| Receiving help with caregiving (n=357) | ||

| No | 300 | 84.03 |

| Yes | 57 | 15.97 |

| Living with patient (n=357) | ||

| No | 16 | 4.48 |

| Yes | 341 | 95.52 |

| Other family members needing help (n=357) | ||

| No | 216 | 60.50 |

| Yes | 141 | 39.50 |

| Number of days in contact with patient (n=357) | ||

| Everyday | 356 | 99.72 |

| Occasional | 1 | 0.28 |

| Number of years as a caregiver | ||

| Less than 5 years | 83 | 23.25 |

| 6-10 years | 91 | 25.49 |

| More than 10 years | 183 | 51.26 |

| Caregiving years (Mean 14; SD 9.04; Min 1; Max 54) | ||

| Variable | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (n=357) | ||

| Below 25 years | 39 | 10.92 |

| 26-40 years | 157 | 43.98 |

| 41-60 years | 131 | 36.69 |

| Above 60 years | 30 | 8.40 |

| Age (Mean 40.5; SD 12.6; Min 19; Max 76) | ||

| Gender (n=357) | ||

| Female | 112 | 31.37 |

| Male | 245 | 68.63 |

| Level of Education (n=357) | ||

| No Education | 62 | 17.37 |

| Primary | 130 | 36.41 |

| Secondary | 152 | 42.58 |

| Tertiary | 13 | 3.64 |

| Marital status (n=357) | ||

| Co-habiting | 28 | 7.84 |

| Married | 16 | 4.48 |

| Single | 313 | 87.68 |

| Diagnosis (n=357) | ||

| Bipolar Mood Disorder | 103 | 28.85 |

| Major Depressive Disorder | 41 | 11.48 |

| Schizophrenia | 213 | 59.66 |

| Duration of illness (n=357) | ||

| Less than 5 years | 74 | 20.73 |

| 5-10 years | 93 | 26.05 |

| 11-20 years | 126 | 35.29 |

| More than 20 years | 64 | 17.93 |

| Relapsed admission (n=357) | ||

| No | 299 | 83.75 |

| Yes | 58 | 16.25 |

| Disability grant | ||

| No | 81 | 22.69 |

| Yes | 276 | 77.31 |

| Employment status (n=357) | ||

| Employed | 1 | 0.28 |

| Unemployed | 356 | 99.72 |

| Relationship to caregiver (n=357) | ||

| Child | 24 | 6.72 |

| Other | 75 | 21.01 |

| Parent | 135 | 37.82 |

| Sibling | 86 | 24.09 |

| Spouse | 37 | 10.36 |

| Factors | Frequency (%) | Burdened (%) | Not Burdened (%) | Chi² | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age of Caregiver | 10.1653 | 0.006 | |||

| ≤40 years | 77 (21.57) | 65 (20.31) | 12 (32.43) | ||

| 41-60 years | 185 (51.82) | 175 (54.69) | 10 (27.03) | ||

| ≥61 years | 95 (26.61) | 80(25.00) | 15 (40.54) | ||

| Monthly family income | 20.6410 | 0.000 | |||

| Below 2000 | 146 (40.90) | 139(43.44) | 7 (18.92) | ||

| R2001-R4000 | 147 (41.18) | 133 (41.56) | 14 (37.84) | ||

| R4000-R10 000 | 48 (13.45) | 35 (10.94) | 13 (35.14) | ||

| Above R10 000 | 16 (4.48) | 13 (4.06) | 3 (8.11) | ||

| Self-reported depression of caregiver | 5.1997 | 0.023 | |||

| No | 343 (96.08) | 310 (96.88) | 10 (3.13) | ||

| Yes | 14 (3.92 ) | 33 (89.19) | 4 (10.81) | ||

| Receiving help with caregiving role | 5.8278 | 0.016 | |||

| No | 300 (84.03) | 274 (85.63) | 46 (14.37) | ||

| Yes | 57 (15.97) | 26 (70.27) | 11 (29.73) | ||

| Gender of the patient | 4.0719 | 0.044 | |||

| Female | 112 (31.37) | 95 (29.69) | 17 (45.95) | ||

| Male | 245 (68.63) | 225 (70.31) | 20 (54.05) | ||

| History of relapsed after admission | 5.5647 | 0.018 | |||

| No | 299 (83.75) | 263 (82.19) | 36 (97.30) | ||

| Yes | 58 (16.25) | 57 (17.81) | 1 (2.70) | ||

| Employment status of MHCU | 8.6729 | 0.003 | |||

| Employed | 1 (0.28) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (2.70) | ||

| Unemployed | 356 (99.72) | 320 (100.00) | 36 (97.30) |

| Factors | Coef. | Std. Err. | P>|z| | [95% Conf. Interval] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age of Caregiver | .0204188 | .2593118 | 0.937 | -.487823 .5286606 |

| Monthly family income | -.7151498 | .2243773 | 0.001 | -1.154921 -.2753784 |

| Self-reported depression of caregiver | -1.225815 | .6799649 | 0.071 | -2.558521 .106892 |

| Receiving help with caregiving role | -.2534951 | .4568942 | 0.579 | -1.148991 .6420011 |

| Gender of the patient | .5283181 | .3777569 | 0.162 | -.2120719 1.268708 |

| Relapsed admission patient history | 2.248435 | 1.056517 | 0.033 | .1776989 4.31917 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).